1. Introduction

Air pollution remains one of the biggest environmental challenges of the 21st century, with detrimental effects on human health and ecosystems. It is estimated to have caused 4.2 million premature deaths worldwide in 2019 [

1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has established air quality guidelines, recommending threshold concentrations for the major pollutants to minimize adverse health impacts, but many urban areas globally continue to exceed these limits, especially in densely populated and industrial regions. The main air pollutants include nitrogen dioxide (

), ozone (

), and particulate matter (

), especially

and

.

, primarily emitted from traffic and industrial activities, contributes to respiratory stress and acts as a precursor to ozone and secondary particulate matter. Ground-level ozone, beneficial in the stratosphere, becomes harmful at the surface, where it exacerbates asthma and impairs lung function. Long-term exposure to these pollutants (especially

and

) has also been associated with neurodegenerative outcomes such as Alzheimer’s, likely via oxidative stress mechanisms [

2,

3,

4]. Moreover, particulate matter (

and

) poses a significant risk due to its ability to penetrate deep into the respiratory tract.

, with aerodynamic diameter below 2.5

, can reach the alveoli and the bloodstream, promoting cardiovascular and pulmonary disease, while

can still induce severe respiratory effects, especially in vulnerable populations [

5]. Taken together, this evidence frames a concrete scientific requirement: exposure assessment must move beyond sparse point monitoring and provide spatially continuous pollutant fields with both high spatial resolution (hundreds of meters, i.e. neighborhood scale) and daily temporal coverage, so that vulnerable sub-populations can be studied in realistic conditions. Producing such maps in a physically consistent and interpretable way is currently one of the open challenges in atmospheric exposure science.

In recent years, Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL) models have emerged as powerful tools to estimate air pollution where monitoring is sparse. Méndez et al. [

6] reviewed 155 studies (2011–2021) and reported a dominant use of ML methods such as Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forests (RF), and boosted trees, as well as DL architectures (e.g. CNN–LSTM for

forecasting [

7], GRU models for particulate in Beijing [

8], and LSTM-based AQI predictors in smaller cities [

9]). Typical inputs combine satellite retrievals (column NO

2/O

3, Aerosol Optical Depth, AOD), reanalysis meteorology (e.g. ERA5), land-use/road/population layers, and sometimes chemical-transport model (CTM) outputs [

10,

11]. Recent models provide maps at 1–10 km resolution nationally, and in some urban cases down to ∼1 km [

10,

11]; most target daily means, with hourly prediction remaining difficult due to stochastic variability and sparse ground truth [

12,

13]. Despite these advances, the existing literature still faces critical limitations that become especially important when one aims to use the resulting maps for health, regulatory or One Health applications. In fact, several issues recur: domain shift across years or regions, which degrades generalization [

12]; sparse and uneven ground networks, which limit spatial cross-validation and leave rural areas under-represented [

12]; reliance on static proxies (roads, land use, population) that do not fully capture day-to-day emission variability [

13]; vertical representativeness and unit mismatches between satellite columns and true surface concentrations, with gaps due to clouds or retrieval limits [

14]; propagation of CTM uncertainties from emission inventories and physics [

15,

16]; and limited interpretability and uncertainty quantification, which complicates policy and health applications [

12,

13,

17]. In other words, most ML air quality studies either: offer high spatial detail but limited interpretability and uncertain temporal generalization, or ensure robustness at broad scales but lose the fine-scale gradients that drive within-city exposure differences. A key open scientific direction is therefore to build frameworks that integrate heterogeneous predictors (satellite, meteorology, land use, population, temporal cycles), resolve sub-kilometer spatial structure, and remain explainable enough to relate model behavior back to known atmospheric processes such as photochemistry, dispersion and boundary-layer mixing. A central technical obstacle in that direction is the fusion of satellite products with ground-level concentrations. Ground-based stations provide accurate local concentrations in

, but they are sparse and often missing in rural areas. Satellites such as Sentinel-5P provide near-daily, spatially extensive measurements of pollutants like

and

, but these are reported as tropospheric columns in

, integrating the whole atmospheric column rather than strictly surface air. This introduces spatial smoothing and weakens direct correspondence with near-surface exposure [

14]. This mismatch is not only a data availability problem: it is also a physical problem. Satellite tropospheric columns integrate contributions from the free troposphere and are only indirectly sensitive to boundary-layer pollution, whereas health-relevant exposure is driven by near-surface chemistry, emission plumes, and local dispersion. Therefore, a simple linear correlation between column retrievals and surface concentrations is generally weak, particularly for

. In our view, this is exactly where machine learning is scientifically valuable, since non-linear ensemble models can learn interactions between satellite columns, meteorological structure (e.g. wind, mixing height, temperature), and land-use/emission proxies to infer ground-level fields even where no stations are present.

In this work we implement such a framework in a real, operationally relevant setting. We developed a machine learning pipeline to predict daily surface concentrations of

,

,

and

across the Apulia (Puglia) region in Southern Italy, at 300 m spatial resolution, using ground measurements from ARPA (Regional Environmental Protection Agency) stations as reference. Our model integrates Sentinel-5P column products; high-resolution meteorological variables from a regionally validated WRF configuration, downscaled and temporally aggregated; fine-scale land-use and anthropogenic indicators (road network density, building density, population); and temporal harmonics. We then apply explainable AI (XAI) via SHAP to interpret which predictors drive each pollutant and to link model behavior to known atmospheric processes. Our approach is not limited to “applying AI in a new geographical area”. Methodologically, it combines Sentinel-5P column products; high-resolution meteorological variables from a regionally validated WRF configuration, downscaled and temporally aggregated; fine-scale land-use and anthropogenic indicators (road network density, building density, population); and explicit explainability via SHAP to interpret which predictors drive each pollutant. This integration enables daily exposure maps at 300 m resolution, which is substantially finer than the 1–10 km scale that is typical for national products, while remaining interpretable in terms of known atmospheric drivers (e.g.,

linked to traffic/industry;

linked to temperature and photochemistry; PM linked to AOD and resuspension). We focused on Apulia because it concentrates densely populated coastal cities and major industrial/port areas (notably Bari and Taranto), including the Acciaierie d’Italia (ex ILVA) steelworks in Taranto, one of Europe’s largest steel plants [

18,

19,

20]. This setting combines intense industry, compact Mediterranean urban form with traffic-dominated

, strong land–sea breeze systems that modulate recirculation, and complex

photochemistry under high insolation. To the best of our knowledge, there are currently no data-driven models producing daily, 300 m resolution surface maps of air pollution for Apulia. Previous efforts either target specific districts without fine-scale mapping [

21], provide national-scale predictions at coarser administrative or grid resolutions using Sentinel-5P and ERA5 [

22], or rely on chemical transport models (e.g. WRF–CMAQ, CAMx, WRF-Chem) for scenario analysis and source apportionment [

15,

16,

23], which are computationally expensive and typically run at km-scale resolution. From a scientific perspective, Apulia is not only a case study but also a stress test for the broader field. The region combines intense industrial activity (steel production, port logistics), compact Mediterranean coastal cities with traffic-dominated

, strong land–sea breeze systems that modulate dispersion and recirculation, and complex

photochemistry under high insolation. A model that can generate daily 300 m maps and explain its own predictions under these conditions provides evidence that high-resolution, explainable air quality estimation is feasible in other coastal industrial regions with limited monitoring. In summary, this study delivers a regional-scale, daily 300 m resolution exposure product for four key pollutants (

,

,

,

) over Apulia, an assessment of its spatial and temporal generalization, and an interpretation of pollutant drivers via SHAP. The overarching contribution is to demonstrate an interpretable satellite–meteorology–land-use fusion framework that is transferable to other Mediterranean and coastal industrial regions, rather than a location-specific technical exercise. In this analysis, we excluded sulfur dioxide (

) and carbon monoxide (

) from the prediction task due to their low ambient concentrations in the region [

24,

25].

3. Results

After the preprocessing phase, we developed two models for pollutant prediction. Specifically, we used linear regression as a benchmark model and an ensemble learning algorithm, XGBoost. As in our previous work, we found that the Random Forest model achieves similar performance to the XGBoost model but requires more computational time; therefore, we did not include it in the analysis [

22].

Table 4 reports the performance metrics evaluated during the training phase.

Table 4 shows that XGBoost substantially outperforms the linear model for all pollutants in random 5-fold CV repeated 10 times. For

,

increases from

(linear) to

(XGBoost), with a mean absolute error (MAE) reduction of about 2.4

.

and

also benefit from the non-linear model, with

rising from 0.18 (linear) to 0.64 and 0.67, respectively. This indicates that particulate matter fields are strongly driven by non-linear interactions among satellite-based AOD, meteorology, and land-use variables, which are not captured by a purely linear formulation. For

, the

reaches

, confirming that—despite the known weak linear relationship between tropospheric column

and surface

—the model can still recover useful predictive structure once meteorology and temporal features are included. Overall, random CV demonstrates that tree-based fusion of satellite, meteorology, land-use and temporal harmonics provides accurate daily predictions at 300 m resolution.

Across pollutants, performance is differentiated. and the particulate fractions (, ) exhibit high accuracy and low RMSE, reflecting their strong link to localized emission patterns (traffic, industrial areas) and aerosol load, respectively. achieves similar apparent under random CV, but as we will discuss below, ozone behaves very differently under temporal generalization.

The results reported in

Table 4 are obtained through a 5-fold cross-validation (CV) procedure repeated 10 times. After confirming that the XGBoost model performed better than the linear model, we predicted air quality (4 pollutants) for the entire territory of the Apulia region.

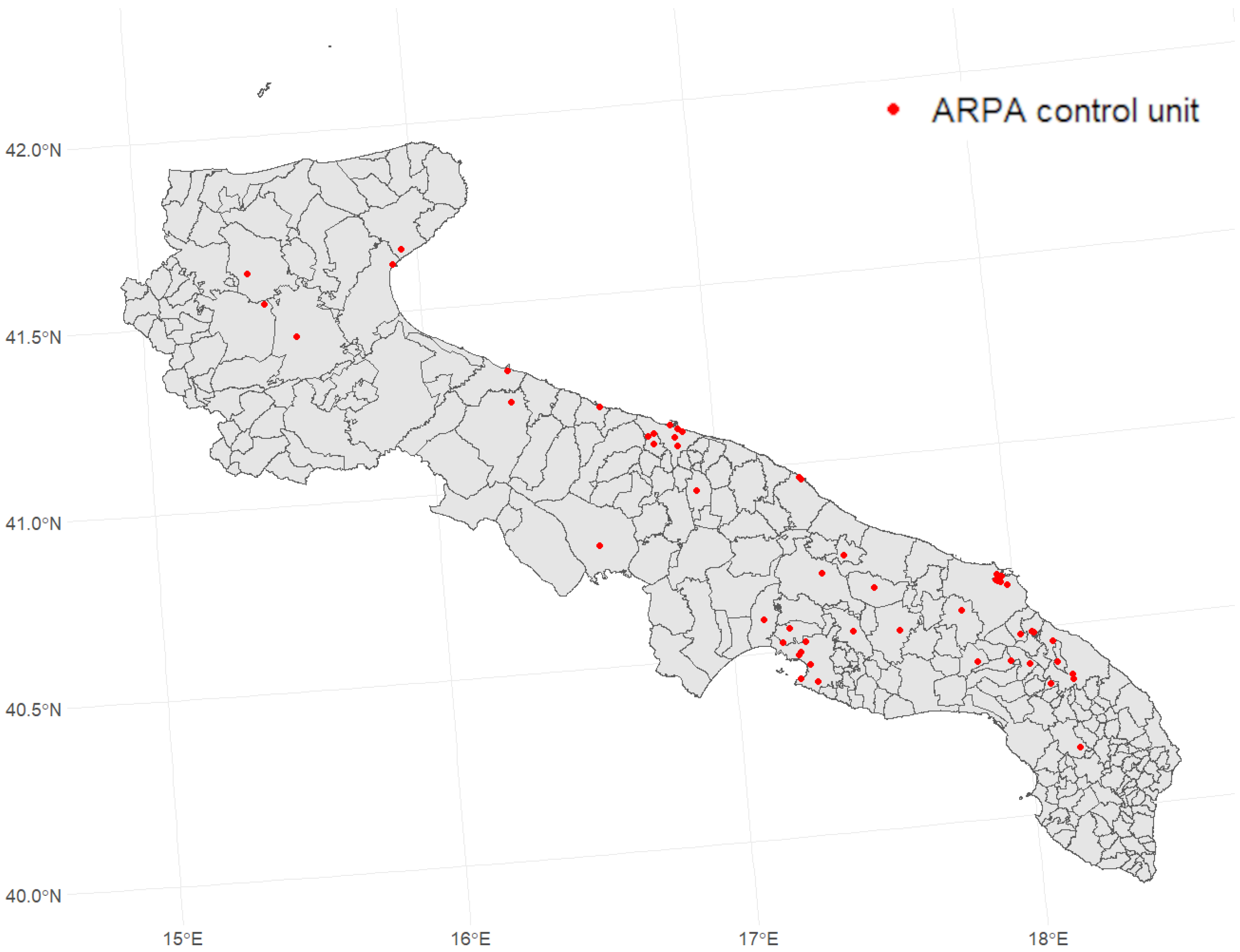

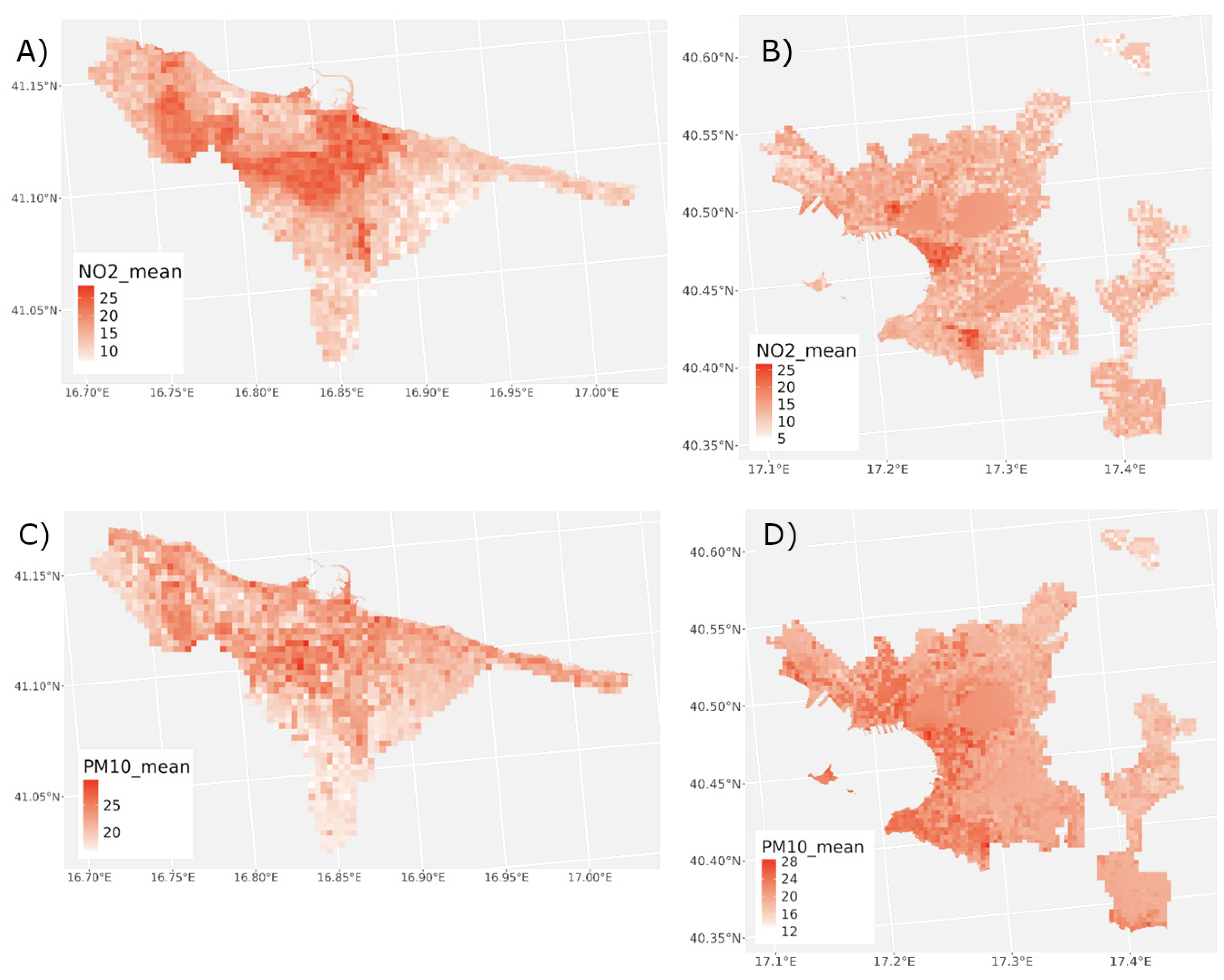

Figure 4 shows the daily concentration of

,

,

, and

predicted by means of our framework and averaged over the considered time interval.

Spatially, the map highlights dense urban/industrial corridors, especially around Bari and Taranto, with sharp intra-urban gradients at the 300 m scale. Particulate matter (, ) shows broader plumes, including higher values in coastal and harbor/industrial areas, consistent with resuspension, port activity, and industrial processes. In contrast, appears more spatially homogeneous at regional scale, with smoother inland gradients that reflect its secondary, photochemically formed nature and regional transport rather than purely local emissions. These spatial patterns are consistent with known atmospheric behavior of primary vs. secondary pollutants.

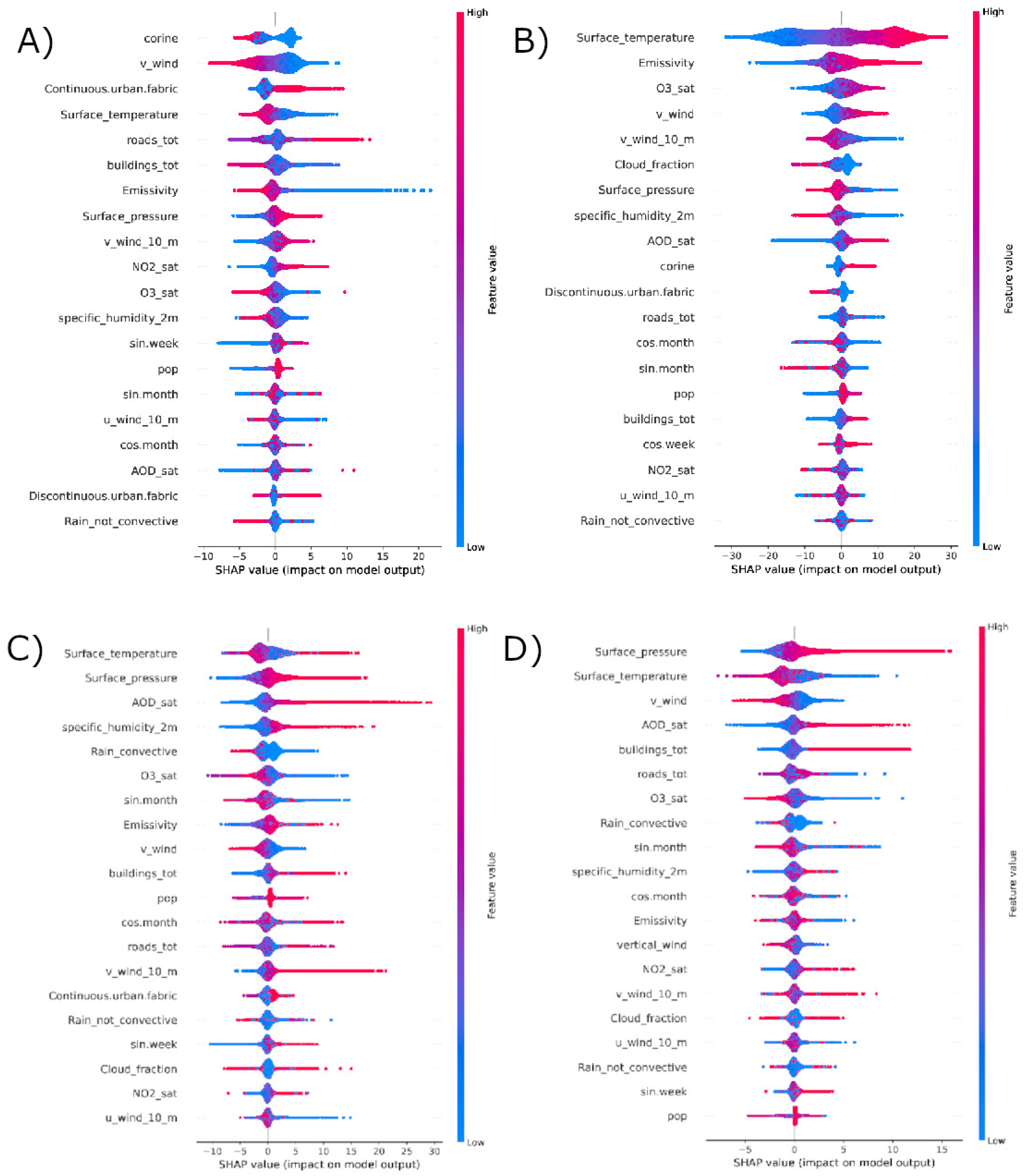

To better understand the reasoning behind the model’s predictions, we applied the SHAP algorithm, which highlighted the most influential variables and their relationship with the model’s output, as shown in

Figure 5.

For , SHAP ranks land-use and anthropogenic predictors (road network density, built-up/industrial fabric from CORINE, population density) and meteorological dispersion variables (wind speed) among the top drivers. High road density and continuous urban fabric push predictions upward, pointing to traffic and industrial combustion as dominant local sources. Wind speed contributes with negative SHAP values at high intensity, consistent with dilution and advection away from sources. Temperature shows a generally negative contribution at higher values, in line with the known seasonal cycle of (winter accumulation under stable conditions vs. enhanced mixing and photochemical removal in summer).

For and , SHAP attributes a strong positive role to AOD, confirming that the calibrated multi-source AOD field encodes aerosol load relevant to surface PM. Meteorological variables such as wind and precipitation act in the expected direction: higher wind speed and rainfall tend to reduce predicted particulate levels through dispersion and wet scavenging. Land-use features (industrial/urban classes) also contribute positively, but their SHAP magnitude is generally lower than AOD and meteorology, reflecting the more regional nature of particulate burden.

For , SHAP identifies temperature and emissivity (a proxy linked to surface energy balance and thus photochemical activity) as strong positive drivers, consistent with being formed photochemically under warm, sunny, stagnant conditions. Wind speed shows non-trivial effects, suggesting both transport and recirculation. Importantly, the Sentinel-5P tropospheric column appears as a meaningful predictor despite the low raw Pearson correlation (0.10) with ground-level : SHAP indicates that the model leverages this satellite feature in interaction with meteorology and land cover, rather than as a simple linear proxy. This supports the view that non-linear ML is needed to extract surface-relevant information from column-integrated products.

We acknowledge that the raw Pearson correlation between the tropospheric

column and surface

is low (R ≈ 0.1), but low marginal linear correlation does not imply that a variable lacks predictive value in non-linear, interaction-based ensembles such as XGBoost. In gradient boosting, trees combine features hierarchically through splits and interactions, so a predictor can become informative conditionally—e.g., above specific temperature thresholds, under particular wind regimes or boundary-layer stability, or in locations with distinct land-use/NO

x availability—even if its global linear association with the target is weak. This is a well-established property of boosted trees and modern feature selection theory: univariate correlation is an unreliable proxy for utility in non-linear models, whereas embedded/wrapper approaches and post-hoc attributions are preferred [

57,

58,

64,

65,

66]. Consistently, TreeSHAP provides additive, locally accurate attributions for tree ensembles; in our O

3 model, SHAP assigns a non-negligible contribution to the Sentinel-5P column precisely when meteorology and land/emission proxies create favorable photochemical/background conditions, confirming interaction-driven use rather than any one-to-one mapping [

62,

63].

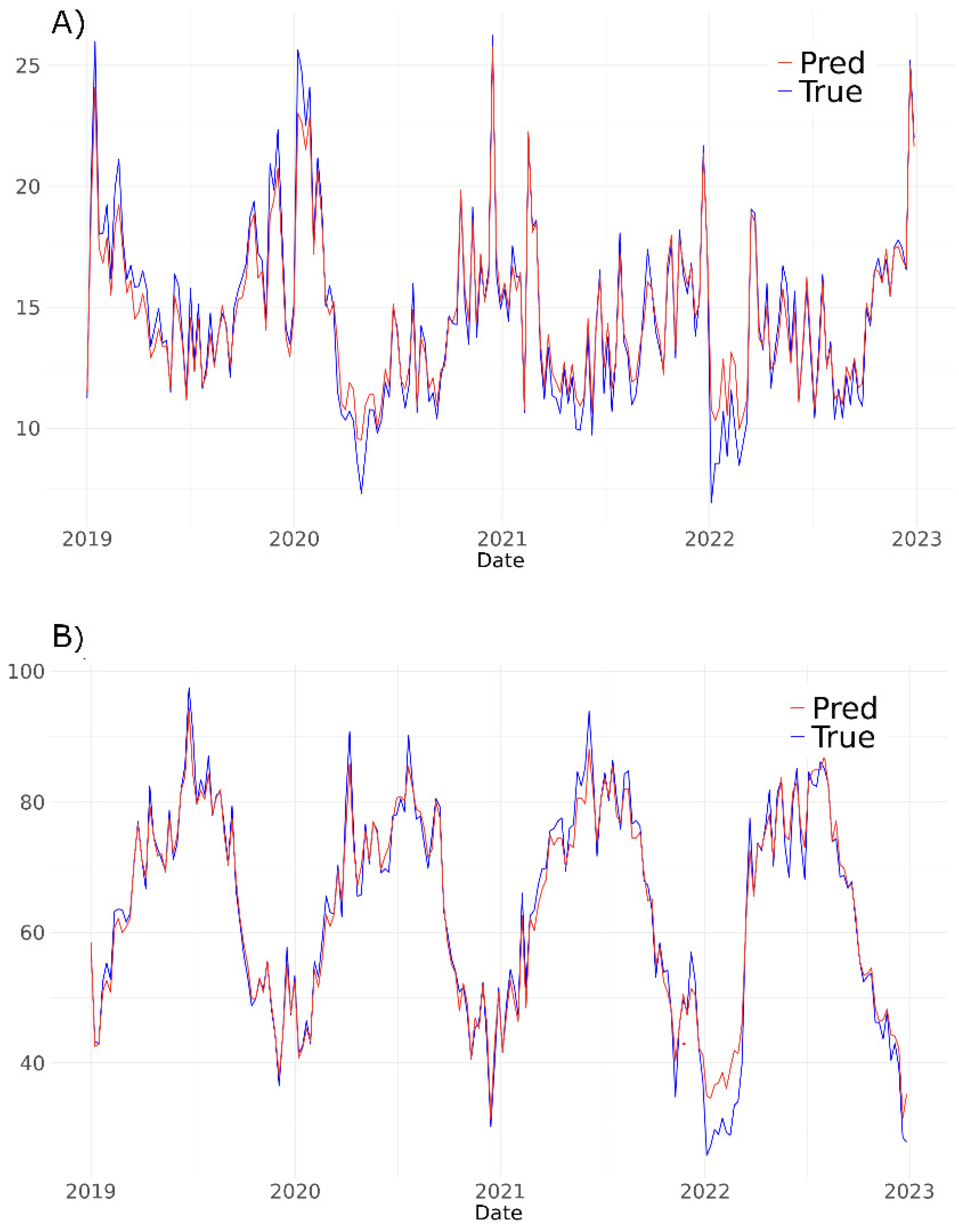

Figure 6 shows the trend of the predicted concentrations of

and

compared to the ground values (our labels), averaged over all ground stations. To obtain this plot we applied a Random CV procedure.

The temporal evolution in

Figure 6 shows that the model reproduces the seasonal cycles of both pollutants.

peaks in winter and drops in summer, reflecting lower atmospheric mixing heights and more intense combustion/traffic demand in the cold season.

instead peaks in the warm season, consistent with photochemical production under high temperature and radiation. The anti-correlation between the two is evident (high

/ low

in winter and vice versa in summer), and is well captured by the model. The largest discrepancies between prediction and ground truth occur during extreme or transient episodes, which is expected given the limited number of ARPA monitoring stations and the fact that highly localized spikes (e.g. short-lived plumes, stagnation events) are harder to generalize regionally.

To assess the temporal generalization ability of the model, we adopted a different cross-validation approach. In particular, we applied a LOYO (Leave One Year Out) strategy, splitting the dataset by year.

In this procedure the model was trained for three years (we considered the time interval 2019–2022) and tested for the remaining year. This procedure was repeated to ensure that each year was used at least once for both testing and training.

Table 5 shows the performance metrics (MAE, RMSE,

) obtained with this approach. Additionally, we summarized the predictions to monthly and yearly averages to observe possible seasonal trends. We decided not to perform spatial cross-validation (which is widely used in the literature), as the small number of measurement stations would lead to a bias in the model.

Table 5 evaluates a much harder task: predicting an unseen year (LOYO). As expected, daily-scale

drops for all pollutants compared to random CV (

Table 4), because LOYO tests temporal transferability under different meteorological regimes and emission patterns.

remains relatively robust (

daily), confirming that the model captures persistent spatial structure of primary emissions (traffic, industry).

and

show lower daily

(0.24 and 0.30), which reflects their higher stochastic variability (episodic dust resuspension, Saharan intrusions, industrial events) and the limited number of monitors. Critically,

exhibits

at daily scale, lower than its random-CV

. This indicates that ozone is the least temporally transferable pollutant in our framework, consistent with the fact that

depends on interannual meteorology and chemistry (photochemistry,

titration, boundary-layer recirculation), and that satellite

columns capture large-scale background rather than purely local boundary-layer behavior.

However, when we aggregate predictions to monthly and yearly means, performance markedly improves for all pollutants. For example, reaches at the annual scale, and reaches . Even , while still more variable, reaches at the monthly scale. This suggests that although day-to-day prediction of certain episodes is challenging across years, the model is robust for exposure assessment at epidemiologically relevant aggregation windows (monthly/annual), which are commonly used in long-term health and policy studies.

Through our model we can produce maps at the municipality level to do a focus on more local realities.

Figure 7 shows the average predicted values of

and

in the municipality of Bari and Taranto respectively.

In Bari, hotspots align with dense road networks and industrial/port areas, consistent with traffic-related and combustion-related sources. shows elevated levels both in industrial zones and along the coastline. This coastal enhancement is in line with AOD-informed particulate fields and may reflect port activity, industrial processes, and resuspension of marine/harbor aerosols. A similar pattern is observed in Taranto, where is highest in the Tamburi district (adjacent to the steel plant area) and along major traffic corridors, while is enhanced over coastal/industrial sectors rather than uniformly over the whole urban core. This confirms that the model can resolve intra-urban patterns that are meaningful for local environmental management.

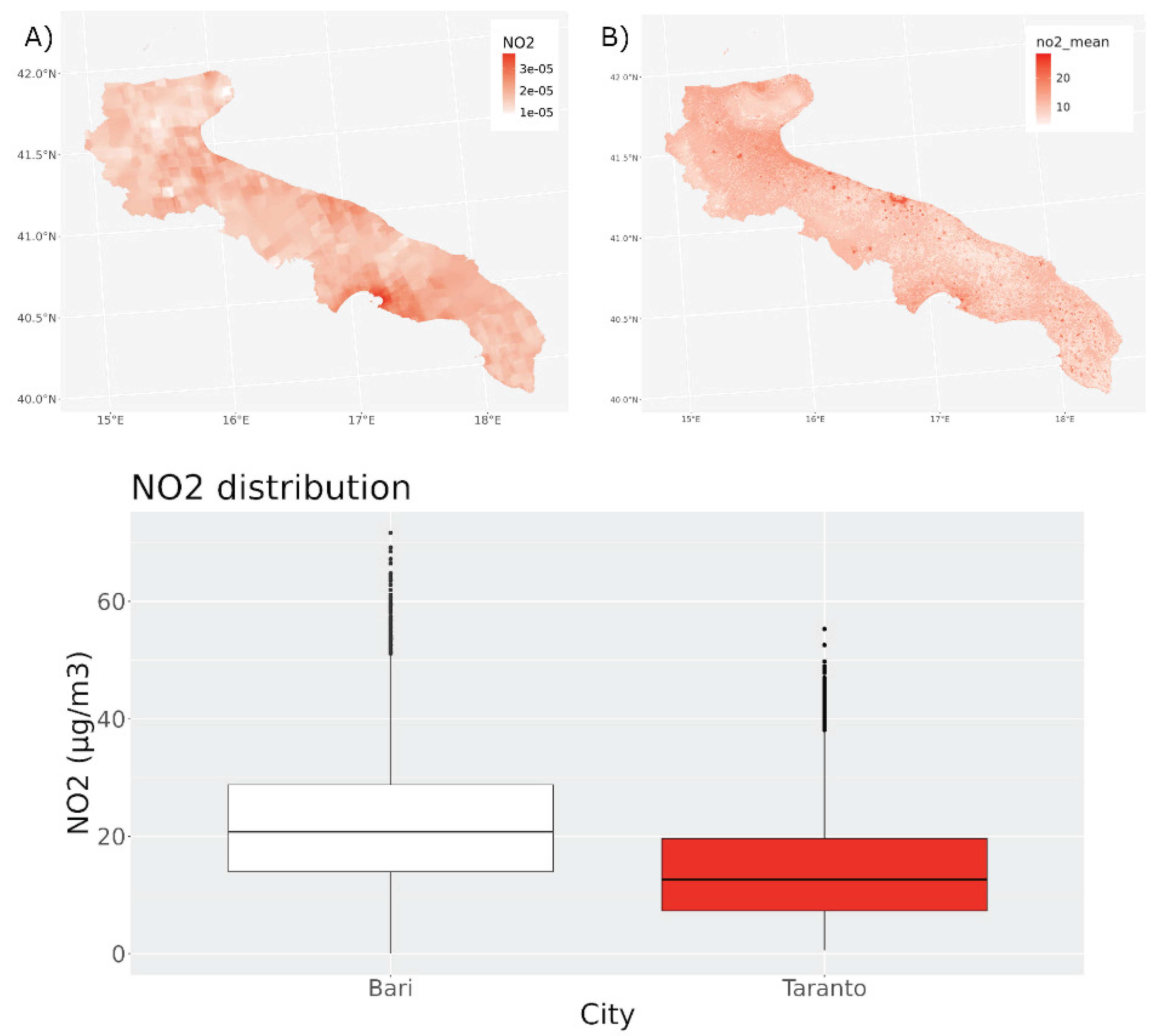

Figure 8 also highlights a key advantage of the proposed approach. Sentinel-5P tropospheric

mainly highlights large aggregated plumes (e.g. Taranto), whereas the model’s predicted surface

field captures much finer spatial gradients, including within Bari. When compared with ARPA ground measurements, both Bari and Taranto show elevated

, but Bari exhibits even higher average concentrations despite the absence of a single dominant point source like the steel plant. This is consistent with population density data (Bari ≈ 2700 inhabitants/km

2 vs Taranto ≈ 750 inhabitants/km

2) and intense traffic-related emissions. In other words, the model recovers both industrial and traffic-driven exposure patterns, which are not equally visible in the satellite column alone.

Temporal behavior (

Figure 6), spatial distribution at 300 m (

Figure 4,

Figure 7), and feature attribution via SHAP (

Figure 5) together indicate that the model is not only fitting statistical structure, but is reproducing physically and chemically consistent patterns: winter

buildup under low wind; warm-season

peaks driven by photochemistry; enhanced

near coastal/industrial zones tracked by AOD; and stronger spatial persistence of

hot spots across years compared to the more meteorology-driven

.

4. Discussion

As shown in

Table 4, the XGBoost model outperforms the linear model across all pollutants under random CV. This confirms that non-linear, interaction-aware models are required to fuse heterogeneous predictors (satellite columns, meteorology, AOD, land-use, temporal harmonics) and to translate them into surface-level pollutant concentrations at 300 m resolution. The results are consistent with other studies in the literature. Stafoggia et al. achieved an average

of 0.75 for daily predictions of

and

across Italy at ∼1 km resolution [

67]. Our

and

values (0.67 and 0.64 in

Table 4) are slightly lower, which is expected because: we work at a finer spatial scale (300 m instead of ≥1 km), increasing spatial variability to be explained; and we rely on a smaller and regionally concentrated monitoring network within Apulia, rather than hundreds of stations nationwide. This resolution effect is well known: moving from kilometer to sub-kilometer grids sharpens intra-urban contrasts (traffic corridors, port areas, industrial districts), which increases variance to be predicted and therefore mechanically lowers apparent

at the pixel level.

The performance of our model in predicting

and

is also comparable to or better than values reported in the Italian literature. Silibello et al. report

for

and

for

using hybrid modeling over the whole Italian territory at ∼1 km resolution [

68]. In our case, random CV reaches

for

and

for

(

Table 4), again despite the more stringent (300 m) spatial resolution. This is notable because our study region is meteorologically complex (coastal recirculation, alternating land–sea breeze regimes, intense summer photochemistry) and industrially heterogeneous (steel, port logistics, traffic), which typically complicates surface pollutant modeling. The fact that the model maintains high skill in this setting suggests that even with fewer monitoring stations, high-resolution anthropogenic features (road density, port/industrial land-use, continuous urban fabric), and localized meteorology (WRF downscaled and resampled to 300 m) provide enough structure to generalize.

When compared to studies outside Italy, our performance is broadly in line with machine learning air quality models developed in other complex regions. For example, Di et al. reported

values in the 0.7–0.9 range for daily

across the continental United States at ∼1 km by combining satellite AOD, chemical transport model (CTM) output, land-use, and meteorology through an ensemble of statistical and machine learning learners [

10]. Li et al. obtained

values around 0.7–0.8 for

in China using deep ensemble approaches and rich station networks [

11]. In Beijing and other megacities, deep recurrent models (LSTM, GRU, CNN-LSTM hybrids) used for

forecasting often report high predictive skill [

7,

8]; however, these studies typically operate in settings with dozens of stations within a single urban basin and do not always target sub-kilometer mapping of long-term exposure fields. Our framework, by contrast, is designed to deliver exposure fields at 300 m across an entire region that contains multiple distinct urban/industrial systems (Bari, Taranto, coastal logistics, rural inland). In this sense, our approach is closer to regional exposure mapping than to single-city forecasting, while retaining a spatial resolution that is comparable to neighborhood/block scale.

From a public health perspective, this point is non-trivial. Epidemiological and One Health studies increasingly focus on chronic exposure at intra-urban scale (tens to hundreds of meters), because population vulnerability is not uniform within a city: residential areas sit next to major roads; schools and hospitals may lie downwind of ports or industrial stacks; disadvantaged neighborhoods are often co-located with legacy industrial sources and high traffic load. Our 300 m pollutant fields aim exactly at that scale. This is in line with recent air quality exposure work in North America and Northern Europe that emphasizes environmental justice and differential exposure, where within-city gradients are policy-relevant on their own and cannot be inferred from sparse fixed-site monitors alone [

10,

11].

As expected for data-driven models, LOYO CV exposes reduced daily performance due to year-to-year regime shifts, the limited number and uneven distribution of monitors, and the weaker seasonality and higher stochastic variability of PM. However, aggregating predictions to monthly and annual scales markedly improves

(

Table 5), supporting use for exposure assessment and One Health applications. In epidemiology and regulatory assessment, exposure is often averaged over months or years rather than interpreted day by day; our LOYO monthly

values (

–

for

,

, and

) indicate that such aggregated exposure fields are reliable even when an entire year is held out of training. This is important because it shows that the model is not just interpolating noise from individual days, but is actually able to reconstruct the long-term spatial structure of exposure that matters for cardiovascular, respiratory, and neurodegenerative risk analyses [

2,

3,

4].

The differentiated behavior among pollutants has a clear atmospheric interpretation.

is a short-lived, primarily emitted pollutant tied to combustion (traffic, port activity, industrial stacks). Its spatial pattern is persistent in time (urban cores, road networks, industrial/harbor districts), and therefore

remains relatively robust in LOYO (

daily). This agrees with prior work in Italy and across Europe, where

gradients are dominated by local emission intensity and street-scale dispersion [

67,

68]. In Apulia we observe the same structure: SHAP shows that

predictions increase sharply in areas with high road density, dense built-up fabric, and industrial land-use (

Figure 5); wind speed carries strong negative SHAP values at high intensity, consistent with pollutant dilution. This supports a mechanistic reading: the model is not only “fitting” data, it is reconstructing physically interpretable source–dispersion relationships.

and

behave differently. Particulate matter in Apulia reflects both persistent sources (traffic, industry, port logistics, heating) and episodic inputs (resuspension, harbor/ship emissions, Saharan dust intrusions, stagnant meteorology). This mixture of steady and episodic drivers explains why daily LOYO skill is lower (

–

) than for

, and why performance improves so strongly after temporal aggregation (up to

=

for annual

). SHAP indicates that AOD is a dominant positive driver for both

and

, while precipitation and stronger winds tend to suppress particulate levels (negative SHAP at high values). This is fully consistent with atmospheric physics: wet scavenging and ventilation remove particles, while dry, stagnant, high-AOD conditions favor accumulation. The spatial patterns we predict (

Figure 4 and

Figure 7) show

and

enhancements along coastal/industrial belts and port zones, including areas in Bari and Taranto with intense maritime and logistics activity. Similar harbor-related particulate enhancements have been described in other Mediterranean port cities, where ship emissions and bulk handling (e.g. minerals, coal, grain) locally elevate aerosol load [

23,

69].

represents the most conceptually challenging pollutant. Unlike

and primary PM, surface ozone is not directly emitted. It is formed photochemically from nitrogen oxides (NO

x) and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) under sunlight, and then shaped by transport, entrainment from the residual layer,

titration in traffic corridors, and boundary-layer dynamics. In coastal Mediterranean regions like Apulia, land–sea breeze circulations and recirculation cells can trap and re-inject aged air masses rich in photochemical products. This means that day-to-day

fields depend strongly on meteorology and chemistry, and the surface

level is not simply proportional to the instantaneous tropospheric

column observed by Sentinel-5P. Indeed, previous studies have repeatedly emphasized that satellite tropospheric ozone columns correlate only weakly and inconsistently with surface ozone, because they integrate also the free troposphere and large-scale background [

14,

70].

Our results are consistent with this view. In random CV, where the model is trained and tested within overlapping seasonal regimes,

achieves

(

Table 4). Under LOYO, daily

drops to

(

Table 5), highlighting that interannual variability in solar radiation, stagnation events, and photochemical regimes is difficult to extrapolate. Importantly, SHAP reveals that

predictions are driven by temperature, emissivity (a proxy for surface energy balance and thus photochemical potential), and wind-related variables, with Sentinel-5P

column still contributing positively in interaction with these drivers. That is: the column ozone on its own is not a good linear predictor, but in combination with meteorology and land-use it contains usable signal. This is exactly the scientific motivation for applying non-linear ML instead of simple regression.

From a modeling standpoint, this is also fully consistent with the theory of gradient boosting and modern feature selection: tree ensembles capture interactions and threshold effects without requiring large marginal correlations [

57,

58,

64]. Consequently, correlation filtering is not an adequate criterion to discard features in non-linear pipelines; embedded methods and post-hoc attributions (e.g., SHAP) are more appropriate to evaluate contextual usefulness [

62,

63,

65,

66].

The ozone result has two implications. First, it confirms that

is intrinsically harder to generalize temporally than

or PM, which explains why

-health analyses often rely on multi-year averages or warm-season metrics rather than raw daily values. Second, it suggests clear directions for future improvement: adding explicit predictors of boundary-layer height, stagnation/recirculation indices, and VOC proxies (e.g. land-cover classes indicative of biogenic VOC emissions, or industrial/port VOC sources) could capture more of the chemistry that drives

, especially in summer. This is aligned with recent calls in atmospheric modeling to hybridize physics and ML, using chemical transport model outputs as structured predictors while still letting data-driven methods learn residual structure [

15,

16].

SHAP analysis more broadly confirms that the model is physically consistent and therefore interpretable for policy. For , strong positive SHAP values are associated with dense built-up fabric, major roads, and industrial land-use; wind speed carries negative SHAP at high intensity, consistent with dispersion. For /, AOD is the top positive predictor, and precipitation/ventilation act as sinks. For , temperature and emissivity (radiative forcing at the surface) play a central role, encoding the photochemical engine of ozone formation. This level of interpretability helps ensure that predicted maps can be discussed with air quality agencies and health stakeholders without treating the ML model as an opaque “black box”.

Spatially, the 300 m maps (

Figure 4 and

Figure 7) and the comparison with ARPA measurements (

Figure 8) highlight two important policy-relevant findings. First,

exposure in Apulia is not confined to a single point source (e.g. the Taranto steel complex), but also reaches high levels in dense urban/traffic environments like Bari, where population density and mobility are high. This means that industrial liability alone cannot explain the observed

burden: diffuse transport-related emissions in dense coastal cities can produce comparable or higher average exposure, as confirmed by ARPA station data. Second,

hotspots align with industrial/port and coastal areas, suggesting that harbors and shoreline logistics contribute to particulate exposure, not only classical industrial stacks. This supports targeted mitigation strategies (harbor electrification, dust suppression, traffic control near port gates) that are already being discussed in several EU port cities.

From a regulatory standpoint, these results are coherent with the 2024 EU Air Quality Directive, which explicitly encourages Member States to combine monitoring networks with modeling and satellite data to generate high-resolution exposure assessments over populated areas, rather than simply multiplying fixed stations. Our framework directly responds to that directive: it fuses remote sensing, meteorology, and land-use to produce daily fields at 300 m, and it remains stable (especially after temporal aggregation) even when an entire year is withheld in training. This is relevant not only for compliance reporting, but also for health impact assessment and One Health planning in regions where industrial activity coexists with densely populated urban waterfronts.

We also underline the One Health dimension. Apulia is a densely inhabited coastal/industrial region where humans, ecosystems, and industrial pressures overlap in a relatively small spatial scale. Chronic exposure to

,

, and

is linked to respiratory and cardiovascular outcomes and, as emerging evidence suggests, to neurodegenerative processes [

2,

3,

4]. Surface

, especially during warm-season peaks, exacerbates respiratory stress and can impair lung function. By reconstructing pollutant fields at 300 m resolution, including near schools, hospitals, and residential areas adjacent to industrial/port infrastructure, our model can directly support exposure analysis in a One Health framework, i.e. considering human health, environmental quality, and industrial/economic sustainability together.

Limitations remain. The ARPA network in Apulia, while compliant with regulations, is relatively sparse outside the main urban and industrial centers, which can introduce spatial bias and limit the model’s ability to learn fine-scale patterns in rural areas.

remains challenging because satellite tropospheric

columns integrate the entire free troposphere and are only indirectly sensitive to boundary-layer concentrations; this physical mismatch reduces temporal transferability. Interannual regime shifts in meteorology and emissions also reduce LOYO performance, especially at daily resolution. Future work should incorporate additional dynamical predictors (e.g. planetary boundary layer height, stagnation/recirculation metrics), explore hybrid physics–ML approaches that blend WRF/CTM outputs with data-driven learning [

15,

16], and include explicit uncertainty quantification to flag low-confidence conditions. We also expect that forthcoming missions such as NASA’s MAIA, designed to provide high-resolution particulate information, will further improve

/

estimation and interpretation.

Despite these challenges, our framework already demonstrates that high-resolution (300 m), explainable daily exposure maps for , , , and are feasible in a coastal industrial Mediterranean region. This is particularly relevant for One Health studies and environmental justice assessments in Bari, Taranto, and similar urban–industrial corridors, where both industrial plumes and traffic emissions matter and where vulnerable populations live close to sources.

5. Conclusions

In this work we developed an explainable machine learning framework to estimate daily surface concentrations of four key air pollutants (, , , ) across the Apulia region at 300 m resolution for the period 2019–2022. The model integrates Sentinel-5P column products, a calibrated multi-source AOD field, high-resolution meteorology from WRF, land-use and anthropogenic indicators (roads, buildings, industrial fabric, population), and temporal harmonics. We assessed predictive skill using both repeated random cross-validation and a Leave-One-Year-Out (LOYO) temporal validation scheme.

Random CV yielded high values (0.64–0.78 depending on pollutant), confirming that tree-based fusion (XGBoost) captures non-linear interactions between satellite, meteorological, and land-use drivers that linear models cannot. LOYO daily performance dropped, especially for and , reflecting interannual variability in atmospheric conditions and emissions. Crucially, however, after aggregation to monthly and annual means, the for , , , and partially also remained high (often ), indicating that our maps are reliable for long-term exposure assessment at epidemiologically relevant time scales.

deserves special mention. Although achieved in random CV, its in LOYO daily prediction was lower (), highlighting limited temporal transferability. This is consistent with the known physical mismatch between satellite tropospheric ozone columns and near-surface ozone, and with the strong dependence of ozone on photochemistry, boundary-layer dynamics, and titration. Nevertheless, SHAP analysis shows that the model uses physically interpretable drivers (temperature, emissivity, wind, column ) to reproduce seasonality and warm-season peaks. This suggests that even ozone, which is traditionally difficult to downscale from satellite alone, can be partially constrained by a non-linear, explainable fusion framework.

From an application perspective, the generated maps resolve intra-urban gradients in Bari and Taranto, distinguishing traffic-related exposure from industrial/harbor-related loads. This level of spatial detail is directly relevant for health impact assessment, environmental monitoring, and targeted mitigation strategies in sensitive neighborhoods. The methodology therefore supports the goals of the 2024 EU Air Quality Directive, which encourages improved assessment (as opposed to simply multiplying monitoring stations) and aligns with future satellite missions such as NASA’s MAIA, which will provide high-resolution particulate measurements and is expected to further strengthen particulate matter estimation.

In summary, we provide what is, to our knowledge, the first daily, 300 m resolution, explainable AI-based air pollution product for Apulia, integrating satellite, meteorology, land-use and population indicators. The framework is transferable to other Mediterranean and coastal industrial regions with sparse monitoring networks, and sets the stage for One Health and policy-relevant exposure studies focused on both chronic and acute pollution burdens.

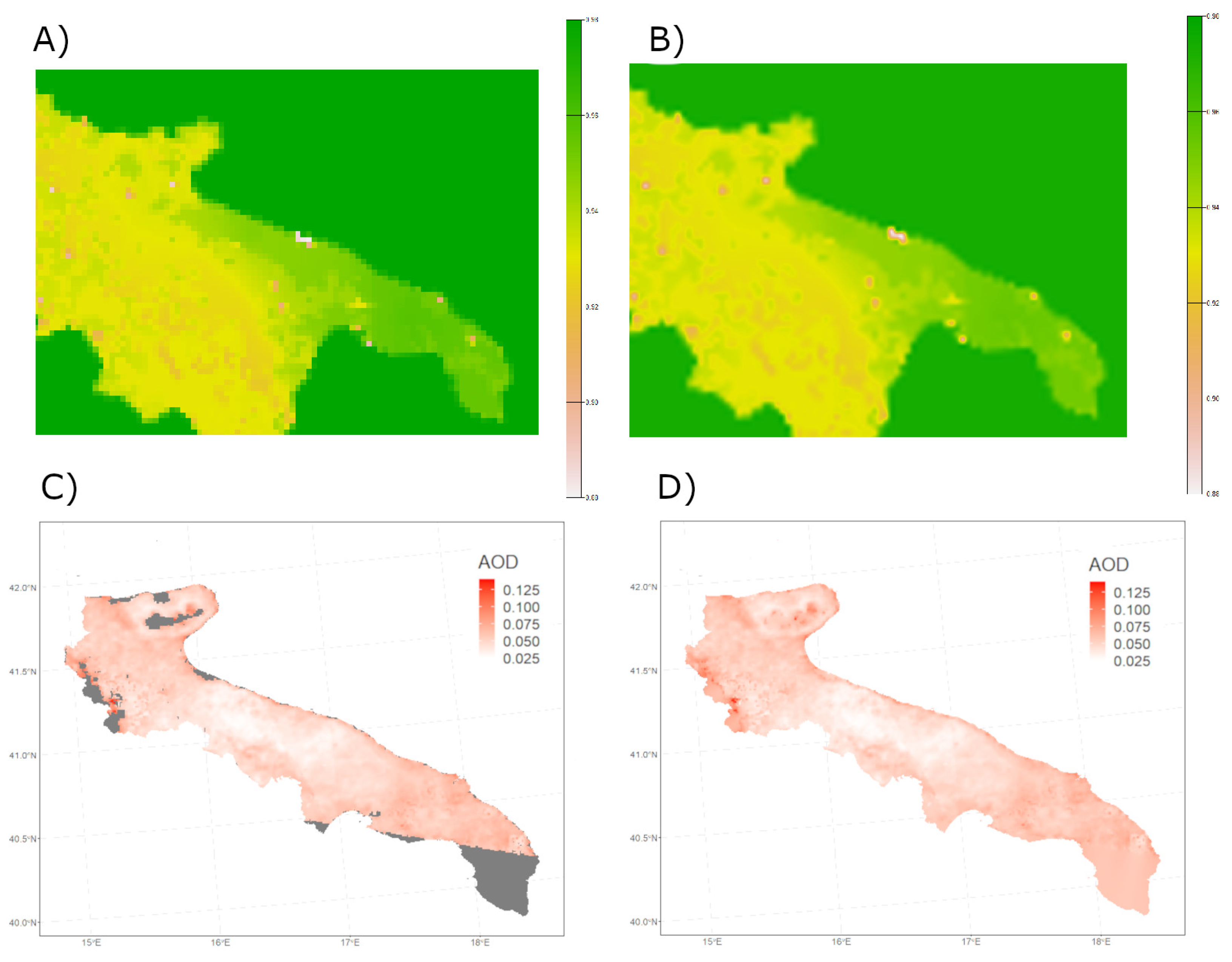

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the analysis. After the collection of satellite, WRF and OpenStreetMap data and a spatial preprocessing phase, we implemented a Machine Learning model to predict ground-level daily air pollution over all Apulian region. Afterwards, we applied a XAI feature importance procedure to understand the role of each feature in the prediction.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the analysis. After the collection of satellite, WRF and OpenStreetMap data and a spatial preprocessing phase, we implemented a Machine Learning model to predict ground-level daily air pollution over all Apulian region. Afterwards, we applied a XAI feature importance procedure to understand the role of each feature in the prediction.

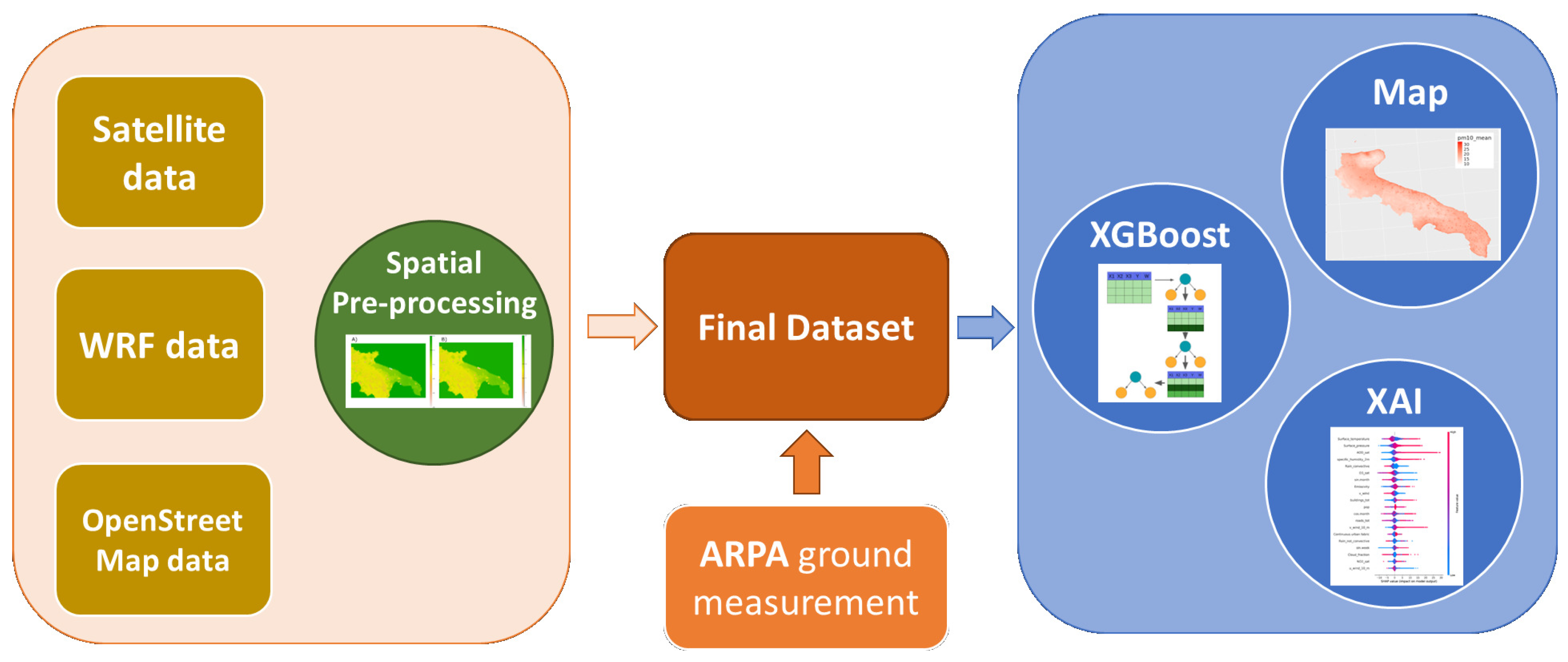

Figure 2.

Map of all ARPA control units (red dots) located in the Apulian Region.

Figure 2.

Map of all ARPA control units (red dots) located in the Apulian Region.

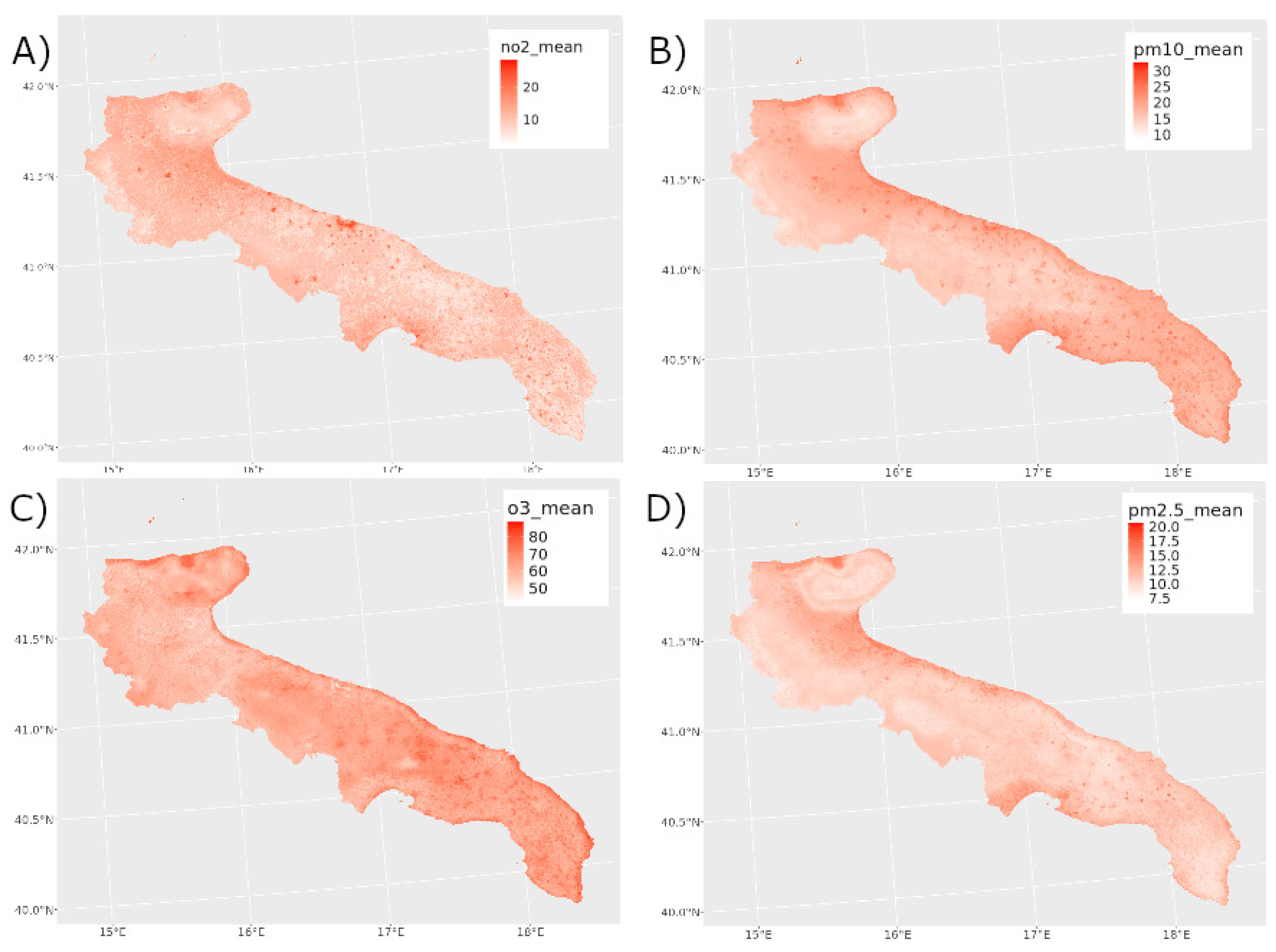

Figure 4.

Predicted map of mean (top left, panel A), (top right, panel B), (bottom left, panel C), and (bottom right, panel D), using the XGBoost model.

Figure 4.

Predicted map of mean (top left, panel A), (top right, panel B), (bottom left, panel C), and (bottom right, panel D), using the XGBoost model.

Figure 5.

SHAP values distribution for the prediction of (top left, panel A), (top right, panel B), (bottom left, panel C) and (bottom right, panel D) concentrations, obtained in cross validation.

Figure 5.

SHAP values distribution for the prediction of (top left, panel A), (top right, panel B), (bottom left, panel C) and (bottom right, panel D) concentrations, obtained in cross validation.

Figure 6.

Left panel (panel A) time series of mean true and predicted values of concentration (), on the right panel (panel B) the mean true and predicted values of concentration.

Figure 6.

Left panel (panel A) time series of mean true and predicted values of concentration (), on the right panel (panel B) the mean true and predicted values of concentration.

Figure 7.

Top left panel (panel A) and bottom left (panel C) map of mean and predicted in the area of Bari. On the right, map of mean (top, panel B) and (bottom, panel D) in the area of Taranto. All prediction are made with the XGBoost model.

Figure 7.

Top left panel (panel A) and bottom left (panel C) map of mean and predicted in the area of Bari. On the right, map of mean (top, panel B) and (bottom, panel D) in the area of Taranto. All prediction are made with the XGBoost model.

Figure 8.

Comparison of distribution (left, expressed in ) measured by Sentinel 5-P and distribution (right, expressed in ) predicted by our model. On the bottom, Boxplot of concentration (expressed in ) from ARPA measurement in the areas of Bari (left) and Taranto (right).

Figure 8.

Comparison of distribution (left, expressed in ) measured by Sentinel 5-P and distribution (right, expressed in ) predicted by our model. On the bottom, Boxplot of concentration (expressed in ) from ARPA measurement in the areas of Bari (left) and Taranto (right).

Table 1.

List of all variables used to build the AI model. The Date and cell_id are used only to merge and aggregate data.

Table 1.

List of all variables used to build the AI model. The Date and cell_id are used only to merge and aggregate data.

| Name |

Source / Product |

Spatio–temporal resolution |

| U_wind_component |

WRF |

, hourly |

| V_wind_component |

WRF |

, hourly |

| Wind_speed |

Computed (from WRF) |

, hourly |

| Emissivity |

WRF |

, hourly |

| Rain_convective |

WRF |

, hourly |

| Rain_non_convective |

WRF |

, hourly |

| Vertical_wind |

WRF |

, hourly |

| Specific_humidity_2m |

WRF |

, hourly |

| Surface_temperature |

WRF |

, hourly |

| Cloud_fraction |

WRF |

, hourly |

| Surface_pressure |

WRF |

, hourly |

| AOD |

Computed |

, daily |

| NO2_sat |

S5P (TROPOMI) |

, daily |

| O3_sat |

S5P (TROPOMI) |

, daily |

|

Sin_month, Cos_month

|

Computed |

daily |

|

Sin_week, Cos_week

|

Computed |

daily |

| Population |

WorldPop |

(static) |

| Roads_tot |

OSM |

(static) |

| Buildings_tot |

OSM |

(static) |

| CORINE classes |

CORINE |

(static) |

| Continuous urban fabric |

CORINE |

(static) |

| Discontinuous urban fabric |

CORINE |

(static) |

| Cell_id |

Computed |

(grid) |

| Date acquired |

Metadata |

daily |

Table 2.

WRF model domain and run configuration used in this study.

Table 2.

WRF model domain and run configuration used in this study.

| Item |

Description |

| Model version |

WRF (operational setup used by ARPA Puglia) |

| Domain extent |

Apulia region (39.61°–42.41° N; 14.38°–18.97° E) |

| Horizontal resolution |

4 km |

| Temporal resolution |

Hourly output |

| Simulation period |

31 Dec 2018, 12:00 UTC – 3 Jan 2023, 00:00 UTC |

| Run length |

181 h per forecast cycle |

| Spin-up removal |

First 12 h of each cycle discarded |

| Lateral/initial forcing |

ECMWF analysis (0.16°C; 6-hourly) |

| Land cover dataset |

CORINE Land Cover |

| Output variables |

3D atmospheric state (U, V, W, T, water species); |

| |

surface fields (PSFC, T2, U10, V10, PBLH, radiation fluxes, precipitation); |

| |

soil variables (soil temperature, soil moisture, runoff) |

| Post-processing for this work |

Hourly → daily aggregation; vertical averaging of selected variables (e.g. vertical wind) to reduce redundancy; resampling to 300 m grid via cubic interpolation (Section 2.3.1); projection to the study CRS |

Table 3.

WRF physical parameterizations adopted in this work. The right column reports the corresponding namelist.input options.

Table 3.

WRF physical parameterizations adopted in this work. The right column reports the corresponding namelist.input options.

| Process |

Scheme |

WRF option |

| Microphysics |

Thompson |

mp_physics = 8 |

| Longwave radiation |

RRTM |

ra_lw_physics = 1 |

| Shortwave radiation |

Dudhia |

ra_sw_physics = 1 |

| Planetary Boundary Layer (PBL) |

YSU |

bl_pbl_physics = 1 |

| Surface layer |

Monin–Obukhov |

sf_sfclay_physics = 1 |

| Land surface model |

Noah LSM |

sf_surface_physics = 2 |

| Cumulus parameterization |

Kain–Fritsch |

cu_physics = 1 |

Table 4.

Random cross-validation (5-fold, repeated 10 times). Metrics are mean ± SD across repeats. MAE and RMSE in . All p-values are significant at the 1% level.

Table 4.

Random cross-validation (5-fold, repeated 10 times). Metrics are mean ± SD across repeats. MAE and RMSE in . All p-values are significant at the 1% level.

| |

|

MAE |

RMSE |

|

| |

|

() |

() |

|

| Linear model |

| |

NO2

|

|

|

|

| |

O3

|

|

|

|

| |

PM2.5

|

|

|

|

| |

PM10

|

|

|

|

| XGBoost |

| |

NO2

|

|

|

|

| |

O3

|

|

|

|

| |

PM2.5

|

|

|

|

| |

PM10

|

|

|

|

Table 5.

Leave-One-Year-Out (LOYO) cross-validation for the XGBoost model. Metrics are mean ± SD across LOYO folds. MAE and RMSE in . Predictions are evaluated at daily scale and after aggregation to monthly and annual means. All p-values are significant at the 1% level.

Table 5.

Leave-One-Year-Out (LOYO) cross-validation for the XGBoost model. Metrics are mean ± SD across LOYO folds. MAE and RMSE in . Predictions are evaluated at daily scale and after aggregation to monthly and annual means. All p-values are significant at the 1% level.

| |

|

MAE |

RMSE |

|

| |

|

() |

() |

|

| Day prediction |

| |

NO2

|

|

|

|

| |

O3

|

|

|

|

| |

PM2.5

|

|

|

|

| |

PM10

|

|

|

|

| Month prediction |

| |

NO2

|

|

|

|

| |

O3

|

|

|

|

| |

PM2.5

|

|

|

|

| |

PM10

|

|

|

|

| Year prediction |

| |

NO2

|

|

|

|

| |

O3

|

|

|

|

| |

PM2.5

|

|

|

|

| |

PM10

|

|

|

|