Submitted:

15 December 2025

Posted:

17 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

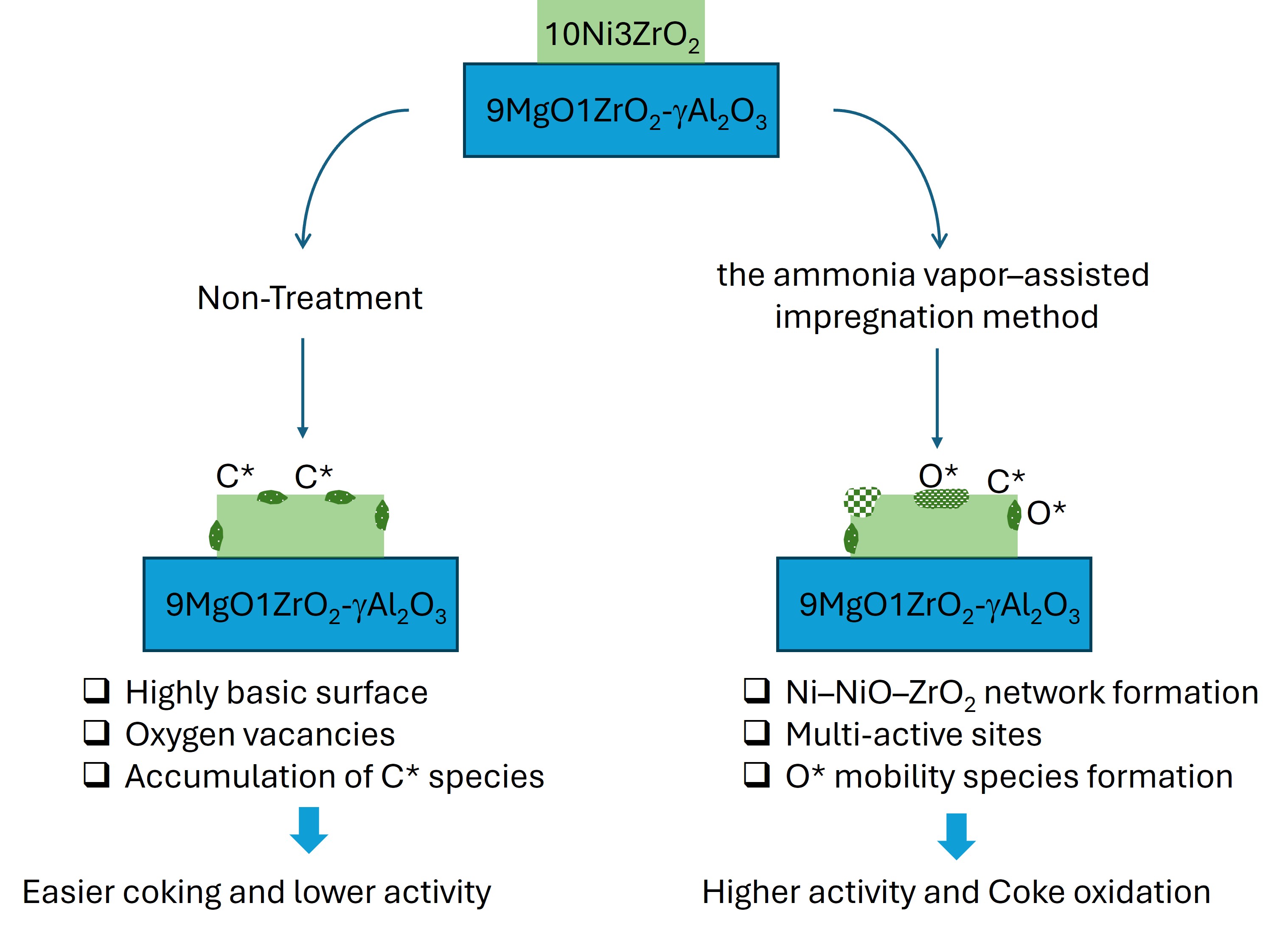

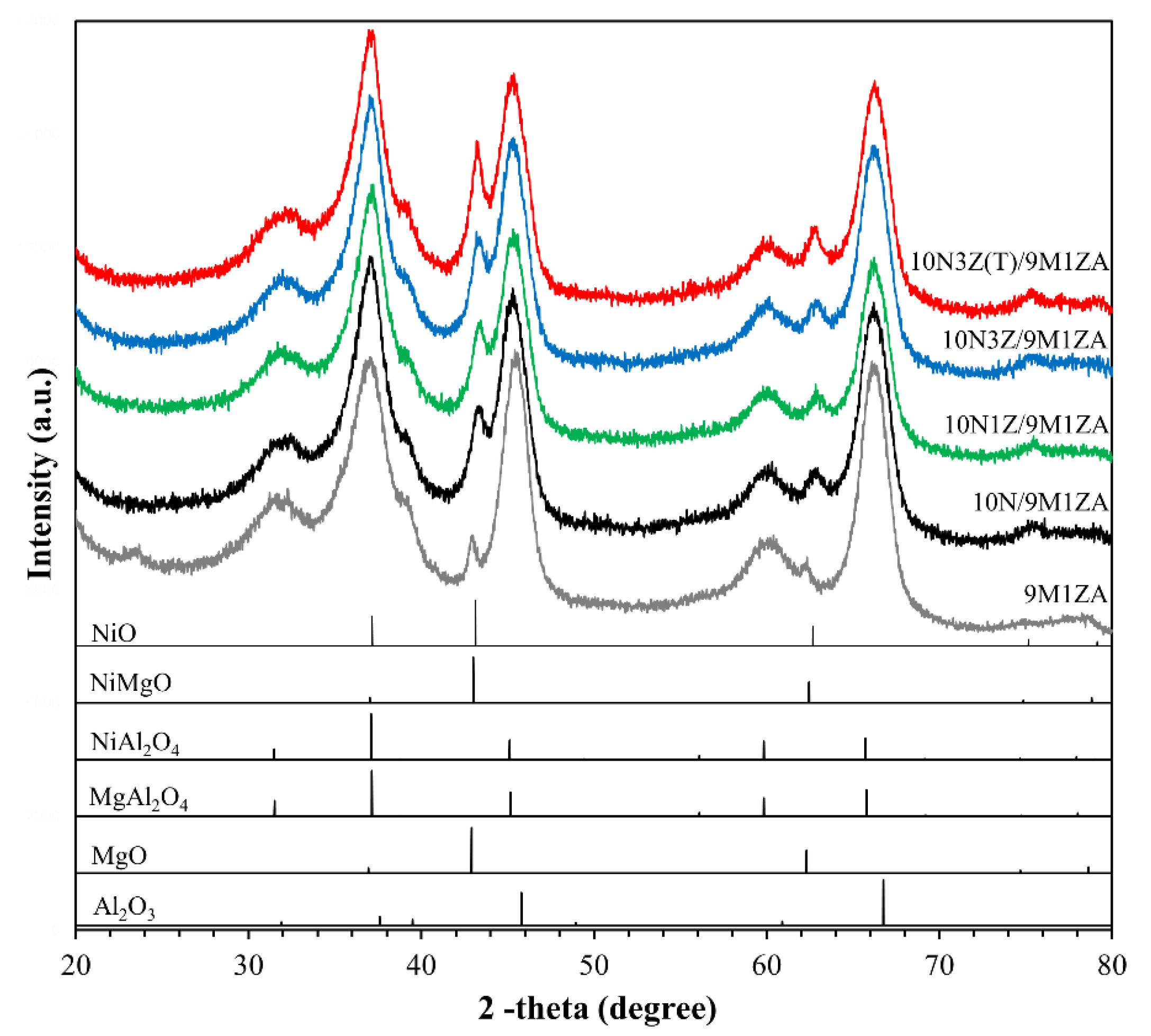

This study investigates the development of Ni-based catalysts for low-temperature dry methane reforming (DMR) at 550 °C. The catalysts were prepared by dispersing Ni on γ-Al2O3 modified with 9 wt% MgO and 1 wt% ZrO2, while 10 wt% Ni–x wt% ZrO2 promoters (0, 1, and 3 wt%) were introduced using the incipient wetness impregnation method. A Ni–NiO–ZrO2 surface network was generated on the 10 wt% Ni–3 wt% ZrO2 catalyst via an ammonia vapor–assisted impregnation route. The ZrO2 promoter strengthened the metal–support interaction, which increased the total amount of reducible Ni while shifting the reduction to higher temperatures. This modification also promoted CO2 activation relative to CH4, thereby enhancing the RWGS pathway and lowering the H2/CO ratio. In contrast, the Ni–NiO–ZrO2 network formed through the ammonia-assisted method increased the concentration of surface-accessible Ni, reduced excessive coverage by ZrO2, and significantly improved oxygen mobility. These features facilitated continuous oxygen transfer, enhanced coke oxidation, and ensured a more balanced activation of both reactants. Overall, the combined structural and functional synergies achieved through promoter optimization and the ammonia vapor–assisted preparation method resulted in superior catalytic activity and selectivity for DMR at 550 °C.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

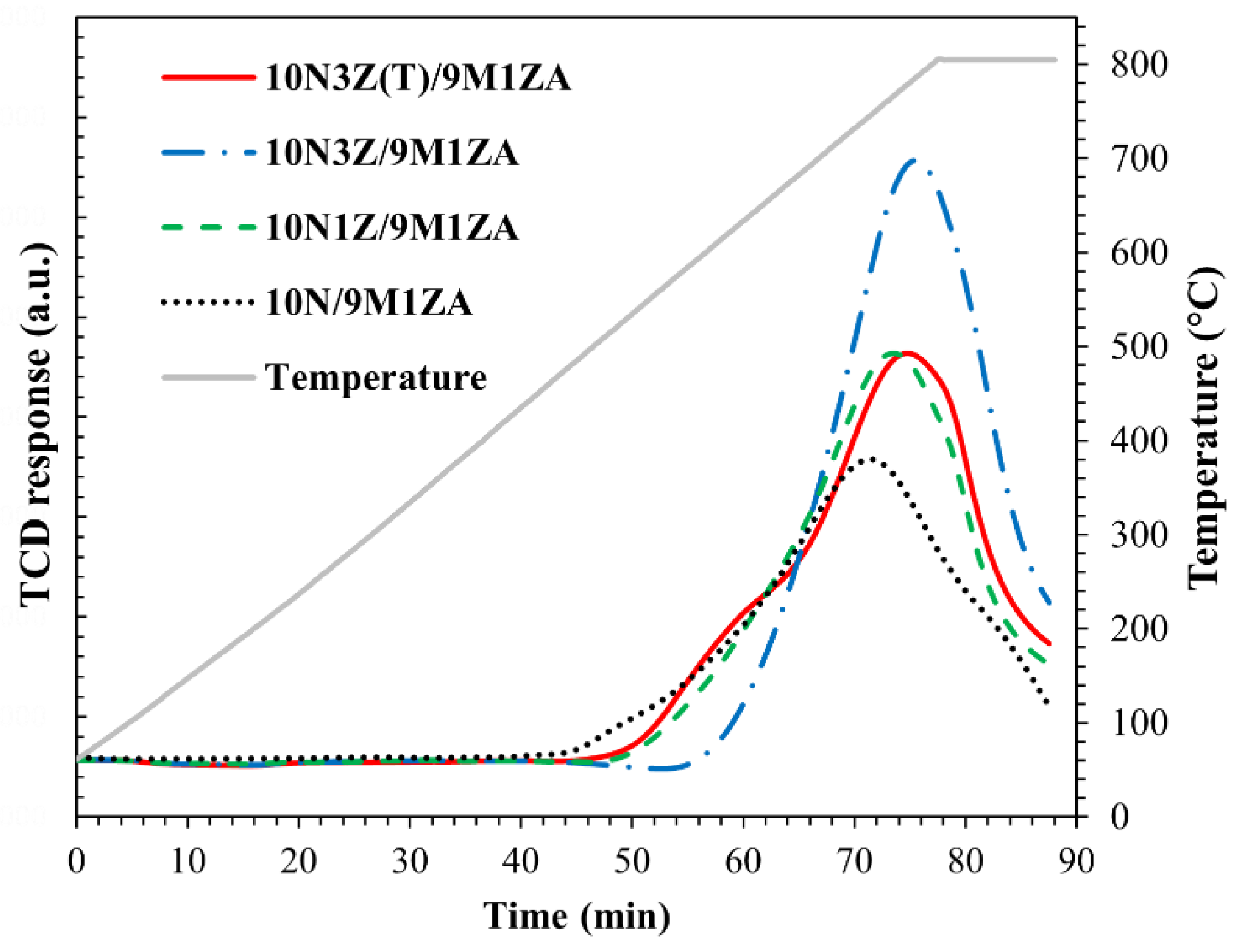

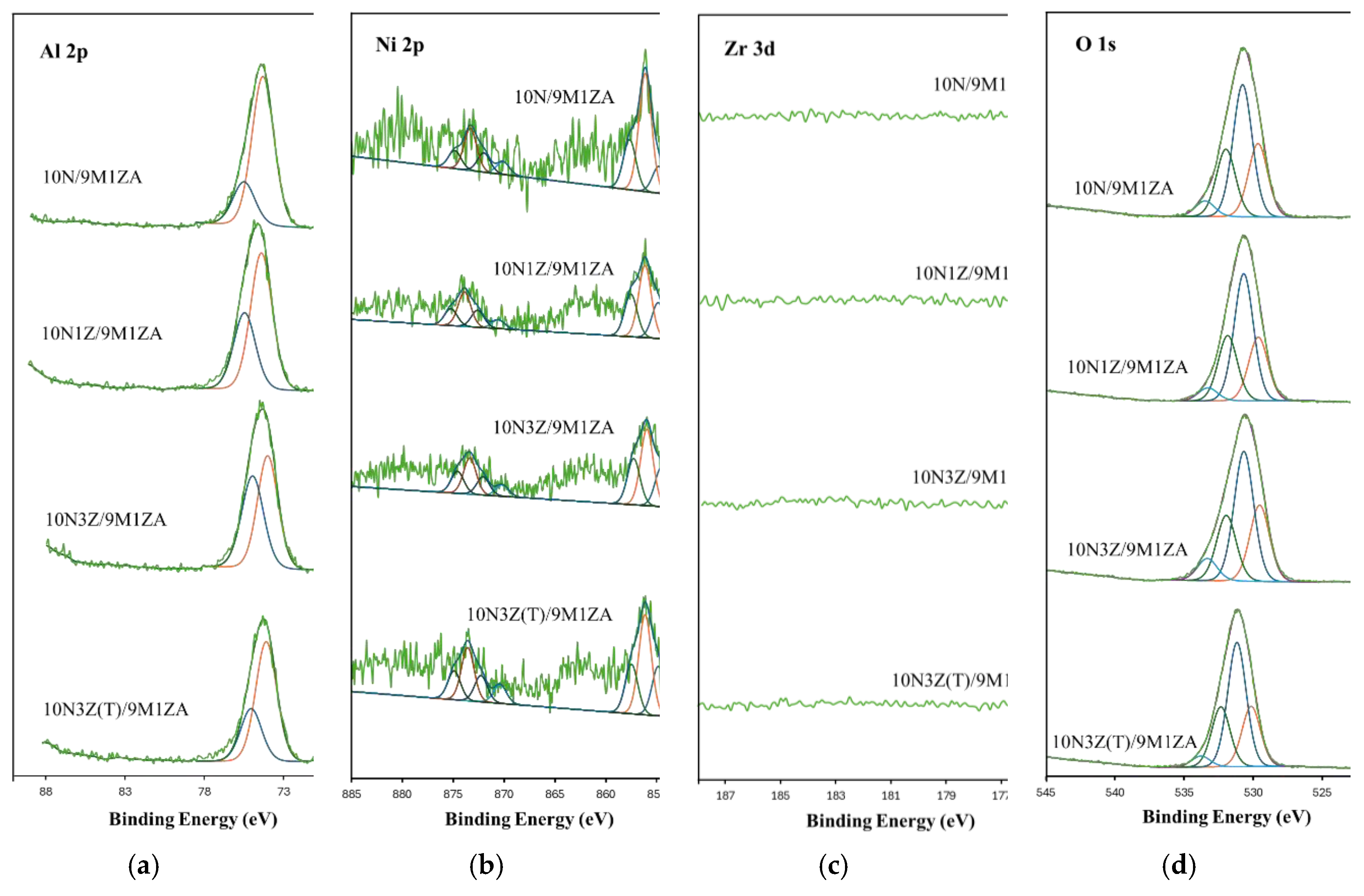

2.1. Catalyst Characterization

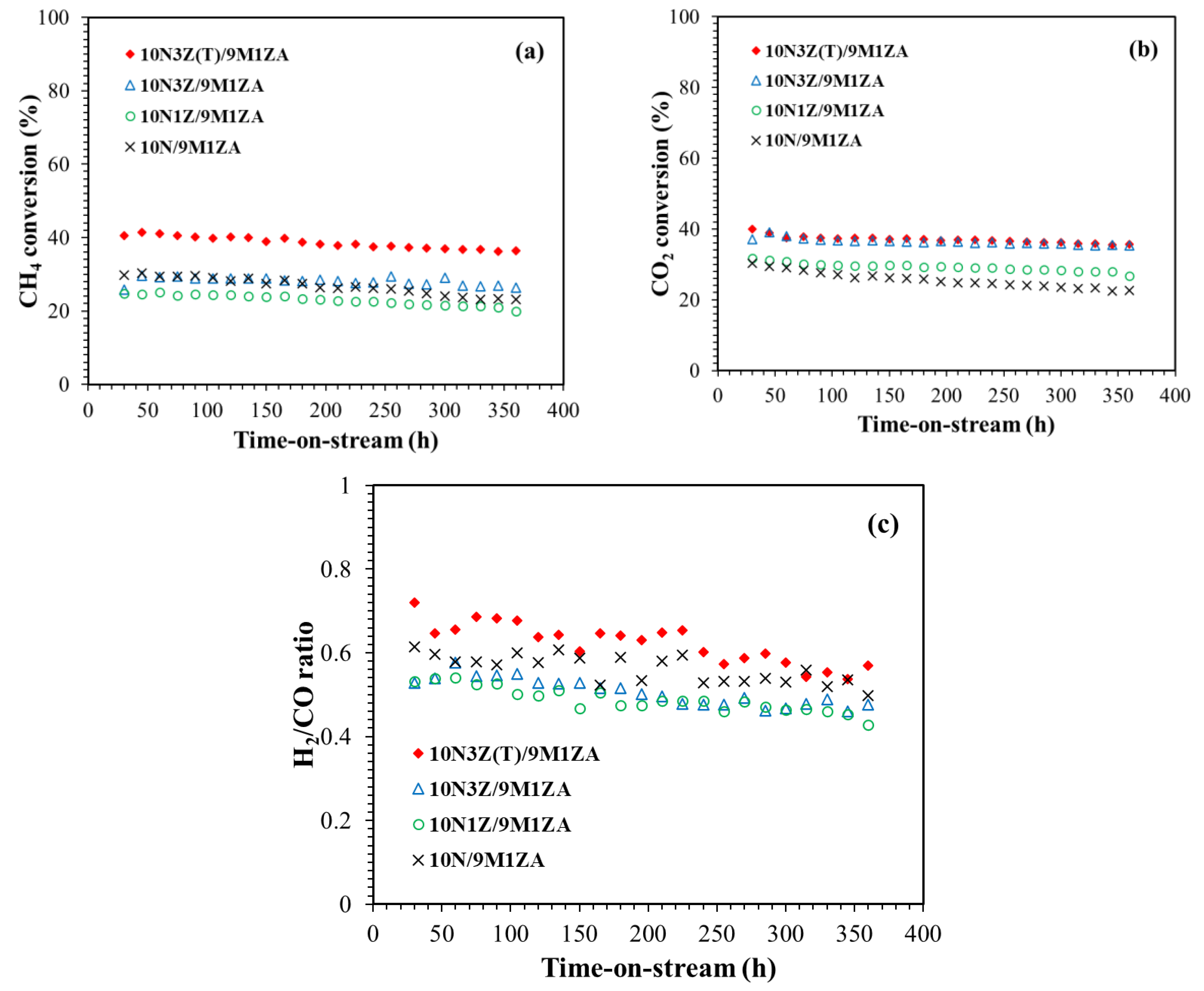

2.2. Catalytic Performance in the DMR Reaction

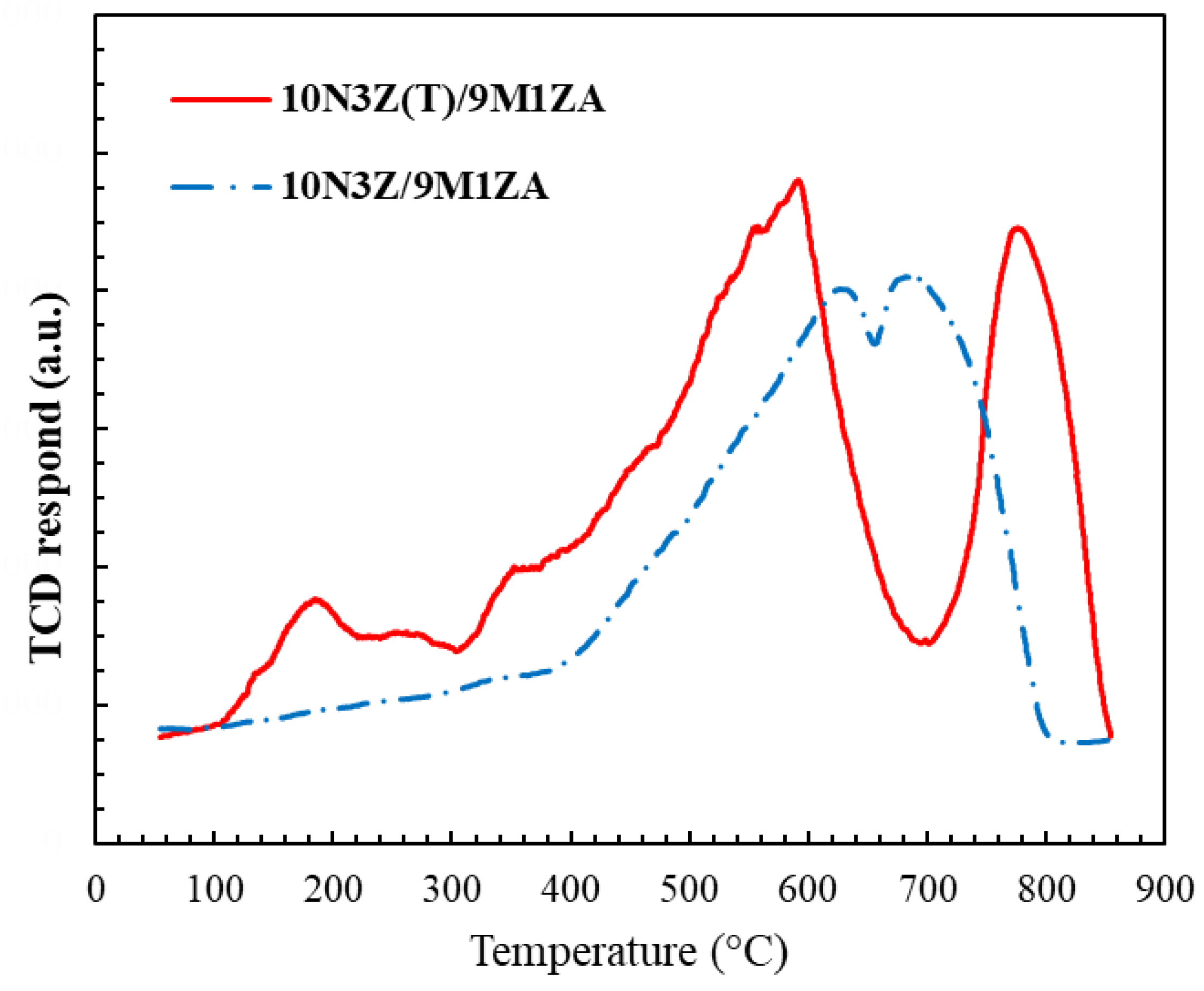

2.3. Carbon Deposits on Spent Catalysts

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Catalyst Preparation

3.2. Catalyst Characterization

3.3. Catalytic Test

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Elegbeleye, I.; Oguntona, O.; Elegbeleye, F. Green Hydrogen: Pathway to Net Zero Green House Gas Emission and Global Climate Change Mitigation. Hydrogen (Switzerland) 2025, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulrasheed, A.; Jalil, A.A.; Gambo, Y.; Ibrahim, M.; Hambali, H.U.; Shahul Hamid, M.Y. A Review on Catalyst Development for Dry Reforming of Methane to Syngas: Recent Advances. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2019, 108, 175–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakeeha, A.; Kurdi, A.; Al-Baqmaa, Y.; Ibrahim, A.; Abasaeed, A.; Al-Fatesh, A. Performance Study of Methane Dry Reforming on Ni/ZrO2 Catalyst. Energies (Basel) 2022, 15, 3841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Mei, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, K.; Xie, W.; Xin, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J. Electrified Dry Reforming of Methane on Ni-La 2 O 3-Loaded Activated Carbon: A Net CO2-Negative Reaction 2025, Vol. 11.

- Ranjekar, A.M.; Yadav, G.D. Dry Reforming of Methane for Syngas Production: A Review and Assessment of Catalyst Development and Efficacy. Journal of the Indian Chemical Society 2021, 98, 100002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, K.; Sasmal, S.; Badgandi, S.; Chowdhury, D.R.; Nair, V. Dry Reforming of Methane to Syngas: A Potential Alternative Process for Value Added Chemicals—a Techno-Economic Perspective. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2016, 23, 22267–22273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhassan, A.M.; Hussain, I.; Taialla, O.A.; Awad, M.M.; Tanimu, A.; Alhooshani, K.; Ganiyu, S.A. Advances in Catalytic Dry Reforming of Methane (DRM): Emerging Trends, Current Challenges, and Future Perspectives. J Clean Prod 2023, 423, 138638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Gao, Y.; Mao, Y.; Wang, W.; Sun, J.; Song, Z.; Sun, J.; Zhao, X. Enhanced Dry Reforming of Methane by Microwave-Mediated Confined Catalysis over Ni-La/AC Catalyst. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 451, 138616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Peng, Y.; Gu, H.; Zhang, S.; Wang, F.R.; Xiao, W.; Yu, H.; Gu, D. Enhanced Dry Reforming of Methane over Nickel Catalysts Supported on Zirconia Coated Mesoporous Silica. iScience 2025, 28, 112582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Ma, Y.-Y.; Mo, W.-L.; Guo, J.; Liu, Q.; Fan, X.; Zhang, S.-P. Research Progress of Carbon Deposition on Ni-Based Catalyst for CO2-CH4 Reforming. Catalysts 2023, 13, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Z.; Das, S.; Wai, M.H.; Hongmanorom, P.; Kawi, S. A Review on Bimetallic Nickel-Based Catalysts for CO2 Reforming of Methane. ChemPhysChem 2017, 18, 3117–3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussien, A.G.S.; Polychronopoulou, K. A Review on the Different Aspects and Challenges of the Dry Reforming of Methane (DRM) Reaction. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchida, R.; Kurokawa, H.; Yamamoto, T.; Ogihara, H. Dry Reforming of Methane on Low-Loading Rh Catalysts. ChemCatChem 2025, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, C.; Dong, Y.; Zhu, Y. Metal-Support Interaction for Heterogeneous Catalysis: From Nanoparticles to Single Atoms. Mater Today Nano 2020, 12, 100093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, N.; Zha, Y.; Zheng, K.; Xu, Y.; Liu, B.; Liu, X. Strong Activity-Based Volcano-Type Relationship for Dry Reforming of Methane through Modulating Ni-CeO2 Interaction over Ni/CeO2-SiO2 Catalysts. Chem Catalysis 2025, 5, 101189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Song, H.; Zhang, L.; Wu, Y.; He, Y.; Ma, L.; Hong, J.; Tayal, A.; Marinkovic, N.; et al. Tuning Metal-Support Interactions in Nickel–Zeolite Catalysts Leads to Enhanced Stability during Dry Reforming of Methane. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 8566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SUN, K.; JIANG, J.; LIU, Z.; GENG, S.; LIU, Z.; YANG, J.; LI, S. Research Progress on Metal-Support Interactions over Ni-Based Catalysts for CH4-CO2 Reforming Reaction. Journal of Fuel Chemistry and Technology 2025, 53, 434–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Xia, P.; Zhang, Q.; Guo, F.; Xia, Y.; Tian, H. Coke Resistance of Ni-Based Catalysts Enhanced by Cold Plasma Treatment for CH4–CO2 Reforming: Review. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 23174–23189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Leng, J.; Yan, H.; Zhang, D.; Ren, D.; Li, F.; Liu, Y.; Chen, X.; Yang, C. Enhanced Activity and Stability for Combined Steam and CO2 Reforming of Methane over NiLa/MgAl2O4 Catalyst. Appl Surf Sci 2023, 638, 158059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Coster, V.; Srinath, N.V.; Theofanidis, S.A.; Pirro, L.; Van Alboom, A.; Poelman, H.; Sabbe, M.K.; Marin, G.B.; Galvita, V. V. Looking inside a Ni-Fe/MgAl2O4 Catalyst for Methane Dry Reforming via Mössbauer Spectroscopy and in Situ QXAS. Appl Catal B 2022, 300, 120720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; Bing, W.; Xu, M.; Li, Y.; Yang, Y.; Cui, G.; Yang, L.; Wei, M. Acid–Base Sites Synergistic Catalysis over Mg–Zr–Al Mixed Metal Oxide toward Synthesis of Diethyl Carbonate†. RSC Adv 2018, 8, 4695–4702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinho, A.L.A.; Toniolo, F.S.; Noronha, F.B.; Epron, F.; Duprez, D.; Bion, N. Highly Active and Stable Ni Dispersed on Mesoporous CeO2-Al2O3 Catalysts for Production of Syngas by Dry Reforming of Methane. Appl Catal B 2021, 281, 119459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Wang, Z.; Tang, L.; Jiang, S.; Guo, Y.; Liu, X. Support Effect in Ni-Based Catalysts for Methane Steam Reforming: Role of MxOy-Al2O3 (M = Ni, Mg, Co) Supports for Enhanced Catalyst Stability. Fuel Processing Technology 2025, 278, 108325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tungkamani, S.; Ratana, T.; Jadsadajerm, S.; Sumarasingha, W.; Phongaksorn, M. Enhancement of CO2 Adsorption and Oxygen Transfer Properties on γ-Al2O3 Support through Surface Modification with MgO-ZrO2 for Coke Suppression over Ni Catalyst in CO2 Reforming of Methane. Results in Engineering 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.X.; Wang, L.; Wu, C.F.; Wang, J.Q.; Shen, B.X.; Tu, X. Low Temperature Reforming of Biogas over K-, Mg- and Ce-Promoted Ni/Al2O3 Catalysts for the Production of Hydrogen Rich Syngas: Understanding the Plasma-Catalytic Synergy. Appl Catal B 2018, 224, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Chen, G.; Wang, J.; Zhou, R.; Sun, Y.; Weidenkaff, A.; Shen, B.; Tu, X. Plasma-Catalytic Biogas Reforming for Hydrogen Production over K-Promoted Ni/Al2O3 Catalysts: Effect of K-Loading. Journal of the Energy Institute 2022, 104, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjadi, S.M.; Haghighi, M.; Fard, S.G.; Eshghi, J. Various Calcium Loading and Plasma-Treatment Leading to Controlled Surface Segregation of High Coke-Resistant Ca-Promoted NiCo–NiAl2O4 Nanocatalysts Employed in CH4/CO2/O2 Reforming to H2. Int J Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 24708–24727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumarasingha, W.; Supasitmongkol, S.; Phongaksorn, M. The Effect of ZrO2 as Different Components of Ni-Based Catalysts for CO2 Reforming of Methane and Combined Steam and CO2 Reforming of Methane on Catalytic Performance with Coke Formation. Catalysts 2021, 11, 984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmasaroja, N.; Ratana, T.; Tungkamani, S.; Sornchamni, T.; Simakov, D.S.A.; Phongaksorn, M. The Effects of CeO2 and Co Doping on the Properties and the Performance of the Ni/Al2O3-MgO Catalyst for the Combined Steam and CO2 Reforming of Methane Using Ultra-Low Steam to Carbon Ratio. Catalysts 2020, 10, 1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan Özcan, M.; Akın, A.N. Sustainable Syngas Production by Oxy-Steam Reforming of Simulated Biogas over NiCe/MgAl Hydrotalcite-Derived Catalysts: Role of Support Preparation Methods on Activity. Sustain Chem Pharm 2023, 35, 101165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tungkamani, S.; Intarasiri, S.; Sumarasingha, W.; Ratana, T.; Phongaksorn, M. Enhancement of Ni-NiO-CeO2 Interaction on Ni-CeO2/Al2O3-MgO Catalyst by Ammonia Vapor Diffusion Impregnation for CO2 Reforming of CH4. Molecules 2024, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmasaroja, N.; Ratana, T.; Tungkamani, S.; Sornchamni, T.; Simakov, D.S.A.; Phongaksorn, M. CO2 Reforming of Methane over the Growth of Hierarchical Ni Nanosheets/Al2O3-MgO Synthesized via the Ammonia Vapour Diffusion Impregnation. Canadian Journal of Chemical Engineering 2021, 99, S585–S595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, H.; Noh, W.Y.; Kim, E.H.; Ra, E.C.; Kim, S.K.; An, K.; Lee, J.S. Layered Double Hydroxide-Derived Intermetallic Ni3GaC0.25Catalysts for Dry Reforming of Methane. ACS Catal 2021, 11, 11091–11102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumarasingha, W.; Tungkamani, S.; Ratana, T.; Supasitmongkol, S.; Phongaksorn, M. Combined Steam and CO2 Reforming of Methane over the Hierarchical Ni-ZrO2 Nanosheets/Al2O3 Catalysts at Ultralow Temperature and under Low Steam. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 46425–46437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratana, T.; Jadsadajerm, S.; Tungkamani, S.; Sumarasingha, W.; Phongaksorn, M. Effect of Modified Surface of Co/Al2O3 on Properties and Catalytic Performance for CO2 Reforming of Methane. Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids 2024, 191 . [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroarena, I.; Grande, L.; Torrez-Herera, J.J.; Korili, S.A.; Gil, A. Analysis by Temperature-Programmed Reduction of the Catalytic System Ni-Mo-Pd/Al2O3. Fuel 2023, 334 . [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, X.; Xu, Y.; Li, Y.; Yan, W.; Wang, Q.; Liang, X. Preparation of Closed-Pore MgO-MgFe2O4 Aggregates with Low Thermal Conductivity and High Mechanical Properties. J Eur Ceram Soc 2023, 43, 7178–7188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beletskii, E.; Pinchuk, M.; Snetov, V.; Dyachenko, A.; Volkov, A.; Savelev, E.; Romanovski, V. Simple Solution Plasma Synthesis of Ni@NiO as High-Performance Anode Material for Lithium-Ion Batteries Application. Chempluschem 2024, 89 . [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- High, M.; Patzschke, C.F.; Zheng, L.; Zeng, D.; Gavalda-Diaz, O.; Ding, N.; Chien, K.H.H.; Zhang, Z.; Wilson, G.E.; Berenov, A. V.; et al. Precursor Engineering of Hydrotalcite-Derived Redox Sorbents for Reversible and Stable Thermochemical Oxygen Storage. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 5109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Ghani, N.A.; Azapour, A.; Syed Muhammad, S.A.F.; Mohamed Ramli, N.; Vo, D.-V.N.; Abdullah, B. Dry Reforming of Methane for Syngas Production over Ni–Co-Supported Al2O3–MgO Catalysts. Appl Petrochem Res 2018, 8, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Shi, L.; Jin, C.; Ye, R.; Zhang, R. Co and Ni Incorporated γ-Al2O3 (110) Surface: A Density Functional Theory Study. Catalysts 2022, 12, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, J.R.; Boldrin, P.; Combes, G.B.; Ozkaya, D.; Enache, D.I.; Ellis, P.R.; Kelly, G.; Claridge, J.B.; Rosseinsky, M.J. The Effect of Mg Location on Co-Mg-Ru/γ-Al2O3 Fischer–Tropsch Catalysts. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2016, 374, 20150087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Jiang, X.; Pan, M.; Shi, Y. Nano-Scale Pore Structure and Its Multi-Fractal Characteristics of Tight Sandstone by N2 Adsorption/Desorption Analyses: A Case Study of Shihezi Formation from the Sulige Gas Filed, Ordos Basin, China. Minerals 2020, 10, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghampson, I.T.; Newman, C.; Kong, L.; Pier, E.; Hurley, K.D.; Pollock, R.A.; Walsh, B.R.; Goundie, B.; Wright, J.; Wheeler, M.C.; et al. Effects of Pore Diameter on Particle Size, Phase, and Turnover Frequency in Mesoporous Silica Supported Cobalt Fischer-Tropsch Catalysts. Appl Catal A Gen 2010, 388, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Shen, C.; Sun, K.; Liu, C.J. Improvement in the Activity of Ni/In2O3 with the Addition of ZrO2 for CO2 Hydrogenation to Methanol. Catal Commun 2022, 162 . [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khani, Y.; Pyo, S.; Bahadoran, F.; Cho, K.; Jeong, K.E.; Park, Y.K. Synthesis of Coke-Resistant Catalyst Using NiAl2O4 Support for Hydrogen Production via Autothermal Dry Reforming of Methane. ChemCatChem 2025, 17 . [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Ren, Y.; Yue, B.; Tsang, S.C.E.; He, H. Tuning Metal–Support Interactions on Ni/Al2O3 Catalysts to Improve Catalytic Activity and Stability for Dry Reforming of Methane. Processes 2021, 9, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewbank, J.L.; Kovarik, L.; Diallo, F.Z.; Sievers, C. Effect of Metal–Support Interactions in Ni/Al2O3 Catalysts with Low Metal Loading for Methane Dry Reforming. Appl Catal A Gen 2015, 494, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Li, Y.; Shi, R.; Yang, M. Effect of Metal–Support Interaction on the Catalytic Performance of Ni/Al2O3 for Selective Hydrogenation of Isoprene. J Mol Catal A Chem 2011, 344, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, J.; Duan, H.; Sun, T.; Zhi, Z.; Li, D.; Fan, X.; Zhang, L.; Yang, D. Amorphous/Crystalline ZrO2 with Oxygen Vacancies Anchored Nano-Ru Enhance Reverse Hydrogen Spillover in Alkaline Hydrogen Evolution. Small 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Liang, J.; Jiang, L.; Huang, W. Effects of Oxygen Vacancies on Hydrogenation Efficiency by Spillover in Catalysts. Chem Sci 2025, 16, 3408–3429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, B.; Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Liang, X. Engineering Metal-Oxide Interface by Depositing ZrO2 Overcoating on Ni/Al2O3 for Dry Reforming of Methane. Chemical Engineering Journal 2022, 436, 135195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhao, J.; Wu, T.; Zhao, M.; Yan, W.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, T.; Zhao, Y. Synergistic Effect of Oxygen Vacancies and Ni Species on Tuning Selectivity of Ni/ZrO2 Catalyst for Hydrogenation of Maleic Anhydride into Succinic Anhydride and γ-Butyrolacetone. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Q.; Ma, M.; Duan, Z.; Yan, H.; Liu, X. Synergistic Effect of Oxygen Vacancies and Ni0 Species on the Full Hydrogenation of 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural to Non-Furanic Cyclic Diol. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 2025, 13, 13297–13308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.; Xu, L.; Chen, M.; Cui, Y.; Wen, X.; Li, Y.; Wu, C.; Yang, B.; Miao, Z.; Hu, X.; et al. Recent Progresses in Constructing the Highly Efficient Ni Based Catalysts With Advanced Low-Temperature Activity Toward CO2 Methanation. Front Chem 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Kayode, G.O.; Hirayama, Y.; Shpasser, D.; Ogino, I.; Montemore, M.M.; Gazit, O.M. Enhanced Dry Reforming of Methane Catalysis by Ni at Heterointerfaces between Thin MgAlOx and Bulk ZrO2. ChemCatChem 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piyapaka, K.; Tungkamani, S.; Phongaksorn, M. Effect of Strong Metal Support Interactions of Supported Ni and Ni-Co Catalyst on Metal Dispersion and Catalytic Activity toward Dry Methane Reforming Reaction. King Mongkut’s University of Technology North Bangkok International Journal of Applied Science and Technology 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Lei, Y.; Wan, G.; Mei, Z.; Yu, J.; Zhao, Y.; He, S.; Luo, Y. Weakening the Metal-Support Strong Interaction to Enhance Catalytic Performances of Alumina Supported Ni-Based Catalysts for Producing Hydrogen. Appl Catal B 2020, 263, 118177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dębek, R.; Motak, M.; Galvez, M.E.; Grzybek, T.; Da Costa, P. Promotion Effect of Zirconia on Mg(Ni,Al)O Mixed Oxides Derived from Hydrotalcites in CO2 Methane Reforming. Appl Catal B 2018, 223, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Tsubaki, N.; Tan, Y.; Han, Y. Influence of Zirconia Phase on the Performance of Ni/ZrO2 for Carbon Dioxide Reforming of Methane; 2015; pp. 135–153. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Song, Y.; Li, D.; Xie, Z.; Ren, Y.; Kong, L.; Fan, X.; Xiao, X.; Li, J.; Zhao, Z. Strong NiOx and ZrO2 Interactions to Eliminate the Inhibiting Effect of Trace Oxygen for Propane Dehydrogenation by Accelerating Lattice Oxygen Releasing. Appl Catal A Gen 2023, 661, 119246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phogat, P.; Shreya; Jha, R.; Singh, S. Design and Performance Evaluation of 2D Nickel Oxide Nanosheet Thin Film Electrodes in Energy Storage Devices. Indian Journal of Physics 2025, 99, 1679–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

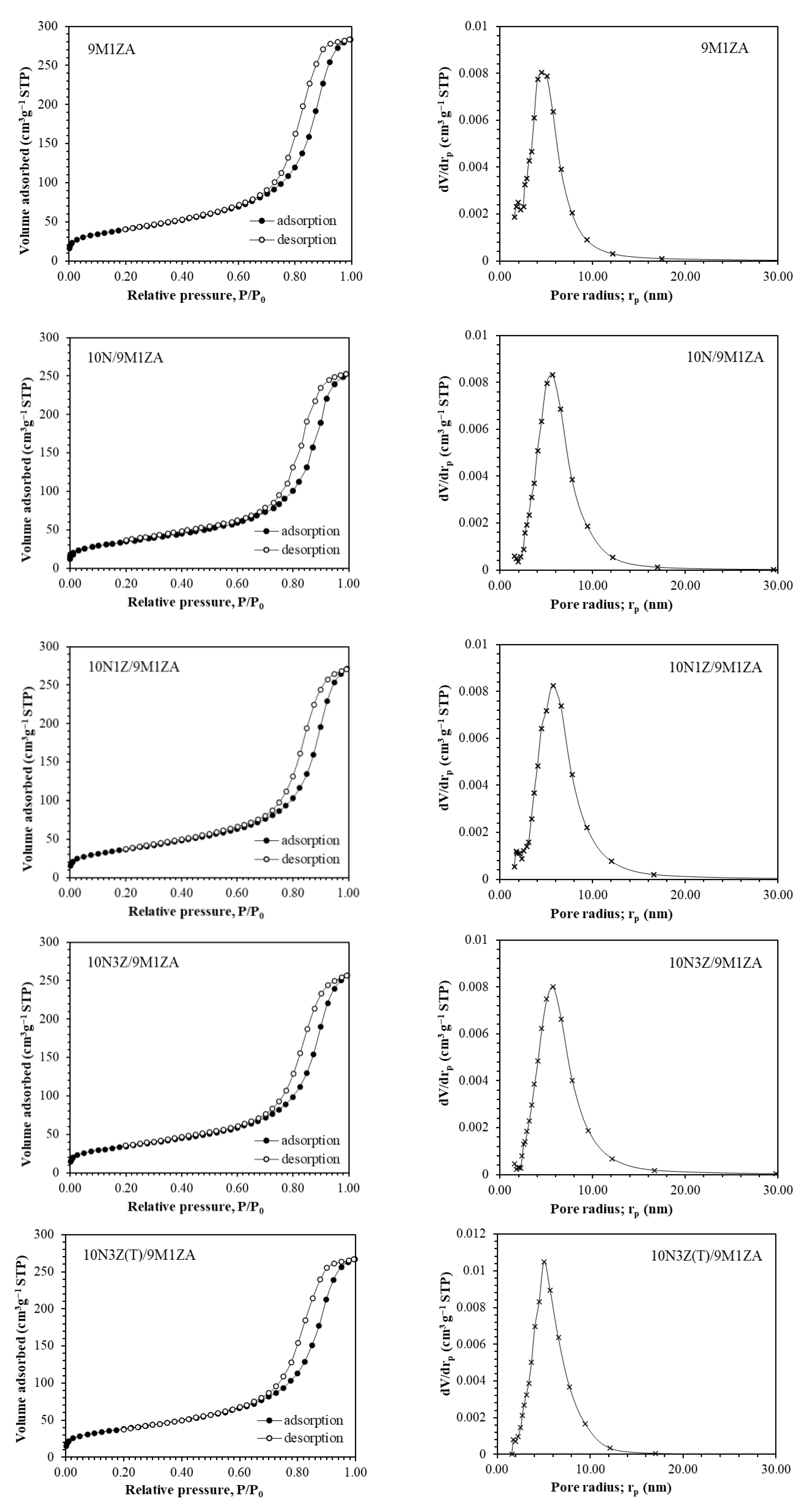

| Samples | Surface Areaa (m2·g−1) |

Average pore radiusa (nm) |

Pore volumea (cm3·g−1) |

Size of NiO crystallineb (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9M1ZA support | 145 | 6.06 | 0.44 | - |

| 10N/9M1ZA | 125 | 6.24 | 0.40 | 8.59 |

| 10N1Z/9M1ZA | 132 | 6.37 | 0.42 | 8.63 |

| 10N3Z/9M1ZA | 124 | 6.39 | 0.40 | 8.67 |

| 10N3Z(T)/9M1ZA | 137 | 6.04 | 0.41 | 9.71 |

| Catalysts | Mass concentration (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mg 1s | Ni 2p | O 1s | Al 2p | |

| 10N/9M1ZA | 1.34 | 7.89 | 49.52 | 41.25 |

| 10N1Z/9M1ZA | 1.67 | 6.54 | 50.87 | 40.92 |

| 10N3Z/9M1ZA | 1.90 | 5.25 | 52.05 | 40.79 |

| 10N3Z(T)/9M1ZA | 1.01 | 6.85 | 49.86 | 42.27 |

| Spent catalyst | Oxygen uptake in TPO (mmol/g) | Carbon deposition (%Dc) |

|---|---|---|

| 10N3Z/9M1ZA | 3.825 | 4.59 |

| 10N3Z(T)/9M1ZA | 6.747 | 8.09 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).