Submitted:

19 December 2025

Posted:

22 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

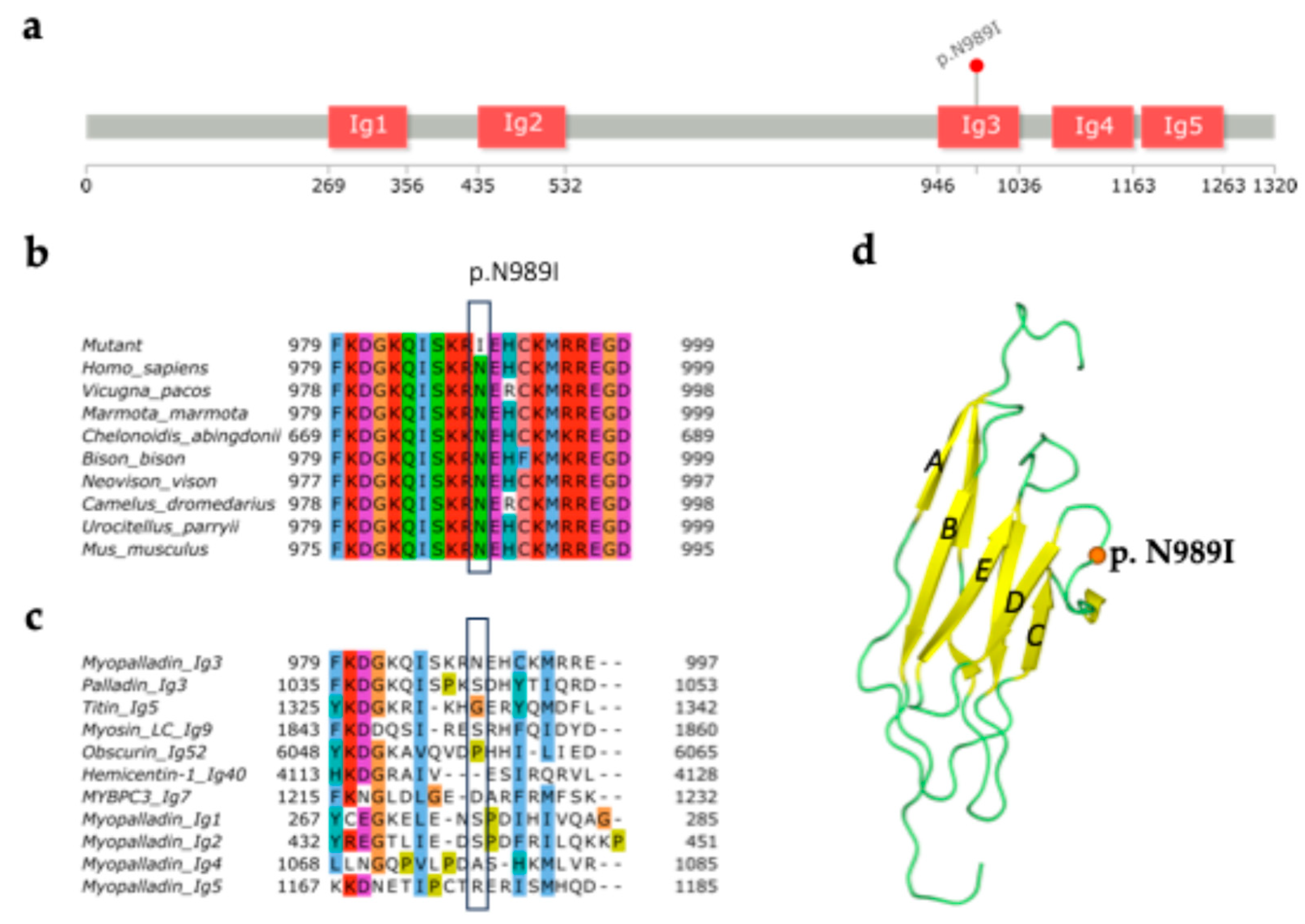

2.1. Structural Analysis of MYPN-N989I Variant

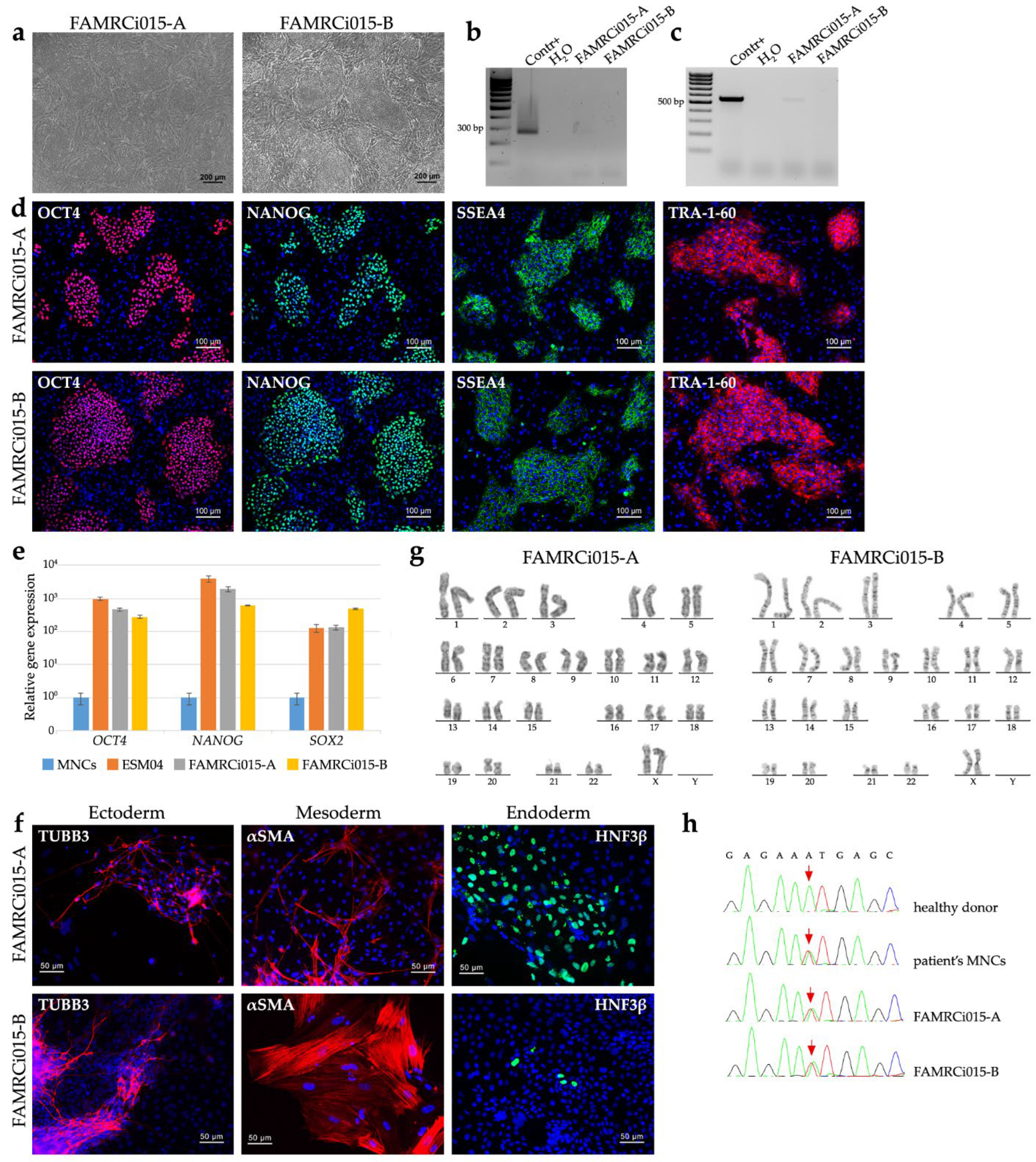

2.2. Generation of MYPN-N989I iPSC Lines and Directed Differentiation into Cardiomyocytes

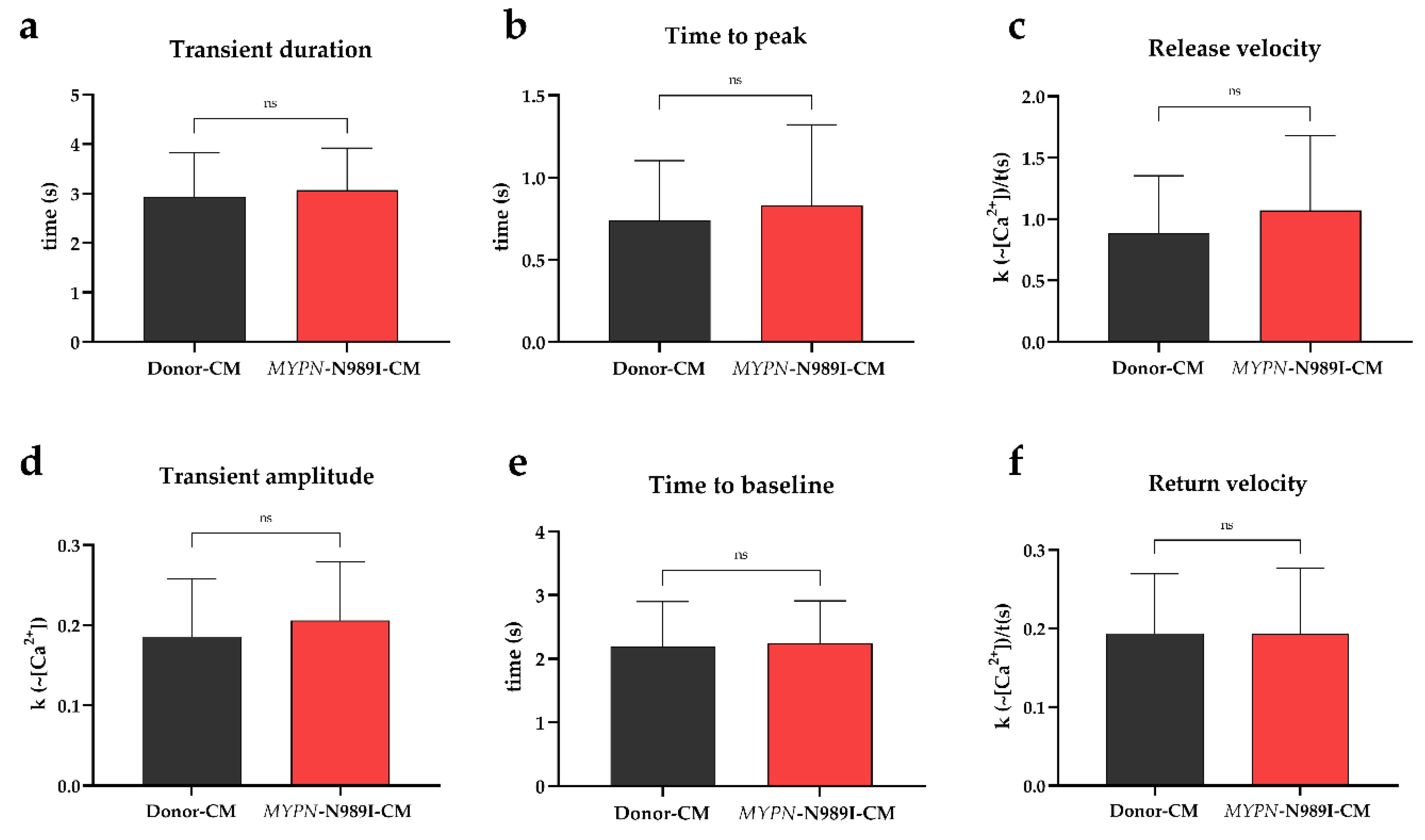

2.3. Calcium Dynamics Is Not Altered in iPSC-Derived Cardiomyocytes with p.N989I Variant in MYPN

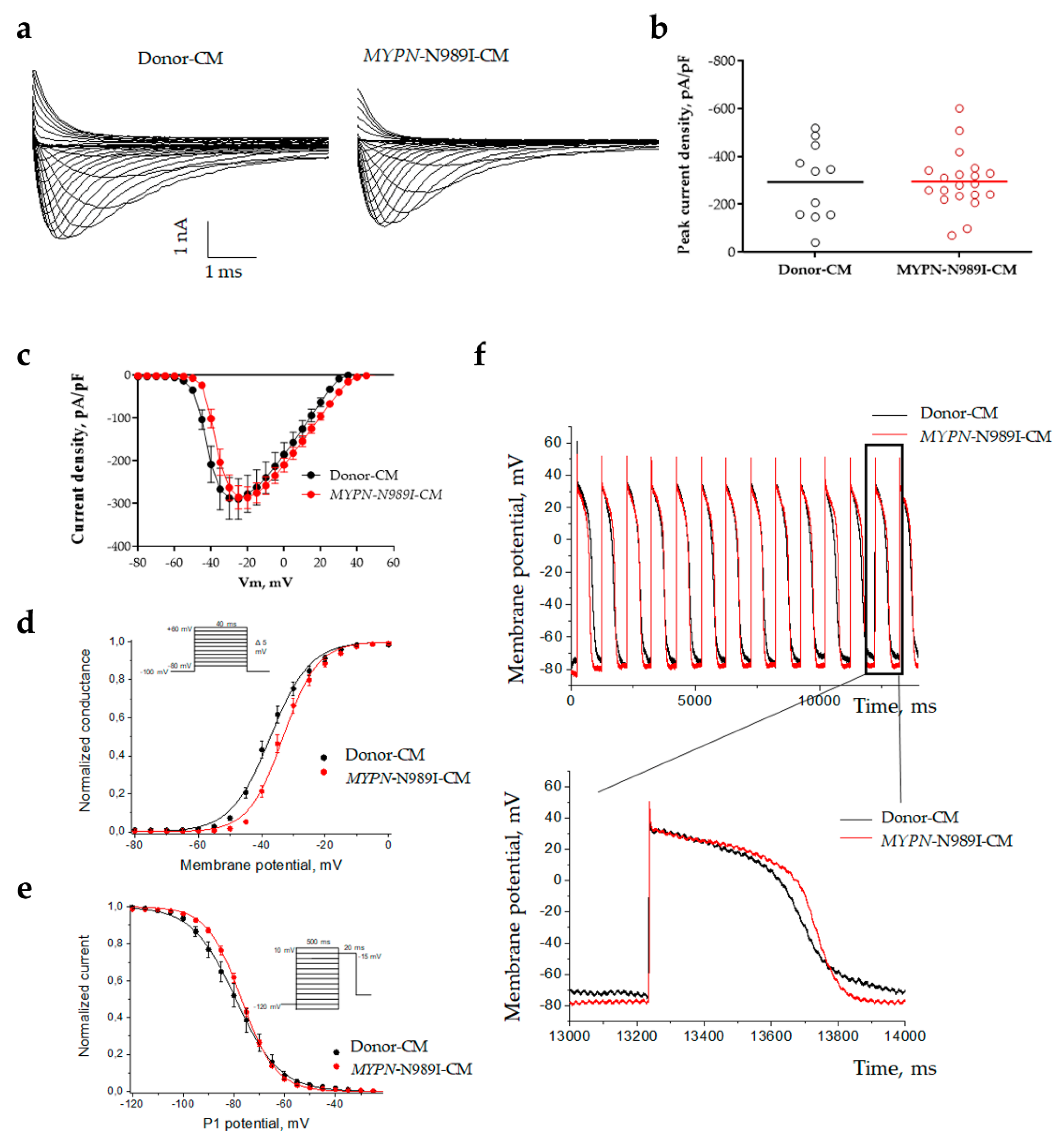

2.4. MYPN-N989I-Cardiomyocytes Do Not Demonstrate Any Significant Changes in Characteristics of Sodium Current and Action Ponential

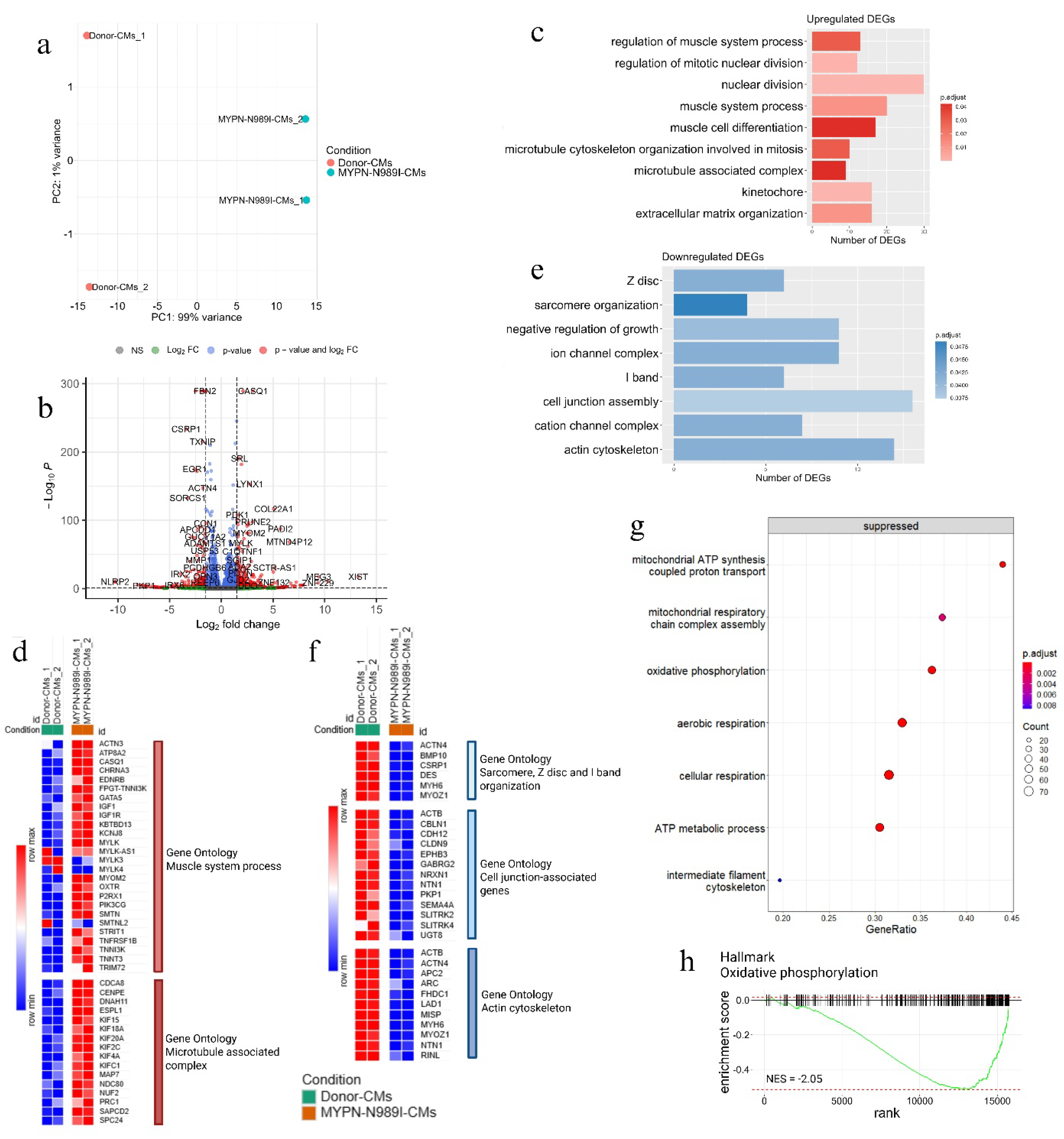

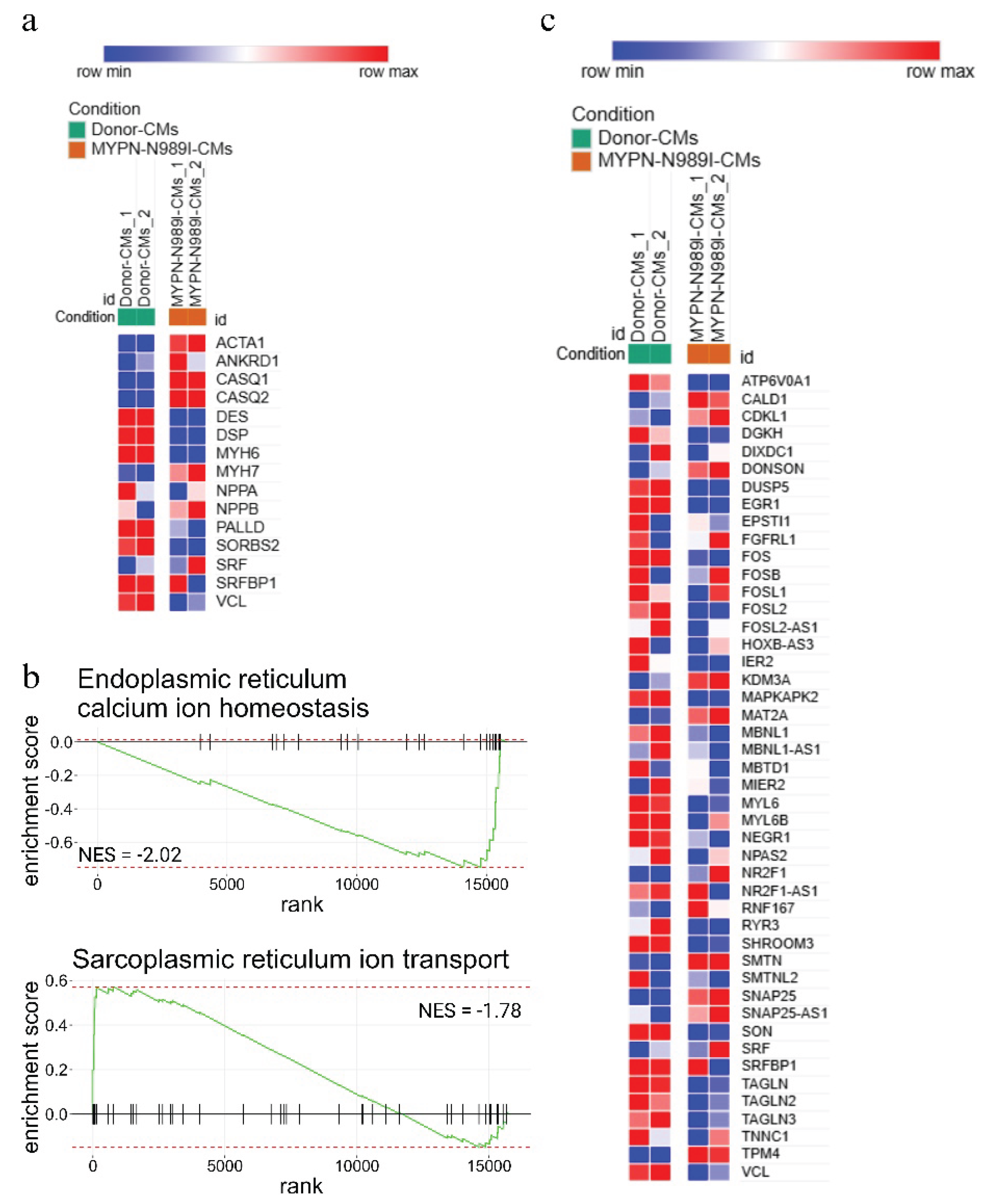

2.5. iPSC-Derived Cardiomyocytes with p.N989I Variant in MYPN Revealed a Dysregulation of Several Signaling Pathways

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sequence and Structural Analysis of Human Myopalladin and Variant Classification

4.2. iPSC Generation

4.3. Mycoplasma and Episome Detection

4.4. Spontaneous In Vitro Differentiation

4.5. Immunofluorescent Staining

4.6. RT-qPCR

4.7. Karyotyping

4.8. Analysis of the Patient-Specific Variant

4.9. STR Analysis

4.10. Directed iPSC Differentiation into Cardiomyocytes

4.11. Calcium Dynamic with STIMULATION

4.12. Electrophysiology

4.13. Patch-Clamp Data Analyses

4.14. RNA Sequencing and Bioinformatics Analysis

4.15. Statistics

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bang, M.L.; Mudry, R.E.; McElhinny, A.S.; Trombitás, K.; Geach, A.J.; Yamasaki, R.; Sorimachi, H.; Granzier, H.; Gregorio, C.C.; Labeit, S. Myopalladin, a novel 145-kilodalton sarcomeric protein with multiple roles in Z-disc and I-band protein assemblies. J. Cell Biol. 2001, 153, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filomena, M.C.; Yamamoto, D.L.; Carullo, P.; Medvedev, R.; Ghisleni, A.; Piroddi, N.; Scellini, B.; Crispino, R.; D'Autilia, F.; Zhang, J.; et al. Myopalladin knockout mice develop cardiac dilation and show a maladaptive response to mechanical pressure overload. Elife 2021, 10, e58313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filomena, M.C.; Yamamoto, D.L.; Caremani, M.; Kadarla, V.K.; Mastrototaro, G.; Serio, S.; Vydyanath, A.; Mutarelli, M.; Garofalo, A.; Pertici, I.; et al. Myopalladin promotes muscle growth through modulation of the serum response factor pathway. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2020, 11, 169–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagnall, R.D.; Yeates, L.; Semsarian, C. Analysis of the Z-disc genes PDLIM3 and MYPN in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Int. J. Cardiol. 2010, 145, 601–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purevjav, E.; Arimura, T.; Augustin, S.; Huby, A.C.; Takagi, K.; Nunoda, S.; Kearney, D.L.; Taylor, M.D.; Terasaki, F.; Bos, J.M.; et al. Molecular basis for clinical heterogeneity in inherited cardiomyopathies due to myopalladin mutations. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012, 21, 2039–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, T.; Ruppert, V.; Ackermann, S.; Richter, A.; Perrot, A.; Sperling, S.R.; Posch, M.G.; Maisch, B.; Pankuweit, S. German Competence Network Heart Failure. Novel mutations in the sarcomeric protein myopalladin in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2013, 21, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, Y.M.; Ding, X.X.; Song, Y.Z.; Zhang, A.M.; Liu, L.; Zhang, H.; Ding, J.H.; Xia, X.S. Targeted next-generation sequencing of candidate genes reveals novel mutations in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2015, 36, 1479–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duboscq-Bidot, L.; Xu, P.; Charron, P.; Neyroud, N.; Dilanian, G.; Millaire, A.; Bors, V.; Komajda, M.; Villard, E. Mutations in the Z-band protein myopalladin gene and idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc. Res. 2008, 77, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vershinina, T.; Fomicheva, Y.; Muravyev, A.; Jorholt, J.; Kozyreva, A.; Kiselev, A.; Gordeev, M.; Vasichkina, E.; Segrushichev, A.; Pervunina, T.; et al. Genetic Spectrum of Left Ventricular Non-Compaction in Paediatric Patients. Cardiology 2020, 145, 746–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lornage, X.; Malfatti, E.; Chéraud, C.; Schneider, R.; Biancalana, V.; Cuisset, J.M.; Garibaldi, M.; Eymard, B.; Fardeau, M.; Boland, A.; et al. Recessive MYPN mutations cause cap myopathy with occasional nemaline rods. Ann. Neurol. 2017, 81, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dementyeva, E.V.; Vyatkin, Y.V.; Kretov, E.I.; Elisaphenko, E.A.; Medvedev, S.P.; Zakian, S.M. Genetic analysis of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Genes and Cells 2020, 15, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagwan, J.R.; Mosqueira, D.; Chairez-Cantu, K.; Mannhardt, I.; Bodbin, S.E.; Bakar, M.; Smith, J.G.W.; Denning, C. Isogenic models of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy unveil differential phenotypes and mechanism-driven therapeutics. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2020, 145, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafaattalab, S.; Li, A.Y.; Gunawan, M.G.; Kim, B.; Jayousi, F.; Maaref, Y.; Song, Z.; Weiss, J.N.; Solaro, R.J.; Qu, Z.; Tibbits, G.F. Mechanisms of Arrhythmogenicity of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy-Associated Troponin T (TNNT2) Variant I79N. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 787581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vander Roest, A.S.; Liu, C.; Morck, M.M.; Kooiker, K.B.; Jung, G.; Song, D.; Dawood, A.; Jhingran, A.; Pardon, G.; Ranjbarvaziri, S.; et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy β-cardiac myosin mutation (P710R) leads to hypercontractility by disrupting super relaxed state. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2021, 118, e2025030118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escribá, R.; Larrañaga-Moreira, J.M.; Richaud-Patin, Y.; Pourchet, L.; Lazis, I.; Jiménez-Delgado, S.; Morillas-García, A.; Ortiz-Genga, M.; Ochoa, J.P.; Carreras, D.; et al. iPSC-Based Modeling of Variable Clinical Presentation in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Circ. Res. 2023, 133, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loiben, A.M.; Chien, W.M.; Friedman, C.E.; Chao, L.S.; Weber, G.; Goldstein, A.; Sniadecki, N.J.; Murry, C.E.; Yang, K.C. Cardiomyocyte Apoptosis Is Associated with Contractile Dysfunction in Stem Cell Model of MYH7 E848G Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, D.; Song, T.; Singh, R.R.; Baby, A.; McNamara, J.; Green, L.C.; Nabavizadeh, P.; Ericksen, M.; Bazrafshan, S.; Natesan, S.; Sadayappan, S. MYBPC3 D389V Variant Induces Hypercontractility in Cardiac Organoids. Cells 2024, 13, 1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, G.; Wang, L.; Li, X.; Fu, W.; Cao, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, M.; Wang, M.; Zhao, G.; et al. Enhanced myofilament calcium sensitivity aggravates abnormal calcium handling and diastolic dysfunction in patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes with MYH7 mutation. Cell Calcium 2024, 117, 102822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.; Mangala, M.M.; Holliday, M.; Cserne Szappanos, H.; Barratt-Ross, S.; Li, S.; Thorpe, J.; Liang, W.; Ranpura, G.N.; Vandenberg, J.I.; et al. Reduced connexin-43 expression, slow conduction and repolarisation dispersion in a model of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Dis. Model Mech. 2024, 17, dmm050407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, H.; Xu, D.; Shimoda, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Murakata, Y.; Xi, B.; Sato, K.; Yamamoto, M.; Tajiri, K.; Ishizu, T.; et al. Metabolic remodeling and calcium handling abnormality in induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes in dilated phase of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with MYBPC3 frameshift mutation. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 15422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlova, S.V.; Shulgina, A.E.; Zakian, S.M.; Dementyeva, E.V. Studying Pathogenetic Contribution of a Variant of Unknown Significance, p.M659I (c.1977G > A) in MYH7, to the Development of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Using CRISPR/Cas9-Engineered Isogenic Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steczina, S.; Mohran, S.; Bailey, L.R.J.; McMillen, T.S.; Kooiker, K.B.; Wood, N.B.; Davis, J.; Previs, M.J.; Olivotto, I.; Pioner, J.M.; et al. MYBPC3-c.772G>A mutation results in haploinsufficiency and altered myosin cycling kinetics in a patient induced stem cell derived cardiomyocyte model of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2024, 191, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, M.R.; Dixon, R.D.; Goicoechea, S.M.; Murphy, G.S.; Brungardt, J.G.; Beam, M.T.; Srinath, P.; Patel, J.; Mohiuddin, J.; Otey, C.A.; Campbell, S.L. Structure and function of palladin's actin binding domain. J. Mol. Biol. 2013, 425, 3325–3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, M.; Andreeva, A.; Florentino, L.C.; Chuguransky, S.R.; Grego, T.; Hobbs, E.; Pinto, B.L.; Orr, A.; Paysan-Lafosse, T.; Ponamareva, I.; et al. InterPro: the protein sequence classification resource in 2025. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D444–D456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jay, J.J.; Brouwer, C. Lollipops in the Clinic: Information Dense Mutation Plots for Precision Medicine. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0160519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okita, K.; Yamakawa, T.; Matsumura, Y.; Sato, Y.; Amano, N.; Watanabe, A.; Goshima, N.; Yamanaka, S. An efficient nonviral method to generate integration-free human-induced pluripotent stem cells from cord blood and peripheral blood cells. Stem Cells 2013, 31, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burridge, P.W.; Matsa, E.; Shukla, P.; Lin, Z.C.; Churko, J.M.; Ebert, A.D.; Lan, F.; Diecke, S.; Huber, B.; Mordwinkin, N.M.; et al. Chemically defined generation of human cardiomyocytes. Nat. Methods 2014, 11, 855–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feyen, D.A.M.; McKeithan, W.L.; Bruyneel, A.A.N.; Spiering, S.; Hörmann, L.; Ulmer, B.; Zhang, H.; Briganti, F.; Schweizer, M.; Hegyi, B.; et al. Metabolic Maturation Media Improve Physiological Function of Human iPSC-Derived Cardiomyocytes. Cell Rep. 2020, 32, 107925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huby, A.C.; Mendsaikhan, U.; Takagi, K.; Martherus, R.; Wansapura, J.; Gong, N.; Osinska, H.; James, J.F.; Kramer, K.; Saito, K.; et al. Disturbance in Z-disk mechanosensitive proteins induced by a persistent mutant myopalladin causes familial restrictive cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 64, 2765–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refaat, M.M.; Hassanieh, S.; Ballout, J.A.; Zakka, P.; Hotait, M.; Khalil, A.; Bitar, F.; Arabi, M.; Arnaout, S.; Skouri, H.; et al. Non-familial cardiomyopathies in Lebanon: exome sequencing results for five idiopathic cases. BMC Med. Genomics 2019, 12, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Barajas-Martinez, H.; Zhu, D.; Wang, X.; Chen, C.; Zhuang, R.; Shi, J.; Wu, X.; Tao, Y.; Jin, W.; et al. Novel trigenic CACNA1C/DES/MYPN mutations in a family of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with early repolarization and short QT syndrome. J. Transl. Med. 2017, 15, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.; Ebana, Y.; Shim, J.; Choi, E.K.; Lim, H.E.; Hwang, I.; Yu, H.T.; Kim, T.H.; Uhm, J.S.; Joung, B.; et al. Ethnic similarities in genetic polymorphisms associated with atrial fibrillation: Far East Asian vs European populations. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 2021, 51, e13584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Nie, Y.; Wang, K.; Fan, C.; Zhao, J.; Yuan, Y. Identification of Atrial Fibrillation-Associated Genes ERBB2 and MYPN Using Genome-Wide Association and Transcriptome Expression Profile Data on Left-Right Atrial Appendages. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 696591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, K.; Wang, K. Interaction of nebulin SH3 domain with titin PEVK and myopalladin: implications for the signaling and assembly role of titin and nebulin. FEBS Lett. 2002, 532, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q.; Mendsaikhan, U.; Khuchua, Z.; Jones, B.C.; Lu, L.; Towbin, J.A.; Xu, B.; Purevjav, E. Dissection of Z-disc myopalladin gene network involved in the development of restrictive cardiomyopathy using system genetics approach. World J. Cardiol. 2017, 9, 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojic, S.; Medeot, E.; Guccione, E.; Krmac, H.; Zara, I.; Martinelli, V.; Valle, G.; Faulkner, G. The Ankrd2 protein, a link between the sarcomere and the nucleus in skeletal muscle. J. Mol. Biol. 2004, 339, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimenko, E.S.; Sukhareva, K.S.; Vlasova, Y.; Smolina, N.A.; Fomicheva, Y.; Knyazeva, A.; Muravyev, A.S.; Sorokina, M.Y.; Gavrilova, L.S.; Boldyreva, L.V.; et al. Flnc expression impacts mitochondrial function, autophagy, and calcium handling in C2C12 cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2024, 442, 114174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimenko, E.S.; Zaytseva, A.K.; Sorokina, M.Yu.; Perepelina, K.I.; Rodina, N.L.; Nikitina, E.G.; Sukhareva, K.S.; Khudiakov, A.A.; Vershinina, T.L.; Muravyev, A.S.; et al. Distinct molecular features of FLNC mutations, associated with different clinical phenotypes. Cytoskeleton 2025, 82, 158–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sievers, F.; Wilm, A.; Dineen, D.; Gibson, T.J.; Karplus, K.; Li, W.; Lopez, R.; McWilliam, H.; Remmert, M.; Söding, J.; et al. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2011, 7, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waterhouse, A.M.; Procter, J.B.; Martin, D.M.A.; Clamp, M.; Barton, G.J. Jalview Version 2—a multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1189–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berman, H.M.; Westbrook, J.; Feng, Z.; Gilliland, G.; Bhat, T.N.; Weissig, H.; Shindyalov, I.N.; Bourne, P.E. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.F.; Chen, Z.; Wang, C.; Yan, R.X.; Zhang, Z.; Song, J. Predicting residue-residue contacts and helix-helix interactions in transmembrane proteins using an integrative feature-based random forest approach. PLoS One 2011, 6, e26767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Li, C.; Mou, C.; Dong, Y.; Tu, Y. dbNSFP v4: a comprehensive database of transcript-specific functional predictions and annotations for human nonsynonymous and splice-site SNVs. Genome Med. 2020, 12, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorogina, D.A.; Grigor’eva, E.V.; Malakhova, A.A.; Pavlova, S.V.; Medvedev, S.P.; Vyatkin, Y.V.; Khabarova, E.A.; Rzaev, J.A.; Zakian, S.M. Creation of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells ICGi044-B and ICGi044-C Using Reprogramming of Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells of a Patient with Parkinson’s Disease Associated with с.1492T>G Mutation in the GLUD2 Gene. Russ. J. Dev. Biol. 2023, 54, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khudiakov, A.; Zaytseva, A.; Perepelina, K.; Smolina, N.; Pervunina, T.; Vasichkina, E.; Karpushev, A.; Tomilin, A.; Malashicheva, A.; Kostareva, A. Sodium current abnormalities and deregulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes generated from patient with arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy harboring compound genetic variants in plakophilin 2 gene. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2020, 1866, 165915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Donor-CMs | n | MYPN-N989I-CMs | n | p | ||

| Current density at -20mV | pA/pF | -292.1 ± 47.9 | 11 | -294.5 ± 27.0 | 20 | 0.9506 |

| Steady-state activation | V1/2, mV | -37.1 ± 1.1 | 11 | -33.1 ± 0.9 | 20 | 0.0121 |

| k | 5.7 ± 0.3 | 4.6 ± 0.2 | 0.0194 | |||

| Steady-state inactivation | V1/2, mV | -79.2 ± 2.0 | 10 | -77.1 ± 0.7 | 20 | 0.3012 |

| k | 7.7 ± 0.5 | 6.5 ± 0.2 | 0.0114 |

|

Donor-CMs, n=12 |

MYPN-N989I-CMs, n=9 | p | |

| APA, mV | 130,2 ± 5,876 | 125,0 ± 3,314 | 0,6187 |

| APD90, ms | 572,6 ± 52,65 | 546,8 ± 54,58 | 0,859 |

| APD70, ms | 472,0 ± 47,57 | 459,5 ± 46,29 | 0,9717 |

| APD30, ms | 338,8 ± 37,13 | 318,8 ± 42,18 | 0,594 |

| Signalingpathway | Gene symbol | Gene name | LFC | p.adj |

| Muscle system process | ACTN3 | actinin alpha 3 | 2.24 | 3.91*10-2 |

| ATP8A2 | ATPase phospholipid transporting 8A2 | 1.83 | 6.62*10-4 | |

| CASQ1 | calsequestrin 1 | 3.06 | 0 | |

| CHRNA3 | cholinergic receptor nicotinic alpha 3 subunit | 1.66 | 4.57*10-22 | |

| EDNRB | endothelin receptor type B | 4.29 | 0.01 | |

| GATA5 | GATA binding protein 5 | 1.55 | 1.62*10-8 | |

| IGF1 | insulin like growth factor 1 | 1.92 | 6.24*10-3 | |

| KBTBD13 | kelch repeat and BTB domain containing 13 | 2.38 | 7.47*10-5 | |

| KCNJ8 | potassium inwardly rectifying channel subfamily J member 8 | 1.57 | 6.09*10-27 | |

| MYLK | myosin light chain kinase | 1.90 | 1.66*10-67 | |

| MYOM2 | myomesin 2 | 2.70 | 3.46*10-82 | |

| OXTR | oxytocin receptor | 2.19 | 2.75*10-5 | |

| P2RX1 | purinergic receptor P2X 1 | 1.55 | 9.67*10-81 | |

| PIK3CG | phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit gamma | 6.38 | 1.84*10-4 | |

| SMTN | smoothelin | 1.55 | 3.28*10-40 | |

| STRIT1 | small transmembrane regulator of ion transport 1 | 6.16 | 4.03*10-3 | |

| TNFRSF1B | TNF receptor superfamily member 1B | 1.99 | 3.96*10-3 | |

| TNNI3K | TNNI3 interacting kinase | 1.83 | 1.03*10-6 | |

| TNNT3 | troponin T3, fast skeletal type | 3.13 | 9.81*10-8 | |

| TRIM72 | tripartite motif containing 72 | 1.65 | 0.02 | |

| Microtubule associated complex | CDCA8 | cell division cycle associated 8 | 1.51 | 2.35*10-6 |

| CENPE | centromere protein E | 1.52 | 1.21*10-6 | |

| DNAH11 | dynein axonemal heavy chain 11 | 5.04 | 2.64*10-25 | |

| ESPL1 | extra spindle pole bodies like 1, separase | 1.68 | 3.59*10-5 | |

| KIF15 | kinesin family member 15 | 1.64 | 4.95*10-3 | |

| KIF18A | kinesin family member 18A | 2.00 | 3.19*10-7 | |

| KIF20A | kinesin family member 20A | 1.67 | 1.61*10-15 | |

| KIF2C | kinesin family member 2C | 1.71 | 2.67*10-9 | |

| KIF4A | kinesin family member 4A | 1.86 | 8.12*10-13 | |

| KIFC1 | kinesin family member C1 | 1.80 | 4.95*10-10 | |

| MAP7 | microtubule associated protein 7 | 1.59 | 2.68*10-3 | |

| NDC80 | NDC80 kinetochore complex component | 2.32 | 1.50*10-11 | |

| NUF2 | NUF2 component of NDC80 kinetochore complex | 2.27 | 1.49*10-9 | |

| PRC1 | protein regulator of cytokinesis 1 | 2.18 | 1.43*10-2 | |

| SAPCD2 | suppressor APC domain containing 2 | 1.56 | 0.02 | |

| SPC24 | kinetochore-associated Ndc80 complex subunit SPC24 | 1.59 | 1.06*10-5 | |

| Sarcomere, Z-disc and I-band organization | ACTN4 | actinin alpha 4 | -1.79 | 4.7*10-148 |

| BMP10 | bone morphogenetic protein 10 | -5.37 | 4.91*10-2 | |

| CSRP1 | cysteine and glycine rich protein 1 | -3.40 | 1.86*10-234 | |

| DES | desmin | -1.51 | 4.73*10-289 | |

| MYH6 | myosin heavy chain 6 | -1.95 | 0 | |

| MYOZ1 | myozenin 1 | -1.68 | 1.11*10-24 | |

| Cell junction associated genes | ACTB | actin beta | -1.81 | 0 |

| CBLN1 | cerebellin 1 precursor | -1.70 | 1.83*10-3 | |

| CDH12 | cadherin 12 | -3.26 | 5.18*10-3 | |

| CLDN9 | claudin 9 | -1.66 | 0.04 | |

| EPHB3 | EPH receptor B3 | -1.56 | 1.75*10-81 | |

| GABRG2 | gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor subunit gamma2 | -7.74 | 1.81*10-5 | |

| NRXN1 | neurexin 1 | -1.71 | 5.66*10-7 | |

| NTN1 | netrin 1 | -1.97 | 3.61*10-63 | |

| PKP1 | plakophilin 1 | -7.47 | 5.99*10-5 | |

| SEMA4A | semaphorin 4A | -2.48 | 3.31*10-12 | |

| SLITRK2 | SLIT and NTRK like family member 2 | -5.83 | 0.02 | |

| SLITRK4 | SLIT and NTRK like family member 4 | -1.58 | 0.01 | |

| UGT8 | UDP glycosyltransferase 8 | -1.81 | 0.04 | |

| Actin cytoskeleton | ACTB | actin beta | -1.81 | 0 |

| ACTN4 | actinin alpha 4 | -1.79 | 4.67*10-148 | |

| APC2 | APC regulator of Wnt signaling pathway 2 | -3.62 | 4.09*10-5 | |

| ARC | activity regulated cytoskeleton associated protein | -3.93 | 1.94*10-4 | |

| FHDC1 | FH2 domain containing 1 | -2.85 | 0.03 | |

| LAD1 | ladinin 1 | -2.58 | 6.27*10-75 | |

| MISP | mitotic spindle positioning | -5.56 | 0.03 | |

| MYH6 | myosin heavy chain 6 | -1.95 | 0 | |

| MYO1D | myosin ID | -2.04 | 7,09*10-91 | |

| MYOZ1 | myozenin 1 | -1.68 | 1.11*10-24 | |

| NTN1 | netrin 1 | -1.97 | 3.61*10-63 | |

| RINL | Ras and Rab interactor like | -1.84 | 0.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).