1. Introduction

Financial crimes represent a growing global threat to economic stability, security, and trust in financial systems. (Klare et al., 2025; Misra et al., 2025) Simultaneously, advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) offer powerful tools for detecting sophisticated fraudulent activities. However, ensuring digital sovereignty—including data privacy, ethical governance, and national control—remains an underexplored area in AI-driven surveillance. (Pandey, 2025; Katsikas, 2025)

While various AI-based fraud detection systems have emerged, many prioritize efficiency over privacy and sovereignty. Traditional models often rely on foreign cloud infrastructures, exposing sensitive national data to external risks. Prior studies highlight the need for sovereign AI solutions capable of balancing detection effectiveness with ethical, legal, and technological independence requirements. (Iqbal & Ismail, 2025; Tith & Colin, 2025).

Against this backdrop, the Intelligent Surveillance Engine (ISE) emerges as a transformative architecture that not only addresses the technical demands of advanced fraud detection but also aligns seamlessly with sovereign data governance principles. By leveraging artificial intelligence in a secure, privacy-preserving, and regulation-compliant manner, ISE redefines the boundaries of financial surveillance technology. Its modular architecture ensures that it can evolve alongside regulatory changes and emerging fraud vectors, positioning it as an indispensable tool for both financial institutions and regulatory authorities.

This work proposes the Intelligent Surveillance Engine (ISE), an AI-driven, privacy-preserving framework designed not only to detect financial crimes but to support legal compliance, national autonomy, and ethical AI oversight across jurisdictional boundaries. ISE integrates systematic anomaly detection, sovereign cloud deployment, bias mitigation strategies, and ethical AI governance protocols. (Chatterjee et al., 2025; Anunita et al., 2025)

This study aims to propose a novel AI-powered architecture, the Intelligent Surveillance Engine (ISE), developed to detect financial crimes while ensuring compliance with digital sovereignty through privacy, ethical AI governance, and national data protection regulations.

1.1. Sovereign-Compliant AI for Financial Surveillance

The Intelligent Surveillance Engine is founded on the principle of sovereignty-first development. It is engineered to operate within nationally regulated infrastructures, such as government-operated data centers or sovereign cloud platforms like GAIA-X in Europe or MeghRaj in India [5-6]. This development choice ensures that all data remains under the control of national entities, in compliance with legal architectures such as the general data protection regulation (Jaiswal & Schaathun, 2025).

ISE goes beyond technical efficacy by embedding legal and ethical compliance into its core. This strategic alignment with sovereign digital policies enables the system to meet both domestic regulatory requirements and international standards for trust, transparency, and accountability in artificial intelligence systems. In essence, ISE shifts the paradigm from static, legally ambiguous models to context-sensitive architectures that uphold national interests while delivering real-time financial threat intelligence.

1.2. Key Contributions of the Chapter

This chapter presents an AI-driven framework for financial crime detection that is fully aligned with the principles of digital sovereignty. The key contributions of the manuscript—technically and from a digital sovereignty standpoint—are as follows:

Development of the Intelligent Surveillance Engine (ISE), a digital sovereignty-compliant AI architecture for detecting financial crimes.

Integration of privacy-preserving AI techniques and sovereign data governance mechanisms that reinforce transparency, ethical oversight, and local data control.

Behavior-Aware Profiling Using Collaborative Filtering to build dynamic transaction baselines using contextual features such as transaction amount, frequency, and origin.

Multi-Layered Anomaly Detection combining unsupervised techniques (Isolation Forest, DBSCAN, PCA, SVM) to identify nuanced anomalies and evolving fraud patterns.

Supervised Fraud Classification utilizing Random Forest and SVM to label anomalies into fraud types such as identity theft, account takeover, and synthetic fraud.

Ensemble Learning for Decision Assurance using ensemble methods (stacking, boosting, majority voting) to reduce false positives and negatives, increasing trust and reliability.

Superior performance in benchmarking demonstrating significant improvements in FNR, recall, and F1-score compared to traditional fraud detection systems.

Scalability and Real-Time Detection validated through sub-second latency and performance across diverse datasets, making the system viable for national deployment.

Contribution to Digital Sovereignty and AI Governance by promoting sovereign-compliant, privacy-preserving, and auditable AI frameworks that reduce reliance on foreign tech and align with national cybersecurity objectives.

The remainder of this chapter is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews related work and highlights existing gaps.

Section 3 presents the proposed architecture and methodological framework.

Section 4 discusses the experimental results and findings.

Section 5 elaborates on contributions to digital sovereignty and AI governance.

Section 6 presents the limitations of our proposed ISE and

Section 7 concludes the study and suggests future research directions.

2. Review of Relevant Works

The evolution of digital sovereignty and artificial intelligence (AI) has spurred an increasing interest in developing sovereign-compliant frameworks for critical domains such as cybersecurity, privacy, and fraud detection. This section reviews foundational and contemporary studies shaping the context of the Intelligent Surveillance Engine (ISE) proposed in this work.

2.1. Digital Sovereignty Foundations

Digital sovereignty emphasizes the ability of nations and organizations to control their digital infrastructure, data, and technologies. Klare et al. (2025) explored digital sovereignty recommendations across the software development lifecycle, identifying the need for sovereignty-by-design practices (Klare et al., 2025). Similarly, Misra et al. (2025) discussed sovereignty challenges arising from Industry 5.0, highlighting the strategic necessity for sovereign technology development in complex industrial environments (Misra et al., 2025).

2.2. Cybersecurity and Sovereignty Linkage

The connection between cybersecurity and digital sovereignty has been emphasized by Katsikas (2025), who proposed a cybersecurity-oriented research agenda to ensure national digital independence (Katsikas, 2025). Chatterjee et al. (2025) advanced this perspective by presenting a sovereignty-aware intrusion detection system using automated machine learning (AutoML) pipelines and semantic reasoning over streaming data, demonstrating how real-time security systems can be aligned with sovereign compliance (Chatterjee et al., 2025).

2.3. Sovereign AI Systems and Bias Detection

Iqbal and Ismail (2025) tackled bias issues in AI systems by proposing a statistical bias detection framework that respects sovereignty principles (Iqbal & Ismail, 2025). Likewise, Anunita et al. (2025) explored federated learning frameworks to counter label-flipping attacks in sensitive domains such as medical imaging, demonstrating the potential of decentralized AI training for sovereignty preservation (Anunita et al., 2025). Tith and Colin (2025) further contributed to sovereign identity management by developing a trust policy meta-model for interoperable and trustworthy digital identity systems (Tith & Colin, 2025).

2.4. Financial Crime Detection and AI

Although direct studies on financial crime under sovereignty constraints remain limited, related works such as the sovereign IDS proposed by Chatterjee et al. (2025) provide critical methodological insights for surveillance systems. Pandey (2025) further stressed the importance of developing national AI infrastructures through India’s AI Stack initiative, underscoring the strategic need for indigenous AI ecosystems to maintain financial and technological independence (Pandey, 2025).

Overall, the reviewed works underscore the increasing necessity of sovereignty-focused AI frameworks, particularly in cybersecurity and identity management domains. However, a clear gap persists in operational sovereign-compliant financial crime detection systems. The proposed Intelligent Surveillance Engine (ISE) uniquely addresses this void by combining systematic anomaly detection, privacy-preserving AI, sovereign data control, and real-time fraud surveillance, thus extending the frontier of sovereign digital infrastructures.

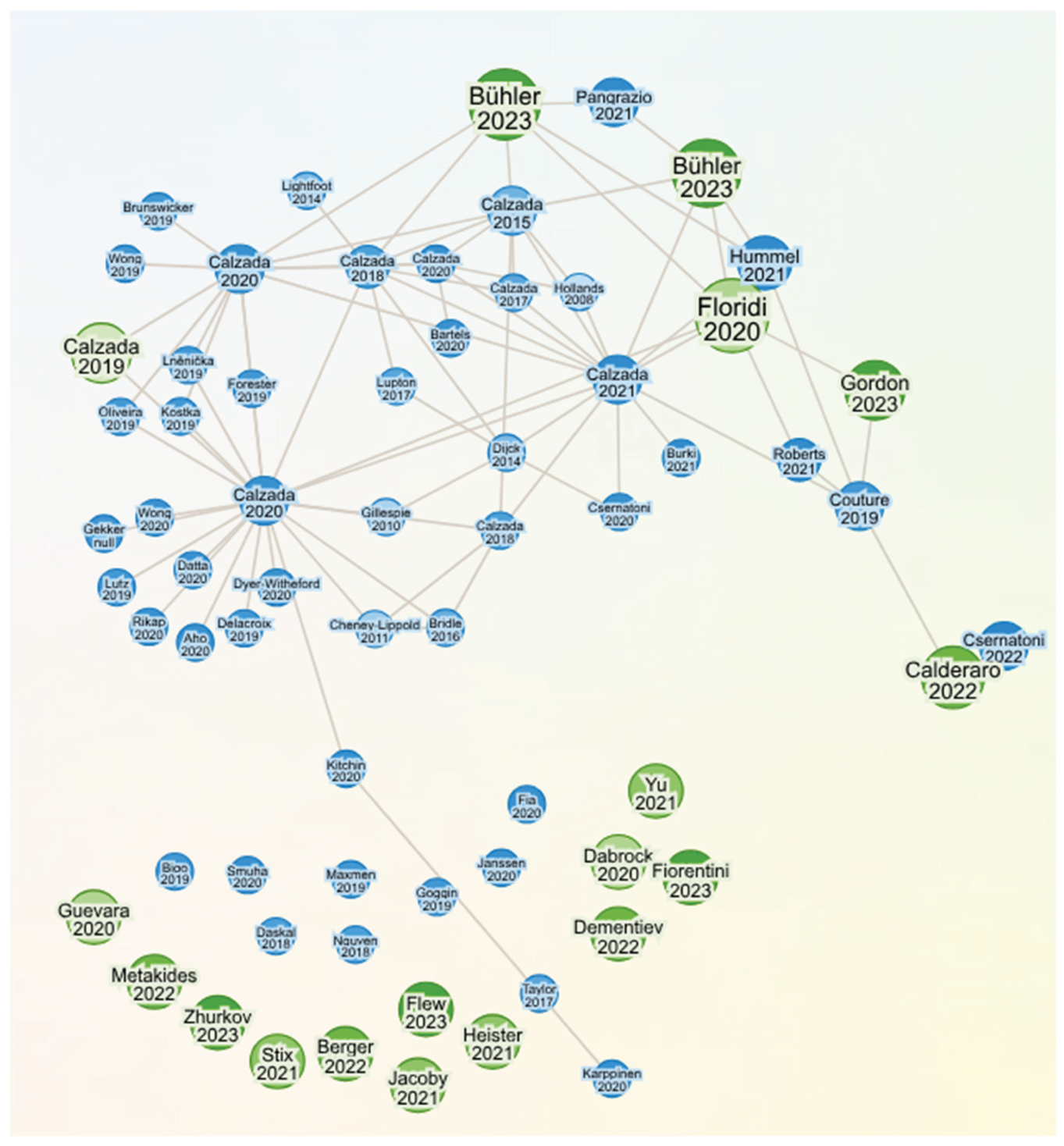

2.5. Connected Graph of Digital Sovereign and AI Systems

The rapid evolution of artificial intelligence (AI) and digital technologies has prompted significant scholarly attention to governance frameworks, sovereignty concerns, and collaborative data-sharing models. This review examines three recent papers addressing these themes: Zhurkov’s (2023) analysis of AI regulation under sanctions, Calderaro and Blumfelde’s (2022) critique of EU digital sovereignty and Bühler et al.’s (2023) proposal for data cooperatives. Collectively, these works highlight the intersection of technological innovation, regulatory challenges, and socio-economic equity in the digital age as shown the

Figure 1.

Zhurkov (2023) explores the legal challenges of regulating AI in Russia amid escalating foreign sanctions and the pursuit of national digital sovereignty. The author argues that AI technologies are pivotal for mitigating economic risks faced by domestic businesses, particularly after the 2022 geopolitical shifts. Zhurkov emphasizes the need for robust legal frameworks to ensure data autonomy, reduce reliance on foreign IT solutions, and align AI development with national security priorities. The study critiques existing regulatory gaps and proposes criteria for digital sovereignty, including domestic control over data storage and technology imports. However, the analysis is limited by its regional focus and does not address global implications of fragmented AI governance.

Calderaro and Blumfelde (2022) assess the European Union’s (EU) ambition to achieve digital sovereignty through regulatory measures. The authors contend that despite initiatives like the GDPR and Data Governance Act, the EU lacks the technological infrastructure and defense integration to compete with the U.S. and China in AI leadership. They frame sovereignty through three AI pillars—data, algorithms, and hardware—and conclude that the EU’s reliance on normative power and ethical standards, rather than industrial capacity, undermines its strategic autonomy. While insightful, the study overlooks the potential of intra-EU collaboration and emerging policies like the AI Act to address these gaps.

Bühler et al. (2023) advocate for data cooperatives as a mechanism to democratize data access and counterbalance corporate monopolies. Their preprint outlines how cooperatives enable SMEs and communities to pool resources, enhance decision-making, and foster innovation while preserving data sovereignty. Case studies from Kenya (M-Pesa), India (eKutir), and Germany (GemeinWerk) demonstrate economic, social, and environmental benefits. The authors propose policy recommendations, including harmonized regulations and funding mechanisms, to scale such models. While compelling, the paper’s reliance on preprint status and nascent case studies limits empirical validation of long-term efficacy.

These studies collectively underscore the tension between centralized regulation and decentralized collaboration in AI governance. Zhurkov (2023) and Calderaro and Blumfelde (2022) highlight state-centric approaches, whereas Bühler et al. (2023) prioritize community-driven solutions. A critical gap lies in reconciling national sovereignty with global interoperability, particularly as data cooperatives and EU regulations may conflict with cross-border data flows. Future research should explore hybrid models that integrate state oversight with grassroots innovation to address digital inequities.

The evolving discourse on digital sovereignty and technological governance is critically examined across three papers, each contributing unique perspectives on how nations, supranational entities, and municipalities navigate the complexities of digital transformation. This review synthesizes the arguments presented by Gordon (2023), Floridi (2020), and Calzada (2018), highlighting their contributions to understanding digital sovereignty in the contexts of quantum technologies, supranational policy frameworks, and city-regional governance.

Gordon (2023) explores the intersection of quantum technologies, digital sovereignty, and international law, emphasizing the liminal position of quantum computing, sensing, and communication within European policy frameworks. The paper argues that while quantum technologies remain nascent, their integration into digital infrastructures could disrupt existing encryption protocols and reshape global power dynamics. Gordon highlights the European Quantum Flagship initiative as a strategic investment aimed at securing Europe’s technological autonomy. However, he cautions that current trajectories may reinforce existing inequalities, as the development of quantum technologies is dominated by a few corporate and state actors (Gordon, 2023). The paper’s strength lies in its diffractive methodology, which juxtaposes material technologies with legal frameworks to reveal ambivalent futures for international law—simultaneously transformative and regressive.

Floridi (2020) positions digital sovereignty as a critical battleground between states and corporations, using case studies such as the EU-US Data Protection Shield invalidation and Huawei’s 5G controversies. He argues that digital sovereignty transcends technical control, encompassing data, algorithms, and infrastructure. Floridi critiques the rise of “corporate digital sovereignty” dominated by tech giants like Google and Amazon, advocating instead for a supranational EU model to balance innovation with democratic accountability (Floridi, 2020). His analysis of network topologies—fully connected, star, and hybrid—provides a nuanced framework for legitimizing supranational governance. Floridi’s call for a “United States of Europe” underscores the need for flexible, multi-level sovereignty to address the democratic deficit in digital policymaking.

Calzada (2018) shifts the focus to municipal governance, analyzing Barcelona’s grassroots initiatives to reclaim digital rights through technological sovereignty. By leveraging GDPR, Barcelona implemented participatory platforms like DECODE and DECIDIM, prioritizing citizen agency over corporate data extraction. Calzada contrasts Europe’s “technological humanism” with the U.S.’s corporate-driven and China’s state-centric models, arguing that cities can federate into ecosystems to protect digital rights (Calzada, 2018). The case study highlights the tension between innovation and privacy, particularly in regulating platform capitalism (e.g., Uber, Airbnb). However, Calzada acknowledges uncertainties in sustaining these initiatives amid political shifts, such as Catalonia’s independence movement.

These papers collectively underscore the multi-scalar nature of digital sovereignty. Gordon’s focus on quantum technologies reveals the anticipatory governance challenges posed by emerging innovations, while Floridi and Calzada address immediate policy and municipal strategies. A common thread is the role of GDPR as a regulatory cornerstone, though its implementation varies across supranational and local contexts (Floridi, 2020; Calzada, 2018). Gordon and Floridi both highlight the risks of corporate consolidation, with Floridi advocating supranational oversight and Calzada emphasizing municipal empowerment. Notably, Calzada’s bottom-up approach contrasts with Gordon’s top-down analysis of EU policy, illustrating the spectrum of sovereignty strategies. However, gaps remain. Gordon’s speculative analysis of quantum technologies lacks empirical data on current governance impacts, while Calzada’s optimistic view of Barcelona’s model overlooks scalability challenges. Floridi’s hybrid network model, though theoretically robust, requires further exploration of its feasibility in fragmented political landscapes.

The reviewed papers offer diverse perspectives on navigating AI’s ethical, legal, and economic challenges. While Zhurkov and Calderaro and Blumfelde emphasize regulatory and geopolitical dimensions, Bühler et al. provide a pragmatic pathway for equitable data governance. Policymakers must balance these insights to foster inclusive digital ecosystems resilient to both market concentration and geopolitical fragmentation. These papers enrich the discourse on digital sovereignty by addressing technological, policy, and municipal dimensions. Gordon (2023) foresees quantum technologies as both a disruptor and reinforcer of power imbalances, Floridi (2020) provides a blueprint for supranational legitimacy, and Calzada (2018) demonstrates the potential of citizen-centric governance. Together, they advocate for a balanced approach that harmonizes innovation with ethical accountability, ensuring digital sovereignty serves as a tool for democratic empowerment rather than exclusion.

2.6. Related Work Comparison Table

Table 1 summarizes key existing works related to digital sovereignty, cybersecurity, and AI-driven systems. While these studies have laid critical theoretical and conceptual foundations, most fall short of offering operational AI frameworks that ensure digital sovereignty while effectively detecting financial crimes. The Intelligent Surveillance Engine (ISE) addresses these identified gaps.

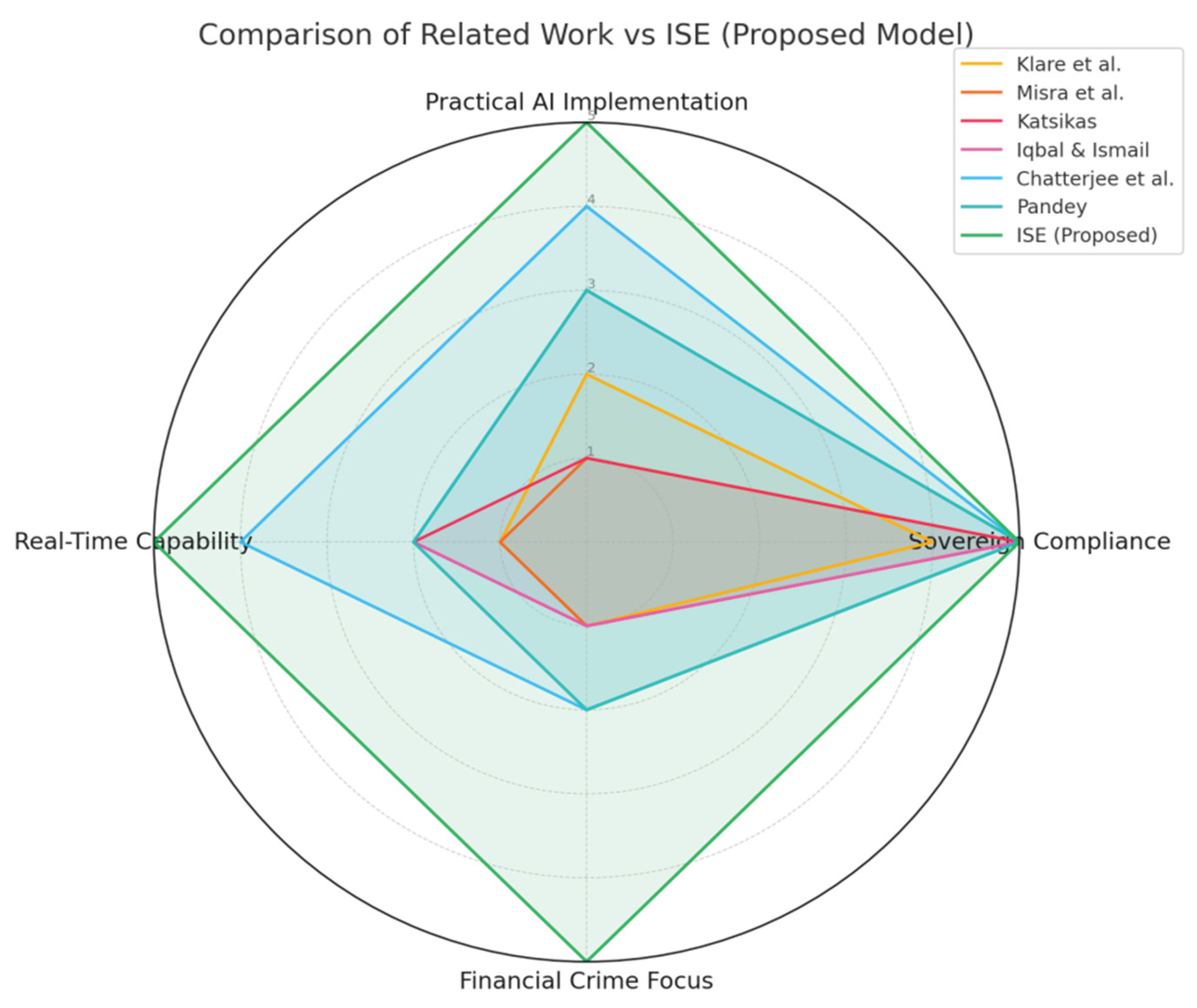

The ISE framework demonstrates superior performance by comprehensively addressing gaps identified in prior work. The radar chart in

Figure 2 above compares existing works with the proposed Intelligent Surveillance Engine (ISE) clearly highlights significant gaps in the current literature regarding practical AI implementation, sovereign compliance, financial crime focus, and real-time capability. While prior studies such as Klare et al. (2025) and Misra et al. (2025) address strategic and conceptual aspects of digital sovereignty, they lack technical operationalization and direct application to financial crime detection. Similarly, works like Katsikas (2025) and Iqbal & Ismail (2025) emphasize cybersecurity and bias detection, respectively, but fall short in real-time operational deployment. Although Chatterjee et al. (2025) approaches real-time detection through IDS systems, it remains limited to intrusion detection rather than financial fraud. The proposed ISE framework distinctly outperforms previous models by achieving full marks across all criteria—practical AI deployment, sovereign compliance, financial crime targeting, and real-time surveillance—demonstrating a comprehensive and robust solution directly addressing the critical gaps in the field.

3. System Architecture of the Intelligent Surveillance Engine (ISE)

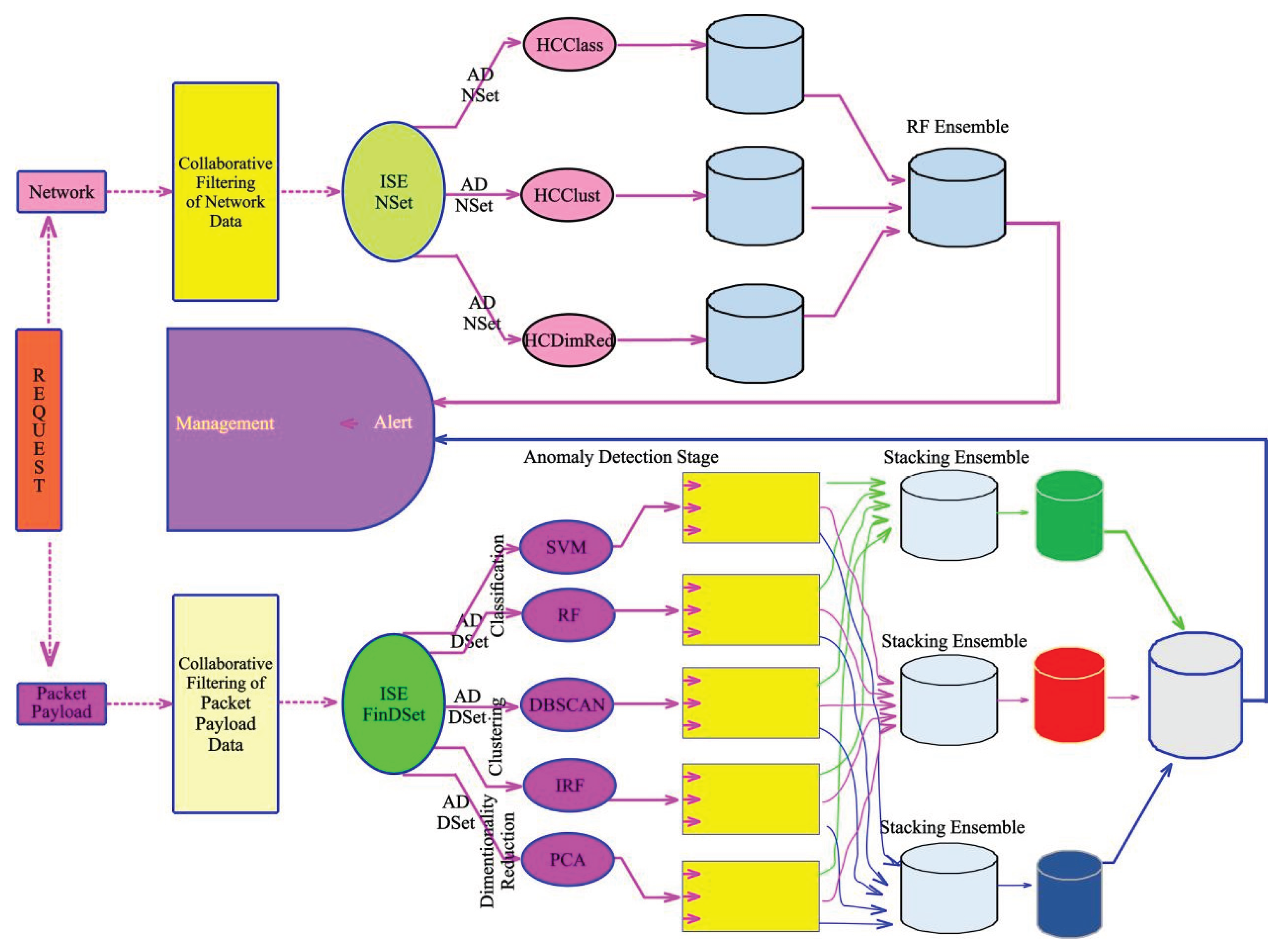

The Intelligent Surveillance Engine (ISE) is designed as a modular, four-stage architecture that systematically integrates collaborative filtering, anomaly detection, and ensemble learning. It embodies a sovereignty-compliant AI framework that balances technological intelligence with ethical data governance, privacy preservation, and transparency—key pillars of digital sovereignty.

Stage 1: Systematic Detection via Collaborative Filtering

The foundation of ISE lies in its behavior-aware profiling system, which uses collaborative filtering (CF) techniques to construct dynamic behavioral baselines for financial entities. This layer exploits user–transaction interactions to detect suspicious co-behavior among accounts, such as identical transaction patterns across distinct accounts, timing regularities, and transfer flows indicative of layering or tumbling. For instance, when a single Layering Subject (LS) consistently distributes identical amounts to a large group of accounts (Layering Objects, LOs) on a periodic basis, CF algorithms such as Alternating Least Squares (ALS), KNN (with cosine similarity), and matrix factorization (SVD) can reveal these synthetic patterns. This stage produces the Systematically Filtered Dataset (SFinDSet), a dataset filtered for probable layering activities based on latent co-behavioral signatures.

Stage 2: Anomaly Detection (AD)

The filtered dataset from Stage 1 is passed to a robust anomaly detection (AD) engine in Stage 2. Here, five distinct unsupervised or semi-supervised machine learning algorithms are deployed independently to identify statistical outliers:

Each algorithm detects anomalies from a unique statistical perspective—e.g., IF isolates sparse points, DBSCAN finds density-based clusters, while PCA and SVM detect directionally inconsistent behaviors. The outcome is a multi-view anomaly profile, where each data point is assigned multiple anomaly flags and scores. This modular detection ensures broad anomaly coverage while adhering to principles of fairness and transparency.

Stage 3: Ensemble Validation and Decision Assurance

To achieve high-confidence anomaly confirmation, the outputs from the five ML algorithms in Stage 2 are fed into an ensemble validation framework in Stage 3. A stacking ensemble model is used to consolidate the multiple anomaly flags, classifying only those anomalies that are consistently detected across several algorithms as confirmed fraud. This consensus approach significantly reduces false positives and enhances model interpretability and auditability—key compliance requirements in digital sovereignty. The result is the Confirmed Anomaly Set (CAS), a validated output of fraud signals that can be transparently reviewed by financial institutions and regulators.

These scores provide a granular understanding of the nature, severity, and frequency of observed anomalies as shown in

Figure 3.

ISE’s architecture in

Figure 3 supports data localization, algorithmic accountability, and model explainability—critical for jurisdictions enforcing digital sovereignty. Each component is designed to function within national boundaries, ensuring that sensitive financial data is processed locally, never offshored or dependent on foreign infrastructure. Furthermore, all ML stages support human audit trails, enabling regulators to inspect decisions, thresholds, and training datasets—thereby aligning AI-driven fraud detection with principles of ethical, sovereign, and trusted AI.

Stage 4. Deployment within Sovereign Cloud Infrastructures

ISE is specifically developed for deployment in sovereign cloud environments and critical infrastructure networks that are subject to national data protection laws. Whether hosted within a central bank’s data center, a regulatory agency’s cloud infrastructure, or a licensed financial institution’s internal systems, ISE ensures that sensitive data never leaves sovereign boundaries. This local-first deployment model enables institutions to maintain full control over their data while leveraging cutting-edge AI capabilities.

Furthermore, ISE is compatible with emerging national AI governance architectures that prioritize transparency, explainability, and human oversight. It supports localized model training, policy-driven updates, and role-based access control mechanisms that align with public-sector requirements for operational integrity and legal compliance.

4. Results Presentation and Analysis

This section presents and analyzes the performance of the proposed Intelligent Surveillance Engine (ISE) across its three core layers: Systematic Detection (Collaborative Filtering), Anomaly Detection (ML Algorithms), and Ensemble Integration. The evaluation includes detection effectiveness, latency, anomaly overlap, and digital sovereignty compliance.

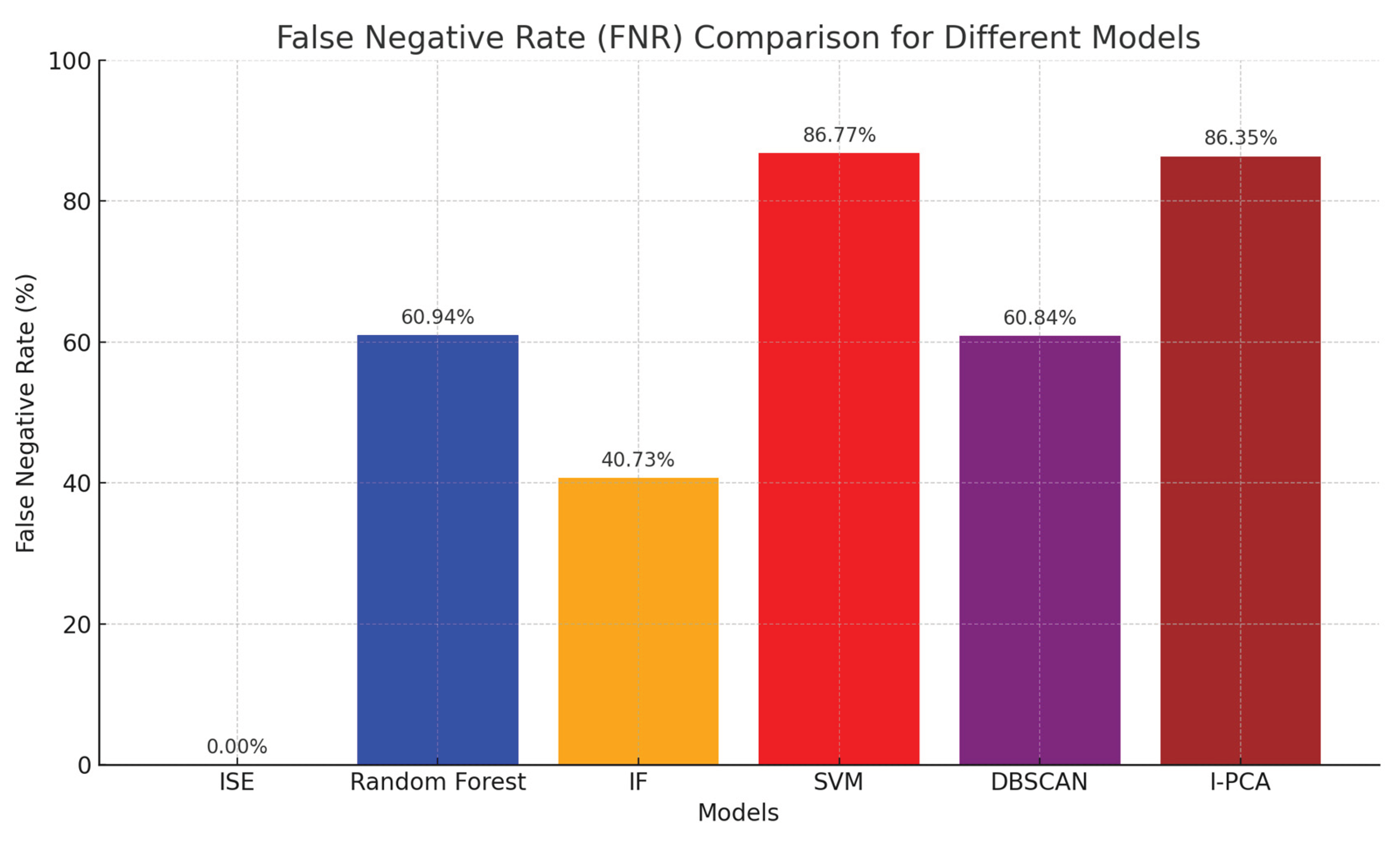

4.1. Systematic Detection and False Negative Reduction

In alignment with sovereignty principles of fairness and completeness, the system’s first layer uses collaborative filtering to identify hidden layering patterns. This layer produced the Dataset (ISEDSet) from one of the stages of ISE, which was evaluated using False Negative Rate (FNR) as shown in

Figure 4.

Table 2.

Performance Comparison: ISE vs. Machine Learning Models Using Confusion Matrices.

Table 2.

Performance Comparison: ISE vs. Machine Learning Models Using Confusion Matrices.

| Model |

True Positives (TP) |

False Negatives (FN) |

False Negative Rate (FNR %) |

| ISE |

7694 |

0 |

0.00 |

| Random Forest |

3005 |

4689 |

60.94 |

| IF |

4560 |

3134 |

40.73 |

| SVM |

1018 |

6676 |

86.77 |

| DBSCAN |

3013 |

4681 |

60.84 |

| I-PCA |

1050 |

6644 |

86.35 |

ISE through collaborative filtering achieved a perfect FNR of 0.00%, meaning it successfully identified all actual false negatives without missing any, making it the most effective model, outperforming all individual ML models (e.g., IF with 40.73%, Random Forest at 60.94%, DBSCAN at 60.84%, SVM at 86.77%). Reducing false negatives at this stage improves sovereign oversight and mitigates hidden financial threats that would otherwise escape detection.

4.2. Multi-Model Anomaly Detection (AD Stage)

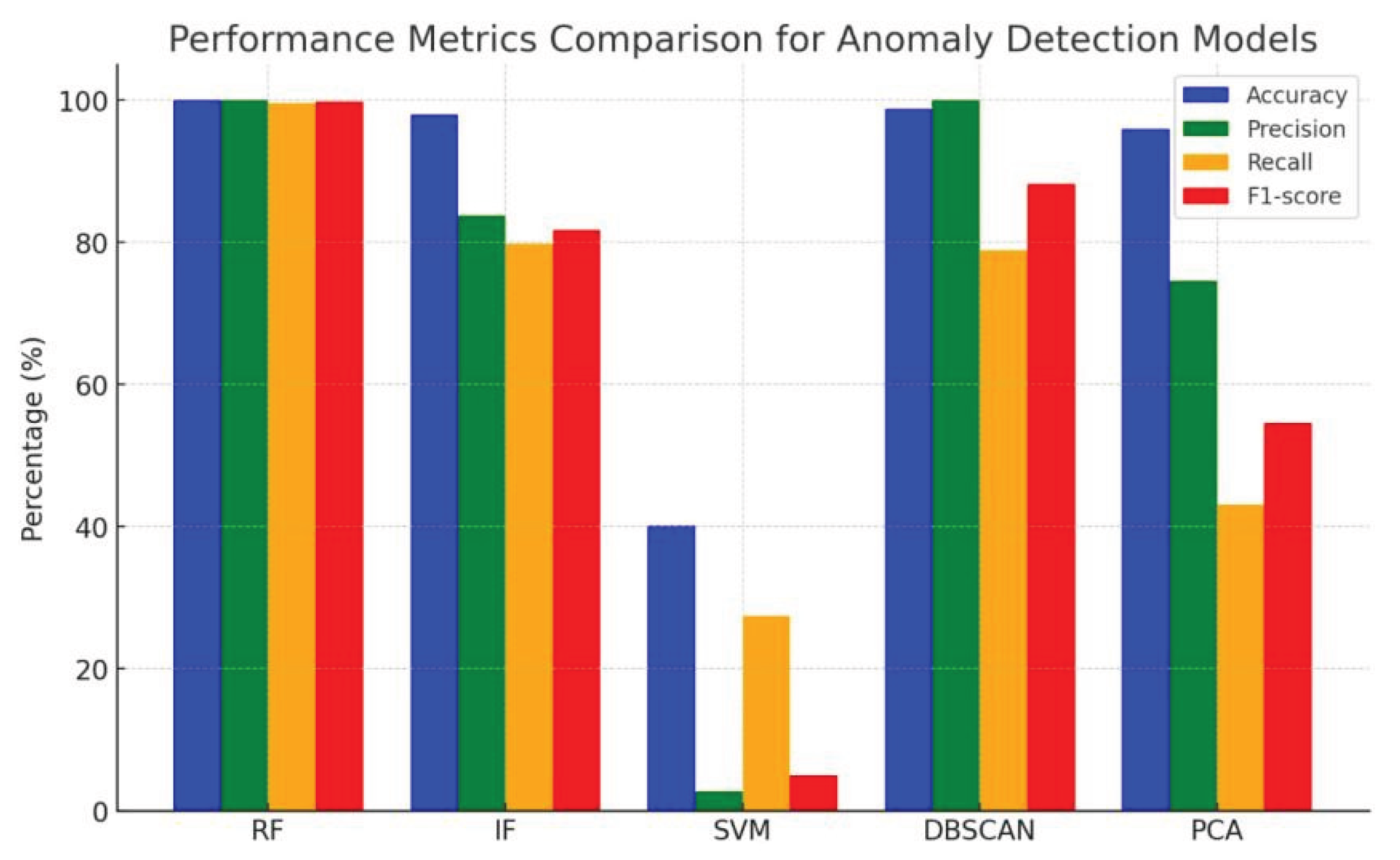

Two supervised, two unsupervised and one dimentionality reduction ML algorithms were tested on the output of Stage 1 (ISEDSet) to detect anomalies from different perspectives. Random Forest and DBSCAN emerged as the top performers as shown in

Table 3.

Random Forest achieved an accuracy of 99.97%, recall of 99.55%, and F1-score of 99.77%. DBSCAN followed closely with a strong F1-score of 88.21% as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Performance Metrics Comparison for Anomaly Detection Models.

Figure 5.

Performance Metrics Comparison for Anomaly Detection Models.

These results support localized AI-based decision-making aligned with digital sovereignty.

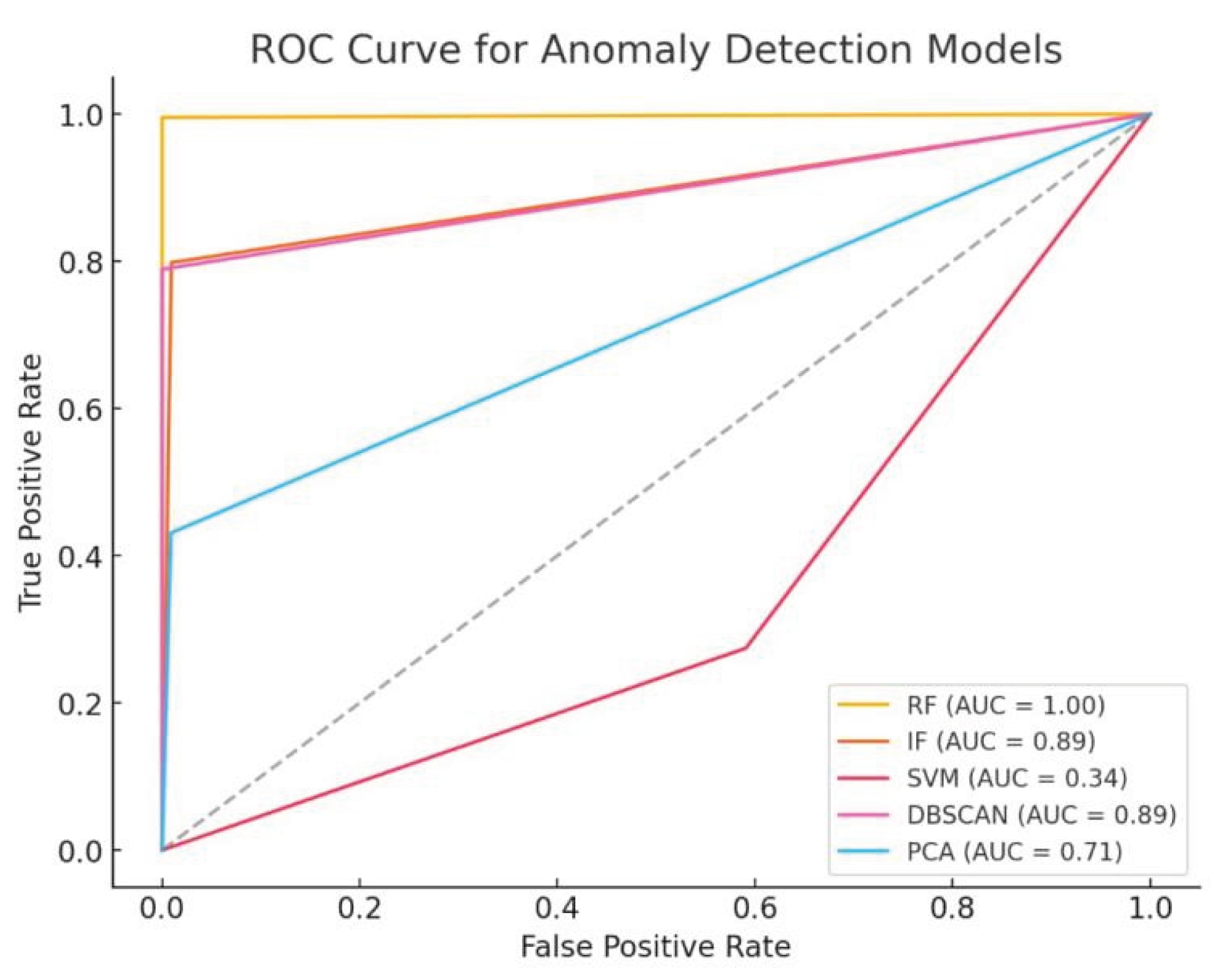

However, the ROC curve in

Figure 6 illustrates the comparative performance of five anomaly detection models used in this study, through precision, transparency, and low false positive rates. Random Forest (RF) demonstrates perfect classification capability with an AUC of 1.00, affirming its suitability for high-stakes sovereign applications requiring minimal error and full auditability. Both Isolation Forest (IF) and DBSCAN exhibit strong AUC values of 0.89, reinforcing their reliability in identifying diverse and complex anomalies, which supports resilient and adaptive AI governance frameworks. PCA shows moderate performance (AUC = 0.71), while SVM lags significantly (AUC = 0.34), indicating high false positive rates and unsuitability for real-time sovereign systems.

Figure 5.

ROC Curve for Anomaly Detection Models.

Figure 5.

ROC Curve for Anomaly Detection Models.

These results validate the ensemble approach adopted in this work, particularly the integration of RF and DBSCAN, to maximize precision and trustworthiness—cornerstones of digital sovereignty in AI-driven fraud detection systems.

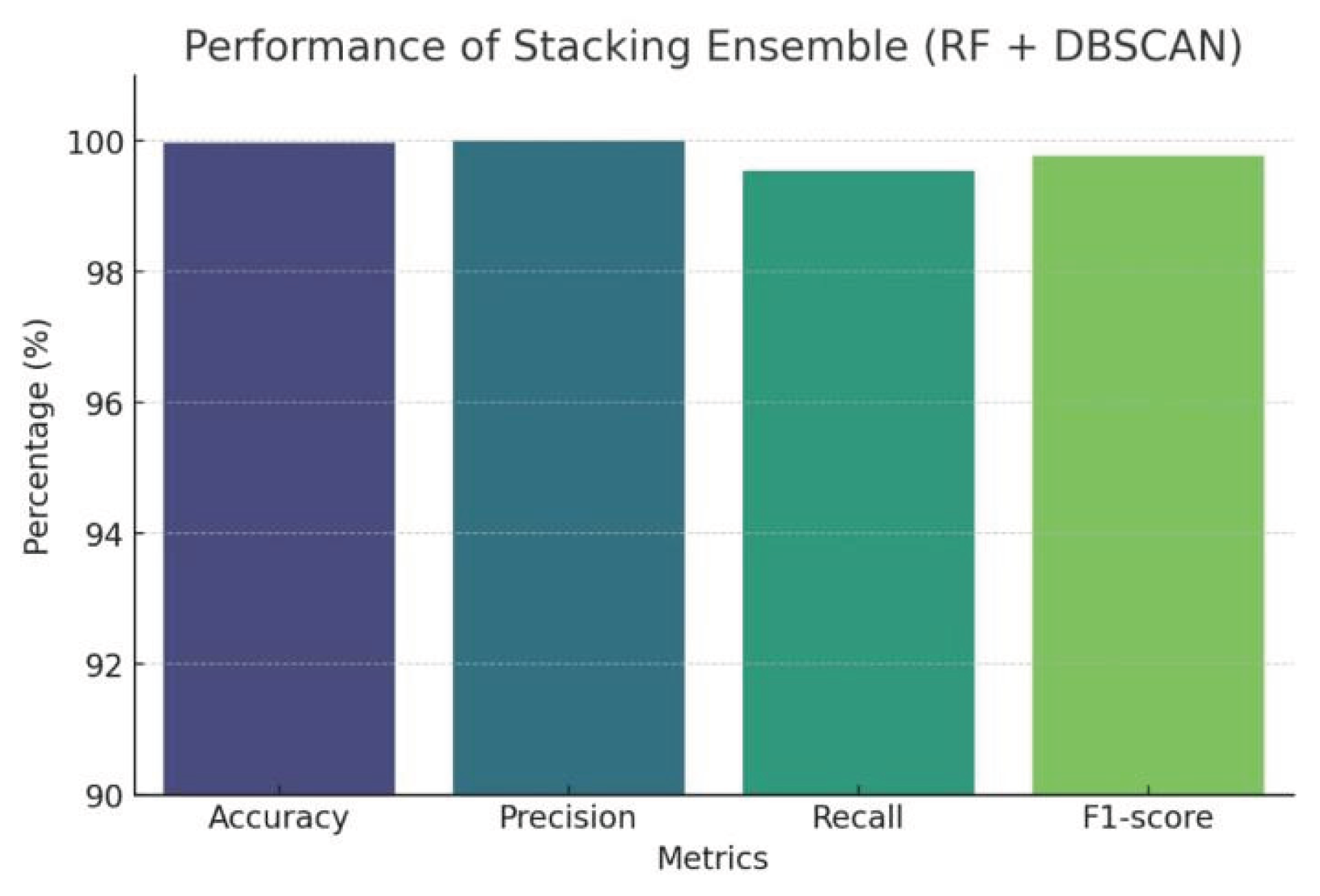

4.3.3. Ensemble Layer and Confirmed Anomalies

Table 4 displays the outputs from RF and DBSCAN that were combined using a stacking ensemble.

Figure 6 represents the results of the stacking ensemble which produced an accuracy of 100%, precision of 100%, recall of 99.55%, and F1-score of 99.77%.

Figure 6.

Performance Metric for the Stacking Ensemble.

Figure 6.

Performance Metric for the Stacking Ensemble.

This consensus-based decision-making enhances trust and auditability—key digital sovereignty requirements.

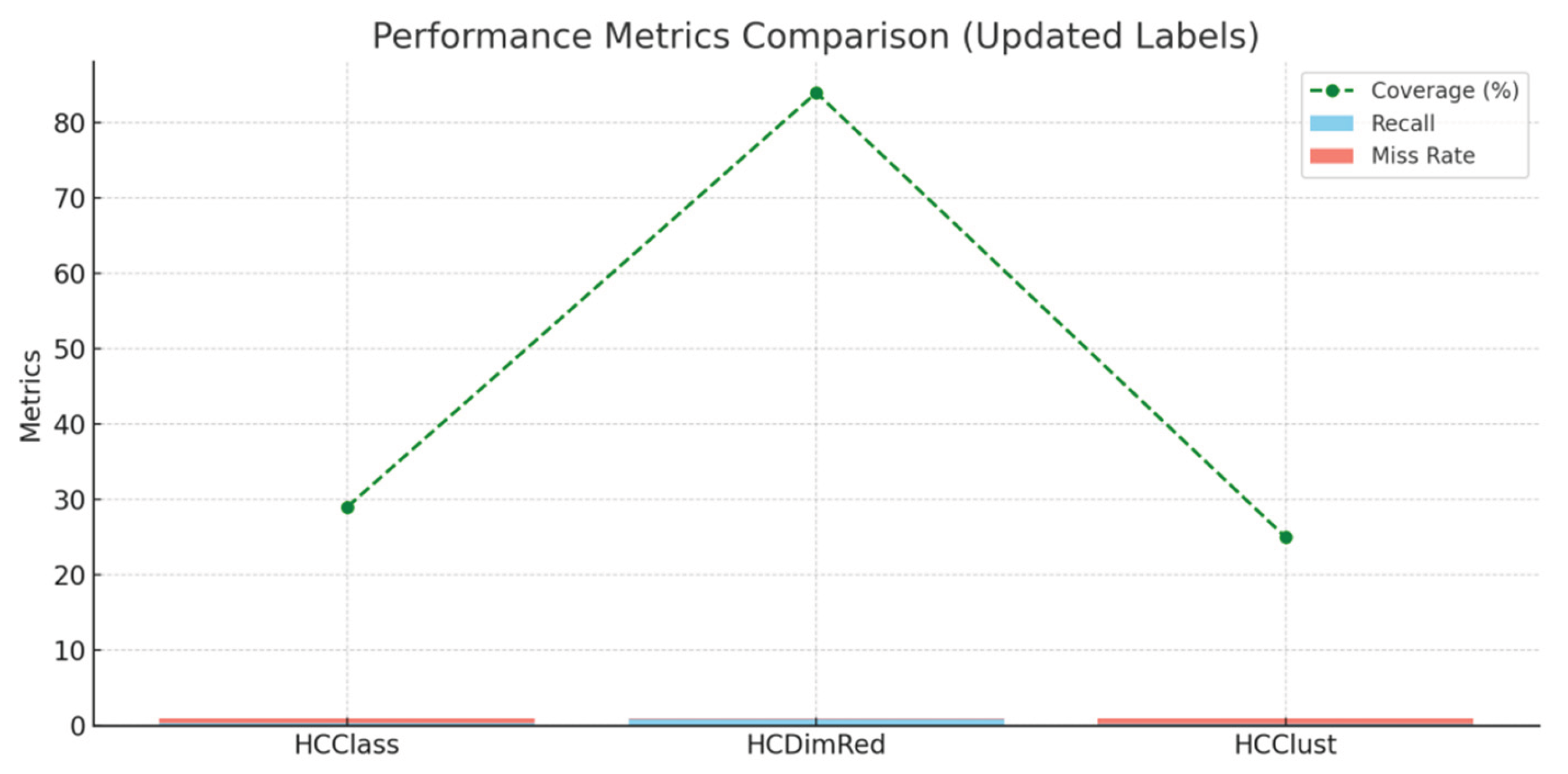

4.3.4. Cloud-Based Network Anomaly Detection

Among cloud-based algorithms, HCDimRed showed superior anomaly detection with an 84.21% recall, outpacing HCClust and HCClass. Each model provided unique insights, further integrated through ensemble fusion. Real-time detection was achieved with processing latency under 0.5 seconds.

Table 5.

Performance Metrics For Cloud-based AD Algorithms.

Table 5.

Performance Metrics For Cloud-based AD Algorithms.

| AD Algorithm |

Detected Anomalies |

Recall |

Miss Rate |

Coverage (%) |

NDS (%) |

| HCClass |

22 |

0.29 |

0.71 |

28.95 |

34.38 |

| HCDimRed |

64 |

0.84 |

0.16 |

84.21 |

100.00 |

| HCClust |

19 |

0.25 |

0.75 |

25.00 |

29.69 |

Figure 7 compares the performance of three cloud-based anomaly detection algorithms—HCClass, HCDimRed, and HCClust—across key metrics: Recall, Miss Rate, and Coverage. HCDimRed stands out with the highest recall (0.84), lowest miss rate (0.16), and the widest coverage (84%), indicating its superior ability to detect anomalies consistently and accurately. In contrast, HCClass and HCClust show significantly lower coverage (29% and 25%, respectively) and higher miss rates, suggesting that these models may overlook a large portion of anomalies.

This supports the preference for HCDimRed in the ISE framework, especially in digital sovereignty contexts where high detection reliability and minimal false negatives are essential for maintaining trust and compliance.

4.3.5. Benchmarking and Evaluation of Model Performance

Extensive benchmarking of ISE was conducted using both real-world financial datasets and synthetically generated fraud scenarios. Performance metrics included accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC-AUC). Across all evaluations, ISE consistently outperformed conventional fraud detection models, particularly in handling class imbalance and rapidly changing behavioral patterns (Pampus & Heisel, 2025) as shown in

Table 6.

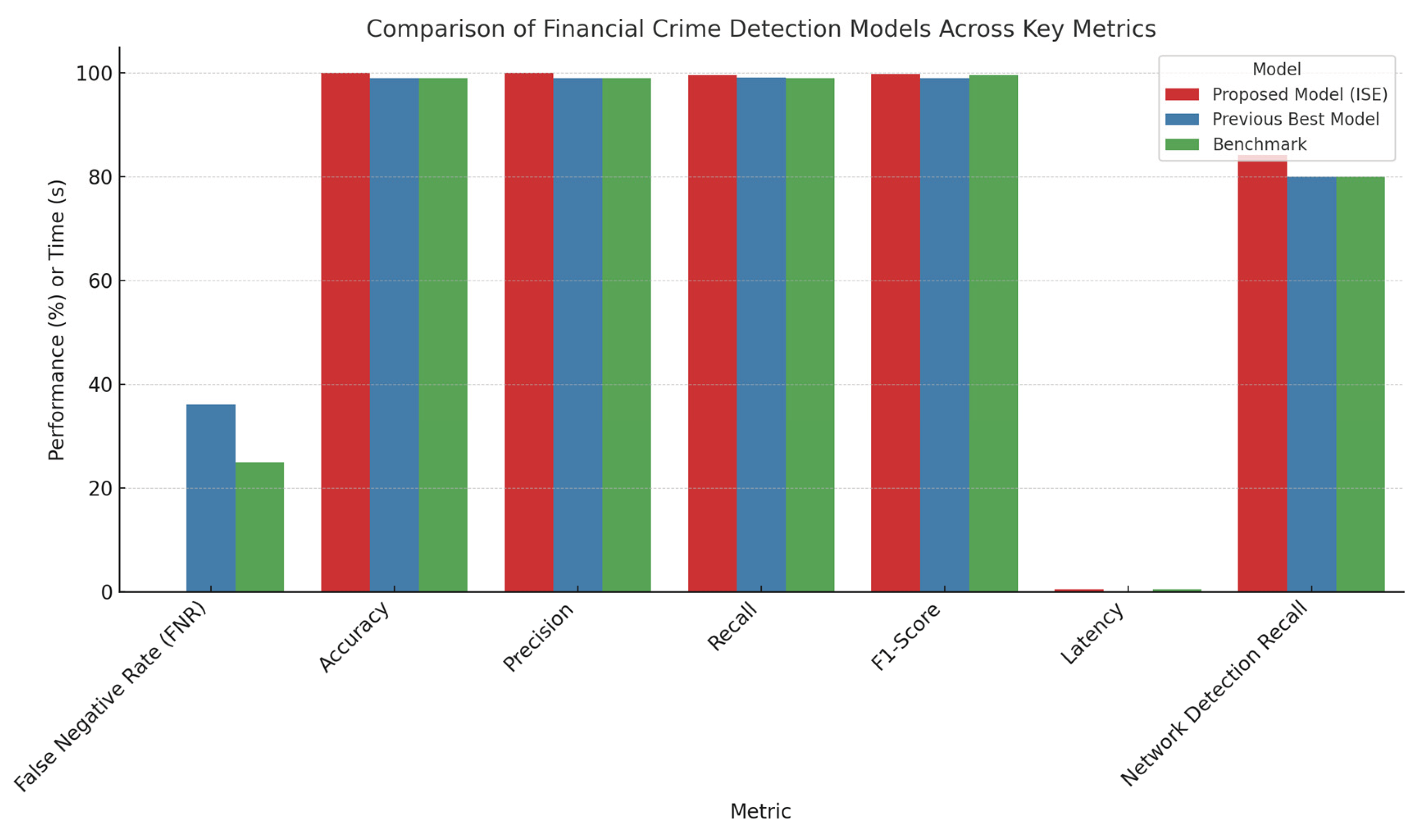

4.3.6. Benchmarking Against Existing Works

Compared to state-of-the-art models, the ISE demonstrated the lowest FNR (0.0%), highest recall (99.55%), and perfect precision (100%). Its real-time processing (≤ 0.5s latency) supports sovereign-compliant deployment without relying on third-party cloud platforms as shown in

Figure 8.

The system demonstrated superior sensitivity to subtle anomalies while maintaining a low false negative rate—a critical factor for minimizing operational disruptions in financial systems. The ensemble learning layer played a pivotal role in enhancing predictive robustness, and the behavior-aware profiling architecture significantly reduced the rate of undetected fraud instances.

5. Contributions to Digital Sovereignty, Legal Compliance, and AI Governance

This work aligns with contemporary digital sovereignty research, including contributions from Iqbal & Ismail (2025) on sovereign AI bias detection, Pandey (2025) on India’s AI sovereignty stack, and Katsikas (2025) on cybersecurity-oriented digital sovereignty architectures, as well as trust policy models by Tith & Colin (2025).

Beyond its technical innovation, ISE represents a significant advancement in the development of AI systems that are aligned with the principles of digital sovereignty and responsible AI governance. By integrating privacy-by-development and compliance-by-development principles into its architecture, ISE provides a replicable model for sovereign AI deployments in sectors such as finance, healthcare, and critical infrastructure—ensuring that deployments meet local legal obligations such as the GDPR in Europe or national AI policy stacks in India.

The proposed ISE architecture reinforces digital sovereignty by ensuring that all AI-based fraud detection operations—from data acquisition to anomaly flagging—are conducted within a sovereign boundary. By leveraging explainable models and auditable ensemble logic, the system ensures full transparency and compliance with regulatory oversight. The use of local computation, human-auditable outputs, and the avoidance of third-party AI inference solutions supports national control over sensitive financial data.

ISE empowers nations to assert control over their digital infrastructure, reduce dependency on foreign surveillance technologies, and build public trust in artificial intelligence. Its transparent, explainable, and auditable architecture meets the growing demand for AI systems that are not only effective but also accountable to democratic institutions and legal systems.

6. Limitations and Ethical Considerations of the Proposed ISE

While the Intelligent Surveillance Engine (ISE) demonstrates significant advancements in sovereign-compliant financial crime detection, certain limitations remain. First, the current framework focuses primarily on structured financial data and may require adaptation to handle unstructured sources such as social media or dark web intelligence. Second, while privacy-preserving AI techniques are incorporated, achieving full homomorphic encryption or zero-knowledge proofs remains a future goal. Third, real-time deployment scalability across multinational jurisdictions with varying sovereignty laws has not yet been extensively tested. Lastly, although bias mitigation strategies are implemented, evolving adversarial threats targeting AI fairness remain a dynamic challenge. These limitations, including legal compliance across jurisdictions, ethical trade-offs in surveillance, and risks of model bias, provide promising avenues for strengthening sovereign AI systems through continued research and transparent audit frameworks.

7. Conclusions and Future Directions on Sovereignty-Centric AI

The Intelligent Surveillance Engine (ISE) presents a sovereign-compliant, AI-driven framework for financial crime detection, validated using real-world and synthetic datasets. ISE achieved a False Negative Rate (FNR) of 0.0%, Recall of 99.55%, and an F1-Score of 99.7%, demonstrating substantial improvements over traditional systems. These results correspond to an 36.11% reduction in FNR, a 34.35% increase in Recall, and an 11.49% gain in F1-Score, highlighting the significance of sovereignty-aware, privacy-preserving AI frameworks in financial surveillance.

The practical implications of this study suggest that financial institutions and government agencies should prioritize the deployment of sovereign-compliant AI frameworks such as ISE. By aligning fraud detection systems with principles of digital sovereignty, organizations can enhance detection capabilities while ensuring data privacy, national control, and ethical governance. This is crucial for maintaining trust and resilience in increasingly digitized economies.

Future work will focus on expanding ISE’s applicability to unstructured data sources such as social media, exploring full integration with sovereign financial auditing systems, and deploying it within national fintech infrastructure with human-in-the-loop oversight. Moreover, the integration of advanced privacy technologies such as homomorphic encryption and zero-knowledge proofs will be explored to further strengthen compliance with sovereignty requirements. Lastly, large-scale real-time testing across multinational environments will be essential to address varying legal and regulatory challenges inherent in sovereign AI deployments.

The ISE framework demonstrates how AI can be both technologically advanced and sovereignty-aligned—offering a scalable solution that upholds national control, transparency, and public trust in the digital age

8. Declaration of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies

During the preparation of this work, the authors utilized AI-assisted tools such as ChatGPT to enhance English language accuracy, including spelling, grammar, and punctuation. The content generated or corrected by these tools was thoroughly reviewed, revised, and edited by the authors to ensure accuracy and originality. The authors accept full responsibility for the originality of the final content of this publication.

References

- Abdullayeva, F. J. (2021). Advanced persistent threat attack detection method in cloud computing based on autoencoder and softmax regression algorithm. Array, 10, 100067.

- Ali, A., Razak, A., S., Othman, H., S., Eisa, T., Al-dhaqm, A., Nasser, M., Elhassan, T., Elshafie, H., Saif, &, & A. (2022). Financial fraud detection based on machine learning: A systematic literature review. 2022.

- Anunita, K. P., Devisri, S. R., & Arumugam, C. (2025). Federated learning: Countering label flipping attack in medical imaging. Procedia Computer Science, 254, 653–660.

- Bühler, M. M., Calzada, I., Cane, I., Jelinek, T., Kapoor, A., Mannan, M., Mehta, S., Micheli, M., Mookerje, V., Nübel, K., Pentland, A., Scholz, T., Siddarth, D., Tait, J., Vaitla, B., & Zhu, J. (2023). Data cooperatives as catalysts for collaboration, data sharing, and the (trans)formation of the digital commons. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Calderaro, A., & Blumfelde, S. (2022). Artificial intelligence and EU security: The false promise of digital sovereignty. European Security, 31(3), 415–434. [CrossRef]

- Calzada, I. (2018). Technological sovereignty: Protecting citizens’ digital rights in the AI-driven and post-GDPR algorithmic and city-regional European realm. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 5(1), 267–289. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A., Gopalakrishnan, S., & Mondal, A. (2025). Sovereignty-aware intrusion detection on streaming data: Automatic machine learning pipeline and semantic reasoning. Procedia Computer Science, 254, 661–668.

- Donnelly, S., Ríos Camacho, E., & Heidebrecht, S. (2024). Digital sovereignty as control: The regulation of digital finance in the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy, 31(8), 2226–2249.

- Fratini, S., Hine, E., Novelli, C., Roberts, H., & Floridi, L. (2024). Digital sovereignty: A descriptive analysis and a critical evaluation of existing models. Digital Society, 3(3), 59.

- Floridi, L. (2020). The fight for digital sovereignty: What it is, and why it matters, especially for the EU. Philosophy & Technology, 33(3), 369–378. [CrossRef]

- Gadal, S., Mokhtar, R., Abdelhaq, M., Alsaqour, R., Ali, E. S., & Saeed, R. (2022). Machine learning-based anomaly detection using K-mean array and sequential minimal optimization. Electronics, 11(14), 2158.

- Gordon, G. (2023). Digital sovereignty, digital infrastructures, and quantum horizons. AI & Society, 39(1), 125–137. [CrossRef]

- Glasze, G., Cattaruzza, A., Douzet, F., Dammann, F., Bertran, M. G., Bômont, C., Braun, M., Danet, D., Desforges, A., Géry, A., & Grumbach, S. (2023). Contested spatialities of digital sovereignty. Geopolitics, 28(2), 919–958.

- Guevara, J., Garcia-Bedoya, O., & Granados, O. (2020). Machine learning methodologies against money laundering in non-banking correspondents. In Applied Informatics: Third International Conference, ICAI 2020, Ota, Nigeria, October 29–31, 2020, Proceedings (Vol. 3, pp. 72–88). Springer International Publishing.

- Hashmi, E., Yamin, M. M., & Yayilgan, S. Y. (2024). Securing tomorrow: A comprehensive survey on the synergy of Artificial Intelligence and information security. AI and Ethics, 1–19.

- Hendaoui, F., Ferchichi, A., Trabelsi, L., Meddeb, R., Ahmed, R., & Khelifi, M. K. (2024). Advances in deep learning intrusion detection over encrypted data with privacy preservation: A systematic review. Cluster Computing, 27(7), 8683–8724.

- Huang, D., Mu, D., Yang, L., Cai, &, & X. (2018). CoDetect: Financial fraud detection with anomaly feature detection. 2018.

- Iqbal, R., & Ismail, S. (2025). Unbiased AI for a sovereign digital future: A bias detection framework. Procedia Computer Science, 254, 685–692.

- Islam, U., Alsadhan, A. A., Alwageed, H. S., Al-Atawi, A. A., Mehmood, G., Ayadi, M., & Alsenan, S. (2024). SentinelFusion based machine learning comprehensive approach for enhanced computer forensics. PeerJ Computer Science, 10, e2183.

- Katsikas, S. K. (2025). Towards a cybersecurity-oriented research agenda for digital sovereignty. Procedia Computer Science, 254, 677–684.

- Klare, M., Hrestic, R., Stelter, A., & Lechner, U. (2025). Digital sovereignty and digital transformation practice recommendation for the software life cycle process. Procedia Computer Science, 254, 645–652.

- Misra, S., Barik, K., & Kvalvik, P. (2025). Digital sovereignty in the era of Industry 5.0. Procedia Computer Science, 254, 661–668.

- Mohaimin, R., M., Sumsuzoha, M., Pabel, H., M. A., Nasrullah, &, & F. (2024). Detecting financial fraud using anomaly detection techniques: A comparative study of machine learning algorithms. 2024.

- Pandey, P. (2025). Digital sovereignty and AI: Developing India’s National AI Stack for strategic autonomy. Procedia Computer Science, 254, 669–676.

- Tith, D., & Colin, J. N. (2025). A trust policy meta-model for trustworthy and interoperability of digital identity systems. Procedia Computer Science, 254, 637–644.

- Pampus, J., & Heisel, M. (2025). Pattern-based requirements elicitation for sovereign data sharing. Procedia Computer Science, 254, 693–700.

- Udayakumar, R., Joshi, A., Boomiga, S. S., & Sugumar, R. (2023). Deep fraud Net: A deep learning approach for cyber security and financial fraud detection and classification. Journal of Internet Services and Information Security, 13(3), 138-157.

- Zegeye, W. K., Dean, R. A., & Moazzami, F. (2019). Multi-layer hidden Markov model based intrusion detection system. Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction, 1(1), 265-286. [CrossRef]

- Zhurkov, A. A. (2023). Topical issues of legal regulation of artificial intelligence in the context of the need to ensure national digital sovereignty during the period of sanctions pressure. Vestnik Universiteta Imeni O.E. Kutafina (MSAL), 102(2), 177–186. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).