1. Introduction

Low back pain (LBP) represents a leading cause of disability worldwide and affects individuals across all age groups and socio-economic strata. Epidemiological data indicate that up to 84% of the population will experience LBP at some point in their lifetime, with approximately 20% progressing to a chronic condition [

1]. Because LBP predominantly affects the working-age population, it constitutes a substantial public health concern with far-reaching economic and societal consequences, including productivity loss, increased healthcare utilization, and reduced quality of life [

2]. Analyses from the Global Burden of Disease study further highlight the contribution of modifiable lifestyle-related risk factors—particularly occupational ergonomic exposures, smoking, and obesity—to the overall burden of LBP [

3].

In the majority of cases, LBP cannot be attributed to a clearly identifiable structural or pathological cause. Approximately 90% of patients are therefore classified as having non-specific low back pain [

4]. When symptoms persist beyond 12 weeks, the condition is defined as chronic non-specific low back pain (CNSLBP) [

5]. Beyond traditional nociceptive and neuropathic mechanisms, increasing attention has been directed toward nociplastic pain, which is characterized by altered nociceptive processing in the absence of clear tissue damage or neural injury [

6,

7]. This mechanism provides a plausible explanation for the persistence of pain after tissue healing, the occurrence of pain without detectable pathology, and pain severity that is disproportionate to observable structural findings [

8,

9,

10,

11].

The multifactorial nature of CNSLBP challenges the adequacy of a purely biomedical perspective, which conceptualizes pain primarily as a direct consequence of tissue injury or structural impairment. As a result, the biopsychosocial model (BPSM) has emerged as the dominant framework for understanding and managing CNSLBP, emphasizing the dynamic interaction between biological, psychological, and social factors in shaping the pain experience [

12]. This approach conceptualizes pain as a subjective phenomenon encompassing sensory, emotional, cognitive, and contextual dimensions [

13] and is strongly supported by empirical evidence and international clinical guidelines, including those issued by the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) [

14].

Physiotherapists play a central role in the conservative management of CNSLBP; however, the translation of biopsychosocial principles into everyday clinical practice remains challenging. Therapists’ beliefs, attitudes, and understanding of pain mechanisms can significantly influence clinical decision-making and adherence to evidence-based guidelines [

15]. To date, no studies in Slovenia have systematically explored physiotherapists’ beliefs, attitudes, or familiarity with clinical guidelines in the management of CNSLBP. Gaining insight into these factors is essential for enhancing clinical practice, strengthening professional competence, and promoting consistent implementation of evidence-based care.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

Physiotherapists employed in primary healthcare in Slovenia, both in the public and private sectors, were included in the study. They were invited to complete an online questionnaire via official email addresses, personal contacts, and a post in the Facebook group "Fizioterapija". Data collection was conducted between June 6 and July 22, 2024. Participation was voluntary, and respondents' complete anonymity was ensured. The study was carried out in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. As the data collection did not involve any intervention and was completely anonymous, ethical approval was not required. Participation in the survey was voluntary, and participants could stop completing the questionnaire at any time.

2.2. Study Instruments and Protocols

A structured questionnaire was used in the study, developed based on a literature review. The questionnaire was divided into three thematic sections.

2.2.1. Sociodemographic Questionnaire

The first section included sociodemographic questions covering gender, level of education, additional specialised knowledge, employment sector, years of professional experience, monthly number of patients with CNSLBP, familiarity with clinical guidelines for the management of CNSLBP, adherence to these guidelines in practice (and reasons for non-adherence, where applicable), and the selection of the three most frequently used physiotherapy interventions in the management of patients with CNSLBP.

2.2.2. Questionnaire Health Care Providers’ Pain and Impairment Relationship Scale(HC-PAIRS)

The HC-PAIRS [

16] assesses healthcare professionals’ attitudes and beliefs regarding the relationship between chronic non-specific low back pain (CNSLBP) and functional impairment. The questionnaire comprises 15 items, organized into four dimensions: functional expectations, social expectations, need for cure, and projected cognitions [

17]. Each item is rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree, 7=strongly agree), with items 1, 6, and 12 reverse scored. The total score ranges from 15 to 105, with higher scores reflecting the belief that pain substantially limits everyday functioning—a perspective inconsistent with current clinical guidelines and contemporary scientific evidence. The internal consistency of the questionnaire is moderate, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.668 (α=0.668).

2.2.3. Questionnaire Back Pain Attitudes Questionnaire (Back-PAQ)

The Back-PAQ [

18], a 10-item version, measures attitudes towards back pain using a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from -2=entirely true to 2=completely false). Items 6, 7, and 8 are reverse-scored. The total score ranges from –20 to 20, with negative values indicating beliefs that are inconsistent with guidelines and unhelpful in managing back pain. For interpretation, five thematic domains are associated with specific items: “vulnerability of the back” (items 1 and 2), “relationship between back pain and injury” (items 3 and 4), “activity participation during back pain” (items 5 and 6), “psychological influences on recovery” (items 7 and 8), and “prognosis of back pain” (items 9 and 10). All items were phrased in the second person, allowing for a personalized questionnaire. This personalization aimed to encourage respondents to express their own beliefs rather than projecting them onto people with LBP or reporting beliefs about others. Cronbach’s alpha for internal consistency indicated very good reliability (α=0.818).

2.2.4. Clinical Vignette

Based on a clinical vignette developed by Rainville and colleagues [

19], respondents answered three questions regarding recommendations for physical activity, work, and bed rest. Responses were provided on a 5-point ordinal scale, where lower scores (1–3) indicated recommendations inconsistent with clinical guidelines, and higher scores (4–5) indicated recommendations consistent with the guidelines. Finally, respondents rated their level of confidence in the appropriateness of the recommendations provided.

2.3. Translation Process

The HC-PAIRS and Back-PAQ questionnaires, as well as the clinical vignette, had not previously been translated into Slovenian. Therefore, a translation was carried out for this study. The translation involved two individuals, one fluent in English and a native Slovenian speaker with a medical background, and the other with a linguistic background. A professor of the Slovenian language subsequently reviewed the Slovenian versions. Two English professors carried out a back-translation into English to ensure translation accuracy. The back-translations, along with the original questionnaires and clinical cases, were compared to confirm both linguistic and content validity. Although standard forward–backward translation procedures were applied, the HC-PAIRS and Back-PAQ questionnaires, as well as the clinical case vignette, have not yet undergone formal cultural adaptation and psychometric validation for the Slovenian context. Therefore, it is possible that the translated items are not fully conceptually, semantically, or psychometrically equivalent to the original versions, which may have affected the accuracy of measurement of certain constructs.

2.4. Methods of Analysis

This study employed a descriptive and quantitative research methodology. Data were analyzed utilizing the 1KA web platform, IBM SPSS Statistics 25.0, and Microsoft Excel. The analytical procedures included frequency counts, descriptive statistics, t-tests,

Spearman’s rank correlation, and Pearson’s correlation coefficient

3. Results

3.1. Study Group Description

The study included 104 physiotherapists. Data from the Slovenian Health Insurance Institute (ZZZS) indicate that, as of June 2024, 726 physiotherapists were working in primary care; the sample of 104 participants represents approximately 14% of the total physiotherapist population. The demographic and professional details of the respondents are shown in

Table 1.

Among the surveyed physiotherapists, 88% were women and 12% were men, reflecting the general gender distribution within the profession. Most physiotherapists (75%) obtained their education within higher professional study programmes, under either the pre-Bologna or the Bologna system. A total of 58% of respondents reported no additional specialised training, while 30% indicated having undertaken further education in manual or musculoskeletal therapy. In terms of employment setting, most physiotherapists were employed in the public healthcare sector (78%). The most proportion of respondents (38%) had less than five years of professional experience. More than half of the physiotherapists (52%) reported monthly treating ten or more patients with CNSLBP. Knowledge of clinical guidelines for managing patients with CNSLBP was reported by 81% of physiotherapists, of whom 69% stated that they also apply these guidelines in their daily clinical practice.

3.2. Physiotherapists’ Attitudes and Beliefs

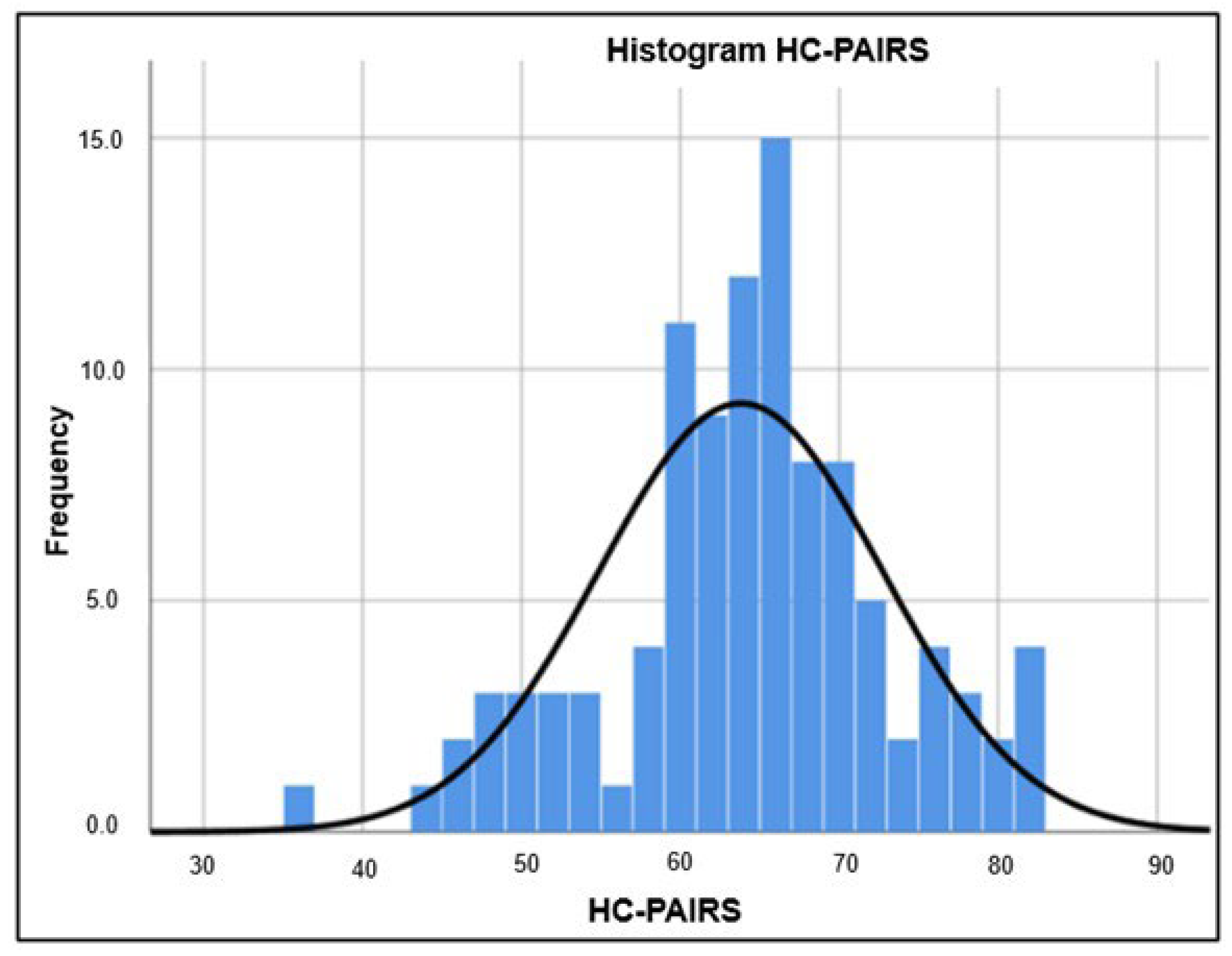

The calculated mean score (M) for the HC-PAIRS questionnaire was M=63.80, indicating a predominantly biomedical orientation among the surveyed physiotherapists. The majority of participants (81%) either partially or strongly disagreed with the statement that patients with CLBP should accept the fact that they are disabled because of their condition. Furthermore, 71% disagreed that these patients should receive the same benefits as people with disabilities due to their chronic pain. Respondents also partially or strongly disagreed with the idea that chronic CLBP limits functional performance, as 77% believed that such patients can still fulfill work and family obligations. At the same time, 78% of respondents either partly or strongly agreed, or remained neutral, regarding the statement that patients should stop what they are doing when their pain increases until it subsides. Conversely, 74% disagreed or remained neutral on the statement that patients should continue their usual activities despite increased pain. A large majority of respondents (92%) partly or strongly agreed that patients with chronic CLBP frequently think about their pain and its impact on their lives. In comparison, 86% believed that these patients have trouble maintaining focus on other activities when pain increases. The HC-PAIRS results are shown in a histogram (

Figure 1).

The range of HC-PAIRS scores, spanning from 40 to 80 points, indicates varying levels of agreement among respondents. Most scores were concentrated between 60 and 70 points, with the highest number of respondents achieving a score just below 70. The standard distribution curve indicates that the results are approximately symmetrically distributed around the mean, suggesting that responses were relatively balanced, with minimal deviations in either direction. This shows that the majority of physiotherapists believe that chronic low back pain substantially limits patients’ functional abilities and affects their daily activities.

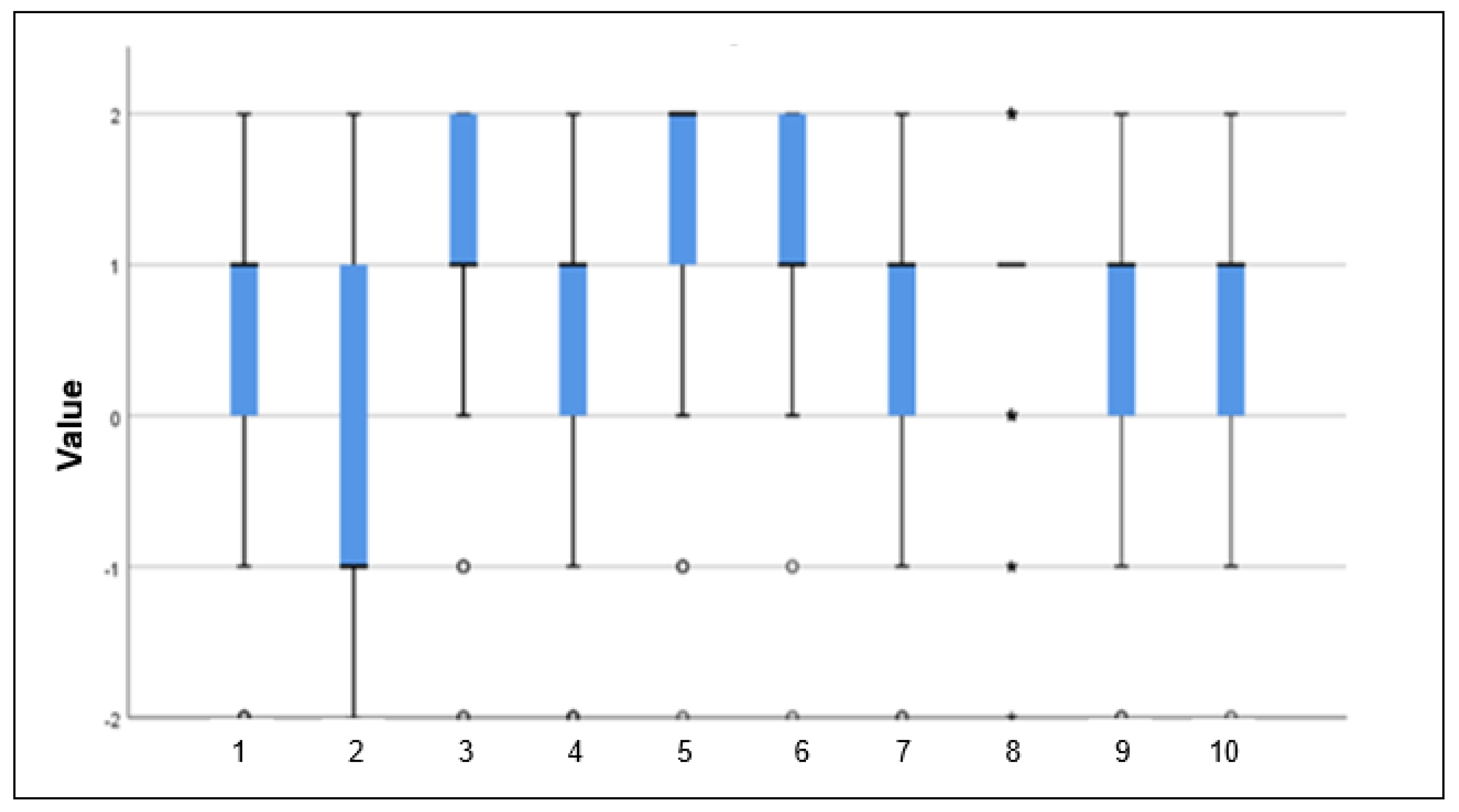

For the Back-PAQ, the mean score was M=7.60. Ninety-five percent of respondents disagreed with the statement that physical activity should be avoided during back pain (statement 5), and 92% believed that remaining active is important (statement 6). For the “back vulnerability” domain, greater deviations from guideline recommendations were observed: 68% of respondents agreed or were uncertain about the statement that the back can be easily injured due to carelessness (statement B). In comparison, 31% believed that the back is easily susceptible to injury (statement A). The boxplot illustrates the considerable spread of responses across individual items, as all possible responses were represented for each statement (

Figure 2). This suggests that physiotherapists demonstrate adherence to contemporary guidelines regarding physical activity. However, some beliefs related to back vulnerability and the influence of psychological factors were still present, which do not fully align with guideline recommendations.

Mean scores (M) and standard deviations (SD) for both questionnaires are shown in

Table 2.

The results of the HC-PAIRS questionnaire and most items of the Back-PAQ, together with the considerable dispersion of responses in the latter, indicate that the surveyed physiotherapists predominantly hold attitudes and beliefs that are not consistent with clinical guidelines.

Furthermore, a statistically significant negative correlation was observed between the HC-PAIRS and Back-PAQ questionnaires (Pearson r=–0.329, Spearman r=–0.437). This suggests that physiotherapists who express a stronger biomedical view of chronic pain tend to show lower adherence to contemporary recommendations regarding movement and psychosocial factors in patient management.

3.3. Physiotherapists’ Recommendations Regarding Work, Rest, and Activity

Fifty-four per cent of physiotherapists provided recommendations regarding physical activity that were consistent with guidelines. Only 11% provided work-related advice in accordance with guidelines, whereas 89% offered inconsistent recommendations, advising either a complete absence from work (21%) or lighter duties with reduced working hours (68%). These findings suggest that the majority of physiotherapists continue to recommend restrictions that do not in alignment with current guidelines, reflecting a biomedical orientation.

Regarding rest, 36% of physiotherapists provided guideline-consistent recommendations. The remaining 64% advised bed rest, either during episodes of severe pain (56%) or for prolonged periods (8%). These results demonstrate that most physiotherapists still recommend some degree of rest, which is not in line with current guidelines (

Table 3).

Most respondents (54%) felt confident about their recommendations, with 13% saying they were totally confident in their advice. On the other hand, 28% were unsure about their recommendations, and 5% had doubts. No respondents indicated they lacked confidence in their recommendations at all.

A comparison of results showed a statistically significant difference in the Back-PAQ based on years of professional experience (p=0.028), with more experienced physiotherapists scoring higher (M=8.13) than those with less experience (M=6.83). In contrast, no significant differences were observed in the HC-PAIRS (p=0.378) or the clinical vignette (p=0.479). These findings suggest that professional experience may influence certain beliefs but does not consistently affect overall knowledge of guidelines or the ability to provide recommendations. Additionally, there were no statistically significant differences between physiotherapists treating fewer than five patients with chronic non-specific low back pain per month and those treating ten or more patients across all measures: HC-PAIRS (p=0.840), Back-PAQ (p=0.830), and the clinical vignette (p=0.950).

4. Discussion

Recommendations provided by healthcare professionals, including physiotherapists, play an important role in shaping patients’ attitudes towards pain and influencing clinical outcomes. Clinical guidelines for the management of low back pain (LBP) in the absence of specific pathology consistently emphasise the need for an active approach. The guidelines recommend that, despite experiencing pain, patients should remain active, continue with their usual daily activities, and return to work as soon as possible. They stress that physical activity does not exacerbate chronic LBP and discourage rest and passive approaches, instead promoting the maintenance of high levels of activity and continued work, even when pain persists [

20].

Unhelpful beliefs about LBP, such as the belief that the back is a fragile structure that requires protection, are associated with greater fear of pain, movement avoidance, catastrophising, and depression [

21]. A systematic review of qualitative and quantitative studies showed that physiotherapists’ beliefs regarding fear-avoidance behaviours significantly influence their clinical practice and the advice provided to patients [

22]. Physiotherapists with a predominantly biomedical orientation are more likely to recommend activity limitation, emphasise risks associated with work or movement, and suggest sick leave. Such cautious and passive approaches may lead to reduced patient activity, reinforcement of maladaptive beliefs, and poorer understanding of self-management in pain control.

The average HC-PAIRS score among the surveyed physiotherapists in Slovenia was 63.80, indicating a strong belief that CNSLBP substantially limits daily functioning. This reflects a predominantly biomedical orientation, in which pain is closely associated with movement and activity, leading to the perception that physical activity should be avoided. This value is notably higher than those reported in previous studies. A review of HC-PAIRS use across 51 studies reported a mean score of 52.64 among healthcare professionals routinely treating patients with LBP, with physiotherapists showing a slightly higher mean score of 53.42 [

23]. A meta-analysis of twelve studies reported mean HC-PAIRS scores for physiotherapists ranging from 42.92 to 61.60, while physicians demonstrated lower scores (31.92–54.40) [

24]. In the original development of the HC-PAIRS questionnaire, a mean score of 38 was reported [

23].

Analysis of the Back-PAQ questionnaire indicated that most physiotherapists endorsed the importance of maintaining physical activity and persisting with movement during recovery. However, more than half expressed negative or neutral attitudes toward statements related to back vulnerability, with approximately one-third believing that the back can be easily injured. The proportion of such beliefs was higher than that reported in previous studies, where negative beliefs about back vulnerability were observed in 43–50% of physiotherapists [

25,

26].

Comparison of subgroup results revealed a statistically significant difference in Back-PAQ scores based on years of professional experience, with more experienced physiotherapists achieving higher mean scores, suggesting more positive beliefs regarding movement and activity (p = 0.028). No significant differences were found for HC-PAIRS scores (p = 0.378) or responses to the clinical case (p = 0.479). No statistically significant differences were found between physiotherapists who treat fewer than five patients with CNSLBP per month and those who treat ten or more (HC-PAIRS p = 0.840; Back-PAQ p = 0.830; clinical case p = 0.950).

The majority of physiotherapists reported using treatment approaches that are not fully aligned with contemporary clinical guidelines, including electrotherapy, manipulative techniques, and a strong emphasis on core stabilisation and ergonomic advice. Electrotherapy was among the three most frequently used interventions for 64% of respondents, and traction—an intervention not recommended in guidelines—was reported by several participants. In contrast, graded exercise, a central component of guideline-recommended care, was rarely identified as a primary treatment strategy. These findings differ from reports in other settings, where physiotherapists more commonly implement progressive exercise programmes and active treatment approaches [

26,

27].

Analysis of responses to the clinical case demonstrated the highest level of guideline adherence in recommendations related to physical activity, consistent with the Back-PAQ findings. However, advice regarding work participation and rest frequently deviated from guideline recommendations, with non-concordant work-related advice exceeding levels reported in other studies [

25]. This suggests that, while awareness of the importance of activity may be improving, misconceptions related to work and rest persist.

Overall, the findings indicate that beliefs linking CNSLBP to functional impairment exert a stronger influence on guideline-inconsistent recommendations than beliefs about movement itself. Although physiotherapists largely support activity despite pain, persistent beliefs about spinal fragility and the need for protection reflect a predominantly biomedical orientation that is inconsistent with contemporary guidelines. Evidence suggests that clinical practice is influenced more by clinicians’ beliefs and attitudes than by guideline knowledge alone, with patient expectations further reinforcing non-guideline-compliant behaviours [

22].

Early identification of unhelpful beliefs using standardised instruments such as HC-PAIRS and Back-PAQ is recommended. Targeted education of physiotherapists and other healthcare professionals, focusing on the biopsychosocial model and effective patient communication, may improve guideline adherence and clinical outcomes. In addition, clinical guidelines should more clearly specify the type, intensity, and frequency of physical activity, while remaining adaptable to different healthcare systems and local contexts. Sustainable implementation of evidence-based approaches will likely require systemic changes, including multidisciplinary collaboration, payment model adjustments, and the integration of digital health and telemedicine solutions.

The main limitation of this study is the relatively small sample size. Based on national workforce data, a larger sample would have been required to ensure adequate statistical power, and the results should therefore be interpreted with caution. An additional limitation is the lack of formal cultural adaptation and psychometric validation of the translated questionnaires, which may affect the reliability and generalisability of the findings. Future research should address these methodological issues to strengthen the evidence base.

5. Conclusions

The results of this study indicate that Slovenian physiotherapists in primary healthcare often maintain attitudes and clinical decisions that deviate from evidence-based clinical guidelines, despite their availability. The highest adherence to contemporary recommendations was observed in promoting physical activity (54%), whereas beliefs and recommendations regarding return to work (89% non-adherent) and bed rest (64% non-adherent) were markedly inconsistent with guidelines. Responses to the HC-PAIRS and Back-PAQ questionnaires further confirm that physiotherapists predominantly retain a biomedical understanding of pain, rather than the biopsychosocial approach endorsed by current guidelines.

These patterns highlight significant gaps in knowledge and beliefs that influence clinical practice. The use of standardized tools (HC-PAIRS, Back-PAQ), structured educational programs, and interactive workshops with clinical cases could improve understanding of the biopsychosocial factors of pain. Telerehabilitation presents an additional opportunity for more consistent long-term patient monitoring and reinforcement of adherence to recommendations.

Future research should examine the impact of updated educational interventions and systemic changes on clinical decision-making and long-term treatment outcomes. Effective, evidence-based management of chronic nonspecific low back pain will also require interprofessional collaboration, improved organizational structures, and an active role for patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G. and M.F.; methodology, A.G.; formal analysis, A.G.; investigation, A.G.; data curation, A.G.; writing—original draft preparation, A.G.; writing—review and editing, A.G. and M.F.; supervision, M.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, as according to national regulations of the country where the study was conducted, research involving anonymous questionnaire-based surveys without collection of sensitive personal data does not require approval from an ethics committee.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study. Prior to completing the survey, participants were informed about the purpose of the study, the voluntary nature of participation, the anonymity of the data, and their right to withdraw at any time without consequences.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LBP |

low back pain |

| CNSLBP |

chronic non-specific low back pain |

| BPSM |

biopsychosocial model |

| NICE |

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence |

| HC-PAIRS |

Health Care Providers’ Pain and Impairment Relationship Scale |

| Back-PAQ |

Back Pain Attitudes Questionnaire |

| ZZZS |

Slovenian Health Insurance Institute |

References

- Zhou, T.; Salman, D.; McGregor, A.H. Recent clinical practice guidelines for the management of low back pain: a global comparison. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2024, 25, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartvigsen, J.; Hancock, M.J.; Kongsted, A.; Louw, Q.; Ferreira, M.L.; Genevay, S.; Hoy, D.; Karppinen, J.; Pransky, G.; Sieper, J.; et al. What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. Lancet 2018, 391, 2356–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.L.; de Luca, K.; Haile, L.M.; Steinmetz, J.D.; Culbreth, G.T.; Cross, M.; A Kopec, J.; Ferreira, P.H.; Blyth, F.M.; Buchbinder, R.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of low back pain, 1990–2020, its attributable risk factors, and projections to 2050: a systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol. 2023, 5, e316–e329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheeran, L.; Sparkes, V.; Caterson, B.; Busse-Morris, M.; van Deursen, R. Spinal Position Sense and Trunk Muscle Activity During Sitting and Standing in Nonspecific Chronic Low Back Pain. Spine 2012, 37, E486–E495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, A.K.; Balagué, F.; Cardon, G.; Eriksen, H.R.; Henrotin, Y.; Lahad, A.; Leclerc, A.; Müller, G.; van der Beek, A.J. Chapter 2 European guidelines for prevention in low back pain. Eur. Spine J. 2006, 15, s136–s168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzcharles, M.-A.; Cohen, S.P.; Clauw, D.J.; Littlejohn, G.; Usui, C.; Häuser, W. Nociplastic pain: towards an understanding of prevalent pain conditions. Lancet 2021, 397, 2098–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clauw, D.J. From fibrositis to fibromyalgia to nociplastic pain: how rheumatology helped get us here and where do we go from here? Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2024, 83, 1421–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Morlion, B.; Perrot, S.; Dahan, A.; Dickenson, A.; Kress, H.G.; Wells, C.; Bouhassira, D.; Drewes, A.M. Assessment and manifestation of central sensitisation across different chronic pain conditions. Eur. J. Pain 2018, 22, 216–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- As-Sanie, S.; Till, S.R.; Schrepf, A.D.; Griffith, K.C.; Tsodikov, A.; Missmer, S.A.; Clauw, D.J.; Brummett, C.M. Incidence and predictors of persistent pelvic pain following hysterectomy in women with chronic pelvic pain. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 225, 568.e1–568.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brummett, C.M.; Urquhart, A.G.; Hassett, A.L.; Tsodikov, A.; Hallstrom, B.R.; Wood, N.I.; Williams, D.A.; Clauw, D.J. Characteristics of Fibromyalgia Independently Predict Poorer Long-Term Analgesic Outcomes Following Total Knee and Hip Arthroplasty. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015, 67, 1386–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, A.; Wanigasekera, V.; Mezue, M.; Cooper, C.; Javaid, M.K.; Price, A.J.; Tracey, I. Central Sensitization in Knee Osteoarthritis: Relating Presurgical Brainstem Neuroimaging and PainDETECT-Based Patient Stratification to Arthroplasty Outcome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019, 71, 550–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart, K.M. The biopsychosocial model of pain in physiotherapy: past, present and future. Phys. Ther. Rev. 2023, 28, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankin, L. Chronic pain: From the study of student attitudes and preferences to the in vitro investigation of a novel treatment strategy: dissertation. Umeå University: Umeå, 2020. Available online: https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:umu:diva-173854.

- NICE. Low back pain and sciatica in over 16s: Assessment and management (NG59); National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [Internet]: London, 2016 [updated 2020 Dec 11; Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng59/chapter/Recommendations.

- Darlow, B.; Fullen, B.; Dean, S.; Hurley, D.; Baxter, G.; Dowell, A. The association between health care professional attitudes and beliefs and the attitudes and beliefs, clinical management, and outcomes of patients with low back pain: A systematic review. Eur. J. Pain 2012, 16, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houben, R.M.A.; Vlaeyen, J.W.S.; Peters, M.; Ostelo, R.W.J.G.; Wolters, P.M.J.C.; Berg, S.G.M.S.-V.D. Health Care Providers' Attitudes and Beliefs Towards Common Low Back Pain: Factor Structure and Psychometric Properties of the HC-PAIRS. Clin. J. Pain 2004, 20, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, A.; Thomas, E.; Foster, N.E. Health care practitioners’ attitudes and beliefs about low back pain: A systematic search and critical review of available measurement tools. PAIN® 2007, 132, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darlow, B.; Perry, M.; Mathieson, F.; Stanley, J.; Melloh, M.; Marsh, R.; Baxter, G.D.; Dowell, A. The development and exploratory analysis of the Back Pain Attitudes Questionnaire (Back-PAQ). BMJ Open 2014, 4, e005251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.W.; E Foster, N.; Underwood, M.; Vogel, S.; Breen, A.C.; Pincus, T. Testing the effectiveness of an innovative information package on practitioner reported behaviour and beliefs: The UK Chiropractors, Osteopaths and Musculoskeletal Physiotherapists Low back pain ManagemENT (COMPLeMENT) trial [ISRCTN77245761]. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2005, 6, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Carbonell, M.; Sequeira-Daza, D.; Checa, I.; Domenech, J.; Espejo, B.; Castro-Melo, G. Evaluation of the psychometric properties of the health care providers’ pain and impairment relationship scale (HC-PAIRS) in health professionals and university students from Chile and Colombia. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christe, G.; Crombez, G.; Shannon; Opsommer, E.; Jolles, B.M.; Favre, J. Relationship between psychological factors and spinal motor behaviour in low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PAIN® 162, 672–686. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, T.; Refshauge, K.; Smith, L.; McAuley, J.; Hübscher, M.; Goodall, S. Physiotherapists’ beliefs and attitudes influence clinical practice in chronic low back pain: a systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. J. Physiother. 2017, 63, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, R.D.; Schielke, A.; Gliedt, J.A.; Cooper, J.; Martinez, S.; Eklund, A.; Pohlman, K.A. A scoping review to explore the use of the Health Care Providers’ Pain and Impairment Relationship Scale. PM&R 2024, 16, 1250–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, M.; Vaucher, P.; Esteves, J.E. The beliefs and attitudes of UK registered osteopaths towards chronic pain and the management of chronic pain sufferers - A cross-sectional questionnaire based survey. Int. J. Osteopat. Med. 2018, 30, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourré, A.; Vanderstraeten, R.; Ris, L.; Bastiaens, H.; Michielsen, J.; Demoulin, C.; Darlow, B.; Roussel, N. Management of Low Back Pain: Do Physiotherapists Know the Evidence-Based Guidelines? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2023, 20, 5611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christe, G.; Nzamba, J.; Desarzens, L.; Leuba, A.; Darlow, B.; Pichonnaz, C. Physiotherapists’ attitudes and beliefs about low back pain influence their clinical decisions and advice. Musculoskelet. Sci. Pr. 2021, 53, 102382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prado, T.D.; Parsons, J.; Ripat, J. Evidence-Based Practice for Non-Specific Low Back Pain: Canadian Physiotherapists’ Adherence, Beliefs, and Perspectives. Physiother. Can. 2022, 74, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).