Submitted:

18 December 2025

Posted:

19 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

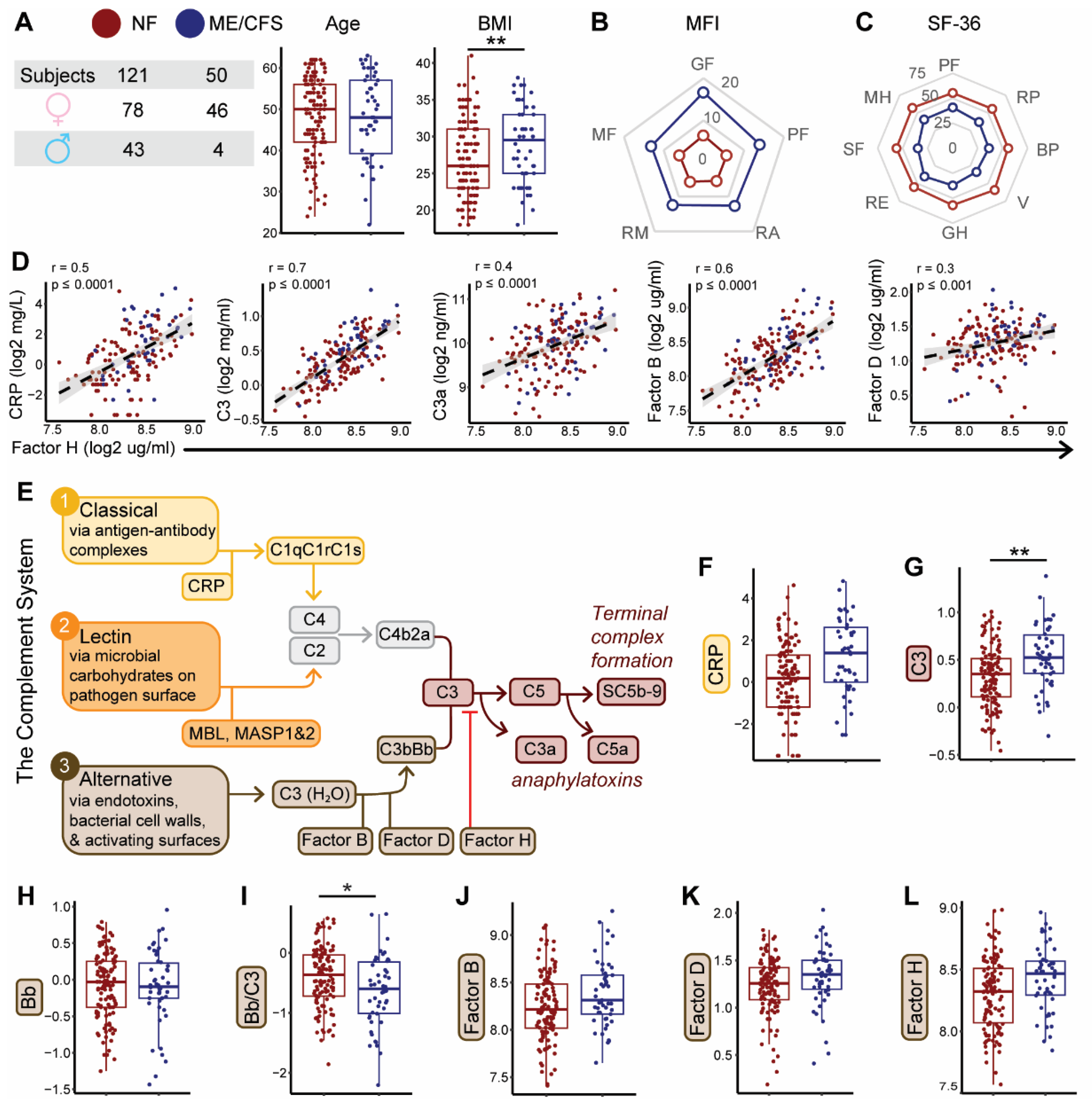

2.1. Complement System Dynamics and Associations with Demographics and Disease Status

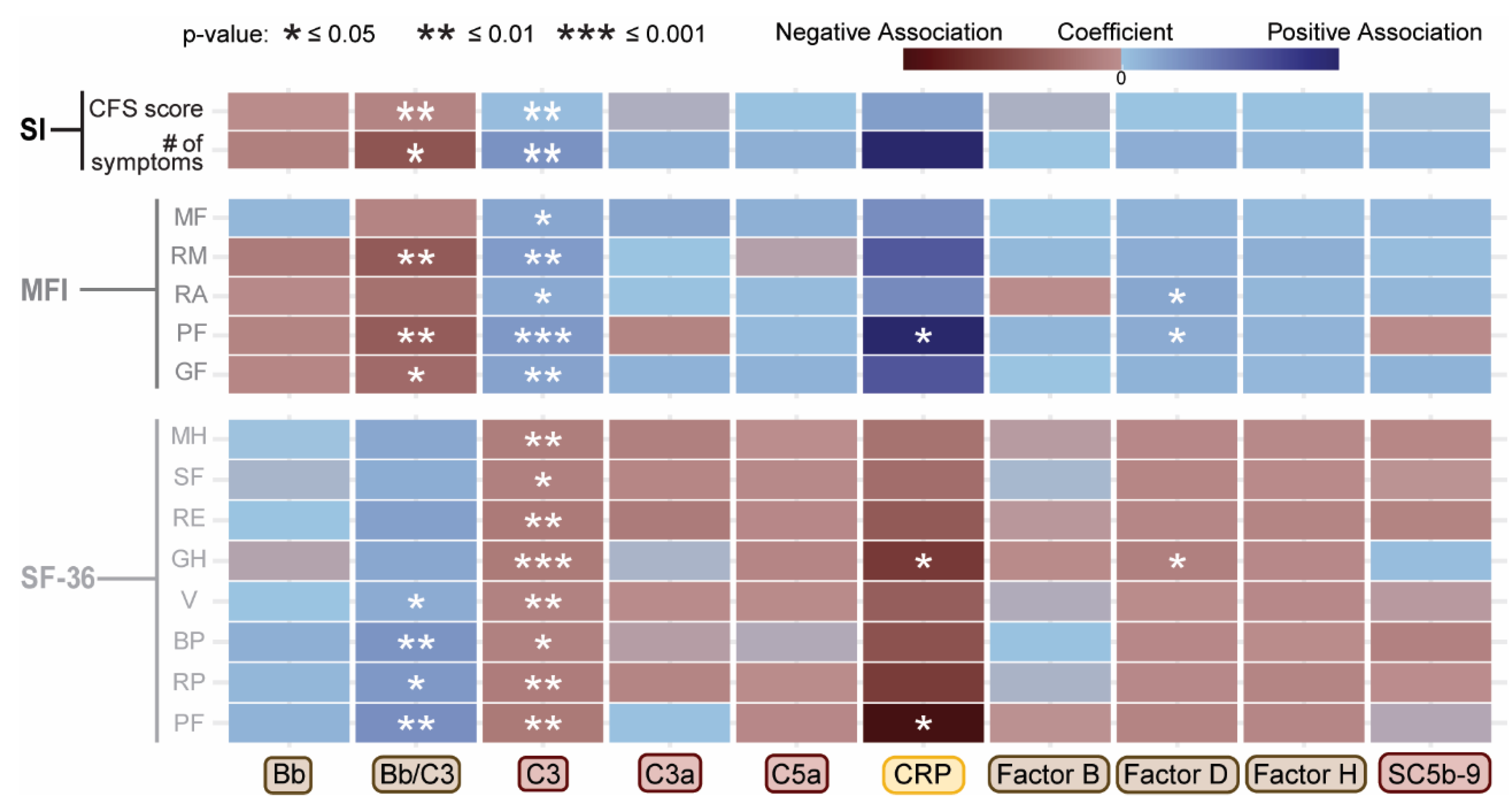

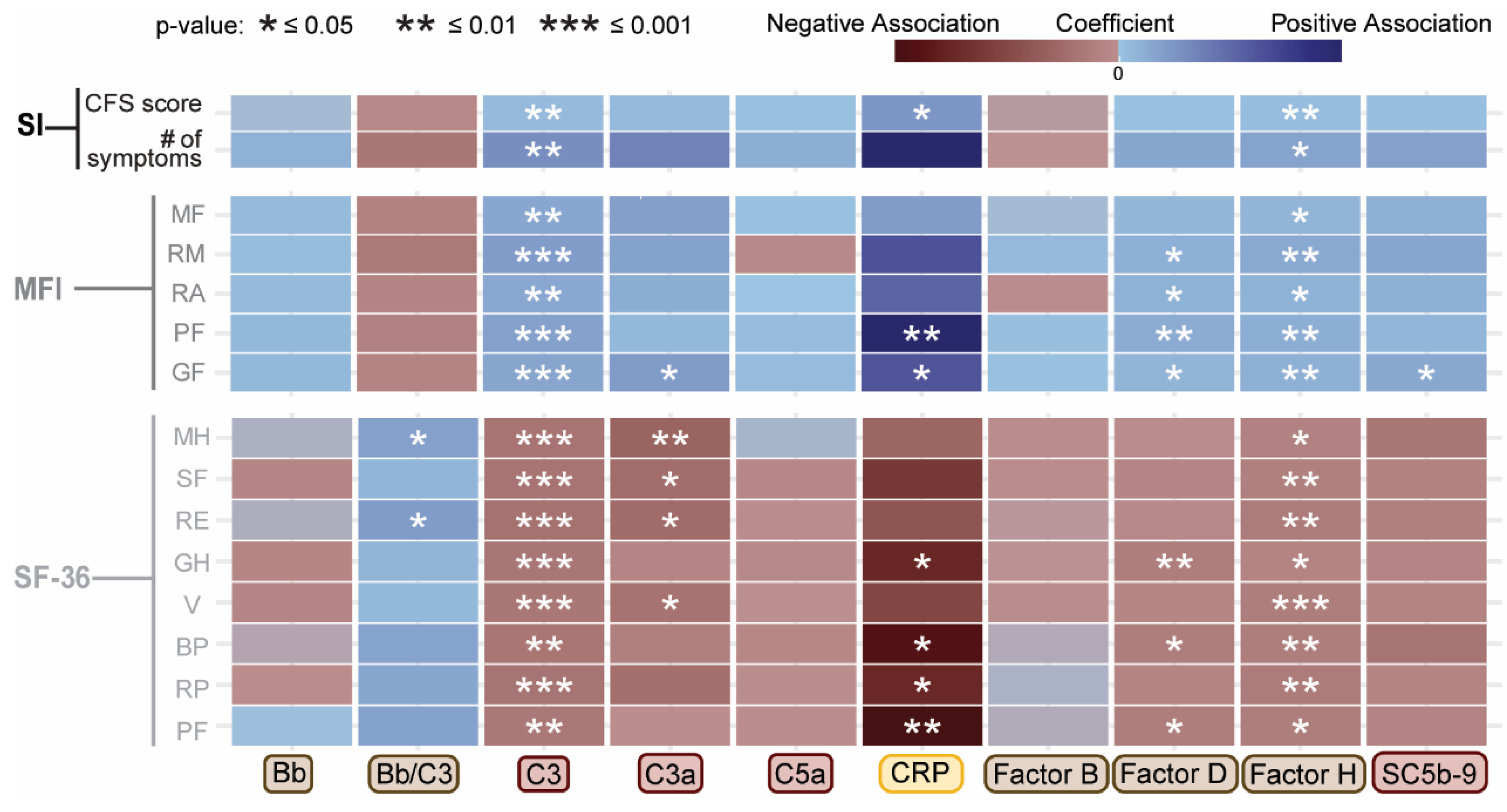

2.2. Associations Between Complement System Components and Functional Health Scores

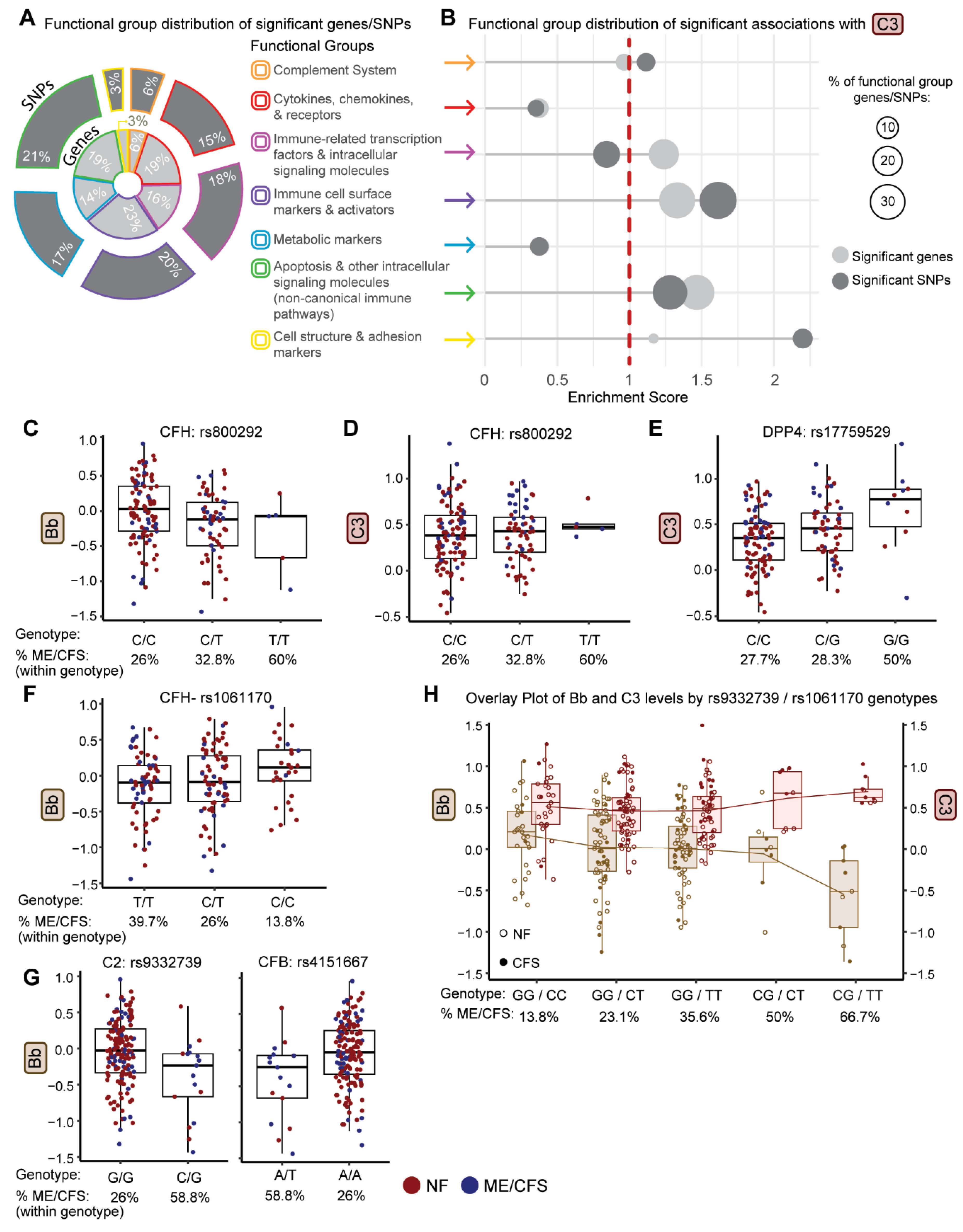

2.3. Identification of Genetic Variants Impacting Plasma Levels of Complement Proteins

2.4. Identification of Genetic Variants Impacting Both Plasma Levels of Complement Proteins and Disease Status

2.5. Use Of Genotype-Defined Complement pQTLs to Identify ME/CFS Subgroups

2.6. Comparison of Significant SNPs Between Our Population and Fatigue-Related Phenotypes in the UK Biobank

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Subject Recruitment and Characteristics

4.2. Plasma Protein and Complement Component Assays

4.3. Statistical Analyses

4.3.1. Data Transformation

4.3.2. Data analyses and visualizations for group phenotypes and complement protein levels

4.3.3. Identification of Confounding Factors

4.3.4. Analysis of Circulating Complement Proteins Between ME/CFS and NF Subjects

4.3.5. Analysis of Participant Survey Data with Circulating Complement Proteins

4.3.6. Analysis of SNP Associations with Circulating Complement Proteins

4.3.7. Pathway Enrichment Analysis to Annotate SNP Associations with Circulating Complement Protein Levels

4.3.8. Analysis of SNP Associations with Circulating Complement Protein Levels and Disease Status

4.3.9. Analysis of the Directionality of Genetic Variant Traits with Disease Risk

4.3.10. Genotype-Stratified Analysis to Identify ME/CFS Subgroup Related to Complement System Dysregulation

4.3.11. Comparison of Significant SNPs Between Our Population and the UK Biobank

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Medicine, I.o. Beyond Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Redefining an Illness; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, 2015; p. 304. [Google Scholar]

- Unger, E.R.; Lin, J.-M.S.; Chen, Y.; Cornelius, M.E.; Helton, B.; Issa, A.N.; Bertolli, J.; Klimas, N.G.; Balbin, E.G.; Bateman, L.; et al. Heterogeneity in Measures of Illness among Patients with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Is Not Explained by Clinical Practice: A Study in Seven U.S. Specialty Clinics. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajeevan, M.S.; Dimulescu, I.; Murray, J.; Falkenberg, V.R.; Unger, E.R. Pathway-focused genetic evaluation of immune and inflammation related genes with chronic fatigue syndrome. Hum. Immunol. 2015, 76, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.K.; Fang, H.; Whistler, T.; Unger, E.R.; Rajeevan, M.S. Convergent Genomic Studies Identify Association of GRIK2 and NPAS2 with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Neuropsychobiology 2011, 64, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, M.; Jaundoo, R.; Hilton, K.; Del Alamo, A.; Gemayel, K.; Klimas, N.G.; Craddock, T.J.A.; Nathanson, L. Genetic Predisposition for Immune System, Hormone, and Metabolic Dysfunction in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A Pilot Study. Front. Pediatr. 2019, 7, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Schlauch, K.; Khaiboullina, S.F.; De Meirleir, K.L.; Rawat, S.; Petereit, J.; A Rizvanov, A.; Blatt, N.; Mijatovic, T.; Kulick, D.; Palotás, A.; et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies genetic variations in subjects with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Psychiatry 2016, 6, e730–e730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall-Gradisnik, S.; Huth, T.; Chacko, A.; Johnston, S.; Smith, P.; Staines, D. Natural killer cells and single nucleotide polymorphisms of specific ion channels and receptor genes in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Appl. Clin. Genet. 2016, 9, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall-Gradisnik, S.; Johnston, S.; Chacko, A.; Nguyen, T.; Smith, P.; Staines, D. Single nucleotide polymorphisms and genotypes of transient receptor potential ion channel and acetylcholine receptor genes from isolated B lymphocytes in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome patients. J. Int. Med Res. 2016, 44, 1381–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlo-Stella, N.; Badulli, C.; De Silvestri, A.; Bazzichi, L.; Martinetti, M.; Lorusso, L.; Bombardieri, S.; Salvaneschi, L.; Cuccia, M. A first study of cytokine genomic polymorphisms in CFS: Positive association of TNF-857 and IFNgamma 874 rare alleles. 2006, 24, 179–82. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner, S.; Becker, S.C.; Hartwig, J.; Sotzny, F.; Lorenz, S.; Bauer, S.; Löbel, M.; Stittrich, A.B.; Grabowski, P.; Scheibenbogen, C. Autoimmunity-Related Risk Variants in PTPN22 and CTLA4 Are Associated With ME/CFS With Infectious Onset. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lande, A.; Fluge, Ø.; Strand, E.B.; Flåm, S.T.; Sosa, D.D.; Mella, O.; Egeland, T.; Saugstad, O.D.; Lie, B.A.; Viken, M.K. Human Leukocyte Antigen alleles associated with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS). Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajeevan, M.S.; Smith, A.K.; Dimulescu, I.; Unger, E.R.; Vernon, S.D.; Heim, C.; Reeves, W.C. Glucocorticoid receptor polymorphisms and haplotypes associated with chronic fatigue syndrome. Genes, Brain Behav. 6, 167–176. [CrossRef]

- Tziastoudi, M.; Cholevas, C.; Stefanidis, I.; Theoharides, T.C. Genetics of COVID-19 and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: a systematic review. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2022, 9, 1838–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajdarevic, R.; Lande, A.; Mehlsen, J.; Rydland, A.; Sosa, D.D.; Strand, E.B.; Mella, O.; Pociot, F.; Fluge, Ø.; Lie, B.A.; et al. Genetic association study in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) identifies several potential risk loci. Brain, Behav. Immun. 2022, 102, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.; et al. Genome-wide mapping of plasma protein QTLs identifies putatively causal genes and pathways for cardiovascular disease. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.H.; Stacey, D.; Eriksson, N.; Macdonald-Dunlop, E.; Hedman, Å.K.; Kalnapenkis, A.; Enroth, S.; Cozzetto, D.; Digby-Bell, J.; Marten, J.; et al. Genetics of circulating inflammatory proteins identifies drivers of immune-mediated disease risk and therapeutic targets. Nat. Immunol. 2023, 24, 1540–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, B.; Shi, J.; Wang, X.; Jiang, H.; Zhu, H.-J. Genome-wide pQTL analysis of protein expression regulatory networks in the human liver. BMC Biol. 2020, 18, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricklin, D.; Hajishengallis, G.; Yang, K.; Lambris, J.D. Complement: A key system for immune surveillance and homeostasis. Nat. Immunol. 2010, 11, 785–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathern, D.R.; Heeger, P.S. Molecules Great and Small: The Complement System. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2015, 10, 1636–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, B.; Streib, J.E.; Strand, M.; Make, B.; Giclas, P.C.; Fleshner, M.; Jones, J.F. Complement activation in a model of chronic fatigue syndrome. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2003, 112, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, B.; Jones, J.F.; Vernon, S.D.; Rajeevan, M.S. Transcriptional Control of Complement Activation in an Exercise Model of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Mol. Med. 2009, 15, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giloteaux, L.; Glass, K.A.; Germain, A.; Franconi, C.J.; Zhang, S.; Hanson, M.R. Dysregulation of extracellular vesicle protein cargo in female myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome cases and sedentary controls in response to maximal exercise. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2024, 13, e12403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutzer, S.E.; et al. Distinct cerebrospinal fluid proteomes differentiate post-treatment lyme disease from chronic fatigue syndrome. PLoS One 2011, 6, e17287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Germain, A.; Levine, S.M.; Hanson, M.R. In-Depth Analysis of the Plasma Proteome in ME/CFS Exposes Disrupted Ephrin-Eph and Immune System Signaling. Proteomes 2021, 9, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenther, S.; Loebel, M.; Mooslechner, A.A.; Knops, M.; Hanitsch, L.G.; Grabowski, P.; Wittke, K.; Meisel, C.; Unterwalder, N.; Volk, H.-D.; et al. Frequent IgG subclass and mannose binding lectin deficiency in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Hum. Immunol. 2015, 76, 729–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, L.; Rohrhofer, J.; Zehetmayer, S.; Stingl, M.; Untersmayr, E. Evaluation of Immune Dysregulation in an Austrian Patient Cohort Suffering from Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Patel, M.; Chan, C.-C. Molecular pathology of age-related macular degeneration. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2009, 28, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Despriet, D.D.G.; Klaver, C.C.W.; Witteman, J.C.M.; Bergen, A.A.B.; Kardys, I.; de Maat, M.P.M.; Boekhoorn, S.S.; Vingerling, J.R.; Hofman, A.; Oostra, B.A.; et al. Complement Factor H Polymorphism, Complement Activators, and Risk of Age-Related Macular Degeneration. JAMA 2006, 296, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gold, B.; E Merriam, J.; Zernant, J.; Hancox, L.S.; Taiber, A.J.; Gehrs, K.; Cramer, K.; Neel, J.; Bergeron, J.; et al.; The AMD Genetics Clinical Study Group Variation in factor B (BF) and complement component 2 (C2) genes is associated with age-related macular degeneration. Nat. Genet. 2006, 38, 458–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholl, H.P.N.; Issa, P.C.; Walier, M.; Janzer, S.; Pollok-Kopp, B.; Börncke, F.; Fritsche, L.G.; Chong, N.V.; Fimmers, R.; Wienker, T.; et al. Systemic Complement Activation in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. PLOS ONE 2008, 3, e2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecker, L.A.; Edwards, A.O.; Ryu, E.; Tosakulwong, N.; Baratz, K.H.; Brown, W.L.; Issa, P.C.; Scholl, H.P.; Pollok-Kopp, B.; Schmid-Kubista, K.E.; et al. Genetic control of the alternative pathway of complement in humans and age-related macular degeneration. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009, 19, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smailhodzic, D.; Klaver, C.C.; Klevering, B.J.; Boon, C.J.; Groenewoud, J.M.; Kirchhof, B.; Daha, M.R.; Hollander, A.I.D.; Hoyng, C.B. Risk Alleles in CFH and ARMS2 Are Independently Associated with Systemic Complement Activation in Age-related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmology 2012, 119, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastián-Martín, A.; Sánchez, B.G.; Mora-Rodríguez, J.M.; Bort, A.; Díaz-Laviada, I. Role of Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 (DPP4) on COVID-19 Physiopathology. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoke, M.; Speidl, W.; Schillinger, M.; Minar, E.; Zehetmayer, S.; Schönherr, M.; Wagner, O.; Mannhalter, C. Polymorphism of the complement 5 gene and cardiovascular outcome in patients with atherosclerosis. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 42, 921–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, J.L.; Choy, E.; Berg, C.v.D.; Morgan, B.P.; Harris, C.L. Functional Analysis of a Complement Polymorphism (rs17611) Associated with Rheumatoid Arthritis. J. Immunol. 2015, 194, 3029–3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acar, I.E.; Willems, E.; Kersten, E.; Keizer-Garritsen, J.; Kragt, E.; Bakker, B.; Galesloot, T.E.; Hoyng, C.B.; Fauser, S.; van Gool, A.J.; et al. Semi-Quantitative Multiplex Profiling of the Complement System Identifies Associations of Complement Proteins with Genetic Variants and Metabolites in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copenhaver, M.M.; Yu, C.-Y.; Zhou, D.; Hoffman, R.P. Relationships of complement components C3 and C4 and their genetics to cardiometabolic risk in healthy, non-Hispanic white adolescents. Pediatr. Res. 2020, 87, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaya da Costa, M.; et al. Age and Sex-Associated Changes of Complement Activity and Complement Levels in a Healthy Caucasian Population. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaFon, D.C.; Thiel, S.; Kim, Y.-I.; Dransfield, M.T.; Nahm, M.H. Classical and lectin complement pathways and markers of inflammation for investigation of susceptibility to infections among healthy older adults. Immun. Ageing 2020, 17, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelkar, N.S.; Goldberg, B.S.; Dufloo, J.; Bruel, T.; Schwartz, O.; Hessell, A.J.; Ackerman, M.E. Sex- and species-associated differences in complement-mediated immunity in humans and rhesus macaques. mBio 2024, 15, e0028224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, A.E.; Moin, A.S.M.; Sathyapalan, T.; Atkin, S.L. Complement Dysregulation in Obese Versus Nonobese Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Patients. Cells 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Q.; Bouwman, F.G.; van Baak, M.A.; Renes, J.; Mariman, E.C. Glucose Restriction Plus Refeeding in Vitro Induce Changes of the Human Adipocyte Secretome with an Impact on Complement Factors and Cathepsins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fruh, S.M. Obesity: Risk factors, complications, and strategies for sustainable long-term weight management. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract 2017, 29, S3–S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Navarrete, J.M.; Fernández-Real, J.M. The complement system is dysfunctional in metabolic disease: Evidences in plasma and adipose tissue from obese and insulin resistant subjects. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 85, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawle, A.C.; Nisenbaum, R.; Dobbins, J.G.; Gary, H.E.; Stewart, J.A.; Reyes, M.; Steele, L.; Schmid, D.S.; Reeves, W.C. Immune Responses Associated with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A Case-Control Study. J. Infect. Dis. 1997, 175, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez, A.R.; Hancock, E.E.; Adebayo, S.; Kiernicki, D.J.; Proskauer, D.; Attewell, J.R.; Bateman, L.; DeMaria, A., Jr.; Lapp, C.W.; Rowe, P.C.; et al. Estimating Prevalence, Demographics, and Costs of ME/CFS Using Large Scale Medical Claims Data and Machine Learning. Front. Pediatr. 2018, 6, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivieri, F.; Marchegiani, F.; Matacchione, G.; Giuliani, A.; Ramini, D.; Fazioli, F.; Sabbatinelli, J.; Bonafè, M. Sex/gender-related differences in inflammaging. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2023, 211, 111792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamitaki, N.; Sekar, A.; Handsaker, R.E.; de Rivera, H.; Tooley, K.; Morris, D.L.; Taylor, K.E.; Whelan, C.W.; Tombleson, P.; et al.; Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium Complement genes contribute sex-biased vulnerability in diverse disorders. Nature 2020, 582, 577–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodhi, E.U.; Philpott, H.T.; Carter, M.M.; Birmingham, T.B.; Appleton, C.T. Sex-Differences and Associations Between Complement Activation and Synovial Vascularization in Patients with Late-Stage Knee Osteoarthritis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 890094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohrhofer, J.; Hauser, L.; Lettenmaier, L.; Lutz, L.; Koidl, L.; Gentile, S.A.; Ret, D.; Stingl, M.; Untersmayr, E. Immunological Patient Stratification in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Marrero, J.; Zacares, M.; Almenar-Pérez, E.; Alegre-Martín, J.; Oltra, E. Complement Component C1q as a Potential Diagnostic Tool for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Subtyping. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchwald, D.; Wener, M.H.; Pearlman, T.; Kith, P. Markers of inflammation and immune activation in chronic fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome. 1997, 24, 372–6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nacul, L.; de Barros, B.; Kingdon, C.C.; Cliff, J.M.; Clark, T.G.; Mudie, K.; Dockrell, H.M.; Lacerda, E.M. Evidence of Clinical Pathology Abnormalities in People with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) from an Analytic Cross-Sectional Study. Diagnostics 2019, 9, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunes, M.; Vlok, M.; Proal, A.; Kell, D.B.; Pretorius, E. Data-independent LC-MS/MS analysis of ME/CFS plasma reveals a dysregulated coagulation system, endothelial dysfunction, downregulation of complement machinery. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2024, 23, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paun, C.C.; Lechanteur, Y.T.E.; Groenewoud, J.M.M.; Altay, L.; Schick, T.; Daha, M.R.; Fauser, S.; Hoyng, C.B.; Hollander, A.I.D.; de Jong, E.K. A Novel Complotype Combination Associates with Age-Related Macular Degeneration and High Complement Activation Levels in vivo. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loirat, C.; Frémeaux-Bacchi, V. Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2011, 6, 60. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdan, R.-G.; Anderco, P.; Ichim, C.; Cimpean, A.-M.; Todor, S.B.; Glaja-Iliescu, M.; Crainiceanu, Z.P.; Popa, M.L. Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome: A Review of Complement Dysregulation, Genetic Susceptibility and Multiorgan Involvement. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortajada, A.; Montes, T.; Martı́nez-Barricarte, R.; Morgan, B.P.; Harris, C.L.; de Córdoba, S.R. The disease-protective complement factor H allotypic variant Ile62 shows increased binding affinity for C3b and enhanced cofactor activity. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009, 18, 3452–3461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucientes-Continente, L.; Márquez-Tirado, B.; de Jorge, E.G. The Factor H protein family: The switchers of the complement alternative pathway. Immunol. Rev. 2022, 313, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-F.; Wang, F.-M.; Li, Z.-Y.; Yu, F.; Zhao, M.-H.; Chen, M. Plasma complement factor H is associated with disease activity of patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2015, 17, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, A.; et al. Genetic Variants Contributing to Circulating Matrix Metalloproteinase 8 Levels and Their Association With Cardiovascular Diseases: A Genome-Wide Analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2017, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Clayton, J.S.; Acemel, R.D.; Zheng, Y.; Taylor, R.L.; Keleş, S.; Franke, M.; Boackle, S.A.; Harley, J.B.; Quail, E.; et al. Regulatory Architecture of the RCA Gene Cluster Captures an Intragenic TAD Boundary, CTCF-Mediated Chromatin Looping and a Long-Range Intergenic Enhancer. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 901747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, W.; Walker, M.; Sweetman, E.; Helliwell, A.; Peppercorn, K.; Edgar, C.; Blair, A.; Chatterjee, A. Molecular Mechanisms of Neuroinflammation in ME/CFS and Long COVID to Sustain Disease and Promote Relapses. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 877772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komaroff, A.L.; Lipkin, W.I. ME/CFS and Long COVID share similar symptoms and biological abnormalities: road map to the literature. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1187163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil, A.; Hoag, G.E.; Salerno, J.P.; Hornig, M.; Klimas, N.; Selin, L.K. Identification of CD8 T-cell dysfunction associated with symptoms in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) and Long COVID and treatment with a nebulized antioxidant/anti-pathogen agent in a retrospective case series. Brain, Behav. Immun. - Heal. 2024, 36, 100720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iu, D.S.; Maya, J.; Vu, L.T.; Fogarty, E.A.; McNairn, A.J.; Ahmed, F.; Franconi, C.J.; Munn, P.R.; Grenier, J.K.; Hanson, M.R.; et al. Transcriptional reprogramming primes CD8+ T cells toward exhaustion in Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2024, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lage, S.L.; et al. Persistent immune dysregulation and metabolic alterations following SARS-CoV-2 infection. medRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Mandarano, A.H.; Maya, J.; Giloteaux, L.; Peterson, D.L.; Maynard, M.; Gottschalk, C.G.; Hanson, M.R. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome patients exhibit altered T cell metabolism and cytokine associations. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 1491–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervia-Hasler, C.; Brüningk, S.C.; Hoch, T.; Fan, B.; Muzio, G.; Thompson, R.C.; Ceglarek, L.; Meledin, R.; Westermann, P.; Emmenegger, M.; et al. Persistent complement dysregulation with signs of thromboinflammation in active Long Covid. Science 2024, 383, eadg7942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baillie, K.; Davies, H.E.; Keat, S.B.; Ladell, K.; Miners, K.L.; Jones, S.A.; Mellou, E.; Toonen, E.J.; Price, D.A.; Morgan, B.P.; et al. Complement dysregulation is a prevalent and therapeutically amenable feature of long COVID. Med 2024, 5, 239–253.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahearn-Ford, S.; Lunjani, N.; McSharry, B.; MacSharry, J.; Fanning, L.; Murphy, G.; Everard, C.; Barry, A.; McGreal, A.; al Lawati, S.M.; et al. Long-term disruption of cytokine signalling networks is evident in patients who required hospitalization for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Allergy 2021, 76, 2910–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.-J.; Liu, S.-H.; Manachevakul, S.; Lee, T.-A.; Kuo, C.-T.; Bello, D. Biomarkers in long COVID-19: A systematic review. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1085988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagiya, H.; Tokumasu, K.; Otsuka, Y.; Sunada, N.; Nakano, Y.; Honda, H.; Furukawa, M.; Otsuka, F. Relevance of complement immunity with brain fog in patients with long COVID. J. Infect. Chemother. 2024, 30, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, P.B.; Manzi, S.; Shaw, P.; Kenney, M.; Kao, A.H.; Bontempo, F.; Barmada, M.M.; Kammerer, C.; Kamboh, M.I. Genetic Variation in C-Reactive Protein (CRP) Gene May Be Associated with Risk of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and CRP Concentrations. J. Rheumatol. 2008, 35, 2171–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Wu, H.; Khosravi, M.; Cui, H.; Qian, X.; Kelly, J.A.; Kaufman, K.M.; Langefeld, C.D.; Williams, A.H.; Comeau, M.E.; et al. Association of Genetic Variants in Complement Factor H and Factor H-Related Genes with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Susceptibility. PLOS Genet. 2011, 7, e1002079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, J.M.; Edberg, J.C.; Kimberly, R.P. Pathways: Strategies for susceptibility genes in SLE. Autoimmun. Rev. 2010, 9, 473–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berndtson, K. Review of evidence for immune evasion and persistent infection in Lyme disease. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2013, 6, 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovis, K.M.; Tran, E.; Sundy, C.M.; Buckles, E.; McDowell, J.V.; Marconi, R.T. Selective Binding of Borrelia burgdorferi OspE Paralogs to Factor H and Serum Proteins from Diverse Animals: Possible Expansion of the Role of OspE in Lyme Disease Pathogenesis. Infect. Immun. 2006, 74, 1967–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parnell, G.P.; Booth, D.R. The Multiple Sclerosis (MS) Genetic Risk Factors Indicate both Acquired and Innate Immune Cell Subsets Contribute to MS Pathogenesis and Identify Novel Therapeutic Opportunities. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, G.; Hakobyan, S.; Robertson, N.P.; Morgan, B.P. Complement in multiple sclerosis: its role in disease and potential as a biomarker. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2009, 155, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negro-Demontel, L.; Maleki, A.F.; Reich, D.S.; Kemper, C. The complement system in neurodegenerative and inflammatory diseases of the central nervous system. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1396520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamers, C.; Mastellos, D.C.; Ricklin, D.; Lambris, J.D. Compstatins: the dawn of clinical C3-targeted complement inhibition. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 43, 629–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, J.M.; Kell, D.B.; Pretorius, E. Cardiovascular and haematological pathology in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS): A role for viruses. Blood Rev. 2023, 60, 101075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeves, W.C.; Jones, J.F.; Maloney, E.; Heim, C.; Hoaglin, D.C.; Boneva, R.S.; Morrissey, M.; Devlin, R. Prevalence of chronic fatigue syndrome in metropolitan, urban, and rural Georgia. Popul. Heal. Metrics 2007, 5, 5–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudlow, C.; Gallacher, J.; Allen, N.; Beral, V.; Burton, P.; Danesh, J.; Downey, P.; Elliott, P.; Green, J.; Landray, M.; et al. UK Biobank: An Open Access Resource for Identifying the Causes of a Wide Range of Complex Diseases of Middle and Old Age. PLoS Med. 2015, 12, e1001779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Dhindsa, R.S.; Carss, K.; Harper, A.R.; Nag, A.; Tachmazidou, I.; Vitsios, D.; Deevi, S.V.V.; Mackay, A.; Muthas, D.; et al. Rare variant contribution to human disease in 281,104 UK Biobank exomes. Nature 2021, 597, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Plasma component or fragment | Covariate | Coefficient | Std Error | Adjusted R² | F Statistic | p-value |

| CRP | BMI | 0.169 | 0.024 | 0.230 | 47.47 | 1.3E-10 |

| C3 | 0.033 | 0.004 | 0.269 | 63.11 | 2.7E-13 | |

| C3a | 0.036 | 0.008 | 0.102 | 20.28 | 1.2E-05 | |

| C5a | 0.025 | 0.005 | 0.106 | 21.06 | 8.7E-06 | |

| Factor B | 0.026 | 0.005 | 0.142 | 28.32 | 3.3E-07 | |

| Factor D | 0.020 | 0.004 | 0.113 | 22.62 | 4.2E-06 | |

| Factor H | 0.023 | 0.004 | 0.181 | 38.47 | 4.2E-09 | |

| Bb/C3 | -0.027 | 0.008 | 0.066 | 12.92 | 4.3E-04 | |

| CRP | Sex | 0.645 | 0.318 | 0.019 | 4.10 | 4.5E-02 |

| Factor B | 0.159 | 0.061 | 0.034 | 6.84 | 9.8E-03 | |

| Factor D | Age | 0.011 | 0.002 | 0.117 | 23.44 | 2.9E-06 |

| Pathway | Chromosome #: Gene name | SNP rsID |

ME/CFS risk allele (nt) |

Variant consequence |

Impacted complement protein (cis/trans) | β ± SE | p-value |

| Complement cascade | 6: C2 | rs9332739~ | Minor (C) | Missense (E318D) | Bb/C3 | -0.49 ± 0.13 | 1.9E-04 |

| Bb (cis) | -0.36 ± 0.12 | 0.002 | |||||

| Factor B (cis) | -0.23 ± 0.08 | 0.007 | |||||

| 6: CFB | rs4151667~ | Minor (T) | Missense (L9H) | Bb/C3 | -0.49 ± 0.13 | 1.9E-04 | |

| Bb (cis) | -0.36 ± 0.12 | 0.002 | |||||

| Factor B (cis) | -0.23 ± 0.08 | 0.007 | |||||

| rs641153 | Major (C) | Missense (R32L) | Factor B (cis) | 0.24 ± 0.07 | 0.001 | ||

| Bb/C3 | -0.24 ± 0.10 | 0.021 | |||||

| Factor D (trans) | -0.11 ± 0.05 | 0.046 | |||||

| 1: CFH | rs7529589* | Major (G) | Intronic | Factor H (cis) | 0.06 ± 0.03 | 0.020 | |

| Bb (trans) | 0.10 ± 0.05 | 0.036 | |||||

| rs1061147* | Major (G) | Codon-synonymous (A307A); splicing regulation | Bb (trans) | 0.12 ± 0.05 | 0.015 | ||

| rs800292 | Minor (T) | Missense (V62I) | Bb (trans) | -0.19 ± 0.06 | 0.003 | ||

| Bb/C3 | -0.21 ± 0.07 | 0.003 | |||||

| rs1061170* | Major (T) | Missense (H402Y) | Bb (trans) | 0.11 ± 0.05 | 0.025 | ||

| rs10801555 | Major (G) | Intronic | Bb (trans) | 0.12 ± 0.05 | 0.014 | ||

| 3: MASP1 | rs3774268 | Minor (T) | Missense (S445R) | Bb/C3 | -0.24 ± 0.08 | 0.003 | |

| Bb (trans) | -0.17 ± 0.07 | 0.026 | |||||

| 14: SERPINA5 | rs6115 | Minor (G) | Missense (S64N) | Bb/C3 | -0.11 ± 0.05 | 0.047 | |

| rs6108 | Minor (A) | UTR-3; miRNA binding | C3 (trans) | 0.07 ± 0.03 | 0.026 | ||

| T cell signaling | 2: CD8A | rs3020729 | Major (T) | UTR-3; miRNA binding | CRP (trans) | -0.67 ± 0.25 | 0.008 |

| C3 (trans) | -0.10 ± 0.05 | 0.028 | |||||

| Chemokine | 17: CXCL16 | rs2277680 | Major (G) | Missense (I142T; A200V) | Factor H (trans) | -0.06 ± 0.03 | 0.024 |

| Factor B (trans) | -0.08 ± 0.04 | 0.031 | |||||

| G-protein coupled receptor signaling |

5: PDE4D | rs2014012 | Major (A) | Intronic | C3a (trans) | -0.13 ± 0.06 | 0.036 |

| C5a (trans) | -0.09 ± 0.04 | 0.038 | |||||

| 4: GRK4 | rs1801058 | Major (C) | Missense (V486A); splicing regulation | C3 (trans) | -0.07 ± 0.03 | 0.034 | |

| TNF super family signaling |

13: TNFRSF19 | rs9550987 | Minor (T) | Missense (S31T); splicing regulation | C3 (trans) | 0.09 ± 0.03 | 0.011 |

| Factor H (trans) | 0.07 ± 0.03 | 0.027 |

| Variant | Gene | Genotype | Test variable |

Covariates | # of CFS | # of NF | # of subjects |

AUC ± SE | 95% CI | p-value |

| Single marker analysis | ||||||||||

| rs9332739 | C2/CFB | CG | Factor H | BMI | 10 | 7 | 17 | 0.89 ± 0.09 | 0.71 - 1 | 0.05 |

| rs800292 | CFH | CT | C3 | BMI | 20 | 41 | 61 | 0.82 ± 0.06 | 0.74 - 0.94 | 0.001 |

| Factor H | 0.78 ± 0.06 | 0.7 - 0.94 | 0.007 | |||||||

| CRP | Sex, BMI | 17 | 40 | 57 | 0.84 ± 0.05 | 0.72 - 1 | 0.04 | |||

| rs1061170 | TT | Factor B | Sex, BMI | 27 | 40 | 67 | 0.81 ± 0.06 | 0.7 - 0.92 | 0.03 | |

| rs10801555 | GG | Factor B | Sex, BMI | 26 | 38 | 64 | 0.81 ± 0.06 | 0.7 - 0.92 | 0.03 | |

| rs395544 | CC | Factor B | Sex, BMI | 20 | 36 | 56 | 0.83 ± 0.05 | 0.73 - 0.94 | 0.03 | |

| rs1065489 | GG | C3 | BMI | 27 | 61 | 88 | 0.75 ± 0.06 | 0.64 - 0.86 | 0.02 | |

| rs7135975 | C1R | AG | C3 | BMI | 16 | 43 | 59 | 0.76 ± 0.08 | 0.6 - 0.92 | 0.01 |

| rs7257062 | C3 | CC | C3 | BMI | 20 | 43 | 63 | 0.78 ± 0.06 | 0.65 - 0.91 | 0.006 |

| rs2241393 | CC | C3 | BMI | 18 | 38 | 56 | 0.81 ± 0.06 | 0.69 - 0.93 | 0.003 | |

| rs2241392 | CC | C3 | BMI | 19 | 43 | 62 | 0.78 ± 0.07 | 0.65 - 0.91 | 0.006 | |

| rs7037673 | C5 | CT | C3 | BMI | 16 | 45 | 61 | 0.82 ± 0.05 | 0.72 - 0.93 | 0.005 |

| Bb/C3 | 0.81 ± 0.06 | 0.69 - 0.93 | 0.006 | |||||||

| rs261753 | C9 | CC | CRP | Sex, BMI | 31 | 76 | 107 | 0.78 ± 0.05 | 0.69 - 0.87 | 0.04 |

| rs1986158 | CR1 | CT | C3 | BMI | 11 | 23 | 34 | 0.83 ± 0.09 | 0.65 - 1 | 0.009 |

| 2-marker analysis | ||||||||||

| rs9332739 & rs800292 | C2/CFH | CG/CT | CRP | Sex, BMI | 23 | 43 | 66 | 0.85 ± 0.05 | 0.76 - 0.94 | 0.046 |

| C3 | BMI | 26 | 45 | 71 | 0.84± 0.05 | 0.74 - 0.94 | 0.0004 | |||

| Factor H | 0.78 ± 0.06 | 0.67 - 0.89 | 0.003 | |||||||

| UK Biobank fatigue-related phenotype |

Chr #: Gene name |

Variant | Variant consequence (reference nt - variant nt) |

UK biobank: cases / healthy controls |

SNP - UK biobank phenotype odds ratio |

SNP - UK biobank phenotype odds ratio confidence interval |

SNP – UK biobank phenotype p-value |

SNP – Impacted Complement protein p-value |

| Chronic Fatigue Syndrome | 17: PIK3R5 | rs394811 | Synonymous (G-A) | 2047 / 307792 | 0.847 | 0.75 - 0.96 | 0.007 | 0.002 (C3) |

| Post Viral Fatigue Syndrome | 6: CFB | rs641153 | Missense (G-A) | 4363 / 216118 | 0.571 | 0.38 - 0.86 | 0.005 | 0.001 (CFB) |

| 11: MMP10 | rs17293607 | Missense (C-T) | 4360 / 216027 | 0.920 | 0.86 - 0.98 | 0.009 | 0.004 (C5a) | |

| 41202/R53 Fatigue & Malaise |

1: CFH | rs800292 | Missense (G-A) | 2132 / 283735 | 0.754 | 0.61 - 0.94 | 0.010 | 0.003 (Bb) |

| Ever CFS | 6: C2 | rs9332739 | Missense (G-C) | 2547 / 121864 | 1.186 | 1.05 - 1.34 | 0.008 | 0.002 (Bb) |

| 6: CFB | rs4151667 | Missense (T-A) | 2547 / 121863 | 1.185 | 1.05 - 1.34 | 0.009 | 0.002 (Bb) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).