Introduction

The commonsense advice to “

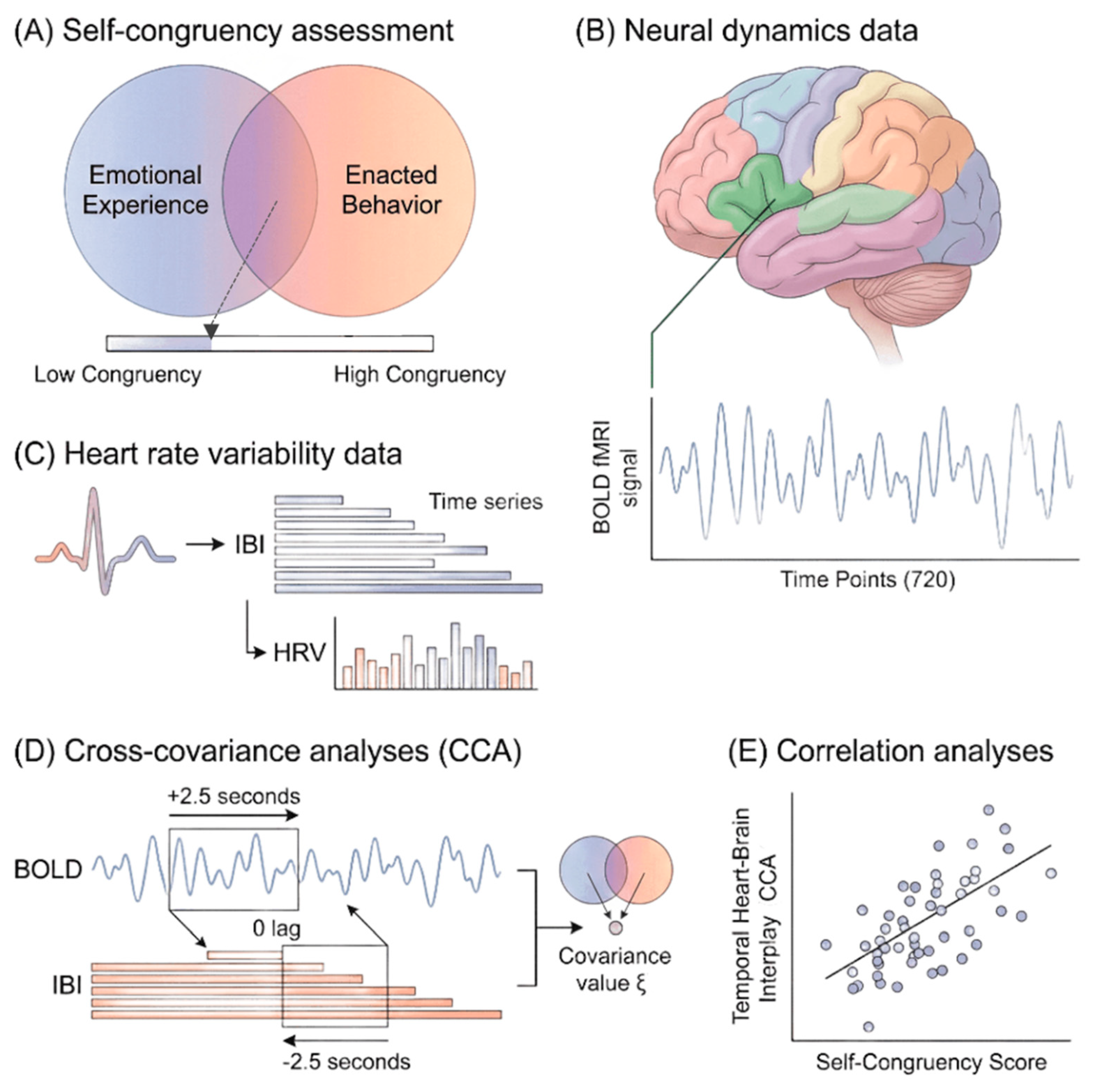

follow your heart” may be more than a metaphor. People often report greater well-being when their actions align with their inner emotions and values (Kernis & Goldman, 2006; Sheldon & Elliot, 1999). This alignment, referred to here as self-congruency, captures the coherence between what individuals feel and how they act. In this study, emotional experience denotes the individual’s ideal self-view and perceptions, and enacted behavior refers to their perceived actual self and actions, matching the operationalization used in the Methods. A simple graphical estimation, in which individuals overlap two circles representing these two dimensions (

Figure 1A), provides an intuitive measure of this construct. Indeed, higher self-congruency is associated with more positive life evaluations (Campbell et al., 1996) and greater subjective well-being (Light, 2017), underscoring its relevance for mental health as emphasized by the World Health Organization (2022b). By contrast, reduced coherence between inner states and outward behavior has been associated with emotional distress and regulatory difficulties (Sheldon et al., 1997; Berking & Wupperman, 2012). Thus, identifying physiological correlates of self-congruency may offer a promising avenue for biomarker in mental health.

The heart and brain maintain continuous bidirectional communication, primarily through the vagus nerve, the major parasympathetic pathway. The neurovisceral integration model (Thayer et al., 2009) proposes that neural systems involved in emotion, cognition, and self-regulation exert top-down influences on peripheral physiology (Thayer et al., 2012), while afferent cardiac signals reciprocally modulate brain states. As described by McCraty (2009), fluctuations in thoughts and emotions shape cardiac dynamics, and cardiac patterns in turn influence perceptual, emotional, and behavioral responses. Yet the temporal directionality of this interplay (i.e., whether cardiac inputs primarily drive neural changes or vice versa), remains unclear. Furthermore, it is unknown whether individuals with higher self-congruency exhibit a distinctive balance within this heart-brain communication compared to individuals with lower self-congruency. Establishing such patterns may contribute to identifying physiological markers of psychological coherence and in fine mental health.

Heart rate variability (HRV), the fluctuation in time intervals between successive heartbeats, reflects the dynamic interplay of sympathetic and parasympathetic influences. Since its formalization in the 1996 international consensus guidelines (Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology), HRV has been widely used as an index of autonomic regulation relevant to stress, cardiovascular health, and mental well-being (Thayer et al., 2012; Chalmers et al., 2014). Higher HRV indicates greater regulatory flexibility (i.e., the system’s ability to adjust efficiently to changing internal and external demands) (Appelhans & Luecken, 2006). This flexibility supports emotional stability, not as rigidity but as the capacity to maintain context-appropriate emotional states across fluctuations in environment and internal experience (Williams et al., 2015). Individuals with higher resting HRV typically show stronger emotion regulation capacity (Thayer et al., 2012) and better mental health outcomes (Chalmers et al., 2014; McCraty & Zayas, 2014; Park, 2019; Thayer & Lane, 2000). Although HRV is derived from beat-to-beat cardiac intervals, it primarily indexes autonomic influences acting on the heart rather than intrinsic myocardial activity. In this sense, HRV can be viewed as a regulated output (i.e., a peripheral readout of central autonomic processing), rather than a purely bottom-up cardiac driver. HRV may therefore contribute to provide a physiological window into self-congruency, particularly because the construct reflects the degree of coherence between one’s emotional experience and enacted behavior. Because this alignment involves the integration of internal states with outward action, it is expected to relate more strongly to integrative autonomic regulation (i.e., the coordinated engagement of both branches of the autonomic nervous system) than to vagal tone alone.

Neural dynamics also show intrinsic temporal variability. Metastability (i.e., the fluctuation of phase synchronization among large-scale neural networks) captures the brain’s capacity to reconfigure its coordination patterns over time (Deco & Kringelbach, 2016). Such variability supports flexible information processing and underlies emotion regulation and cognitive control (Lee & Frangou, 2017). Evidence links higher HRV with greater cognitive flexibility (Colzato et al., 2018), suggesting coordination between flexible cardiac and flexible neural systems. In line with the neurovisceral integration framework, low HRV is often associated with reduced adaptability (Friedman, 2007; Thayer & Lane, 2000). Collectively, these findings (Colzato et al., 2018; Friedman, 2007; McCraty & Zayas, 2014; Thayer et al., 2000; 2009; 2012) support our working hypothesis: flexible autonomic and neural dynamics facilitate the integration of emotions and actions, a process that may underlie self-congruency and could be leveraged as a potential biomarker of psychological coherence and in fine mental health.

Given that both self-congruency and heart–brain dynamics relate to emotion, cognition, behavior, and well-being (Campbell et al., 1996; Chalmers et al., 2014; Friedman, 2007; Light, 2017; McCraty & Zayas, 2014; Park, 2019; Thayer & Lane, 2000; Waugh et al., 2014), individuals whose cardiac signals exert stronger influence on neural activity may experience a more coherent alignment between internal states and outward behavior. The present study therefore examined whether self-congruency is associated with the temporal coupling and directional flow of heart–brain interactions (see

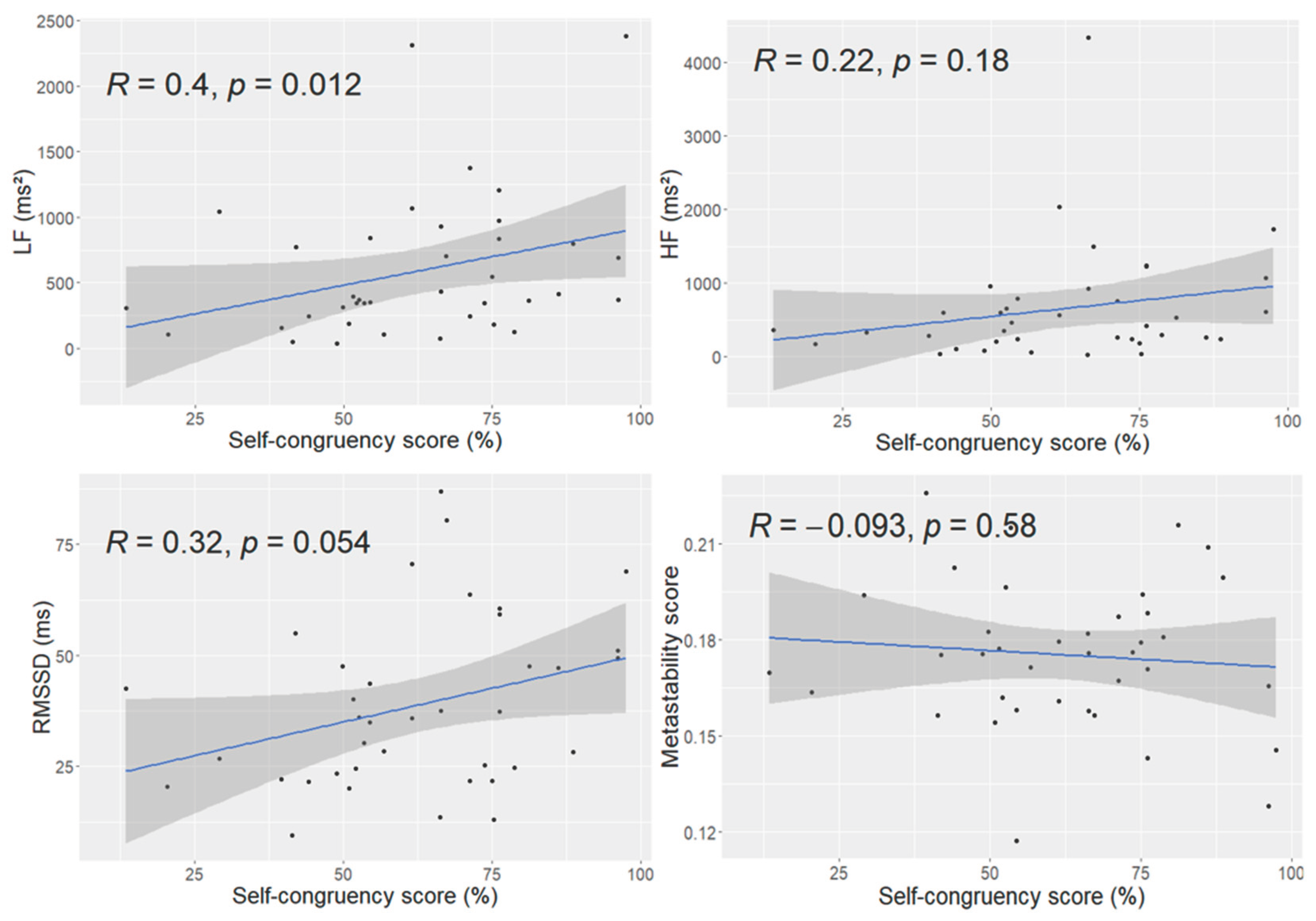

Figure 1). In framing these analyses, we further considered whether such temporal signatures might reflect candidate physiological markers relevant for mental health. Based on previous work (Chang et al., 2012; Mather et al., 2018; McCraty & Zayas, 2014; Tahsili-Fahadan & Geocadin, 2017; Thayer et al., 2009; Thayer & Lane, 2000), we predicted three outcomes: (1) higher self-congruency would be positively related to HRV metrics, but not necessarily to neural metastability; (2) heart-brain covariation would involve regions central to the neurovisceral integration model; and (3) greater self-congruency would be associated with stronger heart-to-brain directional influence.

Results

Demographic, Group Variables, and HRV Signal

The sample included thirty-eight participants whose demographic and behavioral characteristics are presented in

Table 1. No outliers were detected in fluid intelligence scores or anxiety levels, indicating that the sample was relatively homogeneous.

Across all 720 time points, inter-beat interval (IBI) values showed no significant association with anxiety levels (all p > 0.17, FDR-corrected) or fluid intelligence scores (all p > 0.20, FDR-corrected). These findings suggest that neither anxiety nor cognitive ability had a measurable influence on the HRV metrics used in this study.

Self-congruency scores showed substantial interindividual variability, ranging from 13.4% to 97.5%.

Temporal Relation Between Neural Dynamics and HRV

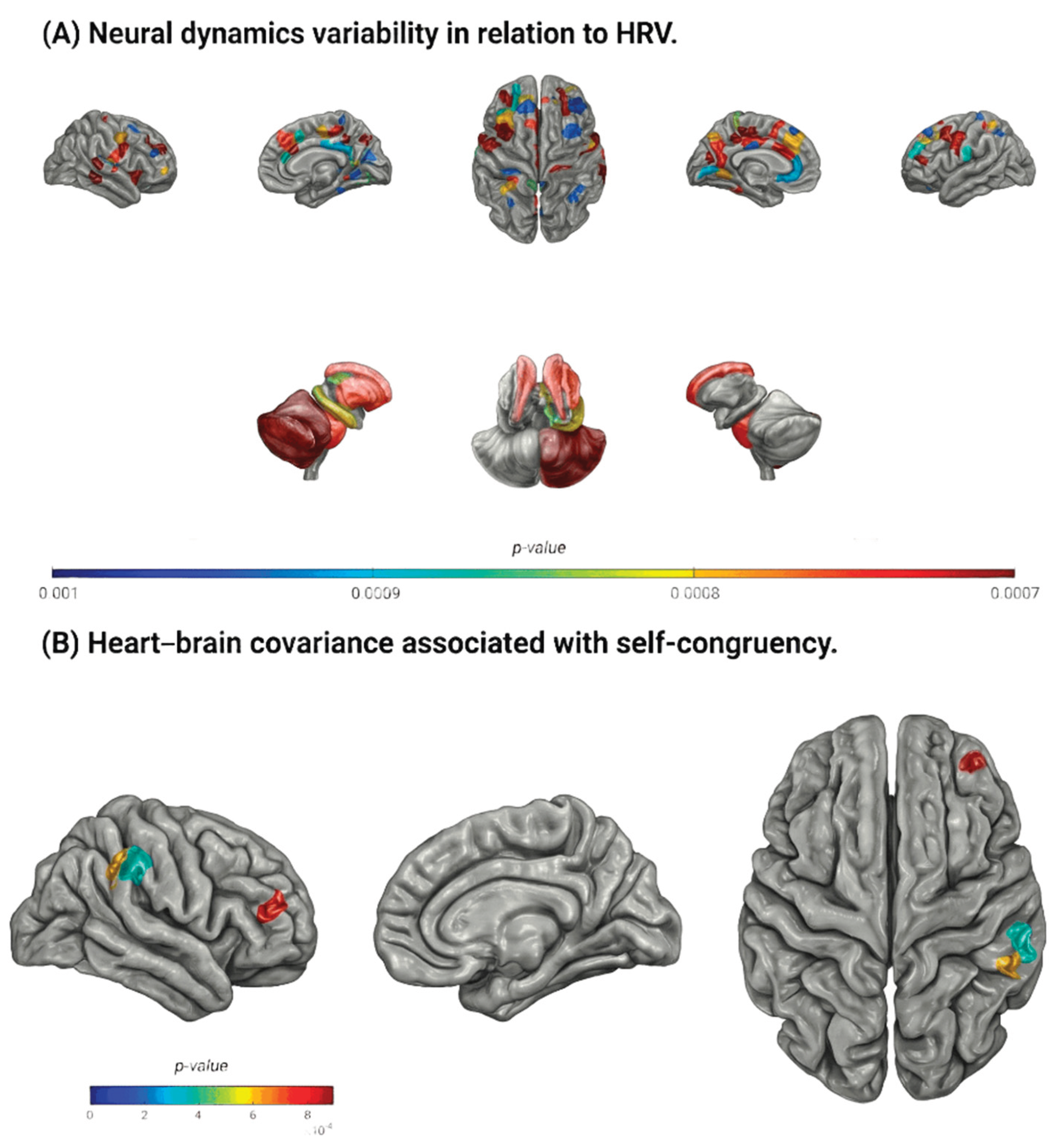

The temporal relation between neural dynamics variability and HRV revealed significant covariance when the two signals overlapped (t = 0) or when the BOLD signal preceded the IBI signal by 0.5-2.5 seconds, indicating predominant brain-to-heart directionality (88 regions at

p < 0.001; see

Supplementary C). Notably, the set of regions showing significant covariance when the BOLD signal was shifted 1 second before the IBI signal largely overlapped with those identified at all other significant shifts (

Figure 3A;

Supplementary C), reflecting a robust and consistent temporal pattern.

Among the eighty-eight regions showing significant covariance at the 1-second shift (

Supplementary D), several key functional systems were represented. These included components of the basal ganglia (e.g., caudate, putamen), subcortical structures (e.g., thalamus, hippocampus), the insular cortex, and widespread cortical regions. Specifically, thirty-three regions were located in the frontal lobe (e.g., rostral middle frontal, caudal middle frontal, superior frontal), nineteen in the parietal lobe (e.g., superior parietal, inferior parietal, precuneus), twelve in the limbic lobe (e.g., rostral and caudal anterior cingulate), eleven in the occipital lobe (e.g., cuneus, fusiform), and five in the temporal lobe (e.g., middle and superior temporal gyri). This broad distribution aligns with known components of the central autonomic and emotion-regulation networks.

Relation Between Heart-Brain Covariance and Self-Congruency

Three regions showed a significant positive correlation between heart–brain covariance and self-congruency when variability in IBIs, indexing autonomic modulation of cardiac activity, preceded regional BOLD fluctuations by 2.5 seconds, consistent with a heart-to-brain temporal ordering. This temporal window aligns with the typical latency of arterial baroreflex-mediated cardiovascular adjustments (approximately 2-3 seconds at resting heart rates), consistent with the observed stronger LF-BOLD associations relative to HF or RMSSD indices.

Higher self-congruency was associated with stronger heart-to-brain covariance in the right rostral middle frontal gyrus (

r(36) = 0.52,

p < 0.001;

Figure 3B) and in two sites within the right supramarginal gyrus (

r(36) > 0.51,

p < 0.001;

Figure 3B). These findings indicate that individuals whose emotional experience and enacted behavior are more aligned show enhanced cardiac influence on neural activity within regions implicated in emotion regulation and socio-emotional processing.

Table 2.

Relation between heart-to-brain covariance and self-congruency.

Table 2.

Relation between heart-to-brain covariance and self-congruency.

| Brain regions |

Shifts (s) |

| 2 |

2.5 |

| r |

p (10-4) |

r |

p (10-4) |

| rh-rostral middle frontal subregion 6 |

- |

NS |

0.52 |

8.93 |

| rh-supramarginal subregion 3 |

- |

NS |

0.52 |

7.85 |

| rh-supramarginal subregion 5 |

0.52 |

8.41 |

0.54 |

4.28 |

Discussion

The present study examined whether temporal signatures of cardiac-neural interaction relate to self-congruency, defined as the coherence between one’s emotional experience and enacted behavior. Although prior research has explored bidirectional heart-to-brain communication (Chang et al., 2012; McCraty et al., 2009; McCraty & Zayas, 2014), no previous work has characterized the temporal covariance between their respective signals nor tested whether this dynamic links to self-congruency. Our findings indicate that although group-level patterns reflect predominant top-down brain-to-heart influence, the higher the self-congruency the stronger the heart-to-brain coupling. Rather than identifying discrete subgroups, this pattern suggests the existence of a continuum of temporal heart-brain activity profiles, with enhanced bottom-up sensitivity emerging at the higher end of self-congruency. While preliminary, such variability hints at physiological signatures that could, in future work, inform the identification of individuals whose neurophysiological alignment or misalignment may carry relevance for mental health vulnerability. Indeed, both physiological regulation and psychological coherence are central to mental health (Campbell et al., 1996; Chalmers et al., 2014; Friedman, 2007; Light, 2017; McCraty & Zayas, 2014; Park, 2019; Thayer & Lane, 2000; Waugh et al., 2014), understanding how these domains intersect has relevance for identifying potential biomarkers of emotional well-being.

Self-congruency was positively associated with LF power, a marker influenced by both sympathetic and parasympathetic activity and tightly linked to baroreflex function (Minarini, 2020; Shaffer & Ginsberg, 2017). Enhanced baroreflex engagement is often interpreted as reflecting good self-regulatory capacity (Thayer & Lane, 2000). This suggests that greater coherence between emotional experience and enacted behavior may accompany stronger integrative autonomic regulation. RMSSD showed a positive trend in the same direction, whereas HF power (i.e., an index of vagal and respiratory sinus arrhythmia) did not relate to self-congruency. These findings support the view that self-congruency aligns more closely with integrated autonomic flexibility than with parasympathetic activity alone. A few physiological factors should temper interpretation of the LF-self-congruency association. Baroreflex sensitivity declines with age, raising the possibility that age-related autonomic variation could influence LF power; although age did not correlate with self-congruency in this sample, future studies should model this explicitly. In addition, recordings were acquired in the supine position, where baroreflex engagement is relatively reduced due to minimal hydrostatic load. Posture-dependent effects therefore cannot be ruled out and should be examined in follow-up work.

Neural metastability, a marker of dynamic coordination across large-scale networks (Deco & Kringelbach, 2016; Fingelkurts & Fingelkurts, 2004), showed no association with self-congruency. This null finding contrasts with the exploratory hypothesis that more flexible neural coordination might parallel alignment between emotional experience and enacted behavior. Its absence suggests that self-congruency may depend more strongly on interoceptive or affective signaling than on global fluctuations in neural synchrony. Future studies should examine additional indices of neural variability, especially those directly tied to emotion-related circuitry, to clarify which neural dynamic properties best capture psychological coherence.

A central aim of this study was to characterize the temporal relationship between cardiac and neural fluctuations. Group-level analyses showed that covariance emerged predominantly when neural activity coincided with or preceded cardiac fluctuations, reflecting a strong brain-to-heart temporal influence. This finding aligns with well-established models of vagal regulation, in which prefrontal and cingulate regions orchestrate autonomic output through the central autonomic network (Thayer & Lane, 2000; Thayer et al., 2009). Consistent with these models, significant covariance involved regions highly implicated in autonomic and emotion regulation, including the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, thalamus, insula, and basal ganglia, mirroring patterns reported in prior work using alternative analytic approaches (Chang et al., 2012; McCraty et al., 2009). These convergent findings underline the robustness of a physiological architecture wherein fluctuations in cardiovascular activity are closely tethered to neural systems that support self-regulation.

Although this top-down influence characterized the group, an important interindividual distinction emerged. Higher self-congruency was associated with stronger heart-to-brain covariance specifically when cardiac activity preceded neural fluctuations by 2-2.5 seconds. Given that HRV reflects autonomic regulation of the heart rather than intrinsic pacemaker activity, these heart-preceding-brain effects are best interpreted as the timing of autonomic adjustments captured peripherally at the heart, rather than direct myocardial signals driving neural responses. From this perspective, the temporal pattern observed here may index how strongly central networks integrate autonomic feedback in individuals with varying degrees of self-congruency.

Three right-hemisphere regions drove this association: two subregions of the supramarginal gyrus and one of the rostral middle frontal gyrus. The supramarginal gyrus supports socio-emotional functions such as empathy and the ability to differentiate self from other perspectives (Silani et al., 2013; Wada et al., 2021). The rostral middle frontal gyrus, within the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, plays a central role in emotion regulation, cognitive control, and empathy-related processing (Bruehl et al., 2013; Domínguez-Arriola et al., 2022; Enzi et al., 2016; Ochsner & Gross, 2005). The exclusive involvement of right-lateralized regions is consistent with theoretical accounts highlighting right-hemisphere specialization for affective, autonomic, and integrative processing (Thayer & Brosschot, 2005; Thayer et al., 2009; Thayer & Lane, 2000).

The temporal ordering of these associations (i.e., heart-preceding-brain), suggests that individuals with greater coherence may integrate cardiac signals more robustly into neural systems governing emotional and social cognition. This interpretation is consistent with, though not demonstrating, directional influence. Physiological cues from the heart may contribute to shaping neural processing in individuals whose actions and emotional experience are more coherent, potentially supporting self regulation. This view dovetails with broader evidence linking emotional coherence, self-regulatory capacity, and mental health (Berking & Wupperman, 2012; McCraty & Zayas, 2014; WHO, 2022b). Given the global burden of mental health disorders (WHO, 2022a), physiological signatures that reflect emotional–behavioral alignment may hold translational potential for assessing well-being or monitoring intervention effects, pending replication in larger or clinical cohorts.

Several exploratory considerations emerged. Preliminary observations suggested slightly higher self-congruency among men in this sample, though larger samples are required to evaluate gender differences in heart-to-brain coupling. Developmental research would also be informative, as HRV and neural dynamics change markedly from childhood through adulthood (Gogtay et al., 2004). Further, integrating gut physiology, a system often intuitively linked to decision-making, may advance understanding of broader interoceptive contributions to emotional coherence.

Limitations should be noted. Self-congruency was measured using a graphic estimation procedure that would benefit from validation against standardized questionnaires. Respiration, which influences HF-HRV and may shape heart-brain associations (Chang et al., 2012; Saboul et al., 2013), was not recorded; incorporating respiratory monitoring would refine future physiological interpretations. Although PPG sampling introduces slightly lower precision in beat-to-beat timing than ECG, PPG contains additional information about peripheral vascular dynamics that could be leveraged in future analyses to dissociate central cardiac modulation from vascular influences. The present study focused on time-domain cross-covariance, which quantifies the strength and timing of shared fluctuations between neural and cardiac signals. Complementary spectral or time–frequency descriptions could characterize the frequency structure of these shared dynamics, although they would not replace covariance as a measure of association strength. Integrating these approaches in future work may offer a more complete picture of multiscale heart–brain coupling. Finally, because HRV indexes autonomic regulation rather than intrinsic cardiac output, references to “cardiac influence” in this work should be understood as reflecting autonomic feedback captured at the heart, rather than direct myocardial signals acting on the brain.

In summary, individuals who report stronger coherence between their emotional experience and enacted behavior exhibit enhanced cardiac influence on neural regions supporting emotion regulation and social-emotional processing. Although the group-level pattern reflects predominant top-down control, interindividual variation in bottom-up cardiac sensitivity appears to track psychological coherence. These findings highlight a promising physiological–psychological axis and outline a potential pathway for biomarker development. The familiar advice to “follow your heart” acquires empirical nuance here: coherence between the heart’s signals and the brain’s regulatory systems may be a meaningful feature of emotional well-being.

Methods

Procedure

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the local Ethics Committee (Vaud CER PB_2016-02008, 204/15). Data were collected during a single 90-minute session. Participants first received an oral explanation of the study procedures and provided written informed consent. The session included a behavioral and cognitive assessment followed by MRI acquisition of anatomical and resting-state functional data. A photoplethysmography (PPG) sensor (Siemens Prisma, Germany) was placed on the tip of the right index finger, and pulse data were recorded simultaneously with the MRI acquisition.

Participants

Forty-four adults (29 females) were initially recruited for this study. All participants were healthy volunteers with no history of neurological disorders. Data from six individuals were excluded due to technical issues with physiological recordings (n = 5) or data-processing failure (n = 1), resulting in a final sample of thirty-eight adults (26 females; age range: 17.0–63.2 years; mean ± SD: 31.2 ± 12.5.

Group Variables

Because cognitive abilities can influence HRV regulation (Colzato et al., 2018), fluid intelligence was assessed using the Standard Progressive Matrices, a nonverbal reasoning test first developed by Raven (1936). The task comprises five sets of twelve incomplete visual matrices to be completed within 15 minutes. For each item, participants select the correct missing element from several response options, with difficulty increasing across sets. Scores correspond to the total number of correct responses (maximum = 60), with higher scores indicating greater fluid intelligence.

Given that anxiety can also modulate HRV metrics (Chalmers et al., 2014), participants completed the short form of the State–Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-SF), developed by Marteau and Bekker (1992) based on Spielberger’s original instrument (1984). The STAI-SF includes six items rated on a 1–6 scale, yielding total scores between 6 and 36. Higher scores reflect higher levels of self-reported anxiety.

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

Neural Data

MRI data were acquired on a Siemens 3T Magnetom Prisma scanner equipped with a 64-channel head coil at the BioMedical Imaging Center (CIBM), University Hospital of Lausanne (CHUV-UNIL, Switzerland). Participants wore ear protection to reduce scanner noise, and foam padding was used to minimize head motion. A high-resolution 3D T1-weighted anatomical image (MPRAGE; TR = 500 ms, TE = 2.47 ms; 208 slices; voxel size = 1 × 1 × 1 mm; flip angle = 8°) was acquired as the anatomical reference for a 6-minute resting-state fMRI scan. Functional images were collected using a multiband gradient-echo echo-planar imaging sequence sensitive to blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) contrast (voxel size = 2.2 × 2.2 × 3 mm; multiband factor = 4; TR (repetition time) = 500 ms (2 Hz); 720 volumes; total duration = 6 min).

Preprocessing was performed with the fMRIPrep automated pipeline (Esteban et al., 2019), part of the NiPreps suite (NiPreps Documentation Team, 2020). Anatomical preprocessing included construction of a T1w reference image (conformed to RAS orientation and uniform voxel size), skull stripping, brain tissue segmentation, and nonlinear normalization to a standard template. Functional preprocessing involved generating a reference BOLD image, estimating head motion, and applying susceptibility distortion correction to account for field inhomogeneities.

From the preprocessed BOLD data, mean time series were extracted for each of the 506 anatomical regions of interest defined by the Lausanne 2018 symmetric atlas (Hagmann et al., 2008). For each region, activity values were averaged across all 720 time points (Griffa et al., 2017) to reconstruct regional neural dynamics (

Figure 1B).

Neural metastability, a measure of neural dynamics variability and adaptive flexibility (Deco & Kringelbach, 2016; Fingelkurts & Fingelkurts, 2004), was computed using an in-house MATLAB script. Metastability was defined as the standard deviation of the Kuramoto order parameter over time (Deco et al., 2017), yielding an individual metastability score for each participant.

Heart Rate Variability Data

Photoplethysmography (PPG) was recorded at 200 Hz throughout the 6-minute resting-state fMRI acquisition. Beat-to-beat intervals were extracted directly from the PPG signal. Because sampling rates below 250 Hz can introduce temporal jitter in peak estimation (Malik, 1996; Merri et al., 1990), the theoretical temporal precision at 200 Hz is limited to a 5 ms resolution. To refine peak localization, a second-order polynomial was fit around each detected peak using four neighboring samples (two preceding and two following), and the heartbeat was defined as the maximum of the interpolated polynomial. A second-order interpolation was selected because it provides sufficient precision for peak localization without introducing the sensitivity to noise that can accompany higher-order fits. We used inter-peak intervals as a surrogate for Inter-beat intervals (IBIs), which were computed as the time difference between successive peaks (

Figure 1C) and served as the basis for HRV analysis.

IBIs were processed (HRV Task Force, 1996) to identify and remove ectopic beats using both an automated detection algorithm and visual inspection (Bourdillon et al., 2022). Ectopic beats were corrected via interpolation to obtain normal-to-normal (NN) intervals. From these NN intervals, we extracted three standard HRV metrics: root mean square of successive differences (RMSSD), and spectral power in the low-frequency (LF; 0.04–0.15 Hz) and high-frequency (HF; 0.15–0.40 Hz) bands, expressed in ms² (Schmitt et al., 2015; Thorpe et al., 2016). RMSSD is a widely used time-domain index of vagally mediated HRV (Minarini, 2020; Shaffer & Ginsberg, 2017). LF reflects a combination of sympathetic and parasympathetic influences, including baroreflex-driven activity, whereas HF primarily represents parasympathetic activity and respiratory sinus arrhythmia (Minarini, 2020; Shaffer & Ginsberg, 2017).

Spectral power density was computed using a fast Fourier transform applied to NN intervals resampled at 2 Hz with a window length of 250 data points and 50% overlap. The 2 Hz resampling frequency matches the 720-time-point structure of the 6-minute fMRI acquisition and adheres to recommended HRV analysis standards (Malik, 1996). All HRV computations were performed in MATLAB® (R2019a, MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA). The raw PPG waveform also contains information about peripheral vascular dynamics and breathing-related oscillations. These components were not analyzed in the present study, which was specifically focused on autonomic modulation indexed by HRV. Future work could exploit the full PPG signal to disentangle cardiac, vascular, and respiratory contributions to heart-brain coupling.

Self-Congruency Data

Self-congruency was assessed using a graphic rating scale in which participants adjusted the overlap between two circular cardboards representing their emotional experience and enacted behavior. Participants were instructed to position the circles to reflect the extent to which they perceived these two aspects of themselves to match. Greater overlap indicated higher self-congruency.

Both circles were identical in size, each with radius

r. To quantify the overlap, the distance

d between the centers of the two circles was measured (

Figure 1A). The area of intersection was then computed using the standard formula:

(as detailed in

Supplementary A). Because the aim was to express self-congruency as a simple percentage, this intersection area was converted into a proportional score by dividing it by the total area of one circle (

πr²) and multiplying by 100. Thus, the final self-congruency value reflected the percentage of overlap between the two circles.

Data Analysis

Demographic, Group Variables and HRV Signal

Descriptive statistics for demographic variables and group measures were computed using RStudio (version 4.2.2). To assess whether anxiety or fluid intelligence influenced the inter-beat interval (IBI) time series, correlations were calculated at each of the 720 time points using MATLAB® (R2022b, MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA). A significance threshold of p< 0.001 was applied, and multiple comparisons were corrected using the false discovery rate (FDR) procedure at 0.001 (Groppe, 2022, MATLAB Central File Exchange).

Temporal Relation Between Neural Dynamics and HRV

Temporal coupling between neural dynamics and HRV was examined using cross-covariance analysis (CCA) applied to the preprocessed BOLD time series and IBI signal. CCA estimates the similarity between two signals across a range of temporal delays. For each participant, CCA was computed across delays from −2.5 to +2.5 seconds (

Figure 1D;

Supplementary B), reflecting biologically plausible conduction delays between cardiac and neural activity (Silvani et al., 2016). Negative delays indicate the BOLD signal shifted ahead of the IBI signal, whereas positive delays indicate the IBI signal shifted ahead of the BOLD signal.

For each delay, 506 cross-covariance values were obtained, one for each brain region of interest, yielding eleven total delays: five with BOLD leading, five with IBI leading, and one zero-lag condition. For each region and delay, the reported value corresponds to the peak (maximum absolute) of the cross-covariance function within the overlapping segment of the two signals. To assess group-level effects, Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were performed at each delay across participants. Significance was defined as p (FDR-corrected) < 0.001 using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure (fdr_bh; Groppe, 2022). All CCA and nonparametric analyses were conducted in MATLAB® (R2022b).

Relation Between Heart-Brain Covariance and Self-Congruency

To explore whether heart-to-brain temporal covariance was associated with self-congruency, correlations were computed across participants using CCA values as the dependent measures and self-congruency scores as the predictor. Brain regions showing associations at p < 0.001 were considered significant. Given that the correlations with self-congruency served as an exploratory brain-behavior analysis rather than a confirmatory test, we report results at an uncorrected threshold of p < 0.001 to avoid excessive Type II error while still applying a stringent criterion. These analyses were performed in MATLAB® (R2022b).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

S.D. designed the study; S.D., A.R., N.R., and J.B.-L. collected the data; N.R., E.F., N.B., S.U., and C.B. preprocessed and analyzed the data; S.D and Y.A.G. did data visualization, S.D., N.R, and N.B. wrote the paper; all authors reviewed the paper.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the local Ethics Committee (Vaud CER PB_2016-02008, 204/15, date 2021-11-30).

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the participants. We thank Sarah Boillat, Coline Grasset and Philippe Eon Duval for helping with data preparation, and Emeline Mullier for early data visualization. This research was financially supported by The Société Académique Vaudoise.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Appelhans, B. M.; Luecken, L. J. Heart Rate Variability as an Index of Regulated Emotional Responding. Review of General Psychology 2006, 10(3), 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berking, M.; Wupperman, P. Emotion regulation and mental health: Recent findings, current challenges, and future directions. In Current Opinion in Psychiatry; 2012; Vol. 25, Issue 2, pp. 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdillon, N.; Yazdani, S.; Vesin, J.-M.; Schmitt, L.; Millet, G. P. RMSSD Is More Sensitive to Artifacts Than Frequency-Domain Parameters: Implication in Athletes’ Monitoring. ©Journal of Sports Science and Medicine 2022, 21, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruehl, H.; Preißler, S.; Heuser, I.; Heekeren, H. R.; Roepke, S.; Dziobek, I. Increased Prefrontal Cortical Thickness Is Associated with Enhanced Abilities to Regulate Emotions in PTSD-Free Women with Borderline Personality Disorder. PLoS ONE 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, J. D.; Trapnell, P. D.; Heine, S. J.; Katz, I. M.; Lavallee, L. F.; Lehman, D. R. Self-Concept Clarity: Measurement, Personality Correlates, and Cultural Boundaries. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1996, 70(1), 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, J. A.; Quintana, D. S.; J-Anne Abbott, M.; Kemp, A. H.; Raquel Soares Ouakinin, S.; Marie Lachowski, A. Anxiety disorders are associated with reduced heart rate variability: a meta-analysis 2014. [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Metzger, C. D.; Glover, G. H.; Duyn, J. H.; Heinze, H. J.; Walter, M. Association between heart rate variability and fluctuations in resting-state functional connectivity. NeuroImage 2012, 68, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colzato, L. S.; Jongkees, B. J.; De Wit, Matthijs; Melle; van der Molen, J. W.; Steenbergen, L. Variable heart rate and a flexible mind: Higher resting-state heart rate variability predicts better task-switching. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience 2018, 18(4), 730–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dattani, S.; Ritchie, H.; Roser, M. Mental Health. Our World in Data. 2021. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/mental-health.

- Deco, G.; Kringelbach, M. L. Metastability and Coherence: Extending the Communication through Coherence Hypothesis Using A Whole-Brain Computational Perspective. Trends in Neurosciences 2016, 39(3), 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deco, G.; Kringelbach, M. L.; Jirsa, V. K.; Ritter, P. The dynamics of resting fluctuations in the brain: Metastability and its dynamical cortical core. Scientific Reports 2017, 7(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Wei, D.; Xue, S.; Du, X.; Hitchman, G.; Qiu, J. Regional gray matter density associated with emotional conflict resolution: evidence from voxel-based morphometry. Neurosciences 2014, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Arriola, M. E.; Víctor, ·; Olalde-Mathieu, E.; Garza-Villarreal, E. A.; Fernando, ·; Barrios, A. The Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex Presents Structural Variations Associated with Empathy and Emotion Regulation in Psychotherapists. Brain Topography 2022, 35, 613–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enzi, B.; Amirie, S.; Brüne, · Martin. Empathy for pain-related dorsolateral prefrontal activity is modulated by angry face perception. Experimental Brain Research 2016, 234, 3335–3345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban, O.; Markiewicz, C. J.; Blair, R. W.; Moodie, C. A.; Ilkay Isik, A.; Erramuzpe, A.; Kent, J. D.; Goncalves, M.; DuPre, E.; Snyder, M.; Oya, H.; Ghosh, S. S.; Wright, J.; Durnez, J.; Poldrack, R. A.; Gorgolewski, K. J. fMRIPrep: a robust preprocessing pipeline for functional MRI. Nature Methods 2019, 16, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fetterman, A. K.; Robinson, M. D. Do you use your head or follow your heart? Self-location predicts personality, emotion, decision making, and performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2013, 105(2), 316–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fingelkurts, A. A.; Fingelkurts, A. A. Making complexity simpler: Multivariability and metastability in the brain. International Journal of Neuroscience 2004, 114(7), 843–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, B. H. An autonomic flexibility–neurovisceral integration model of anxiety and cardiac vagal tone. Biological Psychology 2007, 74(2), 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gogtay, N.; Giedd, J. N.; Lusk, L.; Hayashi, K. M.; Greenstein, D.; Vaituzis, A. C.; Nugent, T. F., III; Herman, D. H.; Clasen, L. S.; Toga, A. W.; Rapoport, J. L.; Thompson, P. M. Dynamic mapping of human cortical development during childhood through early adulthood. PNAS 2004, Vol. 101. Available online: https://www.pnas.org. [CrossRef]

- Griffa, A.; Ricaud, B.; Benzi, K.; Bresson, X.; Daducci, A.; Vandergheynst, P.; Thiran, J. P.; Hagmann, P. Transient networks of spatio-temporal connectivity map communication pathways in brain functional systems. NeuroImage 2017, 155, 490–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagmann, P.; Cammoun, L.; Gigandet, X.; Meuli, R.; Honey, C. J. Mapping the structural core of human cerebral cortex. PLoS Biol 2008, 6(7), 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homma, I.; Masaoka, Y. Breathing rhythms and emotions. Experimental Physiology 2008, 93(9), 1011–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kernis, M.; Goldman, B. M. A Multicomponent Conceptualization of Authenticity: Theory and Reseach. Psychology 2006, 38, 283–357. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Frangou, S. Linking functional connectivity and dynamic properties of resting-state networks. Scientific Reports 2017, 7(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Light, A. E. Self-Concept Clarity, Self-Regulation, and Psychological Well-Being. Self-Concept Clarity 2017, 177–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M. Heart rate variability Standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. European Heart Journal 1996, 17, 354–381. Available online: http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/. [CrossRef]

- Marteau, T. M.; Bekker, H. The development of a six-item short-form of the state scale of the Spielberger State—Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). British Journal of Clinical Psychology 1992, 31(3), 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mather, M.; Thayer, J.; Ave, M.; Opin Behav Sci Author manuscript, C. How heart rate variability affects emotion regulation brain networks. Curr Opin Behav Sci 2018, 19, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCraty, R.; Atkinson, M.; Tomasino, D.; Bradley, R. T. The Coherent Heart Heart-Brain Interactions, Psychophysiological Coherence, and the Emergence of System-Wide Order. REVIEW December 2009, Vol. 5(Issue 2). [Google Scholar]

- McCraty, R.; Zayas, M. A. Cardiac coherence, self-regulation, autonomic stability and psychosocial well-being. Frontiers in Psychology 2014, 5(SEP), 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merri, M.; Farden, D. C.; Mottley, J. G.; Titlebaum, E. L. Sampling Frequency of the Electrocardiogram for Spectral Analysis of the Heart Rate Variability. IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON BIOMEDICAL ENGINEERING; 1990; Vol. 37. [Google Scholar]

- Michalski, L. J. Rostral Middle Frontal Gyrus Thickness is Associated with Perceived Stress and Depressive Symptomatology. Washington University, 2016. Available online: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds.

- Minarini, G. Root Mean Square of the Successive Differences as Marker of the Parasympathetic System and Difference in the Outcome after ANS Stimulation. In Autonomic Nervous System Monitoring - Heart Rate Variability; IntechOpen, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejati, V.; Majdi, R.; Salehinejad, M. A.; Nitsche, M. A. The role of dorsolateral and ventromedial prefrontal cortex in the processing of emotional dimensions. Scientific Reports 2021, 11(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochsner, K. N.; Gross, J. J. The cognitive control of emotion. In Trends in Cognitive Sciences; Elsevier Ltd, 2005; Vol. 9, Issue 5, pp. 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palva, S.; Palva, J. M. New vistas for α-frequency band oscillations. Trends in Neurosciences 2007, 30(4), 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, G. The Mental Health from the Self-Regulation Perspective; What Research on Heart Rate Variability Revealed about the Interaction between Self-Regulation and Executive Attention Dysfunction In Acute Kidney Injury And Sex-Specific Implications. Medical Research Archives 2019, 7(3). Available online: http://journals.ke-i.org/index.php/mra.

- Saboul, D.; Pialoux, V.; Hautier, C. The impact of breathing on HRV measurements: Implications for the longitudinal follow-up of athletes. European Journal of Sport Science 2013, 13(5), 534–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallet, J.; Mars, R. B.; Noonan, M. P.; Neubert, F.-X.; Jbabdi, S.; O’reilly, J. X.; Filippini, N.; Thomas, A. G.; Rushworth, M. F. The Organization of Dorsal Frontal Cortex in Humans and Macaques. The Journal of Neuroscience 2013, 33(30), 12255–12274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, L.; Regnard, J.; Parmentier, A. L.; Mauny, F.; Mourot, L.; Coulmy, N.; Millet, G. P. Typology of Fatigue by Heart Rate Variability Analysis in Elite Nordic-skiers. International Journal of Sports Medicine 2015, 36(12), 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, F.; Ginsberg, J. P. An Overview of Heart Rate Variability Metrics and Norms. Front. Public Health 2017, 5, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheldon, K. M.; Elliot, A. J. Goal striving, need satisfaction, and longitudinal well-being: The self-concordance model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1999, 76(3), 482–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, K. M.; Ryan, R. M.; Rawsthorne, L. J.; Ilardi, B. Trait self and true self: Cross-role variation in the Big-Five personality traits and its relations with psychological authenticity and subjective well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1997, 73(6), 1380–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silani, G.; Lamm, C.; Ruff, C. C.; Singer, T. Right supramarginal gyrus is crucial to overcome emotional egocentricity bias in social judgments. Journal of Neuroscience 2013, 33(39), 15466–15476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvani, A.; Calandra-Buonaura, G.; Dampney, R. A. L.; Cortelli, P. Brain-heart interactions: Physiology and clinical implications. In Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences; Royal Society of London, 2016; Vol. 374, Issue 2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielberger, C. D.; Vagg, P. R. Psychometric Properties of the STAI: A Reply to Ramanaiah, Franzen, and Schill. Journal of Personality Assessment 1984, 48(1), 95–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahsili-Fahadan, P.; Geocadin, R. G. Heart–Brain Axis. Circulation Research 2017, 120(3), 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology the North American Society of Pacing Electrophysiology. Heart Rate Variability. Circulation 1996, 93(5), 1043–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thayer, J. F.; Åhs, F.; Fredrikson, M.; Sollers, J. J.; Wager, T. D. A meta-analysis of heart rate variability and neuroimaging studies: Implications for heart rate variability as a marker of stress and health. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2012, 36(2), 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thayer, J. F.; Brosschot, J. F. Psychosomatics and psychopathology: looking up and down from the brain. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2005, 30(10), 1050–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thayer, J. F.; Hansen, A. L.; Saus-Rose, E.; Psychol, C. B. Heart Rate Variability, Prefrontal Neural Function, and Cognitive Performance: The Neurovisceral Integration Perspective on Self-regulation, Adaptation, and Health. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 2009, 37(2), 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thayer, J. F.; Lane, R. D. A model of neurovisceral integration in emotion regulation and dysregulation. Journal of Affective Disorders 2000, 61(3), 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorpe, R. T.; Strudwick, A. J.; Buchheit, M.; Atkinson, G.; Drust, B.; Gregson, W. Tracking morning fatigue status across in-season training weeks in elite soccer players. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance 2016, 11(7), 947–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, S.; Honma, M.; Masaoka, Y.; Yoshida, M.; Koiwa, N.; Sugiyama, H.; Iizuka, N.; Kubota, S.; Kokudai, Y.; Yoshikawa, A.; Kamijo, S.; Kamimura, S.; Ida, M.; Ono, K.; Onda, H.; Izumizaki, M. Volume of the right supramarginal gyrus is associated with a maintenance of emotion recognition ability. PLoS ONE 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waugh, C. E.; Lemus, M. G.; Gotlib, I. H. The role of the medial frontal cortex in the maintenance of emotional states. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2014, 9(12), 2001–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D. W. P.; Cash, C.; Rankin, C.; Bernardi, A.; Koenig, J.; Thayer, J. F. Resting heart rate variability predicts self-reported difficulties in emotion regulation: A focus on different facets of emotion regulation. Frontiers in Psychology 2015, 6(MAR). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolff, N.; Zink, N.; Stock, A. K.; Beste, C. On the relevance of the alpha frequency oscillation’s small-world network architecture for cognitive flexibility. Scientific Reports 2017, 7(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Mental disorders. 8 June 2022a. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-disorders.

- World Health Organization. Mental health: strengthening our response. 17 June 2022b. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).