1. Introduction

Distributed applications deployed across multiple cloud providers and edge locations increasingly rely on replication of both data and access control policies to reduce latency and improve availability and resilience [

3,

6]. In such environments, consistency models are often weakened to eventual consistency, and access control policies (RBAC/ABAC, XACML) are replicated across multiple policy decision points (PDPs) and policy enforcement points (PEPs) spread over regions and administrative domains [

11,

13]. In the presence of asynchronous communication and potential network partitions, policy updates—additions of allowing and denying rules, delegation and revocation of privileges—can occur concurrently, leading to temporary divergence and conflicts.

Conflict-free replicated data types (CRDTs) provide a principled way to achieve Strong Eventual Consistency (SEC) without coordination by ensuring that replicas converge to a unique state when they have observed the same set of updates [

1,

5]. For sets of elements, several CRDT models have been proposed, including grow-only sets, two-phase sets (2P-Sets), observed-remove sets (OR-Sets), and variants with add-wins or remove-wins semantics [

3,

8]. However, specialising these models to replication of access control policies in security-critical Zero Trust environments [

14,

15] requires careful design of conflict resolution.

In the context of access control, an error in the direction of granting extra permissions is much more severe than a temporary error that denies legitimate access. Naïve schemes such as LWW or add-wins, when applied to policy identifiers under weak consistency, can lead to states where revoked policies remain effectively active because their last update or add operation dominates a concurrent revocation in the chosen conflict resolution semantics [

2,

10]. This is fundamentally at odds with the principles of Zero Trust and the requirements of security standards and regulations.

Goal. The goal of this paper is to define and formally justify a CRDT for access control policies, called Policy-CRDT, that:

provides Strong Eventual Consistency (SEC) for replicated policy sets;

enforces a safety monotonicity property: the presence of a revocation cannot reduce the effective strictness of the resulting policy set compared to any scenario without this revocation;

is compatible with existing ABAC/XACML policy languages and Zero Trust architectures in multi-cloud and microservice environments [

11,

13,

15].

Contributions. The main contributions of this paper are:

- N1

A formal definition of Policy-CRDT as a state-based CRDT (CvRDT) for sets of policy identifiers with remove-wins semantics, structured as a two-phase set (2P-Set).

- N2

A rigorous specification of the partial order on states, merge operation, and update operations

addPolicy/

removePolicy, satisfying the standard CRDT criteria and SEC conditions [

1,

5].

- N3

Proof that the merge operation is commutative, associative, idempotent and monotone, and that all local updates are monotone with respect to the state order, ensuring conflict-freedom.

- N4

A convergence theorem stating that Policy-CRDT satisfies Strong Eventual Consistency under eventual delivery.

- N5

A safety analysis of the remove-wins strategy: we prove that any policy for which at least one revocation occurs in the global history is inevitably deactivated on all replicas, and we compare this with LWW and add-wins using an analytic model of “dangerous” states (i.e., states with excessive permissions).

- N6

An architecture for deploying Policy-CRDT in a distributed PDP/PEP infrastructure aligned with Zero Trust and NIST SP 800-207/800-207A, including global and local control planes and integration with service mesh [

15].

- N7

An analytic evaluation of convergence latency and the probability of dangerous states based on classic results on randomized rumor spreading in fully connected networks [

16,

17], with plots and tables computed from explicit formulas, ensuring full reproducibility.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews CRDT fundamentals and related work on distributed access control and policy replication.

Section 3 introduces the formal model of access policies and Policy-CRDT.

Section 4 presents the convergence and SEC theorem and the safety analysis of remove-wins.

Section 5 describes a deployment architecture and pseudocode.

Section 6 provides the analytical evaluation.

Section 7 discusses limitations and future work.

Section 8 concludes.

2. Preliminaries and Related Work

2.1. CRDT Model and Strong Eventual Consistency

Conflict-free replicated data types (CRDTs) were introduced in [

1,

2] as data structures replicated at multiple nodes such that:

- (i)

each replica can be updated locally without coordination;

- (ii)

state merge resolves conflicts automatically;

- (iii)

replicas that have seen the same set of updates (possibly in different orders) converge to the same state.

For state-based CRDTs (also known as convergent replicated data types, CvRDTs) the state of each replica belongs to a join-semilattice

, where ⊔ is commutative, associative, idempotent and computes least upper bounds, and local updates are monotone with respect to ⊑ [

1,

3,

5]. Replicas periodically exchange states and merge them using

.

Definition 1

(Strong Eventual Consistency [

1,

5]).

A replicated object satisfies Strong Eventual Consistency (SEC) if:

-

(a)

Convergence: any two replicas that have observed the same set of updates (in possibly different orders) are in equivalent states.

-

(b)

Eventual delivery: every update is eventually delivered to all replicas (subject to the replication policy).

-

(c)

Termination: every local operation eventually completes.

It is shown in [

1,

5] that a state-based CRDT whose states form a join-semilattice, whose merge function is ⊔, and whose local updates are monotone satisfies SEC under eventual delivery.

2.2. Set CRDTs: G-Set, 2P-Set, OR-Set

The simplest CRDT for sets is the grow-only set (G-Set), which allows only add operations; its state is a set

S and merge is set union

[

3,

7]. To support removals, the two-phase set (2P-Set) represents the state as a pair of sets

, where

A contains elements that have been added and

R contains elements that have been removed (tombstones). Membership is defined as

[

7]. The 2P-Set exhibits remove-wins semantics: in the presence of concurrent add and remove of the same element, the element eventually becomes absent; however, once removed, an element cannot be re-added with the same identity.

More sophisticated structures, such as observed-remove sets (OR-Sets) and their optimizations [

8], use unique tags for each insertion, allowing elements to be logically re-added while tracking causal relationships, at the cost of more complex metadata.

2.3. Distributed Access Control And Policy Replication

Attribute-Based Access Control (ABAC) [

11,

12] defines attributes of subjects, objects, actions and context as primary building blocks of policies, without fixing specific combining algorithms. XACML 3.0 [

13] provides an XML-based policy language and a reference architecture with PDPs and PEPs, together with combining algorithms such as

deny-overrides,

permit-overrides and others. However, these combining algorithms are defined for flat sets of policies and do not address weakly consistent replication across multiple regions.

The problem of maintaining replicated authorizations and policies has been studied both in the context of distributed databases [

9] and weakly consistent data stores. Samarati et al. [

9] analyse replicated authorizations with optimistic replication and highlight difficulties with revocations. Wobber et al. [

10] propose policy-based access control for weakly consistent replication, where policies are treated as data that co-travels with collection contents, and show that careless handling of revocations can lead to persistent divergence.

Zero Trust Architecture (ZTA) [

14] and its cloud-native extension [

15] emphasise continuous verification, least privilege and uniform policy enforcement across locations. In these architectures, a global control plane provides high-level policies, while local enforcement is performed by PEPs (often implemented as service-mesh sidecars) and PDPs within each cluster. A key challenge is to replicate policies in a way that prevents privilege escalation in the presence of concurrent updates and network partitions.

In this work, we specialise the 2P-Set remove-wins semantics to the domain of access control policies and show how to obtain a Policy-CRDT that provides strong guarantees on revocations and convergence.

3. Formal Model of Policy-CRDT

3.1. Access Policy Model

Let

Q be the set of access requests. Each

is described by attributes of the subject, object, action and context, in the spirit of ABAC [

11,

12]. Let

be the set of effects.

Definition 2

(Access policy).

An access policy is a triple

where is a globally unique policy identifier, is a predicate describing applicability of the policy to a request, and is the effect of the policy.

Let

be the set of all possible policies, and let

be the set of identifiers, with

. We assume that any modification to the content of a policy uses a new identifier, which matches common practice in industrial PDPs and supports auditability [

10].

3.2. Replica State and Partial Order

Let R be a finite set of replicas, each storing the replicated state of active policy identifiers. At the CRDT level, we only track identifiers; the full policy bodies are stored in a separate repository indexed by identifiers.

Definition 3

(Policy-CRDT state).

The state of a replica is a pair

where is the set of policy identifiers that have ever been added, and is the set of identifiers that have been revoked (tombstones).

The set of

active policies at state

S is

Definition 4

(Partial order on states).

On the set of states we define a partial order by

Intuitively, a larger state contains more information about additions and revocations.

Definition 5

(Merge operation).

The merge of two states and is

Lemma 1.

The structure is a join-semilattice: ⊔ is commutative, associative and idempotent, and is the least upper bound of and with respect to ⊑.

Proof. Commutativity and associativity follow from the corresponding properties of set union: , , and similarly for . Idempotence holds since , .

Let with and . Then and , hence ; likewise . Thus . On the other hand, and by construction, so is a least upper bound. □

3.3. Operations and Remove-Wins Semantics

Definition 6

(Policy-CRDT operations). For a replica with local state we define:

addPolicy for :

merge for a remote state :

Proposition 1

(Monotonicity of local updates). For any state S and operation we have .

Proof.

addPolicy adds i to A and leaves T unchanged, so and . removePolicy adds i to T and leaves A unchanged, so , . □

Definition 7

(Remove-wins semantics).

Let be the set of alladdPolicy andremovePolicy operations in the global history. In the limit state after all updates have been delivered, the remove-wins semantics for identifier i is:

In particular, if contains at least oneremovePolicy, then .

This is exactly the semantics of a 2P-Set [

3,

7] and is well suited to access control, where revocation is expected to dominate any prior additions with the same identifier.

4. Convergence and Strong Eventual Consistency

Lemma 2.

The merge operation is commutative, associative and idempotent. Repeated merge with a finite family of states is invariant under permutation of their order.

Proof. Direct consequence of commutativity, associativity and idempotence of ⊔ proven above. Any finite expression depends only on the multiset , not on the order or multiplicity. □

Theorem 1

(SEC for Policy-CRDT). Assume that each replica of Policy-CRDT periodically sends its state to other replicas and that all messages are eventually delivered (no infinite losses). Then for any two replicas and any time t after which no new updates occur, there exists such that . In other words, Policy-CRDT satisfies Strong Eventual Consistency.

Proof. The proof follows the standard argument for state-based CRDTs [

1,

5]. Let

U be the set of all local updates (add/remove), and let

be the subset delivered to replica

r. Starting from an initial state

, each update

u is a monotone function

, and the state of replica

r can be written as

By eventual delivery there exists a time

such that for all replicas

we have

for

. Then

because ⊔ is commutative, associative and idempotent and the set of functions

is the same in both expressions. This implies convergence and thus SEC. □

Corollary 1

(Convergence of active policy sets).

Under the assumptions of Theorem 1, there exists such that for all ,

4.1. Safety of Remove-Wins for Access Control

Consider a fixed policy identifier with for the corresponding policy. Let be the limit state of replica r.

Proposition 2

(Anti-escalation of privileges). If there exists at least oneremovePolicy in the global history, then in the limit state we have for all replicas .

Proof. By SEC all replicas converge to the same state . Each removePolicy adds i to some local tombstone set; after convergence, . Active policies are , hence and thus not active on any replica. □

In contrast, in an LWW register or an add-wins set, the final state for

i depends on the resolution of concurrent add/remove operations and on clock values used to break ties. Under realistic assumptions about clock skew and message reordering, revocations may fail to dominate additions, leading to states where a revoked policy remains active [

2,

10].

Thus, remove-wins provides a semantically conservative interpretation consistent with Zero Trust: uncertainty is resolved in favour of stricter access control (disabling potentially outdated policies) rather than silently granting permissions.

5. Architecture and Implementation

5.1. Zero Trust Deployment Architecture

Following NIST SP 800-207 and SP 800-207A [

14,

15], we consider an architecture with:

a global control plane defining a unified set of access control policies and executing addPolicy/ removePolicy operations;

per-cluster PDPs and PEPs (e.g., in each cloud region, data center or edge site), integrated with a service mesh (such as Istio), where sidecar proxies serve as PEPs;

a Policy-CRDT replica in each cluster, synchronised with others via state-based replication (gossip or periodic push/pull).

The global control plane publishes policy updates, which are applied to the local Policy-CRDT state and then propagated across replicas using merge messages. PEPs making run-time decisions consult the local set of active policy identifiers

and evaluate only those policies (retrieved from a policy repository) using standard ABAC/XACML combining algorithms [

11,

13].

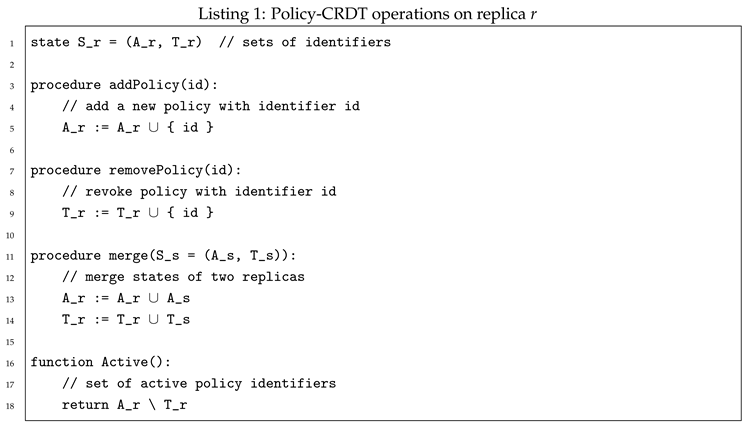

5.2. Pseudocode

We give pseudocode for Policy-CRDT operations on replica r.

The cost of

addPolicy and

removePolicy is

on average when sets are implemented as hash tables. The cost of

merge is

; known optimisations for state-based CRDTs (delta-CRDTs, digest-driven synchronisation) can reduce network overhead and merge costs [

3].

5.3. Integration with PDP/PEP

Integration with ABAC/XACML-based PDPs and PEPs can be realised as follows:

policy bodies (XACML rules, ABAC expressions) are stored in a durable repository keyed by identifiers ;

Policy-CRDT manages only the set of active identifiers ;

for each request

q, the PDP fetches all policies whose identifiers are in

, evaluates them and combines their effects using standard combining algorithms (e.g., deny-overrides) [

11,

13].

Policy-CRDT is thus responsible for convergent control over which policy versions are considered active; the logic of policy evaluation and combination remains unchanged.

6. Analytical Evaluation

In this section we provide a reproducible analytical evaluation of Policy-CRDT in comparison with LWW and add-wins strategies. All numerical values are derived from explicit formulas;

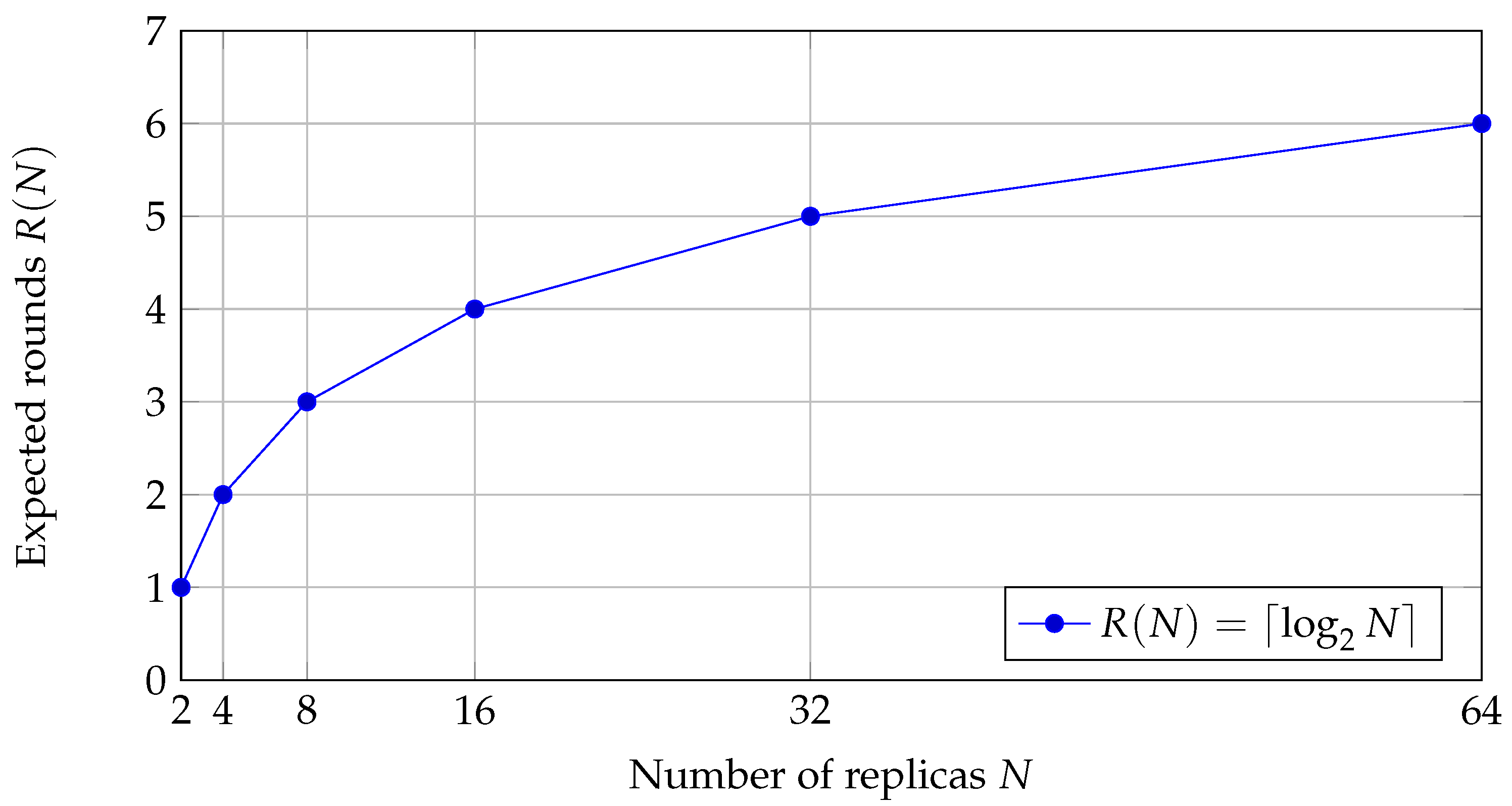

6.1. Convergence Latency Under Gossip Replication

Consider

N replicas in a fully connected network. Suppose that CRDT states are disseminated using a randomized gossip protocol (push or push-pull), as analysed in [

16,

17]. These works show that the expected number of rounds until all nodes are informed is

.

As a simple approximation we take

as a proxy for the expected number of communication rounds until convergence, assuming no new updates are introduced. The actual wall-clock time is proportional to

with a factor determined by average network latency.

Figure 1 shows

for

.

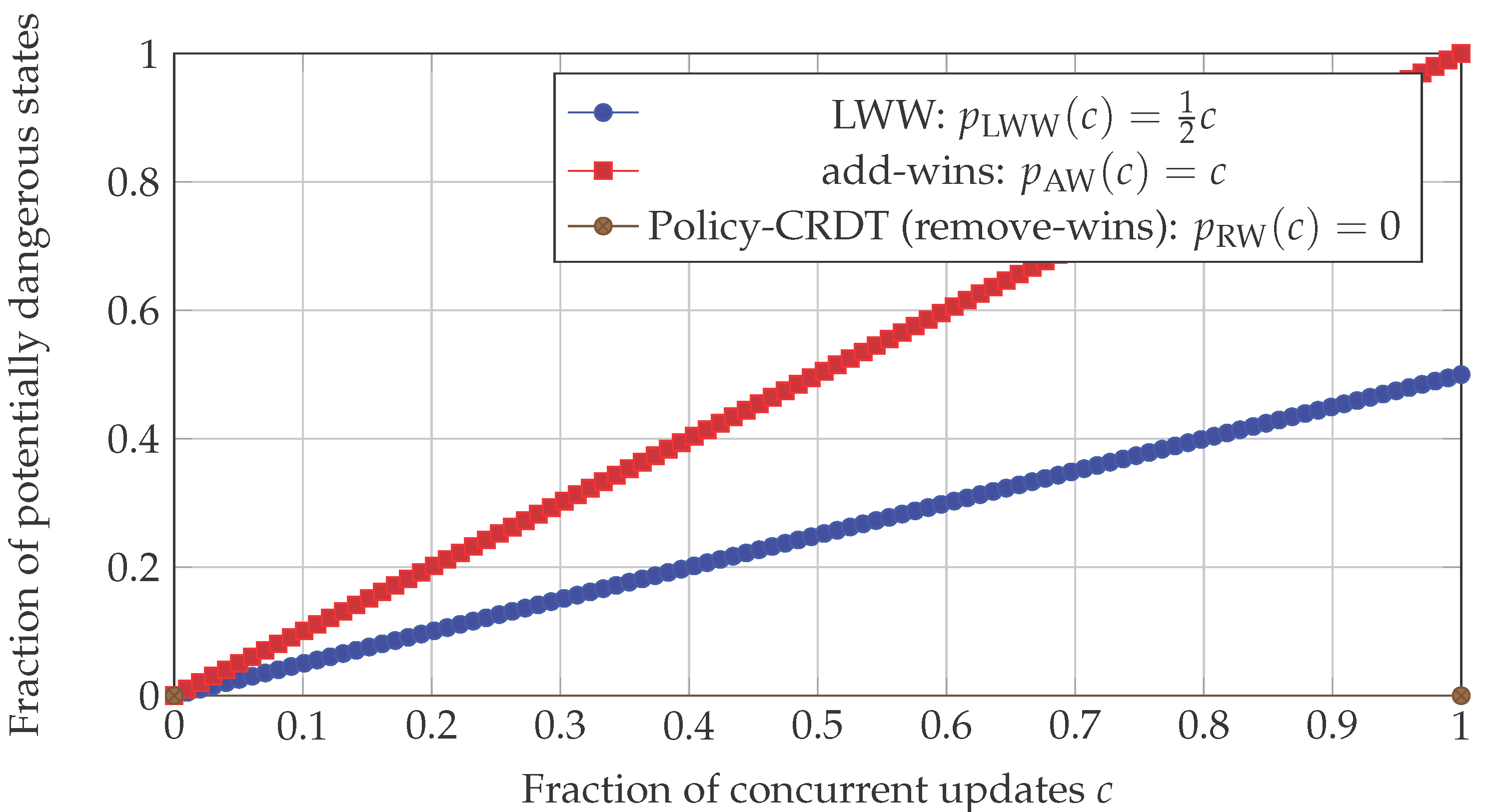

6.2. Model Of Conflicts And Dangerous States

We now consider an abstract probabilistic model of concurrency for a single policy identifier :

among all updates affecting i, a fraction participates in concurrent add/remove conflicts;

for each such conflict, we are interested in whether the final state of i is dangerous, i.e., whether the policy remains active even though at least one revocation attempt occurred.

For simplicity we assume:

in an LWW scheme, add and remove are equally likely to “win” in a conflict (e.g., due to randomised tie-breakers), so each conflicting pair yields a dangerous outcome with probability ;

in an add-wins set, any conflict leads to the policy being active, so each conflict is dangerous;

in Policy-CRDT (remove-wins), any conflict eventually yields the policy inactive, so conflicts are never dangerous.

Let

,

and

be the expected fractions of dangerous states for a fixed

c. With the assumptions above we obtain

Figure 2 plots these functions.

6.3. Tabular Results

Combining the expressions for and , , , we can build a table for several representative values of N and c.

All values in

Table 1 follow directly from the formulas above, so the results are fully reproducible.

7. Discussion and Limitations

7.1. Practical Benefits of Policy-CRDT

The analytical comparison indicates that Policy-CRDT with remove-wins semantics eliminates an entire class of dangerous states related to conflicting additions and revocations of policies:

for any non-zero concurrency level , LWW and add-wins admit a non-zero fraction of dangerous states proportional to c;

Policy-CRDT guarantees zero dangerous states in this model, because any revocation eventually suppresses the policy globally.

In a Zero Trust setting, where decisions are continuously enforced and do not rely on network locality for trust [

14,

15], this represents a meaningful safety improvement: in the presence of network delays or partitions the worst-case effect of using Policy-CRDT is temporary over-denial of some legitimate operations, whereas LWW/add-wins can silently permit operations that should be prohibited according to revocations.

7.2. Overheads And Tombstone Growth

A classical drawback of 2P-Set-based CRDTs, and thus of Policy-CRDT, lies in the unbounded growth of the tombstone set T: identifiers added to T are never removed, which can cause memory and bandwidth overhead. Possible mitigation strategies include:

use of large random identifiers with negligible collision probability, enabling occasional “re-keying” or truncation of identifier spaces with carefully designed safety guarantees;

periodic compaction of states using safe garbage-collection procedures based on globally agreed cut-offs (e.g., via durable logs or consensus) or on more advanced CRDT designs [

3,

8];

partitioning of policies into domains and replication of separate CRDT instances per domain to bound state sizes.

Designing such mechanisms while preserving the security guarantees is non-trivial and is left for future work.

7.3. Policy Strictness and Lack of Some Invariants

Remove-wins semantics can lead to overly strict policies in scenarios where temporary revocations are quickly followed by re-authorisation intent. Under Policy-CRDT, a re-authorisation must use a new policy identifier, which is good for audit history but can complicate lifecycle management.

Moreover, while Policy-CRDT provides SEC for the set of active policies, it does not automatically enforce higher-level global invariants that depend on combinations of policies (e.g., caps on the total number of delegated privileges) [

3,

5]. Enforcing such invariants generally requires additional coordination or specialised coordination-free designs.

7.4. Future Work

Promising directions for future research include:

integration of Policy-CRDT with cryptographic enforcement mechanisms (e.g., CP-ABE or HABE), where keys and ciphertext policies are derived from replicated policy identifiers;

extension of the model to temporal policies with time-bounded access and deadlines, which require consistent interpretation of time under weak consistency;

formal specification and machine-checked verification of Policy-CRDT using existing frameworks for CRDT verification [

18].

8. Conclusions

This paper presented a formal algebraic approach to replication of access control policies in asynchronous multi-cloud and edge environments based on a conflict-free replicated data type called Policy-CRDT with remove-wins semantics. The state of Policy-CRDT is defined as a 2P-Set over policy identifiers, forming a join-semilattice; local updates are monotone and the merge function computes least upper bounds, ensuring Strong Eventual Consistency under eventual delivery.

We proved that the remove-wins strategy enforces an anti-escalation property: any policy for which at least one revocation occurs is eventually inactive on all replicas. A simple analytical model shows that, unlike LWW and add-wins strategies, Policy-CRDT eliminates a family of dangerous states with excessive permissions for any level of concurrency in updates.

We described a deployment architecture integrating Policy-CRDT into a Zero Trust PDP/PEP infrastructure and provided a reproducible analytical evaluation of convergence latency and safety characteristics. Policy-CRDT thus offers a formally justified and practically relevant mechanism for convergent access control in asynchronous distributed systems and paves the way for systematic use of CRDT techniques in cybersecurity.

References

- M. Shapiro, N. Preguiça, C. Baquero, and M. Zawirski, “Conflict-free replicated data types,” in Stabilization, Safety, and Security of Distributed Systems (SSS 2011), LNCS, vol. 6976, Springer, 2011, pp. 386–400. [CrossRef]

- M. Shapiro, N. Preguiça, C. Baquero, and M. Zawirski, “A comprehensive study of convergent and commutative replicated data types,” INRIA Research Report RR-7506, 2011.

- N. Preguiça, “Conflict-free replicated data types: An overview,” arXiv:1806.10254, 2018.

- N. Preguiça, C. Baquero, and M. Shapiro, “Conflict-free replicated data types (CRDTs),” in Encyclopedia of Big Data Technologies, Springer, 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Burckhardt, “Principles of eventual consistency,” Foundations and Trends in Programming Languages, vol. 1, nos. 1–2, pp. 1–150, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Y. Saito and M. Shapiro, “Optimistic replication,” ACM Computing Surveys, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 42–81, 2005. [CrossRef]

- “Conflict-free replicated data type,” Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia, accessed 5 December 2025. URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conflict-free_replicated_data_type.

- A. Bieniusa, M. Zawirski, N. Preguiça, M. Shapiro, C. Baquero, V. Balegas, and S. Duarte, “An optimized conflict-free replicated set,” arXiv:1210.3368, 2012.

- P. Samarati, P. Ammann, and S. Jajodia, “Maintaining replicated authorizations in distributed database systems,” Data & Knowledge Engineering, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 55–84, 1996. [CrossRef]

- T. Wobber, D. Terry, and T. Rodeheffer, “Policy-based access control for weakly consistent replication,” in Proceedings of the 5th European Conference on Computer Systems (EuroSys 2010), ACM, 2010, pp. 293–306. [CrossRef]

- V. C. Hu, D. Ferraiolo, R. Kuhn, A. Schnitzer, K. Sandlin, R. Miller, and K. Scarfone, Guide to Attribute Based Access Control (ABAC) Definition and Considerations, NIST Special Publication 800-162, 2014. [CrossRef]

- V. C. Hu, D. Ferraiolo, and R. Kuhn, “Attribute-based access control,” IEEE Computer, vol. 48, no. 2, pp. 85–88, 2015. [CrossRef]

- OASIS, eXtensible Access Control Markup Language (XACML) Version 3.0, OASIS Standard, Jan. 2013. URL: https://docs.oasis-open.org/xacml/3.0/xacml-3.0-core-spec-os-en.html.

- S. Rose, O. Borchert, S. Mitchell, and S. Connelly, Zero Trust Architecture, NIST Special Publication 800-207, 2020. doi: 10.6028/NIST.SP.800-207. [CrossRef]

- R. Chandramouli and Z. Butcher, A Zero Trust Architecture Model for Access Control in Cloud-Native Applications in Multi-Location Environments, NIST Special Publication 800-207A, 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. M. Karp, C. Schindelhauer, S. Shenker, and B. Vöcking, “Randomized rumor spreading,” in Proceedings of the 41st Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science (FOCS 2000), IEEE, 2000, pp. 565–574. [CrossRef]

- B. Doerr and A. Kostrygin, “Randomized rumor spreading revisited,” in 44th International Colloquium on Automata, Languages, and Programming (ICALP 2017), LIPIcs, vol. 80, 2017, pp. 138:1–138:14. [CrossRef]

- P. Zeller, A. Bieniusa, and P. Thiemann, “Formal specification and verification of CRDTs,” in Correct System Design, LNCS, vol. 9360, Springer, 2015, pp. 33–54. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).