Submitted:

16 December 2025

Posted:

17 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

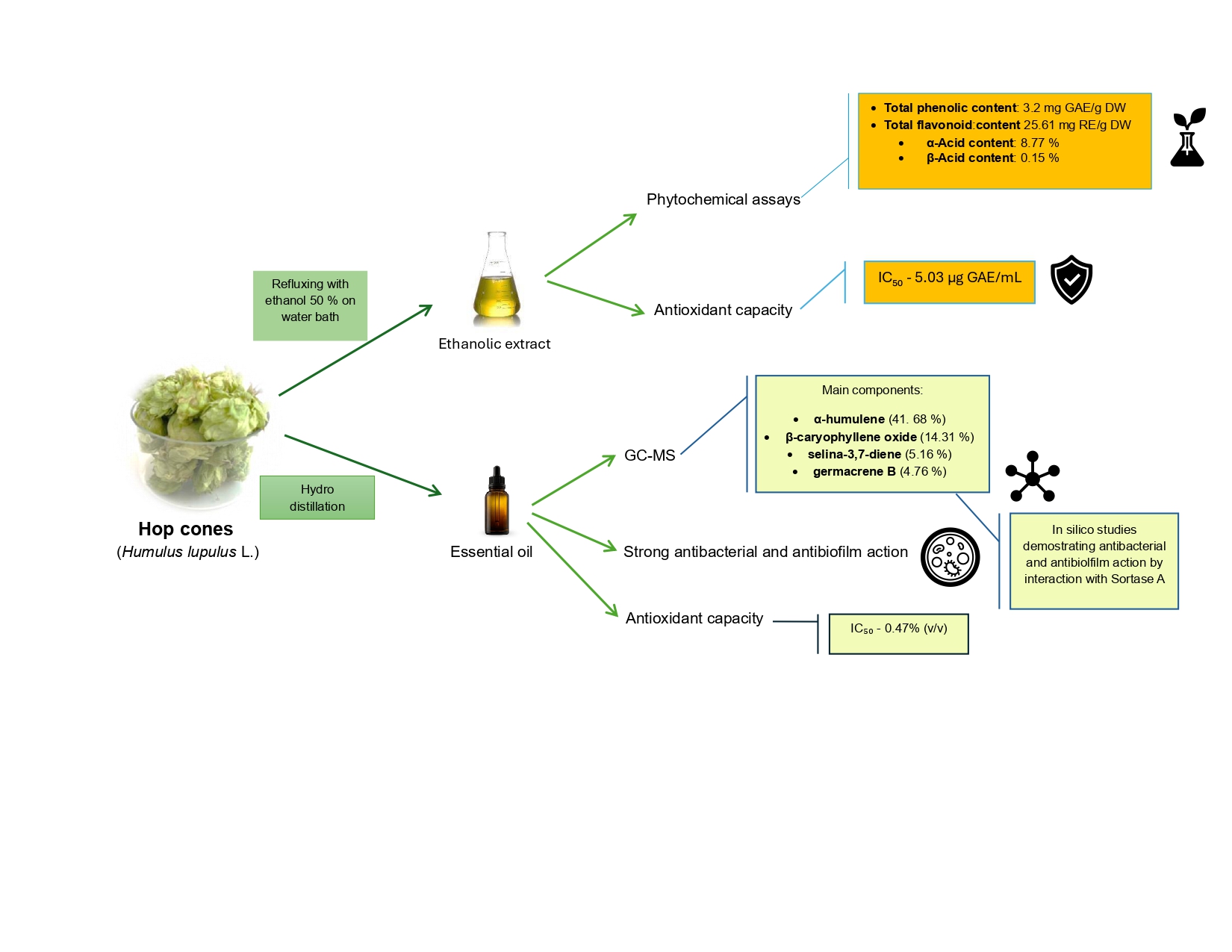

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Phytochemical Assays

2.2. Hydrodistillation and GC-MS Analysis of the Essential Oil

2.3. Biological Activity Determinations

2.3.1. Antioxidant Capacity

2.3.2. Antimicrobial and Antibiofilm Activity

2.3.3. Molecular Docking of Hop Essential Oil Constituents with Sortase A

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Chemicals

4.3. Phytochemical Assays

4.3.1. Total Phenolic Content

4.3.2. Total Flavonoid Content

4.3.3. Alpha and Beta Acids Content

4.4. Hydrodistillation and GC-MS Analysis of the Essential Oil

4.5. Biological Activity Determinations

4.5.1. Antioxidant Activity (DPPH Radical Scavenging Assay)

- Hydroethanolic hop extract

- Hop essential oil

4.5.2. Antimicrobial and Antibiofilm Activity

4.5.3. Molecular Docking of Hop Essential Oil Constituents with Sortase A

4.6. Statistical Data Processing

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Popescu, C.; Oprina-Pavelescu, M.; Dinu, V.; Cazacu, C.; Burdon, F.J.; Forio, M.A.E.; Kupilas, B.; Friberg, N.; Goethals, P.; McKie, B.G.; et al. Riparian Vegetation Structure Influences Terrestrial Invertebrate Communities in an Agricultural Landscape. Water 2021, 13, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haţieganu, E.; Gălăţanu, M.L. Botanică Farmaceutică. Sistematică Vegetală; Editura Hamangiu: Bucureşti, Romania, 2023; pp. 102–103. [Google Scholar]

- Min, B.; Ahn, Y.; Cho, H.J.; Kwak, W.K.; Jo, K.; Suh, H.J. Chemical Compositions and Sleep-Promoting Activities of Hop (Humulus lupulus L.) Varieties. J. Food Sci. 2023, 88, 2217–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodolfi, M.; Chiancone, B.; Liberatore, C.M.; Fabbri, A.; Cirlini, M.; Ganino, T. Changes in Chemical Profile of Cascade Hop Cones According to the Growing Area. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 6011–6019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langezaal, C.R.; Chandra, A.; Scheffer, J.J. Antimicrobial Screening of Essential Oils and Extracts of Some Humulus lupulus L. Cultivars. Planta Med. 1992, 58, 562–564. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanova, K.; Röderova, M.; Kolar, M.; Langova, K.; Dusek, M.; Jost, P.; Kubelkova, K.; Bostik, P.; Olsovska, J. Antibiofilm Activity of Bioactive Hop Compounds Humulone, Lupulone and Xanthohumol toward Susceptible and Resistant Staphylococci. Res. Microbiol. 2018, 169, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bravo, R.; Franco, L.; Rodríguez, A.B.; Ugartemendia, L.; Barriga, C.; Cubero, J. Tryptophan and Hops: Chrononutrition Tools to Improve Sleep/Wake Circadian Rhythms. Ann. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 1, 1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milligan, S.R.; Kalita, J.C.; Pocock, V.; Van De Kauter, V.; Stevens, J.F.; Deinzer, M.L.; et al. The Endocrine Activities of 8-Prenylnaringenin and Related Hop (Humulus lupulus L.) Flavonoids. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2000, 85, 4912–4915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, L.R.; Pauli, G.F.; Farnsworth, N.R. The Pharmacognosy of Humulus lupulus L. (Hops) with an Emphasis on Estrogenic Properties. Phytomedicine 2006, 13, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Hengzhuang, W.; Wu, H.; Damkiaer, S.; Jochumsen, N.; Song, Z.; Givskov, M.; Hoiby, N.; Molin, S. Polysaccharides Serve as Scaffold of Biofilms Formed by Mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2012, 65, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, D.C. Molecular Mechanism of Aspergillus fumigatus Adherence to Host Constituents. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2011, 14, 375–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Høiby, N.; Bjarnsholt, T.; Givskov, M.; Molin, S.; Ciofu, O. Antibiotic Resistance of Bacterial Biofilms. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2010, 35, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalska, G.; Bouchentouf, S.; Kowalski, R.; Wyrostek, J.; Pankiewicz, U.; Mazurek, A.; Włodarczyk-Stasiak, M. The Hop Cones (Humulus lupulus L.): Chemical Composition, Antioxidant Properties and Molecular Docking Simulations. J. Herb. Med. 2022, 33, 100566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, S.; Rodrigues, M.; Pinto, T.; Figueiredo, A.C.; Pedro, L.G. The Phenolic Composition of Hops (Humulus lupulus L.) and Their Antioxidant Capacity. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 385. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, J.I.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, S.Y. Comparative Study on Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activities of Hop (Humulus lupulus L.) Strobile Extracts. Plants 2022, 11, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanius, Ž.; Dūdėnas, M.; Kaškonienė, V.; Stankevičius, M.; Skrzydlewska, E.; Drevinskas, T.; Ragažinskienė, O.; Obelevičius, K.; Maruška, A. Analysis of the Leaves and Cones of Lithuanian Hops (Humulus lupulus L.) Varieties by Chromatographic and Spectrophotometric Methods. Molecules 2022, 27, 2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabino, B.C.C.; Bonfim, F.P.G.; Cabral, M.N.F.; Viriato, V.; Pak Campos, O.; Neves, C.S.; Fernandes, G.d.C.; Gomes, J.A.O.; Facanali, R.; Marques, M.O.M. Phytochemical Characterization of Humulus lupulus L. Varieties Cultivated in Brazil: Agricultural Zoning for the Crop in Tropical Areas. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leles, N.R.; Sato, A.J.; Rufato, L.; Jastrombek, J.M.; Marques, V.V.; Missio, R.F.; Fernandes, N.L.M.; Roberto, S.R. Performance of Hop Cultivars Grown with Artificial Lighting under Subtropical Conditions. Plants 2023, 12, 1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimczak, K.; Cioch-Skoneczny, M.; Duda-Chodak, A. Effects of Dry-Hopping on Beer Chemistry and Sensory Properties—A Review. Molecules 2023, 28, 6648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ano, Y.; Hoshi, A.; Ayabe, T.; Ohya, R.; Uchida, S.; Yamada, K.; Kondo, K.; Kitaoka, S.; Furuyashiki, T. Iso-α-Acids, the Bitter Components of Beer, Improve Hippocampus-Dependent Memory through Vagus Nerve Activation. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 4987–4995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ano, Y.; Kitaoka, S.; Ohya, R.; Kondo, K.; Furuyashiki, T. Hop Bitter Acids Increase Hippocampal Dopaminergic Activity in a Mouse Model of Social Defeat Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayabe, T.; Ohya, R.; Taniguchi, Y.; Shindo, K.; Kondo, K.; Ano, Y. Matured Hop-Derived Bitter Components in Beer Improve Hippocampus-Dependent Memory through Activation of the Vagus Nerve. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolenc, Z.; Langerholc, T.; Hostnik, G.; Ocvirk, M.; Štumpf, S.; Pintarič, M.; Košir, I.J.; Čerenak, A.; Garmut, A.; Bren, U. Antimicrobial Properties of Different Hop (Humulus lupulus) Genotypes. Plants 2022, 12, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takase, T.; Toyoda, T.; Kobayashi, N.; Inoue, T.; Ishijima, T.; Abe, K.; Kinoshita, H.; Tsuchiya, Y.; Okada, S. Dietary Iso-α-Acids Prevent Acetaldehyde-Induced Liver Injury through Nrf2-Mediated Gene Expression. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahli, A.; Thasler, W.E.; Biendl, M.; Hellerbrand, C. Hop-Derived Humulinones Reveal Protective Effects in In Vitro Models of Hepatic Steatosis, Inflammation and Fibrosis. Planta Med. 2023, 89, 1138–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saugspier, M.; Dorn, C.; Czech, B.; Gehrig, M.; Heilmann, J.; Hellerbrand, C. Hop Bitter Acids Inhibit Tumorigenicity of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells In Vitro. Oncol. Rep. 2012, 28, 1423–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paventi, G.; de Acutis, L.; De Cristofaro, A.; Pistillo, M.; Germinara, G.S.; Rotundo, G. Biological Activity of Humulus lupulus (L.) Essential Oil and Its Main Components Against Sitophilus granarius (L.). Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haunold, A.; Nickerson, G.B.; Likens, S.T. Yield and Quality Potential of Hop, Humulus lupulus L. J. Am. Soc. Brew. Chem. 1983, 41, 41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, H.I.; Rhee, K.J.; Eom, Y.B. Antibacterial and Antibiofilm Effects of α-Humulene Against Bacteroides fragilis. Can. J. Microbiol. 2020, 66, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Řebíčková, K.; Bajer, T.; Šilha, D.; Houdková, M.; Ventura, K.; Bajerová, P. Chemical Composition and Determination of the Antibacterial Activity of Essential Oils in Liquid and Vapor Phases Extracted from Two Different Southeast Asian Herbs—Houttuynia cordata (Saururaceae) and Persicaria odorata (Polygonaceae). Molecules 2020, 25, 2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, L.; Holtmann, D. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of α-Humulene on the Release of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines in Lipopolysaccharide-Induced THP-1 Cells. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2024, 82, 839–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, E.S.; Passos, G.F.; Medeiros, R.; da Cunha, F.M.; Ferreira, J.; Campos, M.M.; Pianowski, L.F.; Calixto, J.B. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Compounds α-Humulene and (-)-Trans-Caryophyllene Isolated from the Essential Oil of Cordia verbenacea. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2007, 569, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Yuan, J.; Hao, J.; Wen, Y.; Lv, Y.; Chen, L.; Yang, X. α-Humulene Inhibits Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cell Proliferation and Induces Apoptosis through the Inhibition of Akt Signaling. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 134, 110830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalavaye, N.; Nicholas, M.; Pillai, M.; Erridge, S.; Sodergren, M.H. The Clinical Translation of α-Humulene—A Scoping Review. Planta Med. 2024, 90, 664–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyres, G.T.; Marriott, P.J.; Dufour, J.-P. Comparison of Odor-Active Compounds in the Spicy Fraction of Hop (Humulus lupulus L.) Essential Oil from Four Different Varieties. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 6252–6261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahham, S.S.; Tabana, Y.M.; Iqbal, M.A.; et al. The Anticancer, Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Properties of the Sesquiterpene β-Caryophyllene from the Essential Oil of Aquilaria crassna. Molecules 2015, 20, 11808–11829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiu, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Han, J.; Li, Y.; Yang, X.; Yang, G.; Song, G.; Li, S.; Li, Y.; Cheng, C.; Li, Y.; Fang, J.; Li, X.; Jin, N. Caryophyllene Oxide Induces Ferritinophagy by Regulating the NCOA4/FTH1/LC3 Pathway in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 930958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, R.D.; Matos, B.N.; Freire, D.O.; da Silva, F.S.; do Prado, B.A.; Gomes, K.O.; de Araújo, M.O.; Bilac, C.A.; Rodrigues, L.F.S.; da Silva, I.C.R.; et al. Chemical Characterization and Antimicrobial Activity of Essential Oils and Nanoemulsions of Eugenia uniflora and Psidium guajava. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abram, V.; Čeh, B.; Vidmar, M.; Hercezi, M.; Lazić, N.; Bučik, V.; Smole Mozina, S.; Košir, I.J.; Kač, M.; Demšar, L.; Poklar Ulrih, N. A comparison of antioxidant and antimicrobial activity between hop leaves and hop cones. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 64, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, G.C.C.; da Silva, F.P.A.; Beirão, G.A.R.; Severino, J.J.; Machado, M.d.A.; Barbosa, M.P.d.S.B.; Reyes, G.B.; Rickli, M.E.; Lopes, A.D.; Jacomassi, E.; et al. Phytochemical Profile, Antioxidant Capacity, and Photoprotective Potential of Brazilian Humulus lupulus. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Żuk, N.; Pasieczna-Patkowska, S.; Grabias-Blicharz, E.; Pizoń, M.; Flieger, J. Purification of Spent Hop Cone (Humulus lupulus L.) Extract with Xanthohumol Using Mesoporous Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.C.E.; Costa, J.S.D.; Figueiredo, R.O.; Setzer, W.N.; Silva, J.K.R.D.; Maia, J.G.S.; Figueiredo, P.L.B. Monoterpenes and Sesquiterpenes of Essential Oils from Psidium Species and Their Biological Properties. Molecules 2021, 26, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel, M.G. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Essential Oils: A Short Review. Molecules 2010, 15, 9252–9287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, P.F.; do Nascimento, L.H.; Bandiera, V.J.; Fischer, B.; Fernandes, I.A.; Paroul, N.; Junges, A. Exploring the Versatility of Hop Essential Oil (Humulus lupulus L.): Bridging Brewing Traditions with Modern Industry Applications. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 218, 118974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volynets, G.; Vyshniakova, H.; Nitulescu, G.; Nitulescu, G.M.; Ungurianu, A.; Margina, D.; Moshynets, O.; Bdzhola, V.; Koleiev, I.; Iungin, O.; et al. Identification of Novel Antistaphylococcal Hit Compounds Targeting Sortase A. Molecules 2021, 26, 7095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Wang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Lanzi, G.; Wang, X.; Zhang, C.; Guan, J.; Wang, W.; Guo, X.; Meng, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhao, Y. Hibifolin, a Natural Sortase A Inhibitor, Attenuates the Pathogenicity of Staphylococcus aureus and Enhances the Antibacterial Activity of Cefotaxime. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, G.; Qu, H.; Wang, K.; Jing, S.; Guan, S.; Su, L.; Li, Q.; Wang, D. Taxifolin, an Inhibitor of Sortase A, Interferes with the Adhesion of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 686864. [Google Scholar]

- Mazmanian, S.K.; Liu, G.; Ton-That, H.; Schneewind, O. Staphylococcus aureus Sortase, an Enzyme That Anchors Surface Proteins to the Cell Wall. Science 1999, 285, 760–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suree, N.; Yi, S.W.; Thieu, W.; Marohn, M.; Damoiseaux, R.; Chan, A.; Jung, M.E.; Clubb, R.T. Discovery and Structure-Activity Relationship Analysis of Staphylococcus aureus Sortase A Inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 7174–7185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cascioferro, S.; Raffa, D.; Maggio, B.; Raimondi, M.V.; Schillaci, D.; Daidone, G. Sortase A Inhibitors: Recent Advances and Future Perspectives. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 9108–9123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulga, D.A.; Kudryavtsev, K.V. Ensemble Docking as a Tool for the Rational Design of Peptidomimetic Staphylococcus aureus Sortase A Inhibitors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thappeta, K.R.V.; Zhao, L.N.; Nge, C.E.; Crasta, S.; Leong, C.Y.; Ng, V.; Kanagasundaram, Y.; Fan, H.; Ng, S.B. In-Silico Identified New Natural Sortase A Inhibitors Disrupt Staphylococcus aureus Biofilm Formation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Choi, J.-H.; Lee, J.; Cho, E.; Lee, Y.-J.; Lee, H.-S.; Oh, K.-B. Halenaquinol Blocks Staphylococcal Protein A Anchoring on Cell Wall Surface by Inhibiting Sortase A in Staphylococcus aureus. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneewind, O.; Missiakas, D. Sortases, Surface Proteins, and Their Roles in Staphylococcus aureus Disease and Vaccine Development. Microbiol. Spectr. 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, G.D. Antibiotic adjuvants: Rescuing antibiotics from resistance. Trends Microbiol. 2016, 24, 862–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singleton, V.L.; Orthofer, R.; Lamuela-Raventos, R.M. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of Folin–Ciocalteau reagent. Methods Enzymol. 1999, 299, 152–178. [Google Scholar]

- Gălăţanu, M.L.; Panţuroiu, M.; Cima, L.M.; Neculai, A.M.; Pănuş, E.; Bleotu, C.; Enescu, C.M.; Mircioiu, I.; Gavriloaia, R.M.; Aurică, S.N.; Rîmbu, M.C.; Sandulovici, R.C. Polyphenolic Composition, Antioxidant Activity, and Cytotoxic Effect of Male Floral Buds from Three Populus Species Growing in the South of Romania. Molecules 2025, 30, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agentia Natională a Medicamentului. Farmacopeea Română; Editura Medicala: București, Romania, 1993; p. 335.

- Panţuroiu, M.; Gălăţanu, M.L.; Manea, C.E.; Popescu, M.; Sandulovici, R.C.; Pănuş, E. From Chemical Composition to Biological Activity: Phytochemical, Antioxidant, and Antimicrobial Comparison of Matricaria chamomilla and Tripleurospermum inodorum. Compounds 2025, 5, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines HealthCare of the Council of Europe. European Pharmacopoeia, 10th ed.; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2019; Volume I. Available online: https://www.edqm.eu/en/european-pharmacopoeia-ph.-eur.-11th-edition (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Ovidi, E.; Laghezza Masci, V.; Taddei, A.R.; Torresi, J.; Tomassi, W.; Iannone, M.; Tiezzi, A.; Maggi, F.; Garzoli, S. Hemp (Cannabis sativa L., Kompolti cv.) and Hop (Humulus lupulus L., Chinook cv.) Essential Oil and Hydrolate: HS-GC-MS Chemical Investigation and Apoptotic Activity Evaluation. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panţuroiu, M.; Gălăţanu, M.L.; Cristache, R.E.; Truţă, E. Characterisation of nutraceutical fatty acids and amino acids in the buds of Populus nigra, Populus alba, and Populus × euramericana by gas chromatography. J. Sci. Arts 2025, 25, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rîmbu, M.C.; Cord, D.; Savin, M.; Grigoroiu, A.; Mihăilă, M.A.; Gălățanu, M.L.; Ordeanu, V.; Panțuroiu, M.; Țucureanu, V.; Mihalache, I.; et al. Harnessing Plant-Based Nanoparticles for Targeted Therapy: A Green Approach to Cancer and Bacterial Infections. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danet, A.F. Recent advances in antioxidant capacity assays. In Antioxidants-Benefits, Sources, Mechanisms of Action; Waisundara, V., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk and Dilution Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria Isolated from Animals, 4th ed.; CLSI Supplement VET08; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cermelli, C.; Fabio, A.; Fabio, G.; Quaglio, P. Effect of Eucalyptus Essential Oil on Respiratory Bacteria and Viruses. Curr. Microbiol. 2008, 56, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the Speed and Accuracy of Docking with a New Scoring Function, Efficient Optimization, and Multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forli, S.; Huey, R.; Pique, M.E.; Sanner, M.F.; Goodsell, D.S.; Olson, A.J. Computational Protein–Ligand Docking and Virtual Drug Screening with the AutoDock Suite. Nat. Protoc. 2016, 11, 905–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagadala, N.S.; Syed, K.; Tuszynski, J. Software for Molecular Docking: A Review. Biophys. Rev. 2017, 9, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| TPC (mg GAE/g DW) |

TFC (mg RE/g DW) |

α-Acid content % |

β-Acid content % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3.20 ± 0.05 | 25.61 ± 0.02 | 8.77.00 ± 0.007 | 0.15 ± 0.003 |

| No. | Compound | Retention Time (min) | Area (min) | Area [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Myrcene | 11.245 | 1152299.825 | 3.05 |

| 2 | Nonaldehyde | 21.819 | 875454.647 | 2.32 |

| 3 | 2-Methyl-hexadecanal | 27.094 | 205137.635 | 0.54 |

| 4 | β-Caryophyllene oxide | 28.053 | 5399268.552 | 14.31 |

| 5 | Azulene | 28.346 | 521386.068 | 1.38 |

| 6 | 2-Undecanone | 28.570 | 1133910.205 | 3.00 |

| 7 | 4-Methyl-decenoate | 29.410 | 512483.171 | 1.36 |

| 8 | α-Humulene | 30.216 | 15731415.243 | 41.68 |

| 9 | Muurolene | 30.883 | 536717.160 | 1.42 |

| 10 | β-Patchoulene | 31.039 | 430720.443 | 1.14 |

| 11 | Eudesma-4,7(14)-11-diene | 31.614 | 1405668.726 | 3.72 |

| 12 | γ-Gurjunene | 31.791 | 1329138.104 | 3.52 |

| 13 | Cadina-1,4-diene | 32.852 | 1209856.356 | 3.21 |

| 14 | Selina-3,7-diene | 33.298 | 1947271.467 | 5.16 |

| 15 | 2-Tridecanone | 34.526 | 488920.421 | 1.30 |

| 16 | Germacrene B | 34.614 | 1796923.960 | 4.76 |

| 17 | Caryophyllene oxide | 38.501 | 186057.967 | 0.49 |

| 18 | 3-Cyclohexen-carboxaldehyde | 39.896 | 479370.854 | 1.27 |

| 19 | Globulol | 40.920 | 191539.36 | 0.51 |

| 20 | Nonadecatriene | 41.192 | 727835.740 | 1.93 |

| 21 | 1-H-Indene | 41.896 | 257795.907 | 0.68 |

| 22 | Methyl 4,7,10,13-hexadecatetraenoate | 42.749 | 191654.129 | 0.51 |

| 23 | α-Eudesmol | 44.276 | 469586.395 | 1.24 |

| 24 | β-Eudesmol | 44.447 | 400628.367 | 1.06 |

| 25 | Neointermedeol | 44.960 | 158055.457 | 0.42 |

| Total: | 37739095.263 | 100 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).