1. Introduction

Emotion regulation (ER) is a fundamental component of mental health and psychological resilience, encompassing the processes individuals use to modify their emotional experiences, expressions, and related physiological responses based on contextual demands [

1]. ER difficulties are related to multiple affective, anxiety, and personality disorders and, in turn, lead to impaired psychosocial functioning and poor well-being [

2,

3]. One of the better and most adaptable ways to handle emotions is cognitive reappraisal (CR), which means changing how we think about a situation that causes strong feelings to lessen its emotional effect [

4].

CR has various subtypes, such as positive reappraisal (emphasizing the advantages of negative circumstances), fictional reappraisal (reinterpreting emotionally impactful fictional narratives), and distancing (assuming a detached or third-person viewpoint) [

5,

6]. These strategies assist individuals in deliberately diminishing unpleasant affect and fostering more adaptive emotional viewpoints. Nonetheless, individual disparities in the ability to execute CR efficiently may be affected by variations in cognitive resources and neurobiological functioning [

7,

8]

Functional neuroimaging research has delineated a network of cerebral areas implicated in cognitive ER, notably the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) [

9,

10]. The dlPFC is mostly linked to working memory and the preservation of regulatory objectives [

11]. On the other hand, the vmPFC is essential for synthesizing emotional information and assessing the affective relevance of inputs [

12]. In cognitive control, these regions interact whereby the dlPFC is believed to exert a top-down influence on the vmPFC, which subsequently modulates activity in limbic structures, especially the amygdala [

11,

13]. The unique functional roles of these regions in various reappraisal procedures are inadequately investigated, along with the impact of direct activation of each area on the ER effectiveness [

14].

Alongside neural measures, psychophysiological indicators such as heart rate (HR), skin conductance (SC), and respiration rate (RR) offer objective metrics of emotional arousal and regulation effectiveness. Elevated autonomic activity often indicates intensified emotional arousal [

15], while positive CR has been linked to decreases in heart rate and, at times, skin conductance response [

16,

17]. Recent research indicates that RR, albeit less examined, interacts bidirectionally with emotional processing [

18].

Non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS) techniques, especially transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), have arisen as effective methods for influencing emotional and cognitive functions by modifying cortical excitability [

19]. Considering the pivotal function of the prefrontal cortex in ER, tDCS presents an intriguing approach for augmenting regulatory abilities via focused neuronal stimulation [

20]. This method entails the administration of a low-intensity electrical current to targeted cortical areas, resulting in polarity- and the influences on neuronal excitability and functional connectivity are dependent on the area, as noted by Nitsche and Paulus (2000).

Increasing data suggests that anodal tDCS targeting the dlPFC improves executive functioning, fortifies top-down cognitive control, and diminishes emotional reactivity [

22,

23]. These findings indicate that altering prefrontal activity may enhance the application of emotion management methods, including CR. However, most current research has focused primarily on the dlPFC, while only a few studies have investigated the effects of activating the vmPFC, which is essential for emotional appraisal and limbic modulation [

24].

Furthermore, direct comparisons of dlPFC and vmPFC stimulation for multimodal outcomes - involving both physiological and subjective measures - are scarce. Even fewer studies have investigated how the stimulation of these regions interacts with various cognitive regulation strategies or evaluated these interactions within ecologically valid paradigms, such as the utilization of emotionally evocative film clips, which more accurately reflect real-world emotional experiences than static images or hypothetical scenarios [

25].

Therefore, there is a critical need to clarify how targeted neuromodulation interacts with distinct CR strategies to regulate emotional responses, particularly when assessed through psychophysiological measures in ecologically valid contexts - such as emotionally evocative film clips, which offer greater realism than static images.

This study aimed to see if using tDCS on either the dlPFC or vmPFC could improve the effectiveness of CR techniques in regulating bodily responses, such as HR, SC, and RR, is crucial when watching emotionally negative film clips. The primary objective was to assess whether active tDCS (to the dlPFC or vmPFC), in combination with CR strategies (positive reappraisal, fictional reappraisal, or distancing), would lead to greater reductions in autonomic arousal compared to sham stimulation.

The study also pursued three secondary objectives. First, it aimed to evaluate target-specific effects by comparing the differential impact of dlPFC versus vmPFC stimulation on psychophysiological responses during CR. Second, it sought to examine subjective emotional responses by measuring changes in self-reported positive and the study measured negative affect using the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) and assessed perceived side effects with the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) from pre- to post-intervention. Third, the study aimed to assess the effectiveness of blinding by evaluating participants’ beliefs regarding whether they received active or sham stimulation, along with their confidence in these judgments.

By integrating neuromodulation with multiple CR strategies and psychophysiological monitoring in an ecologically valid emotional context, this study seeks to help clarify the neural mechanisms underlying ER and inform the potential clinical utility of tDCS as an adjunct to cognitive interventions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study followed a randomized, single-blind, sham-controlled, within-subjects crossover design, incorporating a between-subjects variable for stimulation site (dlPFC versus vmPFC). Participants were randomly allocated to receive tDCS targeting either the dlPFC or the vmPFC. Each subject underwent two experimental sessions: one involving active tDCS and the other using sham stimulation. The sequence was counterbalanced and separated by a minimum interval of 48 hours to prevent carryover effects [

26].

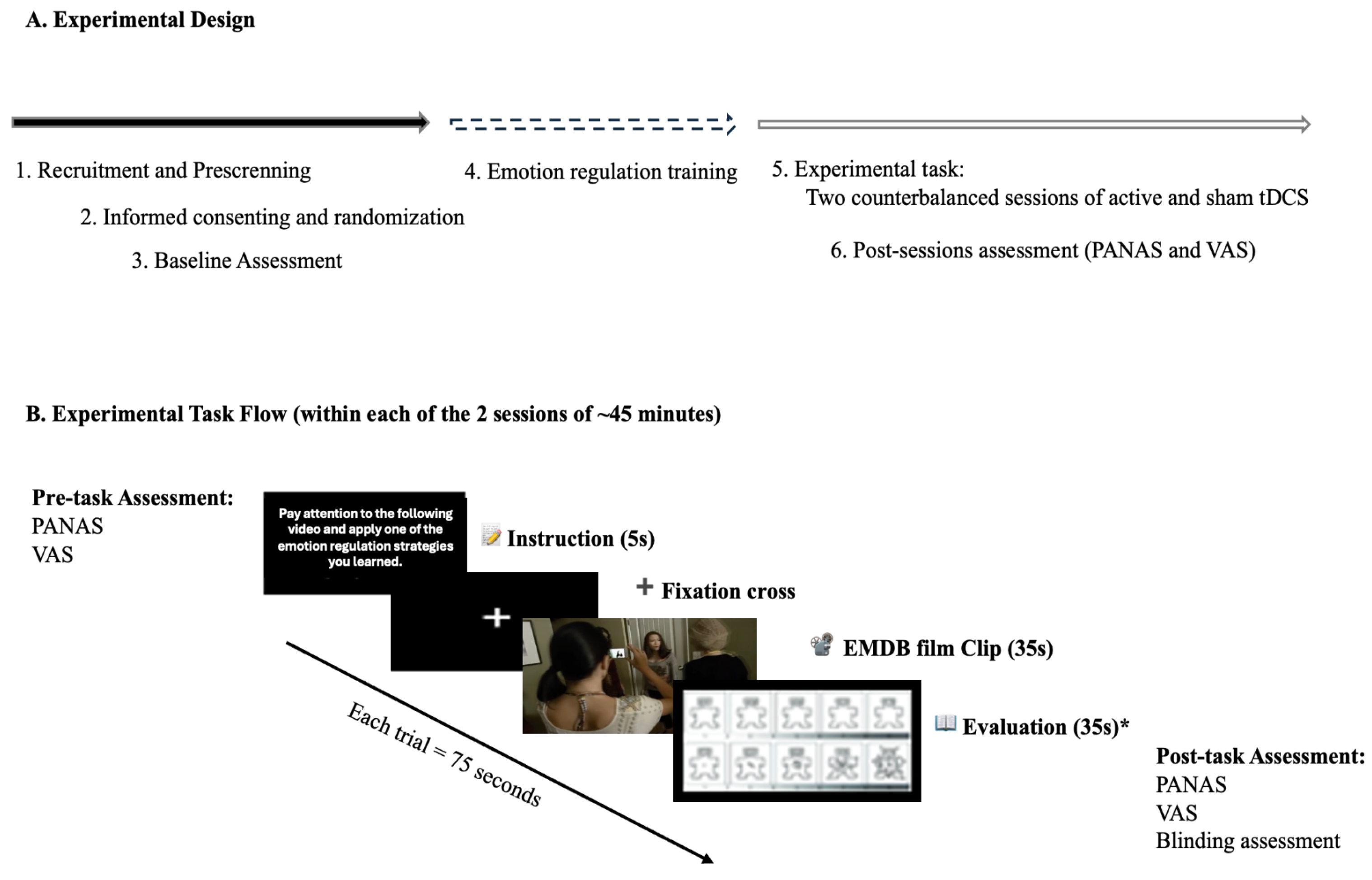

During each session, participants undertook a negative emotion induction task utilizing emotionally evocative film excerpts from the Emotional Movie Database (EMDB), concurrently employing previously acquired cognitive reappraisal techniques. Psychophysiological metrics (heart rate, skin conductance, and respiratory rate) were constantly monitored, while affective states were evaluated before and after stimulation utilizing the PANAS. This strategy facilitated both within-subject comparisons (active versus sham stimulation) and between-group comparisons (dlPFC versus vmPFC stimulation), while accounting for individual variability and permitting a thorough investigation of psychophysiological, affective, and side effect results (

Figure 1).

2.2. Ethical Approval

The study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee for Research in Social and Human Sciences at the University of Minho (Approval n. º CEICSH 060/2022). Data collection was conducted at the BrainLoop Neuroscience Laboratory of Universidade Portucalense - Infante D. Henrique, in Porto, Portugal.

2.3. Participants

Participants were randomly assigned to one of two experimental groups: dlPFC stimulation or vmPFC stimulation. Participants were eligible for inclusion if they were 18 years of age or older, native Portuguese speakers, and permanent residents of Portugal. These criteria ensured that participants had linguistic and cultural homogeneity, as well as the ability to comprehend and follow the study procedures. Exclusion criteria were defined to minimize potential risks associated with transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) and to control confounding variables. Individuals were excluded if they presented any known contraindications for tDCS application, such as the presence of metallic implants in the head (excluding the oral cavity) or implanted medical devices (e.g., pacemakers or neurostimulators). Additional exclusion criteria included a self-reported history of psychiatric or neurological disorders (e.g., epilepsy), illicit psychotropic substances use, and left-handedness, as determined by a score below 70 on the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory. The restriction to right-handed participants was implemented to reduce variability in cortical organization and lateralization effects that could influence stimulation outcomes [

27].

Although 94 individuals were initially recruited, 9 participants were excluded: 7 for missing one session, 1 for completing the same version of the emotional induction task in both sessions, and 1 due to technical malfunction of the stimulator.

2.4. Assessments

2.4.1. Eligibility Measures and Questionnaires

Sociodemographic and Clinical Questionnaire: This self-report questionnaire was developed to gather extensive background information, including participants’ age, sex, gender, nationality, educational level, employment position, and marital status. It also evaluated health-related behaviors like alcohol and tobacco use, other substance intake, and medical history - specifically concentrating on current or previous clinical problems and continuing pharmaceutical treatments. This data was utilized to profile the sample and identify potential confounding factors pertinent to neuromodulation safety and emotional processing.

tDCS Eligibility Assessment: a 16-item dichotomous (yes/no) tDCS eligibility questionnaire was used to screen for contraindications, including prior seizures, unexplained loss of consciousness, neurological conditions, serious head injury, metal implants (excluding dental fillings), implanted medical devices (e.g., pacemakers), pregnancy status, and current medication use. Participants also reported any prior exposure to or adverse reactions from tDCS. Items assessed both personal and family history (e.g., epilepsy), and participants could request additional information about the procedure and its risks. Those presenting any exclusion criteria were not enrolled.

Edinburgh Handedness Inventory (EHI; Espírito-Santo et al., 2017; originally developed by Oldfield, 1971), a 10-item self-report inventory that assesses hand preference in routine activities. Scores vary from -100 (indicating a strong left preference) to +100 (indicating a strong right preference). The Portuguese version exhibits strong internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .88).

2.4.2. Baseline Assessment Instruments

To comprehensively characterize participants’ cognitive-emotional profiles, resilience, and personality traits, three standardized self-report instruments were administered during the initial assessment phase. All instruments used validated Portuguese versions with established psychometric properties.

Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ; Martins et al., 2016; original version by Garnefski et al., 2001) is a 36-item self-report measure designed to assess individual differences in the use of cognitive ER strategies following negative or stressful life events. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). The questionnaire is composed of nine subscales: Self-blame, Rumination, Catastrophizing, Blaming Others, Acceptance, Positive Reappraisal, Refocus on Planning, Positive Refocusing, and Putting into Perspective. The Portuguese version has demonstrated adequate internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from .75 to .91 across subscales.

Emotion Regulation Profile-Revised (ERP-R) is a validated self-report instrument that assesses individual differences in the use and effectiveness of ER strategies across a range of emotionally evocative scenarios. It presents participants with brief hypothetical vignettes and asks them to rate how likely they are to respond using various regulatory strategies. The ERP-R captures both adaptive strategies (e.g., Cognitive Reappraisal, Acceptance, Problem-solving) and maladaptive strategies (e.g., Suppression, Rumination, Avoidance). Developed by Nelis et al. (2011), the ERP-R has demonstrated robust psychometric properties, including good internal consistency, convergent validity with measures of emotional intelligence and well-being, and sensitivity to interindividual differences.

Resilience Scale for Adults (RSA; Pereira et al., 2017; original version by Hjemdal et al., 2011) was used to evaluate individual levels of psychological resilience. This instrument consists of 33 items distributed across six protective factors: Perception of Self, Planned Future, Social Competence, Family Cohesion, Social Resources, and Structured Style. Participants respond using a semantic differential scale, indicating where they fall between two opposing descriptors (e.g., “I feel unimportant – I feel valuable”). Higher scores reflect higher levels of resilience. The Portuguese version of the RSA has shown excellent psychometric properties, including strong internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .90).

Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI; Canavarro, 1999; original version by Derogatis, 1993) is a standardized self-report tool consisting of 53 items, designed to evaluate psychiatric symptom patterns in both clinical and non-clinical groups. It assesses nine principal symptom dimensions - Somatization, Obsessive-compulsive Symptoms, Interpersonal Sensitivity, Depression, Anxiety, Hostility, Phobic Anxiety, Paranoid Ideation, and Psychoticism. Participants evaluate the degree of distress caused by each symptom over the preceding seven days with a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (“not at all”) to 4 (“extremely”). The BSI has undergone extensive validation and exhibits strong psychometric features, including adequate internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from .71 to .85 across subscales.

2.4.3. Experimental Task Instruments

A set of self-report instruments was administered during the experimental sessions to assess participants’ affective states, evaluate the tolerability of the transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), and verify the integrity of the double-blind procedure.

Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Galinha and Pais-Ribeiro, 2012; original version by Watson et al., 1988) was used to measure participants’ affective states before and after each experimental session. The instrument consists of 20 adjectives representing emotional states, divided equally into two subscales: Positive Affect (PA) and Negative Affect (NA). Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“very slightly or not at all”) to 5 (“extremely”), based on how the participant feels at the present moment. Higher scores indicate greater levels of the respective affective dimensions. The Portuguese version of PANAS has demonstrated excellent internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of .86 for PA and .89 for NA.

Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) for tDCS Side Effects: to monitor potential adverse effects of tDCS, VAS was administered both before and immediately after each stimulation session. This self-report instrument combines visual and numeric elements, consisting of 10 items rated on a Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (“not at all”) to 10 (“extremely”). It assesses a range of symptoms commonly associated with non-invasive brain stimulation, including fatigue, anxiety, sadness, agitation, drowsiness, itching, headache, other types of pain, tingling sensations, and metallic taste. This measure helped ensure participant safety and tolerability of the stimulation protocol.

tDCS Blinding Questionnaire: to assess the effectiveness of the double-blind procedure, participants completed a blinding questionnaire at the end of each session. They were asked to indicate their best guess regarding the type of stimulation received (active, sham, or “don’t know”) and to rate their confidence in that judgment on a 5-point scale (“not at all” to “extremely confident”). This measure was used to evaluate the success of participant blinding and to rule out expectancy effects that could confound the interpretation of results.

2.5. Cognitive Reappraisal Training Session

Prior to participating in the experimental task, all subjects underwent a structured Cognitive Reappraisal (CR) training session aimed at acquainting them with the emotion management mechanisms employed in the study. The workshop presented three CR techniques - positive reappraisal, fictional reappraisal, and distancing - each based on modern emotional control theory. Participants were provided with theoretical explanations, sequential instructions, and guided practice exercises to ensure understanding and proper implementation of each method.

To enhance experiential learning and replicate the conditions of the primary task, participants observed a series of negative valance film clips (excluded from the experimental trials) and were directed to implement the CR strategies accordingly. Following the practice of each technique, participants assessed their comprehension and preparedness to advance. Only individuals who expressed confidence in independently implementing the techniques progressed to the experimental phase.

Additional information concerning the structure, instructional resources, and content of the training session is available in the

Supplementary Materials (SM1 - Emotion Regulation Training Guidelines).

2.6. Emotional Induction Task

The emotional induction task was designed to elicit negative emotional responses in a controlled laboratory setting using film clipes. It was developed and implemented using e-Prime software (version 3) and consisted of a series of short film clips selected from the Emotional Movie Database (EMDB; [

38]; Carvalho et al., submitted). These clips had been previously validated for emotional valence and arousal in the Portuguese population.

Each experimental session included 21 clips: 15 with negative emotional content (e.g., scenes evoking fear, sadness, or distress) and 6 with neutral content. The total duration of the task was approximately 26 minutes, including a training phase and the main task. Prior to the main task, participants completed a brief training phase using three negative clips. During this phase, they were instructed to apply one of three pre-trained cognitive reappraisal strategies - positive reappraisal, fictional reappraisal, or decentering - to become familiar with the task structure and regulatory techniques.

For each trial, participants first received strategy instructions on screen for 5 seconds. This was followed by the presentation of a film clip lasting 30 seconds, after which they had an additional 35 seconds to evaluate their emotional experience using the Self-Assessment Manikin (SAM), a non-verbal pictorial scale measuring valence (pleasant–unpleasant) and arousal (calm–excited). The instruction preceding each clip varied randomly between passive observation and active application of a CR strategy. All clips were presented without sound to avoid auditory influence, and the sequence of clips was randomized across participants to reduce order effects.

To minimize familiarity or habituation, two versions of the task (Version A and Version B) were developed. These versions followed the same structure and distribution of emotional content but featured different film clips. Only the training phase contained the same stimuli across both versions. The structure of the task and the timing of each component are illustrated in

Figure 2. Please refer to

Table S1 in the supplementary material to assess the descriptions of the film clips used from the EMDB.

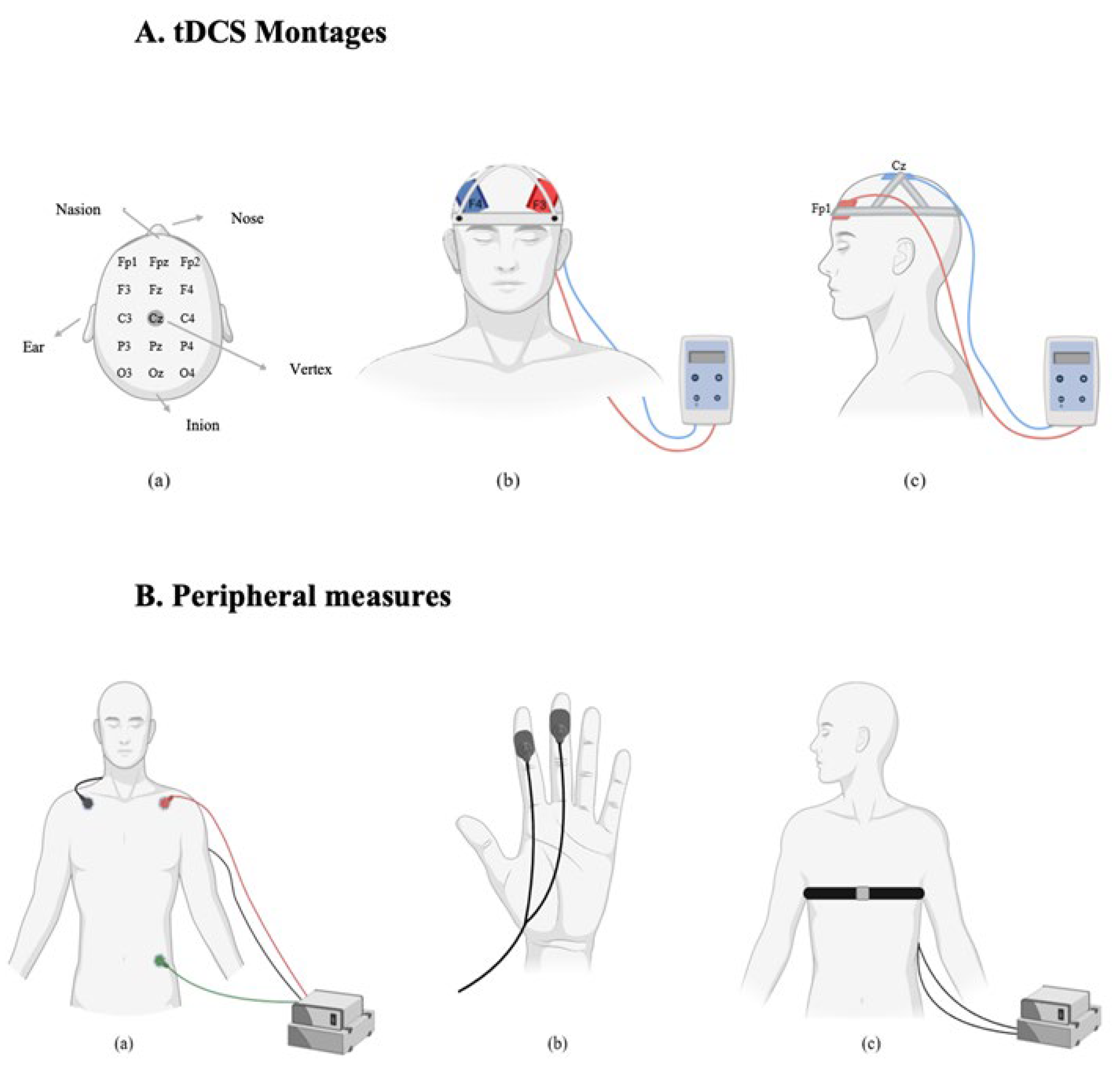

2.7. Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation

Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) was applied using the Edith DC Stimulator Plus (NeuroConn, Germany). Electrode placements followed the 10-20 international EEG system [

39]. Two sponge electrodes, each with an area of 35 cm

2 (7 × 5 cm), were soaked in a 0.9% sodium chloride (NaCl) solution to improve conductivity and reduce skin resistance. Participants were randomly assigned to one of two stimulation montages. In the dlPFC group, a bifrontal montage was used. The anode was placed over the left dlPFC (F3) and the cathode over the right dlPFC (F4). In the vmPFC group, the anode was placed over the left vmPFC (Fp1) and the cathode over the vertex (Cz). In the active stimulation condition, a current of 2 mA was applied for 20 minutes. A 30-second ramp-up and 30-second ramp-down period was used to minimize discomfort. In the sham condition, the same electrode placements were used, but stimulation was applied for only 90 seconds (30 seconds ramp-up, 30 seconds at 2 mA, and 30 seconds ramp-down), after which the device was turned off automatically. This protocol ensured that participants experienced the initial sensations of stimulation, maintaining the integrity of the blinding procedure. Impedance was continuously monitored during each session to ensure it remained below 5 kΩ. Stimulation was only initiated when impedance levels were within this safe and acceptable range.

2.8. Peripheral Measures

Physiological data were recorded and processed using LabChart software (version 8). The processing steps were planned to minimize noise and artifacts and to isolate relevant signal components for subsequent analysis. These procedures are consistent with previous studies investigating the effects of tDCS on autonomic and emotional responses [

23].

Heart rate (HR) data were cleaned to remove artifacts usually associated with movement or electrode noise. This was accomplished using the arithmetic option in LabChart, applying the function resample(Chi/4). This process reduces signal variability and improves the data smoothness. In the skin conductance data, the tonic component was isolated from the phasic component. To perform this, a new channel was created, and then, to clean the data, the following function was applied: Smoothsec(Differentiate(RClowpass(Ch5;0,205);3);1,3) in the arithmetic option. Respiratory rate (RR) data were recorded without additional processing, as the raw signal quality was deemed sufficient for the analysis.

Following signal cleaning, all physiological data were segmented according to the stimuli: neutral and negative (medium and high arousal) films. Data was extracted at fixed timepoints of 0-5, 5-10, 10-15, 15-20, 20-25 and 25-30 seconds for each film category. These timepoints were selected to capture temporal dynamics of physiological activity during emotional induction, as usually implemented in other studies [

40].

2.9. Statistical Analyses

All analyses were performed in R Studio (version 4.5.0), with the significance threshold set at p < .05. To confirm that the two main stimulation groups (dlPFC and vmPFC) were comparable on sociodemographic and clinical variables, chi-square tests were used for categorical data and independent samples t-tests for continuous data. Within each stimulation group, participants were also categorized according to the presence or absence of emotion regulation (ER) difficulties, based on validated cut-off scores from the rumination subscale of the CERQ (≥14 for females; ≥12 for males).

Physiological responses (heart rate [HR], skin conductance [SC], and respiratory rate [RR]) were analyzed using a hierarchical approach. Each stimulation group (dlPFC or vmPFC) was subdivided into four experimental conditions: (1) active tDCS with cognitive reappraisal (CR); (2) active tDCS without CR; (3) sham tDCS with CR; and (4) sham tDCS without CR.

To test for regional and condition-specific effects, two-way mixed-design ANOVAs were conducted with stimulation region (dlPFC vs. vmPFC) as the between-subjects factor and condition as the within-subjects factor. For time-series analyses, the emotional film clips were segmented into six consecutive 5-second intervals (0–5 s, 5–10 s, 10–15 s, 15–20 s, 20–25 s, and 25–30 s) to capture the temporal dynamics of physiological responses. This binning approach follows prior work on the temporal unfolding of autonomic reactions to affective stimuli and helps isolate early versus late-phase effects.

To account for baseline autonomic variability, difference scores were calculated by subtracting each participant’s physiological response to neutral clips from their response to negative clips. These difference scores were analyzed with three-way mixed-design ANOVAs, including stimulation site (between-subjects), condition, and time interval (within-subjects). Separate within-group repeated-measures ANOVAs further explored condition and time effects for dlPFC and vmPFC groups individually.

Effect sizes were calculated using partial eta squared (η2ₚ). Where applicable, post-hoc pairwise comparisons were corrected for multiple testing using Tukey’s HSD; all significant findings are reported with indication of whether they survived correction. Non-significant trends (p values between .05 and .10) are noted but interpreted cautiously as exploratory.

For subjective measures (PANAS) and side effects (VAS), pre–post changes within each session (active vs. sham) were examined using paired-samples t-tests. Independent samples t-tests compared active and sham conditions at each time point. Missing data were minimal (<5%) and handled with pairwise deletion.

If no formal power analysis was conducted, this is acknowledged as a limitation, as the moderate sample size may limit sensitivity to detect small effects in autonomic measures.

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic and Clinical Data

Eighty-five volunteers participated (

M_age = 27.7 years,

SD = 10.8; 81.2% female), divided into dlPFC (

n = 46) and vmPFC (

n = 39) groups. The groups did not differ significantly in age, sex, nationality, marital status, education, or occupation, confirming comparable baseline characteristics (

Table 1). Approximately 42% reported difficulties in emotion regulation (ER).

Participants with ER difficulties in both groups showed significantly higher scores on maladaptive strategies (e.g., self-blame, rumination, catastrophizing; all p < .01) than those without difficulties. Notably, they also reported greater use of some adaptive strategies (e.g., acceptance, positive refocusing; p < .05).

Regarding mental health, participants with ER difficulties had higher overall symptom scores (dlPFC: p < .05) and higher scores on specific subscales (interpersonal sensitivity, anxiety, hostility, paranoid ideation; all p < .05). The vmPFC group showed higher psychoticism (p < .05). Lower family cohesion was also observed among vmPFC participants with ER difficulties (p < .05).

3.2. Physiological Responses (Full clip)

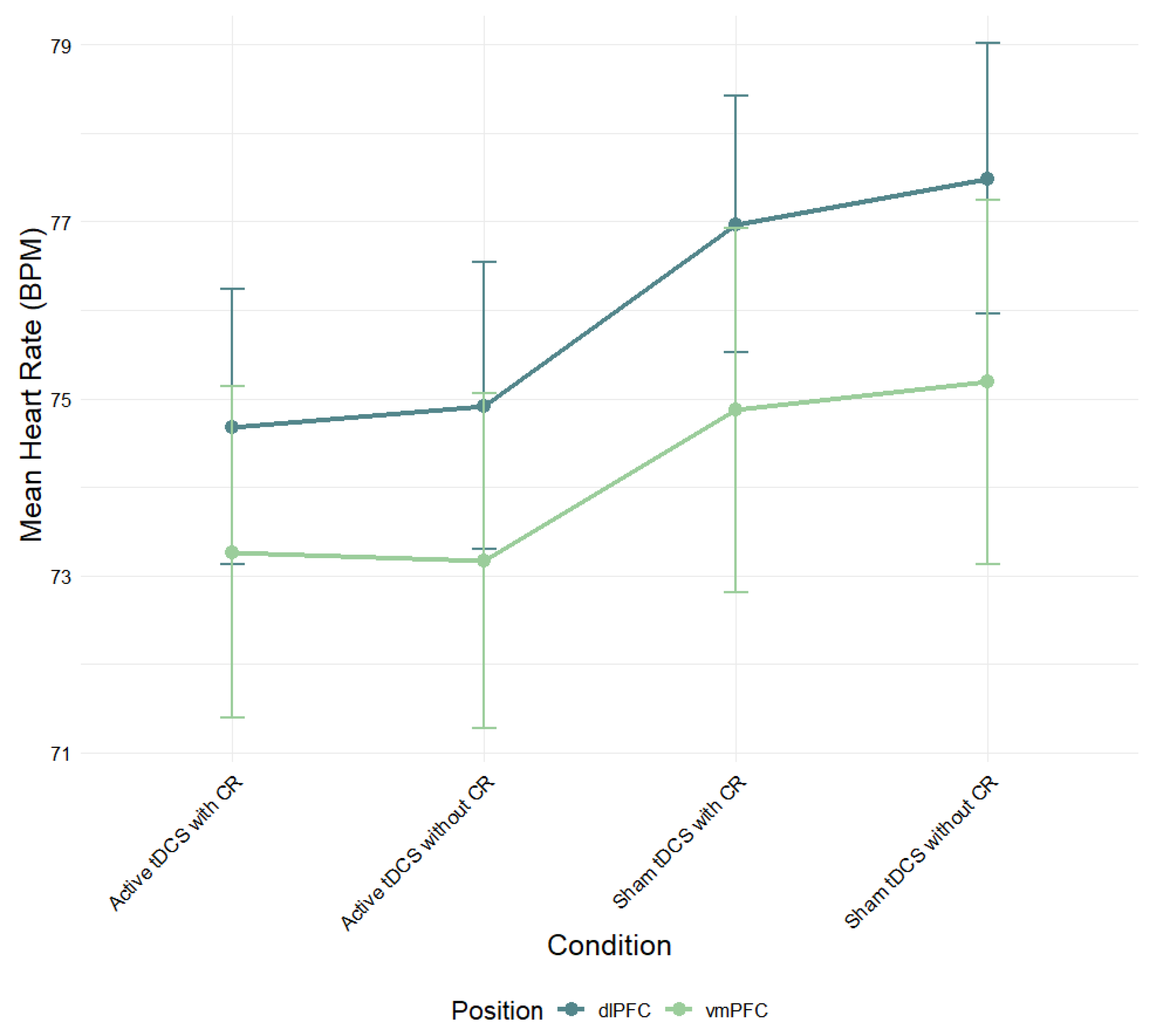

3.2.1. Heart Rate

A mixed-design ANOVA was conducted to examine the effects of electrode position (dlPFC vs. vmPFC) and experimental condition (active tDCS with CR, active tDCS without CR, sham tDCS with CR, sham tDCS without CR) on mean heart rate (

Figure 3). Although the dlPFC group exhibited consistently higher heart rate scores across all conditions compared to the vmPFC group, this difference did not reach statistical significance,

F(1, 83) = .72,

p > .05,

η2ₚ = .01. This suggests that stimulation region did not significantly affect overall heart rate.

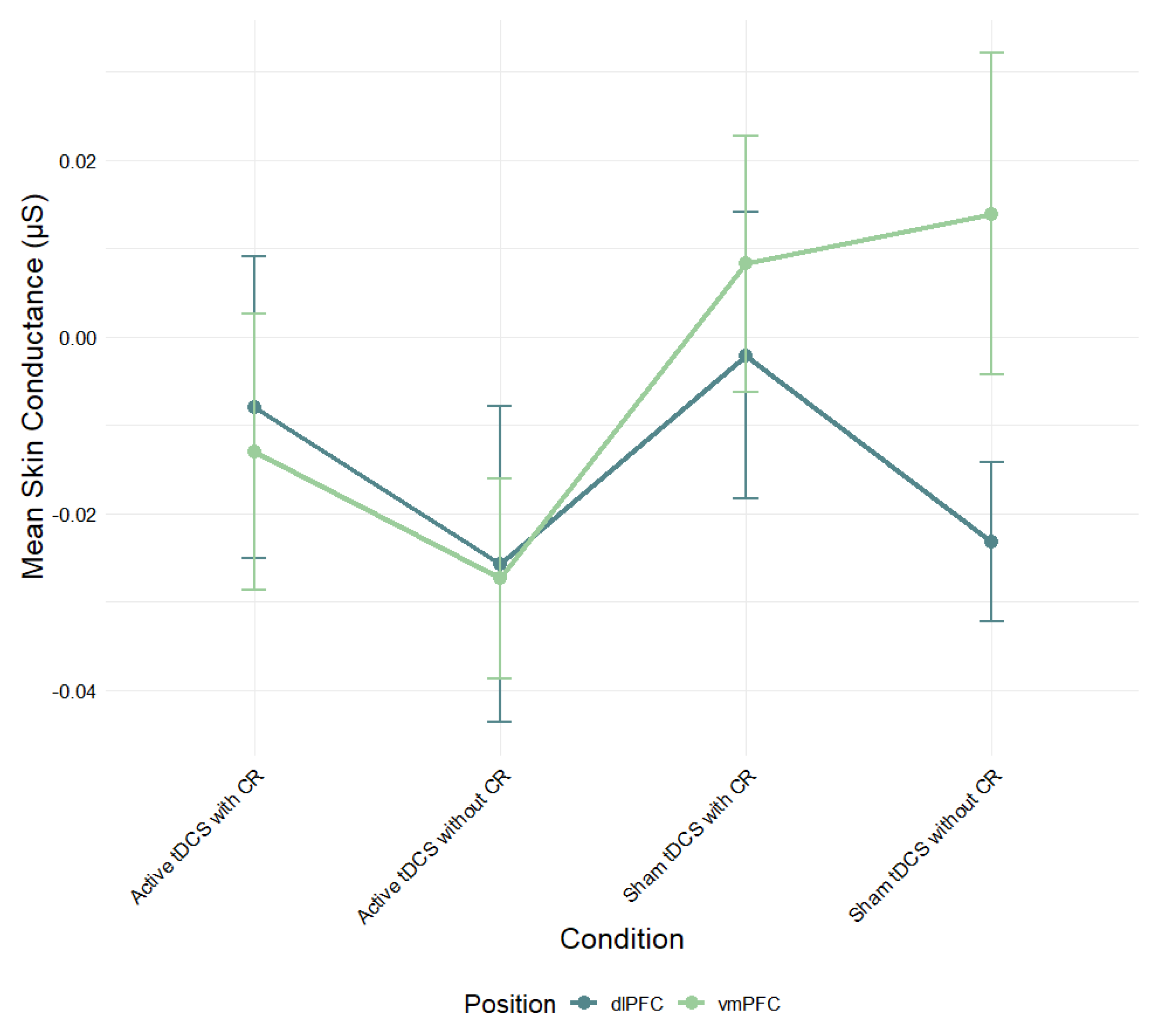

3.2.2. Skin Conductance

A mixed-design ANOVA was also performed to assess the effect of electrode position and condition on mean skin conductance levels (

Figure 4). While the vmPFC group showed higher skin conductance scores in the sham conditions compared to the dlPFC group, there was no significant main effect of stimulation region,

F(1, 73) = .44,

p > .05,

η2ₚ = .01.

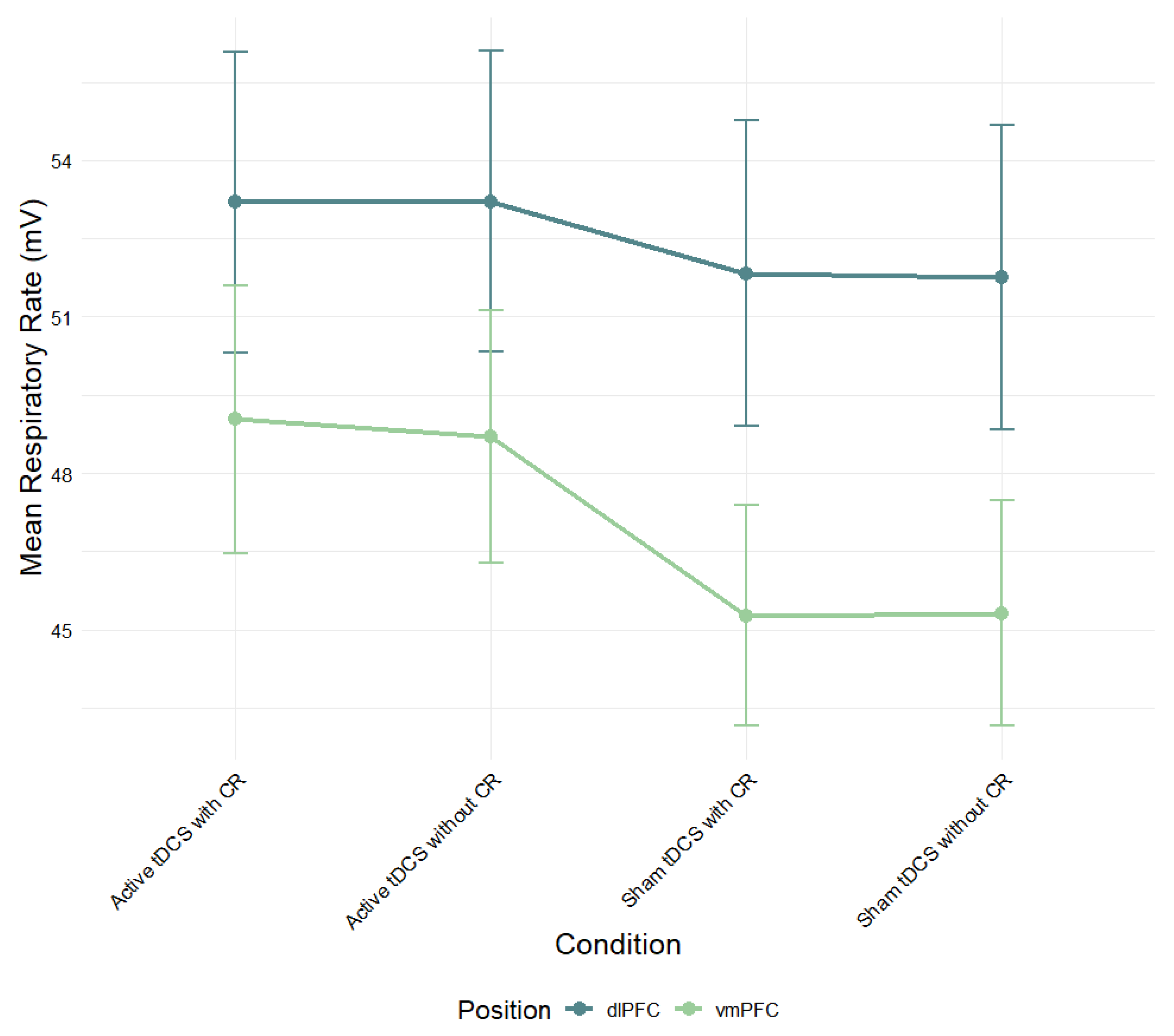

3.2.3. Respiratory Rate

A mixed-design ANOVA was conducted to evaluate the effects of electrode position and experimental condition on mean respiratory rate (

Figure 5). Although the dlPFC group showed slightly higher respiratory rates across conditions than the vmPFC group, this difference was not statistically significant,

F(1, 83) = 3.23,

p > .05,

η2ₚ = .04.

3.3. Differences in Physiological Activation Across Time (5 Second-Epochs)

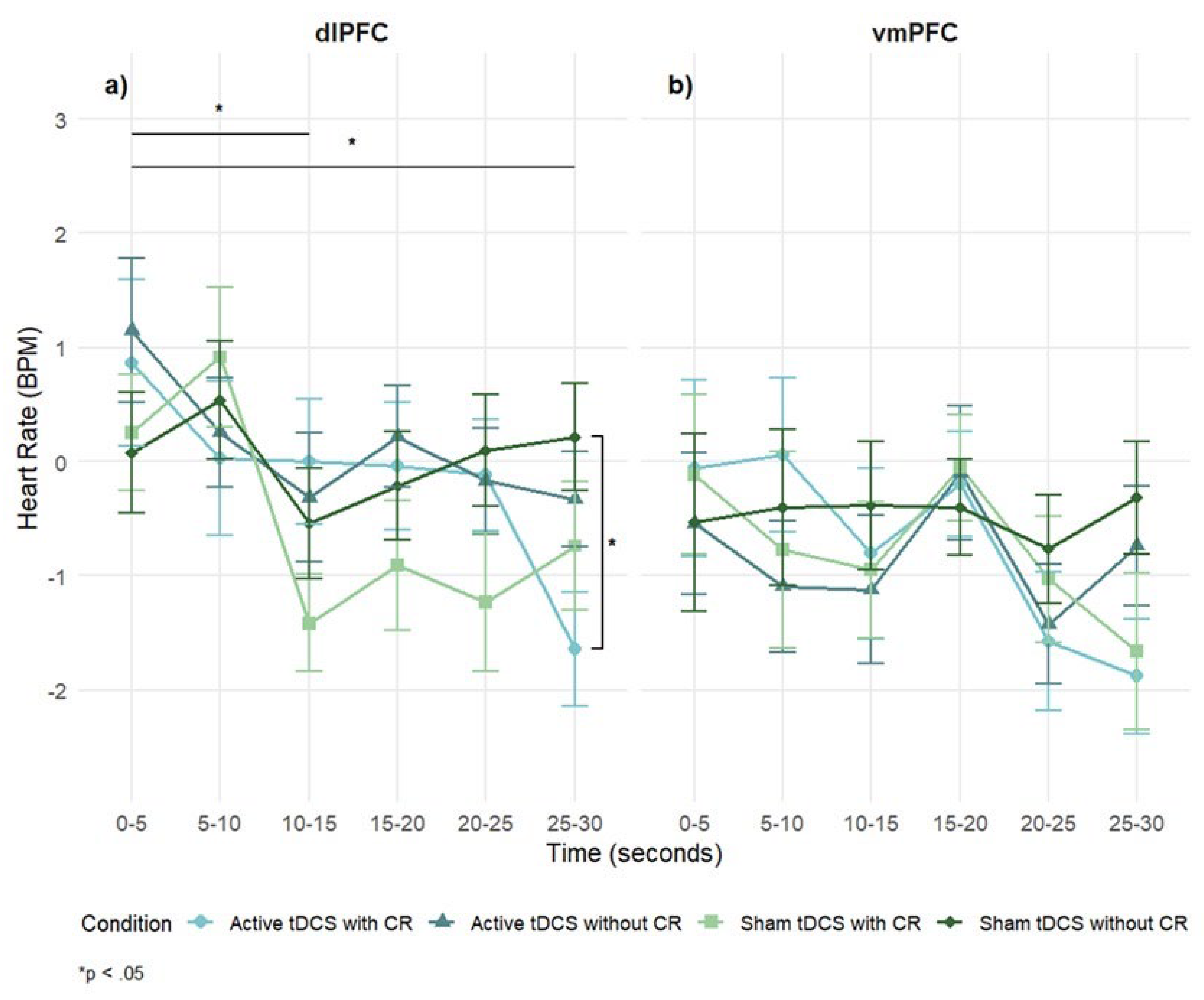

3.3.1. Heart Rate

Participants demonstrated significant overall heart rate (HR) response to negative emotional stimuli, indicating that the film clips effectively evoked measurable autonomic responses (intercept: M = –.41, SE = 0.18, p < .05, 95% CI [–.78, –.07]).

A 2 (stimulation region: dlPFC, vmPFC) × 4 (condition: Active tDCS with CR, Active tDCS without CR, Sham tDCS with CR, Sham tDCS without CR) × 6 (time: 0-5, 5-10, 10-15, 15-20, 20-25, 25-30 seconds) mixed-design ANOVA on HR difference scores (negative – neutral) revealed a significant main effect of time,

F(5, 42) = 3.91,

p = .002,

η2ₚ = .05. The main effects of stimulation region,

F(1, 83) = 2.66,

p = .11,

η2ₚ = .03, and condition,

F(3, 25) = .71,

p = .55, η

2ₚ = .01, were not significant. All interactions were non-significant: Region × Condition,

F(3, 25) = .51,

p = .67,

η2ₚ = .01; Region × Time,

F(5, 42) = .91,

p = .47,

η2ₚ = .01; Condition × Time,

F(15, 68) = 1.84,

p = .066,

η2ₚ = .04; Region × Condition × Time,

F(15, 68) = .85,

p = .62,

η2ₚ = .01. Although non-significant, dlPFC stimulation produced larger HR changes than vmPFC over time (

Figure 6).

In the dlPFC group, a significant main effect of time was observed,

F(5, 23) = 2.87,

p = .02,

η2ₚ = .06, indicating HR changes across the stimulus exposure, but the main effect of condition was not significant,

F(3, 14) = 1.06,

p = .37,

η2ₚ = .02. However, a significant condition × time interaction emerged,

F(15, 68) = 1.84,

p = .03,

η2ₚ = .04, suggesting that the experimental conditions differentially impacted HR responses. Post-hoc tests revealed that HR decreased significantly at 10-15s (

p = .03) and 25-30s (

p = .02) when compared to 5s . At the 25-30-second point, the combination of active tDCS and CR decreased significantly the HR, when compared to sham tDCS without CR (

p = .04) (

Figure 6a).

In the vmPFC group, the main effects of time,

F(5, 19) = 2.02,

p = .08,

η2ₚ = .05; condition,

F(3, 114) = .26,

p = .86,

η2ₚ = .01; and the condition × time interaction,

F(15, 57) = .79,

p = .69,

η2ₚ = .02, were not significant. However, descriptively, lower HR was observed for the active tDCS with CR and sham tDCS with CR conditions compared to others (

Figure 6b).

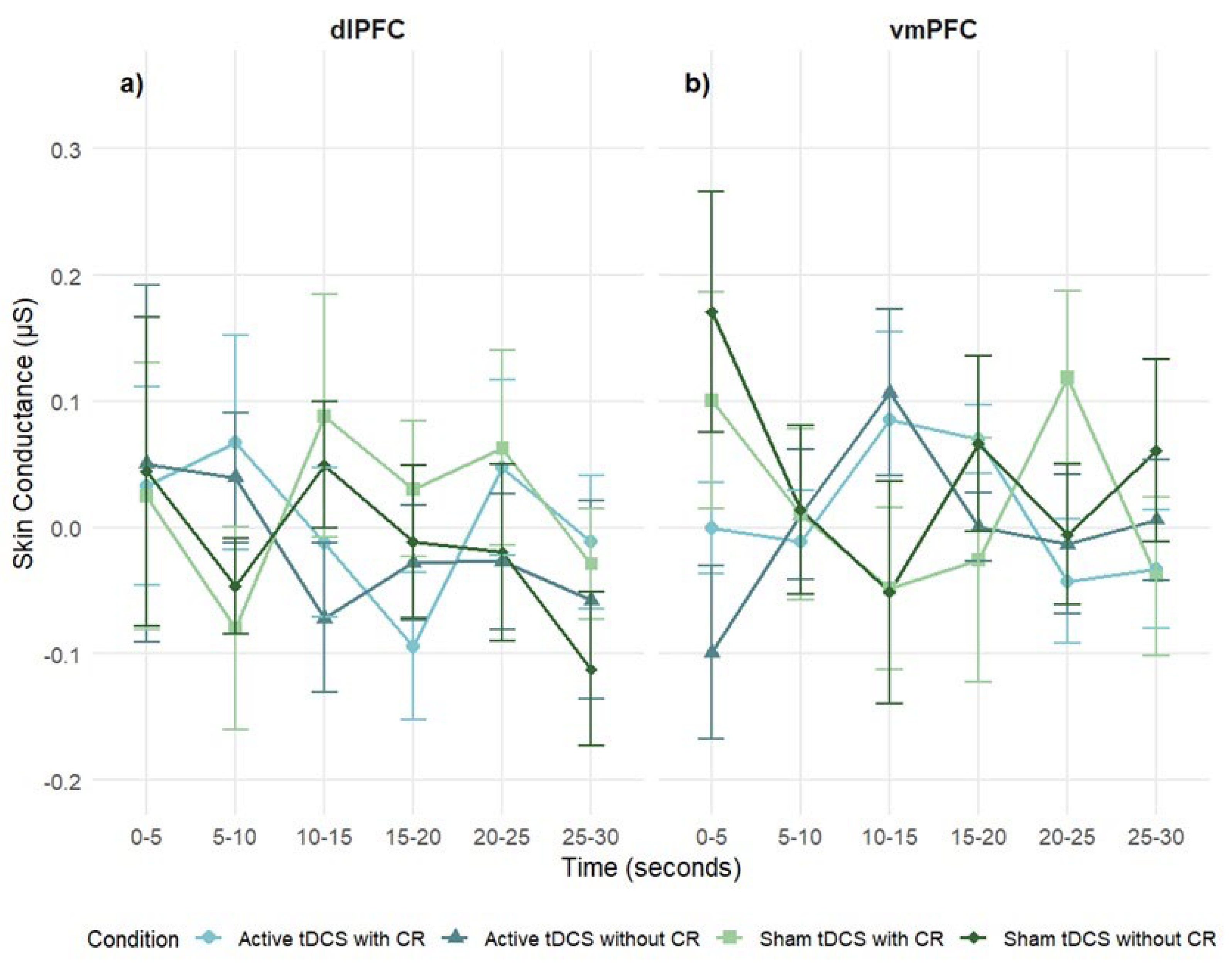

3.3.2. Skin Conductance

Participants did not show significant overall skin conductance (SC) activation in response to negative stimuli (intercept: M = .01, SE = .01, p = .43, 95% CI [–.01, .03]), suggesting minimal sympathetic arousal at the group level.

A 2 stimulation regions × 4 condition × 6 times mixed-design ANOVA on SC difference scores revealed no significant main effect of stimulation region,

F(1, 68) = 1.06,

p = .31,

η2ₚ = .02. No significant main effects of time or condition were observed, and all interaction terms were non-significant: Region × Condition, Region × Time, Condition × Time, and Region × Condition × Time (

p > .05;

Figure 7). These results suggest that SC reactivity was not modulated by stimulation site, condition, or time.

In the dlPFC group, no significant effects were found for time,

F(5, 21) = .38,

p = .86,

η2ₚ = .01; condition,

F(3, 12) = .45,

p = .72,

η2ₚ = .01; or condition × time interaction,

F(15, 61) = .51,

p = .93,

η2ₚ = .01, indicating that dlPFC stimulation did not modulate SC responses (

Figure 7a).

Similarly, the vmPFC group showed no significant main effects of time,

F(5, 14) = .32,

p = .90,

η2ₚ = .01; condition,

F(3, 81) = 1.25,

p = .30,

η2ₚ = .04; or condition × time interaction,

F(15, 41) = 1.2,

p = .27,

η2ₚ = .04 (

Figure 7b).

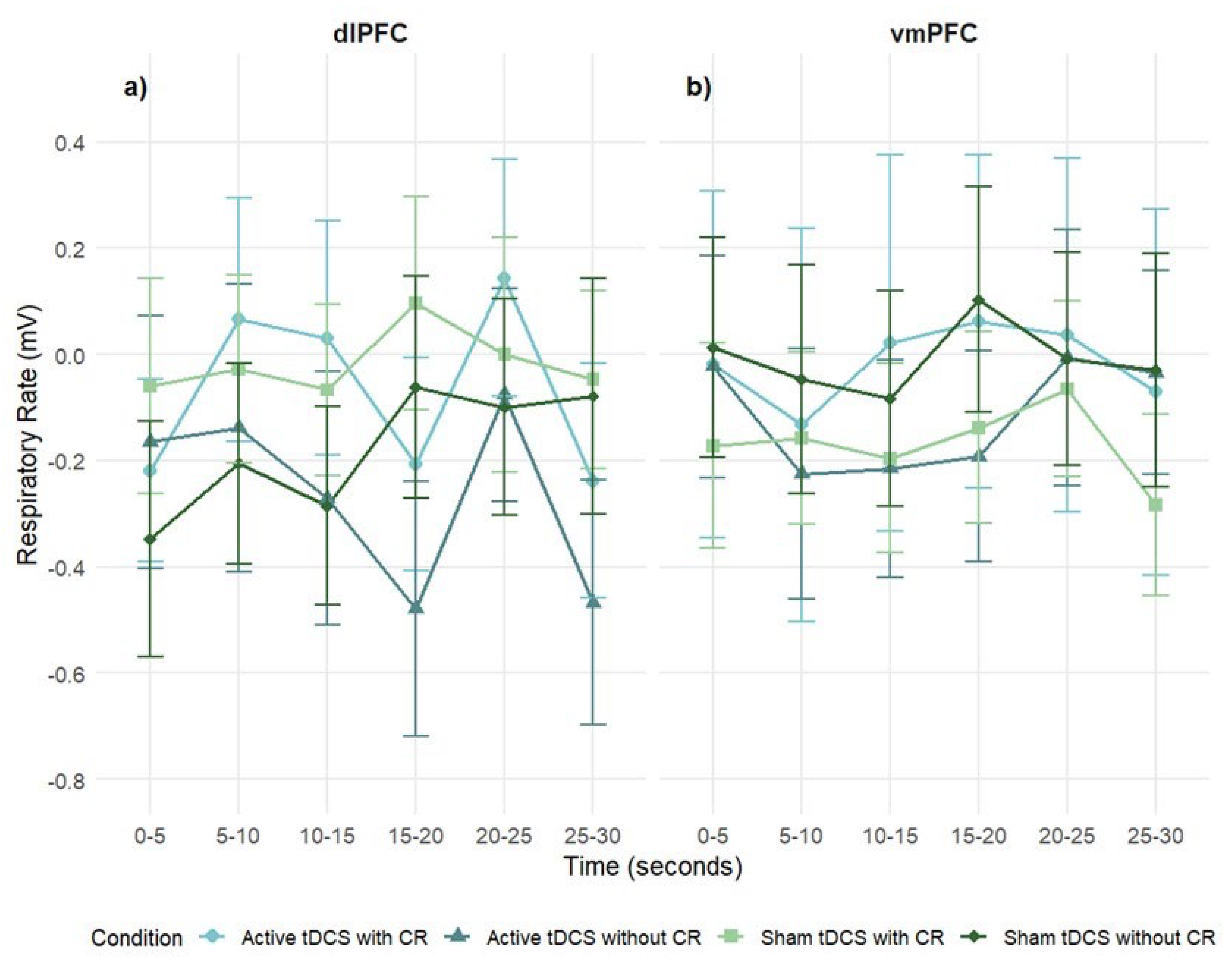

3.3.3. Respiratory Rate

Global Respiratory Rate Response

Participants did not show significant overall respiratory rate (RR) activation to negative stimuli (intercept: M = –.11, SE = .10, p = .28, 95% CI [–.29, .08]), indicating minimal group-level RR changes.

A 2 stimulation regions × 4 condition × 6 times mixed-design ANOVA on SC difference scores revealed no significant main effect of stimulation region, revealed no significant main effects of stimulation region,

F(1, 83) = .08,

p = .77,

η2ₚ = .001; time,

F(5, 42) = 1.16,

p = .33,

η2ₚ = .01; or condition,

F(3, 25) = .25,

p = .86,

η2ₚ = .003. All interactions were non-significant: region × condition, region × time, condition × time, region × condition × time (

p < .05;

Figure 8).

In the dlPFC group, no significant effects were found for time,

F(5, 23) = 1.33,

p = .25,

η2ₚ = .03, or condition,

F(3, 14) = .50,

p = .68,

η2ₚ = .01. The condition × time interaction approached significance,

F(15, 68) = 1.65,

p = .056,

η2ₚ = .04, with sham conditions showing slightly higher RR at the final interval (

Figure 8a).

In the vmPFC group, the main effects of time,

F(5, 19) = 0.60,

p = .70,

η2ₚ = .02; condition,

F(3, 11) = .16,

p = .92,

η2ₚ = .004; and condition × time,

F(15, 57) = .51,

p = .94,

η2ₚ = .01, were not significant (

Figure 8b).

3.4. Differences in Psychological Activation

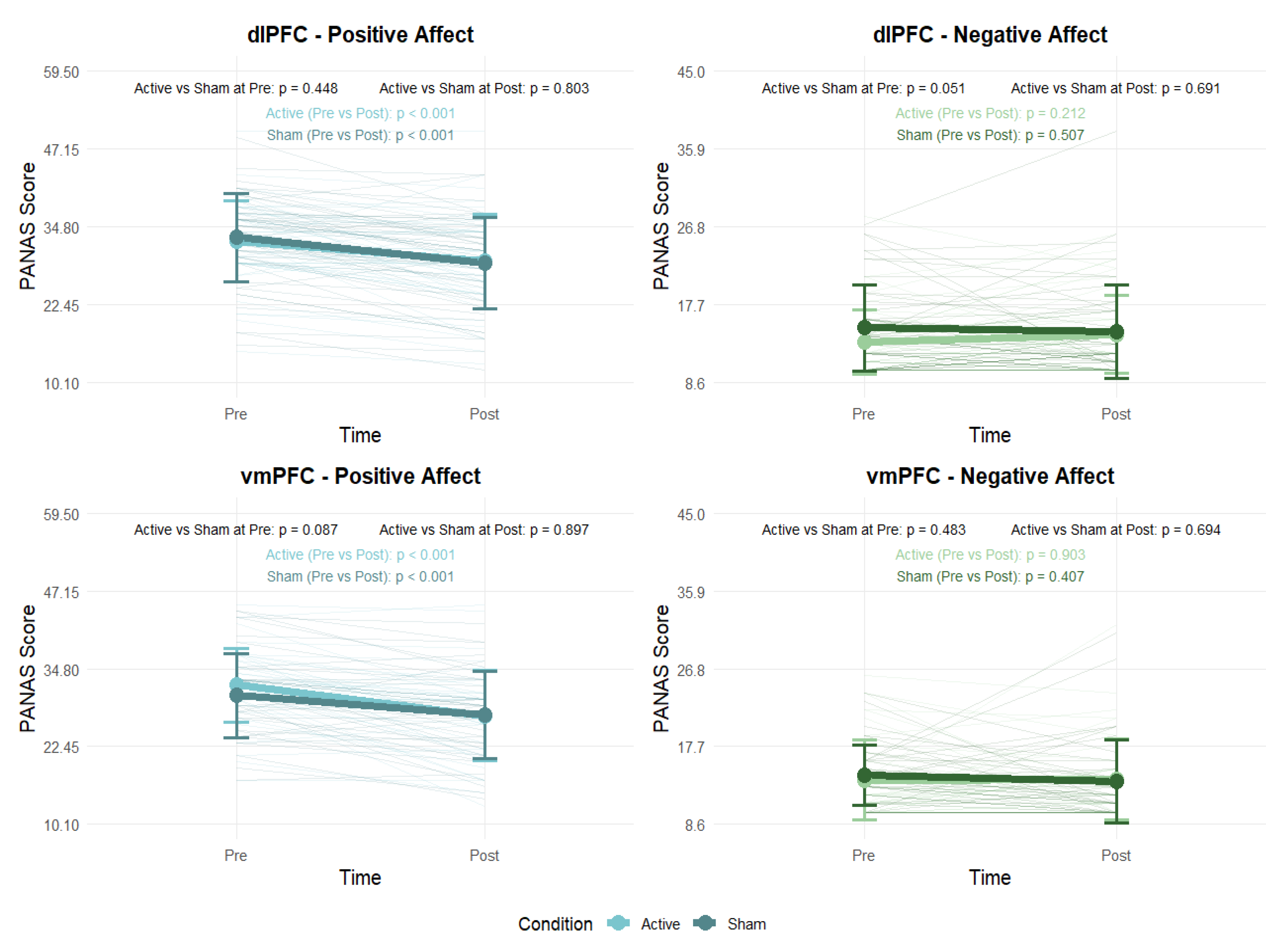

3.4.1. Positive and Negative Affect

Paired-samples t-tests were conducted to examine changes in positive and negative affect (PANAS) before and after the experimental sessions. Additionally, independent-samples t-tests compared active and sham conditions at both pre- and post-session timepoints (

Figure 9). In both the dlPFC and vmPFC groups, participants showed a significant decrease in positive affect from pre- to post-session in both the active (p < .001) and sham (p < .001) conditions. By contrast, there were no significant changes in negative affect in either the active (p > .05) or sham (p > .05) conditions. Comparisons between active and sham conditions at each timepoint revealed no significant differences (p > .05) in either stimulation area.

3.4.2. tDCS Side Effects

Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) assessments revealed significant differences between pre- and post-session ratings for tDCS side effects. In the dlPFC group, participants receiving active tDCS reported significantly reduced tiredness (

p < .05) and increased itching sensation (

p < .05) following stimulation. Participants in the sham condition reported significantly lower ‘other pain’ ratings post-session (

p < .05) (see

Table S5).

Similarly, in the vmPFC group, active tDCS was associated with significantly higher post-session itching sensation scores (

p < .05). In contrast, the sham condition showed a significant increase in reported anxiety (

p < .01) compared to pre-session scores (see

Table S6).

3.4.3. Blinding Effectiveness

The blinding questionnaire indicated variability in participants’ awareness of their assigned stimulation condition. In the dlPFC group, approximately 75% of participants correctly identified whether they received active or sham stimulation. In comparison, only about 40% of participants in the vmPFC group correctly identified their condition, suggesting that blinding was more effective for vmPFC stimulation.

4. Discussion

This study provides evidence that tDCS targeting the dlPFC enhances ER, particularly when paired with CR. This effect was indexed by significant reductions in HR during the final phase of exposure to emotionally evocative film clips. In contrast, stimulation of the vmPFC produced more variable and statistically nonsignificant effects, which is consistent with its role in affective valuation rather than in top-down regulation. However, despite these trends, the overall analysis did not reveal significant differences between dlPFC and vmPFC stimulation. Although interest in non-invasive brain stimulation for ER is growing, few studies have examined the real-time effects of tDCS in ecologically valid contexts. By combining targeted prefrontal stimulation with naturalistic emotional stimuli and continuous physiological monitoring, this study provides novel evidence that tDCS can modulate autonomic arousal during intentional emotion regulation. These findings offer new insights into the neural and physiological mechanisms of top-down emotion control, with implications for both basic research and clinical neuromodulation strategies.

Our findings align with prior research highlighting the role of the dlPFC in sustaining regulatory goals and inhibiting emotional reactivity [

10,

22]. Specifically, our results indicate that active anodal tDCS over the dlPFC, when paired with CR, resulted in significantly greater decreases in HR compared to both sham stimulation and active tDCS without CR. This finding corroborates the concept that increased excitability of the dlPFC promotes the utilization and execution of top-down regulation techniques, hence enhancing their ability to diminish physiological indicators of emotional arousal [

41]. The synergistic interaction between neuromodulation and CR indicates that tDCS may reduce the cognitive burden linked to demanding emotional regulation, potentially by enhancing prefrontal activation related to sustaining regulatory objectives, redirecting attentional focus, or suppressing automatic emotional reactions. The dlPFC has been associated with these processes due to its involvement in working memory, goal maintenance, and the suppression of limbic activity through downstream pathways [

13], and our results correspond with this molecular paradigm.

Notably, we showed that active dlPFC stimulation without explicit CR instruction significantly reduced HR, indicating that tDCS alone may produce a broad calming impact on autonomic reactivity. The results may indicate an unmonitored modulation of implicit emotion regulation systems, in which heightened prefrontal excitability amplifies spontaneous regulatory mechanisms absent intentional strategy application. Alternatively, participants may have employed informal or spontaneous regulating techniques during emotional exposure, which were enhanced by the neural priming effects of dlPFC activation. These findings offer converging evidence that dlPFC-targeted tDCS improves both conscious and possibly implicit emotion regulation, as indicated by heart rate, which serves as a sensitive and temporally consistent measure of this modulatory effect.

Emotionally evocative stimuli usually induce a dual-phase autonomic reaction, characterized by an initial deceleration of heart rate indicative of orienting or freezing, succeeded by a subsequent rise as the stimulus is assessed and mobilization ensues [

41]. In the current study, it is noteworthy that the application of tDCS over the dlPFC in combination with CR seemed to interfere with or diminish the typical autonomic response pattern. A prolonged decrease in HR that persisted in the final stages of exposure to the stimuli. This pattern suggests that neuromodulation targeting the dlPFC may counteract the natural shift toward sympathetic activation, possibly facilitating sustained top-down regulation and increasing parasympathetic tone [

23,

42,

43], while simultaneously altering threat appraisal and reducing amygdala activity [

44].

In the vmPFC group, reductions in HR were noted after active tDCS, regardless of the presence or absence of explicit CR. Nonetheless, these effects exhibited less consistency across timepoints and were more susceptible to statistical correction for multiple comparisons, suggesting that vmPFC stimulation may have a milder or more temporally diffuse impact on autonomic control in comparison to dlPFC stimulation. Although both stimulation sites resulted in decreased heart rate, the effects of dlPFC stimulation were more persistent and pronounced, underscoring its pivotal role in executive control and goal-oriented regulation. The effects of the vmPFC were temporally variable and less dependable, possibly indicating its integrative rather than directing role in emotion processing. This result corresponds with the specific functional role of the vmPFC in emotion regulation, which is believed to be more intricately linked to affective valuation, self-referential processing, and the integration of emotional context, rather than the intentional cognitive control processes generally facilitated by the dlPFC [

42,

43].

The vmPFC is both physically and functionally linked to limbic and subcortical areas, including the amygdala, hypothalamus, and periaqueductal gray, which are essential for autonomic arousal and threat assessment [

44]. The modulation of this network with tDCS may affect emotion processing via implicit or automatic pathways; hence, it impacts arousal control even without the application of conscious strategies. Recent neuroimaging and stimulation research indicates that vmPFC activity facilitates emotion regulation by influencing emotional salience and attenuating amygdala reactivity, frequently via mechanisms that are not readily accessible to introspection or voluntary control [

11]. Contrary to expectations, SC and RR exhibited no consistent modulation across circumstances. The findings may indicate modality-specific sensitivities, with heart rate acting as a more temporally responsive and discriminative measure during film-based emotional exposure. Moreover, individual variability and brief clip durations may have attenuated small SC/RR effects. Although previous research has indicated a correlation between effective cognitive reappraisal and decreased SCR [e.g., 17] these effects were not repeated in this study. Multiple factors may explain this gap, such as significant interindividual variability in autonomic responsiveness, the brief duration of film segments, and possible limitations in the sensitivity of SC and RR to identify modest regulatory effects in dynamic, naturalistic tasks. These metrics may be especially susceptible to noise or affected by nonspecific arousal, thereby constraining their discriminative efficacy within the present paradigm. Conversely, HR frequently exhibited considerable variation across experimental This underscores its role as a more reliable and stable autonomic indicator of regulatory effectiveness in emotionally charged, film-based tasks.

Concerning self-reported affect, both active and sham sessions resulted in a reduction of positive affect, although no significant alterations were noted in negative affect. These results presumably indicate the dominant impact of prolonged exposure to emotionally unfavorable stimuli, which may surpass the modulatory effects of short tDCS sessions or cognitive reappraisal procedures on subjective states. The observed decline in positive affect across both active and sham sessions is likely attributable to the prolonged exposure to aversive stimuli. The result underscores the potency of the induction paradigm and suggests that brief tDCS sessions may be insufficient to buffer against sustained emotional engagement at the subjective level. The divergence between physiological and self-reported results corresponds with research suggesting that subjective affect does not consistently reflect autonomic alterations, particularly in laboratory-induced emotional scenarios.

Although modest, the side effects observed across stimulation conditions may offer meaningful insights into the interpretation of our primary findings. Notably, the re-duction in self-reported fatigue following active dlPFC stimulation could be linked to enhanced heart rate modulation, potentially indicating reduced cognitive load as a result of increased dlPFC excitability. While participants consistently reported itching sensations during active stimulation in both prefrontal sites, some site-specific effects also emerged, such as increased anxiety in the sham vmPFC condition, which may reflect the distinct neurofunctional roles and circuit-level connectivity of the dlPFC and vmPFC during emotional processing. Moreover, differences in blinding effectiveness between stimulation sites (75% correct identification for dlPFC vs. 40% for vmPFC) suggest greater detectability of active stimulation in the dlPFC group, which could have introduced expectancy-related influences on the physiological outcomes.

Exploratory analyses of individual differences revealed that participants with greater difficulties in emotion regulation, as assessed by the CERQ, exhibited higher scores not only in maladaptive strategies like rumination and self-blame but also in various adaptive strategies, including acceptance and positive reappraisal. Furthermore, these patients exhibited heightened psychological symptoms across various dimensions. This trend may indicate a compensatory effort to manage discomfort through heightened cognitive exertion. However, it has minimal efficacy. Instead of depending exclusively on maladaptive responses, individuals facing regulatory difficulties seem to employ a broader range of strategies - potentially in an inconsistent or ineffectual manner. These findings support the translational potential of neuromodulation in improving emotion control, especially for those with affective dysregulation. Utilizing ecologically valid stimuli and incorporating physiological and subjective measures, our findings connect controlled cognitive activities. This approach incorporates real-world emotional processing, which enhances both mechanistic comprehension and clinical significance.

Several limitations warrant careful consideration. First, the sample was primarily composed of young adult female university students, which restricts the generalizability of findings across broader age, gender, educational, and clinical groups. Future studies should aim for more diverse samples to enhance external validity. Second, although emotionally evocative film clips improve ecological validity compared to static images, they still represent constrained, impersonal experiences. Such characteristics may limit their applicability to real-world emotion regulation, and subjective engagement was not directly assessed. Third, the absence of neuroimaging or electrophysiological data prevents direct inference about the neural mechanisms underlying the observed psycho-physiological changes. Combining tDCS with methods such as fMRI or EEG would improve mechanistic insight. Fourth, while participants were trained in three reappraisal strategies (positive reappraisal, fictional reappraisal, and distancing), these were not analyzed separately. Collapsing across strategies may have masked important differences or site-specific interactions. Fifth, although autonomic measures are informative, SC and RR may have been less sensitive to brief trials or subject to individual variability. Including subjective reports and additional physiological indices (e.g., HRV or pupillometry) could yield a more comprehensive understanding of regulation efficacy. Finally, it is important to note that the observed differences in blinding efficacy across stimulation areas represent a limitation, as expectancy effects may have influenced physiological outcomes, particularly in the dlPFC group, where blinding was less effective.

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

This study shows that anodal stimulation of the dlPFC can enhance emotion regulation, especially when combined with cognitive reappraisal strategies. This was reflected in sustained reductions in heart rate, suggesting that dlPFC stimulation may support both deliberate and more automatic regulatory processes. In contrast, vmPFC stimulation produced more variable effects, aligning with its broader role in affective integration rather than direct executive control. The use of emotionally evocative film clips also added ecological validity, bridging controlled experimentation with real-world emotion challenges.

Future research should build on these findings by systematically testing how different reappraisal strategies and montage configurations — including unihemispheric, bihemispheric, and interhemispheric approaches — can modulate not only the dlPFC but also broader inhibitory networks relevant for emotion regulation [

45]. Combining tDCS with central biomarkers such as ERPs [

46] alongside peripheral measures like heart rate and skin conductance could provide a more comprehensive understanding of when and how these networks are engaged.

Importantly, exploring the effects of repetitive stimulation sessions is crucial to determine whether cumulative effects can strengthen and sustain regulatory benefits over time. Recent evidence also shows that individual differences in regulation success and traits are linked to variability in lateral PFC and amygdala activity [

47], highlighting the potential for personalized protocols based on neural profiles.

In addition, emerging methods such as tRNS and tACS, especially when frequency- or phase-tuned to individual brain oscillations, deserve further investigation as complementary tools. Altogether, integrating ecologically valid tasks, advanced central and peripheral markers, optimized montage designs, and repeated sessions may substantially advance how neuromodulation protocols are tailored to strengthen emotion regulation in both research and clinical contexts.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. SM1. Emotion Regulation Training Guidelines; Table S1. Descriptions of the film clips used from the EMDB; Table S2. Visual Analogue Scale for tDCS Side Effects – dlPFC; Table S3. Visual Analogue Scale for tDCS Side Effects – vmPFC.

Author Contributions

CGC contributed to the study conceptualization and design, led data collection and curation, conducted formal analyses, and drafted the original manuscript. JL contributed to the methodological framework, supervised data analysis, coordinated project administration within the lab, and supported validation and manuscript review. RP assisted with participant recruitment, data acquisition and processing, and contributed to the manuscript’s revision. PM supported project supervision and validation, and contributed to critical review and editing. SC oversaw the overall project administration and supervision, contributed to conceptualization, methodology, and validation, and was involved in both drafting and revising the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was conducted at the Psychology Research Centre (CIPsi – PSI/01662), School of Psychology, University of Minho, and supported by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) through national funds (UID/01662/2020). C.G.C. was supported by a doctoral scholarship from FCT (https://doi.org/10.54499/2022.14063.BD).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Research in Social and Human Sciences at the University of Minho (Approval n. º CEICSH 060/2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are not publicly available due to ethical and privacy restrictions imposed by the Ethics Committee for Research in Social and Human Sciences at the University of Minho. However, anonymized summary data may be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author or Dr. Catarina Gomes Coelho.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all individuals who participated in the study and those who assisted in the data collection process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Gross, J.J. Emotion Regulation: Current Status and Future Prospects. Psychol Inq 2015, 26, 1–26, doi:10.1080/1047840X.2014.940781. [CrossRef]

- Aldao, A.; Nolen-Hoeksema, S.; Schweizer, S. Emotion-Regulation Strategies across Psychopathology: A Meta-Analytic Review. Clin Psychol Rev 2010, 30, 217–237, doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004. [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, S.G. Interpersonal Emotion Regulation Model of Mood and Anxiety Disorders. Cognit Ther Res 2014, 38, 483–492, doi:10.1007/s10608-014-9620-1. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.X.; Yin, B. A New Understanding of the Cognitive Reappraisal Technique: An Extension Based on the Schema Theory. Front Behav Neurosci 2023, 17, 1–11, doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2023.1174585. [CrossRef]

- Lau, C.Y.H.; Tov, W. Effects of Positive Reappraisal and Self-Distancing on the Meaningfulness of Everyday Negative Events. Front Psychol 2023, 14, 1–17, doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1093412. [CrossRef]

- Makowski, D.; Sperduti, M.; Pelletier, J.; Blondé, P.; La Corte, V.; Arcangeli, M.; Zalla, T.; Lemaire, S.; Dokic, J.; Nicolas, S.; et al. Phenomenal, Bodily and Brain Correlates of Fictional Reappraisal as an Implicit Emotion Regulation Strategy. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci 2019, 19, 877–897, doi:10.3758/s13415-018-00681-0. [CrossRef]

- Ferschmann, L.; Vijayakumar, N.; Grydeland, H.; Overbye, K.; Mills, K.L.; Fjell, A.M.; Walhovd, K.B.; Pfeifer, J.H.; Tamnes, C.K. Cognitive Reappraisal and Expressive Suppression Relate Differentially to Longitudinal Structural Brain Development across Adolescence. Cortex 2021, 136, 109–123, doi:10.1016/j.cortex.2020.11.022. [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, J.M.; MacNamara, A.; Kennedy, A.E.; Rabinak, C.A.; Rauch, S.A.M.; Liberzon, I.; Phan, K.L. Individual Differences in Cognitive Reappraisal Use and Emotion Regulatory Brain Function in Combat-Exposed Veterans with and without PTSD. Depress Anxiety 2017, 34, 79–88, doi:10.1002/da.22551. [CrossRef]

- Morawetz, C.; Bode, S.; Derntl, B.; Heekeren, H.R. The Effect of Strategies, Goals and Stimulus Material on the Neural Mechanisms of Emotion Regulation: A Meta-Analysis of FMRI Studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2017, 72, 111–128, doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.11.014. [CrossRef]

- Ochsner, K.N.; Silvers, J.A.; Buhle, J.T. Functional Imaging Studies of Emotion Regulation: A Synthetic Review and Evolving Model of the Cognitive Control of Emotion. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2012, 1251, E1–E24, doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06751.x. [CrossRef]

- Nejati, V.; Majdi, R.; Salehinejad, M.A.; Nitsche, M.A. The Role of Dorsolateral and Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex in the Processing of Emotional Dimensions. Sci Rep 2021, 1971, 1–12, doi:10.1038/s41598-021-81454-7. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Tanaka, S.C. Functions of the Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex in Emotion Regulation under Stress. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 1–12, doi:10.1038/s41598-021-97751-0. [CrossRef]

- Berboth, S.; Morawetz, C. Amygdala-Prefrontal Connectivity during Emotion Regulation: A Meta-Analysis of Psychophysiological Interactions. Neuropsychologia 2021, 153, 1–8, doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2021.107767. [CrossRef]

- Moore, M.; Iordan, A.D.; Hu, Y.; Kragel, J.E.; Dolcos, S.; Dolcos, F. Localized or Diffuse: The Link between Prefrontal Cortex Volume and Cognitive Reappraisal. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2016, 11, 1317–1325, doi:10.1093/scan/nsw043. [CrossRef]

- Kreibig, S.D. Autonomic Nervous System Activity in Emotion: A Review. Biol Psychol 2010, 84, 394–421, doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2010.03.010. [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Sánchez, N.; Jaén, I.; Escrig, M.A.; Lucas, I.; Pastor, M.C. Cognitive Reappraisal during Unpleasant Picture Processing: Subjective Self-Report and Peripheral Physiology. Psychophysiology 2019, 56, 1–15, doi:10.1111/psyp.13372. [CrossRef]

- Jentsch, V.L.; Wolf, O.T. The Impact of Emotion Regulation on Cardiovascular, Neuroendocrine and Psychological Stress Responses. Biol Psychol 2020, 154, 1–9, doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2020.107893. [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Muñoz, A.R.; Cuadrado, E.; Castillo-Mayén, R.; Luque, B.; Tabernero, C. Spontaneous Breathing Rate Variations Linked to Social Exclusion and Emotion Self-Assessment. Applied Psychophysiology Biofeedback 2022, 47, 231–237, doi:10.1007/s10484-022-09551-5. [CrossRef]

- Aderinto, N.; Olatunji, G.; Muili, A.; Kokori, E.; Edun, M.; Akinmoju, O.; Yusuf, I.; Ojo, D. A Narrative Review of Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation Techniques in Neuropsychiatric Disorders: Current Applications and Future Directions. Egypt J Neurol Psychiatr Neurosurg 2024, 60, 1–17, doi:10.1186/s41983-024-00824-w. [CrossRef]

- Kelley, N.J.; Gallucci, A.; Riva, P.; Lauro, L.J.R.; Schmeichel, B.J. Stimulating Self-Regulation: A Review of Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation Studies of Goal-Directed Behavior. Front Behav Neurosci 2019, 12, 1–20, doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00337. [CrossRef]

- Nitsche, M.A.; Paulus, W. Excitability Changes Induced in the Human Motor Cortex by Weak Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation. J Physiol 2000, 527, 633–639, doi:10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00633.x. [CrossRef]

- Feeser, M.; Prehn, K.; Kazzer, P.; Mungee, A.; Bajbouj, M. Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation Enhances Cognitive Control during Emotion Regulation. Brain Stimul 2014, 7, 105–112, doi:10.1016/j.brs.2013.08.006. [CrossRef]

- Brunoni, A.R.; Vanderhasselt, M.-A.; Boggio, P.S.; Fregni, F.; Dantas, E.M.; Mill, J.G.; Lotufo, P.A.; Benseñor, I.M. Polarity- and Valence-Dependent Effects of Prefrontal Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation on Heart Rate Variability and Salivary Cortisol. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2013, 38, 58–66, doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.04.020. [CrossRef]

- Hiser, J.; Koenigs, M. The Multifaceted Role of the Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex in Emotion, Decision Making, Social Cognition, and Psychopathology. Biol Psychiatry 2018, 83, 638–647, doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.10.030. [CrossRef]

- Malva, P. La; Crosta, A. Di; Prete, G.; Ceccato, I.; Gatti, M.; D’Intino, E.; Tommasi, L.; Mammarella, N.; Palumbo, R.; Domenico, A. Di The Effects of Prefrontal TDCS and Hf-TRNS on the Processing of Positive and Negative Emotions Evoked by Video Clips in First- and Third-Person. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 1–10, doi:10.1038/s41598-024-58702-7. [CrossRef]

- Holczer, A.; Vékony, T.; Klivényi, P.; Must, A. Frontal Two-Electrode Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation Protocols May Not Affect Performance on a Combined Flanker Go/No-Go Task. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 1–12, doi:10.1038/s41598-023-39161-y. [CrossRef]

- Woods, A.J.; Antal, A.; Bikson, M.; Boggio, P.S.; Brunoni, A.R.; Celnik, P.; Cohen, L.G.; Fregni, F.; Herrmann, C.S.; Kappenman, E.S.; et al. A Technical Guide to TDCS, and Related Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation Tools. Clinical Neurophysiology 2016, 127, 1031–1048, doi:10.1016/j.clinph.2015.11.012. [CrossRef]

- Espírito-Santo, H.; Pires, C.F.; Garcia, I.Q.; Daniel, F.; Silva, A.G. da; Fazio, R.L. Preliminary Validation of the Portuguese Edinburgh Handedness Inventory in an Adult Sample. Appl Neuropsychol Adult 2017, 24, 275–287, doi:10.1080/23279095.2017.1290636. [CrossRef]

- Oldfield, R.C. The Assessment and Analysis of Handedness: The Edinburgh Inventory. Neuropsychologia 1971, 9, 97–113, doi:10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4. [CrossRef]

- Martins, E.C.; Freire, M.; Ferreira-Santos, F. Examination of Adaptive and Maladaptive Cognitive Emotion Regulation Strategies as Transdiagnostic Processes: Associations with Diverse Psychological Symptoms in College Students. Stud Psychol (Bratisl) 2016, 58, 59–73, doi:10.21909/sp.2016.01.707. [CrossRef]

- Garnefski, N.; Kraaij, V.; Spinhoven, P. Negative Life Events, Cognitive Emotion Regulation and Emotional Problems. Pers Individ Dif 2001, 30, 1311–1327, doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00113-6. [CrossRef]

- Nelis, D.; Quoidbach, J.; Hansenne, M.; Mikolajczak, M. Measuring Individual Differences in Emotion Regulation: The Emotion Regulation Profile-Revised (ERP-R). Psychol Belg 2011, 51, 49, doi:10.5334/pb-51-1-49. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.; Cardoso, M.; Albuquerque, S.; Janeiro, C.; Alves, S. Escala de Resiliência Para Adultos (ERA). In Avaliação familiar: vulnerabilidade, stress e adaptação; Relvas, A.P., Major, S., Eds.; Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra, 2017; Vol. 2, pp. 37–62.

- Hjemdal, O.; Friborg, O.; Braun, S.; Kempenaers, C.; Linkowski, P.; Fossion, P. The Resilience Scale for Adults: Construct Validity and Measurement in a Belgian Sample. Int J Test 2011, 11, 53–70, doi:10.1080/15305058.2010.508570. [CrossRef]

- Canavarro, M.C. Inventário de Sintomas Psicopatológicos: BSI. In Testes e provas psicológicas em Portugal; Simões, M.R., Gonçalves, M., Almeida, L.S., Eds.; Serviço de Homossexualidade e Apoio ao Povo de Braga: Braga, 1999; Vol. 2, pp. 87–109.

- Derogatis, L.R. The Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI): Administration, Scoring and Procedures Manual; 3rd ed.; National Computer Systems: Minneapolis, 1993;

- Galinha, I.C.; Pais-Ribeiro, J.L. Contribuição Para o Estudo Da Versão Portuguesa Da Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS): II – Estudo Psicométrico. Análise Psicológica 2012, 23, 219–227, doi:10.14417/ap.84. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, S.; Leite, J.; Galdo-Álvarez, S.; Gonçalves, Ó.F. The Emotional Movie Database (EMDB): A Self-Report and Psychophysiological Study. Applied Psychophysiology Biofeedback 2012, 37, 279–294, doi:10.1007/s10484-012-9201-6. [CrossRef]

- Jasper, H.H. The Ten-Twenty Electrode System of the International Federation. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1958, 10, 371–375.

- Dan-Glauser, E.S.; Gross, J.J. The Temporal Dynamics of Two Response-focused Forms of Emotion Regulation: Experiential, Expressive, and Autonomic Consequences. Psychophysiology 2011, 48, 1309–1322, doi:10.1111/j.1469-8986.2011.01191.x. [CrossRef]

- Chou, C.; Marca, R. La; Steptoe, A.; Brewin, C.R. Heart Rate, Startle Response, and Intrusive Trauma Memories. Psychophysiology 2014, 51, 236–246, doi:10.1111/psyp.12176. [CrossRef]

- Carnevali, L.; Pattini, E.; Sgoifo, A.; Ottaviani, C. Effects of Prefrontal Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation on Autonomic and Neuroendocrine Responses to Psychosocial Stress in Healthy Humans. Stress 2020, 23, 26–36, doi:10.1080/10253890.2019.1625884. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, E.M. Stress Prevention by Modulation of Autonomic Nervous System (Heart Rate Variability): A Preliminary Study Using Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation. Open J Psychiatr 2012, 2, 113–122, doi:10.4236/ojpsych.2012.22016. [CrossRef]

- Ironside, M.; Browning, M.; Ansari, T.L.; Harvey, C.J.; Sekyi-Djan, M.N.; Bishop, S.J.; Harmer, C.J.; O’Shea, J. Effect of Prefrontal Cortex Stimulation on Regulation of Amygdala Response to Threat in Individuals With Trait Anxiety. JAMA Psychiatry 2018, 76, 1–8, doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.2172. [CrossRef]

- Leite, J.; Gonçalves, Ó.F.; Pereira, P.; Khadka, N.; Bikson, M.; Fregni, F.; Carvalho, S. The Differential Effects of Unihemispheric and Bihemispheric TDCS over the Inferior Frontal Gyrus on Proactive Control. Neurosci Res 2018, 130, 39–46, doi:10.1016/j.neures.2017.08.005. [CrossRef]

- Mendes, A.J.; Pacheco-Barrios, K.; Lema, A.; Gonçalves, Ó.F.; Fregni, F.; Leite, J.; Carvalho, S. Modulation of the Cognitive Event-Related Potential P3 by Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2022, 132, 894–907, doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.11.002. [CrossRef]

- Morawetz, C.; Basten, U. Neural Underpinnings of Individual Differences in Emotion Regulation: A Systematic Review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2024, 162, 1–12, doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2024.105727. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Overview of the experimental design: (A) Sequential stages of the study, including recruitment, baseline assessment, emotion regulation training, and two counterbalanced stimulation sessions (active and sham tDCS) targeting the dlPFC or vmPFC; (B) Structure of the experimental task during each session - The order of conditions, film clips, electrode placement, and stimulation type (active or sham) was randomized. *Note. Due to technical issues, the system failed to register responses from the Self-Assessment Manikin (valence and arousal), resulting in the loss of these data.

Figure 1.

Overview of the experimental design: (A) Sequential stages of the study, including recruitment, baseline assessment, emotion regulation training, and two counterbalanced stimulation sessions (active and sham tDCS) targeting the dlPFC or vmPFC; (B) Structure of the experimental task during each session - The order of conditions, film clips, electrode placement, and stimulation type (active or sham) was randomized. *Note. Due to technical issues, the system failed to register responses from the Self-Assessment Manikin (valence and arousal), resulting in the loss of these data.

Figure 2.

A. tDCS Montages: (a) Electrode placement based on the international 10-20 EEG system. (b) dlPFC stimulation montage: anodal electrode over F3 and cathodal electrode over F4 (bifrontal). (c) vmPFC stimulation montage: anodal electrode over Fp1 and cathodal electrode over Cz (frontal-midline). B. Peripheral Measures: (a) Electrocardiogram (ECG) setup for heart rate recording with three-lead chest configuration. (b) Electrodermal activity (EDA) measured via skin conductance sensors placed on the fingers. (c) Respiratory rate captured via thoracic belt transducer around the chest.

Figure 2.

A. tDCS Montages: (a) Electrode placement based on the international 10-20 EEG system. (b) dlPFC stimulation montage: anodal electrode over F3 and cathodal electrode over F4 (bifrontal). (c) vmPFC stimulation montage: anodal electrode over Fp1 and cathodal electrode over Cz (frontal-midline). B. Peripheral Measures: (a) Electrocardiogram (ECG) setup for heart rate recording with three-lead chest configuration. (b) Electrodermal activity (EDA) measured via skin conductance sensors placed on the fingers. (c) Respiratory rate captured via thoracic belt transducer around the chest.

Figure 3.

Mean heart rate (BPM) during negative film exposure for each condition, shown separately for dlPFC and vmPFC stimulation groups and conditions. Error bars show ± 1 SEM.

Figure 3.

Mean heart rate (BPM) during negative film exposure for each condition, shown separately for dlPFC and vmPFC stimulation groups and conditions. Error bars show ± 1 SEM.

Figure 4.

Mean skin conductance (μS) during negative film exposure for each condition, shown separately for dlPFC and vmPFC stimulation groups and conditions. Error bars show ± 1 SEM.

Figure 4.

Mean skin conductance (μS) during negative film exposure for each condition, shown separately for dlPFC and vmPFC stimulation groups and conditions. Error bars show ± 1 SEM.

Figure 5.

Mean respiratory rate (mV) during negative film exposure for each condition, shown separately for dlPFC and vmPFC stimulation groups and conditions. Error bars show ± 1 SEM.

Figure 5.

Mean respiratory rate (mV) during negative film exposure for each condition, shown separately for dlPFC and vmPFC stimulation groups and conditions. Error bars show ± 1 SEM.

Figure 6.

Mean heart rate change (BPM) over time during negative film exposure for each condition, shown separately for dlPFC (left) and vmPFC (right) stimulation groups. Heart rate values reflect difference scores (negative – neutral) across 5-second intervals. Error bars show ± 1 SEM. *p < .05 (Tukey-corrected).

Figure 6.

Mean heart rate change (BPM) over time during negative film exposure for each condition, shown separately for dlPFC (left) and vmPFC (right) stimulation groups. Heart rate values reflect difference scores (negative – neutral) across 5-second intervals. Error bars show ± 1 SEM. *p < .05 (Tukey-corrected).

Figure 7.

Mean skin conductance (μS) response over time during negative film exposure for each condition, shown separately for dlPFC (left) and vmPFC (right) stimulation groups. Skin conductance values reflect difference scores (negative–neutral) across 5-second intervals. Error bars represent ± 1 SEM.

Figure 7.

Mean skin conductance (μS) response over time during negative film exposure for each condition, shown separately for dlPFC (left) and vmPFC (right) stimulation groups. Skin conductance values reflect difference scores (negative–neutral) across 5-second intervals. Error bars represent ± 1 SEM.

Figure 8.

Mean respiratory rate (mV) over time during exposure to negative film stimuli, presented separately for dlPFC (left) and vmPFC (right) stimulation groups. Values reflect difference scores (negative – neutral) across 5-second time intervals. Error bars represent ± 1 SEM.

Figure 8.

Mean respiratory rate (mV) over time during exposure to negative film stimuli, presented separately for dlPFC (left) and vmPFC (right) stimulation groups. Values reflect difference scores (negative – neutral) across 5-second time intervals. Error bars represent ± 1 SEM.

Figure 9.

Changes in Positive and Negative Affect as measured by the PANAS before and after stimulation. Error bars indicate ±1 SD.

Figure 9.

Changes in Positive and Negative Affect as measured by the PANAS before and after stimulation. Error bars indicate ±1 SD.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

| |

dlPFC

(n = 46) |

|

vmPFC

(n = 39) |

|

|

| |

M (SD) /

n (%) |

M (SD) /

n (%) |

df |

χ2/t

|

p |

M (SD) /

n (%) |

M (SD) /

n (%) |

df |

χ2/t

|

p |

df |

χ2/t

|

p |

Without ER difficulties

(n = 26) |

With ER difficulties

(n = 20) |

dlPFC Total

(n = 46) |

Without ER difficulties

(n = 25) |

With ER difficulties

(n = 14) |

vmPFC Total

(n = 39) |

| Age |

28.4 (12.6) |

28.0 (9.5) |

28.2 (11.2) |

44 |

.13 |

.898 |

27.7 (12.0) |

25.8 (6.5) |

27.0 (10.3) |

37 |

.54 |

.590 |

83 |

.51 |

.613 |

| Sex |

|

|

|

1 |

3.55 |

.062 |

|

|

|

1 |

2.96 |

.123 |

1 |

3.46 |

.063 |

| Female |

22 (84.6) |

12 (60.0) |

34 (73.9) |

|

|

|

24 (96.0) |

11 (78.6) |

35 (89.7) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Male |

4 (15.4) |

8 (40.0) |

12 (26.1) |

|

|

|

1 (4.0) |

3 (21.4) |

4 (10.3) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Nationality |

|

|

1 |

1.33 |

.435 |

|

|

|

2 |

3.50 |

.174 |

2 |

4.97 |

.083 |

| Portuguese |

26 (100) |

19 (95) |

45 (97.8) |

|

|

|

23 (92.0) |

10 (71.4) |

33 (84.6) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Other nationalities |

- |

1 (5.0) |

1 (2.2) |

|

|

|

2 (8.0) |

3 (21.4) |

5 (12.8) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Dual nationality |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

|

- |

1 (7.1) |

1 (2.6) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Marital status |

|

3 |

5.10 |

.164 |

|

|

|

2 |

1.86 |

.394 |

3 |

3.28 |

.351 |

| Single |

21 (80.8) |

15 (75.0) |

36 (78.3) |

|

|

|

20 (80.0) |

13 (92.9) |

33 (84.6) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Cohabiting |

1 (3.8) |

4 (20.0) |

5 (10.9) |

|

|

|

2 (8.0) |

1 (7.1) |

3 (7.7) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Married |

1 (3.8) |

1 (5.0) |

2 (4.3) |

|

|

|

3 (12.0) |

- |

3 (7.7) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Divorced |

3 (11.5) |

- |

3 (6.5) |

|

|

|

- |

- |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Education |

|

|

2 |

2.25 |

.324 |

|

|

|

2 |

1.49 |

.475 |

2 |

4.90 |

.086 |

| Middle School |

4 (15.4) |

1 (5.0) |

5 (10.9) |

|

|

|

2 (8.0) |

- |

2 (5.1) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| High School |

5 (19.2) |

7 (35.0) |

12 (26.1) |

|

|

|

11 (44.0) |

8 (57.1) |

19 (48.7) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Higher Education |

17 (65.4) |

12 (60.0) |

29 (63.0) |

|

|

|

12 (48.0) |

6 (42.9) |

18 (46.2) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Occupation |

|

|

4 |

7.21 |

.125 |

|

|

|

3 |

3.54 |

.316 |

4 |

6.02 |

.198 |

| Student |

13 (50.0) |

6 (30.0) |

19 (41.3) |

|

|

|

15 (60.0) |

6 (42.9) |

21 (53.8) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Worker student |

1 (3.8) |

4 (20.0) |

5 (10.9) |

|

|

|

3 (12.0) |

5 (35.7) |

8 (20.5) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Worker |

10 (38.5) |

6 (30.0) |

16 (34.8) |

|

|

|

6 (24.0) |

3 (21.4) |

9 (23.1) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Unemployed |

1 (3.8) |

3 (15.0) |

4 (8.7) |

|

|

|

1 (4.0) |

- |

1 (2.6) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Pensioner or retired |

2 (7.7) |

- |

2 (4.3) |

|

|

|

- |

- |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Alcohol use |

|

|

1 |

1.77 |

.303 |

|

|

|

1 |

.39 |

.609 |

1 |

.06 |

.547 |

| Yes |

1 (3.8) |

3 (15.0) |

4 (8.7) |

|

|

|

2 (8.0) |

2 (14.3) |

4 (10.3) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

25 (96.2) |

17 (85.0) |

42 (91.3) |

|

|

|

23 (92.0) |

12 (85.7) |

35 (89.7) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Tobacco use |

|

|

1 |

.00 |

.650 |

|

|

|

1 |

.18 |

.595 |

1 |

2.27 |

.124 |

| Yes |

4 (15.4) |

3 (15.0) |

7 (15.2) |

|

|

|

1 (4.0) |

13 (92.9) |

2 (5.1) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

22 (84.6) |

17 (85.0) |

39 (84.8) |

|

|

|

24 (96.0) |

1 (7.1) |

37 (94.9) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ER Profile |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Adaptive ER |

22.58 (8.98) |

27.10

(12.70) |

24.54 (10.86) |

32.74 |

-1.35 |

.185 |

16.52

(8.37) |

29.64

(10.01) |

21.23 (10.92) |

37 |

-4.38 |

.000 |

83 |

1.40 |

.166 |

| Maladaptive ER |

3.69

(2.99) |

7.30

(4.39) |

5.26

(4.05) |

31.89 |

-3.16 |

.003 |

6.68

(5.00) |

6.71

(5.68) |

6.69

(5.18) |

37 |

-.02 |

.984 |

83 |

-1.43 |

.156 |

| Cognitive Emotion Regulation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Acceptance |

11.15

(2.87) |

14.60

(3.09) |

12.65 (3.40) |

44 |

-3.91 |

.000 |

12.04

(3.20) |

15.07

(3.32) |

13.13 (3.52) |

37 |

-2.81 |

.008 |

83 |

-.63 |

.528 |

| Positive refocusing |

10.96

(2.79) |

13.15

(3.63) |

11.91 (3.33) |

44 |

-2.31 |

.025 |

10.88

(3.56) |

11.50

(4.43) |

11.10 (3.85) |

37 |

-.48 |

.636 |

83 |

1.04 |

.301 |

| Refocus on planning |

13.08

(2.70) |

15.15

(3.33) |

13.98 (3.13) |

44 |

-2.33 |

.024 |

13.16

(3.09) |

15.93

(1.56) |

14.15 (3.35) |

37 |

-2.67 |

.011 |

83 |

-.25 |

.803 |

| Positive reappraisal |

13.15

(3.55) |

14.65

(3.73) |

13.80 (3.67) |

44 |

-1.39 |

.173 |

11.96

(3.90) |

15.64

(3.88) |

13.28 (4.24) |

37 |

-2.84 |

.007 |

83 |

.61 |

.544 |

| Putting into perspective |

11.69

(3.40) |

13.50

(3.49) |

12.48 (3.52) |

44 |

-1.77 |

.084 |

12.56

(3.53) |

12.79

(3.36) |

12.64 (3.42) |

37 |

-.195 |

.846 |

83 |

-.22 |

.830 |

| Self-blame |

8.38

(2.33) |

12.15

(2.83) |

10.02 (3.16) |

44 |

-4.94 |

.000 |

9.48

(3.31) |

12.86