Submitted:

18 December 2025

Posted:

22 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

1.1. Data Collection and Preprocessing

1.2. Development and Evaluation of Classification Models

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUC-ROC | Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve |

| CDC | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| FPR | False Positive Rate |

| IL | interleukin |

| ML | machine learning |

| NT-proBNP | N terminal pro B type natriuretic peptide |

| OvR | One-vs-Rest |

| PCT | procalcitonin |

| ROC | receiver operating characteristic |

| SNP | single-nucleotide polymorphisms |

| TPR | True Positive Rate |

| WBC | white blood cells |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Brodin, P. Immune determinants of COVID-19 disease presentation and severity. Nat Med. 2021, 27(1), 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoeni, R.F.; Wiemers, E.E.; Seltzer, J.A.; Langa, K.M. Association between risk factors for complications from COVID-19, perceived chances of infection and complications, and protective behavior in the US. JAMA network open. 2021, 4(3), e213984–e213984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokolenko, M.O.; Sydorchuk, L.P.; Sokolenko, L.S.; Sokolenko, A.A. General immunologic reactivity of patients with COVID-19 and its relation to gene polymorphism, severity of clinical course of the disease and combination with comorbidities. Med. Perspekt. 2024, 29, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.J.; Dong, X.; Liu, G.H.; Gao, Y.D. Risk and protective factors for COVID-19 morbidity, severity, and mortality. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2023, 64, 90–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.H.; Choi, S.H.; Yun, K.W. Risk factors for severe COVID-19 in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Korean medical science. 2022, 37(5), e35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolenko, M.; Sydorchuk, L.; Sokolenko, A.; Sydorchuk, R.; Kamyshna, I.; Sydorchuk, A.; Sokolenko, L.; Sokolenko, O.; Oksenych, V.; Kamyshnyi, O. Antiviral Intervention of COVID-19: Linkage of Disease Severity with Genetic Markers FGB (rs1800790), NOS3 (rs2070744) and TMPRSS2 (rs12329760). Viruses 2025, 17, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, D.; Nee, S.; Hickey, N.S.; Marschollek, M. Risk factors for COVID-19 severity and fatality: a structured literature review. Infection 2021, 49, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herold, T.; Jurinovic, V.; Arnreich, C.; et al. Elevated IL-6 and CRP predict the need for mechanical ventilation in COVID-19. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2020, 146(1), 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippi, G.; Plebani, M. Procalcitonin in patients with severe coronavirus disease 2019: a meta-analysis. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2020, 505, 190–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Hu, B.; Hu, C.; et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA 2020, 323(11), 1061–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, N.; Li, D.; Wang, X.; Sun, Z. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with COVID-19. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2020, 18(4), 844–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosello, S.; De Luca, G.; Berardi, G.; Canestrari, G.; De Waure, C.; Gabrielli, F.A.; et al. Cardiac troponin T and NT-proBNP as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers of primary cardiac involvement and disease severity in systemic sclerosis: a prospective study. European Journal of Internal Medicine 2019, 60, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, L.; Jiang, D.; Wen, X.; et al. Prognostic value of NT-proBNP in patients with severe COVID-19. Respiratory Research 2020, 21(1), 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buttìa, C.; Llanaj, E.; Raeisi-Dehkordi, H.; et al. Prognostic models in COVID-19 infection that predict severity: a systematic review. European Journal of Epidemiology 2023, 38(4), 355–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Zhong, W.; Liu, T.; et al. Early prediction model for critical illness of hospitalized COVID-19 patients based on machine learning techniques. Frontiers in Public Health. 2022, 10, 880999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eze, C.E.; Igwama, G.T.; Nwankwo, E.I.; Victor, E. AI-driven health data analytics for early detection of infectious diseases: a conceptual exploration of US public health strategies. Comprehensive Research Reviews in Science and Technology 2024, 2(2), 74–82. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, I.; Behl, T.; Aleya, L.; et al. Artificial intelligence as a fundamental tool in management of infectious diseases and its current implementation in COVID-19 pandemic. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2021, 28(30), 40515–40532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shouval, R.; Bondi, O.; Mishan, H.; Shimoni, A.; Unger, R.; Nagler, A. Application of machine learning algorithms for clinical predictive modeling: a data-mining approach in SCT. Bone marrow transplantation 2014, 49(3), 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, A.M.; Yousefpoor, E.; Yousefpoor, M.S.; et al. Machine learning (ML) in medicine: review, applications, and challenges. Mathematics. 2021, 9(22), 2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Krentz, A.J.; Huo, Z.; Ćurčin, V. Opportunities and challenges of cardiovascular disease risk prediction for primary prevention using machine learning and electronic health records: a systematic review. Reviews in Cardiovascular Medicine 2025, 26(4), 37443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhou, X.; Ding, S.; et al. Identification of transcriptome biomarkers for severe COVID-19 with machine learning methods. Biomolecules. 2022, 12(12), 1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wetere Tulu, T.; Wan, T.K.; Chan, C.L.; Wu, C.H.; Woo, P.Y.M.; Tseng, C.Z.S.; et al. Machine learning-based prediction of COVID-19 mortality using immunological and metabolic biomarkers. BMC Digital Health 2023, 1, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, S.; Kumar, S.; Mandal, A.; Saini, V.; Bansal, A.; Jain, A.; et al. A machine learning model for the prediction of COVID-19 severity using RNA-seq, clinical, and co-morbidity data. Diagnostics 2024, 14(12), 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wynants, L.; Van Calster, B.; Collins, G.S.; Riley, R.D.; Heinze, G.; Schuit, E.; et al. Prediction models for diagnosis and prognosis of COVID-19: systematic review and critical appraisal. BMJ 2020, 369, m1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, P.; DuMont Schütte, A.; Dietz, B.; Bauer, S. Clinical predictive models for COVID-19: systematic study. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2020, 22(10), e21439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sydorchuk, L.; Sokolenko, M.; Škoda, M.; Lajcin, D.; Vyklyuk, Y.; Sydorchuk, R.; Sokolenko, A.; Martjanov, D. Management of severe COVID-19 diagnosis using machine learning. Computation. 2025, 13, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protocol “Provision of medical assistance for the treatment of coronavirus disease (COVID-19)”. Approved by the Order of the Ministry of Health of Ukraine of 2 April 2020 No. 762 (As Amended by the Order of the Ministry of Health of Ukraine of 17 May 2023 No. 913. (In Ukrainian). Available online: https://www.dec.gov.ua/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/protokol-covid2023.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- National Medical Care Standard “Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)”. Approved by Order No. 722 of the Ministry of Health of Ukraine Dated 28 March 2020. In Ukrainian). Available online: https://www.dec.gov.ua/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/2020_722_standart_covid_19.pdf. Available online: https://www.dec.gov.ua/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/2020_722_standart_covid_19.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- CDC 24/7: Saving Lives, Protecting People. Prevention Actions to Use at All COVID-19 Community Levels. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. 2023. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/covid/prevention/index.html (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Chen, Y.; Ouyang, L.; Bao, F.S.; Li, Q.; Han, L.; Zhang, H.; et al. A multimodality machine learning approach to differentiate severe and nonsevere COVID-19: model development and validation. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2021, 23(4), e23948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktar, S.; Ahamad, M.M.; Rashed-Al-Mahfuz, M.; Azad, A.K.M.; Uddin, S.; Kamal, A.H.M.; et al. Machine learning approach to predicting COVID-19 disease severity based on clinical blood test data: model development. JMIR Medical Informatics 2021, 9(4), e25884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaf, D.; Gutman, Y.A.; Neuman, Y.; Segal, G.; Amit, S.; Gefen-Halevi, S.; et al. Utilization of machine-learning models to accurately predict the risk for critical COVID-19. Internal and Emergency Medicine 2020, 15, 1435–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrington, A.M.; Manuel, D.G.; Fieguth, P.W.; Ramsay, T.; Osmani, V.; Wernly, B.; et al. Deep ROC analysis and AUC as balanced average accuracy, for improved classifier selection, audit and explanation. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence. 2023, 45(1), 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Xu, Q.; Bao, S.; Cao, X.; Huang, Q. Learning with multiclass AUC: theory and algorithms. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence. 2021, 44(11), 7747–7763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yates, L.A.; Aandahl, Z.; Richards, S.A.; Brook, B.W. Cross validation for model selection: a review with examples from ecology. Ecological Monographs. 2023, 93(1), e1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, P.; Uddin, S.; Hajati, F.; Moni, M.A. Ensemble learning for disease prediction: a review. Healthcare 2023, 11(12), 1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Aslam, N.; Ahmad, H.; Mazhar, F.; Bhatti, Y.I.; Abid, U. Predictive modeling of chronic kidney disease using extra tree classifier: a comparative analysis with traditional methods. Journal of Computational and Biomedical Informatics 2024, 6(2), 261–271. [Google Scholar]

- Ushasree, D.; Krishna, A.P.; Rao, C.M. Enhanced stroke prediction using stacking methodology (ESPESM) in intelligent sensors for aiding preemptive clinical diagnosis of brain stroke. Measurement: Sensors 2024, 33, 101108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Duhayyim, M.; Abbas, S.; Al Hejaili, A.; Kryvinska, N.; Almadhor, A.; Mohammad, U.G. An ensemble machine learning technique for stroke prognosis. Computer Systems Science and Engineering 2023, 47(1), 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ontshick, L.L.; Sabue, J.C.M.; Kiangebeni, P.M.; et al. Comparison of the performance of linear discriminant analysis and binary logistic regression applied to risk factors for mortality in Ebola virus disease patients. Journal of Electronic, Electromedical Engineering and Medical Informatics 2023, 5(3), 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vabalas, A.; Gowen, E.; Poliakoff, E.; Casson, A.J. Machine learning algorithm validation with a limited sample size. PLoS One 2019, 14(11), e0224365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rane, N.; Choudhary, S.P.; Rane, J. Ensemble deep learning and machine learning: applications, opportunities, challenges, and future directions. Studies in Medical and Health Sciences 2024, 1(2), 18–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

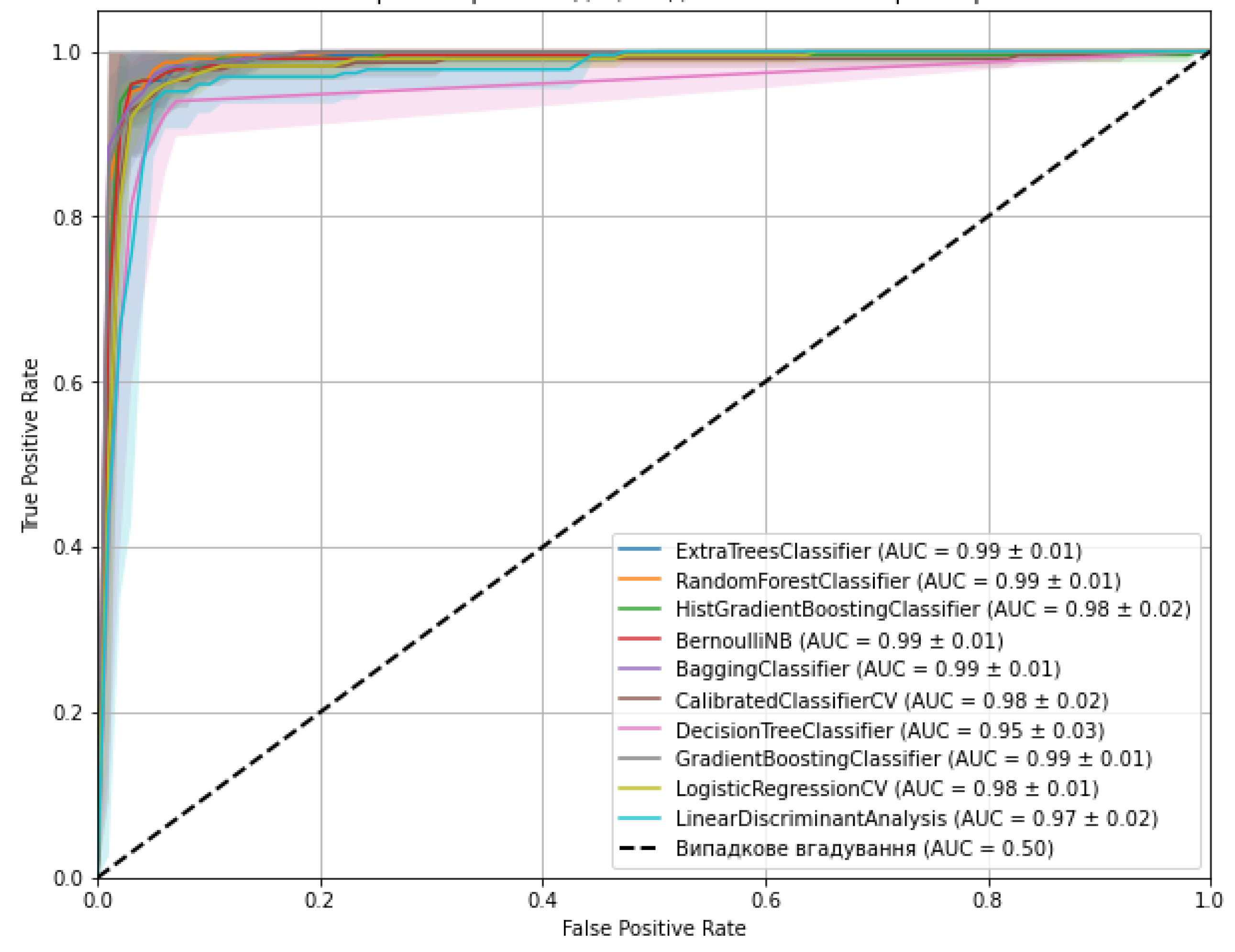

| Models | Optimal hyperparameters | Accuracy (mean ± SD) | AUC-ROC |

| ExtraTreesClassifier | max_depth: 10, min_samples_split: 5, n_estimators: 200 | 0.974 (± 0.022) | 1.000 |

| RandomForestClassifier | max_depth: 20, min_samples_leaf: 2, min_samples_split: 2, n_estimators: 50 | 0.965 (± 0.033) | 0.9998 |

| HistGradientBoostingClassifier | learning_rate: 0.2, max_depth: None, max_iter: 100 | 0.960 (± 0.029) | 1.000 |

| BernoulliNB | alpha: 0.01, fit_prior: True | 0.960 (± 0.038) | 0.9879 |

| BaggingClassifier | max_features: 1.0, max_samples: 1.0, n_estimators: 50 | 0.969 (± 0.033) | 1.000 |

| CalibratedClassifierCV | cv: 5, method: 'sigmoid' | 0.943 (± 0.030) | 0.9819 |

| DecisionTreeClassifier | max_depth: 20, min_samples_leaf: 2, min_samples_split: 2 | 0.960 (± 0.022) | 0.9998 |

| GradientBoostingClassifier | learning_rate: 0.1, max_depth: 3, n_estimators: 200 | 0.938 (± 0.043) | 1.000 |

| LogisticRegressionCV | Cs: 100, max_iter: 1000, penalty: 'l1', solver: 'liblinear' | 0.960 (± 0.026) | 0.9755 |

| LinearDiscriminantAnalysis | shrinkage: 'auto', solver: 'lsqr' | 0.947 (± 0.041) | 0.9778 |

| Models | Total number of errors | Class 0 errors | Class 1 errors | Class 2 errors |

| ExtraTreesClassifier | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| RandomForestClassifier | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| HistGradientBoostingClassifier | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| BernoulliNB | 6 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| BaggingClassifier | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CalibratedClassifierCV | 9 | 0 | 7 | 2 |

| DecisionTreeClassifier | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| GradientBoostingClassifier | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| LogisticRegressionCV | 9 | 0 | 7 | 2 |

| LinearDiscriminantAnalysis | 11 | 0 | 7 | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).