1. Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a critical public health issue in Europe, affecting millions of individuals each year. It includes physical, psychological, sexual, and economic abuse, with women being disproportionately affected. IPV is associated with chronic physical conditions, mental health disorders, and increased healthcare utilization. Improved detection within clinical settings is essential to mitigate these consequences.

Nurses are uniquely positioned for early identification due to their continuous proximity to patients in emergency departments, primary care, and inpatient settings. However, several barriers—including insufficient training, lack of protocols, and limited self-confidence—reduce their ability to identify and manage IPV effectively. Current literature indicates a lack of validated nursing-focused tools to assess clinical competencies regarding IPV detection, assessment, documentation, and intervention.

This study addresses this gap by developing and validating the Intimate Partner Violence Nursing Competency Scale (IPVNCS), which is grounded in NANDA diagnoses [

1], NOC outcomes [

2], and NIC 6403 [

3] (“Abuse Protection Support: Partner”) (

Table A1). The objective is to provide a psychometrically robust instrument to evaluate nurses’ perceived competency in managing IPV.

Intimate partner violence in Europe is a serious public health problem affecting millions of people. Despite advances in gender equality and efforts to eradicate the problem, it persists and manifests itself in various forms, ranging from physical to psychological and sexual violence. Women are the primary victims, although men can also suffer from it. The consequences of intimate partner violence are devastating for the physical and mental health of the victims, as well as for their social and economic well-being. It is essential to address this problem from a multidisciplinary perspective by implementing effective public policies and strengthening support systems for victims [

4]. Nurses, because of their direct contact with patients, are therefore key to the early detection of intimate partner violence. However, they face challenges such as a lack of specific training and resources. Therefore, it is essential to have assessment tools that allow them to effectively identify situations of violence, make a nursing diagnosis, and provide comprehensive care to victims. Intimate partner violence (IPV) presents various factors, such as a history of child abuse [

5] or low self-esteem, that increase vulnerability to this issue. Nurses must be aware of the cycle of violence and risk factors in order to provide appropriate and personalized care.

The devastating consequences of intimate partner violence on physical and mental health make an effective response essential. Nurses, being in direct contact with the victims, are key to detecting and attending to this problem. The implementation of specific assessment instruments, the continuous training of active professionals, and university training at the degree level [

6] are essential to improving the response to this public health problem. Therefore, this study aims to develop a scale with high validity and reliability. This scale should provide useful data to accurately understand nurses’ perceptions of intimate partner violence and facilitate the development of strategies to improve their ability to detect, intervene, and support victims of intimate partner violence.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

A cross-sectional psychometric validation study was conducted between 2023 and 2024 in the Community of Madrid. Ethical approval was granted by CEU San Pablo University (843/24/104).

2.2. Participants and Sample

Registered nurses working in clinical settings were recruited through professional organizations, health centers, and social networks.

A total sample of 202 participants was obtained, meeting the recommended 5–10 subjects per item for factor analysis.

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

Active clinical practice, an officially recognized nursing degree in Spain, and professional registration. Exclusion criteria included

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

Retired or inactive nurses, non-accredited degrees, and nursing students.

2.3. Measuring Instrument

A 30-item Likert-type scale (1 = not competent; 5 = highly competent) was created based on:

NANDA: Dysfunctional Family Processes (00063)

NIC 6403: Abuse Protection Support (partner)

NOC 2603: Family Integrity

Clinical guidelines for the detection and management of IPV.

The scale covered detection, assessment, psychosocial support, documentation, and referral.

2.4. Data Collection

The instrument was delivered through Microsoft FormsTM, ensuring anonymity. Data were collected between June and December 2024.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Analyzes were conducted using SPSS 29TM and AMOS 26TM. Reliability: Cronbach’s alpha. Construct validity:

EFA with Promax rotation.

Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s test.

CFA using maximum likelihood estimation.

Fit indices included /df, RMSEA, RMR, NFI, TLI, and CFI.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Data

The profile of the sample reveals a clear female predominance (81.7%), with a majority concentration in the 20-30 and 31-40 age groups. In terms of education, the high percentage of participants with Bachelor’s degrees and diplomas stands out, while doctorates represent a minority. Work experience is relatively evenly distributed among the different age groups, although there is a slight tendency towards those with more than 16 years of experience. With regard to the main occupation, primary care and hospital care account for most of the sample, while other areas such as teaching and social care are less represented (

Table 1).

3.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

An exploratory factor analysis with Promax rotation was conducted to identify the underlying structure of the 30 items in a sample of 202 participants. The analysis revealed a four-factor solution (

Table 2). Promax rotation was selected to allow for correlations between factors, which is consistent with the multidimensional nature of the constructs assessed (

Table 3). The resulting four factors presented high and consistent factor loadings. Reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, obtaining an

= 0.970, indicating high internal consistency (

Table 4). The adequacy of the data for factor analysis was confirmed by the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin index (KMO = 0.947) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (p < 0.001) (

Table 5 and

Table 6). These results support the proposed factor structure of four identified dimensions: Dimension 1: Intervention and referral (items 11; 19; 26; 27; 28; 29); Dimension 2: Detection and assessment of abuse (items 1; 2; 3; 4; 16; 17); Dimension 3: Documentation and recording (items 6; 7; 8; 9; 10; 13; 14; 15) and Dimension 4: Psychosocial support (items 5; 12; 20; 21; 22; 23).

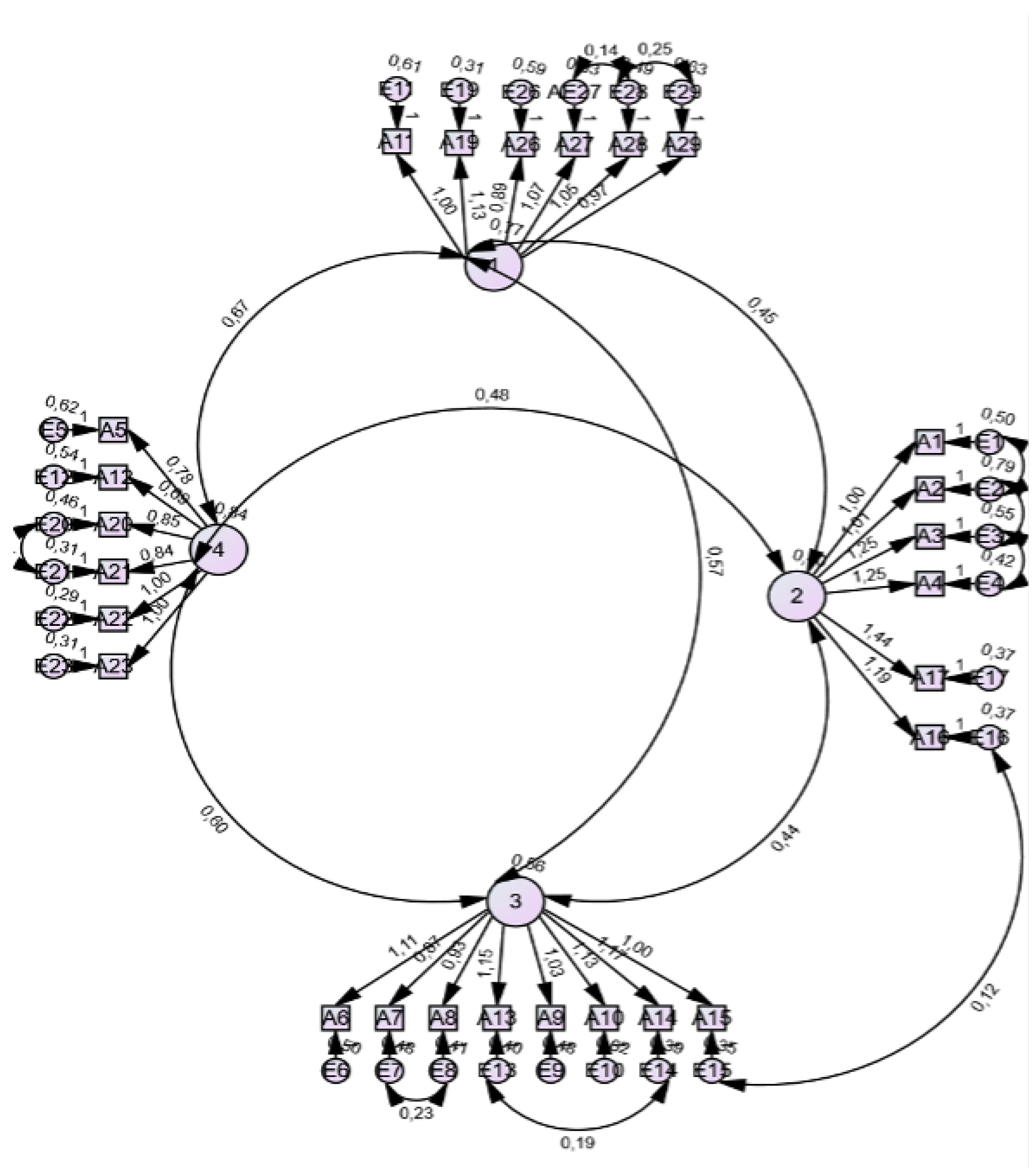

3.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

A confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to identify the underlying structure of the variables. Two models were compared: an initial model and a final model, obtained after the elimination of items with low factor loadings and high communality. The final model showed a better fit according to

/df =2.066; Parsimony= 720.736; RMR=.052; RMSEA (0.073); NFI (0.86); TLI (0.91); and CFI (0.92). These results suggest that the final model provides an adequate representation of the latent structure of the data (

Table 7). For this purpose, items 18, 24, 25 and 30 were removed for redundancy (

Figure 1).

4. Discussion

The instrument obtained from the present study demonstrates that the refinement of the initially developed scale has significantly improved its psychometric properties. By eliminating 4 redundant items, a superior internal consistency (

= 0.97) and a clearer factor structure have been achieved, supported by a KMO value of 0.947 and a significant Bartlett’s test of sphericity. This optimization is in line with existing literature, which emphasizes the importance of reducing redundancy to improve the accuracy and discriminant validity of scales [

7]. The findings of this study have important implications for assessing the nursing profession’s knowledge of intimate partner violence intervention. Given the scarce existence of tools for measuring professional practice, with the focus of the obtained scales being victim-oriented [

8], the professional’s attitude is extremely important for managing social and health resources [

9]. The refined scale allows for a more accurate assessment of the proposed dimensions, facilitating its application in clinical settings as an element of management and training of human resources, as well as part of research and undergraduate and postgraduate education. As we can see in the following study [

10] on gender-based violence among healthcare students and professionals currently practicing [

10], the lack of perception of this issue and the lack of knowledge about it are once again highlighted. The refined version of the scale provides a very efficient tool to assess the knowledge and practices of nursing activities in situations of intimate partner violence. It is a very useful tool for improving care and management.

For all these reasons, it is especially beneficial in clinical, research, and teaching contexts, as well as in the assessment of the quality of care for patients who are victims of intimate partner violence. A brief and specific scale facilitates the application and interpretation of results without sacrificing precision, allowing for the evaluation of the strengths of health professionals within the nursing field in order to train with precision. As we saw in the study [

11], the results indicated that training to detect and how to act was deficient, along with institutional barriers to case identification: ‘lack of time in the consultation (27.2%), absence of detection protocols for case management (22.8%), saturation of Health services (22.8%). Among the personal barriers to GBV were: disinterest of health personnel in identifying cases of GBV (29.4%)’ [

11]. With this scale, it is possible to measure the dimension affected within the nursing process (NP) and to act more specifically to solve the barriers.

On the other hand, it is pioneering because the scales are oriented towards gender-based violence against the victim, and this is the first nurse scale focused on the ability of professionals to view intimate partner violence in its totality, including all violence within any type of partnership imaginable [

12] as can be seen in: ‘Training should not be restricted or focused exclusively on violence against women; rather, it should be placed in the broader context of the study of gender inequalities in health and the biases arising from the lack of this perspective in both clinical practice and epidemiological research’." However, in all the literature consulted, there is no instrument to measure where nursing practice fails.

Finally, these data suggest that the scale is a valid and reliable tool for assessing nursing competencies in the field of detection, intervention, and support for victims of intimate partner violence. Robust psychometric properties were obtained, allowing for an accurate and structured assessment of the skills of nurses, with positive implications for improving the care and management of intimate partner violence cases in the healthcare setting. The refinement of these items allowed for the optimization of the accuracy and relevance of the factors measured by the scale, reducing the overlap of results.

Among the limitations of this study, it is important to note that the removal of items, while contributing to improved discriminant validity, may have reduced the breadth of coverage of the original construct. In future studies, it would be useful to explore the inclusion of items that maintain the specificity of each dimension without redundancy to ensure a complete measurement of the construct.

5. Conclusions

The Intimate Partner Violence Competency Scale for Nurses (IPVNCS) is a theoretically grounded, rigorous, and validated instrument with robust psychometric properties. It is designed to accurately assess the skills of nurses in the detection, intervention, and support of victims of intimate partner violence. Aligned with the NIC 6403 nursing intervention (

Table A1), the IPVNCS allows for a comprehensive and non-discriminatory assessment. The results of the validation confirm its reliability and usefulness for clinical practice, facilitating the identification of strengths and areas for improvement in the care of victims.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.C-B. and G.C-S.; methodology, JM.C-R.; software, D.C-B.; validation, N.M-G., L.G-R. and JM.C-R.; formal analysis, JC.C-R.; investigation, D.C-B.; resources, F.G-S.; data curation, N.M-G.; writing—original draft preparation, D-CB.X.; writing—review and editing, F.G-S.; visualization, F.G-S.; supervision, G.C-S.; project administration, L.G-R.; funding acquisition, F.GS. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded through the funds of the IDIPHISA Foundation (Research Institute of the Puerta de Hierro University Hospital), with which the Infanta Cristina University Hospital in Madrid was affiliated, grant number [XXX].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by or Ethics Committee of CEU San Pablo University (843/24/104).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, Perplexity Pro (Perplexity AI, version current as of December 2025) was used to improve the English language and readability of the text. The authors reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the final content of the publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IPV |

Intimate partner violence |

| IPVNCS |

Intimate Partner Violence Nursing Competency Scale |

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Nursing interventions against intimate partner violence, code. 6403: Support in the protection against partner abuse .

Table A1.

Nursing interventions against intimate partner violence, code. 6403: Support in the protection against partner abuse .

Investigate whether there are risk factors associated with domestic abuse (e.g., history of domestic violence, abuse,

rejection, over-criticism, or feelings of worthlessness and lack of love; difficulty trusting others or feelings of lack

of appreciation for others; feeling that asking for help is an indication of personal inadequacy; heightened need

for physical care; many family caregiving responsibilities; substance use; depression; serious psychiatric illnesses;

social isolation; poor relationship between partners; many marriages; pregnancy; poverty; unemployment; economic

dependence; homelessness; infidelity; divorce, or death of a loved one). Investigate whether there is a history of domestic abuse symptoms (e.g., numerous accidental injuries, multiple

somatic symptoms, chronic abdominal pain, chronic headaches, pelvic pain, anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress

syndrome, and other psychiatric disorders). Watch for signs and symptoms of physical abuse (e.g., numerous injuries at various stages of healing, unexplained

lacerations, bruises or bruises, hairless areas on the head, tie marks on the wrists or ankles; "defensive" bruises on the

forearms, and human bite marks). Watch for signs and symptoms of sexual abuse (e.g., semen or dried blood, lesions on the external genitalia, sexually

transmitted diseases, or dramatic behavior or health changes of undetermined etiology). Watch for signs and symptoms of emotional abuse (e.g., low self-esteem, depression, humiliation, and feelings of

defeat; overly cautious behavior toward a partner; self-harm or suicidal attitudes). Watch for signs and symptoms of exploitation (e.g., inadequate provision of basic needs when adequate resources are

available, deprivation of personal possessions, unexplained loss of social assistance, lack of knowledge of personal

finances or legal matters). Document evidence of physical abuse using standardized assessment tools and photographs. Document evidence of sexual abuse using standardized assessment tools and photographs. Listen carefully to the person who begins to talk about his or her own problems. Identify inconsistencies in the explanation of the cause of the injuries. Determine the correlation between the type of injury and the description of the cause. Interview the patient and/or someone else who knows the situation about the alleged abuse in the absence of the

partner. Encourage the admission of the patient for better observation and study, when appropriate. Observe and record partner interactions, as appropriate (e.g., recording the hours and duration of partner visits

during hospitalization, insufficient or exaggerated reactions by the partner). Observe if the individual shows excessive submission, such as passively submitting to hospital procedures. Observe if there is a progressive deterioration of the physical and/or emotional state of individuals. Observe if visits to clinics, emergencies or consultations with the doctor for minor problems are repeated. Establish a system for marking individual medical records in which there are suspicions of abuse. Provide positive affirmations about worth. Encourage the expression of concerns and feelings, including fear, guilt, shame, and self-blame. Provide support for victims to take action and make changes to prevent further retaliation. Help individuals and their families develop coping strategies in stressful situations. Help individuals and their families objectively assess the strengths and weaknesses of relationships. Refer individuals at risk of abuse or those who have suffered abuse to appropriate specialists and services (e.g., public

health services, social services, counseling, legal assistance). Refer the abusing spouse to appropriate specialists and services. Provide confidential information regarding shelters for people experiencing domestic violence, as appropriate. Initiate the development of a security plan to use if violence escalates. Report any situation where abuse is suspected in accordance with mandatory reporting laws. Initiate community education programs designed to reduce violence. Observe the use of resources of the community |

References

- Student, ClinicalKey. NANDA Taxonomy 2024. Retrieved November 10, 2024.

- Student, ClinicalKey. NOC Taxonomy 2024. Retrieved November 10, 2024.

- Student, ClinicalKey. NIC Taxonomy 2024. Retrieved November 10, 2024.

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA). European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. 2000. Retrieved November 22, 2024.

- Uysal Yalçın, S.; Zonp, Z.; Dinç, S.; Bilgin, H. An examination of effects of intimate partner violence on children: A cross-sectional study conducted in a paediatric emergency unit in Turkey. Journal of Nursing Management 2022, 30, 1648–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, P.; McGarry, J.; Younas, A.; Inayat, S.; Watson, R. Nurses’, midwives’ and students’ knowledge, attitudes and practices related to domestic violence: A cross-sectional survey. Journal of Nursing Management 2022, 30, 1434–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manuel Batista-Foguet, J.; Coenders, G.; Alonso, J. Análisis factorial confirmatorio. Su utilidad en la validación de cuestionarios relacionados con la salud. Medicina Clínica 2004, 122, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mejia, C.R.; Cardona-Rivero, A.; Galindo, V.; Teves-Arccata, M.; Chacon, J.I.; Fernández-Espíndola, L.; Martinez-Cornejo, I. Factores asociados con el machismo entre estudiantes de Medicina de ocho ciudades en cinco países Latinoamericanos. Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría 2023, 52, S70–S76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, R.; Basu, P. (Eds.) Family and Gendered Violence and Conflict: Pan-Continent Reach, 1st ed. 2024 ed.; Social Work; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, A.M.G. 6.a. Barreras de esfera individual: actitud 6.b. grado de formación y conocimientos 6.c. barreras organizativas. Redalyc.org n.d. Retrieved. 29 November 2024, p. 44.

- Mendoza-Flores, M.E.; Jesús-Corona, Y.D.; García-Urbina, M.; Martínez-Hernández, L.; Sánchez-Vera, R.; Reyes-Zapata, H. Conocimientos y actitudes del personal de enfermería sobre la violencia de género. Perinatol Reprod Hum 2005, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Bayas-Tixe, S.; Sastre-Rus, M. Intervenciones de enfermería para detectar la violencia de género en mujeres. 2020. Retrieved November 29, 2024.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).