Submitted:

12 December 2025

Posted:

15 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Neuromechanobiology: A Brief Historical Perspective

3. Decoding the Molecular Symphony of Mechanotransduction in the Nervous System: From Mechanical Signals, Ion Channels to Cytoskeletal Dynamics

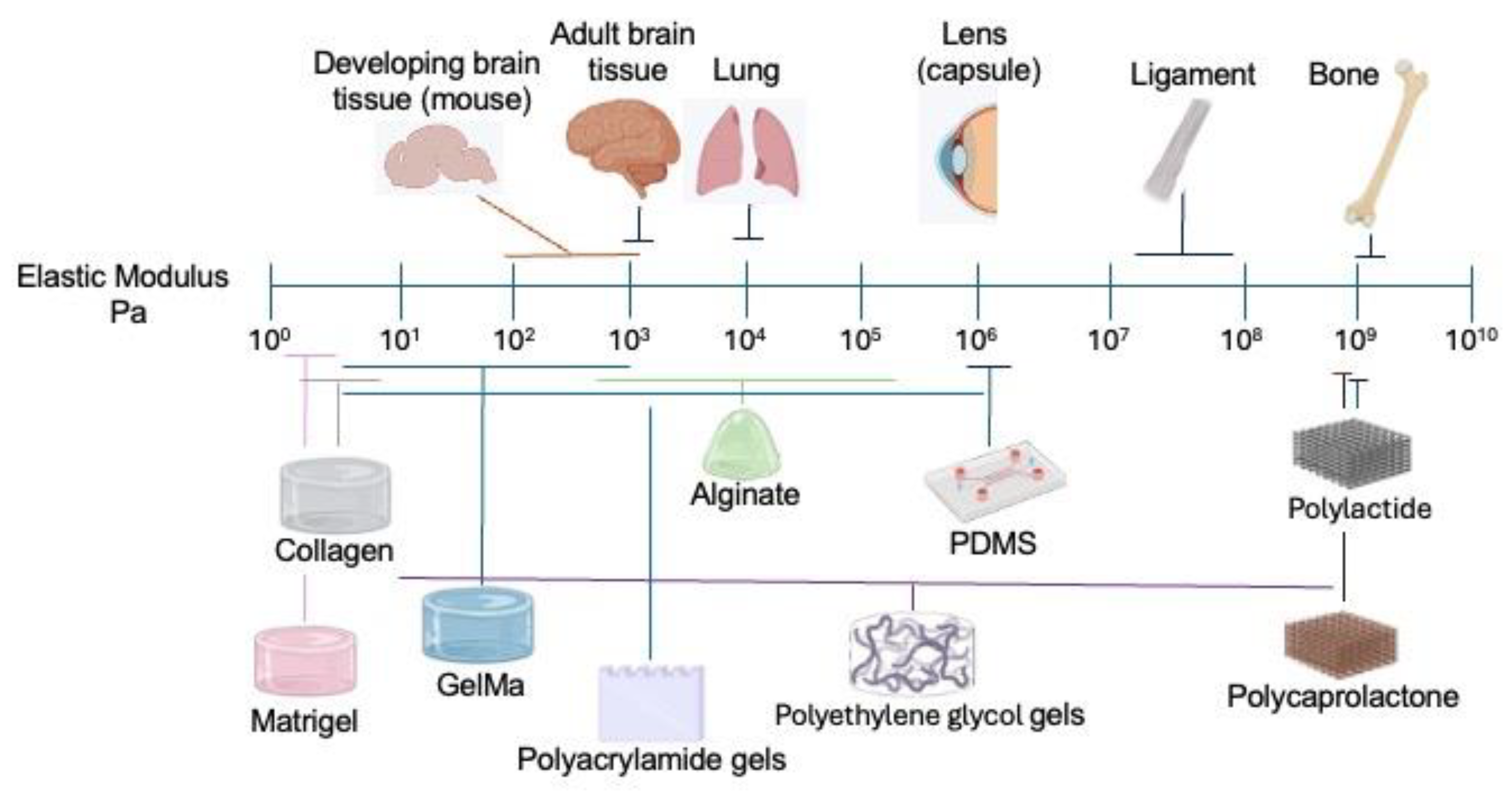

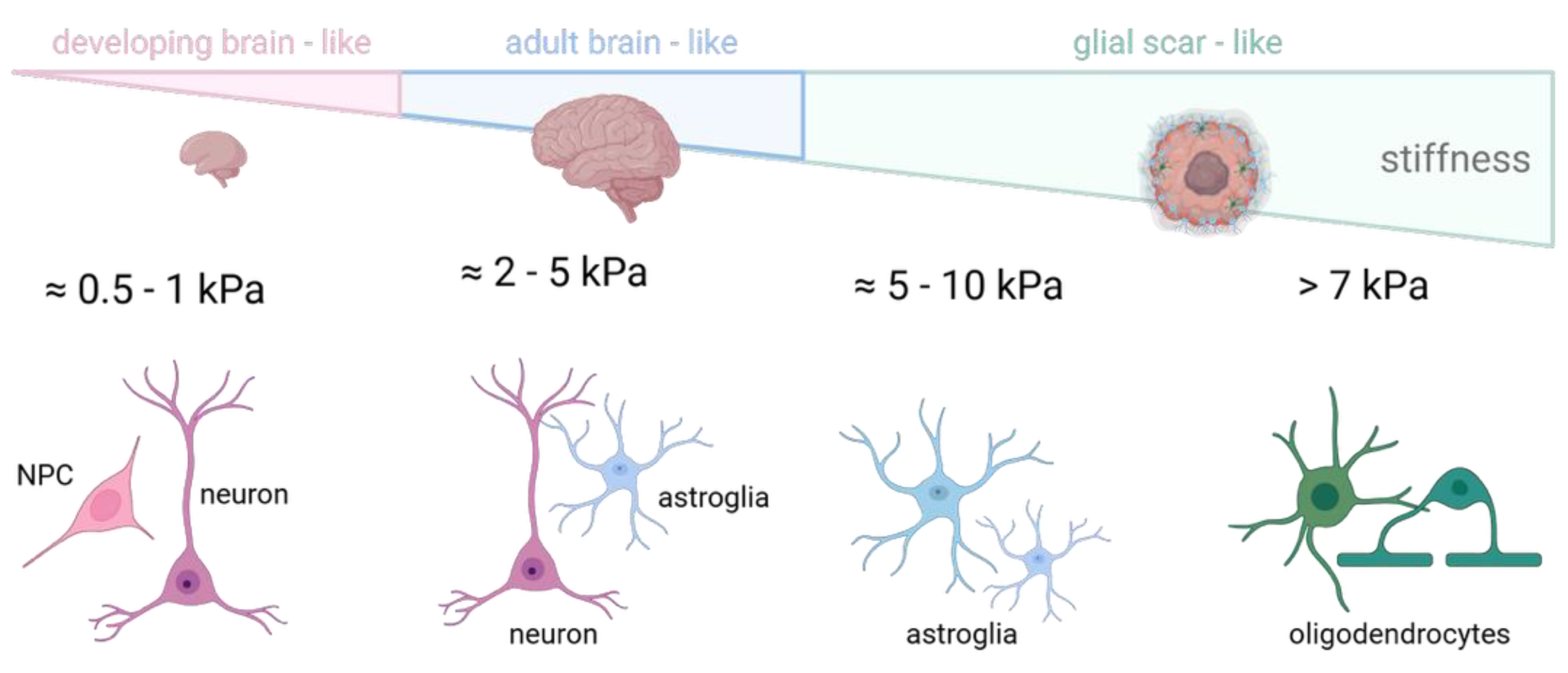

3.1. Mechanics of the Brain

3.2. Mechanosensing in Brain Cells

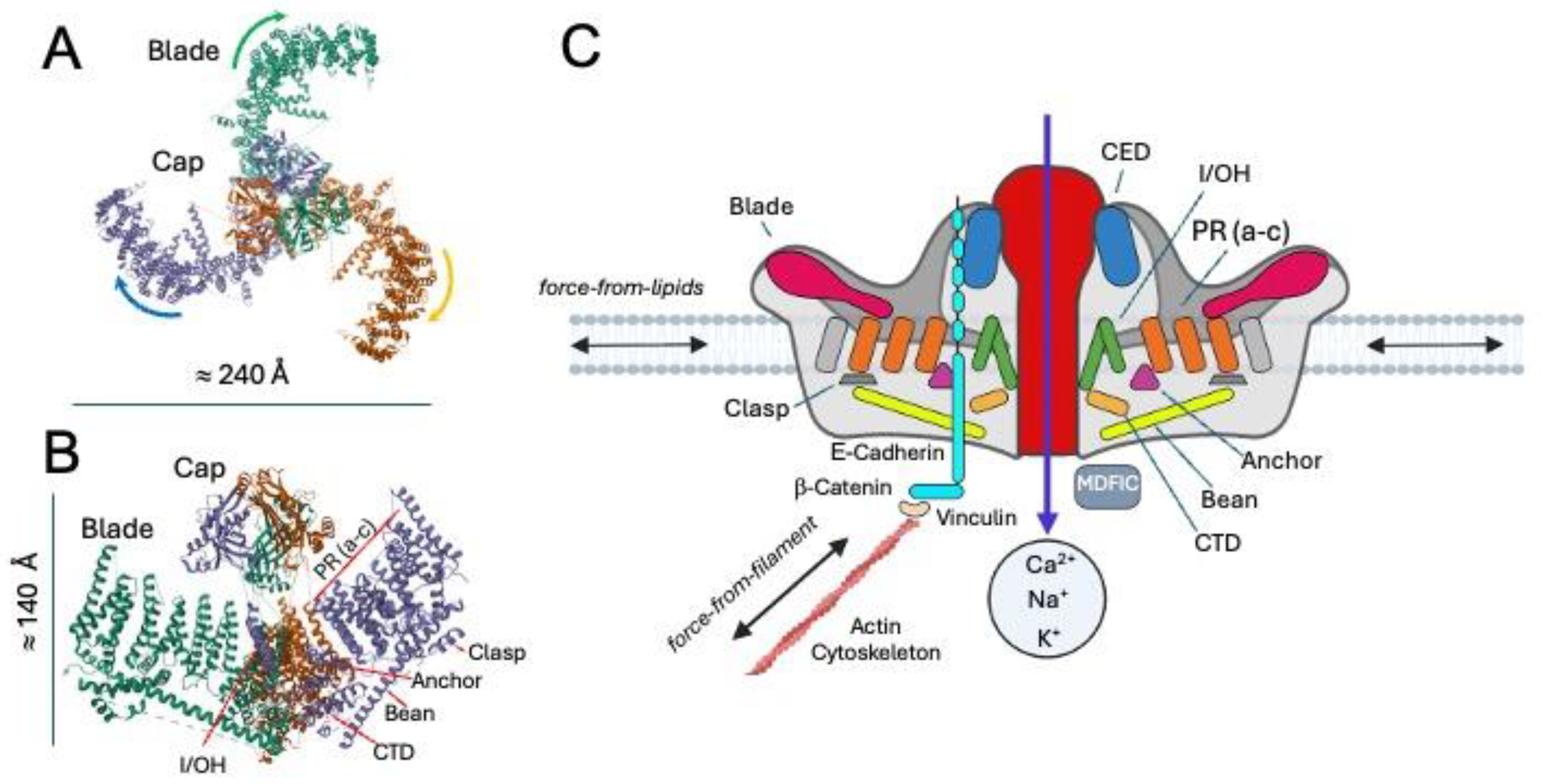

3.3. Integrating Mechanical Signals in Neural Cells

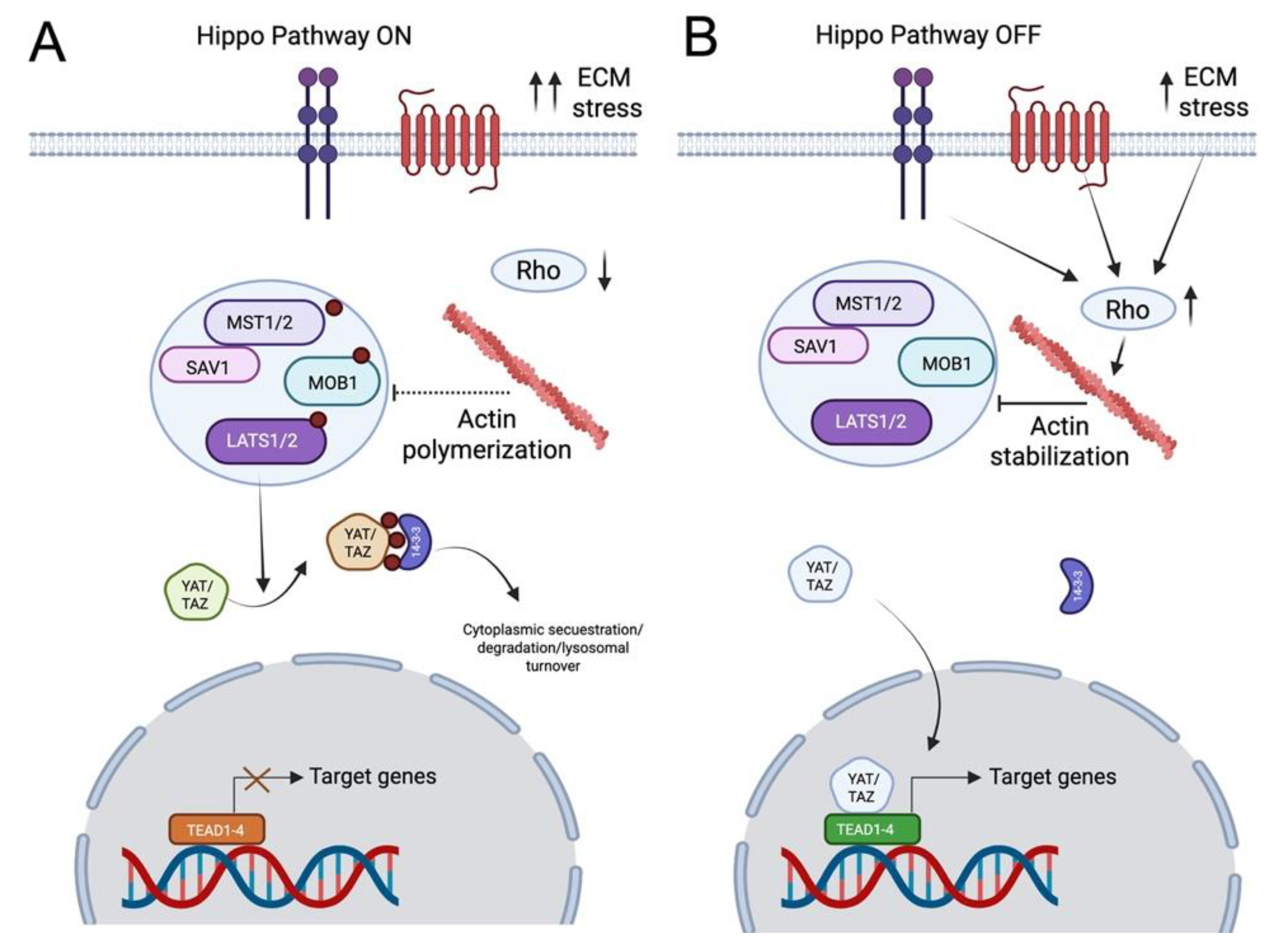

3.4. Hippo Signaling at the Crossroads of Cytoskeletal Dynamics and Neuronal Mechanotransduction

4. Mechanotransduction in Neurons and Glial Cells

4.1. Neural Stem Cell Proliferation and Cortical Lamination

4.2. Modeling Neural Stem Cell Proliferation and Neural Tube Closure in Brain Organoids

5. From Mechanical Signals to Brain Architecture (i): Mechanotransduction in Cortical Gyrification and Brain Regionalization

5.1. Brain Regionalization

5.2. Pallial–Subpallial Domains: Mechanics and Migration

6. From Mechanical Signals to Brain Architecture (ii): Mechanosensing During Neuronal Functional Maturation

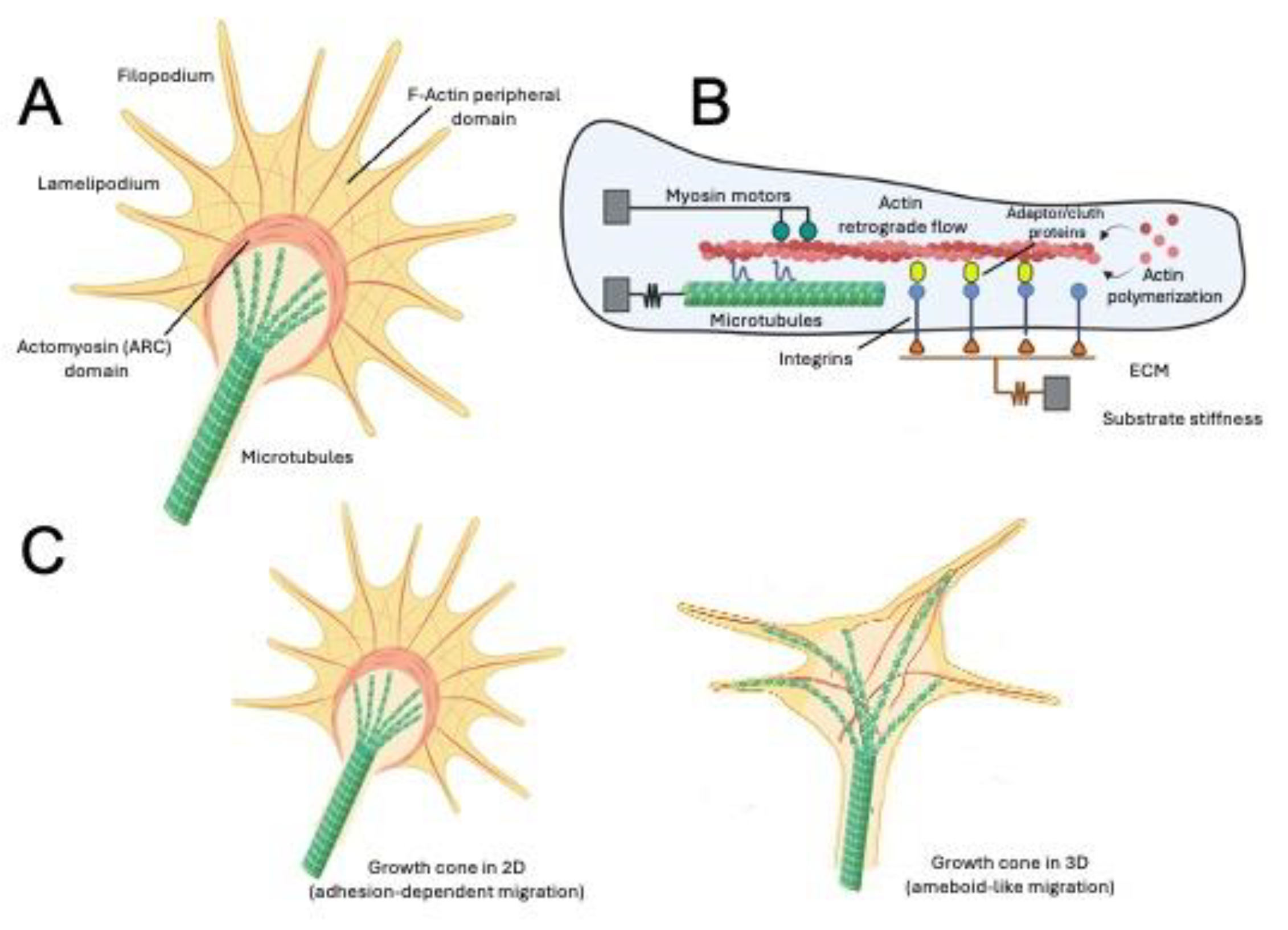

6.1. Environment, Axonal Growth, and Development of Neuronal Activity

7. Can 3D Cultures and Lab-on-Chip Devices Accurately Model Mechanotransduction in Neuronal Activity?

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| MS | Multiple sclerosis |

| GBM | Glioblastoma multiforme |

| FAK | Focal adhesion kinase |

| YAP | Yes-associated protein |

| TAZ | Transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| MSICs | Mechanosensitive ion channels |

| ENaC | Epithelial sodium channels |

| DEG | Degenerins |

| TRP | Transient receptor potential |

| K2P | Two-pore domain potassium channel |

| MDFIC | MyoD family inhibitor protein |

| DRG | Dorsal root ganglia |

| KCNK2 | Potassium channel subfamily K member 2 |

| KCNK10 | Potassium channel subfamily K member 10 |

| TRAAK | TWIK-related arachidonic acid-stimulated K⁺ channel |

| KCNK4 | Potassium channel subfamily K member 4 |

| TRPA | Transient receptor potential Ankyrin |

| TRPC | Transient receptor potential Canonical |

| TRPM | Transient receptor potential Melastatin |

| TRPML | Transient receptor potential Mucolipin |

| TRPN | Transient receptor potential NO-mechano-potential, NOMP |

| TRPP | Transient receptor potential Polycystin |

| TRPV | Transient receptor potential Vanilloid |

| TMEM150C | Transmembrane protein 150C |

| TMEM | Transmembrane protein |

| GPCRs | G-protein-coupled receptors |

| LPHN2 | Latrophilin-2 |

| AMPA | A -amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid |

| FTD | Frontotemporal dementia |

| MST1/2 | Mammalian Sterile 20-like protein kinase 1/2 |

| SAV1 | Salvador homolog 1 |

| LATS1/2 | Large Tumor Suppressor 1/2 |

| AMOT | Angiomotin |

| SHH | Sonic hedgehog |

| NSCs | Neural stem cells |

| MAC | Methacrylamide chitosan |

| TUJ1 | Type III β-tubulin isoform |

| NPC | Neural progenitor cell |

| aRG | Apical radial glia |

| IPs | Intermediate progenitors |

| oRG | Outer radial glia |

| CCE | Constrained cortical expansion |

| TIG | Tension-induced growth |

| MRE | Magnetic resonance elastography |

| GE | Ganglionic eminence |

| MEA | Microelectrode array |

| AFM | Atomic force microscopy |

| EEG | Electroencephalogram |

| TBI | Traumatic brain injury |

References

- Nagatomi, J.; Ebong, E.E. Mechanobiology handbook, Second edition; CRC Press, Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton, 2019; p. xxii, 681 pages. [Google Scholar]

- Procès, A.; Luciano, M.; Kalukula, Y.; Ris, L.; Gabriele, S. Multiscale Mechanobiology in Brain Physiology and Diseases. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 823857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, L.W.; Cronin, N.M.; DeMali, K.A. Mechanotransduction: Forcing a change in metabolism. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2023, 84, 102219–102219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakhshandeh, B.; Sorboni, S.G.; Ranjbar, N.; Deyhimfar, R.; Abtahi, M.S.; Izady, M.; Kazemi, N.; Noori, A.; Pennisi, C.P. Mechanotransduction in tissue engineering: Insights into the interaction of stem cells with biomechanical cues. Exp. Cell Res. 2023, 431, 113766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, C.M.; Moeendarbary, E.; Sheridan, G.K. Mechanobiology of the brain in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Neurosci 2021, 53(12), 3851–3878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abuwarda, H.; Pathak, M.M. Mechanobiology of neural development. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2020, 66, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ransanz, L.C.; Van Altena, P.F.J.; Heine, V.M.; Accardo, A. Engineered cell culture microenvironments for mechanobiology studies of brain neural cells. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 1096054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, E.D.; Morais, M.R.; Ferreira, H.P.; Silva, M.M.; Guimarães, S.C.; Pêgo, A.P. A paradigm shift: Bioengineering meets mechanobiology towards overcoming remyelination failure. Biomaterials 2022, 283, 121427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minegishi, T.; Inagaki, N. Forces to Drive Neuronal Migration Steps. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javier-Torrent, M.; Zimmer-Bensch, G.; Nguyen, L. Mechanical Forces Orchestrate Brain Development. Trends Neurosci. 2021, 44, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, L.D.; Xiong, F. Mechanics of neural tube morphogenesis. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 130, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Essen, D.C. Biomechanical models and mechanisms of cellular morphogenesis and cerebral cortical expansion and folding. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2023, 140, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutalik, S.P.; Ghose, A. Axonal cytomechanics in neuronal development. J. Biosci. 2020, 45, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, L.E.; Gupton, S.L. Mechanistic advances in axon pathfinding. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2020, 63, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koser, D.E. Mechanosensing is critical for axon growth in the developing brain. Nat Neurosci 2016, 19(12), 1592–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, J.; Weber, I.P.; Thompson, A.J.; Keynes, R.J.; Franze, K. Axons in the Chick Embryo Follow Soft Pathways Through Developing Somite Segments. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 917589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llinares-Benadero, C.; Borrell, V. Deconstructing cortical folding: genetic, cellular and mechanical determinants. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2019, 20, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, G.F.; Fagetti, J.; Vierci, G.; Brauer, M.M.; Unsain, N.; Richeri, A. Extracellular matrix stiffness negatively affects axon elongation, growth cone area and F-actin levels in a collagen type I 3D culture. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2021, 16, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveri, H.; Franze, K.; Goriely, A. Theory for Durotactic Axon Guidance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021, 126, 118101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šmít, D.; Fouquet, C.; Pincet, F.; Zapotocky, M.; Trembleau, A. Axon tension regulates fasciculation/defasciculation through the control of axon shaft zippering. eLife 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minegishi, T.; Hasebe, H.; Aoyama, T.; Naruse, K.; Takahashi, Y.; Inagaki, N. Mechanical signaling through membrane tension induces somal translocation during neuronal migration. EMBO J. 2024, 44, 767–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakazawa, N. PIEZO1-dependent mode switch of neuronal migration in heterogeneous microenvironments in the developing brain. Cell Rep 2025, 44(3), 115405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keung, A.J.; de Juan-Pardo, E.M.; Schaffer, D.V.; Kumar, S. Rho GTPases Mediate the Mechanosensitive Lineage Commitment of Neural Stem Cells. STEM CELLS 2011, 29, 1886–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, E. Substrate stress relaxation regulates neural stem cell fate commitment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2024, 121(28), p. e2317711121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentile, A.; Stavropoulou, K.; Long, K.R. ECM Mechanics in Central Nervous System Morphogenesis. Dev. Neurosci. 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, E.; Baek, J.; Fulmore, C.; Song, M.; Kim, T.-S.; Kumar, S.; Schaffer, D.V. Spectrin mediates 3D-specific matrix stress-relaxation response in neural stem cell lineage commitment. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadk8232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y.; Kang, B.; Lee, P.R.; Kim, K.; Hong, G.-S. Expression patterns of Piezo1 in the developing mouse forebrain. Anat. Embryol. 2024, 229, 759–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutiño, B.C.; Mayor, R. Neural crest mechanosensors: Seeing old proteins in a new light. Dev. Cell 2022, 57, 1792–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shellard, A.; Mayor, R. Integrating chemical and mechanical signals in neural crest cell migration. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2019, 57, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortorella, I.; Argentati, C.; Emiliani, C.; Morena, F.; Martino, S. Biochemical Pathways of Cellular Mechanosensing/Mechanotransduction and Their Role in Neurodegenerative Diseases Pathogenesis. Cells 2022, 11, 3093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, W.J. The mechanobiology of brain function. Nat Rev Neurosci 2012, 13(12), 867–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, E.K.; Franze, K. Mechanics in the nervous system: From development to disease. Neuron 2023, 112, 342–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilinc, D. The Emerging Role of Mechanics in Synapse Formation and Plasticity. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaudon, F.; Cingolani, L.A. Unlocking mechanosensitivity: integrins in neural adaptation. Trends Cell Biol. 2024, 34, 1029–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasuba, K.C.; Buccino, A.P.; Bartram, J.; Gaub, B.M.; Fauser, F.J.; Ronchi, S.; Kumar, S.S.; Geissler, S.; Nava, M.M.; Hierlemann, A.; et al. Mechanical stimulation and electrophysiological monitoring at subcellular resolution reveals differential mechanosensation of neurons within networks. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2024, 19, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaub, B.M.; Kasuba, K.C.; Mace, E.; Strittmatter, T.; Laskowski, P.R.; Geissler, S.A.; Hierlemann, A.; Fussenegger, M.; Roska, B.; Müller, D.J. Neurons differentiate magnitude and location of mechanical stimuli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2019, 117, 848–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, B.A.; Roy, H.; De Koninck, P.; Grütter, P.; De Koninck, Y. Dendritic Spine Viscoelasticity and Soft-Glassy Nature: Balancing Dynamic Remodeling with Structural Stability. Biophys. J. 2007, 92, 1419–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ucar, H.; Watanabe, S.; Noguchi, J.; Morimoto, Y.; Iino, Y.; Yagishita, S.; Takahashi, N.; Kasai, H. Mechanical actions of dendritic-spine enlargement on presynaptic exocytosis. Nature 2021, 600, 686–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Liu, S.; Wu, X.; Yu, Z.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, W.-J.; Zavodnik, I.; Zheng, J.; Li, C.; Zhao, H. Mechanism of Stiff Substrates up-Regulate Cultured Neuronal Network Activity. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 5, 3475–3482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-Y.; Xie, J.; Li, C.-X.; Chen, W.-Y.; Liu, B.-L.; Wu, X.-A.; Li, S.-N.; Huo, B.; Jiang, L.-H.; et al. Stiff substrates enhance cultured neuronal network activity. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, srep06215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patz, S.; Fovargue, D.; Schregel, K.; Nazari, N.; Palotai, M.; Barbone, P.E.; Fabry, B.; Hammers, A.; Holm, S.; Kozerke, S.; et al. Imaging localized neuronal activity at fast time scales through biomechanics. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaav3816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C.B., J. Mechanobiological Modulation of In Vitro Astrocyte Reactivity Using Variable Gel Stiffness. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 2024, 10(7), 4279–4296. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, S.; Cui, Y.; Wang, H.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, T.; Sun, S.; Zhou, Z.; Zhong, Y.; Xiao, B. Astrocytic Piezo1-mediated mechanotransduction determines adult neurogenesis and cognitive functions. Neuron 2022, 110, 2984–2999.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.H.; Qiu, Z. Sensational astrocytes: Mechanotransduction in adult brain function. Neuron 2022, 110, 2891–2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turovsky, E.A.; Braga, A.; Yu, Y.; Esteras, N.; Korsak, A.; Theparambil, S.M.; Hadjihambi, A.; Hosford, P.S.; Teschemacher, A.G.; Marina, N.; et al. Mechanosensory Signaling in Astrocytes. J. Neurosci. 2020, 40, 9364–9371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jäntti, H.; Sitnikova, V.; Ishchenko, Y.; Shakirzyanova, A.; Giudice, L.; Ugidos, I.F.; Gómez-Budia, M.; Korvenlaita, N.; Ohtonen, S.; Belaya, I.; et al. Microglial amyloid beta clearance is driven by PIEZO1 channels. J. Neuroinflammation 2022, 19, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Jia, H.; Pan, S.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Q.; Feng, Y.; Ding, W.; Luo, T. Matrix Stiffness Regulates Interleukin-10 Secretion in Human Microglia (HMC3) via YAP-Mediated Mechanotransduction. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2025, 43, e70061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnaloja, F.; Limonta, E.; Mancosu, C.; Morandi, F.; Boeri, L.; Albani, D.; Raimondi, M.T. Unravelling the mechanotransduction pathways in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Biol. Eng. 2023, 17, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryniarska-Kubiak, N.; Kubiak, A.; Basta-Kaim, A. Mechanotransductive Receptor Piezo1 as a Promising Target in the Treatment of Neurological Diseases. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2023, 21, 2030–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, N.G.; Ffrench-Constant, C. Physical forces in myelination and repair: a question of balance? J. Biol. 2009, 8, 78–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitnikova, V.; Nurkhametova, D.; Braidotti, N.; Ciubotaru, C.D.; Giudice, L.; Impola, U.; Kärkkäinen, S.; Kalapudas, J.; Penttilä, E.; Löppönen, H.; et al. Increased activity of Piezo1 channel in red blood cells is associated with Alzheimer's disease-related dementia. Alzheimer's Dement. 2025, 21, e70368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twohy, K.E.; Kramer, M.K.; Diano, A.M.; Bailey, O.M.; Delgorio, P.L.; McIlvain, G.; McGarry, M.D.J.; Martens, C.R.; Schwarb, H.; Hiscox, L.V.; et al. Mechanical Properties of the Cortex in Older Adults and Relationships With Personality Traits. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2025, 46, e70147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavuluri, K.; Huston, J.; Ehman, R.L.; Manduca, A.; Vemuri, P.; Jack, C.R.; Senjem, M.L.; Murphy, M.C. Brain mechanical properties predict longitudinal cognitive change in aging and Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2025, 147, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondapaneni, R.V.; Gurung, S.K.; Nakod, P.S.; Goodarzi, K.; Yakati, V.; Lenart, N.A.; Rao, S.S. Glioblastoma mechanobiology at multiple length scales. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2024, 160, 213860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S.; Fleck, M.; Ayushman, M.; Tong, X.; Mikos, G.; Jones, S.; Soto, L.; Yang, F. Matrix Stiffness Regulates GBM Migration and Chemoradiotherapy Responses via Chromatin Condensation in 3D Viscoelastic Matrices. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 10342–10359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pontes, B.; Mendes, F.A. Mechanical Properties of Glioblastoma: Perspectives for YAP/TAZ Signaling Pathway and Beyond. Diseases 2023, 11, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoonkari, M.; Liang, D.; Kamperman, M.; Kruyt, F.A.E.; van Rijn, P. Physics of Brain Cancer: Multiscale Alterations of Glioblastoma Cells under Extracellular Matrix Stiffening. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breves, S.L.; Di Giammartino, D.C.; Nicholson, J.; Cirigliano, S.; Mahmood, S.R.; Lee, U.J.; Martinez-Fundichely, A.; Jungverdorben, J.; Singhania, R.; Rajkumar, S.; et al. Three-dimensional regulatory hubs support oncogenic programs in glioblastoma. Mol. Cell 2025, 85, 1330–1348.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turpo-Peqqueña, A.G.; Luna-Prado, S.; Valencia-Arce, R.J.; Del-Carpio-Carrazco, F.L.; Gómez, B. A Theoretical Study on the Efficacy and Mechanism of Combined YAP-1 and PARP-1 Inhibitors in the Treatment of Glioblastoma Multiforme Using Peruvian Maca Lepidium meyenii. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, K.J.; Chen, J.; Coombes, J.D.; Aghi, M.K.; Kumar, S. Dissecting and rebuilding the glioblastoma microenvironment with engineered materials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2019, 4, 651–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundy, T.J.; De Leon, E.; Griffin, K.R.; Stringer, B.W.; Day, B.W.; Fabry, B.; Cooper-White, J.; O’nEill, G.M. Differential response of patient-derived primary glioblastoma cells to environmental stiffness. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 23353–23353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Hou, X.; Ding, L.; Wei, J.; Hou, W. Piezo1-related physiological and pathological processes in glioblastoma. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2025, 13, 1536320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Chang, H.; Yeun, J.; Baek, J.; Im, S.G. Enhanced Glioblastoma-Targeted Aptamer Discovery by 3D Cell-SELEX with Hyaluronic Acid Hydrogel. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2025, 11, 4806–4817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payan, B.A. Hydrogel microdroplet based glioblastoma drug screening platform. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanigasekara, J.; Cullen, P.J.; Bourke, P.; Tiwari, B.; Curtin, J.F. Advances in 3D culture systems for therapeutic discovery and development in brain cancer. Drug Discov. Today 2022, 28, 103426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, C.; Li, A.; Jing, W.; Sun, P.; Huang, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Du, W.; Zhang, R.; et al. Immunostimulant hydrogel for the inhibition of malignant glioma relapse post-resection. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2021, 16, 538–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Der Meulen, M.; Beaupré, G.; Carter, D. Mechanobiologic influences in long bone cross-sectional growth. Bone 1993, 14, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motz, C.T.; Kabat, V.; Saxena, T.; Bellamkonda, R.V.; Zhu, C. Neuromechanobiology: An Expanding Field Driven by the Force of Greater Focus. Adv. Heal. Mater. 2021, 10, 2100102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, W.J. Neuromechanobiology, in Mechanobiology in Health and Disease; 2018; pp. 327–348. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, D.A.W. On growth and form; University press: Cambridge Eng., 1917; p. xv, 793 p. [Google Scholar]

- Crowe, A. A mechanical model of the mammalian muscle spindle. J. Theor. Biol. 1968, 21, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagbarth, K.E.; Vallbo, A.B. Afferent response to mechanical stimulation of muscle receptors in man. Acta Soc Med Ups 1967, 72(1), 102–4. [Google Scholar]

- Hustert, R.; Bräunig, P.; Pflüger, H.J. Distribution and specific central projections of mechanoreceptors in the thorax and proximal leg joints of locusts. I. Morphology, location and innervation of internal proprioceptors of pro- and metathorax and their central projections. Cell Tissue Res. 1981, 216, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordin, M.; Hagbarth, K. Mechanoreceptive units in the human infra-orbital nerve. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1989, 135, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honda, C.N.; Mense, S.; Perl, E.R. Neurons in ventrobasal region of cat thalamus selectively responsive to noxious mechanical stimulation. J. Neurophysiol. 1983, 49, 662–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiesenfeld-Hallin, Z.; Hallin, R.G. The influence of the sympathetic system on mechanoreception and nociception. A review. Hum. Neurobiol. 1984, 3, 41–6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McLain, R.F. Mechanoreceptor endings in human cervical facet joints. Iowa Orthop. J. 1993, 13, 149–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, F. Mechanical transduction in biological systems. Crit. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 1988, 16, 141–69. [Google Scholar]

- Pickles, J.O.; Corey, D.P. Mechanoelectrical transduction by hair cells. Trends Neurosci. 1992, 15, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudspeth, A.J. Models for mechanoelectrical transduction by hair cells. Prog. Clin. Biol. Res. 1985, 176, 193–205. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, A.J.; Honoré, E. Properties and modulation of mammalian 2P domain K+ channels. Trends Neurosci. 2001, 24, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesage, F.; Lazdunski, M. Molecular and functional properties of two-pore-domain potassium channels. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2000, 279, F793–F801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.J.; Lazdunski, M.; Honoré, E. Lipid and mechano-gated 2P domain K+ channels. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2001, 13, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingber, D.E. Tensegrity-based mechanosensing from macro to micro. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2008, 97, 163–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, S.-H.; Lukacs, V.; de Nooij, J.C.; Zaytseva, D.; Criddle, C.R.; Francisco, A.; Jessell, T.M.; A Wilkinson, K.; Patapoutian, A. Piezo2 is the principal mechanotransduction channel for proprioception. Nat. Neurosci. 2015, 18, 1756–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming, M.S.; Li, J.J.; Ramos, D.; Li, T.; Talmage, D.A.; Abe, S.-I.; Arber, S.; Luo, W. A RET-ER81-NRG1 Signaling Pathway Drives the Development of Pacinian Corpuscles. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 10337–10355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, L.; Lehnert, B.P.; Liu, J.; Neubarth, N.L.; Dickendesher, T.L.; Nwe, P.H.; Cassidy, C.; Woodbury, C.J.; Ginty, D.D. Genetic Identification of an Expansive Mechanoreceptor Sensitive to Skin Stroking. Cell 2015, 163, 1783–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca-Cusachs, P.; Conte, V.; Trepat, X. Quantifying forces in cell biology. Nat. Cell Biol. 2017, 19, 742–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athamneh, A.I.M.; Suter, D.M. Quantifying mechanical force in axonal growth and guidance. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, L.; Pardo-Pastor, C.; Rosenblatt, J.; Pouliopoulos, A.N. Mechanotransduction as a therapeutic target for brain tumours. EBioMedicine 2025, 117, 105808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, C.F.; Gasperini, L.; Marques, A.P.; Reis, R.L. The stiffness of living tissues and its implications for tissue engineering. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2020, 5, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittall, K.P. In vivo measurement of T2 distributions and water contents in normal human brain. Magn Reson Med 1997, 37(1), 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberle, D.; Fodelianaki, G.; Kurth, T.; Jagielska, A.; Möllmert, S.; Ulbricht, E.; Wagner, K.; Taubenberger, A.V.; Träber, N.; Escolano, J.-C.; et al. Acquired demyelination but not genetic developmental defects in myelination leads to brain tissue stiffness changes. Brain Multiphysics 2020, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, A.; Sousa, N. Magnetic resonance elastography of the ageing brain in normal and demented populations: A systematic review. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2022, 43, 4207–4218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonovaite, N.; Hulshof, L.A.; Hol, E.M.; Wadman, W.J.; Iannuzzi, D. Viscoelastic mapping of mouse brain tissue: Relation to structure and age. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2021, 113, 104159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacManus, D.B.; Pierrat, B.; Murphy, J.G.; Gilchrist, M.D. Region and species dependent mechanical properties of adolescent and young adult brain tissue. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budday, S.; Ovaert, T.C.; Holzapfel, G.A.; Steinmann, P.; Kuhl, E. Fifty Shades of Brain: A Review on the Mechanical Testing and Modeling of Brain Tissue. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2020, 27, 1187–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takamura, T.; Motosugi, U.; Sasaki, Y.; Kakegawa, T.; Sato, K.; Glaser, K.J.; Ehman, R.L.; Onishi, H. Influence of Age on Global and Regional Brain Stiffness in Young and Middle-Aged Adults. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2019, 51, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkin, B.S.; Ilankovan, A.; Morrison, B. Age-Dependent Regional Mechanical Properties of the Rat Hippocampus and Cortex. J. Biomech. Eng. 2009, 132, 011010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatelin, S.; Vappou, J.; Roth, S.; Raul, J.; Willinger, R. Towards child versus adult brain mechanical properties. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2012, 6, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthupillai, R.; Lomas, D.J.; Rossman, P.J.; Greenleaf, J.F.; Manduca, A.; Ehman, R.L. Magnetic Resonance Elastography by Direct Visualization of Propagating Acoustic Strain Waves. Science 1995, 269, 1854–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budday, S.; Sommer, G.; Birkl, C.; Langkammer, C.; Haybaeck, J.; Kohnert, J.; Bauer, M.; Paulsen, F.; Steinmann, P.; Kuhl, E.; et al. Mechanical characterization of human brain tissue. Acta Biomater. 2017, 48, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiscox, L.V.; McGarry, M.D.J.; Schwarb, H.; Van Houten, E.E.W.; Pohlig, R.T.; Roberts, N.; Huesmann, G.R.; Burzynska, A.Z.; Sutton, B.P.; Hillman, C.H.; et al. Standard-space atlas of the viscoelastic properties of the human brain. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2020, 41, 5282–5300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilston, L.E.; Liu, Z.; Phan-Thien, N. Linear Viscoelastic Properties of Bovine Brain Tissue in Shear. Biorheology 1997, 34, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budday, S.; Nay, R.; de Rooij, R.; Steinmann, P.; Wyrobek, T.; Ovaert, T.C.; Kuhl, E. Mechanical properties of gray and white matter brain tissue by indentation. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2015, 46, 318–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, C.; Zhao, H. Mechanical properties of brain tissue based on microstructure. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2022, 126, 104924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McINTOSH, T.K.; Juhler, M.; Wieloch, T. Novel Pharmacologic Strategies in the Treatment of Experimental Traumatic Brain Injury: 1998. J. Neurotrauma 1998, 15, 731–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.; Liu, Z.; Mao, S.; Han, L. Unraveling the Mechanobiology Underlying Traumatic Brain Injury with Advanced Technologies and Biomaterials. Adv. Heal. Mater. 2022, 11, e2200760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Kegel, D. Investigation of tissue level tolerance for cerebral contusion in a controlled cortical impact porcine model. Traffic Inj Prev 2021, 22(8), 616–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwashita, M.; Kataoka, N.; Toida, K.; Kosodo, Y. Systematic profiling of spatiotemporal tissue and cellular stiffness in the developing brain. Development 2014, 141, 3793–3798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Mengual, A.; Segura-Feliu, M.; Sunyer, R.; Sanz-Fraile, H.; Otero, J.; Mesquida-Veny, F.; Gil, V.; Hervera, A.; Ferrer, I.; Soriano, J.; et al. Involvement of Mechanical Cues in the Migration of Cajal-Retzius Cells in the Marginal Zone During Neocortical Development. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 886110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efremov, Y.M.; Zurina, I.M.; Presniakova, V.S.; Kosheleva, N.V.; Butnaru, D.V.; Svistunov, A.A.; Rochev, Y.A.; Timashev, P.S. Mechanical properties of cell sheets and spheroids: the link between single cells and complex tissues. Biophys. Rev. 2021, 13, 541–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, I.D.; McCluskey, D.K.; Tan, C.K.L.; Tracey, M.C. Mechanical characterization of bulk Sylgard 184 for microfluidics and microengineering. J. Micromechanics Microengineering 2014, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, K.; Trujillo-de Santiago, G.; Alvarez, M.M.; Tamayol, A.; Annabi, N.; Khademhosseini, A. Synthesis, properties, and biomedical applications of gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA) hydrogels. Biomaterials 2015, 73, 254–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.-Y.; Zhao, X.; Illeperuma, W.R.K.; Chaudhuri, O.; Oh, K.H.; Mooney, D.J.; Vlassak, J.J.; Suo, Z. Highly stretchable and tough hydrogels. Nature 2012, 489, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertucci, T.B.; Dai, G. Biomaterial Engineering for Controlling Pluripotent Stem Cell Fate. Stem Cells Int. 2018, 2018, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franze, K.; Gerdelmann, J.; Weick, M.; Betz, T.; Pawlizak, S.; Lakadamyali, M.; Bayer, J.; Rillich, K.; Gögler, M.; Lu, Y.-B.; et al. Neurite Branch Retraction Is Caused by a Threshold-Dependent Mechanical Impact. Biophys. J. 2009, 97, 1883–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindqvist, N.; Liu, Q.; Zajadacz, J.; Franze, K.; Reichenbach, A. Retinal Glial (Müller) Cells: Sensing and Responding to Tissue Stretch. Investig. Opthalmology Vis. Sci. 2010, 51, 1683–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, L.A.; Ju, Y.-E.; Marg, B.; Osterfield, M.; Janmey, P.A. Neurite branching on deformable substrates. NeuroReport 2002, 13, 2411–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vincentiis, S. Low Forces Push the Maturation of Neural Precursors into Neurons. Small 2023, 19(30), p. e2205871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallinen, T.; Chung, J.Y.; Rousseau, F.; Girard, N.; Lefèvre, J.; Mahadevan, L. On the growth and form of cortical convolutions. Nat. Phys. 2016, 12, 588–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoletti, M.; Chiodo, L.; Loppini, A. Biophysics and Modeling of Mechanotransduction in Neurons: A Review. Mathematics 2021, 9, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aacute; rnadóttir, J.; Chalfie, M. Eukaryotic Mechanosensitive Channels. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2010, 39, 111–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coste, B.; Mathur, J.; Schmidt, M.; Earley, T.J.; Ranade, S.; Petrus, M.J.; Dubin, A.E.; Patapoutian, A. Piezo1 and Piezo2 Are Essential Components of Distinct Mechanically Activated Cation Channels. Science 2010, 330, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raha, A.; Wu, Y.; Zhong, L.; Raveenthiran, J.; Hong, M.; Taiyab, A.; Wang, L.; Wang, B.; Geng, F. Exploring Piezo1, Piezo2, and TMEM150C in human brain tissues and their correlation with brain biomechanical characteristics. Mol. Brain 2023, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velasco-Estevez, M.; Rolle, S.O.; Mampay, M.; Dev, K.K.; Sheridan, G.K. Piezo1 regulates calcium oscillations and cytokine release from astrocytes. Glia 2019, 68, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Q.; Liu, H.; Yu, W.; Dong, Y.; Zhou, L.; Deng, W.; Hua, F. Mechanical properties of the brain: Focus on the essential role of Piezo1-mediated mechanotransduction in the CNS. Brain Behav. 2023, 13, e3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, B.; Yu, F.; Zhang, X.; Pang, Y.; Zhao, W.; Sun, P.; Li, L. Mechanosensitive Piezo1 channel in physiology and pathophysiology of the central nervous system. Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 90, 102026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Wu, Z.; Wu, M.; Xie, L.; Chen, Q. Piezo2 in Mechanosensory Biology: From Physiological Homeostasis to Disease-Promoting Mechanisms. Cell Prolif. 2025, e70112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, P.; Parpaite, T.; Coste, B. PIEZO channels and newcomers in the mammalian mechanosensitive ion channel family. Neuron 2022, 110, 2713–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Li, W.; Zhao, Q.; Li, N.; Chen, M.; Zhi, P.; Li, R.; Gao, N.; Xiao, B.; Yang, M. Architecture of the mammalian mechanosensitive Piezo1 channel. Nature 2015, 527, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Y. Structure of human PIEZO1 and its slow-inactivating channelopathy mutants. Elife 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulhall, E.M.; Gharpure, A.; Lee, R.M.; Dubin, A.E.; Aaron, J.S.; Marshall, K.L.; Spencer, K.R.; Reiche, M.A.; Henderson, S.C.; Chew, T.-L.; et al. Direct observation of the conformational states of PIEZO1. Nature 2023, 620, 1117–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, M.; Liu, W.; Deng, T.; Zhao, Q.; Li, Y.; Lei, J.; Li, X.; Xiao, B. Structure and mechanogating of the mammalian tactile channel PIEZO2. Nature 2019, 573, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, B. Mechanisms of mechanotransduction and physiological roles of PIEZO channels. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 886–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, A.H.; Grandl, J. Mechanical sensitivity of Piezo1 ion channels can be tuned by cellular membrane tension. eLife 2015, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Lin, C.; Chen, X.; Li, S.; Li, X.; Xiao, B. Structure deformation and curvature sensing of PIEZO1 in lipid membranes. Nature 2022, 604, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yang, X.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, J.; Yuan, J.; Liu, W.; Wang, L.; Zhou, H.; Wu, K.; et al. An intermediate open structure reveals the gating transition of the mechanically activated PIEZO1 channel. Neuron 2024, 113, 590–604.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Jing, F.; Zhao, Y.; You, Z.; Zhang, A.; Qin, S. Piezo1: structural pharmacology and mechanotransduction mechanisms. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2025, 46, 752–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Ma, X.; Lin, Y.; Cheng, D.; Bavi, N.; Secker, G.A.; Li, J.V.; Janbandhu, V.; Sutton, D.L.; Scott, H.S.; et al. MyoD-family inhibitor proteins act as auxiliary subunits of Piezo channels. Science 2023, 381, 799–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, H.; Li, W.; Ling, Q.; Cong, W.; Deng, Y.; Chen, K.; Li, S.; Cui, C.; Wang, W.; et al. GPR146 Facilitates Blood Pressure Elevation and Vascular Remodeling via PIEZO1. Circ. Res. 2025, 137, 605–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Li, J.; Li, X.; Jing, M.; Wang, L.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, Z.; He, J.; Wang, M.; Liu, H.; et al. Piezo1/ITGB1 Synergizes With Ca2+/YAP Signaling to Propel Bladder Carcinoma Progression via a Stiffness-Dependent Positive Feedback Loop. Cancer Med. 2025, 14, e71059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyan, A.; Cox, C.D.; Barnoud, J.; Li, J.; Chan, H.S.; Martinac, B.; Marrink, S.J.; Corry, B. Piezo1 Forms Specific, Functionally Important Interactions with Phosphoinositides and Cholesterol. Biophys. J. 2020, 119, 1683–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Jiang, J.; Yang, X.; Zhou, G.; Wang, L.; Xiao, B. Tethering Piezo channels to the actin cytoskeleton for mechanogating via the cadherin-β-catenin mechanotransduction complex. Cell Rep. 2022, 38, 110342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.J.; Wang, Y.; Mirjavadi, S.S.; Andersen, T.; Moldovan, L.; Vatankhah, P.; Russell, B.; Jin, J.; Zhou, Z.; Li, Q.; et al. Microscale geometrical modulation of PIEZO1 mediated mechanosensing through cytoskeletal redistribution. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dienes, B.; Bazsó, T.; Szabó, L.; Csernoch, L. The Role of the Piezo1 Mechanosensitive Channel in the Musculoskeletal System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, C.; Su, S.; Yu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, K.; Xiang, M.; Ma, H. Essential Roles of PIEZO1 in Mammalian Cardiovascular System: From Development to Diseases. Cells 2024, 13, 1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saotome, K.; Murthy, S.E.; Kefauver, J.M.; Whitwam, T.; Patapoutian, A.; Ward, A.B. Structure of the mechanically activated ion channel Piezo1. Nature 2017, 554, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.M.; Itson-Zoske, B.; Fan, F.; Gani, U.; Rahman, M.; Hogan, Q.H.; Yu, H. Peripheral sensory neurons and non-neuronal cells express functional Piezo1 channels. Mol. Pain 2023, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; La, J.-H.; Hamill, O.P. PIEZO1 Is Selectively Expressed in Small Diameter Mouse DRG Neurons Distinct From Neurons Strongly Expressing TRPV1. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2019, 12, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acheta, J.; Bhatia, U.; Haley, J.; Hong, J.; Rich, K.; Close, R.; Bechler, M.E.; Belin, S.; Poitelon, Y. Piezo channels contribute to the regulation of myelination in Schwann cells. Glia 2022, 70, 2276–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricaud, N. Myelinating Schwann Cell Polarity and Mechanically-Driven Myelin Sheath Elongation. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2018, 11, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, M.M.; Nourse, J.L.; Tran, T.; Hwe, J.; Arulmoli, J.; Dai Trang, T.L.; Bernardis, E.; Flanagan, L.A.; Tombola, F. Stretch-activated ion channel Piezo1 directs lineage choice in human neural stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 16148–16153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenthal, N.R.; Hermanson, O.; Heimrich, B.; Shastri, V.P. Stochastic nanoroughness modulates neuron–astrocyte interactions and function via mechanosensing cation channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2014, 111, 16124–16129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segel, M.; Neumann, B.; Hill, M.F.E.; Weber, I.P.; Viscomi, C.; Zhao, C.; Young, A.; Agley, C.C.; Thompson, A.J.; Gonzalez, G.A.; et al. Niche stiffness underlies the ageing of central nervous system progenitor cells. Nature 2019, 573, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velasco-Estevez, M.; Koch, N.; Klejbor, I.; Caratis, F.; Rutkowska, A. Mechanoreceptor Piezo1 Is Downregulated in Multiple Sclerosis Brain and Is Involved in the Maturation and Migration of Oligodendrocytes in vitro. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 914985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Bian, W.; Yang, D.; Yang, M.; Luo, H. Inhibiting the Piezo1 channel protects microglia from acute hyperglycaemia damage through the JNK1 and mTOR signalling pathways. Life Sci. 2021, 264, 118667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J. Microglial Piezo1 senses Abeta fibril stiffness to restrict Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 2023, 111(1), 15–29 e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servin-Vences, M.R.; Lam, R.M.; Koolen, A.; Wang, Y.; Saade, D.N.; Loud, M.; Kacmaz, H.; Frausto, S.; Zhang, Y.; Beyder, A.; et al. PIEZO2 in somatosensory neurons controls gastrointestinal transit. Cell 2023, 186, 3386–3399.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, K. A prime role for PIEZO2 in DRG neurons in mechanosensation in the gut. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 20, 693–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Ikeda, R.; Ling, J.; Viatchenko-Karpinski, V.; Gu, J.G. Regulation of Piezo2 Mechanotransduction by Static Plasma Membrane Tension in Primary Afferent Neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 9087–9104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.-H.; Ranade, S.; Weyer, A.D.; Dubin, A.E.; Baba, Y.; Qiu, Z.; Petrus, M.; Miyamoto, T.; Reddy, K.; Lumpkin, E.A.; et al. Piezo2 is required for Merkel-cell mechanotransduction. Nature 2014, 509, 622–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vásquez, V.; Scherrer, G.; Goodman, M.B. Sensory Biology: It Takes Piezo2 to Tango. Curr. Biol. 2014, 24, R566–R569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranade, S.S.; Woo, S.-H.; Dubin, A.E.; Moshourab, R.A.; Wetzel, C.; Petrus, M.; Mathur, J.; Bégay, V.; Coste, B.; Mainquist, J.; et al. Piezo2 is the major transducer of mechanical forces for touch sensation in mice. Nature 2014, 516, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, J.; Luo, J.; Yang, P.; Du, J.; Kim, B.S.; Hu, H. Piezo2 channel–Merkel cell signaling modulates the conversion of touch to itch. Science 2018, 360, 530–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranade, S.S.; Syeda, R.; Patapoutian, A. Mechanically Activated Ion Channels. Neuron 2015, 87(6), 1162–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maingret, F.; Fosset, M.; Lesage, F.; Lazdunski, M.; Honoré, E. TRAAK Is a Mammalian Neuronal Mechano-gated K+Channel. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 1381–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medhurst, A.D.; Rennie, G.; Chapman, C.G.; Meadows, H.; Duckworth, M.D.; Kelsell, R.E.; Gloger, I.I.; Pangalos, M.N. Distribution analysis of human two pore domain potassium channels in tissues of the central nervous system and periphery. Mol. Brain Res. 2001, 86, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Huang, L.; Liao, P.; Jiang, R. Contribution of Neuronal and Glial Two-Pore-Domain Potassium Channels in Health and Neurological Disorders. Neural Plast. 2021, 2021, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natale, A.M.; Deal, P.E.; Minor, D.L. Structural Insights into the Mechanisms and Pharmacology of K2P Potassium Channels. J. Mol. Biol. 2021, 433, 166995–166995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diver, M.M.; King, J.V.L.; Julius, D.; Cheng, Y. Sensory TRP Channels in Three Dimensions. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2022, 91, 629–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liedtke, W.B.; Heller, S. TRP ion channel function in sensory transduction and cellular signaling cascades. In Frontiers in neuroscience; CRC/Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton, FL, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo, C.; Martín-Martínez, M.; Gómez-Monterrey, I.; González-Muñiz, R. TRPM8 Channels: Advances in Structural Studies and Pharmacological Modulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maingret, F.; Patel, A.J.; Lesage, F.; Lazdunski, M.; Honoré, E. Mechano- or Acid Stimulation, Two Interactive Modes of Activation of the TREK-1 Potassium Channel. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 26691–26696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, H.; Kim, Y.; Kim, D. TREK-2, a New Member of the Mechanosensitive Tandem-pore K+ Channel Family. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 17412–17419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Servin-Vences, M.R.; Moroni, M.; Lewin, G.R.; Poole, K. Direct measurement of TRPV4 and PIEZO1 activity reveals multiple mechanotransduction pathways in chondrocytes. eLife 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sianati, S.; Schroeter, L.; Richardson, J.; Tay, A.; Lamandé, S.R.; Poole, K. Modulating the Mechanical Activation of TRPV4 at the Cell-Substrate Interface. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwan, K.Y.; Glazer, J.M.; Corey, D.P.; Rice, F.L.; Stucky, C.L. TRPA1 Modulates Mechanotransduction in Cutaneous Sensory Neurons. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 4808–4819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, A.O.; Lakk, M.; Rudzitis, C.N.; Križaj, D. TRPV4 and TRPC1 channels mediate the response to tensile strain in mouse Müller cells. Cell Calcium 2022, 104, 102588–102588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugio, S.; Nagasawa, M.; Kojima, I.; Ishizaki, Y.; Shibasaki, K. Transient receptor potential vanilloid 2 activation by focal mechanical stimulation requires interaction with the actin cytoskeleton and enhances growth cone motility. FASEB J. 2016, 31, 1368–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, G.-S.; Lee, B.; Oh, U. Evidence for Mechanosensitive Channel Activity of Tentonin 3/TMEM150C. Neuron 2017, 94, 271–273.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojeda-Alonso, J.; Bégay, V.; Garcia-Contreras, J.A.; Campos-Pérez, A.F.; Purfürst, B.; Lewin, G.R. Lack of evidence for participation of TMEM150C in sensory mechanotransduction. J. Gen. Physiol. 2022, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.O.; Schneider, E.R.; Matson, J.D.; Gracheva, E.O.; Bagriantsev, S.N. TMEM150C/Tentonin3 Is a Regulator of Mechano-gated Ion Channels. Cell Rep. 2018, 23, 701–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Lee, C.J. Transmembrane proteins with unknown function (TMEMs) as ion channels: electrophysiological properties, structure, and pathophysiological roles. Exp. Mol. Med. 2024, 56, 850–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Andolfi, L.; Frattini, F.; Mayer, F.; Lazzarino, M.; Hu, J. Membrane stiffening by STOML3 facilitates mechanosensation in sensory neurons. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, R.M.; Chesler, A.T. Shear elegance: A novel screen uncovers a mechanosensitive GPCR. J. Gen. Physiol. 2018, 150, 907–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.-H.; Ng, K.-F.; Chen, T.-C.; Tseng, W.-Y. Ligands and Beyond: Mechanosensitive Adhesion GPCRs. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhou, S.-H.; Zhang, Q.-Y.; Song, Z.-C.; Liu, W.-W.; Sun, Y.; Wang, M.-W.; Fu, X.-L.; Zhu, K.-K.; Guan, Y.; et al. A force-sensitive adhesion GPCR is required for equilibrioception. Cell Res. 2025, 35, 243–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z. Force sensing GPR133 is essential for 1 normal balance and modulates vestibular hair cell membrane 2 excitability via Gi signaling and CNGA3 coupling. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Z.; Jung, M.; Crow, M.; Mohindra, R.; Maiya, V.; Kaminker, J.S.; Hackos, D.H.; Chandler, G.S.; McCarthy, M.I.; Bhangale, T. Whole genome sequencing across clinical trials identifies rare coding variants in GPR68 associated with chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Genome Med. 2023, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Mathur, J.; Vessières, E.; Hammack, S.; Nonomura, K.; Favre, J.; Grimaud, L.; Petrus, M.; Francisco, A.; Li, J.; et al. GPR68 Senses Flow and Is Essential for Vascular Physiology. Cell 2018, 173, 762–775.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monk, K.R.; Oshima, K.; Jörs, S.; Heller, S.; Talbot, W.S. Gpr126 is essential for peripheral nerve development and myelination in mammals. Development 2011, 138, 2673–2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogha, A.; Benesh, A.E.; Patra, C.; Engel, F.B.; Schöneberg, T.; Liebscher, I.; Monk, K.R. Gpr126 Functions in Schwann Cells to Control Differentiation and Myelination via G-Protein Activation. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 17976–17985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuffer, A. The prion protein is an agonistic ligand of the G protein-coupled receptor Adgrg6. Nature 2016, 536(7617), 464–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayin, N.S.; Frenster, J.D.; Kane, J.R.; Rubenstein, J.; Modrek, A.S.; Baitalmal, R.; Dolgalev, I.; Rudzenski, K.; Scarabottolo, L.; Crespi, D.; et al. GPR133 (ADGRD1), an adhesion G-protein-coupled receptor, is necessary for glioblastoma growth. Oncogenesis 2016, 5, e263–e263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slepak, T.I.; Guyot, M.; Walters, W.; Eichberg, D.G.; Ivan, M.E. Dual role of the adhesion G-protein coupled receptor ADRGE5/CD97 in glioblastoma invasion and proliferation. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299, 105105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, M.; Pedrosa, L.; Paré, L.; Pineda, E.; Bejarano, L.; Martínez, J.; Balasubramaniyan, V.; Ezhilarasan, R.; Kallarackal, N.; Kim, S.-H.; et al. GPR56/ADGRG1 Inhibits Mesenchymal Differentiation and Radioresistance in Glioblastoma. Cell Rep. 2017, 21, 2183–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shashidhar, S.; Lorente, G.; Nagavarapu, U.; Nelson, A.; Kuo, J.; Cummins, J.; Nikolich, K.; Urfer, R.; Foehr, E.D. GPR56 is a GPCR that is overexpressed in gliomas and functions in tumor cell adhesion. Oncogene 2005, 24, 1673–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, O.; Parekh, S.H.; Fletcher, D.A. Reversible stress softening of actin networks. Nature 2007, 445, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seetharaman, S.; Vianay, B.; Roca, V.; Farrugia, A.J.; De Pascalis, C.; Boëda, B.; Dingli, F.; Loew, D.; Vassilopoulos, S.; Bershadsky, A.; et al. Microtubules tune mechanosensitive cell responses. Nat. Mater. 2021, 21, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seetharaman, S.; Etienne-Manneville, S. Microtubules at focal adhesions – a double-edged sword. J. Cell Sci. 2019, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogoda, K.; A Janmey, P. Transmit and protect: The mechanical functions of intermediate filaments. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2023, 85, 102281–102281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndiaye, A.-B.; Koenderink, G.H.; Shemesh, M. Intermediate Filaments in Cellular Mechanoresponsiveness: Mediating Cytoskeletal Crosstalk From Membrane to Nucleus and Back. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 882037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laly, A.C.; Sliogeryte, K.; Pundel, O.J.; Ross, R.; Keeling, M.C.; Avisetti, D.; Waseem, A.; Gavara, N.; Connelly, J.T. The keratin network of intermediate filaments regulates keratinocyte rigidity sensing and nuclear mechanotransduction. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabd6187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, D.; Versaevel, M.; Bruyère, C.; Alaimo, L.; Luciano, M.; Vercruysse, E.; Procès, A.; Gabriele, S. Innovative Tools for Mechanobiology: Unraveling Outside-In and Inside-Out Mechanotransduction. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019, 7, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.-C.; Mei, L. Roles of FAK family kinases in nervous system. Front. Biosci. 2003, 8, s676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita, Y.; Yamashita, T. Axon growth inhibition by RhoA/ROCK in the central nervous system. Front. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 338–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-Cámara, O.; Cores, Á.; López-Alvarado, P.; Menéndez, J.C. Emerging targets in drug discovery against neurodegenerative diseases: Control of synapsis disfunction by the RhoA/ROCK pathway. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 225, 113742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geiger, B.; Spatz, J.P.; Bershadsky, A.D. Environmental sensing through focal adhesions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009, 10, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Guo, S.S.; Fassler, R. Integrin-mediated mechanotransduction. J Cell Biol 2016, 215(4), 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Costell, M.; Fässler, R. Integrin activation by talin, kindlin and mechanical forces. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019, 21, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidone, T.C.; Odde, D.J. Multiscale models of integrins and cellular adhesions. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2023, 80, 102576–102576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangasser, B.L.; Rosenfeld, S.S.; Odde, D.J. Determinants of Maximal Force Transmission in a Motor-Clutch Model of Cell Traction in a Compliant Microenvironment. Biophys. J. 2013, 105, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.E.; Odde, D.J. Traction Dynamics of Filopodia on Compliant Substrates. Science 2008, 322, 1687–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangasser, B.L.; Shamsan, G.A.; Chan, C.E.; Opoku, K.N.; Tüzel, E.; Schlichtmann, B.W.; Kasim, J.A.; Fuller, B.J.; McCullough, B.R.; Rosenfeld, S.S.; et al. Shifting the optimal stiffness for cell migration. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panzetta, V.; De Clemente, C.; Russo, M.; Fusco, S.; Netti, P.A. Insight to motor clutch model for sensing of ECM residual strain. Mechanobiol. Med. 2023, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Xu, F.; Cheng, B. The motor-clutch model in mechanobiology and mechanomedicine. Mechanobiol. Med. 2024, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiMilla, P.; Barbee, K.; Lauffenburger, D. Mathematical model for the effects of adhesion and mechanics on cell migration speed. Biophys. J. 1991, 60, 15–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isomursu, A.; Park, K.-Y.; Hou, J.; Cheng, B.; Mathieu, M.; Shamsan, G.A.; Fuller, B.; Kasim, J.; Mahmoodi, M.M.; Lu, T.J.; et al. Directed cell migration towards softer environments. Nat. Mater. 2022, 21, 1081–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, M.; Isomursu, A.; Ivaska, J. Positive and negative durotaxis – mechanisms and emerging concepts. J. Cell Sci. 2024, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.; Huang, Y. Durotaxis and negative durotaxis: where should cells go? Commun. Biol. 2023, 6, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieuchot, L.; Marteau, J.; Guignandon, A.; Dos Santos, T.; Brigaud, I.; Chauvy, P.-F.; Cloatre, T.; Ponche, A.; Petithory, T.; Rougerie, P.; et al. Curvotaxis directs cell migration through cell-scale curvature landscapes. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cifuentes, L.P.; Athamneh, A.I.M.; Efremov, Y.; Raman, A.; Kim, T.; Suter, D.M. A modified motor-clutch model reveals that neuronal growth cones respond faster to soft substrates. Mol. Biol. Cell 2024, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elosegui-Artola, A.; Trepat, X.; Roca-Cusachs, P. Control of Mechanotransduction by Molecular Clutch Dynamics. Trends Cell Biol. 2018, 28, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiuri, P.; Rupprecht, J.-F.; Wieser, S.; Ruprecht, V.; Bénichou, O.; Carpi, N.; Coppey, M.; De Beco, S.; Gov, N.; Heisenberg, C.-P.; et al. Actin Flows Mediate a Universal Coupling between Cell Speed and Cell Persistence. Cell 2015, 161, 374–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prahl, L.S.; Bangasser, P.F.; Stopfer, L.E.; Hemmat, M.; White, F.M.; Rosenfeld, S.S.; Odde, D.J. Microtubule-Based Control of Motor-Clutch System Mechanics in Glioma Cell Migration. Cell Rep. 2018, 25, 2591–2604.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchison, T.; Kirschner, M. Cytoskeletal dynamics and nerve growth. Neuron 1988, 1, 761–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, E.M.; Van Goor, D.; Forscher, P.; Mogilner, A. Membrane Tension, Myosin Force, and Actin Turnover Maintain Actin Treadmill in the Nerve Growth Cone. Biophys. J. 2012, 102, 1503–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, K.A.; Bacabac, R.G.; Piechocka, I.K.; Koenderink, G.H. Cells Actively Stiffen Fibrin Networks by Generating Contractile Stress. Biophys. J. 2013, 105, 2240–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Liu, A.; Wu, C.; Chen, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, K.; Wei, D.; Sun, J.; Zhou, L.; et al. Static–Dynamic Profited Viscoelastic Hydrogels for Motor-Clutch-Regulated Neurogenesis. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 24463–24476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, T.E.; Schaffran, B.; Broguière, N.; Meyn, L.; Zenobi-Wong, M.; Bradke, F. Axon Growth of CNS Neurons in Three Dimensions Is Amoeboid and Independent of Adhesions. Cell Rep. 2020, 32, 107907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shellard, A.; Weißenbruch, K.; Hampshire, P.A.E.; Stillman, N.R.; Dix, C.L.; Thorogate, R.; Imbert, A.; Charras, G.; Alert, R.; Mayor, R. Frictiotaxis underlies focal adhesion-independent durotaxis. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lämmermann, T.; Bader, B.L.; Monkley, S.J.; Worbs, T.; Wedlich-Söldner, R.; Hirsch, K.; Keller, M.; Förster, R.; Critchley, D.R.; Fässler, R.; et al. Rapid leukocyte migration by integrin-independent flowing and squeezing. Nature 2008, 453, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedl, P.; Entschladen, F.; Conrad, C.; Niggemann, B.; Zänker, K.S. CD4+ T lymphocytes migrating in three-dimensional collagen lattices lack focal adhesions and utilize β1 integrin-independent strategies for polarization, interaction with collagen fibers and locomotion. Eur. J. Immunol. 1998, 28, 2331–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattin, A.-L.; Burden, J.J.; Van Emmenis, L.; Mackenzie, F.E.; Hoving, J.J.; Calavia, N.G.; Guo, Y.; McLaughlin, M.; Rosenberg, L.H.; Quereda, V.; et al. Macrophage-Induced Blood Vessels Guide Schwann Cell-Mediated Regeneration of Peripheral Nerves. Cell 2015, 162, 1127–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paluch, E.K.; Aspalter, I.M.; Sixt, M. Focal Adhesion–Independent Cell Migration. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2016, 32, 469–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergert, M.; Erzberger, A.; Desai, R.A.; Aspalter, I.M.; Oates, A.C.; Charras, G.; Salbreux, G.; Paluch, E.K. Force transmission during adhesion-independent migration. Nat. Cell Biol. 2015, 17, 524–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Y.; Jukkola, P.; Wang, Q.; Esparza, T.; Zhao, Y.; Brody, D.; Gu, C. Polarity of varicosity initiation in central neuron mechanosensation. J. Cell Biol. 2017, 216, 2179–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadzadeh, H.; Smith, D.H.; Shenoy, V.B. Mechanical Effects of Dynamic Binding between Tau Proteins on Microtubules during Axonal Injury. Biophys. J. 2015, 109, 2328–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadzadeh, H.; Smith, D.H.; Shenoy, V.B. Viscoelasticity of Tau Proteins Leads to Strain Rate-Dependent Breaking of Microtubules during Axonal Stretch Injury: Predictions from a Mathematical Model. Biophys. J. 2014, 106, 1123–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotiropoulos, I.; Galas, M.-C.; Silva, J.M.; Skoulakis, E.; Wegmann, S.; Maina, M.B.; Blum, D.; Sayas, C.L.; Mandelkow, E.-M.; Mandelkow, E.; et al. Atypical, non-standard functions of the microtubule associated Tau protein. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2017, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, N.J.; Yao, K.R.; Alford, P.W.; Liao, D. Mechanical injuries of neurons induce tau mislocalization to dendritic spines and tau-dependent synaptic dysfunction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020, 117, 29069–29079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, B.R.; Reed, M.N.; Su, J.; Penrod, R.D.; Kotilinek, L.A.; Grant, M.K.; Pitstick, R.; Carlson, G.A.; Lanier, L.M.; Yuan, L.-L.; et al. Tau Mislocalization to Dendritic Spines Mediates Synaptic Dysfunction Independently of Neurodegeneration. Neuron 2010, 68, 1067–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, C.; Ma, J.; Ray, W.J.; Frost, B. Pathogenic tau decreases nuclear tension in cultured neurons. Front. Aging 2023, 4, 1058968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinnathambi, S. Nuclear Tau accumulation in Alzheimer’s disease. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol 2025, 143, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Essepian, N. Tau Oligomerization Drives Neurodegeneration via Nuclear Membrane Invagination and Lamin B Receptor Binding in Alzheimer’s disease. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frost, B.; Bardai, F.H.; Feany, M.B. Lamin Dysfunction Mediates Neurodegeneration in Tauopathies. Curr. Biol. 2016, 26, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paonessa, F.; Evans, L.D.; Solanki, R.; Larrieu, D.; Wray, S.; Hardy, J.; Jackson, S.P.; Livesey, F.J. Microtubules Deform the Nuclear Membrane and Disrupt Nucleocytoplasmic Transport in Tau-Mediated Frontotemporal Dementia. Cell Rep. 2019, 26, 582–593.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congdon, E.E.; Ji, C.; Tetlow, A.M.; Jiang, Y.; Sigurdsson, E.M. Tau-targeting therapies for Alzheimer disease: current status and future directions. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2023, 19, 715–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, H.; Smith, J.; Campbell, T.; Clark, J.; La Rocca, R.; Paonessa, F.; Sitnikov, S.; Evans, M.; Maycox, P.; Livesey, F.J. A phenotypic screen for novel small molecules that correct tau-mediated pathologies in human frontotemporal dementia neurons. Alzheimer's Dement. 2025, 21, e70620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisleni, A.; Bonilla-Quintana, M.; Crestani, M.; Lavagnino, Z.; Galli, C.; Rangamani, P.; Gauthier, N.C. Mechanically induced topological transition of spectrin regulates its distribution in the mammalian cell cortex. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaim, G.L. Axonal Mechanotransduction Drives Cytoskeletal Responses to Physiological Mechanical Forces. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanghvi-Shah, R.; Weber, G.F. Intermediate Filaments at the Junction of Mechanotransduction, Migration, and Development. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2017, 5, 81–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantalacci, S.; Tapon, N.; Léopold, P. The Salvador partner Hippo promotes apoptosis and cell-cycle exit in Drosophila. Nat. Cell Biol. 2003, 5, 921–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.; Hu, Y.; Lan, T.; Guan, K.-L.; Luo, T.; Luo, M. The Hippo signalling pathway and its implications in human health and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kono, K.; Tamashiro, D.A.A.; Alarcon, V.B. Inhibition of RHO–ROCK signaling enhances ICM and suppresses TE characteristics through activation of Hippo signaling in the mouse blastocyst. Dev. Biol. 2014, 394, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihajlović, A.I.; Bruce, A.W. Rho-associated protein kinase regulates subcellular localisation of Angiomotin and Hippo-signalling during preimplantation mouse embryo development. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2016, 33, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, K.C.; Moroishi, T.; Meng, Z.; Jeong, H.-S.; Plouffe, S.W.; Sekido, Y.; Han, J.; Park, H.W.; Guan, K.-L. Regulation of Hippo pathway transcription factor TEAD by p38 MAPK-induced cytoplasmic translocation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2017, 19, 996–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Xia, W.; Fisher, G.J.; Voorhees, J.J.; Quan, T. YAP/TAZ regulates TGF-β/Smad3 signaling by induction of Smad7 via AP-1 in human skin dermal fibroblasts. Cell Commun. Signal. 2018, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Yu, C.; Song, Z.; Zou, H.; Xu, X.; Liu, J. Expression of MicroRNA-29a Regulated by Yes-Associated Protein Modulates the Neurite Outgrowth in N2a Cells. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampayo, R.G.; Sakamoto, M.; Wang, M.; Kumar, S.; Schaffer, D.V. Mechanosensitive stem cell fate choice is instructed by dynamic fluctuations in activation of Rho GTPases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2023, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mana-Capelli, S.; Paramasivam, M.; Dutta, S.; McCollum, D. Angiomotins link F-actin architecture to Hippo pathway signaling. Mol. Biol. Cell 2014, 25, 1676–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, I.; McCollum, D. Control of cellular responses to mechanical cues through YAP/TAZ regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 17693–17706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaltsman, Y.; Masuko, S.; Bensen, J.J.; Kiessling, L.L. Angiomotin Regulates YAP Localization during Neural Differentiation of Human Pluripotent Stem Cells. Stem Cell Rep. 2019, 12, 869–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hata, S.; Hirayama, J.; Kajiho, H.; Nakagawa, K.; Hata, Y.; Katada, T.; Furutani-Seiki, M.; Nishina, H. A Novel Acetylation Cycle of Transcription Co-activator Yes-associated Protein That Is Downstream of Hippo Pathway Is Triggered in Response to SN2 Alkylating Agents. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 22089–22098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Yu, B.; Peng, Z.; Zhang, J.; Sun, J.; Yang, B.; Xu, L.; Luo, D. PRMT1-mediated arginine methylation promotes YAP activation and hepatocellular carcinoma proliferation. FEBS Open Bio 2024, 14, 2104–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; He, P.; Yang, L.; Gong, J.; Qin, R.; Wang, M. Posttranslational modifications of YAP/TAZ: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2025, 30, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzolin, L.; Panciera, T.; Soligo, S.; Enzo, E.; Bicciato, S.; Dupont, S.; Bresolin, S.; Frasson, C.; Basso, G.; Guzzardo, V.; et al. YAP/TAZ Incorporation in the β-Catenin Destruction Complex Orchestrates the Wnt Response. Cell 2014, 158, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konsavage, W.M.; Yochum, G.S. Intersection of Hippo/YAP and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways. Acta Biochim. et Biophys. Sin. 2012, 45, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Peng, B.; Chen, G.; Pes, M.G.; Ribback, S.; Ament, C.; Xu, H.; Pal, R.; Rodrigues, P.M.; Banales, J.M.; et al. YAP Accelerates Notch-Driven Cholangiocarcinogenesis via mTORC1 in Mice. Am. J. Pathol. 2021, 191, 1651–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, C.G.; Ng, Y.L.D.; Lam, W.-L.M.; Plouffe, S.W.; Guan, K.-L. The Hippo pathway effectors YAP and TAZ promote cell growth by modulating amino acid signaling to mTORC1. Cell Res. 2015, 25, 1299–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, R.; Gong, J.; Wu, L.; Wang, L.; Zhang, B.; Liang, G.; Zheng, H.; Xiao, H. MAPK and Hippo signaling pathways crosstalk via the RAF-1/MST-2 interaction in malignant melanoma. Oncol. Rep. 2017, 38, 1199–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-T.; Ding, J.-Y.; Li, M.-Y.; Yeh, T.-S.; Wang, T.-W.; Yu, J.-Y. YAP regulates neuronal differentiation through Sonic hedgehog signaling pathway. Exp. Cell Res. 2012, 318, 1877–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.A.; Chen, S.; Li, Z.; Lee, C.H.; Mirzaa, G.; Dobyns, W.B.; Ross, M.E.; Zhang, J.; Shi, S.-H. PARD3 dysfunction in conjunction with dynamic HIPPO signaling drives cortical enlargement with massive heterotopia. Genes Dev. 2018, 32, 763–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavado, A.; Gangwar, R.; Paré, J.; Wan, S.; Fan, Y.; Cao, X. YAP/TAZ maintain the proliferative capacity and structural organization of radial glial cells during brain development. Dev. Biol. 2021, 480, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Yang, J.; He, M.; Yu, X.-Y.; Lee, C.H.; Yang, Z.; Joyner, A.L.; Anderson, K.V.; Zhang, J.; Tsou, M.-F.B.; et al. Centrosome anchoring regulates progenitor properties and cortical formation. Nature 2020, 580, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, L.J.; Park, R.; Lee, M.J.; Terry, B.K.; Lee, D.J.; Kim, H.; Cho, S.-H.; Kim, S. Yap/Taz are required for establishing the cerebellar radial glia scaffold and proper foliation. Dev. Biol. 2020, 457, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavado, A.; Park, J.Y.; Paré, J.; Finkelstein, D.; Pan, H.; Xu, B.; Fan, Y.; Kumar, R.P.; Neale, G.; Kwak, Y.D.; et al. The Hippo Pathway Prevents YAP/TAZ-Driven Hypertranscription and Controls Neural Progenitor Number. Dev. Cell 2018, 47, 576–591.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leipzig, N.D.; Shoichet, M.S. The effect of substrate stiffness on adult neural stem cell behavior. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 6867–6878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musah, S.; Wrighton, P.J.; Zaltsman, Y.; Zhong, X.; Zorn, S.; Parlato, M.B.; Hsiao, C.; Palecek, S.P.; Chang, Q.; Murphy, W.L.; et al. Substratum-induced differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells reveals the coactivator YAP is a potent regulator of neuronal specification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2014, 111, 13805–13810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, Y.; Iwashita, M.; Lee, W.; Uchimura, K.; Kosodo, Y. A Shift in Tissue Stiffness During Hippocampal Maturation Correlates to the Pattern of Neurogenesis and Composition of the Extracellular Matrix. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 709620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, S. Role of YAP/TAZ in mechanotransduction. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Byun, S.-H.; Park, S.; Kim, J.; Kim, I.; Ha, S.; Kwon, M.; Yoon, K. YAP/TAZ enhance mammalian embryonic neural stem cell characteristics in a Tead-dependent manner. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 458, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Pfaff, S.L.; Gage, F.H. YAP regulates neural progenitor cell number via the TEA domain transcription factor. Genes Dev. 2008, 22, 3320–3334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Hung, T.; Wang, T.; Lee, Y.; Wang, T.; Yu, J. YAP maintains the production of intermediate progenitor cells and upper-layer projection neurons in the mouse cerebral cortex. Dev. Dyn. 2021, 251, 846–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, A.; Arha, M.; Choudhary, S.; Ashton, R.S.; Bhatia, S.R.; Schaffer, D.V.; Kane, R.S. The influence of hydrogel modulus on the proliferation and differentiation of encapsulated neural stem cells. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 4695–4699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattiassi, S.; Conner, A.A.; Feng, F.; Goh, E.L.K.; Yim, E.K.F. The Combined Effects of Topography and Stiffness on Neuronal Differentiation and Maturation Using a Hydrogel Platform. Cells 2023, 12, 934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Zhang, Q.; Gao, S.; Song, Q.; Huang, R.; Wang, L.; Liu, L.; Dai, J.; Tang, M.; Cheng, G. Three-dimensional graphene foam as a biocompatible and conductive scaffold for neural stem cells. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karzbrun, E.; Khankhel, A.H.; Megale, H.C.; Glasauer, S.M.K.; Wyle, Y.; Britton, G.; Warmflash, A.; Kosik, K.S.; Siggia, E.D.; Shraiman, B.I.; et al. Human neural tube morphogenesis in vitro by geometric constraints. Nature 2021, 599, 268–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saade, M.; Martí, E. Early spinal cord development: from neural tube formation to neurogenesis. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2025, 26, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galea, G.L. Biomechanical coupling facilitates spinal neural tube closure in mouse embryos. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017, 114(26), E5177–E5186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alasaadi, D.N.; Alvizi, L.; Hartmann, J.; Stillman, N.; Moghe, P.; Hiiragi, T.; Mayor, R. Competence for neural crest induction is controlled by hydrostatic pressure through Yap. Nat. Cell Biol. 2024, 26, 530–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumbiner, B.M.; Kim, N.-G. The Hippo-YAP signaling pathway and contact inhibition of growth. J. Cell Sci. 2014, 127, 709–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, S.B.; Xue, S.-L.; Ding, S.; Winkel, A.K.; Baldwin, O.; Dwarakacherla, S.; Franze, K.; Hannezo, E.; Xiong, F. Differential tissue deformability underlies fluid pressure-driven shape divergence of the avian embryonic brain and spinal cord. Dev. Cell 2025, 60, 2237–2247.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, A.; Mayor, R. Mechanisms of Neural Crest Migration. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2018, 52, 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barriga, E.H.; Franze, K.; Charras, G.; Mayor, R. Tissue stiffening coordinates morphogenesis by triggering collective cell migration in vivo. Nature 2018, 554, 523–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarpa, E.; Szabó, A.; Bibonne, A.; Theveneau, E.; Parsons, M.; Mayor, R. Cadherin Switch during EMT in Neural Crest Cells Leads to Contact Inhibition of Locomotion via Repolarization of Forces. Dev. Cell 2015, 34, 421–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancaster, M.A.; Renner, M.; Martin, C.-A.; Wenzel, D.; Bicknell, L.S.; Hurles, M.E.; Homfray, T.; Penninger, J.M.; Jackson, A.P.; Knoblich, J.A. Cerebral organoids model human brain development and microcephaly. Nature 2013, 501, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichmüller, O.L.; Knoblich, J.A. Human cerebral organoids — a new tool for clinical neurology research. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2022, 18, 661–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z. Organoids. Nat Rev Methods Primers 2022, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birtele, M.; Lancaster, M.; Quadrato, G. Modelling human brain development and disease with organoids. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 26, 389–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pașca, S.P.; Arlotta, P.; Bateup, H.S.; Camp, J.G.; Cappello, S.; Gage, F.H.; Knoblich, J.A.; Kriegstein, A.R.; Lancaster, M.A.; Ming, G.-L.; et al. A nomenclature consensus for nervous system organoids and assembloids. Nature 2022, 609, 907–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Lancaster, M.A.; Castanon, R.; Nery, J.R.; Knoblich, J.A.; Ecker, J.R. Cerebral Organoids Recapitulate Epigenomic Signatures of the Human Fetal Brain. Cell Rep. 2016, 17, 3369–3384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujillo, C.A.; Gao, R.; Negraes, P.D.; Gu, J.; Buchanan, J.; Preissl, S.; Wang, A.; Wu, W.; Haddad, G.G.; Chaim, I.A.; et al. Complex Oscillatory Waves Emerging from Cortical Organoids Model Early Human Brain Network Development. Cell Stem Cell 2019, 25, 558–569.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.-J.; Elahi, L.S.; Pașca, A.M.; Marton, R.M.; Gordon, A.; Revah, O.; Miura, Y.; Walczak, E.M.; Holdgate, G.M.; Fan, H.C.; et al. Reliability of human cortical organoid generation. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishihara, K. Reconstitution of a Patterned Neural Tube from Single Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells. Methods Mol Biol 2017, 1597, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Meinhardt, A.; Eberle, D.; Tazaki, A.; Ranga, A.; Niesche, M.; Wilsch-Bräuninger, M.; Stec, A.; Schackert, G.; Lutolf, M.; Tanaka, E.M. 3D Reconstitution of the Patterned Neural Tube from Embryonic Stem Cells. Stem Cell Rep. 2014, 3, 987–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, C. Production of Neuroepithelial Organoids from Human-Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells for Mimicking Early Neural Tube Development. Methods Mol Biol 2025, 2951, 111–123. [Google Scholar]

- Fattah, A.R.A.; Daza, B.; Rustandi, G.; Berrocal-Rubio, M.Á.; Gorissen, B.; Poovathingal, S.; Davie, K.; Barrasa-Fano, J.; Cóndor, M.; Cao, X.; et al. Actuation enhances patterning in human neural tube organoids. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnard, C.; Navaratnam, N.; Ghosh, K.; Chan, P.W.; Tan, T.T.; Pomp, O.; Ng, A.Y.J.; Tohari, S.; Changede, R.; Carling, D.; et al. A loss-of-function NUAK2 mutation in humans causes anencephaly due to impaired Hippo-YAP signaling. J. Exp. Med. 2020, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffat, A.; Schuurmans, C. The Control of Cortical Folding: Multiple Mechanisms, Multiple Models. Neurosci. 2023, 30, 704–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del-Valle-Anton, L.; Amin, S.; Cimino, D.; Neuhaus, F.; Dvoretskova, E.; Fernández, V.; Babal, Y.K.; Garcia-Frigola, C.; Prieto-Colomina, A.; Murcia-Ramón, R.; et al. Multiple parallel cell lineages in the developing mammalian cerebral cortex. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadn9998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, V.; Borrell, V. Developmental mechanisms of gyrification. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2023, 80, 102711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akula, S.K.; Exposito-Alonso, D.; Walsh, C.A. Shaping the brain: The emergence of cortical structure and folding. Dev. Cell 2023, 58, 2836–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, K.E.; Kroenke, C.D.; Bayly, P.V. Mechanical stress connects cortical folding to fiber organization in the developing brain. Trends Neurosci. 2025, 48, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, G.; Knutsen, A.K.; Dikranian, K.; Kroenke, C.D.; Bayly, P.V.; Taber, L.A. Axons Pull on the Brain, But Tension Does Not Drive Cortical Folding. J. Biomech. Eng. 2010, 132, 071013–071013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tallinen, T.; Chung, J.Y.; Biggins, J.S.; Mahadevan, L. Gyrification from constrained cortical expansion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2014, 111, 12667–12672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronan, L.; Voets, N.; Rua, C.; Alexander-Bloch, A.; Hough, M.; Mackay, C.; Crow, T.J.; James, A.; Giedd, J.N.; Fletcher, P.C. Differential Tangential Expansion as a Mechanism for Cortical Gyrification. Cereb. Cortex 2013, 24, 2219–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayly, P.V.; Okamoto, R.J.; Xu, G.; Shi, Y.; A Taber, L. A cortical folding model incorporating stress-dependent growth explains gyral wavelengths and stress patterns in the developing brain. Phys. Biol. 2013, 10, 016005–016005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianchi, L.M. The Developing Brain and its Connections; CRC Press, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Developmental Neurobiology, Fourth Edition ed.; Kluwer Academic.

- Bianchi, L. Developmental Neurobiology; Garland Science, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- O’lEary, D.D.; Sahara, S. Genetic regulation of arealization of the neocortex. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2008, 18, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puelles, L. Pallial and subpallial derivatives in the embryonic chick and mouse telencephalon, traced by the expression of the genes Dlx-2, Emx-1, Nkx-2.1, Pax-6, and Tbr-1. J Comp Neurol 2000, 424(3), 409–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, C.d.J.; Borrell, V. Genetic maps and patterns of cerebral cortex folding. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2017, 49, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaike, M.; Hatakeyama, J.; Nakashima, Y.; Shimamura, K. Measuring intraventricular pressure in developing mouse embryos: Uncovering a repetitive mechanical cue for brain development. Dev. Growth Differ. 2025, 67, 230–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingeberg, M.B.; Van Houten, E.; Zwanenburg, J.J.M. Estimating the viscoelastic properties of the human brain at 7 T MRI using intrinsic MRE and nonlinear inversion. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2023, 44, 6575–6591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIlvain, G.; Schneider, J.M.; A Matyi, M.; McGarry, M.D.; Qi, Z.; Spielberg, J.M.; Johnson, C.L. Mapping brain mechanical property maturation from childhood to adulthood. NeuroImage 2022, 263, 119590–119590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasaka, A.; Miyata, T. Comparison of the Mechanical Properties Between the Convex and Concave Inner/Apical Surfaces of the Developing Cerebrum. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, X.; Shi, S. Neocortical neurogenesis and neuronal migration. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Dev. Biol. 2012, 2, 443–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Bendito, G.; Cautinat, A.; Sánchez, J.A.; Bielle, F.; Flames, N.; Garratt, A.N.; Talmage, D.A.; Role, L.W.; Charnay, P.; Marín, O.; et al. Tangential Neuronal Migration Controls Axon Guidance: A Role for Neuregulin-1 in Thalamocortical Axon Navigation. Cell 2006, 125, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIlvain, G.; Schwarb, H.; Cohen, N.J.; Telzer, E.H.; Johnson, C.L. Mechanical properties of the in vivo adolescent human brain. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2018, 34, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakic, P. Evolution of the neocortex: a perspective from developmental biology. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2009, 10, 724–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowery, L.A. D. Van Vactor, The trip of the tip: understanding the growth cone machinery. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2009, 10(5), 332–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.X.; Yurke, B.; Firestein, B.L.; Langrana, N.A. Neurite Outgrowth on a DNA Crosslinked Hydrogel with Tunable Stiffnesses. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2008, 36, 1565–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, L.L.; Aranda-Espinoza, H. Cortical Neuron Outgrowth is Insensitive to Substrate Stiffness. Cell. Mol. Bioeng. 2010, 3, 398–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, D.; Rosoff, W.J.; Jiang, J.; Geller, H.M.; Urbach, J.S. Strength in the Periphery: Growth Cone Biomechanics and Substrate Rigidity Response in Peripheral and Central Nervous System Neurons. Biophys. J. 2012, 102, 452–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Li, D.; Farrelly, O.; Miles, L.; Li, F.; Kim, S.E.; Lo, T.Y.; Wang, F.; Li, T.; Thompson-Peer, K.L.; et al. The Mechanosensitive Ion Channel Piezo Inhibits Axon Regeneration. Neuron 2019, 102, 373–389.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.J.; Pillai, E.K.; Dimov, I.B.; Foster, S.K.; E Holt, C.; Franze, K. Rapid changes in tissue mechanics regulate cell behaviour in the developing embryonic brain. eLife 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estévez-Priego, E.; Moreno-Fina, M.; Monni, E.; Kokaia, Z.; Soriano, J.; Tornero, D. Long-term calcium imaging reveals functional development in hiPSC-derived cultures comparable to human but not rat primary cultures. Stem Cell Rep. 2022, 18, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Wagenaar, D.; Pine, J.; Potter, S.M. An extremely rich repertoire of bursting patterns during the development of cortical cultures. BMC Neurosci. 2006, 7, 11–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]