Submitted:

19 December 2025

Posted:

22 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

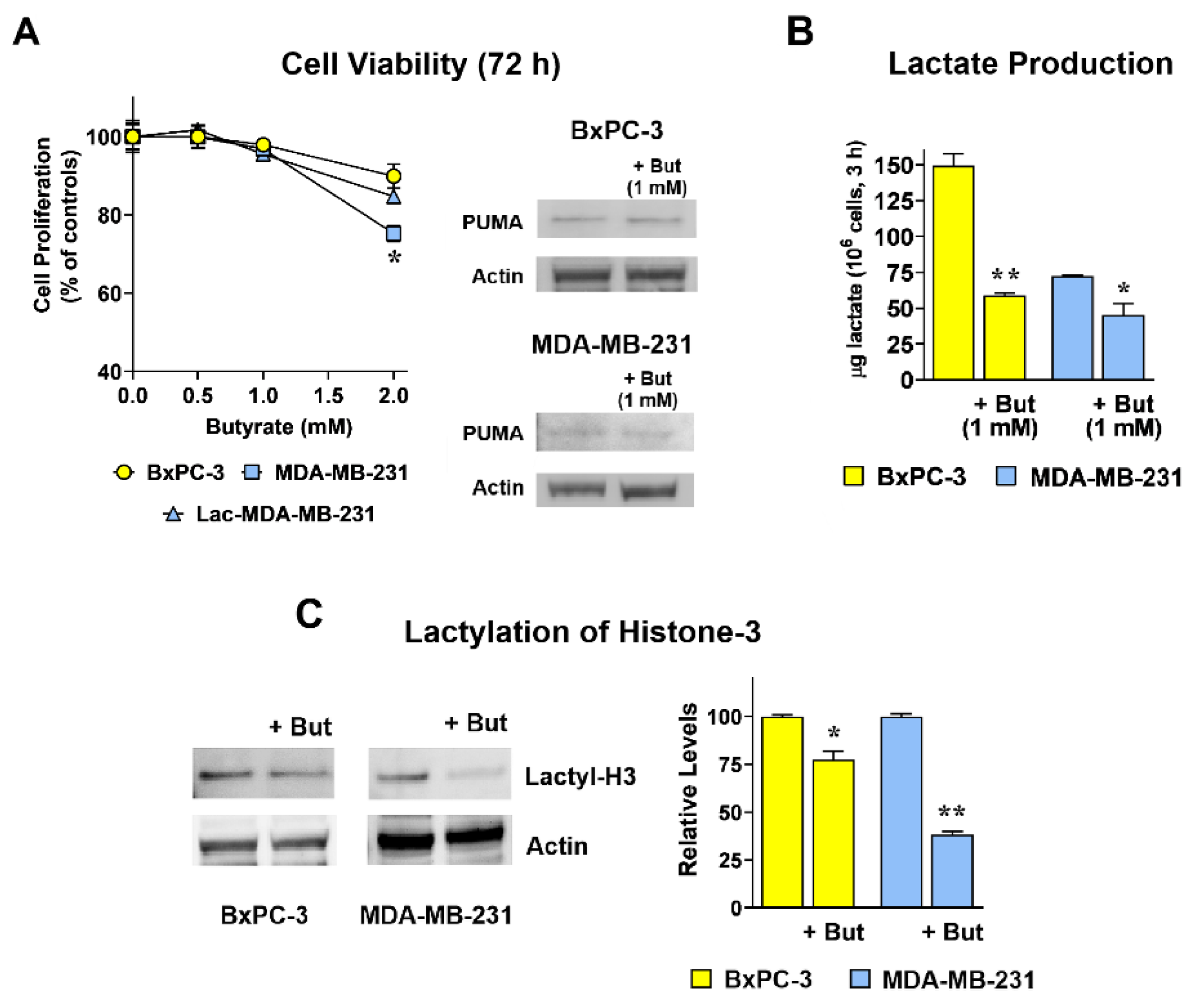

2.1. Butyrate Reduces Lactate Production and Histone-3 Lactylation in Both BxPC-3 and MDA-MB-231 Cultures

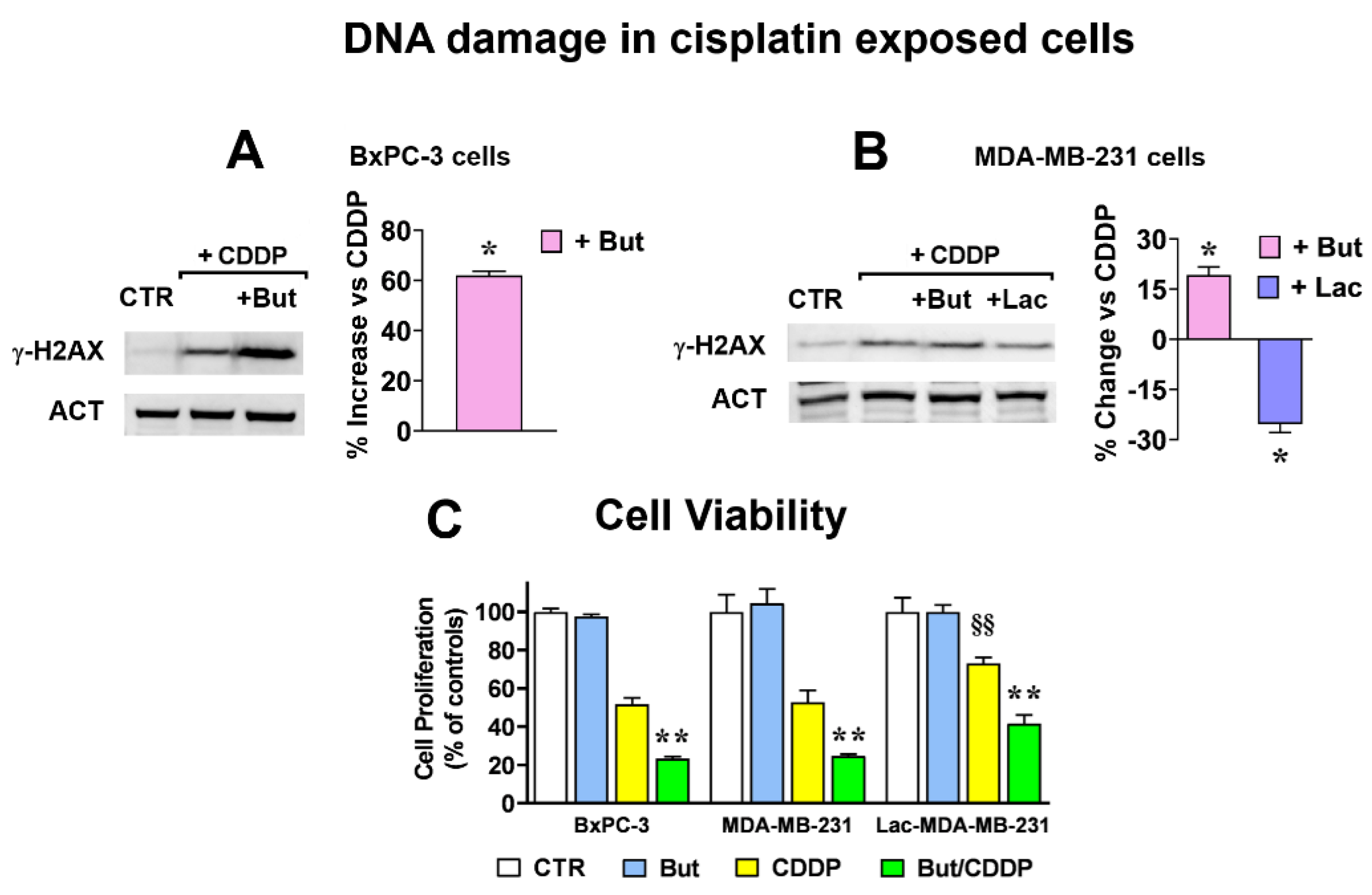

2.2. Butyrate and Lactate Modify in Opposite Ways Cisplatin Antineoplastic Effect

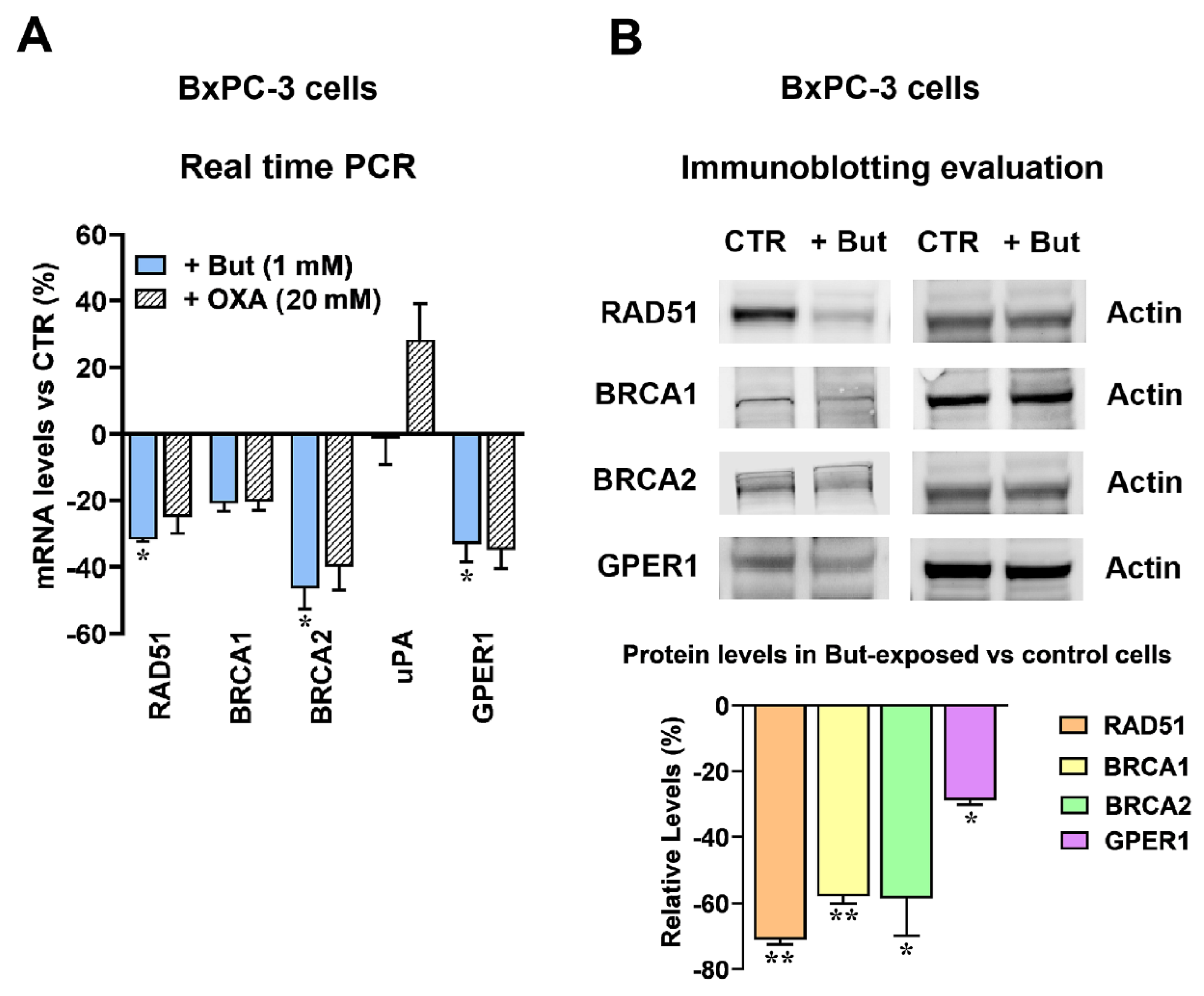

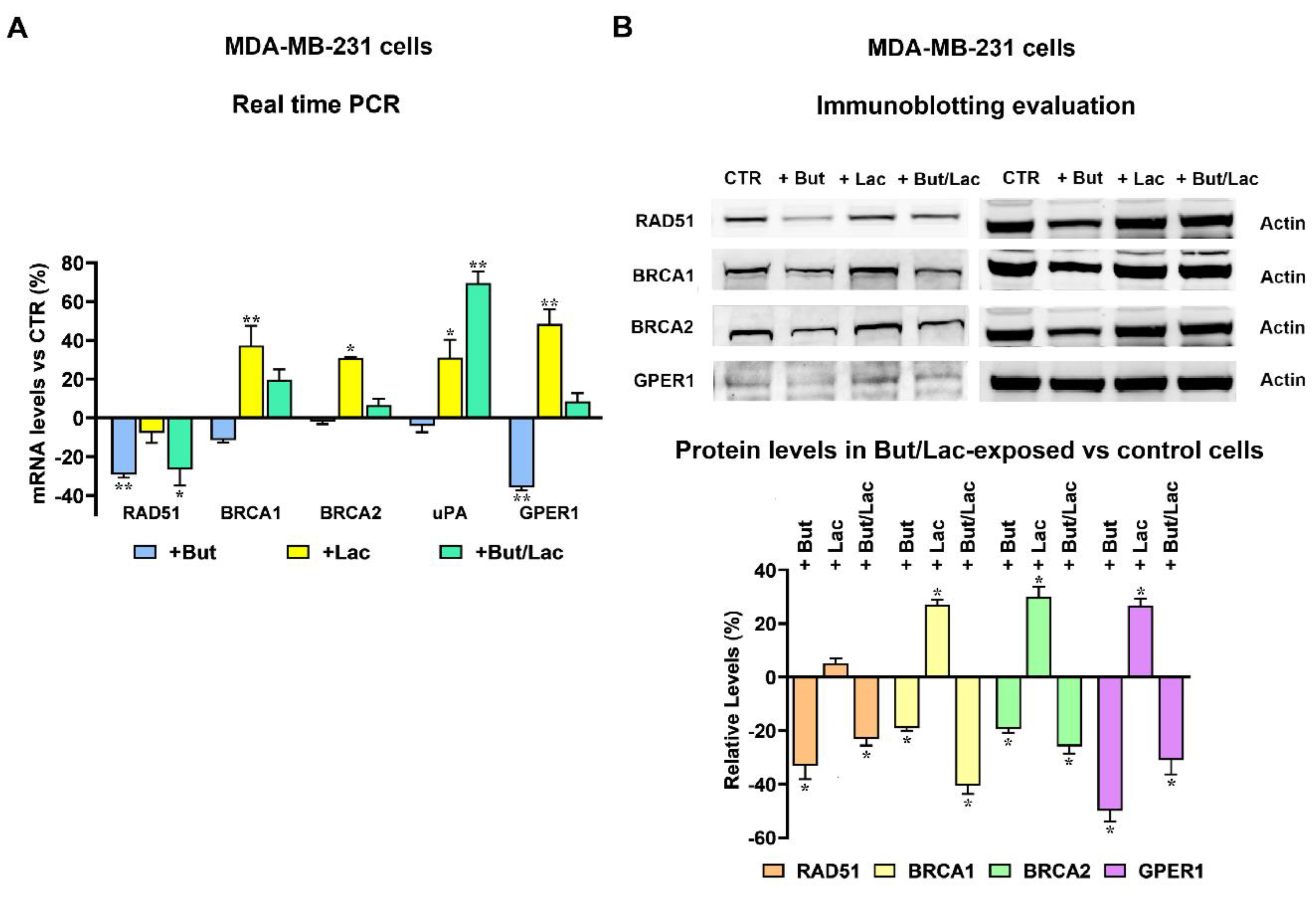

2.3. Butyrate and Lactate Can Differently Affect the Expression of Genes Involved in DNA Repair by Homologous Recombination

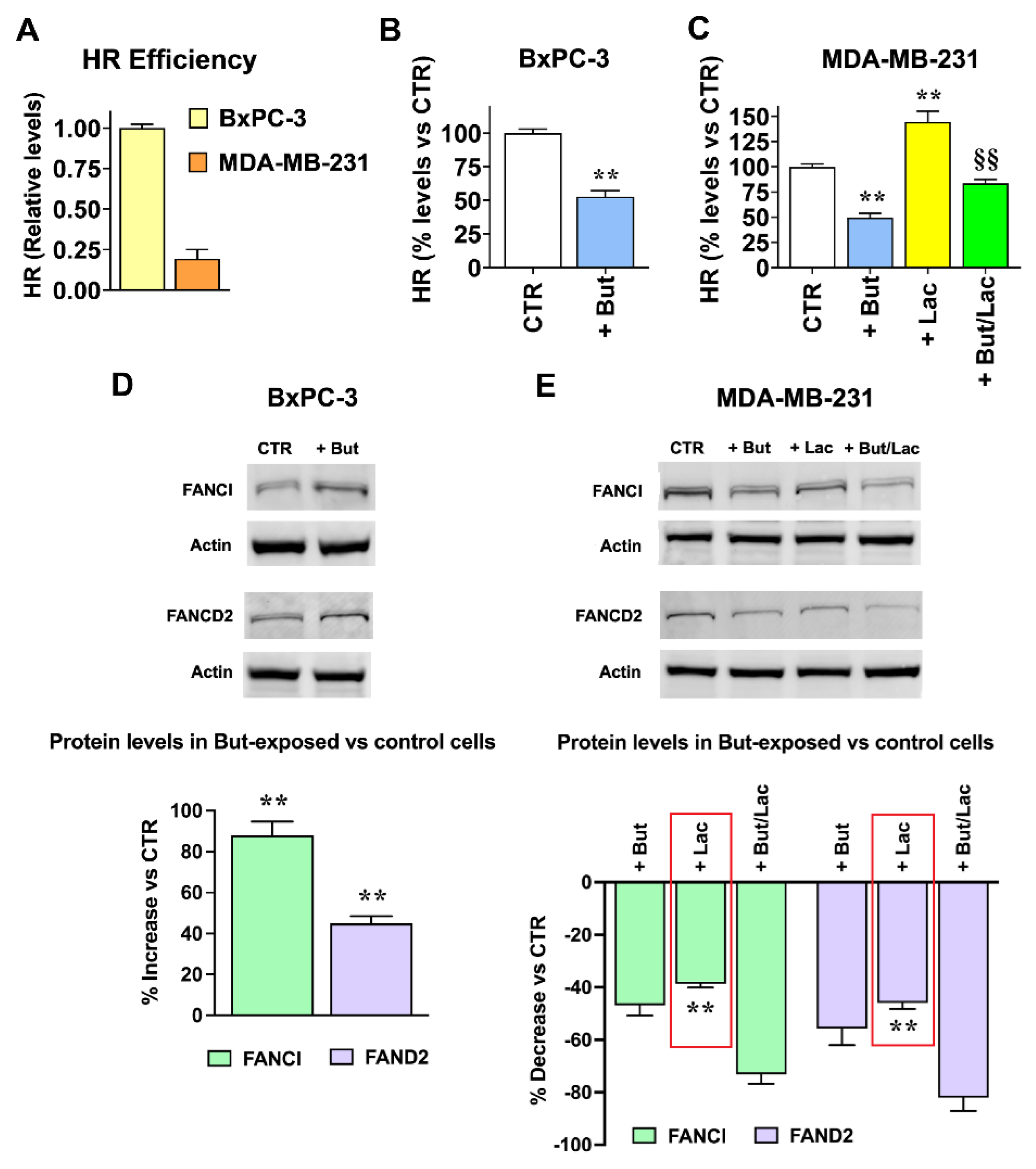

2.4. The Gene Expression Changes Induced by Lactate and Butyrate Modify HR Efficiency

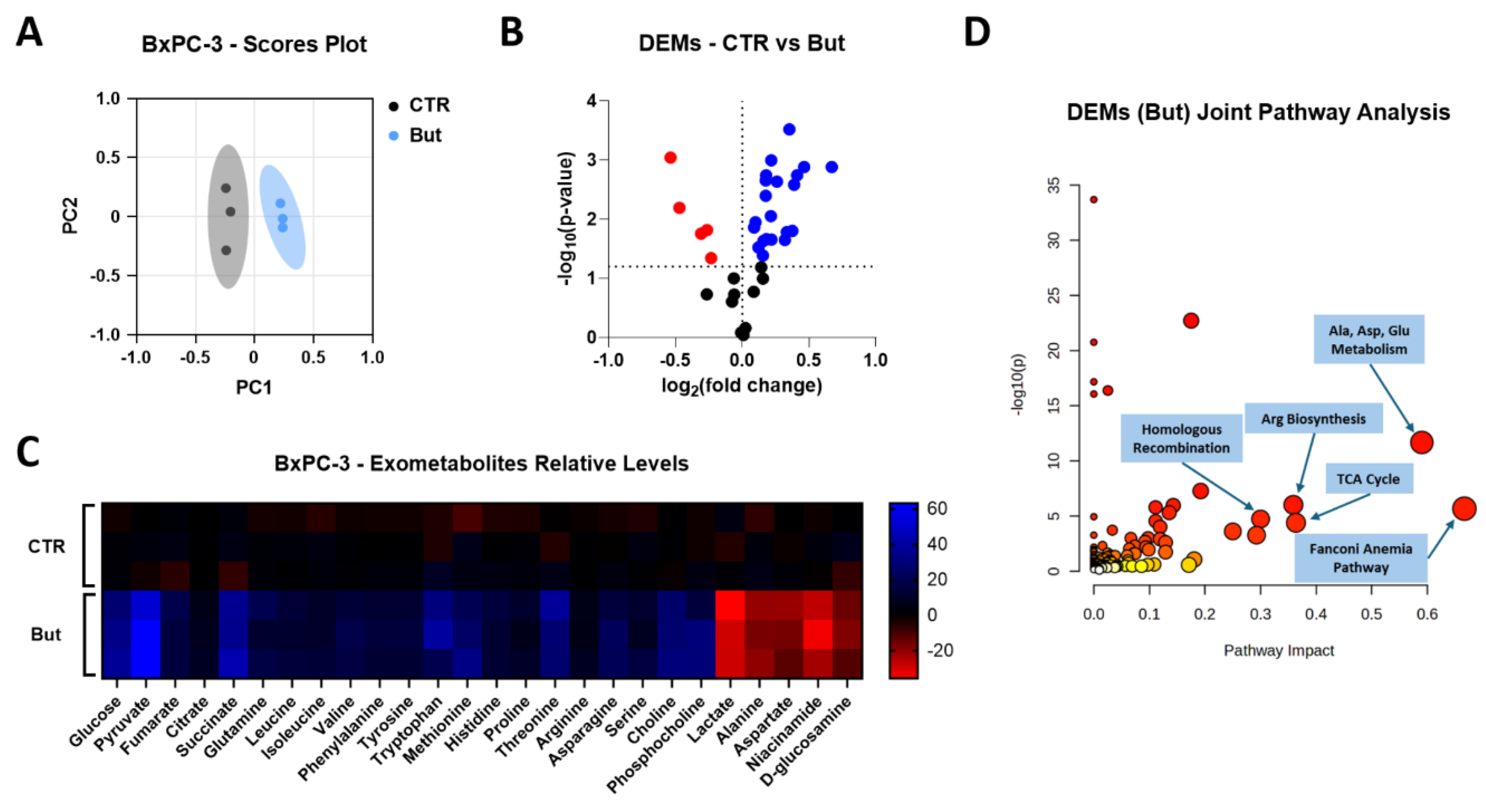

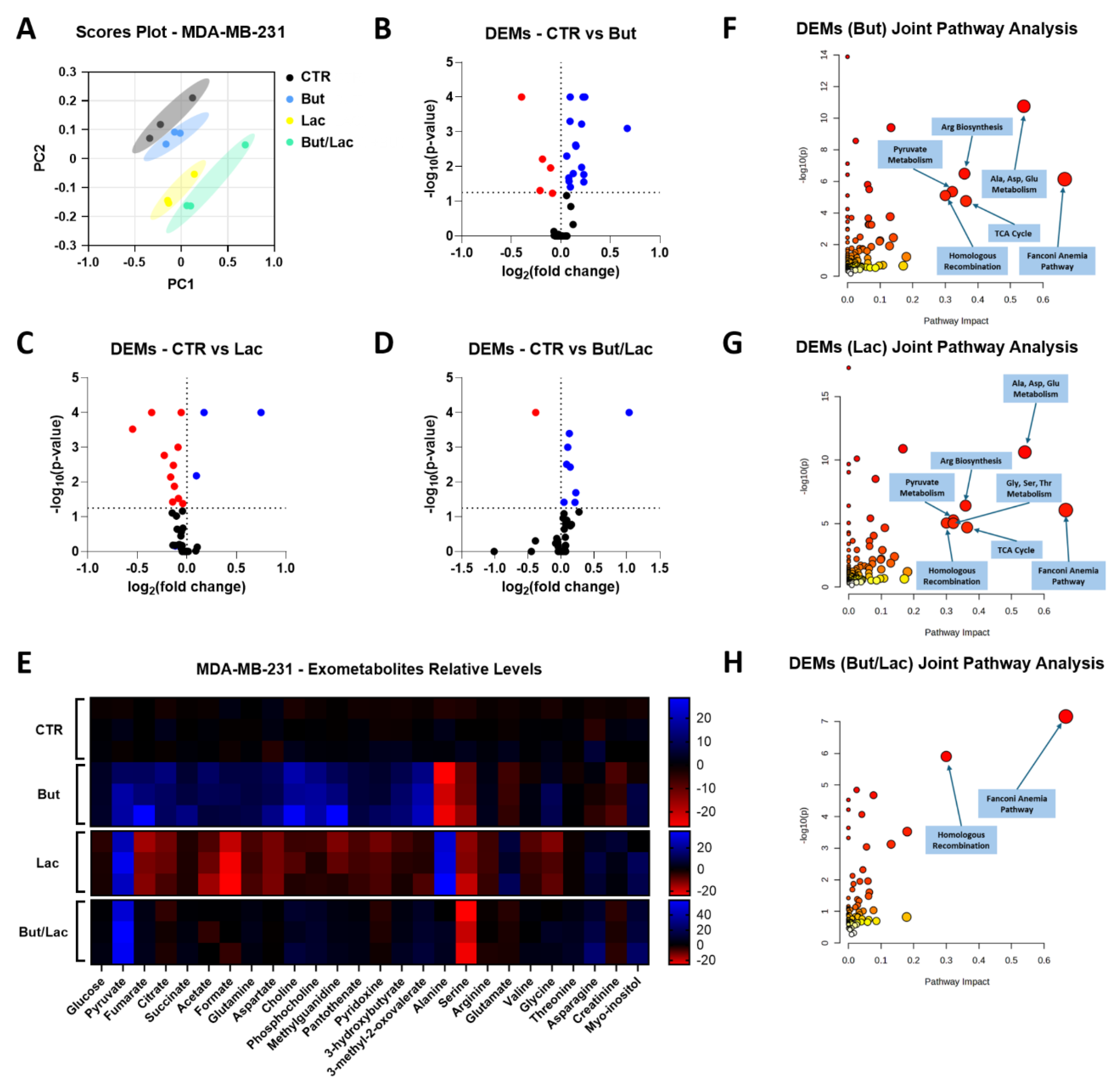

2.5. Butyrate and Lactate Induce Distinct Exometabolomic Changes Consistent with Their Effects on HR

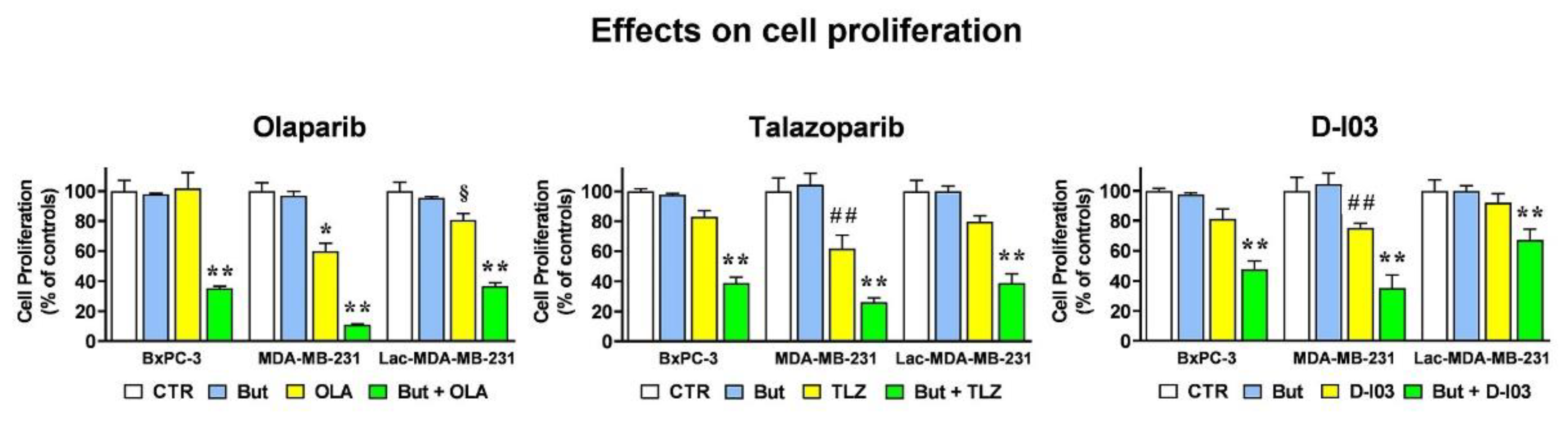

2.6. The HR-Modulatory Effects of Butyrate and Lactate Modify CELL response to PARP and RAD52 Inhibitors

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Cultures and Treatments

4.2. Cell Proliferation Experiments

4.3. Evaluation of Lactate Level

4.4. Real-Time PCR

4.5. Immunoblotting Experiments

4.6. Homologous Recombination Assay

4.7. NMR Exometabolomic Analysis

4.8. Statistical Analyses

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| But CDDP |

Butyrate Cisplatin |

| DSB FA HDAC |

Double Strand Breaks Fanconi Anemia Histone Deacetylase |

| HR Lac |

Homologous Recombination Lactate |

| LDH OXA PARPi RT-PCR |

Lactate Dehydrogenase Oxamate Poly-ADP-Ribose Polymerase Inhibitor Real Time PCR |

References

- Hornisch, M.; Piazza, I. Regulation of gene expression through protein-metabolite interactions. NPJ Metab. Health Dis. 2025, 3, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Knaap, J.A.; Verrijzer, C.P. Undercover: gene control by metabolites and metabolic enzymes. Genes Dev. 2016, 30, 2345–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govoni, M.; Rossi, V.; Di Stefano, G.; Manerba, M. Lactate Upregulates the Expression of DNA Repair Genes, Causing Intrinsic Resistance of Cancer Cells to Cisplatin. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2021, 27, 1609951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, V.; Govoni, M.; Farabegoli, F.; Di Stefano, G. Lactate is a potential promoter of tamoxifen resistance in MCF7 cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2022, 1866, 130185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, V.; Govoni, M.; Di Stefano, G. Lactate Can Modulate the Antineoplastic Effects of Doxorubicin and Relieve the Drug’s Oxidative Damage on Cardiomyocytes. Cancers 2023, 15, 3728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, V.; Hochkoeppler, A.; Govoni, M.; Di Stefano, G. Lactate-Induced HBEGF Shedding and EGFR Activation: Paving the Way to a New Anticancer Therapeutic Opportunity. Cells 2024, 13, 1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, L.; Supuran, C.T.; Alfarouk, K.O. The Warburg Effect and the Hallmarks of Cancer. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2017, 17, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Tang, Z.; Huang, H.; Zhou, G.; Cui, C.; Weng, Y.; Liu, W.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.; Perez-Neut, M.; et al. Metabolic regulation of gene expression by histone lactylation. Nature 2019, 574, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, N.T.B.; Gevers, S.; Kok, R.N.U.; Burgering, L.M.; Neikes, H.; Akkerman, N.; Betjes, M.A.; Ludikhuize, M.C.; Gulersonmez, C.; Stigter, E.C.A.; et al. Lactate controls cancer stemness and plasticity through epigenetic regulation. Cell Metab. 2025, 37, 903–919.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Su, J.; Wang, S.; Su, X.; Ding, X.; Jiang, L.; Fei, X.; Zhang, W. Lactate-induced activation of tumor-associated fibroblasts and IL-8-mediated macrophage recruitment promote lung cancer progression. Redox Biol. 2024, 74, 103209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdeen, S.K.; Mastandrea, I.; Stinchcombe, N.; Puschhof, J.; Elinav, E. Diet-microbiome interactions in cancer. Cancer Cell 2025, 43, 680–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Chen, S.; Zang, D.; Sun, H.; Sun, Y.; Chen, J. Butyrate as a promising therapeutic target in cancer: From pathogenesis to clinic (Review). Int. J. Oncol. 2024, 64, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davie, J.R. Inhibition of histone deacetylase activity by butyrate. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 2485S–2493S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruemmele, F.M.; Schwartz, S.; Seidman, E.G.; Dionne, S.; Levy, E.; Lentze, M.J. Butyrate induced Caco-2 cell apoptosis is mediated via the mitochondrial pathway. Gut 2003, 52, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernhard, D.; Ausserlechner, M.J.; Tonko, M.; Löffler, M.; Hartmann, B.L.; Csordas, A.; Kofler, R. Apoptosis induced by the histone deacetylase inhibitor sodium butyrate in human leukemic lymphoblasts. FASEB J. 1999, 13, 1991–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, C.; Jiang, Q.; Yin, Y. Butyrate in Energy Metabolism: There Is Still More to Learn. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 32, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Qin, Y.; Sun, X.; Bian, Z.; Liu, L.; Liu, H.; Mao, L.; Sun, S. Sodium butyrate blocks colorectal cancer growth by inhibiting aerobic glycolysis mediated by SIRT4/HIF-1α. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2024, 403, 111227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoêdo, N.D.; Rodrigues, M.F.; Pezzuto, P.; Galina, A.; da Costa, R.M.; de Almeida, F.C.; El-Bacha, T.; Rumjanek, F.D. Energy metabolism in H460 lung cancer cells: effects of histone deacetylase inhibitors. PLoS One 2011, 6, e22264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Liu, C.X.; Xu, W.; Huang, L.; Zhao, J.Y.; Zhao, S.M. Butyrate induces apoptosis by activating PDC and inhibiting complex I through SIRT3 inactivation. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2017, 2, 16035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balboni, A.; Govoni, M.; Rossi, V.; Roberti, M.; Cavalli, A.; Di Stefano, G.; Manerba, M. Lactate dehydrogenase inhibition affects homologous recombination repair independently of cell metabolic asset. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2021, 1865, 129760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, Y.; Wu, W.; Ni, X.; Kuang, T.; Jin, D.; Wang, D.; Lou, W. Lactate dehydrogenase A is overexpressed in pancreatic cancer and promotes cancer cell growth. Tumour Biol. 2013, 34, 1523–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover-McKay, M.; Walsh, S.A.; Seftor, E.A.; Thomas, P.A.; Hendrix, M.J. Role for glucose transporter 1 protein in human breast cancer. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 1998, 4, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phannasil, P.; Thuwajit, C.; Warnnissorn, M.; Wallace, J.C.; MacDonald, M.J.; Jitrapakdee, S.; dos Santos, M.P.; Schwartsmann, G.; Roesler, R.; Brunetto, A.L.; et al. Pyruvate Carboxylase Is Up-Regulated in Breast Cancer. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0129848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Cruz-López, K.G.; Castro-Muñoz, L.J.; Reyes-Hernández, D.O.; García-Carrancá, A.; Manzo-Merino, J. Lactate in the.

- regulation of tumor microenvironment and therapeutic approaches. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 1143. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- dos Santos, M.P.; Schwartsmann, G.; Roesler, R.; Brunetto, A.L.; Abujamra, A.L. Sodium butyrate enhances the cytotoxic effect of antineoplastic drugs in human lymphoblastic T-cells. Leuk. Res. 2009, 33, 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, M.; Rosato, R.R.; Battaglia, E.; Néguesque, A.; Lapotre, A.; Grant, S.; Bagrel, D. Modulation of sensitivity to doxorubicin by sodium butyrate in breast cancer cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2005, 26, 1569–1574. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Peng, J.; Cui, Y.; Xu, S.; Wu, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, W.; Wang, S.; Fu, Z.; Xie, H. Altered glycolysis results in drug-resistant tumors. Oncol. Lett. 2021, 21, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firsanov, D.V.; Solovjeva, L.V.; Svetlova, M.P. H2AX phosphorylation at DNA double-strand breaks. Clin. Epigenet. 2011, 2, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloss, C.M.; Wang, F.; Palladino, M.A.; Cusack, J.C. Activation of EGFR by proteasome inhibition requires HB-EGF. Oncogene 2010, 29, 3146–3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zach, L.; Yedidia-Aryeh, L.; Goldberg, M. Estrogen and DNA damage modulate mRNA levels of genes involved in homologous recombination repair. J. Transl. Genet. Genom. 2022, 6, 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldon, C.E. Estrogen signaling and DNA damage response in breast cancers. Front. Oncol. 2014, 4, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yedidia-Aryeh, L.; Goldberg, M. The interplay between the response to DNA double-strand breaks and estrogen. Cells 2022, 11, 3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, T.; Ushikubo, G.; Arao, N.; Hatabi, K.; Tsubota, K.; Hosoi, Y. Oxamate inhibits stemness and radiosensitizes glioblastoma cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberti, M.; Schipani, F.; Bagnolini, G.; Milano, D.; Giacomini, E.; Falchi, F.; Balboni, A.; Manerba, M.; Farabegoli, F.; De Franco, F.; et al. Rad51/BRCA2 disruptors synergize with olaparib in pancreatic cancer. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 165, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schipani, F.; Manerba, M.; Marotta, R.; Poppi, L.; Gennari, A.; Rinaldi, F.; Armirotti, A.; Farabegoli, F.; Roberti, M.; Di Stefano, G.; et al. Mechanistic understanding of RAD51 defibrillation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S.H.; Poppi, L.; Rinaldi, F.; Veronesi, M.; Ciamarone, A.; Previtali, V.; Bagnolini, G.; Schipani, F.; Ortega Martínez, J.A.; Girotto, S.; et al. An 19F NMR fragment-based approach for the discovery and development of BRCA2-RAD51 inhibitors to pursuit synthetic lethality in combination with PARP inhibition in pancreatic cancer. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 265, 116114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, M.; Poppi, L.; Previtali, V.; Nelson, S.R.; Wynne, K.; Varignani, G.; Falchi, F.; Veronesi, M.; Albanesi, E.; Tedesco, D.; et al. Investigating synthetic lethality and PARP inhibitor resistance in pancreatic cancer through enantiomer differential activity. Cell Death Discov. 2025, 11, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milordini, G.; Zacco, E.; Masi, M.; Armaos, A.; Di Palma, F.; Oneto, M.; Gilodi, M.; Rupert, J.; Broglia, L.; Varignani, G.; et al. Computationally-designed aptamers targeting RAD51-BRCA2 interaction impair homologous recombination and induce synthetic lethality. Nat. Commun. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.J.; Mann, E.; Wright, G.; Piett, C.G.; Nagel, Z.D.; Gassman, N.R. Exploiting DNA repair defects in triple negative breast cancer to improve cell killing. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2020, 12, 1758835920958354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michl, J.; Zimmer, J.; Tarsounas, M. Interplay between Fanconi anemia and homologous recombination pathways in genome integrity. EMBO J. 2016, 35, 909–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishiai, M.; Kitao, H.; Smogorzewska, A.; Tomida, J.; Kinomura, A.; Uchida, E.; Saberi, A.; Kinoshita, E.; Kinoshita-Kikuta, E.; Koike, T.; et al. FANCI phosphorylation functions as a molecular switch to turn on the Fanconi anemia pathway. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008, 15, 1138–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Chen, X.; Fu, H.; Mao, D.; Chen, W.; Lan, L.; Wang, C.; Hu, K.; et al. NBS1 lactylation is required for efficient DNA repair and chemotherapy resistance. Nature 2024, 631, 663–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cucchi, D.; Gibson, A.; Martin, S.A. The emerging relationship between metabolism and DNA repair. Cell Cycle 2021, 20, 943–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koprinarova, M.; Botev, P.; Russev, G. Histone deacetylase inhibitor sodium butyrate enhances cellular radiosensitivity by inhibiting both DNA non homologous end joining and homologous recombination. DNA Repair (Amst) 2011, 10, 970–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groselj, B.; Sharma, N.L.; Hamdy, F.C.; Kerr, M.; Kiltie, A.E. Histone deacetylase inhibitors as radiosensitisers: effects on DNA damage signalling and repair. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 108, 748–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, H.W.; Yin, F.Y.; Zhang, Z.F.; Gong, X.; Yang, Y. Butyrate suppresses glucose metabolism of colorectal cancer cells via GPR109a-AKT signaling pathway and enhances chemotherapy. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 634874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemma, S.; Di Pompo, G.; Porporato, P.E.; Sboarina, M.; Russell, S.; Gillies, R.J.; Baldini, N.; Sonveaux, P.; Avnet, S. MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells fuel osteoclast metabolism and activity: A new rationale for the pathogenesis of osteolytic bone metastases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2017, 1863, 3254–3264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Guo, Z.; Cheng, J.; Sun, B.; Yang, J.; Li, H.; Wu, S.; Dong, F.; Yan, X. Differential metabolic responses in breast cancer cell lines to acidosis and lactic acidosis revealed by stable isotope assisted metabolomics. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhai, L.; Zhang, T.; Yin, H.; Gao, H.; Zhao, F.; Wang, Z.; Yang, X.; Jin, M.; et al. Metabolic regulation of homologous recombination repair by MRE11 lactylation. Cell 2024, 187, 294–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romick-Rosendale, L.E.; Lui, V.W.Y.; Grandis, J.R.; Wells, S.I. The Fanconi anemia pathway: repairing the link between DNA damage and squamous cell carcinoma. Mutat. Res. 2013, 743-744, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michl, J.; Zimmer, J.; Tarsounas, M. Interplay between Fanconi anemia and homologous recombination pathways in genome integrity. EMBO J. 2016, 35, 909–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petropoulos, M.; Karamichali, A.; Rossetti, G.G.; Freudenmann, A.; Iacovino, L.G.; Dionellis, V.S.; Sotiriou, S.K.; Halazonetis, T.D. Transcription-replication conflicts underlie sensitivity to PARP inhibitors. Nature 2024, 628, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carley, A.C.; Jalan, M.; Subramanyam, S.; Roy, R.; Borgstahl, G.E.O.; Powell, S.N. Replication Protein A Phosphorylation Facilitates RAD52-Dependent Homologous Recombination in BRCA-Deficient Cells. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 42, e0052421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyck, E.; Stasiak, A.Z.; Stasiak, A.; West, S.C. Binding of double-strand breaks in DNA by human Rad52 protein. Nature 1999, 398, 728–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Goyal, N.; Sullivan, K.; Hanamshet, K.; Patel, M.; Mazina, O.M.; Wang, C.X.; An, W.F.; Spoonamore, J.; Metkar, S.; et al. Targeting BRCA1- and BRCA2-deficient cells with RAD52 small molecule inhibitors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 4189–4199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Luo, Y.; Qian, B.; Cao, X.; Xu, C.; Guo, K.; Wan, R.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, T.; Mei, Z.; et al. A systematic pan-cancer analysis identifies LDHA as a novel predictor for immunological, prognostic, and immunotherapy resistance. Aging (Albany NY) 2024, 16, 8000–8018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiume, L.; Manerba, M.; Vettraino, M.; Di Stefano, G. Inhibition of lactate dehydrogenase activity as an approach to cancer therapy. Future Med. Chem. 2014, 6, 429–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhou, Q.; Cao, T.; Li, F.; Li, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, Y. Lactate dehydrogenase A: a potential new target for tumor drug resistance intervention. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Yruela, C.; Zhang, D.; Wei, W.; Bæk, M.; Liu, W.; Gao, J.; Danková, D.; Nielsen, A.L.; Bolding, J.E.; Yang, L.; et al. Class I histone deacetylases (HDAC1-3) are histone lysine delactylases. Sci Adv. 2022, 8(3), eabi6696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davie, J.R. Inhibition of histone deacetylase activity by butyrate. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 2485S–2493S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louis, P.; Flint, H.J. Formation of propionate and butyrate by the human colonic microbiota. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 19, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalile, B.; Van Oudenhove, L.; Vervliet, B.; Verbeke, K. The role of short-chain fatty acids in microbiota-gut-brain communication. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 461–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donohoe, D.R.; Garge, N.; Zhang, X.; Sun, W.; O’Connell, T.M.; Bunger, M.K.; Bultman, S.J. The microbiome and butyrate regulate energy metabolism and autophagy in the mammalian colon. Cell Metab. 2011, 13, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavaleri, F.; Bashar, E. Potential Synergies of β-Hydroxybutyrate and Butyrate on Metabolism, Inflammation, Cognition, and General Health. J. Nutr. Metab. 2018, 2018, 7195760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, M.T.; Cresci, G.A.M. The Immunomodulatory Functions of Butyrate. J. Inflamm. Res. 2021, 14, 6025–6041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egorin, M.J.; Yuan, Z.M.; Sentz, D.L.; Plaisance, K.; Eiseman, J.L. Plasma pharmacokinetics of butyrate after intravenous administration of sodium butyrate or oral administration of tributyrin or sodium butyrate to mice and rats. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 1999, 43, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleophas, M.C.P.; Ratter, J.M.; Bekkering, S.; Quintin, J.; Schraa, K.; Stroes, E.S.; Netea, M.G.; Joosten, L.A.B. Effects of oral butyrate supplementation on inflammatory potential of circulating peripheral blood mononuclear cells in healthy and obese males. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cait, A.; Cardenas, E.; Dimitriu, P.A.; Amenyogbe, N.; Dai, D.; Cait, J.; Sbihi, H.; Stiemsma, L.; Subbarao, P.; Mandhane, P.J. Reduced genetic potential for butyrate fermentation in the gut microbiome of infants who develop allergic sensitization. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 144, 1638–1647.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roduit, C.; Frei, R.; Ferstl, R.; Loeliger, S.; Westermann, P.; Rhyner, C.; Schiavi, E.; Barcik, W.; Rodriguez-Perez, N.; Wawrzyniak, M.; et al. High levels of butyrate and propionate in early life are associated with protection against atopy. Allergy 2019, 74, 799–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalkan, A.E.; BinMowyna, M.N.; Raposo, A.; Ahmad, M.F.; Ahmed, F.; Otayf, A.Y.; Carrascosa, C.; Saraiva, A.; Karav, S. Beyond the Gut: Unveiling Butyrate’s Global Health Impact Through Gut Health and Dysbiosis-Related Conditions. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattorusso, A.; Di Genova, L.; Dell’Isola, G.B.; Mencaroni, E.; Esposito, S. Autism Spectrum Disorders and the Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2019, 11, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.-F.; Shen, Y.-Q. Dysbiosis of gut microbiota and microbial metabolites in Parkinson’s Disease. Ageing Res. Rev. 2018, 45, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Gao, J.; Zhu, M.; Liu, K.; Zhang, H.-L. Gut Microbiota and Dysbiosis in Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2020, 57, 5026–5043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zapolska-Downar, D.; Siennicka, A.; Kaczmarczyk, M.; Kołodziej, B.; Naruszewicz, M. Butyrate inhibits cytokine-induced VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 expression in cultured endothelial cells. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2004, 15, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailón, E.; Cueto-Sola, M.; Utrilla, P.; Rodríguez-Cabezas, M.E.; Garrido-Mesa, N.; Zarzuelo, A.; Xaus, J.; Gálvez, J.; Comalada, M. Butyrate in vitro immune-modulatory effects might be mediated through apoptosis induction. Immunobiology 2010, 215, 863–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, E.C.; Leonel, A.J.; Teixeira, L.G.; Silva, A.R.; Silva, J.F.; Pelaez, J.M.; Capettini, L.S.; Lemos, V.S.; Santos, R.A.; Alvarez-Leite, J.I. Butyrate impairs atherogenesis by reducing plaque inflammation and NFκB activation. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2014, 24, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagnolini, G.; Milano, D.; Manerba, M.; Schipani, F.; Ortega, J.A.; Gioia, D.; Falchi, F.; Balboni, A.; Farabegoli, F.; De Franco, F.; et al. Synthetic lethality in pancreatic cancer: discovery of a new RAD51–BRCA2 small molecule disruptor that inhibits homologous recombination and synergizes with olaparib. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 2588–2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene | ID | Forward (5′-3′) | Reverse (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RAD51 | NM_001164269 | CAAATGCAGATACTTCAGTGGAA | TCCAGCTTCTTCCAATTTCTTCA |

| BRCA1 | NM_007294 | TATCCGCTGCTTTGTCCTCA | TGCAGGAAACCAGTCTCAGT |

| BRCA2 | NM_000059 | GAGAGTTCCCAGGCCAGTA | ACTGGAAAGGTTAAGCGTCA |

| uPA | NM_001145031 | GAAAACCTCATCCTACACAAG | ATTCTCTTTTCCAAAGCCAG |

| GPER1 | NM_001039966 | TTCCGCGAGAAGATGACCATCC | TAGTACCGCTCGTGCAGGTTGA |

| CYP33A (PPIE) | NM_006112 | GCTGCCTGTGCACTCATGAA | CAGTGCCATTGTGGTTTGTGA |

| RPLP0 | NR_002775 | CAGATTGGCTACCCAACTGTT | GGCCAGGACTCGTTTGTACC |

| B2M | NM_004048 | CATTCCTGAAGCTGACAGCATTC | TGCTGGATGACGTGAGTA |

| Experiments | Antibody | Host Species | Catalog No. | Producer | Dilution | Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IB, primary | PUMA α / β | Mouse | Sc-374223 | Santa Cruz(a) | 1:500 | 16h (4 °C) |

| Lactyl-H3 | Rabbit | A21214 | ABClonal(b) | 1:3000 | 1h | |

| RAD51 | Rabbit | 70-012 | Bio Academia(c) | 1:1000 | 1h | |

| BRCA1 | Rabbit | 22362-1-AP | Proteintech(d) | 1:2000 | 16h (4 °C) | |

| BRCA2 | Rabbit | 9012 | Cell Signaling(e) | 1:1000 | 1h | |

| BRCA2* | Rabbit | A2435 | ABClonal | 1:750 | 16h (4 °C) | |

| GPER1 | Rabbit | A10217 | ABClonal | 1:1000 | 1h | |

| γ-H2AX | Rabbit | Ab11174 | Abcam(f) | 1:2000 | 1h | |

| FANCI | Rabbit | Ab245219 | Abcam | 1:1000 | 16h (4 °C) | |

| FAND2 | Rabbit | Ab178705 | Abcam | 1:2500 | 16h (4 °C) | |

| Actin | Rabbit | A2066 | Merck | 1:1000 | 2h | |

| IB, secondary | Rabbit IgG Cy5-labeled |

Goat | 111-175-144 | Jackson Immuno Research(g) |

1:2500 | 1h |

| Mouse IgG Alexa-Fluor 647-labeled |

Donkey | 715-605-151 | Jackson Immuno Research |

1:1000 | 1h |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).