Submitted:

19 December 2025

Posted:

22 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Background

Common Metabolic Diseases/Disorders Associated with ADPKD

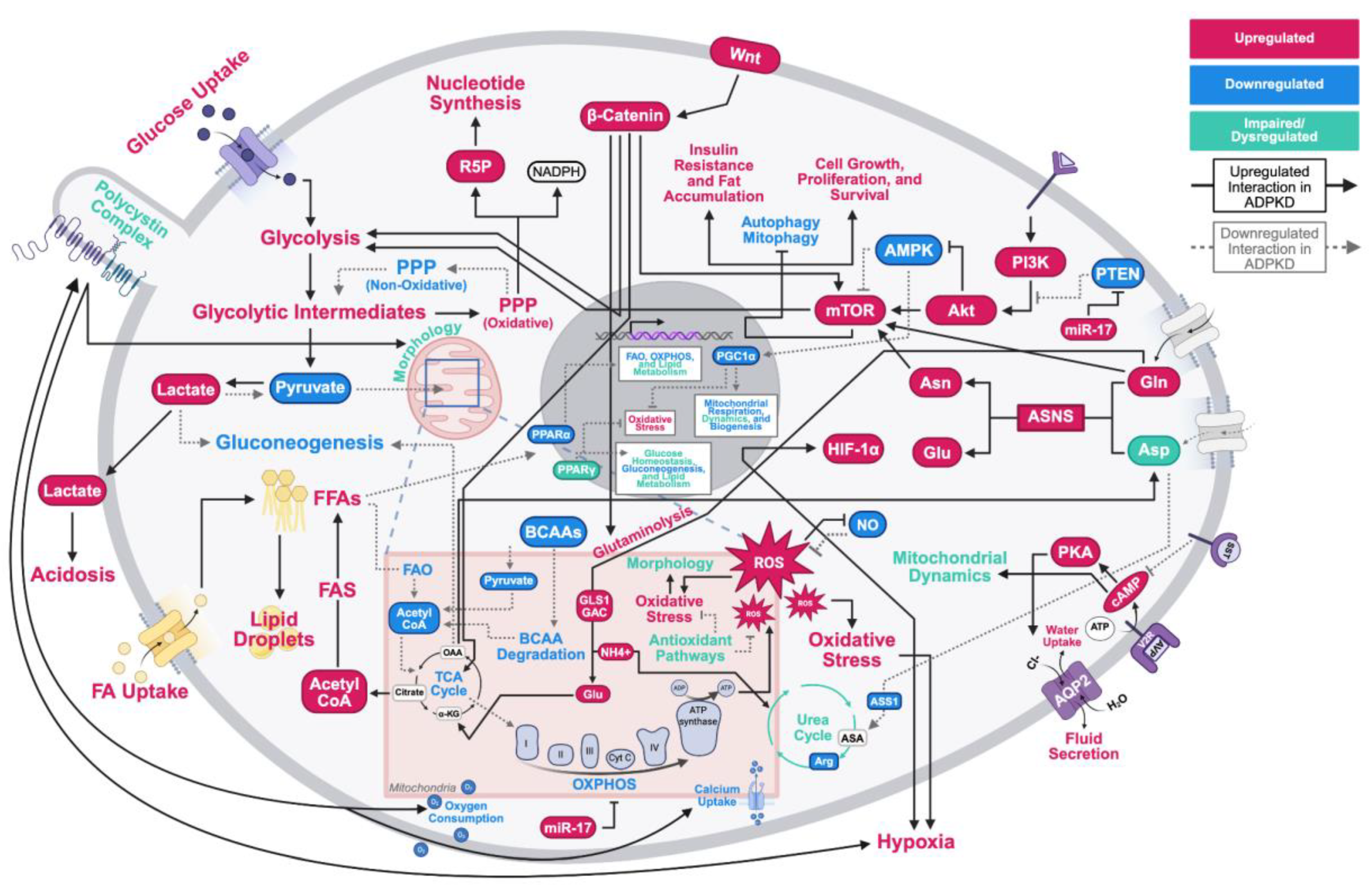

Metabolic Reprogramming in ADPKD

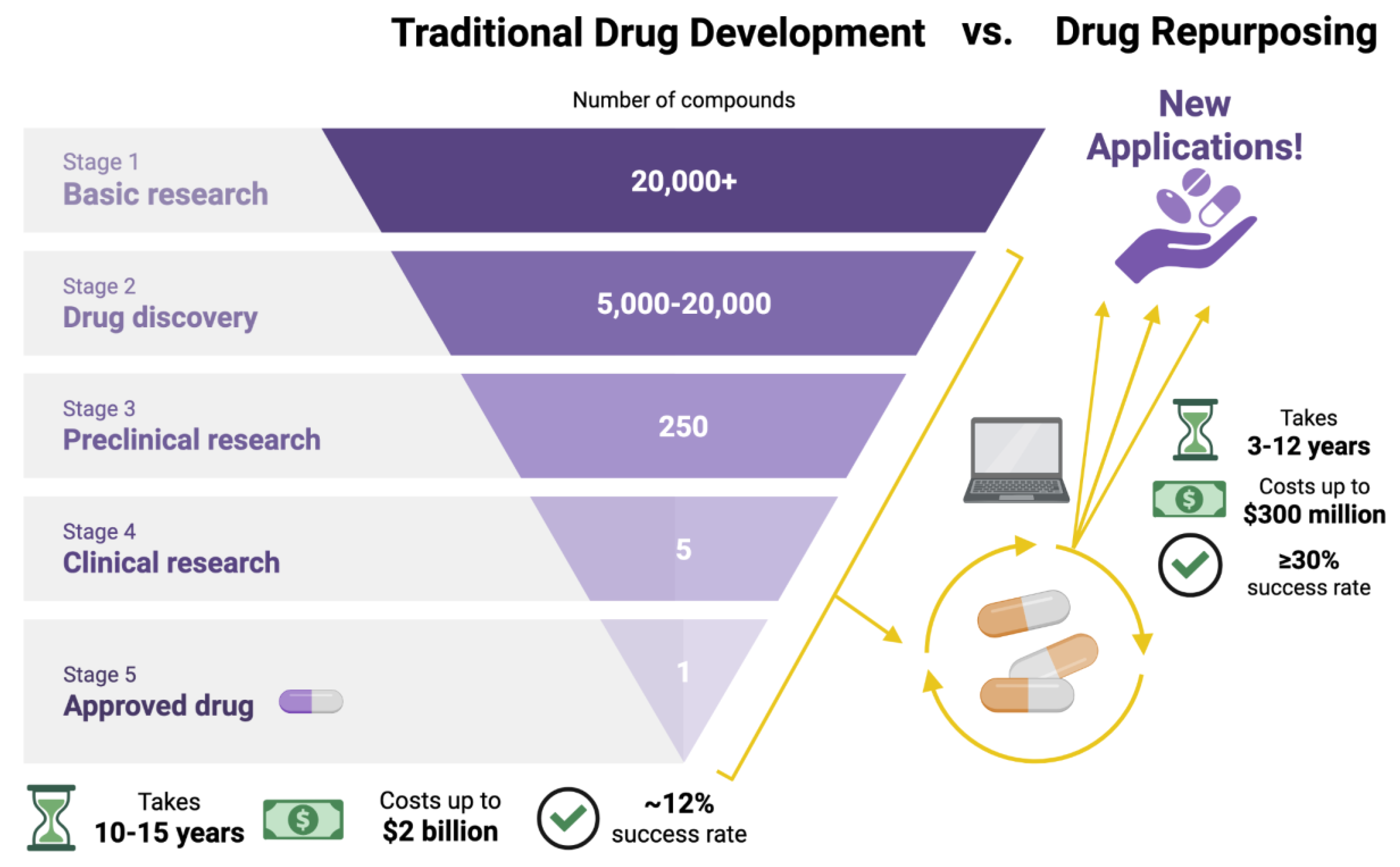

Established ADPKD Drug Targets

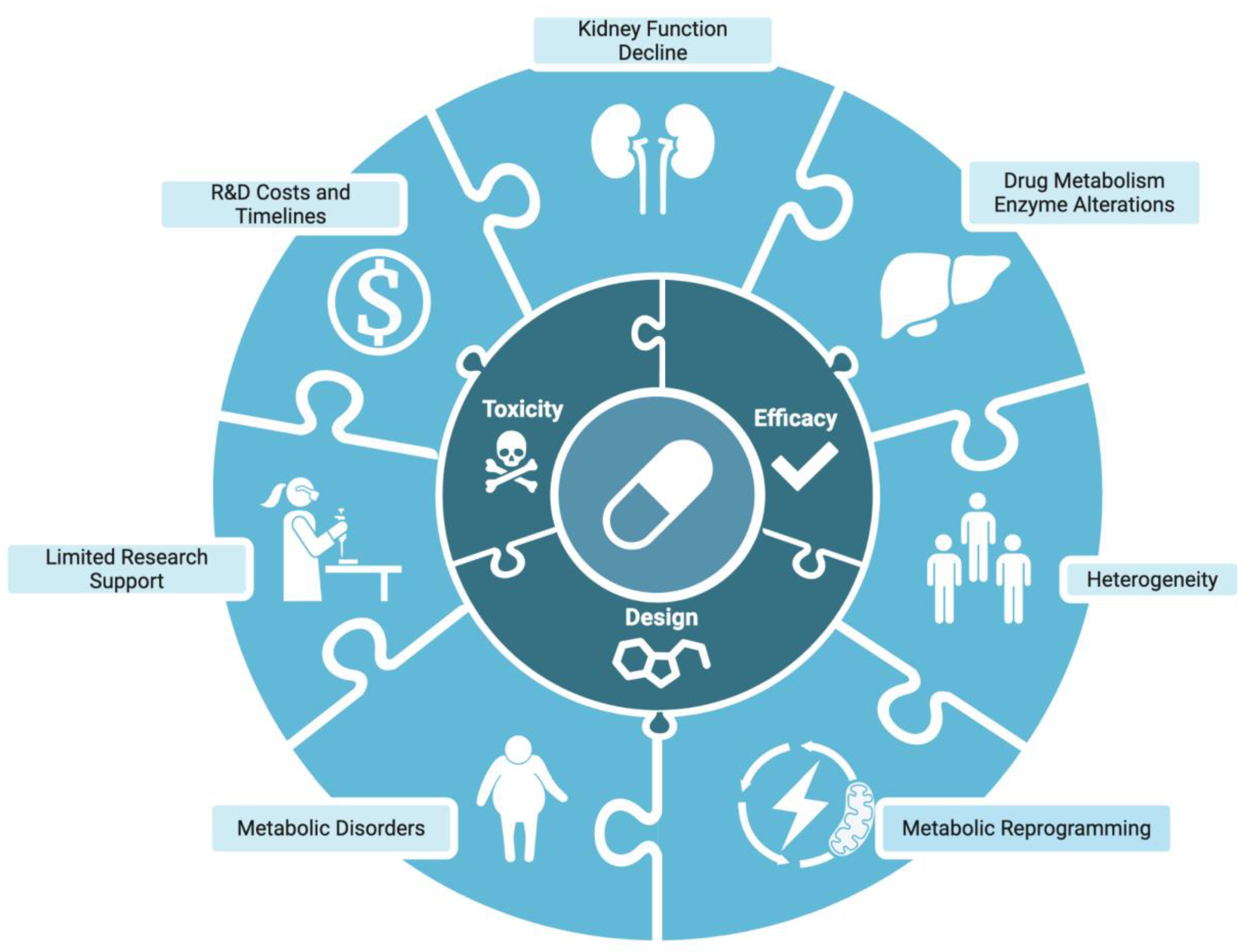

ADPKD Impact on Drug Development and Metabolism

Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Directions

Disclosures

Author Contributions

Acknowledgements

References

- Chapman, AB; Devuyst, O; Eckardt, KU; et al. Autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD): executive summary from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int. 2015, 88(1), 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahboob, M; Rout, P; Leslie, SW; Bokhari, SRA. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing, 2025; Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532934/.

- Nowak, KL; Hopp, K. Metabolic reprogramming in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: Evidence and therapeutic potential. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020, 15(4), 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, CC; Kurashige, M; Liu, Y; et al. A cleavage product of Polycystin-1 is a mitochondrial matrix protein that affects mitochondria morphology and function when heterologously expressed. Sci Rep. 2018, 8(1), 2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, Z; Xie, G; Ong, A. Metabolic abnormalities in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015, 30(2), 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available Treatment. Polycystic kidney disease | PKD treatment research | PKD Foundation. 11 April 2020. Available online: https://pkdcure.org/about-the-disease/living-with-pkd/treatments/ (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Cloutier, M; Manceur, AM; Guerin, A; Aigbogun, MS; Oberdhan, D; Gauthier-Loiselle, M. The societal economic burden of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease in the United States. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020, 20(1), 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellos, I. Safety profile of tolvaptan in the treatment of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2021, 17, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebib, FT; Perrone, RD; Chapman, AB; et al. A practical guide for treatment of rapidly progressive ADPKD with tolvaptan. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018, 29(10), 2458–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claverie-Martin, F; Gonzalez-Paredes, FJ; Ramos-Trujillo, E. Splicing defects caused by exonic mutations in PKD1 as a new mechanism of pathogenesis in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. RNA Biol. 2015, 12(4), 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, J. A comprehensive review on metabolic syndrome. Cardiol Res Pract. 2014, 2014, 943162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrzak-Nowacka, M; Safranow, K; Byra, E; Bińczak-Kuleta, A; Ciechanowicz, A; Ciechanowski, K. Metabolic syndrome components in patients with autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2009, 32(6), 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeramuthumari, P; Isabel, W. Clinical study on autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease among south Indians. Int J Clin Med. 2013, 04(04), 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, LC; Chu, YC; Lu, T; Lin, HYH; Chan, TC. Cardiometabolic comorbidities in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: a 16-year retrospective cohort study. BMC Nephrol. 2023, 24(1), 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Mattos, AM; Olyaei, AJ; Prather, JC; Golconda, MS; Barry, JM; Norman, DJ. Autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease as a risk factor for diabetes mellitus following renal transplantation. Kidney Int. 2005, 67(2), 714–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietrzak-Nowacka, M; Rózanski, J; Safranow, K; Kedzierska, K; Dutkiewicz, G; Ciechanowski, K. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease reduces the risk of diabetes mellitus. Arch Med Res. 2006, 37(3), 360–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, B; Helal, I; McFann, K; Wang, W; Yan, XD; Schrier, RW. The impact of type II diabetes mellitus in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012, 27(7), 2862–2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vareesangthip, K; Tong, P; Wilkinson, R; Thomas, TH. Insulin resistance in adult polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 1997, 52(2), 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrzak-Nowacka, M; Safranow, K; Byra, E; Nowosiad, M; Marchelek-Myśliwiec, M; Ciechanowski, K. Glucose metabolism parameters during an oral glucose tolerance test in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2010, 70(8), 561–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fliser, D; Pacini, G; Engelleiter, R; et al. Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia are already present in patients with incipient renal disease. Kidney Int. 1998, 53(5), 1343–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipp, KR; Rezaei, M; Lin, L; Dewey, EC; Weimbs, T. A mild reduction of food intake slows disease progression in an orthologous mouse model of polycystic kidney disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016, 310(8), F726–F731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, G; Hein, KZ; Nin, V; et al. Food restriction ameliorates the development of polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016, 27(5), 1437–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopp, K; Catenacci, VA; Dwivedi, N; et al. Weight loss and cystic disease progression in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. iScience 2022, 25(1), 103697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberti, MV; Locasale, JW. The Warburg Effect: How does it benefit cancer cells? Trends Biochem Sci. 2016, 41(3), 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X; Pickel, L; Sung, HK; Scholey, J; Pei, Y. Reprogramming of energy metabolism in human PKD1 polycystic kidney disease: A systems biology analysis. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25(13), 7173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riwanto, M; Kapoor, S; Rodriguez, D; Edenhofer, I; Segerer, S; Wüthrich, RP. Inhibition of aerobic glycolysis attenuates disease progression in polycystic kidney disease. PLoS One 2016, 11(1), e0146654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, S; Dagar, N; Shelke, V; Lech, M; Khare, P; Gaikwad, AB. Metabolic reprogramming: Unveiling the therapeutic potential of targeted therapies against kidney disease. Drug Discov Today 2023, 28(11), 103765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maser, RL; Vassmer, D; Magenheimer, BS; Calvet, JP. Oxidant stress and reduced antioxidant enzyme protection in polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002, 13(4), 991–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J; Ouyang, X; Schoeb, TR; et al. Kidney injury accelerates cystogenesis via pathways modulated by heme oxygenase and complement. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012, 23(7), 1161–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahveci, AS; Barnatan, TT; Kahveci, A; et al. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial abnormalities contribute to decreased endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression and renal disease progression in early experimental Polycystic Kidney Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21(6), 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, KA; Grande, J; Croatt, A; Haugen, J; Kim, Y; Rosenberg, ME. Redox regulation of renal DNA synthesis, transforming growth factor-beta1 and collagen gene expression. Kidney Int. 1998, 53(2), 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soomro, I; Sun, Y; Li, Z; et al. Glutamine metabolism via glutaminase 1 in autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2018, 33(8), 1343–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barmore, W; Azad, F; Stone, WL. Physiology, urea cycle. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing, 2025; Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513323/ (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Trott, JF; Hwang, VJ; Ishimaru, T; et al. Arginine reprogramming in ADPKD results in arginine-dependent cystogenesis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2018, 315(6), F1855–F1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heida, JE; Gansevoort, RT; Messchendorp, AL; et al. Use of the urine-to-plasma urea ratio to predict ADPKD progression. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021, 16(2), 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menezes, LF; Zhou, F; Patterson, AD; et al. Network analysis of a Pkd1-mouse model of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease identifies HNF4α as a disease modifier. PLoS Genet. 2012, 8(11), e1003053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podrini, C; Cassina, L; Boletta, A. Metabolic reprogramming and the role of mitochondria in polycystic kidney disease. Cell Signal. 2020, 67(109495), 109495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, LF; Lin, CC; Zhou, F; Germino, GG. Fatty acid oxidation is impaired in an orthologous mouse model of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. EBioMedicine 2016, 5, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podrini, C; Rowe, I; Pagliarini, R; et al. Dissection of metabolic reprogramming in polycystic kidney disease reveals coordinated rewiring of bioenergetic pathways. Commun Biol. 2018, 1(1), 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padovano, V; Kuo, IY; Stavola, LK; et al. The polycystins are modulated by cellular oxygen-sensing pathways and regulate mitochondrial function. Mol Biol Cell. 2017, 28(2), 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchholz, B; Eckardt, KU. Role of oxygen and the HIF-pathway in polycystic kidney disease. Cell Signal. 2020, 69(109524), 109524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassina, L; Chiaravalli, M; Boletta, A. Increased mitochondrial fragmentation in polycystic kidney disease acts as a modifier of disease progression. FASEB J 2020, 34(5), 6493–6507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, IY; Brill, AL; Lemos, FO; et al. Polycystin 2 regulates mitochondrial Ca2+ signaling, bioenergetics, and dynamics through mitofusin 2. Sci Signal. 2019, 12(580), eaat7397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chumley, P; Zhou, J; Mrug, S; et al. Truncating PKHD1 and PKD2 mutations alter energy metabolism. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2019, 316(3), F414–F425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picard, M; McEwen, BS. Psychological stress and mitochondria: A systematic review. Psychosom Med. 2018, 80(2), 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devlin, L; Dhondurao Sudhindar, P; Sayer, JA. Renal ciliopathies: promising drug targets and prospects for clinical trials. Expert Opin Ther Targets 2023, 27(4-5), 325–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margaria, JP; Campa, CC; De Santis, MC; Hirsch, E; Franco, I. The PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in polycystic kidney disease: A complex interaction with polycystins and primary cilium. Cell Signal. 2020, 66(109468), 109468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwar, V; Singh, A; Bhatt, M; et al. Multifaceted role of mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) signaling pathway in human health and disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023, 8(1), 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A; Fan, S; Xu, Y; et al. Rapamycin treatment dose-dependently improves the cystic kidney in a new ADPKD mouse model via the mTORC1 and cell-cycle-associated CDK1/cyclin axis. J Cell Mol Med. 2017, 21(8), 1619–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y; Pejchinovski, M; Wang, X; et al. Dual mTOR/PI3K inhibition limits PI3K-dependent pathways activated upon mTOR inhibition in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Sci Rep. 2018, 8(1), 5584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y; Shi, T; Cui, X; et al. Asparagine reinforces mTORC1 signaling to boost thermogenesis and glycolysis in adipose tissues. EMBO J 2021, 40(24), e108069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clerici, S; Podrini, C; Stefanoni, D; et al. Inhibition of asparagine synthetase effectively retards polycystic kidney disease progression. EMBO Mol Med. 2024, 16(6), 1379–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bais, T; Gansevoort, RT; Meijer, E. Drugs in clinical development to treat autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Drugs 2022, 82(10), 1095–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, JD, Jr.; Fitch, AC; Lee, JK; et al. AMP-activated protein kinase phosphorylation of the R domain inhibits PKA stimulation of CFTR. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009, 297(1), C94–C101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallows, KR; Raghuram, V; Kemp, BE; Witters, LA; Foskett, JK. Inhibition of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator by novel interaction with the metabolic sensor AMP-activated protein kinase. J Clin Invest. 2000, 105(12), 1711–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gwinn, DM; Shackelford, DB; Egan, DF; et al. AMPK phosphorylation of raptor mediates a metabolic checkpoint. Mol Cell. 2008, 30(2), 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sethi, JK; Vidal-Puig, A. Wnt signalling and the control of cellular metabolism. Biochem J 2010, 427(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, M; Song, X; Pluznick, JL; et al. Polycystin-1 C-terminal tail associates with beta-catenin and inhibits canonical Wnt signaling. Hum Mol Genet. 2008, 17(20), 3105–3117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliarini, R; Podrini, C. Metabolic reprogramming and reconstruction: Integration of experimental and computational studies to set the path forward in ADPKD. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021, 8, 740087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W; Evans, R. PPARs and ERRs: molecular mediators of mitochondrial metabolism. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2015, 33, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, KW; Lee, EK; Lee, MK; Oh, GT; Yu, BP; Chung, HY. Impairment of PPARα and the fatty acid oxidation pathway aggravates renal fibrosis during aging. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018, 29(4), 1223–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, HM; Ahn, SH; Choi, P; et al. Defective fatty acid oxidation in renal tubular epithelial cells has a key role in kidney fibrosis development. Nat Med. 2015, 21(1), 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhia, R. The role of PPARα in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2020, 29(4), 432–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z; Valluru, MK; Ong, ACM. Drug repurposing in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: back to the future with pioglitazone. Clin Kidney J. 2021, 14(7), 1715–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chambers, JM; Wingert, RA. PGC-1α in disease: Recent renal insights into a versatile metabolic regulator. Cells 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishimoto, Y; Inagi, R; Yoshihara, D; et al. Mitochondrial abnormality facilitates cyst formation in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Mol Cell Biol. 2017, 37(24). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, EC; Valencia, T; Allerson, C; et al. Discovery and preclinical evaluation of anti-miR-17 oligonucleotide RGLS4326 for the treatment of polycystic kidney disease. Nat Commun. 2019, 10(1), 4148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajarnis, S; Lakhia, R; Yheskel, M; et al. microRNA-17 family promotes polycystic kidney disease progression through modulation of mitochondrial metabolism. Nat Commun. 2017, 8(1), 14395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messchendorp, AL; Casteleijn, NF; Meijer, E; Gansevoort, RT. Somatostatin in renal physiology and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020, 35(8), 1306–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Benedetto, G; Gerbino, A; Lefkimmiatis, K. Shaping mitochondrial dynamics: The role of cAMP signalling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018, 500(1), 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinzi, L; Bisi, N; Rastelli, G. How drug repurposing can advance drug discovery: challenges and opportunities. Front Drug Discov (Lausanne) 2024, 4, 1460100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, EA; Rissmann, R; Cohen, AF. Tolvaptan: New drug mechanisms. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012, 73(1), 9–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilk, EJ; Howton, TC; Fisher, JL; et al. Prioritized polycystic kidney disease drug targets and repurposing candidates from pre-cystic and cystic mouse Pkd2 model gene expression reversion. Mol Med. 2023, 29(1), 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garza, AZ; Park, SB; Kocz, R. Drug elimination. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing, 2025; Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK547662/ (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Arjune, S; Todorova, P; Bartram, MP; Grundmann, F; Müller, RU. Liver manifestations in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) and their impact on quality of life. Clin Kidney J. 2025, 18(1), sfae363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, MC; Abebe, K; Torres, VE; et al. Liver involvement in early autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015, 13(1), 155–164.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea-Henry, TN; Carland, JE; Stocker, SL; Sevastos, J; Roberts, DM. Clinical pharmacokinetics in kidney disease: Fundamental principles. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018, 13(7), 1085–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreisbach, AW; Lertora, JJL. The effect of chronic renal failure on drug metabolism and transport. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2008, 4(8), 1065–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillmann, AC; Rostami-Hodjegan, A; Barber, J; Al-Majdoub, ZM. Pharmacotherapy in kidney disease: what it takes to move from general guidance to specific recommendations to stratified subgroups of patients - the tale of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD). Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2025, 21(6), 677–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillmann AC, Peters DJM, Rostami-Hodjegan A, et al. Changes in protein expression of renal drug transporters and drug-metabolizing enzymes in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease patients. Clin Pharmacol Ther. Published online May 15, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Beaudoin, JJ; Bezençon, J; Cao, Y; et al. Altered hepatobiliary disposition of tolvaptan and selected tolvaptan metabolites in a rodent model of polycystic kidney disease. Drug Metab Dispos. 2019, 47(2), 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Drug Evaluation; Research. Pharmacokinetics in Patients with Impaired Renal Function — Study Design, Data Analysis, and Impact on Dosing. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 29 July 2024. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/pharmacokinetics-patients-impaired-renal-function-study-design-data-analysis-and-impact-dosing (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Sieben, CJ; Harris, PC. Experimental models of polycystic kidney disease: Applications and therapeutic testing. Kidney360 2023, 4(8), 1155–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones E, Taluri S, Wilk E, Lasseigne B. Streamlining drug repurposing: Optimizing candidate prioritization to facilitate clinical adoption and minimize attrition rates. Preprints. Published online November 21, 2024. [CrossRef]

| Drug Class | Molecular Target / MOA | Drug Compound | Original Indication | Results | Clinical Trials / Relevant DOIs |

| Vaptans | |||||

| V2R / Antagonist | Tolvaptan | Hypervolemic or euvolemic hyponatremia | Tolvaptan significantly reduced the rate of TKV growth and eGFR decline (P<0.001) compared to the placebo. Patients in the tolvaptan group had a higher frequency of aquaresis- and hepatic-related adverse events. | TEMPO (NCT00428948); REPRISE (NCT02160145); doi:10.1056/NEJMoa120551; doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1710030 | |

| Lixivaptan | Euvolemic hyponatremia | Terminated early by sponsor due to concerns about commercial potential and hepatic safety. | ACTION (NCT04064346); ALERT (NCT04152837) | ||

| Rapalogs | |||||

| mTORC1 / Antagonist | Everolimus | Advanced renal cell carcinoma after failure of sunitinib or sorafenib treatment | Everolimus significantly slowed TKV increase (P=0.02) in the first year but was associated with a significantly greater decline in eGFR (P=0.004) compared with placebo. | NCT00414440; doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1003491 | |

| Sirolimus | Prophylaxis of organ rejection in renal transplant patients | Sirolimus treatment increased TKV and TCV and did not significantly affect eGFR. Incidence of gastrointestinal adverse events in treated patients was high (94%). SIRENA-II was terminated early due to increased adverse events and ESRD progression in treated participants. A later study found that low-dose oral sirolimus is associated with ovarian toxicity, menstrual cycle disturbances, and ovarian cysts. | SIRENA-II (NCT01223755); NCT00346918; doi:10.2215/CJN.09900915; doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0907419; doi:10.1093/ndt/gfp280; doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0045868 | ||

| Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids | |||||

| PPAR family / Agonist | Gamolenic acid | Atopic dermatitis/eczema; Asthma; Rheumatoid arthritis | Identified as a potential ADPKD treatment option in a drug repurposing study. Reduced cyst size in renal epithelial cells grown in a 3D-gel matrix. | doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.11.046 | |

| Icosapent ethyl / Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) | Hypertriglycidemia | Part of a larger clinical trial investigating the use of calcium channel blockers for the treatment of hypertension in ADPKD patients. EPA administration over 2 years did not have a significant effect on renal function decline or kidney enlargement. | NCT00541853; doi:10.1093/ndt/gfn144 | ||

| Fibrates | |||||

| PPAR-α / Agonist | Fenofibrate | Hypertriglyceridemia; Primary hypercholesterolemia; Mixed dyslipidemia | In a preclinical trial on Pkd1^RC/RC mice, treatment with fenofibrate reduced TKV by 26.9%, TCV by 60.9%, liver fibrosis by 40%, and cyst proliferation by 71.6% compared to the control group. | doi:10.1152/ajprenal.00352.2017 | |

| Thiazolidinediones | |||||

| PPAR-γ / Agonist | Pioglitazone | T2DM | Low-dose pioglitazone was associated with reduced TKV growth rate compared to the placebo; however, the study was underpowered. Due to concerns over side effects with higher doses and preclinical data showing maximal efficacy at a low dose, the study did not examine higher dosages. | NCT02697617; doi:10.1093/ckj/sfaa232 | |

| Rosiglitazone | In human cystic epithelial cell culture models, rosiglitazone reduced the expression of fibrotic markers and cell proliferation. Male heterozygous Han:SPRD rats treated with rosiglitazone had improved kidney-to-body weight ratios and delayed ADPKD progression. | doi:10.1152/ajprenal.00194.2015 | |||

| Biguanides | |||||

| AMPK / Agonist | Metformin | Malaria; T2DM | Metformin treatment was well tolerated in ADPKD patients. Changes in htTKV (p=0.9) and eGFR (p=0.2) were not statistically significant, but eGFR decline was reduced in the metformin group compared to placebo (-0.41±1.81 vs -3.35±1.70 mL/min/1.73 m^2). Starting kidney size, hypertension, and disease stage may have influenced this difference. | TAME-PKD (NCT02656017); IMPEDE-PKD (NCT04939935); NCT02903511; doi:10.34067/KID.0004002020; doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2021.06.026 | |

| Glucose Analogs | |||||

| Glycolysis / Antagonist | 2-deoxy-d-glucose (2DG) | Cancer | In a preclinical Pkd1^(ΔC/flox)TmCre murine model, 2DG administration restored AMPK activation, reduced kidney-to-body weight ratio, and was associated with improved kidney function preservation. Mice treated with 2DG additionally had reduced cyst expansion in both distal tubules and collecting ducts. | doi:10.1681/ASN.2015030231 | |

| Somatostatin Analogs | |||||

| SSTR1-5 / Agonist | Octreotide | Acromegaly; Thyrotrophinomas | Octreotide-LAR significantly decreased TKV growth in both studies after one year (P=0.002, P=0.04) and at three years in ALADIN (P=0.04). ALADIN found the octreotide-LAR group had reduced eGFR decline, while ALADIN 2 found a higher rate of eGFR decline compared to the placebo (11.3% vs 7.0%). Octreotide treatment was associated with cholelithiasis and cholecystitis adverse events. | ALADIN (NCT00309283); ALADIN 2 (NCT01377246); doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61407-5; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002777 | |

| Lanreotide | Acromegaly; Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors | Lanreotide treatment significantly lowered the percent change in htTKV (P=0.02), with a 24% reduction in htTKV growth rate compared to the placebo. There was a high incidence of adverse events in the treatment group, leading 10% of patients to withdraw from the study. 28% of treated patients experienced serious adverse events. An interim analysis of DIPAK-1 concluded somatostatin analog use is associated with an increased risk of hepatic cyst infection. | DIPAK-1 (NCT01616927); doi:10.1001/jama.2018.15870; doi:10.1007/s40264-016-0486-x | ||

| Pasireotide | Acromegaly; Cushing's disease | In patients with ADPKD/ADPLD with severe liver involvement, pasireotide-LAR treatment was associated with a significant decrease in TLV (P<0.001) and TKV (P=0.02). Adverse events were most commonly related to hyperglycemia, and 19/32 (59%) of treated patients developed diabetes compared to 1/15 (7%) of patients in the placebo group (P<0.001). | NCT01670110; doi:10.2215/CJN.13661119 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).