1. Introduction

Hepatocytolytic syndrome represents a pathological process with a wide etiological spectrum, including viral infections, autoimmune diseases, or intoxications. The clinician must identify the underlying cause using both anamnestic data and available paraclinical investigations. In certain clinical situations, the etiology of the hepatocytolytic syndrome remains elusive despite the use of standard diagnostic algorithms and advanced paraclinical workups. In such cases, the evaluation must be expanded through an exhaustive anamnesis, focusing on discrete but potentially relevant factors, such as self-medication, chronic consumption of phytotherapeutic supplements, or exposure to substances with hepatotoxic potential, which may constitute possible causes of liver injury [

1,

2,

3]. Drug-Induced Liver Injury (DILI) is a pathological entity characterized by liver damage mediated by xenobiotic compounds of a medicinal type, occurring in the context of pharmacological exposure and in the absence of any other identifiable alternative etiology [

2,

3]. It is classified into predictable forms, with a toxic-metabolic mechanism that is dose-dependent, and idiosyncratic forms, which are dose-independent and have an immunological or genetic substrate [

2,

3]. Herbal-Induced Liver Injury (HILI) represents a subcategory of DILI, in which the liver pathology is associated with the use of plant-based products [

1,

2]. The interest in alternative therapies based on natural remedies, involving the use of herbal extracts or medicinal plants with high accessibility and widespread presence in popular culture, is a frequently encountered practice among the general population [

1]. These are often administered either by virtue of empirically transmitted ethnomedical traditions or as a result of recommendations from non-specialized sources, particularly from the online environment [

1].

2. Case Presentation

In April 2024, patient S.L., a 55-year-old female with no documented prior liver disease, was admitted to the 1st- Department of Internal Medicine of the Clinical County Emergency Hospital Bihor, presenting with a constitutional syndrome of progressive onset over approximately three months, characterized by asthenia and fatigability, anorexia, mixed dyspeptic abdominal discomfort, and unintentional weight loss of approximately 12 kg, with symptom exacerbation in the days immediately preceding admission. Physical examination revealed an overweight nutritional status (BMI 28.03 kg/m²), height 170 cm, and weight 81 kg. Personal physiological and pathological history included two caesarean deliveries, menopause onset at age 46, and essential arterial hypertension on combined antihypertensive therapy (Perindopril/Indapamide/Amlodipine 5 mg/1.25 mg/5 mg, 1 tablet/day, and Bisoprolol 2.5 mg/day). From a socio-occupational perspective, the patient is employed as auxiliary cleaning and sanitation staff, without direct occupational exposure to potentially hepatotoxic agents. She resides in an urban environment (Oradea) with adequate living conditions. Anamnestic, the patient reports occasional coffee consumption and denies alcohol intake (religiously motivated). However, she reports sustained and regular ingestion over the past month, for presumed therapeutic purposes, of infusions prepared from bay leaves (Laurus nobilis), initiated based on recommendations accessed online. At admission, laboratory findings showed a hepatocytolytic syndrome (AST = 196 U/L / ALT = 261 U/L), dyslipidemia (LDL-cholesterol = 120.24 mg/dL, HDL-cholesterol = 39 mg/dL), and impaired fasting glucose level (119 mg/dL). (

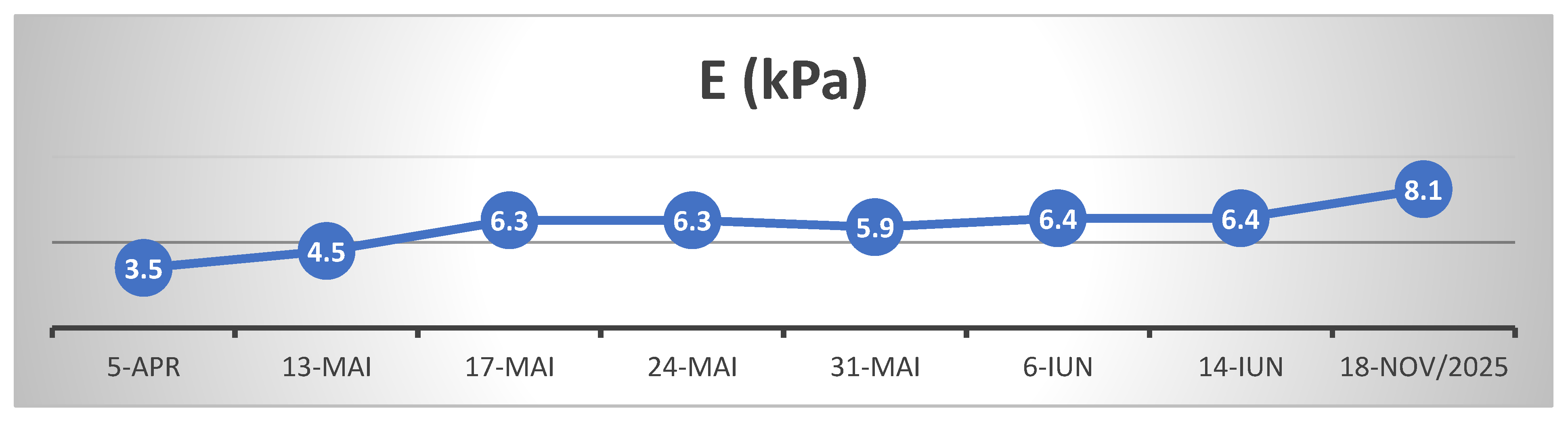

Table 1.) Abdominal ultrasound revealed steatosis grade II aspect and abdominopelvic CT revealed, mesenteric panniculitis accompanied by inflammatory-appearing lymphadenopathy. Transient elastography (FibroScan) showed the following values: CAP = 265 dB/m– steatosis grade S0 (Cut off value S0/S1 = 288 dB/m), fibrosis - E = 3.5 kPa equivalent to Metavir F0/F1. To exclude possible viral hepatocytolysis, serology for hepatitis A (IgM VHA), B (HBsAg and total anti-HBc IgG+IgM), C (Ac HCV), and E (IgM + IgG VHE) viruses was performed, with negative results. Serology also excluded possible hepatitis due to Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus. An autoimmune hepatopathy was considered; thus an autoimmune hepatitis panel was performed with: anti-mitochondrial M2 antibodies (AMA-M2) and anti-M2-3E were assayed to rule out primary biliary cholangitis (results within normal limits), antinuclear antibodies (ANA) to exclude autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) type 1, anti-liver-kidney microsomal type 1 antibodies (LKM-1) and anti-liver cytosol type 1 (anti-LC1) for differential diagnosis with AIH type 2, and anti-soluble liver antigen/liver-pancreas (anti-SLA/LP) for AIH type 3, as well as other antibodies specific to autoimmune liver diseases (anti-sp100, anti-PML, anti-gp210, anti-Ro-52), all of which were negative. To exclude hereditary liver disease, ceruloplasmin (Wilson’s disease) and alpha-1 antitrypsin levels were measured, with results within normal limits.

During hospitalization, the patient received hepatoprotective therapy consisting of silymarin, essential phospholipids and amino-acids, and L-arginine, alongside solutions for metabolic support and hydro-electrolytic rebalancing. Initial favorable clinical evolution allowed discharge; however, the patient re-presented to the hospital a few days post-discharge due to symptom recurrence. To establish the etiopathogenesis of the hepatocitolytic syndrome, a liver biopsy was performed. Histology described mild-to-moderate portal tract expansion with lymphoplasmocytic inflammation, preserved portal triad without pathological fibrosis and without interface hepatitis. Numerous apoptotic hepatocytes and focal confluent necrosis were noted, but without bridging necrosis. No histological signs of cholestasis or steatosis were identified. The overall picture was that of moderate-to-severe portal and lobular hepatitis without specific features; therefore, a possible herb-induced liver injury (HILI) could not be excluded.

(Figure 1 and

Figure 2.)

„The biopsy core measures 14 mm in length and, on histological sections, is thin but adequate, showing preserved lobular architecture of the hepatic parenchyma. Two portal tracts and seven centrilobular veins are identified. The portal tracts are mildly to moderately expanded with lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate; the portal triad is preserved, without pathological fibrosis and without interface hepatitis. Within the lobules, there is hepatocellular ballooning (dystrophic change), numerous apoptotic hepatocytes, focal and confluent necrosis without bridging necrosis; frequent typical mitoses and regenerative hepatocellular rosettes are also noted. There is no histological evidence of cholestasis or pathological steatosis.” Histopathological interpretation corresponding to

Figure 1 and

Figure 2.

For follow-up of disease progression, the patient was monitored by transient elastography (FibroScan) and serial hepatic biochemical profiling (transaminases and GGT)

(Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4)

The patient's clinical and biological evolution was slowly favorable following the discontinuation of bay leaf infusions, the patient remaining under ongoing medical follow-up. After cessation of exposure to the hepatotoxic agent and initiation of appropriate hepatoprotective therapy, the hepatocytolytic syndrome evolved favorably; however, hepatic fibrosis continued to progress, most likely as a consequence of extensive and prolonged hepatic necrosis. Close follow-up at 6-month intervals is warranted, given the rapid progression of post-HILI fibrosis observed over 17 months since the penultimate FibroScan assessment. We assume that the initially elevated liver stiffness reflected hepatic necrosis and inflammation, whereas the subsequent increase in fibrosis from June 2024 to November 2025 is attributable to ongoing fibrotic matrix progression following HILI.

3. Discussion

Laurus nobilis and its extracts have been the subject of numerous medical and pharmaceutical studies. Its leaves contain various alkaloids, tannins, and flavonoids, with well-documented antimicrobial and antioxidant effects, but also recognized hepatotoxic potential within the spectrum of herb-induced liver injury (HILI). Hepatotoxicity remains the primary adverse effect of many herbal products, and the diagnosis of HILI is often challenging because traditional diagnostic methods cannot precisely establish causality between the phytochemical agent and the hepato-cytolytic syndrome. Bay laurel (Laurus nobilis) is a shrub from the Lauraceae family, commonly cultivated for ornamental purposes, with leaves widely used in gastronomy for their aromatic properties. The essential oil content in Laurus nobilis leaves ranges from 1% to 3%, depending on geographic origin and harvest period, and contains sesquiterpene lactones, with predominant compounds being 1,8-cineole (eucalyptol), α-pinene, β-pinene, α-terpinyl acetate, sabinen, linalool, and, in relatively low concentrations of eugenol and

methyl-eugenol [

4]. Among these, methyl-eugenol is considered the primary potentially hepatotoxic agent [

5]. This aromatic compound (methyl-eugenol) undergoes hepatic metabolism via cytochrome P450 enzymes, yielding reactive intermediates such as 1′-hydroxymethyleugenol, which is genotoxic: it forms DNA adducts, induces oxidative stress, and triggers mitochondrial dysfunction, leading to cell necrosis and apoptosis via a p53-dependent pathway [

6]. Notably, methyleugenol has been classified by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) as possibly carcinogenic to humans (Group 2B) based on preclinical studies demonstrating the development of hepatic neoplasms in rodents chronically exposed to high doses [

7]. Eugenol, another constituent of bay leaf essential oils, is also recognized as a potential hepatotoxic agent. Acute eugenol overdose can result in severe liver injury characterized by acute hepatic necrosis, a clinical pattern closely resembling the hepatotoxicity induced by acetaminophen. [

8,

9]

In the context of this clinical case, application of the RUCAM (Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method) score yielded 8 points, indicating a probable causal relationship between repeated and sustained exposure to the suspected hepatotoxic agent and the observed liver injury. [

10]

Based on the histopathologic description, the differential diagnosis appropriately excluded several entities like alcoholic liver disease, which typically shows steatohepatitis with Mallory–Denk bodies, canalicular cholestasis, and characteristic “chicken-wire” perisinusoidal fibrosis [

11], the metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD/NAFLD/NASH), characterized by macrovesicular steatosis, hepatocyte ballooning, lobular inflammation, and perisinusoidal/portal fibrosis [

12] and autoimmune hepatitis, in which interface hepatitis (piecemeal necrosis) and/or dense portal lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate with periportal extension would be expected [

13]. Thus, in the absence of specific histologic features and after exclusion of other common etiologies, herb-induced liver injury (HILI) secondary to chronic bay leaf infusion consumption remains the most plausible diagnosis.

Another noteworthy aspect is the idiosyncratic nature of the hepatotoxic reaction, given that the patient reported that other family members consumed the same Laurus nobilis leaf infusions without developing clinical signs suggestive of liver injury. This supports significant inter-individual variability in the metabolism and hepatic response to the bioactive compounds contained therein.

A similar case has been reported in the medical literature from Turkey, in which a woman consumed Laurus nobilis leaf infusions for approximately one month. Subsequently, she developed symptoms suggestive of acute liver failure, including progressive asthenia, jaundice, abdominal pain, and marked elevation of hepatocytolysis and cholestasis markers. Investigations confirmed acute liver failure; despite initiation of specific treatment and planning for liver transplantation, the patient’s condition rapidly deteriorated, and death occurred before the procedure could be performed. [

9]

At the last follow-up, 1 year and 7 months after the initial presentation (November 2025), hepatic evaluation by elastography and ultrasonography revealed a CAP of 253 dB/m (steatosis degree S0) and liver stiffness of 8.2 kPa, corresponding to Metavir stage F2. Despite clinically and biochemically stable status, these findings indicate a certain degree of hepatic fibrous matrix remodeling following the previous episode of intense hepatocitolysis.

4. Conclusions

Certain food-derived compounds that are common and readily accessible can, under specific individual conditions, act as potential toxic agents that are difficult to identify without a detailed history. Repeated administration in doses or concentrations exceeding usual culinary use may trigger idiosyncratic or directly toxic adverse reactions with significant clinical implications for liver function and overall health status.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S., M.-C. B., C.B., M.R.; S.-F. C-S; methodology, M. S, C.B., T.-M.B. and M.-C.B.; software M.S., S.-F.C.-S, and T.-M. B; validation M.-C.B., C.B., M.R., G.B., and T-.M.B; formal analysis, M.-C.B., S.-F. C.-S. C.B., and G.B.; investigation M.S., C.-M.B., C.B., G.B. and T.-M.B., ; resources M.-C.B., M.S., G.B., and C.B.; data curation, M.S. and C.-M.B; writing—original draft preparation, M.S., M.-C.B., G.B and C.B.; writing—review and editing, M.S., S.-F.C.-S., C.B., T.-M.B. and M.-C.B; visualization, C.-M.B, M.S.,C.B., G.B., M.R. and. S.-F. C.-S.; supervision, M.-C.B. , G.B. and C.B.; project administration M.S. and M.-C.B., and C.B.; funding acquisition, C.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by University of Oradea, Romania.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Oradea County Emergency Clinical Hospital, Romania (Approval nr. 38083 from 11th of December 2025), for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

The patient provided written informed consent for the publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank to University of Oradea for paying APC.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript

AIH – Autoimmune Hepatitis

ALT – Alanine Aminotransferase

AMA-M2 – Anti-Mitochondrial Antibodies M2

ANA – Antinuclear Antibodies

Anti-HBc – Antibodies to Hepatitis B Core Antigen

AST – Aspartate Aminotransferase

BMI – Body Mass Index

CAP – Controlled Attenuation Parameter

CT – Computed Tomography

DILI – Drug-Induced Liver Injury

DNA – Desoxyribonucleic acid

gp210 – Glycoprotein 210 autoantibody

HBsAg – Hepatitis B Surface Antigen

HCV – Hepatitis C Virus

HDL – High-Density Lipoprotein

HILI – Herbal-Induced Liver Injury

IARC – International Agency for Research on Cancer

IgG – Immunoglobulin G

IgM – Immunoglobulin M

LC1 – Liver Cytosol type 1 antibodies

LDL – Low-Density Lipoprotein

LKM-1 – Liver-Kidney Microsomal type 1 antibodies

MAFLD – Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease

NAFLD – Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

NASH – Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis

PML – Promyelocytic Leukemia protein (autoantibody target)

RUCAM – Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method

SLA/LP – Soluble Liver Antigen/Liver Pancreas antibodies

VHA – Virus Hepatitis A

VHE – Virus Hepatitis E

References

- Ballotin, VR; Bigarella, LG; Brandão, ABM; Balbinot, RA; Balbinot, SS; Soldera, J. Herb-induced liver injury: Systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Clin Cases 2021, 9(20), 5490–5513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontana, RJ; Liou, I; Reuben, A; Suzuki, A; Fiel, MI; Lee, W; Navarro, V. AASLD practice guidance on drug, herbal, and dietary supplement-induced liver injury. Hepatology 2023, 77(3), 1036–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Drug-induced liver injury. J Hepatol 2019. [CrossRef]

- Ilić, Z.S.; Stanojević, L.; Milenković, L.; Šunić, L.; Milenković, A.; Stanojević, J.; Cvetković, D. Chemical Profiling of Essential Oils from Main Culinary Plants—Bay (Laurus nobilis L.) and Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) from Montenegro. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury. Bay Leaf (Laurus nobilis), 2020. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK585114/.

- Gardner, I; Wakazono, H; Bergin, P; de Waziers, I; Beaune, P; Kenna, J G; Caldwell, J. Cytochrome P450 mediated bioactivation of methyleugenol to 1'-hydroxymethyleugenol in Fischer 344 rat and human liver microsomes. Carcinogenesis 1997, 18(Issue 9), Pages 1775–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Some Chemicals Present in Industrial and Consumer Products, Food and Drinking-water. In IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans; Metileugenol, 2013; Volume 101, pp. 407–443. [Google Scholar]

- LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012-. Eugenol (Clove Oil). 28 Oct 2019. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551727/.

- Karaosmanoğlu, N; Aydın, N; Çelik, B; et al. Herbal-Induced Liver Injury Due to Laurus nobilis (Bay Leaf) Consumption: A Case Report. Turkiye Klinikleri J Med Sci. 2022, 42(3), 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danan, G; Teschke, R. RUCAM in Drug and Herb Induced Liver Injury: The Update. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2016, 17(1), 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL). EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of alcohol-related liver disease. J Hepatol. 2018, 69(1), 154–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL); European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD); European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO). EASL–EASD–EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2016, 64(6), 1388–1402.

- Assis, DN; Czaja, AJ. Histologic features of autoimmune hepatitis. Clin Liver Dis. 2017, 21(3), 669–685. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).