Introduction

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) research is a critical component of many clinical studies and medical experiments. It is an integral part of numerous analyses, helping understand the impact of medical interventions not only in their physiological aspects, but also in mental and social domains, which are integral to evaluating therapeutic success.

HRQoL can be assessed in various ways. In its simplest form, it involves asking the patient in an open interview about their subjective assessment of their situation. However, to obtain data that is as objective as possible and suitable for statistical analysis and comparison, standardized tools must be used. This role is fulfilled by health-related quality of life assessment questionnaires.

In clinical practice, researchers typically use tools with simplified structures to obtain easily analyzable data. One such tool is the WHOQOL-BREF [

1], a shortened version of the health-related quality of life assessment questionnaire developed by the World Health Organization. The WHOQOL-BREF consists of 26 questions that address four domains of everyday life functioning: physical, psychological, social, and environmental. It is a shortened version of the WHOQOL-100 [

2], making it easier to use. Each question employs a five-point Likert scale. The questionnaire is used in both clinical practice and scientific research. As of July 11, 2025, there were 3,812 mentions on WHOQOL-BREF [Title/Abstract] in PubMed and over 74,600 in Google Scholar.

The WHOQOL-BREF is a practical tool translated into many languages. However, while using the Polish version in our research, we identified numerous structural and translation errors. This led us to investigate whether similar issues exist in other language versions, the gravity of the discrepancies, and whether they could compromise the reliability and comparability of responses across countries. The aim of this study is therefore to assess the extent of these discrepancies across selected translations and evaluate whether the tool’s international comparability.

Materials and Methods

For this analysis, we reviewed 17 language versions from the WHO website of the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaires in PDF and WORD formats. The languages included Australian English, Bulgarian, Czech, Danish, Dutch (Netherlands), Finnish, French, German, Greek, Italian, Lithuanian, Norwegian, Polish (including a revised Polish version we had improved), Romanian, Slovak, Spanish, and Swedish. All represent European countries, with Australian version added to enable comparison between Australian English and reference English version from the official WHO manual (

https://www.who.int/tools/whoqol/whoqol-bref/docs/default-source/publishing-policies/whoqol-bref/english_whoqol_bref).

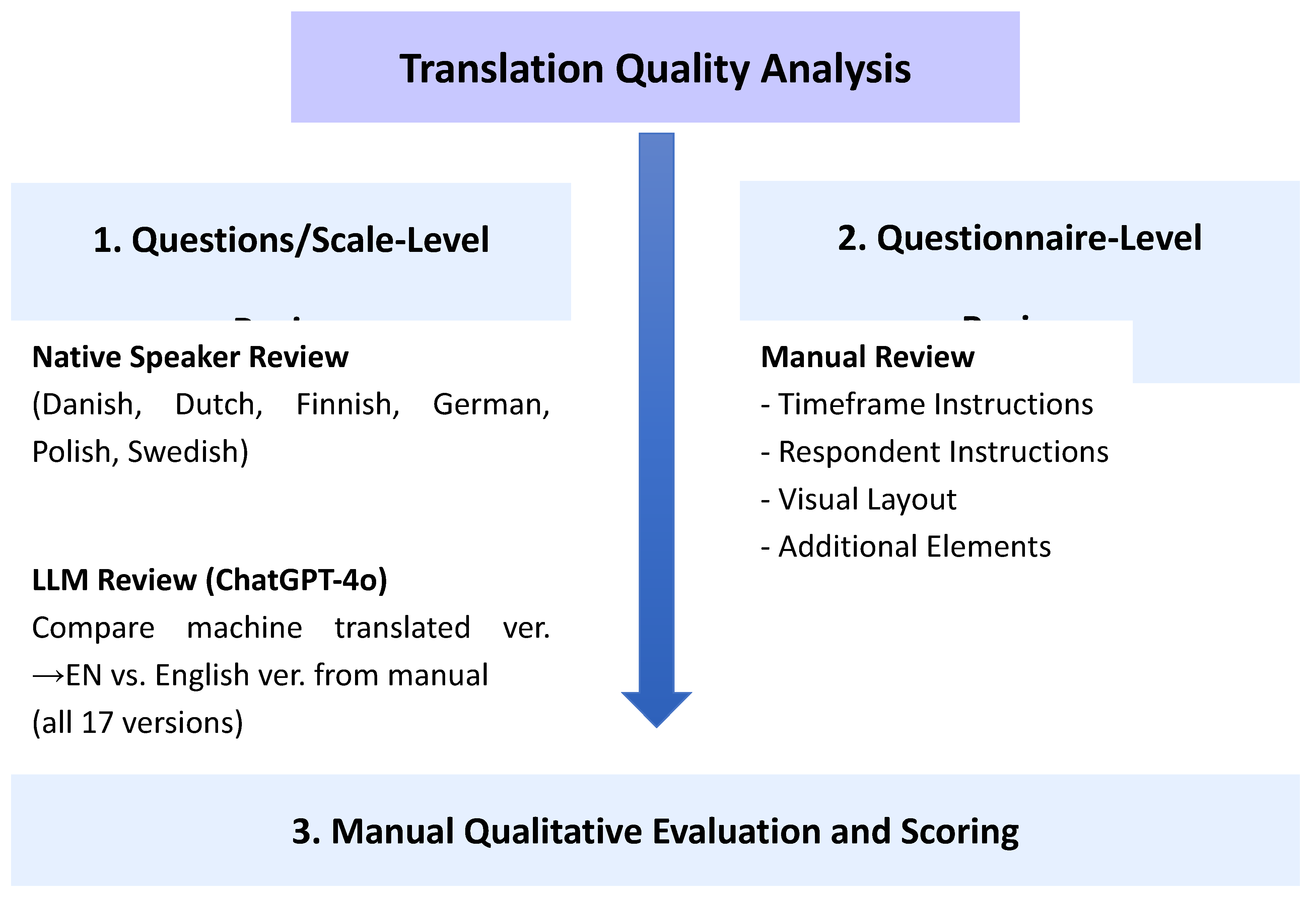

We conducted a qualitative analysis of translation quality for both individual questions and response scales, using two approaches: (1) review by native speakers (for selected questionnaires in Danish, Dutch, Finnish, German, Polish, and Swedish), and (2) assessment using a large language model (LLM) for all versions (ChatGPT 4o, comparing differences between the official English version and the 17 language versions, translated with machine translation tool into English). Furthermore, all questionnaires were analyzed manually in terms of timeframe respondents were instructed to consider when answering, inclusion of essential elements such as instructions for respondents, visual layout and additional components (see

Figure 1 and

Table 1).

All versions were compared to the reference English questionnaire provided as an annex to the official WHO manual. The software used for the analyses included ChatGPT 4o and Google Translate.

The degree of deviation from the original translation was assessed on 9 levels, each assigned a corresponding score with weighted factors (for instance, an incorrect measurement timeframe received higher weight than the missing demographic fields). This permitted the calculation and comparison of the magnitude of deviations across versions (see

Table 1). For questions and response scales, we only assessed the general presence of linguistic discrepancies, not deviations due to country-specific adaptation (such as the minor differences in scale questions observed between the reference English version and Australian English version). A higher score indicates a greater divergence from the reference/original.

Results

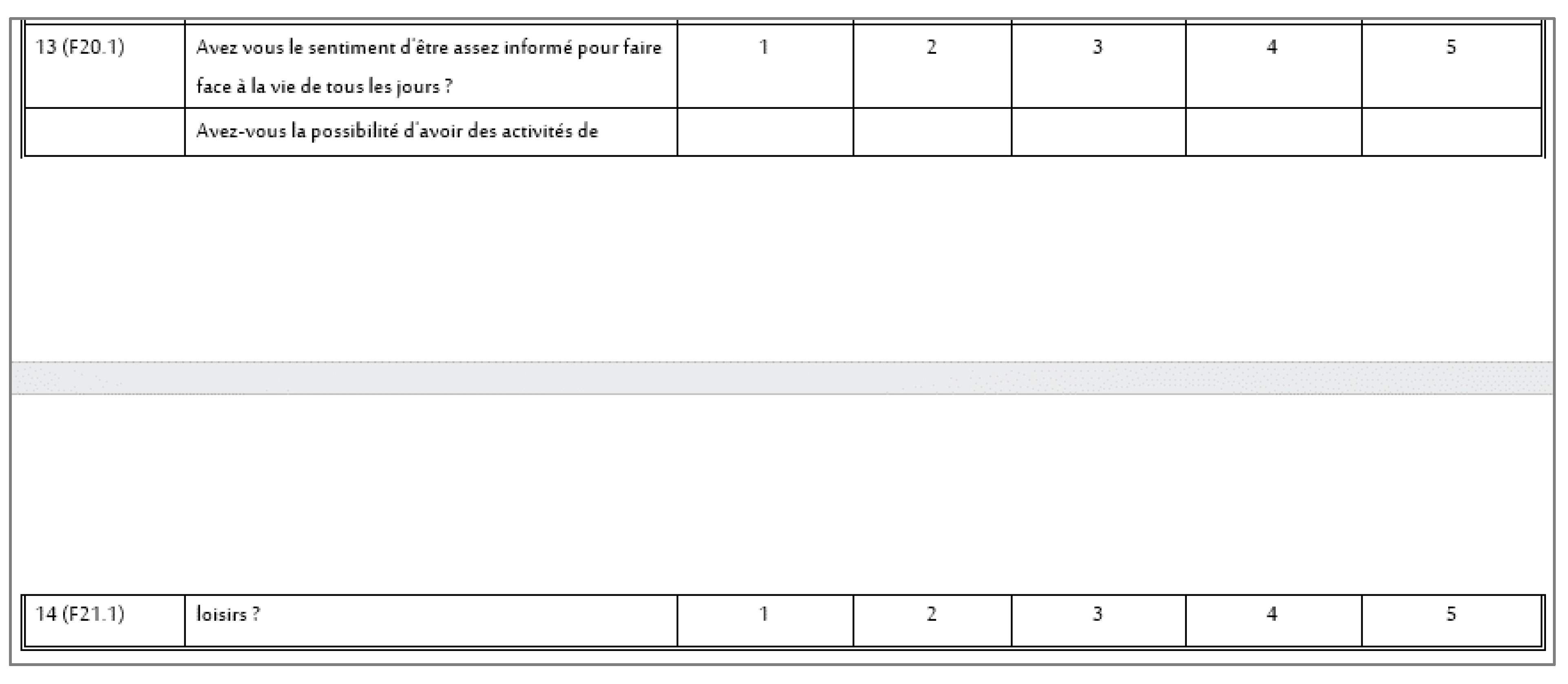

The first analyzed aspect concerned the visual presentation of the entire questionnaire and its questions: general layout, the existence of a demographic section, appropriate title, introduction and instructions for the respondent, acknowledgments, and additional elements. This area exhibited the most discrepancies, although it is important to note that, aside from the instructions for the respondent (the absence of instructions in 5 of the analyzed language versions could lead to errors from the respondent), these elements generally do not significantly impact the results. However, there are exceptions, such as when a question and its scale are split across two pages, which can greatly hinder completing the questionnaire (this was the case in the Slovak and French versions, where a portion of a question in the PDF file—intended for printing by medical staff—was divided, see

Figure 2).

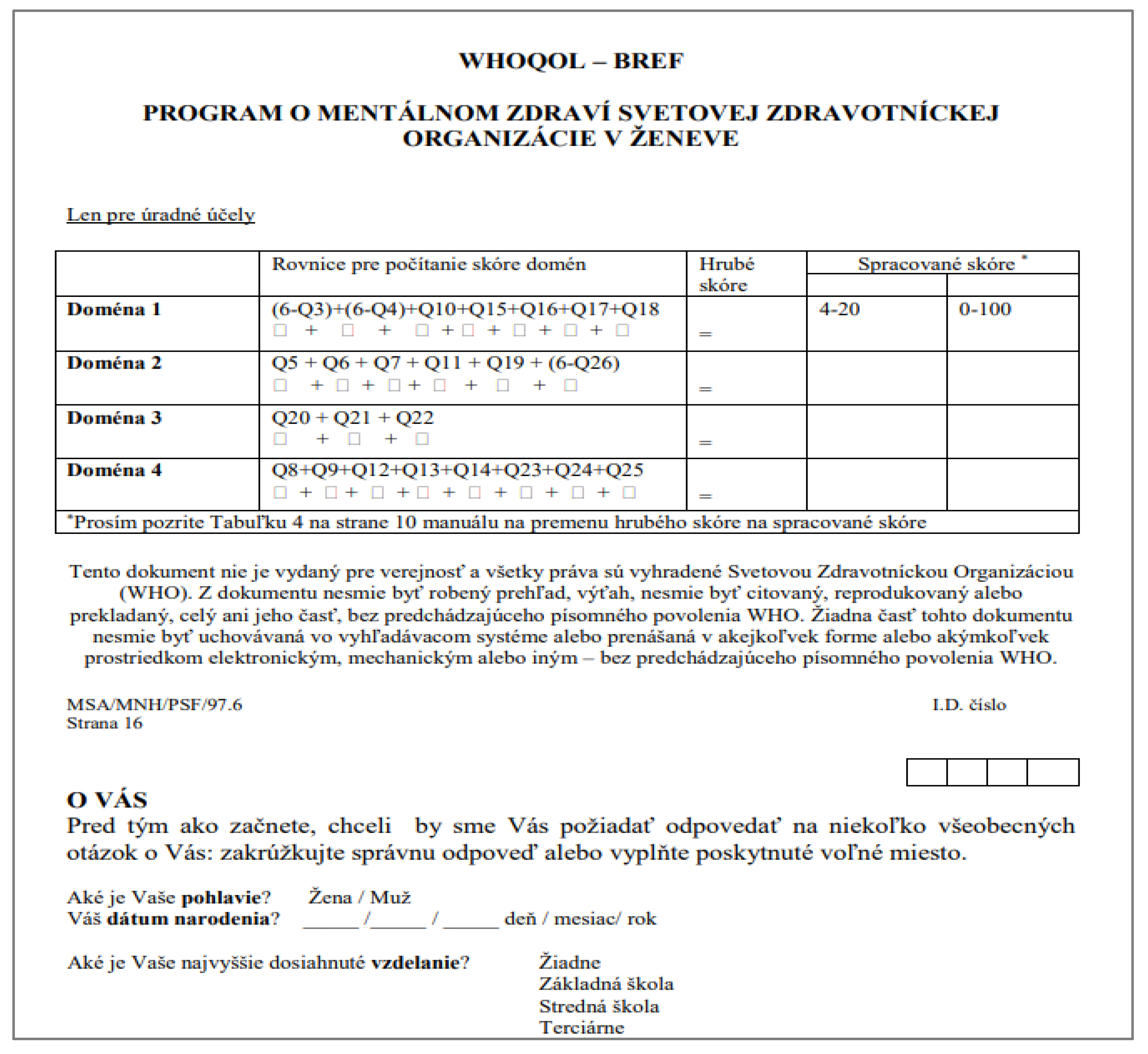

Unnecessary elements, such as a scoring table for medical professionals, also acted as distractor for the patient, as seen e.g. in the Slovak version, which begins with such a table (

Figure 3).

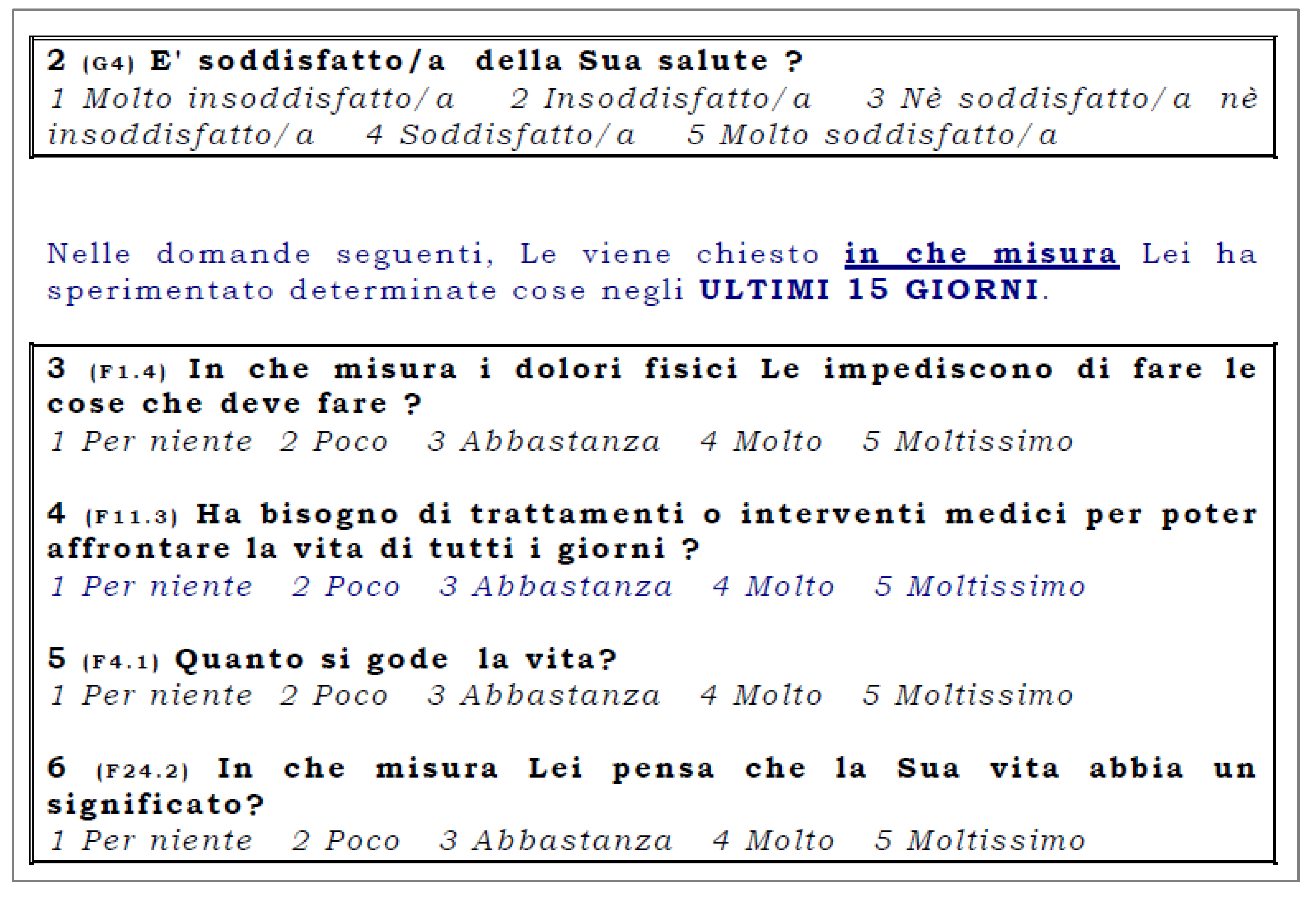

There were also issues with the readability of fonts and colors and graphic design, as in the Italian version, where an illegible italic font and heavy borders reduced readability and visual clarity (

Figure 4).

The most critical error, however, was related to the measurement intervals over which the patient was asked to assess their experiences. The original version of the questionnaire instructs the patient to reflect on the past two weeks, a period that is easy to conceptualize. However, six of the analyzed language versions used different periods: four weeks in the Czech and Polish (unrevised) versions, a month in the Lithuanian and Norwegian versions, and 15 days in the Italian version. The French version did not specify a time interval at all. This means that in these cases, respondents were asked to answer based on a different timeframe than originally intended, which could impact the results, undermining the comparability of data, especially in cross-national analyses that assume methodological uniformity.

- 2.

Translation errors in questions and response scales

The second and more critical area of analysis involved discrepancies in the translation of individual questions and response scales. While some differences may reflect appropriate cultural adaptation, many were clearly translation errors that compromise construct validity.

We began with a detailed review of the Polish version (before revision). One major concern was the consistent exclusive use of the masculine formal address (“Pan”, equivalent to “Mr.”), failing to account for non-male respondents. In Polish, respondents and patients are addressed as “Pan” or “Pani” (Mr. or Ms., not by first name, in line with Polish cultural norms). If the tool is intended for both genders, a direct form such as second-person singular verbs or a dual-form address such as “Pan/i” (“Sir/Madam”) should be used.

More seriously, certain questions in the first Polish version did not correspond to the originally intended domain. For instance, question 15, which in the English original reads “How well are you able to get around?” and refers to Domain 1 (physical – mobility), was translated as “Jak odnajduje się Pan w tej sytuacji?” meaning “How do you find yourself in this situation?”, which is a completely different domain. This difference cannot be explained by cultural adaptation during translation. In this case, the question addresses an entirely different, vague psychological domain, but in the end it will be calculated as mobility, severely skewing the analysis of the patient’s quality of life measurement. A similar mistranslation occurred in the Slovak version, where the question was rendered as: “Ako dobre vyjdete?” which translates to “How well do you get along?”). Again, this does not capture the concept of physical mobility, making the item invalid for its intended purpose.

Another illustrative example of clearly incorrect translation comes from the French questionnaire. Where in the English question 6 original reads “To what extent do you feel your life to be meaningful?” addressing the subjective sense of life’s meaning and purpose,, the French version shifts the focus to philosophical, religious or spiritual belief systems: “Vos croyances personnelles donnent-elles un sens à votre vie?” meaning “Do your personal beliefs give meaning to your life?” Such a discrepancy introduces a different conceptual framework and is difficult to justify based on cultural differences considered during validation. Another example is a slight change of concepts in the Dutch version, where the original question referring to the physical environment has been translated as “de gezondheid van uw omgeving” (“the health of your environment”). This rewording implies ecological or environmental health rather than accessibility, safety, or infrastructure, again leading to a divergence from the intended construct.

Unfortunately, similar issues were identified in most language versions. In some cases, the deviation may appear subtle but could nonetheless introduce systematic bias, particularly in large comparative studies.

The qualitative analysis also revealed problems in the translation of the response scales. Among others, there were grammatical errors in one of the scales in Polish, unnecessary modifications in the Australian version not justified by linguistic norms or validation evidence, and incorrect translations of scale anchors in the Danish and Italian versions.

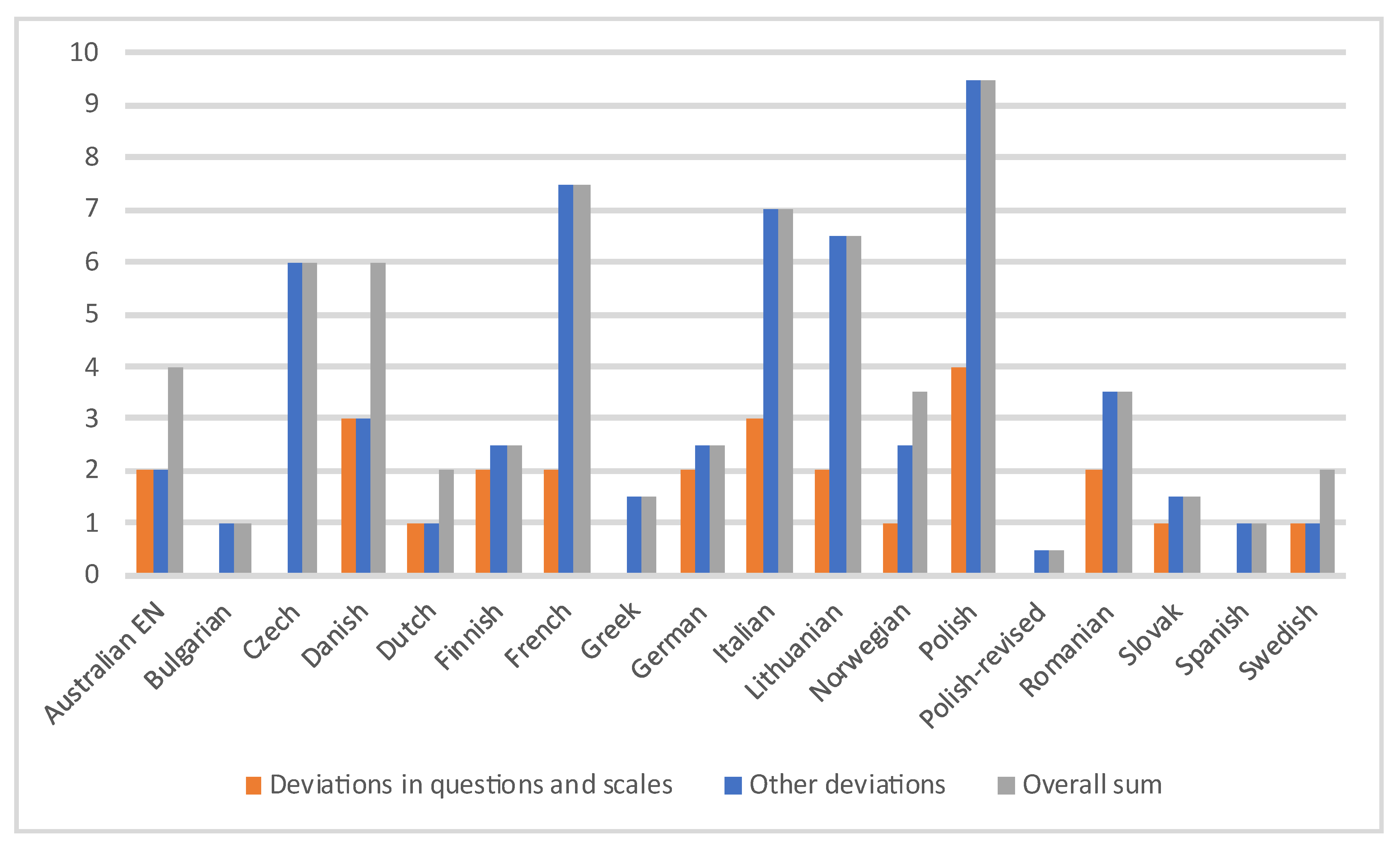

These issues collectively undermine the conceptual and semantic equivalence required for meaningful cross-cultural comparison. A comprehensive breakdown with cumulative deviation scores and detailed analysis across evaluation criteria between the translated questionnaires are presented in

Figure 5 and

Table 2. The extent of discrepancies was highest in the Polish unrevised version (9.5, dropping to 0.5 after the revision) and lowest in Bulgarian and Spanish versions.

Discussion

The advancement and globalization of science and medical research have increased the need for culturally adapted quality of life measurement tools. Where available, the adaptation of existing instruments is usually preferred over creating new ones, as this avoids the creation of superfluous tools [

3], permits comparability of the results across cultures, and promotes information exchange in the scientific community [

4].

However, translating subjective, patient-reported data assessment instruments involves more than simply rendering the text into another language [

5,

6,

7]. The goal of translation is ensuring that the new version will maintain content integrity and conceptual consistency by measuring the target construct as closely as the original [

8,

9,

10,

11]. This expectation in cross-cultural research is commonly referred to as

construct equivalence [

12,

13,

14], the assumption that the tools employed will measure the same constructs in the same way whether in the original language/culture or in the translation [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22].

Despite this, numerous researchers have highlighted a shortage of universally accepted, standardized methodological guidelines for questionnaire translation and cross-cultural adaptation [

19,

23,

24,

25,

26]. While literature often details the translation process – that of the transformation of the questionnaire, many studies neglect the validation—or quality assessment—phase, which is critical for assessing translation quality [

27]. Both European [

15,

28] and US regulatory bodies [

29] have likewise expressed concerns over the methodological rigor and validity of translated tools. A methods review of 47 articles in cross-cultural nursing research by Maneesriwongul and Dixon (2004) found that the translation process was often inadequate [

30]. Similarly, Hawkins et al. (2020) identified ten common types of translation errors across different versions of the Health Literacy Questionnaire [

31]. Such errors may significantly compromise data interpretation. Our findings align with these prior critiques of translation methodologies.

Therefore, to ensure that questionnaire adaptations are reliable, valid, conceptually and semantically equivalent, and culturally relevant for target populations, several experts have advocated for rigorous robust multi-stage processes, from preliminary translation and cross-cultural adaptation [

12,

31,

32,

33,

34] to subsequent validation [

3,

10,

16,

25,

30,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43]. Proper validation is vital for ensuring that the psychometric properties of the new version are not inferior to the original, helps guarantee that the information collected about the target population will be accurate, and enhances acceptance of the questionnaire by professionals and society, helping reassure respondents’ subjective perceptions, especially in the case of complex or sensitive questions [

16,

44,

45].

To date, numerous translations of various iterations of the WHOQOL-BREF have been produced, spanning languages ranging from Akan [

46] and Amharic [

47] to Urdu [

48] and Yoruba [

49]. While most maintain their reliability and validity, some report low internal consistency in at least some of the measures [

50,

51,

52,

53].

This suggests that while the WHOQOL-BREF demonstrates broad cross-cultural utility, certain linguistic and cultural adaptations may negatively impact its psychometric properties, highlighting the need for careful contextual validation in each target population. Our study identifies some of the most critical vulnerabilities in the translation and implementation process and casts light on the scale of the problem, pointing to a need for greater oversight, harmonization, and quality assurance. This includes developing a robust translation protocol, providing training for national teams, and validating tools in collaboration with local and international experts, ideally in coordination with the WHO. This will help better ensure methodological consistency and facilitate meaningful cross-national comparisons of quality of life outcomes.

Conclusions

Our analysis reveals substantial discrepancies among the national versions of the WHOQOL-BREF tool, undermining the comparability of cross-country results. To address this issue, the instrument must undergo rigorous multilingual validation and standardization. The WHO should assume active oversight of the translation process to help safeguard linguistic accuracy and structural consistency. Furthermore, the organization should enforce a uniform layout and formatting standard across all language versions.

Although WHO mentions on its website and in the questionnaires that the translations were not conducted by the organization itself, the mere presence of these tools in the official WHO repository gives them the appearance of being formally endorsed. Researchers and clinicians frequently print and hand them out to patients and publish in medical journals without modification.

Unfortunately, our analysis shows that elements such as layout, instructions, additional elements, question wording, and response scale labels often vary significantly between versions. These translation differences may stem from two factors: (1) appropriate cultural adaptation and localization, and (2) translation errors. In the case of proper adaptation, supported by appropriate multi-step procedures (methodological rigor, piloting, psychometric validation,), variation may be acceptable and documented. However, translation errors can compromise the accuracy and validity of the results.

This issue requires urgent attention, as numerous studies based on the current versions of the WHOQOL-BREF may lack cross-national comparability, potentially distorting conclusions in research over many years. For example, a study might conclude that Polish patients have higher mobility than those in other countries, while in reality the item used measured how they assess their current situation. We recommend that WHO thoroughly review all existing translations, including both linguistic and structural elements, with particular attention to the preservation of instructions for the respondent and conceptual integrity. The organization’s current disavowal of responsibility for this important tool negatively affects the quality of global research and its potential use in international contexts.

Additionally, the first author wishes to note that based on the findings of this study, a revised version of the Polish scale has been accepted and published by the WHO on their website. However, this revision addresses only one language version. The broader issue of the lack of comparability of the scales in other languages remains unresolved. We hope that this publication brings greater awareness to the problem and contributes to the advancement of more reliable comparable research in the field of quality of life assessment.

Limitations

The linguistic analysis of the selected questionnaires was conducted by native speakers, whose task was to verify the correctness of the translation. It must be noted that, due to the absence of external funding, these contributors were volunteers, not professional translators. As such, they mostly identified unnatural or awkward phrasing, which was not necessarily direct errors that would affect construct validity or the ability to accurately assess health-related quality of life.

To complement this subjective evaluation, we employed machine translation and a large language model to translate each version back into English and compare it with the original. This approach allowed us to identify several significant semantic discrepancies. Nevertheless, it is still possible that there are more errors that could only be detected by linguistically trained or psychometric experts with specialized training in questionnaire design and validation.

In the present study, we primarily focused on the problems in the Polish version—the questionnaire we eventually revised—and presented the most noticeable translation errors identified during machine translation in other language versions. Although this may appear limited in scope, it still has epistemic value as it highlights the broader issue of inconsistencies between different language versions, which was the purpose of this study.

Finally, only 17 language versions were included in the comparison. While this may seem restrictive, it should be emphasized that the goal of this work was not an exhaustive audit of all the available translations, which should be the task of the WHO, but to highlight the existing problem of using insufficiently standardized tools for international comparisons. The analysis of these selected tools alone revealed challenges that need to be addressed. In our opinion, a comprehensive review should be initiated by the WHO, and new versions of the tools should be validated not only by country teams but also by the organization, and encompassing both linguistic and psychometric validation.

Funding

The study received no external funding.

Competing Interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Author Contributions

SM: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing – original draft; MBP: writing – original draft, review & editing; ML: writing – review & editing, contribution to data collection; AJ: writing – review & editing, contribution to data collection. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval

No ethical approval is required for this study.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank everyone who assisted in the analysis of the tools: first of all Göran Gustafson for his assistance in recruiting volunteers; and the native-speakers volunteers: Artur Hamlin, Veronika Jaeger, Hans Meerveld, Elefterios Meletis, Polychronis Kostoulas, Anna-Liisa Puttonen, and Marli Zambrano.

The authors would like to also express their gratitude to Prof. Mateusz Jankowski for his valuable support and guidance during the analysis.

References

- Skevington, S.M.; Lotfy, M.; O’Connell, K.A. The World Health Organization’s WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: Psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A Report from the WHOQOL Group. Quality of Life Research 2004, 13, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHOQOL Group. Study protocol for the World Health Organization project to develop a Quality of Life assessment instrument (WHOQOL). Quality of Life Research 1993, 2, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cid, L.; Monteiro, D.; Teixeira, D.S.; Evmenenko, A.; Andrade, A.; Bento, T.; Vitorino, A.; Couto, N.; Rodrigues, F. Assessment in Sport and Exercise Psychology: Considerations and Recommendations for Translation and Validation of Questionnaires. Front Psychol 2022, 13, 806176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramada-Rodilla, J.M.; Serra-Pujadas, C.; Delclós-Clanchet, G.L. Adaptación cultural y validación de cuestionarios de salud: revision y recomendaciones metodológicas. Salud Publica Mex 2013, 55, 57–66. Available online: https://www.scielosp.org/pdf/spm/2013.v55n1/57-66/es. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eremenco, S.L.; Cella, D.; Arnold, B.J. A comprehensive method for the translation and cross validation of health status questionnaires. Eval Health Prof 2005, 28, 212–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hambleton, R.K. The next generation of the ITC test translation and adaptation guidelines. European Journal of Psychological Assessment 2001, 17, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijver, F.; Hambleton, R. Translating tests. some practical guidelines. Eur. Psychol. 1996, 1, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, C.T.; Bernal, H.; Froman, R.D. Methods to document semantic equivalence of a translated scale. Res Nurs Health 2003, 26, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, S.P.; Doward, L.C. The translation and cultural adaptation of patient-reported outcome measures. Value Health 2005, 8, 89–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, D.; Grove, A.; Martin, M.; Eremenco, S.; McElroy, S.; Verjee-Lorenz, A. Principles of Good Practice for the Translation and Cultural Adaptation Process for Patient-Reported Outcomes (PRO) Measures: report of the ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation. Value Health 2005, 8, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumbo, B.D.; Chan, E.K. Validity and validation in social, behavioral, and health sciences; Springer International Publishing, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. Standards for educational and psychological testing; American Educational Research Association: Washington, DC, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Herdman, M.; Fox-Rushby, J.; Badia, X. Equivalence’and the translation and adaptation of health-related quality of life questionnaires. Qual Life Res. 1997, 6, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, M.R. Diagnosing measurement equivalence in cross-national research. J Int Bus Stud. 1995, 26, 573–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, D.; Eremenco, S.; Mear, I.; Martin, M.; Houchin, C.; Gawlicki, M.; Hareendran, A.; Wiklund, I.; Chong, L.Y.; von Maltzahn, R. Multinational trials–recommendations on the translations required, approaches to using the same language in different countries, and the approaches to support pooling the data: the ISPOR Patient-Reported Outcomes Translation and Linguistic Validation Good Research Practices Task Force report. Value Health 2009, 12, 430–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaton, D.E.; Bombardier, C.; Guillemin, F.; Ferraz, M.B. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000, 25, 3186–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M.; Campbell, T.L. Cross-cultural comparisons and the presumption of equivalent measurement and theoretical structure a look beneath the surface. J Cross-Cult Psychol. 1999, 30, 555–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M.; Watkins, D. The issue of measurement invariance revisited. J Cross-Cult Psychol. 2003, 34, 155–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, J.; Santo, R.M.; Guillemin, F. A review of guidelines for cross-cultural adaptation of questionnaires could not bring out a consensus. J Clin Epidemiol 2015, 68, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J.A. Flaherty, others, Developing instruments for cross-cultural psychiatric research. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1988, 176, 257–263. [CrossRef]

- N. Luo, others, Do English and Chinese EQ-5D versions demonstrate measurement equivalence? An exploratory study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2003, 1, 1. [CrossRef]

- Oliveri, M.E.; Lawless, R.; Young, J.W. A validity framework for the use and development of exported assessments; Princeton, NJ, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Acquadro, C.; Jambon, B.; Ellis, D.; Marquis, P. Language and translation issues. In Quality of Life and Pharmacoeconomics in Clinical Trials, 2nd Ed.; Spilker, B., Ed.; Lippincott-Raven: Philadelphia, PA, 1996; pp. 575–585. [Google Scholar]

- Corless, I.B.; Nicholas, P.K.; Nokes, K.M. Issues in cross-cultural quality of life research. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 2001, 33, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenderking, W.R. Comments on the ISPOR Task Force Report on Translation and Adaptation of Outcomes Measures: guidelines and the need for more research. Value Health 2005, 8, 92–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Widenfelt, B.M.; Treffers, P.D.; de Beurs, E.; Siebelink, B.M.; Koudijs, E. Translation and cross-cultural adaptation of assessment instruments used in psychological research with children and families. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 2005, 8, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielsen, Kjaergaard; Pommergaard, H.C.; Burcharth, J.; Angenete, E.; Rosenberg, J. Translation of Questionnaires Measuring Health Related Quality of Life Is Not Standardized: A Literature Based Research Study. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0127050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chassany; Sagnier, P.; Marquis, P.; Fulleton, S.; Aaronson, N. Patient reported outcomes and regulatory issues: the example of health-related quality of life - a European guidance document for the improved integration of HRQL assessment in the drug regulatory process. Drug Inform J 2002, 36, 209–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Health; H. Services, Guidance for Industry: Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims. In Final Guidance; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Maneesriwongul, W.; Dixon, J. Instrument translation process: A methods review. J Adv Nurs 2004, 48, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, M.; Cheng, C.; Elsworth, G.R.; Osborne, R. Translation method is validity evidence for construct equivalence: analysis of secondary data routinely collected during translations of the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ). BMC Med Res Methodol 2020, 20, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acquadro, C.; others. Emerging good practices for translatability assessment (TA) of patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures. 2018, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.M.; Chau, J.P.C.; Holroyd, E. Translation of questionnaires and issues of equivalence. J Adv Nurs 1999, 29, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, M.; Elsworth, G.R.; Osborne, R.H. Application of validity theory and methodology to patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs): building an argument for validity. Qual Life Res. 2018, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquadro, C.; Conway, K.; Hareendran, A.; Aaronson, N. Literature review of methods to translate health-related quality of life questionnaires for use in multinational clinical trials. Value Health 2004, 11, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, M.; Simões, M.; Almeida, L.; Machado, C. Avaliação psicológica. instrumentos validados para a população Portuguesa. In Psychological Assessment. Validated Measures to Portuguese Population, 2nd Edn; Gonçalves, M., Simões, M., Almeida, L., Machado, C., Eds.; Quarteto: Coimbra, 2006; Vol. I. [Google Scholar]

- Guillemin, F.; Bombardier, C.; Beaton, D. Cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: literature review and proposed guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol 1993, 46, 1417–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koller, M.; Aaronson, N.K.; Blazeby, J.; Bottomley, A.; Dewolf, L.; Fayers, P. Translation procedures for standardised quality of life questionnaires: The European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) approach. Eur J Cancer 2007, 43, 1810–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oj, K.; Mainz, J.; Helin, A.; Ribacke, M.; Olesen, F.; Hjortdahl, P. Oversettelse av spørreskjema. Et oversett metodeproblem. Nord Med 1998, 113, 363–366. [Google Scholar]

- A.D. Sperber, Translation and validation of study instruments for cross-cultural research. Gastroenterology 2004, 126, S124–S128. [CrossRef]

- Su, C.T.; Parham, L.D. Generating a valid questionnaire translation for cross-cultural use. Am J Occup Ther 2002, 56, 581–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, S.; Royse, C.F.; Terkawi, A.S. Guidelines for developing, translating, and validating a questionnaire in perioperative and pain medicine. Saudi J Anaesth 2017, 11, S80–S89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallerand, R. Vers une méthodologie de validation transculturelle de questionnaires psychologiques: implications pour la recherche en langue française [Toward a methodology for the transcultural validation of psychological questionnaires: implications for research in the French language]. Can. Psychol. 1989, 30, 662–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grifee, D. Questionnaire translation and questionnaire validation: Are they the same? Paper Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Association for Applied Linguistics, St. Louis, MO, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Maksymowicz, S.; Kukołowicz, P.; Siwek, T.; Rakowska, A. Validation of the revised Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Functional Rating Scale in Poland and its reliability in conditions of the medical experiment. In Neurological Sciences; 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anum; Adjorlolo, S.; Akotia, C.; Aikins, A. Validation of the multidimensional WHOQOL-OLD in Ghana: A study among population-based healthy adults in three ethnically different districts. Brain Behav 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhye, N. Fentahun, Validation of Quality-of-Life assessment tool for Ethiopian old age people. F1000Res 2024, 12, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed; Saqlain, M.; Akhtar, N.; Hashmi, F.; Blebil, A.; Dujaili, J.; Umair, M.; Bukhsh, A. Translation and cross-cultural adaptation of WHOQOL-HIV Bref among people living with HIV/AIDS in Pakistan. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2021, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akinpelu, A.O.; Maruf, F.A.; Adegoke, B.O. Validation of a Yoruba translation of the World Health Organization’s quality of life scale–short form among stroke survivors in Southwest Nigeria. Afr J Med Med Sci 2006, 35, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gebrye, T.; Okoye, E.; Akosile, C.; Onwuakagba, I.; Uwakwe, R.; Igweze, C.; Chukwuma, V. F. Fatoye, Adaptation and Validation of the Nigerian (Igbo) Version of the WHOQOL-OLD Module. Res Soc Work Pract 2022, 33, 798–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Jang, H.; Choi, H. Korean translation and validation of the WHOQOL-DIS for people with spinal cord injury and stroke. Disabil Health J 2017, 10, 627–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedjat, S.; Montazeri, A.; Holakouie, K.; Mohammad, K.; Majdzadeh, R. Psychometric properties of the Iranian interview-administered version of the World Health Organization’s Quality of Life Questionnaire (WHOQOL-BREF): A population-based study. BMC Health Serv Res 2008, 8, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaeipandari, H.; Morowatisharifabad, M.; Mohammadpoorasl, A.; Shaghaghi, A. Cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric validation of the World Health Organization quality of life-old module (WHOQOL-OLD) for Persian-speaking populations. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2020, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).