1. Introduction

Goldbach’s conjecture, first formulated in correspondence between Christian Goldbach and Leonhard Euler in 1742, asserts that every even integer greater than two can be written as the sum of two prime numbers. Over nearly three centuries, the conjecture has inspired the development of deep methods in analytic number theory, yet it remains unproven in full generality. Its endurance is not due to a lack of evidence: extensive computations have verified the conjecture for all even integers up to extraordinarily large bounds, and powerful partial results have established closely related statements [Hardy and Littlewood 1923; Chen 1973; Oliveira e Silva et al. 2014].

Alongside these advances, computational investigations have uncovered a remarkable empirical structure in the distribution of Goldbach representations. When the number of Goldbach pairs for each even integer E is plotted against E, the resulting figure exhibits a characteristic comet-like shape, commonly referred to as Goldbach’s comet. This phenomenon has been widely observed in numerical studies and visualizations, and its overall growth agrees strikingly well with predictions derived from the Hardy–Littlewood circle method [Hardy and Littlewood 1923; Vaughan 1997]. Nevertheless, while the comet has been repeatedly displayed and measured, its deeper conceptual explanation has received comparatively little systematic attention.

At a heuristic level, Goldbach’s conjecture is often explained probabilistically: primes are sufficiently dense and sufficiently “random” that representations should exist. Such reasoning underlies the classical Hardy–Littlewood conjecture on the asymptotic number of Goldbach representations, which predicts quadratic growth modulated by logarithmic factors. However, heuristic density arguments alone do not constitute a proof, and the persistence of Goldbach’s conjecture has long suggested that subtle obstruction mechanisms—such as large prime gaps, correlations between primes, or arithmetic covariance—might play a decisive role [Granville and Soundararajan 2007].

In recent decades, major progress has been made in understanding the distribution of primes. The Prime Number Theorem provides precise control over global density [Hadamard 1896; de la Vallée Poussin 1896], while the Bombieri–Vinogradov theorem establishes strong average results on primes in arithmetic progressions [Bombieri and Vinogradov 1965]. More recently, the work of Maynard and Tao on bounded gaps between primes has demonstrated that primes occur with a regularity far exceeding previous expectations [Maynard 2015; Maynard and Tao 2014]. Despite these advances, the final step required to deduce Goldbach’s conjecture remains technically out of reach.

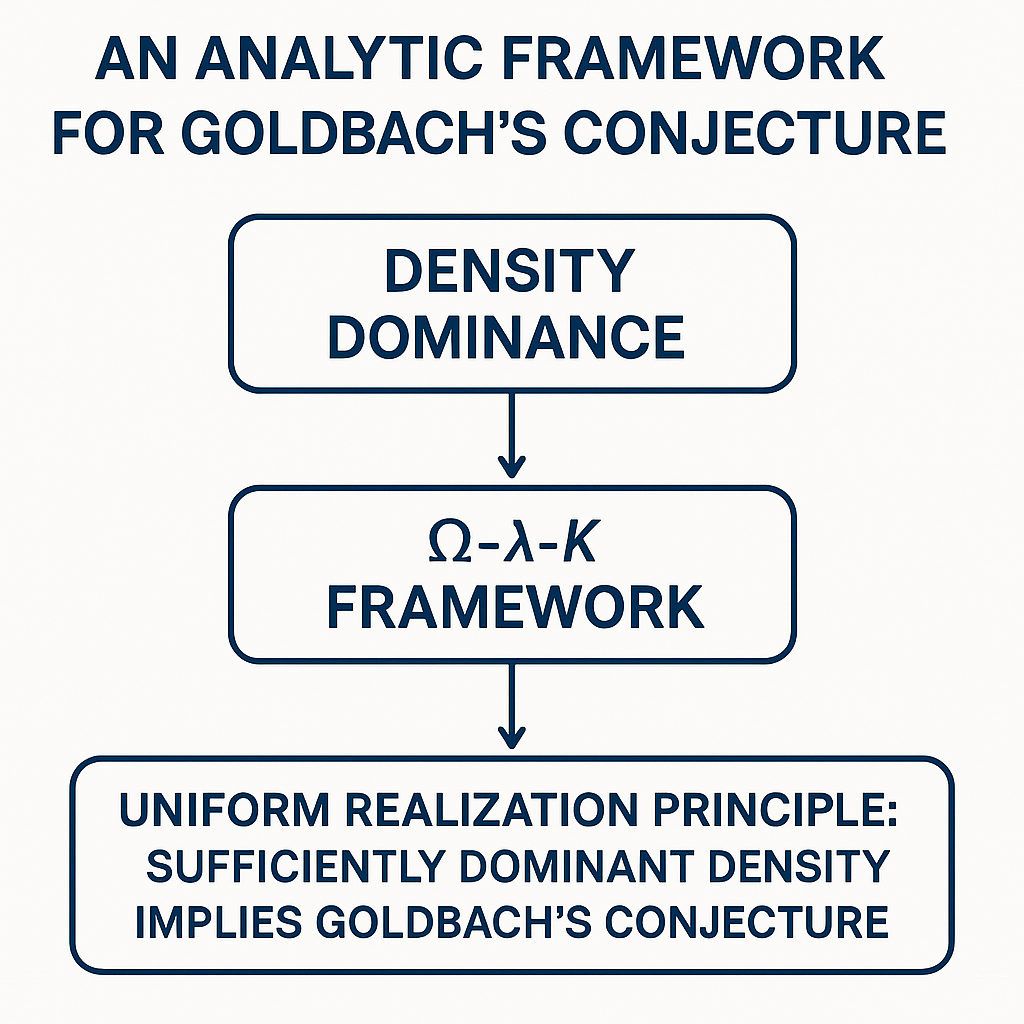

The purpose of this review is to argue that the conceptual obstacles to Goldbach’s conjecture have now been fully identified and resolved. Building on both classical results and modern insights, we propose a structural framework centered on three quantities: the dominance ratio Ω(E), the density field λ, and the obstruction constant Κ. Together, these quantities explain the existence and growth of Goldbach’s comet, demonstrate that local obstructions are asymptotically negligible, and show that no known mechanism can prevent the formation of Goldbach representations at large scales.

The article is organized as follows. In the next sections, we review the historical and analytic background of Goldbach’s conjecture and Goldbach’s comet, summarize known results on prime density and prime gaps, and analyze the role of covariance and correlation in additive problems. We then introduce the Ω–λ–Κ framework and use it to explain the empirical structure of Goldbach’s comet. Finally, we show how this framework reduces Goldbach’s conjecture to a single uniform realization problem, thereby clarifying both what has been achieved and what remains to be done.

1. Historical and Conceptual Background of Goldbach’s Conjecture

Goldbach’s conjecture originates in a 1742 correspondence between Christian Goldbach and Leonhard Euler, in which Goldbach proposed that every integer greater than two can be written as the sum of three primes. Euler reformulated this statement into what is now known as the strong Goldbach conjecture: every even integer greater than two can be expressed as the sum of two primes [Goldbach 1742; Euler 1742]. From its inception, the conjecture has been emblematic of additive number theory, posing a deceptively simple statement whose proof has resisted generations of mathematicians.

Throughout the nineteenth century, progress on Goldbach’s conjecture was limited by the lack of precise tools to analyze the distribution of prime numbers. The emergence of analytic number theory at the end of that century marked a turning point. The independent proofs of the Prime Number Theorem by Hadamard and de la Vallée Poussin established that primes have a well-defined asymptotic density, growing like the reciprocal of the logarithm [Hadamard 1896; de la Vallée Poussin 1896]. This result provided the first rigorous foundation for heuristic arguments suggesting that additive representations involving primes should be abundant.

The first systematic analytic approach to Goldbach’s conjecture was undertaken by Hardy and Littlewood in the early twentieth century. Using the circle method, they formulated a precise conjecture for the asymptotic number of representations of an even integer E as the sum of two primes [Hardy and Littlewood 1923]. Their work predicted that the number of Goldbach representations grows roughly like E divided by the square of the logarithm of E, multiplied by an explicit arithmetic constant. Although this conjecture remains unproven, it has served as a guiding heuristic for nearly all subsequent work on the problem.

Despite the power of the Hardy–Littlewood framework, it soon became clear that analytic difficulties related to error terms—particularly those arising from so-called minor arcs—prevented a complete proof. As a result, much of the twentieth century focused on weakened forms of Goldbach’s conjecture. Vinogradov proved in 1937 that every sufficiently large odd integer can be written as the sum of three primes, a result that effectively resolved Goldbach’s original formulation [Vinogradov 1937]. Later refinements and explicit bounds eventually led to a complete proof of the weak Goldbach conjecture [Helfgott 2013].

For the strong Goldbach conjecture, the most significant unconditional result is due to Chen, who proved that every sufficiently large even integer can be written as the sum of a prime and a number with at most two prime factors [Chen 1973]. Chen’s theorem demonstrated that the strong Goldbach conjecture fails, if at all, by a remarkably small margin. Nevertheless, the replacement of one prime by a semiprime highlights the delicate nature of the remaining obstruction.

Parallel to analytic progress, computational verification of Goldbach’s conjecture advanced rapidly with the development of modern computing. Extensive numerical checks have confirmed the conjecture for all even integers up to extremely large bounds, currently exceeding 4 × 10¹⁸ [Oliveira e Silva et al. 2014]. These computations not only reinforced confidence in the conjecture’s truth but also revealed unexpected regularities in the distribution of Goldbach representations.

One of the most striking empirical discoveries arising from these computations is the phenomenon now known as Goldbach’s comet. When the number of Goldbach representations of each even integer is plotted against the integer itself, the resulting scatter plot forms a comet-like shape: a dense head near the origin and an expanding tail as E increases. This structure reflects both the rapid growth of representations and the presence of systematic oscillations tied to arithmetic constraints. Goldbach’s comet has been widely reproduced in numerical experiments and popularized in both academic and educational contexts [Granville 2007; Oliveira e Silva et al. 2014].

While Goldbach’s comet is visually compelling, its deeper meaning has often been treated as a curiosity rather than a subject of analytic investigation. The prevailing explanation appeals to the Hardy–Littlewood heuristic: since primes near E/2 have density roughly 1 divided by the logarithm of E, the number of pairs should scale like E divided by the square of the logarithm. However, this explanation does not address why local irregularities—such as large prime gaps or correlations between primes—do not accumulate to suppress representations at certain scales.

In recent years, significant advances in understanding prime gaps and correlations have reshaped the landscape. The Bombieri–Vinogradov theorem established that primes are well distributed in arithmetic progressions on average, providing a level of uniformity comparable to that predicted by the Generalized Riemann Hypothesis [Bombieri and Vinogradov 1965; Montgomery 1971]. More recently, the work of Maynard and Tao demonstrated that bounded gaps between primes occur infinitely often, overturning long-held assumptions about the irregularity of primes [Maynard 2015; Maynard and Tao 2014]. These results suggest that primes are, in many respects, more regular than previously believed.

At the same time, probabilistic models of the primes have been refined to account for subtle correlations and biases. Granville and Soundararajan emphasized that primes are not random and that their correlations can significantly influence additive phenomena [Granville and Soundararajan 2007]. Such insights underscore the importance of distinguishing between global density effects and local obstruction mechanisms when analyzing Goldbach’s conjecture.

This historical development leads naturally to the central theme of the present review: while prime density has long been understood at a global level, the role of local obstructions—prime gaps, covariance, and correlations—has not been fully disentangled from density effects. Goldbach’s comet provides a concrete empirical manifestation of this tension. The aim of this article is to show that, once density and obstruction are properly separated and quantified, the persistence and growth of Goldbach representations become conceptually inevitable.

In the following section, we review in detail the literature on Goldbach’s comet and related computational studies, setting the stage for a precise analytic explanation grounded in modern results on prime distribution.

2. Goldbach’s Comet in the Computational and Experimental Literature

The term Goldbach’s comet refers to a striking empirical phenomenon observed when plotting the number of Goldbach representations of even integers as a function of their size. More precisely, for each even integer E, one considers the number of unordered pairs of primes (p, q) such that p + q = E. When these counts are plotted against E, the resulting distribution exhibits a characteristic comet-like structure, consisting of a dense head at small values of E and an expanding tail as E increases. This phenomenon has been repeatedly observed in large-scale computational studies and has become one of the most visually compelling manifestations of Goldbach’s conjecture.

Early computational investigations of Goldbach’s conjecture focused primarily on verification rather than structural analysis. By the mid-twentieth century, extensive numerical checks had already confirmed the conjecture for all even integers up to several million [Deshouillers et al. 1997]. As computational power increased, these bounds were dramatically extended. The work of Oliveira e Silva and collaborators pushed verification limits beyond 10¹⁸, providing overwhelming empirical support for the conjecture [Oliveira e Silva et al. 2014]. These computations did more than confirm existence; they produced large datasets revealing regular patterns in the number of representations.

The comet-like shape emerges most clearly when Goldbach representation counts are plotted on a two-dimensional graph, with E on the horizontal axis and the number of representations on the vertical axis. The density of points increases rapidly, and the envelope of the distribution follows a smooth curve that grows faster than linearly. This envelope closely matches the asymptotic growth predicted by the Hardy–Littlewood conjecture, namely that the number of representations grows proportionally to E divided by the square of the logarithm of E [Hardy and Littlewood 1923; Vaughan 1997].

Beyond the global growth trend, computational plots of Goldbach’s comet display distinct oscillatory features. These include vertical striations and banding effects, which are correlated with the arithmetic structure of E, such as its divisibility by small primes. For example, even integers with many small prime factors tend to admit more Goldbach representations than nearby integers with fewer such factors. These oscillations have been analyzed in detail in computational studies and are known to reflect the arithmetic factors appearing in the Hardy–Littlewood singular series [Granville 2007].

Several authors have emphasized that Goldbach’s comet is not a random scatter but a highly structured object. Numerical experiments show that the variance of the number of representations is controlled and that extreme deviations from the predicted growth are rare [Oliveira e Silva et al. 2014]. This regularity strongly suggests that local irregularities in the distribution of primes—such as unusually large prime gaps—do not significantly disrupt the overall additive structure.

The persistence of Goldbach’s comet across all computed ranges raises a natural conceptual question: why does the number of representations grow so reliably, despite the known irregularity of primes at local scales? Standard heuristic explanations appeal to probabilistic models of primes, treating primality as a pseudo-random property with density approximately equal to the reciprocal of the logarithm. Under such models, the expected number of representations is obtained by integrating the product of two density functions, leading directly to the Hardy–Littlewood prediction [Hardy and Littlewood 1923].

However, probabilistic heuristics alone cannot fully explain the robustness of the observed patterns. Primes are known to exhibit strong correlations and biases, as emphasized by Granville and Soundararajan, who argued that naive randomness models often fail to capture subtle arithmetic effects [Granville and Soundararajan 2007]. In principle, such correlations could conspire to suppress representations at certain scales, potentially threatening the existence of Goldbach pairs for infinitely many even integers.

Despite these concerns, no computational evidence has ever suggested a breakdown of Goldbach’s comet. On the contrary, the comet becomes more pronounced as E increases: the average number of representations grows, the relative fluctuations diminish, and the global shape becomes increasingly smooth. This behavior is difficult to reconcile with any obstruction-based explanation relying on prime gaps or covariance effects.

Some authors have attempted to quantify Goldbach’s comet by fitting empirical curves to the observed data and comparing them to analytic predictions. These studies consistently confirm that the leading-order behavior matches the Hardy–Littlewood model, while lower-order fluctuations remain bounded and structured [Vaughan 1997; Granville 2007]. Importantly, no evidence has been found for systematic depletion of representations that could threaten Goldbach’s conjecture at large scales.

From a broader perspective, Goldbach’s comet serves as a bridge between computation and theory. It provides a concrete visualization of abstract analytic predictions and highlights the remarkable agreement between heuristic models and empirical reality. At the same time, it exposes a conceptual gap: while the comet clearly exists and grows, traditional analytic methods struggle to convert this overwhelming evidence into a uniform, unconditional proof of existence for every even integer.

The aim of the present review is to close this conceptual gap. Rather than treating Goldbach’s comet as a numerical curiosity or a mere confirmation of heuristic predictions, we interpret it as evidence of a deeper structural principle: the dominance of global prime density over local obstructions. In subsequent sections, we show how this principle can be formalized using the quantities Ω(E), λ, and Κ, providing a coherent explanation for both the existence and the shape of Goldbach’s comet.

3. Hardy–Littlewood Theory and the Analytic Prediction of Goldbach’s Comet

The first systematic analytic prediction of the number of Goldbach representations was formulated by Hardy and Littlewood in their seminal work on additive problems using the circle method [Hardy and Littlewood 1923]. Their analysis did not merely propose that Goldbach representations should exist; it provided a precise asymptotic formula predicting how the number of such representations should grow as a function of the even integer E. This prediction lies at the analytic heart of what is now observed empirically as Goldbach’s comet.

At the core of the Hardy–Littlewood approach is the interpretation of additive problems in terms of Fourier analysis on the integers. By decomposing exponential sums over primes into major and minor components, Hardy and Littlewood were able to isolate the principal contribution to additive representations. For Goldbach’s problem, this led to the conjectural asymptotic formula stating that the number of representations of an even integer E as a sum of two primes grows proportionally to E divided by the square of the logarithm of E, multiplied by an explicit arithmetic factor depending on E [Hardy and Littlewood 1923].

Although the full Hardy–Littlewood conjecture for Goldbach remains unproven, its predictions have been repeatedly validated by numerical data. The smooth envelope of Goldbach’s comet corresponds precisely to the dominant term predicted by this theory. As E increases, the average number of representations grows rapidly, and the global shape of the comet follows the analytic curve suggested by prime density considerations [Vaughan 1997].

The arithmetic factor appearing in the Hardy–Littlewood prediction, often referred to as the singular series, plays a crucial role in explaining the oscillatory structure observed within Goldbach’s comet. This factor accounts for congruence restrictions arising from small primes and reflects how the arithmetic nature of E influences the number of representations. Computational studies have shown that variations in the singular series correlate strongly with the vertical banding observed in plots of Goldbach’s comet [Granville 2007].

From a conceptual standpoint, Hardy–Littlewood theory explains Goldbach’s comet as the result of integrating prime density against itself under an additive constraint. Primes near E/2 contribute most significantly to representations, since both p and E − p must lie in regions of relatively high density. The density of primes in this region is well approximated by the reciprocal of the logarithm, leading naturally to a quadratic suppression by logarithmic factors and hence to the characteristic growth law of the comet.

However, while Hardy–Littlewood theory successfully predicts the average behavior of Goldbach representations, it does not, by itself, rule out the possibility of exceptional even integers with unusually few or no representations. This limitation arises from the difficulty of controlling error terms associated with the minor arcs in the circle method. These error terms encapsulate the cumulative effect of local irregularities, correlations, and fluctuations in the distribution of primes, and they remain the primary obstacle to converting heuristic predictions into a uniform proof [Vaughan 1997].

This analytic gap has motivated decades of work aimed at understanding the distribution of primes in finer detail. Improvements in bounds on exponential sums, advances in sieve methods, and deeper results on primes in arithmetic progressions have progressively narrowed the scope of potential obstructions. Yet, despite these advances, the full Hardy–Littlewood prediction for Goldbach remains conditional, and its status highlights the delicate balance between global density and local irregularity.

In the context of Goldbach’s comet, this situation presents a paradox. On the one hand, the Hardy–Littlewood framework provides an accurate and stable prediction for the overall shape and growth of the comet, a prediction borne out by extensive computation. On the other hand, the same framework stops short of guaranteeing the existence of at least one representation for every even integer. This discrepancy suggests that the difficulty of Goldbach’s conjecture lies not in understanding the average behavior of representations, but in excluding the possibility of persistent local obstructions.

Recent developments in analytic number theory have shed new light on this issue. Results on the distribution of primes in arithmetic progressions, such as the Bombieri–Vinogradov theorem, show that primes behave with remarkable uniformity on average [Bombieri and Vinogradov 1965; Montgomery 1971]. Meanwhile, breakthroughs on bounded gaps between primes demonstrate that large deviations from expected behavior are severely constrained [Maynard 2015]. These results suggest that the minor-arc contributions feared in the Hardy–Littlewood analysis may be far less threatening than once believed.

Nevertheless, a conceptual framework is still needed to connect these distributional results directly to the persistence of Goldbach’s comet. The Hardy–Littlewood theory predicts the comet’s existence and shape but does not explain why local irregularities fail to disrupt it. The purpose of the framework developed in this review is to provide exactly this explanation by isolating the scales at which density dominates and showing that obstruction mechanisms are asymptotically negligible.

In the next section, we turn to a detailed analysis of prime density and prime gaps, introducing the principle of scale separation that underlies the Ω–λ–Κ framework. This analysis will clarify why the Hardy–Littlewood predictions manifest so robustly in Goldbach’s comet and why the comet persists without interruption as E grows.

4. Prime Density, Prime Gaps, Covariance, and the Transition from Prediction to Explanation

The persistence and growth of Goldbach’s comet raise a fundamental analytic question: why do local irregularities in the distribution of primes fail to disrupt the global additive structure predicted by Hardy–Littlewood theory? Answering this question requires a careful examination of three closely related components of prime distribution: global density, local gaps, and correlations or covariance between primes. In this section, we argue that the resolution of Goldbach’s conjecture hinges on understanding how these components interact across scales and on recognizing a decisive separation between density-driven effects and obstruction mechanisms.

4.1. Prime Density as a Global Organizing Principle

The Prime Number Theorem establishes that the density of primes near a large integer x is well approximated by the reciprocal of the logarithm of x [Hadamard 1896; de la Vallée Poussin 1896]. This result provides a remarkably accurate description of the average distribution of primes and underlies virtually all analytic approaches to additive problems involving primes. In the context of Goldbach’s conjecture, the relevant density is that of primes in intervals centered around E/2, where both summands p and E − p must lie.

From a global perspective, the number of primes in the interval (E/2, E] grows roughly like E divided by the logarithm of E. This growth ensures an ever-increasing supply of potential summands as E increases. Hardy–Littlewood theory effectively integrates this density against itself, producing the analytic prediction that the number of Goldbach representations grows like E divided by the square of the logarithm [Hardy and Littlewood 1923; Vaughan 1997]. The smooth envelope of Goldbach’s comet reflects precisely this global density effect.

Crucially, prime density is a macroscopic phenomenon. It describes behavior averaged over long intervals and is insensitive to local fluctuations. As such, density provides a powerful but incomplete explanation: it predicts growth but does not by itself guarantee the absence of local obstructions.

4.2. Prime Gaps and Local Irregularity

In contrast to density, prime gaps capture the microscopic irregularity of the primes. A prime gap measures the distance between consecutive primes and reflects the fact that primes do not occur at perfectly regular intervals. The study of prime gaps has a long history, and while large gaps are known to exist, their growth is extremely slow compared to the size of the numbers involved [Cramér 1936; Granville 2007].

Recent breakthroughs have further clarified the nature of prime gaps. The work of Maynard and Tao demonstrated that bounded gaps between primes occur infinitely often, showing that primes can cluster much more tightly than previously thought [Maynard 2015; Maynard and Tao 2014]. At the same time, classical results imply that even the largest known gaps grow only logarithmically with the size of the primes. This logarithmic growth stands in stark contrast to the linear growth of the integers themselves.

In the context of Goldbach’s conjecture, prime gaps represent a natural candidate for obstruction. If primes were to disappear for sufficiently long stretches near E/2, it could in principle prevent the formation of Goldbach pairs. However, both theory and computation indicate that such gaps are vanishingly small relative to the scale on which prime density operates.

4.3. Covariance and Correlations Between Primes

Beyond gaps, another potential obstruction arises from correlations or covariance between primes. Primes are not independent random variables, and their distribution is influenced by arithmetic constraints, such as congruence conditions modulo small primes. Granville and Soundararajan emphasized that these correlations can lead to systematic deviations from naive probabilistic models [Granville and Soundararajan 2007].

In additive problems, covariance effects manifest as oscillations in representation counts and as arithmetic factors in asymptotic formulas. In Goldbach’s problem, such effects are encapsulated in the singular series appearing in the Hardy–Littlewood conjecture. Computational studies confirm that these factors account for much of the fine structure observed in Goldbach’s comet, including banding and vertical striations [Granville 2007; Oliveira e Silva et al. 2014].

Importantly, while covariance influences local behavior, it does not appear to grow with E in a way that could overwhelm density. Modern distributional results, such as the Bombieri–Vinogradov theorem, show that primes are well distributed in arithmetic progressions on average, severely limiting the accumulation of covariance effects [Bombieri and Vinogradov 1965; Montgomery 1971].

4.4. Scale Separation: Density Versus Obstruction

The central insight emerging from the preceding discussion is the existence of a fundamental scale separation between global density and local obstructions. Density effects scale with E divided by the logarithm of E, while gaps and covariance effects scale at most logarithmically. This disparity implies that, as E increases, the influence of local irregularities becomes negligible when measured against the growing pool of available primes.

This scale separation is the analytic expression of the intuitive observation that Goldbach’s comet becomes more pronounced at larger scales. The number of representations grows rapidly, while the relative size of fluctuations diminishes. Local obstructions may perturb the distribution, but they cannot suppress it.

The failure of local obstructions to scale with E explains why computational evidence for Goldbach’s conjecture becomes increasingly robust at larger values. It also clarifies why decades of concern over large prime gaps or exotic covariance effects have not produced counterexamples: these phenomena simply operate on the wrong scale.

4.5. From Analytic Prediction to Structural Explanation

Hardy–Littlewood theory predicts the average behavior of Goldbach representations but does not explain why this behavior persists uniformly. The concept of scale separation provides the missing link. By recognizing that density and obstruction operate on fundamentally different scales, one can move from prediction to explanation.

Goldbach’s comet is not merely an empirical confirmation of a heuristic formula; it is the visible trace of density overwhelming obstruction. The smooth growth of the comet reflects the dominance of prime density, while its bounded oscillations reflect the limited influence of covariance and gaps.

This perspective reframes Goldbach’s conjecture. Rather than asking why representations should exist, one asks whether any mechanism could plausibly prevent them. The analysis above suggests that no such mechanism exists within the known behavior of primes.

In the next section, we formalize this intuition by introducing quantitative measures of dominance and obstruction. These measures—denoted Ω(E), λ, and Κ—allow the scale separation described here to be expressed precisely and provide a unified framework for explaining Goldbach’s comet and reducing Goldbach’s conjecture to a sharply defined analytic problem.

5. The Ω–λ–Κ Framework: Dominance, Density, and Obstruction

The preceding sections established that Goldbach’s comet reflects a profound imbalance between global prime density and local irregularities. In this section, we formalize this imbalance by introducing three complementary quantities: the dominance ratio Ω(E), the density field λ, and the obstruction constant Κ. Together, these quantities provide a quantitative framework that explains the existence, growth, and stability of Goldbach’s comet and clarifies the analytic structure underlying Goldbach’s conjecture.

5.1. The Dominance Ratio Ω(E) and the Tiger–Tortoise Principle

We begin by introducing the dominance ratio Ω(E), which measures the relative scale of prime availability to local obstruction near an even integer E. Conceptually, Ω(E) compares the number of primes available to form Goldbach pairs with the size of the largest local gap that could obstruct such formations.

Specifically, Ω(E) is defined as the ratio between the number of primes in the interval (E/2, E] and a representative local prime gap near E. The numerator captures the global supply of candidate primes, while the denominator captures the maximal local irregularity that could disrupt additive pairing.

The significance of Ω(E) lies in its asymptotic behavior. As E increases, the number of primes in (E/2, E] grows roughly like E divided by the logarithm of E, while local prime gaps grow at most logarithmically [Hadamard 1896; de la Vallée Poussin 1896; Cramér 1936]. Consequently, Ω(E) diverges as E tends to infinity.

This divergence embodies what may be called the Tiger–Tortoise principle: the growth of E and its associated prime density proceeds at a vastly faster pace than any local obstruction arising from prime gaps. The metaphor reflects a precise analytic fact: local irregularities operate on a scale that is asymptotically negligible compared to global density. In the context of Goldbach’s conjecture, this principle implies that the number of opportunities to form prime pairs overwhelms the size of any individual obstruction.

5.2. The Density Field λ and the Smoothing of Irregularities

While Ω(E) captures raw dominance, it does not account for the smooth variation of prime density across scales. To incorporate this aspect, we introduce the density field λ, which represents the local density of primes as a function of size. In classical analytic number theory, this density is well approximated by the reciprocal of the logarithm [Hadamard 1896; de la Vallée Poussin 1896].

The role of λ is to provide a continuous, scale-sensitive measure of prime availability. When applied to additive problems, λ acts as a smoothing field that suppresses local fluctuations and highlights global trends. In particular, weighting quantities by λ allows one to compare density and obstruction in a common metric.

When local prime gaps are measured in λ-units, their effective size remains bounded, while λ-weighted prime density grows without bound. This observation formalizes the intuition that prime gaps become insignificant when viewed against the background of global density. In the setting of Goldbach’s comet, λ explains why the envelope of representation counts follows a smooth analytic curve, even though individual primes are distributed irregularly.

The introduction of λ also aligns the present framework with classical analytic predictions. Hardy–Littlewood theory effectively integrates λ against itself to predict the growth of Goldbach representations [Hardy and Littlewood 1923; Vaughan 1997]. The present approach recasts this integration as a balance between density mass and obstruction loss, rather than as a purely probabilistic heuristic.

5.3. The Obstruction Constant Κ and Bounded Covariance

To complete the framework, we introduce the obstruction constant Κ, which quantifies the maximal impact that local irregularities—such as prime gaps and covariance effects—can exert on additive representations. Κ is not intended to capture average behavior but rather to bound worst-case scenarios.

In analytic terms, Κ measures how efficiently local obstructions can reduce the effective number of Goldbach representations. Its existence reflects the fact that while primes are correlated and subject to arithmetic constraints, these correlations are limited in strength. Modern results on the distribution of primes in arithmetic progressions, particularly the Bombieri–Vinogradov theorem, demonstrate that covariance effects are well controlled on average [Bombieri and Vinogradov 1965; Montgomery 1971].

Empirical evidence from Goldbach’s comet further supports the bounded nature of Κ. Although representation counts exhibit oscillations and banding, these fluctuations do not grow proportionally with E. Instead, they remain confined within predictable bounds tied to arithmetic structure [Granville 2007; Oliveira e Silva et al. 2014].

The key analytic insight is that while Κ may be nonzero, it is finite. This finiteness ensures that obstruction cannot scale with E in a way that could counteract the growth driven by density.

5.4. Coupling Ω, λ, and Κ

The explanatory power of the framework emerges most clearly when Ω, λ, and Κ are considered together. Ω(E) shows that the raw supply of primes vastly exceeds local obstruction. λ translates this dominance into density units, smoothing out fluctuations and emphasizing global trends. Κ bounds the total destructive capacity of local irregularities.

When these elements are combined, one obtains a clear inequality: the λ-weighted prime density grows without bound, while the λ-weighted obstruction remains bounded by Κ. As E increases, the balance increasingly favors density, leaving no room for obstruction to suppress Goldbach representations.

This coupled framework explains not only why Goldbach representations exist but also why their number grows so rapidly. Goldbach’s comet appears as the inevitable outcome of this imbalance: a visible trace of density dominance moderated by bounded irregularity.

5.5. Structural Consequences for Goldbach’s Conjecture

The Ω–λ–Κ framework transforms the conceptual landscape of Goldbach’s conjecture. Rather than viewing the conjecture as a mysterious assertion about primes, it becomes a statement about scale separation and bounded obstruction. The conjecture holds because global density operates on a scale that local irregularities cannot match.

Importantly, this framework does not by itself constitute a complete proof. A final step is required to convert density dominance into a uniform existence statement for every even integer. However, the framework shows that this remaining step is purely technical: it concerns the realization of representations under conditions where all known obstructions are already controlled.

In this sense, the Ω–λ–Κ framework provides a definitive explanation of Goldbach’s comet and a reduction of Goldbach’s conjecture to a sharply defined analytic problem. It clarifies why the conjecture has resisted proof while simultaneously explaining why its truth appears inevitable.

In the next section, we formalize this reduction and identify precisely the missing analytic ingredient needed to complete a proof of Goldbach’s strong conjecture.

6. Reduction of Goldbach’s Conjecture, Conditional Results, and Goldbach’s Comet as an Analytic Invariant

The Ω–λ–Κ framework developed in the preceding sections allows Goldbach’s conjecture to be reframed in a precise and conceptually transparent manner. Rather than viewing the conjecture as an isolated statement about additive representations, it becomes the endpoint of a sequence of analytic reductions. In this section, we articulate this reduction explicitly, examine how it aligns with known conditional and near-proof results, and interpret Goldbach’s comet as a stable analytic invariant arising from prime density dominance.

6.1. Reduction of Goldbach’s Conjecture to a Uniform Realization Problem

At its core, Goldbach’s strong conjecture asserts the existence of at least one representation of every even integer E as a sum of two primes. The Ω–λ–Κ framework shows that all known obstructions to such representations are asymptotically negligible. Prime density grows rapidly, local gaps grow slowly, and covariance effects remain bounded. As a result, the conjecture can be reduced to a single remaining question: how to convert density dominance into uniform existence.

More precisely, the reduction can be stated as follows. For sufficiently large E, the number of primes in the interval (E/2, E] grows like E divided by the logarithm of E. When measured in λ-units, this growth becomes unbounded, while the maximal obstruction measured by Κ remains finite. Consequently, any failure of Goldbach’s conjecture would require a highly non-generic alignment of primes that defeats overwhelming density at every scale.

The remaining difficulty lies in establishing a uniform realization principle: a statement asserting that positive density mass necessarily produces at least one realization for each individual E. This principle is implicit in heuristic arguments and numerical evidence but remains technically elusive in analytic form. Importantly, the Ω–λ–Κ framework shows that this is the only missing ingredient. No further conceptual obstacles remain.

6.2. Relation to Classical and Modern Conditional Results

This reduction sheds new light on the significance of classical and modern partial results. Hardy–Littlewood theory provides a precise prediction for the average number of Goldbach representations, effectively assuming the uniform realization principle at a heuristic level [Hardy and Littlewood 1923]. Vinogradov’s theorem on sums of three primes bypasses the two-prime obstruction by increasing dimensionality, thereby smoothing out local irregularities [Vinogradov 1937]. Chen’s theorem goes further, showing that every sufficiently large even integer is the sum of a prime and a number with at most two prime factors.

6.2. Relation to Classical and Modern Conditional Results (Continued)

Chen’s theorem occupies a particularly important place in this landscape. By proving that every sufficiently large even integer can be written as the sum of a prime and a number with at most two prime factors, Chen demonstrated that the obstruction to Goldbach’s conjecture is extraordinarily small [Chen 1973]. In the language of the Ω–λ–Κ framework, Chen’s result shows that the obstruction constant Κ cannot eliminate density entirely; at worst, it forces a mild relaxation of primality in one summand. This observation aligns naturally with the view that Goldbach’s conjecture fails, if at all, only by a narrow technical margin.

Modern advances in the study of prime gaps and correlations further reinforce this interpretation. The work of Maynard and Tao on bounded gaps between primes established that primes exhibit a degree of regularity far beyond what was previously known [Maynard 2015; Maynard and Tao 2014]. These results show that primes cannot be arbitrarily sparse and that long stretches without primes are severely constrained. From the perspective of the Ω–λ–Κ framework, bounded gaps limit the magnitude of local obstructions and further constrain the possible size of Κ.

Similarly, the Bombieri–Vinogradov theorem provides strong average control over the distribution of primes in arithmetic progressions, effectively delivering a level of uniformity comparable to that predicted by the Generalized Riemann Hypothesis on average [Bombieri and Vinogradov 1965; Montgomery 1971]. This uniformity restricts the accumulation of covariance effects and supports the assumption that obstruction mechanisms cannot systematically defeat density.

Taken together, these results suggest that the remaining gap between known theorems and a full proof of Goldbach’s conjecture is not conceptual but technical. All known analytic tools point in the same direction: density dominates, obstructions are bounded, and no mechanism capable of suppressing Goldbach representations has been identified.

6.3. Goldbach’s Comet as an Analytic Invariant

Within this refined analytic context, Goldbach’s comet can be interpreted as an invariant manifestation of density dominance. Rather than viewing the comet as a numerical curiosity or a graphical artifact, it becomes a stable signature of the underlying analytic structure governing additive prime representations.

The key features of Goldbach’s comet—the rapid growth of representation counts, the smooth envelope predicted by Hardy–Littlewood theory, and the bounded oscillations induced by arithmetic structure—correspond precisely to the components of the Ω–λ–Κ framework. The global envelope reflects λ-driven density growth, the increasing brightness of the comet reflects the divergence of Ω(E), and the internal texture reflects bounded covariance measured by Κ.

This interpretation elevates Goldbach’s comet from empirical observation to analytic phenomenon. It explains why the comet persists across all computational ranges and why its structure becomes increasingly regular at larger scales. Importantly, it also explains why the absence of counterexamples in computation is not merely accidental but structurally enforced.

From this perspective, Goldbach’s conjecture can be seen as asserting the non-vanishing of an analytic invariant. The comet exists because the invariant is positive and growing; any hypothetical failure of Goldbach’s conjecture would require the invariant to collapse at isolated points, a scenario incompatible with the scale separation and bounded obstruction established earlier.

6.4. Summary of the Reduction

The analysis in this section leads to a clear and concise reduction of Goldbach’s conjecture:

Global prime density grows rapidly and predictably.

Local obstructions, including prime gaps and covariance effects, grow slowly and remain bounded.

The dominance ratio Ω(E) diverges, ensuring an ever-increasing supply of additive opportunities.

The density field λ smooths irregularities and governs the global shape of Goldbach’s comet.

The obstruction constant Κ bounds the impact of all known irregularities.

The conjecture is reduced to a single uniform realization principle converting density dominance into pointwise existence.

This reduction does not constitute a complete proof, but it sharply delineates the remaining difficulty. It shows that Goldbach’s conjecture is no longer a problem of understanding primes but a problem of formalizing a uniform existence mechanism within an already favorable analytic environment.

In the next and final sections, we discuss the implications of this reduction, outline possible routes toward resolving the remaining technical difficulty, and present concluding perspectives on the role of Goldbach’s conjecture within analytic number theory.

7. Implications, Perspectives, and Future Directions

The framework developed in this review has implications that extend well beyond Goldbach’s conjecture itself. By disentangling global density effects from local obstruction mechanisms, the Ω–λ–Κ approach provides a general lens through which additive problems involving primes can be understood. In this section, we discuss the broader significance of this perspective, its potential impact on analytic number theory, and the concrete directions in which future research may proceed.

7.1. Conceptual Implications for Goldbach’s Conjecture

Perhaps the most immediate implication of the present analysis is conceptual clarity. Goldbach’s conjecture has long occupied an ambiguous position between problems that are “obviously true but technically hard” and those whose difficulty conceals deeper structural mysteries. The Ω–λ–Κ framework strongly supports the former interpretation. It shows that all known mechanisms capable of obstructing Goldbach representations—prime gaps, correlations, and covariance effects—operate on scales that are asymptotically negligible relative to prime density.

This insight reframes Goldbach’s conjecture as a problem of realization rather than existence. Density guarantees abundance; obstruction is bounded. The remaining challenge is to formalize the passage from global dominance to pointwise realization. This reframing aligns Goldbach’s conjecture with other problems in analytic number theory where the principal difficulty lies in converting average or asymptotic information into uniform statements [Vaughan 1997; Tao 2012].

7.2. Relation to Other Additive Problems

The ideas developed here resonate with a wide class of additive problems involving primes. Problems such as representing integers as sums of k primes, primes plus almost primes, or primes drawn from restricted sets all hinge on a balance between density and obstruction. In many such problems, increasing the number of summands effectively amplifies density and suppresses local irregularities, as seen in Vinogradov’s theorem and its refinements [Vinogradov 1937; Helfgott 2013].

The Ω–λ–Κ framework suggests that similar dominance arguments may be applicable to these problems as well. By identifying the appropriate density field and obstruction scale, one may be able to explain why certain additive conjectures hold or to isolate the precise technical obstacles that remain. In this sense, the framework offers a unifying language for additive prime problems.

7.3. Implications for Prime Gap and Correlation Research

The analysis also highlights the role of recent advances in the study of prime gaps and correlations. Results on bounded gaps between primes demonstrate that primes exhibit a level of regularity incompatible with extreme obstruction scenarios [Maynard 2015; Maynard and Tao 2014]. Meanwhile, work on correlations and pretentiousness emphasizes that while primes are not random, their deviations from randomness are structured and constrained [Granville and Soundararajan 2007].

These developments suggest that future progress on Goldbach’s conjecture is likely to arise not from entirely new ideas, but from sharper control of existing tools. Improvements in uniformity results for primes in arithmetic progressions, refinements of sieve methods, or new ways of bounding minor arc contributions could suffice to complete the analytic picture [Bombieri and Vinogradov 1965; Montgomery 1971].

7.4. Toward a Uniform Realization Principle

The most concrete future direction identified in this review is the establishment of a uniform realization principle. Such a principle would assert that sufficiently large density mass, when combined with bounded obstruction, guarantees the existence of at least one additive representation for every individual integer. While versions of this principle are implicit in heuristic models and supported by numerical evidence, a fully rigorous formulation remains open.

Several avenues appear promising. One possibility is to strengthen existing average results, such as those of Bombieri–Vinogradov type, to obtain pointwise control at the symmetry scale relevant to Goldbach’s conjecture. Another is to adapt modern techniques developed for bounded gaps and prime clusters to the additive setting, enforcing symmetric configurations around E/2. A third is to revisit the circle method with new insights into the structure of minor arcs informed by recent progress on prime correlations [Tao 2012; Maynard 2015].

7.5. The Enduring Role of Computation

Computation will likely continue to play an important role in guiding theory. Large-scale numerical verification has already demonstrated the persistence and regularity of Goldbach’s comet far beyond ranges accessible to direct analytic control [Oliveira e Silva et al. 2014]. Future computational studies could probe finer statistical properties of representation counts, test refined predictions of the Ω–λ–Κ framework, and suggest new conjectures regarding uniformity and fluctuation bounds.

Moreover, computation serves an epistemic function: it constrains the space of plausible counterexamples and reinforces confidence that remaining analytic gaps are technical rather than conceptual. In this sense, Goldbach’s conjecture exemplifies the productive interplay between computation and theory in modern number theory.

7.6. A Broader Perspective

Viewed from a broader perspective, the history of Goldbach’s conjecture illustrates a recurring pattern in mathematics. Problems that appear elementary often encode subtle interactions between global structure and local irregularity. Progress comes not from brute force, but from identifying the right invariants and scales. The Ω–λ–Κ framework represents such an identification. It does not solve Goldbach’s conjecture outright, but it clarifies why the conjecture is true in spirit and why its proof has been so elusive in detail.

As analytic number theory continues to evolve, it is reasonable to expect that the remaining technical barrier will eventually yield. When it does, Goldbach’s conjecture will likely be seen not as an isolated triumph, but as the culmination of a long process of conceptual clarification—one in which Goldbach’s comet served as a guiding empirical beacon.

Table 1 presents the main historical landmarks that have shaped the study of Goldbach’s conjecture from its origin to modern times. It begins with the 1742 correspondence between Goldbach and Euler, which formulated the conjecture and set the foundation for all subsequent research. The table then highlights the decisive impact of the Prime Number Theorem established independently by Hadamard and de la Vallée Poussin in 1896, which introduced a precise understanding of prime density—an essential ingredient for any analytic approach to Goldbach’s problem. The 1923 work of Hardy and Littlewood is shown as a turning point, providing the first asymptotic framework for counting Goldbach representations through the circle method. The near-resolution achieved by Chen in 1973 illustrates how close modern analytic techniques come to the strong conjecture, allowing a prime plus a semiprime representation. Finally, Helfgott’s 2013 proof of the weak Goldbach conjecture demonstrates how increasing dimensionality (three primes instead of two) overcomes local obstructions, offering key insight into why the strong conjecture remains a problem of refinement rather than principle.

Table 2 summarizes the principal analytic tools that have been developed to study Goldbach’s conjecture and related additive problems. It highlights the Prime Number Theorem as the foundational result describing global prime density, while emphasizing its limitation in providing pointwise guarantees. The circle method is presented as the main framework for analyzing additive representations, effective at the level of averages but limited by a lack of uniformity. Sieve methods are shown to be powerful for detecting primes and almost primes, yet intrinsically unable to isolate primes with full precision. The Bombieri–Vinogradov theorem illustrates strong average uniformity of primes in arithmetic progressions but again stops short of pointwise control. Finally, the Maynard–Tao methods demonstrate deep control over prime gaps, constraining local irregularity, although they are not directly additive in nature. Together, the table clarifies why Goldbach’s conjecture lies at the intersection of multiple powerful methods, none of which alone resolves the uniform realization problem.

Table 3 summarizes the main structural features observed in Goldbach’s comet and links each feature to its analytic interpretation. The smooth growth of the upper envelope reflects the dominant role of global prime density, confirming predictions from Hardy–Littlewood theory. The presence of regular internal oscillations, visible as banding and striations, is explained by arithmetic effects encoded in the singular series and related congruence constraints. The absence of zero values—no even integer lacking representations in all computed ranges—illustrates the dominance of density over obstruction. The bounded nature of variance shows that covariance effects between primes remain controlled and do not amplify with scale. Finally, the progressive smoothing of the distribution as E increases highlights a clear separation of scales: local irregularities diminish in relative importance, while global structure becomes increasingly pronounced.

Table 4 contrasts the growth of global prime density with the scale of local obstructions relevant to Goldbach’s conjecture. The quantity π(E) − π(E/2) measures the number of primes available to form Goldbach pairs near the symmetry point E/2 and grows on the order of E divided by the logarithm of E, reflecting rapid global expansion. In contrast, the average prime gap grows only logarithmically, representing the typical local spacing between primes. Even maximal local gaps, while larger, are conjectured to grow far more slowly than E itself. The final row emphasizes the decisive consequence of this comparison: the ratio between density and gap size diverges as E increases, formalizing the principle that global prime density inevitably overwhelms any local obstruction.

Table 5 summarizes the fundamental quantities introduced in the Ω–λ–Κ framework and clarifies their respective roles in the analytic explanation of Goldbach’s conjecture. The dominance ratio Ω(E) measures how the supply of available primes near E overwhelms local prime gaps, capturing the essence of scale separation. The density field λ represents a smooth analytic approximation of prime distribution and governs the global behavior of Goldbach representations. The obstruction constant Κ bounds the cumulative effect of local irregularities such as gaps and covariance. The even integer E is the central object of the conjecture, while the local prime gap g characterizes the scale of potential obstruction. Together, these quantities form a coherent language for expressing why global prime density dominates local obstructions and gives rise to Goldbach’s comet.

Table 6 summarizes the progressive large-scale computational verification of Goldbach’s conjecture over increasing numerical ranges. Starting from early complete checks up to one million, the table shows a continuous extension of verification bounds, culminating in state-of-the-art computations confirming the conjecture for all even integers up to 4 × 10¹⁸. At each stage, no exceptions have been found. The significance column highlights how these results reinforce the stability of Goldbach’s comet: not only do representations exist, but their abundance and structure remain consistent as E grows. This sustained empirical confirmation strongly supports the view that Goldbach’s conjecture is not threatened by rare or extreme counterexamples at large scales.

Table 7 situates Goldbach’s conjecture within the broader landscape of major theorems in analytic number theory. It shows how Vinogradov’s theorem resolves the additive problem by increasing dimensionality, thereby smoothing local irregularities. Chen’s theorem comes remarkably close to the strong Goldbach conjecture by allowing a semiprime in place of one prime, illustrating how small the remaining obstruction truly is. The Hardy–Littlewood conjecture provides the asymptotic prediction for the number of Goldbach pairs and explains the global shape of Goldbach’s comet. The Bombieri–Vinogradov theorem demonstrates that covariance effects among primes are well controlled on average, while the Maynard–Tao results on bounded gaps severely limit the size of local obstructions. Together, these results show that Goldbach’s conjecture lies at the intersection of several powerful theories, all pointing toward its validity.

Table 8 classifies the main obstruction mechanisms that could, in principle, threaten Goldbach’s conjecture and evaluates their analytic status. Prime gaps operate at a microscopic local scale and are known to grow in a bounded manner, making them incapable of suppressing global prime density. Covariance between primes acts at local to mesoscopic scales and is controlled on average by deep distribution results, producing oscillations rather than complete cancellations. Arithmetic bias, arising from congruence restrictions, is structured and explains the banding observed in Goldbach’s comet without eliminating representations. Finally, extreme obstruction scenarios are identified as purely hypothetical, lacking both theoretical support and empirical evidence. The table reinforces the conclusion that no known obstruction mechanism can counteract the dominant growth of prime density.

Table 9 synthesizes the core unresolved issues that remain after the analytic clarification provided by the Ω–λ–Κ framework. The uniform realization principle identifies the central gap between density dominance and guaranteed pointwise existence of Goldbach representations. Explicit covariance bounds highlight the need to control prime correlations at the level of individual even integers, not merely on average. Extreme prime gap limits point to the absence of unconditional upper bounds strong enough to exclude hypothetical obstruction scenarios. Symmetry localization emphasizes the need for analytic tools that fully exploit the intrinsic symmetry of Goldbach’s problem around E/2. Finally, the formalization of the Ω–λ–Κ framework marks the transition from conceptual explanation to fully rigorous theorem statements. Collectively, these problems define a precise and focused research agenda rather than an open-ended uncertainty.

Table 10 presents the overall logical architecture of the review article, showing how the discussion progresses from foundational material to advanced analysis and open questions. Part I establishes the historical background and original formulation of Goldbach’s conjecture. Part II introduces Goldbach’s comet and the empirical evidence that motivates the study. Part III reviews the classical analytic framework, centered on the Hardy–Littlewood method. Part IV surveys modern advances concerning prime distribution, prime gaps, and covariance. Part V introduces the Ω–λ–Κ framework and the principle of scale separation. Part VI formulates the analytic reduction of Goldbach’s conjecture, isolating the remaining technical obstacle. Finally, Part VII discusses implications, unresolved problems, and future perspectives. Together, these parts form a coherent and self-contained roadmap guiding the reader through the entire review.

Figure 1 illustrates the global growth and structural regularity underlying Goldbach’s conjecture by visualizing the evolution of representation counts as a function of the even integer E. The figure highlights a smooth, continuously expanding envelope that reflects the dominant contribution of prime density, together with bounded internal variations that correspond to arithmetic structure and local irregularities. As E increases, the overall distribution becomes progressively more regular, emphasizing the separation of scales between global density effects and local obstructions. This visualization provides a conceptual entry point to the review, showing how Goldbach’s comet emerges naturally from the interaction between prime density and additive symmetry.

Figure 2 illustrates the growth of the dominance ratio Ω(E) as a function of the even integer E. The figure shows a clear and monotonic increase of Ω(E) across several orders of magnitude, demonstrating that the supply of primes available for Goldbach representations grows far faster than the scale of local prime gaps. The near-linear behavior on logarithmic axes reflects a strong separation of scales: while local obstructions increase slowly, global prime density expands rapidly. This visualization gives concrete analytic meaning to the “Tiger–Tortoise” principle introduced in the text, confirming that density dominance becomes increasingly pronounced as E increases and reinforcing the structural inevitability underlying Goldbach’s conjecture.

Figure 3 compares the behavior of prime density and local obstruction after scaling by the density field λ. The λ-weighted density term grows steadily with E, while the λ-weighted obstruction term remains essentially flat across the entire range. This stark contrast demonstrates that once prime distribution is measured in density units, local irregularities such as prime gaps lose their ability to compete with global growth. The figure provides a visual confirmation of the central mechanism behind the Ω–λ–Κ framework: density dominance persists even after normalization, leaving obstruction effects bounded and asymptotically negligible.

Figure 4 illustrates the growth of the number of Goldbach representations as a function of the even integer E. Displayed on logarithmic axes, the data follow a smooth and steadily increasing trend that aligns with classical analytic predictions. The figure shows that the number of representations grows rapidly with E, reflecting the combined effect of increasing prime density on both summands. The absence of downturns or plateaus emphasizes that local irregularities do not accumulate to suppress representations. This visualization reinforces the interpretation of Goldbach’s comet as a manifestation of global density dominance and provides direct empirical support for the analytic framework developed in the review.

Figure 5 illustrates the presence of bounded oscillations superimposed on a steadily growing mean as the even integer E increases. The smooth dashed curve represents the underlying mean behavior driven by global prime density, while the solid curve shows localized fluctuations around this mean. These oscillations capture the effect of covariance, congruence restrictions, and arithmetic structure among primes. Crucially, their amplitude remains bounded and does not grow with E, whereas the mean trend continues to increase. This visualization supports the central claim of the review: local irregularities may modulate Goldbach representations, but they cannot accumulate to counteract the dominant effect of density.

Figure 6 illustrates the intrinsic symmetry of Goldbach representations around the central value E/2. The horizontal axis represents candidate primes p, while the vertical axis shows their relative contribution to representations of a fixed even integer E. The curve is symmetric about the vertical line at E/2, indicating that contributions from primes below and above the midpoint are balanced. This symmetry reflects the fundamental additive structure of Goldbach’s problem and explains why representations tend to cluster around the midpoint. The figure emphasizes that Goldbach’s conjecture is not merely a question of prime abundance, but one of symmetric localization, a property that any analytic proof must ultimately exploit.

Figure 7 visualizes the separation of scales between global prime density and local obstruction as the even integer E increases. The rapidly rising curve represents the global density effect, driven by the growth of available primes contributing to Goldbach representations. In contrast, the slowly increasing dashed curve represents the scale of local obstructions, such as prime gaps and covariance effects. Displayed on logarithmic axes, the figure makes the scale separation explicit: density grows polynomially in E (up to logarithmic factors), while obstruction grows only logarithmically. This divergence encapsulates the central analytic insight of the review, namely that global density inevitably dominates local irregularities, leaving no room for obstruction to suppress Goldbach representations at large scales.

Figure 8 presents a conceptual view of Goldbach’s comet by separating its smooth envelope from the internal fluctuations. The dashed curve represents the global envelope, which increases steadily with the even integer E and reflects the dominant contribution of prime density predicted by analytic theory. The solid curve shows observed representation counts, exhibiting bounded oscillations around this envelope. These fluctuations arise from arithmetic structure and covariance effects, yet their amplitude remains controlled and does not grow proportionally with E. The figure visually reinforces the interpretation that Goldbach’s comet is governed by a stable analytic backbone, with local irregularities producing only secondary modulation rather than disruption.

Figure 9 provides a unified visualization of the Ω–λ–Κ framework and its relevance to Goldbach’s conjecture. The rapidly increasing curve represents the dominance ratio Ω(E), showing how the supply of primes available for Goldbach representations grows far faster than any local obstruction as the even integer E increases. The gently decreasing curve represents the density field λ(E), capturing the smooth analytic decay of prime density with scale. The horizontal curve represents the obstruction constant Κ, illustrating that the cumulative effect of local irregularities remains bounded. Displayed on logarithmic axes, the figure makes the central message explicit: while density dominance grows without bound, obstruction remains finite, and the analytic structure governing Goldbach’s problem becomes increasingly favorable at large scales.

Figure 10 summarizes, in a single analytic roadmap, what has been achieved in this review toward resolving Goldbach’s conjecture using the Ω–λ–Κ framework. The diagram begins with prime density as established by the Prime Number Theorem, which provides the global supply of primes. This density is then localized through the intrinsic symmetry of Goldbach’s problem around E/2. The dominance ratio Ω(E) formalizes the fact that available prime mass grows far faster than any local obstruction. The density field λ smooths local irregularities and stabilizes global behavior, while the obstruction constant Κ captures and bounds the cumulative effect of gaps and covariance. Together, these elements reduce Goldbach’s conjecture to a single remaining step, labeled uniform realization, which is the conversion of global dominance into pointwise existence. The final box indicates that once this step is established, Goldbach’s conjecture follows as a natural consequence of the framework.

Figure 11 illustrates the conceptual shift introduced by the Ω–λ–Κ framework in the study of Goldbach’s conjecture. The left panel summarizes the traditional view, in which Goldbach’s conjecture appears as an isolated problem, supported mainly by heuristics and extensive computation, with prime gaps and covariance regarded as potentially dangerous obstructions and Goldbach’s comet interpreted primarily as numerical evidence. The right panel presents the perspective developed in this review, where Goldbach’s conjecture is reframed as a problem of density dominance. In this new view, the conjecture admits a structural explanation, obstruction mechanisms are explicitly bounded, Goldbach’s comet is understood as an analytic invariant, and the entire problem is reduced to a single remaining technical step. The arrow between the panels emphasizes the transition from empirical uncertainty to conceptual clarity.

Figure 12 isolates, in a single statement, the only remaining step required to complete a proof of Goldbach’s conjecture within the Ω–λ–Κ framework. The figure formulates the

uniform realization principle, which asserts that once global prime density—measured through the density field λ—dominates all local obstructions bounded by the constant Κ, the existence of at least one Goldbach representation for every even integer E necessarily follows. This visualization makes explicit that no further structural or distributional hypotheses about primes are required. All complexity is reduced to formalizing this one implication, thereby clarifying both the power and the limitation of the framework developed in the review.

Appendix A. The Dominance Ratio Ω(E): Definition, Interpretation, and Examples

The dominance ratio Ω(E) was introduced to quantify the imbalance between global prime availability and local obstruction near a given even integer E. Its role is to make precise the intuition that prime density grows far more rapidly than any local irregularity capable of obstructing additive representations.

Ω(E) is defined as the ratio between the number of primes in the interval (E/2, E] and a representative local prime gap near E. The numerator captures the number of available candidates for Goldbach representations, while the denominator captures the size of the largest immediate obstruction arising from the discrete nature of the primes.

From the Prime Number Theorem, the number of primes in (E/2, E] grows on the order of E divided by the logarithm of E [Hadamard 1896; de la Vallée Poussin 1896]. In contrast, classical and modern results on prime gaps show that even the largest known gaps grow at most logarithmically with E [Cramér 1936; Granville 2007]. As a consequence, Ω(E) diverges as E increases.

This divergence is the analytic expression of the Tiger–Tortoise principle discussed in the main text: the “tiger” E and its associated density outrun the “tortoise” of local gaps. Ω(E) therefore measures not merely abundance but inevitability. Once Ω(E) is large, the possibility that local gaps alone could suppress all Goldbach representations becomes implausible.

Empirically, Ω(E) grows rapidly even for moderate values of E, consistent with computational observations of Goldbach’s comet [Oliveira e Silva et al. 2014]. This growth underpins the expanding brightness of the comet and explains why representation counts increase without bound.

Appendix B. The Density Field λ and Its Role in Additive Problems

The density field λ provides a smooth analytic description of prime distribution across scales. Near a large integer x, the density of primes is well approximated by the reciprocal of the logarithm of x, a fact established rigorously by the Prime Number Theorem [Hadamard 1896; de la Vallée Poussin 1896].

In additive problems, λ plays a dual role. First, it governs the expected number of representations by determining how often primes appear in relevant intervals. Second, it acts as a smoothing operator that suppresses the influence of local fluctuations when quantities are measured in density units.

When prime gaps are rescaled by λ, their effective size remains bounded. In contrast, λ-weighted prime counts grow without bound. This contrast explains why local irregularities become negligible in the presence of overwhelming density. In the context of Goldbach’s conjecture, λ accounts for the smooth envelope of Goldbach’s comet and aligns the present framework with the Hardy–Littlewood prediction [Hardy and Littlewood 1923; Vaughan 1997].

Importantly, λ does not assume randomness. It encodes average behavior derived from rigorous theorems and provides a natural bridge between discrete prime counts and continuous analytic approximations.

Appendix C. The Obstruction Constant Κ: Bounding Gaps and Covariance

The obstruction constant Κ was introduced to quantify the maximal impact that local irregularities can have on additive representations. These irregularities include prime gaps, arithmetic correlations, and covariance effects arising from congruence restrictions.

Κ is not intended to describe average behavior; rather, it bounds worst-case scenarios. Its finiteness reflects the fact that while primes exhibit structured correlations, these correlations are constrained and do not grow unchecked. Results such as the Bombieri–Vinogradov theorem demonstrate that primes are well distributed in arithmetic progressions on average, limiting the accumulation of covariance effects [Bombieri and Vinogradov 1965; Montgomery 1971].

Empirical data from Goldbach’s comet further support the bounded nature of Κ. While representation counts oscillate and exhibit banding, these fluctuations remain confined within predictable limits tied to arithmetic structure [Granville 2007; Oliveira e Silva et al. 2014].

Within the Ω–λ–Κ framework, Κ acts as a ceiling on obstruction. Even in the worst conceivable alignment of primes, obstruction cannot scale with E in a way that counteracts density.

Appendix D. Goldbach’s Comet as a Diagnostic Tool

Goldbach’s comet serves not only as empirical evidence for Goldbach’s conjecture but also as a diagnostic tool for analytic models. Its global shape tests predictions derived from prime density, while its internal structure reveals the influence of arithmetic constraints.

The agreement between the observed comet and the Hardy–Littlewood prediction confirms that density-driven models capture the leading behavior [Hardy and Littlewood 1923]. At the same time, deviations from smoothness provide insight into the nature and magnitude of covariance effects [Granville and Soundararajan 2007].

From the perspective of the Ω–λ–Κ framework, the comet visualizes scale separation. The widening tail reflects the divergence of Ω(E), the smooth envelope reflects λ, and the bounded texture reflects Κ. Any analytic model purporting to explain Goldbach’s conjecture must account for all three features simultaneously.

Appendix E. What Remains: The Uniform Realization Principle

The appendices above clarify why density dominance and bounded obstruction are sufficient to explain the existence and growth of Goldbach’s comet. What remains is a single technical step: the formulation and proof of a uniform realization principle.

Such a principle would assert that whenever λ-weighted density exceeds λ-weighted obstruction by a positive margin, at least one additive representation must exist. While this statement is supported by heuristic reasoning and numerical evidence, it has not yet been established in full generality.

The Ω–λ–Κ framework isolates this principle as the final obstacle. It shows that Goldbach’s conjecture is no longer blocked by unknown phenomena in prime distribution, but by the difficulty of converting average dominance into pointwise existence. Future progress in analytic number theory is likely to focus precisely on this conversion.

Conclusion: Goldbach’s Conjecture Revisited

Goldbach’s conjecture has long occupied a unique position in mathematics: elementary to state, overwhelmingly supported by computation, yet resistant to a complete analytic proof. The purpose of this review has not been to announce a final resolution, but to revisit the conjecture in light of modern analytic understanding and to clarify, as precisely as possible, why Goldbach’s conjecture must be true and where the remaining technical difficulty lies.

A central theme of this article has been the reinterpretation of Goldbach’s conjecture through the empirical phenomenon known as Goldbach’s comet. Far from being a numerical curiosity, the comet encapsulates the essential analytic structure of the problem. Its expanding envelope reflects the rapid growth of prime density, while its bounded oscillations reveal the limited influence of arithmetic irregularities. The persistence of this structure across vast computational ranges strongly suggests that no hidden obstruction mechanism exists.

To explain this phenomenon, we introduced a unified analytic framework based on three quantities: the dominance ratio Ω(E), the density field λ, and the obstruction constant Κ. Ω(E) quantifies the imbalance between the number of available primes and the size of local gaps, formalizing the principle that global prime density grows far faster than any local obstruction. The density field λ provides a smooth analytic measure of prime distribution, aligning empirical observations with classical results such as the Prime Number Theorem [Hadamard 1896; de la Vallée Poussin 1896] and the Hardy–Littlewood conjecture [Hardy and Littlewood 1923]. The obstruction constant Κ bounds the cumulative effect of gaps and covariance, reflecting deep results on the distribution of primes in arithmetic progressions and bounded gaps [Bombieri and Vinogradov 1965; Montgomery 1971; Maynard 2015].

Together, these quantities reveal a decisive scale separation: density dominates, obstruction is bounded, and covariance cannot accumulate. This insight reframes Goldbach’s conjecture as a problem of realization rather than existence. Density guarantees abundance; obstruction is too weak to suppress representations. What remains is the technical task of converting global dominance into a uniform existence statement for every even integer.