3. Cumulative energy demand of cars

Before we move on to the actual assessment of the energy demand for vehicle traffic during their operational use, we will present how to use data from spritmonitor.de to create an indicator such as fuel economy.

Among the methods for assessing energy demand, and traditionally fuel consumption, of engines in long-term, natural vehicle operation, the most commonly used method to date is the “full tank” method, also known as “tank-to-tank.” However, there are two basic variations of this method: one reports fuel consumption in units of volume of fuel consumed relative to distance traveled (usually dm³ per 100 km). The other reports the distance traveled on a given volume of fuel (usually miles per gallon).

In the EU, the traditional fuel economy metric is fuel economy (FE), expressed in dm³/100 km (liters/100 km or l/100 km). Considering different drive types, this metric can also be expressed in kg/100 km (e.g., for hydrogen-powered vehicles) or kWh/100 km for electric vehicles (it is clear that after the introduction of new energy carriers to power vehicle drive systems, the fuel economy indicator has been adjusted accordingly by society as a whole).

The procedure for constructing the

FE indicator is presented here using data from spritmonitor.de. This data is the result of long-term. natural operation of a mid-size hydrogen-powered passenger car (H2EV). In the spritmonitor.de database. the vehicle was assigned the number 1195603 (just like other vehicles that are assigned specific numbers in the spritmonitor database - they have nothing to do with the vehicle’s VIN or registration number). This data is presented in

Table 1.

The data in the “Data”. “Tachostand”. “Distance” and “Menge” columns comes directly from the spritmonitor.de database. The data in the remaining columns is calculated based on data from the spritmonitor.de database.

Analyzing the presented data. it can be seen that it covers mileage ranging from 33,985 km recorded on August 15. 2020. to 44,797 km recorded on August 26. 2021. Therefore. the data covers a trip distance of 10,802 km traveled in one year. This data can undoubtedly be classified as operational data from the vehicle’s long-distance natural operation.

Analyzing the data further. the following results can be presented. By the assumptions that

Fi – i-th refueling.

tdi – mileage to Fi.

the fuel economy (

FE) can be expressed as:

The achieving results are presented in column

FE the

Table 1.

As can be seen. the data are statistical in nature. Allowing for a comprehensive statistical analysis. If all refueling are treated as one set, then the statistical analysis is obtained. Such an analysis was conducted. and the results are presented in

Table 2.

With statistical analysis data available, it is possible to present both the mean (FE(AV)) and the ranges of data variability as a function of vehicle mileage: from Mean - Standard Deviation (FE(AV-SD)) to Mean + Standard Deviation (FE(AV+SD)).

Although this data presentation seems to be common practice, it seems more interesting to present the average

FE after each refueling (from the previous refueling). Therefore, if we assume that this average is the

AFE and the number of refuelings varies from 1 to

n, then by

n refueling the average fuel economy (

AFEn) is as

Further, if it is possible to calculate

AFEi for each

i (from 1 to 64) there after each

i fueling is

AFEi. given and these values do not have to be constant – which is observed in reality. An example of the

FEi and

AFEi values calculated in the presented studies for car 1195603. is given in

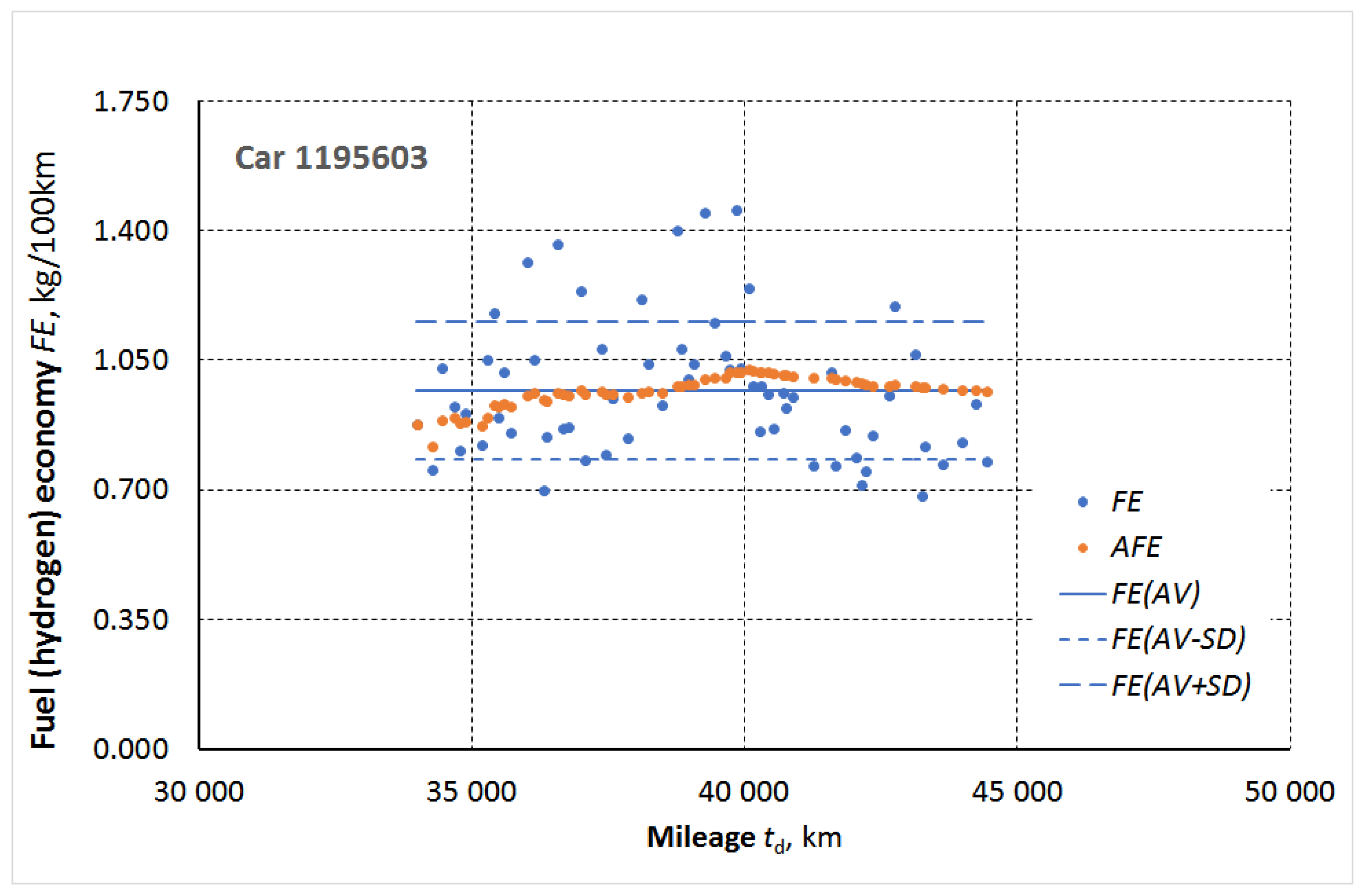

Figure 1.

Figure 1 shows the values for

i=

n= 64 from 65 refueling. As you see from

Table 1. (64 and not 65 values because by mileage of 33,995 are the fueling of 2.29 kg of H

2 noted but is not the traveled distance given).

AFE values differ from FE(AV). At the beginning of the observed course, they are lower, then stabilize, then increase, only to fall below the average again. Determining the reasons for this is beyond the scope of this article; by defining AFE, we merely emphasize that using this variable allows for a more accurate assessment of a specific vehicle’s operating process and, indirectly, its operating conditions.

Using both

FE and

AFE has one major drawback: it does not allow for the prediction of energy carrier consumption. The vehicle energy footprint does not have this disadvantage. The method for determining this footprint will be discussed in the example data from

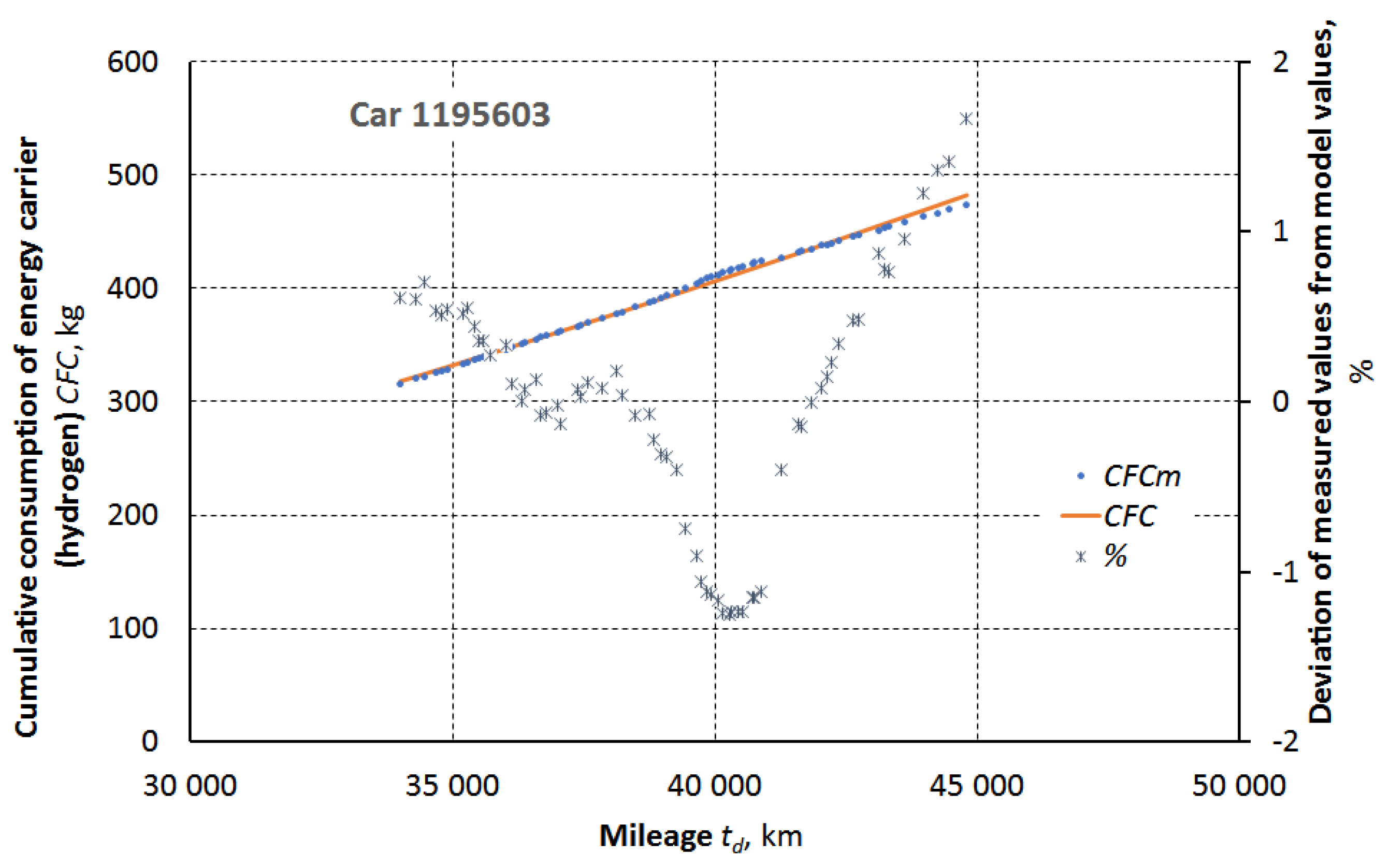

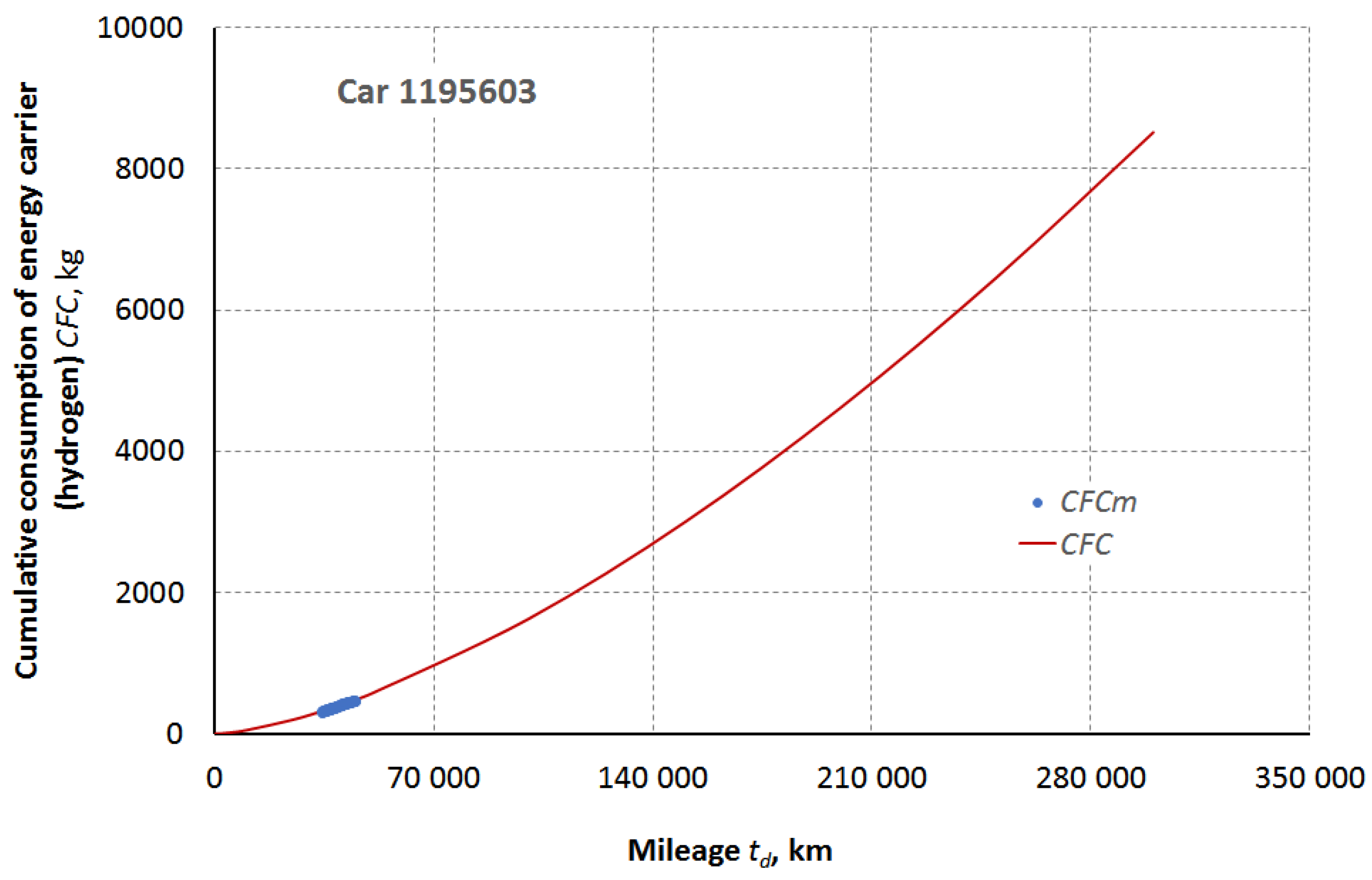

Table 1 for H2EV no. 1195603.

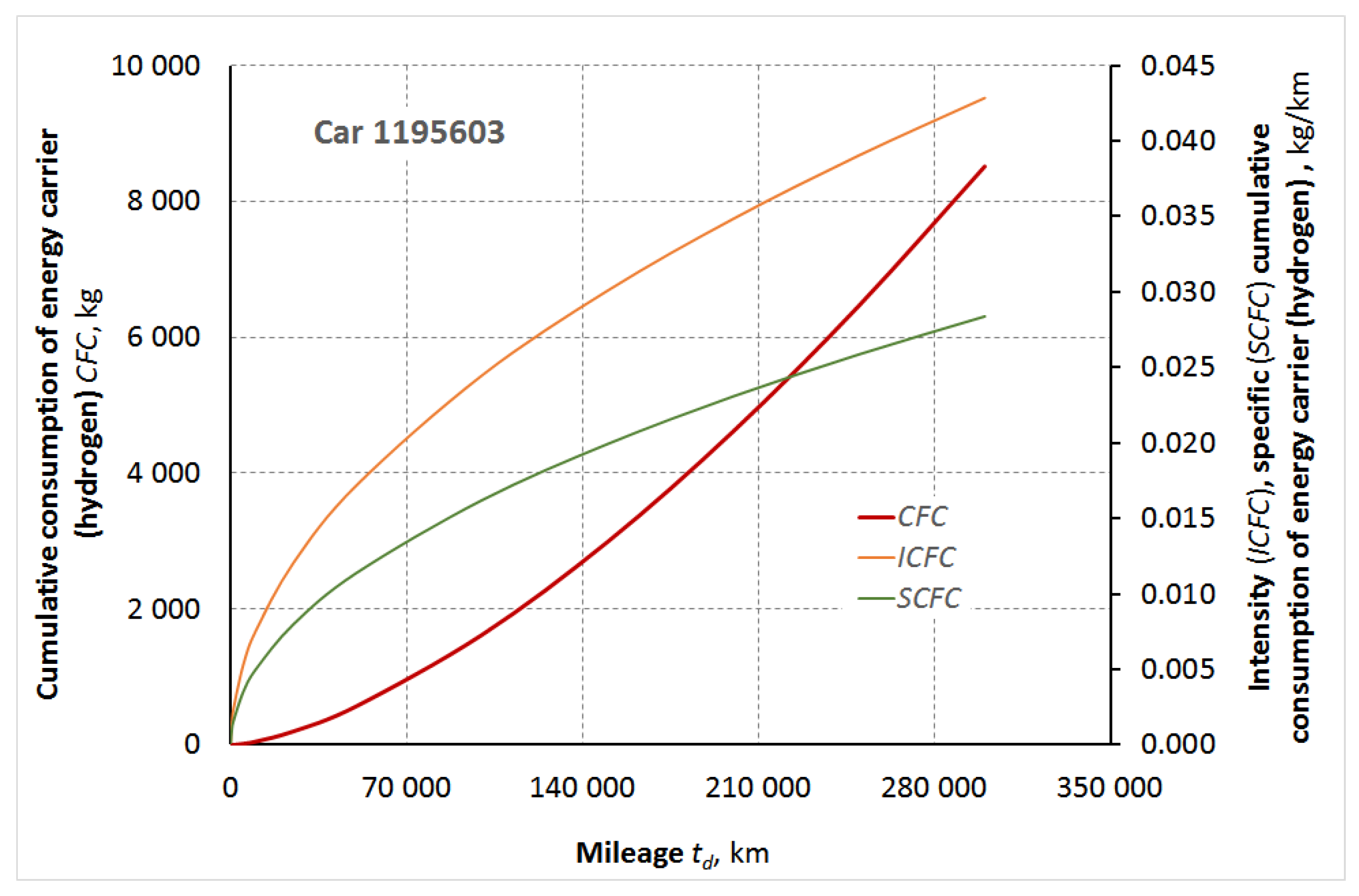

Evaluating vehicle fuel consumption (energy carrier) during long-term natural operation is crucial for understanding the impact of motorization on people and the environment, and is essential for developing and implementing sustainable transport policies. A significant contribution to this field can be made by the cumulative fuel consumption theory [

11], which offers a comprehensive framework for assessing fuel consumption during long-term vehicle operation under real-world conditions. The concept of determining a vehicle’s energy footprint, based on cumulative energy carrier consumption, provides insight into the total energy consumed throughout its entire life cycle, from production to disposal, by enabling accurate estimation of the energy demand for covering a given distance over the projected period of its operation.

5. Energy Amount for Fleet Different Power Train Vehicles

In the previous chapter, we presented the theory of cumulative energy demand (energy carrier consumption) using operational data from one of the analyzed vehicles as an example. The question arises whether, or rather how, this theory can be used to generate arguments for a discussion on future directions of automotive development. Therefore, we decided to present a developed method for generating arguments for the aforementioned discussion, but arguments based on energy issues.

For the analysis, mid-size cars with similar performance (power, acceleration, etc.) were randomly selected from the spritmonitor.de database. The selected cars were ICEVs, HEVs, BEVs, and H2EVs; four types of drive. Fifteen vehicles of each type were selected for analysis.

Therefore, the operating data of 4 x 15 = 60 cars was analyzed.

ICEVs and HEVs are vehicles powered directly by an internal combustion engine, with HEVs assisted by an electric motor located in the gearbox. HEVs are vehicles without the ability to be charged from the mains (not plug-in hybrids).

BEVs and H2EVs are essentially electric vehicles. In the BEV, the electricity is stored on board (in an electric energy battery) and then used to power the electric motors, while in the H2EV, the energy carrier is hydrogen (stored on board in hydrogen tanks). The electricity powering the electric motors is generated on board the H2EV using a fuel cell.

Fifteen items were assumed to constitute a minimum statistical sample, which also allowed for demonstrating the feasibility of conducting a broader statistical analysis of the obtained results.

As mentioned, the theory of cumulative fuel (energy carrier) consumption, presented in the previous paragraph, was used in the research.

It was assumed that for each vehicle group, the analysis results would be presented in summary tables containing:

information about the vehicles, their operational period, mileage, and the coefficients c and a of model (3), as well as the R squared coefficient for each vehicle,

simulations of energy carrier consumption up to a mileage of 300,000 km for each vehicle,

statistical analysis of energy carrier consumption for each of the analyzed vehicles after selected mileages up to 300,000 km.

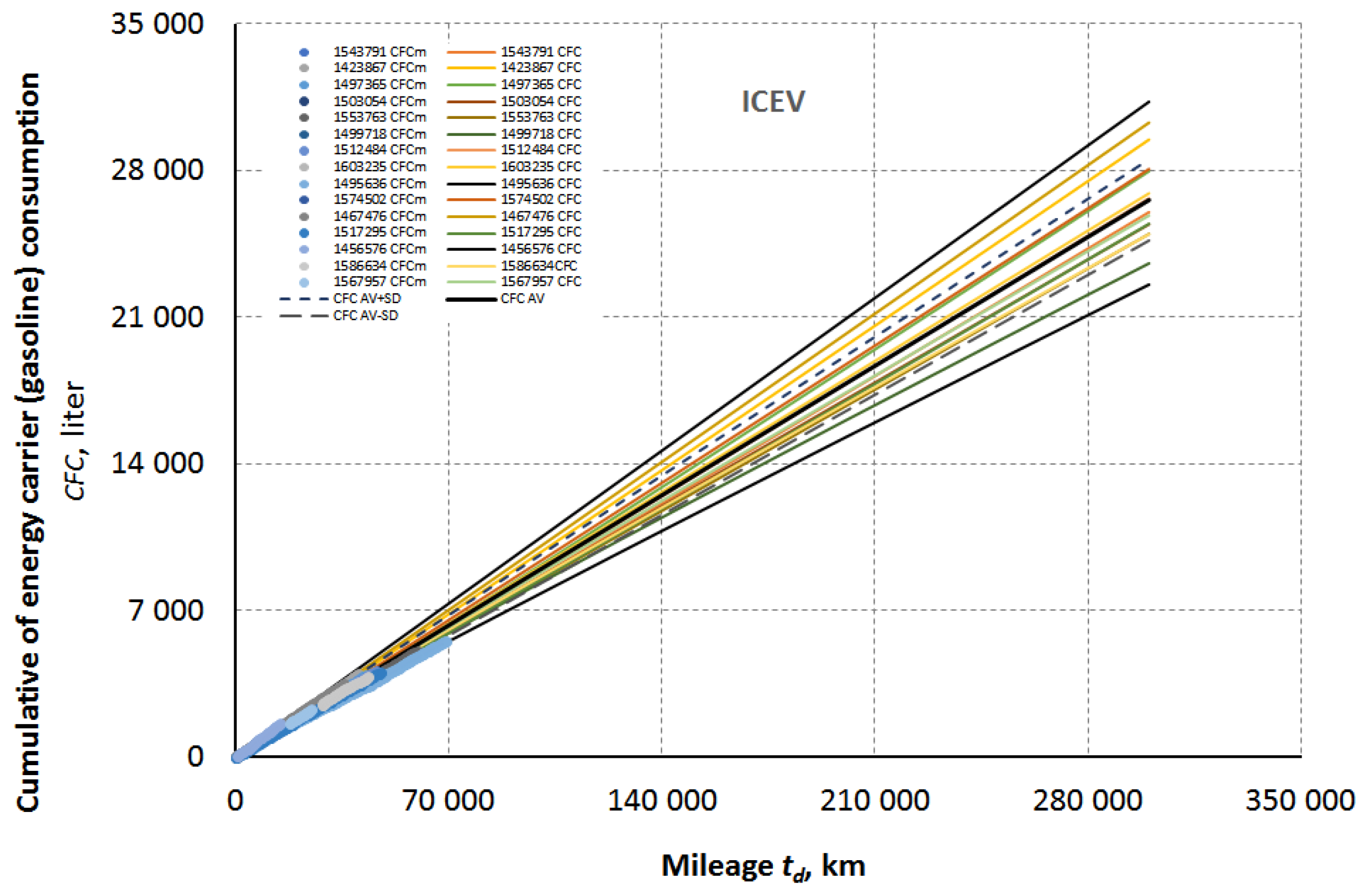

The information data of operation data of analyzed ICEV’s are given here in the

Table 4.

Table 4 shows that operational data were not always recorded from the beginning of the vehicle’s operation. This did not significantly impact the quality of model (3). The model’s (3) adequacy coefficients were never lower than R

2>0.99, which, considering the randomness of measurements of fuel amount during vehicle refueling, seems to be a very good result.

Trip distance values and period of operational data notice that all vehicles were operated over long term.

The measured cumulative fuel consumption and the one determined using model (3) with coefficients

c and

a (

Table 4) as well as the predicted fuel consumption for 300,000 kilometers of each of the analyzed ICEVs are shown in

Figure 5.

It is clear that as mileage increases, the differences in the individual cumulative fuel consumption curves also increase. These differences demonstrate the feasibility of statistically analyzing the results at the assumed mileage values.

With statistical data, it is possible to create other useful curves as a function of vehicle mileage, such as average cumulative fuel consumption (

CFC AV) and the range of variability of cumulative fuel consumption (

CFC(AV-SD) to

CFC(AV+SD)). The course of these curves for the analyzed ICEVs is also shown in

Figure 5.

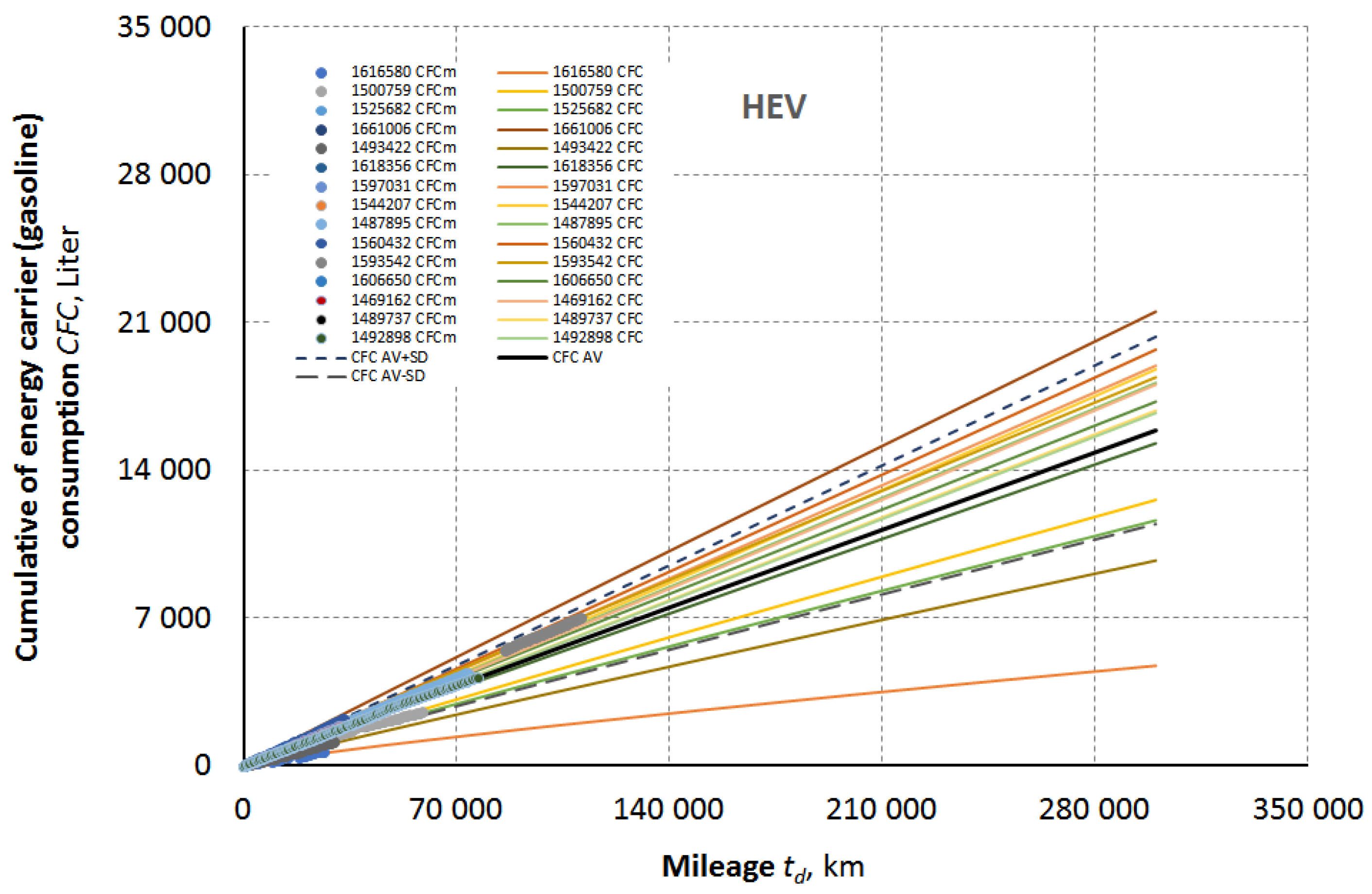

Analyses similar to those for ICEV’s are also presented here for the remaining vehicle groups, i.e., HEV’s, BEV’s, and H2EV’s. The results of these analyses are presented in the following table and pictures.

For HEV information data of operation of HEV’s are given I

Table 5.

Measurement data and simulation results with the Model (3) of the cumulative fuel (gasoline) consumption values as a function of the mileage of individual HEV’s are given in the

Figure 6.

Statistically analyzing results at the assumed mileage values for HEV’s are like follow.

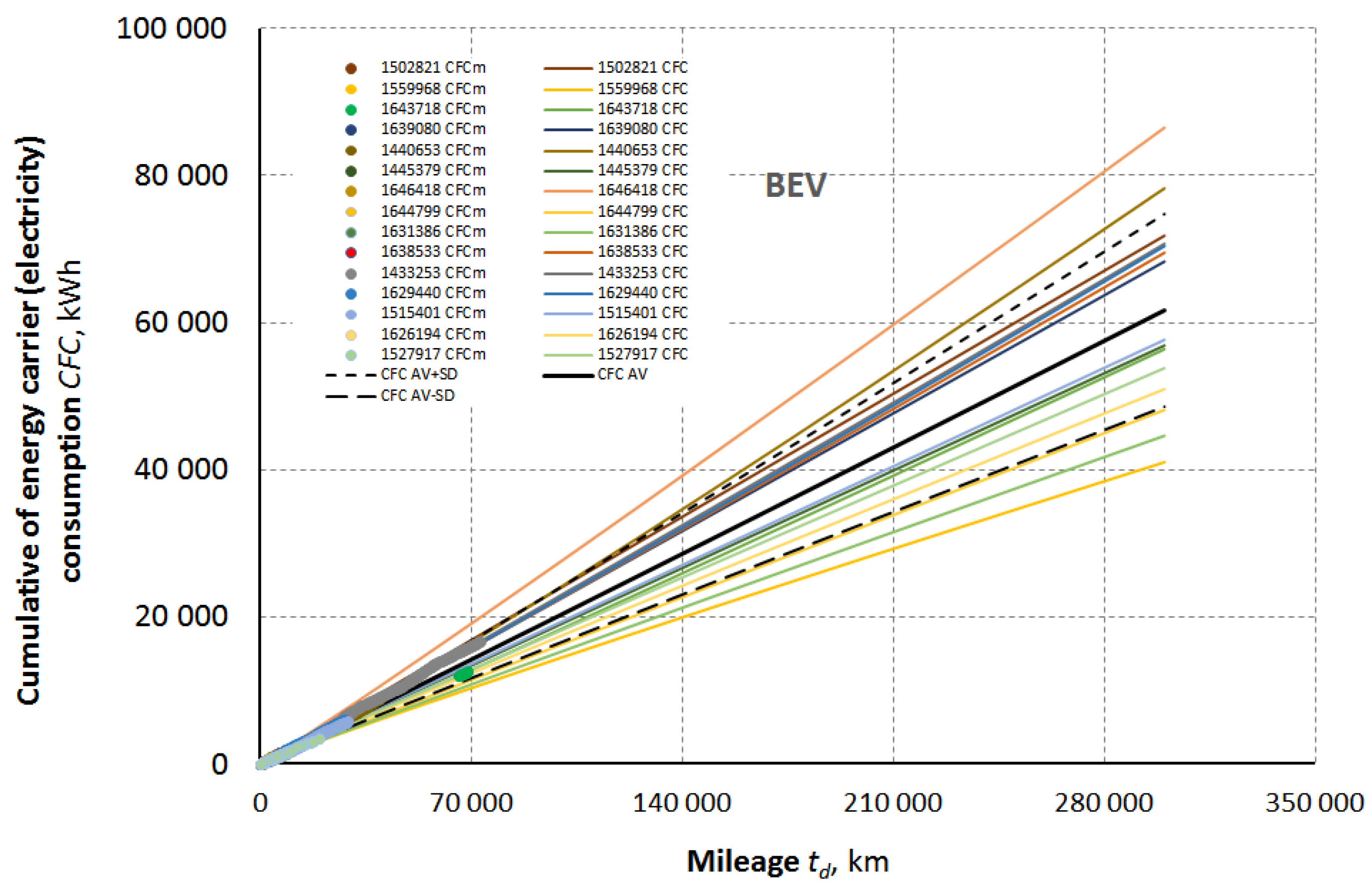

For the battery electric vehicles (BEV’s) the consideration result are as follow.

Information of operation data of analyzed BEV’s are given in the

Table 6.

The graphical presentation of the results of cumulative electricity consumption of each the analyzed BEV show the

Picture 7.

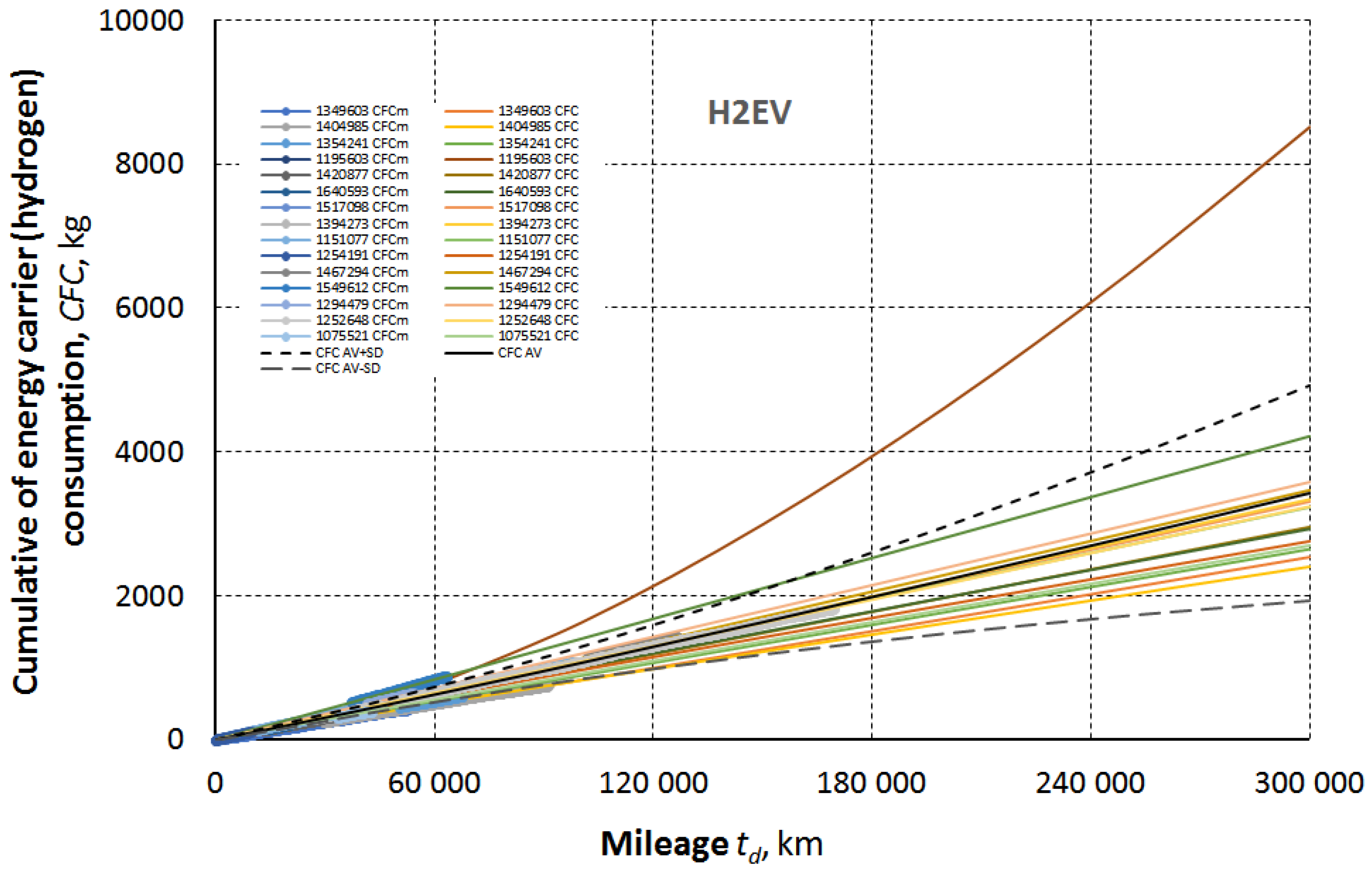

And for the analyzed hydrogen fuel cell vehicles (H2EV’s) the achieved results are as follow.

Information of operation data of analyzed H2EV’s are given in the

Table 7.

The graphical presentation of the results of cumulative electricity consumption of each the analyzed H2EV show the Picture 8.

Picture 8 shows that the cumulative hydrogen consumption (CFC) profile of one H2EV (No. 1195603) clearly differs from the others. A closer analysis indicates that this vehicle was operated primarily on country roads – 60%. Furthermore, the vehicle was operated in the city – 24%, with only 16% on highways. Analyzing this data, one can conclude that the operating conditions of this vehicle differed significantly from those of the other H2EV’s. At the same time, the correlation coefficient (R squared) of model (3) is 0.996066, which is relatively high. The “anomaly” in the cumulative fuel consumption profile was the reason why the data from this vehicle were selected to present the procedure for obtaining the coefficients of model (3).

If one element from the set of statistical sample elements differs from the others, then, in accordance with statistical analysis practice, such an element should not be taken into account, otherwise it may “falsify” the analysis results. This was the case here. However, the data for vehicle 1195606 were included in the analysis because the reason this vehicle’s data differs from the data of the other vehicles is not due to measurement errors (R2 > 0.99), but due to different operating conditions. Furthermore, this paper presents a method based on actual operating data, not specific conclusions for application under defined conditions.

With the coefficients c and a, i.e., practically model (3), and consequently also models (4) and (5), determined based on data from long-term operation of each of the analyzed vehicles, and taking into account the very high values of the correlation coefficient (R-squared), it is possible to forecast the energy carrier consumption of each vehicle up to selected mileage (e.g., as here, 300,000 km). Such simulations were conducted, and their results are presented in the figures above, relating to groups of vehicles with defined drive systems (15 vehicles in each of the 4 drive groups). For each group, there is a scatter of consumption values after each assumed mileage. Further analysis allows for the determination of statistical data regarding these value scatters, i.e., the determination of means, standard deviations, etc., and, for example, the mean 100CFC values. Selected results from this analysis are presented in

Table 8.

It’s worth noting that to this point present is a complete analysis of fuel consumption versus mileage for vehicles with specific drive types. However, this publication does not present a method for further analysis of these results or the results of that analysis. A separate publication on this topic is currently being prepared. This publication focuses solely on presenting average energy carrier consumption values and the conclusions derived from them.

But it can ask the general question of how much energy is required to drive vehicles with different types of powertrains over a given distance under long-term, natural operating conditions. Another question might be, for example, whether there is a reliable way to compare different types of vehicle drives, especially in terms of energy efficiency.

It seems that the answer to the first question can be obtained by analyzing, among other things, the SCFC relationship (5). Table shows the 100SCFC values as a function of vehicle mileage for each vehicle groups.

The mileage presented is rather unexpected. It results in a completely different character of the curves for combustion engine-powered vehicles (both ICEV and HEV) and for electric motor-powered vehicles (BEV or H2EV).

It is standard practice to assume that fuel economy (FE) values, and especially averaged fuel economy (AFE), increase with increasing mileage for combustion engine-powered vehicles. This is due, for example, to the degree of engine degradation. In this case, however, with increasing mileage, specific cumulative fuel consumption decreases. This decrease is not significant – it is worth noting the values presented on the vertical axes.

It seems important, however, that

SCFC is not a constant value as a function of vehicle mileage. Therefore, values appropriate for the maximum mileage analyzed for the vehicles were adopted for further analysis. The 100

SCFC results for the 300,000 km mileage of the individual vehicle groups are presented in

Table 9.

Row 1 of the

Table 9. shows the

SCFC values multiplied by 100. It seems that such a presentation of

SCFC values corresponds to the current “habits” in assessing the fuel consumption of vehicles (

FE and

AFE) in their natural long-term operation. It was assumed that each vehicle’s life cycle mileage was at least 300,000 km, which is typical for European passenger cars (considering that in some European countries, cars are used for more than a dozen years - Eurostat). Energy consumption in normal operation can therefore be extrapolated to total energy consumption over the assumed period of use.

The analysis of energy consumption employs a well-to-wheel (WTW) framework, which divides the energy chain into two components:

Well-to-Tank (WTT): the energy required to extract, refine, produce, and deliver usable energy carrier (fuel or electricity) to the vehicle energy storage system (tank or battery).

Tank-to-Wheel (TTW): the energy consumed by a vehicle in motion, determined by analyzing data from the long-term operation of random vehicles of a given brand and type (data treated as statistical data).

The system boundary explicitly includes:

Electricity consumption for “refining” and distributing gasoline (ICEV, HEV);

Electricity for hydrogen generation (electrolysis), compression, and dispensing (H2EV);

Electricity generation and grid losses for BEV charging;

It excludes:

Vehicle manufacturing and recycling;

Maintenance energy inputs;

Energy use in building infrastructure (e.g., refineries, charging stations, hydrogen pipelines).

This boundary ensures comparability by focusing solely on operational energy carriers consumption, consistent (or similar) with EU Well-to-Wheels methodology [

26] .

To ensure consistency across technologies, all energy flows are expressed in three metrics:

Fuel consumption (L/100 km) – standard for ICEV’s and HEV’s;

Energy consumption (kWh/100 km) – for direct or indirect electricity use (BEV’s, H2EV);

Primary energy (MJ/100km) – to allow cross-comparison between chemical and electrical energy.

Conversion factors used in this study are summarized below (

Table 10):

As mentioned above, there is a need for a two-stage energy input: generating energy carriers (WTT stage) and energy for driving the vehicle along the planned route (TTW stage). TTW energy typically comes from commercial installations (e.g., power plants or combined heat and power plants). These installations utilize both: renewable resources (photovoltaics or wind farms) and non-renewable resources (e.g., hard coal, lignite, also petroleum derivatives in combined heat and power plants operating in refineries, etc.). The type of commercial installation used to generate energy and the type of resources used in the TTW stage naturally vary from country to country, for example, within the EU. The proportions of resource use (non-renewable vs. renewable) also vary from country to country.

For this reason, this paper proposes to present only a general method for determining energy demand for a WTW. At the WTT stage, assume that electricity comes exclusively from natural gas-fired installations. The properties (efficiency, emissions) of such installations generally fall between those of installations powered by non-renewable and renewable fuels.

Since only BEVs use electricity at both the WTT and TTW stages, it can be assumed that it comes entirely from natural gas-fired installations. Therefore, it seems appropriate to also conduct an estimate of the electricity required for the WTT and TTW stages from these types of natural gas-fired installations when using ICEVs, HEVs, and H2EVs.

The assumptions and results of further analyses are as follows.

Four representative powertrain types are considered:

a) Internal Combustion Engine Vehicle (ICEV)

Engine efficiency (TTW): 22–25%.

Average fuel (gasoline) consumption on mileage of 300,000km: 8.860 L/100 km.

Indirect energy consumption (for extraction, transport and refining of crude oil, gasoline production and distribution) is equivalent to the energy content of 0.500 liter of gasoline:

0.500L×31.700 MJ/L= 15,850MJ/L. Assuming by fuel economy of 8.860 L/100 km, indirect energy consumption is therefore

WTT = 8.860 L/100 km ×15.850MJ/L = 140.430MJ/100 km.

Direct chemical energy consumption by car driving is:

TTW = 8.860L/100km×31.700MJ/L=280.860MJ/100 km.

Total energy consumption = indirect energy consumption (used achieving of the gasoline) + direct energy consumption (from gasoline used by car driving)

WTW = 140.430MJ/100 km + 280.860MJ/100km = 421.290MJ/100 km.

From this amount of energy (chemical) it is possible to generate electricity, in a power plant, with an average efficiency of 0.400. Assuming that the loss of electricity transmitted from the power plant to the charging station is 8%, the amount of electricity that can be hypothetical collected from the charging station:

WTWe(ICEV) = (0.400×421.290MJ/100 km/3.600)/0.920 = 46,810 kWh/100km /0.920 = 50.880 kWh/100km

WTWe(ICEV)≈ 51 kWh/100km

b) Hybrid Internal Combustion Engine Vehicle (HEV)

Powertrain efficiency (TTW): 30–35%.

Average fuel (gasoline) consumption on mileage of 300,000km: 5.269 L/100 km.

Producing the equivalent of electricity and hypothetically using that electricity to power a car is the same process as for pure internal combustion engine vehicles.

Indirect energy for achieving the gasoline:

WTT = 5.269L/100km×0.500×31.700MJ/L=83.514MJ/100km.

Direct energy for using (energy content in gasoline):

TTW = 5.269L/100km×31.700MJ/L=167.027MJ/100 km.

WTW (chemical energy) of HEV = 83.514MJ/100 km + 167.027MJ/100 km ≈250.541MJ/100km.

Hypothetically production of electricity in power plant and sending this electrify to charging station:

WTWe(HEV) = (0.400×250.541MJ/100km/3.600)/0.920 = 27.838 kWh/100km/0.920 = 30.259 kWh/100km

WTWe(HEV)≈ 30 kWh/100km

c) Battery Electric Vehicle (BEV)

Direct electricity use by mileage of 300,000 km: 20.475 kWh/100 km (electricity from charging station to driving 100 km) =TTWe

Indirect electricity (electricity lost as a result of energy being transferred from the power plant to the charging station). Assuming that the grid efficiency from power plant to the charging station is 0.920,

WTTe = 20.475 kWh/100 km×0.080 = 1,638 kWh/100 km

Required electricity generation for charging station

WTWe = WTTe + TTWe = 20.475 kWh/100 km + 1,638 kWh/100 km = 22.255 kWh/100km

WTWe(BEV’s)≈ 22 kWh/100 km.

d) Hydrogen Fuel Cell Electric Vehicle (H2EV)

Average hydrogen consumption on mileage of 300,000 km: 1.087 kg/100 km

Hydrogen production.

Due to the fact that water electrolysis efficiency: 70%, compression/dispensing of hydrogen efficiency: 90% and LHV of hydrogen is 120.000MJ/kg, the production of 1.000 kg of hydrogen requires the input of primary energy 120.000 MJ/kg/(0,700×0.900) = 190.476 MJ/kg

Indirect energy need:

WTT = 1.087 kg/100km×190.476 MJ/kg= 207.047 MJ/100km

Direct energy need:

TTW = 1.087 kg/100km×120.000 MJ/kg = 130.440 MJ/100km

The total energy demand is therefore:

WTW = 207.047 MJ/100km + 130.440 MJ/100km = 337.478 MJ/100km

Generating electricity from this amount of (chemical) energy will reach the value:

WTWe = 0.400 × 337.478 MJ/100km/3.600 = 37.499 kWh/100km

The hypothetical assumption is that electricity must be delivered to the charging station but there are losses in the transmission network equal to 8% and the final result is:

WTWe = 37.499 kWh/100km/0.920 = 40.759 kWh/100km

WTWe(H2EV)≈ 41 kWh/100km

The data presented show that obtaining hydrogen as an energy carrier is more energy-intensive than using it to power a vehicle.

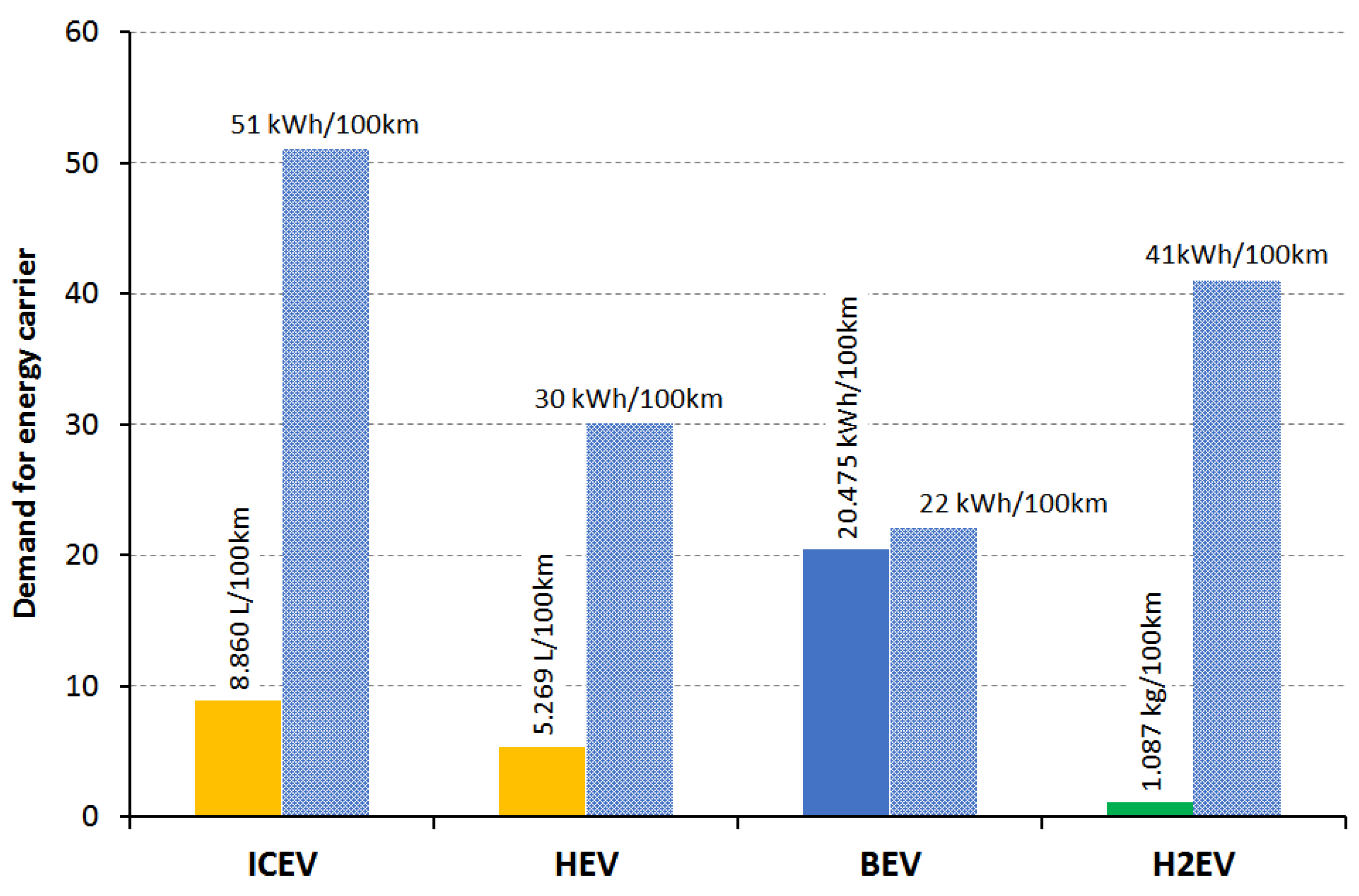

Assuming that the travel distance is 100 km, then over a distance of 300,000 km, a hypothetical comparison of the average electricity demand of the analyzed drive types can be presented, as follows:

a) ICEV consumed 8.860 L of energy carrier (gasoline). WTWe ≈ 51 kWh of electricity.

b) HEV consumed 5.269 L of energy carrier (gasoline). WTWe ≈ 30 kWh of electricity.

c) BEV consumed 20.475 kWh energy carrier (electricity). WTWe ≈ 22 kWh of electricity.

d) H2EV consumed 1.087 kg of energy carrier (hydrogen). WTWe ≈ 41 kWh of electricity.

Average energy carriers need for driving the analyzed cars with different types of propulsion are given in

Picture 9.

The simulation results presented in Figure 10. demonstrate that operating combustion engine vehicles, even hybrid versions, is not the best energy solution. The energy demand of hydrogen-powered vehicles falls between that of combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs) and hybrid vehicles (HEVs) and is not optimal in energy terms. Interestingly, estimates indicate that the energy required to produce hydrogen exceeds the energy required to propel the vehicle. The lowest energy demand occurs in the long-term, natural operation of electric vehicles, and this situation is unlikely to change in the near future.

While cumulative fuel consumption in long-term, natural operation of vehicles from individual fleets does not seem to raise any major concerns (e.g., very high adequacy coefficients for the mathematical model (3) were obtained, based on data entered by individual vehicle users), the conversions into kWh of energy used to travel 100 km may raise legitimate concerns. However, they are provided here not to demonstrate specific values, but rather to demonstrate the algorithm for arriving at them.

5. Conclusions

A method for comparative analysis of energy consumption in passenger car fleets with combustion engine, hybrid, battery-electric, and hydrogen drive systems under long-term operating conditions in Europe is presented in this publication using the example of a fleet of 60 passenger cars, 15 each representing conventional, hybrid, electric, and hydrogen drive systems.

Operational data was obtained from a publicly available online database.

It was assumed that the presented method constitutes a procedural algorithm encompassing:

selecting vehicle types for analysis,

acquiring operational data,

using operational data to create mathematical models describing the energy footprint of each vehicle – including forecasting the expected energy demand for a given mileage,

conducting statistical analyses and averaging the data across each vehicle fleet type.

It has been shown that the proposed algorithm can be based on the theory of cumulative consumption of energy carriers by vehicles in their natural, long-term operation.

The cumulative energy consumption theory provides a valuable framework for understanding energy demand under real-world, long-term vehicle operating conditions. It offers insights that standard tests may not capture—as demonstrated by the performance data analysis of one of the hydrogen-powered vehicles analyzed.

A vehicle’s energy footprint includes cumulative energy consumption, cumulative energy consumption intensity, and cumulative specific energy consumption—providing insight into the evolution of energy efficiency over the vehicle’s operational life. Using actual operating data such as fuel consumption and distance traveled, this methodology provides a comprehensive understanding of a vehicle’s energy requirements under natural, long-term operating conditions.

A vehicle’s energy footprint can be used to more accurately assess a vehicle’s energy needs throughout its lifespan – as demonstrated by data from 60 analyzed vehicles.

In particular, it has been shown that when analyzing vehicle energy demand in natural operation, one should not limit oneself solely to the use of energy carriers during vehicle operation, but should also consider the energy costs of preparing the carriers.

For a comprehensive assessment, and especially for comparing the energy demand of different vehicles with electric ones, it seems appropriate to reduce to the value of electricity.

The results indicate that operating combustion engine vehicles, even hybrid versions, is not the best energy solution compared to using electric vehicles – even considering the current, widely recognized shortcomings of these vehicles (very heavy energy storage systems – batteries, etc.).

The energy demand of hydrogen-powered vehicles falls between that of combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs) and hybrid vehicles (HEVs) and is not optimal in energy terms. Furthermore, the energy required to produce hydrogen currently exceeds the energy required to propel the vehicle with it.

The lowest energy demand occurs in the long-term, natural operation of electric vehicles, and this situation is unlikely to change in the near future.

A separate issue is the possibility of using cumulative fuel consumption theory. and more broadly. energy footprint. as method for multi-aspect comparisons of different vehicle powertrains. including comparisons of vehicles fleet with conventional (ICEV). hybrid (HEV and PHEV). hydrogen (H2EV). and electric (BEV) powertrains.

The presented method for assessing energy consumption has practical implications for:

Assessing vehicle energy performance: By analyzing CFC, ICFC, and SCFC, manufacturers and researchers can assess how vehicles perform under real-world conditions, depending on the vehicle’s mileage (regardless of the fact that these conditions vary randomly during operation), which can lead to improvements in vehicle design, research, and manufacturing.

Policy development: Understanding a vehicle’s energy footprint helps decision-makers develop policies that promote energy efficiency and reduce environmental impact, as well as forecast energy demand, for example, in the case of e-mobility.

Consumer awareness: Providing consumers with information about a vehicle’s energy footprint can influence purchasing decisions regarding more fuel-efficient options.

The presented methodology appears essential for promoting sustainable transport, informing policy decisions, and guiding consumer choices toward cost minimization, including external transport costs, and environmentally friendly options.

Based on the assumption that the presented method can be helpful for producers. decision-makers and consumers striving to improve energy efficiency and reduce environmental impact. further work using it is planned. It seems important to explain the phenomenon of large dispersion in the CFC curves recorded in vehicle fleets. Since model (3) will then become a multidimensional model. artificial neural networks (AI) are planned to be used here.

It is obvious that the data presented above should be treated only as very rough estimates – presented here only to illustrate how the presented method should be used. However, each country has a finite number of refineries. It is known how many and what quality of energy carriers individual refineries produce, and using which energy resources. Furthermore, the vehicle fleet in each country is also defined. Therefore, one can imagine a situation where, after dividing the vehicles in this fleet into groups, it is possible to determine model (3) for each group and average the energy carrier consumption values. It is also possible to determine the share of individual vehicle groups in the total number of vehicles. Therefore, it is possible to determine energy carrier consumption based on the presented method and, importantly, correlate the obtained results with actual data, e.g., from subsequent years. This, in turn, would enable the development of energy demand forecasts with the assumed changes in the shares of individual groups and, more importantly, changes in the type of drive in individual vehicle groups. We see this topic as a benchmark for further research.