Submitted:

14 December 2025

Posted:

15 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cells and Culture Conditions

2.2. Isolation of Prodigiosin and Cytochalasin B-Induced Membrane Vesicles

2.3. Loading of MVs with Prodigiosin

2.4. Protein Concentration Measurement

2.5. Hydrodynamic Diameters and Zeta-Potential Analysis

2.6. Microscopy

2.7. Flow Cytometry Analysis

2.8. Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA)

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

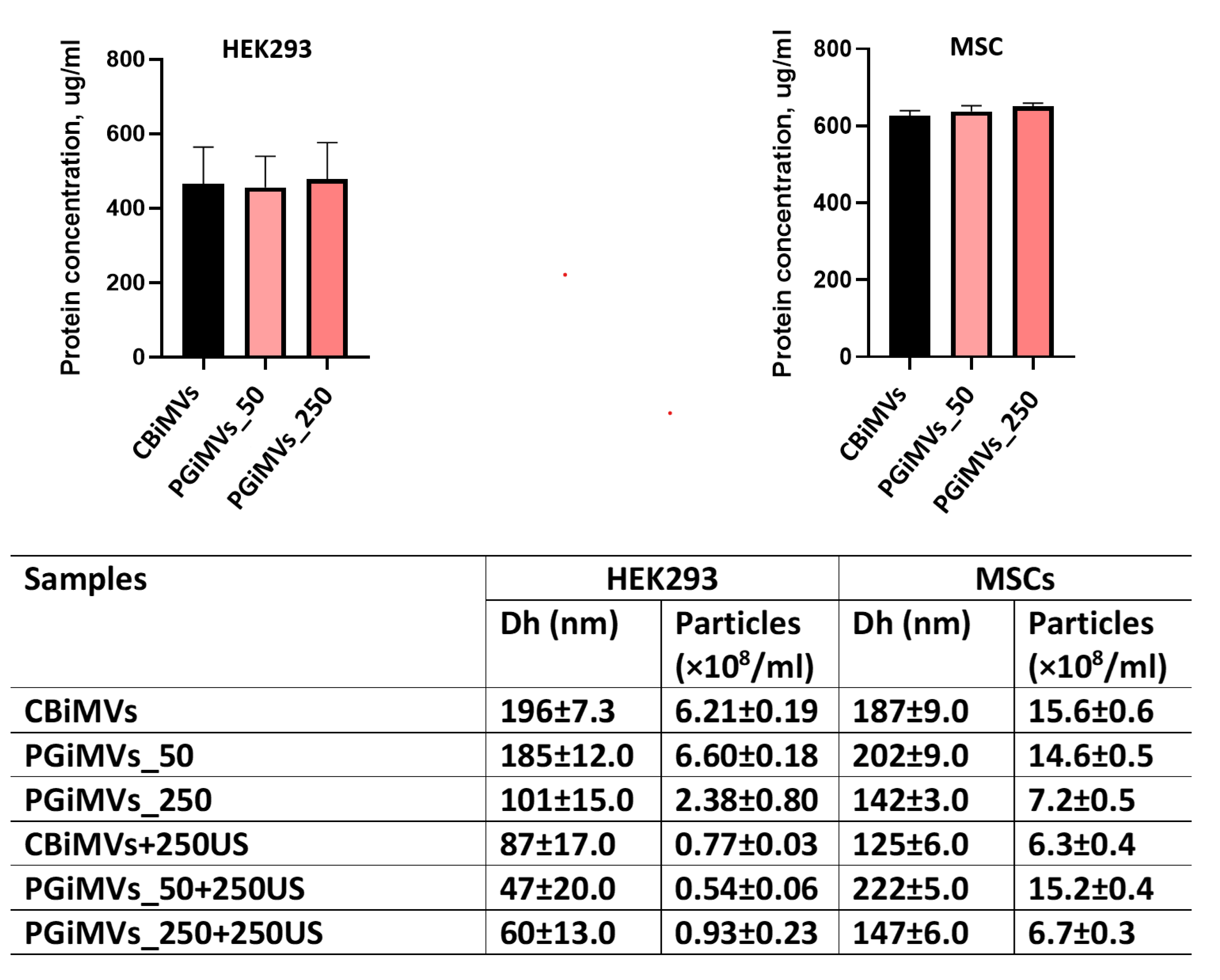

3.1. Quantitative Characterization of Microvesicles

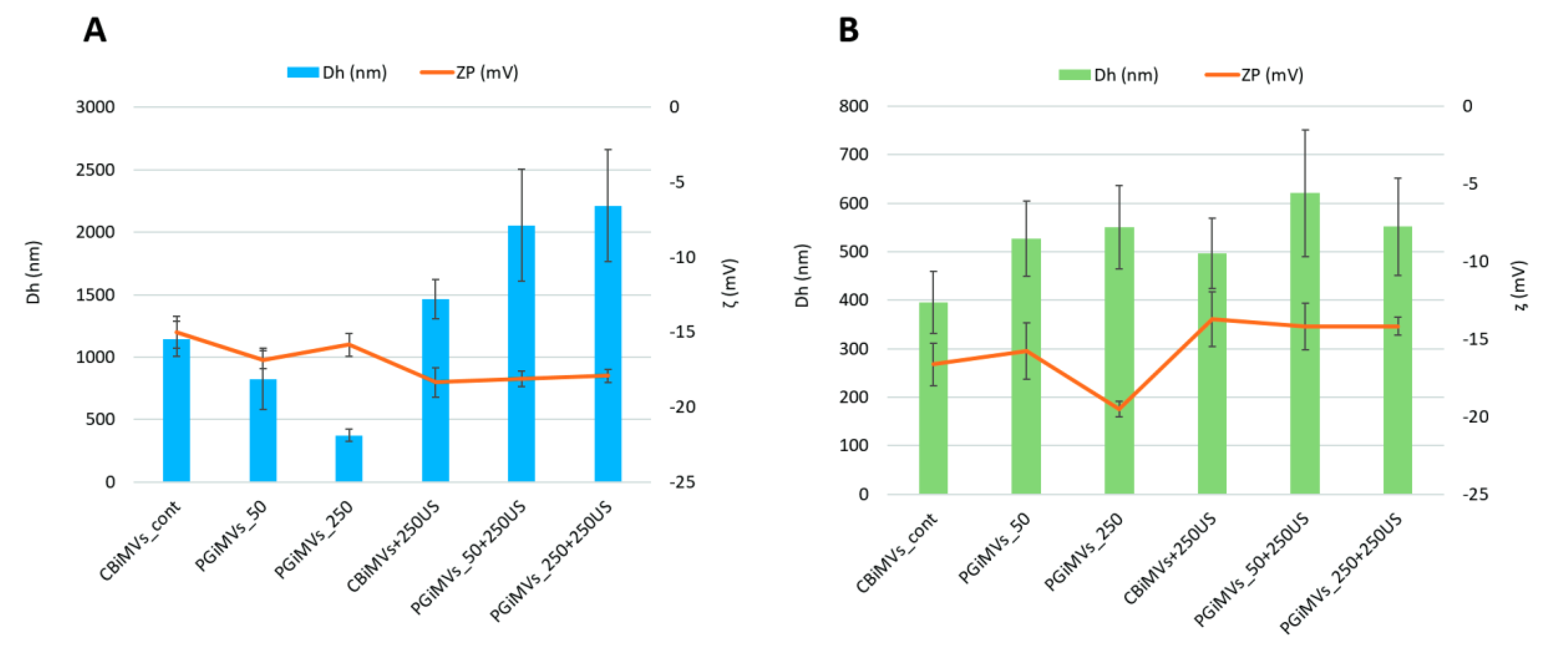

3.2. Hydrodynamic Diameters (Dh) and Zeta Potentials (ζ) of MVs Analysis

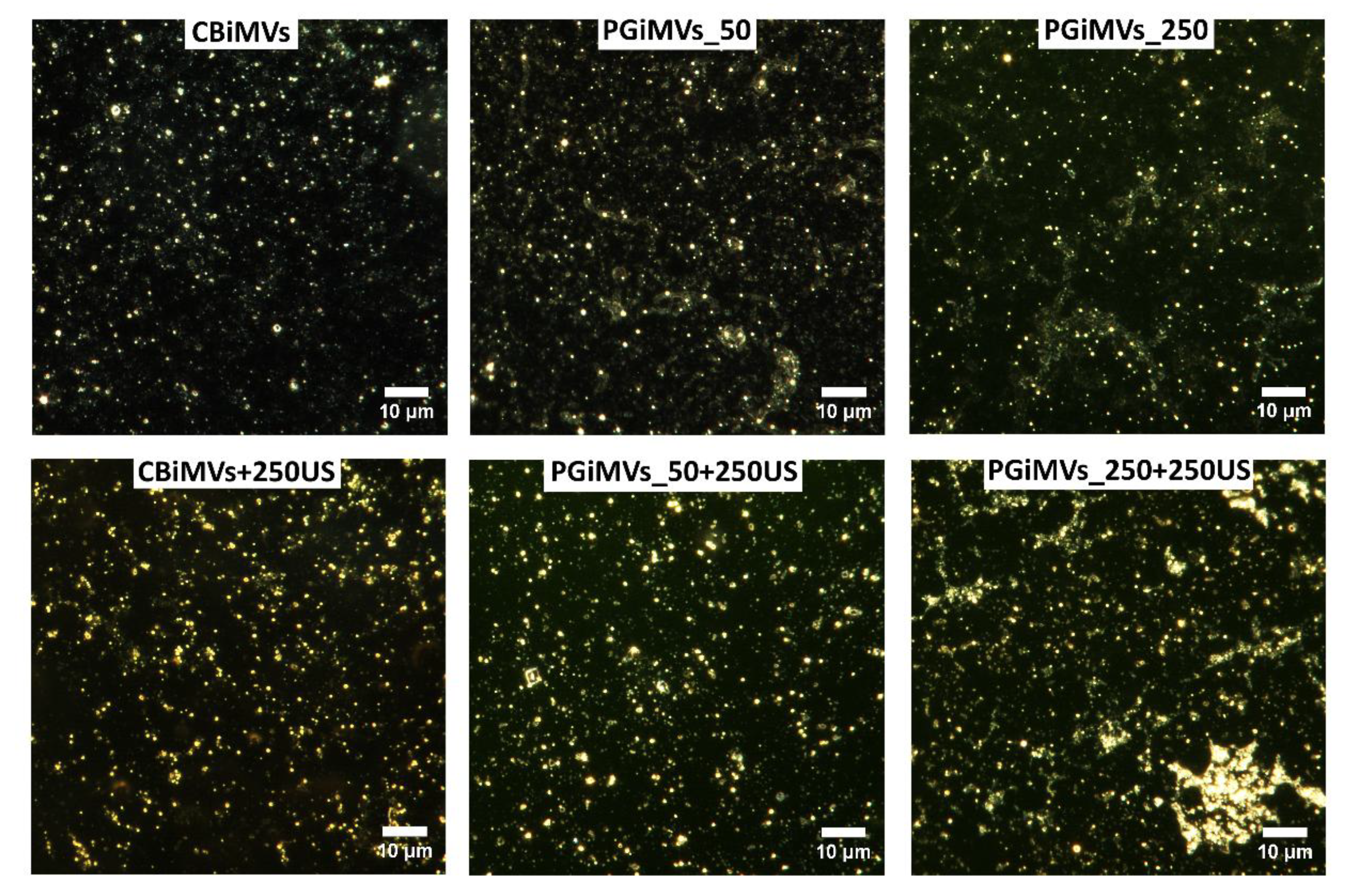

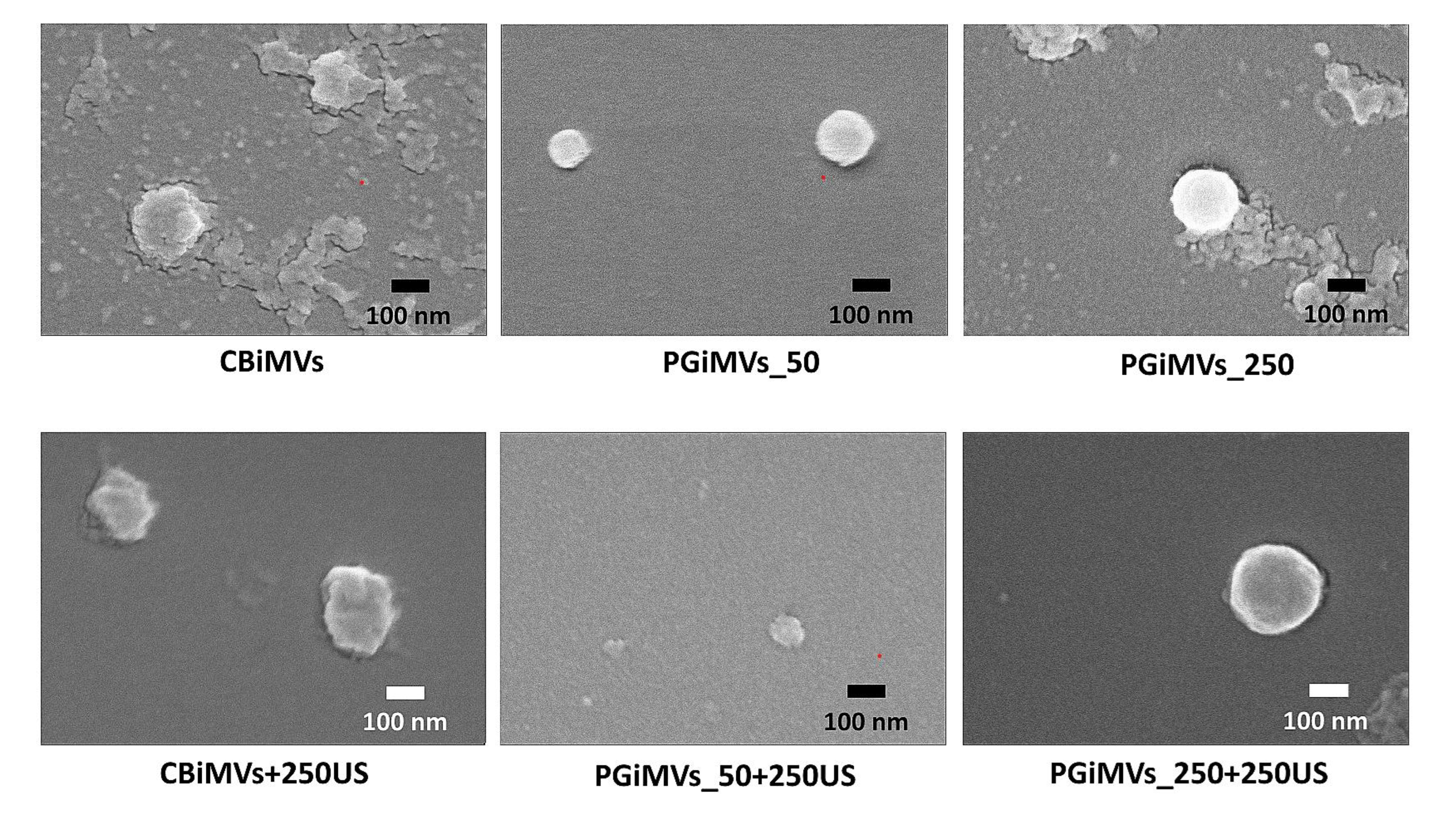

3.3. Visualisation of MVs

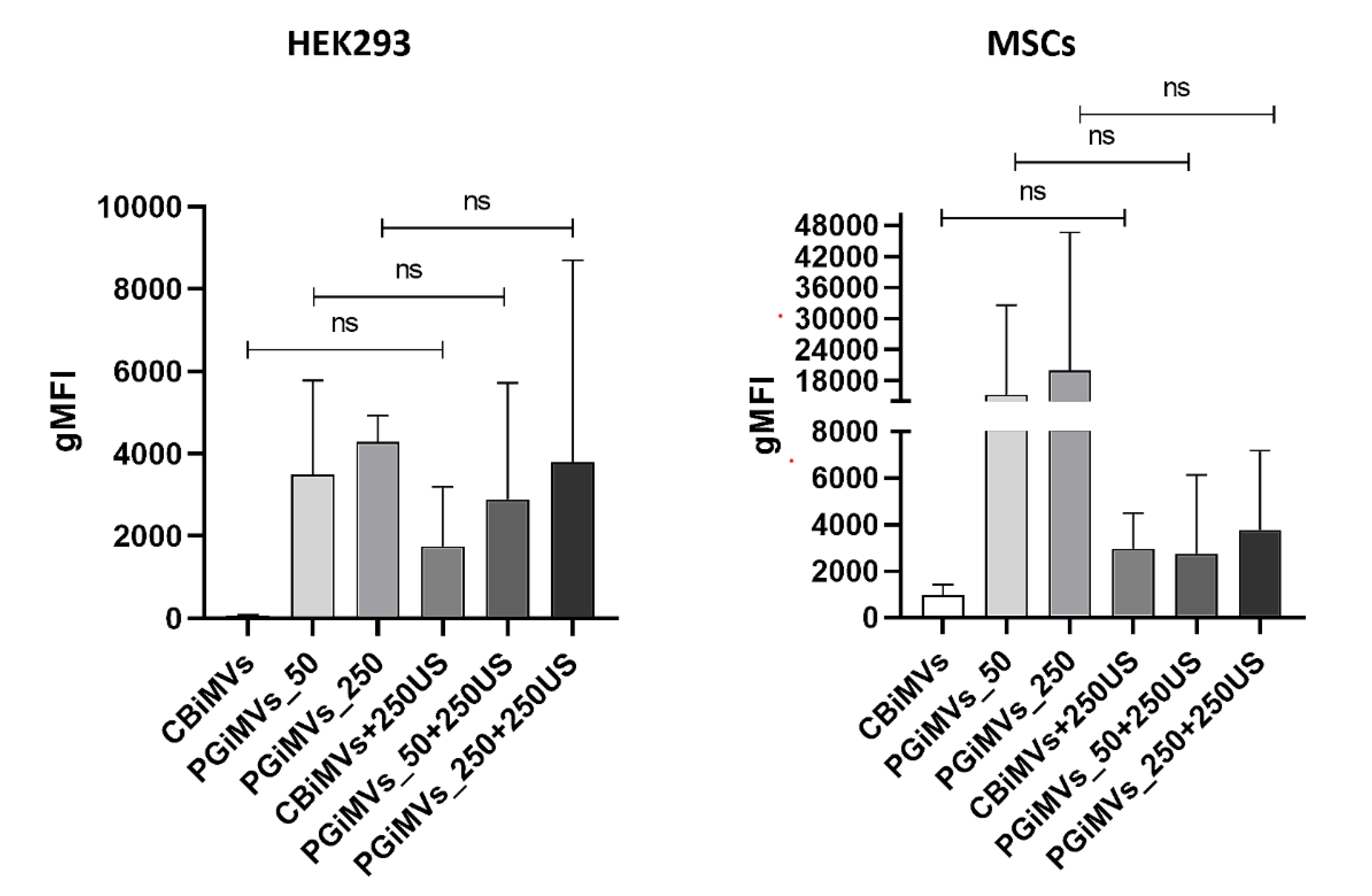

3.4. Flow Cytometry Analysis

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guryanov, I.; Naumenko, E. Bacterial Pigment Prodigiosin as Multifaceted Compound for Medical and Industrial Application. Appl. Microbiol. 2024, 4, 1702–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.-J.; Bae, J.; Lee, D.-S.; Kim, C.-H.; Kim, J.-S.; Kim, S.-W.; Hong, S.-I. Purification and Characterization of Prodigiosin Produced by Integrated Bioreactor from Serratia Sp. KH-95. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2006, 101, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guryanov, I. D.; Karamova, N. S.; Yusupova, D. V.; Gnezdilov, O. I.; Koshkarova, L. A. The bacterial pigment prodigiosin and its genotoxic properties. Bioorganic Chemistry 2013, 39, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, H.; Li, Y.; Lu, X.-L.; Yan, J.; Liu, X.-R.; Yin, Q. Prodigiosin Derived from Chromium-Resistant Serratia Sp. Prevents Inflammation and Modulates Gut Microbiota Homeostasis in DSS-Induced Colitis Mice. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 116, 109800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anwar, M.M.; Albanese, C.; Hamdy, N.M.; Sultan, A.S. Rise of the Natural Red Pigment ‘Prodigiosin’ as an Immunomodulator in Cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2022, 22, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakashima, T.; Iwashita, T.; Fujita, T.; Sato, E.; Niwano, Y.; Kohno, M.; Kuwahara, S.; Harada, N.; Takeshita, S.; Oda, T. A Prodigiosin Analogue Inactivates NADPH Oxidase in Macrophage Cells by Inhibiting Assembly of P47phox and Rac. J. Biochem. 2007, 143, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.B.; Kim, H.M.; Kim, Y.H.; Lee, C.W.; Jang, E.-S.; Son, K.H.; Kim, S.U.; Kim, Y.K. T-Cell Specific Immunosuppression by Prodigiosin Isolated from Serratia Marcescens. Int. J. Immunopharmacol. 1998, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, F.; Hou, D.-X.; Xu, J.; Zhao, X.; Yang, F.; Feng, X. Prodigiosin Promotes Nrf2 Activation to Inhibit Oxidative Stress Induced by Microcystin-LR in HepG2 Cells. Toxins (Basel) 2019, 11, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.-R.; Chen, Y.-H.; Tseng, F.-J.; Weng, C.-F. The Production and Bioactivity of Prodigiosin: Quo Vadis? Drug Discov. Today 2020, 25, 828–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimyon, Ö.; Das, T.; Ibugo, A.I.; Kutty, S.K.; Ho, K.K.; Tebben, J.; Kumar, N.; Manefield, M. Serratia Secondary Metabolite Prodigiosin Inhibits Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Biofilm Development by Producing Reactive Oxygen Species That Damage Biological Molecules. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melvin, M.S.; Tomlinson, J.T.; Saluta, G.R.; Kucera, G.L.; Lindquist, N.; Manderville, R.A. Double-Strand DNA Cleavage by Copper·Prodigiosin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 6333–6334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lins, J.C.L.; Melo, M.E.B.D.E.; do Nascimento, S.C.; Adam, M.L. Differential Genomic Damage in Different Tumor Lines Induced by Prodigiosin. Anticancer Res. 2015, 35 6, 3325–3332. [Google Scholar]

- Guryanov, I.; Naumenko, E.; Akhatova, F.; Lazzara, G.; Cavallaro, G.; Nigamatzyanova, L.; Fakhrullin, R. Selective Cytotoxic Activity of Prodigiosin@halloysite Nanoformulation. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.-A.; Han, T.-H.; Haam, K.; Lee, K.-S.; Kim, J.; Han, T.-S.; Lee, M.-S.; Ban, H.S. Prodigiosin Regulates Cancer Metabolism through Interaction with GLUT1. Nat. Prod. Res. 2025, 39, 5264–5271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElBakary, N.M.; Anees, L.M.; Said Shahat, A.; Mesalam, N.M. A Promising Natural Red Pigment “Prodigiosin” Sensitizes Colon Cancer Cells to Ionizing Radiation, Induces Apoptosis, and Impedes MAPK/TNF-α/NLRP3 Signaling Pathway. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2025, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llagostera, E.; Soto-Cerrato, V.; Joshi, R.; Montaner, B.; Gimenez-Bonaf??, P.; P??rez-Tom??s, R. High Cytotoxic Sensitivity of the Human Small Cell Lung Doxorubicin-Resistant Carcinoma (GLC4/ADR) Cell Line to Prodigiosin through Apoptosis Activation. Anticancer. Drugs 2005, 16, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumenko, E.; Guryanov, I.; Gomzikova, M. Drug Delivery Nano-Platforms for Advanced Cancer Therapy. Sci. Pharm. 2024, 92, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidi, M.; Jebali, A. Liposomal Prodigiosin and Plasmid Encoding Serial GCA Nucleotides Reduce Inflammation in Microglial and Astrocyte Cells by ATM/ATR Signaling. J. Neuroimmunol. 2019, 326, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, W.A.; El-Nekhily, N.A.; Mahmoud, H.E.; Hussein, A.A.; Sabra, S.A. Prodigiosin/Celecoxib-Loaded into Zein/Sodium Caseinate Nanoparticles as a Potential Therapy for Triple Negative Breast Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anjum, N.; Wani, S.M.; Padder, S.A.; Habib, S.; Ayaz, Q.; Mustafa, S.; Amin, T.; Malik, A.R.; Hussain, S.Z. Optimizing Prodigiosin Nanoencapsulation in Different Wall Materials by Freeze Drying: Characterization and Release Kinetics. Food Chem. 2025, 477, 143587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Li, D.; Cheng, G.; Zhang, B.; Han, J.; Chen, J.; Wang, B.; Li, M.; Xiao, T.; Zhang, J.; et al. Targeted Delivery Prodigiosin to Choriocarcinoma by Peptide-Guided Dendrigraft Poly-l-Lysines Nanoparticles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastegari, B.; Karbalaei-Heidari, H.R.; Zeinali, S.; Sheardown, H. The Enzyme-Sensitive Release of Prodigiosin Grafted β-Cyclodextrin and Chitosan Magnetic Nanoparticles as an Anticancer Drug Delivery System: Synthesis, Characterization and Cytotoxicity Studies. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces 2017, 158, 589–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darya, G.H.; Zare, O.; Karbalaei-Heidari, H.R.; Zeinali, S.; Sheardown, H.; Rastegari, B. Enzyme-Responsive Mannose-Grafted Magnetic Nanoparticles for Breast and Liver Cancer Therapy and Tumor-Associated Macrophage Immunomodulation. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2024, 21, 663–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dozie-Nwachukwu, S.O.; Danyuo, Y.; Obayemi, J.D.; Odusanya, O.S.; Malatesta, K.; Soboyejo, W.O. Extraction and Encapsulation of Prodigiosin in Chitosan Microspheres for Targeted Drug Delivery. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 71, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwazojie, C.C.; Obayemi, J.D.; Salifu, A.A.; Borbor-Sawyer, S.M.; Uzonwanne, V.O.; Onyekanne, C.E.; Akpan, U.M.; Onwudiwe, K.C.; Oparah, J.C.; Odusanya, O.S.; et al. Targeted Drug-Loaded PLGA-PCL Microspheres for Specific and Localized Treatment of Triple Negative Breast Cancer. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2023, 34, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde-Vancells, J.; Rodriguez-Suarez, E.; Embade, N.; Gil, D.; Matthiesen, R.; Valle, M.; Elortza, F.; Lu, S.C.; Mato, J.M.; Falcon-Perez, J.M. Characterization and Comprehensive Proteome Profiling of Exosomes Secreted by Hepatocytes. J. Proteome Res. 2008, 7, 5157–5166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Masud, M.K.; Kaneti, Y.V.; Rewatkar, P.; Koradia, A.; Hossain, M.S.A.; Yamauchi, Y.; Popat, A.; Salomon, C. Extracellular Vesicle Nanoarchitectonics for Novel Drug Delivery Applications. Small 2021, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.A.; Baba, S.K.; Sadida, H.Q.; Marzooqi, S.A.; Jerobin, J.; Altemani, F.H.; Algehainy, N.; Alanazi, M.A.; Abou-Samra, A.-B.; Kumar, R.; et al. Extracellular Vesicles as Tools and Targets in Therapy for Diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodam, S.P.; Ullah, M. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Potential of Extracellular Vesicles. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2021, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt, B.K.; Walters, D.K.; Wu, X.; Tschumper, R.C.; Jelinek, D.F. Multiple Myeloma Cell-Derived Microvesicles Are Enriched in CD147 Expression and Enhance Tumor Cell Proliferation. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 5686–5699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menck, K.; Sivaloganathan, S.; Bleckmann, A.; Binder, C. Microvesicles in Cancer: Small Size, Large Potential. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, C.; Liang, Y.; Wang, K.; Li, P. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Cancer Therapy Resistance: From Biology to Clinical Opportunity. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2024, 20, 347–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Li, H.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Q.; Han, Z.; Han, Z.-C.; Zhu, L.; Wang, H.; Li, Z. Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Mesenchymal Stem Cells Suppress Breast Cancer Progression by Inhibiting Angiogenesis. Mol. Med. Rep. 2024, 30, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, T.; von der Ohe, J.; Hass, R. MSC-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Tumors and Therapy. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13, 5212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafaeizadeh, M.; Abroun, S.; Soufi Zomorrod, M. Effect of Human Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Microvesicles on the Apoptosis of the Multiple Myeloma Cell Line U266. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 150, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.-C.; Kang, I.; Yu, K.-R. Therapeutic Features and Updated Clinical Trials of Mesenchymal Stem Cell (MSC)-Derived Exosomes. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagi, H.; Soto-Gutierrez, A.; Parekkadan, B.; Kitagawa, Y.; Tompkins, R.G.; Kobayashi, N.; Yarmush, M.L. Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Mechanisms of Immunomodulation and Homing. Cell Transplant. 2010, 19, 667–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, J.; Sun, L.; Yang, Z.; Liu, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, X. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles: Current Advances in Preparation and Therapeutic Applications for Neurological Disorders. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roszkowski, S. Therapeutic Potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes for Regenerative Medicine Applications. Clin. Exp. Med. 2024, 24, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakirova, E.Y.; Valeeva, A.N.; Masgutov, R.F.; Naumenko, E.A.; Rizvanov, A.A. Application of Allogenic Adipose-Derived Multipotent Mesenchymal Stromal Cells from Cat for Tibial Bone Pseudoarthrosis Therapy (Case Report). Bionanoscience 2017, 7, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chulpanova, D.S.; Gilazieva, Z.E.; Kletukhina, S.K.; Aimaletdinov, A.M.; Garanina, E.E.; James, V.; Rizvanov, A.A.; Solovyeva, V. V. Cytochalasin B-Induced Membrane Vesicles from Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells Overexpressing IL2 Are Able to Stimulate CD8+ T-Killers to Kill Human Triple Negative Breast Cancer Cells. Biology (Basel) 2021, 10, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salarpour, S.; Forootanfar, H.; Pournamdari, M.; Ahmadi-Zeidabadi, M.; Esmaeeli, M.; Pardakhty, A. Paclitaxel Incorporated Exosomes Derived from Glioblastoma Cells: Comparative Study of Two Loading Techniques. DARU J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 27, 533–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmievskaya, E.A.; Mukhametshin, S.A.; Ganeeva, I.A.; Gilyazova, E.M.; Siraeva, E.T.; Kutyreva, M.P.; Khannanov, A.A.; Yuan, Y.; Bulatov, E.R. Artificial Extracellular Vesicles Generated from T Cells Using Different Induction Techniques. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutyreva, M.P.; Vagapova, A.I.; Maksimov, A.F.; Khannanov, A.A.; Ignatyeva, K.A.; Kiiamov, A.G.; Cherosov, M.A.; Emelianov, D.A.; Kutyrev, G.A. Hybrid Nanostructures of Hyperbranched Polyester Loaded with Gd(III) and Dy(III) Ions. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2024, 6, 1662–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malloy, A.; Hole, P.; Carr, B. NanoParticle Tracking Analysis; The Halo System. MRS Proc. 2006, 952, 0952-F02-04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malloy, A.; Carr, B. NanoParticle Tracking Analysis – The HaloTM System. Part. Part. Syst. Charact. 2006, 23, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midekessa, G.; Godakumara, K.; Ord, J.; Viil, J.; Lättekivi, F.; Dissanayake, K.; Kopanchuk, S.; Rinken, A.; Andronowska, A.; Bhattacharjee, S.; et al. Zeta Potential of Extracellular Vesicles: Toward Understanding the Attributes That Determine Colloidal Stability. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 16701–16710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmacharya, M.; Kumar, S.; Cho, Y.-K. Tuning the Extracellular Vesicles Membrane through Fusion for Biomedical Applications. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubuke, M.L.; Munson, M. The Secret Life of Tethers: The Role of Tethering Factors in SNARE Complex Regulation. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2016, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumontet, C.; Reichert, J.M.; Senter, P.D.; Lambert, J.M.; Beck, A. Antibody–Drug Conjugates Come of Age in Oncology. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2023, 22, 641–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, H.; Guo, S.; Ren, X.; Wu, Z.; Liu, S.; Yao, X. Current Strategies for Exosome Cargo Loading and Targeting Delivery. Cells 2023, 12, 1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S.; Haney, M.J.; Zhao, Y.; Mahajan, V.; Deygen, I.; Klyachko, N.L.; Inskoe, E.; Piroyan, A.; Sokolsky, M.; Okolie, O.; et al. Development of Exosome-Encapsulated Paclitaxel to Overcome MDR in Cancer Cells. Nanomedicine Nanotechnology, Biol. Med. 2016, 12, 655–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haney, M.J.; Klyachko, N.L.; Zhao, Y.; Gupta, R.; Plotnikova, E.G.; He, Z.; Patel, T.; Piroyan, A.; Sokolsky, M.; Kabanov, A. V.; et al. Exosomes as Drug Delivery Vehicles for Parkinson’s Disease Therapy. J. Control. Release 2015, 207, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartjes, T.A.; Mytnyk, S.; Jenster, G.W.; van Steijn, V.; van Royen, M.E. Extracellular Vesicle Quantification and Characterization: Common Methods and Emerging Approaches. Bioeng. (Basel, Switzerland) 2019, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabeo, D.; Cvjetkovic, A.; Lässer, C.; Schorb, M.; Lötvall, J.; Höög, J.L. Exosomes Purified from a Single Cell Type Have Diverse Morphology. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisse, P.; Rago, I.; Ulloa Severino, L.; Perissinotto, F.; Ambrosetti, E.; Paoletti, P.; Ricci, M.; Beltrami, A.P.; Cesselli, D.; Casalis, L. Atomic Force Microscopy Analysis of Extracellular Vesicles. Eur. Biophys. J. 2017, 46, 813–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Vlist, E.J.; Nolte-’t Hoen, E.N.M.; Stoorvogel, W.; Arkesteijn, G.J.A.; Wauben, M.H.M. Fluorescent Labeling of Nano-Sized Vesicles Released by Cells and Subsequent Quantitative and Qualitative Analysis by High-Resolution Flow Cytometry. Nat. Protoc. 2012, 7, 1311–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soo, C.Y.; Song, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Campbell, E.C.; Riches, A.C.; Gunn-Moore, F.; Powis, S.J. Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis Monitors Microvesicle and Exosome Secretion from Immune Cells. Immunology 2012, 136, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokolova, V.; Ludwig, A.-K.; Hornung, S.; Rotan, O.; Horn, P.A.; Epple, M.; Giebel, B. Characterisation of Exosomes Derived from Human Cells by Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis and Scanning Electron Microscopy. Colloids Surf. B. Biointerfaces 2011, 87, 146–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardiner, C.; Di Vizio, D.; Sahoo, S.; Théry, C.; Witwer, K.W.; Wauben, M.; Hill, A.F. Techniques Used for the Isolation and Characterization of Extracellular Vesicles: Results of a Worldwide Survey. J. Extracell. vesicles 2016, 5, 32945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Théry, C.; Witwer, K.W.; Aikawa, E.; Alcaraz, M.J.; Anderson, J.D.; Andriantsitohaina, R.; Antoniou, A.; Arab, T.; Archer, F.; Atkin-Smith, G.K.; et al. Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): A Position Statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and Update of the MISEV2014 Guidelines. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2018, 7, 1535750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz-Armas, G.G.; Cervantes-Gonzalez, A.P.; Martinez-Duarte, R.; Perez-Gonzalez, V.H. Electrically Driven Microfluidic Platforms for Exosome Manipulation and Characterization. Electrophoresis 2022, 43, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassanpour Tamrin, S.; Sanati Nezhad, A.; Sen, A. Label-Free Isolation of Exosomes Using Microfluidic Technologies. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 17047–17079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kira, A.; Tatsutomi, I.; Saito, K.; Murata, M.; Hattori, I.; Kajita, H.; Muraki, N.; Oda, Y.; Satoh, S.; Tsukamoto, Y.; et al. Apoptotic Extracellular Vesicle Formation via Local Phosphatidylserine Exposure Drives Efficient Cell Extrusion. Dev. Cell 2023, 58, 1282–1298.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samwang, T.; Watanabe, N.M.; Okamoto, Y.; Umakoshi, H. Exploring the Influence of Morphology on Bipolaron–Polaron Ratios and Conductivity in Polypyrrole in the Presence of Surfactants. Molecules 2024, 29, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clogston, J.D.; Patri, A.K. Zeta Potential Measurement; 2011; pp. 63–70. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).