Submitted:

11 December 2025

Posted:

12 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

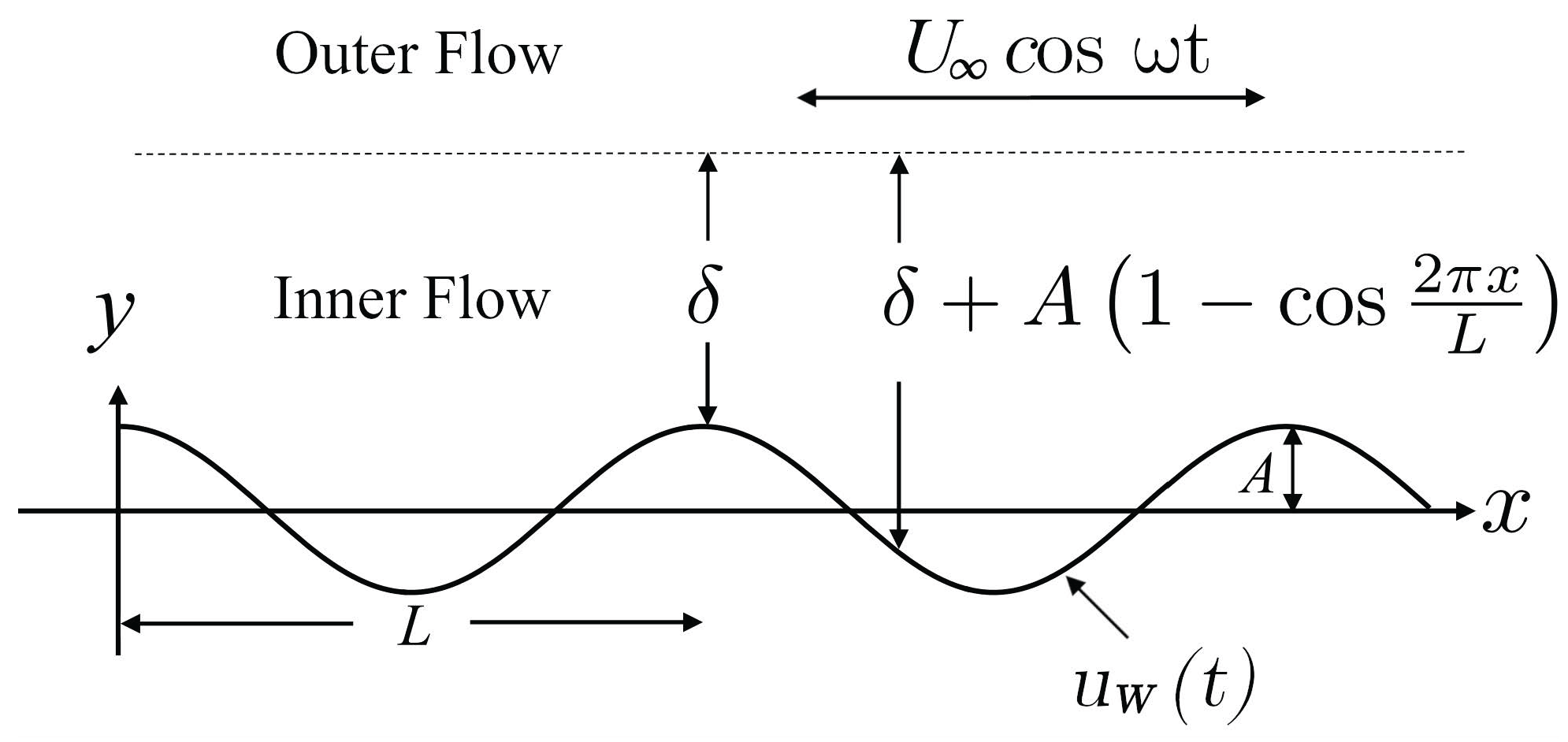

2. Formulation of the Problem

3. Perturbation Solution

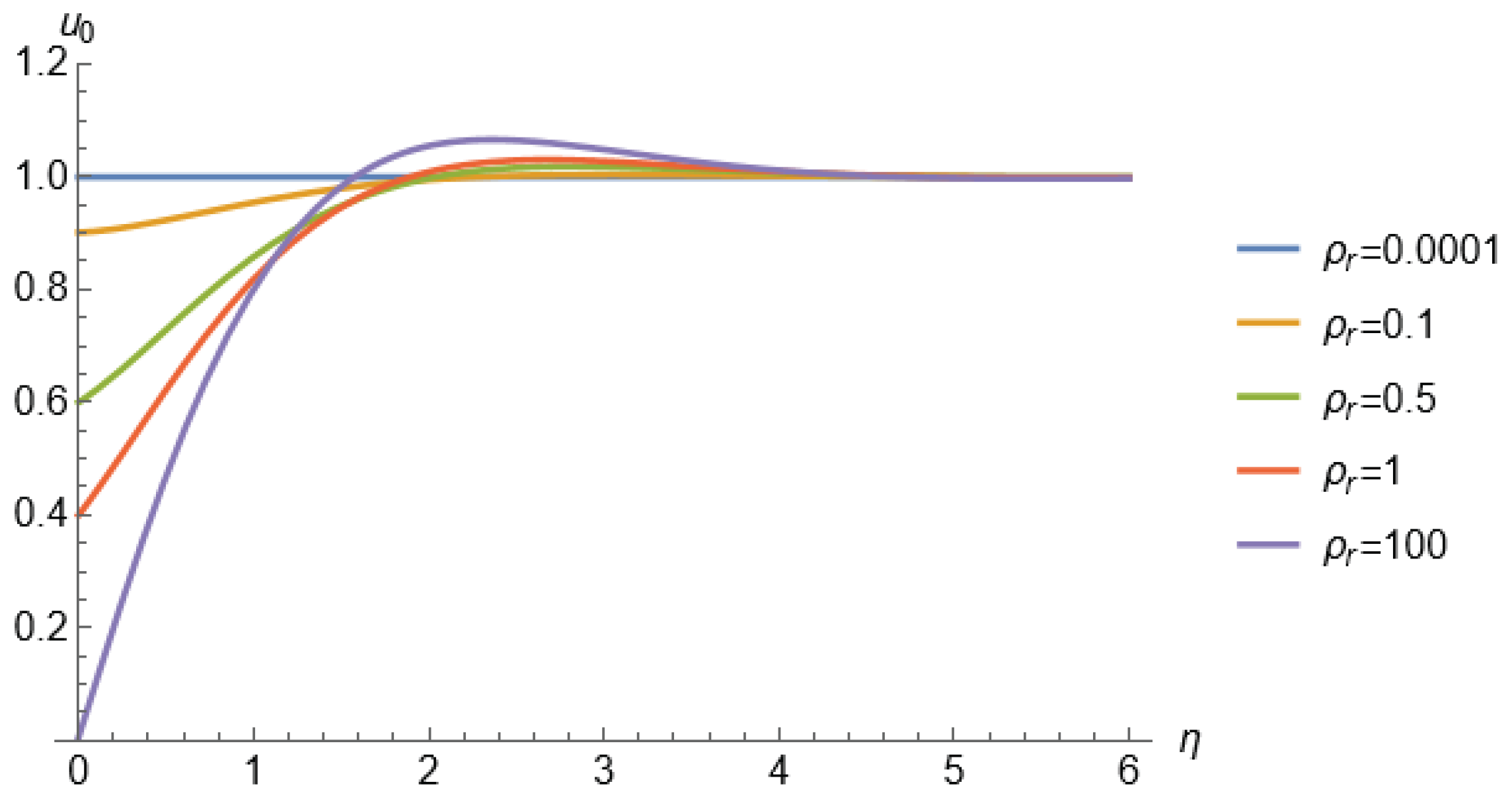

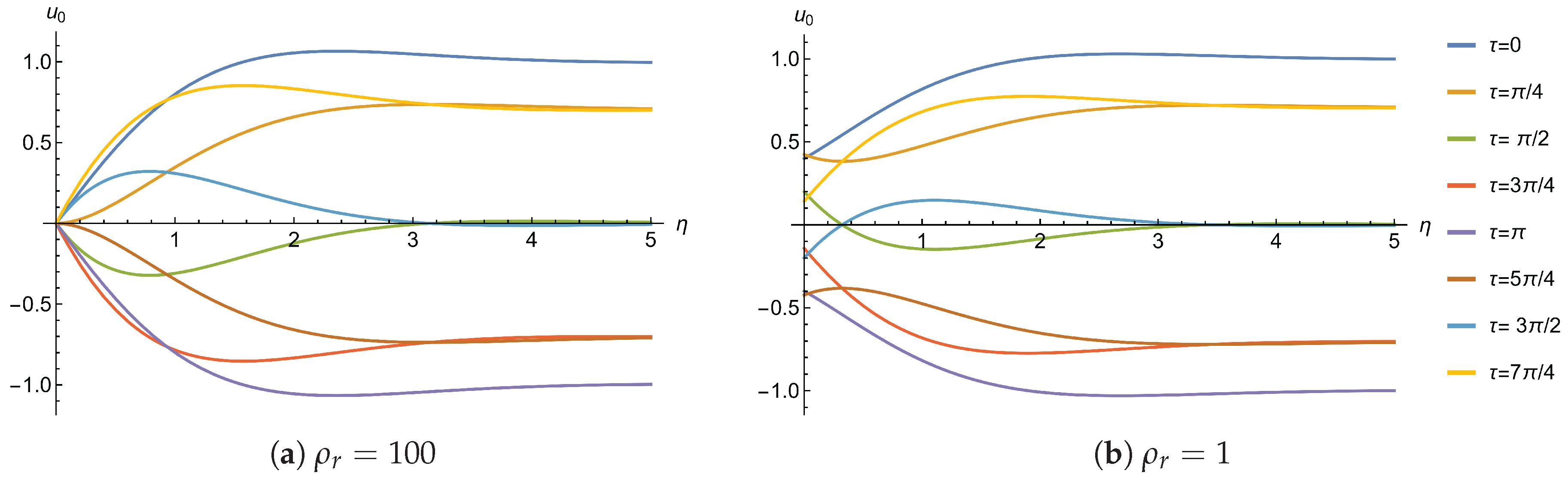

3.1. First Order Approximation

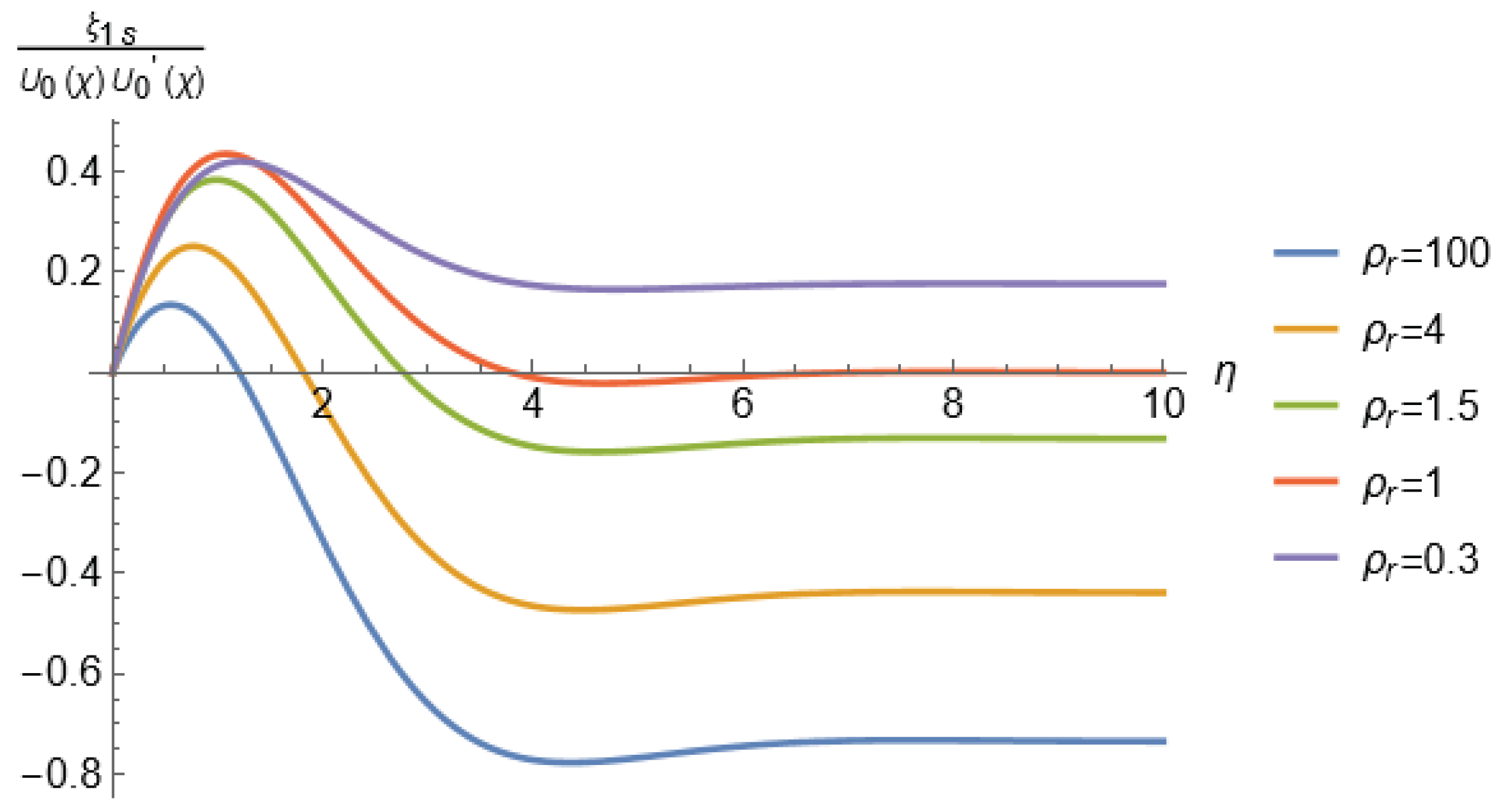

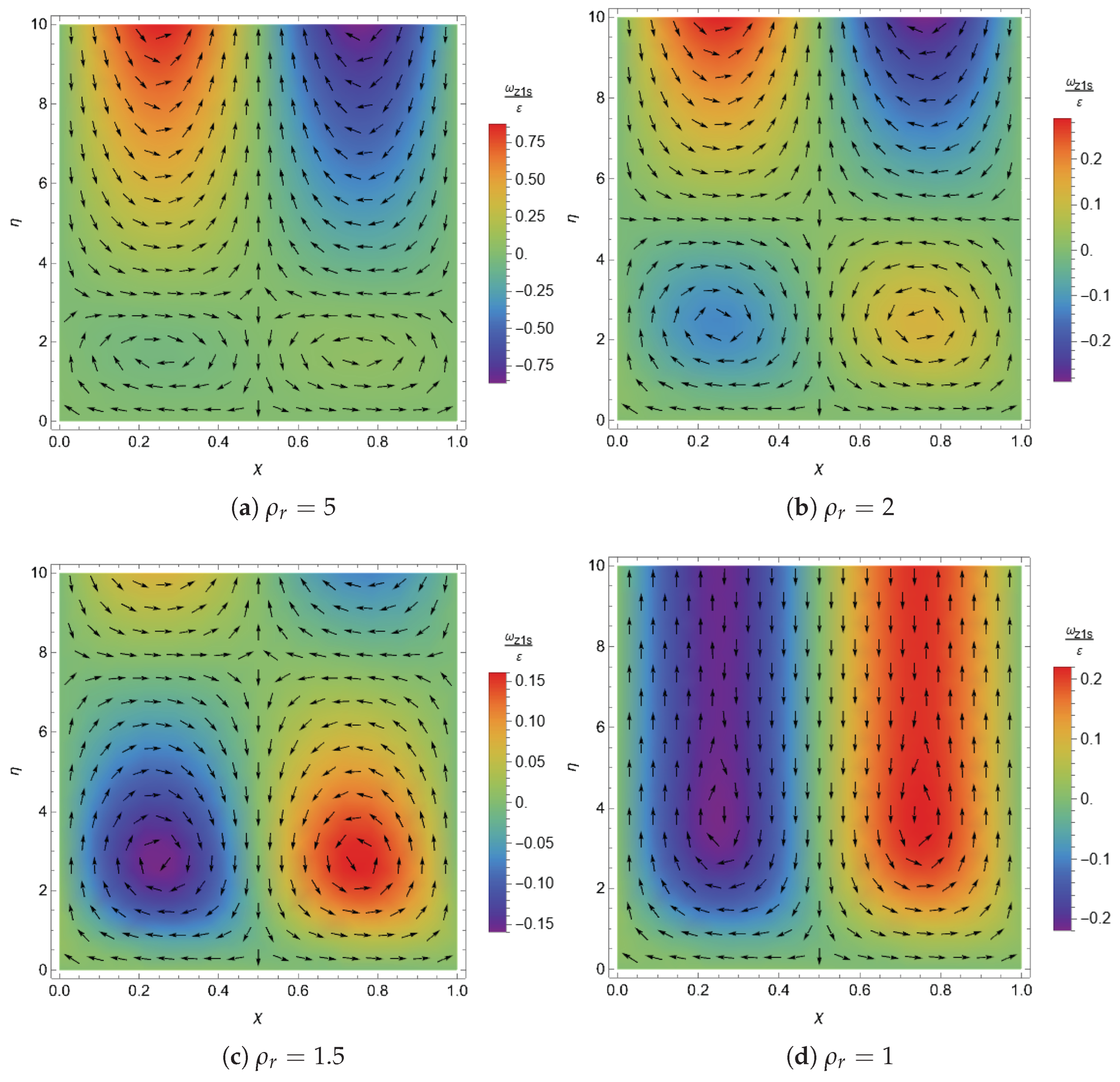

3.2. Second Order Approximation

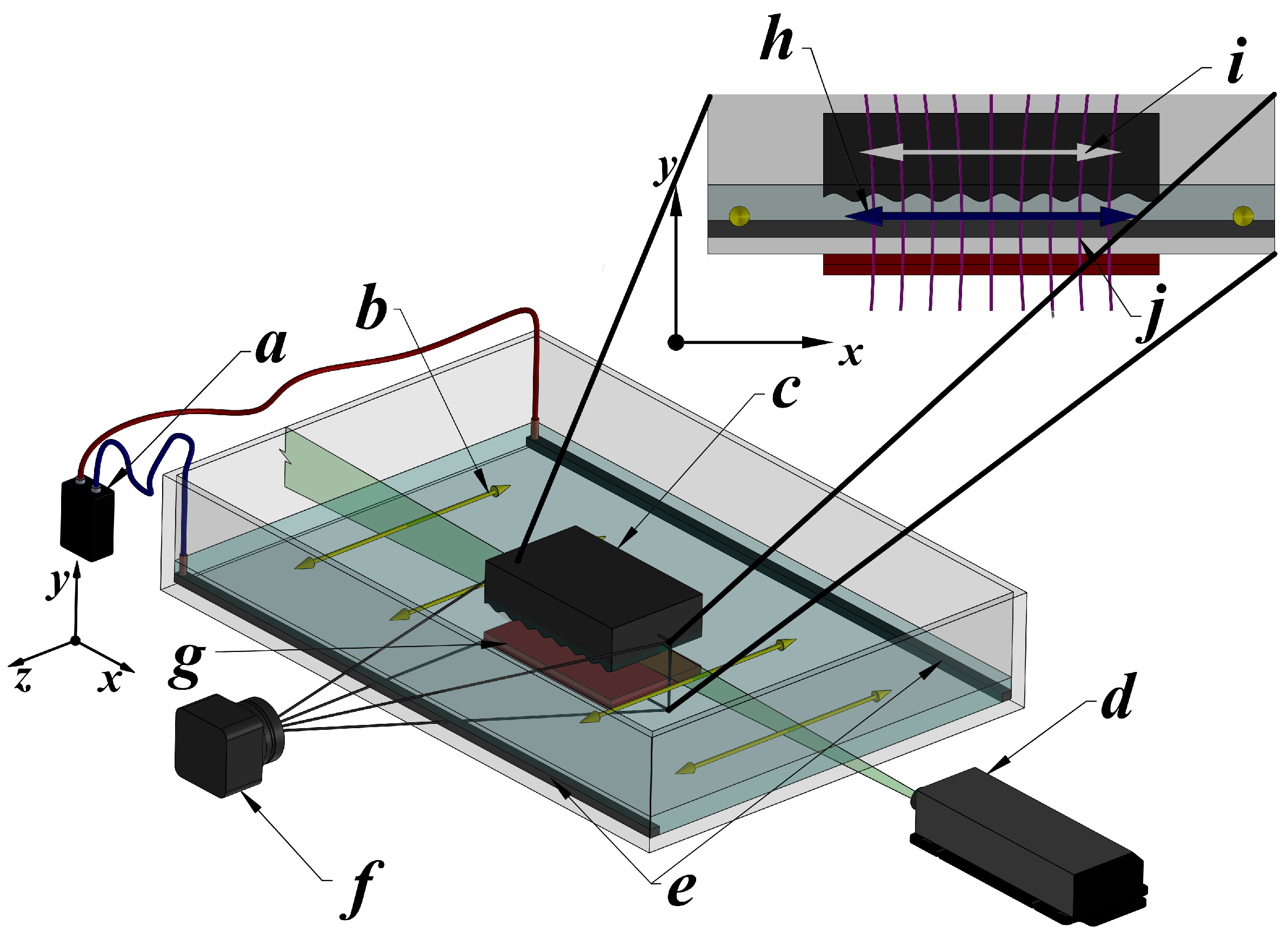

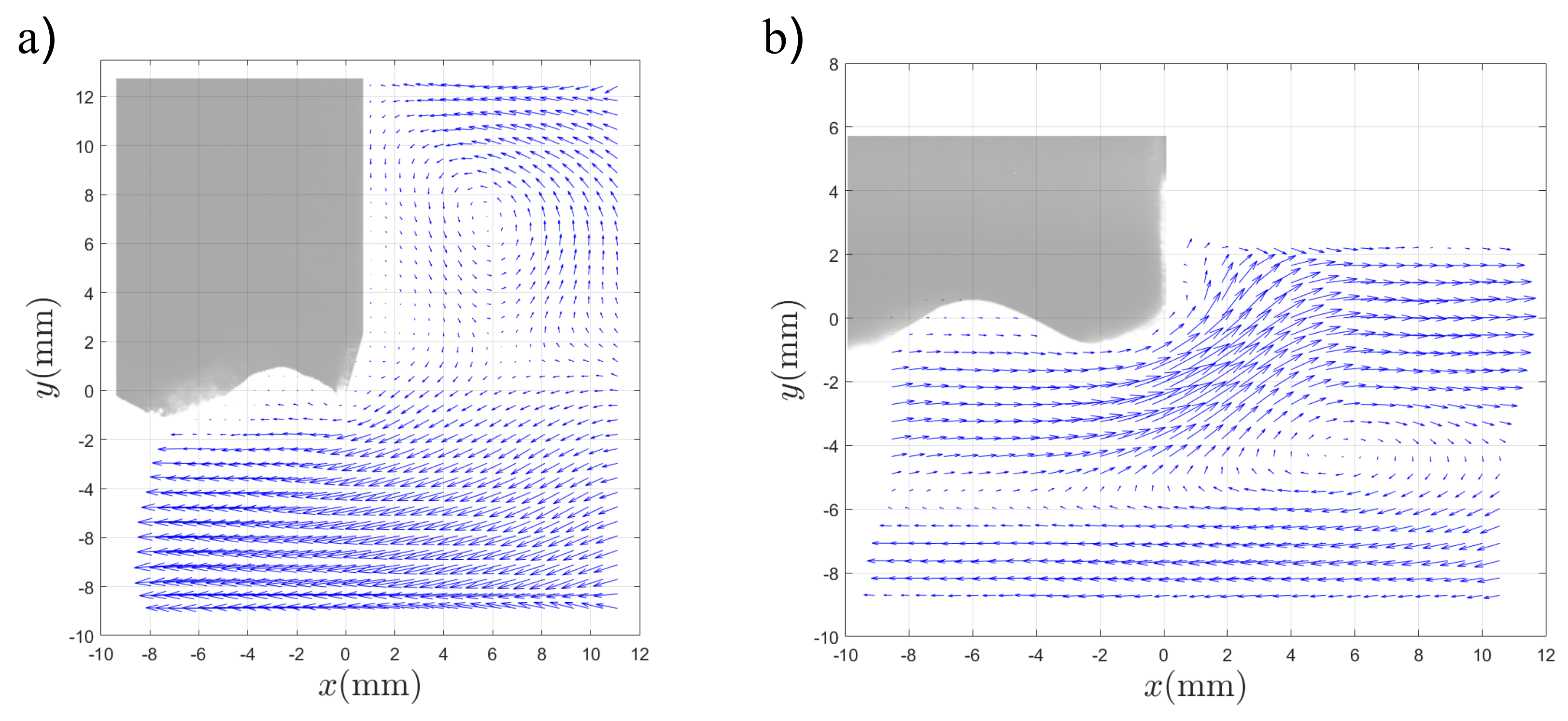

4. Experiments

5. Discussion and Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kumar, H.; Tawhai, M.; Hoffman, E.; Lin, C.L. Steady streaming: A key mixing mechanism in low-Reynolds-number acinar flows. Phys. Fluids 2011, 23, 041902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez, A.; Martínez-Bazán, C.; Gutiérrez-Montes, C.; Criado-Hidalgo, E.; Pawlak, G.; Bradley, W.; Haughton, V.; Lasheras, J.C. On the bulk motion of the cerebrospinal fluid in the spinal canal. J. Fluid Mech. 2018, 841, 203–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blondeaux, P. Sand ripples under sea waves Part 1. Ripple formation. J. Fluid Mech. 1990, 218, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, D.; Horrillo-Caraballo, J.; Karunarathna, H. The shape and residual flow interaction of tidal oscillations. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 2022, 276, 108023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurzweg, U.H. Enhanced heat conduction in oscillating viscous flows within parallel-plate channels. J. Fluid Mech. 1985, 156, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, A.; Cuevas, S.; del Río, J.; López de Haro, M. Heat transfer enhancement in oscillatory flows of Newtonian and viscoelastic fluids. Int. J. Heat Mass Transfer 2009, 52, 5472–5478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, G.G. On the Effect of the Internal Friction of Fluids on the Motion of Pendulum. Trans. Cambridge Phil. Soc. 1851, 9, 8–106. [Google Scholar]

- Telionis, D.P. Unsteady viscous flows; Springer-Verlag: New York, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Riley, N. Steady Streaming. Ann. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2001, 33, 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, J.T. Double boundary layers in oscillatory viscous flows. J. Fluid Mech. 1966, 24, 673–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayleigh, L. On the circulations of air observed in Kundt’s tubes and or some allied acoustical problems. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A 1884, 175, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Schlichting, H. Berechnung ebner periodischer Grenzschichtstromungen. Physikalische Zeitschrift 1932, 33, 327. [Google Scholar]

- Schlichting, H. Boundary Layer Theory, seventh ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, 1979; pp. 428–432. [Google Scholar]

- Bertelsen, A.F. An experimentalinvestigation of high Reynolds number steady streaming generated by oscillating cylinders. J. Fluid Mech. 1974, 64, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, N. The steady streaming induced by a vibrating cylinder. J. Fluid Mech. 1975, 68, 801–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, N. On a sphere oscillating in a viscous fluid. Q. J. Mech. Appl.Maths. 1966, 19, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohara, N. The unsteady flow around an oscillating sphere in a viscous fluid. J. Phys. Soc. Japan 1982, 51, 4095–4103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopinath, A. Steady streaming due to small amplitude torsional oscillations of a sphere in a viscous fluid. Q. J. Mech. Appl. Maths. 1993, 46, 501–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sritharan, K.; Strobl, C.; Schneider, M.; Wixforth, A.; Guttenberg, Z. Acoustic mixing at low Reynolds numbers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006, 88, 054102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, D.; Mao, X.; Shi, J.; Juluri, B.K.; Huang, T.J. A millisecond micromixer via single-bubble-based acoustic streaming. Lab Chip 2009, 9, 2738–2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Minten, J.; Rallabandi, B. Particle hydrodynamics in acoustic fields: Unifying acoustophoresis with streaming. Phys. Rev. Fluids 2024, 9, 044303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Nunn, A.R.; Brumley, D.R.; Sader, J.E.; Collis, J.F. The propulsion direction of nanoparticles trapped in an acoustic field. J. Fluid Mech. 2024, 984, R1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thameem, R.; Rallabandi, B.; Hilgenfeldt, S. Fast inertial particle manipulation in oscillating flows. Phys. Rev. Fluids 2017, 2, 052001(R). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, M.; Green, R.; Ohlin, M. Acoustofluidics 14: Applications of acoustic streaming in microfluidic devices. Lab Chip 2012, 12, 2438–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutz, B.; Chen, J.; Schwartz, D.T. Hydrodynamic tweezers: 1. Noncontact trapping of single cells using steady streaming microeddies. Anal. Chem. 2006, 78, 5429–5435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleischmann, F.; Luzzatto-Fegiz, P.; Meiburg, E.; Vowinckel, B. Pairwise interaction of spherical particles aligned in high-frequency oscillatory flow. J. Fluid Mech. 2024, 984, A57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, H.; Giltinan, J.; Kozielski, K.; Sitti, M. Mobile microrobots for bioengineering applications. Lab Chip 2017, 17, 1705–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthasarathy, T.; Chan, F.K.; Gazzola, M. Streaming-enhanced flow-mediated transport. J. Fluid Mech. 2019, 878, 647–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinz, S. Direct and large-eddy simulations of wall-bounded magnetohydrodynamic flows in uniform and non-uniform magnetic fields. PhD thesis, Institut für Thermo- und Fluiddynamik, Technische Universität Ilmenau, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Prinz, S.; Thomann, J.; Eichfelder, G.; Boeck, T.; Schumacher, J. Expensive multi-objective optimization of electromagnetic mixing in a liquid metal. Optimization and Engineering 2021, 22, 1065–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, A.; Piedra, S.; Piñeirua, M.; Cuevas, S. Reverse streaming generated by a free-moving magnet. J. Fluid Mech. 2025, 1015, A28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.C.; Chen, C.L.; Chen, C. Electrokinetically-driven non-Newtonian fluid flow in rough microchannel with complex-wavy surface. J. Non-Newton. Fluid Mech. 2012, 173–174, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, L.; Bautista, O.; Escandón, J.; Méndez, F. Electroosmotic flow of a Phan-Thien–Tanner fluid in a wavy-wall microchannel. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochem. Eng. Aspects 2016, 498, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcos, J.; Bautista, O.; Méndez, F.; Peralta, M. Analysis of an electroosmotic flow in wavy wall microchannels using the lubrication approximation. Rev. Mex. Fís. 2020, 66, 761–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, S.; Sierra-Espinosa, F.Z.; Avramenko, A.A. Magnetic damping of steady streaming vortices in oscillatory viscous flow over a wavy wall. Magnetohydrodynamics 2002, 38, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, S.; Domínguez-Lozoya, J.C.; Córdova-Castillo, L. Oscillatory boundary layer flow of a Maxwell fluid over a wavy wall. J. Non-Newton. Fluid Mech. 2023, 321, 105125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, F.A. An introduction to fluid mechanics; Cambridge University Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Thielicke, W.; Stamhuis, E.J. PIVlab – Towards User-friendly, Affordable and Accurate Digital Particle Image Velocimetry in MATLAB. J. Open Res. Software 2014, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).