1. Introduction

The global demand for poultry products continues to rise, driven by population growth, urbanization, and increased per capita meat consumption (Miller et al., 2022; van der Laan et al., 2024). The poultry industry plays a pivotal role in global food security by providing animal protein including poultry meat and eggs which are among the most affordable sources of high-quality animal protein, especially in low- and middle-income countries. However, the productivity of the poultry industry is persistently challenged by Salmonella spp, a group of zoonotic, foodborne pathogens responsible for considerable public health concerns and economic losses (Naeem & Bourassa, 2024). According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC 2024) over 1 million illnesses are estimated to be caused by non-typhoidal Salmonella annually in the United States alone, with contaminated poultry products often implicated as a primary source. In poultry, Salmonella mainly colonizes the intestinal tract, often without clinical symptoms, making detection and control difficult (Shaji et al., 2023). Birds act as asymptomatic carriers and shed the pathogen through feces which consequently contaminate the environment, feed, and eggs. The persistence of Salmonella in poultry production environments presents a significant challenge for on-farm biosecurity, processing hygiene, and food safety management. Historically, antibiotic growth promoters (AGPs) were widely used to control pathogens like Salmonella and enhance poultry growth performance. However, the global rise of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and increasing consumer demand for antibiotic-free poultry products have prompted regulatory agencies in many countries to restrict or ban AGPs (Abreu et al., 2023; Wickramasuriya et al., 2024). This shift has created an urgent need for sustainable alternatives to antibiotics that can support poultry health and reduce pathogen load without contributing to AMR.

Probiotics have emerged as one of the most promising strategies in this context. They are defined by the FAO/WHO (2021) as “live microorganisms which, when administered and consumed in food in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host”. Probiotics are gaining grounds and are increasingly being incorporated into poultry production to promote gut health, enhance immunity, and mitigate pathogen colonization, including Salmonella spp. Several recent studies have demonstrated the ability of specific probiotic strains to reduce Salmonella shedding and colonization in poultry through various mechanisms, such as competitive exclusion, modulation of the gut microbiota, enhancement of mucosal immunity, and production of antimicrobial metabolites (Naeem & Bourassa, 2025, Elabbasy et al., 2025). While the use of probiotics in poultry production is not new, advancements in microbiome research, molecular tools, and high-throughput screening have enabled the development of more targeted and effective probiotic formulations. These innovations offer potential for tailoring probiotic interventions to specific poultry breeds, rearing systems, and pathogen profiles.

This review provides an update on the status of probiotic use against Salmonella in poultry with exploration into the types of probiotics used, their mechanisms of action, key findings from recent studies, and challenges associated with their commercial application. We also consider emerging probiotic candidates from other hosts or environments and highlight future directions for optimizing probiotic efficacy in poultry production systems.

2. Overview of Salmonella Prevalence and Pathogenesis in Broiler Chickens

Salmonella spp. are Gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped bacteria within the family

Enterobacteriaceae and among over 2,600 known serovars, only a subset is commonly linked with poultry and human illness. The most prevalent serovars associated with poultry are

Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis and

S. Typhimurium, both of which significantly contribute to human salmonellosis globally (Foley et al., 2021; Huang et al., 2023). Poultry can acquire

Salmonella through multiple routes, including vertical transmission, from infected breeder hens to eggs and horizontal transmission via contaminated feed, water, litter, personnel, or equipment. In particular, chicks are highly vulnerable to early colonization, and once infected, they often remain asymptomatic carriers, shedding the pathogen intermittently throughout their lives (Marietto-Gonçalves et al., 2022; Zeng et al., 2023). Following oral ingestion,

Salmonella colonizes the gastrointestinal tract, especially the cecum and ileum where it exhibits remarkable adaptability which allows it to adhere to and invade intestinal epithelial cells, persist in host tissues, evade immune responses, and form biofilms that promote environmental survival (Santos et al., 2021). These adaptation strategies also allow

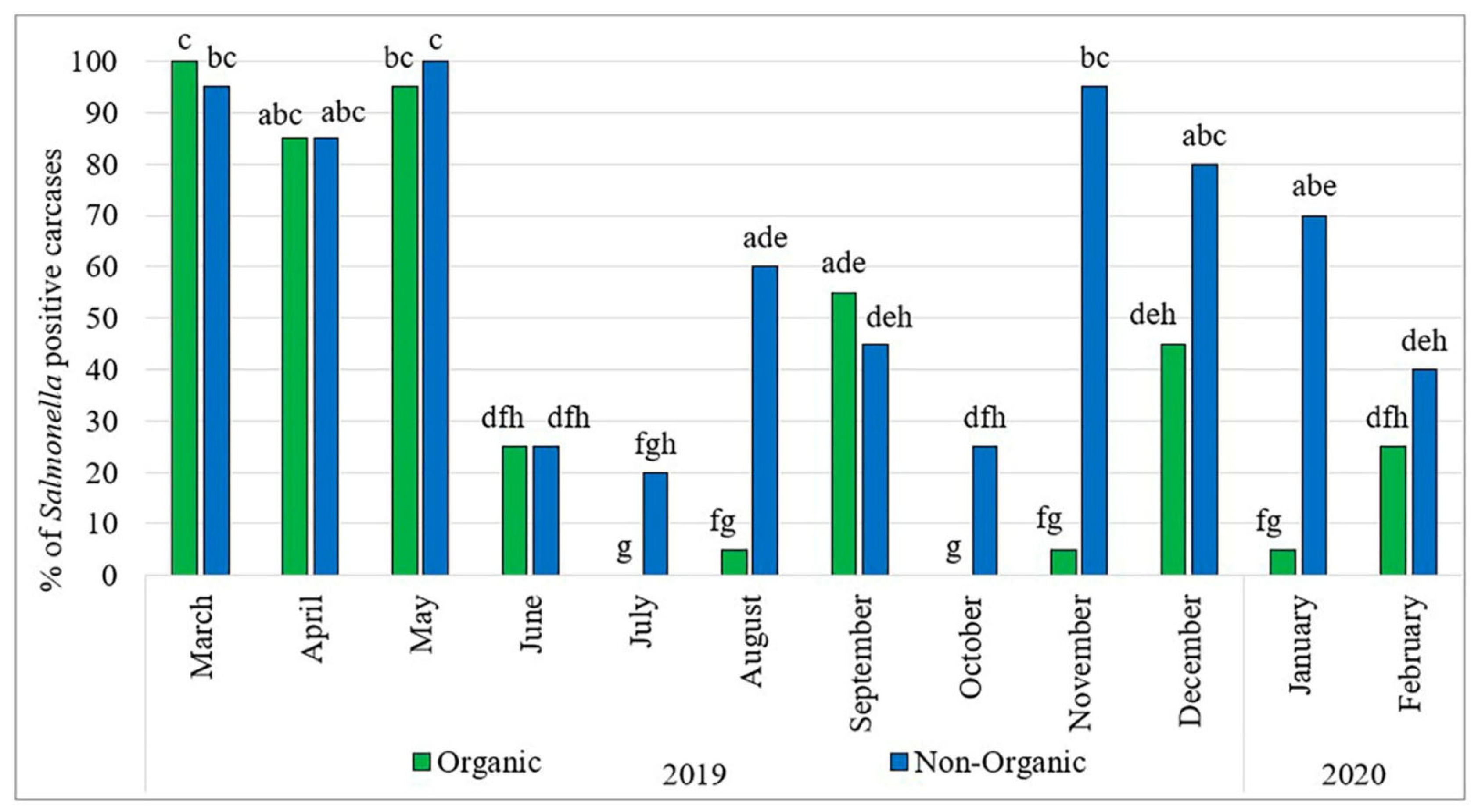

Salmonella to persist in litter, dust, and farm infrastructure, making eradication a major challenge without robust biosecurity practices (Iwueke et al., 2022). A study conducted in North Carolina, US found that 52.31% of broiler chickens in commercial farms were infected with

Salmonella serotypes (Parzygnat

et al., 2024) while multistate

Salmonella outbreaks relating to backyard poultry have been recently discovered by the CDC (CDC, 2024a). Also, findings from Punchihewage-Don et al., 2023 (

Figure 1) indicate a substantial burden of

Salmonella in organic and non-organic chickens, characterized by resistance to critical antibiotics and the presence of virulence genes, which together heighten the potential risk of Salmonellosis. From a public health standpoint, contaminated poultry products especially raw or undercooked meat and eggs serve as major sources of

Salmonella infection in humans. Mishandling, inadequate cooking, and cross-contamination during processing or food preparation also facilitate outbreaks. According to the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA & ECDC, 2023),

S. Enteritidis remains the leading cause of foodborne outbreaks in Europe, with poultry products frequently implicated. Economically,

Salmonella infections in poultry lead to direct losses through reduced performance and increased mortality, and indirect losses through trade restrictions, regulatory penalties, recalls, and diminished consumer trust. The increasing emergence of multidrug-resistant

Salmonella strains from poultry further complicates control efforts and raises significant One Health concerns (Lee et al., 2023). Given these risks, reducing

Salmonella colonization in poultry remains a high priority for both the poultry industry and public health sectors. Moreover, despite the immune system ability to detect pathogens through Pattern Recognition Receptors (PRRs) like Toll-like receptors (TLRs),

Salmonella may evade detection by the modification of the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) on its surface prevents recognition by TLR4 or downregulate the expression of certain surface antigens that are typically recognized by the immune system (Wang

et al., 2020; Duan

et al., 2022; Krzyżewska-Dudek

et al., 2024).

The poultry gut and immune system produce various antimicrobial peptides and reactive oxygen species (ROS) which aids in the destruction of invading pathogens. However, Salmonella can alter the structure of its outer membrane, reducing the permeability to antimicrobial peptides which are alternatives explored for pathogen suppression (Aleksandrowicz et al., 2024) while protecting itself from oxidative stress by secreting the superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase enzymes (Hahn et al., 2021). In some cases, Salmonella can establish a chronic, asymptomatic infection in poultry by modulating the host immune system and remaining dormant (Shaji et al., 2023), reducing the likelihood of being detected and eliminated by the host immune response. The prevalence of Salmonella in host cells and tissues is a significant challenge in poultry populations, however, alternatives to antibiotics, especially probiotics, have emerged as promising tools in this fight, offering a sustainable means to inhibit the multiplication of Salmonella species in birds before the chance to colonize or invade the host tissues.

3. Probiotics and their Mechanism of Action Against Salmonella

Given the limitations of antibiotics and the persistent burden of Salmonella in poultry, probiotics have emerged as one of the most promising alternatives for reducing pathogen colonization in birds. Probiotics which are defined as “live microorganisms which, when administered and consumed in food in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host” have gained increasing attention in poultry production due to their potential to reduce

Salmonella colonization without promoting antimicrobial resistance (FAO/WHO, 2021; Fonseca et al., 2024). Importantly, probiotics used in poultry must meet specific criteria including non-pathogenicity, acid- and bile-tolerance, ability to adhere to intestinal epithelial cells, and antimicrobial activity against pathogens (Li et al., 2024). Various bacterial strains, particularly those from the genera

Lactobacillus,

Bifidobacterium,

Bacillus,

Enterococcus and

Saccharomyces have been studied for their ability to inhibit

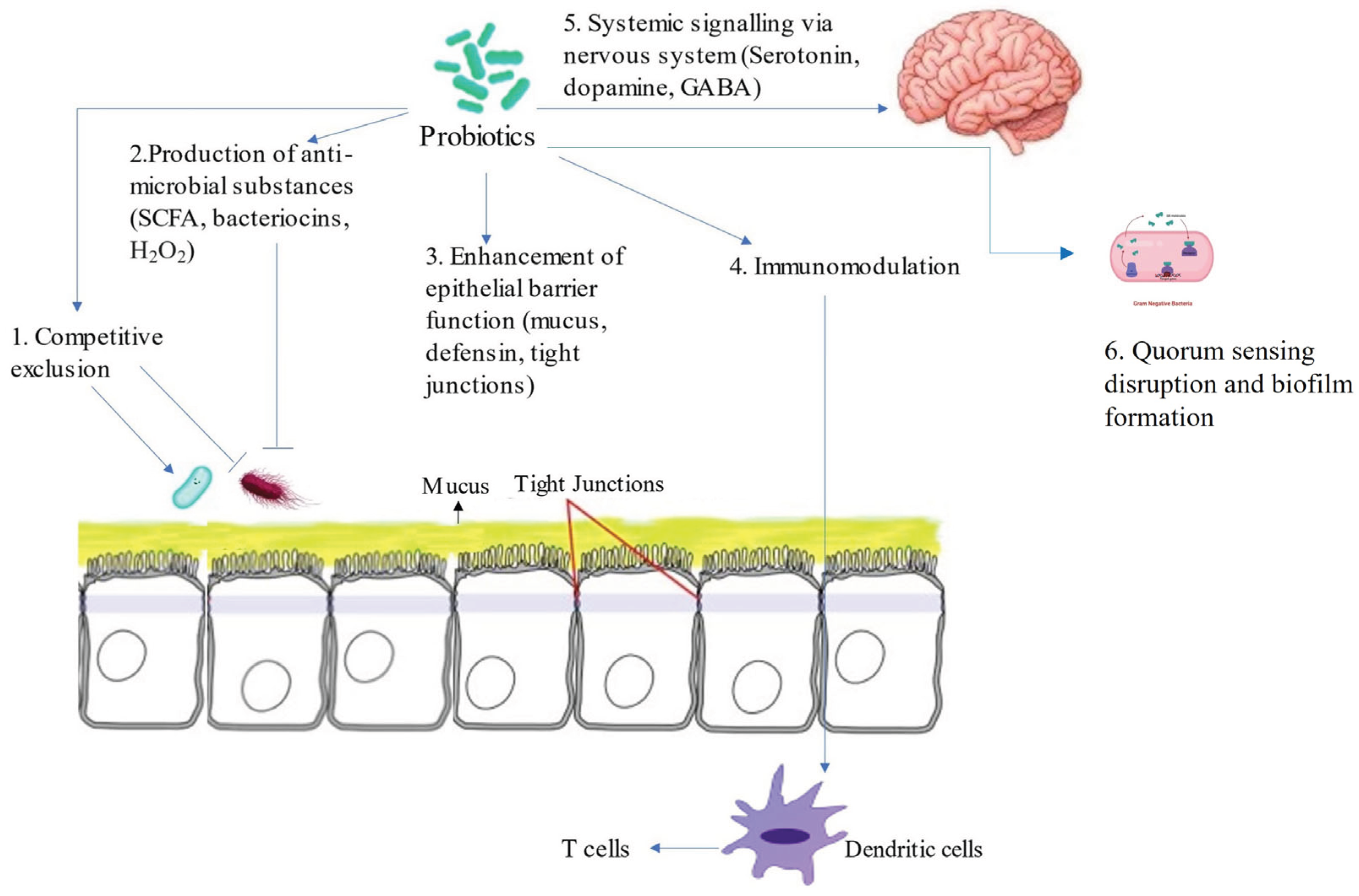

Salmonella through multiple mechanisms that collectively support host gut health and pathogen exclusion (Sachdeva et al., 2025). In poultry production, probiotics are often incorporated into feed or water as supplements to promote the health and productivity of chickens, turkeys, and other birds. Like pathogenic bacteria, probiotics act by colonizing the gastrointestinal tract and influencing various physiological processes that enhance overall poultry performance. Moreover, probiotics exert their benefits through both direct and indirect effects on the host and its microbial environment (Cunningham, 2021). Direct effects involve actions that target pathogenic bacteria such as inhibiting Salmonella growth, preventing adhesion, or outcompeting pathogens within the intestinal niche while indirect effects, on the other hand, support the host’s natural defenses by enhancing intestinal integrity, modulating immune responses, and improving overall gut resilience. Specifically, as shown in

Figure 2, the effectiveness of probiotics in poultry may depend on their ability to inhibit pathogenic bacteria and mechanism of action such as competitive exclusion, enhancement of gut barrier functions, quorum sensing disruption, biofilm formation, modulation of the immune system and the production antimicrobials and metabolites (Kogut, 2019; Abd El-Hack

et al., 2020; Kulkarni

et al., 2022, Latif

et al., 2023).

3.1. Competitive Exclusion

One of the primary ways probiotics protect poultry against Salmonella is through competitive exclusion. This mechanism involves probiotic bacteria occupying adhesion sites on the intestinal mucosa and competing for nutrients essential for pathogen survival (Latif et al., 2023). By establishing early colonization in the gastrointestinal tract, probiotics reduce the ecological niche available for Salmonella, thereby minimizing its attachment, proliferation, and translocation across the gut barrier. Early colonization by beneficial bacteria limits Salmonella’s ability to establish itself in the gut, a key factor especially in young chicks (Pedroso et al., 2021). Also, when in the gut, probiotics occupy binding sites, consume nutrients, and produce antimicrobial compounds such as lactic acid and bacteriocins which reduce the overall population of AMR-carrying pathogens (Chandrasekaran et al., 2024; Sachdeva et al., 2025) thus limiting the likelihood of gene exchange events. They also acidify the gut by the production of organic acid which lowers the gut pH and creates conditions that are less favorable for plasmid stability and transfer since certain resistance plasmids are less stable or transferable under acidic or nutrient-limited conditions thereby effectively reducing their spread (Ott & Mellata, 2024).

Several in vivo trials have confirmed reduced Salmonella counts following administration of mixed probiotic cultures that effectively outcompete pathogens for adhesion sites and carbon sources (Niu et al., 2025; Elabbasy et al., 2025). Moreover, competitive exclusion is often enhanced by probiotics producing extracellular polysaccharides that strengthen their adhesion to the mucosa (Zhu et al., 2023).

3.2. Production of Antimicrobial Compounds

Probiotic bacteria produce a variety of antimicrobial substances that inhibit Salmonella growth. Organic acids such as lactic, acetic, and propionic acids acidify the gut environment which consequently reduces Salmonella viability (Mani-López et al., 2012; Nkosi et al., 2021). Additionally, bacteriocins are synthesized by many probiotics and specifically target Salmonella through membrane pore formation or enzymatic degradation (Simons et al., 2020; Hernández-González et al., 2021). Hydrogen peroxide production from certain probiotics also increases oxidative stress which is detrimental to pathogen survival. For instance, a validated hatchery egg disinfection method combined hydrogen peroxide mist (2–3%), ozone, and UV-C to generate antimicrobial hydroxyl radicals, achieving >5 log CFU/egg reduction of Salmonella enteritidis and typhimurium. The treatment was effective without impairing hatchability and also reduced other pathogens, demonstrating hydrogen peroxide’s strong antimicrobial potential against Salmonella (Dhillon et al., 2025). In vitro and in vivo analyses revealed that Lactiplantibacillus plantarum and Lacticaseibacillus acidophilus strongly inhibited Salmonella Heidelberg (SH), reduced cecal SH loads across all ages, modulated gut microbiota composition, and altered fecal metabolites in ways indicative of reduced oxidative stress, lower intestinal inflammation, and improved gut health, thereby supporting their potential to control SH while reducing antibiotic reliance in broilers (Hoepers et al., 2024). Antimicrobial compounds can lower intestinal pH and directly inhibit Salmonella by disrupting its membrane integrity or metabolic functions (Deng & Wang, 2024).

3.3. Enhancement of Intestinal Barrier Function

The intestinal barrier is a critical defense against enteric pathogens, and probiotics enhance their integrity through multiple mechanisms. Certain probiotics including Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus rhamnosus and Bacillus subtilis can stimulate goblet cells to increase mucin secretion thereby creating a physical mucus layer that traps pathogens and limits direct contact with epithelial cells (Tonetti et al., 2024). Probiotics also increase the production of tight junction proteins, for instance supplementation with Bacillus pumilus or B. subtilis significantly upregulated ileal tight junction proteins (occludin, ZO-1, JAM-2), MUC2, and IL-17F on day 14, with sustained expression in the high-dose B. subtilis group through day 42 (Bilal et al., 2021). These proteins form a connection between gut epithelial cells and prevent pathogens such as Salmonella from passing through. Also, Bacillus licheniformis has been shown to enhance these proteins and improve gut integrity in broilers (Li et al., 2025). Additionally, they also modulate the immune response by increasing anti-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-10 (IL-10) while decreasing pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-6 and IL-8, thus reducing intestinal inflammation and supporting epithelial healing. For instance, different strains of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum have been implicated in inflammatory regulation (Liang et al., 2023; Bu et al., 2023; Filidou et al., 2024).

Furthermore, probiotics promote a balanced gut microbiota that produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), especially butyrate, which serves as an energy source for intestinal cells and enhances tight junction assembly (Naeem & Bourassa, 2025). Several recent broiler studies have reported improved intestinal morphology, including taller villi and deeper crypts, following probiotic supplementation, indicating enhanced nutrient absorption and gut health (Wang et al., 2024; Acharya et al., 2024; Idowu et al., 2025). Together, these effects contribute to a stronger intestinal barrier that reduces pathogen invasion and supports overall poultry performance. Moreover, improved barrier integrity limits pathogen translocation and supports nutrient absorption, which can lead to better growth and health outcomes in poultry.

3.4. Modulation of the Host Immune Response

Probiotics are known to also modulate the immune system by enhancing both innate and adaptive responses to Salmonella challenge. They act by activating macrophages and dendritic cells which leads to increased phagocytosis and antigen presentation (Mazziotta et al., 2023). Additionally, probiotics can enhance the production of immunoglobulin A (IgA) by B cells which neutralizes pathogens, limits their mucosal adherence and promote a balanced immune response capable of resisting infectious pathogens (Guo & Lu-lu Lv, 2023; Zhou et al., 2024). Moreover, anti-inflammatory cytokines like IL-10 and IFN-γ have been increased while pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and IL-6 reduced by probiotics, resulting in balanced immune activation without excessive tissue damage (Raheem et al., 2021). Importantly, probiotic supplementation promotes the maturation of gut-associated lymphoid tissue, improving long-term immunity against recurrent Salmonella exposure (Mazziotta et al., 2023). Some Lactobacillus and Bacillus strains have even been shown to promote the development of gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) and other immune genes that plays a critical role in immune surveillance (Wlaźlak et al., 2023).

3.5. Disruption of Quorum Sensing and Biofilm Formation

Quorum sensing (QS) and biofilm formation are key virulence strategies used by Salmonella to persist in the poultry environment. They form protective communities on surfaces like the intestinal mucosa, eggs, and equipment where they resist cleaning and antimicrobial interventions (Merino et al., 2019). Studies highlight the role of proteobiotics which are small, secreted metabolites from probiotics like Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium spp. that interfere with QS systems particularly with the LuxS/autoinducer-2 pathway (Davares et al., 2022; Salman et al., 2023). These compounds act by downregulating the virulence genes associated with the adhesion, invasion, Type III secretion systems, and biofilm formation in Salmonella Typhimurium and other enteric pathogens (Bayoumi & Griffiths, 2012). In addition, Lactobacillus species have been implicated in the degradation of Salmonella’s autoinducer molecules, suppressing virulence and enhancing pathogen clearance (Colautti et al., 2022).

In poultry, Lactobacillus reuteri and Enterococcus faecium strains, isolated from poultry guts, have been shown to reduce mucin-mediated adhesion and subsequent biofilm formation of antibiotic-resistant Salmonella enterica (Siddique et al., 2021). This suggests that probiotic-derived QS inhibitors can not only limit surface colonization but also prevent the formation of biofilms that serve as long-term reservoirs for contamination. Moreover, combining such probiotic strategies with physical and chemical approaches has been proposed as a comprehensive barrier against persistent Salmonella biofilms in poultry processing environments (Merino et al., 2019). While many existing sanitation methods like disinfectants and heat fail to fully eradicate Salmonella biofilms, integrating QS-disrupting probiotics could fill critical gaps in current control practices.

4. Current Probiotic Strains Used Against Salmonella in Poultry

Probiotics have been studied and applied in poultry production to reduce Salmonella colonization and enhance bird health with various bacterial species and strains demonstrating efficacy, either as single strains or in multi-strain formulations, delivered through feed, water, or encapsulated forms to maximize survival and colonization in the avian gut. Below, we review key probiotic genera with demonstrated anti-Salmonella activity.

4.1. Lactobacillus Species

The genus Lactobacillus remains one of the most widely researched probiotic groups in poultry due to its broad range of beneficial effects on gut health and pathogen control. Species including Lactobacillus plantarum, L. acidophilus, L. reuteri, and L. casei exert antimicrobial actions primarily through the production of lactic acid, hydrogen peroxide, and bacteriocins that create a hostile environment for Salmonella spp. (Dempsey & Corr, 2022; Aleman & Yadav, 2023; Wang et al., 2023). These metabolites lower gut pH and competitively exclude pathogens by occupying adhesion sites on the intestinal epithelium (Tang et al., 2023). L. rhamnosus inhibited the invasion of Caco-2 cells by S. typhimurium through the secretion of lactic acid (van Zyl et al., 2020). Lactobacillus acidophilus and Lactobacillus reuteri, have also been implicated for use in poultry due to their ability to adhere to the intestinal lining, outcompete pathogens for nutrients, and produce antimicrobial substances like lactic acid and bacteriocins which improve antibody production and cell-mediated immunity (Brisbin et al., 2011; El Jeni et al., 2021). In mice, L plantarum has been implicated in enhancing gastrointestinal and reproductive health, supporting immune modulation, and improving intestinal barrier function (Dempsey & Corr, 2022). It has also been implicated in improving the gut microbiome and growth performance of yellow feather broilers (Wang et al., 2023). In vivo and in vitro, supplementation with L. plantarum has consistently demonstrated strong reductions in Salmonella Enteritidis and Typhimurium colonization, with some studies reporting reductions of up to 80% in cecal counts (Muyyarikkandy & Amalaradjou, 2017; Yin et al., 2024; Elabbasy et al., 2025). Notably, L. plantarum also improves gut histomorphology by enhancing villus height and crypt depth, which promotes nutrient absorption and growth performance (Saeed et al., 2025). Compared to conventional antibiotics, L. plantarum strain exhibits potent antimicrobial properties against S. typhimurium, S. cholerascius and S. entertidis in vitro (Unpublished data, 2024).

Other Lactobacillus species such as L. johnsonii have been reported to reduce Salmonella spp in the mucosa, reduce fecal shedding and increase gut microbiota diversity, thereby enhancing the competitive exclusion of pathogens (Arzola-Martínez et al., 2024). L. casei supplementation strengthens tight junction proteins in the gut, reducing epithelial permeability and systemic translocation of Salmonella (Deng et al., 2021; (Tian et al., 2023). Multi-strain probiotic formulations that combine various Lactobacillus species have shown synergistic effects, improving pathogen inhibition and host immune responses more than single-strain treatments (Fijan et al., 2022).

4.2. Bifidobacterium Species

Bifidobacterium species, although less prevalent in poultry probiotics compared to Lactobacillus, are gaining recognition for their immunomodulatory and antimicrobial potential. Strains such as Bifidobacterium breve and B. animalis produce acetic and lactic acids that lower gut pH and secrete bacteriocins effective against Salmonella spp. (Ji et al., 2025). They also enhance gut barrier function by stimulating mucin production and upregulating tight junction proteins, contributing to pathogen exclusion (Du et al., 2025). Bifidobacterium bifidum postbiotics (BbP) protected chickens against S. Pullorum infection by regulating pyroptosis, enhancing intestinal barrier function, modulating gut microbiota, and significantly reducing mortality (Chen et al., 2025). This highlights BbP’s potential as an effective antibiotic alternative in poultry farming. Additionally, B. breve is associated with improved intestinal morphology in poultry such as increase in villus height and goblet cell numbers (Tang et al., 2020) which leads to improved nutrient uptake and bird health. Another study reported that administering Bifidobacterium (B2-2) during late embryogenesis increased bifidobacterial colonization at hatch, reduced Gram-negative bacterial and Enterococcus counts, and enhanced early growth performance in broiler chickens compared to non-treated groups (Rowland et al., 2025).

Several invitro and in vivo studies in other species such as mice, pigs and humans have also revealed antibacterial and antiviral properties of Bifidobacterium. For instance, B. thermophilum was implicated in the inhibition of rotaviral infection by adherence to Caco-2 and HT-29 cells resulting in low viral titers. Also, pretreatment with B. thermophilum led to less epithelial damage of intestinal tissue (Gagnon et al., 2016) while porcine intestinal epitheliocytes pretreated with B. infantis or B. breve showed similar results (Ishizuka et al., 2016; Lim et al., 2020). The growth of vancomycin-resistant S. aureus and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus were also inhibited by certain Bifidobacterium species including B. adolescentis, B. pseudocatenulatum, and B. longum (Yoon et al., 2006, Lim et al., 2020).

4.3. Bacillus Species

Spore-forming Bacillus species such as Bacillus subtilis, B. licheniformis, and B. coagulans are valued in poultry probiotic formulations due to their ability to withstand harsh feed processing conditions and gastric transit (Ogbuewu et al., 2022; Giri et al., 2023). Despite the stability of Bacillus spp., inconclusive results were obtained on the performance of disease-challenged broiler chickens (Ar'Quette et al., 2018; Ahiwe et al., 2021). However, these species secrete antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), enzymes, and organic acids that inhibit Salmonella colonization via competitive exclusion and direct antagonism (Ospina et al., 2025).

Studies have demonstrated that B. subtilis supplementation in broilers can reduce intestinal Salmonella counts, improve immune parameters (including increased IgA secretion), and promote gut morphology improvements such as increased villus height and reduced crypt depth (Katu et al., 2025; Madej et al., 2025; Mohamed et al., 2022; Qiu et al., 2021). Moreover, B. licheniformis exhibited strong antimicrobial and anti-biofilm activities against Salmonella typhimurium by inhibiting its growth, reducing biofilm formation and components, suppressing motility, and interfering with quorum sensing systems (Peng et al., 2025). Another study reported that Bacillus licheniformis and Bacillus subtilis exhibited anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anti-adhesion effects against E. coli and S. Typhimurium in IPEC-J2 cells, suggesting their potential as effective components in probiotic multispecies formulations, despite having minimal impact on paracellular permeability (Palkovicsné Pézsa et al., 2022) . The spore-forming nature of these probiotics also contributes to their long shelf life and viability under storage, making them commercially viable for large-scale poultry production (Popov et al., 2021; Khalid et al., 2022).

4.4. Enterococcus Species

Certain Enterococcus species, including E. faecium which has been implicated in improved body weight and reduced mortality rates in poultry (Khalifa & Ibrahim, 2023). They produce enterocins—bacteriocins with potent activity against Salmonella and other pathogens (Wu et al., 2022). These bacteriocins can disrupt Salmonella membrane integrity, leading to reduced viability (Kasimin et al., 2022). In vivo and invitro studies show that E. faecium supplementation reduces Salmonella intestinal colonization, improves gut health, and modulates immune responses by increasing anti-inflammatory cytokines (Revajová et al., 2022; Huang et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2021). Additionally, Enterococcus probiotics contribute to improved feed conversion ratios and weight gain, enhancing production efficiency (Naeem & Bourassa, 2025).

5. Emerging Probiotic Candidates from Other Hosts Species for Salmonella Control

Exploring probiotic strains derived from non-poultry hosts offers fertile ground for discovering novel interventions against pathogenic bacteria such as Salmonella. One promising candidate is Faecalibacterium prausnitzii which is primarily isolated from human and ruminant gut ecosystems. Although challenging to culture due to strict anaerobic requirements, field trials in pre-weaned dairy calves demonstrated that oral administration of F. prausnitzii significantly reduced severe diarrhea incidence (3.1% vs. 6.8%) and mortality (1.5% vs. 4.4%) while increasing weight gain by approximately 4.4 kg during the pre-weaning period (Foditsch et al. 2015). It also produces anti-inflammatory metabolites including butyrate and salicylic acid which are known to inhibit NF-κB signaling and suppress pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-8, IL-6, and IL-12, while promoting IL-10 production and enhancing gut barrier integrity via upregulation of tight junction proteins like occludin and e-cadherin. In poultry gut microbiome studies, Faecalibacterium abundance has been associated with improved feed conversion and resilience during pathogen challenge, making it a biomarker and potential functional probiotic in broiler context (Ayoola et al., 2023). In addition, other commensal anaerobes in the Clostridiales order such as Oscillibacter spp., and Megamonas spp. have repeatedly been associated with reduced Salmonella shedding and enhanced gut stability in poultry, with F. prausnitzii emerging as a biomarker species in vaccinated layers demonstrating strong resistance to Salmonella Enteritidis colonization (Jan et al., 2022).

Clostridium butyricum is also a potential probiotic in poultry as it has been widely used in swine and human clinical settings for its butyrate-producing and gut barrier–enhancing properties. In laying hens, dietary supplementation with C. butyricum and butyric acid derivatives improved eggshell thickness, lowered pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-8, IL-1β) and modulated ovarian immune function, suggesting systemic benefits beyond the gut (Wang et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2023). It has also demonstrated clear efficacy in broilers since supplementation reduced cecal and systemic S. Enteritidis burdens, decreased inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-8, IFN-γ, TNF-α), and downregulated TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling, while improving tight-junction protein expression and microbial alpha diversity in the gut (Li et al., 2023). Although direct trials against Salmonella in poultry remain sparse, related studies reveal that combination supplementation of C. butyricum in multispecies probiotic formulations effectively reduces Clostridium perfringens, E. coli, and enhances beneficial microbial populations, pointing toward a broader protective ecological effect (Mekonnen et al., 2024).

Environmental isolates from fermented foods or poultry caeca microbiota also represents a promising untapped source. A recent animal microbiome meta-analysis identified genera such as Caloramator, DA101 (Ruminococcaceae), Faecalibacterium, Parabacteroides, and Solibacillus as candidate next-generation probiotics negatively associated with Campylobacter, and by extension potentially effective against Salmonella via competitive exclusion and immune modulation pathways (Ayoola et al., 2023). Notably, isolates of Lactobacillus casei, Ligilactobacillus salivarius, and Lactobacillus plantarum sourced from Tibetan kefir and fermented meats have demonstrated prophylactic efficacy against S. pullorum in chicks—reducing mortality to zero, improving growth, elevating cecal Lactobacillus counts, and boosting sIgA and IL-4 while suppressing TNF-α and IFN-γ responses (Chen et al., 2020). Other core cecal taxa identified across commercial broiler flocks—including Eisenbergiella, Intestinimonas, Subdoligranulum, Faecalibacterium, and Blautia—are associated with butyrate production, competitive exclusion of pathogens, and overall gut resilience, marking them as candidate next-generation probiotics. Moreover, complementary strains such as Enterococcus faecium, isolated even from poultry feces, have shown efficacy in reducing Salmonella colonization and enhancing immune markers when used in multi-strain formulations (Buahom et al., 2023).

Furthermore, recent studies have begun to spotlight microbial strains originally isolated from non-poultry hosts or environmental niches that exhibit compelling anti-Salmonella and gut health-promoting properties in poultry. For instance, Mix10 consortium derived from feral chicken ceca, which includes Olsenella sp., Megamonas funiformis, Pseudoflavonifractor sp., Faecalicoccus pleomorphus, and others significantly reduced S. Typhimurium colonization and curtailed expression of pro-inflammatory mediators including NFKB1, MAPKs, and IRFs, while supporting anti-inflammatory immune modulation in gnotobiotic and conventional chick models (Wongkuna et al., 2024).

Collectively, these findings support a promising direction for probiotic discovery as leveraging strains from diverse hosts and environments such as human-derived F. prausnitzii, swine-adapted C. butyricum, feral chicken cecal consortia, and isolates from fermented foods—may yield probiotic candidates with robust anti-Salmonella activity, improved gut barrier function, and immunomodulatory capacity. Rigorous validation in poultry-specific challenge experiments including colonization stability, metabolic profiling like SCFA production, immune outcomes, and ecological impact will be essential to translate these candidates into practical, safe, and effective probiotic tools for poultry health management.

6. Challenges in Probiotic Use in Poultry

Long-term probiotic use in poultry production presents complex dynamics, particularly regarding horizontal gene transfer (HGT) and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) mitigation. Probiotics contribute to reducing pathogen load via competitive exclusion mechanisms by occupying mucosal binding sites, competing for nutrients, and producing antimicrobial metabolites such as lactic acid and bacteriocins suppressing the population of AMR-carrying pathogens (Chandrasekaran et al., 2024), consequently reducing the frequency of gene exchange events within the gut ecosystem. Moreover, the acidification of the gastrointestinal tract through organic acid production creates an inhospitable environment for plasmid stability and conjugative transfer, as certain resistance plasmids exhibit reduced stability under acidic or nutrient-limited conditions (Ott & Mellata, 2024). Additionally, some probiotic strains interfere with quorum sensing—disrupting bacterial communication systems that regulate gene expression and plasmid conjugation, thereby limiting conjugative plasmid transfer events (Salman et al., 2023). Enhanced gut barrier integrity and mucosal immunity, particularly the stimulation of secretory IgA, further inhibit interactions that facilitate gene transfer among pathogenic bacteria (Zhang et al., 2018).

However, recent studies emphasize that long-term administration of probiotics can induce unintended ecological shifts within the gut microbiota. Persistent use of a single probiotic strain may lead to its dominance, suppressing beneficial commensals and reducing overall microbial diversity, which could increase susceptibility to opportunistic infections (Swenor & Agarwal, 2020). Furthermore, probiotics that are not thoroughly characterized may carry antimicrobial resistance genes located on mobile genetic elements, posing risks of horizontal gene transfer to resident or transient pathogens (Dongre et al., 2025). A comprehensive metagenomic analysis of commercial poultry probiotics revealed the presence of diverse ARGs including fluoroquinolone, macrolide, and aminoglycoside resistance determinants such as aadK, AAC(6')-Ii and multiple drug-resistance genes (vmlR, ykkC, ykkD, msrC, clbA, eatAv), highlighting concerns about inadvertent resistome enrichment, even in the absence of observable resistance expansion over a 60-day period (Kerek et al., 2024). Additionally, the efficacy of probiotics under pathogen challenge conditions appears highly context specific. For instance, trials with Bacillus subtilis QST713 in broilers infected with Clostridium perfringens demonstrated improvements in growth performance and gut barrier integrity (Sun et al., 2024), but the outcomes may significantly be influenced by the challenge model, strain specificity, and administration route. Similarly, invitro and in-vivo evaluations of dual-strain probiotics across multiple broiler flocks revealed variable efficacy in mitigating mild necrotic enteritis, underscoring the necessity of strain-specific optimization (van der Klein et al., 2024; Buiatte et al., 2023). Challenges also persist in probiotic viability during processing and delivery; a recent study comparing freeze-dried and spray-dried formulations of lactic acid bacteria including Enterococcus faecium, Ligilactobacillus salivarius, Pediococcus acidilactici) demonstrated high survivability (>94%) and beneficial effects on gut morphology, yet strain-dependent variability in gastric resilience and colonization capability was evident (Buahom et al., 2023).

Beyond individual strain concerns, broader ecological implications must be considered. While probiotics are intended to stabilize gut health and reduce pathogen shedding, their long-term impacts on the gut microbial community and ARG dynamics are not fully understood. Systematic reviews indicate that probiotic supplementation can inconsistently affect AMR gene reservoirs, with outcomes influenced by baseline microbial diversity, host factors, and environmental variables (Radovanovic et al., 2023; John et al., 2024; Shen et al., 2024). Furthermore, the baseline AMR burden in different production systems (conventional, antibiotic-free, organic) varies greatly, complicating the uniform application of probiotic strategies across diverse farming contexts (Mak et al., 2022; Soundararajan et al., 2022).

Consequently, these findings underscore that although probiotics remain a promising alternative to antibiotic growth promoters, issues related to strain safety, ARG carriage, formulation viability, challenge-specific efficacy, and ecological consequences require continuous monitoring and rigorous evaluation within real-world production environments.

7. Future Directions in Probiotic Application for Poultry

To overcome current challenges and optimize the sustainable use of probiotics in poultry production, adopting a multidisciplinary approach that integrates advanced molecular tools, targeted application strategies, and comprehensive field validation is expedient. One of the foremost priorities is the integration of microbiome profiling to guide precision probiotic interventions. High-throughput sequencing technologies such as 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing and shotgun metagenomics, can provide detailed insights into the baseline gut microbiota composition and functional potential of different poultry populations (Lyte et al., 2025). Such data will enable the development of tailored probiotic formulations that complement the existing microbiota, thereby enhancing colonization efficiency and functional efficacy.

Beyond compositional profiling, the use of genomics and metabolomics for strain selection and functional characterization is essential to ensure safety and efficacy. Whole-genome sequencing of candidate strains can identify beneficial traits, such as bacteriocin production, adhesion factors, and immunomodulatory properties, while simultaneously screening for the absence of virulence factors and mobile antimicrobial resistance genes (Wang, Liang, et al., 2021; Peña et al., 2024). Metabolomic analyses can further unravel the metabolic outputs of probiotic strains, such as short-chain fatty acids and organic acids. In addition to conventional probiotics, emerging biotic strategies such as synbiotics (probiotic-prebiotic combinations), paraprobiotics (non-viable inactivated probiotics), and postbiotics (metabolites and cell components derived from probiotics) are potential complements or alternative approaches (Martyniak et al., 2021). These next-generation formulations may help to overcome some of the limitations associated with strain viability and colonization while retaining functional benefits such as pathogen inhibition, immune modulation, and gut barrier enhancement. To ensure reproducibility and translational applicability, there is a pressing need to standardize efficacy testing protocols and develop robust regulatory frameworks that govern probiotic use in poultry (Waheed et al., 2024). Standardization should encompass not only strain identification and safety evaluation but also functional performance metrics under controlled and field conditions.

Furthermore, the translation of laboratory findings to real-world applications necessitates long-term, large-scale field trials across diverse production systems and geographic regions. Such trials are critical for capturing the complex interactions between probiotics, host genetics, management practices, environmental factors, and the farm-specific microbial ecosystem (Brooks & Alper, 2021). Data generated from these long-term studies will be invaluable for refining probiotic formulations, informing best practices, and embedding probiotic use within comprehensive antimicrobial resistance mitigation frameworks aligned with the One Health approach.

8. Conclusions

Probiotic interventions offer a promising alternative to antibiotics for mitigating Salmonella infections in poultry with growing scientific evidence supporting their role in improving gut health, enhancing immunity, and reducing pathogen colonization. Moreover, while strains like Lactobacillus, Bacillus and Bifidobacterium have shown consistent benefits, emerging candidates from other animal hosts could offer broader or more targeted effects particularly in the presence of zoonotic infections like Salmonella. However, the efficacy of probiotics depends heavily on strain selection, dosage, administration route, and environmental conditions. In addition, significant challenges regarding probiotic application in poultry remain, including variability in outcomes across studies, lack of standardized regulations, and limited understanding of host-microbe interactions in diverse poultry production systems. Future research should focus on the development of next-generation probiotics, better characterization of strain-specific actions, and integration with other health-promoting strategies like phytobiotics and prebiotics.

It is important to optimize probiotic use as it holds great potential not only for improving poultry health and productivity but also for enhancing food safety and addressing global concerns related to antibiotic resistance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and original draft preparation, O.D.A.; reviewing, editing, and supervision, S.N.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by USDA-NIFA, grant number XXX.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abreu, R.; Semedo-Lemsaddek, T.; Cunha, E.; Tavares, L.; Oliveira, M. Antimicrobial Drug Resistance in Poultry Production: Current Status and Innovative Strategies for Bacterial Control. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, A.; Devkota, B.; Basnet, H. B.; Barsila, S. R. Effect of different synbiotic administration methods on growth, carcass characteristics, ileum histomorphometry, and blood biochemistry of Cobb-500 broilers. Veterinary World 2024, 1238–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzola-Martínez, L.; Ravi, K.; Huffnagle, G. B.; Lukacs, N. W.; Fonseca, W. Lactobacillus johnsonii and host communication: insight into modulatory mechanisms during health and disease. Frontiers in Microbiomes 2024, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoola, M. B.; Pillai, N.; Nanduri, B.; Rothrock, M. J.; Ramkumar, M. Predicting foodborne pathogens and probiotics taxa within poultry-related microbiomes using a machine learning approach. Animal Microbiome 2023, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayoumi, M. A.; Griffiths, M. W. In vitro inhibition of expression of virulence genes responsible for colonization and systemic spread of enteric pathogens using Bifidobacterium bifidum secreted molecules. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2012, 156, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, M.; Si, W.; Barbe, F.; Chevaux, E.; Sienkiewicz, O.; Zhao, X. Effects of novel probiotic strains of Bacillus pumilus and Bacillus subtilis on production, gut health, and immunity of broiler chickens raised under suboptimal conditions. Poultry Science 2021, 100, 100871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S. M.; Alper, H. S. Applications, challenges, and needs for employing synthetic biology beyond the lab. Nature Communications 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yi, H. Bacteriocin-Producing Lactiplantibacillus plantarum YRL45 Enhances Intestinal Immunity and Regulates Gut Microbiota in Mice. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3437–3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buahom, J.; Siripornadulsil, S.; Sukon, P.; Sooksawat, T.; Siripornadulsil, W. Survivability of freeze- and spray-dried probiotics and their effects on the growth and health performance of broilers. Veterinary World 2023, 1849–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buiatte, V.; Schultheis, M.; Lorenzoni, A. G. Deconstruction of a multi-strain Bacillus-based probiotic used for poultry: an in vitro assessment of its individual components against C. perfringens. BMC Research Notes 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, October 4). About Salmonella Infection. Salmonella Infection (Salmonellosis). Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/about/index.html.

- Chen, C.; Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Xie, Y.; Xiong, L.; Liu, H.; Wang, F. Effects of a probiotic on the growth performance, intestinal flora, and immune function of chicks infected with Salmonella pullorum. Poultry Science 2020, 99, 5316–5323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhu, F.; Yu, G.; Peng, N.; Li, X.; Ge, M.; Yang, L.; Dong, W. Bifidobacterium bifidum Postbiotics Prevent Salmonella Pullorum Infection in Chickens by Modulating Pyroptosis and Enhancing Gut Health. Poultry Science 2025, 104, 104968–104968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colautti, A.; Orecchia, E.; Comi, G.; Iacumin, L. Lactobacilli, a Weapon to Counteract Pathogens through the Inhibition of Their Virulence Factors. Journal of Bacteriology 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, M. Shaping the Future of Probiotics and Prebiotics. Trends in Microbiology 2021, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davares, A. K. L.; Arsene, M. M. J.; Viktorovna, P. I.; Vyacheslavovna, Y. N.; Vladimirovna, Z. A.; Aleksandrovna, V. E.; Nikolayevich, S. A.; Nadezhda, S.; Anatolievna, G. O.; Nikolaevna, S. I.; Sergueïevna, D. M. Quorum-Sensing Inhibitors from Probiotics as a Strategy to Combat Bacterial Cell-to-Cell Communication Involved in Food Spoilage and Food Safety. Fermentation 2022, 8, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, E.; Corr, S. C. Lactobacillus spp. for Gastrointestinal Health: Current and Future Perspectives. Frontiers in Immunology 2022, 13, 840245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, L.; Wang, S. Colonization resistance: the role of gut microbiota in preventing Salmonella invasion and infection. Gut Microbes 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Z.; Han, D.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Yan, X.; Wang, S.; Liu, X.; Song, W.; Ma, Y. Lactobacillus casei protects intestinal mucosa from damage in chicks caused by Salmonella pullorum via regulating immunity and the Wnt signaling pathway and maintaining the abundance of gut microbiota. Poultry Science 2021, 100, 101283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, H. K.; Hasani, M.; Zai, B.; Yip, K.; Warriner, L. J.; Mutai, I.; Wang, B.; Clark, M.; Bhandare, S.; Warriner, K. Inactivation of Salmonella and avian pathogens on hatchery eggs using gas phase hydroxyl-radical process vs formaldehyde fumigation: Efficacy, hatching performance and grow-out of Chickens. Poultry Science 2025, 104, 105023–105023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Liu, M.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Ge, S.; Gao, H.; Zhang, M. Bifidobacterium animalis Supplementation Improves Intestinal Barrier Function and Alleviates Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhea in Mice. Foods 2025, 14, 1704–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elabbasy, M. T.; Kishawy, A. T. Y.; Abdelaziz, W. S.; Hassan, A. A.; Nada, H. S.; Elbhnsawy, R. A.; Shosha, A. M.; Ibrahim, D.; Eldemery, F.; Atwa, S. A. E.; Sherief, W. R. I. A.; El-Shetry, E. S.; Saleh, A. A.; Ibrahim, D. Optimistic effects of dual nano-encapsulated probiotics on breeders laying performance, intestinal barrier functions, immunity and resistance against Salmonella Typhimurium challenge. Scientific Reports 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fijan, S.; Kocbek, P.; Steyer, A.; Vodičar, P. M.; Strauss, M. The Antimicrobial Effect of Various Single-Strain and Multi-Strain Probiotics, Dietary Supplements or Other Beneficial Microbes against Common Clinical Wound Pathogens. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filidou, E.; Kandilogiannakis, L.; Shrewsbury, A.; Kolios, G.; Kotzampassi, K. Probiotics: Shaping the gut immunological responses. World Journal of Gastroenterology 2024, 30, 2096–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foditsch, C.; Pereira, R. V. V.; Ganda, E. K.; Gomez, M. S.; Marques, E. C.; Santin, T.; Bicalho, R. C. Oral Administration of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii Decreased the Incidence of Severe Diarrhea and Related Mortality Rate and Increased Weight Gain in Preweaned Dairy Heifers. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0145485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca, A.; Kenney, S.; Syoc, E. V.; Bierly, S.; Dini-Andreote, F.; Silverman, J.; Boney, J.; Ganda, E. Investigating Antibiotic Free Feed Additives for Growth Promotion in Poultry - Effects on Performance and Microbiota. Poultry Science 2024, 103604–103604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-González, J. C.; Martínez-Tapia, A.; Lazcano-Hernández, G.; García-Pérez, B. E.; Castrejón-Jiménez, N. S. Bacteriocins from Lactic Acid Bacteria. A Powerful Alternative as Antimicrobials, Probiotics, and Immunomodulators in Veterinary Medicine. Animals 2021, 11, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoepers, P. G.; Lucas, P.; Almeida, H. O.; Martins, M. M.; Dias, R.; Dreyer, C. T.; Aburjaile, F. F.; Sommerfeld, S.; Ariston, V.; Fonseca, B. B. Harnessing Probiotics Capability to Combat Salmonella Heidelberg and Improve Intestinal Health in Broilers. Poultry Science 2024, 103739–103739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Rong, X.; Liu, M.; Liang, Z.; Geng, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Ji, C.; Zhao, L.; Ma, Q. Intestinal Mucosal Immunity-Mediated Modulation of the Gut Microbiome by Oral Delivery of Enterococcus faecium Against Salmonella Enteritidis Pathogenesis in a Laying Hen Model. Frontiers in Immunology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idowu, P. A.; Mpofu, T. J.; Magoro, A. M.; Modiba, M. C.; Nephawe, K. A.; Mtileni, B. Impact of probiotics on chicken gut microbiota, immunity, behavior, and productive performance—a systematic review. Frontiers in Animal Science 2025, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, T.-R.; Lin, C.-S.; Wang, S.-Y.; Yang, W.-Y. Cytokines and cecal microbiome modulations conferred by a dual vaccine in Salmonella-infected layers. Poultry Science 2022, 102, 102373–102373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Li, T.; Ma, B.; Wang, R. A Bifidobacterium Strain with Antibacterial Activity, Its Antibacterial Characteristics and In Vitro Probiotics Studies. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, D.; Michael, D.; Dabcheva, M.; Hulme, E.; Illanes, J.; Webberley, T.; Wang, D.; Plummer, S. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study assessing the impact of probiotic supplementation on antibiotic induced changes in the gut microbiome. Frontiers in Microbiomes 2024, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasimin, M. E.; Shamsuddin, S.; Molujin, A. M.; Sabullah, M. K.; Gansau, J. A.; Jawan, R. Enterocin: Promising Biopreservative Produced by Enterococcus sp. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katu, J. K.; Tóth, T.; Ásványi, B.; Hatvan, Z.; Varga, L. Effect of Fermented Feed on Growth Performance and Gut Health of Broilers: A Review. Animals 2025, 15, 1957–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerek, Á.; Román, I. L.; Szabó, Á.; Papp, M.; Bányai, K.; Kardos, G.; Kaszab, E.; Bali, K.; Makrai, L.; Jerzsele, Á. Comprehensive Metagenomic Analysis of Veterinary Probiotics in Broiler Chickens. Animals 2024, 14, 1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, A.; Khalid, F.; Mahreen, N.; Hussain, S. M.; Shahzad, M. M.; Khan, S.; Wang, Z. Effect of Spore-Forming Probiotics on the Poultry Production: A Review. Food Science of Animal Resources 2022, 42, 968–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, A.; Ibrahim, M. Enterococcus faeciumfrom chicken feces improves chicken immune response and alleviatesSalmonellainfections: a pilot study. Journal of Animal Science 2023, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, A.; Shehzad, A.; Niazi, S.; Zahid, A.; Ashraf, W.; Iqbal, M. W.; Rehman, A.; Riaz, T.; Aadil, R. M.; Khan, I.; Özogul, F.; Rocha, J. M.; Esatbeyoglu, T.; Korma, S. A. Probiotics: Mechanism of action, Health Benefits and Their Application in Food Industries. Frontiers in Microbiology 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T. X.; Eom, J.; Kim, H. K.; Beak, S. H.; Jo, A. R.; Kim, I. H. Dual effects of dietary protein restriction and probiotic supplementation on broiler performance and fecal gas emission. Poultry Science 2025, 104, 105416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, W.; Zhao, L.; Li, Y.; He, W.; Ding, K.; Cao, P. Characterization and Assessment of Native Lactic Acid Bacteria from Broiler Intestines for Potential Probiotic Properties. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 749–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Long, L.; Jin, X.; Li, Y.; Wu, Q.; Chen, X.; Geng, Z.; Zhang, C. Effects of Clostridium butyricum on growth performance, meat quality, and intestinal health of broilers. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, L.; Zhao, Z.; He, Z.; Li, S. Lactiplantibacillus plantarum ELF051 Alleviates Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhea by Regulating Intestinal Inflammation and Gut Microbiota. Probiotics and Antimicrobial Proteins 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyte, J. M.; Seyoum, M. M.; Ayala, D.; Kers, J. G.; Caputi, V.; Johnson, T.; Zhang, L.; Rehberger, J.; Zhang, G.; Dridi, S.; Hale, B.; De Oliveira, J. E.; Grum, D.; Smith, A. H.; Kogut, M.; Ricke, S. C.; Ballou, A.; Potter, B.; Proszkowiec-Weglarz, M. Do we need a standardized 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing analysis protocol for poultry microbiota research? Poultry Science 2025, 104, 105242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madej, J. P.; Woźniak-Biel, A.; Gaweł, A.; Bobrek, K. Boosting Broiler Health and Productivity: The Impact of in ovo Probiotics and Early Posthatch Feeding with Bacillus subtilis, Lactobacillus fermentum, and Enterococcus faecium. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1219–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mak, P. H. W.; Rehman, M. A.; Kiarie, E. G.; Topp, E.; Diarra, M. S. Production systems and important antimicrobial resistant-pathogenic bacteria in poultry: a review. Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani-López, E.; García, H. S.; López-Malo, A. Organic acids as antimicrobials to control Salmonella in meat and poultry products. Food Research International 2012, 45, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martyniak, A.; Medyńska-Przęczek, A.; Wędrychowicz, A.; Skoczeń, S.; Tomasik, P. J. Prebiotics, Probiotics, Synbiotics, Paraprobiotics and Postbiotic Compounds in IBD. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazziotta, C.; Tognon, M.; Martini, F.; Torreggiani, E.; Rotondo, J. C. Probiotics mechanism of action on immune cells and beneficial effects on human health. Cells 2023, 12, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, Y. T.; Savini, F.; Indio, V.; Seguino, A.; Giacometti, F.; Serraino, A.; Candela, M.; De Cesare, A. Systematic review on microbiome-related nutritional interventions interfering with the colonization of foodborne pathogens in broiler gut to prevent contamination of poultry meat. Poultry Science 2024, 103, 103607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, L.; Procura, F.; Trejo, F. M.; Bueno, D. J.; Golowczyc, M. A. Biofilm formation by Salmonella sp. in the poultry industry: Detection, control and eradication strategies. Food Research International 2019, 119, 530–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M., Gerval, A., Hansen, J., & Grossen, G. (2022, August 1). Poultry Expected To Continue Leading Global Meat Imports as Demand Rises | Economic Research Service. Usda.gov. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2022/august/poultry-expected-to-continue-leading-global-meat-imports-as-demand-rises.

- Mohamed, T.; Sun, W.; Bumbie, G. Z.; Elokil, A. A.; Mohammed, K. A.; Rao, Z.; Hu, P.; Wu, L.; Tang, Z. Feeding Bacillus subtilis ATCC19659 to Broiler Chickens Enhances Growth Performance and Immune Function by Modulating Intestinal Morphology and Cecum Microbiota. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muyyarikkandy, M. S.; Amalaradjou, M. Lactobacillus bulgaricus, Lactobacillus rhamnosus and Lactobacillus paracasei Attenuate Salmonella Enteritidis, Salmonella Heidelberg and Salmonella Typhimurium Colonization and Virulence Gene Expression In Vitro. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2017, 18, 2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naeem, M.; Bourassa, D. Optimizing Poultry Nutrition to Combat Salmonella: Insights from the Literature. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2612–2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M.; Bourassa, D. Probiotics in Poultry: Unlocking Productivity Through Microbiome Modulation and Gut Health. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, M.; Zhao, L.; Gong, S.; Liu, X.; Zheng, C.; Jiao, J.; Wang, F.; Wang, L. Oral administration of probiotic spores-based biohybrid system for efficient attenuation of Salmonella Typhimurium-induced colitis. Journal of Nanobiotechnology 2025, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkosi, D. V.; Bekker, J. L.; Hoffman, L. C. The Use of Organic Acids (Lactic and Acetic) as a Microbial Decontaminant during the Slaughter of Meat Animal Species: A Review. Foods 2021, 10, 2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ospina, A.; Varón-López, M.; Peñuela-Sierra, L. M. Competing microorganisms with exclusion effects against multidrug-resistant Salmonella Infantis in chicken litter supplemented with growth-promoting antimicrobials. Veterinary World 2025, 1127–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palkovicsné Pézsa, N.; Kovács, D.; Rácz, B.; Farkas, O. Effects of Bacillus licheniformis and Bacillus subtilis on Gut Barrier Function, Proinflammatory Response, ROS Production and Pathogen Inhibition Properties in IPEC-J2—Escherichia coli/Salmonella Typhimurium Co-Culture. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroso, A. A.; Lee, M. D.; Maurer, J. J. Strength Lies in Diversity: How Community Diversity Limits Salmonella Abundance in the Chicken Intestine. Frontiers in Microbiology 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, N.; Lafuente, I.; Sevillano, E.; Feito, J.; Contente, D.; Muñoz-Atienza, E.; Cintas, L. M.; Hernández, P. E.; Borrero, J. Screening and Genomic Profiling of Antimicrobial Bacteria Sourced from Poultry Slaughterhouse Effluents: Bacteriocin Production and Safety Evaluation. Genes 2024, 15, 1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Xu, H.; Zhang, M.; Xu, B.; Dai, B.; Yang, C. The Effects of Bacillus licheniformis on the Growth, Biofilm, Motility and Quorum Sensing of Salmonella typhimurium. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, I.; Algburi, A.; Празднoва, Е. В.; Mazanko, M. S.; Elisashvili, V.; Bren, A. B.; Chistyakov, V. A.; Tkacheva, E. V.; Trukhachev, V.; Дoнник, И. М.; Ivanov, Y. A.; Rudoy, D.; Ermakov, A.; Weeks, R.; Chikindas, M. L. A Review of the Effects and Production of Spore-Forming Probiotics for Poultry. Animals 2021, 11, 1941–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punchihewage-Don, A. J.; Schwarz, J.; Diria, A.; Bowers, J.; Parveen, S. Prevalence and antibiotic resistance of Salmonella in organic and non-organic chickens on the Eastern Shore of Maryland, USA. Frontiers in Microbiology 2023, 14, 1272892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, K.; Li, C.; Wang, J.; Qi, G.; Gao, J.; Zhang, H.; Wu, S. Effects of Dietary Supplementation With Bacillus subtilis, as an Alternative to Antibiotics, on Growth Performance, Serum Immunity, and Intestinal Health in Broiler Chickens. Frontiers in Nutrition 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radovanovic, M.; Kekic, D.; Gajic, I.; Kabic, J.; Jovicevic, M.; Kekic, N.; Opavski, N.; Ranin, L. Potential influence of antimicrobial resistance gene content in probiotic bacteria on the gut resistome ecosystems. Frontiers in Nutrition 2023, 10, 1054555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raheem, A.; Liang, L.; Zhang, G.; Cui, S. Modulatory Effects of Probiotics During Pathogenic Infections With Emphasis on Immune Regulation. Frontiers in Immunology 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revajová, V.; Benková, T.; Karaffová, V.; Levkut, M.; Selecká, E.; Dvorožňáková, E.; Ševčíková, Z.; Herich, R.; Levkut, M. Influence of Immune Parameters after Enterococcus faecium AL41 Administration and Salmonella Infection in Chickens. Life 2022, 12, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, M. C.; Teague, K. D.; Forga, A. J.; Higuita, J.; Coles, M. E.; Hargis, B. M.; Vuong, C. N.; Graham, D. Evaluation of the Effect of In Ovo Applied Bifidobacteria and Lactic Acid Bacteria on Enteric Colonization by Hatchery-Associated Opportunistic Pathogens and Early Performance in Broiler Chickens. Poultry 2025, 4, 15–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdeva, A.; Tomar, T.; Malik, T.; Bains, A.; Karnwal, A. Exploring probiotics as a sustainable alternative to antimicrobial growth promoters: mechanisms and benefits in animal health. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2025, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M.; Al-Khalaifah, H.; Al-Nasser, A.; Al-Surrayai, T. Feeding the future: A new potential nutritional impact of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum and its promising interventions in future for poultry industry. Poultry Science 2025, 104, 105130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salman, M. K.; Abuqwider, J.; Mauriello, G. Anti-Quorum Sensing Activity of Probiotics: The Mechanism and Role in Food and Gut Health. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaji, S.; Selvaraj, R. K.; Shanmugasundaram, R. Salmonella Infection in Poultry: A Review on the Pathogen and Control Strategies. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Jin, H.; Zhao, F.; Kwok, L.; Zhao, Z.; Sun, Z. Short-term probiotic supplementation affects the diversity, genetics, growth, and interactions of the native gut microbiome. IMeta 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddique, A.; Azim, S.; Ali, A.; Adnan, F.; Arif, M.; Imran, M.; Ganda, E.; Rahman, A. Lactobacillus reuteri and Enterococcus faecium from Poultry Gut Reduce Mucin Adhesion and Biofilm Formation of Cephalosporin and Fluoroquinolone-Resistant Salmonella enterica. Animals 2021, 11, 3435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, A.; Alhanout, K.; Duval, R. E. Bacteriocins, Antimicrobial Peptides from Bacterial Origin: Overview of Their Biology and Their Impact against Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soundararajan, M.; Marincola, G.; Liong, O.; Marciniak, T.; Wencker, F. D. R.; Hofmann, F.; Schollenbruch, H.; Kobusch, I.; Linnemann, S.; Wolf, S. A.; Helal, M.; Semmler, T.; Walther, B.; Schoen, C.; Nyasinga, J.; Revathi, G.; Boelhauve, M.; Ziebuhr, W. Farming Practice Influences Antimicrobial Resistance Burden of Non-Aureus Staphylococci in Pig Husbandries. Microorganisms 2022, 11, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, P.; Zhang, K.; Bai, S.; Wang, J.; Zeng, Q.; Peng, H.; Mu, Y.; Xuan, Y.; Li, S.; Ding, X. Probiotic Bacillus subtilis QST713 improved growth performance and enhanced the intestinal health of yellow-feather broilers challenged with Coccidia and Clostridium perfringens. Poultry Science 2024, 103, 104319–104319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, D.; Li, Z.; Mahmood, T.; Liu, D.; Hu, Y.; Guo, Y. The association between microbial community and ileal gene expression on intestinal wall thickness alterations in chickens. Poultry Science 2020, 99, 1847–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, H.; Huang, W.; Yao, Y.-F. The metabolites of lactic acid bacteria: classification, biosynthesis and modulation of gut microbiota. Microbial Cell 2023, 10, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Zhong, C.; He, Y.; Lu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wei, H.; Tao, X. Preventive of Lacticaseibacillus casei WLCA02 against Salmonella Typhimurium infection via strengthening the intestinal barrier and activating the macrophages. Journal of Functional Foods 2023, 104, 105507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonetti, F. R.; Eguileor, A.; Llorente, C. Goblet cells: guardians of gut immunity and their role in gastrointestinal diseases. EGastroenterology 2024, 2, e100098–e100098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Klein, S. A. S.; Arora, S. S.; Haldar, S.; Dhara, A. K.; Gibbs, K. A dual strain probiotic administered via the waterline beneficially modulates the ileal and cecal microbiome, sIgA and acute phase protein levels, and growth performance of broilers during a dysbacteriosis challenge. Poultry science 2024, 103, 104462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Laan, S.; Breeman, G.; Scherer, L. Animal Lives Affected by Meat Consumption Trends in the G20 Countries. Animals: an open access journal from MDPI 2024, 14, 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waheed, R.; Farooq, A.Z.; Asma, L. Regulatory Considerations for Microbiome-Based Therapeutics. In Human Microbiome; Khurshid, M., Akash, M.S.H., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Dang, G.; Hao, W.; Li, A.; Zhang, H.; Guan, S.; Ma, T. Dietary Supplementation of Compound Probiotics Improves Intestinal Health by Modulated Microbiota and Its SCFA Products as Alternatives to In-Feed Antibiotics. Probiotics and Antimicrobial Proteins 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liang, Q.; Lu, B.; Shen, H.; Liu, S.; Shi, Y.; Leptihn, S.; Li, H.; Wei, J.; Liu, C.; Xiao, H.; Zheng, X.; Liu, C.; Chen, H. Whole-genome analysis of probiotic product isolates reveals the presence of genes related to antimicrobial resistance, virulence factors, and toxic metabolites, posing potential health risks. BMC Genomics 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lin, X.; Gou, Z.; Fan, Q.; Jiang, S. Effects of Clostridium butyricum, Sodium Butyrate, and Butyric Acid Glycerides on the Reproductive Performance, Egg Quality, Intestinal Health, and Offspring Performance of Yellow-Feathered Breeder Hens. Frontiers in Microbiology 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickramasuriya, S. S.; Ault, J.; Ritchie, S.; Gay, C. G.; Lillehoj, H. S. Alternatives to antibiotic growth promoters for poultry: a bibliometric analysis of the research journals. Poultry Science 2024, 103, 103987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wlaźlak, S.; Pietrzak, E.; Biesek, J.; Dunislawska, A. Modulation of the immune system of chickens a key factor in maintaining poultry production—a review. Poultry Science 2023, 102, 102785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wongkuna, S.; Ambat, A.; Ghimire, S.; Mattiello, S. P.; Maji, A.; Kumar, R.; Antony, L.; Chankhamhaengdecha, S.; Janvilisri, T.; Nelson, E.; Doerner, K. C.; More, S.; Behr, M.; Scaria, J. Identification of a microbial sub-community from the feral chicken gut that reduces Salmonella colonization and improves gut health in a gnotobiotic chicken model. Microbiology Spectrum 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Pang, X.; Wu, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X. Enterocins: Classification, Synthesis, Antibacterial Mechanisms and Food Applications. Molecules 2022, 27, 2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Lu, Y.; Li, D.; Yan, C.; Jiang, Y.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Du, R.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y. Probiotic mediated intestinal microbiota and improved performance, egg quality and ovarian immune function of laying hens at different laying stage. Frontiers in Microbiology 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, Y.; Peng, H.; Bai, H.; Pei, Z.; Chen, Z.; Ma, C.; Zhu, M.; Li, J.; Li, C.; Gong, Y.; Wang, L.; Teng, L.; Qin, Z.; Zhou, J.; Wei, T.; Liao, Y. Enhancing resistance to Salmonella typhimurium in yellow-feathered broilers: a study of a strain of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum as probiotic feed additives. Frontiers in Microbiology 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, M.; Jia, J.; Zhao, J.; Radebe, S. M.; Yu, Q. The Protective Effect of E. faecium on S. typhimurium Infection Induced Damage to Intestinal Mucosa. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Chen, Y.; Imre, K.; Arslan-Acaröz, D.; Istanbullugil, F. R.; Fang, Y.; Ros, G.; Zhu, K.; Acaröz, U. Mechanisms of probiotic Bacillus against enteric bacterial infections. One Health Advances 2023, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).