Submitted:

16 December 2025

Posted:

17 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

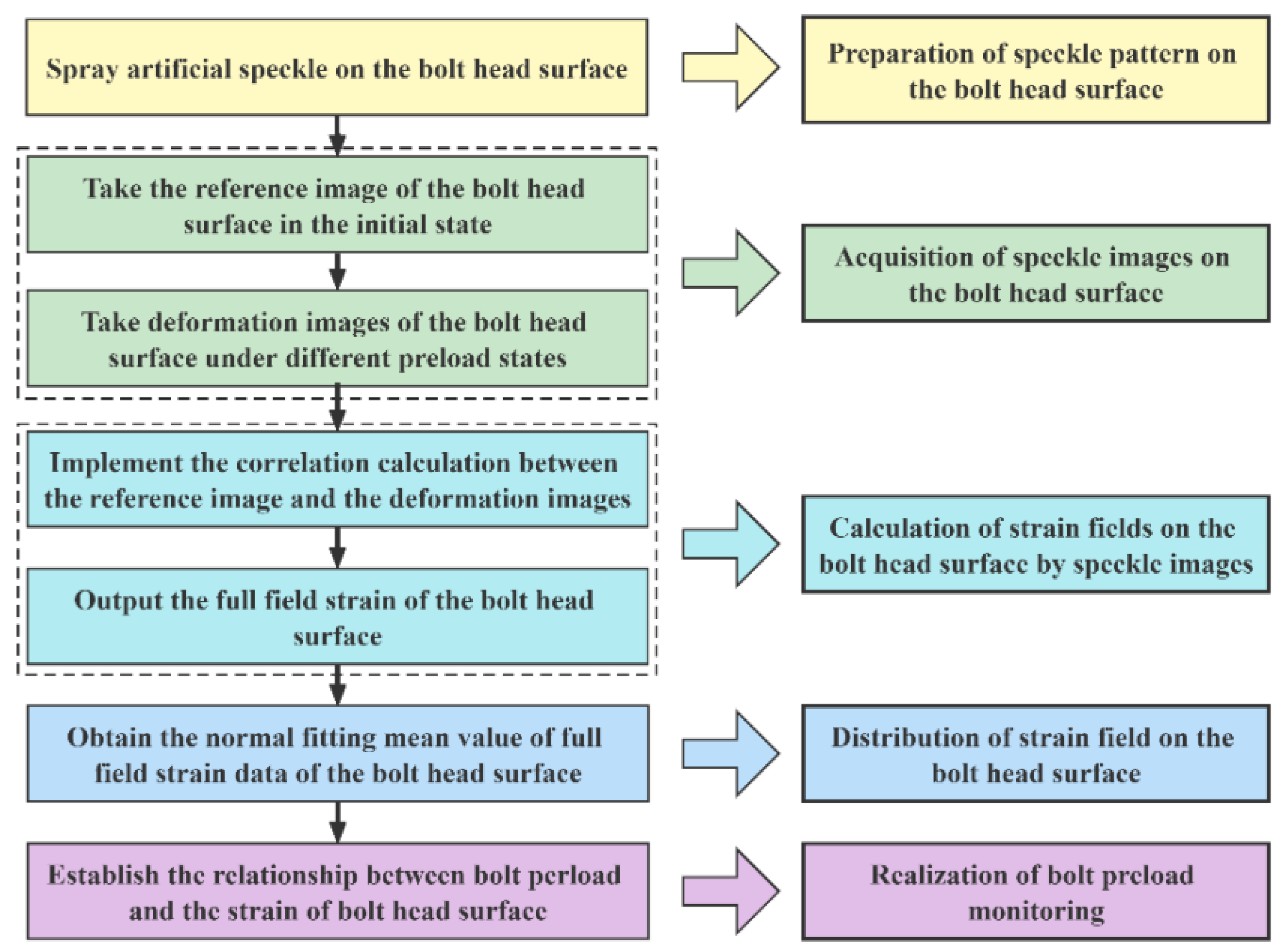

2. Methodology

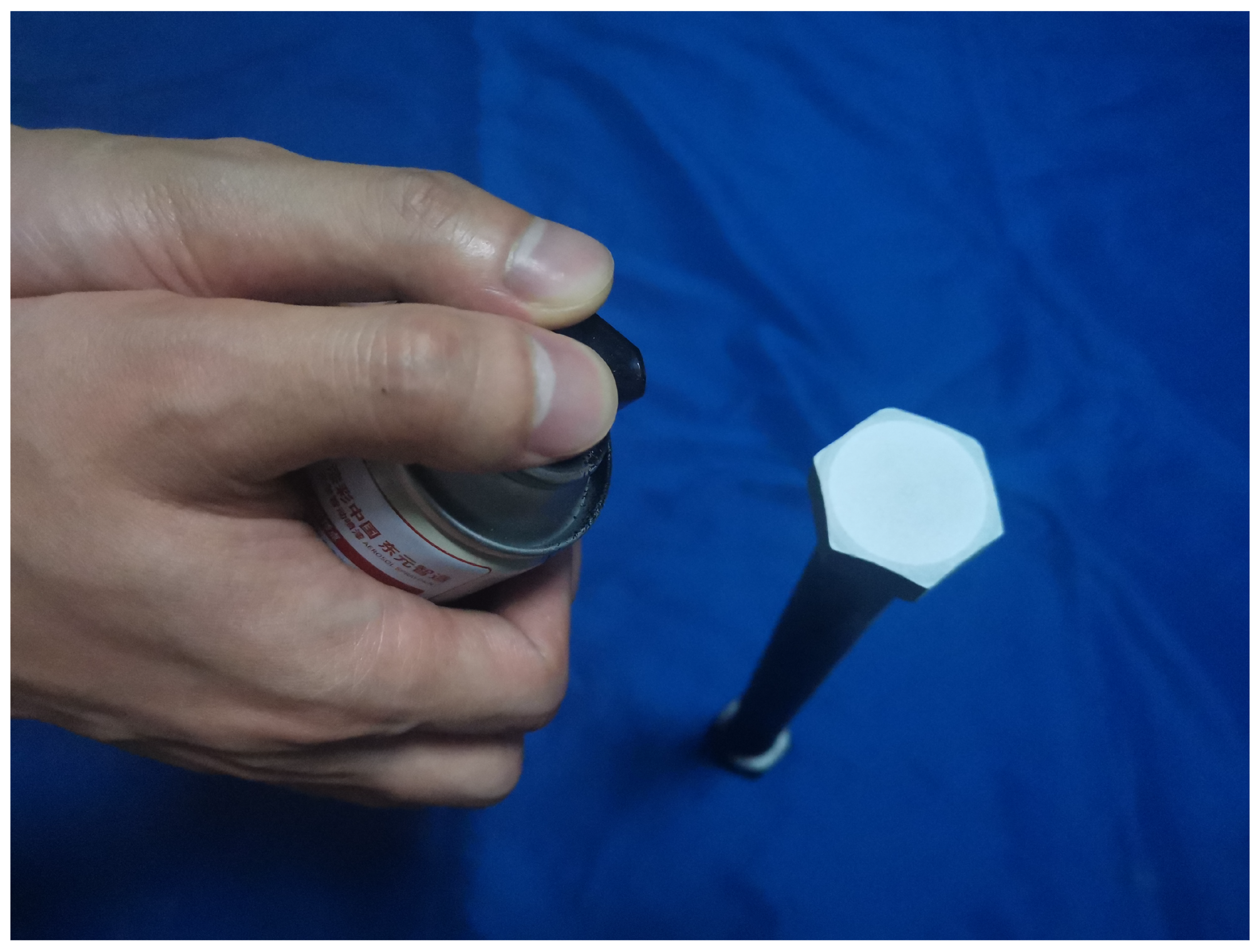

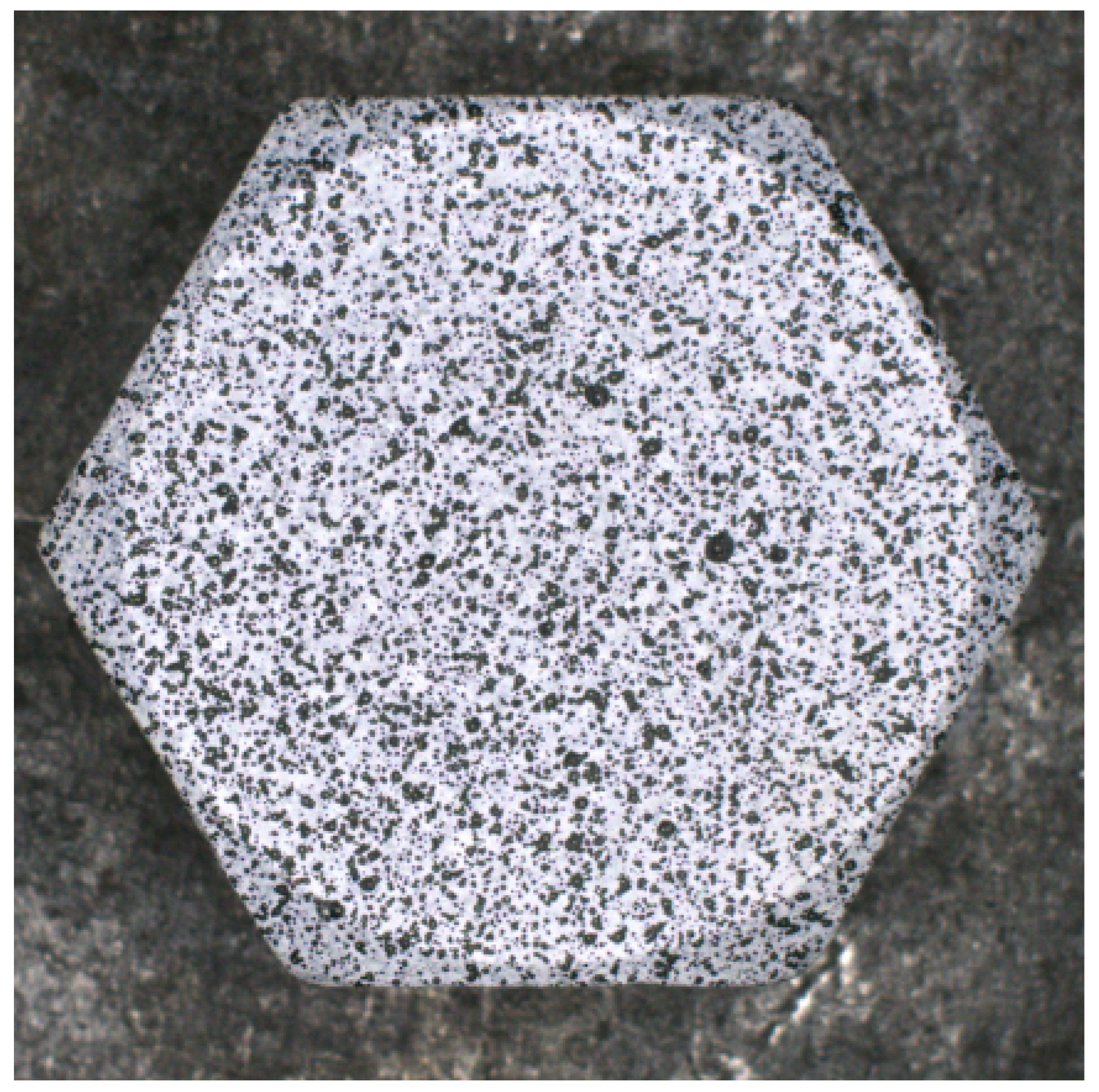

2.1. Preparation of Speckle Pattern on the Bolt Head Surface

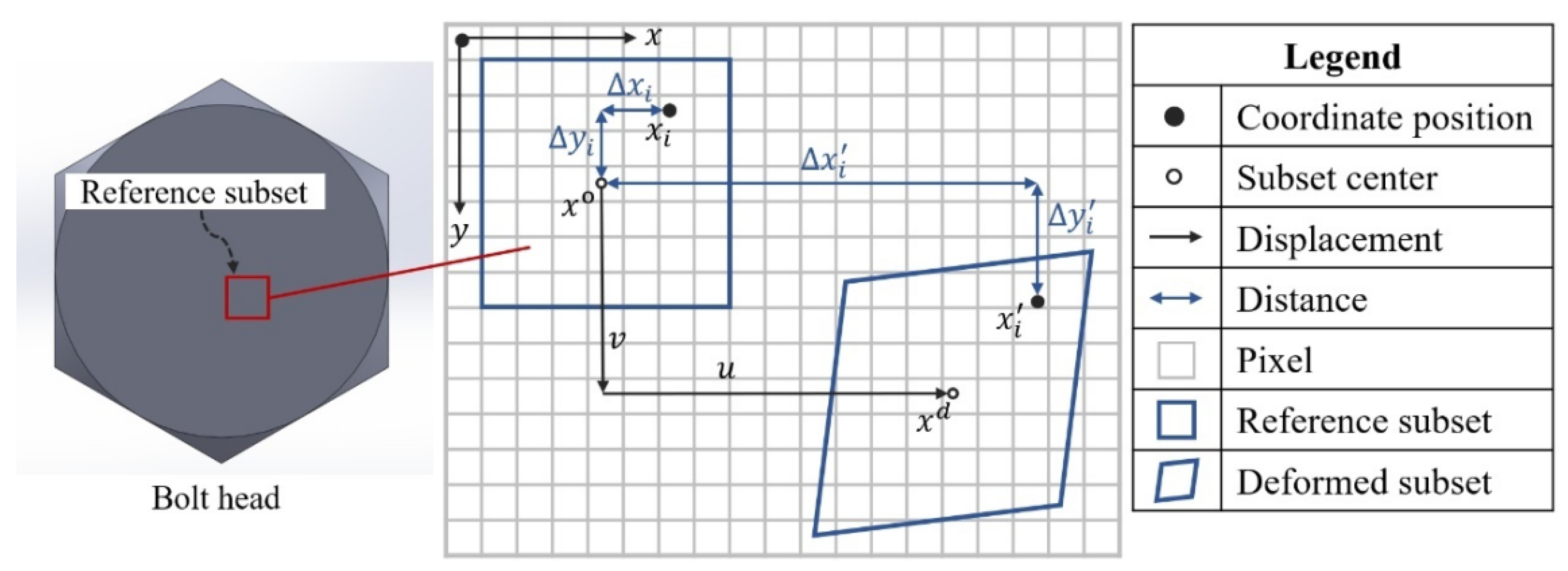

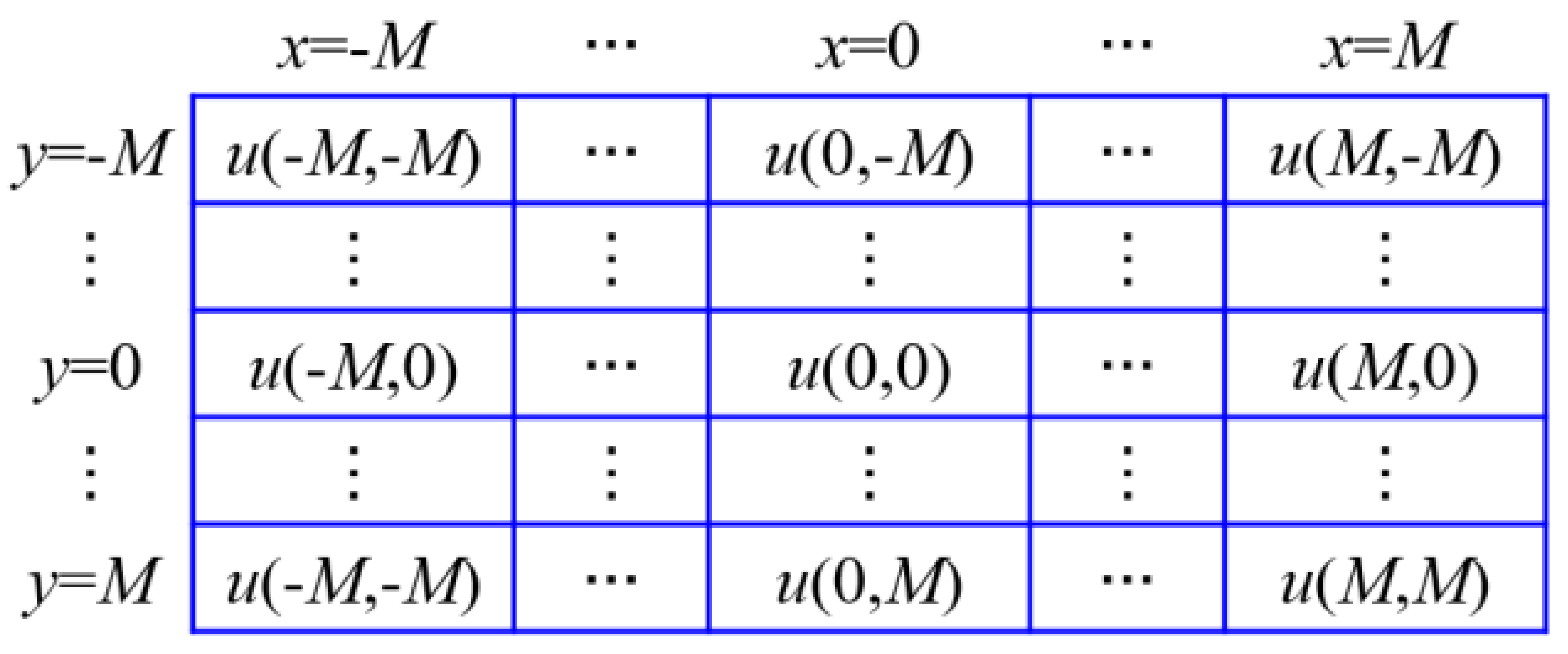

2.2. Computation of Strain Fields on the Bolt Head Surface Using Speckle Images

3. Experimental Verification

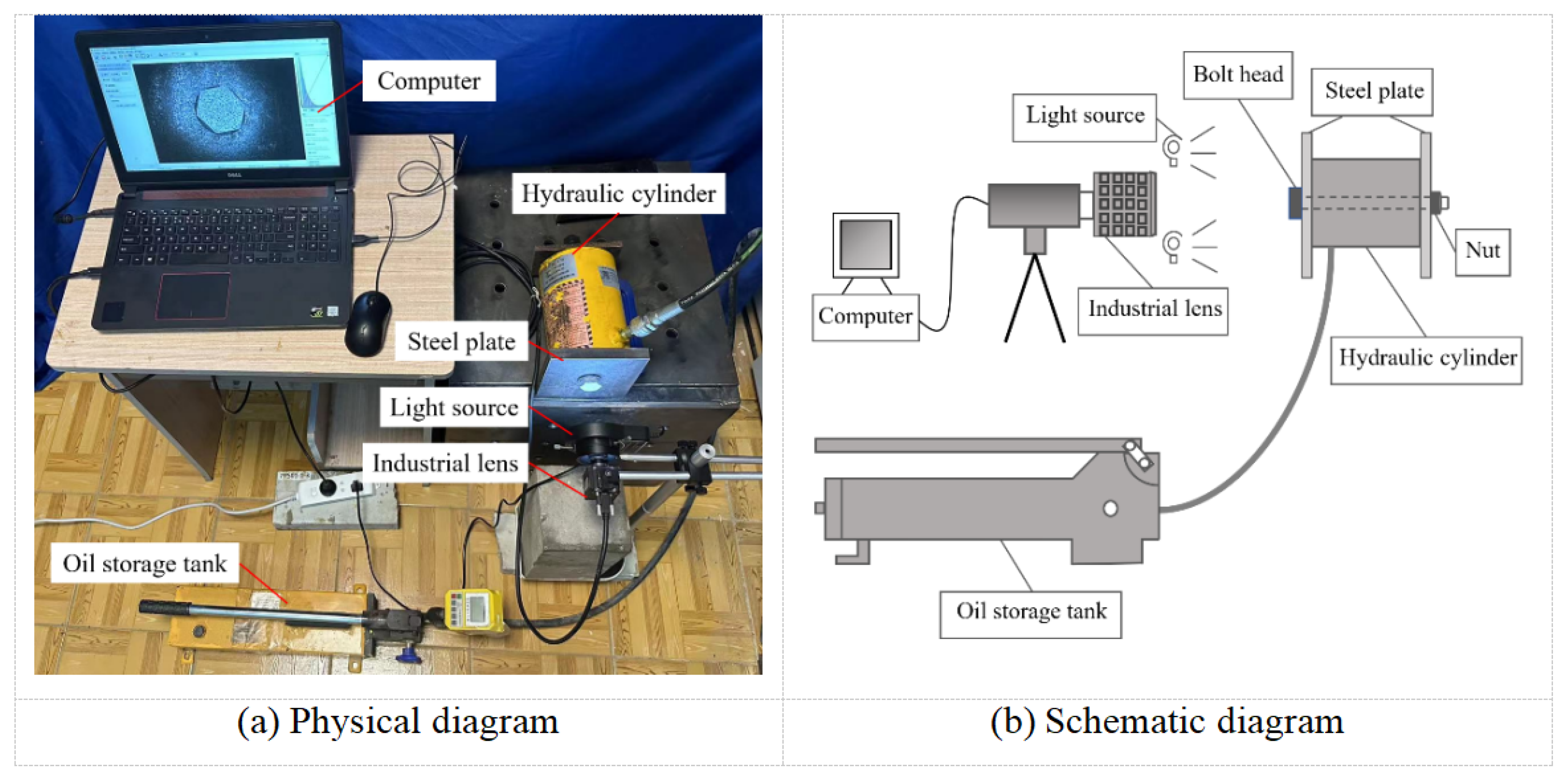

3.1. Instrumentation Setup

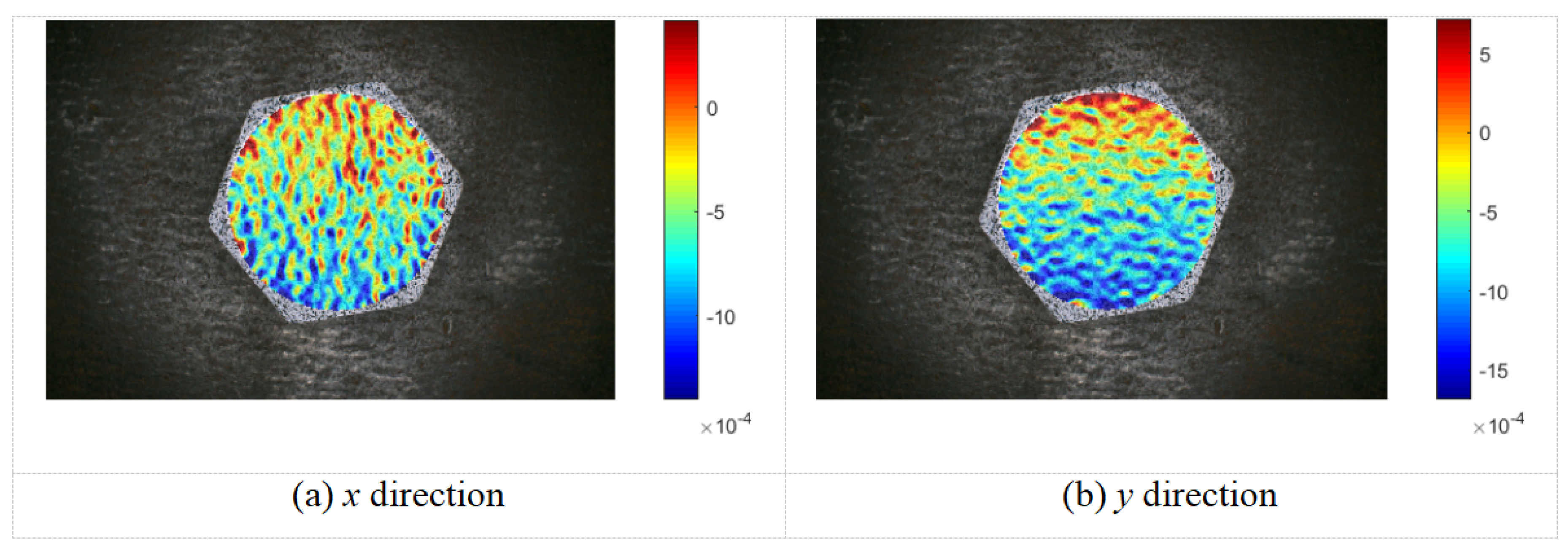

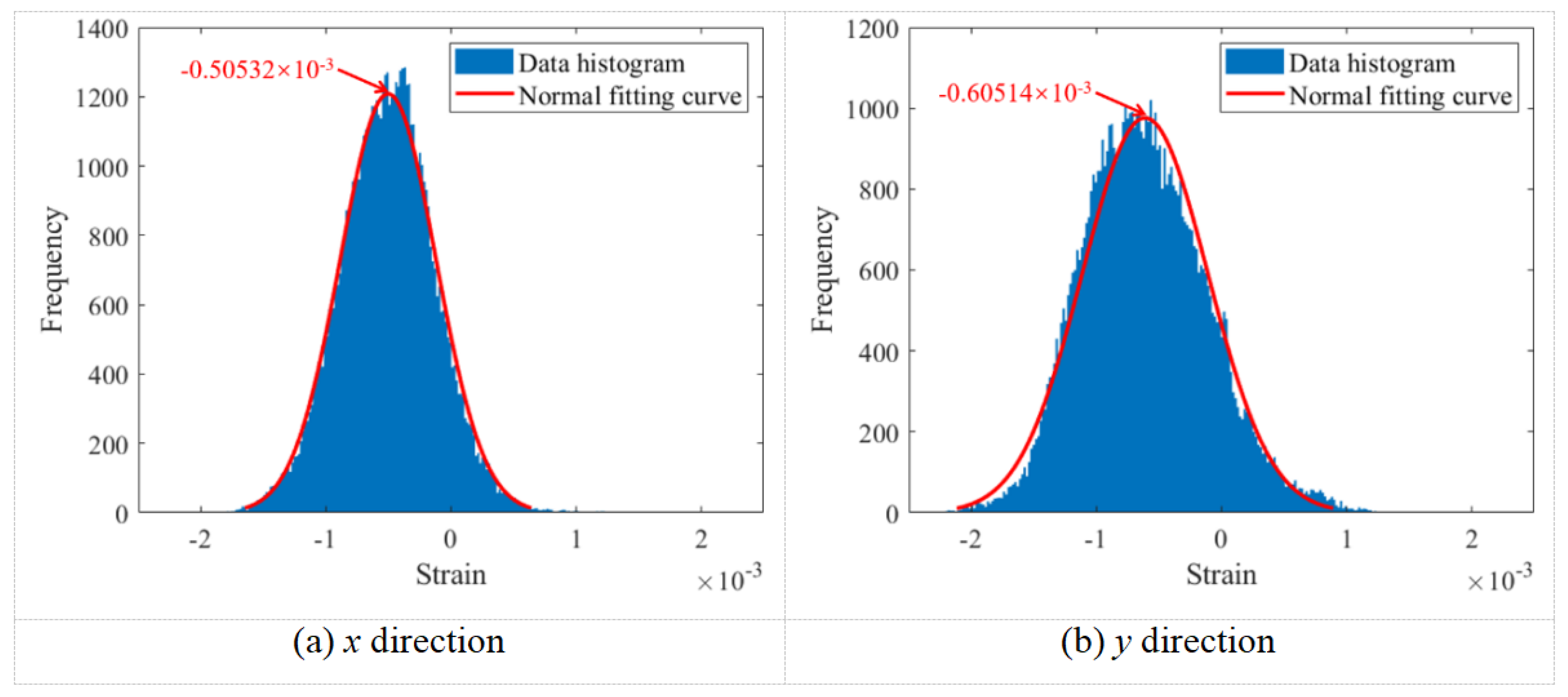

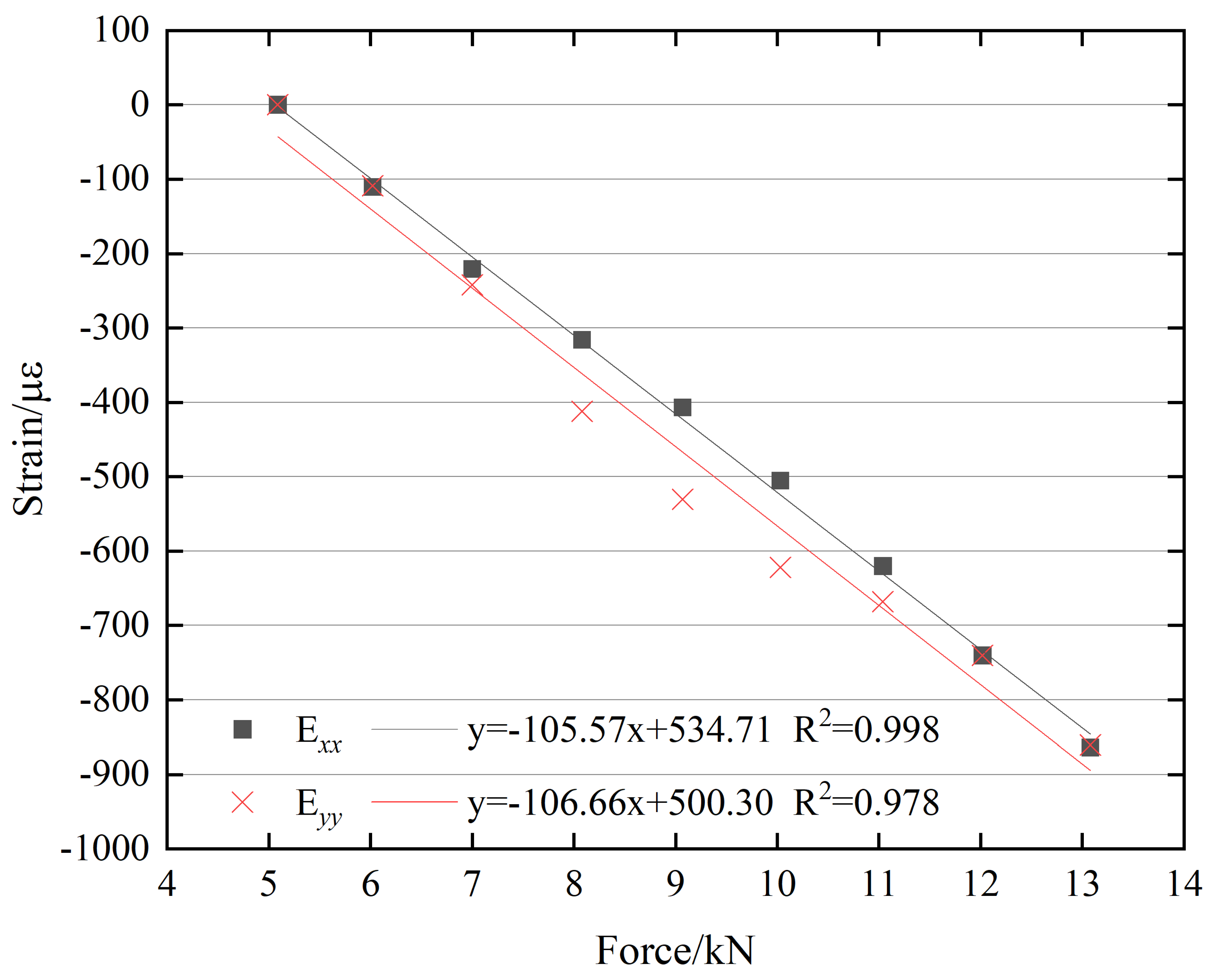

3.2. Relationship Between Preload and Strain

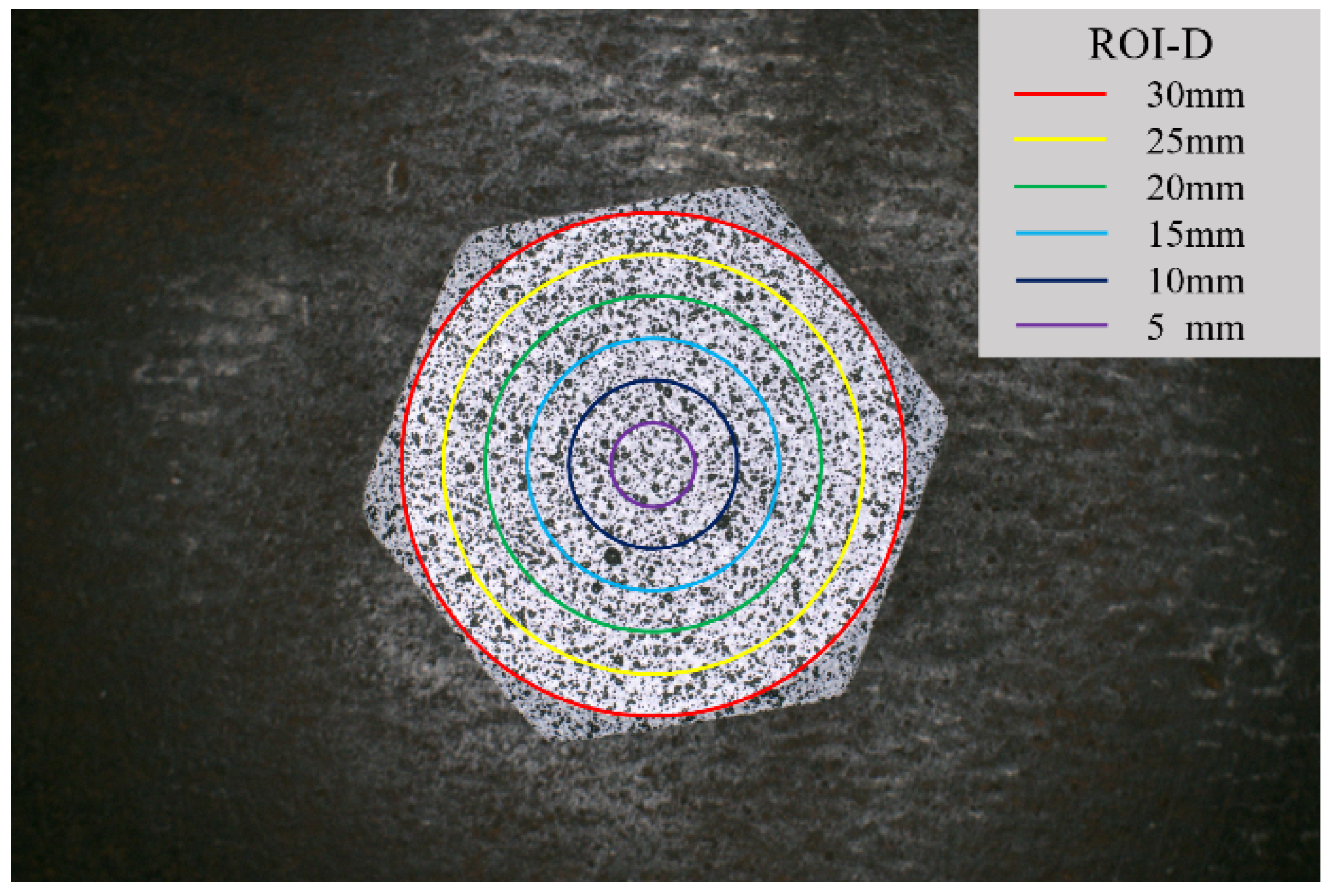

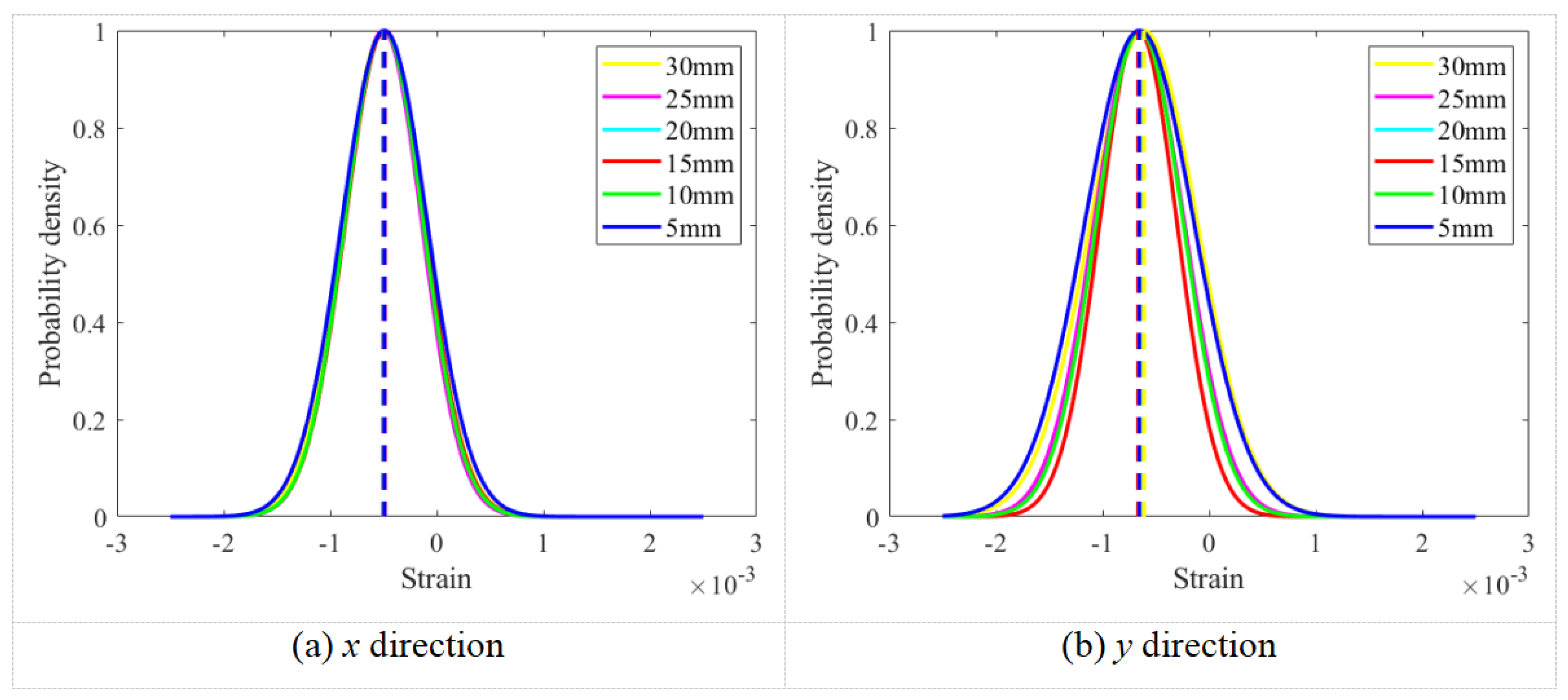

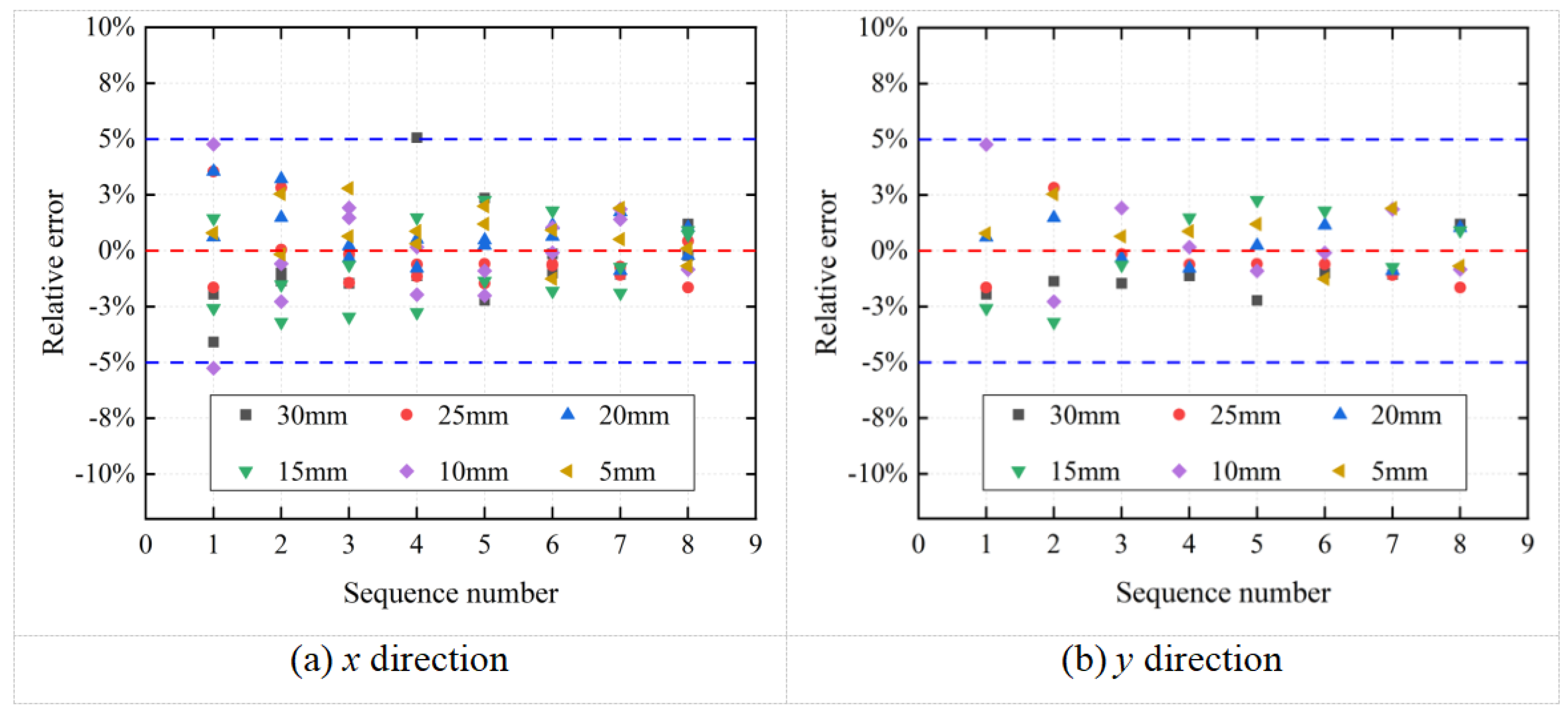

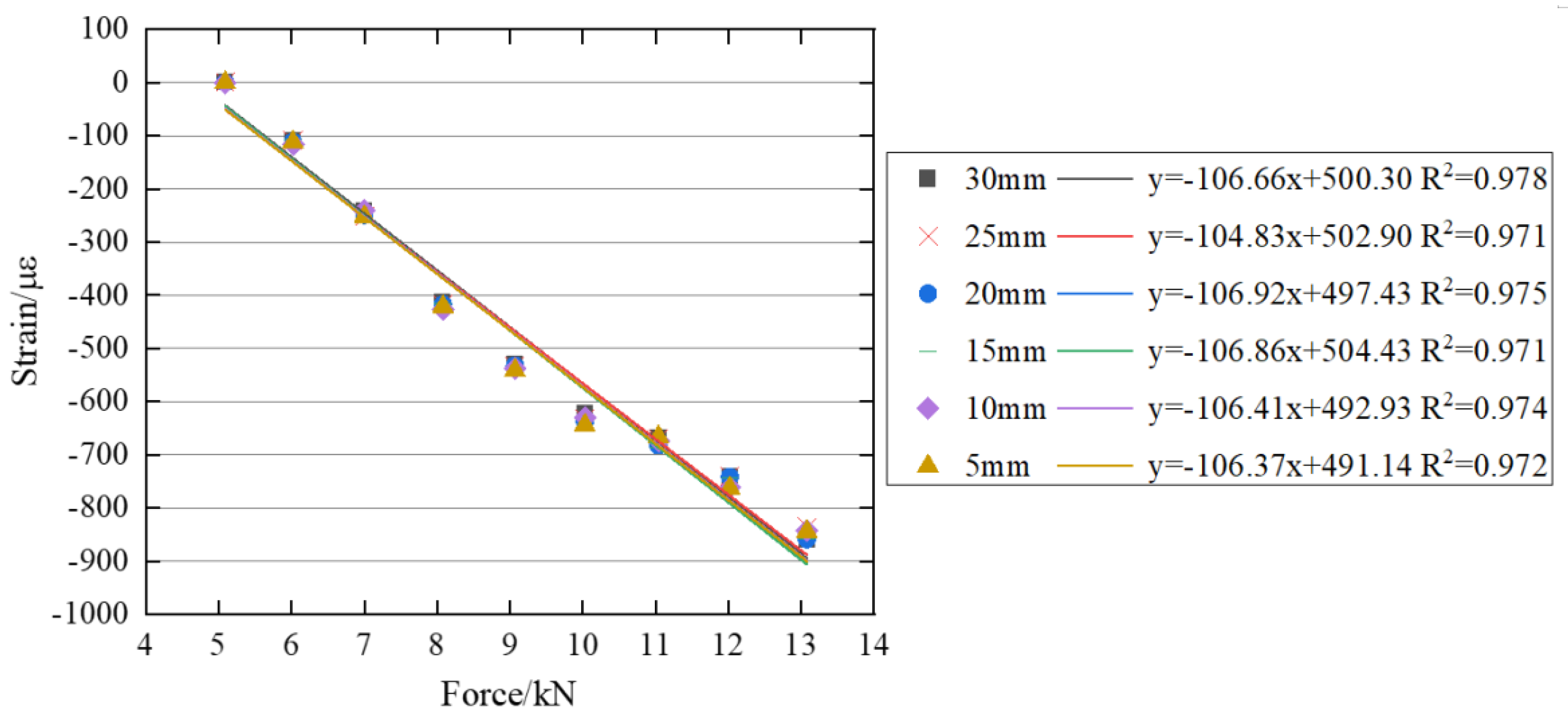

3.3. Influence of Region of Interest Selection

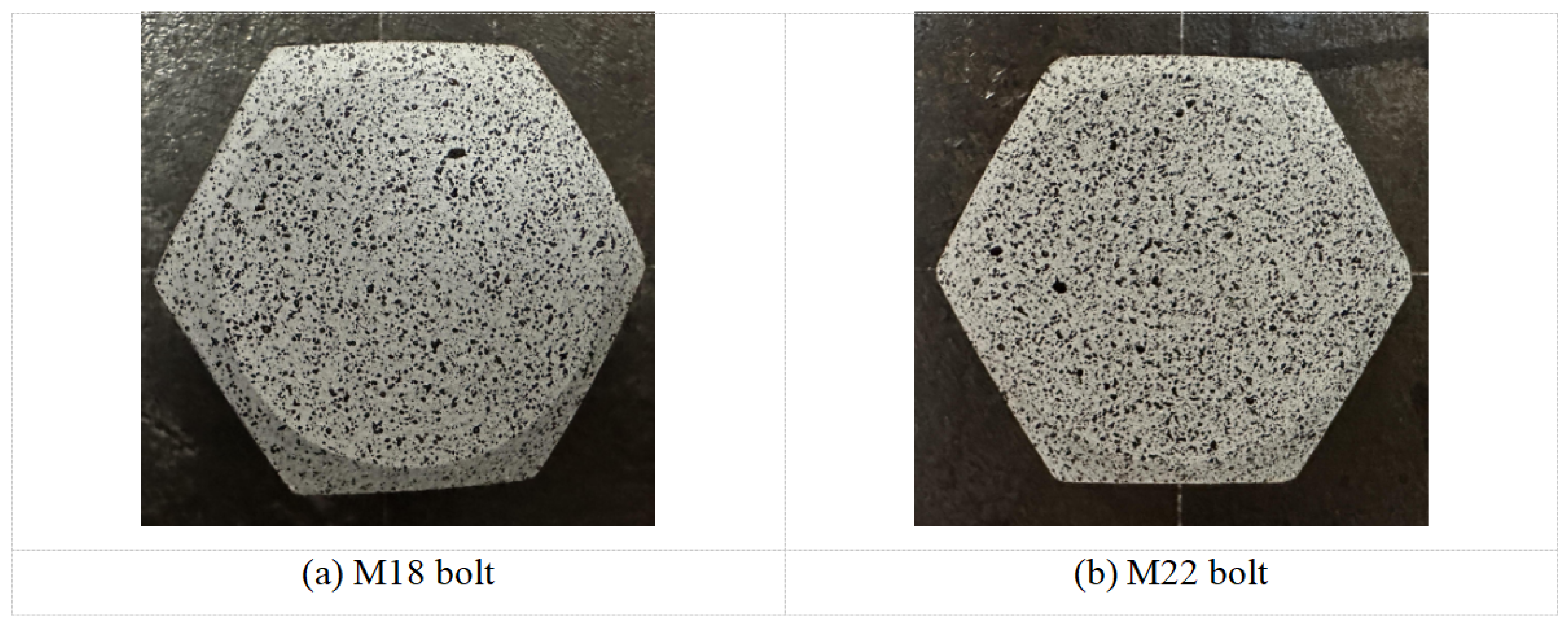

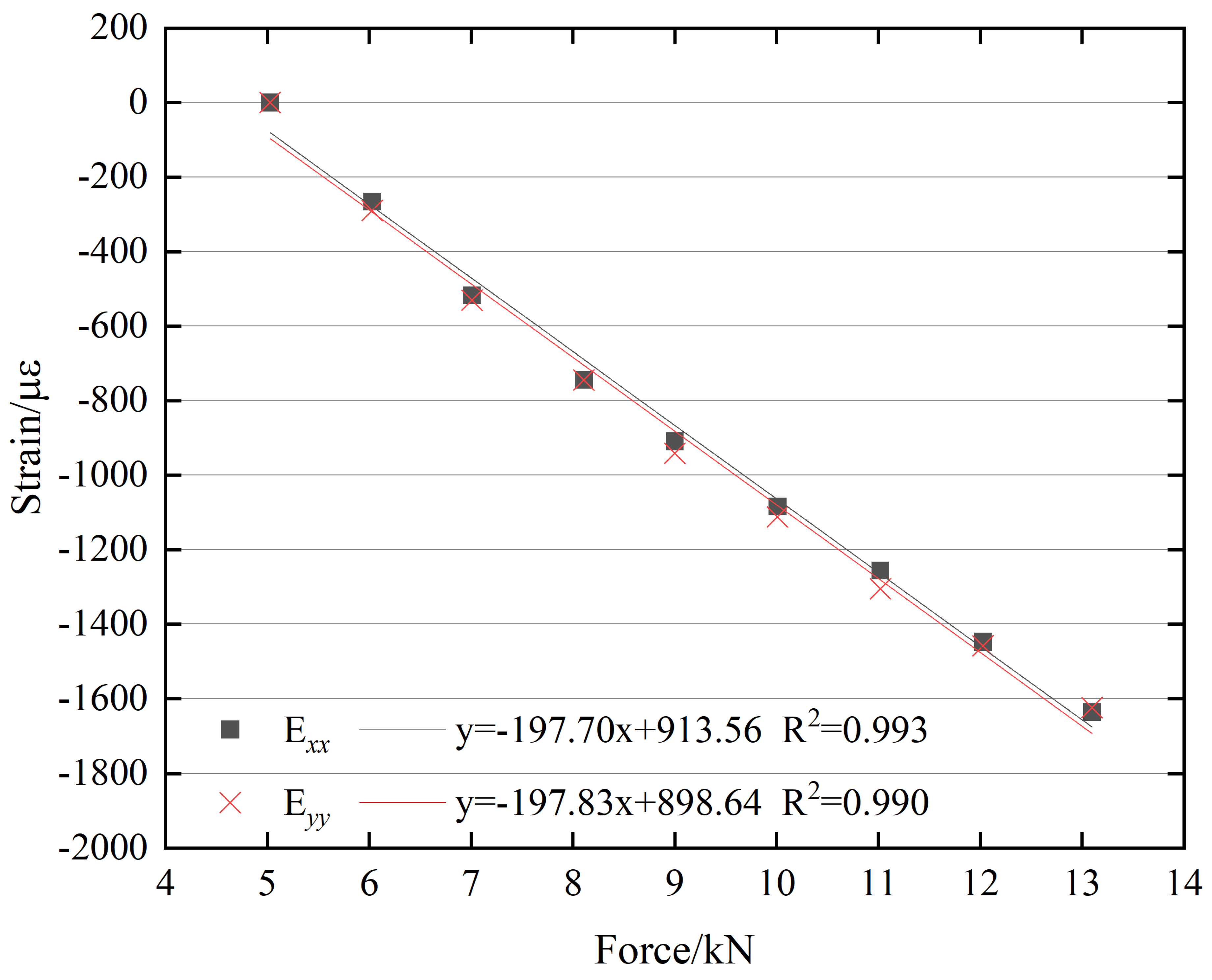

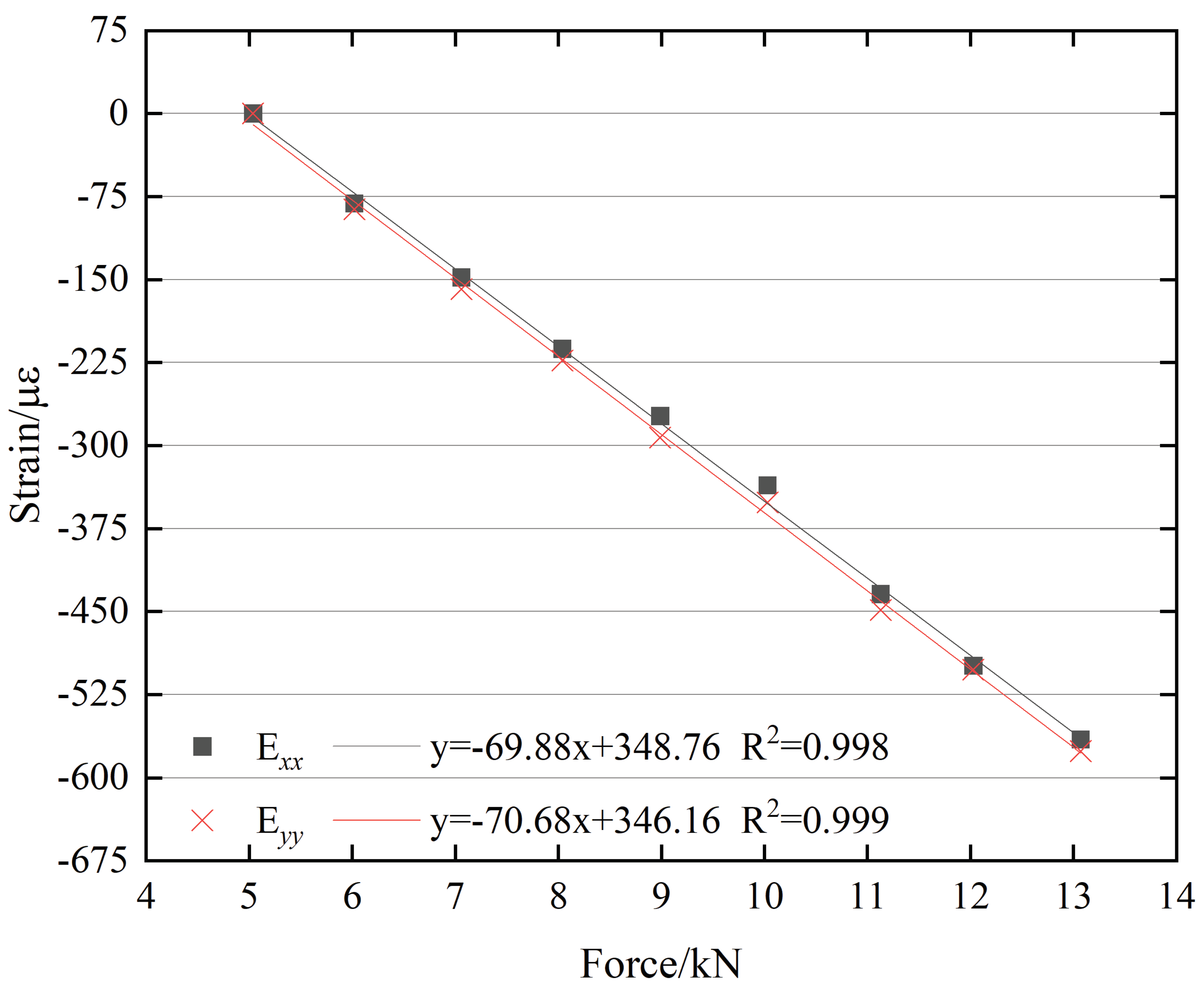

3.4. Verification Using Other Bolts Types

4. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guo, H.; Zhong, J.; Feng, B.; Chen, Y.; Zhong, S. Detection Method for Bolt Loosening Based on Summation Coefficient of Absolute Spectrum Ratio. Sensors 2025, 25, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.T.; Lee, J.M.; Huh, J.; Ahn, J.H. Tensile behaviors of friction bolt connection with bolt head corrosion damage: Experimental research B. Engineering Failure Analysis 2016, 59, 526–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Chen, Z.; Song, G. Monitoring of multi-bolt connection looseness using entropy-based active sensing and genetic algorithm-based least square support vector machine. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2020, 136, 106507. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Liu, J.; Gong, H.; Deng, X. A comprehensive review of loosening detection methods for threaded fasteners. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2022, 168, 108652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caccese, V.; Mewer, R.; Vel, S.S. Detection of bolt load loss in hybrid composite/metal bolted connections. Engineering structures 2004, 26, 895–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, R.; Shen, R.; Zhang, S.; Xue, S. A review of bolt tightening force measurement and loosening detection. Sensors 2020, 20, 3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Sun, X.; Su, W.; Xue, Z. Bolt loosening detection based on audio classification. Advances in Structural Engineering 2019, 22, 2882–2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Q.; Zhu, J.; Ho, S.C.M.; Song, G. Tapping and listening: A new approach to bolt looseness monitoring. Smart Materials and Structures 2018, 27, 07LT02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Song, G.; Mo, Y.L. Shear loading detection of through bolts in bridge structures using a percussion-based one-dimensional memory-augmented convolutional neural network. Computer-Aided Civil and Infrastructure Engineering 2021, 36, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, R.; Lv, Y.; Kong, Q.; Song, G. Percussion-based bolt looseness monitoring using intrinsic multiscale entropy analysis and BP neural network. Smart Materials and Structures 2019, 28, 125001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Ho, S.C.M.; Huo, L.; Song, G. A novel fractal contact-electromechanical impedance model for quantitative monitoring of bolted joint looseness. Ieee Access 2018, 6, 40212–40220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritdumrongkul, S.; Abe, M.; Fujino, Y.; Miyashita, T. Quantitative health monitoring of bolted joints using a piezoceramic actuator–sensor. Smart materials and structures 2003, 13, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Li, F. Bolt looseness monitoring based on damping measurement by using a quantitative electro-mechanical impedance method. Smart Materials and Structures 2022, 31, 095022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Song, G. Bolt early looseness monitoring using modified vibro-acoustic modulation by time-reversal. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2019, 130, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalla, S.; Vittal, P.A.; Veljkovic, M. Piezo-impedance transducers for residual fatigue life assessment of bolted steel joints. Structural Health Monitoring 2012, 11, 733–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Wang, F.; Song, G. Monitoring of bolt looseness using piezoelectric transducers: Three-dimensional numerical modeling with experimental verification. Journal of Intelligent Material Systems and Structures 2020, 31, 911–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amerini, F.; Meo, M. Structural health monitoring of bolted joints using linear and nonlinear acoustic/ultrasound methods. Structural health monitoring 2011, 10, 659–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, N. Bolt loosening angle detection technology using deep learning. Structural Control and Health Monitoring 2019, 26, e2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T.C.; Park, J.H.; Jung, H.J.; Kim, J.T. Quasi-autonomous bolt-loosening detection method using vision-based deep learning and image processing. Automation in Construction 2019, 105, 102844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godara, A.; Raabe, D. Microstrain localisation measurement in epoxy FRCs during plastic deformation using a digital image correlation technique coupled with scanning electron microscopy. Nondestructive Testing and Evaluation 2008, 23, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y. In-situ evaluation of C/SiC composites via an ultraviolet imaging system and microstructure based digital image correlation. Nondestructive Testing and Evaluation 2018, 33, 427–437. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.; Pan, B. Mirror-assisted panoramic-digital image correlation for full-surface 360-deg deformation measurement. Measurement 2019, 132, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, K.; Sheidaei, A.; Afshar, A.; Baqersad, J. Full-field strain prediction using mode shapes measured with digital image correlation. Measurement 2019, 139, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, L.; Calloch, S.; Hild, F.; Marco, Y. Digital image correlation used to analyze the multiaxial behavior of rubber-like materials. European Journal of Mechanics-A/Solids 2001, 20, 169–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reder, C.; Loidl, D.; Puchegger, S.; Gitschthaler, D.; Peterlik, H.; Kromp, K.; Khatibi, G.; Betzwar-Kotas, A.; Zimprich, P.; Weiss, B. Non-contacting strain measurements of ceramic and carbon single fibres by using the laser-speckle method. Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing 2003, 34, 1029–1033. [Google Scholar]

- Gencturk, B.; Hossain, K.; Kapadia, A.; Labib, E.; Mo, Y.L. Use of digital image correlation technique in full-scale testing of prestressed concrete structures. Measurement 2014, 47, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Peña, C.; Lavatelli, A.; Balcaen, R.; Zappa, E.; Debruyne, D. A novel contactless bolt preload monitoring method using digital image correlation. Journal of Nondestructive Evaluation 2021, 40, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Xie, H.; Wang, Z. Equivalence of digital image correlation criteria for pattern matching. Applied optics 2010, 49, 5501–5509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.C.; Han, T.H. Fast normalized cross-correlation. Circuits, systems and signal processing 2009, 28, 819–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreier, H.W.; Braasch, J.R.; Sutton, M.A. Systematic errors in digital image correlation caused by intensity interpolation. Optical engineering 2000, 39, 2915–2921. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, B. Reliability-guided digital image correlation for image deformation measurement. Applied optics 2009, 48, 1535–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, B.; Xie, H.; Guo, Z.; Hua, T. Full-field strain measurement using a two-dimensional Savitzky-Golay digital differentiator in digital image correlation. Optical Engineering 2007, 46, 033601–033601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sequence number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preload (kN) | 6.02 | 7.00 | 8.08 | 9.07 | 10.03 | 11.04 | 12.02 | 13.08 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).