1. Introduction

Cancer is a major global health challenge, being the second leading cause of death worldwide. In 2018, it was responsible for nearly 9.6 million deaths and about 18.1 million new cases.[

1] According to the 2025 report, cancer causes about 2.04 million new cases and 618 000 deaths each year in the United States, reflecting a rise among younger adults and women.[

2] Neuroblastoma, the most common extracranial solid tumor in children, is ranking as the third most prevalent pediatric cancer – approximately 15% of childhood cancer deaths.[

3] This underscores its significant impact on healthcare. The tumor develops in immature nerve cells – neuroblasts – during child development.[

4] The disease is linked to changes that cause oncogene overexpression (MYCN, NTRK2, COL1A2, COL6A3, COL12A1, LAMA3, CLDN11, DOCK7 and DDX1), [

5] and inactivation of tumor suppressors (CASZ1, GRHL1, CHL1, NF1, KIF1Bβ, CAMTA1, MOXD1, and TP53). Gene expression changes involve MYCN, ALK, PHOX2B, PTPRD, CASP8, RASSF1A, HATs, EZH2.[

6] MYCN amplification occurs in 20–25% of cases and signals aggressive disease. [

7] N-MYC, one of three MYC subtypes proteins (C-MYC, L-MYC, N-MYC), encodes a transcription factor[

8] that regulates cell cycle, growth, apoptosis, DNA repair, metabolism, and immune response.[

9] The protein modulates neuroblastoma proliferation and accumulates due to interaction with Aurora-A kinase, preventing metabolic degradation via an inhibitor-sensitive N-MYC/Aurora-A complex.[

10] The stability of MYC protein is controlled by phosphorylation at the conserved MBI sequence, which directs proteolysis and ubiquitination.[

11] Dephosphorylation of N-MYC at Ser62 by protein phosphatase 2A allows the SCF-FbxW7 E3 ubiquitin ligase to add a K48-linked ubiquitin chain.[

12] Aurora-A kinase blocks this process in neuroblastoma, leading to MYCN accumulation.

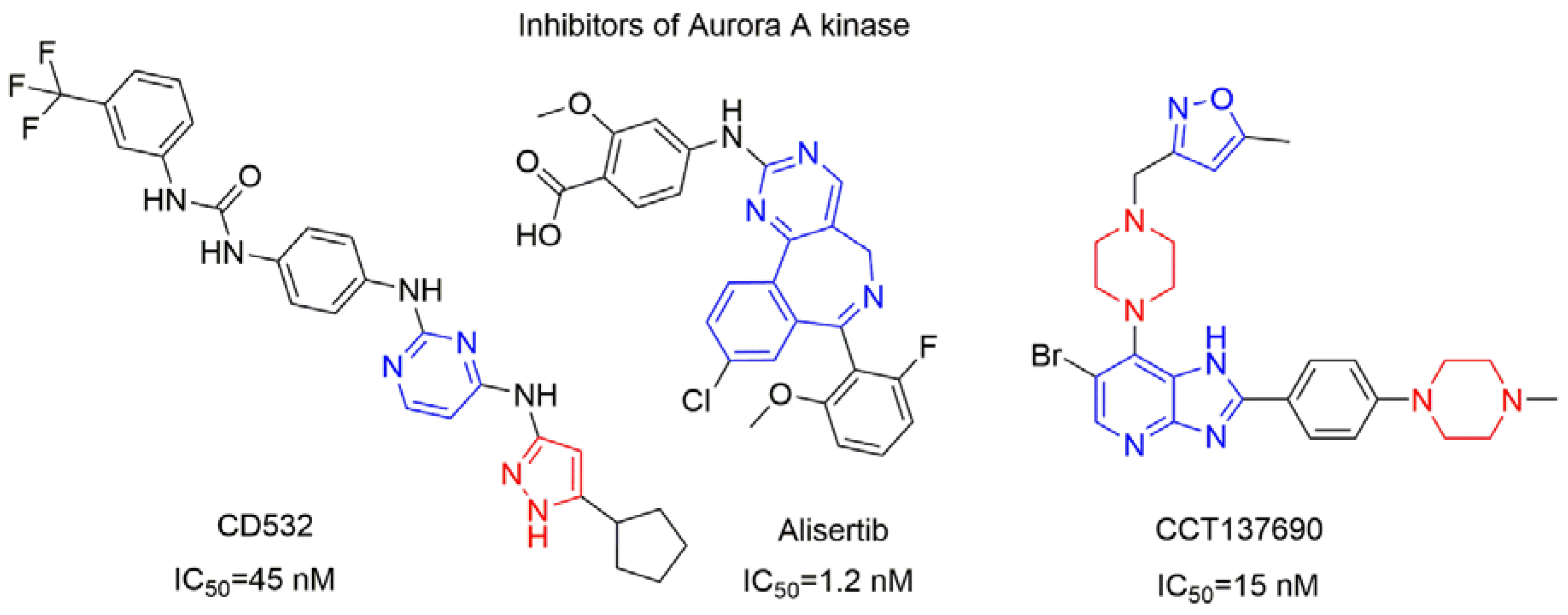

Aurora-A 532. (IC

50 = 45 nM), see

Figure 1 left, that both inhibits kinase activity and promotes MYCN degradation.[

13] Alisertib (MLN 8237), see

Figure 1 center, is an ATP-competitive Aurora-A kinase inhibitor (IC

50 = 1.2 nM) that inhibits the kinase, disrupts the cell cycle, induces apoptosis, and suppresses MYCN expression.[

14] CCT137690, see

Figure 1 right, is an isoxazole-containing compound that inhibits Aurora-A (IC

50 = 15 nM), Aurora-B (IC

50 = 25 nM), and Aurora-C (IC

50 = 19 nM), stopping tumor growth in MYCN-overexpressing neuroblastoma models. The high activity of CCT137690 suggests that 1,3-oxazole analogues might act as the kinase inhibitors.

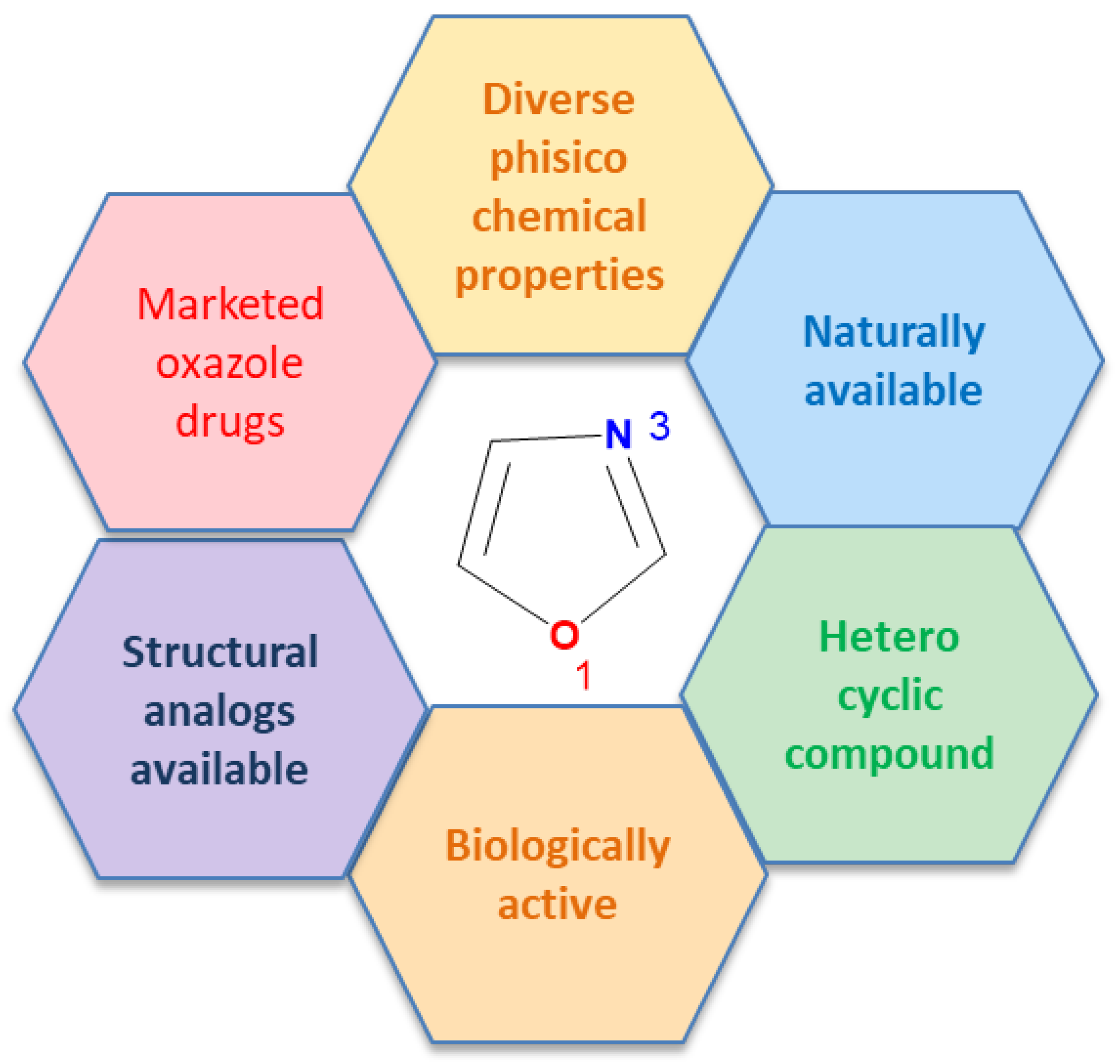

The oxazoles have been part of organic chemistry since 1917 and became more prominent after discovery of penicillin antibiotics, see

Figure 2. Structurally, oxazoles are planar, sp2-hybridized five-membered rings with oxygen at position 1 and nitrogen at position 3, separated by carbon, see

Figure 2 center. Their structure is isomeric to furan and pyridine. The electronic properties of oxazoles affect their reactivity, including participation in electrophilic and Diels-Alder reactions. Compared to pyridine, oxazoles are less resistant to oxidation, but more stable in acid and at elevated temperatures. [

15] These features support their use in organic synthesis and drug development. [

16] Oxazoles serve as building blocks in drug development because the presence of oxygen and nitrogen enables interactions with various enzymes and receptors.[

16] Their five-membered aromatic structure allows for substitutions at C-2, C-4, and C-5, which can be used to tune electronic, steric, and lipophilic properties. Oxazoles function as bioisosteres for amide or peptide bonds, enabling hydrogen bonding and molecular recognition. Their rigid, planar structure contributes to binding affinity and selectivity.

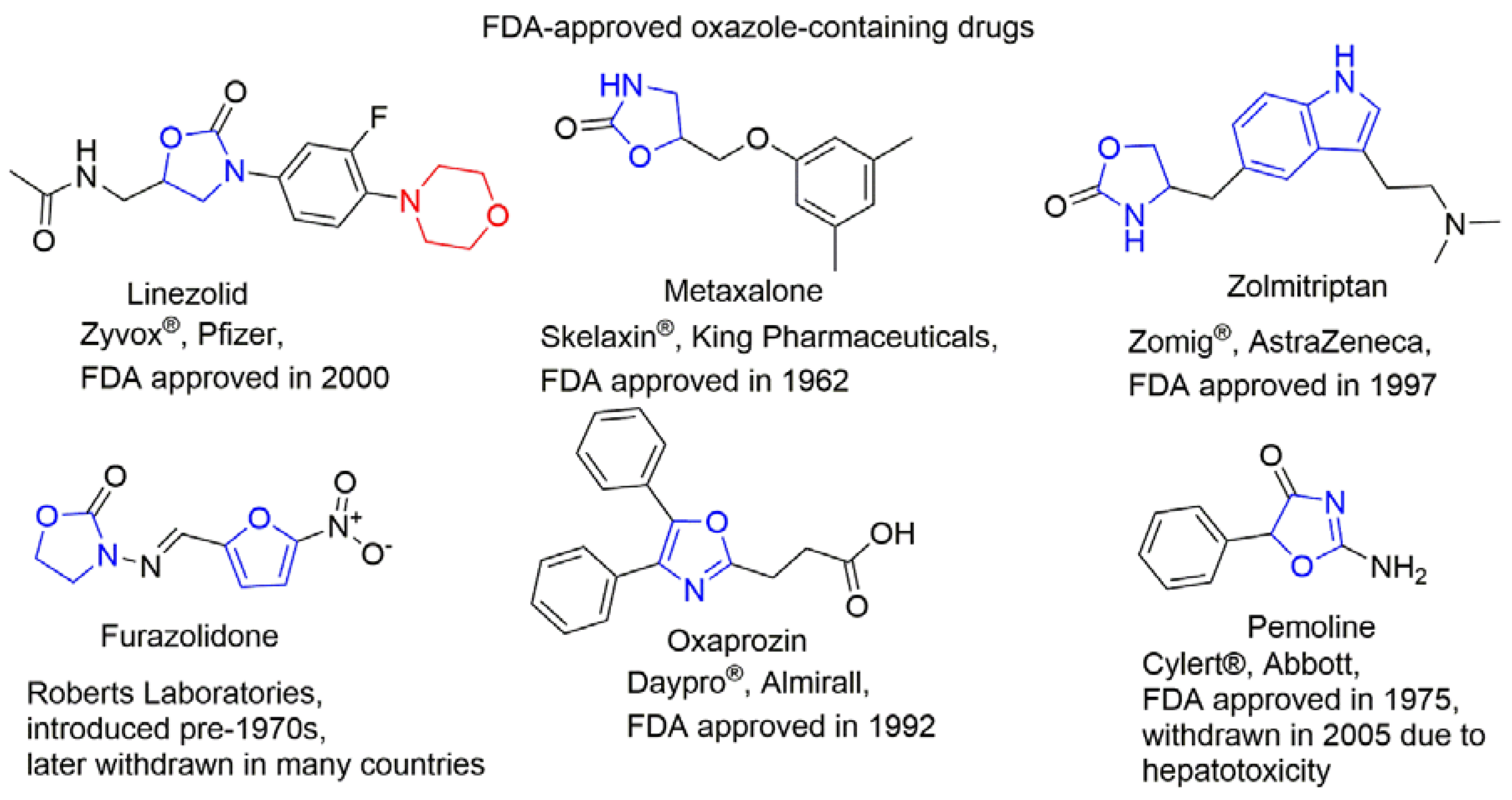

1,3-Oxazoles inhibit enzymes, block receptor activity, or interfere with microbial biosynthesis, supporting use as anticancer, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, and antibacterial agents, see

Figure 3.[

17] Oxazole-containing drugs show anticancer activity against multiple cancer types. Tivozanib, for example, binds the ATP-binding site and regulatory domain of VEGFR2, blocking autophosphorylation and signal transduction.[

18] Also, the sulfonyl and cyano groups

18, and the piperazine moiety are present in various clinically used anticancer drugs: Prexasertib (Chk1 and Chk2 inhibitor),

19 Olaparib (PARP inhibitor),[

19] Palbociclib (selective inhibitor of the cyclin-dependent kinases CDK4 and CDK6),[

20] and Navitoclax (Bcl-2 inhibitor)[

21] are examples.

Oxazole-based drugs were not used for neuroblastoma treatment,[

22] but their properties justify further investigation. In this study, oxazole–piperazine–sulfonyl hybrids were synthesized and tested for anticancer activity on HeLa, HepG2, Huh7, MDA-MB-231, MCF7, M21, Kelly, and SH-SY5Y cell lines. The molecular mechanisms of action and ADME properties of the most active compounds (

7a,

7b,

8aa) were also investigated.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Chemicals Materials and Methods

All chemicals were used without further purification in the synthetic procedures, including doxorubicin hydrochloride (batch WRS DR 02, was provided by Gemini PharmChem Mannheim GmbH/ Synbias Pharma AG), commercially available reagents (Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany), reagent-grade solvents (Lach-Ner, Neratovice, Czech Republic), and deutero solvents (Eurisotop, Saint-Aubin, France). The reaction progress was monitored using thin-layer chromatography (TLC) on silica gel 60 F254 plates (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). Melting points (M.p.) were determined in open capillary tubes using a Stuart SMP40 apparatus with a 2 °C/min ramp, and values are reported in °C. NMR spectra (1H and 13C) and 2D HSQC plots were recorded on a Bruker Avance III 400 MHz spectrometer in DMSO-d6, with residual SO(CD3)(CD2H) (δH = 2.50 ppm) or SO(CD3)2 (δC = 39.52 ppm) as the internal standard. HPLS analysis was conducted on an Agilent 6540 UHD Accurate-Mass Q-TOF LC/MS G6540A Mass Spectrometer. Elemental analysis (CHNS) was performed using a Vario Micro Cube device. Column chromatography was performed using Macherey-Nagel Silica 60, 0.04-0.063 mm silica gel. FT-IR spectra were recorded on a Shimadzu IRTracer-100 spectrometer (Kyoto, Japan) using KBr pellets (1% w/w), with a resolution of 2 cm−1 and detection at 254 nm. The spectral data of all compounds are presented in the Supplementary Information.

2.2. Biology. In vitro Anticancer Studies.

Cell cultures. To evaluate the cytotoxicity and anticancer potential of the synthesized oxazole derivatives, a panel of human cancer cell lines—including HeLa (cervical carcinoma), HepG2 and Huh7 (hepatocellular carcinoma), MDA-MB-231 and MCF7 (breast adenocarcinoma), M21 (melanoma), and Kelly and SHSY5Y (neuroblastoma) – was employed. These cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. Additionally, human embryonic kidney cells HEK293 cells were used as a non-cancerous control to assess selectivity toward malignant cells. Cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% bovine calf serum and 5% penicillin/streptomycin, and maintained under standard conditions (37 °C, 5% CO2). Treatments were applied 24 hours after seeding, followed by a 48-hour incubation with either vehicle or compound-containing medium. Cell viability was assessed using the WST-1 assay, which quantifies mitochondrial activity through tetrazolium salt reduction by measuring IC50, or the half maximal inhibitory concentration in this test against neuroblastoma cancer cell, we studied drug activity and possible cellular pathways of action. Additionally, to learn relative efficacy and SI of the hit compounds (7a; 7b and 8aa), as indicated by IC50, doxorubicin was used in identical experiments, especially in targeting specific tumor types. The cells were propagated in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Gibco), supplemented with 10% bovine calf serum (Gibco) and 5% penicillin/streptomycin. All cell lines were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 and 95% air atmosphere.

Cell treatment procedures. The cells were plated at a density of 2.5 × 105 cells/well (The Countess Automated Cell Counter, Invitrogen) in 96-well plates and incubated overnight. After 24 hours of incubation, 100 µL of either fresh media or fresh media containing diluted agents was added into each well and incubated for a further 48 hours. The experiments with addition of MeOH were used as solvent control.

Cell viability measured by WST-1. The effects of agents on the viability of cells were determined using the cell viability assay WST-1 (Roche). WST-1 allows colorimetric measurement of cell viability due to reduction of tetrazolium salts to water-soluble formazan by viable cells. The amount of formed formazan dye correlates with the number of viable cells. The measurements were completed 48 hours after the cell treatments. The experiments, with an addition of 5 µL of MeOH, were used as a solvent control. Five microliters per well of the WST-1 reagent was added to 100 µL of the cell culture medium, incubated at 37 °C for 2 hours, after which the absorbance was measured at 450 nm by using a TECAN GENios Pro Microplate Reader. WST-1 reduction correlates with the number of metabolically active, viable cells, thus providing a quantitative readout of cytotoxicity.

2.3. Molecular Modeling

Molecular docking was performed using AutoDock Vina v1.2.5 program.24 The X-ray crystal structures of target proteins complexed with inhibitors were obtained from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB). Prior to docking, protein structures were prepared using AutoDockTools (ADT) v.4.2 software,25 which provides a graphical user interface for model setup. Polar hydrogen atoms were added, all atoms were renumbered, and Gasteiger partial charges were assigned using ADT. The prepared protein structures were then saved in PDBQT format for use in docking simulations. The 2D and 3D structures of the ligands 7a, 7b, and 8aa were generated and refined through pre-optimization using the ChemAxon MarvinSketch v.23.11.0 software.26 The ligand structure optimization and its energy were minimized by the Avogadro v.1.2.0 program.27 This procedure was performed using the Auto Optimize tool, which employed molecular mechanics calculations to refine the molecular geometry by minimizing the potential energy. We used the force field with MMFF94s, the “steepest descent” algorithm, and the default setting for “Steps per Update” of 4. Next, the three-dimensional structures of the ligands were prepared for docking studies using the AutoDockTools program and saved in PDBQT format for subsequent molecular docking. Docking studies were performed using AutoDock Vina with a grid spacing of 0.375 Å and a grid map ranging from 30 × 30 × 30 Å to 40 × 40 × 40 Å. The docking centers were the geometric centers of the co-crystallized ligands. Under these conditions, the optimized protein and ligand structures served as inputs for docking simulations targeting the defined active site. The AutoDock Vina scoring function was employed to evaluate and rank the docking poses based on their predicted binding affinities. The docking output files were rendered and examined for key interactions between the ligands and the amino acid residues constituting the active sites using BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer 2019.28 To ensure the reliability of the docking results, five to six independent runs were performed, yielding up to nine distinct docking poses. Pose selection was based primarily on the AutoDock Vina-predicted binding affinities (kcal/mol) and RMSD values. Additionally, the presence and geometry of potential hydrogen bonds and electrostatic interactions were considered.

2.4. ADMET Evaluation

The online tool, ADMETlab 3.0 web server,[

23] was used to calculate the ADMET properties of compounds

7a, 7b, and

8aa in comparison to Doxorubicin.[

24] ADMETlab 3.0 tool includes a multi-task DMPNN (directed message passing neural network) architecture based on molecular descriptors. This approach ensures high-speed calculation and performance for each endpoint, along with an elevated level of accuracy and robustness. Additionally, the pkCSM web server was used to predict some ADMET properties.[

25]

2.5. Biodegradability Study.

Biodegradability of the selected oxazoles

7a,

7b, and

8aa was determined using modified aerobic biodegradation test OECD 301D[

26] known as Closed Bottle Test (CBT),[

27] usually implied as an initial screening test for organic compounds.[

28]

CBT setup with modifications where biological oxygen consumption is measured with an optode oxygen sensor system using PTFE-lined PSt3 oxygen sensor spots (Fibox 3 PreSens, Regensburg, Germany), allows measuring BOD without dispensing it from the stock solution each time.

Each CBT run consisted of four different series, each done in duplicates. First was „reference series „in which readily biodegradable sodium acetate in a known concentration (6.41 mg/L) was added to a flask of mineral medium inoculated with effluent from a wastewater treatment plant. As sodium acetate is rapidly biodegradable it acted as a reference and control for monitoring activity of microbes in the inoculum.[

29] In the test series a studied compound as a sole source of carbon was added to the inoculated mineral medium. The test compound was added in a concentration corresponding to theoretical oxygen demand (ThOD) of approximately 5 mg/L. The details of the calculated ThOD and the amount of test substance used to measure biodegradability in the CBT are listed in

Table S1.

Effluent from wastewater treatment plant was collected at municipal wastewater treatment plant in Tallinn, Estonia (Paljassaare wastewater treatment plant, 59°27′55.5”N 24°42′08.8”E). Results from each run were accepted if the following criteria were met: (i) the difference of extremes of replicate values at the plateau is less than 20%, (ii) oxygen concentration in test series bottles must not fall below 0.5 mg/L at any time, (iii) sodium acetate in reference series must be degraded ≥ 60% by day 14. Blank bottle oxygen consumption was also monitored to avoid the possibility of the system turning from aerobic to anaerobic.

3. Result and Discussion

3.1. Chemistry

Previously, we synthesized and studied sulfonyl derivatives of oxazole, which demonstrated significant antitumor activity. In our study several 5-arylsulfonyl-1,3-oxazole-4-carbonitriles show high activity on the CNS cancer cell line.[

30] In particular, the compound 4c 2-(4-fluorophenyl)-5-(toluene-4-sulfonyl)-1,3-oxazole-4-carbonitrile demonstrate growth inhibition against glioblastoma cells SF-268 (GI

50=4.61µM) and SF-539 (GI

50=2.44 µM) and indicate low cytotoxicity with values LC

50 >100 µM. Therefore, the anticancer activity against CNS cancer of sulfonyl derivatives of 2-phenyl-4-cyano-1,3-oxazoles can be improved by inserting a piperazine moiety having multiple biotargets.

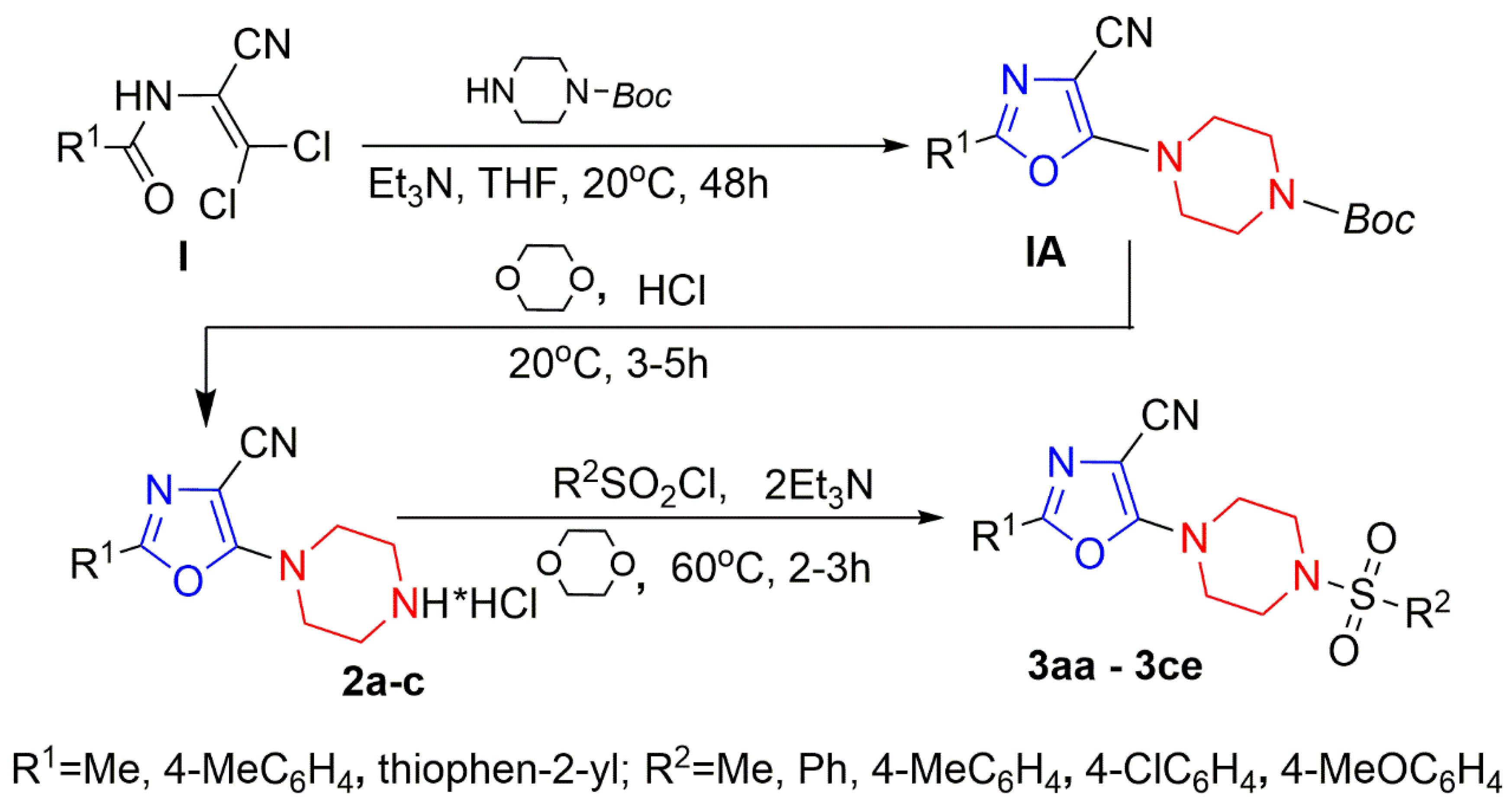

Synthesis of the target 5-(piperazin-1-yl)oxazole-4-carbonitriles

2a-с and

3aa-3ce was carried out as follows (

Scheme 1). First, the appropriate 2-acylamino-3,3-dichloroacrylonitriles

I were dissolved in anhydrous THF, in the presence of triethylamine, and then Boc-protected piperazine was added, and the reaction mixture was stirred at 20–25 °C for 48h. To remove the Boc-protecting group, the intermediate products

IA were dissolved in dioxane, and hydrogen chloride gas was bubbled through the solution for 30 min. The reaction mixture was then left to stand for 24h. With the corresponding 5-(piperazin-1-yl)oxazole-4-carbonitrile hydrochlorides (

2a-2c) in solution 1,4-dioxane, triethylamine was added, followed by the appropriate sulfonyl chloride. The reaction mixture was stirred and refluxed for 8h. The final products

3aa-3ce were purified by recrystallization from EtOH.

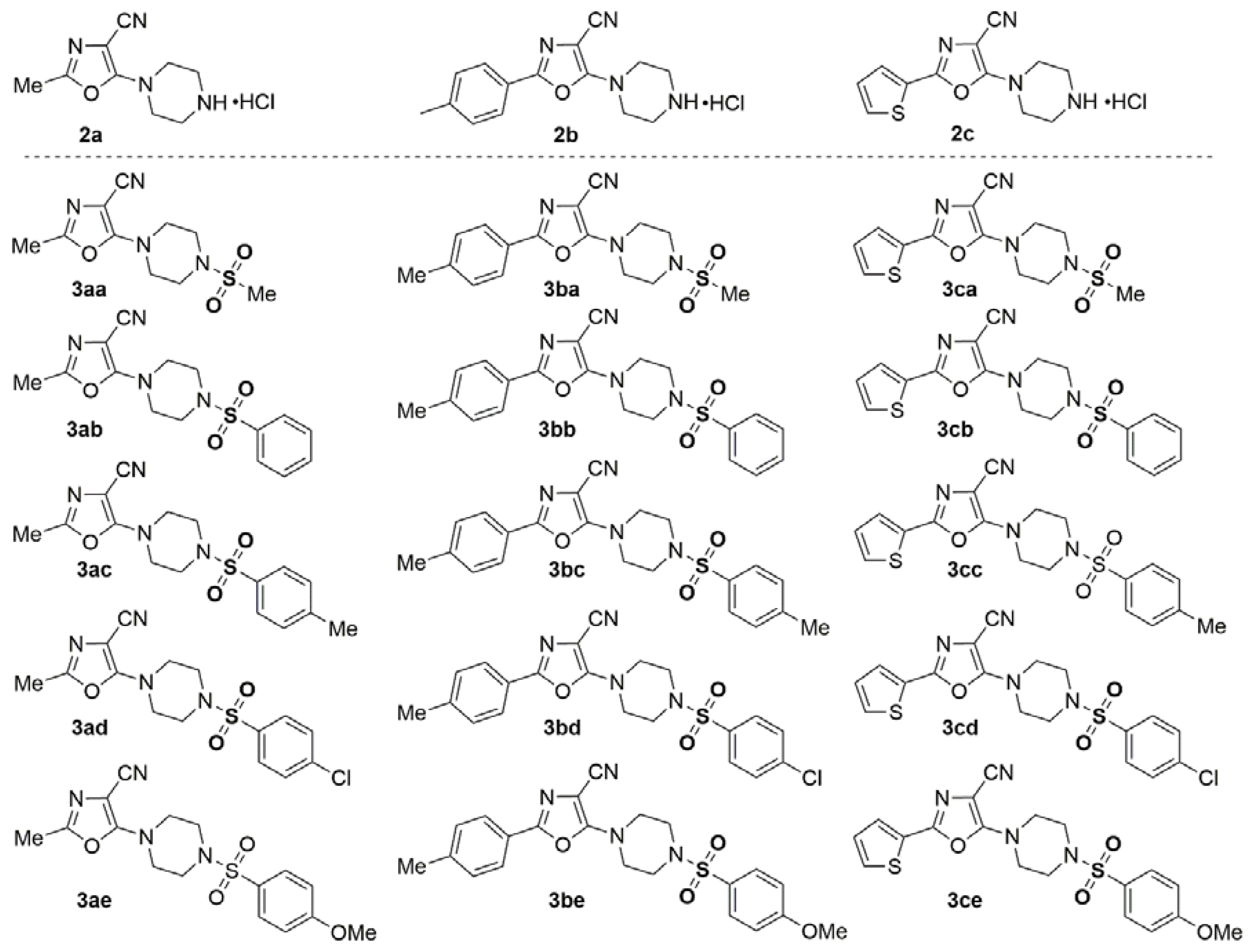

The structure synthesized compound

2a – 2c and

3aa – 3ce shown in

Figure 4.

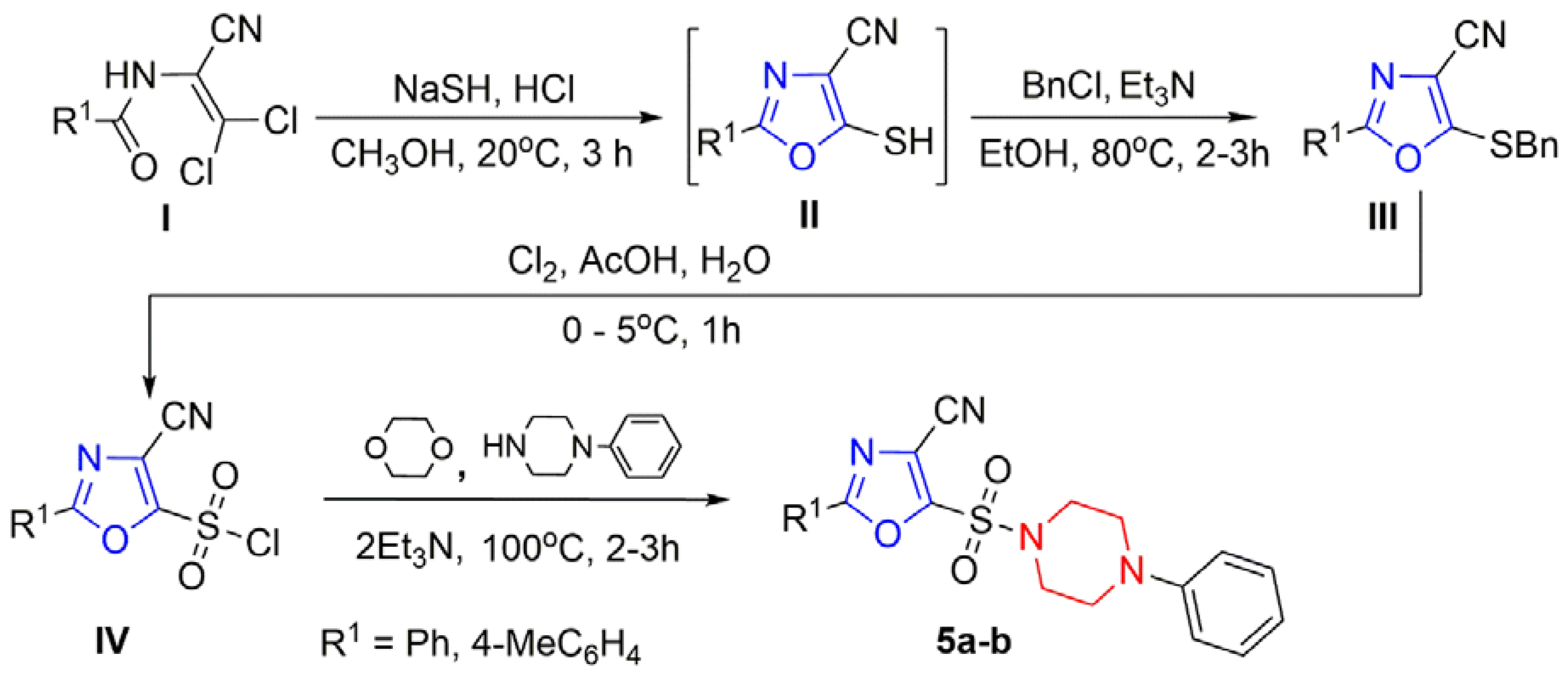

The target 5-(piperazin-1-ylsulfonyl)oxazole-4-carbonitriles were synthesized according to the procedure (

Scheme 2). The corresponding 2-acylamino-3,3-dichloroacrylonitriles

I were used as starting materials. Their reaction with an excess of NaSH in methanol solution lead to cyclization, yielding substituted 5-mercaptooxazoles

II. Alkylation of compounds 2 with benzyl chloride in ethanol in the presence of triethylamine afforded substituted 1,3-oxazoles 3 bearing a benzylthio group at position 5 of the oxazole ring. Oxidative chlorination of compounds

III in aqueous acetic acid at 0-5 °C produced 2-aryl-4-cyano-1,3-oxazole-5-sulfonyl chlorides

IV. Reaction of these intermediates with 1-phenylpiperazine in dioxane in the presence of excess triethylamine gave the corresponding 2-aryl-5-(4-phenylpiperazin-1-yl)sulfonyl-1,3-oxazole-4-carbonitriles

5a, 5b (

Scheme 2).

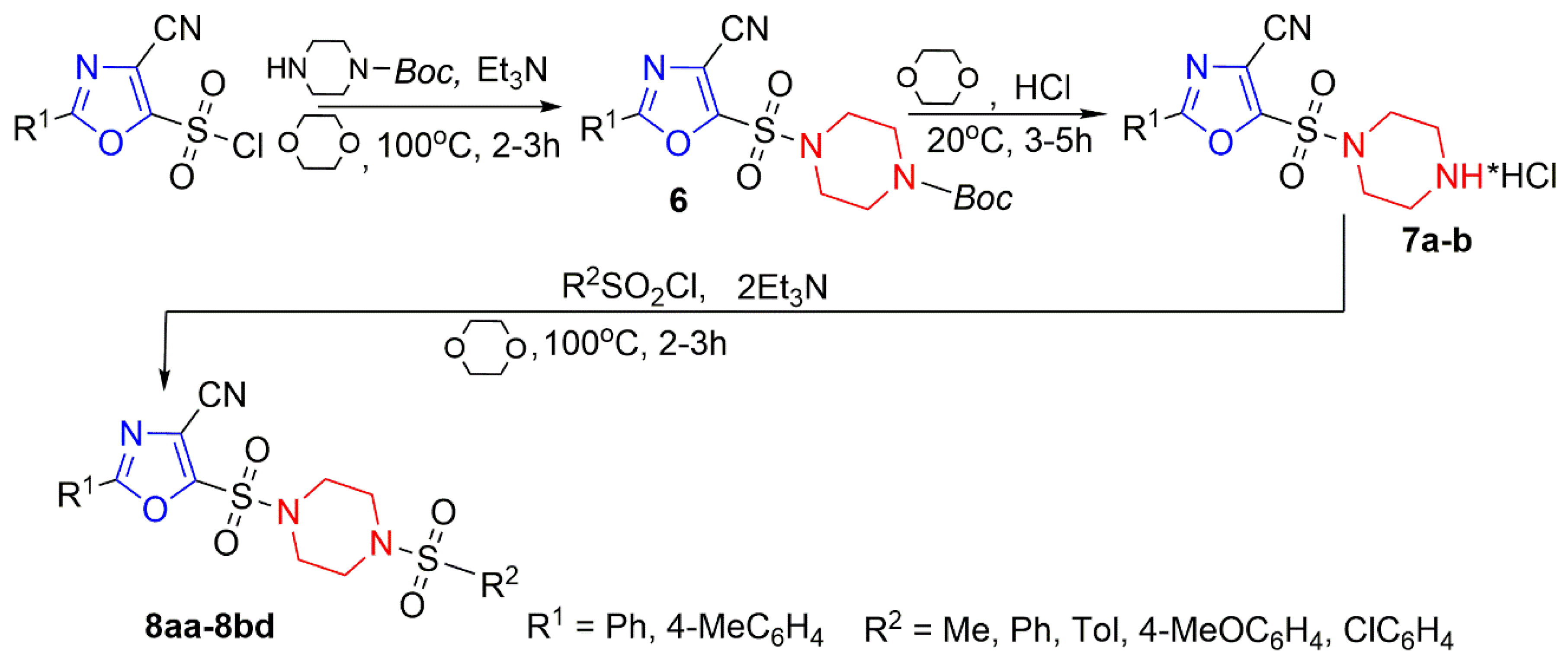

Next, the substituted 4-cyano-1,3-oxazole-5-sulfonyl chlorides

4 with Boc-piperazine gave the corresponding Boc-protected sulfonamides

6. Passing gaseous HCl through a dioxane solution of sulfonamides

6 resulted in the removal of the Boc protecting group and the formation of sulfonamide hydrochlorides

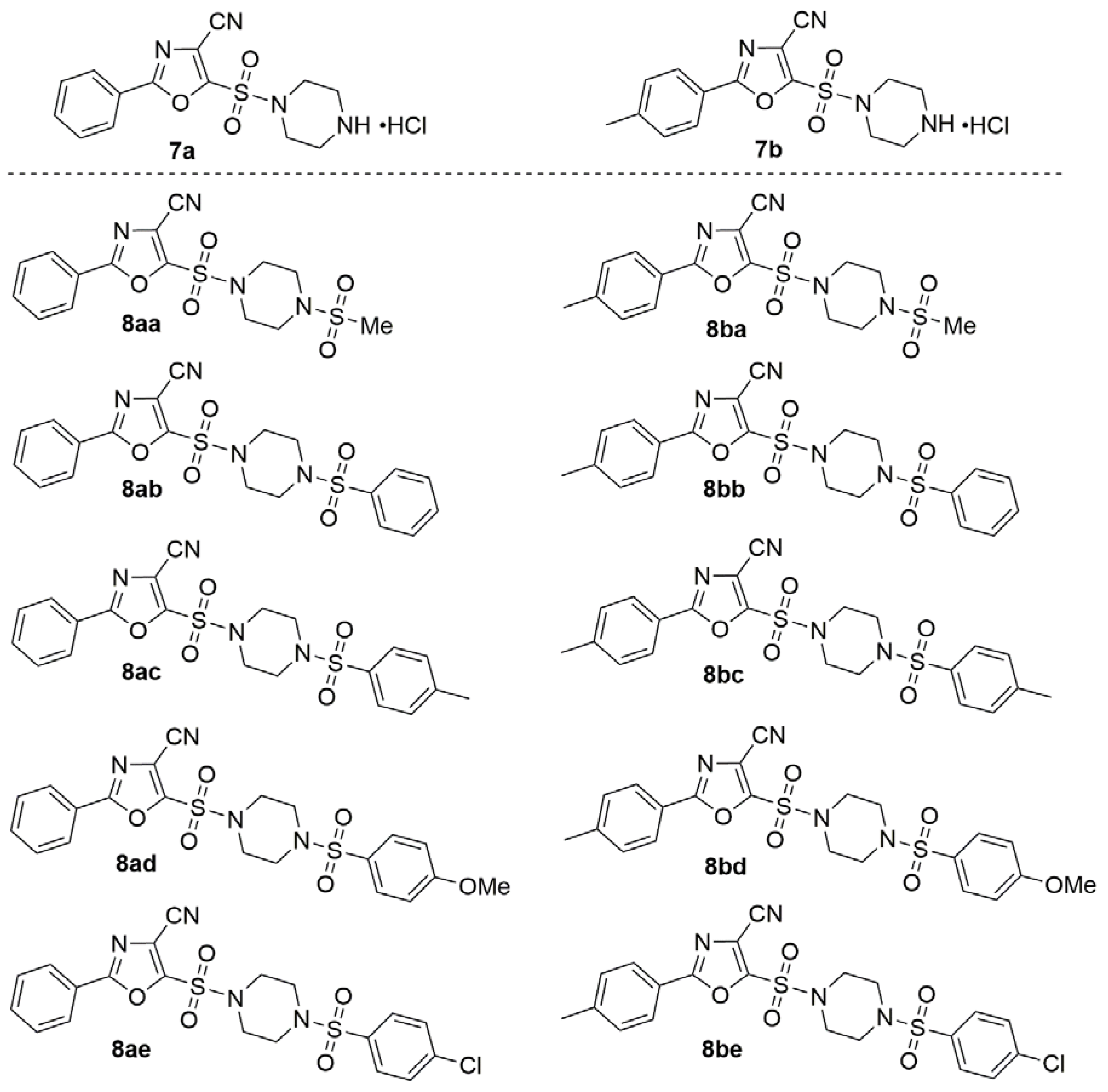

7a, 7b. Finally, the reaction of these compounds with the corresponding sulfonyl chlorides yielded sulfonamides

8aa–8bd, containing two sulfonyl groups connected by a piperazine linker (

Scheme 3) and structure synthesized compound 7

a – 7b and

8aa – 8bd shown in

Figure 5.

The structure of the compounds

2a-2с, 3aa-3ce, 5a-5b, 7a–7b and 8aa-8bd was confirmed using the

1H,

13C NMR and FTIR spectroscopy, HPLС, and elemental analysis (see Supporting Information

Figure S1–S96b).

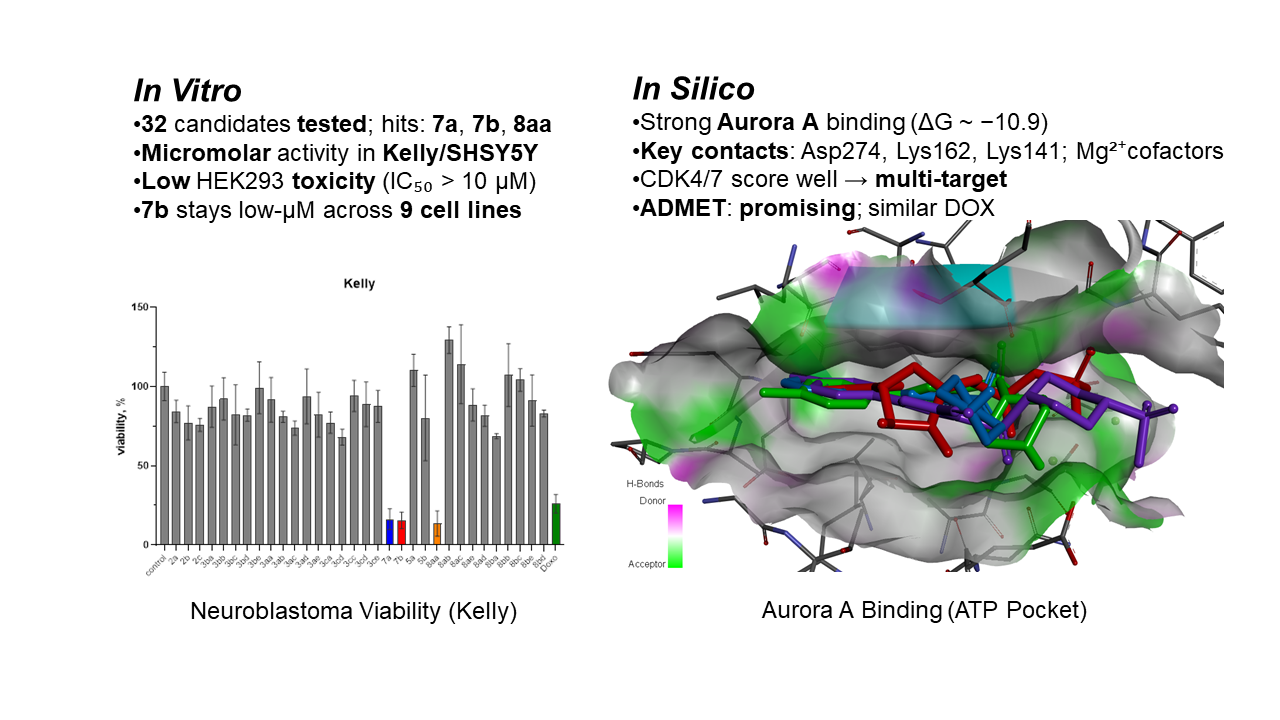

3.2. Biology. In Vitro Cytotoxicity

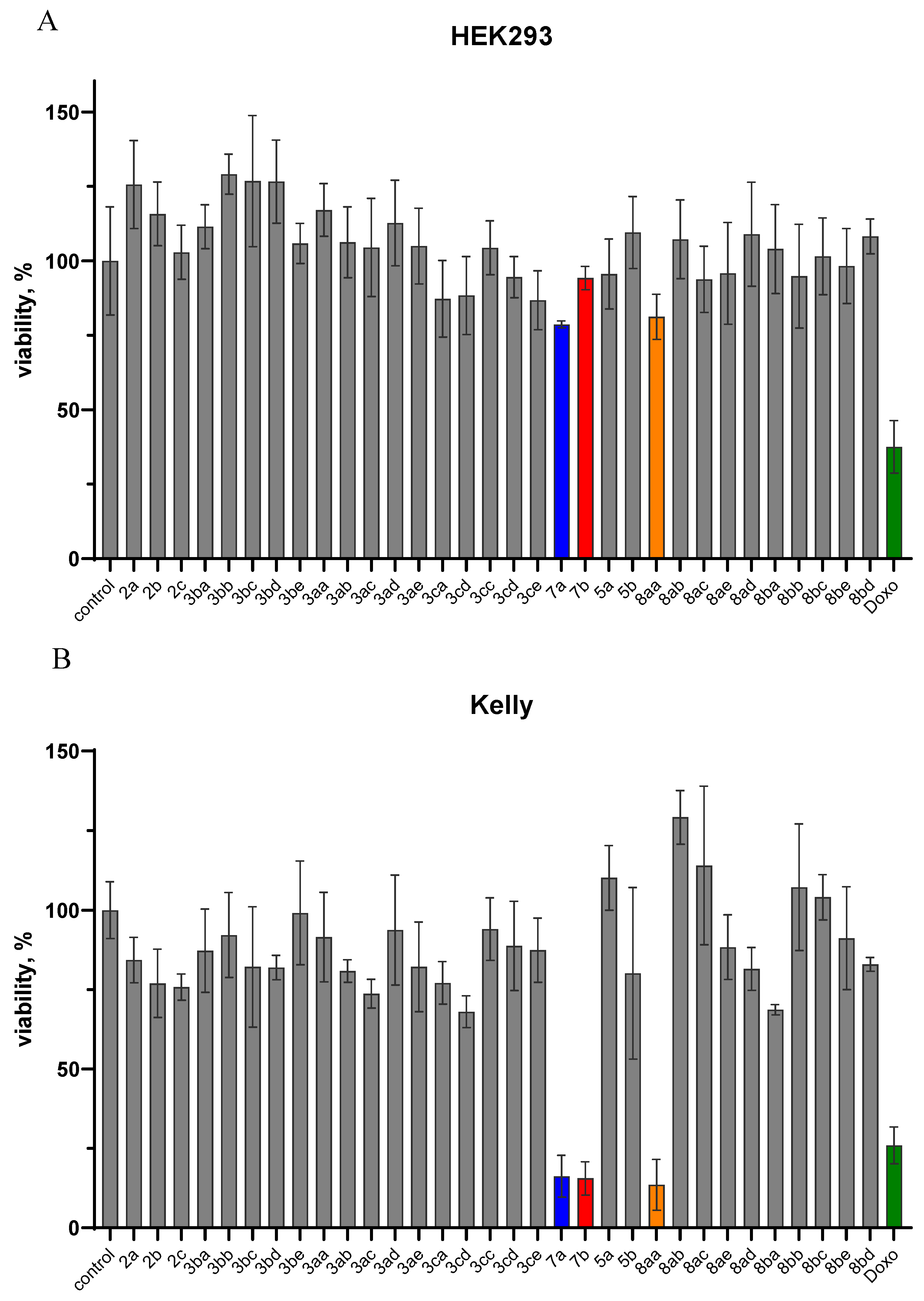

To evaluate the anticancer potential of the synthesized compounds, a preliminary cytotoxicity screen was conducted at a fixed concentration of 2.5 µM using the WST-1 assay in a neuroblastoma Kelly cells and non-malignant human embryonic kidney cell line HEK293, shown in

Figure 6.

The data for Kelly cells revealed significant sensitivity to a subset of compounds,

7a,

7b, and

8aa, which induced a marked reduction in viability. The mean viability for this compound is below 25% (2.5 µM). As illustrated in

Figure 6, non-malignant HEK293 cells maintained high viability upon treatment with most compounds, with viability values consistently above 80% for over 75% of the compounds tested. This result suggests a low baseline toxicity profile in non-cancerous cells, a critical consideration for minimizing off-target effects in future therapeutic applications. This difference highlights potential selective cytotoxic effects and justifies these compounds for further dose-dependent analysis. Such selectivity is particularly promising for neuroblastoma, a cancer with high unmet clinical need and frequent resistance to conventional chemotherapies. To further quantify the cytotoxic potency of the most active candidates, compounds

7a,

7b, and

8aa were subjected to concentration-dependent studies over a 48-hour period in Kelly and SHSY5Y neuroblastoma cells, and non-malignant cells HEK293. IC

50 values were calculated from nonlinear regression curves fitted to WST-1 absorbance data (450 nm), as shown in

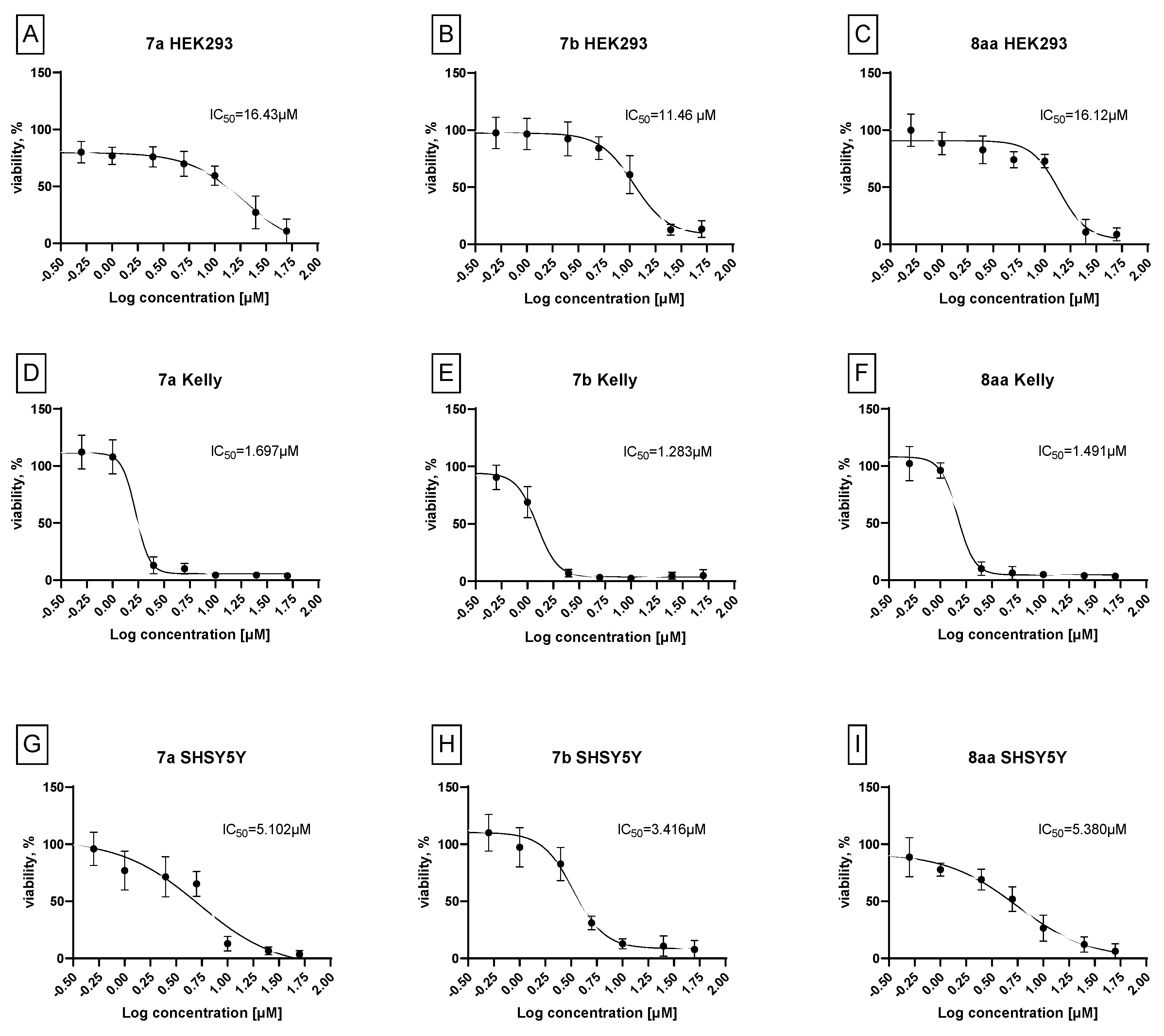

Figure 7 panels A–I.

The Kelly cells (panels D–F), see

Figure 7, exhibited robust sensitivity for compound

7a with IC

50 = 1.7 µM, compound

7b displayed the most potent effect with IC

50 = 1.3 µM, and compound

8aa showed IC

50 = 1.5 µM. These values indicate a selective cytotoxic effect in neuroblastoma cells relative to HEK293, suggesting possible tumor-targeted activity. Interestingly,

SHSY5Y cells

(panels G–I)—another human neuroblastoma line—also responded to the same compounds but with slightly higher IC

50 values (in the range of

3.4–5.4 µM), indicating variable sensitivity among neuroblastoma subtypes. This result could reflect differences in p53 status, metabolic activity, or drug uptake mechanisms, which are known to vary across neuroblastoma models. In

HEK293 cells (panels A–C), all three compounds showed relatively high IC

50 values (>10 µM), confirming their low cytotoxicity in non-cancerous cells even at elevated concentrations. This low background toxicity supports the potential therapeutic index of these agents. Taken together, these results demonstrate that compounds

7a,

7b, and

8aa exhibit promising and reproducible selective cytotoxicity across two independent neuroblastoma models, while sparing non-cancerous cells. To evaluate the potency of these novel agents, we compared their activity with

doxorubicin, a clinically established chemotherapeutic agent widely used against solid tumors, including neuroblastoma. Doxorubicin’s IC

50 was determined in both HEK293 and Kelly cells (

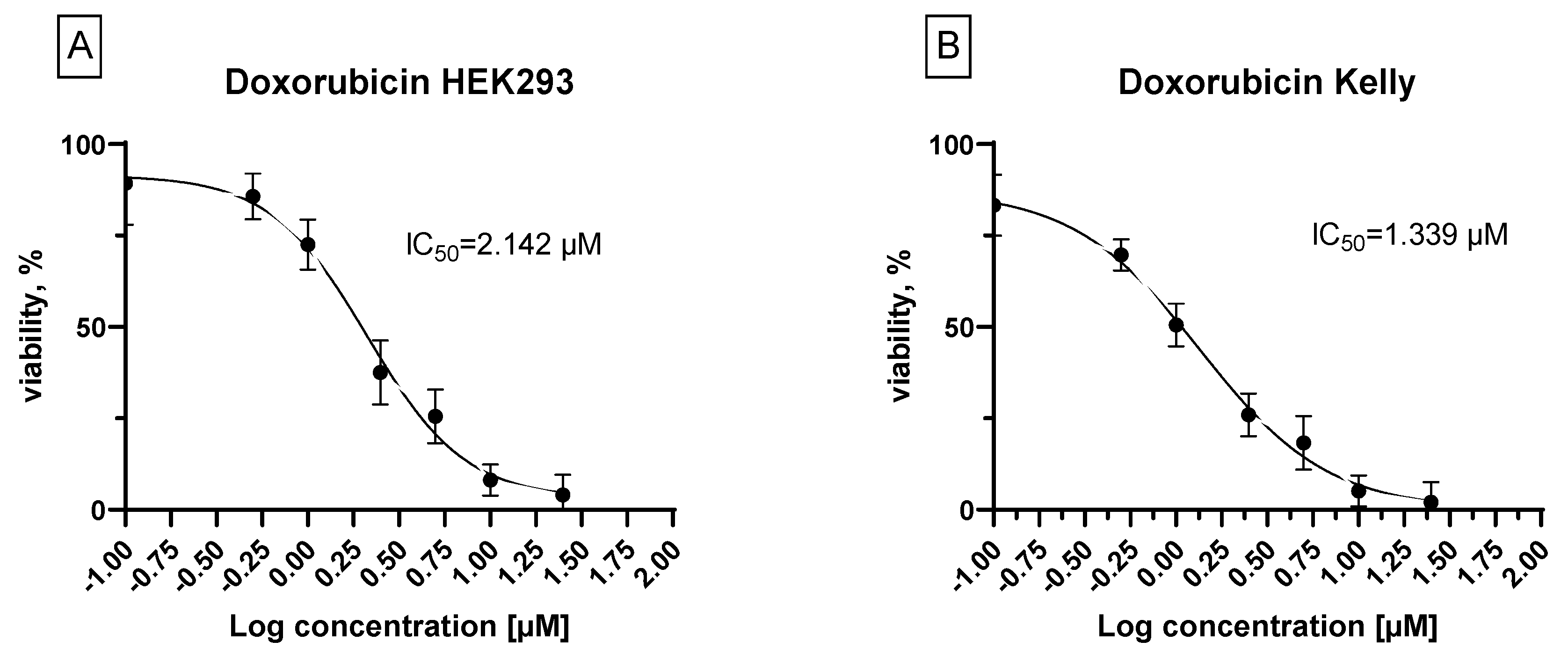

Figure 8A and 8B, Doxorubicin panel).

In Kelly cells, the IC50 was approximately 1.3 µM, comparable to compound 7b. In HEK293, doxorubicin showed a moderate cytotoxic profile (IC50=2.1 µM), indicating appreciable off-target toxicity. These findings underscore the selective advantage of compound 7b, which matches doxorubicin’s potency in neuroblastoma while demonstrating significantly reduced toxicity in non-malignant cells. This improved therapeutic index could minimize adverse effects associated with systemic chemotherapy and suggests a safer profile for clinical translation.

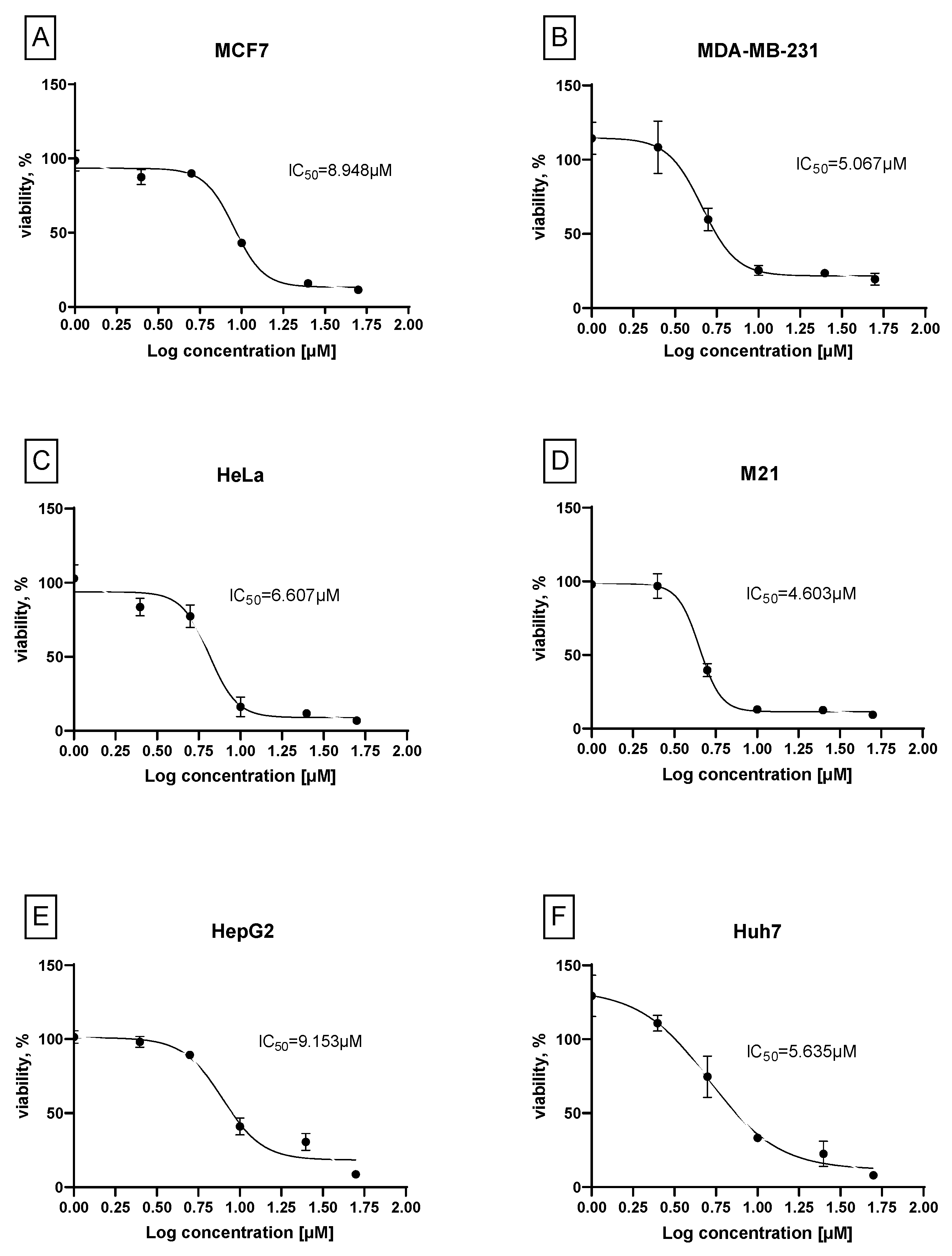

Next, the compound

7b was subsequently evaluated for its cytotoxic efficacy across a diverse panel of human cancer cell lines, including: hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2, Huh7), breast cancer (MCF7, MDA-MB-231), cervical cancer (HeLa), melanoma (M21) and neuroblastoma cell lines (Kelly, SHSY5Y) and demonstrated in

Figure 9.

As shown in the

Figure 9 panel, compound

7b demonstrated micromolar IC

50 values (1.3–9.1 µM) across all cancer lines tested, with the most pronounced sensitivity observed in

Kelly, SHSY5Y and

M21 cells. This broad cytotoxic activity suggests that compound

7b may interfere with fundamental cellular pathways such as cell cycle regulation or apoptotic signaling that are commonly dysregulated across multiple tumor types. The activity across genetically diverse cancer models positions

7b as a potential candidate for broad-spectrum oncologic indications, pending further mechanistic investigation.

3.2.1. Selectivity Index

To assess the therapeutic window and tumor-targeting selectivity of the synthesized oxazole derivatives, we calculated the selectivity index (SI) as the ratio of IC50 values in non-malignant HEK293 cells to those in malignant neuroblastoma cells (Kelly and SHSY5Y). Compounds 7a, 7b, and 8aa demonstrated pronounced selectivity toward neuroblastoma cells. Specifically, compound 7b exhibited an IC50 of approximately 1.3 µM in Kelly cells and >10 µM in HEK293 cells, yielding an SI > 7.7. Compound 7a showed an IC50 of ~1.7 µM in Kelly and >10 µM in HEK293, corresponding to an SI > 5.9. Likewise, compound 8aa displayed an IC50 of ~1.5 µM in Kelly and >10 µM in HEK293 cells, resulting in an SI > 6.7. In contrast, the reference chemotherapeutic agent doxorubicin exhibited comparable cytotoxicity across both cell types, with IC50 values of ~1.3 µM in Kelly and ~2.1 µM in HEK293 cells, yielding a selectivity index of approximately 1.6. These findings highlight the superior selectivity profile of compounds 7a, 7b, and 8aa, which effectively target malignant neuroblastoma cells while sparing non-malignant cells. This selective cytotoxicity is particularly valuable in pediatric oncology, where minimizing off-target toxicity to developing tissues remains a significant clinical challenge. Overall, the favorable SI values observed suggest that these compounds represent promising candidates for the development of safer and more tumor-specific therapeutics for neuroblastoma treatment.

3.3. Biodegradability Study.

Active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), their metabolites/transformation products are found as pollutants in the environment, impacting human and environmental health. Designing APIs with high biodegradability is desirable but there is no clear agreement how to implement these criteria in practice.[

31]

In the CBT, the term “readily biodegradable” refers to that pass the test with 60% or higher degradation, indicating they will biodegrade rapidly and completely in aquatic environments under aerobic conditions. The CBT experiments were run for 28 days, each day the oxygen concentration was measured and logged for each of the duplicates in the series. The three compounds

7a,

7b, and

8aa did not show any significant biodegradation as the biodegradation % of all the three compounds after 28 days is only 5-10% and did not pass readily biodegradability test. The graphs are given on

Figure S97.

Low biodegradability is caused by either toxicity of the studied compounds to the inoculum bacteria or their persistence under experimental conditions. The oxazoles

7a,

7b, and

8aa demonstrated relatively low toxicity against the healthy cells and did not affect the toxicity control in the CBT, see

Figure S97, confirming they remain chemically intact under CBT conditions. Indeed, environmental (bio)degradability helps in designing hit compounds that resist breakdown by enzymes in the human body, yet finding a ‘window of opportunity’ where such hits are both metabolically stable enough and environmentally biodegradable remains a challenge.[

31,

32]

3.4. Molecular Modelling

Molecular docking of ligands

7a,

7b, and

8aa was performed using three-dimensional structures obtained from the RCSB Protein Data Bank [

33] and the following protein crystal structures were used: anaplastic lymphoma kinase in complex with Crizotinib - ALK (PDB ID: 2XP2); cyclin-dependent kinase series CDK2 (PDB ID: 3QXO), CDK4 (PDB ID: 7SJ3), CDK6 (PDB ID: 8I0M), CDK7 (PDB ID: 1UA2), CDK9 (PDB ID: 6Z45). Also the checkpoint kinase 1 - CHK1 (PDB ID: 1ZYS), apoptosis regulator BCL2 (PDB ID: 4LVT), Aurora-A kinase in complex with N-Myc (PDB ID: 5G1X) and poly[ADP-ribose] polymerase 1 PARP1 (PDB ID: 6I8T). First, molecular docking techniques were validated using redocking co-crystallized ligands into the proteins. Docking scores from AutoDock Vina (reported as estimated binding free energies, ΔG, in kcal/mol). Next, molecular docking of compounds

7a,

7b, and

8aa was performed, and the results of which are presented in

Table 1 and

Figure 10.

Сo-crystallized ligands:[

34] [a] 5-nitro-2-[(4-sulfamoylphenyl)methylamino]benzamide; [b] 2-[(4-aminocyclohexyl)amino]-7-cyclopentyl-

N,N-dimethylpyrrolo [2,3-d]pyrimidine-6-carboxamide; [c] Adenosine 5′-triphosphate; [d] (1S,3R)-3-acetamido-

N-[5-chloro-4-(5,5-dimethyl-4,6-dihydropyrrolo [1,2-b]pyrazol-3-yl)pyridin-2-yl]cyclohexane-1-carboxamide; [e]

N-[5-[4-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)phenyl]-1

H-pyrrolo [2,3-b]pyridin-3-yl]pyridine-3-carboxamide; [f] adenosine 5′-diphosphate; [g] (1R)-2-(1-cyclohexylpiperidin-4-yl)-1-methyl-3-oxo-1

H-isoindole-4-carboxamide.

Table 1 presents successful molecular docking validation by redocking co-crystallized ligands into the active sites of the target proteins: ALK kinase, as well as cyclin-dependent kinases CDK2, CDK4, CDK6, CDK7, CDK9, and CHK1 kinase, BCL2 and Aurora A kinase, and polymerase PARP1. The registered binding energies (∆G) for these protein-ligand interactions varied from -8.2 to -11.5 kcal/mol, and RMSD values were 1.01–2.33 Ǻ. According to the results of molecular docking, the most stable protein-ligand complexes of compounds

7a,

7b, and

8aa were observed for the Aurora A kinase, with values of ∆G ranging from -10.8 to -10.9 kcal/mol. Molecular docking of these compounds into the remaining proteins did not show high complexation energies ∆G (from -7.2 to -9.1 kcal/mol). It is worth noting that the studied compounds exhibit some kinase activity, as confirmed by the average values of binding energy (∆G = −7.9–9.1 kcal/mol) in the ATP-binding centers of cyclin-dependent kinases (CDK2, CDK4, CDK6, CDK7, and CDK9), which is comparable to the redocking energy of ligands (∆G = −8.2–9.3 kcal/mol). The low energy of the complexation was demonstrated by ALK kinase (∆G = -7.1 to -7.5 kcal/mol) and the apoptosis regulator BCL2 (∆G = -7.4 to -8.0 kcal/mol). Thus, the most energetically favorable complexation for the studied compounds was found to occur in the ATP-binding site of the aurora A kinase, with a ΔG value of -10.8 to -10.9 kcal/mol, which is equal to the binding energy of adenosine 5′-diphosphate (ADP) with ∆G = -10.9 kcal/mol. This observation is consistent with the literature. First-generation Aurora A inhibitors are ATP-competitive molecules, many of which have progressed into different stages of clinical evaluation.

40 Successful piperazine-containing Aurora A kinase inhibitors include ENMD-2076

41 and VX-680

42, both evaluated in clinical studies. Next, we will study the effective molecular docking of compounds

7a,

7b, and

8aa into the ATP-binding site of Aurora A kinase (

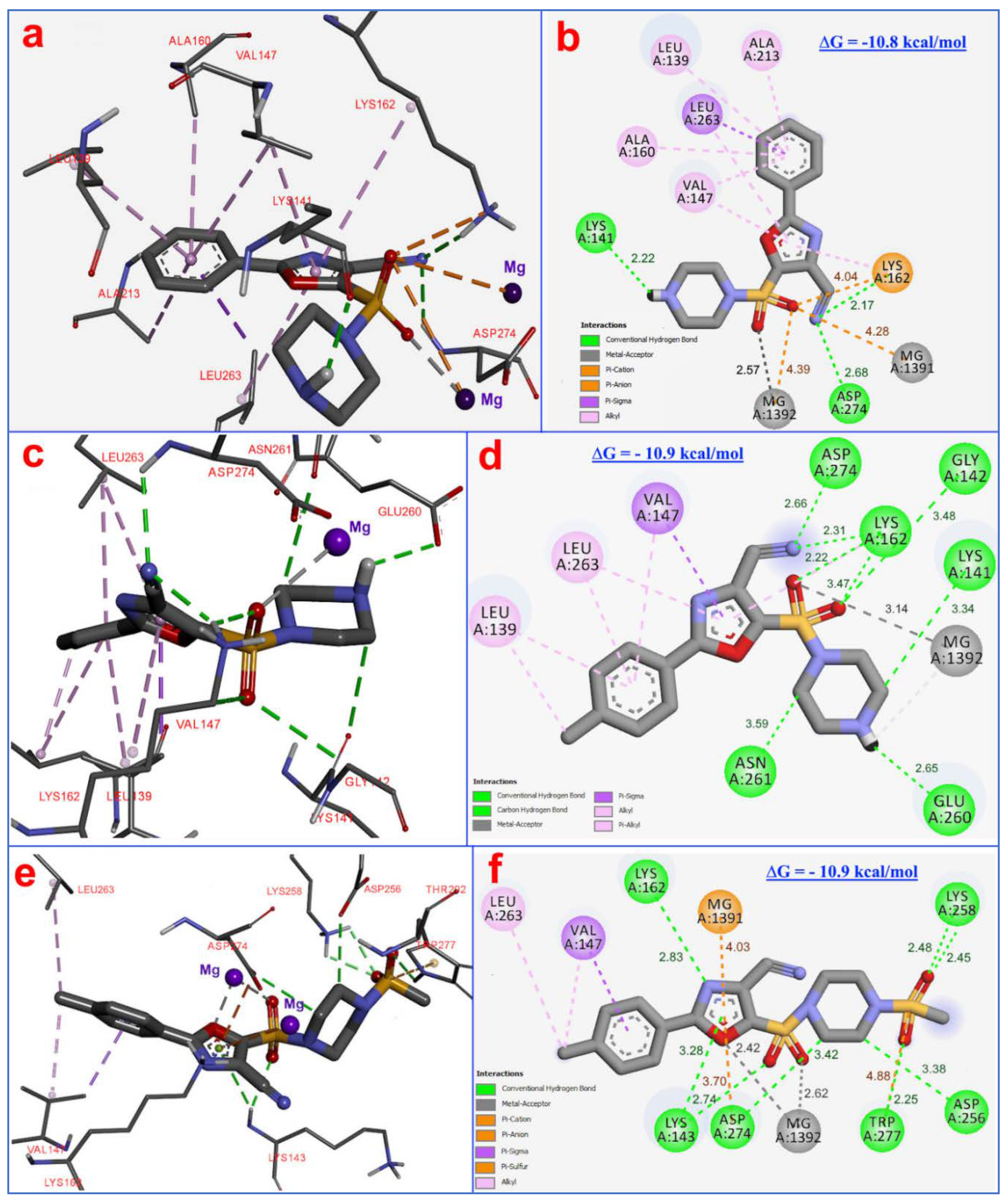

Figure 11).

The

Figure 11 illustrates the result of the molecular docking of compounds

7a,

7b, and

8aa into the ATP-binding site of Aurora A kinase. The complexation of compound

7a (

Figure 11a

, b) with a binding energy of ∆G= −10.8 kcal/mol is stabilized three hydrogen bonds; two hydrogen bonds form between the carbonitrile group of compound and amino acids Asp274 (2.68Ǻ) and Lys162 (2.17Ǻ), and one bond between the piperazine moiety and the amino acid residues Lys141 (2.22Ǻ). This ligand-protein complex is also stabilized by three electrostatic interactions between the compounds’ sulfonyl group, the amino acid Lys162 (4.04Ǻ), and the cofactors Mg

2+ (4.28–4.39Ǻ). It is essential to note the formation of one metal-acceptor interaction (2.57Ǻ) among the cofactor Mg

2+ and the compounds’ sulfonyl group. Also, this complex is stabilized by eight hydrophobic bonds (3.95–5.36Å) with amino acids Ala160, Lys162, Leu139, Val147, and Leu263 with bond distances 3.92–5.08Å.

The ligand-protein complex of compound

7b (

Figure 11c

, d) with a binding energy of ∆G= −10.9 kcal/mol is stabilized eight hydrogen bonds; two H-bonds between the compound carbonitrile group and amino acid residues Asp274 (2.66Ǻ) and Lys162 (2.31Ǻ), three H-bonds among the sulfonyl group and the amino acids Lys162 (2.22–3.47Ǻ), and Gly142 (3.48Ǻ), and three H-bonds between piperazine ring and amino acids - Lys141 (3.48Ǻ), Glu260 (2.65Ǻ) and Asn (3.39Ǻ). Also present is one metal-acceptor interaction (3.14Ǻ) among the cofactor Mg

2+ and the compounds’ sulfonyl group. Furthermore, this ligand-protein complex is stabilized by seven alkyl and Pi-alkyl hydrophobic bonds (3.75–5.43Å) with amino acids Leu139, Val147, Lys162, and Leu263.

The compound

8aa ligand-protein complex (

Figure 11e

, f) is characterized by a binding energy of ∆G= −10.8 kcal/mol, which is stabilized also by eight hydrogen bonds. The first sulfonyl group forms two H-bonds with Lys258 (2.45–2.48Ǻ), and two H-bonds form between the piperazine ring and amino acids Asp256, Asp274 (3.38–3.42Ǻ). The second sulfonyl group forms one H-bond with Lys143 (2.74Ǻ), and also the oxazole ring forms two H-bonds with the amino acid residues Lys143 (3.28Ǻ) and Lys162 (2.83Ǻ). The cofactor Mg1392 forms two metal-acceptor interactions with the oxazole ring (2.42Ǻ) and the second sulfonyl group (2.62Ǻ). Also, this ligand-protein complex is stabilized by three electrostatic interactions: between the compounds’ first sulfonyl group and Trp277 (4.88Ǻ); among the oxazole ring and cofactor Mg1391 (4.03Ǻ), and the amino acid Asp274 (3.70Ǻ). Besides, the ligand-protein complex is stabilized by three hydrophobic bonds (3.63–4.79Å) with amino acids Val147 and Leu263. Thus, the molecular docking results of compounds

7a,

7b, and

8aa into the ATP-binding site of human Aurora A kinase are characterized by high binding energy, forming multiple H-bonds, electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions, and forming metal-acceptor interactions of compounds with Mg

2+ cofactors. Investigating the possible anticancer mechanism of action of compounds

7a,

7b, and

8bb by molecular docking demonstrates a binding model to the active site similar to the ADP molecule (

Figure 12).

Our docking studies with the structure of Aurora-A kinase (PDB ID: 7ZTL) also confirm this binding model.[

35] Next, the pharmacokinetic aspects of compounds

7a,

7b, and

8aa were investigated by ADMET 3.0 web tool.

3.5. Biology and Molecular Docking Results Discussion

The high energetically complexation of the compounds

7a,

7b, and

8aa with the ATP-binding site of the Aurora A kinase, with a ΔG value of -10.8 to -10.9 kcal/mol (ADP ∆G = -10.9 kcal/mol), is in good agreement with the literature data. So, Aurora A inhibitors of the I-generation are ATP-competitive inhibitors that bind to the ATP-binding site, and the majority of these inhibitors are currently in various phases of clinical investigation. [

36] A successful example is the piperazine-containing Aurora A kinase inhibitor (IC

50=1.86 nM) ENMD-2076, 6-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)-

N-(5-methyl-1

H-pyrazol-3-yl)-2-[(E)-2-phenylethenyl]pyrimidin-4-amine, which is currently in Phase I/II clinical trials.[

37] In the literature, a selective Aurora A inhibitor (IC

50 = 0.6 nM), Tozasertib (VX-680),

N-[4-[4-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)-6-[(5-methyl-1

H-pyrazol-3-yl)amino]pyrimidin-2-yl]sulfanylphenyl]cyclopropanecarboxamide, is described.[

38]

It is also known that a number of Aurora A kinase inhibitors that bind to the ATP binding site cause significant conformational changes in the Aurora A kinase structure, preventing binding to oncoprotein N-Myc and disrupting the formation of the Aurora A/N-Myc complex. The formation of this complex plays a crucial role in stabilizing the oncoprotein N-Myc, as key transcription factor that regulates cell cycle progression, cell proliferation, and the metastasis of neuroblastoma. Given the more favorable (i.e., more negative) binding energies compared to the reference observed in our study, Aurora A kinase represents a plausible molecular target for these compounds. In our opinion, the high antiproliferative activity of compounds

7a,

7b, and

8aa against neuroblastoma cells Kelly expressing N-MYC on the cell surface is associated with their high energy of complex formation in the ATP-binding center of Aurora A kinase, disruption of its conformation, and, as a consequence, destabilization of the oncoprotein N-Myc with antimitotic and antiproliferative action. This hypothesis is supported by literature data, indicating the development of specific methods for targeting Aurora A in cancer treatment, which initially concentrated on designing various Aurora A kinase inhibitors and are currently in clinical trials.[

39] However, this conclusion requires biochemical confirmation (e.g., kinase activity assays, N-MYC degradation analysis).

Unlike Kelly cells, SHSY5Y cells do not harbor MYCN amplification and are therefore less dependent on Aurora A–mediated stabilization of the MYCN protein. Nevertheless, SHSY5Y cells remained sensitive to treatment with our compounds, albeit with slightly higher IC

50 values (3.4–5.4 µM), suggesting that alternative molecular pathways may be involved in mediating this response. Importantly, SHSY5Y cells have previously been shown to respond to pharmacological inhibition of CDKs. For instance, the selective CDK4/6 inhibitor Palbociclib induces G1 phase arrest and suppresses proliferation in neuroblastoma models, including SHSY5Y.[

40] Moreover, CDK9 and CDK7—key regulators of transcriptional elongation via phosphorylation of RNA polymerase II—are increasingly recognized as therapeutic vulnerabilities, particularly in MYCN-low or MYCN-negative neuroblastoma subtypes.[

41] Our docking data indicate robust predicted affinities for multiple cyclin-dependent kinases (CDK4 and CDK7 with ΔG = –9.0 to –9.1 kcal/mol) for compounds 7a, 7b, and 8aa. Given the favorable docking scores against these kinases, it is possible that part of their cytotoxic effect, particularly in SHSY5Y cells, may be mediated by inhibition of CDK-driven cell cycle and transcriptional programs.

This evidence suggests a broader multi-target profile for compounds

7a–8aa, whereby cytotoxicity may result from concurrent disruption of both mitotic (Aurora A) and transcriptional/cell cycle (CDK) pathways. Such multitargeted activity is increasingly seen as a beneficial trait in cancer therapy, offering enhanced efficacy and a reduced likelihood of resistance emergence, especially in aggressive pediatric malignancies.[

42] In support of this interpretation, we also observed that the lead compound

7b exhibited cytotoxic potency in a range of non-neuroblastoma tumor cell lines. For example, IC

50 values remained in the low micromolar range in M21 (melanoma), MCF7 (breast), and Huh7 (hepatocellular carcinoma) cells, indicating that it exhibits activity in tumor cells with high proliferative indices. This pattern is consistent with the mechanism of action for many cytotoxic small molecules that interfere with cell cycle progression, mitotic spindle formation, or transcriptional regulation, all of which are commonly dysregulated in fast-growing cancers. [

43]

Altogether, these findings suggest that the therapeutic potential of these oxazole derivatives may extend beyond neuroblastoma and merit evaluation in other high-proliferation tumor types. As multi-target drugs continue to gain attention in drug development, their ability to regulate simultaneously multiple links of disease and improve efficacy make them ideal drugs for treating complex diseases.[

44] Nonetheless, targeted experimental validation, e.g., kinase activity assays, flow cytometry for G1/S or G2/M arrest, and transcriptomic profiling may be required to precisely delineate the molecular contributions of Aurora A and CDK inhibition in the observed anticancer effects.

3.6. ADMET Evaluation

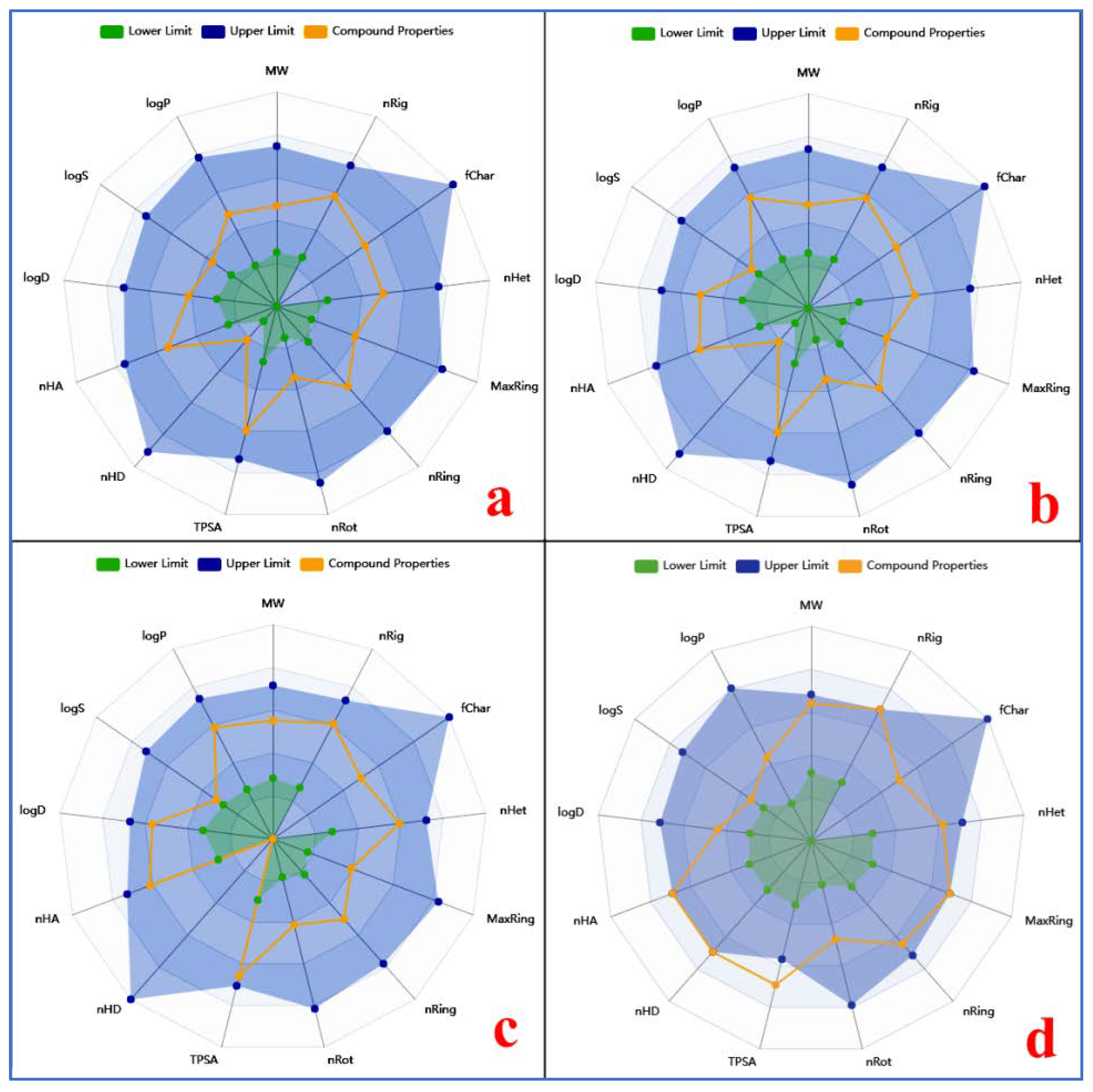

Table 2 presents the significant ADMET properties of compounds 7a, 7b, 8aa, and doxorubicin (to compare) as calculated using the online ADMETlab 3.0 web server.

The synthesized compounds exhibited acceptable physicochemical properties, including a rotatable bond count of (3-4) and a count of hydrogen bond donors (0-1) and acceptors (7-9). The topological polar surface area of compounds

7a, 7b, and

8aa is 127-157 Å

2, which is slightly lower than the doxorubicin value (222 Å

2). The coefficient lipophilicity (logP) of compounds is in the acceptable range (0–3 log mol/L) and is 1.424 for compound 7a and 1.208 for doxorubicin. The compounds

7b and

8aa exhibit higher lipophilicity, with values of 2.013 and 2.048, respectively. The values of BBB permeability of compounds

7a (-0.822) and 7b (-0.87) are below the permissible threshold (log BB < -1), and that of compound

8aa (-1.474) is slightly below the threshold and equal to the corresponding value of doxorubicin (-1.379). The values of CNS permeability for all are < 3 and are considered unable to penetrate the CNS. The absorption results show that compounds

7a and

7b are well permeable through intestinal cell membranes (logCaco-2 > 5.15), and compound 8aa has moderate permeability (logCaco-2 = −4.815). Compounds

7a and

7b do not interact with P-glycoprotein as a biological barrier; however, compound

8aa is a P-glycoprotein inhibitor. The excretion of all compounds is estimated by plasma clearance, which ranges from 5.762 to 6.382 ml/min/kg, indicating moderate clearance (5-15 ml/min/kg). The doxorubicin plasma clearance is 2 times higher, amounting to 14.244 ml/min/kg. Additionally, the results of the compounds’ half-lives are obtained, which range from 0.686 to 0.821 hours, representing an ultra-short half-life value (<1 hour). Doxorubicin has a value of 3.774 hours and is a short half-life drug. The toxicology properties of compounds

7a,

7b, and

8aa are characterized by positive hepatotoxicity (similar to doxorubicin) and a low tolerated dose log (mg/kg/day) from -0.158 to -0.554; this dose for doxorubicin is higher (0.081). The values of the rat oral acute toxic doses (LD

50) of compounds

7a, 7b, and

8aa are comparable to those of doxorubicin (2.4–2.5 mol/kg). Additionally,

Figure 13 illustrates the ADMET characteristics of compounds

7a, 7b, 8aa and doxorubicin as estimated by the ADMETlab 3.0 web server.

4. Conclusions

Thirty-two 5-piperazine-containing 1,3-oxazole-4-carbonitriles were rationally designed and synthesized in yields ranging from 68% to 83%. Their structures were confirmed by 1H, 13C NMR spectroscopy, HPLC, and elemental analysis. In in vitro cytotoxicity assays (WST-1), compounds 7a, 7b, and 8aa demonstrated reproducible micromolar activity against neuroblastoma cell lines (Kelly and SHSY5Y) while maintaining low toxicity toward non-malignant HEK293 cells (IC50 > 10 µM), resulting in favorable selectivity indices (SI > 5.9). Notably, 7b showed potency comparable to doxorubicin in Kelly cells but with substantially reduced toxicity in HEK293. Across a broader tumor panel, 7b retained low-micromolar IC50 values, suggesting potential utility in additional high-proliferation cancer types. Molecular docking of compounds 7a, 7b, and 8aa, targeting the anticancer mechanism, revealed their interaction with Aurora A kinase in complex with N-MYCN. The highest binding affinity for these compounds was observed at the ATP-binding site of Aurora A kinase, with calculated binding free energies of ΔG = −10.8 kcal/mol for 7a and ΔG = −10.9 kcal/mol for both 7b and 8aa, indicating Aurora A kinase as a potential molecular target. The resulting complexes were stabilized by hydrogen bonds with Asp274, Lys162, and Lys141; electrostatic interactions with Lys162 and the cofactor Mg2+; and hydrophobic interactions with Ala160, Lys162, Leu139, Val147, and Leu263. Additionally, a metal–acceptor interaction was observed between the Mg2+ cofactor and the sulfonyl group of the compounds during complex formation. Additional favorable docking scores were observed for cyclin-dependent kinases (CDK4, CDK7), raising the possibility of a multi-target mechanism involving both mitotic and transcriptional/cell cycle pathways. Predicted in silico ADMET parameters for 7a, 7b, and 8aa indicated acceptable physicochemical properties, moderate clearance, and oral bioavailability potential, but also suggested hepatotoxicity risk comparable to doxorubicin. The compounds 7a, 7b, and 8aa were shown to be not readily biodegradable under Closed Bottle Test (OECD 301D), indicating environmental persistence under aerobic aquatic conditions.

Overall, compounds 7a, 7b, and 8aa represent promising lead structures for further preclinical development against neuroblastoma, with potential extension to other rapidly proliferating solid tumors. The favorable in vitro selectivity and multi-target binding profile provide a strong rationale for continued optimization and mechanistic investigation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. (Appendix A): Procedure for synthesis of 2a–c with spectra and analysis data. Procedure for synthesis of 3aa–3ce with spectra and analysis data. Procedure for synthesis of 5a, 5b with spectra and analysis data. Procedure for synthesis of 7a, 7b with spectra and analysis data. Procedure for synthesis of 8aa–8be with spectra and analysis data. 1H NMR, 13C NMR, HPLC, and FTIR spectra of 2a–8be. Biodegradation study data and graphs (Table S1, Figure S97).

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript. Oleksandr O. Severin: Methodology; Investigation; Data curation; Writing—Original draft preparation; Denys Bondar: Methodology; Conceptualization; Investigation; Validation; Data curation; Visualization; Writing—Original draft preparation, Writing—Reviewing and Editing; Olga Bragina: Methodology; Investigation; Validation; Data curation; Visualization; Writing—Original draft preparation; Nandish M. Nagappa: Methodology; Conceptualization; Investigation; Validation; Data curation; Visualization; Janari Olev: Investigation; Validation; Data curation; Volodymyr S. Brovarets: Conceptualization; Resources; Funding acquisition; Writing- Reviewing and Editing; Ivan Semenyuta: Methodology; Conceptualization; Investigation; Validation; Data curation; Visualization; Writing—Original draft preparation; Writing—Reviewing and Editing; Yevgen Karpichev: Conceptualization, Methodology; Resources; Funding acquisition; Writing- Reviewing and Editing; Project administration.

Acknowledgments

In memory of Prof. Volodymyr S. Brovarets, whose contribution to conceptualization, accumulating resources, and preparation of this paper was impactful and alienable. Although he is no longer with us, his dedication to science continues to inspire our research. This study was financially supported by the Estonian Research Council via project COVSG5 (for D.B. and Y.K.), Estonian Ministry of Education and Research and Education and Youth Board scholarship (for O.O.S.). This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 101210683 (for D.B). Authors acknowledge Ivar Järving and Kati Muldma for providing support in HPLC and elemental analysis respectively, Gemini PharmChem Mannheim GmbH / Synbias Pharma AG for providing doxorubicin hydrochloride used as the reference anticancer drug in this study, and Marlen Taggu (AS Tallinna Vesi) for providing wastewater treatment plant effluent for aerobic biodegradation tests.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Abbreviations

HepG2, human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line; Huh7, human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line; MCF7, human breast cancer cell line; MDA-MB-231, triple-negative breast cancer cell line; HeLa, cervical carcinoma cell line; M21, Melanoma cells; Kelly, SH-SY5Y, neuroblastoma cell lines; HEK293, non-malignant human embryonic kidney cell line; ADP, adenosine diphosphate; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; N-MYC, proto-oncogene protein; MYCN, the gene encoding the proto-oncogene protein N-MYC; ADMET, absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity; VEGFR2, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor; PARP1, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; CBT, closed bottle test; CDK, cyclin-dependent kinase; CHK1, checkpoint kinase 1; DMEM, Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium; DMF, dimethylformamide; DOX, doxorubicin; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; HPLC, high-performance liquid chromatography; IC50, half-maximal inhibitory concentration; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; WST-1, water-soluble tetrazolium salt-1; ADT, AutoDockTools program.

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.L.; Kratzer, T.B.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J Clin 2025, 75, 10–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Kumar, A.; Sharma, V.; Behl, T.; Sehgal, A.; Wal, P.; Shinde, N.V.; Kawaduji, B.S.; Kapoor, A.; Anwer, Md.K.; et al. Revolutionizing Pediatric Neuroblastoma Treatment: Unraveling New Molecular Targets for Precision Interventions. Front Cell Dev Biol 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maris, J.M.; Matthay, K.K. Molecular Biology of Neuroblastoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology 1999, 17, 2264–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedoya-Reina, O.C.; Li, W.; Arceo, M.; Plescher, M.; Bullova, P.; Pui, H.; Kaucka, M.; Kharchenko, P.; Martinsson, T.; Holmberg, J.; et al. Single-Nuclei Transcriptomes from Human Adrenal Gland Reveal Distinct Cellular Identities of Low and High-Risk Neuroblastoma Tumors. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 5309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Pacheco, M.L.; Hernández-Lemus, E.; Mejía, C. Analysis of High-Risk Neuroblastoma Transcriptome Reveals Gene Co-Expression Signatures and Functional Features. Biology (Basel) 2023, 12, 1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, X.X.; Zhao, H.; Kung, B.; Kim, D.Y.; Hicks, S.L.; Cohn, S.L.; Cheung, N.-K.; Seeger, R.C.; Evans, A.E.; Ikegaki, N. The MYCN Enigma: Significance of MYCN Expression in Neuroblastoma. Cancer Res 2006, 66, 2826–2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, M.J.; O’Grady, S.; Tang, M.; Crown, J. MYC as a Target for Cancer Treatment. Cancer Treat Rev 2021, 94, 102154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadimitropoulou, A.; Makri, M.; Zoidis, G. MYC the Oncogene from Hell: Novel Opportunities for Cancer Therapy. Eur J Med Chem 2024, 267, 116194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiyama, E.; Hiyama, K.; Yokoyama, T.; Ishii, T. Immunohistochemical Analysis of N-Myc Protein Expression in Neuroblastoma: Correlation with Prognosis of Patients. J Pediatr Surg 1991, 26, 838–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, M.W.; Burgess, S.G.; Poon, E.; Carstensen, A.; Eilers, M.; Chesler, L.; Bayliss, R. Structural Basis of N-Myc Binding by Aurora-A and Its Destabilization by Kinase Inhibitors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2016, 113, 13726–13731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjostrom, S.K.; Finn, G.; Hahn, W.C.; Rowitch, D.H.; Kenney, A.M. The Cdk1 Complex Plays a Prime Role in Regulating N-Myc Phosphorylation and Turnover in Neural Precursors. Dev Cell 2005, 9, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustafson, W.C.; Meyerowitz, J.G.; Nekritz, E.A.; Chen, J.; Benes, C.; Charron, E.; Simonds, E.F.; Seeger, R.; Matthay, K.K.; Hertz, N.T.; et al. Drugging MYCN through an Allosteric Transition in Aurora Kinase A. Cancer Cell 2014, 26, 414–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sells, T.B.; Chau, R.; Ecsedy, J.A.; Gershman, R.E.; Hoar, K.; Huck, J.; Janowick, D.A.; Kadambi, V.J.; LeRoy, P.J.; Stirling, M.; et al. MLN8054 and Alisertib (MLN8237): Discovery of Selective Oral Aurora A Inhibitors. ACS Med Chem Lett 2015, 6, 630–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Mehra, M.; Singh, R.; Kakar, S. Review on Chemistry of Oxazole Derivatives: Current to Future Therapeutic Prospective. Egypt J Basic Appl. Sci 2023, 10, 218–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiacchio, M.A.; Lanza, G.; Chiacchio, U.; Giofrè, S. V.; Romeo, R.; Iannazzo, D.; Legnani, L. Oxazole-Based Compounds As Anticancer Agents. Curr Med Chem 2020, 26, 7337–7371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakkar, S.; Narasimhan, B. A Comprehensive Review on Biological Activities of Oxazole Derivatives. BMC Chem 2019, 13, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Taguchi, E.; Miura, T.; Yamamoto, A.; Takahashi, K.; Bichat, F.; Guilbaud, N.; Hasegawa, K.; Kubo, K.; Fujiwara, Y.; et al. KRN951, a Highly Potent Inhibitor of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor Tyrosine Kinases, Has Antitumor Activities and Affects Functional Vascular Properties. Cancer Res 2006, 66, 9134–9142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulooze, S.C.; Cohen, A.F.; Rissmann, R. Olaparib. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2016, 81, 171–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deininger, M.; Buchdunger, E.; Druker, B.J. The Development of Imatinib as a Therapeutic Agent for Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. Blood 2005, 105, 2640–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klempner, S.; Tran, P. Profile of Rociletinib and Its Potential in the Treatment of Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Lung Cancer: Targets and Therapy 2016, 7, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenyuta, I.; Kovalishyn, V.; Tanchuk, V.; Pilyo, S.; Zyabrev, V.; Blagodatnyy, V.; Trokhimenko, O.; Brovarets, V.; Metelytsia, L. 1,3-Oxazole Derivatives as Potential Anticancer Agents: Computer Modeling and Experimental Study. Comput Biol Chem 2016, 65, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ADMETlab 3.0: Online ADMET Prediction Tool 2025.

- Fu, L.; Shi, S.; Yi, J.; Wang, N.; He, Y.; Wu, Z.; Peng, J.; Deng, Y.; Wang, W.; Wu, C.; et al. ADMETlab 3.0: An Updated Comprehensive Online ADMET Prediction Platform Enhanced with Broader Coverage, Improved Performance, API Functionality and Decision Support. Nucleic Acids Res 2024, 52, W422–W431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, D.E. V.; Blundell, T.L.; Ascher, D.B. PkCSM: Predicting Small-Molecule Pharmacokinetic and Toxicity Properties Using Graph-Based Signatures. J Med Chem 2015, 58, 4066–4072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assessment of Chemicals | OECD. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/topics/assessment-of-chemicals.html (accessed on 5 July 2024).

- Friedrich, J.; Längin, A.; Kü Mmerer, K. Comparison of an Electrochemical and Luminescence-Based Oxygen Measuring System for Use in the Biodegradability Testing According to Closed Bottle Test (OECD 301D). [CrossRef]

- Nyholm, N. The European System of Standardized Legal Tests for Assessing the Biodegradability of Chemicals. Environ Toxicol Chem 1991, 10, 1237–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Alam, Md.M.; Alam, S.; Ansari, A.; Mishra, S.; Husain, S.Q. Production of Ethanol from Jaggery. Int J Res Appl Sci Eng Technol 2022, 10, 5042–5045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachaeva, M. V.; Pilyo, S.G.; Zhirnov, V. V.; Brovarets, V.S. Synthesis, Characterization, and in Vitro Anticancer Evaluation of 2-Substituted 5-Arylsulfonyl-1,3-Oxazole-4-Carbonitriles. Med. Chem. Res. 2019, 28, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhlmann, N.; Vidaurre, R.; Kümmerer, K. Designing Greener Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients: Insights from Pharmaceutical Industry into Drug Discovery and Development. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci 2024, 192, 106614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapitanov, I. V.; Špulák, M.; Pour, M.; Soukup, O.; Marek, J.; Jun, D.; Novak, M.; Diz de Almeida, J.S.F.; França, T.C.C.; Gathergood, N.; et al. Sustainable Ionic Liquids-Based Molecular Platforms for Designing Acetylcholinesterase Reactivators. Chem Biol Interact 2023, 385, 110735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, H.M. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res 2000, 28, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Chen, J.; Cheng, T.; Gindulyte, A.; He, J.; He, S.; Li, Q.; Shoemaker, B.A.; Thiessen, P.A.; Yu, B.; et al. PubChem 2025 Update. Nucleic Acids Res 2025, 53, D1516–D1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diebold, M.; Schönemann, L.; Eilers, M.; Sotriffer, C.; Schindelin, H. Crystal Structure of a Covalently Linked Aurora-A–MYCN Complex. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol 2023, 79, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, P.K.; Yang, E.J.; Shi, C.; Ren, G.; Tao, S.; Shim, J.S. Aurora Kinase A, a Synthetic Lethal Target for Precision Cancer Medicine. Exp Mol Med 2021, 53, 835–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, K.W.L.; Chen, H.-W.T.; Hedley, D.W.; Chow, S.; Brandwein, J.; Schuh, A.C.; Schimmer, A.D.; Gupta, V.; Sanfelice, D.; Johnson, T.; et al. A Phase I Trial of the Aurora Kinase Inhibitor, ENMD-2076, in Patients with Relapsed or Refractory Acute Myeloid Leukemia or Chronic Myelomonocytic Leukemia. Invest New Drugs 2016, 34, 614–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.-F.; Chen, J.; Huang, D.; Ding, Y.; Tan, M.-H.; Qian, C.-N.; Resau, J.H.; Kim, H.; Teh, B.T. VX680/MK-0457, a Potent and Selective Aurora Kinase Inhibitor, Targets Both Tumor and Endothelial Cells in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Am J Transl Res 2010, 2, 296–308. [Google Scholar]

- Vats, P.; Saini, C.; Baweja, B.; Srivastava, S.K.; Kumar, A.; Kushwah, A.S.; Nema, R. Aurora Kinases Signaling in Cancer: From Molecular Perception to Targeted Therapies. Mol Cancer 2025, 24, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rihani, A.; Vandesompele, J.; Speleman, F.; Van Maerken, T. Inhibition of CDK4/6 as a Novel Therapeutic Option for Neuroblastoma. Cancer Cell Int 2015, 15, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chipumuro, E.; Marco, E.; Christensen, C.L.; Kwiatkowski, N.; Zhang, T.; Hatheway, C.M.; Abraham, B.J.; Sharma, B.; Yeung, C.; Altabef, A.; et al. CDK7 Inhibition Suppresses Super-Enhancer-Linked Oncogenic Transcription in MYCN-Driven Cancer. Cell 2014, 159, 1126–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavendra, N.M.; Pingili, D.; Kadasi, S.; Mettu, A.; Prasad, S.V.U.M. Dual or Multi-Targeting Inhibitors: The next Generation Anticancer Agents. Eur J Med Chem 2018, 143, 1277–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doostmohammadi, A.; Jooya, H.; Ghorbanian, K.; Gohari, S.; Dadashpour, M. Potentials and Future Perspectives of Multi-Target Drugs in Cancer Treatment: The next Generation Anti-Cancer Agents. Cell Commun. Signal. 2024, 22, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Inhibitors of Aurora A kinase.

Figure 1.

Inhibitors of Aurora A kinase.

Figure 2.

Key Features and Applications of Oxazoles.

Figure 2.

Key Features and Applications of Oxazoles.

Figure 3.

Clinical use of 1,3-oxazole-based drugs [

15].

Figure 3.

Clinical use of 1,3-oxazole-based drugs [

15].

Scheme 1.

General Procedure for the Synthesis of 5-(piperazin-1-yl)oxazole-4-carbonitrile hydrochlorides 2a-2c and 5-(sulfonylpiperazin 1-yl)oxazole-4-carbonitriles 3aa-3ce.

Scheme 1.

General Procedure for the Synthesis of 5-(piperazin-1-yl)oxazole-4-carbonitrile hydrochlorides 2a-2c and 5-(sulfonylpiperazin 1-yl)oxazole-4-carbonitriles 3aa-3ce.

Figure 4.

Structure of compounds 2a – 2c and 3aa – 3ce.

Figure 4.

Structure of compounds 2a – 2c and 3aa – 3ce.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of 2-aryl-5-(4-phenylpiperazin-1-yl)sulfonyl-1,3-oxazole-4-carbonitriles 5a, 5b.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of 2-aryl-5-(4-phenylpiperazin-1-yl)sulfonyl-1,3-oxazole-4-carbonitriles 5a, 5b.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of 5-[4-(arylsulfonyl)piperazin-1-yl]sulfonyl-2-(4-aryl)-1,3-oxazole-4-carbonitriles 8aa–8bd.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of 5-[4-(arylsulfonyl)piperazin-1-yl]sulfonyl-2-(4-aryl)-1,3-oxazole-4-carbonitriles 8aa–8bd.

Figure 5.

Structure o compound 7a – 7b and 8aa – 8bd.

Figure 5.

Structure o compound 7a – 7b and 8aa – 8bd.

Figure 6.

Cytotoxic effects of all studied compounds at 2.5 µM after 48 h incubation assessed by WST-1 assay. Cell viability data on HEK293 cells (A) and Kelly cells (B) with Doxorubicin as negative control. In both panels, data of the cells treated with solvent are used as control (100% viability, n ≥ 3); mean ± SD.

Figure 6.

Cytotoxic effects of all studied compounds at 2.5 µM after 48 h incubation assessed by WST-1 assay. Cell viability data on HEK293 cells (A) and Kelly cells (B) with Doxorubicin as negative control. In both panels, data of the cells treated with solvent are used as control (100% viability, n ≥ 3); mean ± SD.

Figure 7.

IC50 graphs for 7a, 7b, 8aa in HEK cells (A–C) Kelly cells (D–F) and SHSY5Y cells (G-I) after 48 h incubation assessed by WST-1 assay; mean (n ≥ 3) ± SD.

Figure 7.

IC50 graphs for 7a, 7b, 8aa in HEK cells (A–C) Kelly cells (D–F) and SHSY5Y cells (G-I) after 48 h incubation assessed by WST-1 assay; mean (n ≥ 3) ± SD.

Figure 8.

IC50 graphs for doxorubicin in HEK293 cells (A) and Kelly cells (B) after 48 h incubation assessed by WST-1 assay; mean (n ≥ 3) ± SD.

Figure 8.

IC50 graphs for doxorubicin in HEK293 cells (A) and Kelly cells (B) after 48 h incubation assessed by WST-1 assay; mean (n ≥ 3) ± SD.

Figure 9.

IC50 graphs for 7b in various cancer cell lines after 48 h incubation assessed by WST-1 assayБ; mean (n ≥ 3) ± SD.

Figure 9.

IC50 graphs for 7b in various cancer cell lines after 48 h incubation assessed by WST-1 assayБ; mean (n ≥ 3) ± SD.

Figure 10.

A demonstration of molecular docking results of ligand 7b with neuroblastoma-associated proteins; blue-compound-7b; green - co-crystallized ligands.

Figure 10.

A demonstration of molecular docking results of ligand 7b with neuroblastoma-associated proteins; blue-compound-7b; green - co-crystallized ligands.

Figure 11.

The molecular docking features of compounds 7a, 7b, and 8aa with the ATP-binding site of Aurora A kinase; (a, b) – compound 7a; (c, d) – compound 7b; (e, f) – compound 8aa; green - hydrogen bonds; orange - electrostatic interactions; violet - hydrophobic interactions.

Figure 11.

The molecular docking features of compounds 7a, 7b, and 8aa with the ATP-binding site of Aurora A kinase; (a, b) – compound 7a; (c, d) – compound 7b; (e, f) – compound 8aa; green - hydrogen bonds; orange - electrostatic interactions; violet - hydrophobic interactions.

Figure 12.

The docking position of the studied сompounds in the ATP-binding site of Aurora-A kinase compared with ADP (PDB ID: 5G1X); red – ADP; blue – compound 7a; green – compound 7b; violet – compound 8aa.

Figure 12.

The docking position of the studied сompounds in the ATP-binding site of Aurora-A kinase compared with ADP (PDB ID: 5G1X); red – ADP; blue – compound 7a; green – compound 7b; violet – compound 8aa.

Figure 13.

ADMET properties of compounds 7a, 7b, 8aa and doxorubicin (by ADMETlab 3.0).

Figure 13.

ADMET properties of compounds 7a, 7b, 8aa and doxorubicin (by ADMETlab 3.0).

Table 1.

The molecular docking results of ligands 7a, 7a, and 8aa with cancer-related proteins, along with the redocking outcomes.

Table 1.

The molecular docking results of ligands 7a, 7a, and 8aa with cancer-related proteins, along with the redocking outcomes.

Compounds and

ligands |

Binding energy, ∆G, kcal/mol |

| ALK |

CDK2 |

CDK4 |

CDK6 |

CDK7 |

CDK9 |

CHK1 |

BCL2 |

Aurora A/

N-MYC |

PARP1 |

| 7a |

– 7.1 |

– 7.9 |

– 9.0 |

– 8.0 |

– 8.5 |

– 8.0 |

– 8.9 |

– 7.4 |

– 10.8 |

– 8.1 |

| 7b |

– 7.2 |

– 8.1 |

– 9.0 |

– 8.2 |

– 9.1 |

– 8.2 |

– 8.7 |

– 7.8 |

– 10.9 |

– 8.4 |

| 8aa |

– 7.5 |

– 8.0 |

– 9.1 |

– 8.1 |

– 9.0 |

– 8.7 |

– 9.1 |

– 8.0 |

– 10.8 |

– 8.3 |

| Crizotinib |

– 9.0 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

| CID 57519664a

|

– |

– 8.2 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

Abemaciclib

|

– |

– |

– 9.1 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

| CID 169552807b

|

– |

– |

– |

– 9.2 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

| ATPc

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– 9.3 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

| CID 124155204d

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– 9.0 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

| CID 6914568e

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– 9.4 |

– |

– |

– |

| Navitoclax |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– 11.5 |

– |

– |

| ADPf

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– 10.9 |

– |

| CID 49873226g

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– 8.8 |

Table 2.

ADMET characteristics of compounds 7a, 7b, and 8aa in comparison with doxorubicin.

Table 2.

ADMET characteristics of compounds 7a, 7b, and 8aa in comparison with doxorubicin.

| Parameter |

Compounds |

| 7a |

7b |

8aa |

Doxorubicin |

| Physicochemical properties |

|

|

|

|

| Molecular weight, g/mol |

318.35 |

332.40 |

410.48 |

543.525 |

| Rotatable bond count |

3 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| Hydrogen bond acceptor count |

7 |

7 |

9 |

12 |

| Hydrogen bond donor count |

1 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

| Surface area, A2 a

|

127.784 |

134.149 |

157.485 |

222.081 |

| logP |

1.424 |

2.013 |

2.048 |

1.208 |

| Water solubility, log mol/L |

-3.015 |

-2.879 |

-4.146 |

-2.915 |

| Absorption |

|

|

|

|

Caco-2 permeability,

log cm/s |

-5.855 |

-5.47 |

-4.851 |

-6.77 |

| Inhibitor of P-glycoprotein |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

| Substrate of P-glycoprotein |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

| Distribution |

|

|

|

|

| BBB permeability a

|

-0.822 |

-0.87 |

-1.474 |

-1.379 |

| CNS permeability a

|

-3.056 |

-2.621 |

-2.908 |

-2.846 |

| Metabolism |

|

|

|

|

| CYP2D6 substrate |

No |

No |

No |

No |

| CYP3A4 substrate |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

| CYP1A2 inhibitor |

No |

No |

No |

No |

| CYP2C19 substrate |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

| CYP2C19 inhibitor |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

| CYP2C9 inhibitor |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

| CYP2D6 inhibitor |

No |

No |

No |

No |

| CYP3A4 inhibitor |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

| Excretion |

|

|

|

|

| Plasma clearance, ml/min/kg |

6.379 |

6.382 |

5.762 |

14.244 |

| Half-life of the drug, hour |

0.821 |

0.686 |

0.793 |

3.774 |

| Toxicity |

|

|

|

|

| Rat Oral Acute Toxicity (LD50), mol/kg a

|

2.456 |

2.471 |

2.491 |

2.408 |

| Human Hepatotoxicity a

|

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Max. tolerated dose (human), log mg/kg/day a

|

-0.158 |

-0.554 |

-0.429 |

0.081 |

|

a predicted using pkCSM web server. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).