Submitted:

15 December 2025

Posted:

16 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. The First, Long-Term, Human Colorectal Organoid Culture

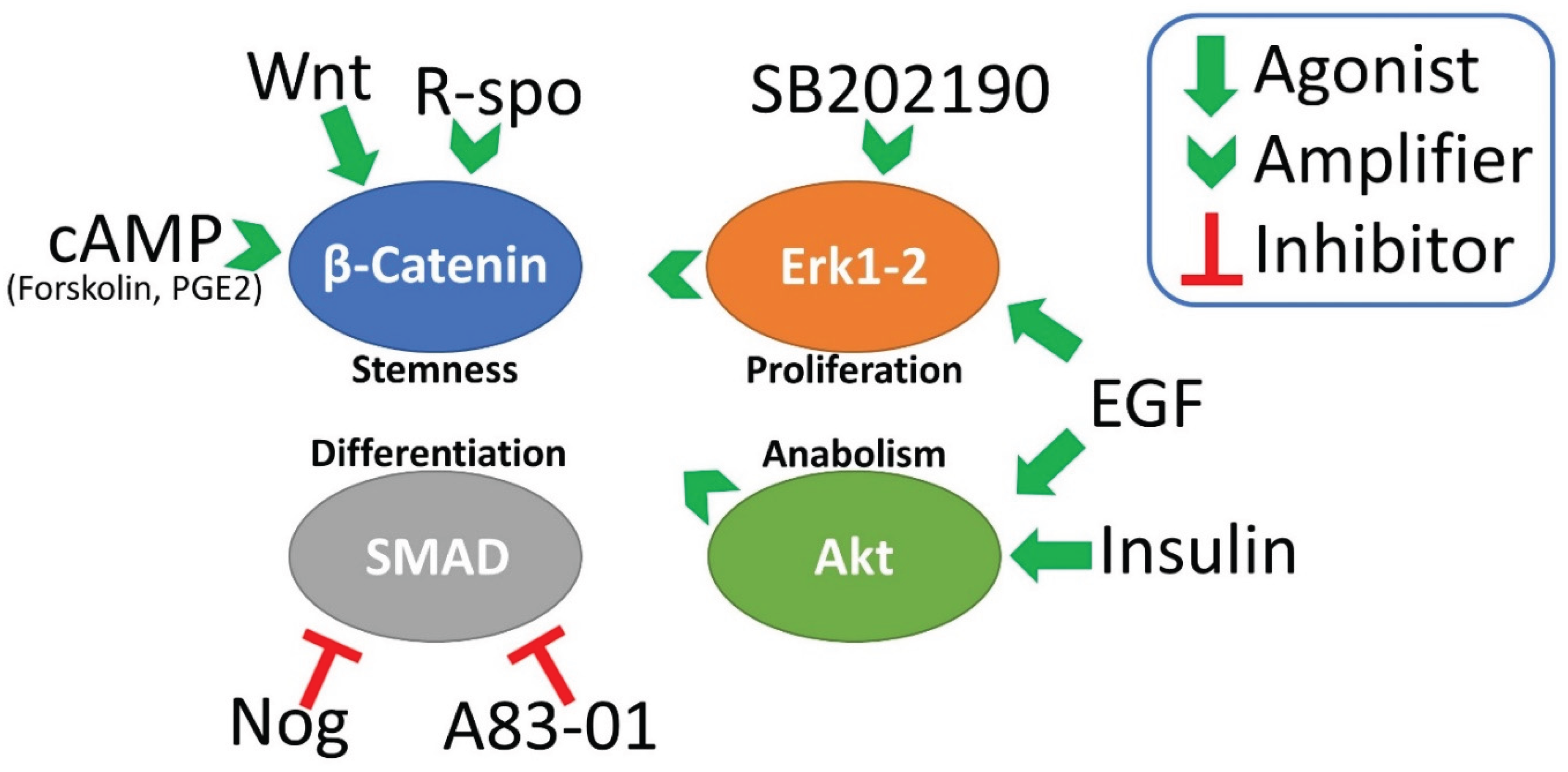

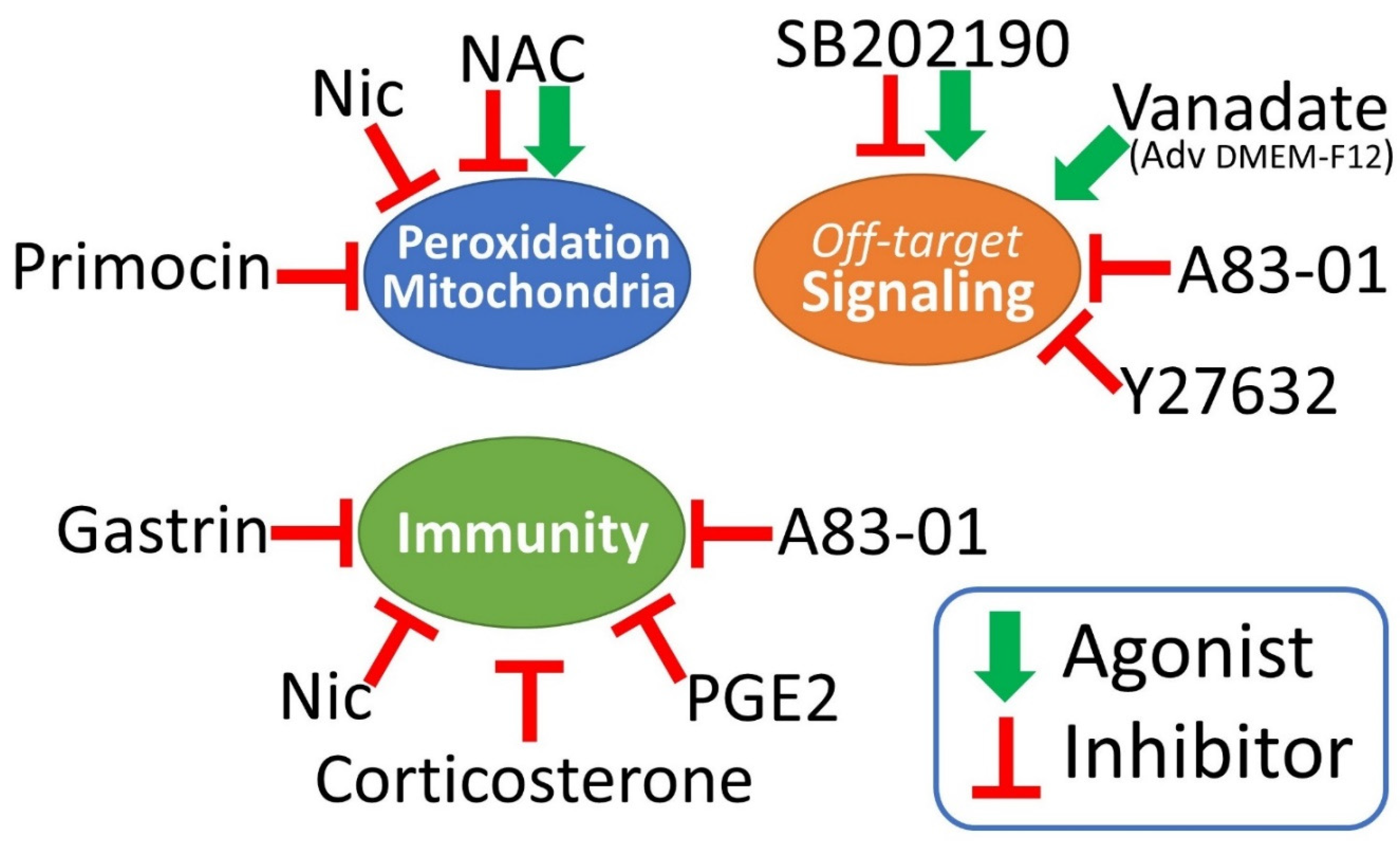

2. Signal Transduction Pathways Involved in Colorectal Organoids Propagation

3. Advanced DMEM-F12, B27 and N2

4. Primocin

5. Wnt3a, R-Spondin and Noggin

6. Nicotinamide

7. N-Acetyl Cysteine

8. A83-01

9. SB202190

10. EGF, Gastrin, PGE2, Y27632

11. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EGF | epithelial growth factor |

| NAC | n-acetylcysteine |

| Nic | nicotinamide |

| PGE2 | prostaglandin E2 |

References

- Sato, T.; Stange, D.E.; Ferrante, M.; Vries, R.G.J.; Van Es, J.H.; Van den Brink, S.; Van Houdt, W.J.; Pronk, A.; Van Gorp, J.; Siersema, P.D.; et al. Long-Term Expansion of Epithelial Organoids from Human Colon, Adenoma, Adenocarcinoma, and Barrett’s Epithelium. Gastroenterology 2011, 141, 1762–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmon, K.S.; Gong, X.; Lin, Q.; Thomas, A.; Liu, Q. R-Spondins Function as Ligands of the Orphan Receptors LGR4 and LGR5 to Regulate Wnt/Beta-Catenin Signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108, 11452–11457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, P.; Sato, T.; Merlos-Suárez, A.; Barriga, F.M.; Iglesias, M.; Rossell, D.; Auer, H.; Gallardo, M.; Blasco, M.A.; Sancho, E.; et al. Isolation and in Vitro Expansion of Human Colonic Stem Cells. Nat Med 2011, 17, 1225–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, A.; Wharton, N.; Parris, A.; Mitchell, E.; Sobolewski, A.; Kam, C.; Bigwood, L.; El Hadi, A.; Münsterberg, A.; Lewis, M.; et al. Canonical Wnt Signals Combined with Suppressed TGFβ/BMP Pathways Promote Renewal of the Native Human Colonic Epithelium. Gut 2014, 63, 610–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujii, M.; Matano, M.; Nanki, K.; Sato, T. Efficient Genetic Engineering of Human Intestinal Organoids Using Electroporation. Nat Protoc 2015, 10, 1474–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Wetering, M.; Francies, H.E.; Francis, J.M.; Bounova, G.; Iorio, F.; Pronk, A.; van Houdt, W.; van Gorp, J.; Taylor-Weiner, A.; Kester, L.; et al. Prospective Derivation of a Living Organoid Biobank of Colorectal Cancer Patients. Cell 2015, 161, 933–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, M.; Shimokawa, M.; Date, S.; Takano, A.; Matano, M.; Nanki, K.; Ohta, Y.; Toshimitsu, K.; Nakazato, Y.; Kawasaki, K.; et al. A Colorectal Tumor Organoid Library Demonstrates Progressive Loss of Niche Factor Requirements during Tumorigenesis. Cell Stem Cell 2016, 18, 827–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehnke, K.; Iversen, P.W.; Schumacher, D.; Lallena, M.J.; Haro, R.; Amat, J.; Haybaeck, J.; Liebs, S.; Lange, M.; Schäfer, R.; et al. Assay Establishment and Validation of a High-Throughput Screening Platform for Three-Dimensional Patient-Derived Colon Cancer Organoid Cultures. J Biomol Screen 2016, 21, 931–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verissimo, C.S.; Overmeer, R.M.; Ponsioen, B.; Drost, J.; Mertens, S.; Verlaan-Klink, I.; van Gerwen, B.; van der Ven, M.; de Wetering, M. van; Egan, D.A.; et al. Targeting Mutant RAS in Patient-Derived Colorectal Cancer Organoids by Combinatorial Drug Screening. eLife 2016, 5, e18489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimokawa, M.; Ohta, Y.; Nishikori, S.; Matano, M.; Takano, A.; Fujii, M.; Date, S.; Sugimoto, S.; Kanai, T.; Sato, T. Visualization and Targeting of LGR5+ Human Colon Cancer Stem Cells. Nature 2017, 545, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, M.; Matano, M.; Toshimitsu, K.; Takano, A.; Mikami, Y.; Nishikori, S.; Sugimoto, S.; Sato, T. Human Intestinal Organoids Maintain Self-Renewal Capacity and Cellular Diversity in Niche-Inspired Culture Condition. Cell Stem Cell 2018, 23, 787–793.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnalzger, T.E.; de Groot, M.H.; Zhang, C.; Mosa, M.H.; Michels, B.E.; Röder, J.; Darvishi, T.; Wels, W.S.; Farin, H.F. 3D Model for CAR-Mediated Cytotoxicity Using Patient-Derived Colorectal Cancer Organoids. EMBO J 2019, 38, e100928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Xu, X.; Yang, L.; Zhu, J.; Wan, J.; Shen, L.; Xia, F.; Fu, G.; Deng, Y.; Pan, M.; et al. Patient-Derived Organoids Predict Chemoradiation Responses of Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer. Cell Stem Cell 2020, 26, 17–26.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toshimitsu, K.; Takano, A.; Fujii, M.; Togasaki, K.; Matano, M.; Takahashi, S.; Kanai, T.; Sato, T. Organoid Screening Reveals Epigenetic Vulnerabilities in Human Colorectal Cancer. Nat Chem Biol 2022, 18, 605–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teijeira, A.; Migueliz, I.; Garasa, S.; Karanikas, V.; Luri, C.; Cirella, A.; Olivera, I.; Cañamero, M.; Alvarez, M.; Ochoa, M.C.; et al. Three-Dimensional Colon Cancer Organoids Model the Response to CEA-CD3 T-Cell Engagers. Theranostics 2022, 12, 1373–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohta, Y.; Fujii, M.; Takahashi, S.; Takano, A.; Nanki, K.; Matano, M.; Hanyu, H.; Saito, M.; Shimokawa, M.; Nishikori, S.; et al. Cell–Matrix Interface Regulates Dormancy in Human Colon Cancer Stem Cells. Nature 2022, 608, 784–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Mao, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhou, X.; Wang, W.; Gao, S.; Li, J.; Wen, L.; Fu, W.; Tang, F. Systematic Evaluation of Colorectal Cancer Organoid System by Single-Cell RNA-Seq Analysis. Genome Biol 2022, 23, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.S.; Mayo, M.; Melim, T.; Knight, H.; Patnaude, L.; Wu, X.; Phillips, L.; Westmoreland, S.; Dunstan, R.; Fiebiger, E.; et al. Optimized Culture Conditions for Improved Growth and Functional Differentiation of Mouse and Human Colon Organoids. Front. Immunol. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurayoshi, M.; Yamamoto, H.; Izumi, S.; Kikuchi, A. Post-Translational Palmitoylation and Glycosylation of Wnt-5a Are Necessary for Its Signalling. Biochem J 2007, 402, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, S.; Coudreuse, D.Y.M.; Van Der Westhuyzen, D.R.; Eckhardt, E.R.M.; Korswagen, H.C.; Schmitz, G.; Sprong, H. Mammalian Wnt3a Is Released on Lipoprotein Particles. Traffic 2009, 10, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihara, E.; Hirai, H.; Yamamoto, H.; Tamura-Kawakami, K.; Matano, M.; Kikuchi, A.; Sato, T.; Takagi, J. Active and Water-Soluble Form of Lipidated Wnt Protein Is Maintained by a Serum Glycoprotein Afamin/α-Albumin. eLife 2016, 5, e11621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamos, J.L.; Weis, W.I. The β-Catenin Destruction Complex. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2013, 5, a007898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colozza, G.; Koo, B.-K. Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling: Structure, Assembly and Endocytosis of the Signalosome. Development, Growth & Differentiation 2021, 63, 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagano, K. R-Spondin Signaling as a Pivotal Regulator of Tissue Development and Homeostasis. Japanese Dental Science Review 2019, 55, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuijers, J.; Junker, J.P.; Mokry, M.; Hatzis, P.; Koo, B.-K.; Sasselli, V.; van der Flier, L.G.; Cuppen, E.; van Oudenaarden, A.; Clevers, H. Ascl2 Acts as an R-Spondin/Wnt-Responsive Switch to Control Stemness in Intestinal Crypts. Cell Stem Cell 2015, 16, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, K.; Jadhav, U.; Madha, S.; van Es, J.; Dean, J.; Cavazza, A.; Wucherpfennig, K.; Michor, F.; Clevers, H.; Shivdasani, R.A. Ascl2-Dependent Cell Dedifferentiation Drives Regeneration of Ablated Intestinal Stem Cells. Cell Stem Cell 2020, 26, 377–390.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taurin, S.; Sandbo, N.; Qin, Y.; Browning, D.; Dulin, N.O. Phosphorylation of β-Catenin by Cyclic AMP-Dependent Protein Kinase*. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2006, 281, 9971–9976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, D.; Hawke, D.; Zheng, Y.; Xia, Y.; Meisenhelder, J.; Nika, H.; Mills, G.B.; Kobayashi, R.; Hunter, T.; Lu, Z. Phosphorylation of β-Catenin by AKT Promotes β-Catenin Transcriptional Activity*. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2007, 282, 11221–11229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosinski, C.; Li, V.S.W.; Chan, A.S.Y.; Zhang, J.; Ho, C.; Tsui, W.Y.; Chan, T.L.; Mifflin, R.C.; Powell, D.W.; Yuen, S.T.; et al. Gene Expression Patterns of Human Colon Tops and Basal Crypts and BMP Antagonists as Intestinal Stem Cell Niche Factors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2007, 104, 15418–15423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spit, M.; Koo, B.-K.; Maurice, M.M. Tales from the Crypt: Intestinal Niche Signals in Tissue Renewal, Plasticity and Cancer. Open Biology 2018, 8, 180120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuadrado, A.; Nebreda, A.R. Mechanisms and Functions of P38 MAPK Signalling. Biochem J 2010, 429, 403–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, M.; Kang, Y.J.; Ren, J.; Jiang, H.; Wang, Y.; Omata, M.; Han, J. Distinct Effects of P38α Deletion in Myeloid Lineage and Gut Epithelia in Mouse Models of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology 2010, 138, 1255–1265.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frey, M.R.; Dise, R.S.; Edelblum, K.L.; Polk, D.B. P38 Kinase Regulates Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Downregulation and Cellular Migration. The EMBO Journal 2006, 25, 5683–5692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, P.; Wang, Z. Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Cell Proliferation Signaling Pathways. Cancers 2017, 9, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, G.; Gao, N.; Chen, J.; Fan, L.; Zeng, Z.; Gao, G.; Li, L.; Fang, G.; Hu, K.; Pang, X.; et al. Erk and MAPK Signaling Is Essential for Intestinal Development through Wnt Pathway Modulation. Development 2020, 147, dev185678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, T.; Ambrosi, G.; Wandmacher, A.M.; Rauscher, B.; Betge, J.; Rindtorff, N.; Häussler, R.S.; Hinsenkamp, I.; Bamberg, L.; Hessling, B.; et al. MEK Inhibitors Activate Wnt Signalling and Induce Stem Cell Plasticity in Colorectal Cancer. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, P.R.; Taniguchi, K.; Harris, A.R.; Bertin, S.; Takahashi, N.; Duong, J.; Campos, A.D.; Powis, G.; Corr, M.; Karin, M.; et al. ERK5 Signalling Rescues Intestinal Epithelial Turnover and Tumour Cell Proliferation upon ERK1/2 Abrogation. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 11551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoxhaj, G.; Manning, B.D. The PI3K–AKT Network at the Interface of Oncogenic Signalling and Cancer Metabolism. Nat Rev Cancer 2020, 20, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurer, U.; Preiss, F.; Brauns-Schubert, P.; Schlicher, L.; Charvet, C. GSK-3 – at the Crossroads of Cell Death and Survival. J Cell Sci 2014, 127, 1369–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, H.; Lu, B.; Zamponi, R.; Yang, Z.; Wetzel, K.; Loureiro, J.; Mohammadi, S.; Beibel, M.; Bergling, S.; Reece-Hoyes, J.; et al. MTORC1 Signaling Suppresses Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling through DVL-Dependent Regulation of Wnt Receptor FZD Level. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018, 115, E10362–E10369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matozaki, T.; Kotani, T.; Murata, Y.; Saito, Y. Roles of Src Family Kinase, Ras, and MTOR Signaling in Intestinal Epithelial Homeostasis and Tumorigenesis. Cancer Science 2021, 112, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dou, Y.; Pizarro, T.; Zhou, L. Organoids as a Model System for Studying Notch Signaling in Intestinal Epithelial Homeostasis and Intestinal Cancer. The American Journal of Pathology 2022, 192, 1347–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, X.; Farin, H.F.; van Es, J.H.; Clevers, H.; Langer, R.; Karp, J.M. Niche-Independent High-Purity Cultures of Lgr5+ Intestinal Stem Cells and Their Progeny. Nat Methods 2014, 11, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.; Colarusso, J.L.; Dame, M.K.; Spence, J.R.; Zhou, Q. Rapid Establishment of Human Colonic Organoid Knockout Lines. STAR Protocols 2022, 3, 101308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezakhani, S.; Gjorevski, N.; Lutolf, M.P. Extracellular Matrix Requirements for Gastrointestinal Organoid Cultures. Biomaterials 2021, 276, 121020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, R.; Wouters, V.M.; van Neerven, S.M.; de Groot, N.E.; Garcia, T.M.; Muncan, V.; Franklin, O.D.; Battle, M.; Carlson, K.S.; Leach, J.; et al. The Extracellular Matrix Controls Stem Cell Specification and Crypt Morphology in the Developing and Adult Mouse Gut. Biol Open 2022, 11, bio059544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, F.A.; Prior, V.G.; Bax, S.; O’Neill, G.M. Forcing a Growth Factor Response – Tissue-Stiffness Modulation of Integrin Signaling and Crosstalk with Growth Factor Receptors. J Cell Sci 2020, 133, jcs242461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Gordillo, V.; Kassis, T.; Lampejo, A.; Choi, G.; Gamboa, M.E.; Gnecco, J.S.; Brown, A.; Breault, D.T.; Carrier, R.; Griffith, L.G. Fully Synthetic Matrices for in Vitro Culture of Primary Human Intestinal Enteroids and Endometrial Organoids. Biomaterials 2020, 254, 120125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergenheim, F.; Fregni, G.; Buchanan, C.F.; Riis, L.B.; Heulot, M.; Touati, J.; Seidelin, J.B.; Rizzi, S.C.; Nielsen, O.H. A Fully Defined 3D Matrix for Ex Vivo Expansion of Human Colonic Organoids from Biopsy Tissue. Biomaterials 2020, 262, 120248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, H.; Kempf, K.; Röhling, M.; Martin, S. Insulin: Too Much of a Good Thing Is Bad. BMC Med 2020, 18, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, V.W.; Chen, R.-H.; McCormick, F. Differential Regulation of Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3β by Insulin and Wnt Signaling*. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2000, 275, 32475–32481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxton, R.A.; Sabatini, D.M. MTOR Signaling in Growth, Metabolism, and Disease. Cell 2017, 168, 960–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galizzi, G.; Di Carlo, M. Insulin and Its Key Role for Mitochondrial Function/Dysfunction and Quality Control: A Shared Link between Dysmetabolism and Neurodegeneration. Biology 2022, 11, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Stockwell, B.R.; Conrad, M. Ferroptosis: Mechanisms, Biology and Role in Disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2021, 22, 266–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Schorpp, K.; Jin, J.; Yozwiak, C.E.; Hoffstrom, B.G.; Decker, A.M.; Rajbhandari, P.; Stokes, M.E.; Bender, H.G.; Csuka, J.M.; et al. Transferrin Receptor Is a Specific Ferroptosis Marker. Cell Reports 2020, 30, 3411–3423.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagana Gowda, G.A.; Pascua, V.; Raftery, D. Extending the Scope of 1H NMR-Based Blood Metabolomics for the Analysis of Labile Antioxidants: Reduced and Oxidized Glutathione. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 14844–14850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Li, C.; Liao, S.; Yao, X.; Ouyang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Yao, F. Ferritinophagy, a Form of Autophagic Ferroptosis: New Insights into Cancer Treatment. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, N.K.; Jain, C.; Sankar, A.; Schwartz, A.J.; Santana-Codina, N.; Solanki, S.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, X.; Parimi, S.; Rui, L.; et al. Modulation of the HIF2α-NCOA4 Axis in Enterocytes Attenuates Iron Loading in a Mouse Model of Hemochromatosis. Blood 2022, 139, 2547–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollara, A.; Brown, T.J. Expression and Function of Nuclear Receptor Co-Activator 4: Evidence of a Potential Role Independent of Co-Activator Activity. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2012, 69, 3895–3909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, K.; Hou, L.; Guo, Z.; Wang, G.; Guo, J.; Xu, J.; Zhang, X.; Guo, F. JNK-JUN-NCOA4 Axis Contributes to Chondrocyte Ferroptosis and Aggravates Osteoarthritis via Ferritinophagy. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2023, 200, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewin, M.H.; Arthur, J.R.; Riemersma, R.A.; Nicol, F.; Walker, S.W.; Millar, E.M.; Howie, A.F.; Beckett, G.J. Selenium Supplementation Acting through the Induction of Thioredoxin Reductase and Glutathione Peroxidase Protects the Human Endothelial Cell Line EAhy926 from Damage by Lipid Hydroperoxides. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research 2002, 1593, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolwijk, J.; Wagner, B.; McCormick, M.; Zakharia, Y.; Spitz, D.; Buettner, G. 290 - Optimization of Selenium in Cell Culture Media to Maximize Selenoenzyme Activity. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2018, 128, S121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, M.S.; Davis, R.L.; Walsh, L.P.; Pence, B.C. Induction of Differentiation and Apoptosis by Sodium Selenite in Human Colonic Carcinoma Cells (HT29). Cancer Letters 1997, 117, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selenius, M.; Fernandes, A.P.; Brodin, O.; Björnstedt, M.; Rundlöf, A.-K. Treatment of Lung Cancer Cells with Cytotoxic Levels of Sodium Selenite: Effects on the Thioredoxin System. Biochemical Pharmacology 2008, 75, 2092–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Z.; Yu, S.; He, W.; Li, J.; Xu, T.; Xue, J.; Shi, P.; Chen, S.; Li, Y.; Hong, S.; et al. Selenite Induces Cell Cycle Arrest and Apoptosis via Reactive Oxygen Species-Dependent Inhibition of the AKT/MTOR Pathway in Thyroid Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulley, P.; Davison, A. Regulation of Tyrosine Phosphorylation Cascades by Phosphatases: What the Actions of Vanadium Teach Us. The Journal of Trace Elements in Experimental Medicine 2003, 16, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levina, A.; Lay, P.A. Stabilities and Biological Activities of Vanadium Drugs: What Is the Nature of the Active Species? Chemistry – An Asian Journal 2017, 12, 1692–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanna, D.; Micera, G.; Garribba, E. Interaction of Insulin-Enhancing Vanadium Compounds with Human Serum Holo-Transferrin. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 11975–11985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crans, D.C. Antidiabetic, Chemical, and Physical Properties of Organic Vanadates as Presumed Transition-State Inhibitors for Phosphatases. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 11899–11915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klarlund, J.K. Transformation of Cells by an Inhibitor of Phosphatases Acting on Phosphotyrosine in Proteins. Cell 1985, 41, 707–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boersema, P.J.; Foong, L.Y.; Ding, V.M.Y.; Lemeer, S.; van Breukelen, B.; Philp, R.; Boekhorst, J.; Snel, B.; den Hertog, J.; Choo, A.B.H.; et al. In-Depth Qualitative and Quantitative Profiling of Tyrosine Phosphorylation Using a Combination of Phosphopeptide Immunoaffinity Purification and Stable Isotope Dimethyl Labeling. Mol Cell Proteomics 2010, 9, 84–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raubenheimer, P.J.; Young, E.A.; Andrew, R.; Seckl, J.R. The Role of Corticosterone in Human Hypothalamic– Pituitary–Adrenal Axis Feedback. Clinical Endocrinology 2006, 65, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Wang, B.; Ao, H. Corticosterone Effects Induced by Stress and Immunity and Inflammation: Mechanisms of Communication. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botrugno, O.A.; Fayard, E.; Annicotte, J.-S.; Haby, C.; Brennan, T.; Wendling, O.; Tanaka, T.; Kodama, T.; Thomas, W.; Auwerx, J.; et al. Synergy between LRH-1 and β-Catenin Induces G1 Cyclin-Mediated Cell Proliferation. Molecular Cell 2004, 15, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, M.; Cima, I.; Noti, M.; Fuhrer, A.; Jakob, S.; Dubuquoy, L.; Schoonjans, K.; Brunner, T. The Nuclear Receptor LRH-1 Critically Regulates Extra-Adrenal Glucocorticoid Synthesis in the Intestine. J Exp Med 2006, 203, 2057–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouguen, G.; Dubuquoy, L.; Desreumaux, P.; Brunner, T.; Bertin, B. Intestinal Steroidogenesis. Steroids 2015, 103, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidler, D.; Renzulli, P.; Schnoz, C.; Berger, B.; Schneider-Jakob, S.; Flück, C.; Inderbitzin, D.; Corazza, N.; Candinas, D.; Brunner, T. Colon Cancer Cells Produce Immunoregulatory Glucocorticoids. Oncogene 2011, 30, 2411–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogata, N.; Bland, P.; Tsang, M.; Oliemuller, E.; Lowe, A.; Howard, B.A. Sox9 Regulates Cell State and Activity of Embryonic Mouse Mammary Progenitor Cells. Commun Biol 2018, 1, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.; Mostoslavsky, G. Generation of Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Using a Defined, Feeder-Free Reprogramming System. Current Protocols in Stem Cell Biology 2018, 45, e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ryu, D.; Houtkooper, R.H.; Auwerx, J. Antibiotic Use and Abuse: A Threat to Mitochondria and Chloroplasts with Impact on Research, Health, and Environment. BioEssays 2015, 37, 1045–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Kang, H.T.; Hwang, E.S. Nicotinamide-Induced Mitophagy: EVENT MEDIATED BY HIGH NAD+/NADH RATIO AND SIRT1 PROTEIN ACTIVATION*. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2012, 287, 19304–19314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badal, S.; Her, Y.F.; Maher, L.J. Nonantibiotic Effects of Fluoroquinolones in Mammalian Cells *. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2015, 290, 22287–22297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.H.; Chiu, F.C.; Li, R.C. Mechanistic Investigation of the Reduction in Antimicrobial Activity of Ciprofloxacin by Metal Cations. Pharm Res 1997, 14, 366–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harmsen, S.; McLaren, A.C.; Pauken, C.; McLemore, R. Amphotericin B Is Cytotoxic at Locally Delivered Concentrations. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® 2011, 469, 3016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, J.E.; Massof, S.E. In Vivo Activation of Macrophage Oxidative Burst Activity by Cytokines and Amphotericin B. Infect Immun 1990, 58, 1296–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammarström, L.; Smith, E. Mitogenic Properties of Polyene Antibiotics for Murine B Cells. Scand J Immunol 1976, 5, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedges, J.F.; Mitchell, A.M.; Jones, K.; Kimmel, E.; Ramstead, A.G.; Snyder, D.T.; Jutila, M.A. Amphotericin B Stimulates Γδ T and NK Cells, and Enhances Protection from Salmonella Infection. Innate Immun 2015, 21, 598–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grela, E.; Piet, M.; Luchowski, R.; Grudzinski, W.; Paduch, R.; Gruszecki, W.I. Imaging of Human Cells Exposed to an Antifungal Antibiotic Amphotericin B Reveals the Mechanisms Associated with the Drug Toxicity and Cell Defence. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 14067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warrilow, A.G.; Parker, J.E.; Kelly, D.E.; Kelly, S.L. Azole Affinity of Sterol 14α-Demethylase (CYP51) Enzymes from Candida Albicans and Homo Sapiens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013, 57, 1352–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, R.; Niazi-Ali, S.; McIvor, A.; Kanj, S.S.; Maertens, J.; Bassetti, M.; Levine, D.; Groll, A.H.; Denning, D.W. Triazole Antifungal Drug Interactions—Practical Considerations for Excellent Prescribing. J Antimicrob Chemother 2024, 79, 1203–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.; Ha, A.; de Lau, W.; Yuki, K.; Santos, A.J.M.; You, C.; Geurts, M.H.; Puschhof, J.; Pleguezuelos-Manzano, C.; Peng, W.C.; et al. Next-Generation Surrogate Wnts Support Organoid Growth and Deconvolute Frizzled Pleiotropy In Vivo. Cell Stem Cell 2020, 27, 840–851.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avalos, J.L.; Bever, K.M.; Wolberger, C. Mechanism of Sirtuin Inhibition by Nicotinamide: Altering the NAD+ Cosubstrate Specificity of a Sir2 Enzyme. Molecular Cell 2005, 17, 855–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salech, F.; Ponce, D.P.; Paula-Lima, A.C.; SanMartin, C.D.; Behrens, M.I. Nicotinamide, a Poly [ADP-Ribose] Polymerase 1 (PARP-1) Inhibitor, as an Adjunctive Therapy for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.B.; Jang, S.-Y.; Kang, H.T.; Wei, B.; Jeoun, U.; Yoon, G.S.; Hwang, E.S. Modulation of Mitochondrial Membrane Potential and ROS Generation by Nicotinamide in a Manner Independent of SIRT1 and Mitophagy. Molecules and Cells 2017, 40, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Y.; Ren, Z.; Xu, F.; Zhou, X.; Song, C.; Wang, V.Y.-F.; Liu, W.; Lu, L.; Thomson, J.A.; Chen, G. Nicotinamide Promotes Cell Survival and Differentiation as Kinase Inhibitor in Human Pluripotent Stem Cells. Stem Cell Reports 2018, 11, 1347–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizaki, T.; Uehata, M.; Tamechika, I.; Keel, J.; Nonomura, K.; Maekawa, M.; Narumiya, S. Pharmacological Properties of Y-27632, a Specific Inhibitor of Rho-Associated Kinases. Molecular Pharmacology 2000, 57, 976–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dijkstra, K.K.; Cattaneo, C.M.; Weeber, F.; Chalabi, M.; de Haar, J. van; Fanchi, L.F.; Slagter, M.; der Velden, D.L. van; Kaing, S.; Kelderman, S.; et al. Generation of Tumor-Reactive T Cells by Co-Culture of Peripheral Blood Lymphocytes and Tumor Organoids. Cell 2018, 174, 1586–1598.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, J.; Marechal, Y.; Van Gool, F.; Andris, F.; Leo, O. Nicotinamide Inhibits B Lymphocyte Activation by Disrupting MAPK Signal Transduction. Biochemical Pharmacology 2007, 73, 831–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, A.-P.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Shen, Y.-Y.; Liu, Y.-H.; Liu, J.-Y.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Wang, R.-B.; Xie, B.-Y.; Pan, X.; et al. Nicotinamide Suppresses Hyperactivation of Dendritic Cells to Control Autoimmune Disease through PARP Dependent Signaling. Nutrients 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Cui, Y.-N.; Wang, H.-W. Effects of Different Concentrations of Nicotinamide on Hematopoietic Stem Cells Cultured in Vitro. World Journal of Stem Cells 2024, 16, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Paz Martins, A.S.; de Andrade, K.Q.; de Araújo, O.R.P.; da Conceição, G.C.M.; da Silva Gomes, A.; Goulart, M.O.F.; Moura, F.A. Extraintestinal Manifestations in Induced Colitis: Controversial Effects of N-Acetylcysteine on Colon, Liver, and Kidney. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2023, 2023, 8811463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yurumez, Y.; Cemek, M.; Yavuz, Y.; Birdane, Y.O.; Buyukokuroglu, M.E. Beneficial Effect of N-Acetylcysteine against Organophosphate Toxicity in Mice. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin 2007, 30, 490–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalatbari Mohseni, G.; Hosseini, S.A.; Majdinasab, N.; Cheraghian, B. Effects of N-Acetylcysteine on Oxidative Stress Biomarkers, Depression, and Anxiety Symptoms in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis. Neuropsychopharmacology Reports 2023, 43, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trimarchi, H.; Mongitore, M.R.; Baglioni, P.; Forrester, M.; Freixas, E. a. R.; Schropp, M.; Pereyra, H.; Alonso, M. N-Acetylcysteine Reduces Malondialdehyde Levels in Chronic Hemodialysis Patients--a Pilot Study. Clin Nephrol 2003, 59, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, T.; Kamal, M.; Iriondo, O.; Amzaleg, Y.; Luo, C.; Thomas, A.; Lee, G.; Hsu, C.-J.; Nguyen, J.D.; Kang, I.; et al. N-Acetyl-L-Cysteine Promotes Ex Vivo Growth and Expansion of Single Circulating Tumor Cells by Mitigating Cellular Stress Responses. Mol Cancer Res 2021, 19, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beshiri, M.L.; Tice, C.M.; Tran, C.; Nguyen, H.M.; Sowalsky, A.G.; Agarwal, S.; Jansson, K.H.; Yang, Q.; McGowen, K.M.; Yin, J.; et al. A PDX/Organoid Biobank of Advanced Prostate Cancers Captures Genomic and Phenotypic Heterogeneity for Disease Modeling and Therapeutic Screening. Clin Cancer Res 2018, 24, 4332–4345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laoukili, J.; Constantinides, A.; Wassenaar, E.C.E.; Elias, S.G.; Raats, D.A.E.; van Schelven, S.J.; van Wettum, J.; Volckmann, R.; Koster, J.; Huitema, A.D.R.; et al. Peritoneal Metastases from Colorectal Cancer Belong to Consensus Molecular Subtype 4 and Are Sensitised to Oxaliplatin by Inhibiting Reducing Capacity. Br J Cancer 2022, 126, 1824–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narasimhan, V.; Wright, J.A.; Churchill, M.; Wang, T.; Rosati, R.; Lannagan, T.R.M.; Vrbanac, L.; Richardson, A.B.; Kobayashi, H.; Price, T.; et al. Medium-Throughput Drug Screening of Patient-Derived Organoids from Colorectal Peritoneal Metastases to Direct Personalized Therapy. Clin Cancer Res 2020, 26, 3662–3670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooft, S.N.; Weeber, F.; Dijkstra, K.K.; McLean, C.M.; Kaing, S.; van Werkhoven, E.; Schipper, L.; Hoes, L.; Vis, D.J.; van de Haar, J.; et al. Patient-Derived Organoids Can Predict Response to Chemotherapy in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Patients. Science Translational Medicine 2019, 11, eaay2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smabers, L.P.; Wensink, E.; Verissimo, C.S.; Koedoot, E.; Pitsa, K.-C.; Huismans, M.A.; Higuera Barón, C.; Doorn, M.; Valkenburg-van Iersel, L.B.; Cirkel, G.A.; et al. Organoids as a Biomarker for Personalized Treatment in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: Drug Screen Optimization and Correlation with Patient Response. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2024, 43, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tojo, M.; Hamashima, Y.; Hanyu, A.; Kajimoto, T.; Saitoh, M.; Miyazono, K.; Node, M.; Imamura, T. The ALK-5 Inhibitor A-83-01 Inhibits Smad Signaling and Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition by Transforming Growth Factor-β. Cancer Science 2005, 96, 791–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, J.; Traynor, R.; Sapkota, G.P. The Specificities of Small Molecule Inhibitors of the TGFß and BMP Pathways. Cellular Signalling 2011, 23, 1831–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, A.-T.; Ghilardi, A.F.; Sun, L. Recent Advances in the Development of RIPK2 Modulators for the Treatment of Inflammatory Diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flebbe, H.; Hamdan, F.H.; Kari, V.; Kitz, J.; Gaedcke, J.; Ghadimi, B.M.; Johnsen, S.A.; Grade, M.; Flebbe, H.; Hamdan, F.H.; et al. Epigenome Mapping Identifies Tumor-Specific Gene Expression in Primary Rectal Cancer. Cancers 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kot, A.; Koszewska, D.; Ochman, B.; Świętochowska, E.; Kot, A.; Koszewska, D.; Ochman, B.; Świętochowska, E. Clinical Potential of Misshapen/NIKs-Related Kinase (MINK) 1—A Many-Sided Element of Cell Physiology and Pathology. Current Issues in Molecular Biology 2024, 46, 13811–13845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischauer, J.; Bastone, A.L.; Selich, A.; John-Neek, P.; Weisskoeppel, L.; Schaudien, D.; Schambach, A.; Rothe, M.; Fleischauer, J.; Bastone, A.L.; et al. TGFβ Inhibitor A83-01 Enhances Murine HSPC Expansion for Gene Therapy. Cells 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, K.P.; McCaffrey, P.G.; Hsiao, K.; Pazhanisamy, S.; Galullo, V.; Bemis, G.W.; Fitzgibbon, M.J.; Caron, P.R.; Murcko, M.A.; Su, M.S.S. The Structural Basis for the Specificity of Pyridinylimidazole Inhibitors of P38 MAP Kinase. Chemistry & Biology 1997, 4, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, D.; Venè, R.; Coco, S.; Longo, L.; Tosetti, F.; Scabini, S.; Mastracci, L.; Grillo, F.; Poggi, A.; Benelli, R. SB202190 Predicts BRAF-Activating Mutations in Primary Colorectal Cancer Organoids via Erk1-2 Modulation. Cells 2023, 12, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavoie, H.; Thevakumaran, N.; Gavory, G.; Li, J.J.; Padeganeh, A.; Guiral, S.; Duchaine, J.; Mao, D.Y.L.; Bouvier, M.; Sicheri, F.; et al. Inhibitors That Stabilize a Closed RAF Kinase Domain Conformation Induce Dimerization. Nat Chem Biol 2013, 9, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bain, J.; Plater, L.; Elliott, M.; Shpiro, N.; Hastie, C.J.; McLauchlan, H.; Klevernic, I.; Arthur, J.S.C.; Alessi, D.R.; Cohen, P. The Selectivity of Protein Kinase Inhibitors: A Further Update. Biochem J 2007, 408, 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Song, E.; Upadhyayula, S.; Dang, S.; Gaudin, R.; Skillern, W.; Bu, K.; Capraro, B.R.; Rapoport, I.; Kusters, I.; et al. Dynamics of Auxilin 1 and GAK in Clathrin-Mediated Traffic. J Cell Biol 2020, 219, e201908142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munson, M.J.; Mathai, B.J.; Ng, M.Y.W.; Trachsel-Moncho, L.; de la Ballina, L.R.; Schultz, S.W.; Aman, Y.; Lystad, A.H.; Singh, S.; Singh, S.; et al. GAK and PRKCD Are Positive Regulators of PRKN-Independent Mitophagy. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 6101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastassiadis, T.; Deacon, S.W.; Devarajan, K.; Ma, H.; Peterson, J.R. Comprehensive Assay of Kinase Catalytic Activity Reveals Features of Kinase Inhibitor Selectivity. Nat Biotechnol 2011, 29, 1039–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhu, Z.; Tong, B.C.-K.; Iyaswamy, A.; Xie, W.-J.; Zhu, Y.; Sreenivasmurthy, S.G.; Senthilkumar, K.; Cheung, K.-H.; Song, J.-X.; et al. A Stress Response P38 MAP Kinase Inhibitor SB202190 Promoted TFEB/TFE3-Dependent Autophagy and Lysosomal Biogenesis Independent of P38. Redox Biology 2020, 32, 101445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garvey, C.M.; Lau, R.; Sanchez, A.; Sun, R.X.; Fong, E.J.; Doche, M.E.; Chen, O.; Jusuf, A.; Lenz, H.-J.; Larson, B.; et al. Anti-EGFR Therapy Induces EGF Secretion by Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts to Confer Colorectal Cancer Chemoresistance. Cancers 2020, 12, 1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dockray, G.J. Gastrin. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2004, 18, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Niekerk, G.; Kelchtermans, L.; Broeckhoven, E.; Coelmont, L.; Alpizar, Y.A.; Dallmeier, K. Cholecystokinin and Gastrin as Immune Modulating Hormones: Implications and Applications. Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews 2024, 80, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benelli, R.; Venè, R.; Ferrari, N. Prostaglandin-Endoperoxide Synthase 2 (Cyclooxygenase-2), a Complex Target for Colorectal Cancer Prevention and Therapy. Transl Res 2018, 196, 42–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pai, R.; Soreghan, B.; Szabo, I.L.; Pavelka, M.; Baatar, D.; Tarnawski, A.S. Prostaglandin E2 Transactivates EGF Receptor: A Novel Mechanism for Promoting Colon Cancer Growth and Gastrointestinal Hypertrophy. Nat Med 2002, 8, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, V.; di Palma, A.; Ricchi, P.; Acquaviva, F.; Giannouli, M.; Di Prisco, A.M.; Iuliano, F.; Acquaviva, A.M. PGE2 Inhibits Apoptosis in Human Adenocarcinoma Caco-2 Cell Line through Ras-PI3K Association and CAMP-Dependent Kinase A Activation. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology 2007, 293, G673–G681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Jung, C.; Liu, C.; Sheng, H. Prostaglandin E2 Stimulates the β-Catenin/T Cell Factor-Dependent Transcription in Colon Cancer*. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2005, 280, 26565–26572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Stevens, J.; Hilton, M.B.; Seaman, S.; Conrads, T.P.; Veenstra, T.D.; Logsdon, D.; Morris, H.; Swing, D.A.; Patel, N.L.; et al. COX-2 Inhibition Potentiates Antiangiogenic Cancer Therapy and Prevents Metastasis in Preclinical Models. Science Translational Medicine 2014, 6, 242ra84–242ra84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roulis, M.; Kaklamanos, A.; Schernthanner, M.; Bielecki, P.; Zhao, J.; Kaffe, E.; Frommelt, L.-S.; Qu, R.; Knapp, M.S.; Henriques, A.; et al. Paracrine Orchestration of Intestinal Tumorigenesis by a Mesenchymal Niche. Nature 2020, 580, 524–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiso, A.; Heinemann, A.; Kargl, J. Prostaglandin E2 in the Tumor Microenvironment, a Convoluted Affair Mediated by EP Receptors 2 and 4. Pharmacological Reviews 2024, 76, 388–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkowski, T.A.; Li, B.; Andersen, J.G.; Kumar, B.; Mroz, E.A.; Rocco, J.W. Y-27632 Acts beyond ROCK Inhibition to Maintain Epidermal Stem-like Cells in Culture. J Cell Sci 2023, 136, jcs260990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, A.K.-L.; Chen, X.; Lim, Y.M.; Reuveny, S.; Oh, S.K.W. Inhibition of ROCK-Myosin II Signaling Pathway Enables Culturing of Human Pluripotent Stem Cells on Microcarriers without Extracellular Matrix Coating. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 2014, 20, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Qi, Z.; Li, X.; Du, Y.; Chen, Y.-G. Monolayer Culture of Intestinal Epithelium Sustains Lgr5+ Intestinal Stem Cells. Cell Discov 2018, 4, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozuka, K.; He, Y.; Koo-McCoy, S.; Kumaraswamy, P.; Nie, B.; Shaw, K.; Chan, P.; Leadbetter, M.; He, L.; Lewis, J.G.; et al. Development and Characterization of a Human and Mouse Intestinal Epithelial Cell Monolayer Platform. Stem Cell Reports 2017, 9, 1976–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbert, K.J.; Ashton, T.M.; Prevo, R.; Pirovano, G.; Higgins, G.S. T-LAK Cell-Originated Protein Kinase (TOPK): An Emerging Target for Cancer-Specific Therapeutics. Cell Death Dis 2018, 9, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlobec, I.; Molinari, F.; Kovac, M.; Bihl, M.P.; Altermatt, H.J.; Diebold, J.; Frick, H.; Germer, M.; Horcic, M.; Montani, M.; et al. Prognostic and Predictive Value of TOPK Stratified by KRAS and BRAF Gene Alterations in Sporadic, Hereditary and Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Patients. Br J Cancer 2010, 102, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Li, J.; Xu, M.; Zhao, Q.; Hou, Y.; Yao, L.; Zhong, Y.; Chou, P.-C.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, P.; et al. PKCε Phosphorylates MIIP and Promotes Colorectal Cancer Metastasis through Inhibition of RelA Deacetylation. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barcelo, J.; Samain, R.; Sanz-Moreno, V. Preclinical to Clinical Utility of ROCK Inhibitors in Cancer. Trends in Cancer 2023, 9, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Medium | Additives | EGF ng/ml | Wnt3a ng/ml; or %CM | R-spondin ng/ml or %CM | Noggin ng/ml or %CM | A83-01 µM | SB202190 µM | Nic mM | NAC mM | Gast nM | PGE2 µM | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advanced DMEM/F12 |

B27 +N2 | 50 | 100 | 1000 | 100 | 0.5 | 10 | 10 | 1 | 10** | 10* | [1] |

| Advanced DMEM/F12 |

B27noA +N2 | 50 | 50% CM | 1000*** | 100 | LY2157299 0.5uM | 10 | 10 | 1 | 48 1ug/ml | 0.01 | [3] |

| Advanced DMEM/F12 |

B27+N2 | 50 +IGF1 50ng/ml |

100 | 500 | 100 | 0.5 | 1 | [4] | ||||

| Advanced DMEM/F12 |

B27 | 50 | 50% CM | 10% CM | 100 | 0.5 | 10 | 1 | 10 | [5] | ||

| Advanced DMEM/F12 |

B27 | 50 | 50% CM or omitted in CRC |

20% CM | 10% CM | 0.5 | 3 | 10 | 1.25 | 10 | 0.01 | [6] |

| Advanced DMEM/F12 |

B27 | 50 | 50% CM or omitted in most CRC |

10% CM omitted in most CRC |

100 | 0.5 | 10 | 1 | 10 | [7] | ||

| Advanced DMEM/F12 | B27+N2 | 50 +bFGF 20ng/ml |

omitted (CRC) | omitted (CRC) | omitted (CRC) | 1 | [8] | |||||

| Advanced DMEM/F12 | B27 | 50 | 50% CM or omitted (CRC) | 20% CM | 10% CM | 0.5 | 10 | 10 | 1.25 nM | [9] | ||

| Advanced DMEM/F12 | B27 | 50 | omitted (CRC) | omitted (CRC) | 100 | 0.5 | 1 | 10 | [10] | |||

| Advanced DMEM/F12 | B27 | 50 | 50% CM | 1000 | 100 | 0.5 | 10 | 1 | 10 | [11] | ||

| Avanced DMEM/F12 | B27 | 50 | 50% CM or omitted (CRC) |

20% CM | 10% CM | 0.5 | 10 | 10 | 12.5 err? | [12] | ||

| Advanced DMEM/F12 | B27 | 50 | omitted (CRC) | 500 | 100 | 0.5 | 3 | 1 | 10 | 0.01 | [13] | |

| Advanced DMEM/F12 | B27 | 50 | 20% Afamin-Wnt3A serum-free | 10% CM | 100 | 0.5 | 10 | 1 | 10 | [14] | ||

| Avanced DMEM/F12 | B27 | 50 +FGF10 100ng/ml |

omitted (CRC) | 20% CM | 100 | 0.5 | 3 | 10 | 1.25 | 10 | 0.01 | [15] |

| Avanced DMEM/F12 | B27 | 50 | omitted (CRC) | omitted (CRC) | 100 | 0.5 | 1 | 10 | [16] | |||

| Avanced DMEM/F12 | B27 | 50 +bFGF 10ng/ml +FGF10 10ng/ml |

100 | 500 | 100 | 0.5 | 5 | 4 | 10 | 0.1 | [17] |

| Reagent | Unique components | Shared by all | Shared by two |

|---|---|---|---|

| Advanced DMEM-F12 | DMEM/F12, Ascorbic acid, Ammonium metavanadate, Cupric sulfate, Manganous chloride, (+Hepes) | Insulin, Holo-Transferrin, Sodium selenite | Ethanolamine, Glutathione, Bovine serum albumin (AlbuMAX® II, lipid-rich) |

| B27 w/woVit.A | Catalase, Superoxide dismutase, Triodo-L-thyronine, L-carnitine, D-galactose, Corticosterone, Linoleic acid, Linolenic acid, Retinol acetate (not included in the retinol-free formula), DL-alpha tocopherol, DL-alpha tocopherol acetate, Biotin, Vitamin B12, Zinc sulfate, Selenium, Sodium pyruvate, Lipoic acid, L-Alanine, L-Glutamate, L-Glutamine, L-Proline | Insulin, Holo-Transferrin, Sodium selenite | Ethanolamine, Glutathione-reduced, Bovine serum albumin (Fraction V IgG free, fatty-acid poor), Putrescine, Progesterone |

| N2 | - | Insulin, Transferrin, Sodium selenite | Putrescine, Progesterone |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).