1. Introduction & State of the Art

1.1. Introduction

Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L. Moench) is a drought-tolerant cereal crop widely cultivated in arid and semi-arid regions across Africa, Asia, and the Americas. It serves as a staple food, fodder, and industrial raw material. However, under certain environmental and physiological conditions, sorghum can become toxic due to the presence of cyanogenic glucosides, primarily dhurrin. Upon tissue disruption, dhurrin undergoes enzymatic degradation to release hydrogen cyanide (HCN), which can be lethal to livestock (Poulton, 1990). Sorghum poisoning is particularly prevalent during droughts, frosts, or in young regrowth stages. The need for sustainable agricultural practices has turned attention to agroforestry as a mitigation strategy. Agroforestry, which combines trees with crops and/or livestock, may alleviate stress-induced dhurrin production, improve soil quality, and diversify forage sources (Garrity, 2004). This paper aims to review the biochemical mechanisms of sorghum toxicity, its ecological and agronomic risk factors, and explores the role of agroforestry in reducing the incidence and impact of sorghum poisoning.

1.2. Chemical Basis of Sorghum Poisoning

The toxic effects of sorghum are primarily due to the presence of dhurrin (C14H17NO7), a cyanogenic glucoside synthesized in significant amounts in young plant tissues. Under stress or mechanical damage, dhurrin is hydrolyzed by the enzyme beta-glucosidase to p-hydroxymandelonitrile, which rapidly decomposes into benzaldehyde and hydrogen cyanide (HCN) (Koenig et al., 1999).

HCN interferes with cellular respiration by binding to cytochrome c oxidase, halting ATP production and causing hypoxic cell death (Conn, 2008). Dhurrin content in sorghum is influenced by genetic traits, plant developmental stage, nitrogen fertilization, and environmental stresses such as drought or frost (Busk & Møller, 2002). Young seedlings and stressed regrowth contain the highest dhurrin levels, making them particularly dangerous for grazing livestock. Understanding the biochemical pathway of dhurrin breakdown is essential for developing management strategies to prevent poisoning events.

1.3. Incidence & Risk Factors

Sorghum poisoning occurs when animals, particularly ruminants such as cattle, sheep, and goats, consume plants with high HCN concentrations. Risk is greatest during drought, frost, or immediately after rainfall following prolonged dryness, all of which increase dhurrin synthesis due to plant stress (Miller et al., 2011).

Sublethal HCN exposure leads to chronic health effects such as reduced weight gain, infertility, and goiter due to thiocyanate interference in iodine metabolism (Majak et al., 2003). Nitrogen fertilizers, especially when over-applied, can exacerbate dhurrin accumulation (McLennan et al., 2008). Improper grazing schedules and lack of alternative forage further elevate the risk. Thus, proper pasture management, stress monitoring, and awareness of high-risk periods are crucial in preventing outbreaks of sorghum poisoning in livestock systems. Sorghum poisoning poses significant health risks to cattle due to the presence of cyanogenic glycosides, primarily dhurrin, which converts to toxic hydrogen cyanide (HCN) when the plant is damaged or stressed (Busk & Møller, 2002). Acute poisoning can lead to rapid death from respiratory failure, as HCN inhibits cellular oxygen utilization (Conn, 2008). Chronic exposure causes weight loss, reduced fertility, and thyroid dysfunction due to thiocyanate interference with iodine metabolism (Majak et al., 2003). Drought-stressed or young sorghum plants contain the highest HCN concentrations, making proper grazing management essential (Miller et al., 2011).

Table 1.

Major risk factors influencing cyanogenic potential (HCN-p) in sorghum.

Table 1.

Major risk factors influencing cyanogenic potential (HCN-p) in sorghum.

| Risk Factor Category |

Specific Factor |

Effect on Dhurrin/HCN |

References |

| Developmental Stage |

Seedling stage |

Very High |

Busk & Møller, 2002 |

| Developmental Stage |

Regrowth after cutting |

High |

Miller et al., 2011 |

| Developmental Stage |

Mature plant stage |

Low |

Pande et al., 2002 |

| Environmental Stress |

Drought / Water deficit |

High |

Gleadow & Møller, 2014 |

| Environmental Stress |

Frost / Chilling damage |

High |

Majak et al., 2003 |

| Environmental Stress |

High Soil Temperature |

Moderate to High |

Koenig et al., 1999

|

| Agronomic Practices |

High Nitrogen Fertilization |

High |

McLennan et al., 2008 |

| Agronomic Practices |

Low Soil Sulfur |

Moderate Increase |

Olafadehan, 2011 |

| Agronomic Practices |

Herbicide Application |

Variable (can be High) |

|

| Soil & Climate |

Low Soil Fertility |

Moderate |

Sileshi et al., 2014

|

| Soil & Climate |

Post-drought rainfall on wilted crop |

Very High |

Miller et al., 2011

|

2. Risk Mitigation Strategies

Having established the mechanisms and risks of sorghum poisoning, this section delves into the portfolio of available mitigation strategies. These range from field-level interventions like agroforestry to advances in genetics and feed management.

2.1. Agroforestry and Phytoremediation for Cyanide Mitigation

Agroforestry practices can significantly reduce the incidence of sorghum poisoning through multiple ecological mechanisms. Trees such as Leucaena leucocephala, Gliricidia sepium, and Sesbania sesban enhance soil nitrogen levels through biological nitrogen fixation, reducing the need for synthetic fertilizers that encourage dhurrin synthesis (Sileshi et al., 2014). They also serve as alternate fodder sources, thereby diluting the dietary HCN intake in livestock. Moreover, tree canopy provides shade and microclimatic buffering, which mitigates abiotic stresses such as heat and drought—key triggers for dhurrin accumulation (Jose, 2009).

Strategic integration of forage trees within sorghum fields allows for rotational grazing systems, preventing livestock from feeding on high-risk sorghum at vulnerable growth stages. Trees also support biodiversity and soil health, which in turn improves the resilience of farming systems. Empirical studies have shown that agroforestry not only enhances fodder diversity but also stabilizes livestock productivity and reduces poisoning incidents (Franzel et al., 2014). Agroforestry therefore represents a practical, low-cost, and ecologically sustainable approach to managing sorghum toxicity.

Agroforestry trees possess phytoremediation potential that can be harnessed to mitigate sorghum poisoning by reducing soil and environmental cyanide levels. Trees such as Eucalyptus camaldulensis, Populus deltoides, and Cassia siamea have been shown to absorb cyanide through their roots and metabolize it via internal detoxification mechanisms (Nielsen et al., 2008). These species release enzymes such as nitrilases and sulfurtransferases, which help transform cyanide into harmless compounds like thiocyanate and formamide (Ebbs, 2004). Integrating such trees into sorghum fields creates a buffer system that can intercept and neutralize excess cyanide released from decaying plant matter or contaminated runoff. Agroforestry systems also enhance phytoremediation efficiency through improved soil aeration, moisture regulation, and microbial synergy (Verma et al., 2021). Additionally, these trees contribute to ecosystem services such as carbon sequestration and biodiversity enhancement. Strategic tree placement, for example, planting along field margins or intercropping with low-root-competition species—can maximize phytoremediation benefits without compromising sorghum yields. Regular monitoring of soil cyanide levels and selecting region-specific tree species are key to optimizing this approach. Phytoremediation through agroforestry provides a sustainable and ecologically sound method for mitigating the environmental risks of sorghum toxicity. Agroforestry systems incorporating nitrogen-fixing trees like Leucaena leucocephala lower plant stress and dhurrin production while providing alternative fodder (Sileshi et al., 2014; Franzel et al., 2014).

Table 2.

Major agroforestry tree species for mitigating sorghum poisoning and their complementary benefits.

Table 2.

Major agroforestry tree species for mitigating sorghum poisoning and their complementary benefits.

| Tree Species |

Primary Mitigation Function |

Additional Benefits |

References |

| Leucaena leucocephala |

Nitrogen fixation; High-quality alternative fodder |

Soil improvement; Fuelwood |

Franzel et al., 2014 |

| Gliricidia sepium |

Nitrogen fixation; Shade (stress reduction) |

Livestock feed; Soil fertility |

Sileshi et al., 2014 |

| Sesbania sesban |

Rapid N-fixation; Fodder |

Green manure; Soil reclamation |

Garrity, 2004 |

| Eucalyptus camaldulensis |

Phytoremediation (cyanide uptake) |

Windbreak; Timber; Poles |

Nielsen et al., 2008; Verma et al., 2021 |

| Moringa oleifera |

Highly nutritious, low-HCN fodder |

Human food; Medicinal uses |

Leng, 2008

|

| Faidherbia albida |

Reverse phenology (fodder in dry season) |

Soil fertility improvement |

Jose, 2009 |

2.2. Role of Soil Microbiota in Cyanide Detoxification

Soil microbial communities play a pivotal role in detoxifying hydrogen cyanide (HCN), a toxic byproduct of dhurrin hydrolysis in sorghum. Microorganisms such as Pseudomonas fluorescens and Bacillus pumilus possess enzymes like cyanide hydratase and rhodanese that convert HCN into less toxic substances like ammonia and formate (Knowles, 1976; Ebbs, 2004). Agroforestry systems enhance soil organic matter and moisture, promoting microbial diversity and activity. For example, leguminous trees such as Gliricidia sepium increase microbial abundance in the rhizosphere, indirectly supporting cyanide biodegradation (Sanginga et al., 1995). Studies reveal that agroforestry soils show a 30–40% higher rate of cyanide degradation compared to monocropped soils (Castrillo et al., 2017). Additionally, leaf litter and root exudates from agroforestry trees serve as energy sources for these microbes. Therefore, integrating sorghum cultivation with trees not only improves overall soil health but also mitigates toxicity through enhanced microbial remediation. Future research should focus on identifying optimal tree-microbe combinations for specific agro-climatic zones to maximize detoxification potential. Overall, supporting soil microbial ecology through agroforestry is a sustainable and low-cost strategy for managing sorghum-related poisoning in agricultural systems. Soil microbes (Pseudomonas fluorescens) and phytoremediation trees (Eucalyptus camaldulensis) can also degrade cyanide in the environment (Ebbs, 2004; Nielsen et al., 2008).

2.3. Genetic Improvement and Low-Dhurrin Sorghum Varieties

Reducing dhurrin content through genetic improvement is a practical approach to minimize cyanide toxicity in sorghum. Conventional breeding and molecular biotechnology have led to the development of sorghum varieties with reduced or delayed dhurrin synthesis. Gene editing techniques like CRISPR-Cas9 target genes such as CYP79A1 and CYP71E1, which encode enzymes essential for dhurrin biosynthesis (Blomstedt et al., 2012; Takos et al., 2011). By downregulating or knocking out these genes, researchers have created cultivars that accumulate less cyanogenic glycoside even under drought stress. Varieties like ‘Superdan 2’ and ‘TX7078’ exhibit lower HCN levels while maintaining acceptable agronomic performance (Hayes et al., 2015). Marker-assisted selection also accelerates the development of low-dhurrin sorghum by identifying and tracking desirable alleles (Muturi et al., 2020). These genetically improved varieties can be incorporated into agroforestry systems where they coexist with trees that provide shade and reduce environmental stress, further lowering dhurrin expression. However, regulatory hurdles and public acceptance of genetically modified crops remain barriers. Promoting awareness and ensuring biosafety compliance are essential for the successful adoption of these varieties. Combining genetic improvement with agroforestry practices offers a synergistic solution to reduce toxicity and enhance sustainability in sorghum-based farming systems. Breeding low-dhurrin varieties (e.g., 'TX7078') through conventional or CRISPR-based methods offers a long-term solution (Blomstedt et al., 2012; Hayes et al., 2015).

2.4. Livestock Management and Feed Strategies

Managing livestock feeding practices is vital for reducing the risk of sorghum-induced cyanide poisoning. Cyanide levels in sorghum forage vary with plant maturity, environmental stress, and processing methods (Pande et al., 2002). Feeding livestock immature sorghum or stressed plants can result in acute toxicity. To minimize risk, farmers should delay grazing until the crop matures and wilt or ensile sorghum fodder before feeding. Ensiling promotes microbial breakdown of dhurrin and HCN (Omer et al., 2014). Another effective method involves dietary supplementation with sulfur-containing compounds like sodium thiosulfate, which facilitates conversion of HCN into non-toxic thiocyanate in animal tissues (Olafadehan, 2011). Incorporating low-HCN forage crops such as Moringa oleifera, Stylosanthes spp., or maize stover into diets dilutes toxin levels (Leng, 2008). Agroforestry enhances feed diversity by providing tree leaves and pods rich in protein and low in cyanide. Species like Leucaena leucocephala and Albizia lebbeck serve as excellent supplementary fodder (Paterson et al., 1995). Farmer training on fodder management, proper harvesting, and feeding protocols can drastically reduce livestock morbidity and mortality. An integrated approach combining safe feeding practices and agroforestry fodder resources is essential for sustainable livestock production in sorghum-growing regions. Feed management techniques such as wilting or ensiling sorghum reduce HCN levels by up to 50% (Omer et al., 2014), while sulfur supplements (e.g., sodium thiosulfate) aid detoxification (Olafadehan, 2011).

Table 3.

Effective management strategies for reducing cyanogenic potential (HCN-p) and preventing sorghum poisoning in livestock.

Table 3.

Effective management strategies for reducing cyanogenic potential (HCN-p) and preventing sorghum poisoning in livestock.

| Management Practices |

Efficacy & Notes |

References |

| Wilting |

Cut and allow to dry in sunlight for 24–48 hours. Reduces HCN concentration by 25–40%, though efficiency is weather dependent. |

Omer et al., 2014

|

| Ensiling |

Anaerobic fermentation in a silo or pit for at least four weeks. Reduces HCN by 50–60% and is considered the most reliable method. |

Omer et al., 2014

|

| Dilution |

Mix high-risk sorghum material with other safe forages to minimize toxicity. Ensures a more balanced diet. |

Leng, 2008 |

| Sulfur Supplementation |

Provide salt licks or feed supplemented with sodium thiosulfate. Supports the animal’s natural detoxification mechanism. |

Olafadehan, 2011 |

3. Implementation, Outreach, and Socioeconomic Dimensions

The successful implementation of technical solutions depends critically on human and systemic factors. This part explores the educational, indigenous, socioeconomic, and policy dimensions essential for translating strategy into practice.

3.1. Educational Outreach and Farmer Training

Educational outreach is crucial in preventing sorghum poisoning, especially in rural communities where awareness is limited. Training programs can inform farmers about factors influencing cyanide accumulation, such as plant maturity, drought stress, and improper storage (Garrity et al., 2010). These programs should include hands-on sessions demonstrating safe harvesting, drying, and processing methods. Agroforestry-related training should highlight how trees can enhance soil quality, reduce plant stress, and provide alternative fodder and fuel sources (Franzel et al., 2002). Successful outreach models include community-based farmer field schools, radio broadcasts, mobile apps, and pictorial guides for illiterate farmers. In Kenya and Ethiopia, participatory learning approaches have increased farmer adoption of agroforestry practices and reduced cases of livestock poisoning (Place et al., 2012). Collaboration with local extension agents and NGOs ensures culturally appropriate and linguistically accessible content. Training should also target youth and women, who play key roles in household farming activities. Establishing demonstration plots where farmers can observe and replicate best practices enhances impact. In the long term, integrating sorghum safety and agroforestry principles into agricultural curricula can institutionalize knowledge dissemination. Educational outreach empowers communities to implement preventive measures, making farming safer and more productive. Farmer education on high-risk conditions and testing for HCN levels is critical for prevention (Garrity et al., 2010)

3.2. Ethnoveterinary and Indigenous Knowledge

In many sorghum-growing areas, traditional knowledge systems play a vital role in managing livestock poisoning. Indigenous communities have long used medicinal plants, specific grazing strategies, and seasonal cues to reduce the risk of cyanide toxicity (Ayeni et al., 2015). Ethnoveterinary practices such as feeding livestock charcoal, certain tree barks (e.g., Acacia nilotica), or clay-rich soils are believed to bind or neutralize toxins (Njoroge & Bussmann, 2006). While often dismissed, these approaches offer valuable insights for localized, low-cost interventions. Agroforestry practices, too, have roots in indigenous land management, such as the use of Faidherbia albida for soil fertility and fodder. Documenting, validating, and integrating these knowledge systems into formal training and research can enhance the relevance and adoption of remedies. Collaborations with traditional healers, elders, and community leaders should be pursued as participatory action research.

3.3. Socioeconomic Impacts and Policy Support

Sorghum poisoning not only affects livestock productivity but also has far-reaching economic and social consequences, especially in subsistence farming communities. Livestock losses due to acute cyanide toxicity can drastically reduce household income, food security, and access to manure—a key input in smallholder systems (FAO, 2020). The costs associated with veterinary care, animal replacement, and lost labor further deepen rural poverty cycles. In pastoral societies, the loss of animals affects cultural and social status. Women, who often manage fodder and feeding, bear the brunt of sorghum toxicity due to limited access to training and veterinary resources (Kristjanson et al., 2004). Thus, the issue transcends agronomy and enters the realm of rural development and gender equity. Agroforestry interventions, which provide diversified fodder and alternative incomes (e.g., fuelwood, fruits), can buffer households from these shocks. Integrating economic modeling and gender-sensitive impact assessments into sorghum management research is essential. Holistic intervention strategies must consider how poisoning influences rural livelihoods and prioritize inclusive, low-cost solutions.

Policy frameworks that promote agroforestry can play a critical role in mitigating sorghum poisoning risks. Countries like India, Kenya, and Brazil have integrated agroforestry into national agricultural plans, recognizing its potential for environmental sustainability and food security (ICRAF, 2022). However, policy gaps remain regarding cyanide toxicity mitigation. Institutional support is needed for seed distribution of low-dhurrin varieties, extension services for training, and subsidies for fodder trees. Regulatory frameworks for genetically improved sorghum must also balance innovation with biosafety and farmer rights (OECD, 2015). Agroforestry adoption could be incentivized through carbon credits, land tenure reforms, and inclusion in climate adaptation programs (World Bank, 2019). Multi-level governance involving local authorities, farmer cooperatives, and national bodies is vital for scale-up. Ensuring that agroforestry and sorghum safety are embedded into agricultural, health, and environmental policies will enhance program coordination and long-term impact.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, sorghum is a staple fodder crop but often coincides with high livestock poisoning incidents during drought periods. Countries like Nigeria, Ethiopia, and Sudan report seasonal livestock mortality spikes linked to immature or wilted sorghum (Ademosun, 2002). Similarly, in India’s semi-arid tropics, cyanide-related cattle deaths are common in states like Maharashtra and Karnataka, particularly after unseasonal rains (Rao et al., 2010). These cases highlight the need for region-specific interventions. For example, in Ethiopia, Farmer Field Schools have successfully introduced agroforestry-based mitigation strategies combining Gliricidia, Sesbania, and improved forage mixes (Place et al., 2012). Case studies can guide localized policy, training design, and variety selection. They also underscore the value of integrating farmer voices in developing solutions. Mapping regional risk profiles and correlating them with climate, cultural, and agronomic data could vastly improve targeted interventions.

4. Future Perspectives and Conclusions

Looking forward, this final part considers the evolving challenge of sorghum poisoning in the context of climate change and underscores the necessity of integrative, multidisciplinary collaboration for sustainable solutions.

4.1. Climate Change and Future Risk Assessment

Climate change is likely to exacerbate the risk of sorghum poisoning by altering plant physiology and increasing dhurrin synthesis (IPCC, 2021). Higher temperatures, irregular rainfall, and prolonged droughts—conditions expected to become more common—are known triggers for increased cyanogenic glycoside accumulation (Gleadow & Møller, 2014). Under stress, sorghum plants produce more dhurrin as a defense mechanism, thereby raising the risk of hydrogen cyanide poisoning in livestock and humans. Predictive models suggest that sorghum toxicity could increase by up to 25% in some regions by 2050 (Jones et al., 2019). Agroforestry systems act as buffers against climatic stress by improving microclimatic conditions, enhancing soil moisture retention, and reducing temperature extremes (Mbow et al., 2014). Trees also act as windbreaks, reduce evapotranspiration, and support a more resilient cropping environment. Integrating resilient crop varieties and climate-smart agroforestry practices is essential for adaptation. Risk assessment tools that combine remote sensing, weather forecasting, and AI-driven modeling can help farmers and policymakers anticipate and respond to toxicity threats. Proactive climate adaptation through agroforestry not only reduces sorghum poisoning risk but also contributes to broader environmental sustainability goals.

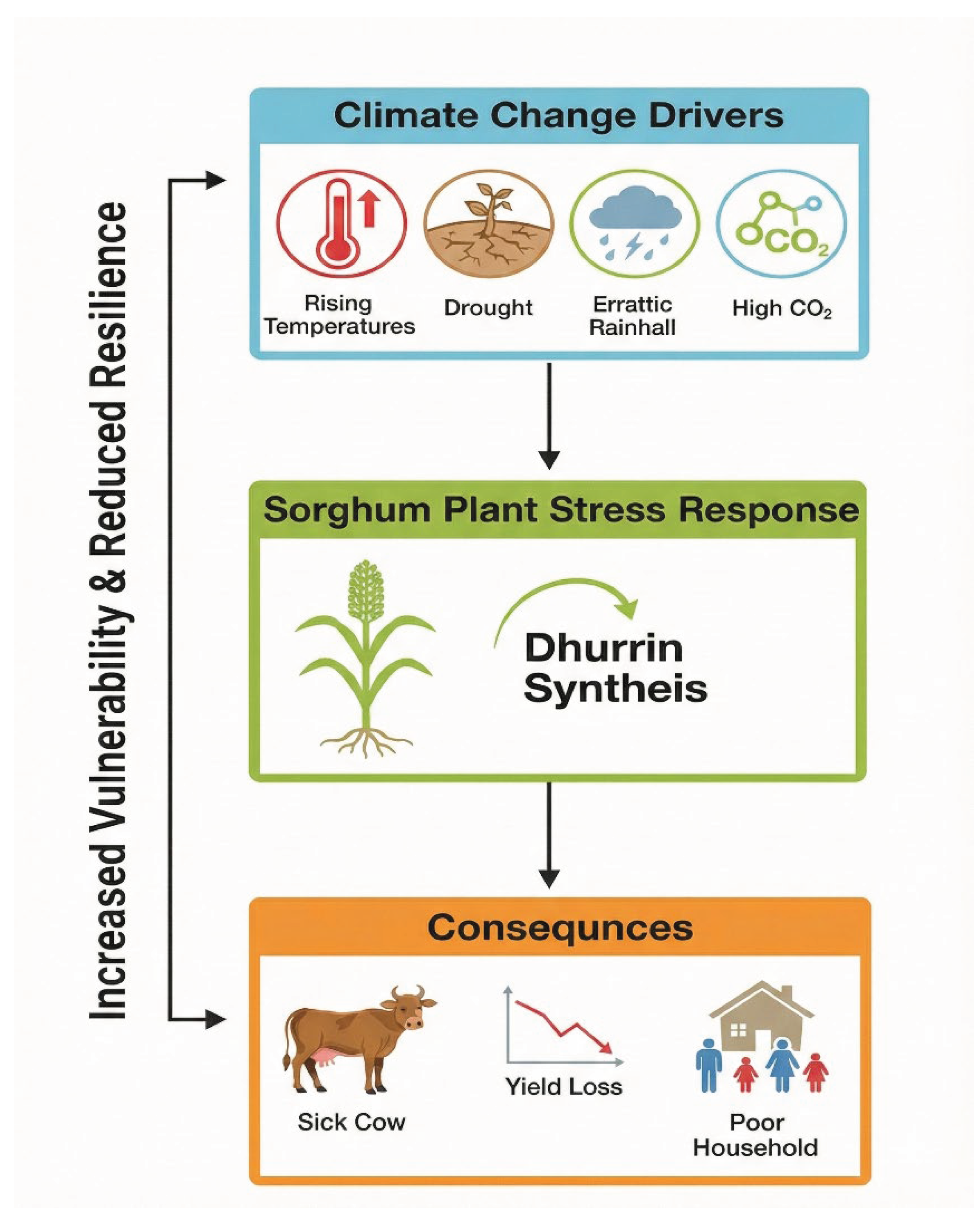

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of the feedback loop between climate change factors and the increased risk of sorghum poisoning. Projected climate changes act as abiotic stressors, upregulating dhurrin synthesis in sorghum. This increases the threat to livestock, thereby exacerbating socioeconomic vulnerabilities and creating a positive feedback loop that challenges sustainable agriculture. (Based on IPCC, 2021; Gleadow & Møller, 2014). (Created in biorender.com).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of the feedback loop between climate change factors and the increased risk of sorghum poisoning. Projected climate changes act as abiotic stressors, upregulating dhurrin synthesis in sorghum. This increases the threat to livestock, thereby exacerbating socioeconomic vulnerabilities and creating a positive feedback loop that challenges sustainable agriculture. (Based on IPCC, 2021; Gleadow & Møller, 2014). (Created in biorender.com).

4.2. Integrative Research and Multidisciplinary Collaboration

Addressing sorghum poisoning requires a multidisciplinary approach involving plant scientists, animal nutritionists, ecologists, social scientists, and policymakers. Integrative research can lead to the development of context-specific solutions that are scientifically sound and socially acceptable (Pretty et al., 2010). Collaborative projects between universities, NGOs, and governmental agencies can focus on identifying low-dhurrin cultivars, effective tree-crop combinations, and safe livestock management practices (Leakey, 2012). Establishing platforms for data sharing, open-access databases, and regional knowledge hubs can enhance transparency and accelerate innovation. Citizen science initiatives can engage farmers in monitoring toxicity symptoms and reporting cases, creating feedback loops for adaptive management (van Vliet et al., 2015). Multidisciplinary workshops and conferences can foster dialogue among stakeholders and align research agendas with community needs. Policy frameworks should support integrated land use and provide incentives for agroforestry adoption. Investment in capacity building and infrastructure is also vital. Ultimately, a systems-thinking approach that considers environmental, economic, and social dimensions will be key to sustainably managing sorghum toxicity. Interdisciplinary collaboration ensures that solutions are holistic, scalable, and adaptable to changing conditions.

4.3. Conclusions

Sorghum poisoning remains a significant concern in livestock production systems, particularly in regions with poor pasture management or harsh environmental conditions. The presence of dhurrin and its conversion to toxic hydrogen cyanide under stress or damage makes certain growth stages of sorghum particularly hazardous. Recognizing the environmental and agronomic factors influencing toxicity is key to developing effective prevention strategies. Agroforestry presents a promising, sustainable solution that mitigates environmental stress, improves forage diversity, and reduces dependence on chemical inputs. By integrating trees with crops and livestock systems, farmers can build resilience in their operations and reduce the risk of livestock poisoning. Future research should focus on optimizing tree-crop-livestock configurations, monitoring dhurrin levels under different agroforestry systems, and developing farmer-centric guidelines for safe sorghum utilization. Integrated approaches combining agroforestry, improved feeding practices, genetic resistance, and microbial remediation provide sustainable solutions to protect livestock health while maintaining sorghum's agricultural value.

Author Contributions

Mahmud Sindid Ikram designed the study, collected and analyzed the data, interpreted the results, and contributed to the writing of the report. Sumiya Akter Moni supervised the study, participated in data analysis, and reviewed and corrected the manuscript.

Funding

There were no funds secured for this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ademosun, A.A. Livestock poisoning from cyanogenic sorghum in Nigeria: A review. Tropical Animal Health and Production 2002, 34, 231–238. [Google Scholar]

- Ayeni, J.S.; Majekodunmi, A.O.; Donga, T.K. Ethnoveterinary practices in the management of sorghum poisoning among Fulani pastoralists in Nigeria. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 2015, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Blomstedt, C.K.; Gleadow, R.M.; O'Donnell, N.; Naur, P.; Jensen, K.; Laursen, T.; Møller, B.L. A combined biochemical screen and TILLING approach identifies mutations in Sorghum bicolor L. Moench resulting in acyanogenic forage production. Plant Biotechnology Journal 2012, 10, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busk, P.K.; Møller, B.L. Dhurrin synthesis in sorghum is regulated at the transcriptional level and induced by nitrogen fertilization in older plants. Plant Physiology 2002, 129, 1222–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castrillo, G.; Teixeira, P.J.; Paredes, S.H.; Law, T.F.; de Lorenzo, L.; Feltcher, M.E.; Dangl, J.L. Root microbiota drive direct integration of phosphate stress and immunity. Nature 2017, 543, 513–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conn, E.E. Cyanogenic glycosides: Their occurrence, biosynthesis, and function. Phytochemistry 2008, 69, 2967–2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebbs, S. Biological degradation of cyanide compounds. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 2004, 15, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2020; FAO, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Franzel, S.; Carsan, S.; Lukuyu, B.; Sinja, J.; Wambugu, C. Fodder trees for improving livestock productivity and smallholder livelihoods in Africa. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 2014, 6, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrity, D.P. Agroforestry and the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals. Agroforestry Systems 2004, 61, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleadow, R.M.; Møller, B.L. Cyanogenic glycosides: Synthesis, physiology, and phenotypic plasticity. Annual Review of Plant Biology 2014, 65, 155–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, C.M.; Weers, B.D.; Thakran, M.; Burow, G.B.; Xin, Z. Discovery of a dhurrin QTL in sorghum: Co-localization with dhurrin biosynthesis genes. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 2015, 128, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate change 2021: The physical science basis; Cambridge University Press, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jose, S. Agroforestry for ecosystem services and environmental benefits: An overview. Agroforestry Systems 2009, 76, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, C.J. Microorganisms and cyanide. Bacteriological Reviews 1976, 40, 652–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, R.L.; Morris, D.R.; Mikkelsen, R.L. Cyanide toxicity and sorghum forage: A review. Journal of Animal Science 1999, 77, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Kristjanson, P.; Place, F.; Franzel, S.; Thornton, P.K. Research on agroforestry systems and poverty alleviation: Evidence to date; World Agroforestry Centre, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Leakey, R.R. Multifunctional agriculture and opportunities for agroforestry. Agroforestry Systems 2012, 85, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, R.A. Tree foliage in ruminant nutrition. In FAO Animal Production and Health Paper No. 139; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Majak, W.; McDiarmid, R.E.; Bose, R.J. Cyanide concentrations in sorghum as affected by growth stage and nitrogen fertilization. Journal of Range Management 2003, 56, 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- McLennan, M.W.; Thompson, D.J.; Nielsen, B.L. Cyanide poisoning in ruminants from sorghum forage: A review. Australian Veterinary Journal 2008, 86, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.E.; Reagor, J.C.; Pfister, J.A. Cyanide in sorghum: Effects of drought and nitrogen. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2011, 59, 4284–4287. [Google Scholar]

- Muturi, P.W.; Mgonja, M.; Rubaihayo, P.; Kibuka, J. Marker-assisted breeding for low dhurrin sorghum varieties in East Africa. Crop Science 2020, 60, 1234–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, L.P.; Risgaard-Petersen, N.; Fossing, H.; Christensen, P.B.; Sayama, M. Electric currents couple spatially separated biogeochemical processes in marine sediment. Nature 2008, 463, 1071–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Njoroge, G.N.; Bussmann, R.W. Ethnoveterinary practices in Kenya: A review. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 2006, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olafadehan, O.A. Detoxification of cyanide in ruminants: Role of sulfur. Toxicology Reports 2011, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Omer, H.A.; Abdel-Magid, S.S.; Awadalla, I.M. Ensiling as a method to reduce cyanide in sorghum forage. Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition 2014, 98, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Safety assessment of transgenic organisms in the environment; OECD Publishing, 2015; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Pande, M.B.; Taley, R.S.; Kulkarni, S.A. Cyanogenic potential of sorghum at different growth stages. Indian Journal of Animal Sciences 2002, 72, 412–415. [Google Scholar]

- Paterson, R.T.; Karanja, G.M.; Nyaata, O.Z.; Kariuki, I.W.; Roothaert, R.L. The use of tree fodder as a feed for ruminants in Kenya. In International Centre for Research in Agroforestry; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Poulton, J.E. Cyanogenesis in plants. Plant Physiology 1990, 94, 401–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pretty, J.; Toulmin, C.; Williams, S. Sustainable intensification in African agriculture. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability 2010, 8, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P.P.; Birthal, P.S.; Kar, D. Sorghum poisoning in cattle: A case study from India. Tropical Animal Health and Production 2010, 42, 1237–1241. [Google Scholar]

- Sanginga, N.; Danso, S.K.; Zapata, F. Nitrogen fixation in trees and soil microbial activity in agroforestry systems. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 1995, 27, 785–793. [Google Scholar]

- Sileshi, G.W.; Akinnifesi, F.K.; Ajayi, O.C.; Place, F. Agroforestry for sustainable land use in Africa. Ecological Engineering 2014, 64, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takos, A.M.; Knudsen, C.; Lai, D.; Kannangara, R.; Mikkelsen, L.; Motawia, M.S.; Møller, B.L. Genomic clustering of cyanogenic glucoside biosynthetic genes aids their identification in Lotus japonicus and suggests the repeated evolution of this chemical defence pathway. The Plant Journal 2011, 68, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Vliet, J.A.; Schut, A.G.; Reidsma, P.; Descheemaeker, K.; Slingerland, M.; van de Ven, G.W. De-mystifying family farming: Features, diversity and trends across the globe. Global Food Security 2015, 5, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, J.P.; Jaiswal, D.K.; Sagar, R. Phytoremediation of cyanide-contaminated soils: Current status and future prospects. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2021, 28, 14233–14248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Agroforestry for landscape restoration and livelihoods; World Bank Publications, 2019. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).