Submitted:

12 December 2025

Posted:

15 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Literature Search Strategy and Scope of the Review

3. Integrated Framework for Network-Level DBS Mechanisms and Clinical Translation

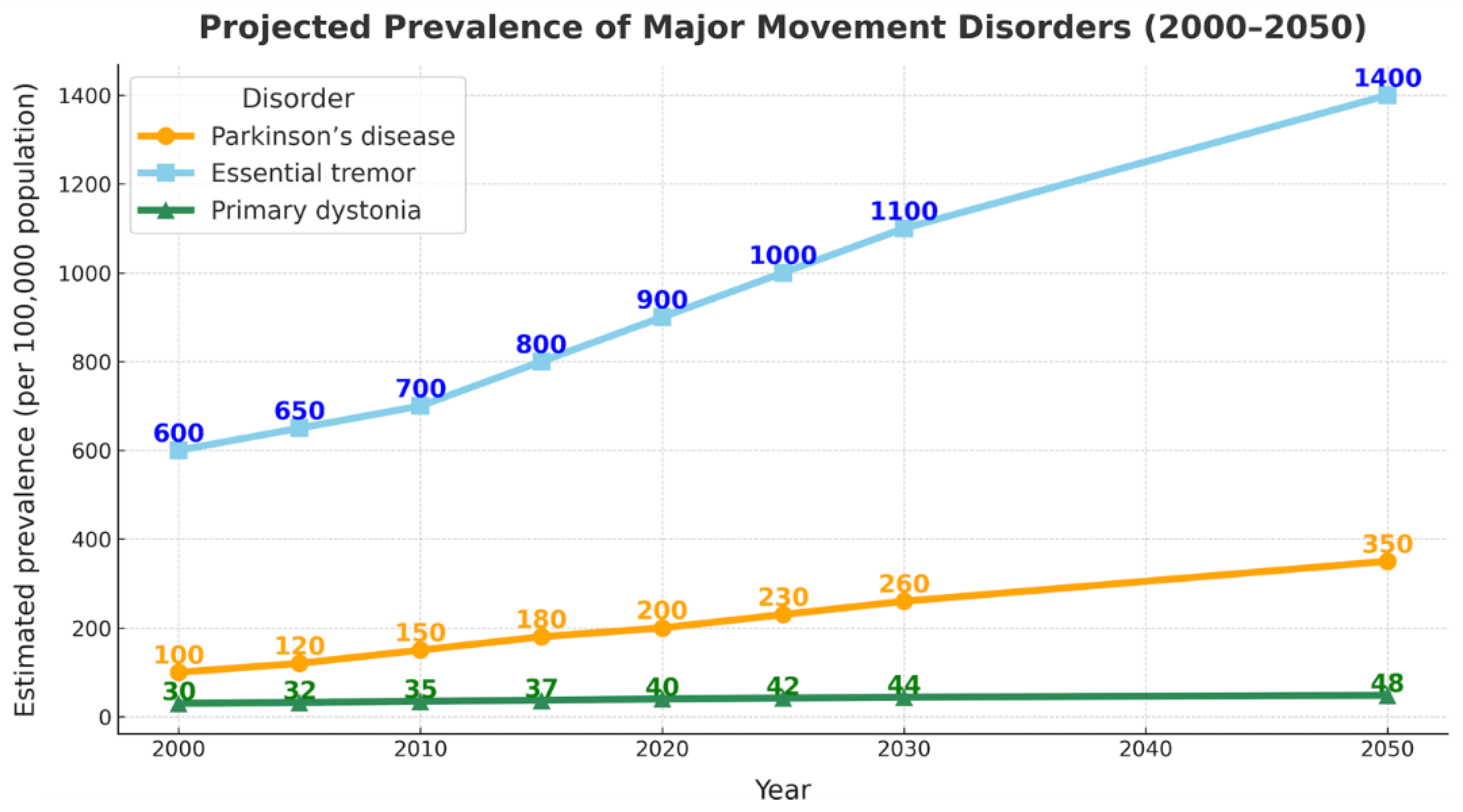

3.1. Epidemiology and Global Burden of Movement Disorders

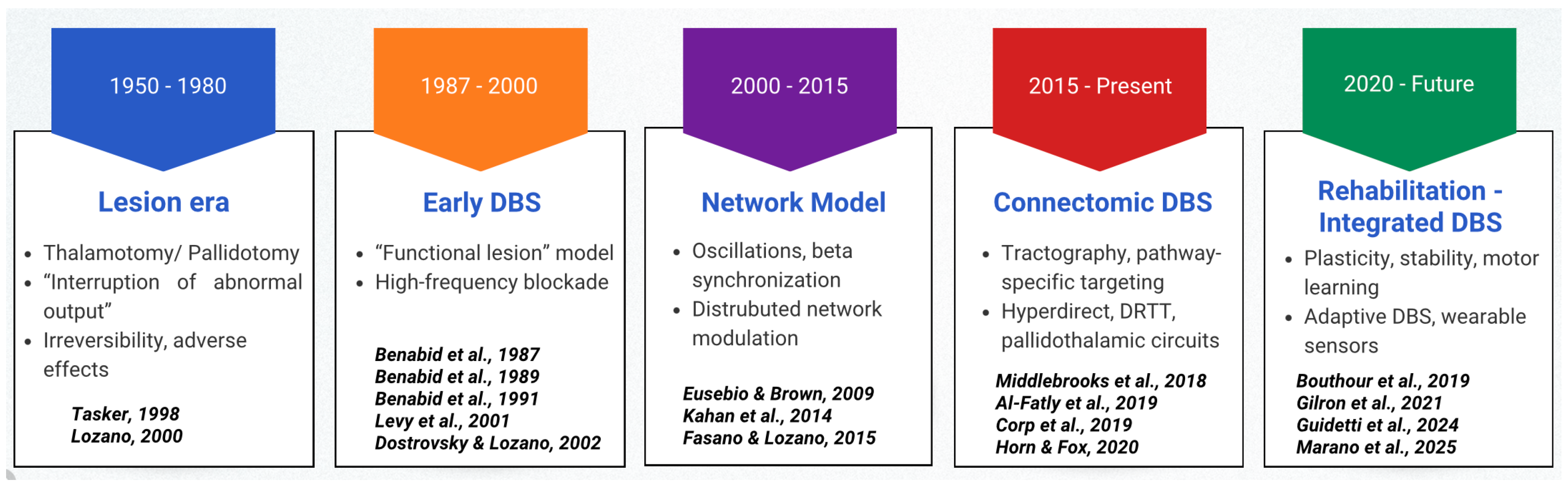

3.2. Historical Evolution of DBS Concepts

3.2.1. From Lesion-Based Surgery to Reversible Neuromodulation

3.2.2. Nucleus-Centric DBS and Emerging Complexity

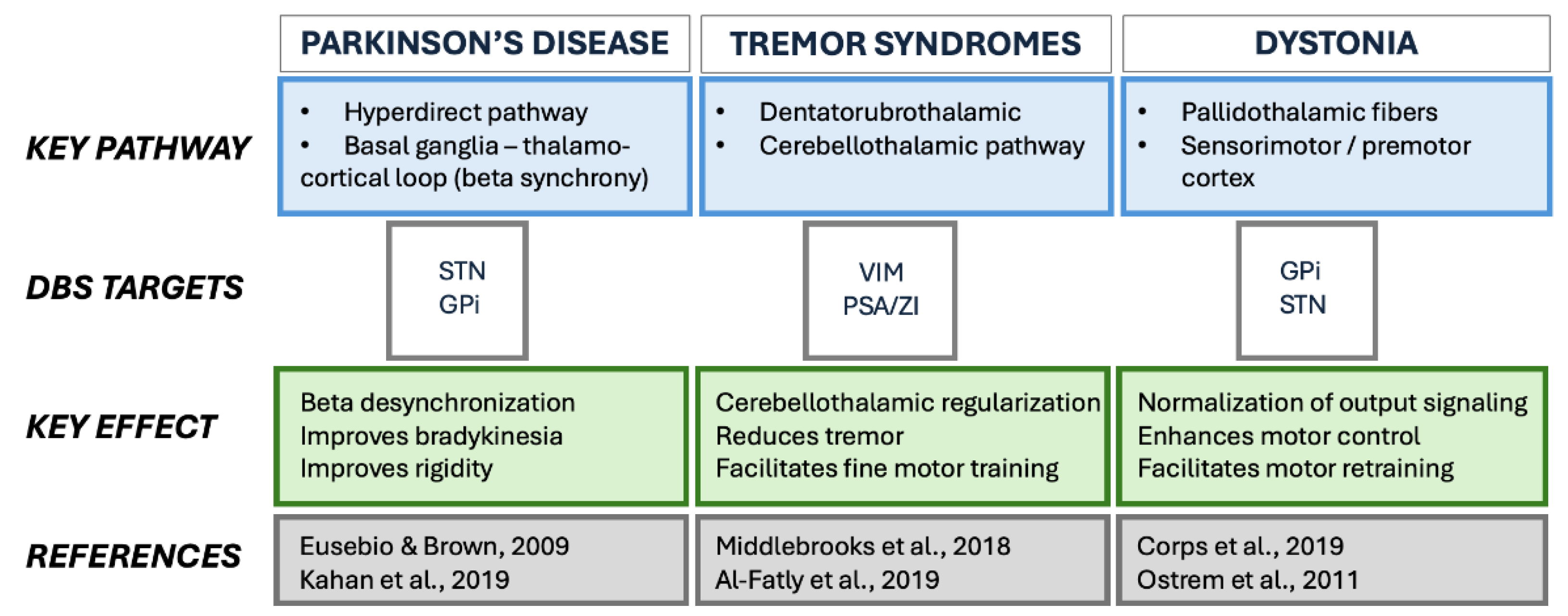

3.3. Phenotypes and Network Level Heterogeneity

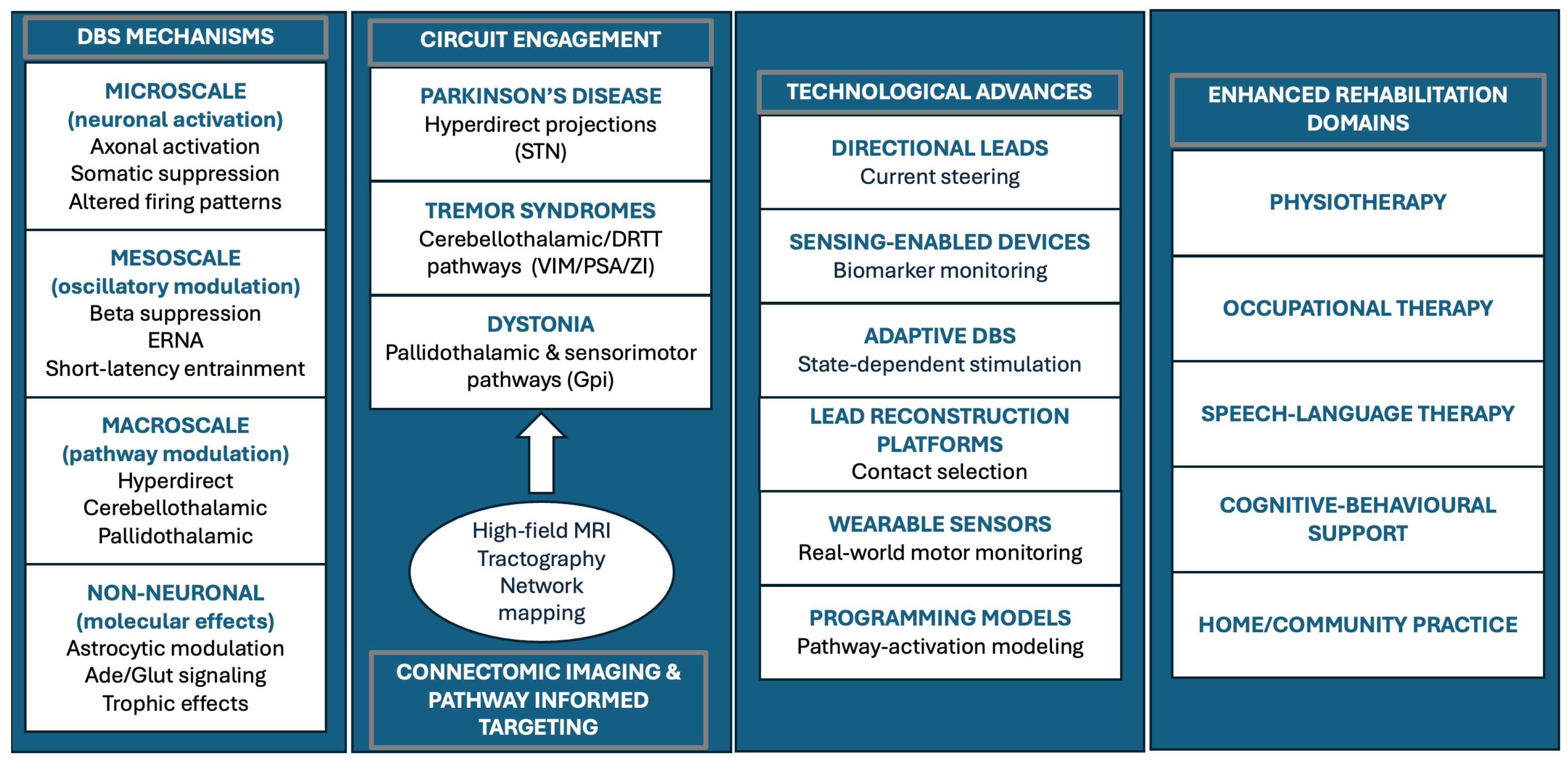

3.4. Local Effects and Multiscale Biological Mechanisms

3.5. Imaging Evidence for Network-Level Mechanisms

3.6. Surgical and Technological Advances Enabling Precision DBS

| Domain | Main goals |

|---|---|

| Physiotherapy | Improve gait, balance, amplitude, and dual-task performance |

| Occupational therapy | Enhance dexterity, handwriting, and ADLs |

| Speech–language therapy | Improve articulation, phonation, and intelligibility |

| Cognitive–behavioral support | Maintain executive functioning, mood, and therapy engagement |

| Home / community training | Promote task-specific practice and generalization to daily life |

3.7. Rehabilitation-Integrated DBS: Towards Network Restoration

4. Limitations

5. Future Directions

6. Conclusions

7. Key highlights

- Deep brain stimulation (DBS) enhances the stability of motor performance, creating favorable conditions for structured rehabilitation.

- Connectivity-informed targeting improves clinical outcomes by aligning stimulation with patient-specific circuit architecture.

- Technological advances—including tractography-based planning, directional leads, and sensing-enabled systems—support more precise and individualized neuromodulation.

- Rehabilitation integrated with DBS can amplify functional gains by leveraging stabilized neural dynamics.

- Future frameworks will incorporate adaptive stimulation, biomarker-guided therapy, and real-world motor monitoring to optimize long-term functional restoration.

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DBS | Deep brain stimulation |

| DRTT | Dentato–rubro–thalamic tract |

| ET | Essential tremor |

| ERNA | Evoked resonant neural activity |

| fMRI | Functional magnetic resonance imaging |

| GA1 | Glutaric aciduria type I |

| GPi | Globus pallidus internus |

| KMT2B | Lysine methyltransferase 2B |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| PET | Positron emission tomography |

| PIGD | Postural instability/gait disorder |

| PSA | Posterior subthalamic area |

| SPECT | Single-photon emission computed tomography |

| STN | Subthalamic nucleus |

| VIM | Ventral intermediate nucleus |

| ZI | Zona incerta |

References

- Louis, E.D.; Ferreira, J.J. How common is the most common adult movement disorder? Update on the worldwide prevalence of essential tremor. Mov. Disord. 2010, 25, 534–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorsey, E.R.; Sherer, T.; Okun, M.S.; Bloem, B.R. The Emerging Evidence of the Parkinson Pandemic. J. Park. Dis. 2018, 8, S3–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steeves, T.D.; Day, L.; Dykeman, J.; Jette, N.; Pringsheim, T. The prevalence of primary dystonia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mov. Disord. 2012, 27, 1789–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albanese, A.; Bhatia, K.; Bressman, S.B.; DeLong, M.R.; Fahn, S.; Fung, V.S.; Hallett, M.; Jankovic, J.; Jinnah, H.A.; Klein, C.; et al. Phenomenology and classification of dystonia: A consensus update. Mov. Disord. 2013, 28, 863–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowal, S.L.; Dall, T.M.; Chakrabarti, R.; Storm, M.V.; Jain, A. The current and projected economic burden of Parkinson's disease in the United States. Mov. Disord. 2013, 28, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.-C.; Dong, Y.-Y.; Ying, Y.-C.; Chen, G.-Y.; Fan, Q.; Yin, P.; Chen, Y.-L. The burden of Parkinson’s disease, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease study 2021. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2025, 17, 1596392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Lv, Z.; Dai, Y.; Yu, L.; Zhang, L.; Wang, K.; Hu, P. The global, regional, and National burden of parkinson’s disease in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. BMC Public Heal. 2025, 25, 3047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benabid, A.; Pollak, P.; Louveau, A.; Henry, S.; de Rougemont, J. Combined (Thalamotomy and Stimulation) Stereotactic Surgery of the VIM Thalamic Nucleus for Bilateral Parkinson Disease. Ster. Funct. Neurosurg. 1987, 50, 344–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benabid, A.L.; Pollak, P.; Hommel, M.; Gaio, J.M.; De Rougemont, J.; Perret, J. Treatment of Parkinson tremor by chronic stimulation of the ventral intermediate nucleus of the thalamus. Rev Neurol (Paris). 1989, 145, 320–3. [Google Scholar]

- Tasker, R.R. Deep brain stimulation is preferable to thalamotomy for tremor suppression. Surg. Neurol. 1998, 49, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, A.M. Vim Thalamic Stimulation for Tremor. Arch. Med Res. 2000, 31, 266–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dostrovsky, J.O.; Lozano, A.M. Mechanisms of deep brain stimulation. Mov. Disord. 2002, 17, S63–S68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R., L.; A., L.; W., H.; A., L.; J., D. Simultaneous repetitive movements following pallidotomy or subthalamic deep brain stimulation in patients with Parkinson's disease. Exp. Brain Res. 2002, 147, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aum, D.J.; Tierney, T.S. Deep brain stimulation foundations and future trends. Front. Biosci. 2018, 23, 162–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horn, A.; Neumann, W.; Degen, K.; Schneider, G.; Kühn, A.A. Toward an electrophysiological “sweet spot” for deep brain stimulation in the subthalamic nucleus. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2017, 38, 3377–3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Fatly, B.; Ewert, S.; Kübler, D.; Kroneberg, D.; Horn, A.; A Kühn, A. Connectivity profile of thalamic deep brain stimulation to effectively treat essential tremor. Brain 2019, 142, 3086–3098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, A.; Fox, M.D. Opportunities of connectomic neuromodulation. NeuroImage 2020, 221, 117180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middlebrooks, E.H.; Tuna, I.S.; Almeida, L.; Grewal, S.S.; Wong, J.; Heckman, M.G.; Lesser, E.R.; Bredel, M.; Foote, K.D.; Okun, M.S.; et al. Structural connectivity–based segmentation of the thalamus and prediction of tremor improvement following thalamic deep brain stimulation of the ventral intermediate nucleus. NeuroImage: Clin. 2018, 20, 1266–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corp, D.T.; Joutsa, J.; Darby, R.R.; Delnooz, C.C.S.; van de Warrenburg, B.P.C.; Cooke, D.; Prudente, C.N.; Ren, J.; Reich, M.M.; Batla, A.; et al. Network localization of cervical dystonia based on causal brain lesions. Brain 2019, 142, 1660–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollunder, B.; Ostrem, J.L.; Sahin, I.A.; Rajamani, N.; Oxenford, S.; Butenko, K.; Neudorfer, C.; Reinhardt, P.; Zvarova, P.; Polosan, M.; et al. Mapping dysfunctional circuits in the frontal cortex using deep brain stimulation. Nat. Neurosci. 2024, 27, 573–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, A.; Al-Fatly, B.; Neumann, W.-J.; Neudorfer, C. Connectomic DBS: An introduction. In Connectomic Deep Brain Stimulation; Elsevier, 2022; pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilic, U.; Smets, C.; Deng, Z.; Boogers, A.; Mc Laughlin, M.; De Vloo, P.; George, D.D.; Nuttin, B. A Narrative Review on the Current Landscape of Invasive Neuromodulation for Poststroke Motor Recovery: Mechanisms, Challenges, and Future Directions. Neuromodulation Technol. Neural Interface 2025, 28, 1093–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middlebrooks, E.H.; Okromelidze, L.; E Carter, R.; Jain, A.; Lin, C.; Westerhold, E.; Peña, A.B.; Quiñones-Hinojosa, A.; Uitti, R.J.; Grewal, S.S. Directed stimulation of the dentato-rubro-thalamic tract for deep brain stimulation in essential tremor: a blinded clinical trial. Neuroradiol. J. 2021, 35, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chacón, A.; Mateo-Sierra, O.; Pérez-Sánchez, J.R.; De la Casa-Fages, B.; Grandas, F.; De Castro, P.; Miranda, C. Long-Term Outcomes of GPi Deep Brain Stimulation in a Child with Glutaric Aciduria Type 1 (GA1). Mov. Disord. Clin. Pr. 2024, 11, 1311–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzo, E.L.; De la Casa-Fages, B.; Sánchez, M.G.; Sánchez, J.P.; Carballal, C.F.; Vidorreta, J.G.; Sierra, O.M.; Chicote, A.C.; Grandas, F. Pallidal deep brain stimulation response in two siblings with atypical adult-onset dystonia related to a KMT2B variant. J. Neurol. Sci. 2022, 438, 120295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbasi, M.E.; Nambiar, S.; Reed, S.; Hennegan, K.; Hadker, N.; Eldar-Lissai, A.; Cosentino, S. Essential tremor patients experience significant burden beyond tremor: A systematic literature review. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 891446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olesen, J.; Gustavsson, A.; Svensson, M.; Wittchen, H.-U.; Jönsson, B. The economic cost of brain disorders in Europe. Eur. J. Neurol. 2012, 19, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benabid, A.; Pollak, P.; Hoffmann, D.; Gervason, C.; Hommel, M.; Perret, J.; de Rougemont, J.; Gao, D. Long-term suppression of tremor by chronic stimulation of the ventral intermediate thalamic nucleus. Lancet 1991, 337, 403–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limousin, P.; Martinez-Torres, I. Deep Brain Stimulation for Parkinson’s Disease. Neurotherapeutics 2008, 5, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupsch, A.; Benecke, R.; Müller, J.; Trottenberg, T.; Schneider, G.-H.; Poewe, W.; Eisner, W.; Wolters, A.; Müller, J.-U.; Deuschl, G.; et al. Pallidal Deep-Brain Stimulation in Primary Generalized or Segmental Dystonia. New Engl. J. Med. 2006, 355, 1978–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volkmann, J.; Wolters, A.; Kupsch, A.; Müller, J.; A Kühn, A.; Schneider, G.-H.; Poewe, W.; Hering, S.; Eisner, W.; Müller, J.-U.; et al. Pallidal deep brain stimulation in patients with primary generalised or segmental dystonia: 5-year follow-up of a randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. 2012, 11, 1029–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deuschl, G.; Schade-Brittinger, C.; Krack, P.; Volkmann, J.; Schäfer, H.; Bötzel, K.; Daniels, C.; Deutschländer, A.; Dillmann, U.; Eisner, W.; et al. A Randomized Trial of Deep-Brain Stimulation for Parkinson's Disease. New Engl. J. Med. 2006, 355, 896–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidailhet, M.; Vercueil, L.; Houeto, J.-L.; Krystkowiak, P.; Benabid, A.-L.; Cornu, P.; Lagrange, C.; Du Montcel, S.T.; Dormont, D.; Grand, S.; et al. Bilateral Deep-Brain Stimulation of the Globus Pallidus in Primary Generalized Dystonia. New Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, F.M. Bilateral Deep Brain Stimulation vs Best Medical Therapy for Patients With Advanced Parkinson DiseaseA Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA 2009, 301, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasano, A.; Lozano, A.M. Deep brain stimulation for movement disorders. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2015, 28, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, B.; Milosevic, L.; Kondrataviciute, L.; Kalia, L.V.; Kalia, S.K. Neuroscience fundamentals relevant to neuromodulation: Neurobiology of deep brain stimulation in Parkinson's disease. Neurotherapeutics 2024, 21, e00348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, W.-J.; A Steiner, L.; Milosevic, L. Neurophysiological mechanisms of deep brain stimulation across spatiotemporal resolutions. Brain 2023, 146, 4456–4468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, C.C.; Anderson, R.W. Deep brain stimulation mechanisms: the control of network activity via neurochemistry modulation. J. Neurochem. 2016, 139, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marras, C.; Lang, A. Parkinson's disease subtypes: lost in translation? J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2012, 84, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutet, A.; Madhavan, R.; Elias, G.J.B.; Joel, S.E.; Gramer, R.; Ranjan, M.; Paramanandam, V.; Xu, D.; Germann, J.; Loh, A.; et al. Predicting optimal deep brain stimulation parameters for Parkinson’s disease using functional MRI and machine learning. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokkonen, A.; Honkanen, E.A.; Corp, D.T.; Joutsa, J. Neurobiological effects of deep brain stimulation: A systematic review of molecular brain imaging studies. NeuroImage 2022, 260, 119473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutet, A.; Lozano, A.M. Deep Brain Stimulation and Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Future Directions. In Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Deep Brain Stimulation; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; pp. 121–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thenganatt, M.A.; Jankovic, J. Parkinson Disease Subtypes. JAMA Neurol. 2014, 71, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, K.P.; Bain, P.; Bajaj, N.; Elble, R.J.; Hallett, M.; Louis, E.D.; Raethjen, J.; Stamelou, M.; Testa, C.M.; Deuschl, G.; et al. Consensus Statement on the classification of tremors. from the task force on tremor of the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society. Mov. Disord. 2017, 33, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nambu, A.; Tokuno, H.; Takada, M. Functional significance of the cortico–subthalamo–pallidal ‘hyperdirect’ pathway. Neurosci. Res. 2002, 43, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.-L.; Chen, Y.-C.; Tu, P.-H.; Liu, T.-C.; Chen, M.-C.; Wu, H.-T.; Yeap, M.-C.; Yeh, C.-H.; Lu, C.-S.; Chen, C.-C. Subthalamic high-beta oscillation informs the outcome of deep brain stimulation in patients with Parkinson's disease. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 958521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanekamp, S.; Simonyan, K. The large-scale structural connectome of task-specific focal dystonia. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2020, 41, 3253–3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghu, A.L.B.; Eraifej, J.; Sarangmat, N.; Stein, J.; FitzGerald, J.J.; Payne, S.; Aziz, T.Z.; Green, A.L. Pallido-putaminal connectivity predicts outcomes of deep brain stimulation for cervical dystonia. Brain 2021, 144, 3589–3596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagel, J.M.; Wolf, M.E.; Blahak, C.; Runge, J.; Schrader, C.; Dressler, D.; Saryyeva, A.; Krauss, J.K. Thalamic Deep Brain Stimulation for Dystonic Head Tremor: A Long-Term Study of 18 Patients. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pr. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, E.B.; Gale, J.T. Mechanisms of action of deep brain stimulation (DBS). Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2008, 32, 388–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, A.M.; Lipsman, N. Probing and Regulating Dysfunctional Circuits Using Deep Brain Stimulation. Neuron 2013, 77, 406–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceballos-Baumann, A.O.; Boecker, H.; Bartenstein, P.; von Falkenhayn, I.; Riescher, H.; Conrad, B.; Moringlane, J.R.; Alesch, F. A Positron Emission Tomographic Study of Subthalamic Nucleus Stimulation in Parkinson Disease. Arch. Neurol. 1999, 56, 997–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hvingelby, V.; Khalil, F.; Massey, F.; Hoyningen, A.; Xu, S.S.; Candelario-McKeown, J.; Akram, H.; Foltynie, T.; Limousin, P.; Zrinzo, L.; et al. Directional deep brain stimulation electrodes in Parkinson’s disease: meta-analysis and systematic review of the literature. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2025, 96, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassal, F.; Dilly, D.; Boutet, C.; Bertholon, F.; Charier, D.; Pommier, B. White matter tracts involved by deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus in Parkinson’s disease: a connectivity study based on preoperative diffusion tensor imaging tractography. Br. J. Neurosurg. 2020, 34, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahan, J.; Urner, M.; Moran, R.; Flandin, G.; Marreiros, A.; Mancini, L.; White, M.; Thornton, J.; Yousry, T.; Zrinzo, L.; et al. Resting state functional MRI in Parkinson’s disease: the impact of deep brain stimulation on ‘effective’ connectivity. Brain 2014, 137, 1130–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, R.; He, L.; Ma, X.; Ma, Y.; Li, X. Connectome-Based Model Predicts Deep Brain Stimulation Outcome in Parkinson's Disease. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 571527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okromelidze, L.; Tsuboi, T.; Eisinger, R.; Burns, M.; Charbel, M.; Rana, M.; Grewal, S.; Lu, C.-Q.; Almeida, L.; Foote, K.; et al. Functional and Structural Connectivity Patterns Associated with Clinical Outcomes in Deep Brain Stimulation of the Globus Pallidus Internus for Generalized Dystonia. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2020, 41, 508–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filip, P.; Jech, R.; Fečíková, A.; Havránková, P.; Růžička, F.; Mueller, K.; Urgošík, D. Restoration of functional network state towards more physiological condition as the correlate of clinical effects of pallidal deep brain stimulation in dystonia. Brain Stimul. 2022, 15, 1269–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzic, L.; Voegtle, A.; Farahat, A.; Hartong, N.; Galazky, I.; Nasuto, S.J.; Andrade, A.d.O.; Knight, R.T.; Ivry, R.B.; Voges, J.; et al. Deep brain stimulation of the ventrointermediate nucleus of the thalamus to treat essential tremor improves motor sequence learning. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2022, 43, 4791–4799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atsumi, H.; Matsumae, M. Fusing of Preoperative Magnetic Resonance and Intraoperative O-arm Images in Deep Brain Stimulation Enhance Intuitive Surgical Planning and Increase Accuracy of Lead Placement. Neurol. Med.-Chir 2021, 61, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinke, R.S.; Selvaraj, A.K.; Geerlings, M.; Georgiev, D.; Sadikov, A.; Kubben, P.L.; Doorduin, J.; Praamstra, P.; Bloem, B.R.; Bartels, R.H.; et al. The Role of Microelectrode Recording and Stereotactic Computed Tomography in Verifying Lead Placement During Awake MRI-Guided Subthalamic Nucleus Deep Brain Stimulation for Parkinson’s Disease. J. Park. Dis. 2022, 12, 1269–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massager, N.; Nguyen, A.; Pouleau, H.-B.; Dethy, S.; Morelli, D. Deviation of DBS Recording Microelectrodes during Insertion Assessed by Intraoperative CT. Ster. Funct. Neurosurg. 2023, 101, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauss, J.K.; Lipsman, N.; Aziz, T.; Boutet, A.; Brown, P.; Chang, J.W.; Davidson, B.; Grill, W.M.; Hariz, M.I.; Horn, A.; et al. Technology of deep brain stimulation: current status and future directions. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2020, 17, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Escobar, M.C.; Elkins, R.; Murray, A.; Brandmeir, N.; Brandmeir, C.; Pallavaram, S.; Tripathi, R.; Elkins, R.A. Directional Deep Brain Stimulation Programming in Parkinson's Disease and Essential Tremor Patients: An Institution-Based Study. Cureus 2025, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umemura, A.; Mizuno, H.; Maki, M.; Masago, A. Image-guided optimization of current steering in STN-DBS for Parkinson's disease. Front. Neurol. 2025, 16, 1618480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilron, R.; Little, S.; Perrone, R.; Wilt, R.; de Hemptinne, C.; Yaroshinsky, M.S.; Racine, C.A.; Wang, S.S.; Ostrem, J.L.; Larson, P.S.; et al. Long-term wireless streaming of neural recordings for circuit discovery and adaptive stimulation in individuals with Parkinson’s disease. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 1078–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, W.-J.; Turner, R.S.; Blankertz, B.; Mitchell, T.; Kühn, A.A.; Richardson, R.M. Toward Electrophysiology-Based Intelligent Adaptive Deep Brain Stimulation for Movement Disorders. Neurotherapeutics 2019, 16, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dembek, T.A.; Roediger, J.; Horn, A.; Reker, P.; Oehrn, C.; Dafsari, H.S.; Li, N.; Kühn, A.A.; Fink, G.R.; Visser-Vandewalle, V.; et al. Probabilistic sweet spots predict motor outcome for deep brain stimulation in Parkinson disease. Ann. Neurol. 2019, 86, 527–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altoum, S.; Suliman, O.; Abulaban, N. Clinical Outcomes and Pathophysiological Correlates of Deep Brain Stimulation in Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review. J. Adv. Med. Med Res. 2025, 37, 342–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidetti, M.; Marceglia, S.; Bocci, T.; Duncan, R.; Fasano, A.; Foote, K.D.; Hamani, C.; Krauss, J.K.; Kühn, A.A.; Lena, F.; et al. Physical therapy in patients with Parkinson’s disease treated with Deep Brain Stimulation: a Delphi panel study. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójcik, R.; Dębska, A.; Zaczkowski, K.; Szmyd, B.; Podstawka, M.; Bobeff, E.J.; Piotrowski, M.; Ratajczyk, P.; Jaskólski, D.J.; Wiśniewski, K. Deep Brain Stimulation for Parkinson’s Disease—A Narrative Review. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salzmann, L.; Bichsel, O.; Rohr-Fukuma, M.; Naef, A.C.; Stieglitz, L.; Oertel, M.F.; Bujan, B.; Jedrysiak, P.; Lambercy, O.; Imbach, L.L.; et al. Lower limb motor effects of DBS neurofeedback in Parkinson’s disease assessed through IMU-based UPDRS movement quality metrics. Sci. Rep. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marano, M.; Tinkhauser, G.; Anzini, G.; Leogrande, G.; Ricciuti, R.; Paniccia, M.; Belli, A.; Pierleoni, P.; Di Lazzaro, V.; Raggiunto, S. Subthalamic beta power and gait in Parkinson's disease during unsupervised remote monitoring. Park. Relat. Disord. 2025, 107903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonergan, B.; Seemungal, B.M.; Ciocca, M.; Tai, Y.F. The Effects of Deep Brain Stimulation on Balance in Parkinson’s Disease as Measured Using Posturography—A Narrative Review. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferriero, G.; Magro, V.M.; Ferrara, P.E.; Ariani, M.; Coraci, D.; Codazza, S.; Maggi, L.; Ronconi, G. Deep-Brain Stimulation and Intensive Rehabilitation in a Patient with Parkinson Disease: A Case Report. Am. J. Case Rep. 2025, 26, e946308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canesi, M.; Lippi, L.; Rivaroli, S.; Vavassori, D.; Trenti, M.; Sartorio, F.; Meucci, N.; de Sire, A.; Siri, C.; Invernizzi, M. Long-Term Impact of Deep Brain Stimulation in Parkinson’s Disease: Does It Affect Rehabilitation Outcomes? Medicina 2024, 60, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouthour, W.; Mégevand, P.; Donoghue, J.; Lüscher, C.; Birbaumer, N.; Krack, P. Biomarkers for closed-loop deep brain stimulation in Parkinson disease and beyond. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2019, 15, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Zhu, G.; Shi, L.; Zhang, C.; Wu, B.; Yang, A.; Meng, F.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, J. Closed-Loop Adaptive Deep Brain Stimulation in Parkinson’s Disease: Procedures to Achieve It and Future Perspectives. J. Park. Dis. 2023, 13, 453–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.M.; Coelho, L.; Carvalho, E.; Ferreira-Pinto, M.J.; Vaz, R.; Aguiar, P. Machine learning for adaptive deep brain stimulation in Parkinson’s disease: closing the loop. J. Neurol. 2023, 270, 5313–5326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrò, R.S. Integrating Body Schema and Body Image in Neurorehabilitation: Where Do We Stand and What’s Next? Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köchli, S.; Casso, I.; Delevoye-Turrell, Y.N.; Schmid, S.; Rose, D.C.; Whyatt, C. A New Methodological Approach Integrating Motion Capture and Pressure-Sensitive Gait Data to Assess Functional Mobility in Parkinson’s Disease: A Two-Phase Study. Sensors 2025, 25, 5999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surridge, R.; Stilp, C.; Johnson, C.; Brumitt, J. The Use of Virtual Reality to Improve Gait and Balance in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease: A Scoping Review. Virtual Worlds 2025, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Technology | Core feature | Clinical / rehabilitation relevance |

|---|---|---|

| High-field MRI + tractography |

Patient-specific visualization of relevant pathways | Improves targeting precision and reduces side effects, supporting alignment of stimulation with functional goals |

| Directional leads | Current steering toward therapeutic pathways | Widens therapeutic window; improves stability for high-intensity rehabilitation |

| Sensing-enabled DBS | Continuous monitoring of physiological biomarkers | Enables objective programming and reduces variability affecting therapy performance |

| Adaptive DBS (closed-loop) |

Stimulation delivered when biomarkers exceed thresholds | Improves gait/tremor stability and supports timing of rehabilitation tasks |

| Wearable motor sensors | Continuous monitoring of gait, tremor, bradykinesia | Enables therapy personalization and home-based training |

| Connectomic programming platforms |

Lead reconstructions + pathway-activation modeling | Supports individualized programming based on patient-specific networks |

| Mechanistic level | Key mechanisms | Rehabilitation relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Microscale (neuronal) |

Axonal activation; somatic suppression; altered firing patterns | Stabilizes motor output and supports consistent performance during training |

| Mesoscale (oscillatory) |

Beta suppression; ERNA; short-latency entrainment | Enhances motor learning and improves within-session stability |

| Macroscale (network) |

Modulation of hyperdirect, cerebellothalamic, and pallidothalamic circuits | Aligns stimulation with gait, fine-motor, and functional rehabilitation goals |

| Non-neuronal/ molecular |

Astrocytic modulation, adenosine release, trophic signaling | Supports adaptive plasticity and learning-dependent improvement |

| Technology | Core feature | Clinical / rehabilitation relevance |

|---|---|---|

| High-field MRI + tractography |

Patient-specific visualization of relevant pathways | Improves targeting precision and reduces side effects, supporting alignment of stimulation with functional goals |

| Directional leads | Current steering toward therapeutic pathways | Widens therapeutic window; improves stability for high-intensity rehabilitation |

| Sensing-enabled DBS | Continuous monitoring of physiological biomarkers | Enables objective programming and reduces variability affecting therapy performance |

| Adaptive DBS (closed-loop) |

Stimulation delivered when biomarkers exceed thresholds | Improves gait/tremor stability and supports timing of rehabilitation tasks |

| Wearable motor sensors | Continuous monitoring of gait, tremor, bradykinesia | Enables therapy personalization and home-based training |

| Connectomic programming platforms | Lead reconstructions + pathway-activation modeling | Supports individualized programming based on patient-specific networks |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).