Submitted:

13 December 2025

Posted:

15 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. From Clinical Trials to FDA Approval

2.1. Aducanumab

2.1.1. Phase I Clinical Trials

2.1.2. Phase II Clinical Trials

2.1.3. Phase III Clinical Trials

2.2. Lecanemab

2.2.1. Phase I Clinical Trials

2.2.2. Phase II Clinical Trials

2.2.3. Phase III Clinical Trials

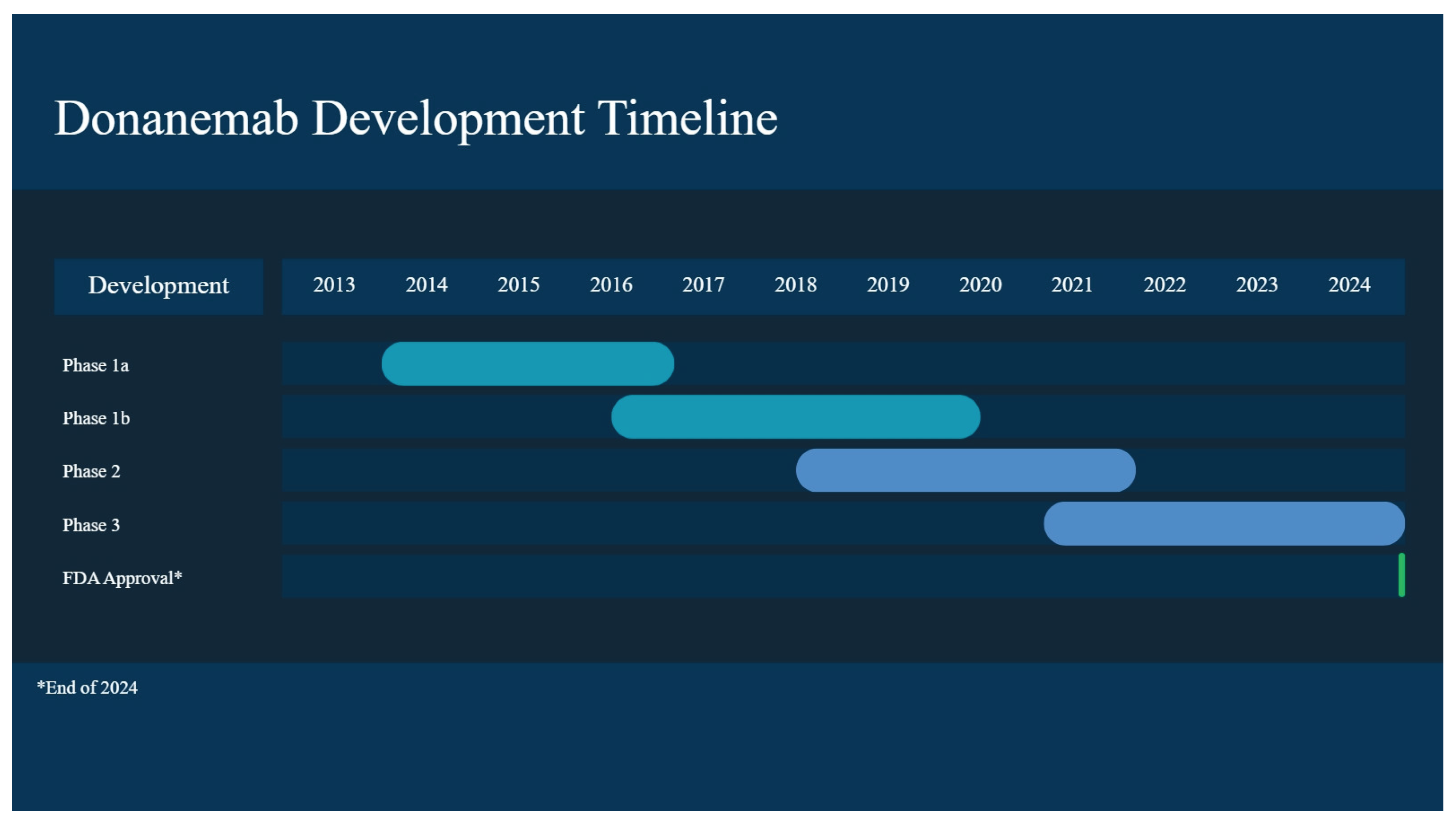

2.3. Donanemab

2.3.1. Phase I Clinical Trials

2.3.2. Phase II Clinical Trials

2.3.3. Phase III Clinical Trials

3. Discussion and Conclusions

3.1. mAb Treatments and APOE4 Carriers

3.2. Overview and Moving Forward

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alzheimer’s Disease Fact Sheet. National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Aging, 2023. Available online: https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/alzheimers-and-dementia/alzheimers-disease-fact-sheet.

- Keene, D.C.; Montine, T.J. Epidemiology, pathology, and pathogenesis of Alzheimer disease. UpToDate; Connor, R.F., Ed.; Wolters Kluwer, 2025; Available online: https://www-uptodate-com.nuigalway.idm.oclc.org/contents/epidemiology-pathology-and-pathogenesis-of-alzheimer-disease.

- Raulin, A.-C.; Martens, Y. A.; Bu, G. Lipoproteins in the Central Nervous System: From Biology to Pathobiology. Annual Review of Biochemistry 2022, 91, 731–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govindpani, K.; McNamara, L.G.; Smith, N.R.; Vinnakota, C.; Waldvogel, H.J.; Faull, R.L.; Kwakowsky, A. Vascular Dysfunction in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Prelude to the Pathological Process or a Consequence of It? J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Bernardo, A.; Walker, D.; Kanegawa, T.; Mahley, R. W.; Huang, Y. Profile and Regulation of Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) Expression in the CNS in Mice with Targeting of Green Fluorescent Protein Gene to the ApoE Locus. The Journal of Neuroscience 2006, 26(19), 4985–4994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A.; Alkon, D. L.; Nelson, T. J. Apolipoprotein E3 (ApoE3) but Not ApoE4 Protects against Synaptic Loss through Increased Expression of Protein Kinase Cϵ. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2012, 287(19), 15947–15958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirai, Y.; Adachi, N.; Saito, N. Protein kinase Cε: function in neurons. The FEBS Journal 2008, 275(16), 3988–3994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Guo, Z.-d.; He, Z.-z.; Wang, Z.-y.; Sun, X.-c. Apolipoprotein E Affects In Vitro Axonal Growth and Regeneration via the MAPK Signaling Pathway. Cell Transplantation 2019, 28(6), 691–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-C.; Kanekiyo, T.; Xu, H.; Bu, G. Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: risk, mechanisms and therapy. Nature Reviews Neurology 2013, 9(2), 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira de Oliveira, F.; Chen, E. S.; Cardoso Smith, M. A.; Ferreira Bertolucci, P. H. P3-292: Effects of Apoe Gene Haplotypes and Measures of Cardiovascular Risk Over Cognitive and Functional Decline in one Year in Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease Dementia. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2016, 12(7S_Part_19), P952–P952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahley, R. W.; Weisgraber, K. H.; Huang, Y. Apolipoprotein E4: A causative factor and therapeutic target in neuropathology, including Alzheimer’s disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2006, 103(15), 5644–5651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, G.; Zhuo, D.; Han, X.; Yao, W.; Liu, C.; Liu, H.; Cao, H.; Sun, Y.; Chen, Z.; Feng, T. From degenerative disease to malignant tumors: Insight to the function of ApoE. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2023, 158, 114127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Crick, S. L.; Bu, G.; Frieden, C.; Pappu, R. V.; Lee, J.-M. Amyloid seeds formed by cellular uptake, concentration, and aggregation of the amyloid-beta peptide. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2009, 106(48), 20324–20329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpentier, M.; Robitaille, Y.; DesGroseillers, L.; Boileau, G.; Marcinkiewicz, M. Declining Expression of Neprilysin in Alzheimer Disease Vasculature: Possible Involvement in Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy. Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology 2002, 61(10), 849–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miners, J. S.; Van Helmond, Z.; Chalmers, K.; Wilcock, G.; Love, S.; Kehoe, P. G. Decreased Expression and Activity of Neprilysin in Alzheimer Disease Are Associated With Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy. Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology 2006, 65(10), 1012–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belinson, H.; Lev, D.; Masliah, E.; Michaelson, D. M. P3-291: Activation of the amyloid cascade in apoE4 transgenic mice by inhibition of neprilysin induces neurodegeneration and learning and memory deficits. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2008, 4(4S_Part_18), T607–T608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garai, K.; Verghese, P. B.; Baban, B.; Holtzman, D. M.; Frieden, C. The Binding of Apolipoprotein E to Oligomers and Fibrils of Amyloid-β Alters the Kinetics of Amyloid Aggregation. Biochemistry 2014, 53(40), 6323–6331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deane, R.; Sagare, A.; Hamm, K.; Parisi, M.; Lane, S.; Finn, M. B.; Holtzman, D. M.; Zlokovic, B. V. apoE isoform–specific disruption of amyloid β peptide clearance from mouse brain. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 2008, 118(12), 4002–4013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.; Xue, F.; Hang, W.; Wen, B.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, J.; Liu, X.; Chen, J.; Tian, Q. Neuron-Specific Apolipoprotein E4 (1-272) Fragment Induces Tau Hyperphosphorylation and Axonopathy via Triggering Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2019, 71(2), 597–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, K. E.; Wilcock, D. M. Three major effects of APOEε4 on Aβ immunotherapy induced ARIA. In Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience; Mini Review, 2024; pp. 16–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rannikmäe, K.; Kalaria, R. N.; Greenberg, S. M.; Chui, H. C.; Schmitt, F. A.; Samarasekera, N.; Al-Shahi Salman, R.; Sudlow, C. L. M. APOE associations with severe CAA-associated vasculopathic changes: collaborative meta-analysis. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 2014, 85(3), 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, M. Lecanemab therapy and APOE genotype. Medical Genetics Summaries - NCBI Bookshelf, 2024. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK605938/.

- Press, D.; Buss, S.S. Treatment of Alzheimer disease. In UpTpDate; Connor, R.F., Ed.; Wolters Kluwer, 2025; Available online: https://www-uptodate-com.nuigalway.idm.oclc.org/contents/treatment-of-alzheimer-disease?search=Treatment%20of%20Alzheimer%20disease&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H485519119.

- Cummings, J.; Osse, A. M. L.; Cammann, D.; Powell, J.; Chen, J. Anti-Amyloid Monoclonal Antibodies for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. BioDrugs 2024, 38(1), 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alawode, D. O. T.; Heslegrave, A. J.; Fox, N. C.; Zetterberg, H. Donanemab removes Alzheimer’s plaques: what is special about its target? The Lancet Healthy Longevity 2021, 2(7), e395–e396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrero, J.; Williams, L.; Stella, H.; Leitermann, K.; Mikulskis, A.; O’Gorman, J.; Sevigny, J. First-in-human, double-blind, placebo-controlled, single-dose escalation study of aducanumab (BIIB037) in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 2016, 2(3), 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevigny, J.; Chiao, P.; Bussière, T.; Weinreb, P. H.; Williams, L.; Maier, M.; Dunstan, R.; Salloway, S.; Chen, T.; Ling, Y.; et al. The antibody aducanumab reduces Aβ plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 2016, 537(7618), 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budd Haeberlein, S.; Aisen, P. S.; Barkhof, F.; Chalkias, S.; Chen, T.; Cohen, S.; Dent, G.; Hansson, O.; Harrison, K.; von Hehn, C.; et al. Two Randomized Phase 3 Studies of Aducanumab in Early Alzheimer’s Disease. The Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease 2022, 9(2), 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salloway, S.; Chalkias, S.; Barkhof, F.; Burkett, P.; Barakos, J.; Purcell, D.; Suhy, J.; Forrestal, F.; Tian, Y.; Umans, K.; et al. Amyloid-Related Imaging Abnormalities in 2 Phase 3 Studies Evaluating Aducanumab in Patients With Early Alzheimer Disease. JAMA Neurology 2022, 79(1), 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herring, W. L.; Gould, I. G.; Fillit, H.; Lindgren, P.; Forrestal, F.; Thompson, R.; Pemberton-Ross, P. Predicted Lifetime Health Outcomes for Aducanumab in Patients with Early Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology and Therapy 2021, 10(2), 919–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J.; Rabinovici, G. D.; Atri, A.; Aisen, P.; Apostolova, L. G.; Hendrix, S.; Sabbagh, M.; Selkoe, D.; Weiner, M.; Salloway, S. Aducanumab: Appropriate Use Recommendations Update. J Prev Alzheimers Dis 2022, 9(2), 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowman Rogers, M. Adieu to Aduhelm: Biogen Stops Marketing Antibody. Alzforum. 1 February 2024. Available online: https://www.alzforum.org/news/community-news/adieu-aduhelm-biogen-stops-marketing-antibody#top (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Logovinsky, V.; Satlin, A.; Lai, R.; Swanson, C.; Kaplow, J.; Osswald, G.; Basun, H.; Lannfelt, L. Safety and tolerability of BAN2401 - a clinical study in Alzheimer’s disease with a protofibril selective Aβ antibody. Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy 2016, 8(1), 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, C. J.; Zhang, Y.; Dhadda, S.; Wang, J.; Kaplow, J.; Lai, R. Y. K.; Lannfelt, L.; Bradley, H.; Rabe, M.; Koyama, A.; et al. A randomized, double-blind, phase 2b proof-of-concept clinical trial in early Alzheimer’s disease with lecanemab, an anti-Aβ protofibril antibody. Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy 2021, 13(1), 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCT05269394, C. T.

- Dyck, C. H. v.; Swanson, C. J.; Aisen, P.; Bateman, R. J.; Chen, C.; Gee, M.; Kanekiyo, M.; Li, D.; Reyderman, L.; Cohen, S.; et al. Lecanemab in Early Alzheimer’s Disease. New England Journal of Medicine 2023, 388(1), 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafii, M. S.; Sperling, R. A.; Donohue, M. C.; Zhou, J.; Roberts, C.; Irizarry, M. C.; Dhadda, S.; Sethuraman, G.; Kramer, L. D.; Swanson, C. J.; et al. The AHEAD 3-45 Study: Design of a prevention trial for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 2023, 19(4), 1227–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, S. L.; Willis, B. A.; Hawdon, A.; Natanegara, F.; Chua, L.; Foster, J.; Shcherbinin, S.; Ardayfio, P.; Sims, J. R. Donanemab (LY3002813) dose-escalation study in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions 2021, 7(1), e12112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, S. L.; Duggan Evans, C.; Shcherbinin, S.; Cheng, Y. J.; Willis, B. A.; Gueorguieva, I.; Lo, A. C.; Fleisher, A. S.; Dage, J. L.; Ardayfio, P.; et al. Donanemab (LY3002813) Phase 1b Study in Alzheimer’s Disease: Rapid and Sustained Reduction of Brain Amyloid Measured by Florbetapir F18 Imaging. J Prev Alzheimers Dis 2021, 8(4), 414–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mintun, M. A.; Lo, A. C.; Duggan Evans, C.; Wessels, A. M.; Ardayfio, P. A.; Andersen, S. W.; Shcherbinin, S.; Sparks, J.; Sims, J. R.; Brys, M.; et al. Donanemab in Early Alzheimer’s Disease. N Engl J Med 2021, 384(18), 1691–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilly’s Donanemab Significantly Slowed Cognitive and Functional Decline in Phase 3 Study of Early Alzheimer’s Disease. Lilly Investors, 2023 . Available online: https://investor.lilly.com/news-releases/news-release-details/lillys-donanemab-significantly-slowed-cognitive-and-functional.

- Sims, J. R.; Zimmer, J. A.; Evans, C. D.; Lu, M.; Ardayfio, P.; Sparks, J.; Wessels, A. M.; Shcherbinin, S.; Wang, H.; Monkul Nery, E. S.; et al. Donanemab in Early Symptomatic Alzheimer Disease: The TRAILBLAZER-ALZ 2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2023, 330(6), 512–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salloway, S.; Lee, E.; Papka, M.; Pain, A.; Oru, E.; Ferguson, M. B.; Wang, H.; Case, M.; Lu, M.; Collins, E. C.; et al. TRAILBLAZER-ALZ 4: Topline Study Results Directly Comparing Donanemab to Aducanumab on Amyloid Lowering in Early, Symptomatic Alzheimer’s Disease. (2056-4724 (Electronic)). From 2023 Jul.

- A Study of Different Donanemab (LY3002813) Dosing Regimens in Adults With Early Alzheimer’s Disease (TRAILBLAZER-ALZ 6). National Library of Medicine (U.S.), 2025. Identifier NCT05738486. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05738486.

- A Study of Donanemab (LY3002813) in Participants With Early Symptomatic Alzheimer’s Disease (TRAILBLAZER-ALZ 5). National Library of Medicine (U.S.), 2025. Identifier NCT05508789. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05508789.

- Filippi, M.; Cecchetti, G.; Spinelli, E. G.; Vezzulli, P.; Falini, A.; Agosta, F. Amyloid-Related Imaging Abnormalities and β-Amyloid-Targeting Antibodies: A Systematic Review. JAMA Neurol 2022, 79(3), 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honig, L. S.; Barakos, J.; Dhadda, S.; Kanekiyo, M.; Reyderman, L.; Irizarry, M.; Kramer, L. D.; Swanson, C. J.; Sabbagh, M. ARIA in patients treated with lecanemab (BAN2401) in a phase 2 study in early Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 2023, 9(1), e12377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketter, N.; Brashear, H. R.; Bogert, J.; Di, J.; Miaux, Y.; Gass, A.; Purcell, D. D.; Barkhof, F.; Arrighi, H. M. Central Review of Amyloid-Related Imaging Abnormalities in Two Phase III Clinical Trials of Bapineuzumab in Mild-To-Moderate Alzheimer’s Disease Patients. J Alzheimers Dis 2017, 57(2), 557–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.-C.; Huang, Y.-C.; Liu, H.-C. Effect of Apolipoprotein E ɛ4 Carrier Status on Cognitive Response to Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors in Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders 2018, 45(5-6), 335–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokgöz, S.; Claassen, J. Exercise as Potential Therapeutic Target to Modulate Alzheimer’s Disease Pathology in APOE ε4 Carriers: A Systematic Review. Cardiol Ther 2021, 10(1), 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishai, L.; Ori, L.; Daniel, M. M. An Anti-apoE4 Specific Monoclonal Antibody Counteracts the Pathological Effects of apoE4 In Vivo. Current Alzheimer Research 2016, 13(8), 918–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Shen, X.; Zhang, B.; Zhu, Z. Biologics as Therapeutical Agents Under Perspective Clinical Studies for Alzheimer’s Disease. Molecules 2025, 30, 3479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Phase III, Multicenter, Randomized, Parallel-Group, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Gantenerumab in Participants at Risk for or at the Earliest Stages of Alzheimer’s Disease. National Library of Medicine (U.S.), 2023. Identifier NCT05256134. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05256134.

- A Phase 2 Double-Blinded Study Evaluating the Safety, Tolerability and Pharmacokinetics/Pharmacodynamics of PF-04360356 in Mild to Moderate Alzheimer’s Disease Patients. National Library of Medicine (U.S.), 2011. Identifier NCT00945672. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT00945672.

- Rafii, M. S.; Aisen, P. S. Amyloid-lowering immunotherapies for Alzheimer disease: current status and future directions. Nature Reviews Neurology 2025, 21(9), 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) units. OECD Data. 2023. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/data/indicators/magnetic-resonance-imaging-mri-units.html.

- Sato, K.; Niimi, Y.; Ihara, R.; Iwata, A.; Nemoto, K.; Arai, T.; Higashi, S.; Igarashi, A.; Kasuga, K.; Akiyama, H.; et al. Real-world lecanemab adoption in Japan 1 year after launch: Insights from 311 specialists on infrastructure and reimbursement barriers. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2025, 21(10), e70652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlavka, J. P.; Mattke, S.; Liu, J. L. Assessing the Preparedness of the Health Care System Infrastructure in Six European Countries for an Alzheimer’s Treatment From NLM. Rand Health Q 2019, 8(3), 2. [Google Scholar]

- FDA Accepts LEQEMBI® (lecanemab-irmb) Biologics License Application for Subcutaneous Maintenance Dosing for the Treatment of Early Alzheimer’s Disease. Biogen Investors, 2025. Available online: https://investors.biogen.com/news-releases/news-release-details/fda-accepts-leqembir-lecanemab-irmb-biologics-license.

- Willis, B. A.; Penner, N.; Rawal, S.; Aluri, J.; Reyderman, L. Subcutaneous (SC) lecanemab is predicted to achieve comparable efficacy and improved safety compared to lecanemab IV in early Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2023, 19(S24), e082852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xiang, P.; Duro-Castano, A.; Cai, H.; Guo, B.; Liu, X.; Yu, Y.; Lui, S.; Luo, K.; Ke, B.; et al. Rapid amyloid-β clearance and cognitive recovery through multivalent modulation of blood–brain barrier transport. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2025, 10(1), 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimm, H. P.; Schumacher, V.; Schäfer, M.; Imhof-Jung, S.; Freskgård, P.-O.; Brady, K.; Hofmann, C.; Rüger, P.; Schlothauer, T.; Göpfert, U.; et al. Delivery of the Brainshuttle™ amyloid-beta antibody fusion trontinemab to non-human primate brain and projected efficacious dose regimens in humans. mAbs 2023, 15(1), 2261509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, E. L.; Weinberg, M. S.; Arnold, S. E. Cost-effectiveness of Aducanumab and Donanemab for Early Alzheimer Disease in the US. JAMA Neurology 2022, 79(5), 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H. V.; Mital, S.; Knopman, D. S.; Alexander, G. C. Cost-Effectiveness of Lecanemab for Individuals With Early-Stage Alzheimer Disease. Neurology 2024, 102(7), e209218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J.; Apostolova, L.; Rabinovici, G. D.; Atri, A.; Aisen, P.; Greenberg, S.; Hendrix, S.; Selkoe, D.; Weiner, M.; Petersen, R. C.; et al. Lecanemab: Appropriate Use Recommendations. The Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease 2023, 10(3), 362–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinovici, G. D.; Selkoe, D. J.; Schindler, S. E.; Aisen, P.; Apostolova, L. G.; Atri, A.; Greenberg, S. M.; Hendrix, S. B.; Petersen, R. C.; Weiner, M.; et al. Donanemab: Appropriate use recommendations. The Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease 2025, 12(5), 100150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Drug Name | FDA Approval Date | MoA | Administration | Adverse Effects | Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aducanumab | June 2021 (accelerated) | Fully human anti-Aβ IgGI | IV, every 4 weeks at a dose of 10 mg/kg | Phase III: ARIA-E- 35.2% of patients on 10mg/kg Sx: headache, confusion, dizziness, nausea. Double the percentage of ARIA-E in apolipoprotein E ε4 carriers compared to non-carriers |

EMERGE: 22% reduction in decline in CDR-SB for high dose compared to placebo at week 78 Herring 2021: a lower lifetime probability of transitioning to institutionalization (25.2% vs. 29.4%) |

| Lecanemab | July 2023 | Humanized IgGI with high affinity to Aβ soluble protofibrils | IV, biweekly at a dose of 10 mg/kg | Clarity: Infusion-related rxn (26.4%), ARIA-E (12.6%), 32.6% in homozygotes for apoE4, 10.9% of apoE4 carriers, 5.4% of non-carriers |

Phase II: On CDR-SB, clinical decline was reduced by 26% at 10 mg/kg biweekly at 18 months Clarity: CDR-SB from baseline was 0.45 lower in those who received lecanemab, 1.21 as opposed to placebo, 1.66. |

| Donanemab | July 2024 | Humanized IgGI which binds to Aβ | IV, once monthly 10 mg/kg | Phase Ia: More than 90% of patients developed antidrug antibodies TRAILBLAZER-ALZ 2: ARIA-E and -H occurred in 24% and 31.4% of participants treated with donanemab, with 6.1% experiencing symptomatic ARIA-E Homozygous and heterozygous apoE4 carriers experienced ARIA-E at a higher frequency than noncarriers, 40.6% and 22.8% as opposed to 15.7% |

TRAILBLAZER-ALZ 2: 36% reduction in decrease in CDR-SB over 18 months |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).