1. Introduction

Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer-related mortality and presenting a persistent challenge to the oncology community [

1]. For many decades, treatment options were quite limited for patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) who did not have specific genetic mutations—such as

EGFR and

ALK—that could be targeted with drugs [

2]. During this time, the standard treatment was almost exclusively platinum-based cytotoxic chemotherapy [

3]. While chemotherapy was able to shrink tumors for a short time, these treatments had significant drawbacks. Patients often suffered from severe side effects, and the positive results were usually temporary [

4]. Consequently, there was a desperate need for new treatments that could keep the disease under control for a longer period.

Everything changed with the arrival of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). Specifically, drugs that target the Programmed Cell Death-1 (PD-1) receptor or its partner, PD-L1, have completely revolutionized how we treat this disease [

5]. Instead of attacking cancer cells directly like chemotherapy, these new drugs work by blocking the "brakes" that stop the immune system from working [

6]. By removing these barriers, they wake up the patient's own T cells, allowing the immune system to recognize and destroy cancer cells. This approach has offered the possibility of long-term survival, something that was previously impossible to achieve [

7].

The first wave of these PD-1 inhibitors, most notably pembrolizumab and nivolumab, established this type of therapy as a foundation of modern cancer care [

8,

9]. However, the number of approved drugs has grown rapidly, adding a new layer of complexity for doctors. Clinicians now face a difficult task: they must choose the best option from a growing list of drugs that, on the surface, seem to target the same biological pathway. However, these drugs are not all the same. Small differences in how the antibodies are built—such as their structure, how they were engineered, where exactly they bind to the target, and how they interact with sugar molecules (glycosylation)—can lead to meaningful differences in how well they work, how safe they are, and how the body reacts to them [

10,

11].

Cemiplimab (Libtayo®) represents a sophisticated step forward in this class of medications. It is a fully human monoclonal antibody with high affinity, designed with a specific structure known as IgG4 [

12]. While approval status varies by country, cemiplimab has been approved for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma [

13], basal cell carcinoma [

14], and cervical cancer [

15]. Regarding NSCLC, it was approved by the United States in February 2021 and by Europe in June 2021. Subsequently, it was approved in Japan in September 2025. This approval covers a wide range of uses: it can be used as monotherapy for patients with high PD-L1 levels, or in combination with chemotherapy for a broader group of patients.

The purpose of this review is to answer the critical question: "Why choose Cemiplimab?" To do this, we will examine its unique structural biology in detail. We will specifically look at its stabilized backbone and its unique binding method that depends on the N58-glycan, comparing these special features with other well-known inhibitors. Furthermore, we will analyze important long-term data from the EMPOWER-Lung clinical trials. Based on this evidence, we propose that cemiplimab fills a unique and potentially superior role in therapy, particularly for patients with "ultra-high" PD-L1 expression and those with squamous NSCLC.

2. Molecular Characteristics

2.1. The IgG4 Backbone and the S228P Mutation: Ensuring Stability and Low Immunogenicity

To truly understand why cemiplimab is unique in a clinical setting, we must look closely at how the molecule was designed. Monoclonal antibodies are not simple drugs; they are complex proteins known as glycoproteins. Even tiny changes in their shape or amino acid sequence can have a huge impact on how long they last in the bloodstream and how well they attach to their targets. Therefore, the specific engineering choices made for cemiplimab give us a strong reason to believe it works differently than older drugs.

Cemiplimab is built using a specific type of antibody framework called Immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4). In the world of cancer immunotherapy, scientists often choose IgG4 instead of the more common IgG1. The reason for this choice is safety. IgG4 has a lower tendency to interact with other parts of the immune system (specifically, it has low affinity for Fc gamma receptors and C1q) than IgG1 [

16].

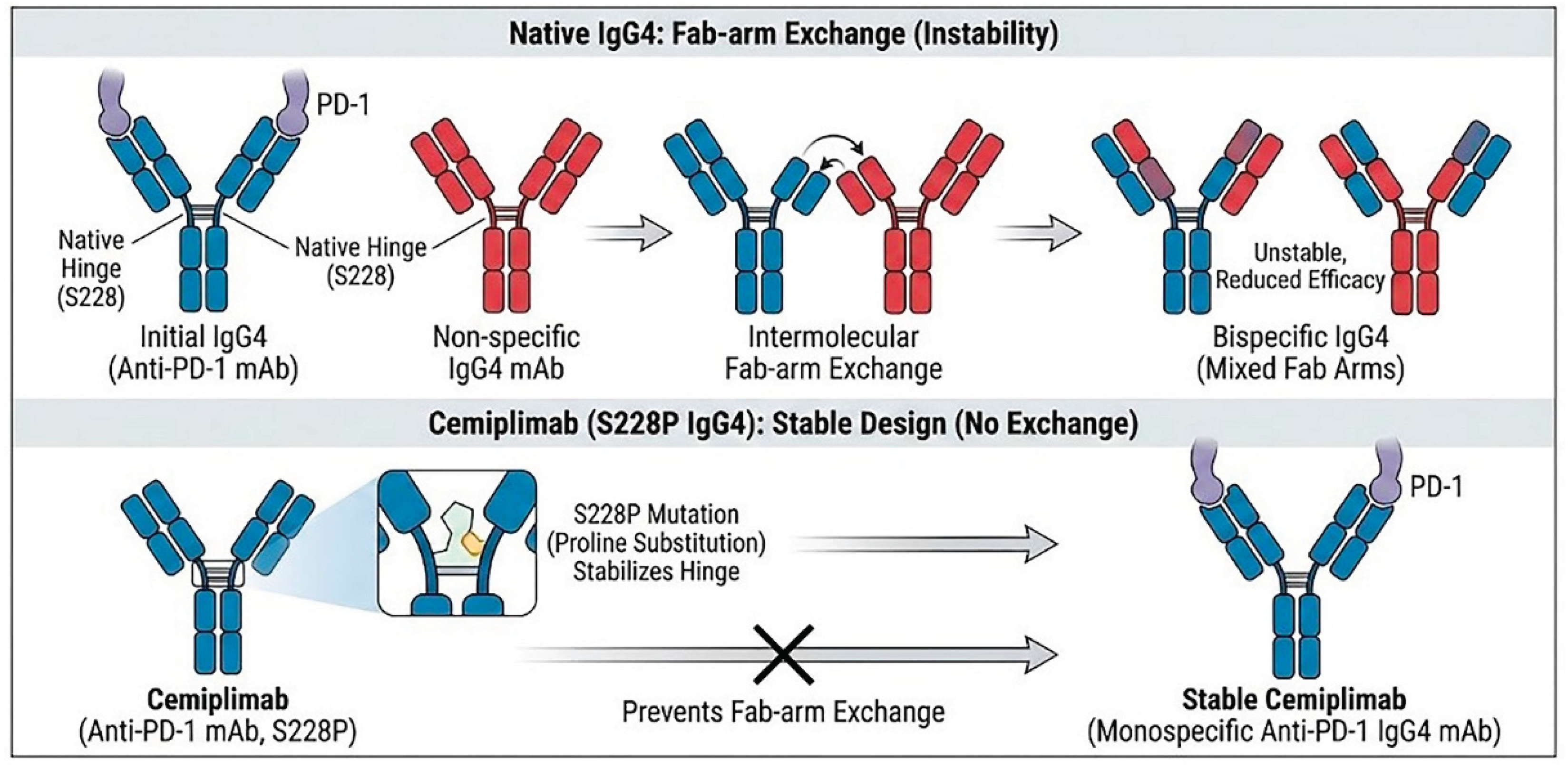

However, naturally occurring human IgG4 antibodies possess a unique structural instability known as "Fab-arm exchange" [

16]. In vivo, the heavy chains of IgG4 molecules can dissociate and re-associate with heavy chains from other disparate IgG4 molecules present in the plasma. This phenomenon results in the formation of bispecific antibodies that are functionally monovalent for their original target. Such structural fluidity can lead to unpredictable pharmacokinetics and reduced therapeutic efficacy, as the antibody loses the avidity gained from bivalent binding [

17].

To circumvent this instability, cemiplimab was engineered with a critical serine-to-proline substitution at amino acid position 228 (S228P) in the hinge region (

Figure 1). This mutation introduces rigidity to the inter-chain disulfide bonds, effectively mimicking the stable hinge structure of an IgG1 antibody while retaining the low effector function of IgG4 [

18]. This engineering ensures that cemiplimab remains a stable, bivalent molecule capable of high-affinity binding throughout its circulation time.

2.2. Anti-Drug Antibodies (ADAs) and Immunogenicity

Therapeutic monoclonal antibodies can be recognized as foreign antigens by the patient's immune system, potentially inducing the production of anti-drug antibodies (ADAs). The formation of ADAs is a critical factor in treatment failure, as they can accelerate the clearance of the drug from the body, leading to reduced blood concentrations, and may also directly neutralize the drug's biological activity, thereby attenuating its efficacy [

19]. In fact, the correlation between ADA production and reduced efficacy was demonstrated in the clinical trials evaluating atezolizumab. A pooled analysis revealed that patients who developed treatment-emergent ADAs exhibited a less favorable hazard ratio for overall survival (HR 0.89) compared to those who remained ADA-negative (HR 0.68), suggesting that the accelerated drug clearance associated with ADAs can attenuate the therapeutic benefit [

20,

21].

In the context of ICIs, data indicates that cemiplimab may possess a favorable immunogenicity profile, with a lower incidence of ADA production compared to other existing ICIs. Clinical data indicates a remarkably low incidence of treatment-emergent ADAs, ranging from approximately 0% to 2.6% [

22]. This suggests that the stabilized IgG4 structure of cemiplimab is viewed as "self" by the human immune system and is highly stable in vivo. In marked contrast, a systematic review comprising 141 trials across 16 tumor types revealed considerably higher immunogenicity profiles for other widely used checkpoint inhibitors [

23]. Specifically, atezolizumab demonstrated the highest incidence of treatment-emergent ADAs, with rates reported at 29.6% in large-scale studies and ranging up to 54.1% across individual trials [

21,

23,

24]. Nivolumab also exhibits a comparatively high immunogenicity profile, with pooled FDA data indicating an ADA incidence of 11.2% [

25]. While pembrolizumab generally displays a lower immunogenicity profile comparable to cemiplimab in pooled analyses, incidences as high as 20% have been documented in certain trial settings. Collectively, these comparative data underscore the unique stability of cemiplimab’s molecular design in minimizing immunogenic responses relative to other agents in the class.

Generally, the production of ADAs is more likely to occur in physiological states characterized by heightened immune function. Squamous NSCLC is typically associated with a high tumor mutation burden (TMB) [

26], where the accumulation of somatic mutations leads to the generation of neoantigens and a subsequent robust induction of immune responses [

27]. Therefore, squamous NSCLC, characterized by heightened immune reactivity, inherently possesses a predisposition for ADA generation. In this context, prioritizing cemiplimab, which may exhibit a lower immunogenic potential compared with other ICIs, could offer a strategic advantage, potentially translating into durable responses and long-term survival benefits.

2.3. Critical Role of PD-1 Glycosylation (N58-Glycan)

Recent mechanistic insights have elucidated that post-translational modifications of PD-1 play a critical role in immune checkpoint regulation. Specifically, glycosylation at the asparagine 58 (N58) position of PD-1 significantly enhances the affinity of the PD-1/PD-L1 interaction, thereby reinforcing T-cell suppression [

28]. In this context, cemiplimab distinguishes itself from other anti-PD-1 agents, such as pembrolizumab and nivolumab, through its unique binding properties. Cemiplimab specifically recognizes and binds to the N58-glycosylated form of PD-1, a feature that may allow for more efficient steric inhibition of the PD-1/PD-L1 axis in tumors where this glycosylation is prevalent [

29].

This structural differentiation may underlie the divergent clinical outcomes observed in squamous cell carcinomas. The glycosyltransferase B3GNT2 has been identified as a key enzyme driving PD-1 glycosylation and serving as a resistance factor to conventional immunotherapy; its expression levels inversely correlate with the efficacy of existing anti-PD-1 antibodies. Crucially, genomic analyses have revealed increased copy numbers of B3GNT2 specifically in lung squamous cell carcinoma [

30]. In fact, in the adjuvant setting for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, a pivotal trial evaluating cemiplimab met its primary endpoint, whereas a comparable study involving pembrolizumab failed to demonstrate a similar benefit [

31].

These findings collectively suggest that in tumors exhibiting hyper-glycosylation of PD-1, such as squamous cell carcinomas, standard checkpoint inhibitors may be less effective due to their inability to adequately block the strengthened PD-1/PD-L1 interface. Therefore, cemiplimab, by virtue of its ability to target these glycosylated variants, may fill a critical therapeutic gap, offering potential efficacy in patient populations that are intrinsically resistant to other agents.

3. Evidence from Pivotal Trials

3.1. EMPOWER-Lung 1

The clinical utility of cemiplimab in NSCLC has been established through the robust EMPOWER-Lung program. These large Phase 3 trials were designed to test the drug in populations that reflect real-world clinical practice, providing the evidentiary basis for its specific therapeutic positioning.

EMPOWER-Lung 1 trial was a large, multicenter, open-label Phase 3 study designed to compare cemiplimab monotherapy against investigator's choice of platinum-doublet chemotherapy in patients with locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC [

32,

33,

34]. The study enrolled patients with PD-L1 ≥ 50% and no

EGFR,

ALK, or

ROS1 alterations. This study was designed with overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) as the primary endpoints, assessed by a blinded independent central review (BICR). Key secondary endpoints included the objective response rate (ORR) and duration of response (DOR) per BICR, alongside safety evaluations. Additionally, exploratory analyses were pre-specified to evaluate efficacy outcomes stratified by PD-L1 expression levels (≥90%, 61–89%, and ≤60%).

During the enrollment phase, a significant challenge emerged regarding the accuracy of PD-L1 expression assessment. It was identified that PD-L1 testing performed at a specific laboratory facility did not meet quality standards, which affected a subset of the enrolled population. Consequently, re-testing of samples was required to verify eligibility. To address this issue and ensure the robustness of the data, the study defined a modified intention-to-treat (mITT) population. The mITT-1 population (n=563) comprised patients with confirmed PD-L1 expression of ≥50%, including those randomized with valid initial testing (mITT-2, n=475) and those from the affected group whose eligibility (PD-L1 ≥50%) was subsequently confirmed upon re-testing (n=88). In agreement with regulatory authorities, sensitivity analyses for the primary endpoints were conducted within this mITT-1 population in addition to the primary analysis of the ITT population.

A notable feature of this trial was its ethical crossover design; patients who started on chemotherapy were allowed to switch to cemiplimab if their disease progressed. Despite a high effective crossover rate of 73.9%, cemiplimab demonstrated a statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in survival. In the 5-year update presented in 2024, the median OS for patients in the cemiplimab arm was 26.1 months (95% CI: 22.1–31.9), compared to 13.3 months (95% CI: 10.5–16.2) for the chemotherapy arm. This survival advantage was statistically significant, with a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.59 (95% CI: 0.48–0.72; p<0.0001) in the population with confirmed PD-L1 ≥ 50%, with results favoring cemiplimab across generally all subgroups. The long-term durability of the response was further evidenced by the 5-year survival rate, which was nearly double for the immunotherapy group at 29.0%, versus 15.0% for those treated with chemotherapy. PFS also favored cemiplimab, with a median PFS of 8.1 months versus 5.3 months for chemotherapy (HR 0.50; 95% CI: 0.41–0.61; p<0.0001). Consistent benefits favoring cemiplimab were observed across all subgroups.

The most striking finding from EMPOWER-Lung 1 came from a pre-specified analysis of patients with "ultra-high" PD-L1 expression, defined as a Tumor Proportion Score (TPS) of 90% or greater. In the subgroup of patients with PD-L1 ≥90%), cemiplimab demonstrated a substantial survival benefit compared with chemotherapy. The median OS was 38.8 months (95% CI: 22.9–NE) in the cemiplimab arm versus 13.7 months (95% CI: 8.8–20.6) in the chemotherapy arm, corresponding to a HR of 0.442 (95% CI: 0.303–0.645). Similarly, PFS was significantly prolonged with cemiplimab, with a median PFS of 14.7 months compared to 5.1 months for chemotherapy (HR 0.321; 95% CI: 0.222–0.464). Furthermore, the ORR was markedly higher in the cemiplimab group at 60.6% (95% CI: 50.3–70.3) versus 17.9% (95% CI: 10.8–27.1) in the chemotherapy group (odds ratio 7.080; 95% CI: 3.650–13.731). These findings underscore the particularly high expectations for cemiplimab as a therapeutic option for this specific population.

With a 5-year follow-up, the safety profile of cemiplimab remains manageable and consistent with the established profile of other anti–PD-1 monotherapies. Any-grade treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were reported in 62.9% of patients in the cemiplimab group, compared with 90.4% in the chemotherapy group. Notably, the incidence of Grade ≥3 TEAEs was lower with cemiplimab (18.3%) than with chemotherapy (39.9%). Treatment discontinuation due to TEAEs occurred in 7.3% of patients receiving cemiplimab. Overall, these data indicate no new safety signals or specific concerns relative to comparable regimens.

3.2. EMPOWER-Lung 3

While monotherapy is excellent for high expressors, many patients require the immediate tumor-shrinking power of chemotherapy combined with immunotherapy. The EMPOWER-Lung 3 trial addressed this need. This double-blind, randomized Phase 3 study evaluated cemiplimab (350 mg every 3 weeks) combined with four cycles of platinum-doublet chemotherapy, versus placebo plus chemotherapy [

35,

36]. The trial enrolled 466 patients regardless of PD-L1 status or histology. The primary endpoint was OS. Key secondary endpoints included PFS and ORR, both of which were assessed by blinded independent central review. Additionally, the trial evaluated DOR per central review, best overall response determined by either central or investigator assessment, and safety profiles.

The 5-year follow-up results released in late 2025 confirmed the long-term durability of this regimen [

37]. In the overall population, the median OS was 21.1 months (95% CI: 15.9–23.9) with the cemiplimab plus chemotherapy versus 12.9 months (95% CI: 10.6–16.1) with chemotherapy alone (HR 0.66; 95% CI: 0.53–0.83). The 5-year survival rate was 19.4% for the cemiplimab plus chemotherapy arm compared to 8.8% for the chemotherapy arm. Consistent survival benefits favoring the cemiplimab plus chemotherapy regimen were generally observed across the majority of prespecified subgroups, including patients with squamous or non-squamous histology, those with a smoking history, and patients with PD-L1 expression of 1–49% (HR 0.50) or ≥50% (HR 0.56). While the overall trend was positive, the survival advantage appeared attenuated in the specific subgroups of patients with PD-L1 expression <1% (HR 0.94; 95% CI: 0.62–1.42). Cemiplimab plus chemotherapy also demonstrated a significant PFS benefit in the overall population, with a HR of 0.58 (95% CI: 0.47–0.72) [

37]. Subgroup analyses indicated a consistent survival advantage across key baseline characteristics, including histology and PD-L1 expression levels. Furthermore, a reduction in the risk of progression or death was observed across all PD-L1 subgroups, with HRs of 0.73 (95% CI: 0.50–1.08), 0.48 (95% CI: 0.34–0.68), and 0.48 (95% CI: 0.32–0.72) for the PD-L1 <1%, 1–49%, and ≥50% populations, respectively.

Subgroup analyses from the EMPOWER-Lung3 trial demonstrate that cemiplimab plus chemotherapy provides substantial clinical benefit in patients with squamous NSCLC. In the squamous population, cemiplimab plus chemotherapy achieved a median OS of 22.3 months compared with 13.8 months for chemotherapy, corresponding to an HR of 0.61 (95% CI: 0.42–0.87). A significant improvement was also observed in PFS, with a median of 8.2 months versus 4.9 months (HR 0.56; 95% CI: 0.41–0.78). Moreover, among patients with squamous histology and PD-L1 expression ≥1%, ORR was significantly higher with cemiplimab plus chemotherapy at 45.3% versus 25.5% with chemotherapy (odds ratio 2.42; 95% CI: 1.14–5.11; p=0.021). Collectively, these results underscore the strong therapeutic potential of cemiplimab plus chemotherapy for patients with squamous NSCLC, especially within the PD-L1 ≥1% subgroup.

In the safety analysis, any-grade adverse events were reported in 88.5% of patients treated with cemiplimab plus chemotherapy compared with 85.6% in the chemotherapy arm. Grade ≥3 adverse events occurred in 30.1% of patients in the combination arm versus 18.3% in the chemotherapy arm, and discontinuation rates due to adverse events were 4.2% and 1.3%, respectively. Although the addition of cemiplimab to chemotherapy was associated with an expected increase in adverse events, the overall safety profile was manageable and consistent with established data for other PD-1 inhibitor plus chemotherapy combinations, revealing no new or unexpected safety signals.

3.3. Japanese Phase I, Dose-Expansion Study

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of cemiplimab specifically in the Japanese population, a multicenter, open-label phase 1 study (NCT03233139) conducted a dose-expansion Part 2 analysis comprising two first-line treatment cohorts. The primary objectives were to assess safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics, while key secondary endpoints included the ORR and DOR per independent review committee, with PFS and OS assessed as exploratory endpoints [

38].

In Cohort A, patients with PD-L1 expression of ≥ 50% received cemiplimab monotherapy (350 mg IV Q3W). Among the 50 patients with centrally confirmed PD-L1 ≥ 50%, the ORR was 60.0% (90% CI: 48.6–71.4%). Survival outcomes were robust, with a median OS of 44.5 months (95% CI: 27.0–54.4) and a 1-year survival rate of 83.7%. The median PFS was not reached (95% CI: 12.5 months–NE), with a 1-year PFS rate of 67.7%. Notably, efficacy correlated with PD-L1 expression levels; patients with PD-L1 >90% achieved an ORR of 62.1%

In Cohort C, patients with any level of PD-L1 expression received cemiplimab (350 mg IV Q3W) in combination with platinum-doublet chemotherapy for four cycles. In this cohort (n=50), the ORR was 42.0% (90% CI: 30.5–53.5%). The median PFS was 8.1 months (95% CI: 6.0–NE), and the median OS was not reached (95% CI: 13.4–NE) at the time of data cut-off. Clinical benefit was observed regardless of PD-L1 status, including in patients with PD-L1 <1%.

These findings in Japanese patients are consistent with the survival benefits demonstrated in the global EMPOWER-Lung 1 and EMPOWER-Lung 3 trials, supporting the use of cemiplimab as a viable therapeutic option in this population. In this Japanese phase I study, cemiplimab demonstrated a safety profile generally consistent with global trials, with no new safety signals identified. While pneumonitis occurred in 21.7% of patients receiving monotherapy (Grade ≥3: 5.0%), this higher incidence may be attributable to the small sample size and longer treatment exposure compared to pivotal studies. Most adverse events were manageable, confirming a favorable benefit-risk profile in this population.

4. Strategic Positioning in Clinical Practice

4.1. Cemiplimab Monotherapy: Advantages in Squamous Histology and Ultra-High PD-L1 Subgroups

Based on the results of the KEYNOTE-024 trial, pembrolizumab monotherapy has firmly established itself as the global standard for the first-line treatment of metastatic NSCLC with PD-L1 ≥ 50%, demonstrating a median OS of 26.3 months and an HR of 0.62 compared to chemotherapy [

39]. However, the EMPOWER-Lung1 trial suggests that cemiplimab may possess a unique competitive edge, particularly when considering the heterogeneity of patient backgrounds; unlike KEYNOTE-024, EMPOWER-Lung1 enrolled a population with historically poorer prognostic factors, including a significantly higher proportion of squamous cell carcinoma (43.3% vs. 18.8%) and patients with clinically stable brain metastases [

32] (

Table 1). While subgroup analyses in KEYNOTE-024 indicated a somewhat attenuated benefit in squamous histology with an OS HR of 0.73 compared to 0.58 for non-squamous, cemiplimab demonstrated robust and consistent efficacy across histologies, notably achieving an OS HR of 0.51 in the squamous subgroup (

Table 2).

A compelling opportunity for Cemiplimab to penetrate the current standard of care lies within the "ultra-high" expression population defined as PD-L1 TPS ≥ 90%, a subgroup which was pre-specified for exploratory analysis in EMPOWER-Lung1. Biologically, tumors with PD-L1 ≥ 90% are distinct from those with 50-89% expression; they are characterized by a significantly higher density of intratumoral CD8+ PD-1+ T cells and a higher frequency of BRCA2 mutations [

40]. The presence of BRCA2 mutations involves defects in DNA repair genes, leading to an accumulation of somatic mutations and subsequent neoantigen production. This high TMB and neoantigen load induce a robust immune response, creating a highly immunogenic microenvironment that is also prone to the generation of ADAs due to the heightened immune activation. Given that ADA formation can neutralize therapeutic antibodies and attenuate efficacy, it is specifically within this population that cemiplimab, which is reported to exhibit lower ADA production compared to other ICIs, may yield the most substantial benefit in terms of OS and PFS. This biological rationale is corroborated by clinical data indicating superior outcomes for cemiplimab in the PD-L1 ≥ 90% population compared to available data for pembrolizumab. In EMPOWER-Lung1, the PD-L1 ≥ 90% cohort achieved a median OS of 38.8 months with a remarkable HR of 0.44. In contrast, a comparable cohort study by Ricciuti et al. reported that pembrolizumab in the PD-L1 ≥ 90% group showed a median OS of 30.4 months and an HR of 0.70 [

40], with PFS comparisons also favoring cemiplimab (HR 0.51 vs. 0.69). Although this cross-trial comparisons should be interpreted with caution due to differences in study design, cemiplimab demonstrates a strong potential to outperform the established standard in the context of PD-L1 ≥ 90% tumors where high immunogenicity and ADA risks intersect.

4.2. Cemiplimab Plus Chemotherapy: Clinical Value in Squamous Histology

For patients with metastatic NSCLC harboring PD-L1 expression levels of 1-49%, the combination of pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy is the established global standard of care (

Table 1 and

Table 3). This consensus is firmly built upon the robust long-term outcomes of the KEYNOTE-189 trial for non-squamous histology and the KEYNOTE-407 trial for squamous histology [

41,

42]. In KEYNOTE-189, the 5-year update demonstrated a HR for OS of 0.60, with a 5-year OS rate of 19.4%; specifically, within the PD-L1 1-49% subgroup, the HR was 0.65. Similarly, KEYNOTE-407 showed an OS HR of 0.71 and a 5-year OS rate of 18.4% for squamous patients, with the PD-L1 1-49% subgroup achieving an HR of 0.61. These data have set a high bar for any new entrant attempting to challenge this standard.

The EMPOWER-Lung3 trial, evaluating cemiplimab plus chemotherapy, introduces a unique perspective by including both squamous (42.4%) and non-squamous (57.6%) histologies within a single study design, distinguishing it from the histology-specific KEYNOTE trials (

Table 1). A critical heterogeneity in patient background lies in the ethnic composition; EMPOWER-Lung3 enrolled a significantly higher proportion of Asian patients (45.1%) compared to KEYNOTE-189 (24.0%) and KEYNOTE-407 (30.6%). This demographic distinction provides substantial data for Asian populations, potentially offering an evidence-based advantage in regions where this demographic is prevalent.

Regarding efficacy, cemiplimab plus chemotherapy demonstrated a median OS of 22.3 months and an HR of 0.61 in the squamous population across all PD-L1 levels, with a 5-year OS rate of 18.0%, outcomes that are numerically comparable to the benchmark set by KEYNOTE-407 (

Table 3). Although the specific Kaplan-Meier curves and detailed histology-stratified data for the PD-L1 1-49% subgroup are not fully detailed in the provided materials, the available data indicates that this regimen represents a promising therapeutic option for this specific intermediate expression group. Therefore, while pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy remains the dominant standard, cemiplimab plus chemotherapy holds potential to establish a position as a viable alternative, particularly supported by its robust performance in squamous cell carcinoma and its unique dataset enriched with Asian patients.

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Cemiplimab represents a sophisticated refinement in the class of anti-PD-1 therapies. The engineering of the S228P mutation ensures molecular stability and minimizes immunogenicity—evidenced by ADA rates significantly lower than those of atezolizumab and nivolumab—while its unique reliance on the N58-glycan for binding allows for high-affinity receptor occupancy that distinctively positions it against pembrolizumab.

These molecular features have translated into distinctive clinical benefits demonstrated in the EMPOWER-Lung program, which identified two distinct "therapeutic niches" where cemiplimab excels. Firstly, in the PD-L1 ≥90% "ultra-high" population, cemiplimab offers a median survival of nearly 39 months with monotherapy alone, providing the strongest evidence to date for this subgroup. Furthermore, in squamous cell carcinoma, cemiplimab provides a highly effective combination option with a median survival exceeding 22 months, thereby challenging historical norms for this difficult-to-treat histology. However, it is important to note that the efficacy data for the PD-L1 ≥90% and squamous cell carcinoma populations are derived from subgroup analyses. Therefore, these findings warrant cautious interpretation, and the further accumulation of real-world data is essential to validate these results.

In the setting of Stage IV NSCLC, while randomized controlled trials have demonstrated robust efficacy, the continued accumulation of real-world data remains essential to validate these benefits across diverse patient populations in routine clinical practice. Looking beyond metastatic disease, the potential of cemiplimab is expanding into earlier stages. Clinical trials are currently underway to evaluate its efficacy in the adjuvant and neoadjuvant settings for NSCLC. Given the positive results already seen with cemiplimab in adjuvant/neoadjuvant cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma [

43,

44], there is a strong biological rationale to anticipate similar success in lung cancer.

In conclusion, the approval of cemiplimab in Japan offers clinicians a powerful new option that allows for a more personalized approach to lung cancer treatment. Cemiplimab establishes a unique therapeutic niche for patients with squamous histology and ultra-high PD-L1 expression, likely driven by its distinct structural stability and reduced immunogenicity.

Author Contributions

S.I.: Conceptualization, Investigation, Visualization, Writing (Original Draft). K.A., M.K., N.M., Y.N., K.F., K,Y., T.I., K.N., Y.T, U.K., Y.Y., T.K.: Investigation, Writing (Review and Editing). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Miki Kajiwara, Ichiko Yamashita, and Wakana Tamura (Department of Thoracic Oncology, Kansai Medical University, Japan) for their efforts in data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Ikeda S received research funding from AstraZeneca, and Chugai Pharmaceutical; honoraria for lectures from AstraZeneca, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Bristol Myers Squibb, Ono Pharmaceutical, Taiho Pharmaceutical, Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, MSD, Daiichi Sankyo, Amgen, Novartis, and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals; and took on a consulting or advisory roles for AstraZeneca, Chugai Pharmaceutical, and Daiichi Sankyo. Araki K, Kitagawa M, Makihara N, Nagata Y, Fuji K, Yoshida K, Ikoma T, Nakahama K, Takeyasu Y, Katsushima U, and Yamanaka Y have nothing to disclose. Kurata T received research funding from MSD, AstraZeneca, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Takeda Pharmaceutical, and Bristol Myers Squibb; honoraria for lectures from AstraZeneca, Ono Pharmaceutical, MSD, Nippon Kayaku, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Eli Lilly, Bristol Myers Squibb, Chugai Pharmaceutical, and Pfizer.

References

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021 May;71(3):209-249.

- Jordan EJ, Kim HR, Arcila ME, Barron D, Chakravarty D, Gao J, Chang MT, Ni A, Kundra R, Jonsson P, Jayakumaran G, Gao SP, Johnsen HC, Hanrahan AJ, Zehir A, Rekhtman N, Ginsberg MS, Li BT, Yu HA, Paik PK, Drilon A, Hellmann MD, Reales DN, Benayed R, Rusch VW, Kris MG, Chaft JE, Baselga J, Taylor BS, Schultz N, Rudin CM, Hyman DM, Berger MF, Solit DB, Ladanyi M, Riely GJ. Prospective Comprehensive Molecular Characterization of Lung Adenocarcinomas for Efficient Patient Matching to Approved and Emerging Therapies. Cancer Discov. 2017 Jun;7(6):596-609.

- Schiller JH, Harrington D, Belani CP, Langer C, Sandler A, Krook J, Zhu J, Johnson DH; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Comparison of four chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002 Jan 10;346(2):92-8. [CrossRef]

- Scagliotti GV, Parikh P, von Pawel J, Biesma B, Vansteenkiste J, Manegold C, Serwatowski P, Gatzemeier U, Digumarti R, Zukin M, Lee JS, Mellemgaard A, Park K, Patil S, Rolski J, Goksel T, de Marinis F, Simms L, Sugarman KP, Gandara D. Phase III study comparing cisplatin plus gemcitabine with cisplatin plus pemetrexed in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008 Jul 20;26(21):3543-51.

- Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012 Mar 22;12(4):252-64.

- Ishida Y, Agata Y, Shibahara K, Honjo T. Induced expression of PD-1, a novel member of the immunoglobulin gene superfamily, upon programmed cell death. EMBO J. 1992 Nov;11(11):3887-95. [CrossRef]

- Borghaei H, Gettinger S, Vokes EE, Chow LQM, Burgio MA, de Castro Carpeno J, Pluzanski A, Arrieta O, Frontera OA, Chiari R, Butts C, Wójcik-Tomaszewska J, Coudert B, Garassino MC, Ready N, Felip E, García MA, Waterhouse D, Domine M, Barlesi F, Antonia S, Wohlleber M, Gerber DE, Czyzewicz G, Spigel DR, Crino L, Eberhardt WEE, Li A, Marimuthu S, Brahmer J. Five-Year Outcomes From the Randomized, Phase III Trials CheckMate 017 and 057: Nivolumab Versus Docetaxel in Previously Treated Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2021 Mar 1;39(7):723-733.

- Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, Hui R, Csőszi T, Fülöp A, Gottfried M, Peled N, Tafreshi A, Cuffe S, O'Brien M, Rao S, Hotta K, Leiby MA, Lubiniecki GM, Shentu Y, Rangwala R, Brahmer JR; KEYNOTE-024 Investigators. Pembrolizumab versus Chemotherapy for PD-L1-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016 Nov 10;375(19):1823-1833. [CrossRef]

- Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, Spigel DR, Steins M, Ready NE, Chow LQ, Vokes EE, Felip E, Holgado E, Barlesi F, Kohlhäufl M, Arrieta O, Burgio MA, Fayette J, Lena H, Poddubskaya E, Gerber DE, Gettinger SN, Rudin CM, Rizvi N, Crinò L, Blumenschein GR Jr, Antonia SJ, Dorange C, Harbison CT, Graf Finckenstein F, Brahmer JR. Nivolumab versus Docetaxel in Advanced Nonsquamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015 Oct 22;373(17):1627-39. [CrossRef]

- Fessas P, Lee H, Ikemizu S, Janowitz T. A molecular and preclinical comparison of the PD-1-targeted T-cell checkpoint inhibitors nivolumab and pembrolizumab. Semin Oncol. 2017 Apr;44(2):136-140. [CrossRef]

- Martins F, Sofiya L, Sykiotis GP, et al. Adverse effects of immune-checkpoint inhibitors: epidemiology, management and surveillance. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2019;16(9):563-580. [CrossRef]

- Burova E, Hermann A, Waite J, Potocky T, Lai V, Hong S, Liu M, Allbritton O, Woodruff A, Wu Q, D'Orvilliers A, Garnova E, Rafique A, Poueymirou W, Martin J, Huang T, Skokos D, Kantrowitz J, Popke J, Mohrs M, MacDonald D, Ioffe E, Olson W, Lowy I, Murphy A, Thurston G. Characterization of the Anti-PD-1 Antibody REGN2810 and Its Antitumor Activity in Human PD-1 Knock-In Mice. Mol Cancer Ther. 2017 May;16(5):861-870. [CrossRef]

- Migden MR, Rischin D, Schmults CD, Guminski A, Hauschild A, Lewis KD, Chung CH, Hernandez-Aya L, Lim AM, Chang ALS, Rabinowits G, Thai AA, Dunn LA, Hughes BGM, Khushalani NI, Modi B, Schadendorf D, Gao B, Seebach F, Li S, Li J, Mathias M, Booth J, Mohan K, Stankevich E, Babiker HM, Brana I, Gil-Martin M, Homsi J, Johnson ML, Moreno V, Niu J, Owonikoko TK, Papadopoulos KP, Yancopoulos GD, Lowy I, Fury MG. PD-1 Blockade with Cemiplimab in Advanced Cutaneous Squamous-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jul 26;379(4):341-351. [CrossRef]

- Stratigos AJ, Sekulic A, Peris K, Bechter O, Prey S, Kaatz M, Lewis KD, Basset-Seguin N, Chang ALS, Dalle S, Orland AF, Licitra L, Robert C, Ulrich C, Hauschild A, Migden MR, Dummer R, Li S, Yoo SY, Mohan K, Coates E, Jankovic V, Fiaschi N, Okoye E, Bassukas ID, Loquai C, De Giorgi V, Eroglu Z, Gutzmer R, Ulrich J, Puig S, Seebach F, Thurston G, Weinreich DM, Yancopoulos GD, Lowy I, Bowler T, Fury MG. Cemiplimab in locally advanced basal cell carcinoma after hedgehog inhibitor therapy: an open-label, multi-centre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021 Jun;22(6):848-857. [CrossRef]

- Tewari KS, Monk BJ, Vergote I, Miller A, de Melo AC, Kim HS, Kim YM, Lisyanskaya A, Samouëlian V, Lorusso D, Damian F, Chang CL, Gotovkin EA, Takahashi S, Ramone D, Pikiel J, Maćkowiak-Matejczyk B, Guerra Alía EM, Colombo N, Makarova Y, Rischin D, Lheureux S, Hasegawa K, Fujiwara K, Li J, Jamil S, Jankovic V, Chen CI, Seebach F, Weinreich DM, Yancopoulos GD, Lowy I, Mathias M, Fury MG, Oaknin A; Investigators for GOG Protocol 3016 and ENGOT Protocol En-Cx9. Survival with Cemiplimab in Recurrent Cervical Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022 Feb 10;386(6):544-555.

- Rispens T, Huijbers MG. The unique properties of IgG4 and its roles in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2023 Nov;23(11):763-778. [CrossRef]

- Chen X, Song X, Li K, Zhang T. FcγR-Binding Is an Important Functional Attribute for Immune Checkpoint Antibodies in Cancer Immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2019 Feb 26;10:292. [CrossRef]

- Yang X, Wang F, Zhang Y, Wang L, Antonenko S, Zhang S, Zhang YW, Tabrizifard M, Ermakov G, Wiswell D, Beaumont M, Liu L, Richardson D, Shameem M, Ambrogelly A. Comprehensive Analysis of the Therapeutic IgG4 Antibody Pembrolizumab: Hinge Modification Blocks Half Molecule Exchange In Vitro and In Vivo. J Pharm Sci. 2015 Dec;104(12):4002-4014. [CrossRef]

- Enrico D, Paci A, Chaput N, Karamouza E, Besse B. Antidrug Antibodies Against Immune Checkpoint Blockers: Impairment of Drug Efficacy or Indication of Immune Activation? Clin Cancer Res. 2020 Feb 15;26(4):787-792.

- Usdin M, Quarmby V, Zanghi J, Bernaards C, Liao L, Laxamana J, Wu B, Swanson S, Song Y, Siguenza P. Immunogenicity of Atezolizumab: Influence of Testing Method and Sampling Frequency on Reported Anti-drug Antibody Incidence Rates. AAPS J. 2024 Jul 15;26(4):84.

- Peters S, Galle PR, Bernaards CA, Ballinger M, Bruno R, Quarmby V, Ruppel J, Vilimovskij A, Wu B, Sternheim N, Reck M. Evaluation of atezolizumab immunogenicity: Efficacy and safety (Part 2). Clin Transl Sci. 2022 Jan;15(1):141-157. [CrossRef]

- Zucali PA, Lin CC, Carthon BC, Bauer TM, Tucci M, Italiano A, Iacovelli R, Su WC, Massard C, Saleh M, Daniele G, Greystoke A, Gutierrez M, Pant S, Shen YC, Perrino M, Meng R, Abbadessa G, Lee H, Dong Y, Chiron M, Wang R, Loumagne L, Lépine L, de Bono J. Targeting CD38 and PD-1 with isatuximab plus cemiplimab in patients with advanced solid malignancies: results from a phase I/II open-label, multicenter study. J Immunother Cancer. 2022 Jan;10(1):e003697. [CrossRef]

- Galle P, Finn RS, Mitchell CR, Ndirangu K, Ramji Z, Redhead GS, Pinato DJ. Treatment-emergent antidrug antibodies related to PD-1, PD-L1, or CTLA-4 inhibitors across tumor types: a systematic review. J Immunother Cancer. 2024 Jan 18;12(1):e008266. [CrossRef]

- Wu B, Sternheim N, Agarwal P, Suchomel J, Vadhavkar S, Bruno R, Ballinger M, Bernaards CA, Chan P, Ruppel J, Jin J, Girish S, Joshi A, Quarmby V. Evaluation of atezolizumab immunogenicity: Clinical pharmacology (part 1). Clin Transl Sci. 2022 Jan;15(1):130-140. [CrossRef]

- Agrawal S, Statkevich P, Bajaj G, Feng Y, Saeger S, Desai DD, Park JS, Waxman IM, Roy A, Gupta M. Evaluation of Immunogenicity of Nivolumab Monotherapy and Its Clinical Relevance in Patients With Metastatic Solid Tumors. J Clin Pharmacol. 2017 Mar;57(3):394-400. [CrossRef]

- Sha D, Jin Z, Budczies J, Kluck K, Stenzinger A, Sinicrope FA. Tumor Mutational Burden as a Predictive Biomarker in Solid Tumors. Cancer Discov. 2020 Dec;10(12):1808-1825.

- Chan TA, Yarchoan M, Jaffee E, Swanton C, Quezada SA, Stenzinger A, Peters S. Development of tumor mutation burden as an immunotherapy biomarker: utility for the oncology clinic. Ann Oncol. 2019 Jan 1;30(1):44-56. [CrossRef]

- Sun L, Li CW, Chung EM, Yang R, Kim YS, Park AH, Lai YJ, Yang Y, Wang YH, Liu J, Qiu Y, Khoo KH, Yao J, Hsu JL, Cha JH, Chan LC, Hsu JM, Lee HH, Yoo SS, Hung MC. Targeting Glycosylated PD-1 Induces Potent Antitumor Immunity. Cancer Res. 2020 Jun 1;80(11):2298-2310. [CrossRef]

- Lu D, Xu Z, Zhang D, Jiang M, Liu K, He J, Ma D, Ma X, Tan S, Gao GF, Chai Y. PD-1 N58-Glycosylation-Dependent Binding of Monoclonal Antibody Cemiplimab for Immune Checkpoint Therapy. Front Immunol. 2022 Mar 2;13:826045. [CrossRef]

- Joung J, Kirchgatterer PC, Singh A, Cho JH, Nety SP, Larson RC, Macrae RK, Deasy R, Tseng YY, Maus MV, Zhang F. CRISPR activation screen identifies BCL-2 proteins and B3GNT2 as drivers of cancer resistance to T cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Nat Commun. 2022 Mar 25;13(1):1606. [CrossRef]

- Rischin D, Porceddu S, Day F, Brungs DP, Christie H, Jackson JE, Stein BN, Su YB, Ladwa R, Adams G, Bowyer SE, Otty Z, Yamazaki N, Bossi P, Challapalli A, Hauschild A, Lim AM, Patel VA, Walker JL, De Liz Vassen Schurmann M, Queirolo P, Cañueto J, Ferreira da Silva FA, Stratigos A, Guminski A, Lin C, Damian F, Flatz L, Taylor AE, Carr DR, Harris S, Kirtbaya D, Quereux G, Rutkowski P, Basset-Seguin N, Khushalani NI, Robert C, Ju H, Joseph C, Bansal S, Chen CI, Seebach F, Yoo SY, Lowy I, Goncalves P, Fury MG; C-POST Trial Investigators. Adjuvant Cemiplimab or Placebo in High-Risk Cutaneous Squamous-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2025 Aug 21;393(8):774-785. [CrossRef]

- Sezer A, Kilickap S, Gümüş M, Bondarenko I, Özgüroğlu M, Gogishvili M, Turk HM, Cicin I, Bentsion D, Gladkov O, Clingan P, Sriuranpong V, Rizvi N, Gao B, Li S, Lee S, McGuire K, Chen CI, Makharadze T, Paydas S, Nechaeva M, Seebach F, Weinreich DM, Yancopoulos GD, Gullo G, Lowy I, Rietschel P. Cemiplimab monotherapy for first-line treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer with PD-L1 of at least 50%: a multicentre, open-label, global, phase 3, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2021 Feb 13;397(10274):592-604. [CrossRef]

- Kilickap S, Baramidze A, Sezer A, Özgüroğlu M, Gumus M, Bondarenko I, Gogishvili M, Nechaeva M, Schenker M, Cicin I, Fuang HG, Kulyaba Y, Zyuhal K, Scheusan RI, Garassino MC, Li Y, Zhu C, Kaul M, Perez J, Seebach F, Lowy I, Pouliot JF, Kim E, Magnan H. Cemiplimab Monotherapy for First-Line Treatment of Patients with Advanced NSCLC With PD-L1 Expression of 50% or Higher: Five-Year Outcomes of EMPOWER-Lung 1. J Thorac Oncol. 2025 Jul;20(7):941-954. [CrossRef]

- Kilickap S, Özgüroğlu M, Sezer A, Gümüş M, Bondarenko I, Gogishvili M, Turk HM, Cicin I, Bentsion D, Gladkov O, Sriuranpong V, Quek RGW, McIntyre DAG, He X, McGinniss J, Seebach F, Gullo G, Rietschel P, Pouliot JF. Cemiplimab monotherapy as first-line treatment of patients with brain metastases from advanced non-small cell lung cancer with programmed cell death-ligand 1 ≥50. Cancer. 2025 May 15;131(10):e35864.

- Gogishvili M, Melkadze T, Makharadze T, Giorgadze D, Dvorkin M, Penkov K, Laktionov K, Nemsadze G, Nechaeva M, Rozhkova I, Kalinka E, Gessner C, Moreno-Jaime B, Passalacqua R, Li S, McGuire K, Kaul M, Paccaly A, Quek RGW, Gao B, Seebach F, Weinreich DM, Yancopoulos GD, Lowy I, Gullo G, Rietschel P. Cemiplimab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone in non-small cell lung cancer: a randomized, controlled, double-blind phase 3 trial. Nat Med. 2022 Nov;28(11):2374-2380. [CrossRef]

- Makharadze T, Gogishvili M, Melkadze T, Baramidze A, Giorgadze D, Penkov K, Laktionov K, Nemsadze G, Nechaeva M, Rozhkova I, Kalinka E, Li S, Li Y, Kaul M, Quek RGW, Pouliot JF, Seebach F, Lowy I, Gullo G, Rietschel P. Cemiplimab Plus Chemotherapy Versus Chemotherapy Alone in Advanced NSCLC: 2-Year Follow-Up From the Phase 3 EMPOWER-Lung 3 Part 2 Trial. J Thorac Oncol. 2023 Jun;18(6):755-768. [CrossRef]

- Baramidze A, Makharadze T, Gogishvili M, Melkadze1 T, Giorgadze D, Penkov K, Laktionov K, Nemsadze G, Nechaeva M, Rozhkova I, Kalinka E, Li11 Y, McIntyre D.A, Jia X, Modi D, Perez J, Kaul M, Lowy I, Pouliot J.-F, Chua S, Kim E, Magnan H, Seebach F. MA10.09 Cemiplimab plus chemotherapy vs. chemotherapy in advanced NSCLC: 5-year results from phase 3 EMPOWER-Lung 3 Part 2 trial. J Thorac Oncol. 2025;20(10 suppl 1):s99. [CrossRef]

- Sato Y, Tani Y, Ishii H, Katakura S, Oki M, Watanabe Y, Yokoyama T, Naoki K, Pouliot JF, Kaul M, Paccaly A, Visich JE, Kim E, Mani J, Li Y, Lowy I, Seebach F, Mathias M, Ikeda S. Cemiplimab in Japanese patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2025 Oct 29:hyaf160. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyaf160. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef]

- Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, Hui R, Csőszi T, Fülöp A, Gottfried M, Peled N, Tafreshi A, Cuffe S, O'Brien M, Rao S, Hotta K, Leal TA, Riess JW, Jensen E, Zhao B, Pietanza MC, Brahmer JR. Five-Year Outcomes With Pembrolizumab Versus Chemotherapy for Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer With PD-L1 Tumor Proportion Score ≥ 50. J Clin Oncol. 2021 Jul 20;39(21):2339-2349. [CrossRef]

- Ricciuti B, Elkrief A, Lin J, Zhang J, Alessi JV, Lamberti G, Gandhi M, Di Federico A, Pecci F, Wang X, Makarem M, Hidalgo Filho CM, Gorria T, Saini A, Pabon C, Lindsay J, Pfaff KL, Welsh EL, Nishino M, Sholl LM, Rodig S, Kilickap S, Rietschel P, McIntyre DA, Pouliot JF, Altan M, Gainor JF, Heymach JV, Schoenfeld AJ, Awad MM. Three-Year Overall Survival Outcomes and Correlative Analyses in Patients With NSCLC and High (50%-89%) Versus Very High (≥90%) Programmed Death-Ligand 1 Expression Treated With First-Line Pembrolizumab or Cemiplimab. JTO Clin Res Rep. 2024 Apr 12;5(9):100675. [CrossRef]

- Garassino MC, Gadgeel S, Speranza G, Felip E, Esteban E, Dómine M, Hochmair MJ, Powell SF, Bischoff HG, Peled N, Grossi F, Jennens RR, Reck M, Hui R, Garon EB, Kurata T, Gray JE, Schwarzenberger P, Jensen E, Pietanza MC, Rodríguez-Abreu D. Pembrolizumab Plus Pemetrexed and Platinum in Nonsquamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: 5-Year Outcomes From the Phase 3 KEYNOTE-189 Study. J Clin Oncol. 2023 Apr 10;41(11):1992-1998. [CrossRef]

- Novello S, Kowalski DM, Luft A, Gümüş M, Vicente D, Mazières J, Rodríguez-Cid J, Tafreshi A, Cheng Y, Lee KH, Golf A, Sugawara S, Robinson AG, Halmos B, Jensen E, Schwarzenberger P, Pietanza MC, Paz-Ares L. Pembrolizumab Plus Chemotherapy in Squamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: 5-Year Update of the Phase III KEYNOTE-407 Study. J Clin Oncol. 2023 Apr 10;41(11):1999-2006. [CrossRef]

- Rischin D, Porceddu S, Day F, Brungs DP, Christie H, Jackson JE, Stein BN, Su YB, Ladwa R, Adams G, Bowyer SE, Otty Z, Yamazaki N, Bossi P, Challapalli A, Hauschild A, Lim AM, Patel VA, Walker JL, De Liz Vassen Schurmann M, Queirolo P, Cañueto J, Ferreira da Silva FA, Stratigos A, Guminski A, Lin C, Damian F, Flatz L, Taylor AE, Carr DR, Harris S, Kirtbaya D, Quereux G, Rutkowski P, Basset-Seguin N, Khushalani NI, Robert C, Ju H, Joseph C, Bansal S, Chen CI, Seebach F, Yoo SY, Lowy I, Goncalves P, Fury MG; C-POST Trial Investigators. Adjuvant Cemiplimab or Placebo in High-Risk Cutaneous Squamous-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2025 Aug 21;393(8):774-785. [CrossRef]

- Gross ND, Miller DM, Khushalani NI, Divi V, Ruiz ES, Lipson EJ, Meier F, Su YB, Swiecicki PL, Atlas J, Geiger JL, Hauschild A, Choe JH, Hughes BGM, Schadendorf D, Patel VA, Homsi J, Taube JM, Lim AM, Ferrarotto R, Kaufman HL, Seebach F, Lowy I, Yoo SY, Mathias M, Fenech K, Han H, Fury MG, Rischin D. Neoadjuvant Cemiplimab for Stage II to IV Cutaneous Squamous-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2022 Oct 27;387(17):1557-1568. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).