1. Introduction

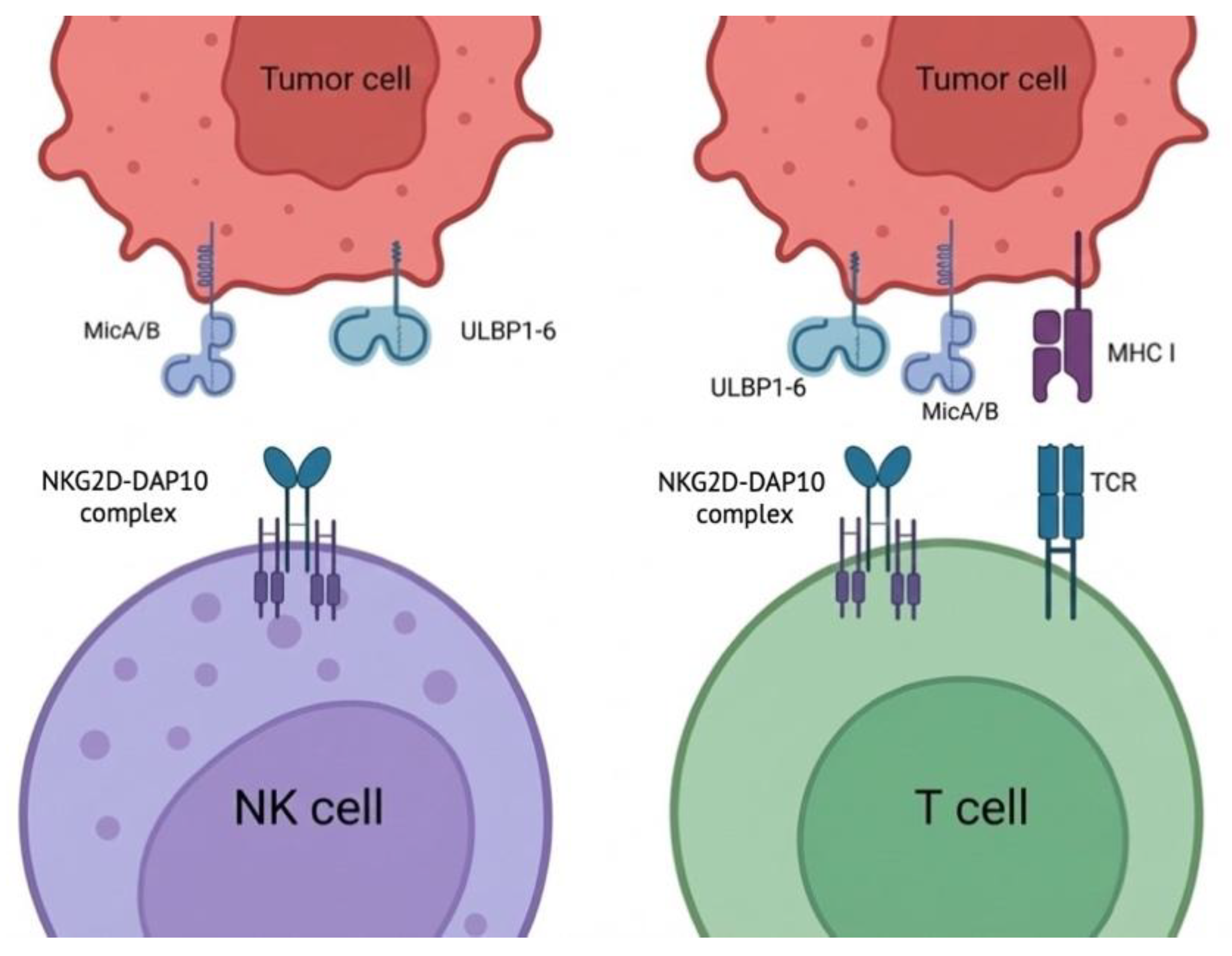

Conventional CAR-T therapies have achieved durable remissions in select hematologic malignancies, yet efficacy in solid tumors remains limited by antigen heterogeneity, impaired trafficking, and an immunosuppressive TME. NKG2D-based CAR-T cells offer a distinct targeting paradigm: instead of a single antigen, they target multiple stress-induced ligands shared across tumor types (

Figure 1). This feature is conceptually attractive for mitigating antigen escape; however, it introduces unique liabilities because NKG2D ligands can be induced dynamically during inflammation and tissue stress.

2. The NKG2D–Ligand Axis: Biology that Defines Both Opportunity and Risk

2.1. NKG2D in NK Cells Versus T Cells (Updated with Figure 1)

NKG2D is constitutively expressed on NK cells and also on subsets of T cells (notably cytotoxic T cells), where its functional role differs by lineage context. In NK cells, NKG2D acts as a potent activating receptor, while in T cells it typically serves as a co-stimulatory receptor cooperating with TCR signaling (

Figure 1). Mechanistically, human NKG2D signals through the DAP10 adaptor, which provides a tyrosine-based motif that recruits PI3K and Grb2-associated signaling nodes (including Vav1), supporting cytoskeletal remodeling and cytotoxic synapse formation.

2.2. Ligand Diversity and Inducible Expression

NKG2D ligands (NKG2DL) include MICA/MICB and the ULBP family (ULBP1–6), which are commonly upregulated by DNA damage responses, oncogenic stress, and inflammatory cues. The multi-ligand nature broadens tumor coverage but complicates target validation because the therapeutic window may narrow when healthy tissues upregulate stress ligands during infection, inflammation, or treatment-related tissue injury.

2.3. Tumor Immune Evasion Through Ligand Shedding and Soluble Decoys

A recurring immune-evasion mechanism is proteolytic shedding of MICA/MICB, which reduces surface ligand density and generates soluble ligands that can impair effector function and promote NKG2D down-modulation. Strategies that inhibit shedding have shown the ability to restore NKG2D-axis antitumor immunity in preclinical models, supporting the view that shedding is not merely correlative but mechanistically consequential.

2.4. TGF-β as a Dominant Suppressor of NKG2D Pathways

TGF-β can downregulate NKG2D expression and suppress NKG2D-mediated tumor immunity across NK and CD8+ T-cell compartments, and this is widely considered a central resistance mechanism in solid tumors. This has direct implications for NKG2D-CAR-T efficacy, as the therapy relies on sustained effector competence under TME cytokine pressure.

3. Engineering NKG2D-CAR-T Cells: Design Implications from Figure 1 Biology

3.1. Recognition Module: “Multi-Ligand Targeting” and Activation Tuning

Most NKG2D-CAR designs use NKG2D as the ligand-binding domain fused to intracellular activation modules (commonly CD3ζ with additional costimulation). Because

Figure 1 highlights the breadth of ligand recognition (MICA/B and ULBP1–6), a key development challenge is activation tuning: increasing sensitivity enough to overcome heterogeneous ligand density without creating unacceptable activity against inflamed normal tissues.

3.2. Addressing Fratricide and Self-Ligand Induction

A specific, practical challenge for NKG2D-ligand CAR approaches is that activated immune cells can transiently express stress ligands, contributing to fratricide and reduced persistence in some settings. Next-generation concepts have explored reducing MICA/MICB expression in the product to support persistence.

3.3. Countering Ligand Shedding and Soluble Ligand Suppression

Given the established role of MICA/MICB shedding and soluble ligand decoys, CAR development and clinical protocols may benefit from incorporating (i) baseline and on-treatment soluble ligand measurements and (ii) combination approaches that reduce shedding or neutralize soluble ligand activity.

3.4. TGF-β Resistance and Armored Designs

Because TGF-β can directly blunt NKG2D-axis function, engineering strategies that confer TGF-β resistance (or combination therapies that reduce TGF-β signaling) are particularly relevant for NKG2D-CAR-T in solid tumors.

3.5. Controllability and Safety Engineering

The inducible nature of stress ligands motivates enhanced control layers such as safety switches and logic-gating—especially for clinical scenarios with high baseline inflammation risk.

4. Translational and Clinical Experience (Representative Programs)

Autologous NKG2D-CAR-T therapy (CYAD-01 / NKR-2) has been evaluated clinically, including in the THINK Phase I study. These data support feasibility and provide a safety/dose framework, while also illustrating field-wide challenges in durability and reproducibility of clinical responses.

Allogeneic NKG2D-based CAR-T programs have also reached clinical testing (e.g., alloSHRINK; CYAD-101), with the trial registration documenting key design and treatment context. Program discontinuations in this space highlight that operational, strategic, and clinical-development constraints can terminate programs even when biology remains compelling.

5. Current Challenges in NKG2D-CAR-T Development (Field-Facing)

Table 1.

Major challenges and representative mitigation strategies (updated to reflect Figure 1 biology).

Table 1.

Major challenges and representative mitigation strategies (updated to reflect Figure 1 biology).

| Challenge |

Mechanism (NKG2D-axis specific) |

Consequence |

Mitigation strategies |

| Inducible stress ligands on normal tissues |

Inflammation/tissue injury induces MICA/B, ULBPs |

Safety risk; variable therapeutic window |

Conservative escalation; inflammation-aware eligibility; controllable CARs; logic gating |

| Ligand heterogeneity & dynamics |

Spatial/temporal variation in surface NKG2DL |

Mixed responses; early relapse |

Multi-site profiling; longitudinal biomarker monitoring; combinations that increase surface ligands |

| Ligand shedding and soluble/vesicular decoys |

ADAM-mediated shedding; soluble MICA/B reduces function and down-modulates NKG2D |

Reduced potency; systemic/local suppression |

Add soluble ligand biomarkers; shedding inhibition/neutralization strategies |

| TGF-β dominance in TME |

Downregulates NKG2D pathways and cytotoxic function |

Low activity in solid tumors |

TGF-β–resistant designs; TGF-β pathway combinations |

| Persistence/exhaustion constraints |

Chronic stimulation + metabolic stress |

Limited durability |

Memory-biased manufacturing; signaling tuning; cytokine/chemokine armoring |

| Development/manufacturing complexity |

Patient variability and cost; allogeneic immunologic constraints |

Program viability risk |

Biomarker-enriched trials; fit-for-purpose potency assays; early go/no-go endpoints |

6. Future Directions

Development priorities that map directly onto the

Figure 1 biology include: (i) standardized quantification of tumor surface NKG2DL and soluble ligands; (ii) rational combinations to stabilize surface ligands and counter shedding; (iii) engineering to resist TGF-β–mediated suppression; and (iv) controllable CAR architectures that protect the therapeutic index in inflammatory clinical contexts.

7. Conclusions

NKG2D-based CAR-T cells provide an inherently multi-ligand targeting strategy (

Figure 1) with the potential to reduce single-antigen escape. However, the same stress-ligand biology that enables breadth also drives key liabilities: inducible expression on stressed tissues, ligand shedding and soluble decoy effects, and potent suppression by TGF-β in the TME. Evidence to date indicates feasibility and manageable safety in early studies, but durable efficacy will likely require biomarker-guided clinical positioning plus next-generation engineering focused on shedding/soluble ligand biology, TGF-β resistance, and controllability.

Funding

This work was funded by the subsidy allocated to Kazan Federal University for the state assignment in the sphere of scientific activities (project number FZSM-2023-0011).

Conflicts of Interest

The author(s) declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Crane, C. A. et al. TGF-downregulates the activating receptor NKG2D on NK cells and CD8+ T cells in glioma patients. Neuro-Oncology 12, 7–13 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Ferrari de Andrade, L. et al. Antibody-mediated inhibition of MICA and MICB shedding promotes NK cell–driven tumor immunity. Science 359, 1537–1542 (2018).

- Xing, S. & Ferrari de Andrade, L. NKG2D and MICA/B shedding: a ‘tag game’ between NK cells and malignant cells. Clinical & Translational Immunology 9, (2020).

- Michaux, A. et al. Clinical Grade Manufacture of CYAD-101, a NKG2D-based, First in Class, Non–Gene-edited Allogeneic CAR T-Cell Therapy. Journal of Immunotherapy 45, 150–161 (2022).

- Sallman, D. A. et al. CYAD-01, an autologous NKG2D-based CAR T-cell therapy, in relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukaemia and myelodysplastic syndromes or multiple myeloma (THINK): haematological cohorts of the dose escalation segment of a phase 1 trial. The Lancet Haematology 10, e191–e202 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Curio, S., Jonsson, G. & Marinović, S. A summary of current NKG2D-based CAR clinical trials. Immunotherapy Advances 1, (2021). [CrossRef]

- Zingoni, A., Vulpis, E., Loconte, L. & Santoni, A. NKG2D Ligand Shedding in Response to Stress: Role of ADAM10. Frontiers in Immunology 11, (2020). [CrossRef]

- Wensveen, F. M., Jelenčić, V. & Polić, B. NKG2D: A Master Regulator of Immune Cell Responsiveness. Frontiers in Immunology 9, (2018). [CrossRef]

- Upshaw, J. L. et al. NKG2D-mediated signaling requires a DAP10-bound Grb2-Vav1 intermediate and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase in human natural killer cells. Nature immunology 7, 524–32 (2006). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).