Submitted:

17 December 2025

Posted:

18 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

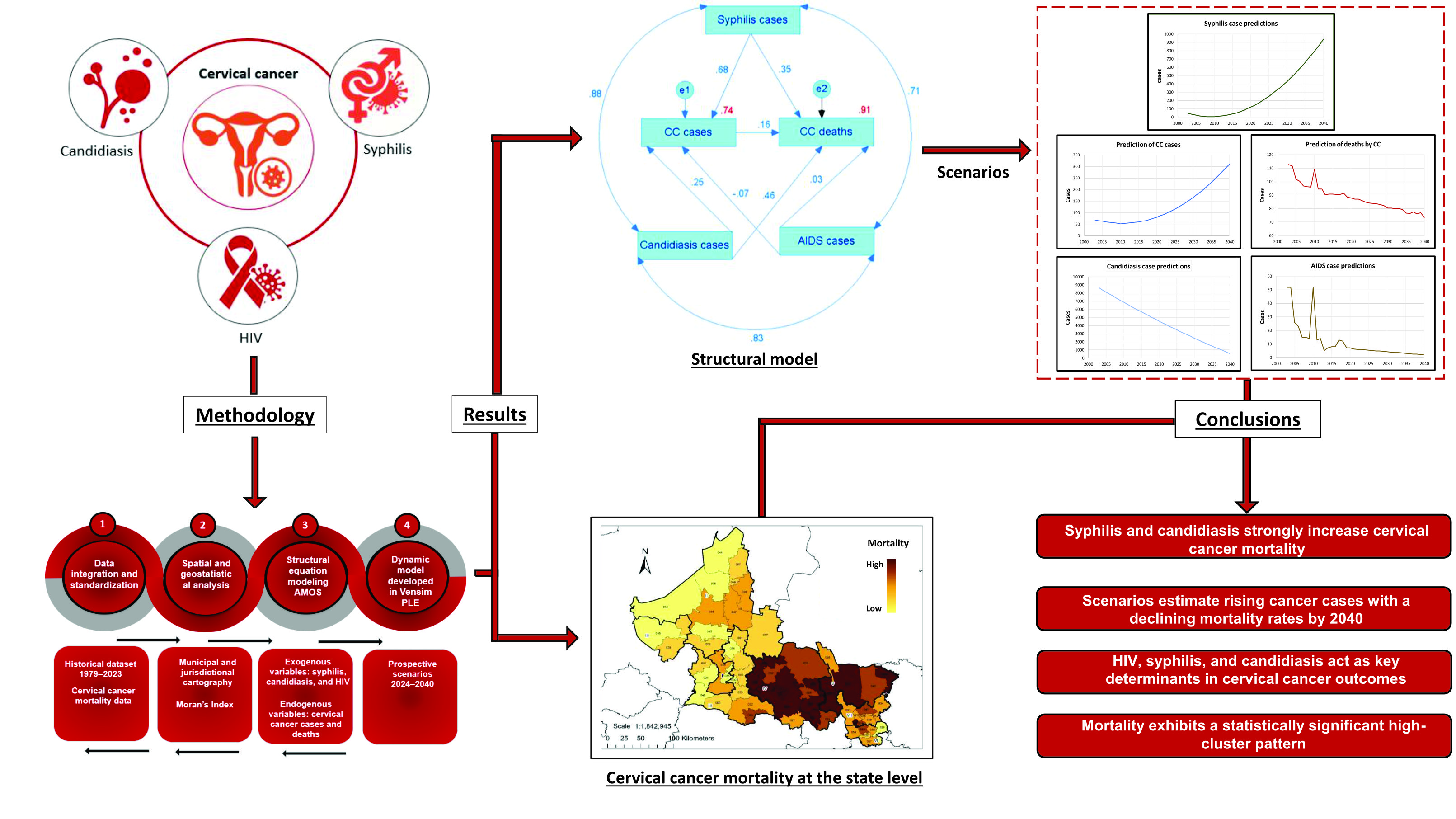

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

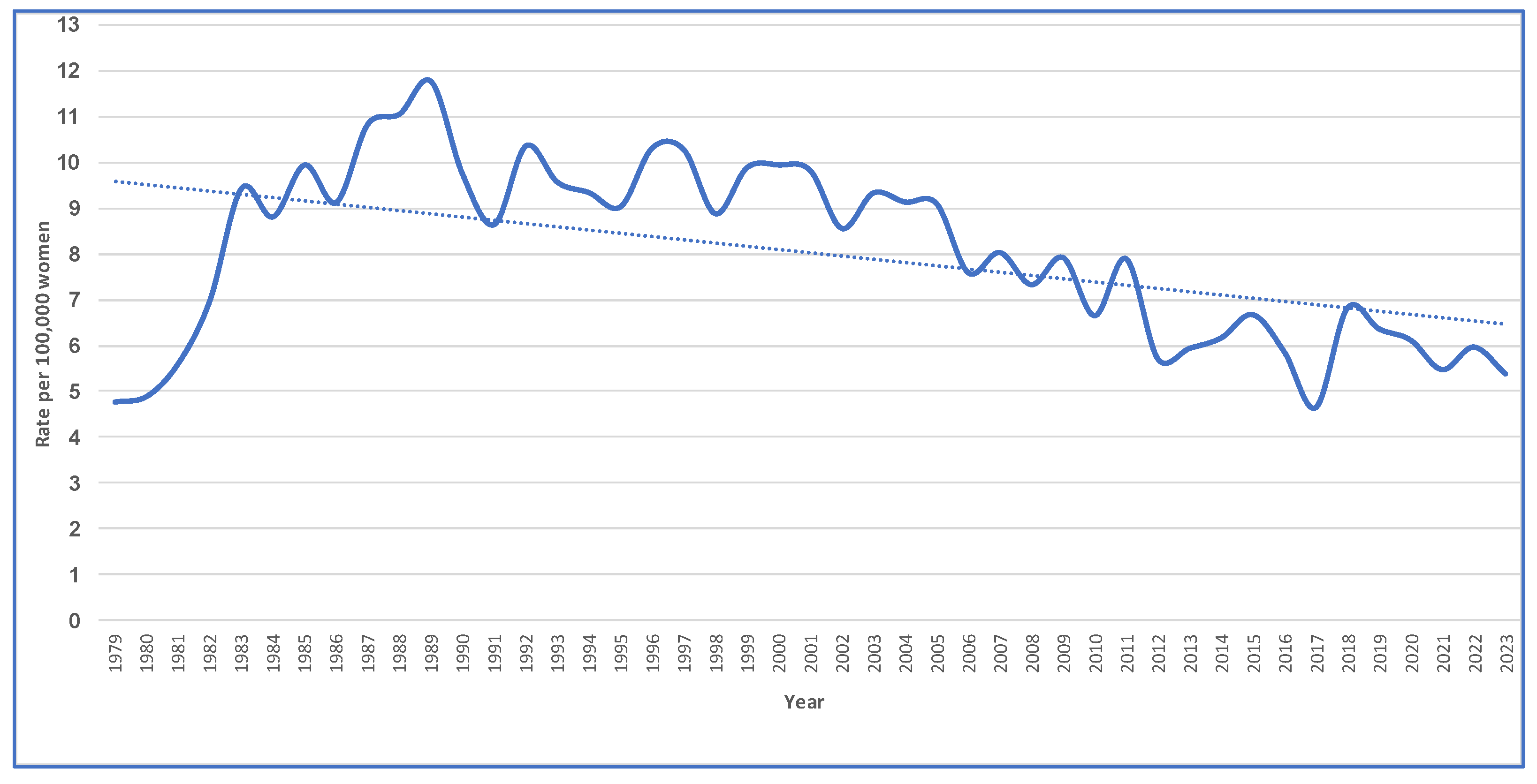

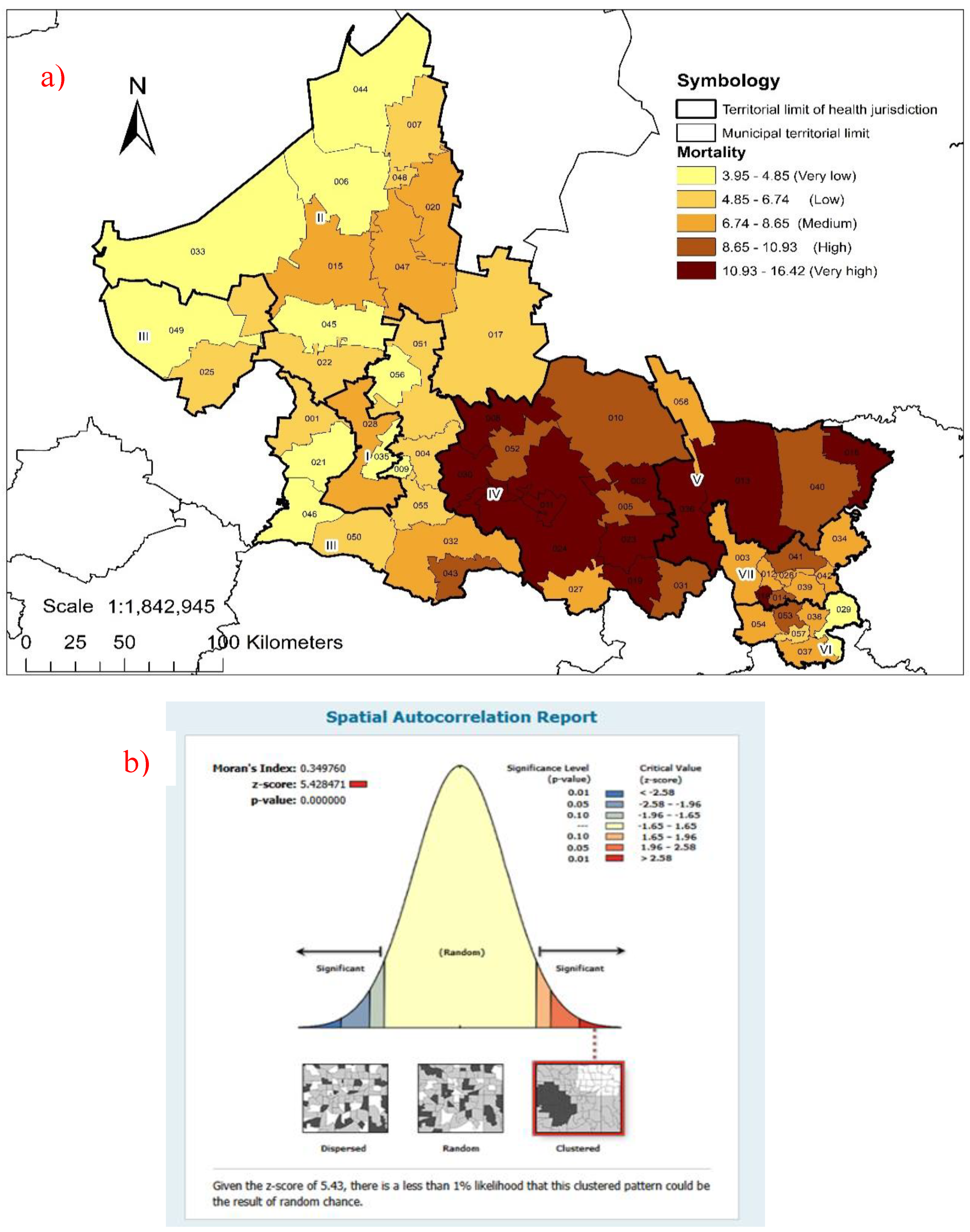

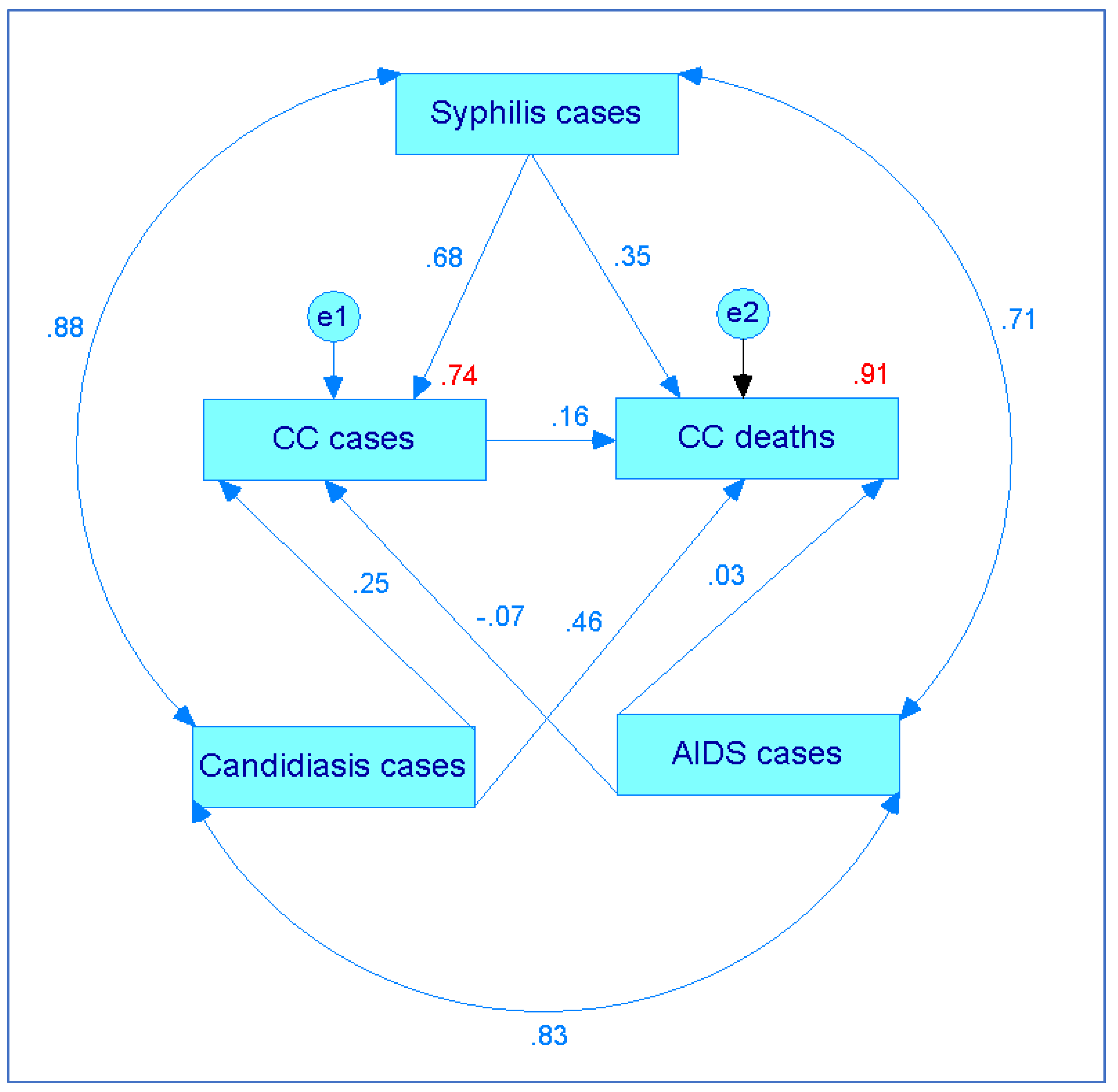

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

2.1. Type of Research Methods and Data Used.

2.2. Spatial Analysis

2.3. Future Scenario for the Factors Considered.

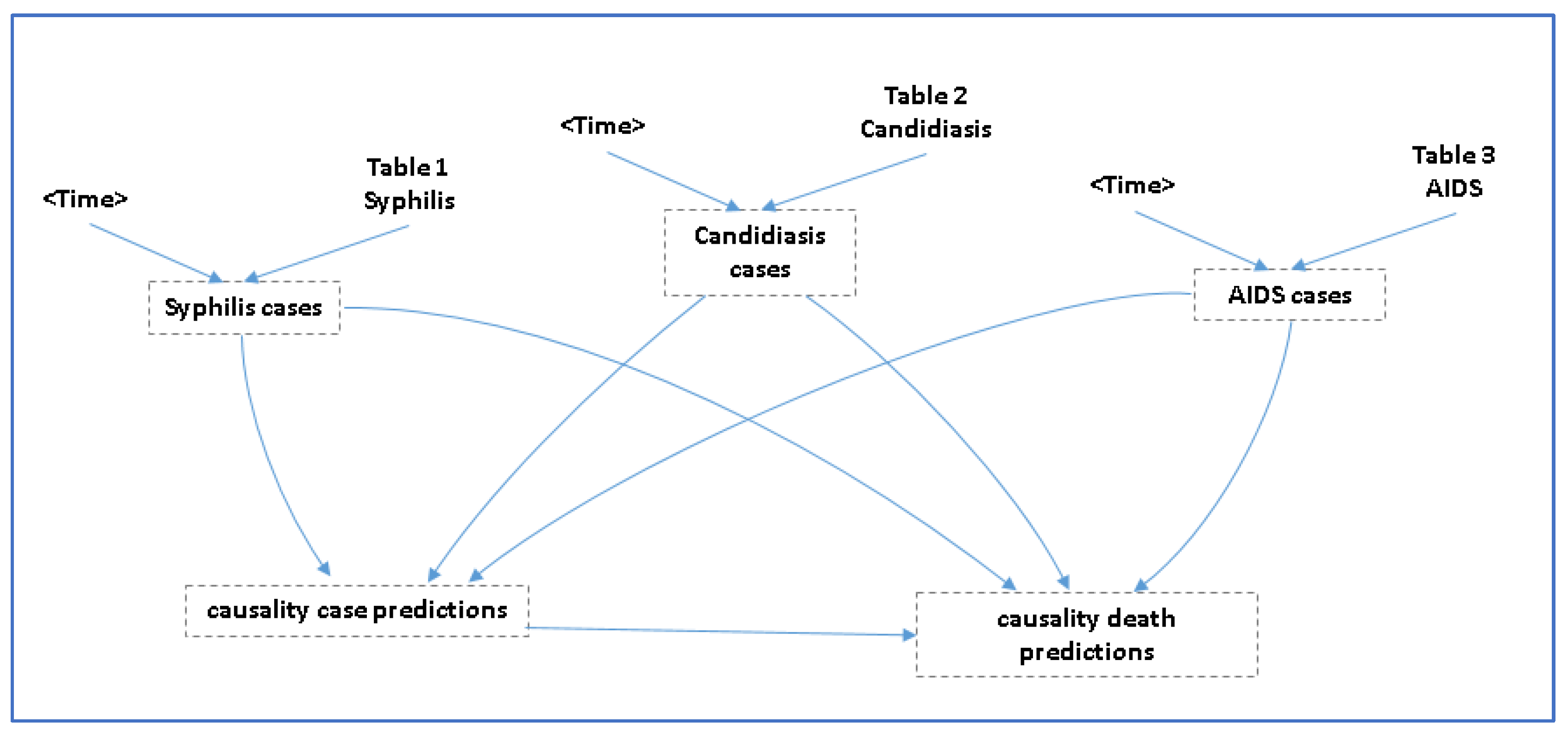

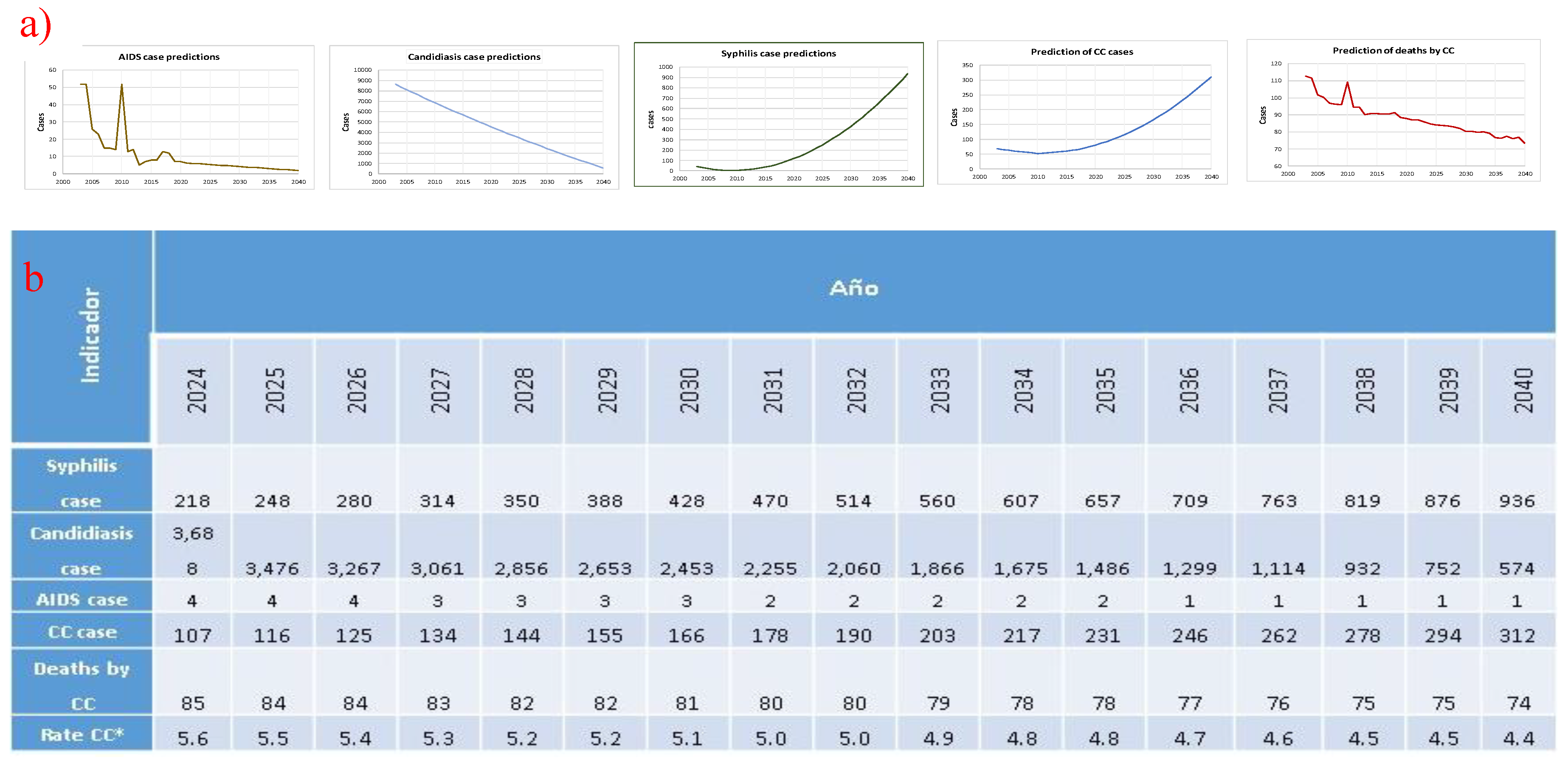

2.4. Prediction of CC Cases and CC Deaths

- (A)

- Cases of CC = 29.8303 + (cases of candidiasis * 0.0035) + (cases of syphilis * 0.299) + (cases of AIDS * −0.07)

- (B)

- Deaths due to CC = −2.21765e+06 + (74344.8 * cases of CC) − (22229.1 * cases of syphilis) + (5204.51 * cases of AIDS) − (260.205 * cases of candidiasis).

2.5. Statistical Analysis.

- (A)

- For candidiasis, we used “cases of candidiasis = 1.11209286*(year²) − 4714.17087*(year) + 4,989,396.71”. This model showed a strong match between the real data and the simulated values (R² = 0.923).

- (B)

- For syphilis, we used “syphilis cases = 0.98684211* (year − 2003)² − 12.33721805*(year − 2003) + 41.57857143”, with this model showing an acceptable degree of similarity with respect to the observed series (R² = 0.802).

- (C)

- For AIDS, we used “(t) = 6.1191•e^ (−0.0895 (t − 2020))”, where t represents the year in question.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CC | Cervical Cancer |

| HPV | Human Papillomavirus |

| STI | Sexually Transmitted Infection |

| HIV | Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| AIDS | Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome |

| DGE | General Directorate of Epidemiology |

| INEG | National Institute of Statistics and Geography |

| CONAPO | National Population Council |

| WGS | World Geodetic System |

| SHP | Shape File |

| HJs | Health Jurisdictions |

| CLUES | Unique Health Establishment Code |

References

- Nazzal Nazal, Omar.; Cuello Fredes, Mauricio. Evolución histórica de las vacunas contra el Virus Papiloma Humano. Revista chilena de obstetricia y ginecología. 2014, 79, 455-458. [CrossRef]

- Hull, R.; Mbele, M.; Makhafola, T.; Hicks, C.; Wang, S-M.; Reis, R.M.; Mehrotra, R.; Mkhize-Kwitshana, Z.; Kibiki, G.; Bates, D.O.; Dlamini, Z. Cervical cancer in low and middleincome countries. Oncol Lett. 2020; 20, 2058–2074. [CrossRef]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer, WHO. Cancer TODAY | IARC - https://gco.iarc.who.int. Data version: Globocan 2022 (version 1.1).

- Secretaría de Salud. Subsecretaría de prevención y promoción de la salud. Dirección General de Epidemiología. Gobierno de México. Boletín Epidemiológico. Sistema Nacional de Vigilancia Epidemiológica. Sistema Único de Información. Semana Epidemiológica. Número 51 / Volumen 41 / Semana 51 / Del 15 al 21 de diciembre del 2024.

- Secretaría de Salud. Subsecretaría de prevención y promoción de la salud. Dirección General de Epidemiología. Gobierno de México. Boletín Epidemiológico. Sistema Nacional de Vigilancia Epidemiológica. Sistema Único de Información. Semana Epidemiológica. Número 15 / Volumen 42 / Semana 15 / Del 6 al 12 de abril del 2025.

- Sarenac, T.; Mikov, M. Cervical cancer, different treatments and importance of bile acids as therapeutic agents in this disease. Front Pharmacol. 2019; 10, 484. [CrossRef]

- Shekhar, S.; Sharma, C.; Thakur, S.; Raina, N. Cervical cancer screening: knowledge, attitude and practices among nursing staff in a tertiary level teaching institution of rural India. Asian Pacific J Cancer Prevent. 2013;14, 3641-3645. [CrossRef]

- Torres-Poveda, K.J.M; Arredondo-López, A.A.; Duarte-Gómez, M.B. La mujer indígena, vulnerable a cáncer cervicouterino: Perspectiva desde modelos conceptuales de salud pública. Salud Tabasco. 2008; 14:807-815. https://biblat.unam.mx/hevila/SaludenTabasco/2008/vol14/no3/5.pdf.

- Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública. Síntesis sobre Políticas de Salud. Prevención y control del cáncer cervical en México. https://insp.mx/assets/documents/webinars/2021/CISP_Cancer_Cervical.pdf.

- Terán-Figueroa, Y.; Muñiz-Carreón, P.; Fernández Moya, M.; Galán-Cuevas, S.; Noyola-Rangel, N.; Gutiérrez-Enríquez, S.O.; Ortiz-Valdez, L.A.; Cruz-Valdez, A. Repercusión del cáncer cervicouterino en pacientes con limitaciones de acceso a los servicios de salud. Ginecol Obstet Mex. 2015; 83:162-172. https://www.medigraphic.com/pdfs/ginobsmex/gom-2015/gom153e.pdf.

- Ochoa Carrillo, F.J. Gaceta Mexicana de Oncología. 2015; 14, 214-221. [CrossRef]

- Secretaría de Salud. Campaña de mitigación del rezago de esquemas de vacunación contra el Virus del Papiloma Humano (VPH), 2023. Lineamientos generales. Programa de vacunación universal. https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/852406/LINEAMIENTOS_VACUNA_VPH_2023.pdf.

- de Sanjosé, S.; Brotons, M.; Pavón, M.A. The natural history of human papillomavirus infection. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2018; 47, 2– 13. [CrossRef]

- Doorbar, J., Egawa, N.; Griffin, H.; Kranjec, C.; Murakami, I. Human papillomavirus molecular biology and disease association. Rev Med Virol. 2015; 25 S, 2–23. [CrossRef]

- Castellsagué Piqué, X.; de Sanjosé Llongueras, S.; Bosch Jose, F.J. Epidemiología de la infección por VPH y del cáncer de cuello de útero. Nuevas opciones preventivas. En: Carreras Collado R, Xercavins Montosa J y Checa Vizcaíno MA. Virus del Papiloma Human y Cáncer de Cuello de Útero. Madrid, España: Editorial Médica Panamericana; 2007, p. 14 – 17.

- Chesson, H.W.; Dunne, E.F.; Hariri, S.; Markowitz, L.E. The estimated lifetime probability of acquiring human papillomavirus in the United States. Sex Transm Dis. 2014; 41, 660–4. [CrossRef]

- Secretaría de Salud. DGIS. Cubos dinámicos. Defunciones. 2025. http://www.dgis.salud.gob.mx/contenidos/basesdedatos/bdc_defunciones_gobmx.html.

- Instituto Nacional de Geografía y Estadística. Datos abiertos. Registros administrativos- estadísticas. Vitales. Estadísticas de defunciones registradas. https://www.inegi.org.mx/datosabiertos/.

- Gobierno de México. Consejo Nacional de Población. Reconstrucción y proyecciones de la población de los municipios de México 1990-2040. 2024, (https://www.gob.mx/conapo/documentos/reconstruccion-y-proyecciones-de-la-poblacion-de-los-municipios-de-mexico-1990-2040.

- Secretaría de Salud. SSA: DGIS, Histórico de bases CLUES. http://gobi.salud.gob.mx/Bases_Clues.html.

- Environmental Systems Research Institute. ESRI: Cómo funciona Autocorrelación espacial (I de Moran global). https://pro.arcgis.com/es/pro-app/latest/tool-reference/spatial-statistics/h-how-spatial-autocorrelation-moran-s-i-spatial-st.htm.

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. Cáncer de cuello uterino. 17 de noviembre de 2023. https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cervical-cancer.

- Terán-Figueroa, Y.; García-Díaz, J.; González-Rubio, M.V.; Gaytán-Hernández, D.; Gutiérrez-Enríquez, S.O. Mortalidad y supervivencia por cáncer cervicouterino en beneficiarias del Seguro Popular en el estado de San Luis Potosí, México. Periodo 2005-2012. Acta Universitaria. 2020, 30, e2412. http://doi.org/10.15174.au.2020.2412.

- Obando, J.; Peña, P.; Obando, L.; Franco, A. Importancia de los modelos de regresión no lineales en la interpretación de datos de la COVID-19 en Colombia. Revista Habanera de Ciencias Médicas. 2020, 19 S1. http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1729519X2020000400014&lng=es&tlng.

- Manabe, H.; Manabe, T.; Honda, Y.; Kawade, Y.; Kambayashi, D.; Manabe, Y.; Kudo, K. Simple mathematical model for predicting COVID-19 outbreaks in Japan based on epidemic waves with a cyclical trend. BMC Infect Dis. 2024, 24, 465. [CrossRef]

- Gaytán-Hernández, D.; Díaz-Oviedo, A.; Gallegos-García, V.; Terán-Figueroa, Y. Situación futura de la cardiopatía isquémica en el estado de San Luis Potosí: un modelo dinámico predictivo. Archivos de cardiología de México. 2018, 88, 140-147. [CrossRef]

- Diario Oficial de la Federación, Secretaría de Gobernación, México Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM- 014-SSA-1994, para la prevención, detección, diagnóstico, tratamiento, control y vigilancia epidemiológica del cáncer uterino. 18 de mayo de 2007.

- Scher, H.I.; Solo, K.; Valant, J.; Todd, M.B.; Mehra, M. Prevalence of Prostate Cancer Clinical States and Mortality in the United States: Estimates Using a Dynamic Progression Model. PLoS One. 2015, 13, e0139440. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Hou, Y.; Lyu, J.; Liu, D.; Chen Z. Dynamic prediction and prognostic analysis of patients with cervical cancer: a landmarking analysis approach. Ann Epidemiol. 2020, 44:45-51. [CrossRef]

- Kasaie, P.; Stewart, C.; Humes, E.; Gerace, L.; Hyle, E.P.; Zalla, L.C.; Rebeiro, P.F.; Silverberg, M.J.; Rubtsova, A.A.; Rich, A.J.; Gebo, K.; Lesko, C.R.; Fojo, A.T.; Lang, R.; Edwards, J.K.; Althoff, K.N. Impact of subgroup-specific heterogeneities and dynamic changes in mortality rates on forecasted population size, deaths, and age distribution of persons receiving antiretroviral treatment in the United States: a computer simulation study. Ann Epidemiol. 2023, 87: S1047-2797. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yang, Z.; Hou, Y.; Chen, Z. Moving beyond the Cox proportional hazards model in survival data analysis: a cervical cancer study. BMJ Open. 2020, 19, e033965. [CrossRef]

- Batista, J.; Coenders, G. Modelos de ecuaciones estructurales. Madrid: La Muralla, 2000.

- González Guzmán, R.; Alcalá Ramírez, J. Enfermedad isquémica del corazón, epi-demiología y prevención. Rev Facultad Med UNAM. 2010, 53, 35-43. https://www.medigraphic.com/pdfs/facmed/un-2010/un105h.pdf.

- Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Cáncer Cervicouterino. Washington: OPS https://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=5420:2018-cervicalcancer&Itemid=3637&lang=es.

- The Global Cancer Observatory. International Agency for Research on Cancer. Mexico Source: Globocan 2020. Ginebra: World Health Organization, 2021. https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/populations/484-mexico-fact-sheets.pdf ).

- Silva Filho, A.L.D.; Romualdo, G.R.; Pinhati, M.E.S.; Neves, G.L.; Oliveira, J.A.; Moretti-Marques, R.; Nogueira-Rodrigues, A.; Tsunoda, A.T.; Cândido, E.B. Exploring cervical cancer mortality in Brazil: an ecological study on socioeconomic and healthcare factors. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2025, 35,101851. [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Geografía y Estadística. Datos abiertos. Información Demográfica y Social. Censos y Conteos. Censos y Conteos de Población y Vivienda 2020. https://www.inegi.org.mx/datosabiertos/.

- Canfell, K.; Kim, J.J.; Brisson, M.; Keane, A.; Simms, K.T.; Caruana, M.; Burger, E.A.; Martin, D.; Nguyen, D.T.N.; Bénard, É.; Sy, S.; Regan, C.; Drolet, M.; Gingras, G.; Laprise, J.F.; Torode, J.; Smith, M.A.; Fidarova, E.; Trapani, D.; Bray, F.; Ilbawi, A.; Broutet, N.; Hutubessy, R. Mortality impact of achieving WHO cervical cancer elimination targets: a comparative modelling analysis in 78 low-income and lower-middle-income countries. Lancet. 2020, 22, 591-603. [CrossRef]

- Kanyina, E.W.; Kamau, L.; Muturi, M. Cervical precancerous changes and selected cervical microbial infections, Kiambu County, Kenya, 2014: a cross sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2017, 17, 647. [CrossRef]

- Bhojani, K.R.; Garg, R. Cytopathological study of cervical smears and correlation of findings with risk factors. Int J Biol Med Res. 2011, 2, 757–61. https://www.biomedscidirect.com/journalfiles/IJBMRF2011245/cytopathological-study-of-cervical-smears-and-corelation-of-findings-with-risk-factors.pdf.

- Claeys, P.; Gonzalez, C.; Gonzalez, M.; Van Renterghem, L.; Temmerman, M. Prevalence and risk factors of sexually transmitted infections and cervical neoplasia in women’s health clinics in Nicaragua. J Sex Transm Infect. 2002, 78:204–207. [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, J.A.; Blaser, M.J.; Caporaso, J.G.; Jansson, J.K.; Lynch, S.V.; Knight, R. Current understanding of the human microbiome. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 392–400. [CrossRef]

- Talapko, J.; Juzbaši´c, M.; Matijevi´c, T.; Pustijanac, E.; Beki´c, S.; Kotris, I.; Škrlec, I. Candida albicans-The Virulence Factors and Clinical Manifestations of Infection. J. Fungi. 2021, 7, 79. [CrossRef]

- Cullin, N.; Azevedo Antunes, C.; Straussman, R.; Stein-Thoeringer, C.K.; Elinav, E. Microbiome and cancer. Cancer Cell. 2021, 39, 1317-1341. [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Liu, Z. The research progress in the interaction between Candida albicans and cancers. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 988734. [CrossRef]

- Talapko, J.; Meštrović, T.; Dmitrović, B.; Juzbašić, M.; Matijević, T.; Bekić, S.; Erić, S.; Flam, J.; Belić, D.; Petek Erić, A.; Milostić Srb, A.; Škrlec, I. A Putative Role of Candida albicans in Promoting Cancer Development: A Current State of Evidence and Proposed Mechanisms. Microorganisms. 2023. 11, 1476. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, W.; Wu, W.; Wu, S.; Young, A.; Yan, Z. Is Candida albicans a contributor to cancer? A critical review based on the current evidence. Microbiol Res. 2023, 272:127370. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.W.; Lee, Y.C.; Lee, Y.S.; Chang, L.C.; Lai, Y.R. Risk assessment of malignant transformation of oral leukoplakia in patients with previous oral squamous cell carcinoma. Int J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 51, 1394–1400. [CrossRef]

- Engberts, M.K.; Vermeulen, C.F.; Verbruggen, B.S.; van Haaften, M.; Boon, M.E.; Heintz, A.P. Candida and squamous (pre)neoplasia of immigrants and Dutch women as established in population-based cervical screening. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006, 16, 1596-600. [CrossRef]

- Engberts, M.K., Verbruggen, B.S., Boon, M.E., van Haaften, M., Heintz, A.P. Candida and dysbacteriosis: a cytologic, population-based study of 100,605 asymptomatic women concerning cervical carcinogenesis. Cancer-Am Cancer Soc. 2007, 111, 269–274. [CrossRef]

- Coghill, A.E.; Shiels, M.S.; Suneja, G.; Engels, E.A. Elevated Cancer-Specific Mortality Among HIV-Infected Patients in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2015, 33, 2376-83. [CrossRef]

- Robbins, H.A.; Pfeiffer, R.M.; Shiels, M.S.; Li, J.; Hall, H.I.; Engels, E.A. Excess cancers among HIV-infected people in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015, 107, dju503. [CrossRef]

- Berretta, M.; Di Francia, R.; Stanzione, B.; Facchini, G.; LLeshi, A.; De Paoli, P.; Spina, M.; Tirelli, U. New treatment strategies for HIV-positive cancer patients undergoing antiblastic chemotherapy. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2016, 7, 2391-2403. [CrossRef]

- Sabattini, E.; Bacci, F.; Sagramoso, C.; Pileri, S.A. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues in 2008: an overview. Pathologica. 2010, 102, 83-7. PMID: 21171509.

- Shmakova, A.; Germini, D.; Vassetzky, Y. HIV-1, HAART and cancer: A complex relationship. Int J Cancer. 2020, 146, 2666-2679. [CrossRef]

- Dias Neto, N.M.; Moura Dias, V.G.N.; Christofolini, D.M. Is syphilis infection a risk factor for cervicovaginal HPV occurrence? A case-control study. J Infect Public Health. 2024, 17, 102472. [CrossRef]

- Abebe, M.; Eshetie, S.; Tessema, B. Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections among cervical cancer suspected women at University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis. 2021, 21: 378. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, P.; Yin, A.; Zhang, B.; Xu, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Tang, L.; Kong, B.; Song, K. Global landscape of cervical cancer incidence and mortality in 2022 and predictions to 2030: The urgent need to address inequalities in cervical cancer. Int J Cancer. 2025, 157(2): 288-297. [CrossRef]

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. Estrategia mundial para acelerar la eliminación del cáncer del cuello uterino como problema de salud pública. 2022. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/359000/9789240039124-spa.pdf?sequence=1.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).