1. Introduction

Container orchestration engines facilitate cloud services by automating the deployment, scaling, and management of containerized applications. Kubernetes [

1] is the predominant engine, offered as a managed service by major cloud providers, including Google Kubernetes Engine (GKE), Amazon Elastic Kubernetes Service (EKS), and Azure Kubernetes Service (AKS). Other engines, such as Docker Swarm [

2], OpenShift [

3], and Mesos [

4], provide alternative features and deployment models. Across all these platforms, orchestration enables containerized applications to be scheduled on available node resources and to scale according to workload fluctuations [

5].

The rapid development of cloud, edge, and Internet of Things (IoT) computing has created a strong need for unified orchestration frameworks that can manage extremely heterogeneous, distributed, and resource-constrained environments. Traditional cloud-native orchestration systems present significant limitations as they are not built inherently to facilitate autonomous, decentralized decision-making throughout the computing continuum or to seamlessly integrate non-container-native devices [

6]. Moving from cloud-centric clusters to this diverse continuum introduces several critical challenges [

7]: fast scaling and low-latency processing for many workloads remain difficult when resources are highly distributed; the efficient use of heterogeneous and sometimes constrained hardware, particularly in edge environments, is an active research problem; and finally, achieving interoperability between various protocols [

8] and device types requires suitable abstractions for networking, communication, and resource representation.

To address these limitations, the Distributed Adaptive Cloud Continuum Architecture (DACCA) is introduced as a novel Kubernetes-native framework designed to extend orchestration capabilities beyond the data center to encompass the entire continuum of highly heterogeneous edge and IoT infrastructures. DACCA facilitates a paradigm shift from centralized management to decentralized, intelligent operation through the integration of decentralized self-awareness and swarm formation. This capability enables adaptive and resilient operation, directly supporting fast scaling and low-latency processing. The architecture also establishes a resource and application abstraction layer to ensure uniform resource representation and resolve interoperability challenges, enabling seamless integration of constrained hardware. Furthermore, the distributed and adaptive resource optimization (DARO) framework, which utilizes multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL), ensures intelligent scheduling and optimized resource utilization. Finally, to guarantee verifiable identity, access control, and tamper-proof data exchange across heterogeneous domains, DACCA is reinforced by a zero-trust security framework based on distributed ledger technology (DLT).

The contributions of this paper lie in proposing and formalizing a unified orchestration model that we argue is essential for future cloud continuum platforms. Specifically, we integrate four key, interdependent elements into a single Kubernetes-native framework: decentralized self-awareness at the node level, dynamic swarm formation of nodes for adaptive, application-specific execution, distributed learning-based scheduling under partial observability (via the DARO framework), and a zero-trust security foundation that spans diverse administrative and operational boundaries (via the DLT framework). Although existing systems address isolated aspects of this pipeline, such as basic monitoring, device onboarding, centralized scheduling, or siloed security, they fail to provide an integrated, holistic framework in which nodes and applications can collaborate, adapt, and optimize their operations collectively across the entire continuum. DACCA supports this necessary integrated view, offering a concrete architectural blueprint toward the realization of truly autonomous and self-managing cloud-edge-IoT platforms.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 provides background information and related work.

Section 3 presents an overview of the proposed architecture.

Section 4 discusses the model of resources and application data, which are then used for discovery, management, and interoperability in

Section 5.

Section 6 introduces the mechanisms that equip nodes with self-awareness and autonomous decision-making capabilities.

Section 7 presents the Distributed and Adaptive Resource Optimization (DARO) framework.

Section 8 describes the decentralized trust and security framework.

Section 9 outlines further considerations and future work, while

Section 10 concludes the article.

2. Background and Related Work

Containerization and virtualization are core technologies that enable the abstraction, packaging, and deployment of applications in isolated environments. Many orchestration platforms and container engines exist to execute isolated applications and deploy them in various environments. Additionally, containerization significantly ensures portability, scalability, and efficient management of workloads throughout the computing continuum.

We have studied existing orchestration and management tools and made comparisons to reach a consensus on the best existing platform to build on. The comparison criteria were the features provided, scalability options, flexibility, and community support. Additionally, we preferred open-source solutions, but also studied and considered mainstream proprietary engines. We opted to use Kubernetes as a basis for building upon, and in the following paragraphs, we provide a comparison of other orchestration platforms with Kubernetes. This section provides an overview of some of the most popular container orchestration engines, highlighting their similarities and differences.

Kubernetes (K8s) [

1] is an open-source container orchestration system to automate software deployment, scaling, and management. Originally designed by Google, the project is now maintained by a worldwide community of contributors, and the trademark is held by the Cloud Native Computing Foundation. Kubernetes provides a modular microservice-based architecture that supports rich scalability options and autoscalers. It offers very easy scaling mechanisms out of the box. It is a highly flexible and customizable engine with broad community support.

Parallel to Kubernetes is Amazon EKS (Amazon Elastic Kubernetes Service) [

9]. EKS provides seamless integration with AWS services, comes with managed updates, scaling, and self-healing features, and has a large and active community. We did not proceed with EKS, as it is more complex to setup during its initial phase compared to Kubernetes, requires a good understanding of AWS (Amazon Web Services) and is costly for large-scale deployments.

Similarly to EKS, we looked into AKS (Azure Kubernetes Service) [

10], which natively integrates with Azure services, provides managed updates, scaling, and self-healing features, comes with very strong security mechanisms via Azure AD (Microsoft Entra ID) and also has an active community of developers. The cons are the same as in EKS: the complexity of setting up, the required deep knowledge of Azure infrastructure, and the high cost for large-scale deployments, all of which hinder the adoption of this option.

Another option we considered was Nomad [

11]. Nomad is an orchestration engine maintained by HashiCorp, that manages containerized applications within a single workflow. Although it is very simple to use, a key difference with Kubernetes is that Nomad focuses primarily on cluster management and scheduling. Kubernetes, on the other hand, provides a sophisticated ecosystem for managing clusters, in addition to deploying applications, including service discovery, monitoring, and other resource management capabilities.

OpenStack [

12] is another alternative, maintained by the OpenStack Foundation. OpenStack offers support not only for containerized applications but also for virtual machines and bare metal management. However, it is also complex to use and maintain, especially in relation to Kubernetes or Nomad.

OpenShift [

3] by Red Hat is also a known engine, providing advanced DevOps and CI/CD tools. Strong security and enterprise features are available, promoting hybrid cloud environments supported by a large and active community. However, it is a proprietary solution that requires knowledge of Red Hat infrastructure and is complex to set up and manage.

Another option we heavily considered was KubeEdge [

13]. This orchestration engine is based on Kubernetes, and, by design, it is additionally a strong option for supporting edge computing. Also, KubeEdge’s architecture is designed to operate utilizing device controllers that enable edge devices to communicate with the cloud. An important and key limitation is that KubeEdge is only intended to integrate the cloud with diverse edge devices, and does not extend its capabilities to deploying non-containerized applications to the edge and IoT devices, extending device heterogeneity. To achieve this, it is necessary to take a step back and redesign the device controllers to support this modular behavior.

Finally, we also considered Docker Swarm [

2], which provides extensive tools and ecosystem support, is simple to use, integrates with Docker Hub, and has a vast active community for support. However, it is much less popular than Kubernetes, requires additional setup for orchestration functionalities, and security and scalability features pose significant concerns for large-scale deployments.

After conducting an exhaustive study and comparison, we opted to use Kubernetes as the base orchestration engine and extend its capabilities to support more heterogeneous and multimodal devices as nodes. In addition, we will demonstrate how our proposed architecture further enhances security and trust, as well as the monitoring of nodes and ease of cluster management.

It is important to mention that none of the above orchestration engines has a straightforward or out-of-the-box feature to support deploying workloads to diverse edge devices (including smartphones and Android OS-based devices, in general). The existing scheduling components heavily (and only) rely on CPU, memory, and GPU utilization (as seen in Kubernetes and also applied in AWS payment policies) and thus do not provide a more sophisticated scheduler that takes various aspects into account. The ultimate aim is to support diverse applications on a cloud infrastructure containing multi-modal resources and devices, while taking security and trust into account. Our proposed architecture is based on Kubernetes, as it is the most popular open-source solution, addressing all these issues to sustain such requirements.

3. Architecture Overview

This paper presents the architecture of a distributed and adaptive cloud computing continuum that aims to extend and enhance existing cloud orchestration concepts, ideas, and approaches. Our proposed architecture is guided by the principles of modularity, scalability, and self-management. The ultimate goal is the seamless execution of data-intensive applications utilizing the full spectrum of the computing continuum, spanning from resource-constrained IoT devices at the edge to high-performance cloud infrastructures. The proposed architecture follows a layered, service-oriented approach, abstracting resource heterogeneity and promoting interoperability of interfaces and resource abstractions.

Our proposed architecture aims to offer a computing continuum landscape, achieving the seamless integration of diverse computational platforms, which can be:

IoT Devices and On-Device Nodes: Devices such as sensors, AR glasses, and micro controllers are integrated via lightweight communication protocols and connectors that translate their capabilities into Kubernetes-compatible descriptors.

Edge Infrastructure: Near- and far-edge nodes are equipped with enhanced awareness and resource monitoring capabilities, allowing them to participate in autonomous cluster formation and workload execution.

Cloud Infrastructure: High-performance centralized resources provide additional computing power and storage capacity for tasks requiring global state, deep analytics, or large-scale inference.

3.1. Kubernetes as a Basis

In our approach, we choose Kubernetes as the most suitable basis to build upon our architecture, as it enables workload orchestration, scalability, and optimal self-management of nodes. To justify our selection, we identify Kubernetes as presenting the following characteristics:

Orchestration of Heterogeneous Computing Nodes: Kubernetes contains flexible scheduling and networking policies that can enable heterogeneous nodes (i.e., nodes with very different resources) to participate in a unified ecosystem. Our architecture will extend these capabilities to integrate more types of computing nodes, such as Android Smartphone devices, Raspberry Pi devices, or other Single-Board Computers.

Dynamic Resource Allocation: Kubernetes provides a scheduler for resource management that assigns workloads and pods to appropriate nodes, taking into account constraints and enforcing policies. Decisions are strongly based on resource availability, latency constraints, custom policies, etc., allowing for dynamic reallocation of workloads optimizes execution of compute-intensive tasks in heterogeneous environments

Scalability: An elastic infrastructure capable of dynamically scaling applications poses a strong requirement in our architecture. Accommodating workloads on heterogeneous nodes requires horizontal and vertical autoscalers based on predefined policies, optimizing resource utilization across the entire computing continuum.

Advertising and Node Awareness: Nodes can announce their availability, capabilities, and resource constraints throughout the entire computing continuum. This ensures that processing workloads are assigned to the most suitable nodes, taking into account resource availability, latency, and energy efficiency. Kubernetes’ built-in mechanisms (node labels, taints, tolerations, and Custom Resource Definitions) effectively allow for the required node discovery and workload provisioning.

Resilience and Self-Healing: Kubernetes implements controllers for its self-healing mechanisms that automatically detect and recover from failures, ensuring high availability of applications.

Cloud-to-Edge Compatibility: Kubernetes ensures integration between cloud, edge, and IoT nodes by its ability to manage deployments across different environments. These deployments can be extended to edge and IoT environments through specialized configurations and extensions.

Security and Access Control: Security is the cornerstone of our proposed decentralized architecture. Kubernetes offers built-in Role-Based Access Control (RBAC), network policies, and encryption mechanisms out of the box, ensuring data integrity and preventing unauthorized access across the computing continuum.

Service Discovery and Load Balancing: Kubernetes provides a robust service discovery and load balancing framework, ensuring efficient inter-service communication across distributed computing nodes.

3.2. Scheduling and Scalability

A significant advantage of using Kubernetes in our architecture is that it already provides sophisticated mechanisms and core components to enhance workload distribution, scalability, and overall adaptability. The Kubernetes Scheduler allocates applications and resources, considering current resource utilization, latency requirements, and energy constraints. The execution of applications is optimized to achieve efficient execution in cloud-to-edge environments.

Kubernetes also provides the concept of autoscalers, packaged into the following mechanisms:

Cluster Autoscaler (CA): the required number of nodes can be dynamically adjusted, based on demand.

Horizontal Pod Autoscaler (HPA): the number of pod replicas is automatically adjusted, based on CPU and memory utilization.

Vertical Pod Autoscaler (VPA): the resource limits are adjusted for each individual pod, for optimal resource re-allocation but maintaining application performance.

Kubernetes can also isolate workloads logically, using namespaces. This allows its architecture to accommodate and easily manage diverse applications and workloads while maintaining security and isolation in different execution environments.

3.3. Top-Level Architecture

This section outlines the overarching architecture of the proposed DACCA framework, leveraging the fundamental capabilities of Kubernetes along with its scalability and scheduling mechanisms. The architecture is structured in layers employing a bottom-up design that enhances modularity, interoperability, and extensibility throughout the computing continuum. Each layer encompasses distinct functionalities, including device discovery, resource abstraction, decentralized decision-making, adaptive scheduling, and trust enforcement, creating a cohesive ecosystem that connects cloud, edge, and IoT infrastructures. This overview presents the primary architectural layers and demonstrates how their coordinated functioning facilitates seamless orchestration and intelligent workload management across diverse environments.

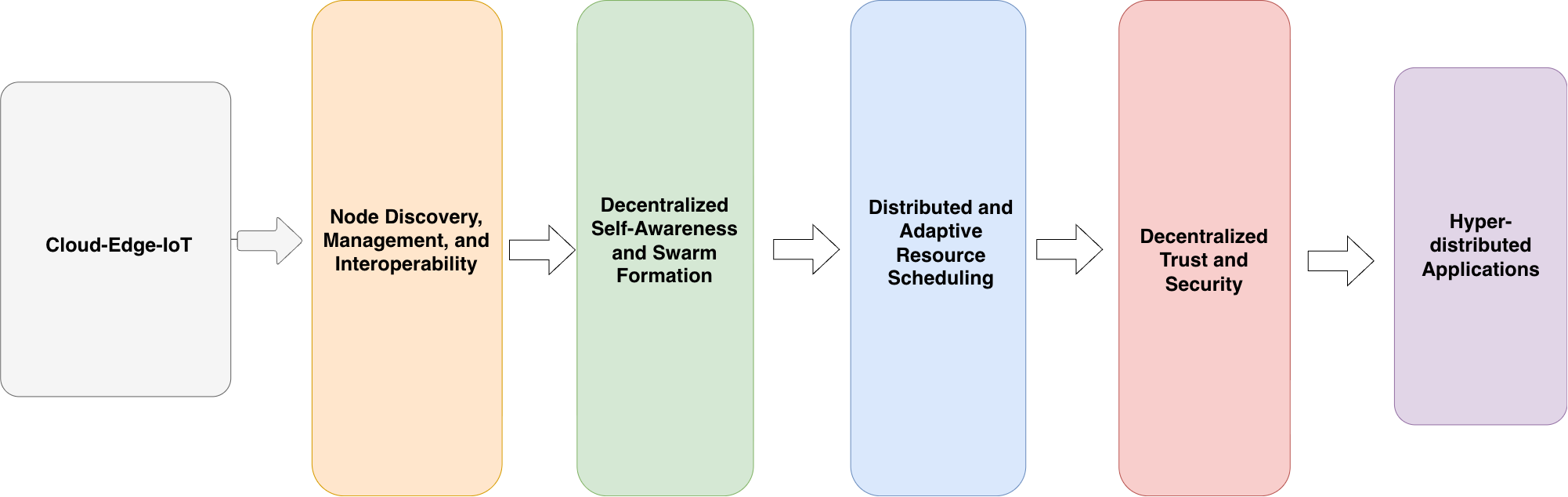

Our proposed architecture, visualized in

Figure 1, consists of the following discrete layers, following a bottom-up approach (the top layer is the Application layer).

The Applications layer, which consists of the various applications and workloads that are submitted to our platform.

The Decentralized Trust and Security layer, containing a security framework designed to implement a fully decentralized trust and security model combining Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) with the principles of Zero-Trust.

The Distributed and Adaptive Resource Scheduler (DARO), which is a Kubernetes-native scheduling system designed to support real-time resource management and task scheduling in large-scale heterogeneous environments. DARO is designed to operate effectively in resource-constrained, non-stationary, and cloud-edge-IoT environments.

Decentralized Self-Awareness and Swarm Formation layer, which introduces mechanisms equipping nodes with self-awareness and autonomous decision-making capabilities through decentralized monitoring and dynamic swarm formation.

The Node Discovery, Management, and Interoperability layer, which offers critical resource abstraction mechanisms for the discovery, management, and interoperability of nodes.

These layers create a unified and modular framework that facilitates seamless interoperability and intelligent orchestration throughout the computing continuum. The foundational lower layers, which facilitate node discovery, management, and interoperability, abstract device heterogeneity, enabling both container-native and non-container-native nodes to uniformly engage in the cluster. The decentralized self-awareness and swarm formation layer facilitates adaptive intelligence, enabling nodes to independently assess their status, cooperate, and dynamically organize into logical clusters based on workload demands. The distributed and adaptive resource scheduler enhances this foundation by facilitating efficient workload allocation via decentralized, learning-based decision-making, thereby ensuring optimal resource utilization and scalability across various environments. Lastly, the decentralized trust and security layer ensures that all system interactions are secure and verifiable by integrating distributed identity management, zero-trust principles, and tamper-proof auditability. When combined, these layers allow DACCA to fulfill its main objective, which is to provide a reliable, flexible, and robust orchestration framework for hyper-distributed cloud-edge-IoT systems.

4. Resource and Application Abstraction

4.1. Node Data Model

In this section, we describe the data models developed for implementing the resource abstraction and application layers. Cluster nodes, divided into physical and virtual machines, edge devices, and IoT devices, are represented in the data models. The application model represents the application execution framework necessary for executing applications within the proposed architecture.

Figure 2.

Data model for architecture cluster nodes.

Figure 2.

Data model for architecture cluster nodes.

The data models adopt traditional Kubernetes core cluster resources, configuration details, status, and conditions for cluster operations. A node has the following default sections:

The metadata (ObjectMeta), which is the metadata section associated with a node and describes identifying attributes for querying, monitoring, and managing each node (e.g., name, labels, creation timestamp).

The spec (NodeSpec), describing how Kubernetes should treat a node in terms of scheduling, networking, and provider information, and depicting the desired state of each node (e.g., scheduling policies, provider details).

The

status (NodeStatus), which is the current actual status of a node. Attributes provide real-time information about the resource capacity, connectivity, and health of a node (e.g., scheduling policies, provider details). The following tables provide examples of node conditions (

Table 1) and node addresses (

Table 2).

In our proposed architecture, we make use of the existing Kubernetes node data model and extend it by considering a categorization of a node using two abstraction entities, the Native Node and the Device Node. In our model, the Native Nodes constitute the traditional Kubernetes worker nodes capable of running containerized applications (i.e. pods). The Device Nodes refer to computational resources that cannot become Kubernetes nodes natively (i.e., either they are not capable of executing containers or do not support the minimum computational requirements).

4.1.1. Native Nodes Model

As already presented, the Native Nodes utilize the traditional Kubernetes node objects, which include:

Metadata (labels, annotations, name, etc.),

Spec (pod CIDR, taints, etc.),

Status (pod CIDR, taints, etc.).

However, this existing model focuses mainly on CPU, memory, ephemeral storage, and GPU utilization [

14]. The Native Node model expands the Kubernetes node model by introducing additional attributes that describe energy costs, sensors attached to nodes, network interfaces, and other properties, which result from including a broader range of devices in the cluster. The Native Node model uses additional node fields, labels, annotations, and taints to represent additional node properties (see

Figure 3).

4.1.2. Device Nodes Model

Device Nodes, which represent edge devices, do not directly participate in the Kubernetes cluster as Native Nodes can. Therefore, we use Custom Resource Definitions (CRD, [

15]) in the Kubernetes Control Plane to register the Device Nodes. To achieve a proper structure, we adhere to the standard Kubernetes metadata, spec, and status patterns.

4.2. Application Profile Model

Deploying applications across cloud, edge, and IoT environments requires a clear and consistent way of describing what an application needs in order to run correctly. The Application Profile Model (APM) addresses this requirement by providing a structured, machine-readable contract that captures the key properties of an application—its operational behavior, resource requirements, constraints, and execution context. These contracts, which we refer to as Application Profiles, ensure that all components involved in the deployment process interpret application requirements in the same way.

Application Profiles are built directly on the Application Data Model and offer a practical mechanism for expressing all relevant attributes in a predictable and schema-driven format. As shown in

Figure 4, the APM defines a clear structure that describes runtime settings, compute and accelerator needs, networking dependencies, constraints on placement, and Quality-of-Service (QoS) expectations. This structured representation makes it possible to validate, store, and reuse profiles across different platforms and deployment scenarios.

The APM’s core objectives are:

Standardising and validating application metadata: Profiles are written in YAML for readability but are validated against versioned JSON Schemas. This approach ensures that they follow a well-defined structure and contain all necessary fields, reducing the likelihood of errors when the profiles are processed by orchestration tools.

Supporting integration with orchestrators [

16]: The model is compatible with a wide range of applications, from Kubernetes-native workloads to device-specific and multi-service integration workflows. It supports both containerised and non-containerised execution, enabling a common representation across different technologies and environments.

Ensuring applicability across the computing continuum [

17]: The profile model is intentionally broad so it can describe applications intended for cloud servers, edge devices, or IoT endpoints. This allows an application to be defined once, then deployed wherever the required resources and conditions are met.

Each Application Profile is organised into three main sections, following the same structure used for the Node Data Model in

Section 4.1:

Metadata: Contains identifiers, annotations, and descriptive fields consistent with Kubernetes-style metadata conventions. This information supports indexing, categorisation, and traceability across tools and platforms.

Specs: Describes the desired state of the application, including runtime configuration, resource requirements such as CPU, memory, GPU, and accelerators, as well as networking needs, deployment constraints, sensor dependencies, and QoS expectations. This section provides orchestrators with all the information needed to make informed scheduling and placement decisions.

Status: Represents the observed state during execution to ensure completeness, and support monitoring and lifecycle management.

5. Node Discovery, Management, and Interoperability

This section is intended to describe the resources abstraction mechanisms required for the discovery, management, and interoperability of nodes. These mechanisms implement the functionalities to create the above-mentioned resource and application abstraction layer described in the previous section. The mechanisms developed are the discovery of nodes, their management, and the functionalities required to achieve smooth provisioning of applications and interoperability.

5.1. Mechanisms to Register, Discover, and Manage Heterogeneous Nodes

A self-advertisement mechanism is implemented to enable the registration, discovery, and management of heterogeneous nodes. Every new node must be seamlessly, robustly and securely added to the cluster with almost no user intervention. This enables a seamless workload distribution without the need for manual configurations. In the event that a node is unregistered or unexpectedly goes offline (due to an error or for maintenance), workloads are automatically redistributed across the remaining nodes. This leads to uninterrupted operations and overall cluster functionality.

In Kubernetes and other orchestration platforms, the management and addition of new nodes is not a straightforward process, despite the availability of partial automation for this process. This happens because of the assumption that all nodes are managed by administrators or system operators in stages to ensure reliability. In our proposed architecture, we provide a more user-friendly, robust, and streamlined approach to dynamically adding nodes. Our proposed solution, Hypertool, is a CLI tool developed to automate the discovery and registration of heterogeneous nodes. This tool facilitated all the required steps, from the dynamic creation of the node representation to its registration. Two output modes are provided: the Default, which displays primary steps and results for standard operations, and the Verbose, which provides detailed information about each step with diagnostics and logs for advanced troubleshooting and insights. Hypertool offers a secure, robust and efficient mechanism for integrating new nodes into the cluster, thus significantly reducing the complexity and manual effort required by users.

5.2. Cognitive Cloud Softwarized Infrastructure (Connectors)

In this section, we describe the implementation and architectural impact of Open Connectors, an abstraction layer on top of the cluster nodes. We describe a softwarized infrastructure that aims to interconnect multi-modal entities joining the cluster as nodes. The Open Connectors are implemented to enhance the interoperability of nodes and extend the management of computational, network, and storage resources.

The Open Connectors are implemented to create a mechanism for edge devices to join the cluster as nodes, although not capable of natively executing containers. Any computational resource with the crucial limitation mentioned above cannot become a node in any Kubernetes-based cluster. The Open Connectors enable these kinds of device to be registered as nodes and be available for scheduling applications to them. The implemented abstraction layer aims to extend the capabilities of existing Kubernetes orchestration engines by describing edge devices using familiar Kubernetes annotations.

The Open Connectors manage the self-advertisement and registration of the edge devices as Kubernetes custom resources and maintain the required network communications for monitoring them and delegating applications to them. This mechanism is intended for edge devices that are not capable of natively joining a Kubernetes cluster due to hardware limitations or the inability to execute any container runtime. The devices targeted to be registered as cluster nodes include Android OS-based devices (such as smartphones, AR glasses, and tablets) and Linux OS-based devices (e.g. Raspberry Pi). Edge devices are described in the Kubernetes cluster using Kubernetes Custom Resource Definitions (CRD). Two entities related to Open Connectors exist: the DeviceNode and the Application, both of which are described in their corresponding CRDs. Its entity has its corresponding controller for managing the CRD and the custom resources submitted.

The Open Connectors architecture is presented in

Figure 5 and consists of two main components: a controller and a communication connector. The controller operates in a Kubernetes-like approach [

18], maintaining the Custom Resources created for every edge device and for the applications submitted intended for these devices. The communication connector is used to receive information from the edge devices and to dispatch applications to them. All communications between edge devices use MQTT brokers such as Eclipse Mosquitto [

19], as they are lightweight and efficient. The controllers are divided into two categories: the Device Node and the Application controller. The Device Node controller creates and maintains Custom Resources, one per Device Node, and the Application controller transforms submitted applications into Custom Resources, managing their life cycle.

The Open Connectors operate as follows: a candidate edge device sends its details, device information, and available resources (hardware capabilities and onboard sensors) to the cluster. The Open Connectors device controller receives and validates this information, formulates a new custom resource, and submits it to the Kubernetes Control Plane via the API [

20]. If the custom resource is accepted, it is stored in the

etcd database and is considered an available cluster resource (i.e., traditional kubectl commands can obtain the resource and its description). The Device Node controller’s communication connector receives the status of every registered Device Node at an interval of 5 minutes per device and patches this information into the corresponding custom resource. In case the edge device fails to send its status, the Device Node is considered unavailable.

Similarly, the Application Controller intercepts the submission of applications intended to execute on a Device Node. Upon submission of such an application, the controller creates a custom resource containing all application information (edge device OS, application URL, required sensors, location, etc.) and leaves a specific field blank, which is the UUID of a candidate Device Node. The Open Connectors filter out the available Device Nodes based on their current resource utilization and hardware and sensor constraints, and fill the Device Node UUID attribute in the Application custom resource. This patch in the custom resource triggers the Applications controller’s communication connector to create the appropriate payload and send it to the application details to the selected Device Node. The sequence diagram for Open Connectors is visualized in

Figure 6.

6. Decentralized Self-Awareness and Swarm Formation

In this section, we introduce mechanisms that equip nodes with self-awareness and autonomous decision-making capabilities through decentralized monitoring and dynamic swarm formation. More specifically, we present a layered approach in which each node monitors its own state, curates anomalies, detects alarming events using embedded intelligence, and sends compressed state information to peer nodes. Thus, each node is capable of having a reliable estimation of the state of the system. Finally, building on this foundation, we present a swarm formation mechanism that dynamically groups nodes to meet application requirements, ensuring adaptive execution and resilience across heterogeneous and resource-constrained infrastructures.

6.1. Decentralized Monitoring and Self-Awareness

Creating a system that spans cloud infrastructures, edge settings, and IoT devices in a decentralized manner requires each node within it to be able to autonomously monitor, analyze, and communicate its own status. This level of self-awareness is crucial, as it enables each node to understand its capabilities and how it can contribute to the system. This can be achieved by placing lightweight modules on each node, with the goal of continuously collecting and examining operational data, such as CPU and memory usage, network latency, and energy levels. Thus, each node maintains an up-to-date and detailed view of its own health and capabilities.

In order to enable self-awareness in each node, the first step is to deploy an Anomaly Curation mechanism, which will allow continuous monitoring of each node’s raw metrics and ensure high-quality curated information for the whole architecture in a decentralized manner. This module will be responsible for combining various heterogeneous and cross-domain raw metrics from each node, collected from different sensors and devices, into a unified embedded representation.

Additionally, an

Alarming Events Detection mechanism builds upon the aforementioned collected curated data and enhances the capabilities of the anomaly detection mechanism by adding localization. This is achieved by comparing real-time measurements with patterns in the historical data, thereby identifying inconsistencies and patterned anomalies. Using different AI architecture models specialized in understanding time series patterns [

21,

22], it is possible to generate case-specific annotations. By embedding these annotations directly into the node metrics, nodes can understand their operational state and capabilities, thereby improving their decision-making in other parts of the system.

Nevertheless, knowledge of a node’s capabilities is insufficient to understand how it fits into the entire system compared to the other nodes in the cluster. This gives rise to the need for a

Full-State Estimation mechanism, so that each node has a sense of the whole system it resides in. Using autoencoder architectures [

23], each node encodes its own curated state data and possible annotations coming from the aforementioned mechanisms, resulting in a compact/compressed state representation vector. Then each node sends these embeddings to all other cluster nodes via the default Kubernetes API or a peer-to-peer protocol [

24], in order to reduce the communication overhead. After receiving this information, the nodes reconstruct the initial state vector of their peers through a decoder. This mechanism ensures that each node has a comprehensive view of the whole system without violating bandwidth constraints.

Kubernetes integration of the above modules is achieved by deploying each as a distinct DaemonSet, ensuring that they run consistently on every node and allowing for seamless scaling across heterogeneous infrastructures. The entire framework extends the in-place Kubernetes metrics system, adding new insights, without disrupting standard operations. The envisioned architecture is depicted in

Figure 7, illustrating the placement of the aforementioned modules within each node and their coexistence with in-node Kubernetes components, such as kubelet and kube proxy. Through this design, the platform achieves a decentralized foundation for resilient, scalable, and intelligent self-management throughout the computing continuum.

6.2. Swarm Formation

Critical applications require guaranteed resources and high reliability. By dynamically forming swarms of nodes (logical clusters within the physical cluster), each dedicated to an application’s requirements, the system ensures reliable execution even under fluctuating workloads and heterogeneous infrastructure conditions. Forming a suitable logical cluster for each application’s execution requires global knowledge and coordination. In our approach, this is handled by selecting a leader node among the worker nodes to be responsible for creating the logical cluster that matches the application’s needs.

Every time an application arrives at the Control Plane, the Logical Cluster Manager selects a leader node among the worker nodes through a rotating leader strategy, periodically designating different nodes to act as leaders, as long as they meet reliability criteria. The selected leader then initiates the logical cluster formation process by sending the application’s requirements, including CPU, memory, etc., to the rest of the worker nodes in the system. Each node decides to offer to participate in the logical cluster based on the requirements received and its own computational resources.

After the leader node has received the responses from the worker nodes (with respect to a timeout limit), it formulates and solves a Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) problem [

25] to determine the optimal set of nodes to form the logical cluster. This ensures that the selected group can meet the application’s demand while respecting the constraints related to the tasks comprising it, thereby avoiding unnecessary resource fragmentation and preserving capacity for future applications. When the logical cluster is finalized, the leader node informs the Control Plane about the outcome. While the application is running, the leader node continuously monitors for node failures, demand increases/decreases, and partially reruns the MILP process to dynamically reshape the cluster without disrupting the application’s execution.

Kubernetes integration of the above logic is accomplished by deploying

Local Node Agents in each node as a DaemonSet and the Logical Cluster Manager as a custom controller at the Control Plane. This framework seamlessly extends native Kubernetes resource management mechanisms, embedding advanced clustering and optimization capabilities without disrupting standard operations. The architecture is depicted in

Figure 8, highlighting how the Logical Cluster Manager and Local Node Agents are placed within the Kubernetes environment alongside core components such as kubelet and kube-proxy. Through this design, the platform establishes a decentralized, yet coordinated foundation for forming application-specific logical clusters, enabling resilient, adaptive, and efficient execution across the entire computing continuum.

7. Distributed and Adaptive Resource Scheduling

This section introduces the

Distributed and Adaptive Resource Optimization (DARO) framework, a Kubernetes-native scheduling system designed to support real-time resource management and task scheduling in large-scale heterogeneous environments. DARO leverages a cooperative

Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning (MARL) approach [

26] to overcome the limitations of centralized scheduling, such as scalability bottlenecks, single points of failure, and poor adaptability in dynamic workloads [

27]. Unlike traditional centralized schedulers, DARO employs decentralized decision-making under partial observability, enabling it to operate effectively in resource-constrained, non-stationary, and cloud-edge-IoT environments [

28]. Each agent learns to make local scheduling decisions while contributing to a globally efficient task allocation policy.

7.1. Architectural Components

The primary objective of DARO is to perform resource allocation and task scheduling, considering various aspects, including the balance of resource utilization among distributed nodes and the proximity of tasks to the data they require (either from storage or other tasks). Its architecture follows an asynchronous Kubernetes-native pattern and consists of four building blocks: the Scheduler Broker, the Distributed Reinforcement Learning (RL) Agents, a Delayed Feedback Repository, and a set of Application Programming Interfaces (APIs). The DARO framework, including its core components and their interactions, is illustrated within the Kubernetes architecture in

Figure 9.

The core of the system is the Scheduler Broker, which operates within the Kubernetes Control Plane and coordinates the scheduling process. It replaces the default scheduler and is responsible for managing task submissions, broadcasting task specifications to worker nodes, collecting responses from distributed agents, and finalizing scheduling decisions by interacting with the Kubernetes API server.

Each worker node hosts an autonomous

Distributed Reinforcement Learning (RL) Agent that evaluates the incoming scheduling opportunities. These agents make independent decisions based on task information (e.g. resource requirements, data needs) as well as local observations, such as CPU and memory availability, current workload, data locality, and network conditions [

29]. By learning over time, each agent improves its ability to bid for tasks in a way that balances resource efficiency, data transmission, and task performance.

In addition, DARO includes a Delayed Feedback Repository that stores structured execution records containing task outcomes (i.e. success or failure), resource consumption, execution latency, and periodic snapshots of the state of the system. This repository supports off-policy learning and delayed reward computation.

Finally, a set of Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) facilitates communication between DARO components and the broader Kubernetes system. These APIs allow the broker to bind pods, agents to access resource metrics, and external modules to interact with the scheduler, ensuring tight integration with the Kubernetes ecosystem and other architectural layers in the framework.

7.2. Task Scheduling Workflow

DARO replaces the default Kubernetes scheduling workflow with a decentralized, MARL-driven alternative, as shown in

Figure 10:

When a new pod is marked as unscheduled by the Kubernetes API server, the Scheduler Broker is notified and initiates the scheduling process.

The Scheduler Broker filters eligible nodes based on hard constraints and broadcasts task metadata to the available RL Agents.

Each RL agent computes a bid based on task information and local metrics (such as CPU, memory, and bandwidth) and sends it back to the Scheduler Broker.

The Broker receives and ranks the bids, selects the most suitable node, and binds the pod via the Kubernetes API.

The selected node’s kubelet retrieves the pod specification and launches the container.

Relevant data, including task parameters, bid values, system state, and execution results, are captured by the Delayed Feedback Repository.

The data from the Delayed Feedback Repository are used to compute reward signals that guide the agents’ learning and adaptation over time, thereby improving future scheduling decisions.

7.3. Integration with the Proposed Architecture

DARO is integrated into the broader proposed architecture, benefiting from the outputs of several supporting modules:

Higher-level abstractions (see

Section 4) and mechanisms (see

Section 5) provide semantic context about applications and resources to support informed and constraint-aware scheduling decisions.

Real-time system state estimation (see

Section 6.1) improves local agent decision-making by providing accurate, up-to-date resource metrics.

Logical nodes clustering (see

Section 6.2) informs how the nodes should coordinate and manage data locality in the infrastructure.

Together, these modules form a closed-loop control system that begins with system monitoring, proceeds through logical clustering, task placement, and resource allocation, and continuously adapts to changing workload patterns and infrastructure conditions.

8. Decentralized Trust and Security

The described security framework is designed to implement a fully decentralized trust and security model by tightly integrating Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) [

30] with the principles of Zero-Trust. The architecture combines Hyperledger Fabric, the Extensible Access Control Markup Language (XACML) [

31], distributed policy enforcement points, and an application-level encryption layer provided through EncryptFlow. Hyperledger Fabric, which operates as a permissioned blockchain, establishes the foundational trust layer by ensuring verifiable participant identities, immutable storage of access control policies, and decentralized credential management via Decentralized Identifiers (DIDs) [

32]. Its modular architecture supports flexible deployments across multiple organizations and provides fault-tolerant consensus, thus reducing the exposure and trust limitations typically associated with public blockchains. The general structure and interaction of these components are illustrated in

Figure 11, which provides an overview of the architecture.

In addition to this secure ledger foundation, XACML introduces a dynamic and context-sensitive attribute-based access control (ABAC) mechanism [

33]. In contrast to static role-based models, ABAC evaluates access requests in real-time using multiple attributes, contextual parameters, and risk indicators. Storing both policies and attributes directly on the blockchain ensures that access control decisions remain traceable, tamper-resistant, and consistently enforced across the system. This capability is realized through a coordinated network of specialized nodes: Hyperledger Fabric nodes manage decentralized identities and preserve immutable policies, XACML nodes serve as decision points for real-time authorization, and PEP-Proxy nodes act as distributed enforcement points that intercept requests and verify their validity before granting access.

To extend the Zero-Trust paradigm beyond access control and into data protection, the framework integrates EncryptFlow [

34], a portable end-to-end encryption and decentralized key management solution. EncryptFlow ensures that sensitive data remains encrypted throughout its life-cycle, from generation to authorized processing, while assigning full control of key management to the data owner. This approach protects confidentiality and integrity, aligning with the same decentralized verification-first principles used for identity and access management, thus creating a cohesive and unified trust model across all layers of the architecture.

8.1. Implementation of DLT-Based Security

The practical implementation of this design involves the deployment of a DLT-based security architecture to provide secure identity management and access control in decentralized environments. Hyperledger Fabric serves as the backbone for storing identity records, access policies, and attributes, offering a tamper-proof and auditable ledger. In parallel, XACML operates as the policy decision point, evaluating each authorization request against the policies and contextual data recorded on the blockchain. These authorization decisions are enforced in real-time by PEP-Proxy components, which act as distributed entry points within the architecture. Each PEP-Proxy intercepts incoming access requests, verifies the validity of the access token included in the request, and grants or denies access accordingly. Together, these components remove the dependency on centralized intermediaries and ensure operational alignment with Zero-Trust principles.

To enable these capabilities, two dedicated smart contracts are deployed in Hyperledger Fabric. The first manages policies and attributes through an indexed JSON structure, allowing for registration, version-controlled updates, and retrieval by domain or type. This structure ensures that authorization always relies on the most current rules while preserving historical versions for audit and compliance purposes. The second smart contract provides immutable logging of authorization requests, supporting historical analysis and forensic investigation while preventing any modification of stored records. Both smart contracts are accessed via a REST API, which offers a standardized interface for XACML and other security components to interact with the ledger. This separation of policy logic from direct blockchain interaction improves scalability, simplifies integration, and facilitates interoperability between different components.

EncryptFlow functions as an additional cryptographic enforcement layer, providing encryption at the source, controlled decryption at authorized processing points, and decentralized key management under the control of the data owner. When sensitive data are generated, they are encrypted using key material provided by the owner’s key manager. Any entity requiring access must submit a formal decryption request, which is evaluated against the policies stored on the blockchain. Approved requests result in the delivery of wrapped decryption keys, while both successful and rejected requests are authenticated via DIDs and recorded in an immutable audit log. By combining immutable policy management, context-aware ABAC decision-making, and user-controlled encryption, the implementation ensures that access rights and data confidentiality are preserved within a transparent, verifiable, and decentralized framework.

To conclude this section, it is essential to clarify how the proposed decentralized trust layer integrates with Kubernetes’ native access control mechanisms. The DLT-based Zero-Trust framework does not replace Kubernetes’ built-in security features; instead, it complements them. Kubernetes continues to enforce authentication and authorization within the cluster, while the blockchain layer provides verifiable identity, immutable policy storage, and policy consistency across heterogeneous environments—capabilities that extend beyond traditional cluster-scoped enforcement.

Although this additional verification introduces an additional authorization step, the associated overhead remains modest, as policy checks occur mainly during identity validation rather than during every cluster interaction. In practice, this approach preserves expected Kubernetes performance characteristics (e.g., scheduler latency and API responsiveness) while enabling decentralized trust and secure interoperability across diverse environments.

8.2. Operational Workflow of Zero-Trust Security

The process starts with the establishment of trusted identities for all participating nodes. Within each node, the component known as the Holder is responsible for generating and storing the Decentralized Identifier (DID) locally. This process begins with the creation of a cryptographic key pair using the ES256K algorithm, followed by the construction of a DID document that contains identity metadata and a verification method to retrieve the public key. Once generated, the DID is also registered in Hyperledger Fabric, ensuring both immutability and verifiable ownership. The diagram illustrating the DID creation and registration process is shown in

Figure 12. In parallel, the node acquires a Verifiable Credential either at deployment or when first requesting access to a protected resource. This issuance involves a secure, multi-step interaction with an issuer, resulting in a signed credential that will be presented in future authorization requests.

Once identities and credentials are in place, the management of access policies and attributes follows a consistent blockchain-backed process. XACML submits a JSON policy or attribute set via the REST API, using the identifier as the blockchain key to guarantee uniqueness and immutability. Updates follow a version-controlled model in which the timestamp and version number are incremented while the identifier remains constant, thereby preserving a full change history. Retrieval can be scoped to specific domains or performed globally, ensuring that enforcement components always operate with the latest relevant policy data. Authorization itself proceeds in a structured manner. When a resource request is made, the verifier sends the resource, subject, and action parameters to XACML, which compares them with the policies stored in the ledger. If the policy decision is “Permit”, the verifier generates a signed access token. This token is then validated by the PEP-Proxy before granting access, ensuring that each request is explicitly verified and that any unauthorized attempt is blocked at the entry point.

Data protection workflows integrate seamlessly with this process through EncryptFlow. A task that produces sensitive data encrypts them with keys obtained from the owner’s key manager, after which the encrypted data can be stored or transmitted without risk of exposure. If another task needs to process these data, it creates a share request embedded within the encrypted content and sends it to the key manager. The request is evaluated according to the access policies, and if approved, the requester receives the wrapped decryption keys. All exchanges are logged in detail, creating an immutable audit trail that supports compliance verification and dispute resolution. Through this tightly integrated sequence of steps, our proposed architecture maintains a decentralized, verifiable, and context-sensitive security process that protects both the identity and data layers, ensuring integrity, confidentiality, and trust across the entire platform.

9. Discussion and Future Work

In this section, we will present additional reflections on the various aspects of the proposed architecture discussed in this article. Although numerous cloud–edge–IoT orchestration systems have emerged over the past decade, including KubeEdge, Open Horizon, and hybrid cloud frameworks, these solutions typically address isolated parts of the continuum stack. Existing systems provide device connectivity, basic offloading or edge-aware scheduling, but do not offer a unified approach that spans heterogeneous device abstraction, decentralized monitoring, autonomous logical cluster formation, learning-enabled scheduling, and Zero-Trust security. DACCA argues that genuine autonomy in the computing continuum can only emerge from the integration of these capabilities into a single coherent architecture. This architectural convergence distinguishes DACCA from prior approaches that have focused narrowly on scheduling strategies, IoT integration, or Kubernetes edge extensions, without addressing the full end-to-end orchestration pipeline.

It is essential to explain why this architecture can support a broader range of complex and multi-modal applications and workloads. First, the architecture consists of heterogeneous computational resources, including diverse edge devices (e.g., Android and Linux-based devices), which have been identified as extremely useful but introduce very interesting design and implementation challenges. In general, container orchestration engines are used to set up cloud services and manage computational and networking resources. Container orchestration engines automate the deployment of applications, provide scaling mechanisms and automation when needed, and offer tools and interfaces for managing any containerized application. Moreover, load balancing between services can be automated or enforced, and in general, it is easy to apply additional networking policies for every specified cloud service.

9.1. Autonomy and Adaptivity

Our proposed architecture aims to unify cloud, edge, and IoT under a Kubernetes-native orchestration ecosystem. As discussed previously, this is only partially achieved by other existing orchestration systems, such as KubeEdge or OpenShift. Our proposed architecture incorporates additional tools that either extend the native capabilities of Kubernetes (e.g., Hypertool, Open Connectors) or adopt the Kubernetes principles but are redesigned to add more features and technologies (e.g., DARO scheduler, self-monitoring, DLT trust mechanisms). The latter tools are not natively provided by Kubernetes but operate by adopting the same principles of orchestration, scalability, compatibility between multi-modal nodes, and security.

The proposed architecture is capable of self-adapting and self-managing all workloads and resources in various dynamic large-scale environments. In

Section 2, we briefly presented many existing orchestration platforms, including Kubernetes, which rely heavily on predefined scaling and resource utilization policies. These mechanisms are not efficient when applied to highly heterogeneous infrastructures, which contain multi-modal nodes with computing incompatibilities, especially when energy and networking limitations are present. Our proposed architecture was initially designed to address all these challenges by creating abstraction layers and embedding intelligence in each layer. The proposed architecture offers a decentralized self-awareness mechanism (i.e., Monitoring and Swarm Formation) that, in conjunction with the DARO scheduler, facilitates achieving autonomy and resilience across heterogeneous environments.

The Decentralized Self-Awareness mechanisms provide tools for every node to monitor itself, detect any anomalies that occur, and exchange its state with other nodes. The entire cluster is capable of maintaining accurate self-situational awareness, without relying on a central monitoring service (e.g., Prometheus). Using AI-driven anomaly detection and autoencoder-based full-state estimation, nodes can manage performance issues, detect bottlenecks, and adapt accordingly. Communication overhead is minimized, and all correcting actions are performed in real-time.

Another layer is the Swarm Formation mechanism, which enables nodes to dynamically form logical clusters, adapting to specific application requirements. The swarms are created to provide sub-clusters to the users. They are capable of reconfiguring themselves in response to any failure or change in resource availability. Efficient resource aggregation and reliability are enhanced by this adaptive clustering technique, which can be applied to various variable workloads.

The Distributed and Adaptive Resource Optimization (DARO) framework further reinforces adaptivity at the scheduling layer. DARO is a distributed, multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL) approach for scheduling applications, which enables nodes to learn over time and improve their scheduling policies based on resource and other requirements. Although each agent acts and learns independently, it contributes to a globally efficient scheduling policy. As time passes, the system converges towards optimal task placement strategies and decisions that further account for latency, data locality, and resource balance. The interaction between self-awareness, swarm formation, and MARL scheduling creates a closed-loop adaptive system capable of continuous self-optimization.

All of the above layers provide a very strong and robust foundation for autonomy and adaptability towards deployed workloads. However, maintaining the stability and interoperability of such autonomous decision-making processes is always challenging and remains a direction for future research.

9.2. Scalability, Interoperability and Security Considerations

The proposed architecture aims to enhance scalability across heterogeneous devices (mentioned in a previous section as Device Nodes). Through the Resource and Abstraction layer in our architectural hierarchy, we provide a unified representation of cloud, edge, and IoT resources, enabling uniform orchestration across edge device classes that are otherwise incompatible. The introduction of Open Connectors further extends interoperability, allowing non-container-native devices (e.g., Android OS-based devices) to operate as Kubernetes cluster nodes using Custom Resource Definitions (CRDs). This significantly broadens the applicability of containerized orchestration to diverse ecosystems, including wearables, AR devices, industrial IoT sensors, and other edge devices.

The above requires additional security mechanisms to be enforced, which can be accomplished with the Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) framework. This framework enforces identity management, access control, and auditability in a tamper-proof and Zero-Trust manner. Confidentiality and traceability are improved, despite some computational and storage overhead being introduced.

9.3. Limitations

Despite its promising potential, the proposed architecture also introduces several design and implementation challenges. Firstly, embedding distributed intelligence in every node increases the system’s complexity and may lead to higher energy consumption on constrained devices. Second, the MARL-based scheduling framework, while scalable in principle, requires careful tuning to prevent excessive network communication and ensure convergence under dynamic conditions. Third, integration of DLT mechanisms may cause latency overhead in time-sensitive operations, especially when dealing with large-scale geographically distributed deployments. Furthermore, interoperability testing across diverse network configurations, varying communication protocols, and different operating systems represents a non-trivial engineering effort that requires systematic validation.

9.4. Future Work

The architecture presented provides a foundation for a new generation of self-managing and intelligent orchestration frameworks that can efficiently bridge between cloud, edge, and IoT infrastructures. It is by integrating decentralized intelligence, adaptive scheduling, and verifiable trust that we lay the foundation for an autonomous computing continuum, where nodes and applications participate in a dynamic collaboration to negotiate resources and adapt to contextual changes in real-time. This model opens up the path towards cognitive orchestration systems, i.e., platforms that not only deploy and scale applications but also constantly monitor performance, energy efficiency, or data locality to guarantee optimal execution without intervention from a human operator. In doing so, our proposed architecture provides not only a technical roadmap for distributed orchestration using AI, but also a systematic model for self-evolving computing environments that can sustain promising paradigms, such as AI-driven networking and federated intelligence, with regard to context-adaptive services across the full computing continuum.

Future research will focus on evaluating and validating our proposed architecture in real-world scenarios. We aim to deploy our orchestration platform in hybrid cloud infrastructures, which also contain edge and IoT environments and devices. Current implementations have been deployed within the scope of a European-funded research project named HYPER-AI [

35]. All of the above layers (and not only) are currently under development, and a first version of them has been tested and open-sourced [

36]. The project’s goal is to provide a unified container orchestration platform with all the proposed features. Specific use cases have been agreed upon to test and stress this new orchestration platform in several real-world settings and industries, including farming and agriculture, mobility and automotive, green energy, healthcare, and Industry 4.0.

10. Conclusions

To facilitate the smooth orchestration and execution of workloads across the cloud-edge-IoT continuum, this paper presents a native unified Kubernetes architecture. By extending the conventional cloud orchestration paradigm, the suggested framework creates a distributed, self-governing, and trust-aware ecosystem that can dynamically adjust to changing infrastructure conditions and diverse device capabilities. The proposed architecture provides an integrated solution that bridges the gap between cloud-native and edge-native computing paradigms through abstraction layers and components, including the Resource and Application Abstraction Layer, Open Connectors, Decentralized Self-Awareness and Swarm Formation mechanisms, the Distributed and Adaptive Resource Optimization (DARO) scheduler, and the DLT-based Zero-Trust Security framework.

For nodes to self-monitor, cooperate, and collectively optimize resource allocation without centralized control, the architecture distinguishes itself by integrating intelligence and autonomy at multiple levels. This design improves responsiveness, scalability, and fault tolerance in settings with varying computational resources, limited connectivity, and volatility. A verifiable trust foundation is also provided by the integration of distributed ledger technologies and attribute-based access control, which guarantees the decentralized and impenetrable maintenance of data integrity, identity management, and authorization.

The proposed architecture creates a robust framework for overseeing the next generation of complex, AI-driven, and multimodal applications through the integration of adaptability, decentralization, and trust. The proposed architecture offers a collection of innovative mechanisms and a unified design philosophy that transforms the perception and orchestration of computing resources across boundaries. Future efforts will encompass experimental validation and performance benchmarking in extensive testbeds, the enhancement of learning-based scheduling algorithms, and the investigation of lightweight blockchain architectures to optimize security and efficiency.

We aim to establish the foundation for autonomous, scalable, and reliable orchestration in hyper-distributed environments, representing progress toward achieving a genuinely intelligent computing continuum.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.D., H.H. and P.S.; methodology, N.D., M.A., H.H. and P.S.; software, V.P., M.L., M.T., S.M.U.H., T.M., E.B., K.I., I.T.M., S.V., E.K., F.J.R.M., R.M.P., M.A., J.C. and P.S.; validation, N.D., H.H. and P.S.; formal analysis, N.D., H.H. and P.S.; investigation, all authors; resources, all authors; data curation, all authors; writing—original draft preparation, N.D., V.P., M.L., M.T., S.M.U.H., T.M., E.B., K.I., J.C. and P.S.; writing—review and editing, all authors; visualization, V.P., M.L., M.T., S.M.U.H., T.M., E.B., K.I., M.A., J.C. and P.S.; supervision, N.D., H.H., S.V., E.K. and P.S.; project administration, N.D., H.H., S.V., E.K. and P.S.; funding acquisition, N.D., H.H., S.V., E.K. and P.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new datasets were generated or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

This work has been partially supported by the HYPER-AI project, funded by the European Commission under Grant Agreement 101135982 through the Horizon Europe research and innovation program (

https://hyper-ai-project.eu/).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DACCA |

Distributed Adaptive Cloud Continuum Architecture |

| DARO |

Distributed and Adaptive Resource Optimization |

| DLT |

Distributed Ledger Technology |

| IoT |

Internet of Things |

| K8s |

Kubernetes |

| RBAC |

Role-Based Access Control |

References

- The Kubernetes Authors. Kubernetes: Production-Grade Container Orchestration. Accessed: 13 November 2025.

- Docker Inc.. Swarm mode – Docker Engine. Accessed: 13 November 2025.

- Red Hat Inc.. Red Hat OpenShift – Develop, modernize, and deploy applications at scale on a trusted and consistent platform. Accessed: 13 November 2025.

- Apache Software Foundation. Apache Mesos. Accessed: 13 November 2025.

- Al Jawarneh, I.; Bellavista, P.; Bosi, F.; Foschini, L.; Martuscelli, G.; Montanari, R.; Palopoli, A. Container orchestration engines: A thorough functional and performance comparison. In Proceedings of the ICC 2019 – IEEE International Conference on Communications, 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; Kiss, T.; Kovács, J.; Tusa, F.; Deslauriers, J.; Dagdeviren, H.; Arjun, R.; Hamzeh, H. Orchestration in the cloud-to-things compute continuum: taxonomy, survey and future directions. Journal of Cloud Computing 2023, 12, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkonis, P.; Giannopoulos, A.; Trakadas, P.; Masip-Bruin, X.; D’Andria, F. A survey on IoT-edge-cloud continuum systems: Status, challenges, use cases, and open issues. Future Internet 2023, 15, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shames, P.; Sarrel, M. A modeling pattern for layered system interfaces. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 25th Annual INCOSE International Symposium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Amazon Web Services Inc.. Amazon Elastic Kubernetes Service (EKS) – Build, run, and scale production-grade Kubernetes applications. Accessed: 13 November 2025.

- Microsoft Corporation. Azure Kubernetes Service (AKS) – Deploy and scale containers on managed Kubernetes. Accessed: 13 November 2025.

- HashiCorp Inc.. Nomad: A Simple and Flexible Scheduler and Orchestrator. Accessed: 13 November 2025.

- The OpenStack Project. OpenStack – Open Source Cloud Computing Infrastructure. Accessed: 13 November 2025.

- KubeEdge Project Authors. KubeEdge: A Kubernetes Native Edge Computing Framework. Accessed: 13 November 2025.

- Cyfuture Cloud. Specifications for Minimum and Maximum Node Sizes in a Kubernetes Cluster. Accessed: 13 November 2025.

- The Kubernetes Authors. Kubernetes Custom Resources. Accessed: 13 November 2025.

- Weerasiri, D.; Barukh, M.; Benatallah, B.; Sheng, Q.; Ranjan, R. A taxonomy and survey of cloud resource orchestration techniques. ACM Computing Surveys 2017, 50, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Woensel, W.; Abibi, S. Optimizing and benchmarking OWL2 RL for semantic reasoning on mobile platforms. Semantic Web 2019, 10, 637–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Kubernetes Authors. Kubernetes Controllers: Ensuring Desired State in Distributed Systems. Accessed: 13 November 2025.

- Eclipse Foundation. Eclipse Mosquitto: An Open-Source MQTT Broker. Accessed: 13 November 2025.

- The Kubernetes Authors. Kubernetes API Overview. Accessed: 13 November 2025.

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.; Kaiser; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. arXiv 2023, arXiv:cs.CL/1706.03762. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.; Welling, M. Auto-Encoding Variational Bayes. arXiv 2022, arXiv:stat.ML/1312.6114. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, V.; Krstulovic, J.; Keko, H.; Moreira, C.; Pereira, J. Reconstructing missing data in state estimation with autoencoders. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2011, 27, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, B.; Srisuresh, P.; Kegel, D. Peer-to-peer communication across network address translators. In Proceedings of the USENIX Annual Technical Conference, General Track, 2005; pp. 179–192. [Google Scholar]

- Floudas, C.; Lin, X. Mixed integer linear programming in process scheduling: Modeling, algorithms, and applications. Annals of Operations Research 2005, 139, 131–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, S.; Christianos, F.; Schäfer, L. Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning: Foundations and Modern Approaches; MIT Press, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hady, M.; Hu, S.; Pratama, M.; Cao, J.; Kowalczyk, R. Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning for Resources Allocation Optimization: A Survey. arXiv 2025, [arXiv:cs.DC/2504.21048].

- Roberts, J.; Nair, V. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Adaptive Resource Allocation in Cloud Computing. International Journal on Advanced Electrical and Computer Engineering 2025, 13, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Malipatil, A.; Paramasivam, M.; Gulyamova, D.; Saravanan, A.; Ramesh, J.; Muniyandy, E.; Ghodhbani, R. Energy-Efficient Cloud Computing Through Reinforcement Learning-Based Workload Scheduling. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science & Applications 2025, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Soltani, R.; Zaman, M.; Joshi, R.; Sampalli, S. Distributed Ledger Technologies and Their Applications: A Review. Applied Sciences 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OASIS Standard. eXtensible Access Control Markup Language (XACML) Version 3.0. Technical report, OASIS, 2013. Accessed: 13 November 2025.

- Sporny, M.; Longley, D.; Markus, S.; Reed, D.; Steele, O.; Allen, C. Decentralized Identifiers (DIDs) v1.0. Accessed: 13 November 2025.

- Picard, N.; Colin, J.N.; Zampunieris, D. Context-aware and attribute-based access control applying proactive computing to IoT system. In Proceedings of the IoTBDS 2018: 3rd International Conference on Internet of Things, Big Data and Security, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.; Xie, D.; Zhang, G.; Chen, F.; Wang, T.; Hu, P. EncryptFlow: Efficient and Lossless Image Encryption Network Based on Normalizing Flows. IEEE Transactions on Artificial Intelligence, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- HYPER-AI. Hyper-Distributed Artificial Intelligence Platform. Accessed: 13 November 2025.

- HYPER-AI. HYPER-AI Project GitLab. Accessed: 13 November 2025.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).