Submitted:

16 December 2025

Posted:

18 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

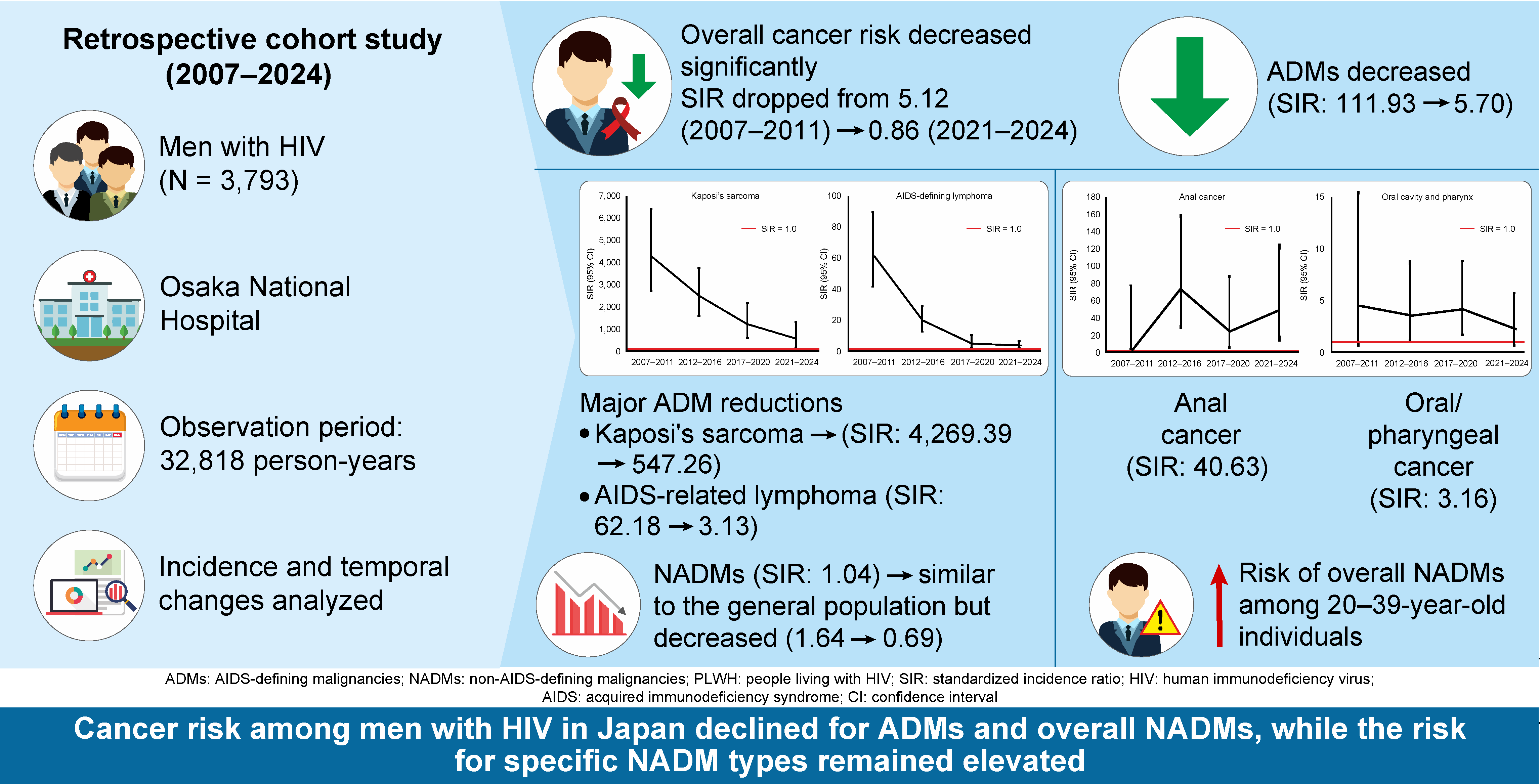

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

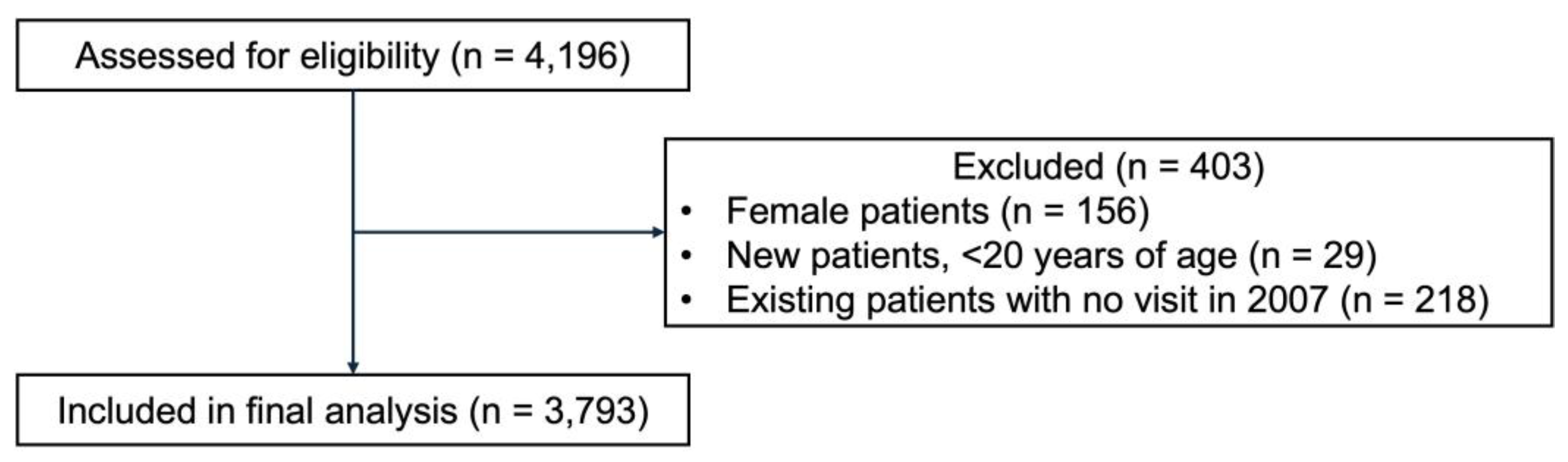

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Population and Period

2.3. Data Sources and Variables

2.4. Statistical Analysis

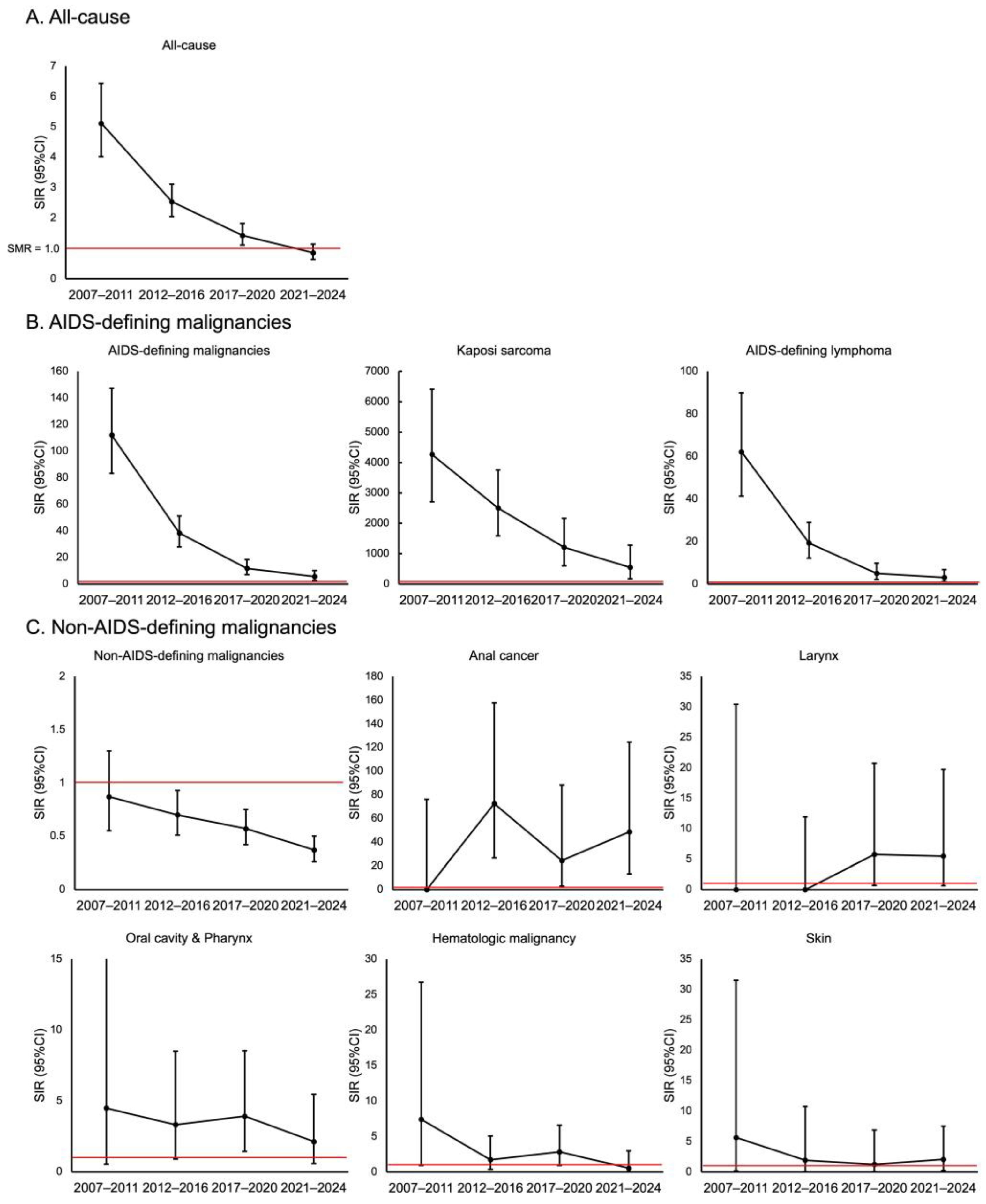

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADM | AIDS-defining malignancy |

| ART | Antiretroviral therapy |

| AIDS | Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CTL | Cytotoxic T lymphocyte |

| EBNA1 | Epstein–Barr virus nuclear antigen 1 |

| EBV | Epstein–Barr virus |

| HBV | Hepatitis B virus |

| HCV | Hepatitis C virus |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| HPV | Human papillomavirus |

| MSM | Men who have sex with men |

| NADM | Non-AIDS-defining malignancy |

| PWH | People with HIV |

| SIR | Standardized incidence ratio |

References

- Tusch, E.; Ryom, L.; Pelchen-Matthews, A.; Mocroft, A.; Elbirt, D.; Oprea, C.; Günthard, H.F.; Staehelin, C.; Zangerle, R.; Suarez, I.; et al. Trends in mortality in people With HIV from 1999 through 2020: a multicohort collaboration. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2024, 79, 1242–1257. [CrossRef]

- Trickey, A.; Sabin, C.A.; Burkholder, G.; Crane, H.; d'Arminio Monforte, A.; Egger, M.; Gill, M.J.; Grabar, S.; Guest, J.L.; Jarrin, I.; et al. Life expectancy after 2015 of adults with HIV on long-term antiretroviral therapy in Europe and North America: a collaborative analysis of cohort studies. Lancet HIV. 2023, 10, e295–e307. [CrossRef]

- Cattelan, A.M.; Mazzitelli, M.; Presa, N.; Cozzolino, C.; Sasset, L.; Leoni, D.; Bragato, B.; Scaglione, V.; Baldo, V.; Parisi, S.G. Changing prevalence of AIDS and non-AIDS-defining cancers in an incident cohort of people living with HIV over 28 years. Cancers (Basel). 2023, 16, 70. [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, L.; Ryom, L.; Bakowska, E.; Wit, F.; Bucher, H.C.; Braun, D.L.; Phillips, A.; Sabin, C.; d'Arminio Monforte, A.; Zangerle, R.; et al. Trends in cancer incidence in different antiretroviral treatment-eras amongst people with HIV. Cancers (Basel). 2023, 15, 3640. [CrossRef]

- Silverberg, M.J.; Lau, B.; Achenbach, C.J.; Jing, Y.; Althoff, K.N.; D'Souza, G.; Engels, E.A.; Hessol, N.A.; Brooks, J.T.; Burchell, A.N.; et al. Cumulative incidence of cancer among persons with HIV in North America: a cohort study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2015, 163, 507–518. [CrossRef]

- Silverberg, M.J.; Chao, C.; Leyden, W.A.; Xu, L.; Tang, B.; Horberg, M.A.; Klein, D.; Quesenberry, C.P., Jr.; Towner, W.J.; Abrams, D.I. HIV infection and the risk of cancers with and without a known infectious cause. AIDS. 2009, 23, 2337–2345.

- Wong, I.K.J.; Grulich, A.E.; Poynten, I.M.; Polizzotto, M.N.; van Leeuwen, M.T.; Amin, J.; McGregor, S.; Law, M.; Templeton, D.J.; Vajdic, C.M.; et al. Time trends in cancer incidence in Australian people living with HIV between 1982 and 2012. HIV Med. 2022, 23, 134–145. [CrossRef]

- Mahale, P.; Engels, E.A.; Coghill, A.E.; Kahn, A.R.; Shiels, M.S. Cancer risk in older persons living with human immunodeficiency virus infection in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 67, 50–57. [CrossRef]

- Robbins, H.A.; Shiels, M.S.; Pfeiffer, R.M.; Engels, E.A. Epidemiologic contributions to recent cancer trends among HIV-infected people in the United States. AIDS. 2014, 28, 881–890. [CrossRef]

- Nagata, N.; Nishijima, T.; Niikura, R.; Yokoyama, T.; Matsushita, Y.; Watanabe, K.; Teruya, K.; Kikuchi, Y.; Akiyama, J.; Yanase, M.; et al. Increased risk of non-AIDS-defining cancers in Asian HIV-infected patients: a long-term cohort study. BMC Cancer. 2018, 18, 1066. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Oshima, K.; Kawano, K.; Tashiro, M.; Kakiuchi, S.; Tanaka, A.; Fujita, A.; Ashizawa, N.; Tsukamoto, M.; Yasuoka, A.; et al. Nationwide longitudinal annual survey of HIV/AIDS referral hospitals in Japan from 1999 to 2021: trend in non-AIDS-defining cancers among individuals infected with HIV-1. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2024, 96, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- The AIDS Surveillance Committee, the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Available online: https://api-net.jfap.or.jp/status/japan/nenpo.html (accessed 11 Nov 2025).

- Mizawa, A.; Nagai, H.; Odawara, T.; Uehira, A.; Yotsumoto, M.; Hagiwara, S.; Tanuma, J.; Okada, S. HIV-associated malignant lymphoma: treatment guidelines Ver. 3.0. (in Japanese) The Journal of AIDS Research. 2016, 18, 92–104.

- Cancer Statistics. Cancer Information Service, National Cancer Center, Japan (National Cancer Registry, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare). Available online: https://ganjoho.jp/reg_stat/statistics/stat/cancer/1_all.html (accessed 11 Nov 2025).

- Shiels, M.S.; Engels, E.A. Evolving epidemiology of HIV-associated malignancies. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS. 2017, 12, 6–11. [CrossRef]

- Haas, C.B.; McGee-Avila, J.K.; Luo, Q.; Pfeiffer, R.M.; Gershman, S.; Cherala, S.; Cohen, C.; Monterosso, A.; Archer, N.; Insaf, T.Z.; et al. Cancer incidence and trends in US adults with HIV. JAMA Oncol. 2025, 11, 855–863. [CrossRef]

- Poizot-Martin, I.; Lions, C.; Allavena, C.; Huleux, T.; Bani-Sadr, F.; Cheret, A.; Rey, D.; Duvivier, C.; Jacomet, C.; Ferry, T.; et al. Spectrum and incidence trends of AIDS- and non-AIDS-defining cancers between 2010 and 2015 in the French Dat'AIDS Cohort. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2021, 30, 554–563. [CrossRef]

- Verdu-Bou, M.; Tapia, G.; Hernandez-Rodriguez, A.; Navarro, J.T. Clinical and therapeutic implications of Epstein-Barr virus in HIV-related lymphomas. Cancers (Basel). 2021, 13, 5534. [CrossRef]

- Park, L.S.; Tate, J.P.; Sigel, K.; Brown, S.T.; Crothers, K.; Gibert, C.; Goetz, M.B.; Rimland, D.; Rodriguez-Barradas, M.C.; Bedimo, R.J.; et al. Association of viral suppression with lower AIDS-defining and non-AIDS-defining cancer incidence in HIV-infected veterans: a prospective cohort study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 87–96. [CrossRef]

- Coghill, A.E.; Shiels, M.S.; Suneja, G.; Engels, E.A. Elevated cancer-specific mortality among HIV-infected patients in the United States. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 2376–2383. [CrossRef]

- Oh, T.K.; Song, K.H.; Heo, E.; Song, I.A. Association between HIV and cancer risk. AIDS. 2025, 39, 1422–1430. [CrossRef]

- Park, B.; Ahn, K.H.; Choi, Y.; Kim, J.H.; Seong, H.; Kim, Y.J.; Choi, J.Y.; Song, J.Y.; Lee, E.; Jun, Y.H.; et al. Cancer Incidence Among Adults With HIV in a Population-Based Cohort in Korea. JAMA Netw. Open. 2022, 5, e2224897. [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, A.A.; Lin, Y.Y.; Damgacioglu, H.; Shiels, M.; Coburn, S.B.; Lang, R.; Althoff, K.N.; Moore, R.; Silverberg, M.J.; Nyitray, A.G.; et al. Recent and projected incidence trends and risk of anal cancer among people with HIV in North America. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2024, 116, 1450–1458. [CrossRef]

- Mazul, A.L.; Hartman, C.M.; Mowery, Y.M.; Kramer, J.R.; White, D.L.; Royse, K.E.; Raychaudhury, S.; Sandulache, V.C.; Ahmed, S.T.; Zevallos, J.P.; et al. Risk and incidence of head and neck cancers in veterans living with HIV and matched HIV-negative veterans. Cancer. 2022, 128, 3310–3318. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Althoff, K.N.; Jing, Y.; Horberg, M.A.; Buchacz, K.; Gill, M.J.; Justice, A.C.; Rabkin, C.S.; Goedert, J.J.; Sigel, K.; et al. Trends in hepatocellular carcinoma incidence and risk among persons with HIV in the US and Canada, 1996–2015. JAMA Netw. Open. 2021, 4, e2037512. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.O.; Lee, J.E.; Lee, S.; Lee, S.H.; Kang, J.S.; Son, H.; Lee, H.; Kim, J. Nationwide population-based incidence of cancer among patients with HIV/AIDS in South Korea. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9974. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.O.; Lee, J.E.; Sim, Y.K.; Lee, S.; Ko, W.S.; Kim, J.; Kang, J.S.; Son, H.; Lee, S.H. Changing trends in the incidence and spectrum of cancers between 1990 and 2021 among HIV-infected patients in Busan, Korea. J. Infect. Chemother. 2023, 29, 571–575. [CrossRef]

- Fukuo, Y.; Shibuya, T.; Ashizawa, K.; Ito, K.; Saeki, M.; Fukushima, H.; Takahashi, M.; Nomura, K.; Okahara, K.; Haga, K.; et al. Plasmablastic lymphoma of the small intestine in an HIV- and EBV-negative patient. Intern. Med. 2021, 60, 2947–2952. [CrossRef]

- Matsui, S.; Ahlers, J.D.; Vortmeyer, A.O.; Terabe, M.; Tsukui, T.; Carbone, D.P.; Liotta, L.A.; Berzofsky, J.A. A model for CD8+ CTL tumor immunosurveillance and regulation of tumor escape by CD4 T cells through an effect on quality of CTL. J. Immunol. 1999, 163, 184–193.

- Piriou, E.; van Dort, K.; Nanlohy, N.M.; van Oers, M.H.; Miedema, F.; van Baarle, D. Loss of EBNA1-specific memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in HIV-infected patients progressing to AIDS-related non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2005, 106, 3166–3174. [CrossRef]

- Palefsky, J.M.; Lee, J.Y.; Jay, N.; Goldstone, S.E.; Darragh, T.M.; Dunlevy, H.A.; Rosa-Cunha, I.; Arons, A.; Pugliese, J.C.; Vena, D.; et al. Treatment of anal high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions to prevent anal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 2273–2282. [CrossRef]

- Stier, E.A.; Clarke, M.A.; Deshmukh, A.A.; Wentzensen, N.; Liu, Y.; Poynten, I.M.; Cavallari, E.N.; Fink, V.; Barroso, L.F.; Clifford, G.M.; et al. International Anal Neoplasia Society's consensus guidelines for anal cancer screening. Int. J. Cancer. 2024, 154, 1694–1702. [CrossRef]

- Simms, K.T.; Hanley, S.J.B.; Smith, M.A.; Keane, A.; Canfell, K. Impact of HPV vaccine hesitancy on cervical cancer in Japan: a modelling study. Lancet Public Health. 2020, 5, e223–e234. [CrossRef]

- Yagi, A.; Ueda, Y.; Kakuda, M.; Nakagawa, S.; Hiramatsu, K.; Miyoshi, A.; Kobayashi, E.; Kimura, T.; Kurosawa, M.; Yamaguchi, M.; et al. Cervical cancer protection in Japan: Where are we? Vaccines (Basel). 2021, 9, 1263. [CrossRef]

- Spence, A.B.; Levy, M.E.; Monroe, A.; Castel, A.; Timpone, J.; Horberg, M.; Adams-Campbell, L.; Kumar, P. Cancer incidence and cancer screening practices among a cohort of persons receiving HIV care in Washington, DC. J. Community Health. 2021, 46, 75–85. [CrossRef]

- Chiao, E.Y.; Hartman, C.M.; El-Serag, H.B.; Giordano, T.P. The impact of HIV viral control on the incidence of HIV-associated anal cancer. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2013, 63, 631–638. [CrossRef]

- Safreed-Harmon, K.; Anderson, J.; Azzopardi-Muscat, N.; Behrens, G.M.N.; d'Arminio Monforte, A.; Davidovich, U.; Del Amo, J.; Kall, M.; Noori, T.; Porter, K.; et al. Reorienting health systems to care for people with HIV beyond viral suppression. Lancet HIV. 2019, 6, e869–e877. [CrossRef]

| Variable | Value |

| Total duration of follow-up for the whole cohort (person-years) | 32,818 |

| Age at enrollment (years), median (IQR) | 36.3 (29.7–44.9) |

| Japanese nationality, n (%) | 3553 (93.7) |

| CD4 count at enrollment (cells/μL), median (IQR) | 274 (113–420) |

| HIV RNA level at enrollment (log10 copies/mL), median (IQR) | 4.7 (3.8–5.3) |

| History of AIDS-defining illness, n (%) | 828 (21.8) |

| Route of HIV transmission, n (%) | |

| Male-to-male sexual contact | 3122 (82.3) |

| Heterosexual contact | 439 (11.6) |

| Contaminated blood products | 69 (1.8) |

| Injection drug use | 5 (0.1) |

| Other/Unknown | 158 (4.2) |

| Length of follow-up (years), median (IQR) | 10.1 (4.1–15.5) |

| Malignancy | Number of Cases |

|---|---|

| AIDS-defining malignancies | 127 |

| AIDS-defining lymphoma | 65 |

| Kaposi's sarcoma | 62 |

| Non -AIDS-defining malignancies | 161 |

| Stomach | 25 |

| Lung | 21 |

| Prostate | 17 |

| Oral cavity/pharynx | 16 |

| Anal cancer | 12 |

| Liver | 12 |

| Colon | 9 |

| Non-AIDS-defining lymphoma | 8 |

| Hematologic malignancy | 6 |

| Bladder | 5 |

| Skin | 5 |

| Larynx | 4 |

| Rectum | 4 |

| Kidney/urinary tract (excluding bladder) | 4 |

| Esophagus | 4 |

| Gallbladder/bile duct | 2 |

| Pancreas | 2 |

| Brain/central nervous system | 1 |

| Other | 4 |

| CD4+ count (cells/μL) | |||

| Malignancy type | <200 | 200-499 | ≥500 |

| All malignancies | |||

| Crude incidence rate (per 100,000 PY) | 4794.1 | 572.9 | 269 |

| SIR (95% CI) | 8.04 (6.78-9.47) | 1.15 (0.94-1.39) | 0.68 (0.46-0.96) |

| AIDS-defining malignancies | |||

| Crude incidence rate (per 100,000 PY) | 3285.4 | 104.7 | 34.7 |

| SIR (95% CI) | 183.33 (148.84-223.42) | 6.61 (3.98-10.32) | 2.54 (0.69-6.49) |

| Non-AIDS-defining malignancies | |||

| Crude incidence rate (per 100,000 PY) | 1508.6 | 468.3 | 234.3 |

| SIR (95% CI) | 2.61 (1.90-3.49) | 0.97 (0.78-1.20) | 0.61 (0.40-0.89) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).