Submitted:

16 December 2025

Posted:

17 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

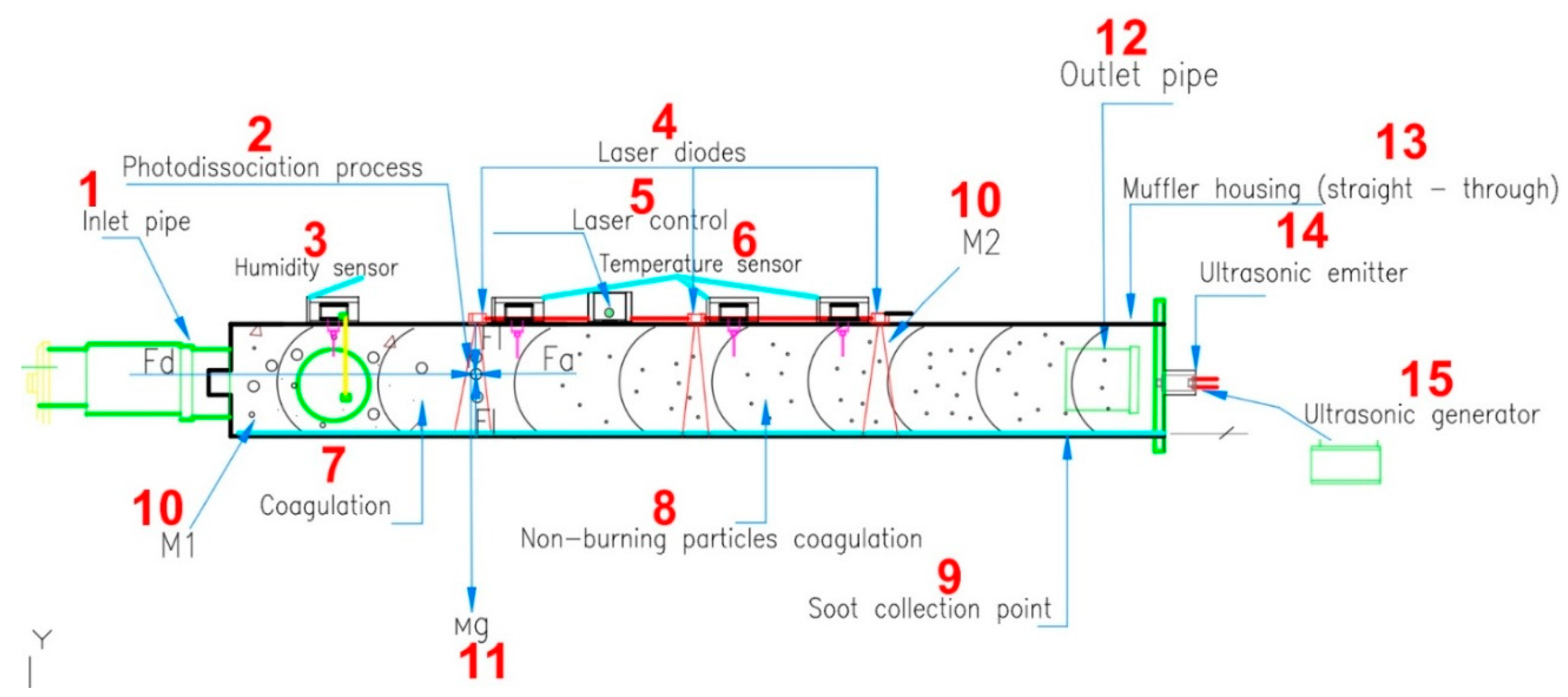

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

3. Results and Discussion

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CH | hydrocarbons (reported as CH4 equivalent) |

| CO | carbon monoxide |

| CO2 | carbon dioxide |

| O2 | oxygen |

| IR | infrared |

| ANOVA | analysis of variance |

| EGR | exhaust gas recirculation |

| NTP | non-thermal plasma |

| UHC | unburned hydrocarbons |

| PM | particulate matter |

References

- Sarsembekov, B. K.; Kadyrov, A. S.; Kunayev, V. A.; Issabayev, M. S.; Kukesheva, A. B. Experimental Comparison of Methods for Cleaning Car Exhaust Gas by Exposure Using Ultrasound and Laser Radiation. Mater. Mech. Eng. Technol. 2024, 3, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, B.; Rajendran, V.; Palanichamy, P. Science and Technology of Ultrasonics; Alpha Science International, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Özyalcin, C.; Sterlepper, S.; Roiser, S.; Eichlseder, H.; Pischinger, S. Exhaust gas aftertreatment to minimize NOX emissions from hydrogen-fueled internal combustion engines. Appl. Energy 2024, т. 353, PA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoa, N. X.; Lim, O. A Review of the External and Internal Residual Exhaust Gas in the Internal Combustion Engine. Energies 2022, т. 15(3), 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsueh, M.-H. An Analysis of Exhaust Emission of the Internal Combustion Engine Treated by the Non-Thermal Plasma. Molecules 2020, т. 25(24), 6041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C. Review of Combustion Performance Improvement and Nitrogen-Containing Pollutant Control in the Pure Hydrogen Internal Combustion Engine. Int. J. Automot. Manuf. Mater. 2022, т. 1. 1, c. 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, D. N. Gas separation using ultrasound and light absorption. WO2010039503A1. 8 April 2010. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/WO2010039503A1/en.

- Fujii T. и 藤井敏昭, «窒素酸化物を含有するガス混合物中の窒素酸化物の分解方法», JPS63267423A, 4 Nov. 1988 y. 2025 y. [Online]. Дocтyпнo нa: https://patents.google.com/patent/JPS63267423A/en?oq=Patent+JPS63267423A.

- Japanese Journal of Applied Physics. 2025. Available online: https://www.mindat.org/reference.php?id=14997346.

- Kadyrov; Sarsembekov, B.; Ganyukov, A.; Suyunbaev, S.; Sinelnikov, K. Ultrasonic Unit for Reducing the Toxicity of Diesel Vehicle Exhaust Gases. Commun. - Sci. Lett. Univ. Zilina 2022, т. 24(3), B189–B198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamim, T. Effect of engine exhaust gas modulation on the cold start emissions. Int. J. Automot. Technol. 2011, т. 12(4), 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadyrov, S.; Sarsembekov, B. K.; Ganyukov, A. A.; Zhunusbekova, Z. Z.; Alikarimov, K. N. Experimental Research of the Coagulation Process of Exhaust Gases under the Influence of Ultrasound. Commun. - Sci. Lett. Univ. Zilina 2021, т. 23(4), B288–B298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmonds, P. D.; Sancier, K. M. Evidence for free radical production by ultrasonic cavitation in biological media. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 1983, т. 9. 6, 635–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, I.-S.; Xi, J.; Hu, H.-Y. Photolysis and photooxidation of typical gaseous VOCs by UV Irradiation: Removal performance and mechanisms. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2018, т. 12. 3, c. 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khmelev, V. N.; Shalunov, A. V.; Golykh, R. N. Increasing the Efficiency of Coagulation of Submicron Particles under Ultrasonic Action. Theor. Found. Chem. Eng. 2020, т. 54. 4, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, J.; Cen, K. Frequency comparative study of coal-fired fly ash acoustic agglomeration. J. Environ. Sci. China 2011, т. 23(11), 1845–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazyan, W. I.; Ahmadi, A.; Ahmed, H.; Hoorfar, M. Increasing efficiency of natural gas cyclones through addition of tangential chambers. J. Aerosol Sci. 2017, т. 110, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego-Juarez, J. A.; Graff, K. F. Power Ultrasonics: Applications of High-Intensity Ultrasound; Elsevier, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Japanese Journal of Applied Physics. 2025. Available online: https://www.mindat.org/reference.php?id=14997346.

- L. Bergmann, Der Ultraschall und seine Anwendung in Wissenschaft und Technik. S. Hirzel, 1954.

- Oliveira, R. A. F.; Guerra, V. G.; Lopes, G. C. Improvement of collection efficiency in a cyclone separator using water nozzles: A numerical study. Chem. Eng. Process. - Process Intensif. 2019, т. 145, c. 107667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khmelev, V. N.; Shalunov, A. V.; Golykh, R. N. Increasing the Efficiency of Coagulation of Submicron Particles under Ultrasonic Action. Theor. Found. Chem. Eng. 2020, т. 54(4), 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riera-Franco De Sarabia, E.; Gallego-Juárez, J. A. Ultrasonic agglomeration of micron aerosols under standing wave conditions. J. Sound Vib. 1986, т. 110(3), 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rückerl, R. Ultrafine particles and platelet activation in patients with coronary heart disease--results from a prospective panel study. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2007, т. 4, c. 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rückerl, R.; Schneider, A.; Breitner, S.; Cyrys, J.; Peters, A. Health effects of particulate air pollution: A review of epidemiological evidence. Inhal. Toxicol. 2011, т. 23(10), 555–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seya, K.; Nakane, T.; Otsuro, T. Agglomeration of Aerosols by Ultrasonically Produced Water Mist. 1975 Ultrasonics Symposium, september. 1975; pp. 583–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surmen, A.; Avci, A.; Karamangil, M. I. Prediction of the maximum-efficiency cyclone length for a cyclone with a tangential entry. Powder Technol. 2011, т. 207(1–3), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Lipkens, B.; Cameron, T. M. The effects of orthokinetic collision, acoustic wake, and gravity on acoustic agglomeration of polydisperse aerosols. J. Aerosol Sci. 2006, т. 37(4), 540–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Zhou, J.; Cen, K. Numerical simulation of acoustic wake effect in acoustic agglomeration under Oseen flow condition. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2012, т. 57(19), 2404–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tитoв, C. C. Optical methods and algorithms for determination of fine aerosol parameters»; 2014; pp. 261–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.; Li, S.; Jin, H.; Hu, S.; Wang, F.; Zhou, F. Analysis of the performance of a novel dust collector combining cyclone separator and cartridge filter. Powder Technol. 2018, т. 339, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Ji, Z.; Wu, X. Investigation on the Separation Performance of a Multicyclone Separator for Natural Gas Purification. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2014, т. 14(3), 1055–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surmen, A.; Avci, A.; Karamangil, M. I. Prediction of the maximum-efficiency cyclone length for a cyclone with a tangential entry. Powder Technol. 2011, т. 207(1–3), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riera-Franco de Sarabia, E.; Elvira-Segura, L.; González-Gómez, I.; Rodríguez-Maroto, J. J.; Muñoz-Bueno, R.; Dorronsoro-Areal, J. L. Investigation of the influence of humidity on the ultrasonic agglomeration of submicron particles in diesel exhausts. Ultrasonics 2003, т. 41(4), 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallego-juarez, J.; Riera, E. Acoustic preconditioning of coal combustion fumes for enhancement of electrostatic precipitator performance: I. The acoustic preconditioning system. Coal Sci. Technol. 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

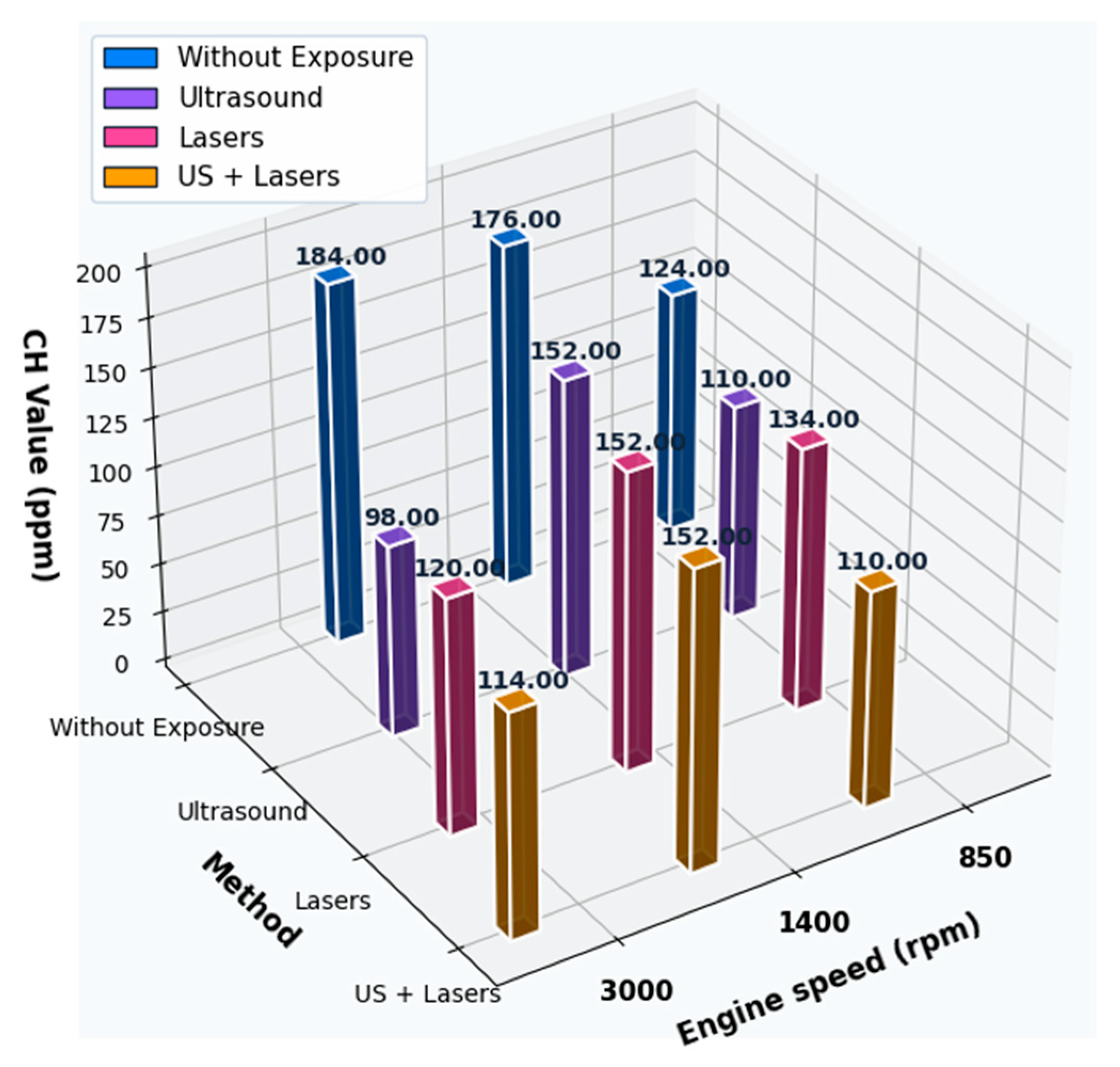

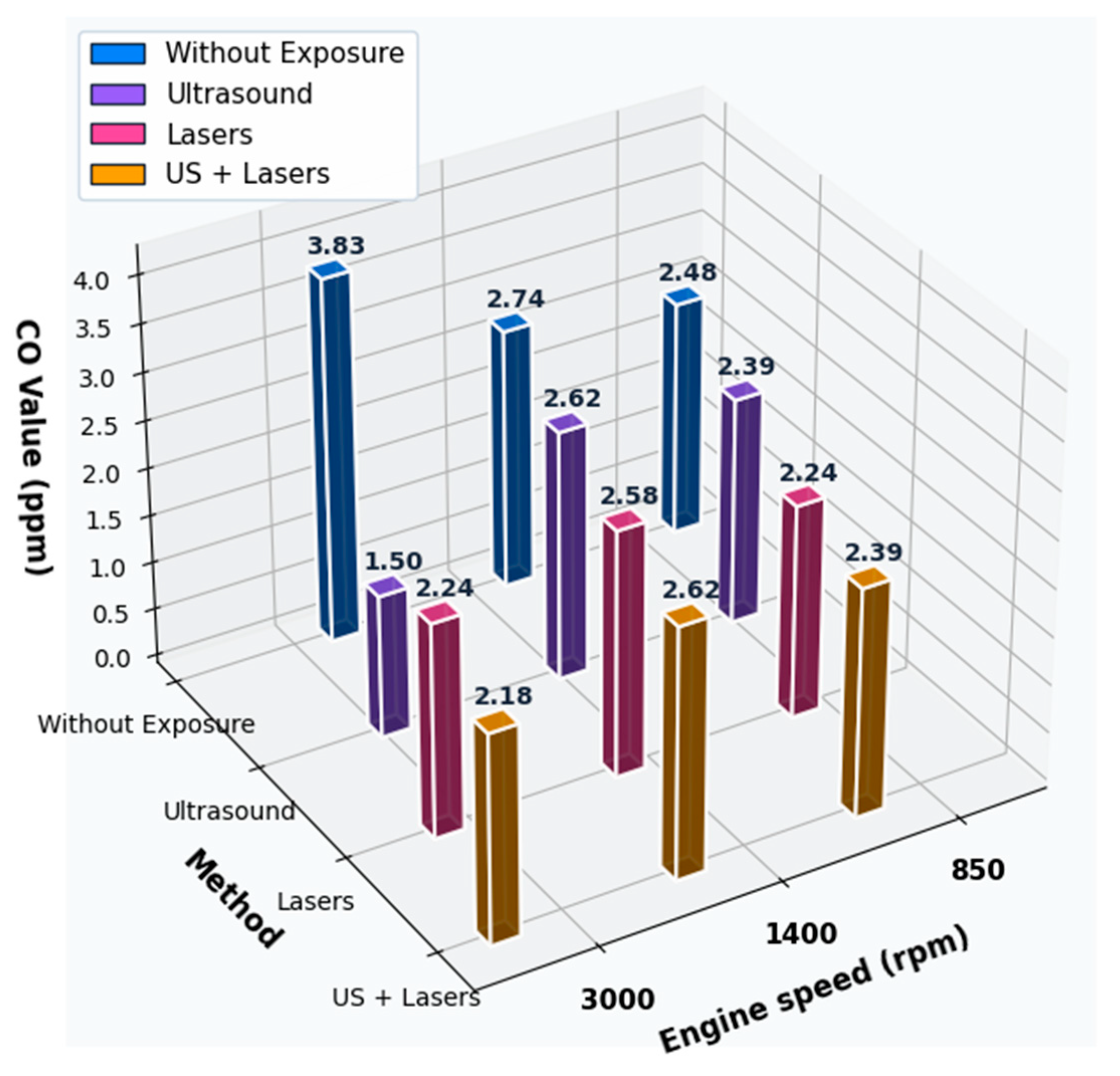

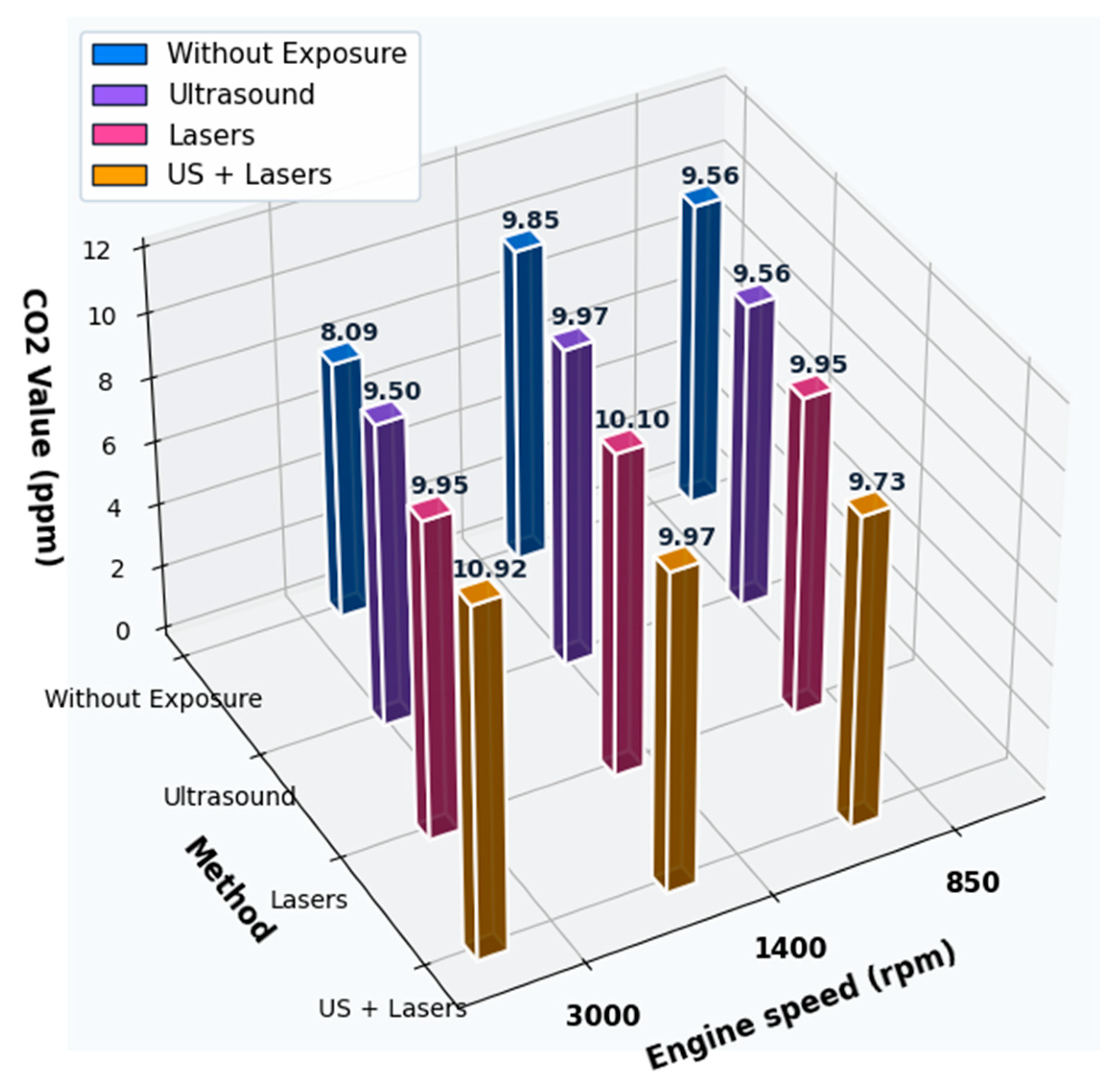

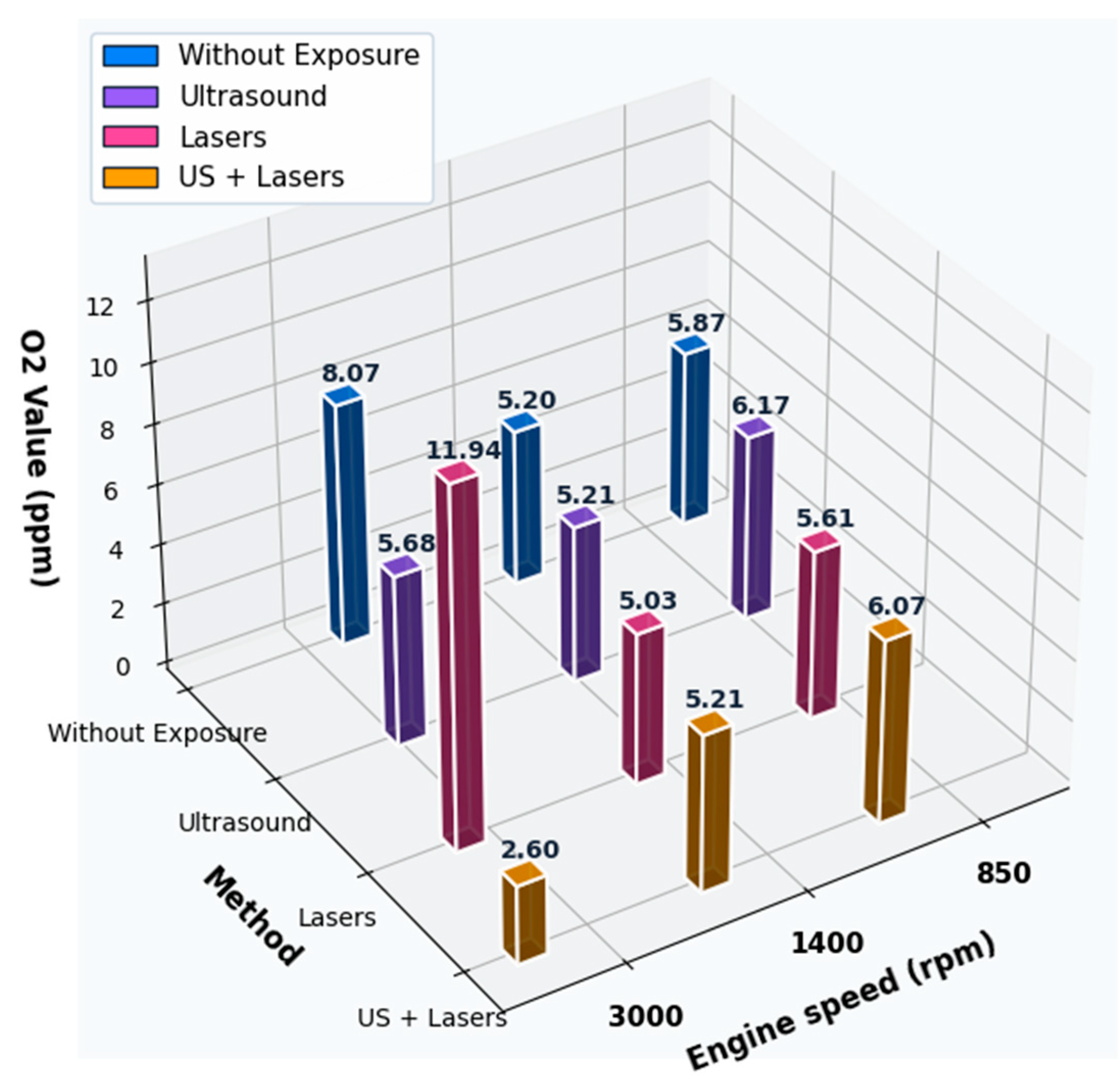

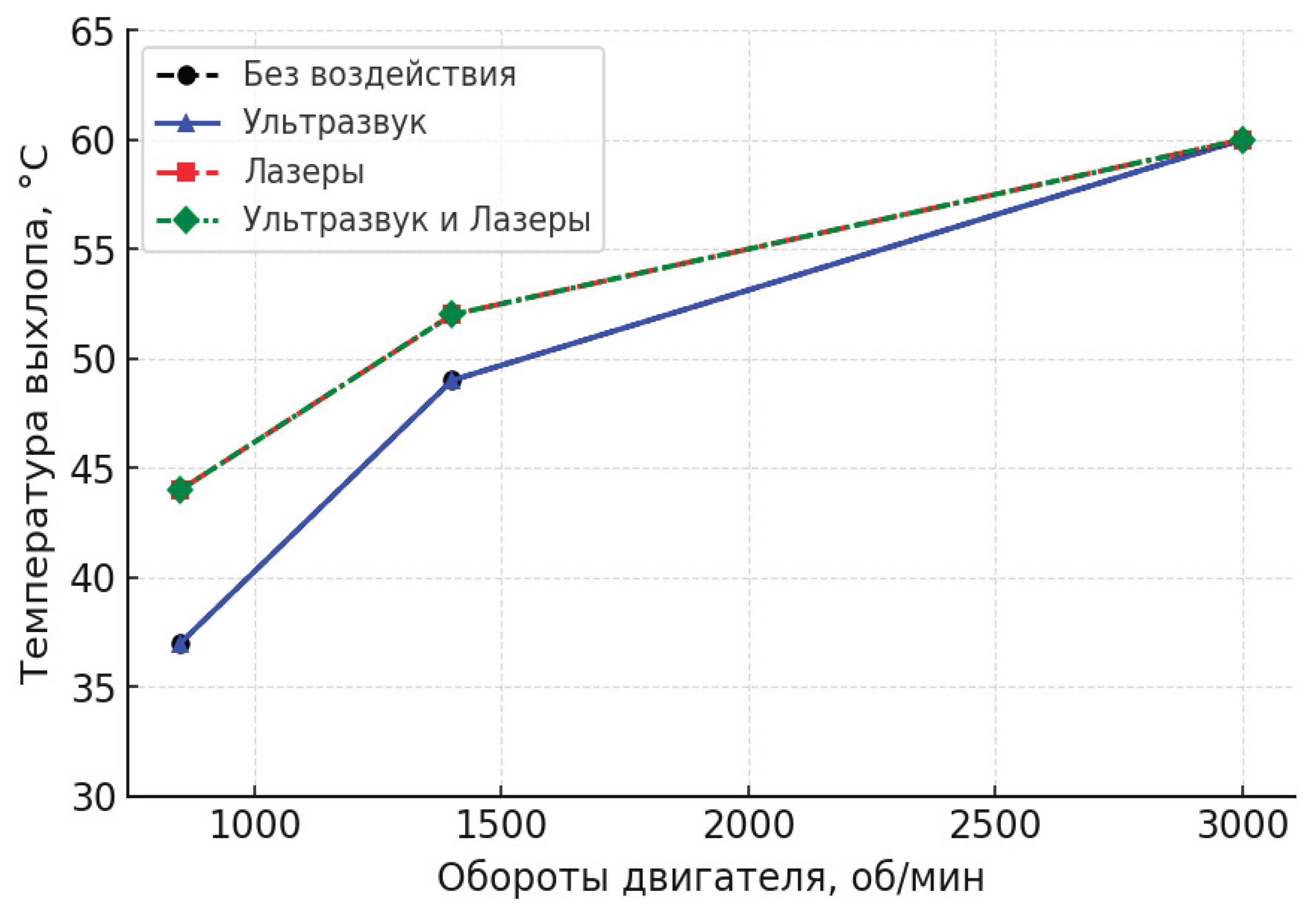

| Stage | Engine speed (rpm) | CH (ppm) |

CO (%) |

CO2 (%) |

O2(%) | Gas temperature(°C) | Humidity(%) |

| No treatment | 850 | 124 | 2.48 | 9.56 | 5.87 | 37 | 39 |

| Ultrasound | 850 | 110 | 2.39 | 9.56 | 6.17 | 37 | 39 |

| Lasers | 850 | 134 | 2.24 | 9.95 | 5.61 | 44 | 39 |

| Ultrasound + Lasers | 850 | 110 | 2.39 | 9.73 | 6.07 | 44 | 39 |

| No treatment | 1400 | 176 | 2.74 | 9.85 | 5.2 | 49 | 39 |

| Ultrasound | 1400 | 152 | 2.62 | 9.97 | 5.21 | 49 | 39 |

| Lasers | 1400 | 152 | 2.58 | 10.1 | 5.03 | 52 | 39 |

| Ultrasound + Lasers | 1400 | 152 | 2.62 | 9.97 | 5.21 | 52 | 39 |

| No treatment | 3000 | 184 | 3.83 | 8.09 | 8.07 | 60 | 39 |

| Ultrasound | 3000 | 98 | 1.5 | 9.5 | 5.68 | 60 | 39 |

| Lasers | 3000 | 120 | 2.24 | 9.95 | 11.94 | 60 | 39 |

| Ultrasound + Lasers | 3000 | 114 | 2.18 | 10.92 | 2.6 | 60 | 39 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).