Submitted:

13 December 2025

Posted:

15 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

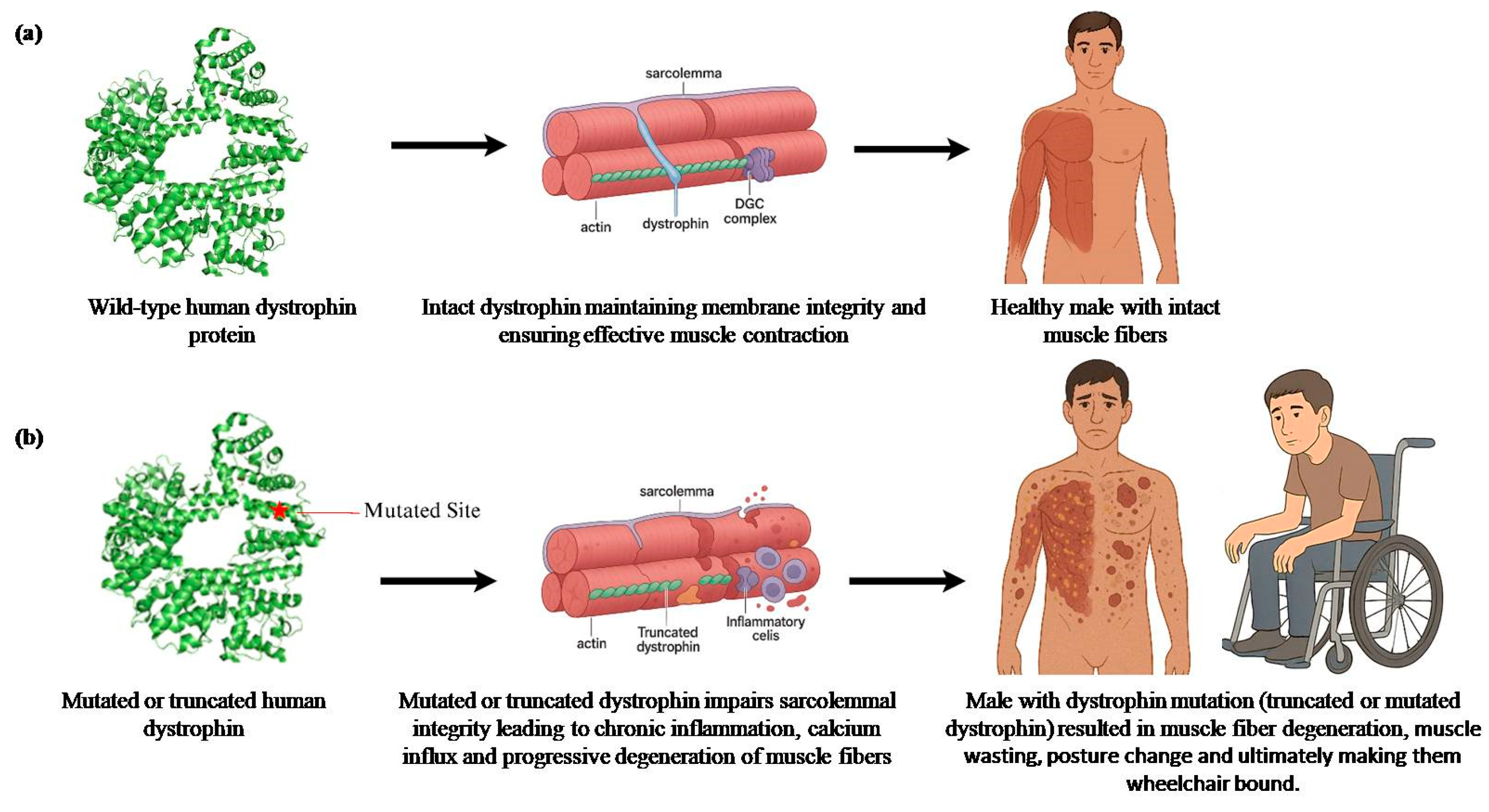

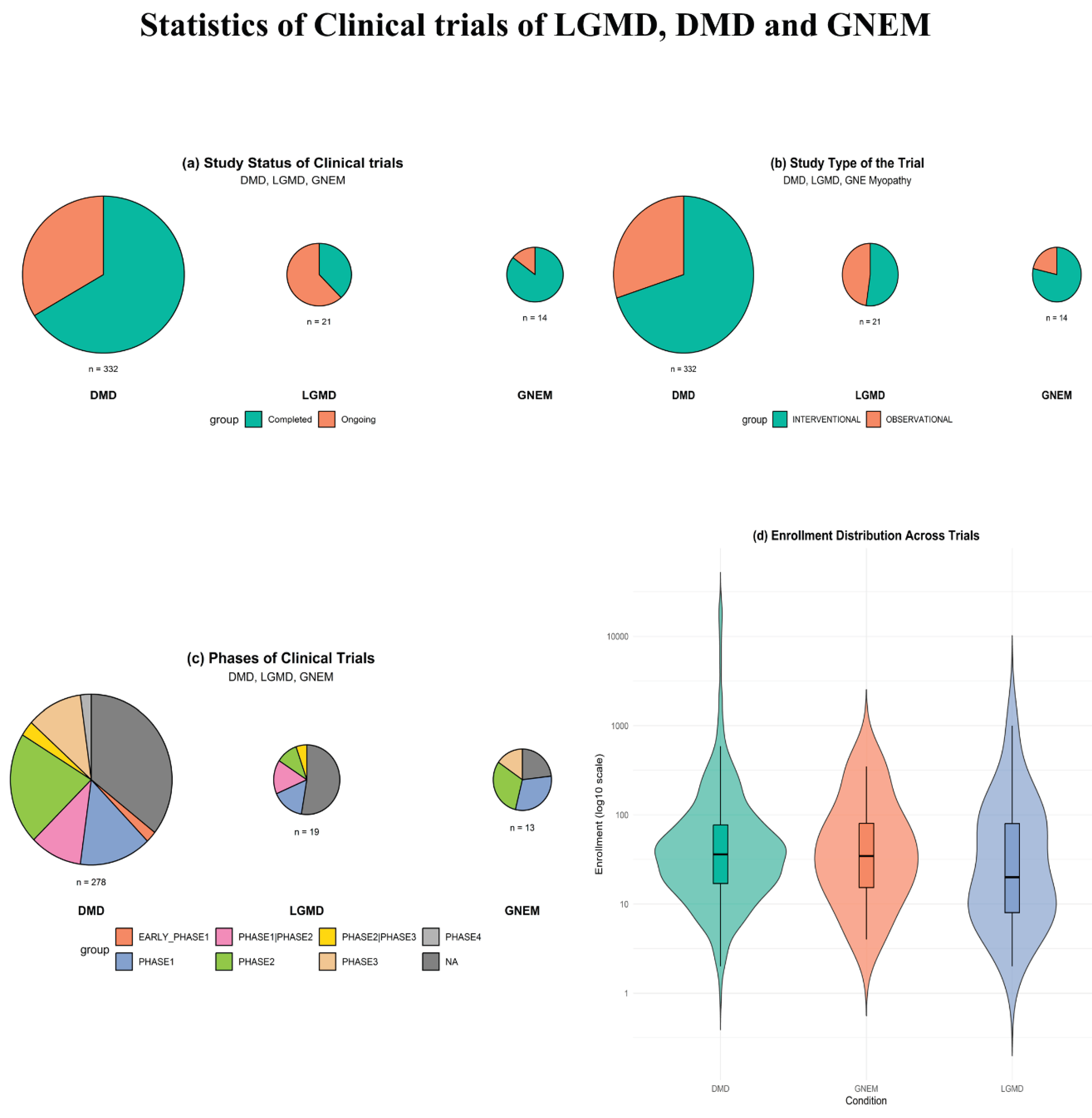

2. Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD)

2.1. Therapies Focused on Symptomatic Management (Palliative Therapies)

2.1.1. Steroid-Based Palliative Therapies

2.1.2. Non-Steroidal Palliative Therapies

2.2. Therapies Focused on Restoring Dystrophin Expression and Function: Gene Therapy and Gene-Targeted Therapy

2.2.1. Read-Through Therapy

2.2.2. Exon Skipping Therapy

2.2.3. Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) Vector-Based Gene Therapy

AAV-NoSTOP Gene Therapy

2.2.4. CRISPR/CAS9

2.2.5. Vector Aided Gene Therapy

2.3. Cell Based Therapy

2.3.1. Re-Engineering Cellular Medicine:

2.3.2. Chimeric Cell Therapy:

2.3.3. One for All Stem Cell-Based Therapy

2.3.4. Muscle Stem Cells (muSCs) and Piezo1 Ion Channels as Potential Therapeutic for Muscular Dystrophies Including DMD

2.4. Therapies Not Limited to Dystrophin Mutation Type

2.4.1. Utrophin Modulators

2.4.2. SERCA as a Therapeutic Target for DMD Cardiomyopathy

2.5. In Vitro Disease Model Systems

3. Limb Girdle Muscular Dystrophies (LGMD)

3.1. Molecular Spectrum of LGMD Mutations in India

3.2. LGMD Supportive and Symptomatic Treatments

3.3. Therapeutic Approaches and Clinical Trials for LGMD

| Mutation | Mutation Type | Gene | Community | Paper |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p.Val727Met | Missense | GNE | Gujarat and Rajasthan | Bhattacharya et al., 2018 [187], Khandilkar et al., 2022 [136] |

3.3.1. Treatment of LGMDR1/2A

Pharmacological and Small Molecule Therapies

- Ubiquitin-proteasome as a therapeutic target for LGMDR1

- SERCA overexpression for LGMDR1 treatment

- Drug therapies for LGMDR1

- Small molecule approach

Gene and Genome Editing Therapies

- Gene therapy approach for LGMDR1

- AAV- mediated therapy

- ATA-200, a gene therapy for LGMD

- CRISPR/Cas9 approach towards LGMDR1

Patient-Specific iPSC-Derived Cellular Models of LGMDR1

3.3.2. Treatment of LGMDR4/2E

Gene and Genome Editing Therapies

Therapeutic Approaches Addressing the Secondary Causes of the Disease

- Redox-sensitive HMGB1 as a therapeutic target in sarcoglycanopathies

- P2X7 receptor blockade as a therapeutic strategy in sarcoglycanopathies

- Inhibition of FAP-driven fibrosis via nintedanib in sarcoglycanopathy models

4. GNE Myopathy (GNEM)

4.1. Early-Stage Trials (2005–2010)

4.2. Extended-Form Sialic Acid and Aceneuramic Acid Extended-Release (Ace-ER) Treatment

4.3. Sialic Acid Precursors

4.3.1. ManNAc and Sialyllactose

4.3.2. ManNAc and Neu5Ac

4.3.3. 6′-Sialyllactose (6SL) Supplements

4.4. ACENOBEL, a Sustained Release of Aceneuramic Acid Tablet Approved in Japan for GNEM

4.5. Gene Delivery Approaches for GNEM

4.6. Other Emerging Strategies

5. Conclusions

6. Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Clinical trial number

Ethics approval

Consent (participation and publication)

Data availability

Code availability

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interests

References

- Aartsma-Rus, Annemieke. "The future of exon skipping for Duchenne muscular dystrophy." Human Gene Therapy 34, no. 9-10 (2023): 372-378. [CrossRef]

- Acharya, S., A.H. Ansari, and P. Kumar Das. “PAM-Flexible Engineered FnCas9 Variants for Robust and Ultra-Precise Genome Editing and Diagnostics.” Nat Commun 15 (2024): 5471. [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, Pooja, Vancha Harish, Sharfuddin Mohd, Sachin Kumar Singh, Devesh Tewari, Ramanjireddy Tatiparthi, Sukriti Vishwas, Srinivas Sutrapu, Kamal Dua, and Monica Gulati. “Role of CRISPR/Cas9 in the Treatment of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy and Its Delivery Strategies.” Life Sciences 330 (2023): 122003. [CrossRef]

- Aguti, Sara, Gian Nicola Gallus, Silvia Bianchi, Simona Salvatore, Anna Rubegni, Gianna Berti, Patrizia Formichi, Nicola Stefano, Alessandro Malandrini, and Diego Lopergolo. “Novel Biomarkers for Limb Girdle Muscular Dystrophy (LGMD.” Cells 13, no. 4 (2024): 329. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.Shafeeq. “Limb-Girdle Muscular Dystrophy in Pregnancy: A Narrative Review.” Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics 310, no. 5 (2024): 2373–86. [CrossRef]

- Aho, Anna Carin, Sally Hultsjö, and Katarina Hjelm. "Young adults’ experiences of living with recessive limb-girdle muscular dystrophy from a salutogenic orientation: An interview study." Disability and rehabilitation 37, no. 22 (2015): 2083-2091. [CrossRef]

- Aitken, Murry, E. J. Mercer, and A. I. I. McKemey. "Understanding Neuromuscular Disease Care." IQVIA Institute. Parsippany, NJ (2018).

- Alhamadani, Feryal, Kristy Zhang, Rajvi Parikh, Hangyu Wu, Theodore P. Rasmussen, Raman Bahal, Xiao-bo Zhong, and José E. Manautou. "Adverse drug reactions and toxicity of the food and drug administration–approved antisense oligonucleotide drugs." Drug Metabolism and Disposition 50, no. 6 (2022): 879-887. [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Pérez, Jorge, Ana Carrasco-Rozas, Maria Borrell-Pages, Esther Fernández-Simón, Patricia Piñol-Jurado, Lina Badimon, Lutz Wollin et al. "Nintedanib reduces muscle fibrosis and improves muscle function of the alpha-sarcoglycan-deficient mice." Biomedicines 10, no. 10 (2022): 2629. [CrossRef]

- Angelini, Corrado, and Elisabetta Tasca. “Fatigue in Muscular Dystrophies.” Neuromuscular Disorders 22 (2012): 214–20.

- Ankala, Arunkanth, Jordan N. Kohn, Rashna Dastur, Pradnya Gaitonde, Satish V. Khadilkar, and Madhuri R. Hegde. “Ancestral Founder Mutations in Calpain-3 in the Indian Agarwal Community: Historical, Clinical, and Molecular Perspective.” Muscle & Nerve 47, no. 6 (2013): 931–37. [CrossRef]

- Argov, Zohar, Yoseph Caraco, Heather Lau, Alan Pestronk, Perry B. Shieh, Alison Skrinar, Tony Koutsoukos, Ruhi Ahmed, Julia Martinisi, and Emil Kakkis. "Aceneuramic acid extended release administration maintains upper limb muscle strength in a 48-week study of subjects with GNE myopathy: results from a phase 2, randomized, controlled study." Journal of neuromuscular diseases 3, no. 1 (2016): 49-66. [CrossRef]

- Assefa, Milyard, Addison Gepfert, Meesam Zaheer, Julia M. Hum, and Brian W. Skinner. "Casimersen (AMONDYS 45™): an antisense oligonucleotide for Duchenne muscular dystrophy." Biomedicines 12, no. 4 (2024): 912. [CrossRef]

- Baeza-Barragán, Maria Rosa, Maria Teresa Labajos Manzanares, Carmen Ruiz Vergara, María Jesús Casuso-Holgado, and Rocío Martín-Valero. “The Use of Virtual Reality Technologies in the Treatment of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: Systematic Review.” JMIR mHealth and uHealth 8, no. 12 (2020): 21576. [CrossRef]

- Bardhan, Mainak, Ram Murthy Anjanappa, Kiran Polavarapu, Veeramani Preethish-Kumar, Seena Vengalil, Saraswati Nashi, Shamita Sanga et al. "Clinical, genetic profile and disease progression of sarcoglycanopathies in a large cohort from India: high prevalence of SGCB c. 544A> C." neurogenetics 23, no. 3 (2022): 187-202. [CrossRef]

- Barton, Elisabeth R., Christina A. Pacak, Whitney L. Stoppel, and Peter B. Kang. “The Ties That Bind: Functional Clusters in Limb-Girdle Muscular Dystrophy.” Skeletal Muscle 10 (2020): 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Basak, Jayasri, Uma B. Dasgupta, Subhash Chandra Mukherjee, Shyamal Kumar Das, Asit Kumar Senapati, and Tapas Kumar Banerjee. “Deletional Mutations of Dystrophin Gene and Carrier Detection in Eastern India.” The Indian Journal of Pediatrics 76 (2009): 1007–12. [CrossRef]

- Baskar, Dipti, Veeramani Preethish-Kumar, Kiran Polavarapu, Seena Vengalil, Saraswati Nashi, Deepak Menon, Valakunja Harikrishna Ganaraja et al. "Clinical and genetic heterogeneity of nuclear envelopathy related muscular dystrophies in an Indian cohort." Journal of Neuromuscular Diseases 11, no. 5 (2024): 969-979. [CrossRef]

- Bello, L., P. Campadello, A. Barp, M. Fanin, C. Semplicini, G. Sorarù, L. Caumo, C. Calore, C. Angelini, and E. Pegoraro. “Functional Changes in Becker Muscular Dystrophy: Implications for Clinical Trials in Dystrophinopathies.” Sci. Rep 6 (2016): 32439. [CrossRef]

- Bernareggi, Annalisa, Alessandra Bosutti, Gabriele Massaria, Rashid Giniatullin, Tarja Malm, Marina Sciancalepore, and Paola Lorenzon. "The state of the art of Piezo1 channels in skeletal muscle regeneration." International journal of molecular sciences 23, no. 12 (2022): 6616. [CrossRef]

- Berns, K.I., and N. Muzyczka. “AAV: An Overview of Unanswered Questions.” Hum Gene Ther 28 (2017): 308–13. [CrossRef]

- BeytíaMdeL, Vry J., and Kirschner J. “Drug Treatment of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: Available Evidence and Perspectives.” Acta Myol 31 (2012): 4–8.

- Bhattacharya, Sudha, Satish V. Khadilkar, Atchayaram Nalini, Aparna Ganapathy, Ashraf U. Mannan, Partha P. Majumder, and Alok Bhattacharya. “Mutation Spectrum of GNE Myopathy in the Indian Sub-Continent.” Journal of Neuromuscular Diseases 5, no. 1 (2018): 85–92. [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, B., D.J. Matthews, G.H. Clayton, and T. Carry. “Corticosteroid Treatment and Functional Improvement in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: Long-Term Effect.” Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil 84 (2005): 843–50.

- Birnkrant, D.J., K. Bushby, C.M. Bann, B.A. Alman, S.D. Apkon, A. Blackwell, L.E. Case, L. Cripe, S. Hadjiyannakis, and A.K. Olson. “Diagnosis and Management of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy, Part 2: Respiratory, Cardiac, Bone Health, and Orthopaedic Management.” Lancet Neurol 17 (2018): 347–61. [CrossRef]

- Bladen, C.L. “The TREAT-NMD DMD Global Database: Analysis of More than 7000 Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Mutations.” Hum. Mutat 36, no. 4 (2015): 395–402. [CrossRef]

- Blake, Derek J., Jonathon M. Tinsley, and Kay E. Davies. "Utrophin: a structural and functional comparison to dystrophin." Brain pathology 6, no. 1 (1996): 37-47. [CrossRef]

- Blake, Derek J., Jonathon M. Tinsley, and Kay E. Davies. "Utrophin: a structural and functional comparison to dystrophin." Brain pathology 6, no. 1 (1996): 37-47. [CrossRef]

- Blandin, Gaëlle, Sylvie Marchand, Karine Charton, Nathalie Danièle, Evelyne Gicquel, Jean-Baptiste Boucheteil, and AzéddineBentaib. “A Human Skeletal Muscle Interactome Centered on Proteins Involved in Muscular Dystrophies: LGMD Interactome.” Skeletal Muscle 3 (2013): 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Blau, H.M., C. Webster, and G.K. Pavlath. “Defective myoblasts identified in Duchenne muscular dystrophy.” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 80 (1983): 4856–60. [CrossRef]

- Bostick, B. “AAV Micro-Dystrophin Gene Therapy Alleviates Stress-Induced Cardiac Death but Not Myocardial Fibrosis in >21-Mold Mdx Mice, an End-Stage Model of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Cardiomyopathy.” J. Mol. Cell Cardiol 53 (2012): 217–22. [CrossRef]

- Bouchard, Camille, and Jacques P. Tremblay. “Limb–Girdle Muscular Dystrophies Classification and Therapies.” Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 14 (2023): 4769. [CrossRef]

- Braun, Serge. "Duchenne muscular dystrophy, one of the most complicated diseases for gene therapy." Journal of Translational Genetics and Genomics 9, no. 1 (2025): 35-47. [CrossRef]

- Bushby, K., R. Finkel, D.J. Birnkrant, L.E. Case, P.R. Clemens, L. Cripe, A. Kaul, K. Kinnett, C. McDonald, and S. Pandya. “Diagnosis and Management of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy, Part 1: Diagnosis, and Pharmacological and Psychosocial Management.” Lancet Neurol 9 (2010): 77–93. [CrossRef]

- Careccia, G., M. Saclier, and M. Tirone. “Rebalancing Expression of HMGB1 Redox Isoforms to Counteract Muscular Dystrophy.” Sci Transl Med 13, no. 596 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, Nuria, May C. Malicdan, and Marjan Huizing. “GNE Myopathy: Etiology, Diagnosis, and Therapeutic Challenges.” Neurotherapeutics 15, no. 4 (2018): 900–914. [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, Nuria, May C. Malicdan, Petcharat Leoyklang, Joseph A. Shrader, Galen Joe, Christina Slota, John Perreault et al. "Safety and efficacy of N-acetylmannosamine (ManNAc) in patients with GNE myopathy: an open-label phase 2 study." Genetics in Medicine 23, no. 11 (2021): 2067-2075. [CrossRef]

- Chaouch, Amina, Kathryn M. Brennan, Judith Hudson, Cheryl Longman, John McConville, Patrick J. Morrison, Maria E. Farrugia et al. "Two recurrent mutations are associated with GNE myopathy in the North of Britain." Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 85, no. 12 (2014): 1359-1365. [CrossRef]

- Chemello, F., A.C. Chai, H. Li, C. Rodriguez-Caycedo, E. Sanchez-Ortiz, A. Atmanli, A.A. Mireault, N. Liu, R. Bassel-Duby, and E.N. Olson. “Precise Correction of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Exon Deletion Mutations by Base and Prime Editing.” Sci. Adv 7 (2021): 4910. [CrossRef]

- Cho, Anna, May Christine, V. Malicdan, Miho Miyakawa, Ikuya Nonaka, Ichizo Nishino, and Satoru Noguchi. "Sialic acid deficiency is associated with oxidative stress leading to muscle atrophy and weakness in GNE myopathy." Human molecular genetics 26, no. 16 (2017): 3081-3093. [CrossRef]

- Chwalenia, Katarzyna, Vivi-Yun Feng, Nicole Hemmer, Hans J. Friedrichsen, Ioulia Vorobieva, Matthew JA Wood, and Thomas C. Roberts. "AAV microdystrophin gene replacement therapy for Duchenne muscular dystrophy: progress and prospects." Gene Therapy (2025): 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Chulanova, Yulia, Dor Breier, and Dan Peer. “Delivery of Genetic Medicines for Muscular Dystrophies.” Cell Reports Medicine, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Crisafulli, S., J. Sultana, A. Fontana, F. Salvo, S. Messina, and G. Trifirò. “Global Epidemiology of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Orphanet J Rare Dis 15, no. 141 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Crowe, K.E., D.A. Zygmunt, and K. Heller. “Visualizing Muscle Sialic Acid Expression in the GNED207VTgGne-/- Cmah-/- Model of GNE Myopathy: A Comparison of Dietary and Gene Therapy Approaches.” J Neuromuscul Dis 9 (2021): 53–71. [CrossRef]

- D’Este, Giorgia, Mattia Spagna, Sara Federico, Luisa Cacciante, Błażej Cieślik, Pawel Kiper, and Rita Barresi. Limb-girdle Muscular Dystrophies: A Scoping Review and Overview of Currently Available Rehabilitation Strategies. Muscle & Nerve, n.d. [CrossRef]

- Dahl, Russell, and Ilya Bezprozvanny. "SERCA pump as a novel therapeutic target for treating neurodegenerative disorders." Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 734 (2024): 150748. [CrossRef]

- Darin, N., A-K. Kroksmark, A-C. Åhlander, A-R. Moslemi, A. Oldfors, and M. Tulinius. "Inflammation and response to steroid treatment in limb-girdle muscular dystrophy 2I." European Journal of Paediatric Neurology 11, no. 6 (2007): 353-357. [CrossRef]

- Davies, K., A. Philippidis, and R. Barrangou. “Five Years of Progress in CRISPR Clinical Trials (2019-2024.” CRISPR J 7, no. 5 (2024): 227–30. [CrossRef]

- De Masi, Claudia, Paola Spitalieri, Michela Murdocca, Giuseppe Novelli, and Federica Sangiuolo. "Application of CRISPR/Cas9 to human-induced pluripotent stem cells: from gene editing to drug discovery." Human genomics 14 (2020): 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Del Rio-Pertuz, G., C. Morataya, K. Parmar, S. Dubay, and E. Argueta-Sosa. “Dilated Cardiomyopathy as the Initial Presentation of Becker Muscular Dystrophy: A Systematic Review of Published Cases.” Orphanet J. Rare Dis 17 (2022): 194. [CrossRef]

- Donovan, J., H. Phan, A. Russell, B. Barthel, L. Thaler, N. Kilburn, M. Amato, and J. MacDougall. "351P Sevasemten, a fast myosin inhibitor, in adults with Becker muscular dystrophy results in reduced muscle damage biomarkers and functional stabilization." Neuromuscular Disorders 43 (2024): 104441-682. [CrossRef]

- Donovan, Joanne, Jeffrey A. Silverman, Ben Barthel, Michael DuVall, Molly Madden, James MacDougall, Nicole Rempel Kilburn et al. "A Phase 1, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Sevasemten (EDG-5506), a Selective Modulator of Fast Skeletal Muscle Contraction, in Healthy Volunteers and Adults With Becker Muscular Dystrophy." Muscle & Nerve (2025). [CrossRef]

- Duan, Dongsheng, Nathalie Goemans, Shin’ichi Takeda, Eugenio Mercuri, and Annemieke Aartsma-Rus. “Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy.” Nature Reviews Disease Primers 7, no. 1 (2021): 13. [CrossRef]

- E, Vasterling M., Maitski R. J, and Davis B. A. “AMONDYS 45 (Casimersen), a Novel Antisense Phosphorodiamidate Morpholino Oligomer: Clinical Considerations for Treatment in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy.” Cureus 15, no. 12 (December 28, 2023): 51237. [CrossRef]

- Emami, Michael R., Courtney S. Young, Ying Ji, Xiangsheng Liu, Ekaterina Mokhonova, April D. Pyle, Huan Meng, and Melissa J. Spencer. “Polyrotaxane Nanocarriers Can Deliver CRISPR/Cas9 Plasmid to Dystrophic Muscle Cells to Successfully Edit the DMD Gene.” Advanced Therapeutics 2, no. 7 (2019): 1900061. [CrossRef]

- Ervasti, James M., and Kevin P. Campbell. “Membrane Organization of the Dystrophin-Glycoprotein Complex.” Cell 66, no. 6 (1991): 1121–31. [CrossRef]

- Falzarano, Maria Sofia, Chiara Scotton, Chiara Passarelli, and Alessandra Ferlini. “Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: From Diagnosis to Therapy.” Molecules 20, no. 10 (2015): 18168–84. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, José AL, Tâmara HR Prandini, Maria da Conceicao A. Castro, Thales D. Arantes, Juliana Giacobino, Eduardo Bagagli, and Raquel C. Theodoro. "Evolution and application of inteins in Candida species: a review." Frontiers in Microbiology 7 (2016): 1585. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Simón, Esther, Xavier Suárez-Calvet, Ana Carrasco-Rozas, Patricia Piñol-Jurado, Susana López-Fernández, Gemma Pons, Joan Josep Bech Serra et al. "RhoA/ROCK2 signalling is enhanced by PDGF-AA in fibro-adipogenic progenitor cells: implications for Duchenne muscular dystrophy." Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle 13, no. 2 (2022): 1373-1384. [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M.E., E. Bovo, and R. Aguayo-Ortiz. “Dwarf Open Reading Frame (DWORF) Is a Direct Activator of the Sarcoplasmic Reticulum Calcium Pump SERCA.” Elife 10:e65545 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Flanigan, K.M. “Mutational Spectrum of DMD Mutations in Dystrophinopathy Patients: Application of Modern Diagnostic Techniques to a Large Cohort.” Hum. Mutat 30, no. 12 (2009): 1657–66. [CrossRef]

- Francis, Amirtharaj, Balaraju Sunitha, Kandavalli Vinodh, Kiran Polavarapu, Shiva Krishna Katkam, M.M.Srinivas Bharath Sailesh Modi, Narayanappa Gayathri, Atchayaram Nalini, and Kumarasamy Thangaraj. “Novel TCAP mutation c. 32C> A causing limb girdle muscular dystrophy 2G.” PLoS One 9, no. 7 (2014): 102763. [CrossRef]

- G., Dayanithi, Richard I., Viero C., Mazuc E., Mallie S., and Valmier J. “Alteration of Sarcoplasmic ReticulumCa2+Release in Skeletal Muscle from Calpain 3-Deficient Mice.” Int. J. Cel Biol, 2009, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Ganaraja, Valakunja H., Kiran Polavarapu, Mainak Bardhan, Veeramani Preethish-Kumar, Shingavi Leena, Ram M. Anjanappa, and Seena Vengalil. “Disease Progression and Mutation Pattern in a Large Cohort of LGMD R1/LGMD 2A Patients from India.” Global Medical Genetics 9, no. 01 (2022): 034–041. [CrossRef]

- Gazzerro, Elisabetta. "Role of Extracellular ATP in the Progression of Muscle Damage in Sarcoglycanopathies." PhD diss., 2021.

- Ghosh, S., M.U. Arshi, and S. Ghosh. “Discovery of Quinazoline and Quinoline-Based Small Molecules as Utrophin Upregulators via AhR Antagonism for the Treatment of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy.” J Med Chem 67, no. 11 (2024): 9260–76. [CrossRef]

- Goyal, Manisha, Ashok Gupta, Kamlesh Agarwal, Seema Kapoor, and Somesh Kumar. “Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: Genetic and Clinical Profile in the Population of Rajasthan, India.” Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology 24, no. 6 (2021): 873–78.

- Graustein, Andrew, Hugo Carmona, and Joshua O. Benditt. “Noninvasive Respiratory Assistance as Aid for Respiratory Care in Neuromuscular Disorders.” Frontiers in Rehabilitation Sciences 4 (2023): 1152043. [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, Oskar, Supriya Krishna, Sophia Borate, Marziyeh Ghaeidamini, Xiuming Liang, Osama Saher, Raul Cuellar et al. "Advanced Peptide Nanoparticles Enable Robust and Efficient delivery of gene editors across cell types." bioRxiv (2024): 2024-11. [CrossRef]

- Heydemann, Ahlke, Grzegorz Bieganski, Jacek Wachowiak, Jarosław Czarnota, Adam Niezgoda, Krzysztof Siemionow, Anna Ziemiecka et al. "Dystrophin Expressing Chimeric (DEC) cell therapy for Duchenne muscular dystrophy: A first-in-human study with minimum 6 months follow-up." Stem Cell Reviews and Reports 19, no. 5 (2023): 1340-1359. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, P.D., E.S. Lander, and F. Zhang. “Development and Applications of CRISPR-Cas9 for Genome Engineering.” Cell 157 (2014): 1262–78. [CrossRef]

- I., Richard, Broux O., Allamand V., Fougerousse F., Chiannilkulchai N., and Bourg N. “Mutations in the Proteolytic Enzyme Calpain 3 Cause Limb-Girdle Muscular Dystrophy Type 2A.” Cell 81, no. 1 (1995): 27-40. [CrossRef]

- Indian Genome Variation Consortium+ 91-11-27667806+ 91-11-27667471 skb@ igib. res. in. "The Indian genome variation database (IGVdb): a project overview." Human genetics 118 (2005): 1-11.

- Iolascon, Giovanni, Marco Paoletta, Sara Liguori, Claudio Curci, and Antimo Moretti. “Neuromuscular Diseases and Bone.” Frontiers in Endocrinology 10 (2019): 794. [CrossRef]

- J, Keam S. “Vamorolone: First Approval.” Drugs 84, no. 1 (2024): 111–17. [CrossRef]

- Kang, Soojeong, Russell Dahl, Wilson Hsieh, Andrew Shin, Krisztina M. Zsebo, Christoph Buettner, Roger J. Hajjar, and Djamel Lebeche. "Small molecular allosteric activator of the sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) attenuates diabetes and metabolic disorders." Journal of Biological Chemistry 291, no. 10 (2016): 5185-5198. [CrossRef]

- Kawakami, Y., W.S. Hambright, and K. Takayama. “Rapamycin Rescues Age-Related Changes in Muscle-Derived Stem/Progenitor Cells from Progeroid Mice.” Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 14 (2019): 64–76. [CrossRef]

- Keeling, K.M., X. Xue, G. Gunn, and D.M. Bedwell. “Therapeutics Based on Stop Codon Readthrough.” Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 15 (2014): 371–94. [CrossRef]

- Khadilkar, S.V., B.R.R. Nallamilli, and A. Bhutada. “A Report on GNE Myopathy: Individuals of Rajasthan Ancestry Share the Roma Gene.” J Neurol Sci 375 (2017): 239–40. [CrossRef]

- Khadilkar, Satish V. "Limb girdle muscular dystrophies in India." Neurology India 63, no. 4 (2015): 495-496. [CrossRef]

- Khadilkar, Satish V., Chetan R. Chaudhari, Rashna S. Dastur, Pradnya S. Gaitonde, and Jayendra G. Yadav. “Limb-Girdle Muscular Dystrophy in the Agarwals: Utility of Founder Mutations in CAPN3 Gene.” Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology 19, no. 1 (2016): 108–11. [CrossRef]

- Khadilkar, Satish Vasant, Hiral Amrut Halani, Rashna Dastur, Pradnya Satish Gaitonde, Harsh Oza, and Madhuri Hegde. “Genetic Appraisal of Hereditary Muscle Disorders in a Cohort from Mumbai, India.” Journal of Neuromuscular Diseases 9, no. 4 (2022): 571–80. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Minse, Youngwoo Hwang, Seongyu Lim, Hyeon-Ki Jang, and Hyun-Ouk Kim. “Advances in nanoparticles as non-viral vectors for efficient delivery of CRISPR/Cas9.” Pharmaceutics 16, no. 9 (2024): 1197. [CrossRef]

- Kiper, Pawel, Sara Federico, Joanna Szczepańska-Gieracha, Patryk Szary, Adam Wrzeciono, Justyna Mazurek, and Carlos Luque-Moreno. “A Systematic Review on the Application of Virtual Reality for Muscular Dystrophy Rehabilitation: Motor Learning Benefits.” Life 14, no. 7 (2024): 790. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Prasann, and Padmanabh Dwivedi. “Diagnosis of Neuromuscular Disorder.” In Computational Intelligence for Genomics Data, 225–40. Academic Press, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Laing, Nigel G. “Genetics of Neuromuscular Disorders.” Critical Reviews in Clinical Laboratory Sciences 49, no. 2 (2012): 33–48. [CrossRef]

- Landfeldt, E., C. Lindberg, and T. Sejersen. “Improvements in Health Status and Utility Associated with Ataluren for the Treatment of Nonsense Mutation Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy.” Muscle Nerve 61 (2020): 363–68. [CrossRef]

- Lasa-Elgarresta, Jaione, Laura Mosqueira-Martín, Neia Naldaiz-Gastesi, Amets Sáenz, Adolfo Lopez de Munain, and Ainara Vallejo-Illarramendi. "Calcium mechanisms in limb-girdle muscular dystrophy with CAPN3 mutations." International journal of molecular sciences 20, no. 18 (2019): 4548. [CrossRef]

- Laurent, M., M. Geoffroy, G. Pavani, and S. Guiraud. “CRISPR-Based Gene Therapies: From Preclinical to Clinical Treatments.” Cells 13, no. 10 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Lee, H., J. Song, I.S. Kang, J. Huh, J.A. Yoon, and Y.B. Shin. “Early Prophylaxis of Cardiomyopathy with Beta-Blockers and Angiotensin Receptor Blockers in Patients with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy.” Clin. Exp. Pediatr 65 (2022): 507–9. [CrossRef]

- Lim, K.R., R. Maruyama, and T. Yokota. “Eteplirsen in the Treatment of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy.” Drug Design, Development and Therapy 11 (2017): 533–45. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., J. Campagna, and V. John. “A Small-Molecule Approach to Restore a Slow-Oxidative Phenotype and Defective CaMKIIβ Signaling in Limb Girdle Muscular Dystrophy.” Cell Rep Med 1, no. 7 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Liu, Wei, Sander Pajusalu, Nicole J. Lake, Geyu Zhou, Nilah Ioannidis, Plavi Mittal, and Nicholas E. Johnson. “Estimating Prevalence for Limb-Girdle Muscular Dystrophy Based on Public Sequencing Databases.” Genetics in Medicine 21, no. 11 (2019): 2512–20. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Wei, Sander Pajusalu, Nicole J. Lake, Geyu Zhou, Nilah Ioannidis, Plavi Mittal, Nicholas E. Johnson et al. "Estimating prevalence for limb-girdle muscular dystrophy based on public sequencing databases." Genetics in Medicine 21, no. 11 (2019): 2512-2520. [CrossRef]

- LochmüllerH, Behin A., and Caraco Y. “A Phase 3 Randomized Study Evaluating Sialic Acid Extended-Release for GNE Myopathy.” Neurology 92, no. 18 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Luo, H., C. Zhou, and J. Chi. “The Role of Tauroursodeoxycholic Acid on Dedifferentiation of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells by Modulation of Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and as an Oral Drug Inhibiting In-Stent Restenosis.” Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 33, no. 1 (2019): 25–33. [CrossRef]

- M, Hoy S. “DelandistrogeneMoxeparvovec: First Approval.” Drugs 83, no. 14 (2023): 1323–29. [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.S., X.L. Gong, and W.X. Li. “Missense mutation of c.635 T > C in CAPN3 impairs muscle injury repair in a Limb-Girdel Muscular Dystropy Model.” Clin Genet 103, no. 6 (2023): 663–71. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Nuoying, Delia Chen, Ji-Hyung Lee, Paola Kuri, Edward Blake Hernandez, Jacob Kocan, Hamd Mahmood, Elisia D. Tichy, Panteleimon Rompolas, and Foteini Mourkioti. "Piezo1 regulates the regenerative capacity of skeletal muscles via orchestration of stem cell morphological states." Science advances 8, no. 11 (2022): eabn0485. [CrossRef]

- Machha, Pratheusa, Amirtha Gopalan, Yamini Elangovan, Sarath Chandra Mouli Veeravalli, Divya Tej Sowpati, and Kumarasamy Thangaraj. "Endogamy and high prevalence of deleterious mutations in India: evidence from strong founder events." Journal of Genetics and Genomics 52, no. 4 (2025): 570-582. [CrossRef]

- Malicdan, M.C., S. Noguchi, Y.K. Hayashi, I. Nonaka, and I. Nishino. “Prophylactic Treatment with Sialic Acid Metabolites Precludes the Development of the Myopathic Phenotype in the DMRV-hIBM Mouse Model.” Nat Med 15, no. 6 (2009): 690–95. [CrossRef]

- Malicdan, May Christine V., Satoru Noguchi, Yukiko K. Hayashi, Ikuya Nonaka, and Ichizo Nishino. "Prophylactic treatment with sialic acid metabolites precludes the development of the myopathic phenotype in the DMRV-hIBM mouse model." Nature medicine 15, no. 6 (2009): 690-695. [CrossRef]

- Manjunath, V., S.G. Thenral, B.R. Lakshmi, A.Bassi Atchayaram Nalini, K.Priya Karthikeyan, and K. Piyusha. “Large Region of Homozygous (ROH) Identified in Indian Patients with Autosomal Recessive Limb-Girdle Muscular Dystrophy with p. Thr182Pro Variant in SGCB Gene.” Human Mutation, no. 1 (2023): 4362273. [CrossRef]

- Mary, P., Laurent Servais, and Raphaël Vialle. “Neuromuscular Diseases: Diagnosis and Management.” Orthopaedics& Traumatology: Surgery & Research 104, no. 1 (2018): 89–95. [CrossRef]

- Mateos-Aierdi, A.J., M. Dehesa-Etxebeste, and M. Goicoechea. “Patient-Specific iPSC-Derived Cellular Models of LGMDR1.” Stem Cell Res 53, no. 102333 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Matthews, E., R. Brassington, T. Kuntzer, F. Jichi, and A.Y. Manzur. “Corticosteroids for the Treatment of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy.” Cochrane Database Syst. Rev, 2016, 003725. [CrossRef]

- Mavrommatis, L., A. Zaben, and U. Kindler. “CRISPR/Cas9 Genome Editing in LGMD2A/R1 Patient-Derived Induced Pluripotent Stem and Skeletal Muscle Progenitor Cells.” Stem Cells Int 2023, no. 9246825 (2023). [CrossRef]

- McDonald, C.M., G. Sajeev, Z. Yao, E. McDonnell, G. Elfring, M. Souza, S.W. Peltz, et al. “Deflazacort vs Prednisone Treatment for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: A Meta-Analysis of Disease Progression Rates in Recent Multicenter Clinical Trials.” Muscle & Nerve 61, no. 1 (2020): 26–35. [CrossRef]

- Mendell, J.R., L.R. Rodino-Klapac, Z. Sahenk, K. Roush, L. Bird, L.P. Lowes, L. Alfano, et al. “Eteplirsen for the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy.” Annals of neurology 74, no. 5 (2013): 637–47. [CrossRef]

- Mendell, Pozsgai, JR, Lewis ER, and S. “Gene Therapy with Bidridistrogenexeboparvovec for Limb-Girdle Muscular Dystrophy Type 2E/R4: Phase 1/2 Trial Results.” Nat Med 30, no. 1 (2024): 199–206. [CrossRef]

- Mercuri, E., F. Muntoni, and A.N. Osorio. “Safety and Effectiveness of Ataluren: Comparison of Results from the STRIDE Registry and CINRG DMD Natural History Study.” J Comp Eff Res 9 (2020): 341–60. [CrossRef]

- Mitrani-Rosenbaum, S., L. Yakovlev, and M. Becker Cohen. “Sustained Expression and Safety of Human GNE in Normal Mice after Gene Transfer Based on AAV8 Systemic Delivery.” NeuromusculDisord 22 (2012): 1015–24. [CrossRef]

- Mizobe, Y., S. Miyatake, H. Takizawa, Y. Hara, T. Yokota, A. Nakamura, S. Takeda, and Y. Aoki. “In Vivo Evaluation of Single-Exon and Multiexon Skipping in Mdx52 Mice.” Methods Mol. Biol, 2018, 275–92.

- Molaei, Negar, Parnian Alagha, Ali Khanbazi, Maryam Beheshtian, Fatemeh Ahangari, Shima Dehdahsi, Mahsa Fadaee et al. "Genetic spectrum among 2009 Iranian individuals with neuromuscular disorders using next generation sequencing and multiple ligation dependent probe amplification methods." Scientific Reports 15, no. 1 (2025): 42736. [CrossRef]

- Morales, E.D., Y. Yue, and T.B. Watkins. “Dwarf Open Reading Frame (DWORF) Gene Therapy Ameliorated Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Cardiomyopathy in Aged Mdx Mice.” J Am Heart Assoc 12, no. 3 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Mori-Yoshimura, M., N. Suzuki, and M. Katsuno. “Efficacy Confirmation Study of Aceneuramic Acid Administration for GNE Myopathy in Japan.” Orphanet J Rare Dis 18 (2023): 241. [CrossRef]

- Mullen, Jeffrey, Khalid Alrasheed, and Tahseen Mozaffar. "GNE myopathy: History, etiology, and treatment trials." Frontiers in Neurology 13 (2022): 1002310. [CrossRef]

- Muni-Lofra, Robert, Eduard Juanola-Mayos, Marianela Schiava, Dionne Moat, Maha Elseed, Jassi Michel-Sodhi, and Elizabeth Harris. “Longitudinal Analysis of Respiratory Function of Different Types of Limb Girdle Muscular Dystrophies Reveals Independent Trajectories.” Neurology: Genetics 9, no. 4 (2023): 200084. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, Alexander Peter, and Volker Straub. “The Classification, Natural History and Treatment of the Limb Girdle Muscular Dystrophies.” Journal of Neuromuscular Diseases 2, no. s2 (2015): 7–19. [CrossRef]

- N, Elangkovan, and Dickson G. “Gene Therapy for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy.” J Neuromuscul Dis 8:S303–S316 (2021).

- N, Lamb Y. “Givinostat: First Approval.” In Drugs, 10.1007/S40265-024-02052-1. Advance Online Publication, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Nagabushana, Divya, Kiran Polavarapu, Mainak Bardhan, Gautham Arunachal, Swetha Gunasekaran, Veeramani Preethish-Kumar, and Ram Murthy Anjanappa. “Comparison of the Carrier Frequency of Pathogenic Variants of DMD Gene in an Indian Cohort.” Journal of Neuromuscular Diseases 8, no. 4 (2021): 525–35. [CrossRef]

- Nallamilli, Babi Ramesh Reddy, Samya Chakravorty, Akanchha Kesari, Alice Tanner, Thomas Schneider ArunkanthAnkala, and Cristina Silva. “Genetic Landscape and Novel Disease Mechanisms from a Large LGMD Cohort of 4656 Patients.” Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology 5, no. 12 (2018): 1574–87.

- Narayanaswami, P. “Evidence-Based Guideline Summary?: Diagnosis and Treatment of Limb-Girdle and Distal Dystrophies.” Neurology, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Serna, S., A. Hachem, and A. Canha-Gouveia. “Generation of Nonmosaic, Two-Pore Channel 2 Biallelic Knockout Pigs in One Generation by CRISPR-Cas9 Microinjection Before Oocyte Insemination.” CRISPR J 4, no. 1 (2021): 132–46. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, B.R., C.A. Makarewich, and D.M. Anderson. “A Peptide Encoded by a Transcript Annotated as Long Noncoding RNA Enhances SERCA Activity in Muscle.” Science 351, no. 6270 (2016): 271–75. [CrossRef]

- Neu, Carolin T., Linus Weilepp, Kaya Bork, Astrid Gesper, and Rüdiger Horstkorte. "GNE deficiency impairs Myogenesis in C2C12 cells and cannot be rescued by ManNAc supplementation." Glycobiology 34, no. 3 (2024): cwae004. [CrossRef]

- Nigro, G., L.I. Comi, L. Politano, and R.J. Bain. “The Incidence and Evolution of Cardiomyopathy in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy.” Int. J. Cardiol 26 (1990): 271–77. [CrossRef]

- Noguchi, S., Y. Keira, and K. Murayama. “Reduction of UDP-N-Acetylglucosamine 2-Epimerase/N-Acetylmannosamine Kinase Activity and Sialylation in Distal Myopathy with Rimmed Vacuoles.” J Biol Chem 279, no. 12 (2004): 11402–7. [CrossRef]

- Ousterout, D.G., A.M. Kabadi, P.I. Thakore, W.H. Majoros, T.E. Reddy, and C.A. Gersbach. “Multiplex CRISPR/Cas9-Based Genome Editing for Correction of Dystrophin Mutations That Cause Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy.” Nat. Commun 6 (2015): 6244. [CrossRef]

- Panda, G., and A. Ray. “Comparative Structural and Dynamics Study of Free and gRNA-Bound FnCas9 and SpCas9 Proteins.” Comput Struct Biotechnol J 20 (2022): 4172–84. [CrossRef]

- Panicucci, Chiara, Lizzia Raffaghello, Santina Bruzzone, Serena Baratto, Elisa Principi, Carlo Minetti, Elisabetta Gazzerro, and Claudio Bruno. "eATP/P2X7R axis: an orchestrated pathway triggering inflammasome activation in muscle diseases." International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21, no. 17 (2020): 5963. [CrossRef]

- Papiha, S.S. “Genetic Variation in India.” Human Biology, 1996, 607–28.

- Park, Y.E., J. Choi, L. Kim, E. Park, H. Go, and J. Shin. “A Pilot Trial for Efficacy Confirmation of 6’-Sialyllactose Supplementation in GNE Myopathy: Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial.” Mol Genet Metab 144, no. 1 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Patel, Alpesh, Shaishav Shah, Shiva Shankaran Chettiar, Devendrasinh Jhala, Siddharth Shah, and Alpesh Patel. “A Novel Founder Mutation in the SGCB Gene (Exon 5) Causes Limb Girdle Muscular Dystrophy (LGMDR4.” In Sathwara Community. Gujarat, India, n.d. [CrossRef]

- Pertusati, F., and J. Morewood. “Synthesis of 2-Acetamido-1,3,4-Tri-o-Acetyl-2-Deoxy-d-Mannopyranose −6-Phosphate Prodrugs as Potential Therapeutic Agents.” Curr Protoc 2022, no. 2 (n.d.). [CrossRef]

- Piccolo, F., Marc Jeanpierre, F. Leturcq, C. Dode, K. Azibi, A. Toutain, L. Merlini et al. "A founder mutation in the γ-sarcoglycan gene of Gypsies possibly predating their migration out of India." Human molecular genetics 5, no. 12 (1996): 2019-2022. [CrossRef]

- Polavarapu, Kiran, Aradhna Mathur, Aditi Joshi, Saraswati Nashi, Veeramani Preethish-Kumar, Mainak Bardhan, and Pooja Sharma. “A Founder Mutation in the GMPPB Gene [c. 1000G> A (p. Asp334Asn)] Causes a Mild Form of Limb-Girdle Muscular Dystrophy/Congenital Myasthenic Syndrome (LGMD/CMS) in South Indian Patients.” Neurogenetics 22 (2021): 271–85. [CrossRef]

- Polavarapu, Kiran, Veeramani Preethish-Kumar, Deepha Sekar, Seena Vengalil, Saraswati Nashi, Niranjan P. Mahajan, and Priya Treesa Thomas. “Mutation Pattern in 606 Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Children with a Comparison between Familial and Non-Familial Forms: A Study in an Indian Large Single-Center Cohort.” Journal of Neurology 266 (2019): 2177–85. [CrossRef]

- Prieto, Sergio, and Josep M. Grau. “The geoepidemiology of autoimmune muscle disease.” Autoimmunity reviews 9, no. 5 (2010): 330–34. [CrossRef]

- Quattrocelli, Mattia, Aaron S. Zelikovich, Isabella M. Salamone, Julie A. Fischer, and Elizabeth M. McNally. "Mechanisms and clinical applications of glucocorticoid steroids in muscular dystrophy." Journal of neuromuscular diseases 8, no. 1 (2021): 39-52. [CrossRef]

- Quattrocelli, Mattia, Isabella M. Salamone, Patrick G. Page, James L. Warner, Alexis R. Demonbreun, and Elizabeth M. McNally. "Intermittent glucocorticoid dosing improves muscle repair and function in mice with limb-girdle muscular dystrophy." The American Journal of Pathology 187, no. 11 (2017): 2520-2535. [CrossRef]

- R, Bou Akar, Lama C, and Aubin D. “Generation of Highly Pure Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Myogenic Progenitor Cells and Myotubes.” Stem Cell Reports 19, no. 1 (2024): 84–99. [CrossRef]

- Raben, N., A. Wong, E. Ralston, and R. Myerowitz. “Autophagy and Mitochondria in Pompe Disease: Nothing Is so New as What Has Long Been Forgotten.” Am J Med Genet Part C, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Raffaghello, Lizzia, Elisa Principi, Serena Baratto, Chiara Panicucci, Sara Pintus, Francesca Antonini, Genny Del Zotto et al. "P2X7 receptor antagonist reduces fibrosis and inflammation in a mouse model of alpha-sarcoglycan muscular dystrophy." Pharmaceuticals 15, no. 1 (2022): 89. [CrossRef]

- Reelfs, Anna M., Carrie M. Stephan, Shelley R.H. Mockler, Katie M. Laubscher, M.Bridget Zimmerman, and Katherine D. Mathews. “Pain Interference and Fatigue in Limb-Girdle Muscular Dystrophy R9.” Neuromuscular Disorders 33, no. 6 (2023): 523–30. [CrossRef]

- Russell, Alan J., Mike DuVall, Ben Barthel, Ying Qian, Angela K. Peter, Breanne L. Newell-Stamper, Kevin Hunt et al. "Modulating fast skeletal muscle contraction protects skeletal muscle in animal models of Duchenne muscular dystrophy." The Journal of clinical investigation 133, no. 10 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Saad, F.A., J.F. Saad, G. Siciliano, L. Merlini, and C. Angelini. “Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Gene Therapy.” Curr. Gene Ther, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Sahasrabudhe, S.A., M.R. Terluk, and R.V. Kartha. “N-Acetylcysteine Pharmacology and Applications in Rare Diseases-Repurposing an Old Antioxidant.” Antioxidants (Basel Jun 21;12(7):1316 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Sahenk, Z., B. Ozes, and D. Murrey. “Systemic Delivery of AAVrh74.tMCK.hCAPN3 Rescues the Phenotype in a Mouse Model for LGMD2A/R1.” Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 22 (2021): 401–14. [CrossRef]

- Şahin, İzem Olcay, Yusuf Özkul, and Munis Dündar. "Current and future therapeutic strategies for limb girdle muscular dystrophy type R1: Clinical and experimental approaches." Pathophysiology 28, no. 2 (2021): 238-249. [CrossRef]

- Salama, Ilan, Stephan Hinderlich, Zipora Shlomai, Iris Eisenberg, Sabine Krause, Kevin Yarema, Zohar Argov et al. "No overall hyposialylation in hereditary inclusion body myopathy myoblasts carrying the homozygous M712T GNE mutation." Biochemical and biophysical research communications 328, no. 1 (2005): 221-226. [CrossRef]

- Salih, Mustafa A.M., and Peter B. Kang. “Hereditary and Acquired Myopathies.” Clinical Child Neurology, 2020, 1281–1349.

- Samarasiri, Udari. “Limb-girdle muscular dystrophies: An update,” 2023. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, J.S., M. Shanmugam, and J.P. Gonzalez. “Increased Sarcolipin Expression and Decreased Sarco(Endo)Plasmic Reticulum Ca2+ Uptake in Skeletal Muscles of Mouse Models of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy.” J Muscle Res Cell Motil 34, no. 5–6 (2013): 349–56. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S., P. Chanana, R. Bharadwaj, S. Bhattacharya, and R. Arya. “Functional Characterization of GNE Mutations Prevalent in Asian Subjects with GNE Myopathy, an Ultra-Rare Neuromuscular Disorder.” Biochimie 199 (2022): 36–45. [CrossRef]

- Sheth, Jayesh, Aadhira Nair, Frenny Sheth, Manali Ajagekar, Tejasvi Dhondekar, Inusha Panigrahi, and Ashish Bavdekar. “Burden of Rare Genetic Disorders in India: Twenty-Two Years’ Experience of a Tertiary Centre.” Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 19, no. 1 (2024): 295. [CrossRef]

- Siciliano, Gabriele, Costanza Simoncini, Stefano Giannotti, Virna Zampa, Corrado Angelini, and Giulia Ricci. "Muscle exercise in limb girdle muscular dystrophies: pitfall and advantages." Acta Myologica 34, no. 1 (2015): 3.

- Siemionow, M., J. Cwykiel, A. Heydemann, J. Garcia-Martinez, K. Siemionow, and E. Szilagyi. “Creation of Dystrophin Expressing Chimeric Cells of Myoblast Origin as a Novel Stem Cell Based Therapy for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy.” Stem Cell Rev Rep 14 (2018): 189–99. [CrossRef]

- Siemionow, M., K. Budzynska, and K. Zalants. “Amelioration of Morphological Pathology in Cardiac, Respiratory, and Skeletal Muscles Following Intraosseous Administration of Human Dystrophin Expressing Chimeric (DEC) Cells in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Model.” Biomedicines 12, no. 3 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Siemionow, M., P. Langa, and S. Brodowska. “Long-Term Protective Effect of Human Dystrophin Expressing Chimeric (DEC.” Cell Therapy on Amelioration of Function of Cardiac, Respiratory and Skeletal Muscles in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy [Published Correction Appears in Stem Cell Rev Rep Feb;19(2):582-583 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Singh, Reema, and Ranjana Arya. "GNE myopathy and cell apoptosis: a comparative mutation analysis." Molecular neurobiology 53, no. 5 (2016): 3088-3101. [CrossRef]

- Sparks, Susan, Goran Rakocevic, Galen Joe, Irini Manoli, Joseph Shrader, Michael Harris-Love, Barbara Sonies et al. "Intravenous immune globulin in hereditary inclusion body myopathy: a pilot study." BMC neurology 7, no. 1 (2007): 3. [CrossRef]

- Speciale, Alfina A., Ruth Ellerington, Thomas Goedert, and Carlo Rinaldi. "Modelling neuromuscular diseases in the age of precision medicine." Journal of personalized medicine 10, no. 4 (2020): 178. [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, M., and C.Circadian Clock Walker. “Glucocorticoids and NF-κB Signaling in Neuroinflammation- Implicating Glucocorticoid Induced Leucine Zipper as a Molecular Link.” ASN Neuro 14 (2022): 175909142211201.

- Srivastava, A., E.W. Lusby, and K.I. Berns. “Nucleotide Sequence and Organization of the Adeno-Associated Virus 2 Genome.” J. Virol 45 (1983): 555–64. [CrossRef]

- Stadelmann, C., S. Francescantonio, A. Marg, S. Müthel, S. Spuler, and H. Escobar. “mRNA-Mediated Delivery of Gene Editing Tools to Human Primary Muscle Stem Cells.” Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 28 (2022): 47–57. [CrossRef]

- Sun, C., L. Shen, Z. Zhang, and X. Xie. “Therapeutic Strategies for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: An Update.” Genes (Basel 11, no. 8 (2020): 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Suthar, R., S. Kesavan, I.K. Sharawat, M. Malviya, T. Sirari, B.K. Sihag, A.G. Saini, V. Jyothi, and N. Sankhyan. “The Expanding Spectrum of Dystrophinopathies: HyperCKemia to Manifest Female Carriers.” J. Pediatr. Neurosci 16 (2021): 206–11. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, N., M. Mori-Yoshimura, and M. Katsuno. “Phase II/III Study of Aceneuramic Acid Administration for GNE Myopathy in Japan.” J Neuromuscul Dis 10, no. 4 (2023): 555–66. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Naoki, Madoka Mori-Yoshimura, Masahisa Katsuno, Masanori P. Takahashi, Satoshi Yamashita, Yasushi Oya, Atsushi Hashizume, et al. “Safety and Efficacy of Aceneuramic Acid in GNE Myopathy: Open-Label Extension Study.” Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Naoki, Masaaki Kato, Hitoshi Warita, Rumiko Izumi, Maki Tateyama, Hiroshi Kuroda, Ryuta Asada et al. "Phase I clinical trial results of aceneuramic acid for GNE myopathy in Japan." Translational Medicine Communications 3, no. 1 (2018): 7. [CrossRef]

- Sveen, Marie-Louise, Søren P. Andersen, Lina H. Ingelsrud, Sarah Blichter, Niels E. Olsen, Simon Jønck, Thomas O. Krag, and John Vissing. “Resistance Training in Patients with Limb-girdle and Becker Muscular Dystrophies.” Muscle & Nerve 47, no. 2 (2013): 163–69. [CrossRef]

- Swiderski, Kristy, and Gordon S. Lynch. "Translational progress in the development of pharmacotherapies for Duchenne muscular dystrophy." Regenerative Medicine 20, no. 10 (2025): 489-500. [CrossRef]

- Syed, Y.Y. “Eteplirsen: first global approval.” Drugs 76 (2016): 1699–1704. [CrossRef]

- Tanihara, F., M. Hirata, N.T. Nguyen, Q.A. Le, M. Wittayarat, M. Fahrudin, and T. Otoi. “Generation of CD163-edited pig via electroporation of the CRISPR/Cas9 system into porcine in vitro-fertilized zygotes.” Animal Biotechnology 32, no. 2 (2019): 147–54. [CrossRef]

- Tasfaout, H., C.L. Halbert, and T.S. McMillen. “Split Intein-Mediated Protein Trans-Splicing to Express Large Dystrophins.” Nature 632, no. 8023 (2024): 192–200. [CrossRef]

- Tasfaout, H., C.L. Halbert, and T.S. McMillen. “Split Intein-Mediated Protein Trans-Splicing to Express Large Dystrophins.” Nature 632, no. 8023 (2024): 192–200. [CrossRef]

- Tidball, James G., Steven S. Welc, and Michelle Wehling-Henricks. “Immunobiology of Inherited Muscular Dystrophies.” Comprehensive Physiology 8, no. 4 (2018): 1313–56.

- Tominari, T., and Y. Aoki. “Clinical Development of Novel Therapies for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy—Current and Future Neurology and Clinical Neuroscience,” 2023.

- Turken, Askeri, Maria Luckas, Vatan Kavak, Ömer Satıcı, and Dildan Kavak. “The effects of home exercise program on limb-girdle disease: a cohort study.” Folia Neuropathologica 60, no. 1 (2022): 48–59. [CrossRef]

- Tycko, J., V.E. Myer, and P.D. Hsu. “Methods for Optimizing CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing Specificity.” Molecular Cell 63, no. 3 (2016): 355–70. [CrossRef]

- Urtizberea, J. Andoni, and France Leturcq. "Limb girdle muscular dystrophies: The clinicopathological viewpoint." Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology 10, no. 4 (2007): 214-224. [CrossRef]

- V., Derbyshire, and Belfort M. “Lightning Strikes Twice: Intron–Intein Coincidence.” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95 (1998): 1356–57. [CrossRef]

- V., Mariot, Joubert R., Hourdé C., Féasson L., Hanna M., Muntoni F., Maisonobe T., Servais L., Bogni C., and Le Panse R. “Downregulation of Myostatin Pathway in Neuromuscular Diseases May Explain Challenges of Anti-Myostatin Therapeutic Approaches.” Nat. Commun 8 (2017): 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Veerapandiyan, Aravindhan. "Early Insights on 3 Patients With DMD From Trial Assessing Gene Therapy RGX-202: Aravindhan Veerapandiyan, MD." Neurology Live (2023): NA-NA.

- Verhaart, I.E., R.J. Duijn, B. Adel, A.A. Roest, J.J. Verschuuren, A. Aartsma-Rus, and L. Weerd. “Assessment of Cardiac Function in Three mouseDystrophinopathies by Magnetic Resonance Imaging.” Neuromuscul. Disord 22 (2012): 418–26. [CrossRef]

- Verhaart, I.E., R.J. Duijn, B. Adel, A.A. Roest, J.J. Verschuuren, A. Aartsma-Rus, and L. Weerd. “Assessment of Cardiac Function in Three mouseDystrophinopathies by Magnetic Resonance Imaging.” Neuromuscul. Disord 22 (2012): 418–26. [CrossRef]

- Viviano, K.R.Glucocorticoids, and Azathioprine Cyclosporine. “Chlorambucil, and Mycophenolate in Dogs and Cats: Clinical Uses, Pharmacology, and Side Effects.” Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract 52 (2022): 797–817.

- Vrist, Louise T.H., Lone F. Knudsen, and Charlotte Handberg. “‘It Becomes the New Everyday Life’–Experiences of Chronic Pain in Everyday Life of People with Limb-Girdle Muscular Dystrophy.” Disability and Rehabilitation 45, no. 23 (2023): 3875–82.

- Wang, J., Y. Zhang, C.A. Mendonca, O. Yukselen, K. Muneeruddin, L. Ren, J. Liang, et al. “AAV-delivered suppressor tRNA overcomes a nonsense mutation in mice.” Nature 604, no. 7905 (2022): 343–48. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., C. Tokheim, and S.S. Gu. “In Vivo CRISPR Screens Identify the E3 Ligase Cop1 as a Modulator of Macrophage Infiltration and Cancer Immunotherapy Target.” Cell 184, no. 21 (2021): 5357–74. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Zhonglei, Xin Sun, Mingyu Sun, Chao Wang, and Liyan Yang. "Game Changers: Blockbuster Small-Molecule Drugs Approved by the FDA in 2024." Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 5 (2025): 729. [CrossRef]

- Wasala, L.P. “The Implication of Hinge 1 and Hinge 4 in Microdystrophin Gene Therapy for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy.” Hum. Gene Ther 34 (2023): 459–70. [CrossRef]

- Wei, T., Y. Sun, and Q. Cheng. “Lung SORT LNPs Enable Precise Homology-Directed Repair Mediated CRISPR/Cas Genome Correction in Cystic Fibrosis Models.” Nat Commun 14, no. 1 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Weinmann, J. “Identification of a Myotropic AAV by Massively Parallel in Vivo Evaluation of Barcoded Capsid Variants.” Nat. Commun 11 (2020): 5432. [CrossRef]

- Wicklund, M.P. “Limb-Girdle Muscular Dystrophies.” In Encyclopedia of the Neurological Sciences, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Willis, Alexander B., Aaron S. Zelikovich, Robert Sufit, Senda Ajroud-Driss, Krista Vandenborne, Alexis R. Demonbreun, Abhinandan Batra, Glenn A. Walter, and Elizabeth M. McNally. "Serum protein and imaging biomarkers after intermittent steroid treatment in muscular dystrophy." Scientific reports 14, no. 1 (2024): 28745. [CrossRef]

- Xiao-Jie, Lu, Xue Hui-Ying, Ke Zun-Ping, Chen Jin-Lian, and Ji Li-Juan. “CRISPR-Cas9: A New and Promising Player in Gene Therapy.” Journal of Medical Genetics 52, no. 5 (2015): 289–96. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X., A.Q. Wang, and L.L. Latham. “Safety, Pharmacokinetics and Sialic Acid Production after Oral Administration of N-Acetylmannosamine (ManNAc) to Subjects with GNE Myopathy.” Mol Genet Metab 122, no. 1–2 (2017): 126–34. [CrossRef]

- Yiu, Eppie M., and Andrew J. Kornberg. “Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy.” Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health 51, no. 8 (2015): 759–64.

- Yonekawa, T., M.C. Malicdan, and A. Cho. “Sialyllactose ameliorates myopathic phenotypes in symptomatic GNE myopathy model mice.” Brain 137, no. Pt 10 (2014): 2670–79. [CrossRef]

- Zabłocki, Krzysztof, and Dariusz C. Górecki. "The role of P2X7 purinoceptors in the pathogenesis and treatment of muscular dystrophies." International Journal of Molecular Sciences 24, no. 11 (2023): 9434. [CrossRef]

- Zelikovich, A.S., B.C. Joslin, P. Casey, E.M. McNally, and S. Ajroud-Driss. “An Open Label Exploratory Clinical Trial Evaluating Safety and Tolerability of Once-Weekly Prednisone in Becker and Limb-Girdle Muscular Dystrophy.” J Neuromuscul Dis 9, no. 2 (2022): 275–87. [CrossRef]

- Zelikovich, Aaron S., Benjamin C. Joslin, Patricia Casey, Elizabeth M. McNally, and Senda Ajroud-Driss. "An open label exploratory clinical trial evaluating safety and tolerability of once-weekly prednisone in becker and limb-girdle muscular dystrophy." Journal of neuromuscular diseases 9, no. 2 (2022): 275-287. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. “Genetic Analysis of 62 Chinese Families with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy and Strategies of Prenatal Diagnosis in a Single Center.” BMC Med. Genet, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S. “Genotype Characterization and Delayed Loss of Ambulation by Glucocorticoids in a Large Cohort of Patients with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy.” Orphanet. J. Rare Dis, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Yu, Takahiko Nishiyama, Eric N. Olson, and Rhonda Bassel-Duby. “CRISPR/Cas Correction of Muscular Dystrophies.” Experimental Cell Research 408, no. 1 (2021): 112844. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y., C. Zhang, and W. Xiao. “Systemic Delivery of Full-Length Dystrophin in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Mice.” Nat Commun 15 (2024): 6141. [CrossRef]

- Zídková, Jana, Tereza Kramářová, Johana Kopčilová, Kamila Réblová, Jana Haberlová, Radim Mazanec, Stanislav Voháňka et al. "Genetic findings in Czech patients with limb girdle muscular dystrophy." Clinical Genetics 104, no. 5 (2023): 542-553. [CrossRef]

- Zygmunt, D.A., P. Lam, and A. Ashbrook. “Development of Assays to Measure GNE Gene Potency and Gene Replacement in Skeletal Muscle.” J Neuromuscul Dis 10, no. 5 (2023): 797–812. [CrossRef]

| Mutation | Mutation Type | Gene | LGMD type | Community | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c.1000G > A | Missense | GMPPB (GDP-mannose pyrophosphorylase B) | LGMDR23 | South Indian | Polavarapu et al., 2021 [32] |

| intron 18/exon 19 c.2051-1G>T | Missense | CAPN3 | LGMD2A/R1 | Agarwal Community | Khadilkar et al., 2016 [125] |

| exon 22 c.2338G>C | Missense | CAPN3 | LGMD2A/R1 | Agarwal Community | Khadilkar et al., 2016 [125] |

| c.2051–1G > T and c.2338G > C in 9.7%, c.1343G > A, c.802–9G > A, and c.1319G > A | Missense | CAPN3 | LGMD2A/R1 | South Indian | Ganaraja et al., 2022 [127] |

| Chr 4:52894204C>T; | Missense | SGCB | LGMD2E/R4 | Sathwara | Patel et al., 2024 [132] |

| EMD c.654_658dup*, | duplication | LMNA | LGMD1B | Not mentioned | Baskar et al., 2024 [133] |

| c.847G>A | Missense | SGCG | LGMD2C/R5 | Gypsies (Indian origin community) | Piccolo et al., 1996 [134] |

| SGCB c.544A>C | Missense | SGCB | LGMD2E/R4 | 11 different states in India and 1 individual from Bangladesh | Bardhan et al., 2022 [135] |

| Not available | NA | CAPN3 | LGMDR1/2A | Mumbai | Khadilkar et al., 2022 [136] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).