Flaviviruses: Emerging Global Health Threats

Flaviviruses are a diverse family of insect-borne (+) RNA viruses, many of which pose significant global health concerns[

1]. The

Orthoflavivirus genus contains 53 documented species[

2] that infect a range of mammals, birds, or other vertebrates, typically transmitted by bites of infected mosquitos or ticks. Major human pathogens include Dengue virus (DENV), Zika virus (ZIKV), West Nile virus (WNV), Yellow Fever virus (YFV), and tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV), all recently classified by the World Health Organization as high risk for pandemic potential[

3]. These flaviviruses are endemic to tropical regions around the world, and their geographic ranges are expected to expand as insect migration patterns shift with climate change[

4]. Other emerging or re-emerging pathogens include Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV), Usutu virus (USUV), Spondweni virus (SPOV), Powassan virus (POWV), and others[

1,

5]. Although most flavivirus infections are asymptomatic or cause a self-limiting flu-like illness, severe infections can cause life-threatening pathologies such as hepatitis, vascular shock syndrome, haemorrhagic fever, paralysis, myocarditis, and encephalitis[

1,

6]. Effective vaccines are available for YFV, TBEV, and JEV[

7], and a partially effective vaccine for DENV[

8]. Otherwise, there are no specific preventions or treatments for any flavivirus and limited diagnostic tools. A better molecular understanding of flavivirus pathogenesis is needed to identify new diagnostic, preventative, and therapeutic approaches.

Like all viruses, flaviviruses are fully dependent upon their host cells for nutrients and structural support during replication. Although most studies of flavivirus-relevant host factors have focused on proteins, the roles of host lipids are becoming increasingly apparent. Innovative tools now enable study of lipids in mechanistic detail, including advances in cryo-electron tomography (cryo-ET) visualization, mass spectrometry-based lipidomics, and functionalized lipid probes, paving the way for powerful investigations of lipid function in infection. In this review, we will summarize recent insights into flavivirus-lipid interactions, including emerging roles of lipids in different stages of the viral life cycle and novel mechanisms of flavivirus-driven lipid dysregulation. Finally, we will offer our perspective on the evolution of the field of virus-host lipid biology, highlighting recent technical advances that open highly promising avenues of study.

Lipids in the Flavivirus Life Cycle

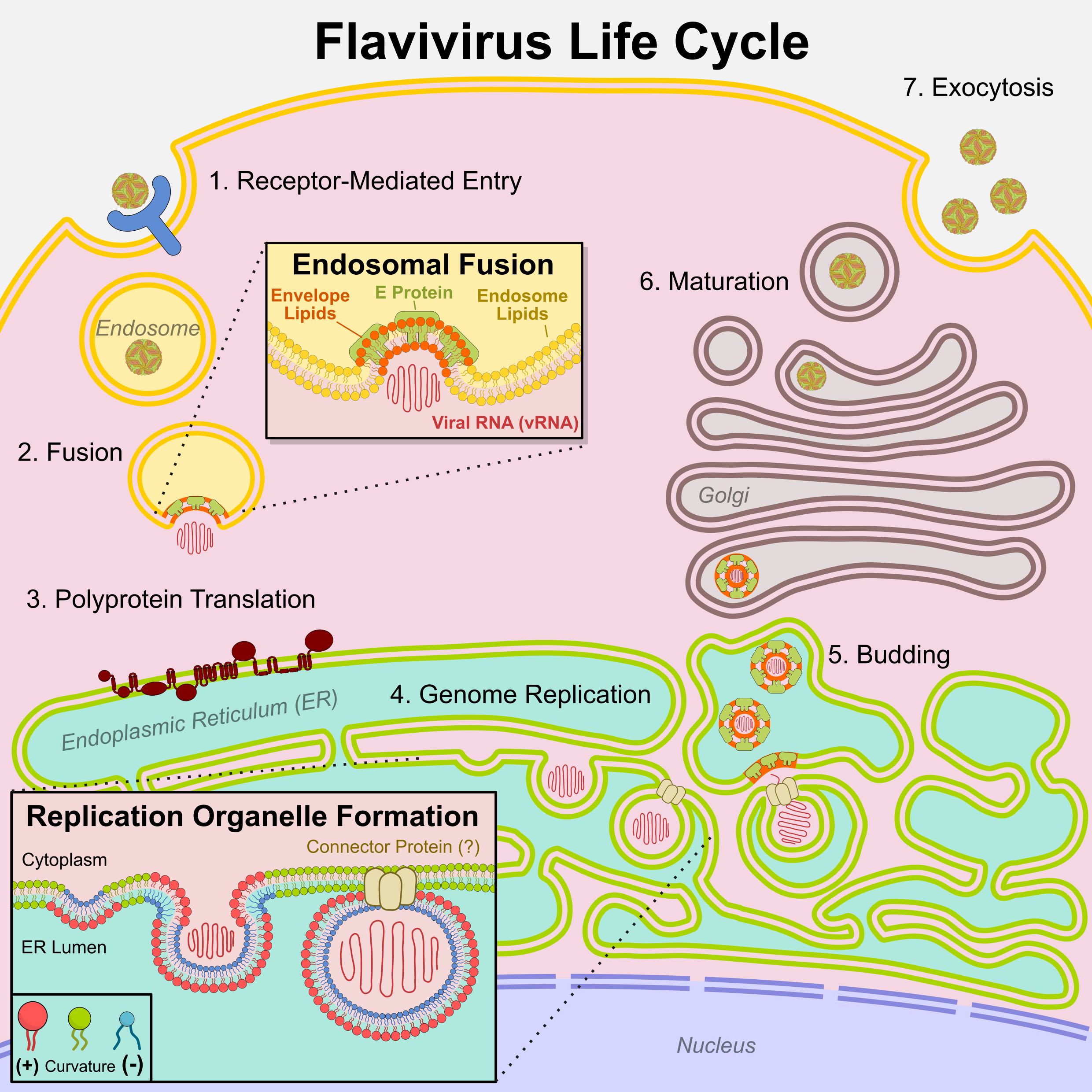

Flaviviruses interact with host membranes at every stage of their life cycle (

Figure 1). Some of the earliest ultrastructural studies of flavivirus-infected cells revealed distinct virus-induced membrane rearrangements[

9,

10], including specialized endoplasmic reticulum (ER) compartments now known as replication organelles (ROs)[

11,

12]. Landmark studies in the 2000-2010s revealed that lipid metabolic enzymes, including fatty acid[

13,

14] and cholesterol[

15,

16] biosynthesis enzymes, are recruited to ROs and are indispensable for flavivirus replication. More recently, lipidomic studies have repeatedly showed that flavivirus infection dysregulates the levels of many different lipid classes in both mosquito[

17,

18] and mammalian[

19,

20] cells, most consistently affecting sphingolipids such as ceramide. Unlike viral proteins, the flavivirus lipid envelope is not virally encoded but is acquired from host cells, underscoring the dependence on host lipids. Despite these observations, the mechanistic roles of individual lipids in the viral life cycle have remained elusive.

Human cells contain hundreds of lipid species with diverse structural and signaling functions[

21]. Cellular lipids fall into three major classes: glycerolipids (the most abundant membrane lipids), sterols (rigid lipids influencing membrane fluidity and organization), and sphingolipids (under-studied lipids with emerging signaling roles, including ceramide and derivatives[

22]). Lipids are highly compartmentalized; each organelle maintains a distinct lipid composition on its inner and outer membrane leaflets, with localized variations giving rise to membrane sub-domains[

21,

23]. Each membrane’s lipid composition defines properties such as fluidity, curvature, thickness, and surface charge, which influence protein localization, conformation, and activity[

23]. Lipid composition is controlled in turn by transport and enzymatic activity, creating dynamic lipid-protein signaling networks that orchestrate many cellular functions. While the biosynthesis and general properties of each lipid class have been well described, the specific roles and interactions of most individual lipid species, which vary by backbone, headgroup, acyl chain length, and saturation level, have yet to be determined. Identifying how and why flaviviruses redirect host lipids could reveal new therapeutic strategies as well as broader roles of individual lipids in cell health.

Flavivirus Entry

Flaviviruses contain a host-derived lipid envelope which directly interacts with the three structural proteins E, M, and C (

Figure 2a). Emerging evidence suggests that envelope lipid composition affects both receptor binding and fusion. A plethora of different entry receptors have been identified for flaviviruses, including phosphatidylserine (PS) receptors such as those in the Tyro3/Axl/Mer (TAM) family[

24]. PS is a glycerophospholipid that resides in the plasma membrane inner leaflet and is typically only exposed on the outer leaflet during apoptosis. Many enveloped viruses contain surface-exposed PS in their membranes and utilize PS receptors through “apoptotic mimicry”[

25]. Supporting this model, a lipidomic study of TBEV virions[

26] reported PS enrichment in the viral envelope. In another study, PS-enriched extracellular vesicles were found to competitively inhibit ZIKV entry as well as other enveloped RNA viruses[

27]. Furthermore, a CRISPR screen in placental trophoblasts identified hepatitis A virus cellular receptor 1 (HAVCR1), another PS receptor, as a key ZIKV entry factor required for vertical (mother-to-fetus) transmission[

28]. HAVCR1-mediated viral entry required an intact PS-binding pocket, suggesting direct binding to viral envelope PS. Blocking interactions between PS and its receptors could be a promising therapeutic approach for flaviviruses and other enveloped viruses.

Additionally, some lipids themselves may function as entry receptors or cofactors, particularly glycosylated lipids. Tantirimudalige et al. found that direct interaction between DENV E protein and the glycosphingolipid GM1a enhances initial viral attachment and speeds up viral movement on cell surfaces[

29]. Notably, inhibitors of glycosphingolipid synthesis block replication of both DENV and ZIKV[

30]. In addition to the plasma membrane, glycosphingolipids are found throughout the secretory pathway including in the Golgi[

22] and may play multiple roles in the viral life cycle.

Following receptor-mediated endocytosis, flaviviruses fuse with late endosomes, at which point the viral envelope and endosomal membrane are merged (

Figure 1 inset). Interactions between flavivirus structural proteins and envelope lipids may promote fusion. Specific lipid interactions have been identified for some flavivirus proteins, particularly the E and M proteins. Recent cryo-EM structures of E protein from ZIKV[

31], DENV[

32], TBEV[

33], and SPOV[

34] have revealed a highly conserved phospholipid, most likely phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) or phosphatidylcholine (PC), coordinated by a conserved His in the E protein amphipathic helices which lay flat along the lipid envelope. All tested flaviviruses were highly sensitive to mutation of this His residue (ZIKV H446, DENV H437, TBEV H438, or SPOV H447), suggesting phospholipid binding at this site is essential for flavivirus infection. Other essential lipid binding pockets have been identified within E amphipathic helices[

32,

33] or E and M transmembrane stem helices[

31], although the identity of bound ligands and their conservation among flaviviruses remains unclear. E undergoes significant conformational changes during flavivirus maturation as well as membrane fusion, and lipid binding likely plays a role in both rearrangements. Molecular dynamics simulations of various flavivirus E proteins with lipids predicted that envelope phospholipids pack into an unusually confined space, generating elastic tension that could promote E protein rearrangements during fusion[

35]. Additional molecular dynamics simulations predict that DENV E preferentially binds negatively charged phospholipids that are enriched in the late endosomal membrane, including phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate (PI3P) and bis(monoacylglycero)phosphate (BMGP)[

36], which could help facilitate fusion.

Two cholesterol binding sites in the Zika virus prM protein (M in the mature virus) were recently identified by Goellner et al., one of which was shown to be essential for endosomal fusion, and the other for virion assembly[

37]. Notably, mutation of these cholesterol-binding sites only affected viral fitness in mammalian cells and had no effect in mosquito cells (which contain much lower cholesterol levels), suggesting that flavivirus lipid usage can differ across host species. Overall, these recent findings demonstrate how structural proteins E and prM/M directly interface with lipids during the earliest steps of viral pathogenesis.

Figure 2.

Flavivirus protein-lipid interactions. A) Flavivirus virion outer view and cross-section. Structural proteins E, M, and C scaffold a host-derived lipid envelope surrounding viral genomic RNA. B) Flavivirus polyprotein topology diagram showing transmembrane and membrane-interacting domains of structural and non-structural proteins (not to scale).

Figure 2.

Flavivirus protein-lipid interactions. A) Flavivirus virion outer view and cross-section. Structural proteins E, M, and C scaffold a host-derived lipid envelope surrounding viral genomic RNA. B) Flavivirus polyprotein topology diagram showing transmembrane and membrane-interacting domains of structural and non-structural proteins (not to scale).

Flavivirus Translation and Replication

Flavivirus RNA is translated at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) into a transmembrane polyprotein that is cleaved into 3 structural and 7 non-structural proteins (

Figure 2b). Structural proteins E and prM are transmembrane and interact closely with host lipids, as described earlier. The capsid (C) protein directly contacts the host cell membrane and, in virions, bridges contacts between viral RNA and the host-derived lipid envelope[

38,

39], playing an important role in viral particle assembly (

Figure 2a). Of the non-structural proteins, the majority (NS2A, NS2B, NS4A, NS4B, and the short 2K peptide) are transmembrane and directly interface with host lipids, although their specific lipid interactors have not been determined. NS1 forms a membrane-associated dimer inside cells or can be secreted as an oligomer surrounding a lipid cargo enriched in triglycerides, cholesterol, and phospholipids[

40,

41]. The secreted NS1 lipoprotein causes vascular leakage associated with severe flavivirus disease and activates multiple inflammatory pathways[

41,

42]. The viral protease (NS3) and RNA polymerase (NS5) are not directly membrane-associated, but both proteins have been shown to interact with several lipid-remodeling enzymes to indirectly alter cellular lipid metabolism (described in the next section). Altogether, interplay with host lipids is a common theme among all flavivirus proteins.

The ER is the primary site of lipid biosynthesis, and flavivirus proteins reshape ER lipid metabolism and membrane architecture to facilitate replication. All flaviviruses induce replication organelles (ROs), specialized membrane compartments derived from the ER widely accepted as the primary sites of genome replication. High resolution electron microscopy has revealed the intricate architecture of these ROs[

43,

44,

45], which include double-membrane vesicles, convoluted ER membranes, and extensive cytoskeletal reorganization. Several flavivirus proteins including NS1, NS2A, NS4A, and NS4B play key roles in RO formation[

46], but the host factors contributing to RO biogenesis are incompletely understood. The inward budding of ROs requires a high degree of both positive and negative membrane curvature (

Figure 1 inset). Other cellular processes involving similar curvature, such as phagocytosis or autophagy, typically require cone-shaped lipids such as phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) or inverted-cone-shaped lipids such as ceramide (Cer) that spontaneously form curved membranes[

21] . Enrichment of curvature-inducing lipids on the inner or outer leaflet typically requires the activity of lipid transport enzymes (flippases, floppases, and scramblases)[

48]. A notable exception is Cer, which can freely diffuse between leaflets[

49], possibly explaining its role in promoting phagocytosis[

47]. The lipids required for RO formation have yet to be conclusively determined.

Recent advances in cryo-ET have increased the level of detail attainable in RO reconstructions, enabling further insight into RO formation and function. For instance, Dahmane et al. applied cryo-ET to study Langat virus (LGTV, a close relative of TBEV) in human lung cells and mouse brain tissue[

50]. Using a novel computational tool to map relative membrane thickness[

51], they found RO vesicles to be consistently thicker than the surrounding ER, enabling identification of empty ROs absent of any viral RNA. These results support a mechanism in which RO vesicles are generated and stabilized by proteins (likely viral non-structural proteins) rather than internal pressure from replicating RNA[

50]. Moreover, they observed a putative protein complex spanning a section of ER that bridges ROs with budding virions, suggesting close spatial coordination between genome replication and virion assembly[

50]. While the identity of the connector protein is unknown, its structure appears similar to pore-forming proteins reported for other RNA viruses[

52].Additional insights into flavivirus lipid requirements have been obtained through mass spectrometry-based lipidomics of flavivirus-infected cells. In our study of ZIKV infection in human cells[

19], we observed broad dysregulation across nearly all lipid categories, with the most striking differences observed in ceramide, the central member of the sphingolipid family. Sphingolipid biosynthesis inhibitors blocked ZIKV replication, suggesting a dependency on ceramide or its downstream metabolites. In other studies, inhibitors against other ceramide-producing enzymes including neutral sphingomyelinase[

53] and dihydroceramide desaturase[

54] also demonstrate broad anti-flavivirus activity. The mechanistic role of ceramide in viral replication has yet to be determined, but parallels to other cellular processes would suggest roles in promoting membrane curvature[

47] or signaling cell death or differentiation[

22].

Further supporting the role of sphingolipids in infection, a lipidomic analysis of WNV-infected mice and clinical patients by Mingo-Casas et al. revealed elevated levels of circulating sphingolipids, including ceramide, dihydroceramide, and dihydrosphingomyelin[

55]. These results not only suggest conserved pathogenic mechanisms across host species but also point toward lipid-based diagnostic biomarkers. Moreover, lipidomic studies of DENV-infected mosquitos by Elliott et al. revealed upregulation of ceramide and sphingomyelin as well as several species of glycerolipids[

56], suggesting conserved virus-lipid interactions across insect and mammalian hosts.

A more extensive lipidomics analysis by Hehner et al. compared multiple flaviviruses (ZIKV, DENV, WNV, YFV, and TBEV) in human liver cells[

20]. The study identified consistent patterns across infections, including general depletion of phospholipids (PC, PE, and PS), elevation of pro-inflammatory lyso-phospholipids, enrichment of long-chain and polyunsaturated fatty acids in multiple lipid classes, and ceramide accumulation at late timepoints. Subsequently, the same group found that DENV replication depends on fatty acid elongation (via ELOVL4) and desaturation (via FADS2) at post-entry steps[

57]. Altogether, lipidomic analysis of flavivirus infection has shed light on conserved lipid requirements during replication. Further study is needed to determine the precise mechanistic roles of different lipid species and lipid-remodeling proteins.

Flavivirus Egress

After translation and genome replication in the RO, virions assemble and bud into the ER lumen, acquiring their lipid envelope from the modified host ER membrane. Virions are shuttled to the Golgi, matured through prM protein cleavage, and ultimately released at the cell surface[

1]. The host factors involved in flavivirus egress are largely unknown. Flaviviruses were long assumed to hijack components of the classical secretory pathway (i.e., exocytosis)[

58] but have recently been linked to additional routes including exosome[

59,

60] and secretory autophagy[

61,

62,

63] pathways.

Exosomes are a type of extracellular vesicle that form within multivesicular endosomes and transport nucleic acids, lipids, and proteins between cells[

64]. Exosomes are similar in size and structure to enveloped viruses, and exosomes derived from virus-infected cells, including flaviviruses, often contain viral RNA and proteins[

59]. A recent study found that exosomes can package DENV and JEV sub-genomic RNA, encoding a subset of viral proteins and replicating without producing infectious virus, and that these exosomes are infectious[

60]. Given the parallels between exosomes and flaviviruses, lipid regulators of exosome biogenesis may also contribute to flavivirus egress. Exosomes are typically enriched in sphingomyelin, glycosphingolipids, and cholesterol, and their formation is regulated by these and many other lipids[

64].

Secretory autophagy is a recently discovered form of autophagy in which autophagosomes bypass lysosomal degradation and are instead released at the cell surface as extracellular vesicles. Flaviviruses hijack many autophagy-related proteins for membrane remodeling and immune evasion[

65], and it has recently been shown that ZIKV and DENV depend on secretory autophagy proteins such as Lyn kinase[

61]. Furthermore, DENV genomic RNA can be detected in secreted autophagosomes in multiple cell types[

62,

63]. While lipid regulation of secretory autophagy has not been studied, normal autophagy is regulated by many lipids[

66], including some fatty acids and sphingolipids that are upregulated during flavivirus infection[

19]. It is unclear to what extent these lipids contribute to flavivirus secretion. Overall, flaviviruses may utilize components of multiple secretory pathways, and the mechanism of egress remains one of the largest knowledge gaps in the flavivirus life cycle.

Concluding Remarks and Future Perspectives

Altogether, the synergy between advanced imaging, lipidomics, chemical biology, and many other biophysical and computational techniques is transforming our understanding of how flaviviruses exploit host lipids. Lipids are far more than passive structural components in the viral life cycle; they are dynamic regulators of replication organelle formation, virion assembly and egress, and other host-pathogen interactions. Across this review, we have highlighted recent methodological breakthroughs that unlock new ways to understand lipid roles in the viral life cycle.

A significant area of controversy in the field centers around the origin and functional significance of lipid dysregulation during infection. It is difficult to determine from lipidomic observations, for example, whether a given lipid change is primarily driven by viral proteins or by innate cellular defenses such as the interferon response. Likewise, it remains unclear whether many individual lipid species ultimately promote or suppress infection. These relationships can be clarified by manipulating individual viral proteins and the host lipid-remodeling machinery, as demonstrated by several studies covered in this review. Whether a given lipid serves a pro- or anti-viral function likely depends on both the timing and subcellular location of lipid perturbations, and studying these lipid dynamics will require tools capable of manipulating and observing lipids with high spatiotemporal resolution. Clarifying the causal mechanisms and downstream effects of lipid perturbations will greatly aid in the development of therapeutic strategies targeting specific lipid pathways.

A second major area of uncertainty involves the extent to which lipid perturbations are conserved across viral species and host cellular contexts. Most virus-lipid interactions have been characterized in immortalized cell lines, and it is not yet known how these findings translate to infection in native cellular contexts. Comparative studies across diverse flaviviruses and cell types are one possibility for addressing this knowledge gap, but such studies are resource-intensive and low-throughput. Expanding investigations into more physiologically representative systems, including organoids and primary cells, may help clarify which lipid dependencies are universal or context-specific.

Looking ahead, several directions appear especially promising. The development of new chemical tools, particularly functionalized versions of fatty acids, sphingolipids, and glycerolipids with a range of chain length and saturation levels, would allow direct analysis of the specific species elevated in flavivirus infections and identification of their protein partners. To build upon foundational discoveries of lipid function in infection, comparative studies across flavivirus species and host cell types could reveal which lipid dependencies are conserved or species-specific. Additionally, lipidomics of pure flaviviruses is a promising approach to identify lipid requirements, but definitive analysis will require technical improvements to purify flaviviruses away from extracellular vesicles of similar size and composition. On the computational front, integrating lipid data into existing tools could yield powerful insights into local lipid composition in cryo-ET imaging, or predictions of protein folding and activity in different lipid environments. Due to the enormous complexity of the lipid world, where minute structural differences across lipid species can impart widely different biophysical properties, these computations will require novel artificial intelligence approaches. Continued innovation in lipid science will not only clarify the molecular choreography of flavivirus infection, but will also guide the design of lipid-targeted therapies and diagnostics with broad relevance to human health.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by NIH NIAID grant R01 AI141549 (F. G. T. and C. S.), NIH NIGMS R01 GM127631 and R35 GM158174 (C. S.), and NIH NIGMS K12 GM150451 (J. L. E.). C. S. is a founder of Molecular Tools Inc.; F. G. T. is a founder of AlpaCure LLC; J. L. E. declares no competing interests.

References

- Pierson, T.C. and Diamond, M.S. (2020) The continued threat of emerging flaviviruses. Nat Microbiol 5, 796-812. [CrossRef]

- Simmonds, P., et al. (2017) ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Flaviviridae. J Gen Virol 98, 2-3. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (2024) Pathogens prioritization: a scientific framework for epidemic and pandemic research preparedness. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/pathogens-prioritization-a-scientific-framework-for-epidemic-and-pandemic-research-preparedness.

- Naslund, J., et al. (2021) Emerging Mosquito-Borne Viruses Linked to Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus: Global Status and Preventive Strategies. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 21, 731-746. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, A.N. and Ploss, A. (2024) Emerging mosquito-borne flaviviruses. mBio 15, e0294624. [CrossRef]

- van Leur, S.W., et al. (2021) Pathogenesis and virulence of flavivirus infections. Virulence 12, 2814-2838.

- Madere, F.S., et al. (2025) Flavivirus infections and diagnostic challenges for dengue, West Nile and Zika Viruses. npj Viruses 3, 36. [CrossRef]

- Foucambert, P., et al. (2022) Efficacy of Dengue Vaccines in the Prevention of Severe Dengue in Children: A Systematic Review. Cureus 14, e28916. [CrossRef]

- Filshie, B.K. and Rehacek, J. (1968) Studies of the morphology of Murray Valley encephalitis and Japanese encephalitis viruses growing in cultured mosquito cells. Virology 34, 435-443. [CrossRef]

- Stohlman, S.A., et al. (1975) Dengue virus-induced modifications of host cell membranes. J Virol 16, 1017-1026. [CrossRef]

- Neufeldt, C.J., et al. (2018) Rewiring cellular networks by members of the Flaviviridae family. Nat Rev Microbiol 16, 125-142. [CrossRef]

- Ci, Y. and Shi, L. (2021) Compartmentalized replication organelle of flavivirus at the ER and the factors involved. Cell Mol Life Sci 78, 4939-4954. [CrossRef]

- Heaton, N.S., et al. (2010) Dengue virus nonstructural protein 3 redistributes fatty acid synthase to sites of viral replication and increases cellular fatty acid synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107, 17345-17350. [CrossRef]

- Martin-Acebes, M.A., et al. (2011) West Nile virus replication requires fatty acid synthesis but is independent on phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate lipids. PLoS One 6, e24970. [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, J.M., et al. (2007) Cholesterol manipulation by West Nile virus perturbs the cellular immune response. Cell Host Microbe 2, 229-239. [CrossRef]

- Rothwell, C., et al. (2009) Cholesterol biosynthesis modulation regulates dengue viral replication. Virology 389, 8-19. [CrossRef]

- Perera, R., et al. (2012) Dengue virus infection perturbs lipid homeostasis in infected mosquito cells. PLoS Pathog 8, e1002584. [CrossRef]

- Melo, C.F., et al. (2016) A Lipidomics Approach in the Characterization of Zika-Infected Mosquito Cells: Potential Targets for Breaking the Transmission Cycle. PLoS One 11, e0164377. [CrossRef]

- Leier, H.C., et al. (2020) A global lipid map defines a network essential for Zika virus replication. Nat Commun 11, 3652. [CrossRef]

- Hehner, J., et al. (2024) Glycerophospholipid remodeling is critical for orthoflavivirus infection. Nat Commun 15, 8683. [CrossRef]

- Harayama, T. and Riezman, H. (2018) Understanding the diversity of membrane lipid composition. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 19, 281-296.

- Hannun, Y.A. and Obeid, L.M. (2018) Sphingolipids and their metabolism in physiology and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 19, 175-191. [CrossRef]

- Levental, I. and Lyman, E. (2023) Regulation of membrane protein structure and function by their lipid nano-environment. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 24, 107-122. [CrossRef]

- Anwar, M.N., et al. (2022) The interactions of flaviviruses with cellular receptors: Implications for virus entry. Virology 568, 77-85. [CrossRef]

- Bohan, D. and Maury, W. (2021) Enveloped RNA virus utilization of phosphatidylserine receptors: Advantages of exploiting a conserved, widely available mechanism of entry. PLoS Pathog 17, e1009899. [CrossRef]

- Pulkkinen, L.I.A., et al. (2023) Simultaneous membrane and RNA binding by tick-borne encephalitis virus capsid protein. PLoS Pathog 19, e1011125. [CrossRef]

- Gross, R., et al. (2024) Phosphatidylserine-exposing extracellular vesicles in body fluids are an innate defence against apoptotic mimicry viral pathogens. Nat Microbiol 9, 905-921.

- Yu, W., et al. (2025) The HAVCR1-centric host factor network drives Zika virus vertical transmission. Cell Rep 44, 115464. [CrossRef]

- Tantirimudalige, S.N., et al. (2022) The ganglioside GM1a functions as a coreceptor/attachment factor for dengue virus during infection. J Biol Chem 298, 102570. [CrossRef]

- Konan, K.V., et al. (2022) Modulation of Zika virus replication via glycosphingolipids. Virology 572, 17-27. [CrossRef]

- DiNunno, N.M., et al. (2020) Identification of a pocket factor that is critical to Zika virus assembly. Nat Commun 11, 4953. [CrossRef]

- Hardy, J.M., et al. (2021) A unified route for flavivirus structures uncovers essential pocket factors conserved across pathogenic viruses. Nat Commun 12, 3266. [CrossRef]

- Pulkkinen, L.I.A., et al. (2022) Molecular Organisation of Tick-Borne Encephalitis Virus. Viruses 14. [CrossRef]

- Renner, M., et al. (2021) Flavivirus maturation leads to the formation of an occupied lipid pocket in the surface glycoproteins. Nat Commun 12, 1238. [CrossRef]

- Sonora, M., et al. (2022) The stressed life of a lipid in the Zika virus membrane. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 1864, 183804. [CrossRef]

- Villalain, J. (2023) Phospholipid binding of the dengue virus envelope E protein segment containing the conserved His residue. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 1865, 184198. [CrossRef]

- Goellner, S., et al. (2023) Zika virus prM protein contains cholesterol binding motifs required for virus entry and assembly. Nature Communications 14, 7344. [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.Y., et al. (2020) Capsid protein structure in Zika virus reveals the flavivirus assembly process. Nature Communications 11, 895. [CrossRef]

- Martins, A.S., et al. (2024) Zika virus capsid protein closed structure modulates binding to host lipid systems. Protein Science 33. [CrossRef]

- Gutsche, I., et al. (2011) Secreted dengue virus nonstructural protein NS1 is an atypical barrel-shaped high-density lipoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 8003-8008. [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.P., et al. (2024) The inflammasome pathway is activated by dengue virus non-structural protein 1 and is protective during dengue virus infection. PLoS Pathog 20, e1012167. [CrossRef]

- Silva, T., et al. (2022) Dengue NS1 induces phospholipase A2 enzyme activity, prostaglandins, and inflammatory cytokines in monocytes. Antiviral Research 202, 105312. [CrossRef]

- Cortese, M., et al. (2017) Ultrastructural Characterization of Zika Virus Replication Factories. Cell Rep 18, 2113-2123. [CrossRef]

- Rossignol, E.D., et al. (2017) Zika virus induced cellular remodelling. Cell Microbiol 19. [CrossRef]

- Wieland, J., et al. (2021) Zika virus replication in glioblastoma cells: electron microscopic tomography shows 3D arrangement of endoplasmic reticulum, replication organelles, and viral ribonucleoproteins. Histochem Cell Biol 156, 527-538. [CrossRef]

- Cortese, M., et al. (2021) Determinants in Nonstructural Protein 4A of Dengue Virus Required for RNA Replication and Replication Organelle Biogenesis. J Virol 95, e0131021. [CrossRef]

- Pathak, D., et al. (2018) Lipidomics Suggests a New Role for Ceramide Synthase in Phagocytosis. ACS Chem Biol 13, 2280-2287. [CrossRef]

- van Meer, G., et al. (2008) Membrane lipids: where they are and how they behave. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 9, 112-124.

- Castro, B.M., et al. (2014) Ceramide: a simple sphingolipid with unique biophysical properties. Prog Lipid Res 54, 53-67. [CrossRef]

- Dahmane, S., et al. (2024) Cryo-electron tomography reveals coupled flavivirus replication, budding and maturation. bioRxiv, 2024.2010.2013.618056.

- Barad, B.A., et al. (2023) Quantifying organellar ultrastructure in cryo-electron tomography using a surface morphometrics pipeline. J Cell Biol 222. [CrossRef]

- Stelitano, D. and Cortese, M. (2024) Electron microscopy: The key to resolve RNA viruses replication organelles. Molecular Microbiology 121, 679-687. [CrossRef]

- Poveda Cuevas, S.A., et al. (2023) NS1 from Two Zika Virus Strains Differently Interact with a Membrane: Insights to Understand Their Differential Virulence. J Chem Inf Model 63, 1386-1400. [CrossRef]

- Jimenez de Oya, N., et al. (2023) Pharmacological Elevation of Cellular Dihydrosphingomyelin Provides a Novel Antiviral Strategy against West Nile Virus Infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 67, e0168722.

- Mingo-Casas, P., et al. (2023) Lipid signatures of West Nile virus infection unveil alterations of sphingolipid metabolism providing novel biomarkers. Emerg Microbes Infect 12, 2231556. [CrossRef]

- Elliott, K., et al. (2023) Profiling lipidomic changes in dengue-resistant and dengue-susceptible strains of Colombian Aedes aegypti after dengue virus challenge. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 17, e0011676. [CrossRef]

- Hehner, J., et al. (2025) Dengue virus is particularly sensitive to interference with long-chain fatty acid elongation and desaturation. J Biol Chem 301, 108222. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Z., et al. (2021) How Viruses Hijack and Modify the Secretory Transport Pathway. Cells 10. [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Ruiz, J.M., et al. (2020) The Regulation of Flavivirus Infection by Hijacking Exosome-Mediated Cell-Cell Communication: New Insights on Virus-Host Interactions. Viruses 12. [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, T., et al. (2024) Dissemination of the Flavivirus Subgenomic Replicon Genome and Viral Proteins by Extracellular Vesicles. Viruses. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.Y., et al. (2020) Lyn kinase regulates egress of flaviviruses in autophagosome-derived organelles. Nature Communications 11, 5189. [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.Y., et al. (2021) The Autophagosomes Containing Dengue Virus Proteins and Full-Length Genomic RNA Are Infectious. Viruses 13. [CrossRef]

- Cloherty, A.P.M., et al. (2024) Dengue virus exploits autophagy vesicles and secretory pathways to promote transmission by human dendritic cells. Front Immunol 15, 1260439. [CrossRef]

- Donoso-Quezada, J., et al. (2021) The role of lipids in exosome biology and intercellular communication: Function, analytics and applications. Traffic 22, 204-220. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T., et al. (2023) The role of autophagy in viral infections. Journal of Biomedical Science 30, 5. [CrossRef]

- Jaishy, B. and Abel, E.D. (2016) Lipids, lysosomes, and autophagy. J Lipid Res 57, 1619-1635.

- Sornprasert, S., et al. (2025) The interaction of Orthoflavivirus nonstructural proteins 3 and 5 with human fatty acid synthase. PLoS One 20, e0319207. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, H.H., et al. (2021) TMEM41B Is a Pan-flavivirus Host Factor. Cell 184, 133-148 e120. [CrossRef]

- Huang, D., et al. (2021) TMEM41B acts as an ER scramblase required for lipoprotein biogenesis and lipid homeostasis. Cell Metab 33, 1655-1670 e1658. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.E., et al. (2021) TMEM41B and VMP1 are scramblases and regulate the distribution of cholesterol and phosphatidylserine. J Cell Biol 220, e202103105. [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.Y., et al. (2023) A lipid scramblase TMEM41B is involved in the processing and transport of GPI-anchored proteins. J Biochem 174, 109-123. [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, M., et al. (2022) TMEM41B and VMP1 modulate cellular lipid and energy metabolism for facilitating dengue virus infection. PLoS Pathog 18, e1010763. [CrossRef]

- Trimarco, J.D., et al. (2021) TMEM41B is a host factor required for the replication of diverse coronaviruses including SARS-CoV-2. PLoS Pathog 17, e1009599. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Q., et al. (2023) TMEM41B Is an Interferon-Stimulated Gene That Promotes Pseudorabies Virus Replication. J Virol 97, e0041223. [CrossRef]

- Hsia, J.Z., et al. (2024) Lipid Droplets: Formation, Degradation, and Their Role in Cellular Responses to Flavivirus Infections. Microorganisms. [CrossRef]

- Herker, E. (2024) Lipid Droplets in Virus Replication. FEBS Lett 598, 1299-1300. [CrossRef]

- Wong, H.H., et al. (2024) Flaviviruses induce ER-specific remodelling of protein synthesis. PLoS Pathog 20, e1012766. [CrossRef]

- Schobel, A., et al. (2024) Inhibition of sterol O-acyltransferase 1 blocks Zika virus infection in cell lines and cerebral organoids. Commun Biol 7, 1089. [CrossRef]

- Reichert, I., et al. (2024) The triglyceride-synthesizing enzyme diacylglycerol acyltransferase 2 modulates the formation of the hepatitis C virus replication organelle. PLoS Pathog 20, e1012509. [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y., et al. (2023) Viral subversion of selective autophagy is critical for biogenesis of virus replication organelles. Nat Commun 14, 2698. [CrossRef]

- Heebner, J.E., et al. (2022) Deep Learning-Based Segmentation of Cryo-Electron Tomograms. J Vis Exp.

- Powell, B.M. and Davis, J.H. (2024) Learning structural heterogeneity from cryo-electron sub-tomograms with tomoDRGN. Nat Methods 21, 1525-1536. [CrossRef]

- van den Dries, K., et al. (2022) Fluorescence CLEM in biology: historic developments and current super-resolution applications. FEBS Lett 596, 2486-2496. [CrossRef]

- Berthias, F., et al. (2021) Disentangling Lipid Isomers by High-Resolution Differential Ion Mobility Spectrometry/Ozone-Induced Dissociation of Metalated Species. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom 32, 2827-2836. [CrossRef]

- Menzel, J.P., et al. (2023) Ozone-enabled fatty acid discovery reveals unexpected diversity in the human lipidome. Nat Commun 14, 3940. [CrossRef]

- Tamara, S., et al. (2022) High-Resolution Native Mass Spectrometry. Chem Rev 122, 7269-7326.

- Jayasekera, H.S., et al. (2024) Simultaneous Native Mass Spectrometry Analysis of Single and Double Mutants To Probe Lipid Binding to Membrane Proteins. Anal Chem 96, 10426-10433. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S., et al. (2024) Native Mass Spectrometry of Membrane Protein-Lipid Interactions in Different Detergent Environments. Anal Chem 96, 16768-16776. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y., et al. (2023) Combining native mass spectrometry and lipidomics to uncover specific membrane protein-lipid interactions from natural lipid sources. Chem Sci 14, 8570-8582. [CrossRef]

- Capolupo, L., et al. (2022) Sphingolipids control dermal fibroblast heterogeneity. Science 376, eabh1623. [CrossRef]

- Saunders, K.D.G., et al. (2023) Single-Cell Lipidomics Using Analytical Flow LC-MS Characterizes the Response to Chemotherapy in Cultured Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Anal Chem 95, 14727-14735. [CrossRef]

- Ren, J., et al. (2023) Mass Spectrometry Imaging-Based Single-Cell Lipidomics Profiles Metabolic Signatures of Heart Failure. Research (Wash D C) 6, 0019. [CrossRef]

- Schultz, C., et al. (2022) "Flash & Click": Multifunctionalized Lipid Derivatives as Tools To Study Viral Infections. J Am Chem Soc 144, 13987-13995. [CrossRef]

- Niphakis, M.J., et al. (2015) A Global Map of Lipid-Binding Proteins and Their Ligandability in Cells. Cell 161, 1668-1680. [CrossRef]

- Schlichter, A., et al. (2025) Designing New Natural-Mimetic Phosphatidic Acid: A Versatile and Innovative Synthetic Strategy for Glycerophospholipid Research. Angewandte Chemie (International ed. in English) n/a, e202510412.

- Yu, W., et al. (2022) A Chemoproteomics Approach to Profile Phospholipase D-Derived Phosphatidyl Alcohol Interactions. ACS Chem Biol 17, 3276-3283. [CrossRef]

- Kundu, S., et al. (2024) Bifunctional glycosphingolipid (GSL) probes to investigate GSL-interacting proteins in cell membranes. J Lipid Res 65, 100570. [CrossRef]

- Hoglinger, D., et al. (2017) Trifunctional lipid probes for comprehensive studies of single lipid species in living cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114, 1566-1571. [CrossRef]

- Muller, R., et al. (2021) Synthesis and Cellular Labeling of Multifunctional Phosphatidylinositol Bis- and Trisphosphate Derivatives. Angewandte Chemie (International ed. in English) 60, 19759-19765.

- Farley, S., et al. (2024) Trifunctional Sphinganine: A New Tool to Dissect Sphingolipid Function. ACS Chem Biol 19, 336-347. [CrossRef]

- Farley, S.E., et al. (2024) Trifunctional fatty acid derivatives: the impact of diazirine placement. Chem Commun (Camb) 60, 6651-6654. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A., et al. (2025) Trifunctional lipid derivatives: PE's mitochondrial interactome. Chem Commun (Camb) 61, 2564-2567. [CrossRef]

- Guzman, G., et al. (2025) The Lipid Interactome: An interactive and open access platform for exploring cellular lipid-protein interactomes. ArXiv.

- Roberts, M.A., et al. (2023) Parallel CRISPR-Cas9 screens identify mechanisms of PLIN2 and lipid droplet regulation. Dev Cell 58, 1782-1800 e1710. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.Y., et al. (2024) BioDolphin as a comprehensive database of lipid-protein binding interactions. Commun Chem 7, 288. [CrossRef]

- Bates, T.A., et al. (2025) Biolayer interferometry for measuring the kinetics of protein-protein interactions and nanobody binding. Nat Protoc 20, 861-883. [CrossRef]

- Sakanovic, A., et al. (2019) Surface Plasmon Resonance for Measuring Interactions of Proteins with Lipids and Lipid Membranes. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J.) 2003, 53-70.

- Rohlik, D.L., et al. (2023) Investigating membrane-binding properties of lipoxygenases using surface plasmon resonance. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 670, 47-54. [CrossRef]

- Calderin, J.D., et al. (2025) Use of Bio-Layer Interferometry (BLI) to Measure Binding Affinities of SNAREs and Phosphoinositides. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J.) 2887, 103-117.

- Estaras, M., et al. (2025) The intrinsically disordered protein NUPR1 binds to phospholipids. Protein Sci 34, e70236. [CrossRef]

- Jalali, P., et al. (2024) Exploration of lipid bilayer mechanical properties using molecular dynamics simulation. Arch Biochem Biophys 761, 110151. [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, S., et al. (2024) Unbiased MD simulations identify lipid binding sites in lipid transfer proteins. J Cell Biol 223. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).