Submitted:

16 December 2025

Posted:

16 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

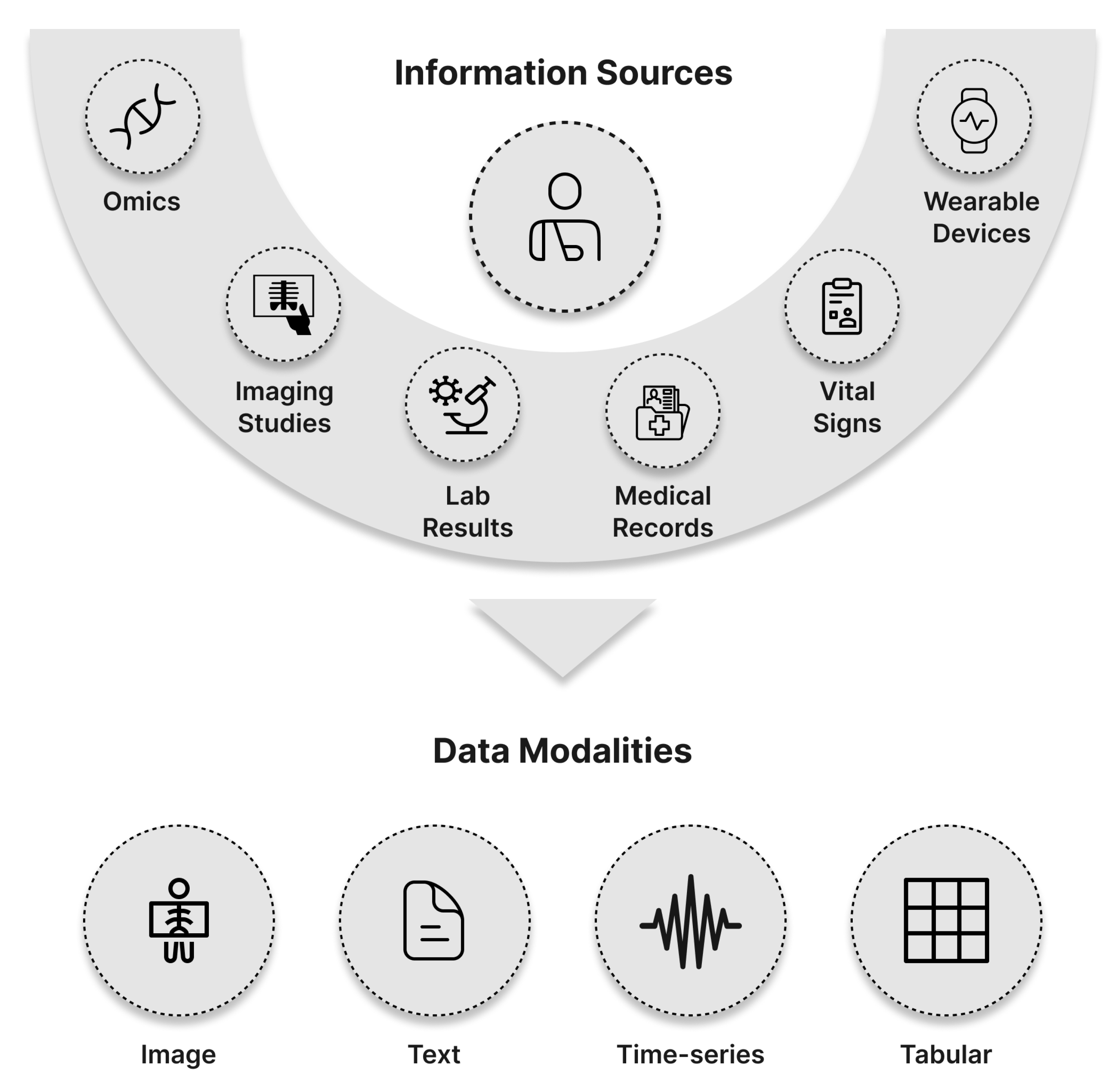

2. Fundamentals of Multimodal Machine Learning

- a)

- X-ray Imaging:

- b)

- Computed Tomography (CT):

- c)

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI):

- d)

- Ultrasound Imaging:

- e)

- Dermoscopic Imaging:

2.0.1. Text Data

2.0.2. Time Series Data

2.0.3. Tabular Data

2.1. Challenges in Multimodal Machine Learning

2.1.1. Heterogeneity of Modalities

2.1.2. Alignment

2.1.3. Fusion Strategies

2.2. Techniques for Multimodal Machine Learning

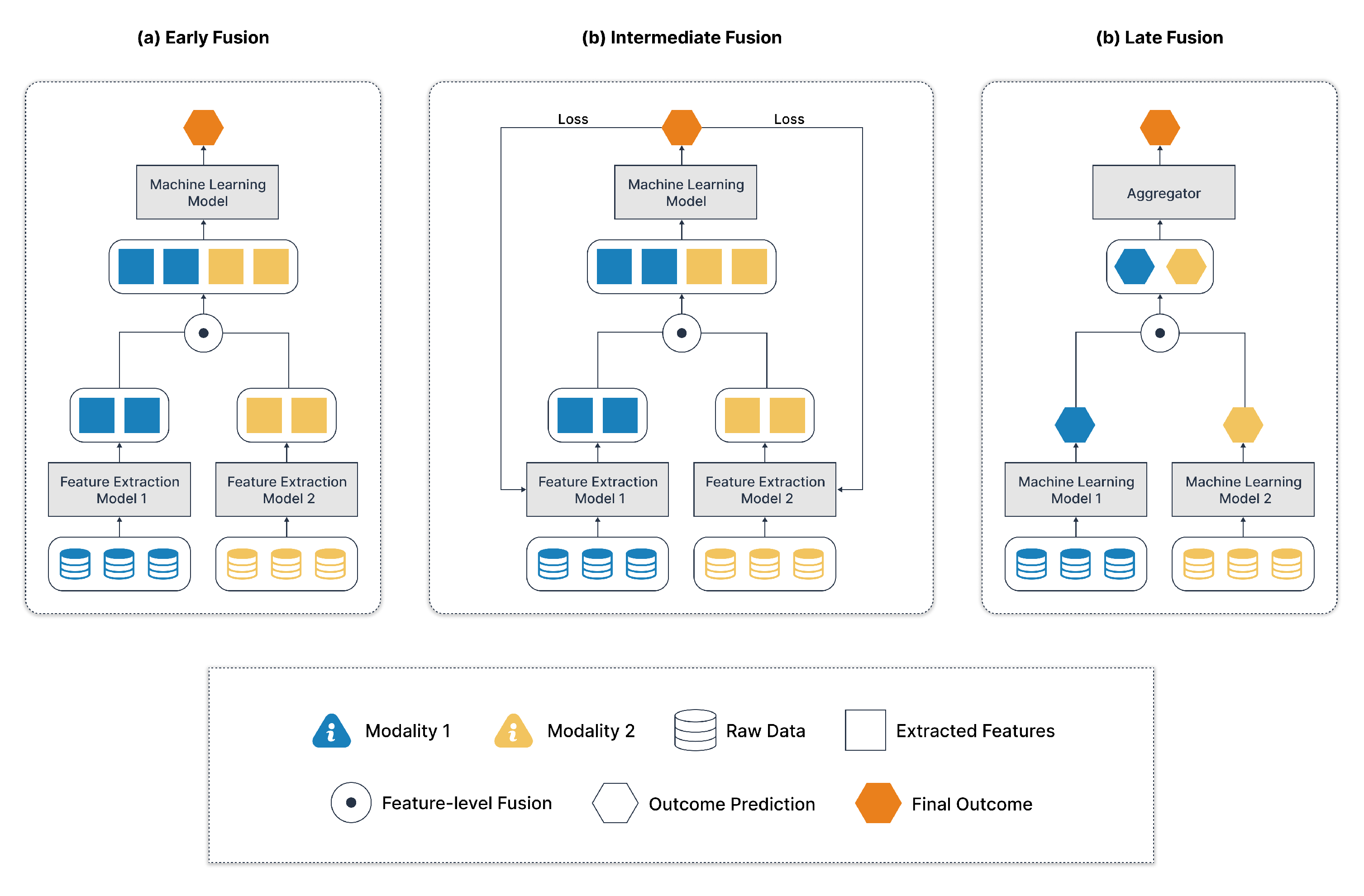

2.2.1. Modality Level Fusion

- a)

- Early Fusion:

- b)

- Intermediate Fusion or Joint Fusion:

- Visual data may be processed by convolutional neural networks (CNNs).

- Text data could be processed by recurrent neural networks (RNNs) or transformers.

- c)

- Late Fusion:

- d)

- Hybrid fusion or Mixed Fusion:

- Early Fusion can cause imbalance if one modality dominates at the raw feature level.

- Late Fusion might miss subtle inter-modality interactions.

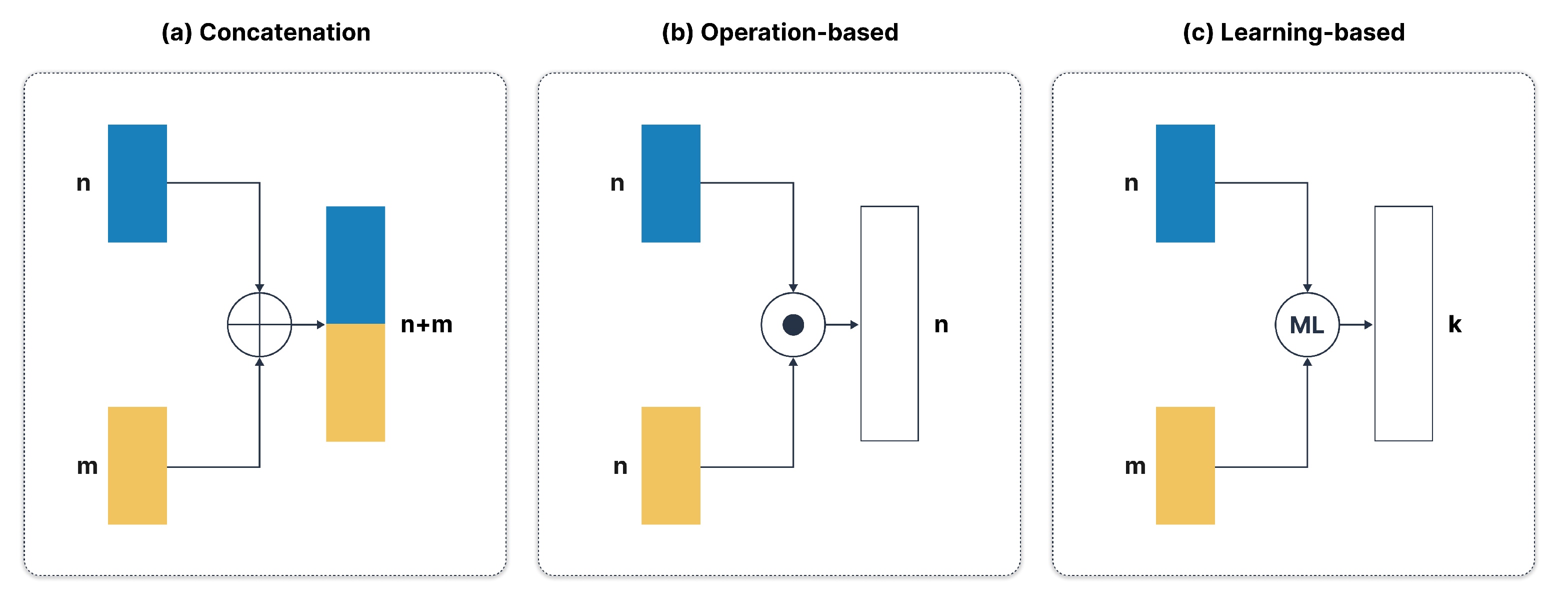

2.2.2. Feature Level Fusion

- a)

- Concatenation:

- b)

- Operation-Based Fusion:

- Addition:

- Multiplication:

- Averaging:

- c)

- Learning-Based Fusion:

3. Advanced Multimodal Machine Learning

3.1. Attention Mechanisms for Multimodal Integration

3.2. Cross-Modal Embeddings and Alignment

3.3. Generative Models for Multimodal Data Synthesis

3.4. Graph Neural Networks for Structured Multimodal Reasoning

4. Applications of Multimodal Machine Learning in Healthcare

4.1. Multimodality Approaches in Brain Disorder

4.2. Multimodality Approaches in Cancer Prediction

4.3. Multimodality Approaches in Chest Related Conditions

4.4. Multimodality Approaches in Skin Related Conditions and Other Diseases

5. Discussion and Future Directions

5.1. Advantages of Multimodality in Healthcare

5.2. Challenges in Attention-Based and Transformer Models

- Interpretability and Reliability: Attention scores do not necessarily reflect true causal importance, and high-dimensional attention maps can be difficult to validate clinically. More robust interpretability strategies are needed for transparency.

- Data Scale and Quality: Transformers typically require large-scale, high-quality datasets. In health care, data are often siloed, limited in size, noisy, or otherwise difficult to scale in training. A few methods, such as self-supervised learning, efficient pretraining, and model distillation, can help mitigate these data bottlenecks.

- Modality Balancing: Differences in information density among modalities—for instance, rich imaging data versus sparse text notes—can skew attention and degrade downstream performance. Balancing the relative contributions of each modality remains a key research question.

5.3. Graph Neural Networks for Structured Reasoning

- Graph Construction and Heterogeneity: It is non-trivial to decide how to encode diverse data, be it images, clinical metrics, or genomic markers, as nodes or edges in a graph. Automating the process of graph construction that adapts to the diversity of clinical scenarios remains an active research area.

- Scalability and Dynamic Graphs: Large patient cohorts and real-time streams of data call for scalable GNNs, which can efficiently handle dynamic updates, new modalities, or newly acquired data for patients.

- Uncertainty and Noise: Real-world clinical data are usually incomplete or noisy. There is a strong need for effective uncertainty modeling and robust training strategies of GNNs to make reliable predictions.

5.4. Generative Models in Healthcare

- Data Augmentation for Rare Conditions: Generative models can synthesize realistic examples of rare diseases, which may help to mitigate class imbalance and improve the training of discriminative models.

- Clinical Validity: It is important that the generated samples retain medically valid features. Small deviations in synthetic medical images can have a huge impact on diagnosis or treatment planning downstream.

- Ethical and Regulatory Concerns: Synthetic data has to ensure the privacy of patients and meet regulatory standards. Methods of privacy-preserving generation—for example, through differential privacy—and transparent validation are vital for clinical adoption.

5.5. Multimodal Learning in Specialized Healthcare Domains

- a)

- Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders:

- Longitudinal Consistency: How to capture progressive and temporal features of neurodegenerative diseases using recurrent networks or temporal transformers.

- Standardized and Open Data Repositories: Good quality longitudinal datasets are still very limited. The creation of larger, more heterogeneous, and carefully annotated databases is thus important for model development and benchmarking.

- b)

- Oncology and Cancer Prediction:

- Explainable AI for Oncology: Clinicians require transparent explanations of model predictions when managing critical decisions like chemotherapy regimens or immunotherapies.

- Integration of Liquid Biopsy and Proteomic Data: Beyond imaging and genomics, molecular profiles (e.g., circulating tumor DNA) and proteomic features may further refine and personalize treatment strategies.

- c)

- Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Applications:

- Streaming Data Integration: Continuous patient monitoring devices produce dynamic, high-frequency data. Incorporating these signals into multimodal networks can facilitate early warning systems and preventive care.

- Generalization to Low-Resource Settings: Automated methods that perform reliably even where medical data is sparse or of lower quality (e.g., remote regions) can help address global healthcare disparities.

5.6. Interpretability, Fairness, and Ethical Considerations

- Human-Centered Interpretability: Clinicians and patients need to understand the rationale behind a model’s prediction, especially for high-stakes decisions. Techniques such as attention visualization, saliency maps, concept-based explanations, and post-hoc analysis can increase trust.

- Bias and Fairness: Disparities in dataset demographics can result in biased models that underperform in certain subpopulations. Addressing these issues may involve collecting more diverse datasets, performing bias audits, or adopting fairness-aware training objectives.

- Robustness and Safety: Medical data can contain noise, artifacts, or adversarial corruption (e.g., sensor errors, malicious attacks). Ensuring robustness against such distortions is critical, particularly for real-world deployment in critical care environments.

5.7. Path Forward

- Unified Foundation Models in Healthcare: Inspired by CLIP, ALIGN, and large language models, future research may seek to develop foundation models that can handle imaging, textual EHRs, laboratory data, and genetic information in a single framework. These models, trained on large and diverse datasets, can be adapted to a wide range of downstream healthcare tasks with minimal supervision.

- Causality and Counterfactual Reasoning: Current MML approaches excel at correlational reasoning but often fail to capture causal relationships. Developing causal representation learning methods that can disentangle confounders and more accurately predict intervention outcomes remains a priority.

- Multimodal Reinforcement Learning (RL): Interactive clinical tasks—such as robotic surgeries or therapy optimizations—may benefit from combining RL with multimodal understanding. Systems could learn to perform safe interventions by balancing real-time imaging, vital signs, and textual feedback from clinicians.

- Privacy-Preserving and Federated Learning: As patient data typically reside in multiple institutions with strict privacy regulations, federated and privacy-preserving ML approaches are essential for building large-scale multimodal models without sharing sensitive patient information.

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Miotto, R.; Wang, F.; Wang, S.; Jiang, X.; Dudley, J.T. Deep learning for healthcare: review, opportunities and challenges. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2018, 19, 1236–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteva, A.; et al. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature 2017, 542, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlSaad, R.; Abd-alrazaq, A.A.; Boughorbel, S.; Ahmed, A.; Renault, M.A.; Damseh, R.R.; Sheikh, J. Multimodal large language models in health care: Applications, challenges, and future outlook. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2024, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreu-Perez, J.; Poon, C.C.Y.; Merrifield, R.D.; Wong, S.T.C.; Yang, G.Z. Big Data for Health. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2015, 19, 1193–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Gomez, M.R.C. A Comprehensive Introduction to Healthcare Data Analytics. Journal of Biomedical and Sustainable Healthcare Applications 2024, n. pag. [Google Scholar]

- Seneviratne, M.G.; Kahn, M.G.; Hernandez-Boussard, T. Merging heterogeneous clinical data to enable knowledge discovery. Pac Symp Biocomput 2019, 24, 439–443. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R.J.; Lu, M.Y.; Wang, J.; Williamson, D.F.; Rodig, S.J.; Lindeman, N.I.; Mahmood, F. Pathomic fusion: an integrated framework for fusing histopathology and genomic features for cancer diagnosis and prognosis. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2020, 41, 757–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warner, E.; Lee, J.; Hsu, W.; et al. Multimodal Machine Learning in Image-Based and Clinical Biomedicine: Survey and Prospects. International Journal of Computer Vision 2024, 132, 3753–3769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertsimas, D.; Ma, Y. M3H: Multimodal Multitask Machine Learning for Healthcare. arXiv 2024. arXiv:2404.18975. [CrossRef]

- Krones, F.; Marikkar, U.; Parsons, G.; Szmul, A.; Mahdi, A. Review of multimodal machine learning approaches in healthcare. Information Fusion 2025, 114, 102690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- England, N.H.S.; Improvement, N.H.S. Diagnostic imaging dataset statistical release. Department of Health 2016, 421. [Google Scholar]

- Dendy, P.P.; Heaton, B. Physics for diagnostic radiology; CRC Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Brant, W.E.; Helms, C.A. (Eds.) Fundamentals of diagnostic radiology; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins (LWW), 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Simonyan, K. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar]

- Duvieusart, B.; Krones, F.; Parsons, G.; Tarassenko, L.; Papież, B.W.; Mahdi, A. Multimodal cardiomegaly classification with image-derived digital biomarkers. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference on Medical Image Understanding and Analysis; Springer International Publishing, 2022; pp. 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.X. Machine learning in X-ray imaging and microscopy applications. Advanced X-ray Imaging of Electrochemical Energy Materials and Devices 2021, 205–221. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, L.W. Principles of CT and CT technology. Journal of Nuclear Medicine Technology 2007, 35, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, A.; Dixon, A.K.; Gillard, J.H.; Schaefer-Prokop, C. Grainger & Allison’s Diagnostic Radiology, 2 Volume Set E-Book; Elsevier Health Sciences, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bremner, D. Brain imaging handbook; WW Norton & Co, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Schoepf, J.; Zwerner, P.; Savino, G.; Herzog, C.; Kerl, J.M.; Costello, P. Coronary CT angiography. Radiology 2007, 244, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, H.; de Roos, A.; Geleijins, J.; Huisman, M.V.; Kroft, L.J.M. The role of computed tomography in the diagnosis of acute and chronic pulmonary embolism. Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology 2015, 21, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.; Ouyang, L.; Gao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yu, T.; Li, Q.; Sun, K.; Bao, F.S.; Safarnejad, L.; Wen, J.; et al. Accurately differentiating COVID-19, other viral infection, and healthy individuals using multimodal features via late fusion learning. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Bai, S.; Chen, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Xia, L.; Qin, L.; Gong, S.; Xie, X.; Zhou, C.; Tu, D.; et al. Deep learning for predicting COVID-19 malignant progression. Medical Image Analysis 2021, 72, 102096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samak, Z.A.; Clatworthy, P.; Mirmehdi, M. Prediction of thrombectomy functional outcomes using multimodal data. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference on Medical Image Understanding and Analysis; Springer, 2020; pp. 267–279. [Google Scholar]

- Brunelli, A.; Charloux, A.; Bolliger, C.T.; Rocco, G.; Sculier, J.P.; Varela, G.; Licker, M.J.; Ferguson, M.K.; Faivre-Finn, C.; Huber, R.M.; et al. ERS/ESTS clinical guidelines on fitness for radical therapy in lung cancer patients (surgery and chemo-radiotherapy). European Respiratory Journal 2009, 34, 17–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiener, R.S.; Schwartz, L.M.; Woloshin, S. When a test is too good: how CT pulmonary angiograms find pulmonary emboli that do not need to be found. BMJ 2013, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battista, J.J.; Rider, W.D.; Van Dyk, J. Computed tomography for radiotherapy planning. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics 1980, 6, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grover, V.P.B.; Tognarelli, J.M.; Crossey, M.M.E.; Cox, I.J.; Taylor-Robinson, S.D.; McPhail, M.J.W. Magnetic resonance imaging: principles and techniques: lessons for clinicians. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hepatology 2015, 5, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisoni, G.B.; Fox, N.C.; Jack, C.R.; Scheltens, P.; Thompson, P.M. The clinical use of structural MRI in Alzheimer disease. Nature Reviews Neurology 2010, 6, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guermazi, A.; Roemer, F.W.; Haugen, I.K.; Crema, M.D.; Hayashi, D. MRI-based semiquantitative scoring of joint pathology in osteoarthritis. Nature Reviews Rheumatology 2013, 9, 236–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisot, S.; Ktena, S.I.; Ferrante, E.; Lee, M.; Guerrero, R.; Glocker, B.; Rueckert, D. Disease prediction using graph convolutional networks: application to autism spectrum disorder and Alzheimer’s disease. Medical Image Analysis 2018, 48, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pölsterl, S.; Wolf, T.N.; Wachinger, C. Combining 3D image and tabular data via the dynamic affine feature map transform. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention; Springer, 2021; pp. 688–698. [Google Scholar]

- Ryman, S.G.; Poston, K.L. MRI biomarkers of motor and non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders 2020, 73, 85–93. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, Y.; Tang, L.Y.W.; Li, D.K.B.; Metz, L.; Kolind, S.; Traboulsee, A.L.; Tam, R.C. Deep learning of brain lesion patterns and user-defined clinical and MRI features for predicting conversion to multiple sclerosis from clinically isolated syndrome. Computer Methods in Biomechanics and Biomedical Engineering: Imaging & Visualization 2019, 7, 250–259. [Google Scholar]

- Stadler, A.; Schima, W.; Ba-Ssalamah, A.; Kettenbach, J.; Eisenhuber, E. Artifacts in body MR imaging: their appearance and how to eliminate them. European Radiology 2007, 17, 1242–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Sheikholeslami, G.; Zhang, A. FindOut: Finding outliers in very large datasets. Knowledge and Information Systems 2002, 4, 387–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carovac, A.; Smajlovic, F.; Junuzovic, D. Application of ultrasound in medicine. Acta Informatica Medica 2011, 19, 168–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merz, E.; Abramowicz, J.S. 3D/4D ultrasound in prenatal diagnosis: is it time for routine use? Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology 2012, 55, 336–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brattain, L.J.; Telfer, B.A.; Dhyani, M.; Grajo, J.R.; Samir, A.E. Machine learning for medical ultrasound: status, methods, and future opportunities. Abdominal Radiology 2018, 43, 786–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaoğlu, O.; Bilge, H.Ş.; Uluer, I. Removal of speckle noises from ultrasound images using five different deep learning networks. Engineering Science and Technology, an International Journal 2022, 29, 101030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vestergaard, M.E.; Macaskill, P.H.P.M.; Holt, P.E.; Menzies, S.W. Dermoscopy compared with naked eye examination for the diagnosis of primary melanoma: a meta-analysis of studies performed in a clinical setting. British Journal of Dermatology 2008, 159, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, R.P.; Rabinovitz, H.S.; Oliviero, M.; Kopf, A.W.; Saurat, J.H. Dermoscopy of pigmented skin lesions. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 2005, 52, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, M.A.; Mia, M.S.; Sayed, M.A.; Uddin, M.R. Predicting the outcome of English Premier League matches using machine learning. In Proceedings of the 2020 2nd International Conference on Sustainable Technologies for Industry 4.0 (STI); IEEE, 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kawahara, J.; Daneshvar, S.; Argenziano, G.; Hamarneh, G. Seven-point checklist and skin lesion classification using multitask multimodal neural nets. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2018, 23, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, I.; Younus, M.; Walayat, K.; Kakar, M.U.; Ma, J. Automated multi-class classification of skin lesions through deep convolutional neural network with dermoscopic images. Computerized Medical Imaging and Graphics 2021, 88, 101843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, J.; Yolland, W.; Tschandl, P. Multimodal skin lesion classification using deep learning. Experimental Dermatology 2018, 27, 1261–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gessert, N.; Nielsen, M.; Shaikh, M.; Werner, R.; Schlaefer, A. Skin lesion classification using ensembles of multi-resolution EfficientNets with meta data. MethodsX 2020, 7, 100864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittler, H.; Pehamberger, H.; Wolff, K.; Binder, M.J.T.I.O. Diagnostic accuracy of dermoscopy. The Lancet Oncology 2002, 3, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spasic, I.; Nenadic, G.; et al. Clinical text data in machine learning: systematic review. JMIR Medical Informatics 2020, 8, e17984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustafa, A.; Azghadi, M.R. Automated machine learning for healthcare and clinical notes analysis. Computers 2021, 10, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Spooner, S.A.; Kaiser, M.; Lingren, N.; Robbins, J.; Lingren, T.; Solti, I.; Ni, Y. An end-to-end hybrid algorithm for automated medication discrepancy detection. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 2015, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.; Pollard, T.; Horng, S.; Celi, L.A.; Mark, R. MIMIC-IV-Note: Deidentified free-text clinical notes. PhysioNet 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.C.; Shen, L.; Lungren, M.P.; Yeung, S. GLoRIA: A multimodal global-local representation learning framework for label-efficient medical image recognition. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2021; pp. 3942–3951. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, A.; Davidson, E.; Poon, M.; Dong, H.; Duma, D.; Grivas, A.; Grover, C.; Suárez-Paniagua, V.; Tobin, R.; Whiteley, W.; et al. A systematic review of natural language processing applied to radiology reports. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 2021, 21, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, M.; Hussain, J.; Abbas, A.; Maqbool, H. Multi-class clinical text annotation and classification using BERT-based active learning. Available at SSRN 2022, 4081033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Niu, J.; Liu, X.; Chen, Z.; Tang, S.; Yu, S. A survey on incorporating domain knowledge into deep learning for medical image analysis. Medical Image Analysis 2021, 101985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikhalishahi, S.; Miotto, R.; Dudley, J.T.; Lavelli, A.; Rinaldi, F.; Osmani, V.; et al. Natural language processing of clinical notes on chronic diseases: systematic review. JMIR Medical Informatics 2019, 7, e12239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, S.; Bashall, A.; Al-Adely, S.; Moore, J.; Wilson, A.; Kitchen, G.B. Natural language processing in medicine: a review. Trends in Anaesthesia and Critical Care 2021, 38, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lasko, T.A.; Mei, Q.; Denny, J.C.; Xu, H. A study of active learning methods for named entity recognition in clinical text. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 2015, 58, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walonoski, J.; Kramer, M.; Nichols, J.; Quina, A.; Moesel, C.; Hall, D.; Duffett, C.; Dube, K.; Gallagher, T.; McLachlan, S. Synthea: An approach, method, and software mechanism for generating synthetic patients and the synthetic electronic health care record. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2018, 25, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeger, S.L.; Irizarry, R.A.; Peng, R.D. On time series analysis of public health and biomedical data. Annual Review of Public Health 2006, 27, 57–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrett, D.; Yoon, J.; Bica, I.; Qian, Z.; Ercole, A.; van der Schaar, M. Clairvoyance: A pipeline toolkit for medical time series. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.18688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, Z.; Purushotham, S.; Cho, K.; Sontag, D.; Liu, Y. Recurrent neural networks for multi-variate time series with missing values. Scientific Reports 2018, 8, 6085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Wu, L.; Hauskrecht, M. Modeling clinical time series using Gaussian process sequences. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2013 SIAM International Conference on Data Mining. Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, 2013; pp. 623–631. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, B.; Krones, F.; Kiskin, I.; Parsons, G.; Lyons, T.; Mahdi, A. Dual Bayesian ResNet: A deep learning approach to heart murmur detection. Computing in Cardiology 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.H. Comparing models for time series analysis. Wharton Research Scholars 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.S.; Tong, L.I. Forecasting time series using a methodology based on autoregressive integrated moving average and genetic programming. Knowledge-Based Systems 2011, 24, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumugam, V.; Natarajan, V. Time Series Modeling and Forecasting Using Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average and Seasonal Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average Models. Instrumentation, Mesures, Métrologies 2023, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, S.; Choudhury, A.; Sheron, P.K.; Dasgupta, N.; Natarajan, S.; Pickett, L.A.; Dutt, V. AI in healthcare: time-series forecasting using statistical, neural, and ensemble architectures. Frontiers in Big Data 2020, 3, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.L.; Amorim, E.; Jing, J.; Ge, W.; Hong, S.; Wu, O.; Ghassemi, M.; Lee, J.W.; Sivaraju, A.; Pang, T.; et al. Predicting neurological outcome in comatose patients after cardiac arrest with multiscale deep neural networks. Resuscitation 2021, 169, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morid, M.A.; Sheng, O.R.L.; Dunbar, J. Time series prediction using deep learning methods in healthcare. ACM Transactions on Management Information Systems 2023, 14, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccarelli, F.; Mahmoud, M. Multimodal temporal machine learning for bipolar disorder and depression recognition. Pattern Analysis and Applications 2022, 25, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salekin, M.S.; Zamzmi, G.; Goldgof, D.; Kasturi, R.; Ho, T.; Sun, Y. Multimodal spatio-temporal deep learning approach for neonatal postoperative pain assessment. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2021, 129, 104150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Masud, M.; Hayawi, K.; Samuel Mathew, S.; Dirir, A.; Cheratta, M. Effective patient similarity computation for clinical decision support using time series and static data. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Australasian Computer Science Week Multiconference, 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Di Martino, F.; Delmastro, F. Explainable AI for clinical and remote health applications: a survey on tabular and time series data. Artificial Intelligence Review 2023, 56, 5261–5315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaus, W.A.; Draper, E.A.; Wagner, D.P.; Zimmerman, J.E. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Critical care medicine 1985, 13, 818–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierson, E.; Cutler, D.M.; Leskovec, J.; Mullainathan, S.; Obermeyer, Z. An algorithmic approach to reducing unexplained pain disparities in underserved populations. Nature Medicine 2021, 27, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herdman, M.; Gudex, C.; Lloyd, A.; Janssen, M.; Kind, P.; Parkin, D.; Bonsel, G.; Badia, X. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Quality of life research 2011, 20, 1727–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pölsterl, S.; Wolf, T.N.; Wachinger, C. Combining 3D image and tabular data via the dynamic affine feature map transform. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2021: 24th International Conference, Strasbourg, France, September 27–October 1, 2021, Proceedings, Part V 24; Springer, 2021; pp. 688–698. [Google Scholar]

- Krones, F.H.; Walker, B.; Parsons, G.; Lyons, T.; Mahdi, A. Multimodal deep learning approach to predicting neurological recovery from coma after cardiac arrest. arXiv 2024. arXiv:2403.06027. [CrossRef]

- Ayesha, S.; Hanif, M.K.; Talib, R. Performance enhancement of predictive analytics for health informatics using dimensionality reduction techniques and fusion frameworks. IEEE Access 2021, 10, 753–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arik, S.Ö.; Pfister, T. Tabnet: Attentive interpretable tabular learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence; 2021; Vol. 35, pp. 6679–6687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reda, I.; Khalil, A.; Elmogy, M.; Abou El-Fetouh, A.; Shalaby, A.; Abou El-Ghar, M.; Elmaghraby, A.; Ghazal, M.; El-Baz, A. Deep learning role in early diagnosis of prostate cancer. Technology in cancer research & treatment 2018, 17, 1533034618775530. [Google Scholar]

- Vanguri, R.S.; Luo, J.; Aukerman, A.T.; Egger, J.V.; Fong, C.J.; Horvat, N.; Pagano, A.; Araujo-Filho, J.d.A.B.; Geneslaw, L.; Rizvi, H.; et al. Multimodal integration of radiology, pathology and genomics for prediction of response to PD-(L) 1 blockade in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Nature cancer 2022, 3, 1151–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.E.; Pollard, T.J.; Shen, L.; Lehman, L.w.H.; Feng, M.; Ghassemi, M.; Moody, B.; Szolovits, P.; Anthony Celi, L.; Mark, R.G. MIMIC-III, a freely accessible critical care database. Scientific data 2016, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esteva, A.; Robicquet, A.; Ramsundar, B.; Kuleshov, V.; DePristo, M.; Chou, K.; Cui, C.; Corrado, G.; Thrun, S.; Dean, J. A guide to deep learning in healthcare. Nature medicine 2019, 25, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, S.; McPherson, J.D.; McCombie, W.R. Coming of age: ten years of next-generation sequencing technologies. Nature reviews genetics 2016, 17, 333–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwek, L.; Ellis, D.A.; Andrews, S.; Joinson, A. The rise of consumer health wearables: promises and barriers. PLoS medicine 2016, 13, e1001953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkomar, A.; Dean, J.; Kohane, I. Machine learning in medicine. New England Journal of Medicine 2019, 380, 1347–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaik, T.; Tao, X.; Li, L.; Xie, H.; Velásquez, J.D. A survey of multimodal information fusion for smart healthcare: Mapping the journey from data to wisdom. Information Fusion 2024, 102, 102040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; Ding, C.; Hu, X. Time Synchronization of Multimodal Physiological Signals through Alignment of Common Signal Types and Its Technical Considerations in Digital Health. Journal of Imaging 2022, 8, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Che, Z.; Purushotham, S.; Cho, K.; Sontag, D.; Liu, Y. Recurrent neural networks for multivariate time series with missing values. Scientific reports 2018, 8, 6085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Suk, H.I.; Shen, D. Multi-modality canonical feature selection for Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2014: 17th International Conference, Boston, MA, USA, 14-18 September 2014; Springer Proceedings, Part II 17. , 2014; pp. 162–169. [Google Scholar]

- Bannach, D.; Amft, O.; Lukowicz, P. Automatic event-based synchronization of multimodal data streams from wearable and ambient sensors. In Proceedings of the Smart Sensing and Context: 4th European Conference, EuroSSC 2009, Guildford, UK, 16-18 September 2009; Springer Proceedings 4. ; pp. 135–148. [Google Scholar]

- Esteban, C.; Hyland, S.L.; Rätsch, G. Real-valued (medical) time series generation with recurrent conditional gans. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.02633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitova, B.; Flusser, J. Image registration methods: a survey. Image and vision computing 2003, 21, 977–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipton, Z.C.; Kale, D.C.; Elkan, C.; Wetzel, R. Learning to diagnose with LSTM recurrent neural networks. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1511.03677. [Google Scholar]

- Baltrušaitis, T.; Ahuja, C.; Morency, L.P. Multimodal machine learning: A survey and taxonomy. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2018, 41, 423–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngiam, J.; Khosla, A.; Kim, M.; Nam, J.; Lee, H.; Ng, A.Y.; et al. Multimodal deep learning. Proceedings of the ICML 2011, Vol. 11, 689–696. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, X.; Yu, W.; Xu, R.; Cao, Z.; Shen, H.T. Combine early and late fusion together: A hybrid fusion framework for image-text matching. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME), 2021; IEEE; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Suk, H.I.; Lee, S.W.; Shen, D.; Initiative, A.D.N.; et al. Hierarchical feature representation and multimodal fusion with deep learning for AD/MCI diagnosis. NeuroImage 2014, 101, 569–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, J.; Corrado, G.; Monga, R.; Chen, K.; Devin, M.; Mao, M.; Ranzato, M.; Senior, A.; Tucker, P.; Yang, K.; et al. Large scale distributed deep networks. Advances in neural information processing systems 2012, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.C.; Pareek, A.; Seyyedi, S.; Banerjee, I.; Lungren, M.P. Fusion of medical imaging and electronic health records using deep learning: a systematic review and implementation guidelines. NPJ digital medicine 2020, 3, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.C.; Pareek, A.; Zamanian, R.; Banerjee, I.; Lungren, M.P. Multimodal fusion with deep neural networks for leveraging CT imaging and electronic health record: a case-study in pulmonary embolism detection. Scientific reports 2020, 10, 22147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kline, A.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Dennis, S.; Hutch, M.; Xu, Z.; Wang, F.; Cheng, F.; Luo, Y. Multimodal machine learning in precision health: A scoping review. npj Digital Medicine 2022, 5, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayesha, S.; Hanif, M.K.; Talib, R. Performance enhancement of predictive analytics for health informatics using dimensionality reduction techniques and fusion frameworks. IEEE Access; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dolly, J.M.; Nisa, A.K. A survey on different multimodal medical image fusion techniques and methods. In Proceedings of the 2019 1st International Conference on Innovations in Information and Communication Technology (ICIICT), 2019; IEEE; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Hermessi, H.; Mourali, O.; Zagrouba, E. Multimodal medical image fusion review: Theoretical background and recent advances. Signal Processing 2021, 183, 108036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snoek, C.G.; Worring, M.; Smeulders, A.W. Early versus late fusion in semantic video analysis. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 13th annual ACM international conference on Multimedia, 2005; pp. 399–402. [Google Scholar]

- Atrey, P.K.; Hossain, M.A.; El Saddik, A.; Kankanhalli, M.S. Multimodal fusion for multimedia analysis: a survey. Multimedia systems 2010, 16, 345–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandram, D.; Taylor, G.W. Deep multimodal learning: A survey on recent advances and trends. IEEE signal processing magazine 2017, 34, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, A.; Liang, P.P.; Mazumder, N.; Poria, S.; Cambria, E.; Morency, L.P. Memory fusion network for multi-view sequential learning. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, 2018; Vol. 32. [Google Scholar]

- Calixto, I.; Liu, Q.; Campbell, N. Doubly-attentive decoder for multi-modal neural machine translation. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1702.01287. [Google Scholar]

- Behrad, F.; Abadeh, M.S. An overview of deep learning methods for multimodal medical data mining. Expert Systems with Applications 2022, 200, 117006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Li, P.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, J. A survey on deep learning for multimodal data fusion. Neural Computation 2020, 32, 829–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, A.; Chen, M.; Poria, S.; Cambria, E.; Morency, L.P. Tensor fusion network for multimodal sentiment analysis. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.07250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Xu, H.; Tian, J.; Wang, W.; Yan, M.; Bi, B.; Ye, J.; Chen, H.; Xu, G.; Cao, Z.; et al. mPLUG: Effective and efficient vision-language learning by cross-modal skip-connections. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2205.12005. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Ye, Q.; Yan, M.; Shi, Y.; Ye, J.; Xu, Y.; Li, C.; Bi, B.; Qian, Q.; Wang, W.; et al. mplug-2: A modularized multi-modal foundation model across text, image and video. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.00402. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.; Batra, D.; Parikh, D.; Lee, S. Vilbert: Pretraining task-agnostic visiolinguistic representations for vision-and-language tasks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2019; Vol. 32. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, H.; Bansal, M. Lxmert: Learning cross-modality encoder representations from transformers. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1908.07490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wu, C.; Rosenman, S.; Lal, V.; Che, W.; Duan, N. Bridgetower: Building bridges between encoders in vision-language representation learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2023; Vol. 37, pp. 10637–10647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Yang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, S.; Asad, Z.; Coburn, L.A.; Wilson, K.T.; Landman, B.A.; Huo, Y. Deep multi-modal fusion of image and non-image data in disease diagnosis and prognosis: A review. arXiv 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, J.; Dong, W.; Socher, R.; Li, L.J.; Li, K.; Fei-Fei, L. ImageNet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2009; IEEE; pp. 248–255. [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi, S.; Goel, T.; Tanveer, M.; Murugan, R.; Sharma, R. Multi-modal fusion based deep learning network for effective diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. IEEE MultiMedia; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Holste, G.; Partridge, S.C.; Rahbar, H.; Biswas, D.; Lee, C.I.; Alessio, A.M. End-to-end learning of fused image and non-image features for improved breast cancer classification from MRI. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2021; pp. 3294–3303. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, R.; Zhang, F.; Rao, X.; Lv, Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Liang, S.; Li, Y.; Ren, F.; Zheng, C.; et al. Richer fusion network for breast cancer classification based on multimodal data. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 2021, 21, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdi, H.; Williams, L.J. Principal component analysis. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews: computational statistics 2010, 2, 433–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulos, P.; Pardalos, P.M.; Trafalis, T.B.; Xanthopoulos, P.; Pardalos, P.M.; Trafalis, T.B. Linear discriminant analysis. Robust data mining 2013, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, S.; Xu, W.; Yang, M.; Yu, K. 3D convolutional neural networks for human action recognition. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2012, 35, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litjens, G.; Kooi, T.; Bejnordi, B.E.; Setio, A.A.A.; Ciompi, F.; Ghafoorian, M.; Van Der Laak, J.A.; Van Ginneken, B.; Sánchez, C.I. A survey on deep learning in medical image analysis. Medical image analysis 2017, 42, 60–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braman, N.; Gordon, J.W.; Goossens, E.T.; Willis, C.; Stumpe, M.C.; Venkataraman, J. Deep orthogonal fusion: Multimodal prognostic biomarker discovery integrating radiology, pathology, genomic, and clinical data. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention; Springer, 2021; pp. 667–677. [Google Scholar]

- Vale Silva, L.A.; Rohr, K. Pan-cancer prognosis prediction using multimodal deep learning. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 17th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), 2020; IEEE; pp. 568–571. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, S.; Woerl, A.; Jungmann, F.; Glasner, C.; Stenzel, P.; Strobl, S.; Fernandez, A.; Wagner, D.; Haferkamp, A.; Mildenberger, Peter. Multimodal deep learning for prognosis prediction in renal cancer. Frontiers in Oncology 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, V.; Dhekane, S.; Tuniya, N.; Vyas, V. Image caption generator using attention mechanism. In Proceedings of the 2021 12th International Conference on Computing Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT), 2021; IEEE; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ghaleb, E.; Niehues, J.; Asteriadis, S. Joint modelling of audio-visual cues using attention mechanisms for emotion recognition. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2023, 82, 11239–11264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaques, N.; Taylor, S.; Sano, A.; Picard, R. Multimodal autoencoder: A deep learning approach to filling in missing sensor data and enabling better mood prediction. In Proceedings of the 2017 Seventh International Conference on Affective Computing and Intelligent Interaction (ACII), 2017; IEEE; pp. 202–208. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.; Sarma, P.; Sethares, W.; Liang, Y. Learning relationships between text, audio, and video via deep canonical correlation for multimodal language analysis. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence; 2020; Vol. 34, pp. 8992–8999. [Google Scholar]

- Andrew, G.; Arora, R.; Bilmes, J.; Livescu, K. Deep canonical correlation analysis. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2013; pp. 1247–1255. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A. Attention is all you need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, K. Show, attend and tell: Neural image caption generation with visual attention. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1502.03044. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, P.; He, X.; Buehler, C.; Teney, D.; Johnson, M.; Gould, S.; Zhang, L. Bottom-up and top-down attention for image captioning and visual question answering. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2018; pp. 6077–6086. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, W.; Son, B.; Kim, I. Vilt: Vision-and-language transformer without convolution or region supervision. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2021; pp. 5583–5594. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Selvaraju, R.; Gotmare, A.; Joty, S.; Xiong, C.; Hoi, S.C.H. Align before fuse: Vision and language representation learning with momentum distillation. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; 2021; Vol. 34, pp. 9694–9705. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.C.; Li, L.; Yu, L.; El Kholy, A.; Ahmed, F.; Gan, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, J. Uniter: Universal image-text representation learning. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Cham, 2020; pp. 104–120. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Huang, Q.; Celikyilmaz, A.; Gao, J.; Shen, D.; Wang, Y.F.; Wang, W.Y.; Zhang, L. Reinforced cross-modal matching and self-supervised imitation learning for vision-language navigation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2019; pp. 6629–6638. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, X.; Tang, C.; Zhang, W.; Sun, K.; Jiang, L. Hierarchical Attention Learning for Multimodal Classification. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME), 2023; IEEE; pp. 936–941. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.M.; Iqbal, T. Hamlet: A hierarchical multimodal attention-based human activity recognition algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), 2020; IEEE; pp. 10285–10292. [Google Scholar]

- Hardoon, D.R.; Szedmak, S.; Shawe-Taylor, J. Canonical correlation analysis: An overview with application to learning methods. Neural Computation 2004, 16, 2639–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, P.L.; Fyfe, C. Kernel and nonlinear canonical correlation analysis. International Journal of Neural Systems 2000, 10, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J.; et al. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2021; pp. 8748–8763. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, C.; Yang, Y.; Xia, Y.; Chen, Y.T.; Parekh, Z.; Pham, H.; Le, Q.; Sung, Y.H.; Li, Z.; Duerig, T. Scaling up visual and vision-language representation learning with noisy text supervision. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2021; pp. 4904–4916. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Yoon, W.; Kim, S.; Kim, D.; Kim, S.; So, C.H.; Kang, J. BioBERT: a pre-trained biomedical language representation model for biomedical text mining. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 1234–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.H.H.; Bai, S.; Liang, P.P.; Kolter, J.Z.; Morency, L.P.; Salakhutdinov, R. Multimodal transformer for unaligned multimodal language sequences. In Proceedings of the Conference. Association for Computational Linguistics. Meeting. NIH Public Access; 2019; Vol. 2019, p. 6558. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B.; Wattenberg, M.; Gilmer, J.; Cai, C.; Wexler, J.; Viegas, F. Interpretability beyond feature attribution: Quantitative testing with concept activation vectors (TCAV). In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2018; pp. 2668–2677. [Google Scholar]

- Rudin, C. Stop explaining black box machine learning models for high stakes decisions and use interpretable models instead. Nature Machine Intelligence 2019, 1, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Welling, M. Auto-Encoding Variational Bayes. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1312.6114. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative Adversarial Nets. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 2014; Vol. 27. [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh, A.; Pavlov, M.; Goh, G.; Gray, S.; Voss, C.; Radford, A.; Chen, M.; Sutskever, I. Zero-Shot Text-to-Image Generation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML). PMLR, 2021; pp. 8821–8831. [Google Scholar]

- Rombach, R.; Blattmann, A.; Lorenz, D.; Esser, P.; Ommer, B. High-Resolution Image Synthesis with Latent Diffusion Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2022; pp. 10684–10695. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, D.; Trullo, R.; Lian, J.; Wang, L.; Petitjean, C.; Ruan, S.; Wang, Q.; Shen, D. Medical Image Synthesis with Deep Convolutional Adversarial Networks. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2018, 65, 2720–2730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zemel, R.; Wu, Y.; Swersky, K.; Pitassi, T.; Dwork, C. Learning Fair Representations. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML). PMLR, 2013; pp. 325–333. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Pan, S.; Chen, F.; Long, G.; Zhang, C.; Yu, P.S. A Comprehensive Survey on Graph Neural Networks. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2020, 32, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipf, T.N.; Welling, M. Semi-Supervised Classification with Graph Convolutional Networks. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1609.02907. [Google Scholar]

- Veličković, P.; Cucurull, G.; Casanova, A.; Romero, A.; Liò, P.; Bengio, Y. Graph Attention Networks. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1710.10903. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, K.; Hu, W.; Leskovec, J.; Jegelka, S. How Powerful Are Graph Neural Networks? arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.00826. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, W.; Ying, Z.; Leskovec, J. Inductive Representation Learning on Large Graphs. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 2017; Vol. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, T.; Pan, Y.; Li, Y.; Mei, T. Exploring Visual Relationship for Image Captioning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), 2018; pp. 684–699. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Zeng, Z.; Liu, B.; Fu, D.; Fu, J. Pixel-BERT: Aligning Image Pixels with Text by Deep Multi-Modal Transformers. arXiv arXiv:2004.00849.

- Wu, Z.; Pan, S.; Chen, F.; Long, G.; Zhang, C.; Yu, P.S. A Comprehensive Survey on Graph Neural Networks. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2020, 32, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Chung, A.C. Edge-variational graph convolutional networks for uncertainty-aware disease prediction. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, 2020; Springer; pp. 562–572. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Fan, Y. Early prediction of Alzheimer’s disease dementia based on baseline hippocampal MRI and 1-year follow-up cognitive measures using deep recurrent neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 16th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI 2019), 2019; IEEE; pp. 368–371. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, T.; Thung, K.H.; Zhu, X.; Shen, D. Effective feature learning and fusion of multimodality data using stage-wise deep neural network for dementia diagnosis. Human Brain Mapping 2019, 40, 1001–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thung, K.H.; Yap, P.T.; Shen, D. Multi-stage diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease with incomplete multi-modal data via multi-task deep learning. In Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis and Multimodal Learning for Clinical Decision Support; Springer, 2017; pp. 160–168. [Google Scholar]

- El-Sappagh, S.; Abuhmed, T.; Islam, S.R.; Kwak, K.S. Multimodal multitask deep learning model for Alzheimer’s disease progression detection based on time series data. Neurocomputing 2020, 412, 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spasov, S.E.; Passamonti, L.; Duggento, A.; Liò, P.; Toschi, N. A multi-modal convolutional neural network framework for the prediction of Alzheimer’s disease. In Proceedings of the 2018 40th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC). IEEE, 2018; pp. 1271–1274. [Google Scholar]

- Venugopalan, J.; Tong, L.; Hassanzadeh, H.R.; Wang, M.D. Multimodal deep learning models for early detection of Alzheimer’s disease stage. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achalia, R.; Sinha, A.; Jacob, A.; Achalia, G.; Kaginalkar, V.; Venkatasubramanian, G.; Rao, N.P. A proof of concept machine learning analysis using multimodal neuroimaging and neurocognitive measures as predictive biomarker in bipolar disorder. Asian Journal of Psychiatry 2020, 50, 101984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, S.; Chang, G.H.; Panagia, M.; Gopal, D.M.; Au, R.; Kolachalama, V.B. Fusion of deep learning models of MRI scans, mini–mental state examination, and logical memory test enhances diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment & Disease Monitoring 2018, 10, 737–749. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosal, S.; Chen, Q.; Pergola, G.; et al. G-MIND: an end-to-end multimodal imaging-genetics framework for biomarker identification and disease classification. In Proceedings of the Medical Imaging 2021: Image Processing. SPIE; 2021; Vol. 11596, p. 115960C. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, D.; Lu, J.; Zhang, H.; Adeli, E.; Wang, J.; Yu, Z.; Liu, L.; Wang, Q.; Wu, J.; Shen, D. Multi-channel 3D deep feature learning for survival time prediction of brain tumor patients using multi-modal neuroimages. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duanmu, H.; Huang, P.B.; Brahmavar, S.; Lin, S.; Ren, T.; Kong, J.; Wang, F.; Duong, T.Q. Prediction of pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer using deep learning with integrative imaging, molecular and demographic data. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention; Springer, 2020; pp. 242–252. [Google Scholar]

- Yala, A.; Lehman, C.; Schuster, T.; Portnoi, T.; Barzilay, R. A deep learning mammography-based model for improved breast cancer risk prediction. Radiology 2019, 292, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Hu, P. Association analysis of deep genomic features extracted by denoising autoencoders in breast cancer. Cancers 2019, 11, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Shi, H.; Sui, D.; Hao, A.; Qin, H. A novel pathological images and genomic data fusion framework for breast cancer survival prediction. In Proceedings of the 2020 42nd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), 2020; IEEE; pp. 1384–1387. [Google Scholar]

- Kharazmi, P.; Kalia, S.; Lui, H.; Wang, J.; Lee, T. A feature fusion system for basal cell carcinoma detection through data-driven feature learning and patient profile. Skin Research and Technology 2018, 24, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, S.H.; Ahn, M.S.; Koh, Y.W.; Lee, S.J. A machine-learning approach using PET-based radiomics to predict the histological subtypes of lung cancer. Clinical Nuclear Medicine 2019, 44, 956–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheerla, A.; Gevaert, O. Deep learning with multimodal representation for pancancer prognosis prediction. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, i446–i454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinstein, E.; Salhov, M.; Nidam-Leshem, M.; White, V.; Golan, S.; Baniel, J.; Bernstine, H.; Groshar, D.; Averbuch, A. Unsupervised tumor detection in dynamic PET/CT imaging of the prostate. Medical Image Analysis 2019, 55, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Z.; Li, X.; Huang, H.; Guo, N.; Li, Q. Deep learning-based image segmentation on multimodal medical imaging. IEEE Transactions on Radiation and Plasma Medical Sciences 2019, 3, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palepu, A.; Beam, A.L. Tier: Text-image entropy regularization for clip-style models. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2212.06710. [Google Scholar]

- Bagheri, A.; Groenhof, T.K.J.; Veldhuis, W.B.; de Jong, P.A.; Asselbergs, F.W.; Oberski, D.L. Multimodal learning for cardiovascular risk prediction using ehr data. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 11th ACM International Conference on Bioinformatics, Computational Biology and Health Informatics. Association for Computing Machinery, 2020, pp. New York, NY, USA.

- Grant, D.; Papież, B.W.; Parsons, G.; Tarassenko, L.; Mahdi, A. Deep learning classification of cardiomegaly using combined imaging and non-imaging ICU data. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference on Medical Image Understanding and Analysis; Springer, 2021; pp. 547–558. [Google Scholar]

- Baltruschat, I.M.; Nickisch, H.; Grass, M.; Knopp, T.; Saalbach, A. Comparison of deep learning approaches for multi-label chest X-Ray classification. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugnara, G.; Neuberger, U.; Mahmutoglu, M.A.; Foltyn, M.; Herweh, C.; Nagel, S.; Schönenberger, S.; Heiland, S.; Ulfert, C.; Ringleb; Arthur, Peter. Multimodal predictive modeling of endovascular treatment outcome for acute ischemic stroke using machine-learning. Stroke 2020, 51, 3541–3551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimori, M.; Kiuchi, K.; Nishimura, K.; Kusano, K.; Yoshida, A.; Adachi, K.; Hirayama, Y.; Miyazaki, Y.; Fujiwara, R.; Sommer; Philipp. Accessory pathway analysis using a multimodal deep learning model. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, G.; Liao, R.; Wells, W.; Andreas, J.; Wang, X.; Berkowitz, S.; Horng, S.; Szolovits, P.; Golland, P. Joint modeling of chest radiographs and radiology reports for pulmonary edema assessment. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention; Springer, 2020; pp. 529–539. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, Z.; Lan, X.; Fu, L.; Wang, H.; Wen, H. Cohesive multi-modality feature learning and fusion for COVID-19 patient severity prediction. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology 2021, 32, 2535–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taleb, A.; Lippert, C.; Klein, T.; Nabi, M. Multimodal self-supervised learning for medical image analysis. In Proceedings of the Information Processing in Medical Imaging: 27th International Conference, IPMI 2021, Virtual Event, June 28–June 30, 2021; Springer, 2021; pp. 661–673. [Google Scholar]

- Purwar, S.; Tripathi, R.K.; Ranjan, R.; Saxena, R. Detection of microcytic hypochromia using CBC and blood film features extracted from convolution neural network by different classifiers. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2020, 79, 4573–4595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Bahadori, M.T.; Colak, A.; Bhatia, P.; Celikkaya, B.; Bhakta, R.; Senthivel, S.; Khalilia, M.; Navarro, D.; Zhang; Borui, e.a. Improving hospital mortality prediction with medical named entities and multimodal learning. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1811.12276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiulpin, A.; Klein, S.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S.M.; Thevenot, J.; Rahtu, E.; van Meurs, J.; Oei, E.H.; Saarakkala, S. Multimodal machine learning-based knee osteoarthritis progression prediction from plain radiographs and clinical data. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodin, I.; Fedulova, I.; Shelmanov, A.; Dylov, D.V. Multitask and multimodal neural network model for interpretable analysis of X-Ray images. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), 2019; IEEE; pp. 1601–1604. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).