1. Introduction

Quantitative analysis of human movement is a cornerstone of modern sports science, providing critical insights for performance enhancement and injury prevention. In net sports such as tennis, the precise measurement of three-dimensional (3D) kinematics—including joint angles, segment velocities, and spatial positioning—is essential for coaches and scientists to understand and optimize complex motor skills. For decades, Optical Motion Capture (OMC) systems have been accepted as a “gold standard” for this purpose, offering unparalleled accuracy in controlled laboratory environments (Bartlett 2007).

However, the high cost, operational complexity, and environmental constraints of OMC systems create a significant “lab-to-field” gap. The data captured in a sterile lab setting often fails to represent the variable and dynamic conditions of on-court performance, limiting the ecological validity and practical applicability of the findings for coaches and athletes (Hughes, Arapakis, and McNeill 2019). Factors such as marker slippage during high-intensity movements, the psychological effect of being in a lab environment, and the inability to capture data during actual competition scenarios are well-known limitations. This gap highlights a pressing need for accessible, portable, and cost-effective motion analysis tools that can be deployed “in the wild” without encumbering the athlete or disrupting the natural training/competition environment.

Marker-less motion capture systems, particularly those using a single, readily available video camera (monocular systems), present a promising solution to bridge this gap. The advent of deep learning, particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), revolutionized the field by enabling robust 2D key point detection from images, with systems such as OpenPose have become widely adopted (Cao et al. 2017) in coaching and training environment.

More recently, the Transformer architecture, which has shown remarkable success by modeling global context through self-attention mechanisms (Vaswani et al. 2017). it has been adapted for computer vision tasks. This study focused on validating Capture4D, a novel monocular motion capture system that leverages a powerful Transformer-based architecture, similar in principle to pioneering works like 4DHumans (Goel et al. 2023). Unlike traditional CNNs, this architecture is specifically designed to better model the holistic relationship among all body segments simultaneously, offering the potential for more robust 3D pose estimation, even during complex and rapid athletic movements in competitions.

The purpose of this research was to conduct a rigorous validation of the Capture4D system for 3D kinematic analysis across a comprehensive tennis strokes. This paper presents the detailed validation for the serve, which represents a particularly challenging use-case due to its high velocity and complexity. To our best knowledge, this study could the first to systematically validate a Transformer-based monocular motion capture system for on-court tennis stroke analysis. It provided a practical and accessible solution to bridge the lab-to-field gap in sport analysis for coaches, teachers, and athletes. Our objective was to determine if Capture4D could provide an acceptable level of accuracy in coaching/teaching and biomechanical research. It could offer a practical and accessible alternative to fill the gap between traditional laboratory-based and on court environment evaluation. We hypothesized that Capture4D would achieve sufficient accuracy in joint kinematics to enable in-field coaching/teaching applications, with temporal agreement comparable to gold-standard OMC systems.

2. Methods

2.1. The Capture4D System: Core Architecture and Training

Capture4D, is a markerless monocular human motion capture system based on a Transformer deep learning architecture. Its primary objective is to reconstruct temporally coherent 3D human pose and shape from 2D video recorded by a single, standard camera.

2.1.1. Model Architecture

The technical core of the system is a fully “Transformerized” neural network, which includes a Vision Transformer (ViT) encoder and a cross-attention-based Transformer decoder:

1. ViT Encoder: The system employs a powerful ViT-H/16 model as its image encoder. For each input video frame, the encoder first decomposes it into a series of image patches and then extracts image features representing global contextual information through its multi-layer self-attention mechanism. This enables the model to effectively capture long-range spatial dependencies among different body parts, which is crucial for handling complex poses and severe occlusions.

2. Transformer Decoder: The image features extracted by the encoder are fed into a 6-layer decoder. The decoder interacts with the image features via a cross-attention mechanism, using a learnable query that represents the human model. It ultimately regresses a set of SMPL (Skinned Multi-Person Linear Model) parameters, including pose parameters (θ) defining body posture, shape parameters (β) defining height and build, and camera parameters (π) relative to the person.

2.1.2. Training Data

To ensure robustness and generalization in real-world scenarios, Capture4D’s training process utilizes a large-scale, diverse hybrid dataset strategy. This includes: (1) datasets with precise 3D ground truth, such as Human3.6M (Ionescu et al. 2013) and MPI-INF-3DHP (Mehta et al. 2017), for learning accurate 3D human structure; and (2) large-scale “in-the-wild” image datasets with only 2D annotations, such as COCO (Lin et al. 2014), AI Challenger (Wu et al. 2017), and InstaVariety (Kanazawa et al. 2019), to enhance the model’s recognition capabilities under complex backgrounds, lighting, and clothing conditions.

2.2. Experimental Validation: Participants and Protocol

2.2.1. Participants

Nine (N=9) high-level tennis players were recruited for this study. All participants were right-handed, with an average of 12 years of professional training experience (training duration: 12±3 years, where "±3 years" represents the standard deviation), indicating a solid and systematic professional training background. Given the scarcity of the high-level professional tennis player population and the high demand for data quality, similar as this type of studies in the literature, the sample size of 9 is practically feasible and scientifically reasonable[3.1]. Prior to data collection, all participants were fully informed of the experimental procedures and objectives and provided written informed consents. This study protocol was approved on 9 October 2025, by the Beijing Sport University Institutional Review Board (BSU IRB) with CIRBID 2025426H.

2.2.2. Apparatus and Protocol

Since the OMC cannot be set up outdoors, to compare the two systems, this study was conducted indoors in an open room of approximately 10 meters by 10 meters with a flat, non-slip floor. The experimental environment was set up with sufficient, uniform lighting and a simple background.

The following equipment was used:

1. Monocular Camera: Used to record the participants’ motion videos as input for the Capture4D system.

2. Optical Motion Capture (OMC) System: A Qualisys system was used as the “gold standard” for data collection to validate the accuracy of the Capture4D system. The OMC system includes high-speed cameras and is equipped with professional capture and data processing software.

3. Reflective Markers: Used by the OMC system to capture human motion information. Markers were placed on key anatomical landmarks, such as the head, shoulders, elbows, wrists, hips, knees, and ankles.

4. Data Acquisition Computer: Used to store and process experimental data, configured to meet the operational requirements of both the monocular camera and the OMC system.

5. Sports Equipment: A tennis racket was used to assist participants in completing the specified actions.

During the data collection phase, participants performed tennis serves.

2.3. Experimental Validation: Data Processing and Analysis

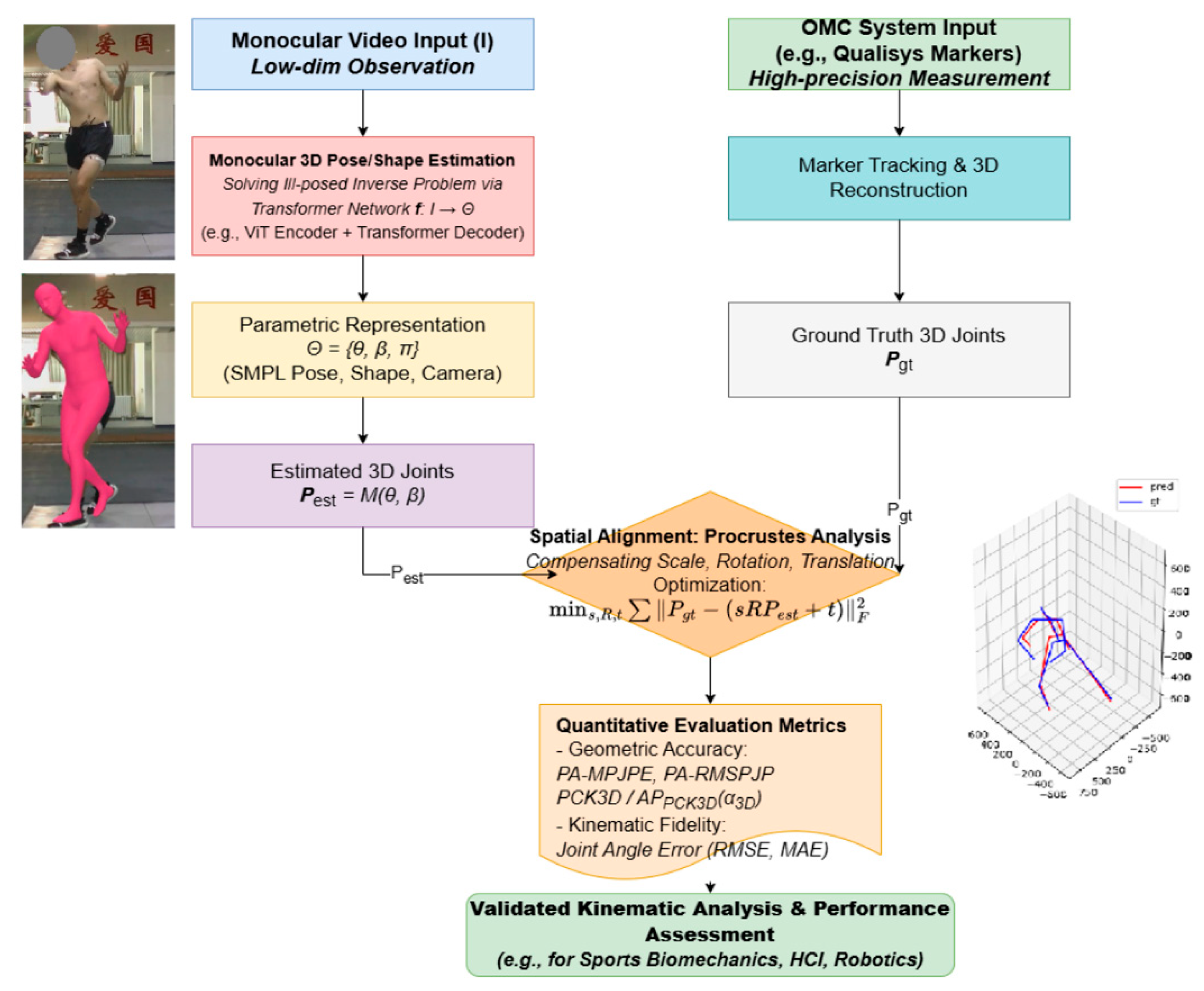

The data analysis workflow was designed to achieve two core objectives: (1) to quantitatively validate the overall 3D reconstruction accuracy of the Capture4D system; and (2) to evaluate its effectiveness in analyzing key biomechanical events in practical sports science applications.

1. Data Preprocessing: The raw 3D coordinate data exported from both systems were first temporally synchronized. To reduce the impact of high-frequency noise on kinematic calculations, a Savitzky-Golay smoothing filter was applied to the joint trajectories output by the Capture4D system.

2. Overall Accuracy Validation: To quantify the overall 3D reconstruction accuracy of the Capture4D system, we used the Normalized Mean Per Joint Position Error (NMPJPE) as the primary metric. This method involves aligning the Capture4D-predicted skeleton of each frame with the gold-standard skeleton measured by the Qualisys system through a rigid transformation (rotation, translation, and scaling) via Procrustes analysis. The average Euclidean distance between all corresponding joints is then calculated. This method eliminates systematic errors arising from different coordinate system definitions and scale differences, thereby enabling a fair assessment of the model’s intrinsic accuracy.

3. Applied Biomechanical Analysis: A core component of our validation was the development of a universal analysis framework applicable to all captured movements. We segmented each of the twelve stroke types into five biomechanically significant key phases (K0-Preparation,K1-Backswing start, K2-Peak of Backswing, K3-Contact Point, K4-Follow-through and K5-Recovery). The identification of these keyframes was based on kinematic criteria derived from the motion data itself, ensuring an objective and reproducible segmentation of the movement. The phases are defined as follows:

The entire data processing and analysis pipeline, summarized in

Figure 1, was implemented using the Python programming language, in conjunction with scientific computing and visualization libraries such as Pandas, NumPy, joblib, and Matplotlib.

3. Results

3.1. Overall System Accuracy

The overall accuracy of the Capture4D system was first evaluated against the gold-standard OMC system across all captured tennis serve trials. As shown in

Table 1, the Normalized Mean Per Joint Position Error (NMPJPE) ranged from 69.5 mm to 88.3 mm. These values fall well within the acceptable error margins (typically 70-130 mm) for applied biomechanical analysis, confirming the system’s foundational validity.

3.2. Kinematic Trajectory and Phase Analysis

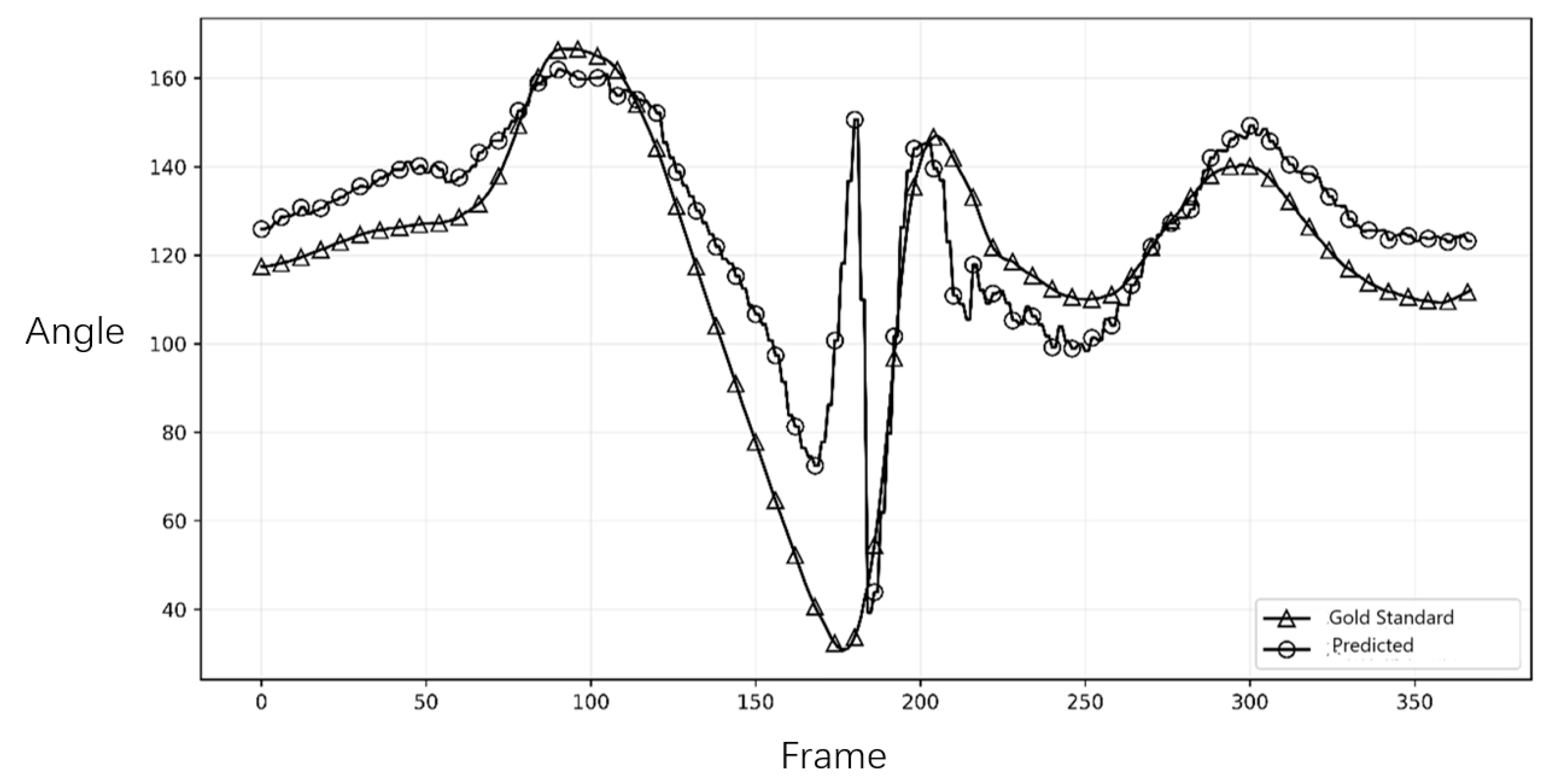

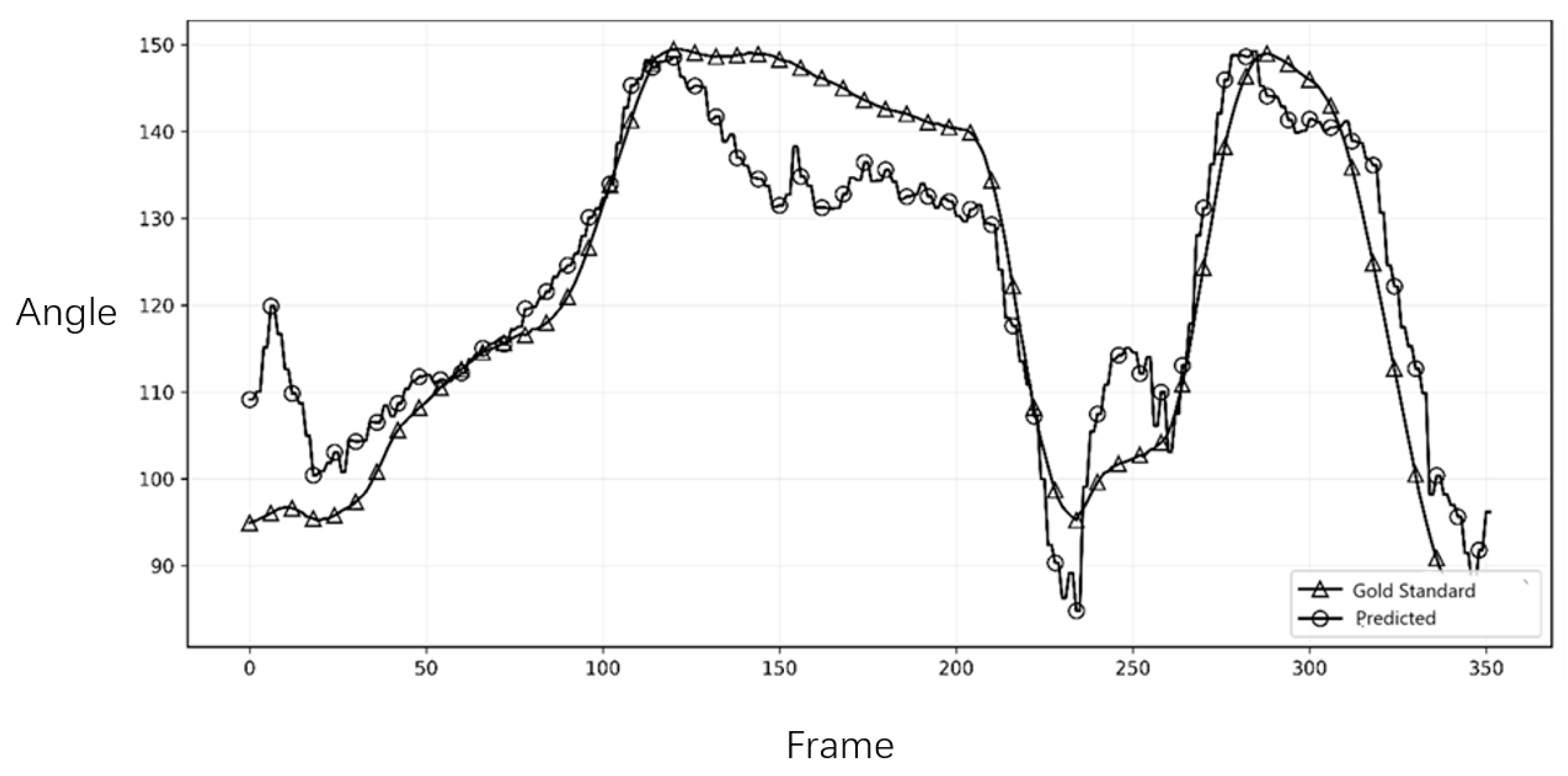

To assess the system’s ability to capture the dynamic characteristics of the tennis serve, we compared the joint angle trajectories over time.

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 illustrate the comparison for the right and left elbow joint from representative trials. The plots demonstrate a high degree of temporal agreement between Capture4D (predicted) and the OMC system (gold standard), with both systems capturing the key kinematic events, peaks, and troughs with minimal phase lag. This indicates that Capture4D can reliably track the temporal dynamics of complex, high-speed movements.

To further evaluate the system’s practical utility for coaching, we developed a comprehensive analysis framework breaking down twelve common tennis strokes (including forehand, backhand, volley, and serve, as detailed in our supplementary analysis file) into biomechanically significant phases. The serve, as an example, was segmented into five key phases, as defined in

Table 2, to allow for a targeted analysis relevant to coaching.

3.3. Error Distribution Analysis and Biomechanical Interpretation

While the overall trajectory alignment in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 demonstrates high temporal consistency, a detailed phase-specific inspection reveals notable deviations in absolute joint angles during specific high-velocity phases. Specifically, the discrepancy observed in the right elbow flexion (

Figure 2) peaks during the transition from the "Trophy Pose" to the "Racket Drop" (late K1 to K2). This phenomenon can be attributed to the inherent depth ambiguity of monocular 3D reconstruction. In this phase, the athlete’s arm moves rapidly behind the torso, leading to significant self-occlusion where the limb is partially invisible to the single camera view.

Although the Transformer-based architecture of Capture4D—similar to the mechanisms described in advanced human mesh recovery systems (e.g., HMR 2.0)—leverages global attention to infer occluded body parts from context, the lack of direct depth information inevitably introduces uncertainty. When the forearm aligns parallel to the camera’s optical axis (foreshortening), the system must rely on learned priors rather than geometric triangulation, resulting in the observed variance in the predicted angle magnitude.

However, from a coaching and pedagogical perspective, these absolute positional errors are secondary to kinematic fidelity. Crucially, the system accurately captures the timing of the peak flexion and the subsequent extension velocity. As shown in the plots, the phase shifts (temporal lag) between the predicted and gold-standard curves are negligible. This confirms that Capture4D effectively preserves the kinetic chain sequencing—such as the critical synchronization between hip rotation and arm extension—which is the primary focus in technical diagnosis. Therefore, despite the presence of systematic estimation errors due to occlusion, the system remains a valid tool for identifying technical flaws and monitoring movement patterns in real-world training scenarios

3.4. Visual and Positional Fidelity

Finally, to provide a qualitative assessment of the system’s reconstruction fidelity,

Figure 4 presents a visual comparison of the 3D poses at critical keyframes of the serve: K0 (Preparation), K1 (Backswing Start), K2 (Peak Backswing), K3 (Contact), K4 (Follow-through peak), and K5 (Recovery). The visual alignment confirms that Capture4D accurately captures the overall body posture and limb configuration throughout the movement, providing an intuitive and correct representation of the athlete’s technique.

4. Discussion

This study shows the acceptable validity of the Capture4D system, a Transformer-based monocular motion capture tool, for the biomechanical analysis using tennis serve in the data collection protocal. Our results indicate that while the system’s absolute positional accuracy (NMPJPE) is slightly lower than the gold-standard OMC, its ability to accurately track kinematic trajectories and quantify key kinematic events makes it a powerful and practical tool for sports science applications.

Notably, the system’s single-camera setup, portability, and cost-effectiveness in real training and competition environment, would extend its use beyond tennis. For example, in figure skating, it can track joint kinematics (e.g., hip abduction in axel jumps) during dynamic movements without limiting training space—solving OMC’s lab-only limitation. In other racket sports (badminton, table tennis), it captures high-speed fine movements: wrist snap in badminton smashes or forearm rotation in table tennis top spins, aiding technical optimization.

By validating Capture4D in tennis, this study paves the way for its cross-sport application, expanding the audience to researchers in figure skating, racket sports, and beyond while boosting its citation value as a versatile biomechanical analysis solution.

4.1. Implications for Sports Science and Coaching/Teaching: Bridging the Lab-to-Field Gap

The most significant contribution of this research lies in demonstrating a viable solution to fill the “lab-to-field” gap in sports analysis in coaching and teaching. For decades, coaches and athletes have faced a trade-off: either conduct highly accurate analysis in an artificial, expensive laboratory environment or rely on subjective observation in the ecologically valid but data-poor training field. Capture4D offers a compelling bridge between these two extremes.

It is crucial to interpret the observed error margins within the context of practical coaching. While an average NMPJPE of 75.66 mm represents a positional discrepancy, this level of error is often smaller than the natural variability in an athlete’s movement between repetitions. More importantly, for a coach’s decision-making process, the preservation of kinematic patterns and temporal sequences is paramount. For instance, identifying whether an athlete’s shoulder rotation peak occurs before or after their hip rotation peak is a critical insight that is unaffected by minor absolute positional errors. The feedback for the coaches shows that particularly the high fidelity of the joint angle trajectories (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3), confirm that Capture4D reliably preserves these crucial temporal and relational patterns, making it a robust tool for practical, in-field technical evaluation.

Our findings show that the system provides data with sufficient accuracy to inform coaching decisions. For a coach, the precise absolute 3D position of an athlete’s elbow is often less critical than the pattern and timing of its movement. The high temporal agreement in joint angle trajectories (as seen in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3) confirms that Capture4D can reliably be used to assess an athlete’s kinetic chain sequencing.

Furthermore, the ability to perform a phase-based analysis and extract discrete, coach-centric metrics (

Table 2) is a key advantage. A coach or teacher can use this system to answer critical performance questions directly on the court. For instance, by examining the ‘peak shoulder-hip separation angle’ at K1 and the subsequent ‘peak trunk rotation velocity’ leading into K2, a coach can quantitatively assess the efficiency of an athlete’s core in transferring power from the lower body to the upper limbs. A deficiency in this sequence could lead to specific corrective drills focusing on core stability and rotational power. Similarly, by monitoring the ‘peak shoulder internal rotation velocity’ during the K3 follow-through phase over multiple sessions, a coach could track potential indicators of fatigue or overload on the shoulder joint, which are critical for injury prevention strategies. This transforms quantitative analysis from a retrospective research activity into an immediate, actionable feedback loop that can be integrated into daily training routines. The comprehensive framework we developed for twelve distinct tennis movements, exemplified here by the serve, also underscores the system’s broad potential for holistic, long-term athlete monitoring.

4.2. Contextualizing the Contribution: Accessibility and Cost-Effectiveness

While Optical Motion Capture (OMC) systems remain the undisputed “gold standard” for accuracy in biomechanical research (Bartlett 2007), their practical application in day-to-day coaching/teaching and training very limited. The literature widely acknowledges that the significant financial investment, requirement for dedicated laboratory space, and need for highly trained technical personnel are substantial barriers to the widespread adoption of OMC technology (Hughes, Arapakis, and McNeill 2019). This creates a well-documented “lab-to-field” gap, where the most accurate analysis tools are unavailable in the very environments where athletes actually train and compete.

The primary contribution of this study, therefore, is not to challenge the sub-millimeter precision of OMC systems, but to validate a practical and accessible alternative that directly addresses these long-standing limitations. The goal of democratizing sports science by providing low-cost, easy-to-use tools for quantitative analysis is a significant and active area of research (Camomilla et al. 2018). Our findings demonstrate that Capture4D, with its reliance on only a single standard camera and minimal setup time, represents a significant step toward this goal. By providing data of sufficient quality for kinematic pattern analysis and coaching feedback, it offers a solution that is orders of magnitude more cost-effective and operationally feasible for a vast majority of sports programs, from grassroots to professional levels.

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

Despite the promising results, it is important to acknowledge the system’s limitations. The primary source of error is the inherent depth ambiguity of monocular vision. This is most evident when limbs move parallel to the camera’s image plane or during significant self-occlusion. While the Transformer architecture mitigates this by leveraging global context, high-speed movements can still introduce motion blur, challenging frame-by-frame estimation.

Future research should focus on several key areas. First, further optimization of the Transformer model to specifically improve robustness to high-speed motion and severe occlusion would be beneficial. Second, exploring multi-sensor fusion, for instance by integrating data from a single Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) placed on the athlete, could dramatically improve accuracy with minimal impact on convenience. Finally, developing and validating sport-specific models, fine-tuned on extensive datasets of elite athletes in sports like tennis, golf, or baseball, could further enhance performance and provide even more granular insights for coaches.

5. Conclusion

This study rigorously validated the Capture4D system as an effective and practical tool for the 3D kinematic analysis in tennis. The system provides accuracy within the acceptable range for applied biomechanical research and sport analysis while offering significant advantages in cost, portability, and ease of use over traditional OMC systems. By enabling coaches, teachers and sports scientists to move quantitative analysis out of the laboratory and onto the court, Capture4D represents a significant step towards the democratization of sports motion analysis, empowering a data-informed approach to technique optimization and injury prevention.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, study design and methodology were performed by Yue Zhao, Yuanlong Liu and Zan Gao. Data collection and material preparation were performed by Yixiong Cui and Haijun Wu. Software development, data processing and analysis were performed by Shuo Wang. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Yue Zhao. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Supervision and funding acquisition were performed by Yuanlong Liu.

Funding

This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant number: 2023RHJS002) for the project on ‘Development of a Tennis Visualization System Based on Motion Capture Technology’ and the China Scholarship Council (Fund No. 202406520033).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study protocol was approved by the Beijing Sport University Institutional Review Board (BSU IRB) with CIRBID 2025426H.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conficts of lnterest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Andriluka, Mykhaylo; Pishchulin, Leonid; Gehler, Peter; Schiele, Bernt. 2d human pose estimation: New benchmark and state of the art analysis. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2014; pp. 3686–3693. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, Roger. Introduction to sports biomechanics: Analysing human movement; Routledge, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Camomilla, Valentina; Bergamini, Elena; Fantozzi, Silvia; Vannozzi, Giuseppe. An overview of wearable inertial sensors for human movement analysis. Sensors 2018, 18(3), 768. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Zhe; Simon, Tomas; Wei, Shih-En; Sheikh, Yaser. Realtime multi-person 2d pose estimation using part affinity fields. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017; pp. 7291–7299. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Haobo; Wang, Chun-Chao; Wang, Sen; Zeng, Wendong; Qian, Yin. Cross-view fusion for 3d human pose estimation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.09813. [Google Scholar]

- Colyer, S. L.; Evans, M.; Cosker, D. P.; Salo, A. I. The validity of a deep learning-based 2D-to-3D lifting method for the analysis of tennis serves. Journal of sports sciences 2018, 36(19), 2248–2254. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, Alexey; Beyer, Lucas; Kolesnikov, Alexander; Weissenborn, Dirk; Zhai, Xiaohua; Unterthiner, Thomas; Dehghani, Mostafa; Minderer, Matthias; Heigold, Georg; Gelly, Sylvain. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar]

- Goel, Shubham; Pavlakos, Georgios; Rajasegaran, Jathushan; Kanazawa, Angjoo; Malik, Jitendra. Humans in 4D: Reconstructing and Tracking Humans with Transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023; pp. 9136–9147. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Chunhui; Sun, Chen; Ross, David A; Vondrick, Carl; Pantofaru, Caroline; Li, Yeqing; Vijayanarasimhan, Sudheendra; Toderici, George; Ricco, Susanna; Sukthankar, Rahul. Ava: A video dataset of spatio-temporally localized atomic visual actions. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018; pp. 6047–6056. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, Kevin; Arapakis, Ioannis; McNeill, Alistair. The use of technology in sport: A review of the literature. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching 2019, 14(4-5), 593–613. [Google Scholar]

- Ionescu, Catalin; Papava, Dragos; Olaru, Vlad; Sminchisescu, Cristian. Human3. 6m: Large scale datasets and predictive methods for 3d human sensing in natural environments. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2013, 36(7), 1325–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iskakov, Karim; Burkov, Egor; Lempitsky, Victor; Malkov, Yury. Learnable triangulation of human pose. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.05754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanazawa, Angjoo; Zhang, Jason Y; Felsen, Panna; Malik, Jitendra. Learning 3d human dynamics from video. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2019; pp. 5614–5623. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Shichao; Ke, Lei; Li, Kevin; Zhang, Yudong; Cui, Jiakai; Lee, Kyoung Mu. Cascaded deep monocular 3d human pose estimation with evolutionary training data. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2008.02433. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Tsung-Yi; Maire, Michael; Belongie, Serge; Hays, James; Perona, Pietro; Ramanan, Deva; Dollár, Piotr; Zitnick, C Lawrence. Microsoft coco: Common objects in context. Computer Vision--ECCV 2014: 13th European Conference, Zurich, Switzerland, 2014; Springer; Proceedings, Part V 13, pp. 740–755. [Google Scholar]

- Loper, Matthew; Mahmood, Naureen; Romero, Javier; Pons-Moll, Gerard; Black, Michael J. SMPL: A skinned multi-person linear model. ACM transactions on graphics (TOG) 2015, 34(6), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, Julieta; Hossain, Rayat; Romero, Javier; Little, James J. A simple yet effective baseline for 3d human pose estimation. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1705.03098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, Dushyant; Rhodin, Helge; Casas, Dan; Fua, Pascal; Sotnychenko, Oleksandr; Xu, Weipeng; Theobalt, Christian. Monocular 3d human pose estimation in the wild using improved cnn supervision. 2017 international conference on 3D vision (3DV), 2017; IEEE; pp. 506–516. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, Gyeongsik; Chang, Ju Yong; Lee, Kyoung Mu. Camera distance-aware 3d human pose estimation from a single image. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.11375. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Noguer, Francesc. 3d human pose estimation from a single image. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1705.02883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Hui En; Cai, Zhongang; Yang, Lei; Zhang, Tianwei; Liu, Ziwei. Benchmarking and analyzing 3d human pose and shape estimation beyond algorithms. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 26034–26051. [Google Scholar]

- Pavllo, Dario; Feichtenhofer, Christoph; Grangier, David; Auli, Michael. 3D human pose estimation in video with temporal convolutions and semi-supervised training. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2019; pp. 7753–7762. [Google Scholar]

- Tome, Denis; Russell, Chris; Agapito, Lourdes. Lifting from the deep: Convolutional 3d pose estimation from a single image. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1701.00295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, Ashish; Shazeer, Noam; Parmar, Niki; Uszkoreit, Jakob; Jones, Llion; Gomez, Aidan N; Kaiser, Łukasz; Polosukhin, Illia. Attention is all you need. In Advances in neural information processing systems; 2017; pp. 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Wandt, Bastian; Rosenhahn, Bodo. Canonpose: Self-supervised 3d human pose estimation in the wild. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.11657. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside, David; Elliott, Bruce; Lay, Brendan; Reid, Machar. Biomechanics of the tennis serve: a systematic review. Journal of sports sciences 2016, 34(18), 1767–1781. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Jiahong; Zheng, He; Zhao, Bo; Li, Yixin; Yan, Baoming; Liang, Rui; Wang, Wenjia; Zhou, Shipei; Lin, Guosen; Fu, Yanwei. Ai challenger: A large-scale dataset for going deeper in image understanding. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1711.06475. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Jun; Wang, Mengmeng; Chen, Zhiyong; Luo, Zhongwei; Wei, Xiaohua; Zheng, Yin. A survey on 2d and 3d human pose estimation. Image and Vision Computing 2020, 99, 103921. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Ce; Zhu, Sijie; Mendieta, Matias; Yang, Taojiannan; Chen, Chen; Ding, Zhengming. Poseformer: A transformer-based model for 3d human pose estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2021; pp. 11655–11664. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Xingyi; Huang, Qixing; Sun, Xiao; Xue, Xiangyang; Wei, Yichen. Towards 3d human pose estimation in the wild: a weakly-supervised approach. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.02447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).