Submitted:

11 December 2025

Posted:

15 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

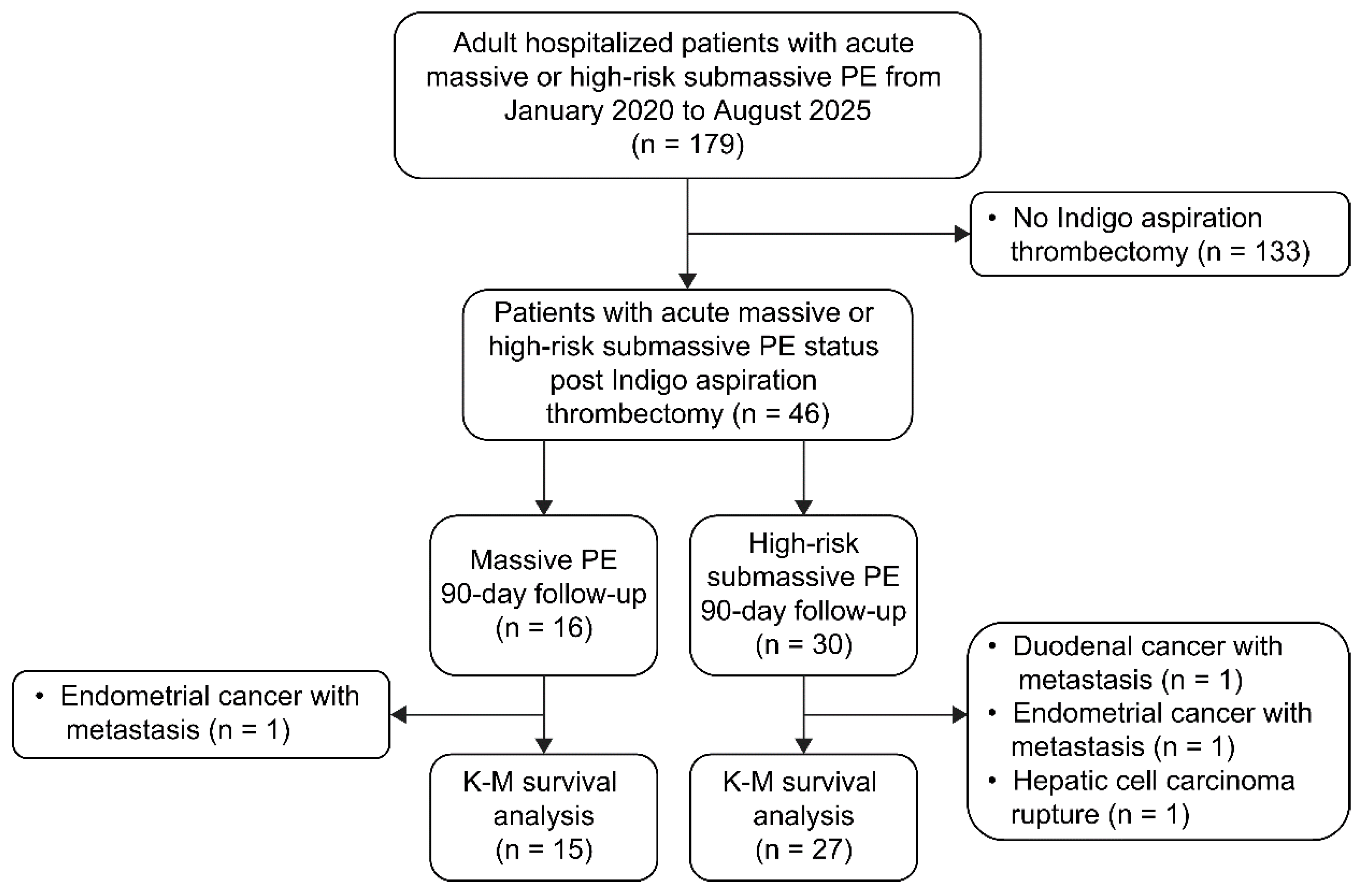

2.1 Study Design and Population

2.2 Vital Signs (Blood Pressure, Heart Rate, Shock index, Respiratory Rate, Partial Pressure of Arterial Oxygen [PaO2]/Fraction of Inspired Oxygen [FiO2] ratio)

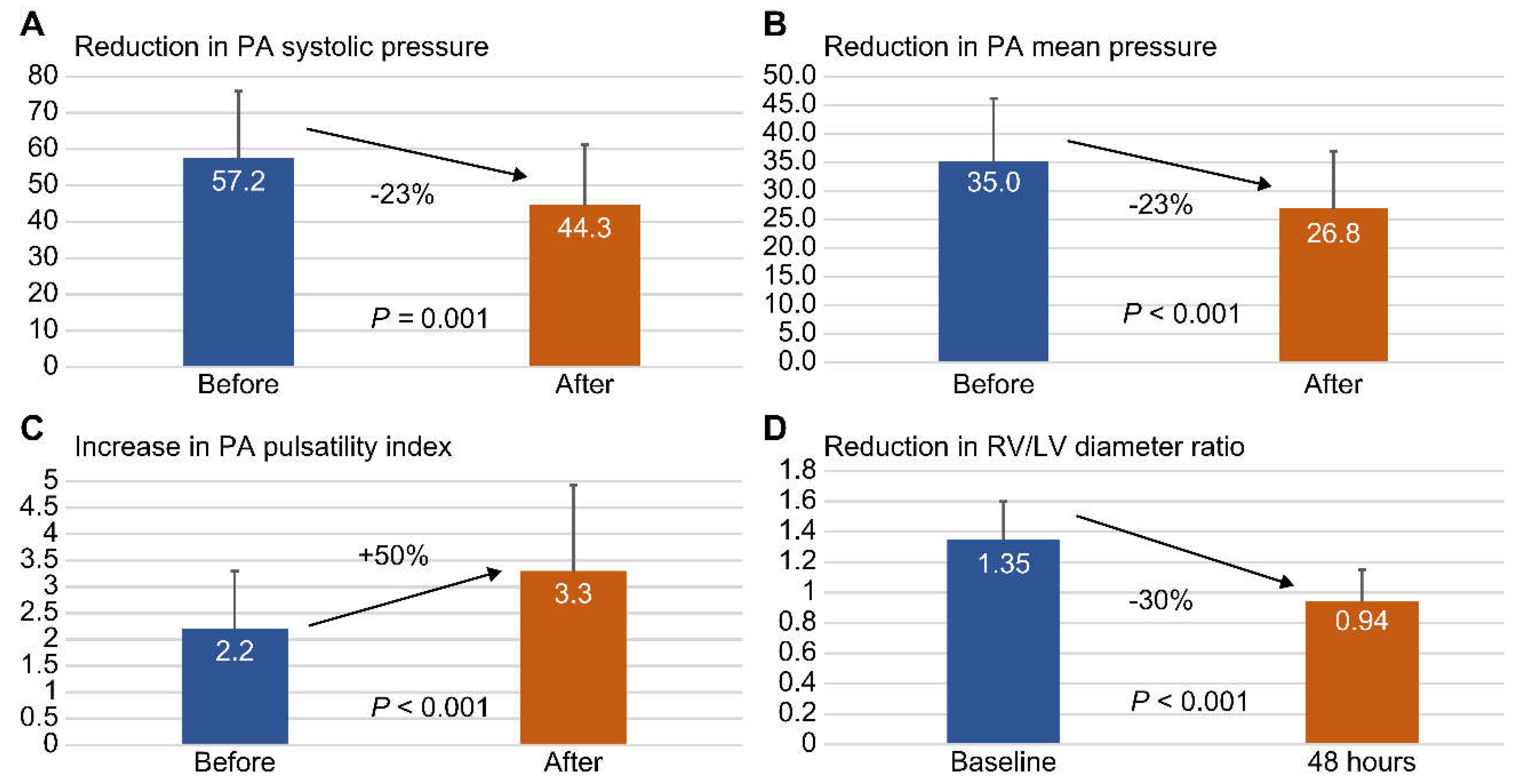

2.3 Right Heart Parameters (Pulmonary Artery [PA] Pressure, Right Atrial Pressure, PA Pulsatility Index, RV/LV Diameter Ratio)

2.4 Severity Evaluation (Percentage of Main Trunk or Bilateral, Mastora Obstruction Index, PE Severity Index)

2.5 Indigo Thrombectomy in Acute Massive or High-Risk Submassive PE

2.6 Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1 Baseline Clinical Characteristics

3.2 Follow-Up of Laboratory Tests on the Day of Admission

3.3 Analyses of Indigo Thrombectomy Treatment Effect on Vital Signs and Right Heart Parameters

3.4 Clinical Outcomes after Indigo Thrombectomy

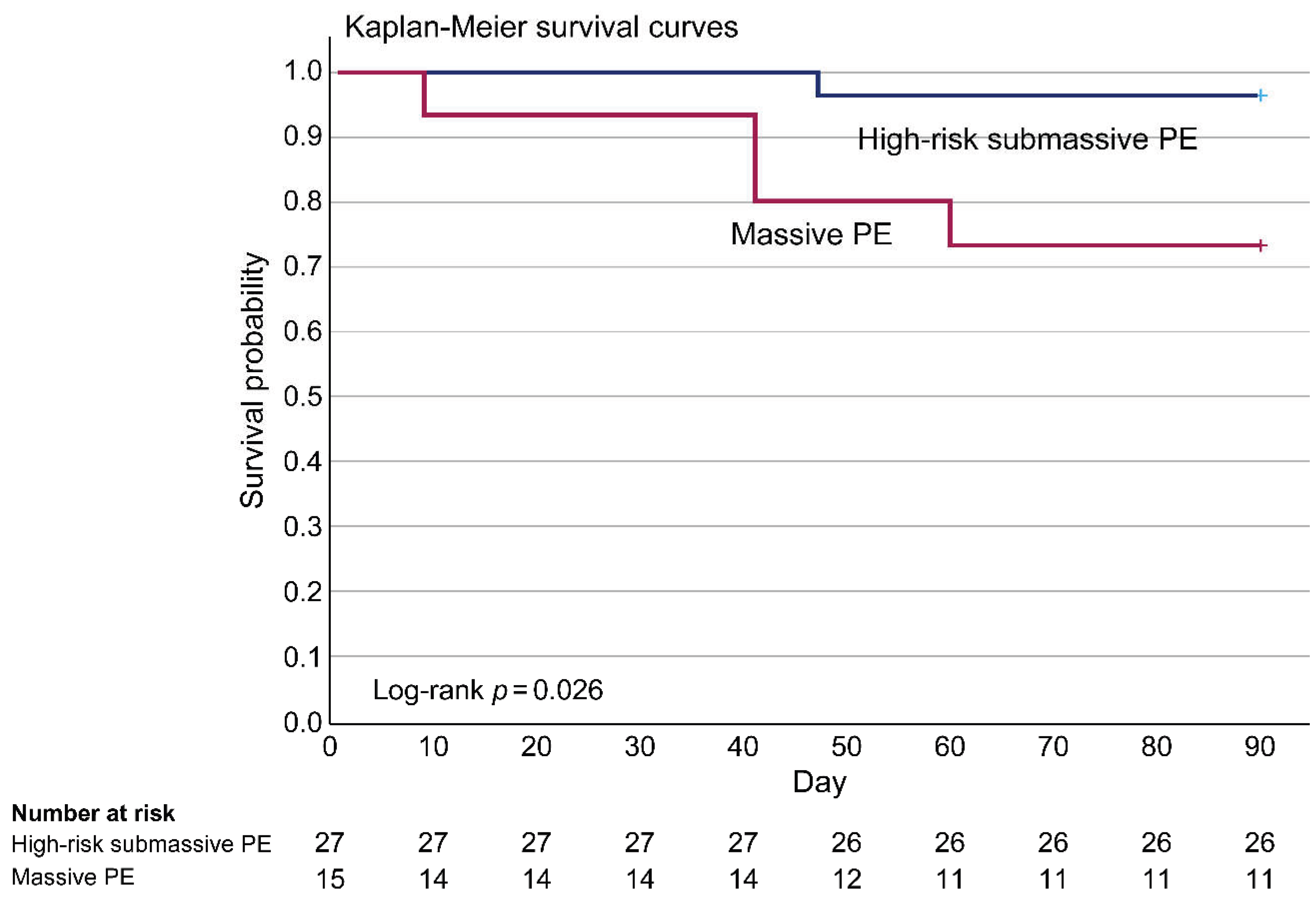

3.5 Ninety-day PE-related Survival Rate Analyzed by Kaplan–Meier Survival Curves

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ECMO | Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation |

| EKOS | EkoSonic endovascular system |

| FiO2 | Fraction of inspired oxygen |

| LV | Left ventricular |

| PA | Pulmonary artery |

| PE | Pulmonary embolism |

| PaO2 | Partial pressure of arterial oxygen |

| RV | Right ventricular |

References

- Hsu, S.H.; Ko, C.H.; Chou, E.H.; Herrala, J.; Lu, T.C.; Wang, C.H.; Chang, W.T.; Huang, C.H.; Tsai, C.L. Pulmonary embolism in United States emergency departments, 2010–2018. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 9070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freund, Y.; Cohen-Aubart, F.; Bloom, B. Acute pulmonary embolism: A review. JAMA 2022, 328, 1336–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottega, T.S.; Vier, M.G.; Baldiaserotto, H.; Oliveira, E.P.; Diaz, C.L.M.; Fernandes, C.J. Thrombolysis in acute pulmonary embolism. Rev Assoc Med Bras 1992, 2020(66), 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinides, S.V.; Meyer, G.; Becattini, C.; Bueno, H.; Geersing, G.J.; Harjola, V.P.; Huisman, M.V.; Humbert, M.; Jennings, C.S.; Jiménez, D.; et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Eur Heart J 2020, 41, 543–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Ammari, Z.; Dasa, O.; Ruzieh, M.; Burlen, J.J.; Shunnar, K.M.; Nguyen, H.T.; Xie, Y.; Brewster, P.; Chen, T.; et al. Long-term mortality after massive, submassive, and low-risk pulmonary embolism. Vasc Med 2020, 25, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polaková, E.; Veselka, J. Management of massive pulmonary embolism. Int J Angiol 2022, 31, 194–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, S.U.; Cho, Y.D.; Choi, S.H.; Yoon, Y.H.; Park, J.H.; Park, S.J.; Lee, E.S. Assessing the severity of pulmonary embolism among patients in the emergency department: Utility of RV/LV diameter ratio. PLOS One 2020, 15, e0242340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolkailah, A.A.; Hirji, S.; Piazza, G.; Ejiofor, J.I.; Ramirez Del Val, F.; Lee, J.; McGurk, S.; Aranki, S.F.; Shekar, P.S.; Kaneko, T. Surgical pulmonary embolectomy and catheter-directed thrombolysis for treatment of submassive pulmonary embolism. J Card Surg 2018, 33, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secemsky, E.; Chang, Y.; Jain, C.C.; Beckman, J.A.; Giri, J.; Jaff, M.R.; Rosenfield, K.; Rosovsky, R.; Kabrhel, C.; Weinberg, I. Contemporary management and outcomes of patients with massive and submassive pulmonary embolism. Am J Med 2018, 131, 1506–1514.e0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, H.A.; Horowitz, J.; Yuriditsky, E. Indigo aspiration system for thrombectomy in pulmonary embolism. Future Cardiol 2023, 19, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannaccone, M.; Sławek-Szmyt, S.; Gamardella, M.; Fumarola, F.; Mangione, R.; Savio, D.; Russo, F.; Boccuzzi, G.; Araszkiewicz, A.; Chieffo, A. The role of pulmonary artery pulsatility index to assess the outcomes following catheter directed therapy in patients with intermediate-to-high and high-risk pulmonary embolism. Cardiovasc Revasc Med 2025, S1553-8389(25)00044-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerche, M.; Bailis, N.; Akritidou, M.; Meyer, H.J.; Surov, A. Pulmonary vessel obstruction does not correlate with severity of pulmonary embolism. J Clin Med 2019, 8, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natanzon, S.S.; Fardman, A.; Chernomordik, F.; Mazin, I.; Herscovici, R.; Goitein, O.; Ben-Zekry, S.; Younis, A.; Grupper, A.; Matetzky, S.; et al. PESI score for predicting clinical outcomes in PE patients with right ventricular involvement. Heart Vessels 2022, 37, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Soueidy, A.; Miller, G.; Hussain, S.; Rachoin, J.S.; Hunter, K.; Iliadis, E. Aspiration thrombectomy compared to catheter directed thrombolysis in pulmonary embolism: Outcomes from a tertiary referral center. Cardiol J 2025, 32, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandra, V.M.; Khaja, M.S.; Kryger, M.C.; Sista, A.K.; Wilkins, L.R.; Angle, J.F.; Sharma, A.M. Mechanical aspiration thrombectomy for the treatment of pulmonary embolism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vasc Med 2022, 27, 574–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, D.W.; Ayadi, B.; Dexter, D.J.; Rosenberg, M.; Horowitz, J.M.; Chuang, M.L.; Dohad, S. Continuous mechanical aspiration thrombectomy performs equally well in main versus branch pulmonary emboli: A subgroup analysis of the EXTRACT-PE trial. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2023, 101, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calé, R.; Pereira, A.R.; Ferreira, F.; Alegria, S.; Morgado, G.; Martins, C.; Ferreira, M.; Gomes, A.; Judas, T.; Gonzalez, F.; et al. Continuous Aspiration Mechanical Thrombectomy for the management of intermediate- and high-risk pulmonary embolism: Data from the first cohort in Portugal. Rev Port Cardiol 2022, 41, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeba, F.; Singh, I.; Gomez, J.; Khosla, A. Right ventricular-pulmonary arterial uncoupling thresholds in acute pulmonary embolism. Lung 2025, 203, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moady, G.; Mobarki, L.; Or, T.; Shturman, A.; Atar, S. Echocardiography-based pulmonary artery pulsatility index correlates with outcomes in patients with acute pulmonary embolism. J Clin Med 2025, 14, 2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iannaccone, M.; Gamardella, M.; Fumarola, F.; Mangione, R.; Botti, G.; Russo, F.; Boccuzzi, G. Pulmonary artery pulsatility index evaluation in intermediate-to-high and high-risk pulmonary embolism patients underwent transcatheter intervention. Eur Heart J 2024, 45 (Suppl 1), ehae666.2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sista, A.K.; Horowitz, J.M.; Tapson, V.F.; Rosenberg, M.; Elder, M.D.; Schiro, B.J.; Dohad, S.; Amoroso, N.E.; Dexter, D.J.; Loh, C.T.; et al. Indigo aspiration system for treatment of pulmonary embolism: Results of the EXTRACT-PE trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2021, 14, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriarty, J.M.; Dohad, S.Y.; Schiro, B.J.; Tamaddon, H.; Heithaus, R.E.; Iliadis, E.A.; Dexter, D.J.; Shavelle, D.M.; Leal, S.R.N.; Attallah, A.S.; et al. Clinical, functional, and quality-of-life outcomes after computer assisted vacuum thrombectomy for pulmonary embolism: Interim analysis of the STRIKE-PE Study. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2024, 35, 1154–1165.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sławek-Szmyt, S.; Stępniewski, J.; Kurzyna, M.; Kuliczkowski, W.; Jankiewicz, S.; Kopeć, G.; Darocha, S.; Mroczek, E.; Pietrasik, A.; Grygier, M.; et al. Catheter-directed mechanical aspiration thrombectomy in a real-world pulmonary embolism population: A multicenter registry. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2023, 12, 584–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.S.; Yuriditsky, E.; Truong, H.P.; Zhang, P.; Greco, A.A.; Elbaum, L.; Mukherjee, V.; Hena, K.; Postelnicu, R.; Alviar, C.L.; et al. Real-time risk stratification in acute pulmonary embolism: The utility of RV/LV diameter ratio. Thromb Res 2025, 250, 109323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, B.E.; Tan, K.T.; Jaberi, A.; Donahoe, L.; de Perrot, M.; McInnis, M.C.; Granton, J.T.; Mafeld, S. Procedure-related mortality in aspiration thrombectomy for pulmonary embolism: A MAUDE Database Analysis of the Inari FlowTriever and Penumbra indigo Systems. J Endovasc Ther 2024, 15266028241307848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cueto-Robledo, G.; Rivera-Sotelo, N.; Roldan-Valadez, E.; Narvaez-Oriani, C.A.; Cueto-Romero, H.D.; Gonzalez-Hermosillo, L.M.; Hidalgo-Alvarez, M.; Barrera-Jimenez, B. A brief review on failed hybrid treatment for massive pulmonary embolism: Catheter-directed thrombolysis (CDT) and pharmaco-mechanical thrombolysis (PMT). Curr Probl Cardiol 2022, 47, 101294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glazier, H.A.; Kaki, A. Role of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in the treatment of massive pulmonary embolism. Int J Angiol 2024, 33, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munagala, R.; Patel, H.; Sathe, P.; Singh, A.; Narasimhan, M. The use of veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO) for acute high risk pulmonary embolism: A systematic review. Curr Cardiol Rev 2025, 21, e1573403X339627, e1573403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silver, M.J.; Giri, J.; Duffy, Á.; Jaber, W.A.; Khandhar, S.; Ouriel, K.; Toma, C.; Tu, T.; Horowitz, J.M. Incidence of mortality and complications in high-risk pulmonary embolism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Soc CardioVasc Angiogr Interv 2023, 2, 100548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.S.; Maqsood, M.H.; Sharp, A.S.P.; Postelnicu, R.; Sethi, S.S.; Greco, A.; Alviar, C.; Bangalore, S. Efficacy and safety of anticoagulation, catheter-directed thrombolysis, or systemic thrombolysis in acute pulmonary embolism. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2023, 16, 2644–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieraccini, M.; Guerrini, S.; Laiolo, E.; Puliti, A.; Roviello, G.; Misuraca, L.; Spargi, G.; Limbruno, U.; Breggia, M.; Grechi, M. Acute massive and submassive pulmonary embolism: Preliminary validation of aspiration mechanical thrombectomy in patients with contraindications to thrombolysis. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2018, 41, 1840–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, A.S.; Matetić, A.; Elgendy, I.Y.; Lopez-Mattei, J.; Kotronias, R.A.; Sun, L.Y.; Yong, J.H.; Bagur, R.; Van Spall, H.G.C.; Mamas, M.A. The association between cancer diagnosis, care, and outcomes in 1 million patients hospitalized for acute pulmonary embolism. Int J Cardiol 2023, 371, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Li, B.; Chen, H.; Belfeki, N.; Monchi, M.; Moini, C. The role of troponin in the diagnosis and treatment of acute pulmonary embolism: Mechanisms of elevation, prognostic evaluation, and clinical decision-making. Cureus 2024, 16, e67922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsukagoshi, J.; Wick, B.; Karim, A.; Khanipov, K.; Cox, M.W. Perioperative and intermediate outcomes of patients with pulmonary embolism undergoing catheter-directed thrombolysis vs percutaneous mechanical thrombectomy. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord 2024, 12, 101958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaber, W.A.; Gonsalves, C.F.; Stortecky, S.; Horr, S.; Pappas, O.; Gandhi, R.T.; Pereira, K.; Giri, J.; Khandhar, S.J.; Ammar, K.A.; et al. Large-bore mechanical thrombectomy versus catheter-directed thrombolysis in the management of intermediate-risk pulmonary embolism: Primary results of the Peerless randomized controlled trial. Circulation 2025, 151, 260–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| All (n = 46) |

Massive PE (n = 16) |

High-risk submassive PE (n = 30) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y), mean ± SD | 59 ± 16 | 61 ± 15 | 55 ± 19 | 0.21 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 31 (67.4) | 12 (75.0) | 19 (63.3) | 0.43 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 27.4 ± 6.3 | 26.5 ± 5.9 | 27.9 ± 6.5 | 0.50 |

| Chronic disease | ||||

| Pregnancy, n (%) | 20 (4.3) | 1 (6.3) | 1 (3.3) | 0.65 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 4 (8.7) | 1 (6.3) | 3 (10.0) | 0.68 |

| Surgery, n (%) | 10 (21.7) | 2 (12.5) | 8 (26.7) | 0.28 |

| Immobility, n (%) | 9 (19.6) | 3 (18.8) | 6 (20.0) | 0.92 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 2 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (6.7) | 0.30 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 10 (21.7) | 5 (31.3) | 5 (16.7) | 0.26 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 19 (41.3) | 9 (56.3) | 10 (33.3) | 0.14 |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 2 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (6.7) | 0.30 |

| Cancer, n (%) | 16 (34.8) | 3 (18.8) | 13 (43.3) | 0.10 |

| Heart failure, n (%) | 2 (4.3) | 1 (6.3) | 1 (3.3) | 0.65 |

| Hemorrhagic stroke, n (%) | 5 (10.9) | 1 (6.3) | 4 (13.3) | 0.47 |

| Ischemic stroke, n (%) | 3 (6.5) | 1 (6.3) | 2 (6.7) | 0.96 |

| Autoimmune disease, n (%) | 3 (6.5) | 2 (12.5) | 1 (3.3) | 0.24 |

| Deep vein thrombosis, n (%) | 26 (56.5) | 7 (43.8) | 19 (63.3) | 0.21 |

| Severity evaluation | ||||

| Main trunk or bilateral, n (%) | 23 (50.0) | 9 (56.3) | 14 (46.7) | 0.55 |

| Mastora obstruction index, mean ± SD | 81.4 ± 14.1 | 87.0 ± 12.0 | 78.4 ± 14.4 | 0.05 |

| PE severity index at admission, mean ± SD | 139.1 ± 39.2 | 161.6 ± 35.5 | 127.1 ± 36.1 | 0.003 |

| Additional procedure | ||||

| Surgical embolectomy, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

| Systemic thrombolysis, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

| Catheter-directed thrombolysis, n (%) | 21 (45.7) | 10 (62.5) | 9 (30.0) | 0.03 |

| EkoSonic endovascular system, n (%) | 24 (52.2) | 12 (75.0) | 12 (40.0) | 0.02 |

| ECMO, n (%) | 9 (19.6) | 9 (56.3) | 0 (0.0) | <0.001 |

| Inferior vena cava filter, n (%) | 37 (80.4) | 11 (68.8) | 26 (86.7) | 0.15 |

| All (n = 46) |

Massive PE (n = 16) |

High-risk submassive PE (n = 30) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood counts | ||||

| WBC (K/μL), mean ± SD | 11.2 ± 5.2 | 13.6 ± 4.9 | 9.9 ± 5.0 | 0.02 |

| Hemoglobin (%), mean ± SD | 11.4 ± 2.1 | 12.1 ± 2.1 | 11.0 ± 2.1 | 0.09 |

| Platelet (K/μL), mean ± SD | 232.2 ± 152.9 | 183.0 ± 95.8 | 258.4 ± 171.7 | 0.11 |

| Coagulation factors | ||||

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL), mean ± SD | 302.1 ± 123.5 | 238.6 ± 69.3 | 335.9 ± 133.2 | 0.009 |

| D-dimer (ng/mL), mean ± SD | 25315.1 ± 26166.4 | 37310.4 ± 29480.9 | 18917.6 ± 22162.1 | 0.02 |

| Biochemical indices | ||||

| Troponin-I (ng/mL), mean ± SD | 0.33 ± 0.60 | 0.65 ± 0.83 | 0.15 ± 0.31 | 0.005 |

| Troponin-I > 0.04 ng/mL, n (%) | 28 (60.9) | 14 (87.5) | 14 (46.7) | 0.006 |

| eGFR (mL/min), mean ± SD | 80.5 ± 39.5 | 57.6 ± 26.4 | 93.6 ± 40.0 | 0.003 |

| hsCRP (mg/dL), mean ± SD | 4.7 ± 5.3 | 4.5 ± 4.8 | 4.8 ± 5.7 | 0.86 |

| Before thrombectomy (n = 46) |

After thrombectomy (n = 46) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vital signs | |||

| Systolic blood pressure, mean ± SD | 119.3 ± 23.1 | 125.7 ± 23.0 | 0.19 |

| Mean artery pressure, mean ± SD | 89.5 ± 16.7 | 92.4 ± 14.9 | 0.37 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mean ± SD | 74.6 ± 15.5 | 75.8 ± 14.6 | 0.69 |

| Heart rate, mean ± SD | 100.8 ± 23.1 | 96.9 ± 21.1 | 0.40 |

| Shock index, mean ± SD | 0.88 ± 0.30 | 0.81 ± 0.29 | 0.22 |

| Respiratory rate, mean ± SD | 22.0 ± 5.7 | 20.0 ± 4.4 | 0.06 |

| PaO2 / FiO2 ratio, mean ± SD | 137.3 ± 57.6 | 270.6 ± 84.5 | <0.001 |

| Right heart parameters | |||

| PA systolic pressure, mean ±SD | 57.2 ± 18.8 | 44.3 ± 16.9 | 0.001 |

| PA mean pressure, mean ± SD | 35.0 ± 11.1 | 26.8 ± 10.1 | <0.001 |

| PA diastolic pressure, mean ± SD | 23.9 ± 9.6 | 18.1 ± 8.7 | 0.003 |

| Right atrial pressure, mean ± SD | 15.8 ± 4.9 | 8.5 ± 3.2 | <0.001 |

| PA pulsatility index, mean ± SD | 2.2 ± 1.1 | 3.3 ± 1.6 | <0.001 |

| RV / LV diameter ratio, mean ± SD | 1.35 ± 0.25 | 0.94 ± 0.21 | <0.001 |

|

All (n = 46) |

Massive PE (n = 16) |

High-risk submassive PE (n = 30) |

p-value | ||

| Vital signs | |||||

| Mean artery pressure before thrombectomy, mean ± SD | 89.5 ± 16.7 | 80.6 ± 17.0 | 94.2 ± 14.7 | 0.007 | |

| Mean artery pressure after thrombectomy, mean ± SD | 92.4 ± 14.9 | 89.5 ± 16.2 | 94.0 ± 14.2 | 0.33 | |

| Shock index before thrombectomy, mean ± SD | 0.88 ± 0.30 | 1.11 ± 0.35 | 0.76 ± 0.18 | <0.001 | |

| Shock index after thrombectomy, mean ± SD | 0.81 ± 0.29 | 0.92 ± 0.40 | 0.75 ± 0.20 | 0.06 | |

| PaO2 / FiO2 ratio before thrombectomy, mean ± SD | 137.3 ± 57.6 | 128.4 ± 59.1 | 142.1 ± 57.2 | 0.45 | |

| PaO2 / FiO2 ratio after thrombectomy, mean ± SD | 270.6 ± 84.5 | 272.1 ± 97.4 | 269.8 ± 78.6 | 0.93 | |

| Right heart parameters | |||||

| PA mean pressure before thrombectomy, mean ± SD | 35.0 ± 11.1 | 39.1 ± 12.1 | 32.8 ± 10.0 | 0.07 | |

| PA mean pressure after thrombectomy, mean ± SD | 26.8 ± 10.1 | 28.3 ± 10.4 | 26.0 ± 10.1 | 0.47 | |

| PA pulsatility index before thrombectomy, mean ± SD | 2.2 ± 1.1 | 2.0 ± 0.9 | 2.3 ± 1.2 | 0.30 | |

| PA pulsatility index after thrombectomy, mean ± SD | 3.3 ± 1.6 | 3.7 ± 1.6 | 2.6 ± 1.2 | 0.02 | |

| RV / LV diameter ratio before thrombectomy, mean ± SD | 1.35 ± 0.25 | 1.44 ± 0.2 | 1.29 ± 0.24 | 0.06 | |

| RV / LV diameter ratio after thrombectomy, mean ± SD | 0.94 ± 0.21 | 1.05 ± 0.2 | 0.88 ± 0.19 | 0.01 | |

| Major bleeding | |||||

| BARC 3B bleeding, n (%) | 6 (13.0) | 5 (31.3) | 1 (3.3) | 0.007 | |

| BARC 3C bleeding, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - | |

| BARC 5 bleeding, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - | |

| Mortality | |||||

| 90-day all-cause mortality, n (%) | 9 (19.6) | 5 (31.3) | 4 (13.3) | 0.15 | |

| 90-day PE-related mortality, n (%) | 5 (10.9) | 4 (25.0) | 1 (3.3) | 0.02 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).