1. Introduction

Introduction

Wearable continuous monitors technologies are increasingly common in healthcare [

1,

2]. Continuous pulse oximetry would benefit several high risk populations including patients with chronic lung disease, sleep-disordered breathing, and patients with active opioid use [

3,

4,

5]. Conventional pulse oximeters limit use of the hands, but alternate pulse oximeter probe sites range from the forehead to the toes sometimes with smartphone interface [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Motion artifacts in ambulatory patients limit accuracy, potentially resulting in delayed detection of hypoxemia [

1,

11]. Wearable biosensor technologies in the outpatient setting must be designed with user acceptability, device effectiveness, and hold the potential for additional features such as integrated respiratory monitoring [

4,

12,

13].

Studies of shoulder-mounted pulse oximetry technology are limited [

14,

15]. Our group developed a shoulder-mounted device with a high level of acceptability in certain populations [

16]. We sought to investigate the feasibility and acceptability of a shoulder-based pulse oximeter among a convenience cohort undergoing diagnostic polysomnography.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a quantitative and descriptive pilot of two prototype biosensor designs at the Penn Sleep Medicine Diagnostic Program, an outpatient sleep center in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA. The study protocol was approved by the University of Pennsylvania IRB and was performed in compliance with relevant laws and institutional guidelines. Inclusion criteria included clinical suspicion for sleep-disordered breathing and age >21. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy.

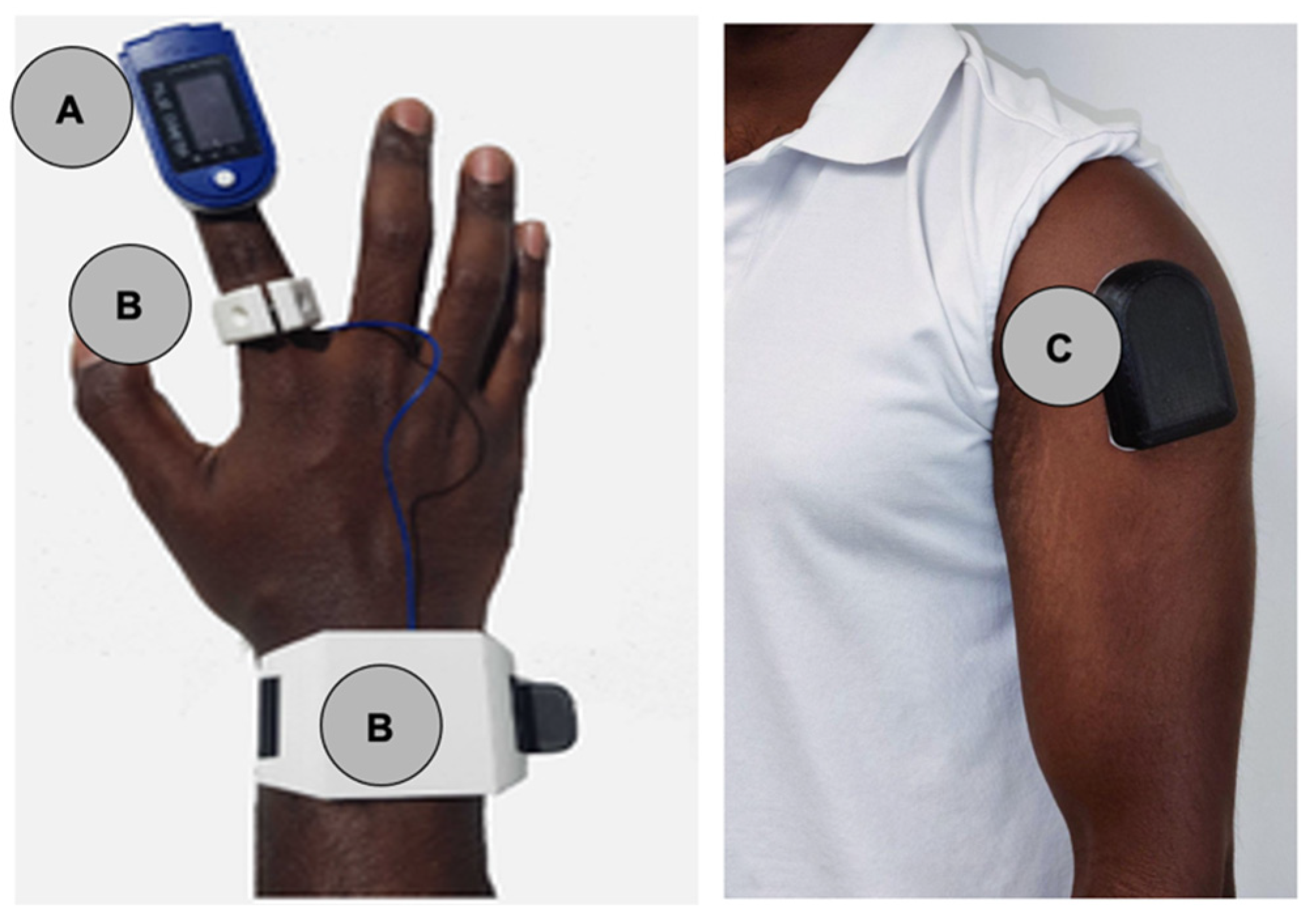

Patients wore a standard pulse oximeter (EMAY EMO-80 Sleep Oxygen Monitor,

Figure 1a) and two prototype biosensors: Prototype-ring (

Figure 1b) and Prototype-shoulder (

Figure 1c). Prototype-ring (

Figure 1b) consisted of a ring worn on the index finger to assess oxygen satu-ration as well as a wristband containing a battery and data storage hardware. Proto-type-shoulder (

Figure 1c) was an adhesive armband worn over the deltoid.

We assessed the prototypes based on FDA guidelines for pulse oximeters [

18]. We trained the model using an 80-20 train-test split on a 5-fold cross validation. We then tested the R2 score, mean absolute error, and standard deviation of the mean absolute error to ensure the model was not overfit (Supplemental Methods). No adjustments were made for known confounders such as skin tone, positioning, or sleep stage. We also evaluated the comfort via a 5-point Likert scale and an open-ended qualitative questionnaire. Independent patient-level variables included demographics and participant BMI. Differences in mean results were assessed with a two-sided t-test with alpha 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Study Participants

Participant demographic information is described in

Table 1. The patients sampled were majority white (57.1%) and male (58.3%). Participants had a median BMI of 28.5 (IQR 26.5 - 35.1). Participant demographics are described in

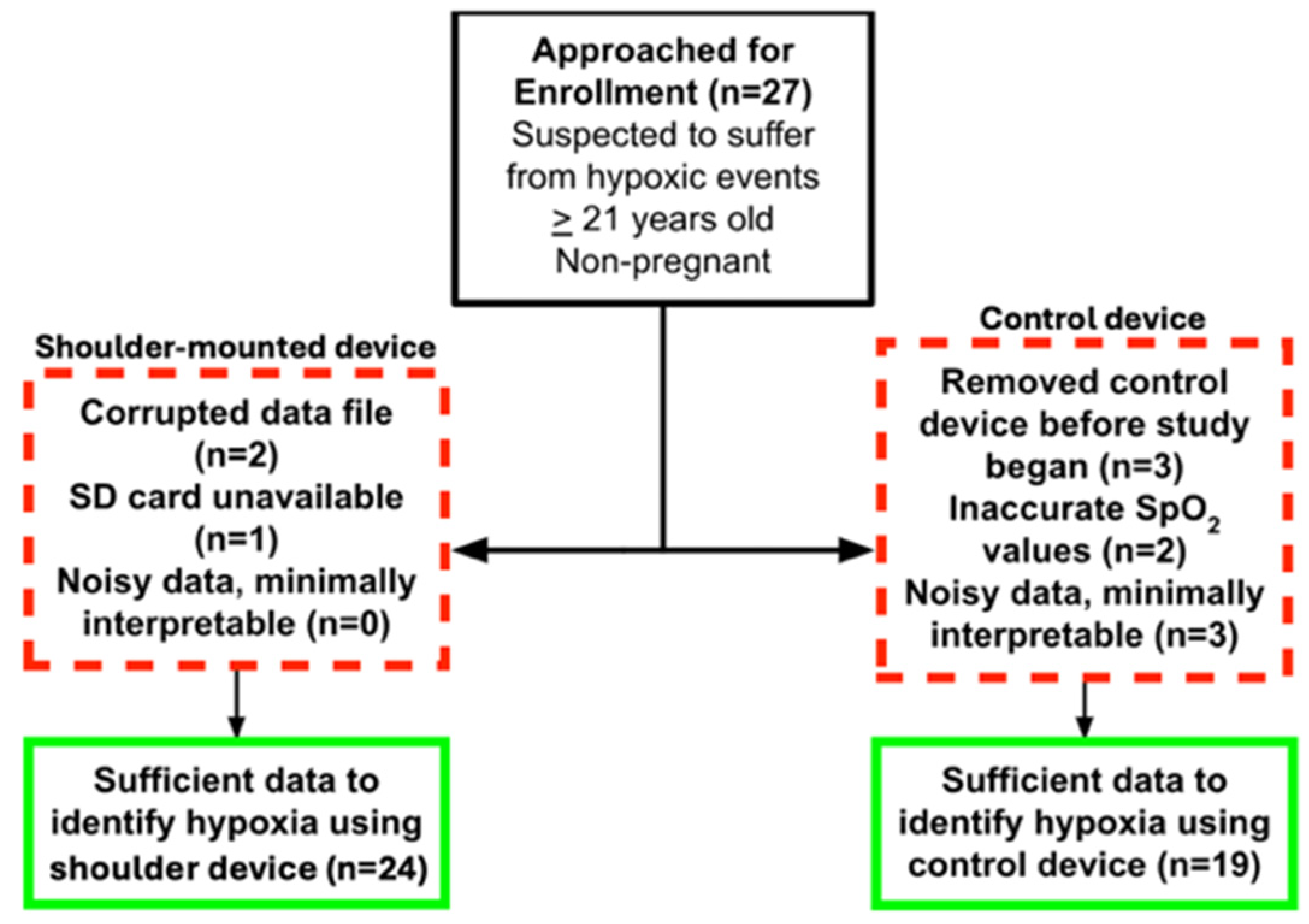

Table 1. The patients sampled were majority white (57.1%) and male (58.3%). Participants had a median BMI of 28.5 (IQR 26.5 - 35.1). A consort diagram is shown in

Figure 2. Data from the shoulder was unusable for 3 patients due to corrupted data files (2) and SD card unavailability (1). The FDA cleared control device had 8 patients with unusable data. All patients with interpretable finger pulse oximetry data had interpretable shoulder-mounted data.

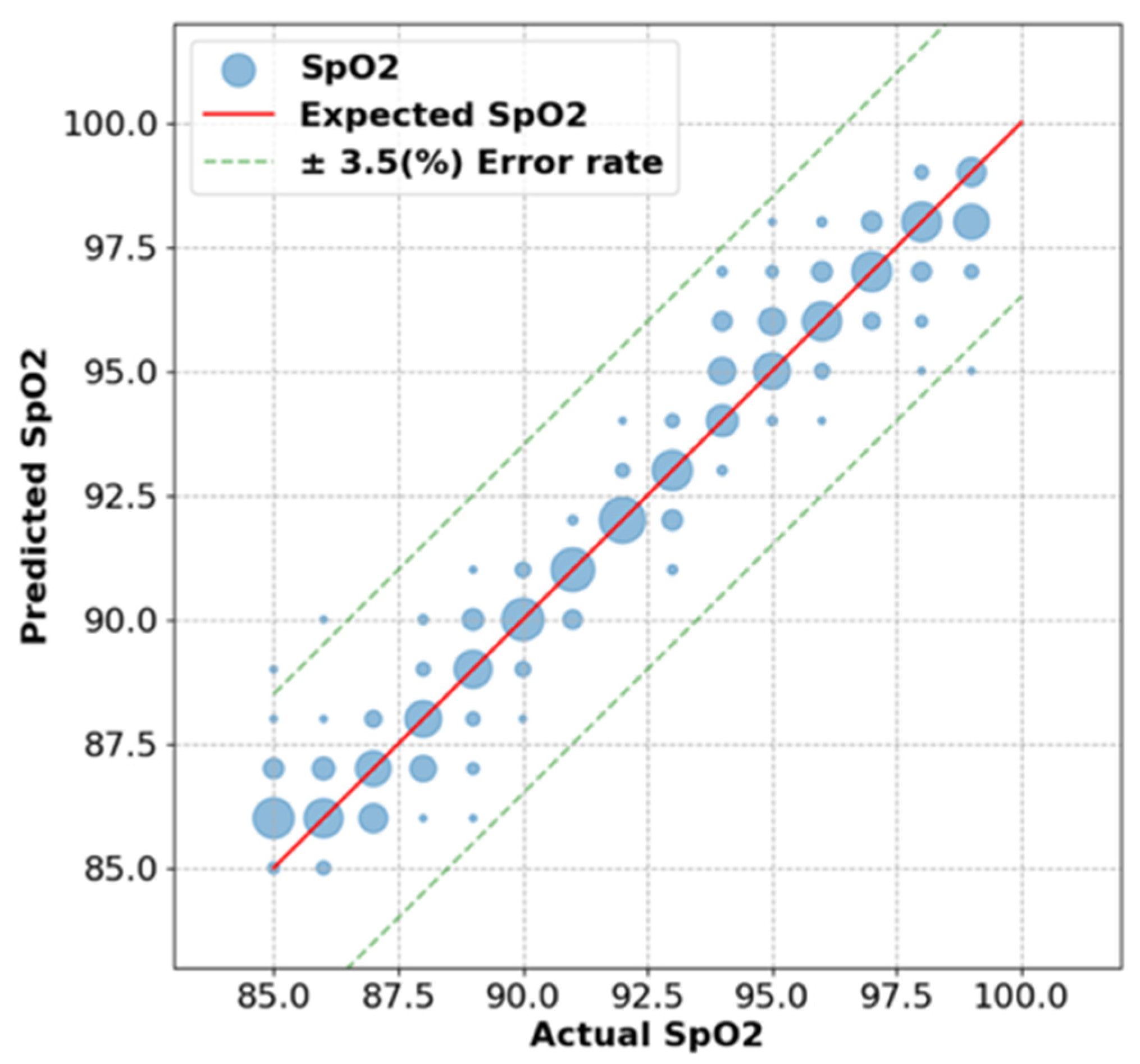

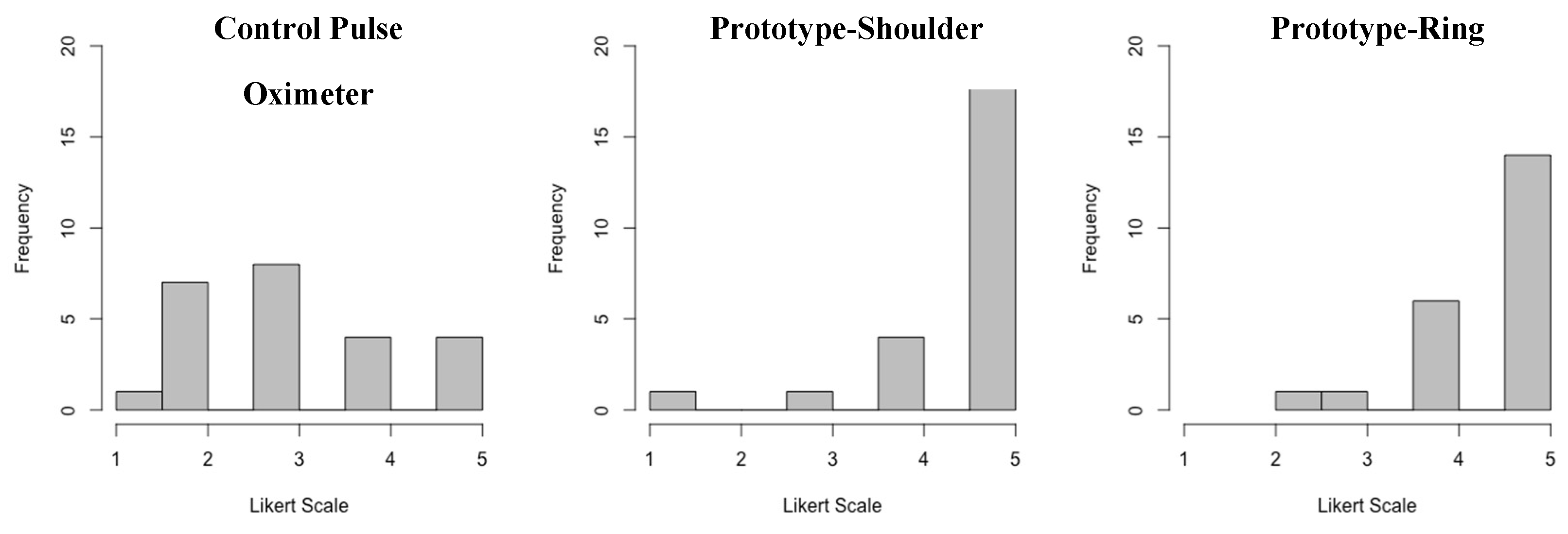

Agreement among the 19 patients with data from both devices is shown in

Figure 3. The Prototype-shoulder pulse oximeter had a 0.72% mean absolute error from the control values of the commercial finger-based pulse oximeter (

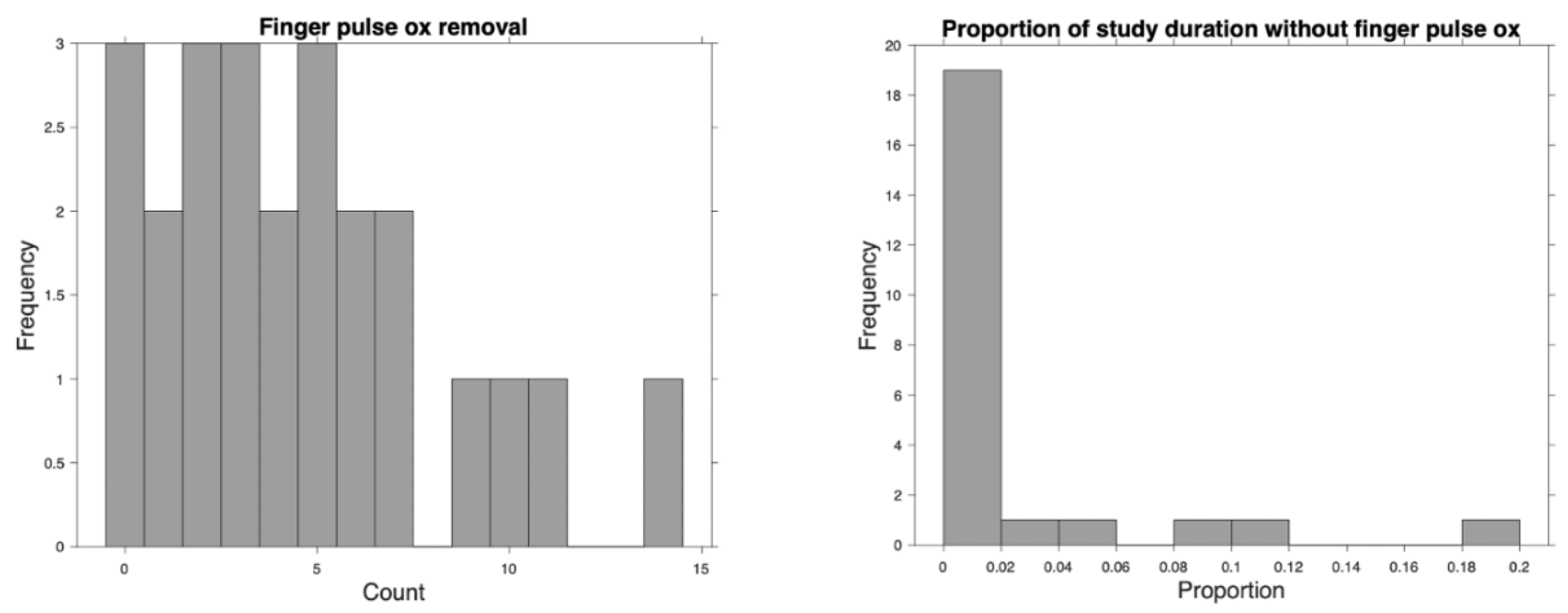

Figure 3). Participants removed the prototype 0 times, and the control device a mean 4.6 (sd 3.7) times (

Figure 4a), and the time removed is shown in

Figure 4b. 5 point Likert Scale feedback on comfort showed a mean rating of 4.6 for the shoulder, 4.5 for the ring and 3.1 for the finger mounted control (

Figure 5). Both the shoulder and ring were rated higher than the control de-vice (p<0.01).

Themes were identified in open-ended questions regarding the comfort or fit of the study-provided devices: Many participants reported that their control devices fell off either before falling asleep or during the night. One participant noted that the finger-based “commercial device came off a few times before sleeping” which caused “restless sleep”. Several participants also noted that the control devices either fell off or were purposefully re-moved throughout the night. Participants cited irritation, fit, and using the restroom as reasons for control device removal. One person noted that the wristband portion of the Prototype-ring fell off in the middle of the night. None complained of comfort worsened by the shoulder mounted device. Several participants complained that one or multiple devices disrupted their sleep. These devices included the Prototype-ring and commercial pulse oximeter. Tightness of fit was the most commonly problematic factor among these devices. One participant specifically cited the plastic shell that encased the data hardware in Prototype-ring as causing pain. Other participants removed the control device due to discomfort of a “burning sensation” or complaints that the device “was getting hot.” There was only one participant who specifically commented on Prototype-shoulder. This person stated that they slept on their side but there was “not much movement [to the device] while sleeping.”

Discussion

This study demonstrated a shoulder-based investigational SpO2 monitor prototype was accurate to within FDA-defined guidelines. Additionally, both shoulder-based and ring devices measured SpO2 with fewer interruptions to continuous monitoring than a traditional commercial finger pulse oximeter. Also, participants noted improved comfort compared to a commercial finger pulse oximeter. The open-ended questionnaire revealed this stemmed from issues with security to the finger, fit, and temperature. Participants reported accidental or purposeful removal of the commercial device both before and during their sleep studies, as well as interference with sleep from the control and ring devices. By contrast, the shoulder prototype did not carry the same reports. Collectively, these results support the concept that a shoulder-mounted pulse oximeter is a viable and potentially preferable configuration for SpO2 monitoring in patients receiving polysomnagraphy.

Shoulder-mounted pulse oximetry is also pertinent as an alternative to current finger-based wearables because it offers the opportunity to combine SpO2 monitoring with additional features, such as accelerometry, to detect apneic motion [

4,

12,

15]. These applications are important for people with sleep-disordered breathing at the highest risk of respiratory compromise [

13,

19]. This study demonstrates that shoulder-mounted pulse oximeters may be more comfortable and less disruptive than traditional finger-based pulse oximetry.

There were multiple limitations to this pilot. Firstly, the control pulse oximeter is an imperfect gold standard as its accuracy may be limited. Secondly, most participants did not provide constructive qualitative feedback for all study-provided devices, so it is difficult to evaluate the characteristics that drove improvements in Likert-scale score. Additionally, we did not collect sufficient data to correlate data quality with the participants’ sleep position. While participants were able to recollect removal and/or repositioning of the study-provided devices, the accuracy of their subjective reports is limited in the absence of a real-time record of behavior from the center’s technicians. Finally, this study was not powered or designed to assess meaningful clinical outcomes, nor for generalizability to more ill populations.

Conclusions:

Overall, this study confirms that alternative configurations for SpO2 monitoring offer potential as accurate and well-tolerated devices. Problems with traditional pulse oximetry, such as false readings of hypoxia due to device removal or noisy data, were encountered less frequently in Prototype-shoulder than in the commercial finger-based device. Users not only tolerated the shoulder-based form factor but also preferred this configuration relative to the traditional finger pulse oximeter.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Sample of Motion vs SpO2 Over Time; Supplemental Methods S1: Processing of motion and SPO2 data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, KK, JB, CB. and AL.; methodology, JB, CB and IG.; software, AL.; validation, AL., OO. and JB.; formal analysis, KK and CB.; investigation, AW, DG, AS, AL, and IG.; resources, JB and IG.; data curation, AL.; writing—original draft preparation, KK.; writing—review and editing, CB, OO, IG, DG, and JB.; visualization, KK.; supervision, JB and CB.; project administration, AW and KK; funding acquisition, JB and OO. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Coulter-Drexel Translational Research Partnership program.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol was approved by the University of Pennsylvania IRB and was performed in compliance with relevant laws and institutional guidelines.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized analyzed datasets available on request

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Drs. Alexis Roth for her work on synchronous projects and patience with our team

Conflicts of Interest

Cameron Baston receives consulting fees from Fujifilm/Sonosite. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SpO2 |

Peripheral Saturation of Oxygen |

References

- Alberto, R., Draicchio, F., Varrecchia, T., Silvetti, A., & Iavicoli, S. (2018). Wearable Monitoring Devices for Biomechanical Risk Assessment at Work: Current Status and Future Challenges-A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(9), 2001. [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, M. B., Rajagopal, S., Prieto-Simón, B., & Pogue, B. W. (2024). Recent advances in smart wearable sensors for continuous human health monitoring. Talanta, 272, 125817. [CrossRef]

- Khanna, A. K., Banga, A., Rigdon, J., White, B. N., Cuvillier, C., Ferraz, J., Olsen, F., Hackett, L., Bansal, V., & Kaw, R. (2024). Role of continuous pulse oximetry and capnography monitoring in the prevention of postoperative respiratory failure, postoperative opioid-induced respiratory depression and adverse outcomes on hospital wards: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Anesthesia, 94, 111374.

- Oteo, A., Daneshvar, H., Baldacchino, A., & Matheson, C. (2023). Overdose Alert and Response Technologies: State-of-the-art Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 25, e40389. [CrossRef]

- Vishesh K. Kapur, MD, MPH1, Dennis H. Auckley, MD2, Susmita Chowdhuri, MD3, David C. Kuhlmann, MD4, Reena Mehra, MD, MS5, Kannan Ramar, MBBS, MD6, & Christopher G. Harrod, MS7. (2017). Clinical Practice Guideline for Diagnostic Testing for Adult Obstructive Sleep Apnea: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 13(3), 479–504. [CrossRef]

- Dcosta, J. V., Ochoa, D., & Sanaur, S. (2023). Recent Progress in Flexible and Wearable All Organic Photoplethysmography Sensors for SpO2 Monitoring. Advanced Science (Weinheim, Baden-Wurttemberg, Germany), 10(31), e2302752. [CrossRef]

- May, J. M., Phillips, J. P., Fitchat, T., Ramaswamy, S., Snidvongs, S., & Kyriacou, P. A. (2019). A Novel Photoplethysmography Sensor for Vital Signs Monitoring from the Human Trachea. Biosensors, 9(4), 119. [CrossRef]

- Reich, J. D., Connolly, B., Bradley, G., Littman, S., Koeppel, W., Lewycky, P., & Liske, M. (2008). Reliability of a single pulse oximetry reading as a screening test for congenital heart disease in otherwise asymptomatic newborn infants: The importance of human factors. Pediatric Cardiology, 29(2), 371–376. [CrossRef]

- Şenaylı, Y. A., Keskin, G., Akın, M., Şenaylı, A., Ata, R., Demirtaş, G., & Şenel, E. (2023). A prospective study for an alternative probe site for pulse oximetry measurement in male patients with severe burn trauma: Penile shaf. Turkish Journal of Medical Sciences, 53(2), 504–510. [CrossRef]

- Opioid HaloTM Opioid Overdose Prevention & Alert System. (2023). Masimo. https://opioidhalo.masimo.com/products/opioid-halo (accessed 12/30/2024).

- Jubran, A. (2015). Pulse oximetry. Critical Care (London, England), 19(1), 272. [CrossRef]

- Chan, J., Iyer, V., Wang, A., Lyness, A., Kooner, P., Sunshine, J., & Gollakota, S. (2021). Closed-loop wearable naloxone injector system. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 22663. [CrossRef]

- Svider, P. F., Pashkova, A. A., Folbe, A. J., Eloy, J. D., Setzen, M., Baredes, S., & Eloy, J. A. (2013). Obstructive sleep apnea: Strategies for minimizing liability and enhancing patient safety. Otolaryngology--Head and Neck Surgery: Official Journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, 149(6), 947–953. [CrossRef]

- Imtiaz, M. S., Bandoian, C. V., & Santoro, T. J. (2021). Hypoxia driven opioid targeted automated device for overdose rescue. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 24513. [CrossRef]

- Kanter, K., Gallagher, R., Eweje, F., Lee, A., Gordon, D., Landy, S., Gasior, J., Soto-Calderon, H., Cronholm, P. F., Cocchiaro, B., Weimer, J., Roth, A., Lankenau, S., & Brenner, J. (2021). Willingness to use a wearable device capable of detecting and reversing overdose among people who use opioids in Philadelphia. Harm Reduction Journal, 18(1), 75. [CrossRef]

- Lingamoorthy A, Watson A, Donlon E, Weimer J & Brenner JS, "DOVE: Noninvasive Shoulder-based Opioid Overdose Detection Device," 2022 IEEE/ACM Conference on Connected Health: Applications, Systems and Engineering Technologies (CHASE), Arlington, VA, USA, 2022, pp. 182-183.May, J. M., Kyriacou, P. A., Honsel, M., & Petros, A. J. (2014). Investigation of photoplethysmographs from the anterior fontanelle of neonates. Physiological Measurement, 35(10), 1961–1973. [CrossRef]

- Jung, H., Kim, D., Lee, W., Seo, H., Seo, J., Choi, J., & Joo, E. Y. (2022). Performance evaluation of a wrist-worn reflectance pulse oximeter during sleep. Sleep Health, 8(5), 420–428. [CrossRef]

- FDA Executive Summary: Performance Evaluation of Pulse Oximeters Taking into Consideration Skin Pigmentation, Race, and Ethnicity. (2024, February 2). Anesthesiology and Respiratory Therapy Devices Panel of Medical Devices Advisory Committee. https://www.fda.gov/media/175828/download Accessed 12/30/2024.

- Fouladpour, N., Jesudoss, R., Bolden, N., Shaman, Z., & Auckley, D. (2016). Perioperative Complications in Obstructive Sleep Apnea Patients Undergoing Surgery: A Review of the Legal Literature. Anesthesia and Analgesia, 122(1), 145–151. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).