Submitted:

16 December 2025

Posted:

17 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Experimental design

2.3. Prodromal behavioral profile

2.4. Organometrics

2.5. Immune functions

2.5.1. Collection of lymphocyte suspensions

2.5.2. Chemotaxis assay

2.5.3. Natural Killer (NK) cytotoxicity assay

2.5.4. Lymphoproliferation assay

2.5.5. Cytokine concentrations in cultures of spleen leukocytes

2.6. Redox-inflammatory state

2.6.1. Glutathione peroxidase (GPx) activity

2.6.2. Glutathione reductase (GR) activity

2.6.3. Total glutathione (GSH) content

2.6.4. Xanthine oxidase (XO) activity

2.7. Plasma corticosterone.

2.8. Statistical analysis

3. Results

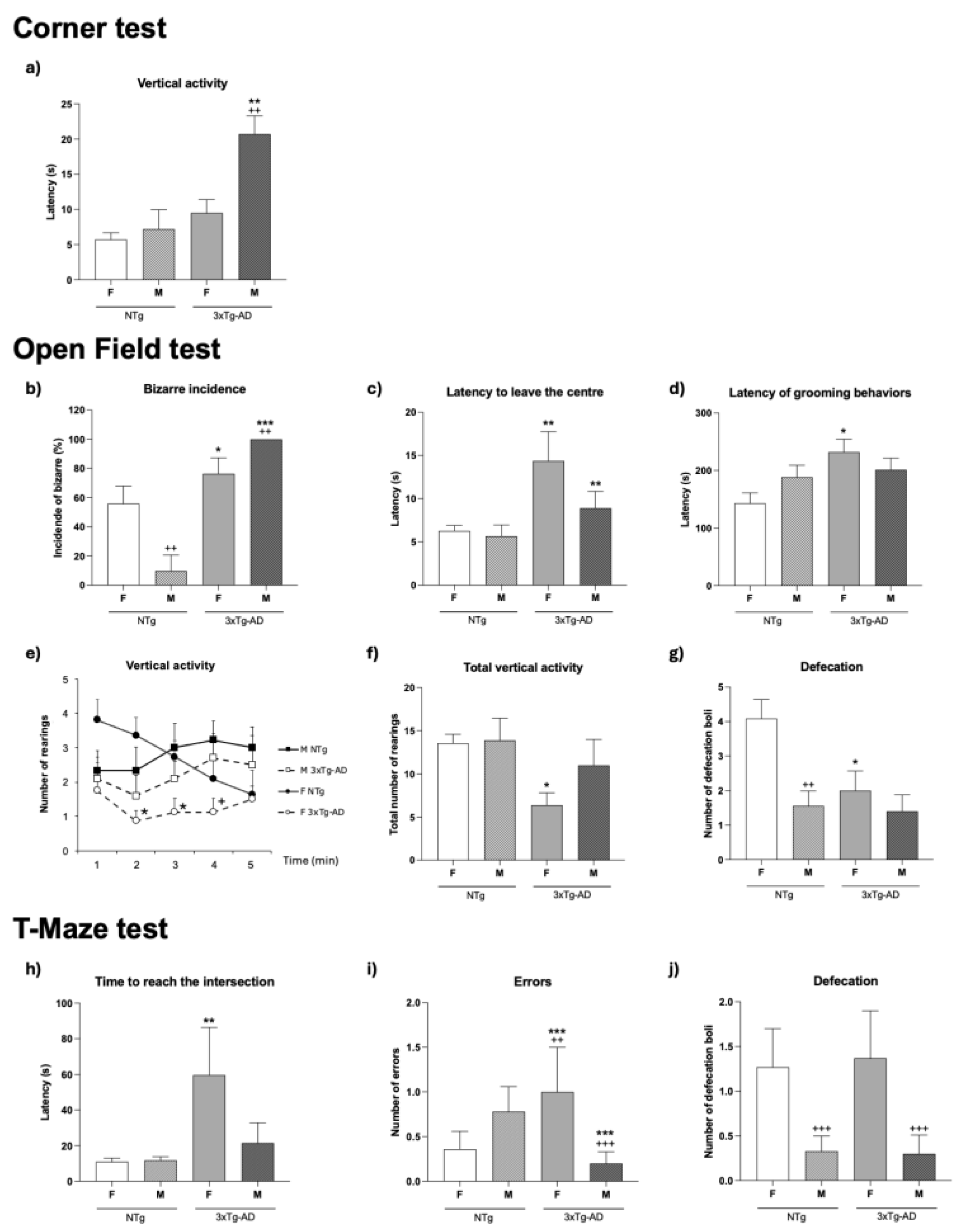

3.1. Prodromal behavioral state of 4-month-old male and female 3xTg-AD mice

3.2. Changes in physical condition, organometrics, and the endocrine system are sex-dependent and also observed at 4 months of age in male and female 3xTg-AD.

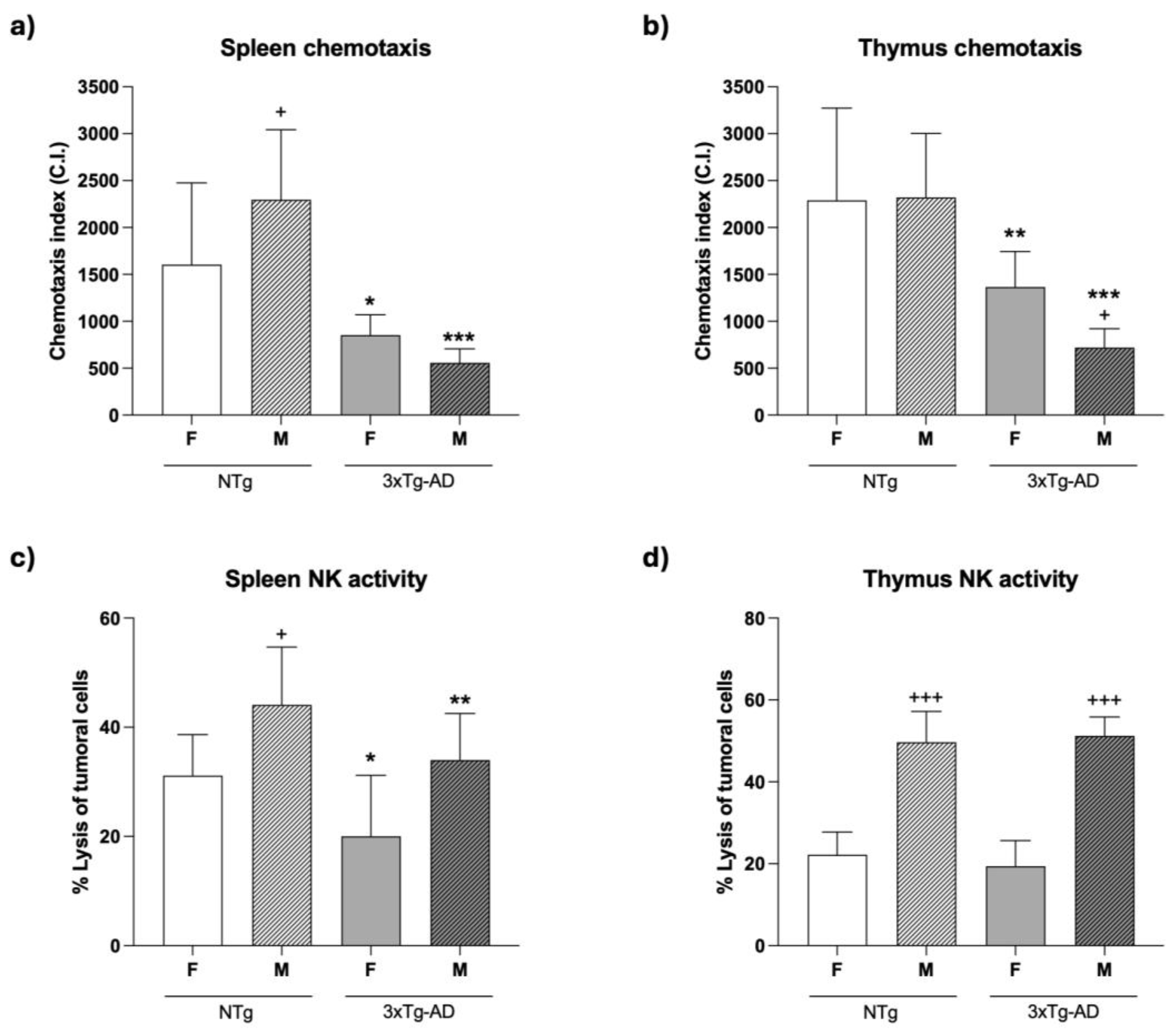

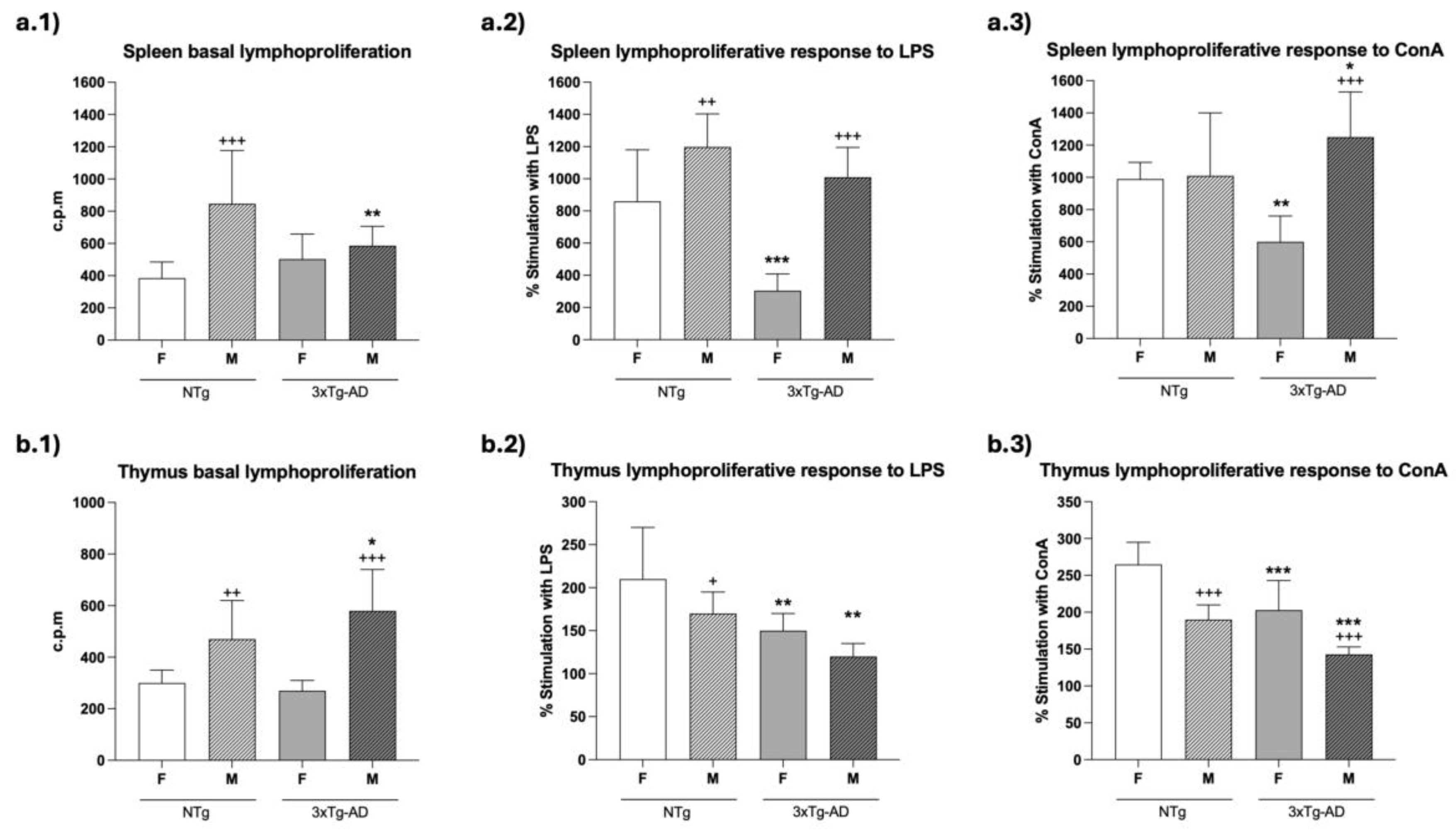

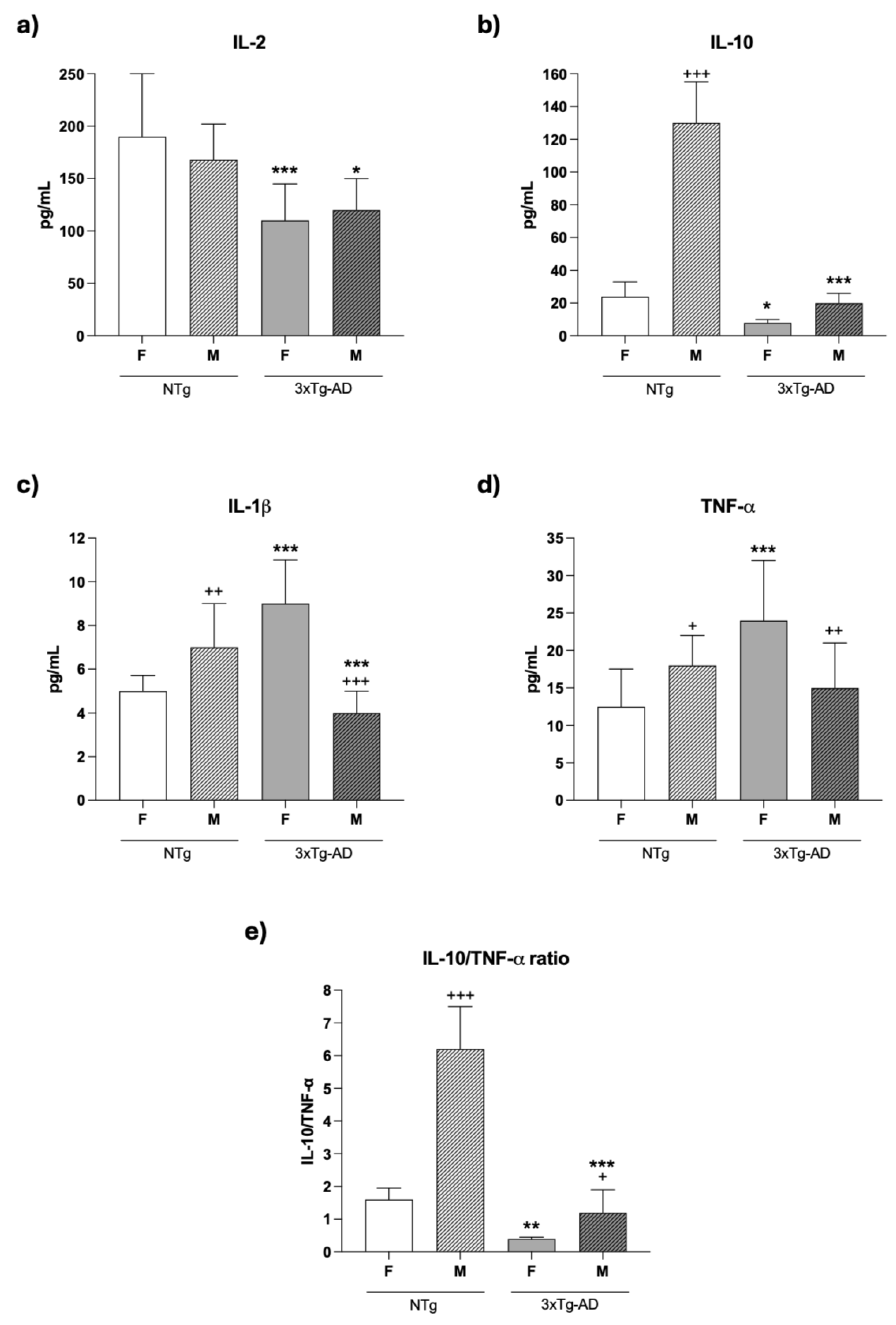

3.3. An impairment of the immune functions is presented in 4-month-old female and male 3xTg-AD mice

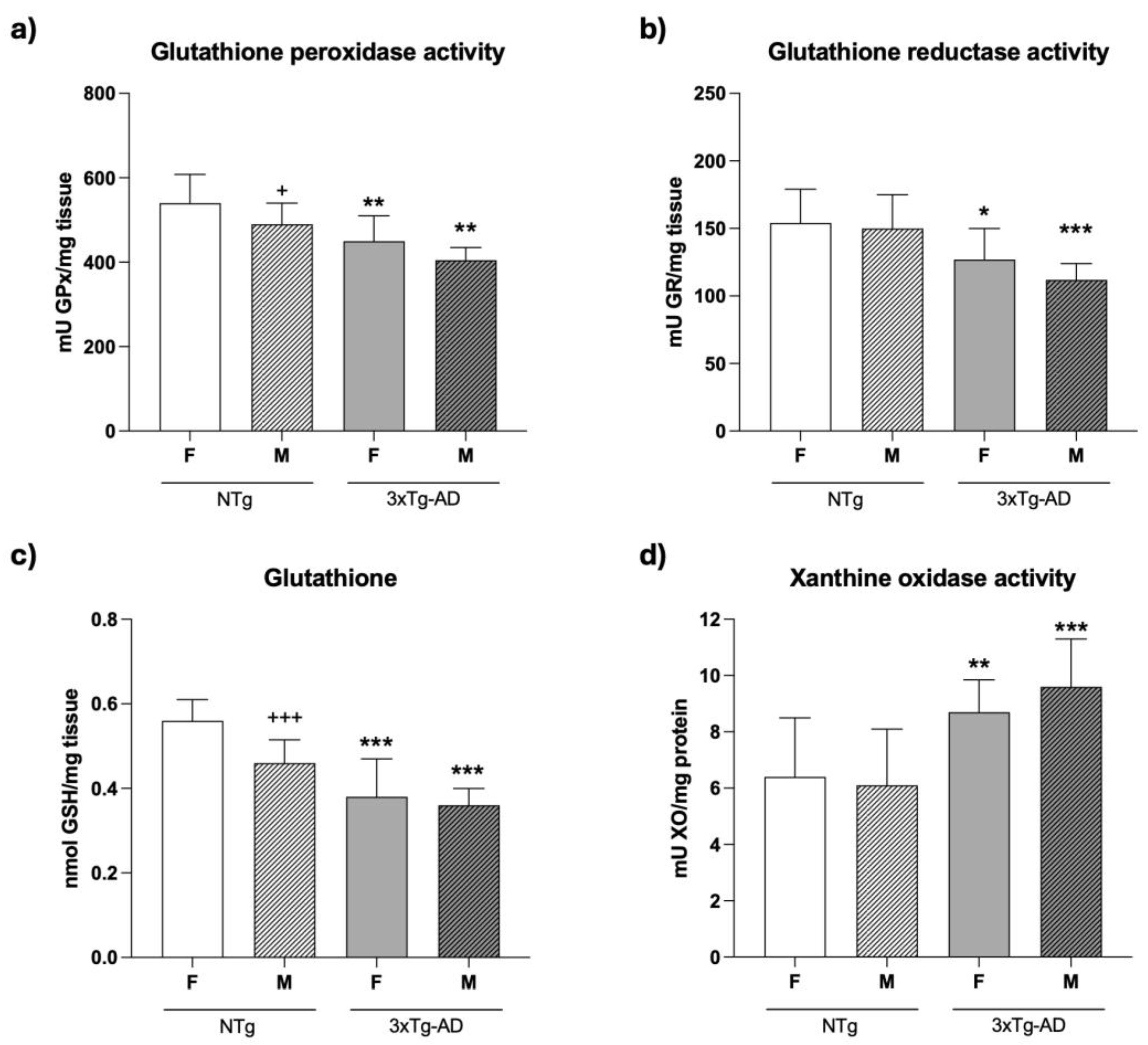

3.4. An oxidative stress is present in the spleen of 4-month-old female and male 3xTg-AD mice

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Knopman, D.S.; Amieva, H.; Petersen, R.C.; Chételat, G.; Holtzman, D.M.; Hyman, B.T.; Nixon, R.A.; Jones, D.T. Alzheimer Disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2021, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feigin, V.L.; Vos, T.; Nichols, E.; Owolabi, M.O.; Carroll, W.M.; Dichgans, M.; Deuschl, G.; Parmar, P.; Brainin, M.; Murray, C. The Global Burden of Neurological Disorders: Translating Evidence into Policy. Lancet Neurol. 2020, 19, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, D.; Wahlund, L.O.; Westman, E. The Heterogeneity within Alzheimer’s Disease. Aging 2018, 10, 3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livingston, G.; Huntley, J.; Liu, K. Y.; Costafreda, S. G.; Selbæk, G.; Alladi, S.; Ames, D.; Banerjee, S.; Burns, A.; Brayne, C.; Fox, N. C.; Ferri, C. P.; Gitlin, L. N.; Howard, R.; Kales, H. C.; Kivimäki, M.; Larson, E. B.; Nakasujja, N.; Rockwood, K.; Samus, Q.; Shirai, K.; Singh-Manoux, A.; Schneider, L.S.; Walsh, S.; Yao, Y.; Sommerlad, A.; Mukadam, N. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2024 report of the Lancet standing Commission. Lancet 2024, 404, 572–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lomi, M.; Geraci, F.; Del Seppia, C.; Dolciotti, C.; Del Carratore, R.; Bongioanni, P. Biomarker profile in peripheral blood cells related to Alzheimer´s disease. Mol Neurobiol. 2025, 8949–8964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasumo, F.; Watanabe, A.; Kimura, Y.; Yamauchi, Y.; Ogata, A.; Ikenuma, H.; Abe, J.; Minami, H.; Nihashi, T.; Yokoi, K.; Shimoda, N.; Kasuga, K.; Ikeuchi, T.; Takeda, A.; Sakurai, T.; Ito, K.; Kato, T. Plasma IL-6 levels as a biomarker for behavioral changes in Alzheimer´s disease. Neuroimmunomodulation 2025, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malarte, M.L.; Chiotis, K.; Ioannou, K.; Rodriguez-Vieitez, E. Peripheral inflammation is associated with greater neuronal injury and lower episodic memory among late middle-aged adults. J Neurochem 2025, 169, e70222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Fuente, M.; Miquel, J. An update of the oxidation-inflammation theory of aging: the involvement of the immune system in oxi-inflamm-aging. Curr Pharm Des 2009, 15, 3003–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, R. M. The Role of Immunity in Alzheimer's Disease. Adv Biol 2022, 6, e2101166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, C.; Fritts, A.; Broadway, J.; Brawman-Mintzer, O.; Mintzer, J. Neuroinflammation: A Driving Force in the Onset and Progression of Alzheimer's Disease. J Clin Med. 2025, 14, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heneka, M. T.; van der Flier, W. M.; Jessen, F.; Hoozemanns, J.; Thal, D. R.; Boche, D.; Brosseron, F.; Teunissen, C.; Zetterberg, H.; Jacobs, A. H.; et al. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2025, 25, 321–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zang, X.; Chen, S.; Zhu, J.; Ma, J.; Zhai, Y. The Emerging Role of Central and Peripheral Immune Systems in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front Aging Neurosci 2022, 14, 872134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, T. Y.; Zheng, Q.; Wang, X. Peripheral and central neuroimmune mechanisms in Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis. Mol Neurodegener 2025, 20, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vida, C.; Martinez de Toda, I.; Garrido, A.; Carro, E.; Molina, J. A.; De la Fuente, M. Impairment of Several Immune Functions and Redox State in Blood Cells of Alzheimer's Disease Patients. Relevant Role of Neutrophils in Oxidative Stress. Front Immunol 2018, 8, 1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puzzo, D.; Gulisano, W.; Palmeri, A.; Arancio, O. Rodent Models for Alzheimer’s Disease Drug Discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2015, 10, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Varo, R.; Mejias-Ortega, M.; Fernandez-Valenzuela, J. J.; Nuñez-Diaz, C.; Caceres-Palomo, L.; Vegas-Gomez, L.; Sanchez-Mejias, E.; Trujillo-Estrada, L.; Garcia-Leon, J. A.; Moreno-Gonzalez, I.; Vizuete, M.; Vitorica, J.; Baglietto-Vargas, D.; Gutierrez, A. Transgenic Mouse Models of Alzheimer's Disease: An Integrative Analysis. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 5404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oddo, S.; Caccamo, A.; Shepherd, J. D.; Murphy, M. P.; Golde, T. E.; Kayed, R.; Metherate, R.; Mattson, M. P.; Akbari, Y.; LaFerla, F. M. Triple-transgenic model of Alzheimer's disease with plaques and tangles: intracellular Abeta and synaptic dysfunction. Neuron 2003, 39, 409–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oddo, S.; Caccamo, A.; Kitazawa, M.; Tseng, B. P.; LaFerla, F. M. Amyloid deposition precedes tangle formation in a triple transgenic model of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging 2003, 24, 1063–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oddo, S.; Caccamo, A.; Green, K. N.; Liang, K.; Tran, L.; Chen, Y.; Leslie, F. M.; LaFerla, F. M. Chronic nicotine administration exacerbates tau pathology in a transgenic model of Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005, 102, 3046–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oddo, S.; Caccamo, A.; Tran, L.; Lambert, M. P.; Glabe, C. G.; Klein, W. L.; LaFerla, F. M. Temporal profile of amyloid-beta (Abeta) oligomerization in an in vivo model of Alzheimer's disease. A link between Abeta and tau pathology. J Biol Chem 2006, 281, 1599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billings, L. M.; Oddo, S.; Green, K. N.; McGaugh, J. L.; LaFerla, F. M. Intraneuronal Abeta causes the onset of early Alzheimer's disease-related cognitive deficits in transgenic mice. Neuron 2005, 45, 675–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janelsins, M. C.; Mastrangelo, M. A.; Oddo, S.; LaFerla, F. M.; Federoff, H. J.; Bowers, W. J. Early correlation of microglial activation with enhanced tumor necrosis factor-alpha and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression specifically within the entorhinal cortex of triple transgenic Alzheimer's disease mice. J Neuroinflammation 2005, 2, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitazawa, M.; Oddo, S.; Yamasaki, T. R.; Green, K. N.; LaFerla, F. M. Lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation exacerbates tau pathology by a cyclin-dependent kinase 5-mediated pathway in a transgenic model of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci 2005, 25, 8843–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterniczuk, R.; Antle, M. C.; Laferla, F. M.; Dyck, R. H. Characterization of the 3xTg-AD mouse model of Alzheimer's disease: part 2. Behavioral and cognitive changes. Brain Res 2010, 1348, 149–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belfiore, R.; Rodin, A.; Ferreira, E.; Velazquez, R.; Branca, C.; Caccamo, A.; Oddo, S. Temporal and regional progression of Alzheimer's disease-like pathology in 3xTg-AD mice. Aging Cell 2019, 18, e12873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giménez-Llort, L.; Blázquez, G.; Cañete, T.; Johansson, B.; Oddo, S.; Tobeña, A.; LaFerla, F. M.; Fernández-Teruel, A. Modeling behavioral and neuronal symptoms of Alzheimer's disease in mice: a role for intraneuronal amyloid. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2007, 31, 125–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muntsant, A.; Castillo-Ruiz, M. D. M.; Giménez-Llort, L. Survival Bias, Non-Lineal Behavioral and Cortico-Limbic Neuropathological Signatures in 3xTg-AD Mice for Alzheimer's Disease from Premorbid to Advanced Stages and Compared to Normal Aging. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 13796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giménez-Llort, L.; Torres-Lista, V.; De la Fuente, M. Crosstalk between behavior and immune system during the prodromal stages of Alzheimer's disease. Curr Pharm Des 2014, 20, 4723–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maté, I.; Cruces, J.; Giménez-Llort, L.; De la Fuente, M. Function and redox state of peritoneal leukocytes as preclinical and prodromic markers in a longitudinal study of triple-transgenic mice for Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2015, 43, 213–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceprián, N.; Martínez de Toda, I.; Maté, I.; Garrido, A.; Gimenez-Llort, L.; De la Fuente, M. Prodromic Inflammatory-Oxidative Stress in Peritoneal Leukocytes of Triple-Transgenic Mice for Alzheimer's Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 6976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giménez-Llort, L.; Arranz, L.; Maté, I.; De la Fuente, M. Gender-specific neuroimmunoendocrine aging in a triple-transgenic 3xTg-AD mouse model for Alzheimer's disease and its relation with longevity. Neuroimmunomodulation 2008, 15, 331–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- St-Amour, I.; Bosoi, C. R.; Paré, I.; Ignatius Arokia Doss, P. M.; Rangachari, M.; Hébert, S. S.; Bazin, R.; Calon, F. Peripheral adaptive immunity of the triple transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. J Neuroinflammation 2019, 16, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S. H.; Kim, J.; Lee, M. J.; Kim, Y. Abnormalities of plasma cytokines and spleen in senile APP/PS1/Tau transgenic mouse model. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 15703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraile-Ramos, J.; Reig-Vilallonga, J.; Giménez-Llort, L. Glomerular Hypertrophy and Splenic Red Pulp Degeneration Concurrent with Oxidative Stress in 3xTg-AD Mice Model for Alzheimer's Disease and Its Exacerbation with Sex and Social Isolation. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 6112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantone, A.F.; Burgaletto, C.; Di Benedetto, G.; Gaudio, G.; Giallongo, C.; Caltabiano, R.; Broggi, G.; Bellanca, C. M.; Cantarella, G.; Bernardini, R. Rebalancing immune interactions within the brain-spleen axis mitigates neuroinflammation in an aging mouse model of Alzheimer´s disease. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2025, 20, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, R.; Guo, J.; Ye, X. Y.; Xie, Y.; Xie, T. Oxidative stress: The core pathogenesis and mechanism of Alzheimer's disease. Ageing Res Rev 2022, 77, 101619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Lista, V.; Parrado-Fernández, C.; Alvarez-Montón, I.; Frontiñán-Rubio, J.; Durán-Prado, M.; Peinado, J.R.; Johansson, B.; Alcaín, F.J.; Giménez-Llort, L. Neophobia, NQO1 and SIRT1 as premorbid and prodromal indicators of AD in 3xTg-AD mice. Behav Brain Res. 2014, 271, 140–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Chen, Y.; Yang, A.; Chen, C.; Liao, L.; Li, S.; Ying, M.; Tian, J.; Liu, Q.; Ni, J. Redox Proteomic Profiling of Specifically Carbonylated Proteins in the Serum of Triple Transgenic Alzheimer's Disease Mice. Int J Mol Sci 2016, 17, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Fuente, M. Oxidation and inflammation in the immune and nervous systems, a link between aging and anxiety. In Handbook of immunosenescence; Springer, 2019; pp. pp 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, J.; Van Hoecke, L.; Vandenbroucke, R.E. The Impact of Systemic Inflammation on Alzheimer's Disease Pathology. Front Immunol. 2022, 12, 796867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montacute, R.; Foley, K.; Forman, R.; Else, K. J.; Cruickshank, S. M.; Allan, S. M. Enhanced susceptibility of triple transgenic Alzheimer's disease (3xTg-AD) mice to acute infection. J Neuroinflammation 2017, 14, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munstant, A.; Giménez-Llort, L. Crosstalk of Alzheimer's disease-phenotype, HPA axis, splenic oxidative stress and frailty in late-stages of dementia, with special concerns on the effects of social isolation: A translational neuroscience approach. Front Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 969381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, A.; Cruces, J.; Ceprián, N.; Corpas, I.; Tresguerres, J. A.; De la Fuente, M. Social environment improves immune function and redox state in several organs from prematurely aging female mice and increases their lifespan. Biogerontology 2019, 20, 49–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, L.L.; Wilson, R.S.; Bienias, J.L.; Schneider, J.A.; Evans, D.A.; Bennett, D.A. Sex differences in the clinical manifestations of Alzheimer disease pathology. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005, 62, 685–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, M.; Iulita, M.F.; Cavedo, E.; Chiesa, P. A.; Schumacher Dimech, A.; Santuccione Chadha, A.; Baracchi, F.; Girouard, H.; Misoch, S.; Giacobini, E.; Depypere, H.; Hampel, H. & Women’s Brain Project and the Alzheimer Precision Medicine Initiative. Sex differences in Alzheimer disease - the gateway to precision medicine. Nature reviews. Neurology 2018, 14, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, L. M.; Diaz-Del Cerro, E.; Felix, J.; Gonzalez-Sanchez, M.; Ceprian, N.; Guerra-Perez, N.; Novelle, M. G.; Martinez de Toda, I.; De la Fuente, M. Sex differences in neuroimmunoendocrine communication. Involvement on longevity. Mech Ageing Dev 2023, 211, 111798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J. T.; Wang, Z. J.; Cai, H. Y.; Yuan, L.; Hu, M. M.; Wu, M. N.; Qi, J. S. Sex Differences in Neuropathology and Cognitive Behavior in APP/PS1/tau Triple-Transgenic Mouse Model of Alzheimer's Disease. Neurosci Bull 2018, 34, 736–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapadia, M.; Mian, M.F.; Michalski, B.; Azam, A.B.; Ma, D.; Salwierz, P.; Christopher, A.; Rosa, E.; Zovkic, I.B.; Forsythe, P. Sex-dependent differences in spontaneous autoimmunity in adult 3xTg-AD mice. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018, 63, 1191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kane, A.E.; Shin, S.; Wong, A.A.; Fertan, E.; Faustova, N.S.; Howlett, S.E.; Brown, R.E. Sex differences in healthspan predict lifespan in the 3xTg-AD mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci 2018, 10, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennison, J. L.; Ricciardi, N. R.; Lohse, I.; Volmar, C. H.; Wahlestedt, C. Sexual Dimorphism in the 3xTg-AD Mouse Model and Its Impact on Pre-Clinical Research. J Alzheimers Dis 2021, 80, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeta-Corral, R.; De la Fuente, M.; Giménez-Llort, L. Sex-dependent worsening of NMDA-induced responses, anxiety, hypercortisolemia, and organometry of early peripheral immunoendocrine impairment in adult 3xTg-AD mice and their long-lasting ontogenic modulation by neonatal handling. Behav Brain Res 2023, 438, 114189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, A. J.; Del Genio, C. L.; Swain, A. B.; Pizzi, E. M.; Watson, S. C.; Tapiavala, V. N.; Zanazzi, G. J.; Gaur, A. B. Age, sex and Alzheimer's disease: a longitudinal study of 3xTg-AD mice reveals sex-specific disease trajectories and inflammatory responses mirrored in postmortem brains from Alzheimer's patients. Alzh Res Ther. 2024, 16, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meziane, H.; Ouagazzal, A. M.; Aubert, L.; Wietrzych, M.; Krezel, W. Estrous cycle effects on behavior of C57BL/6J and BALB/cByJ female mice: implications for phenotyping strategies. Genes Brain Behav 2007, 6, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, R. A.; Burk, R. F. Glutathione peroxidase activity in selenium-deficient rat liver. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1976, 71, 952–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, V.; Williams, C. H., Jr. On the reaction mechanism of yeast glutathione reductase. J Biol Chem 1965, 240, 4470–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Wang, B.; Ao, H. Corticosterone effects induced by stress and immunity and inflmmation: mechanisms of communication. Front Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1448750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerejeira, J; Lagarto, L; Mukaetova-Ladinska, EB. Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Front Neurol. 2012, 3, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benaroya-Milshtein, N.; Hollander, N.; Apter, A.; Kukulansky, T.; Raz, N.; Wilf, A.; Yaniv, I.; Pick, C. G. Environmental enrichment in mice decreases anxiety, attenuates stress responses and enhances natural killer cell activity. Eur J Neurosci 2004, 20, 1341–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deacon, R.M.J.; Rawlins, J.N.P. T-Maze Alternation in the Rodent. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giménez-Llort, L.; Ferré, S.; Martínez, E. Effects of the systemic administration of kainic acid and NMDA on exploratory activity 861 in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 1995, 51, 205–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinton, L. K.; Billings, L. M.; Green, K. N.; Caccamo, A.; Ngo, J.; Oddo, S.; McGaugh, J. L.; LaFerla, F. M. Age-dependent sexual dimorphism in cognition and stress response in the 3xTg-AD mice. Neurobiol Dis 2007, 28, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, HH; Dixit, V D. Metabolic regulation of immunological aging. Nat Aging 2025, 5, 1425–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukushima, Y; Ueno, R; Minato, N; Hattori, M. Senescence-associates T cells in immunosenescence and disease. Int Immunol. 2025, 37, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, AK; TRotta, E; Simeonov, D R; Marson, A; Bluestone, JA. Revisiting IL-1: Biology and therapeutic prospects. Sci Immunol 2018, 3, eaat1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulios, P; Skampouras, S; Piperi, Ch. Deciphering the role of cytokines in aging: Biomarker potential and effective targeting. Mech Ageing Dev. 2025, 224, 112036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonsalla, M.M.; Lamming, D.W. Geroprotective interventions in the 3xTg mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. GeroScience 2023, 45, 1343–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, PA; Guil-Guerrero, JL. Beyond Transgenic Mice: Emerging Models and Translational Strategies in Alzheimer's Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2025, 26, 5541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubal, D. B.; Broestl, L.; Worden, K. Sex and gonadal hormones in mouse models of Alzheimer's disease: what is relevant to the human condition? Biol Sex Differ 2012, 3, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fertan, E.; Rodrigues, G. J.; Wheeler, R. V.; Goguen, D.; Wong, A. A.; James, H.; Stadnyk, A.; Brown, R. E.; Weaver, I. C. G. Cognitive Decline, Cerebral-Spleen Tryptophan Metabolism, Oxidative Stress, Cytokine Production, and Regulation of the Txnip Gene in a Triple Transgenic Mouse Model of Alzheimer's Disease. Am J Pathol. 2019, 189, 1435–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochi, S.; Iga, J. I.; Funahashi, Y.; Yoshino, Y.; Yamazaki, K.; Kumon, H.; Mori, H.; Ozaki, Y.; Mori, T.; Ueno, S. I. Identifying Blood Transcriptome Biomarkers of Alzheimer's Disease Using Transgenic Mice. Mol Neurobiol 2020, 57, 4941–4951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapadia, M.; Mian, M. F.; Ma, D.; Hutton, C. P.; Azam, A.; Narkaj, K.; Cao, C.; Brown, B.; Michalski, B.; Morgan, D.; Forsythe, P.; Zovkic, I. B.; Fahnestock, M.; Sakic, B. Differential effects of chronic immunosuppression on behavioral, epigenetic, and Alzheimer's disease-associated markers in 3xTg-AD mice. Alzheimer's Res Ther. 2021, 13, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| BEHAVIORAL TESTS | NTg | 3xTg-AD | Statistical Factor Analysis G, genotype S, Sex |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females (n=11) | Males (n=9) |

Females (n=8) |

Males (n=10) |

||

| CORNER TEST | |||||

| Sequence of behavioral events | |||||

| Vertical activity (latency, s) | see Fig. 1a | G**,S**, G×S* | |||

| Locomotor activity | |||||

| Horizontal activity (corners, n) | 13.73 ± 0.98 | 11.89 ± 1.29 | 11.25 ± 2.66 | 8.20 ± 1.42 | n.s.,n.s.,n.s. |

| Vertical activity (rearings, n) | 6.36 ± 0.47 | 7.22 ± 1.26 | 4.38 ± 1.02 | 2.30 ± 0.63 | G***, n.s., n.s. |

| OPEN FIELD TEST | |||||

| Sequence of behavioral events | |||||

| Initial movement (latency, s) | 1.36 ± 0.28 | 0.33 ± 0.17 | 2.50 ± 0.53 a | 1.10 ± 0.38 | G*, n.s., n.s. |

| Incidence of bizarre behavior (%) | see Fig. 1b | G***, S**, G×S** | |||

| Exit from the centre (latency, s) | see Fig. 1c | G**, n.s., n.s. | |||

| Entrance to periphery (latency, s) | 15.36 ± 2.04 | 49.4 ± 16.5 | 48.8 ± 27.6 | 24.2 ± 5.05 | n.s., n.s., G×S** |

| Vertical activity (latency, s) | 32.18 ± 2.88 | 46.2 ± 10.2 | 72.1 ± 27.1 a | 74.6 ± 21.0 | G*, n.s., n.s. |

| Self-grooming (latency, s) | see Fig. 1d | G*, n.s., n.s. | |||

| Locomotor activity | |||||

| Vertical activity per minute (rearings, n) |

see Fig. 1e | G*, n.s., n.s./ G*(r2,r3) S*(r4) n.s. |

|||

| Total vertical activity (rearings, n) |

see Fig. 1f | n.s., n.s., n.s. | |||

| Self-grooming behavior | |||||

| Self-grooming episodes (n) | 1.36 ± 0.20 | 1.33 ± 0.37 | 0.75 ± 0.25 | 1.20 ± 0.25 | n.s., n.s., n.s. |

| Total self-grooming duration (s) | 4.55 ± 0.73 | 4.00 ± 0.85 | 2.50 ± 0.76 | 4.40 ± 0.79 | n.s., n.s., n.s. |

| Emotional behaviors | |||||

| Defecation boli (n) | see Fig. 1g | G*, S**, n.s. | |||

| Urination (incidence) | 0.27 ± 0.14 | 0 ± 0 | 0.25 ± 0.16 | 0.30 ± 0.15 | n.s.,n.s.,n.s. |

| T-MAZE | |||||

| Sequence of behavioral events | |||||

| Reaching intersection (latency, s) | see Fig. 1h | G*, n.s., n.s. | |||

| Exploratory efficiency (time, s) | 44.55 ± 14.3 | 56.0 ± 12.6 | 88.0 ± 27.3 | 36.3 ± 12.0 | n.s., n.s., n.s. |

| Ratio Time in the arms (s) | 4.31 ± 0.77 | 4.90 ± 0.72 | 2.86 ± 0.63 a | 2.69 ± 0.37 a | G**, n.s., n.s. |

| Errors (n) | see Fig. 1i | G***, n.s., G×S* | |||

| Emotional behaviors | |||||

| Defecation boli (n) | see Fig. 1j | n.s., S**, n.s. | |||

| Urination (incidence) | 0.55 ± 0.21 | 0 ± 0 | 0.12 ± 0.12 | 0.10 ± 0.10 | n.s., n.s., n.s. |

| NTg | 3xTg-AD | Statistics Factor Analysis G, genotype S, sex |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females (n=11) | Males (n=9) |

Females (n=8) | Males (n=10) |

||

| Physical condition | |||||

| Body Weight (g) | 21.7 ± 1.00 | 26.7 ± 0.50 b | 26.3 ± 0.60 a | 34.5 ± 0.90 a,b | G*** , S***, n.s. |

| % WAT in body weight | 1.01 ± 0.06 | 0.80 ± 0.03 | 1.39 ± 0.04 a | 1.22 ± 0.14 a | G*** , S***, n.s. |

| Peripheral immune system | |||||

| % Thymus in body weight | 0.18 ± 0.06 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 0.15 ± 0.00 | 0.10 ± 0.00 | G*** , S** , n.s. |

| % Spleen in body weight | 0.38 ± 0.01 | 0.32 ± 0.01 | 0.52 ± 0.02 a | 0.45 ± 0.07 a | G*** , S** , n.s. |

| Endocrine system | |||||

| Adrenal glands (mg) | 8.2 ± 0.2 | 7.40 ± 0.5 | 7.3 ± 0.2 | 9.4 ± 0.6 | n.s., n.s., G × S** |

| Plasma corticosterone (ng/mL) | 35.5 ± 8.3 | 28.9 ± 7.2 | 43.3 ± 5.7 | 42.6 ± 7.8 | n.s., n.s., n.s. |

| Statistics Factor Analysis G, genotype S, sex |

||

|---|---|---|

| Spleen Chemotaxis (C.I.) | G*** , n.s., G × S* | |

| Thymus Chemotaxis (C.I.) | G*** , n.s., n.s. | |

| Spleen NK Activity (% Lysis) | G***, n.s., G × S* | |

| Thymus NK Activity (% Lysis) | n.s., S***, n.s. | |

| Spleen basal lymphoproliferation (c.p.m.) | n.s., S***, G × S** | |

| Spleen lymphoproliferative response to LPS (% Stimulation) | G*** , S***, G × S* | |

| Spleen lymphoproliferative response to ConA (% Stimulation) | n.s., S***, G × S*** | |

| Thymus basal lymphoproliferation (c.p.m.) | n.s., S***, n.s. | |

| Thymus lymphoproliferative response to LPS (% Stimulation) | G*** , S**, n.s. | |

| Thymus lymphoproliferative response to ConA (% Stimulation) | G*** , S***, n.s. | |

| IL-2 (pg/ml) | G*** , n.s., n.s. | |

| IL-10 (pg/ml) | G*** , S***, G × S*** | |

| IL-1β (pg/ml) | n.s., S**, G × S*** | |

| TNF-α (pg/ml) | G* , n.s., G × S*** | |

| IL-10/TNF-α ratio | G***, S***, G × S*** |

| NTg | 3xTg-AD | Statistics Factor Analysis G, genotype S, sex |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females (n=11) | Males (n=9) |

Females (n=8) | Males (n=10) |

||

| IL-2 (pg/ml) | 33 ± 13 | 37 ± 15 | 13 ± 4 aa | 43 ± 16 bbb | n.s., S***, G × S***. |

| IL-10 (pg/ml) | 80 ± 15 | 306 ± 78 bbb | 20 ± 5 aa | 112 ± 40 aaa, bbb | G***,S***, G × S*** |

| IL-1β (pg/ml) | 5 ± 1 | 6 ± 2 | 5 ± 1 | 6 ± 2 | n.s., n.s., n.s. |

| TNF-α (pg/ml) | 18 ± 6 | 18 ± 4 | 17 ± 5 | 16 ± 4 | n.s., n.s., n.s. |

| IL-10/TNF-α ratio | 5.23 ± 0.92 | 14.24 ± 1.95 bbb | 1.34 ± 0.44 aaa | 6.30 ± 1.49 aaa, bbb | G***,S***, G × S*** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).