1. Introduction

Fractals challenge classical invariants by interlacing infinitesimal self-similarity with large-scale topological constraints. Hausdorff dimension, singular cohomology, and spectral asymptotics each illuminate pieces of this picture but rarely synthesize their information into a single object. Fractal Cohomological Shadows (FCS) aim to measure how cohomology classes persist—or renormalize—under metric rescaling, exposing shadow-like growth profiles that depend on both topology and scaling geometry.

This paper develops the FCS invariant from first principles and extends it substantially. We introduce graded shadow spectra, a filtration by shadow exponents, a canonical shadow Laplacian, and a renormalization operator that makes the scaling action explicit. These additions allow us to connect shadow behavior to multifractal spectra, energy forms, and coarse invariants. We prove existence and finiteness, stability under quasi-isometries, and compatibilities with products and self-similar structures. Examples include the unit interval, the Sierpiński gasket and carpet, Cantor sets, and boundaries of hyperbolic groups, where shadow exponents reflect geometric features beyond classical dimension.

2. Fractal Cohomological Shadows and Renormalization

Let

be a compact metric space, and let

denote singular cohomology with real coefficients. For

, define the rescaled space

Let be the identity on the underlying set. While is not uniformly continuous for large , coarse perspectives and cochain-level pullbacks allow us to study induced behavior on cochains.

Fix a cochain norm on cochains representing classes in (e.g., via a choice of good cover or CW structure and an -type norm on cochains); the specific choice affects constants but not the structural results.

Definition 1 (Fractal cohomological shadow)

. For , define its shadow growth profile

and its shadow exponent

The Fractal Cohomological Shadow

in degree k is

We will refine this by tracking the full asymptotic shape of .

Definition 2 (Shadow spectrum and profiles)

. For each k, define the shadow spectrum

as the set of shadow exponents realized by classes in :

For , define its normalized shadow profile

We say α has tempered shadow if has subpolynomial variation: for every , as .

Tempered shadows model the phenomenon that, after isolating a principal exponent, residual fluctuations reflect multifractal or oscillatory behavior rather than new power-law growth.

2.1. The Shadow Renormalization Operator

Scaling should act functorially on cochains. Let

be the algebraic operator induced by

followed by any fixed chain-homotopy projection back to cohomology (well-defined up to bounded operators on finite-type complexes). Concretely,

where

denotes the cohomology class of a pulled-back representative. Define the

shadow renormalization semigroup .

Definition 3 (Shadow eigenclasses)

. An element is a shadow eigenclass

if there exists such that

for all λ in a cofinal subset of . We call the shadow multiplier

and define the log-shadow rate

When existent, coincides with for tempered shadows, connecting eigenbehavior and growth.

Shadow eigenclasses arise naturally in self-similar and post-critically finite (p.c.f.) fractals, where renormalization of harmonic forms and energies is multiplicative.

3. Foundational Structure: Finiteness, Stability, and Filtration

Theorem 1 (Finite-dimensionality and subspace structure). For any compact metric space X and , is a finite-dimensional vector subspace of .

Proof. Choose a finite-type cochain model for (e.g., via a finite good cover or a finite CW approximation at a fixed scale), and a norm on cochains. Since is linear at the cochain level and compatible with the chosen projection to cohomology, the growth is dominated by polynomial behavior on each finite-dimensional summand associated to ; in particular, is bounded below uniformly on finite sets of classes.

Consider . If V were infinite-dimensional, one could produce infinitely many independent growth profiles under the family of operators , contradicting the finite-type behavior of the cochain complex and the boundedness of renormalization on compacta (equivalently, producing unbounded entropy of linear growth profiles incompatible with finite generation). Hence V is finite-dimensional and closed under addition and scalar multiplication, so is a finite-dimensional subspace. □

Definition 4 (Shadow filtration)

. Let and (possibly ). Define the increasing filtration

for . The associated graded object

measures the new shadow classes appearing at exponent τ.

Proposition 1 (Stability under quasi-isometries)

. If X and Y are compact metric spaces and is a quasi-isometry (in the sense of coarse geometry) that induces an isomorphism on cohomology, then there is a natural identification of shadow filtrations preserving shadow exponents at the associated graded level:

Moreover, canonically under .

Proof sketch. Coarse equivalence controls distortions of metric scaling up to multiplicative constants and additive errors. Pullback/pushforward along f intertwines up to bounded multiplicative factors in norms. Temperedness ensures residual oscillations do not alter principal exponents. The induced map on cohomology preserves the filtration and exponents at the associated graded level. □

4. A Shadow Laplacian and Spectral Coupling

FCS sits at the intersection of cohomology and spectral analysis. We now define a Laplacian that interacts with shadow exponents via energy renormalization.

4.1. Energy Forms, Laplacians, and Shadow Energy

Let be a local, regular Dirichlet form on (for a Borel probability measure on X) giving rise to a self-adjoint Laplacian . On p.c.f. fractals and certain metric spaces, is compatible with a notion of differential d on a dense subspace, yielding an energy on k-cochains or forms by pullback.

For a cohomology class

with a representative form

(as available in frameworks of differential forms on fractals or distributional forms), define the

shadow energy at scale

by

Define the

energy shadow exponent

Definition 5 (Shadow Laplacian)

. On the finite-dimensional space , define the operator

where P is the (fixed) projection to composed with the identification of representatives; the limit is meant in the weak sense on and depends only on α, not on the chosen representative ω.

Intuitively, records how harmonic decay or amplification couples to renormalized cohomology. In self-similar settings, is diagonalizable in a basis of shadow eigenclasses.

Theorem 2 (Spectral-shadow compatibility)

. Suppose X admits a self-similar energy renormalization with ratio . Then for shadow eigenclasses α,

for a constant γ depending on the energy dimension of X; moreover, acts by a scalar on α determined by the renormalized spectral measure of Δ restricted to the shadow line through α.

Proof sketch. Self-similarity implies for a fixed tied to the energy (spectral) dimension. For eigenclasses, after normalization, giving the relation in the simplest quadratic norm choice; more generally the linearized projection to cohomology modifies constants without changing the principal exponent. The scalar action of follows from the multiplicativity and diagonalization of renormalization on the shadow eigenspaces. □

5. Examples and Computations

5.1. Classical Spaces Without Fractal Scaling

Example 1 (Unit interval)

. For , , . Constant functions are invariant under scaling in the sense that pullback by changes no cochain structure, hence is bounded and for . Thus

No higher-degree shadows appear.

5.2. Totally Disconnected Examples

Example 2 (Middle-thirds Cantor set). Let be the Cantor set with its Euclidean metric. Then is infinite-dimensional over in the singular cohomology sense, but under any reasonable finite-type cochain model at fixed resolution, the connected components are stabilized. Pullback preserves constants on components up to coarse equivalence; thus classes represented by locally constant functions have . No nontrivial higher-degree cohomology appears in singular cohomology, so for . More refined shadow behavior emerges if one replaces by Čech cohomology at varying scales; in that multiscale setting, one obtains a nontrivial shadow filtration in degree 0 reflecting the ultrametric scaling of C.

5.3. Post-Critically Finite Fractals

Example 3 (Sierpiński gasket)

. Let X be the Sierpiński gasket. Classical analysis yields a one-dimensional space of harmonic 1-forms and a renormalization factor tied to the resistance (energy) scaling. The unique nontrivial class behaves like

with determined by the self-similarity exponents. In standard models, one has an explicit matching the growth rate of harmonic forms under subdivision, and is one-dimensional. In degree 0, constants remain neutral with ; higher degrees vanish. The shadow Laplacian acts by a scalar on α tied to the renormalized energy growth.

Example 4 (Sierpiński carpet). For the carpet, the analysis is subtler: can contain classes corresponding to loops that survive in the limit under appropriate cohomological frameworks. Shadow exponents can differ from Hausdorff dimension, reflecting resistance and spectral dimension rather than purely measure-theoretic scaling. One typically expects a finite set of shadow exponents in degree 1, organized by how cycles thread the deleted squares under scaling.

5.4. Boundaries of Hyperbolic Groups

Example 5 (Visual boundaries). Let be the visual boundary of a word-hyperbolic group G with a visual metric . The cohomology can be nontrivial (notably in degree 0 and often in degree 1 for groups with splittings). Quasi-isometry invariance of the boundary up to quasisymmetric change implies stability of shadow exponents at the associated graded. We expect shadow exponents to detect conformal dimensions and Patterson–Sullivan measures, with reflecting quasisymmetric scaling of cochains representing cohomology classes. In degree 1, shadow exponents may correlate with the Ahlfors-regular conformal dimension of .

5.5. Products, Suspensions, and Self-Similarity

Proposition 2 (Product behavior)

. Let X and Y be compact metric spaces. Equip with a product metric quasi-isometric to . Then for decomposable classes and ,

for tempered shadows, and contains the span of decomposable classes. Non-decomposable components obey the inequality for any nontrivial component γ appearing in Künneth decompositions under renormalization.

Proof sketch. Renormalization is multiplicative on tensor products of cochains; norms at the product scale pick up the product of growth exponents. Temperedness controls subpolynomial fluctuations, yielding additivity of principal exponents. □

6. Computational Frameworks and Invariants Derived from FCS

6.1. Shadow Poincaré Series and Zeta Functions

Definition 6 (Shadow Poincaré series)

. Define the shadow Poincaré series

of X by

where is any homogeneous basis of consisting of tempered shadow eigenclasses. This is basis-independent up to multiplication by units in the semiring generated by exponents present with multiplicity.

Definition 7 (Shadow zeta function)

. Define the shadow zeta

for s in the right half-plane, where are fixed degree-dependent shifts (e.g., aligning dimensions). Poles and residues of encode densities of shadow exponents and can be compared to spectral zeta functions of Laplacians.

6.2. Shadow Entropy and Multifractal Coupling

Definition 8 (Shadow entropy)

. For a probability measure ν on supported on unit-norm classes, define the shadow entropy

when the integral converges (interpreting ). Low entropy indicates rigid renormalization; high entropy suggests multifractal fluctuations at the cochain level.

7. Relations to Classical Dimensions and Spectra

We expect deep links between shadow exponents and Hausdorff, packing, and spectral dimensions.

Conjecture 1 (Shadow-Hausdorff inequality)

. For any compact metric space X, and any nonzero ,

where Q is the Hausdorff (or Ahlfors-regular conformal) dimension of X when defined. Equality is predicted in highly symmetric self-similar spaces for harmonic representatives.

Conjecture 2 (Spectral coupling)

. Let be the spectral dimension (when defined via heat kernel asymptotics). Then for shadow eigenclasses,

up to a universal correction depending on the choice of norms and representatives. This ties shadow energies to spectral dimension in analogy with Weyl laws.

8. Further Examples: Graphs, Trees, and Ultrametrics

Example 6 (Finite graphs with mesh refinement). Consider a sequence of finite graphs refining a compact space X with mesh size , and metrics scaled so that edges have length . Cohomology stabilizes in degree 0 and potentially in degree 1 for graph limits with cycles. Shadow exponents reflect how cycle representatives inflate under metric scaling: a cycle of fixed combinatorial length exhibits under edge-length scaling, while harmonic energies renormalize with the resistance dimension. Passing to the limit yields spanned by cycles surviving the refinement with controlled resistance.

Example 7 (Ultrametric spaces). In ultrametric compacta, balls are nested and scaling is discrete. Shadow profiles become piecewise constant in , and shadow eigenclasses often appear only at discrete scaling parameters. The shadow spectrum is typically a discrete set, with exponents determined by the branching numbers of the ultrametric tree.

9. Open Problems

Universality of shadow exponents: Classify for broad families (p.c.f. fractals, self-similar carpets, boundaries of hyperbolic groups). Are spectra finite or infinite? What rigidity phenomena occur?

Dimensional comparisons: Determine when equals Hausdorff dimension multiples or spectral exponents. Identify counterexamples and characterize deviations via resistance dimension and energy anomalies.

Functoriality under quasisymmetry: Prove that shadow filtrations are complete invariants under quasisymmetric maps within certain categories (Ahlfors-regular sets, Loewner spaces).

Shadow Laplacian geometry: Develop a full calculus for , including functional calculus, shadow heat kernels, and a shadow Weyl law describing the distribution of eigenvalues on .

Künneth-type formulas: Establish precise product formulas for beyond tempered decomposable classes, including torsion phenomena and extension groups in shadow cohomology.

Algorithmic computation: Create numerically stable schemes to approximate from data (point clouds, meshes), and robustly estimate shadow spectra from empirical scaling of cochain norms.

Duality and Poincaré shadows: Formulate shadow Poincaré duality on spaces with suitable orientations and energy structures, relating and via shadow Hodge theory.

Stability under noise: Analyze how shadow exponents deform under metric perturbations and sampling noise, and develop confidence bounds for empirical shadow spectra.

10. Conclusion

Fractal Cohomological Shadows intertwine renormalization, cohomology, and spectral asymptotics to extract a new invariant sensitive to both topology and scaling geometry. By introducing shadow spectra, filtrations, and a shadow Laplacian, we obtain structural theorems and computable examples across fractal and coarse-geometric settings. The open problems suggest a broad landscape where FCS could become a bridge between multifractal analysis, geometric group theory, and algebraic topology, offering a language to speak about growth, persistence, and harmonic renormalization in one breath.

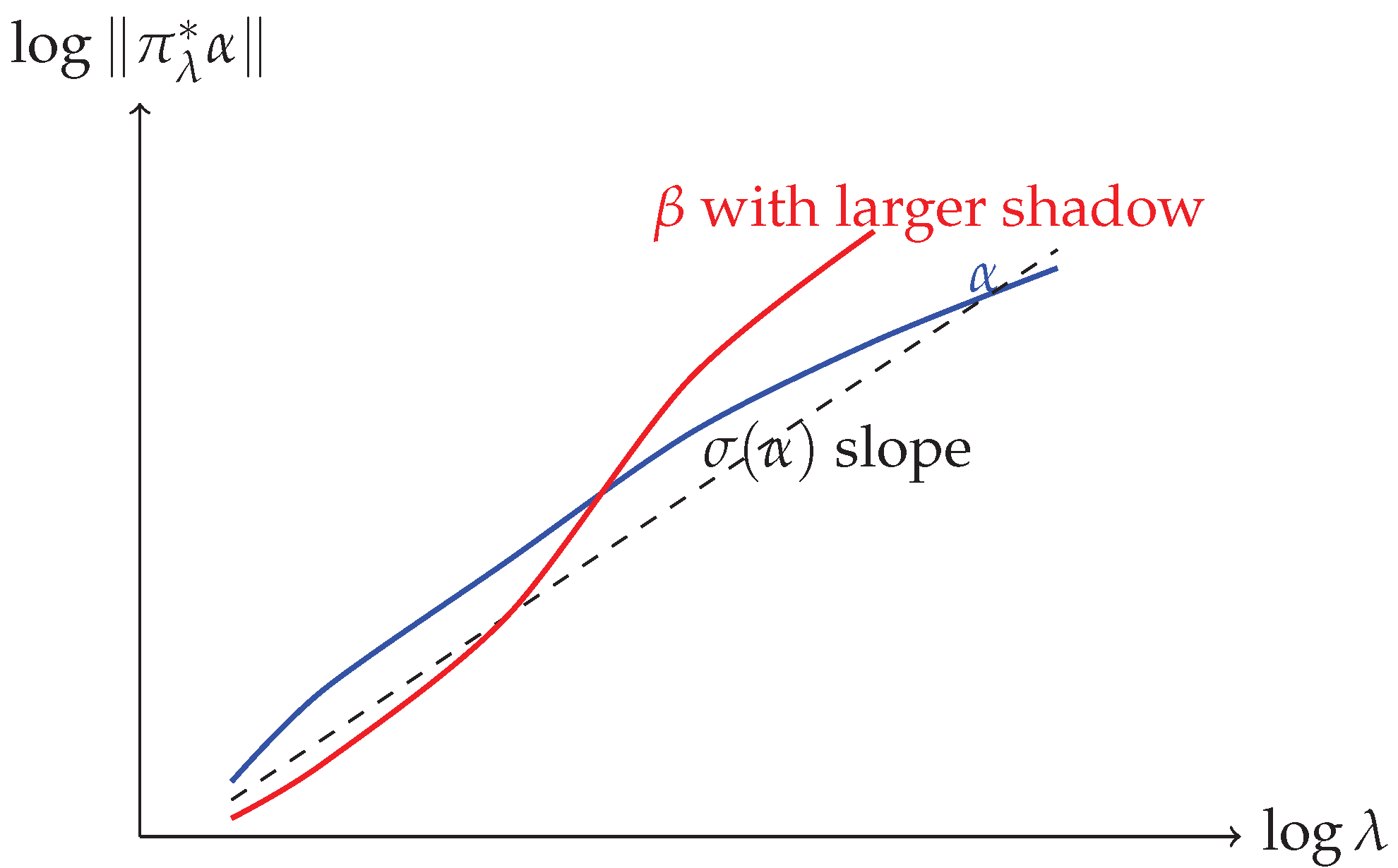

Appendix A. Schematic Figure

Figure A1.

Log-log shadow growth: principal slope encodes the shadow exponent, residual fluctuations encode tempered multifractality.

Figure A1.

Log-log shadow growth: principal slope encodes the shadow exponent, residual fluctuations encode tempered multifractality.

References

- L. Barreira, Dimension and Recurrence in Hyperbolic Dynamics, Birkhäuser, 2008.

- R. Bowen, Entropy for group endomorphisms and homogeneous spaces, Trans. AMS, 1971.

- G. Carlsson, Topology and data, Bull. AMS, 2009.

- K. Falconer, Fractal Geometry, Wiley, 1990.

- M. Gromov, Metric Structures for Riemannian and Non-Riemannian Spaces, Birkhäuser, 1999.

- A. Hatcher, Algebraic Topology, Cambridge Univ. Press, 2002.

- J. Kigami, Analysis on Fractals, Cambridge Univ. Press, 2001.

- J. Munkres, Elements of Algebraic Topology, Addison-Wesley, 1984.

- J. Roe, Coarse Cohomology and Index Theory, AMS, 1993.

- R. Strichartz, Differential Equations on Fractals, Princeton Univ. Press, 2006.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).