1. Introduction

Biodiesel fuel is the most widely used biofuel in road transport. Although biodiesel is a high-quality motor fuel, it can differ significantly from conventional diesel fuel in terms of its physico-chemical properties. Differences in these properties affect combustion process parameters, and consequently, the efficiency and environmental performance of the engine. Furthermore, the differences between the physico-chemical characteristics of biodiesel fuels produced by different methods or even by the same method but from different feedstocks should not be overlooked.

Several biodiesel production processes have found commercial application to date. The most common type of biodiesel on the market is produced by the transesterification process, using alcohol.

Biodiesel fuel obtained through the transesterification process belongs to traditional types of biofuel, that is, first or second generation biofuels. Chemically, it is a methyl ester of fatty acids and is known as FAME (Fatty Acid Methyl Ester) biodiesel, or less commonly as FAEE (Fatty Acid Ethyl Ester) biodiesel. Biodiesel fuel is usually produced from oils derived from purpose-grown crops, but the production of biodiesel from waste generated during food and beverage production processes is becoming increasingly relevant.

Given a wide range of feedstocks that can be used to obtain oil for biodiesel production, the combustion process characteristics can vary significantly, which in turn affects the engine’s energy and environmental performance indicators. Differences in combustion parameters, compared to those observed when using conventional diesel fuel, are especially pronounced when neat (unblended) biodiesel fuels are used [

1,

2].

Today, biodiesel fuels are typically used in blends with conventional diesel fuel. For many biodiesel–diesel blends, less favorable engine energy performance indicators are obtained compared to the use of neat diesel fuel. Increasing the proportion of biodiesel derived from flaxseed oil in a blend with conventional diesel fuel reduces the brake thermal efficiency (BTE) of the engine, and for all such blends BTE is lower than when burning neat diesel fuel [

3].

One way to influence the operating characteristics of an engine powered by neat biodiesel or a biodiesel–diesel blend is by adding a certain amount of water to the mixture. By adding 10% water to a blend of biodiesel produced from soybean oil and conventional diesel fuel, it is possible to reduce the brake-specific fuel consumption (BSFC) [

2].

Considering the physico-chemical properties of biodiesel fuel, it is interesting that under certain engine operating conditions, using an optimal proportion of biodiesel obtained from corn oil in a blend with conventional diesel fuel can yield more favorable engine performance, such as higher effective power output and lower BSFC, than in the case of using neat diesel fuel [

4].

Biodiesel fuel derived from cultivated microalgae is a newer generation biofuel, belonging to the third generation [

5]. Blends obtained by mixing biodiesel from cultivated microalgae and conventional diesel fuel burn at a higher rate in diesel engines than conventional diesel fuel [

6].

Plant-based waste generated during various stages of plant processing, waste cooking oil, as well as animal fats and oils, are increasingly being used as feedstocks for biodiesel production, mainly due to their low cost. Increasing the proportion of biodiesel derived from waste animal fats in blends with conventional diesel fuel results in lower peak cylinder pressures, while the combustion process begins earlier for these blends compared to neat diesel fuel [

7].

Using a blend of conventional diesel fuel and biodiesel produced from waste fish oil (FB25) has yielded better diesel engine performance compared to a blend of conventional diesel fuel and biodiesel from waste cooking oil (CB25) [

8]. However, when operating with both blends, the engine produced less power and had higher BSFC than with conventional diesel fuel, due to the lower heating value of the blends.

Coffee husks also represent a potential feedstock for obtaining oil used in biodiesel production. By adding small amounts, e.g., 10%, of biodiesel produced from coffee husk oil to conventional diesel fuel, blends can be obtained that can be used without major engine modifications. The engine performance with these blends is very similar to that achieved with neat diesel fuel, while the combustion process characteristics are even more favorable [

9].

One of the promising feedstocks for biodiesel production that arises as a byproduct of food and beverage manufacturing is waste grape seeds.

The five-year average wine production volume in the European Union (EU) for the period 2019–2023 was 156 million hectoliters (mhl), while in 2023 and 2024 it amounted to 144 mhl and 139 mhl, respectively [

10]. Global wine production in 2023 was around 236 mhl. According to literature data, one kilogram of grapes yields between 0.6 and 0.75 liters of wine. During wine production, a large quantity of waste is generated, posing an environmental burden. Grape seeds, skins, and stems represent solid waste in the wine industry. The mass fraction of grape seeds, skins, and stems in total grape mass is approximately 5%, 7%, and 5%, respectively [

11,

12]. Depending on the grape variety, the total mass of seeds, skins, and stems can reach as much as 20–30% of the processed grape mass [

13].

Given the enormous quantities of grapes processed annually into wine in the EU and worldwide, it is evident that millions of tons of waste are generated every year during wine production, posing both economic and environmental challenges. For this reason, in recent years, such waste has been recognized as a suitable feedstock for biofuel production, specifically biodiesel from grape seeds and ethanol from grape skins and stems.

Combustion of neat biodiesel fuel obtained from waste grape seeds in a single-cylinder, direct-injection diesel engine results in lower BTE compared to conventional diesel fuel. At full load and an engine speed of 1500 rpm, the maximum BTE is 32.34% for conventional diesel fuel and 30.28% for pure biodiesel produced from waste grape seeds [

14].

This difference in BTE can be considered negligible, given that the fuel used is neat biofuel derived from waste.

When using a blend of conventional diesel fuel and biodiesel from waste grape seeds (B5), favorable results are achieved in terms of combustion process parameters and energy efficiency, which differ only slightly from those obtained with conventional diesel fuel. When running on conventional diesel fuel, the engine achieves higher BTE than with the B5 blend, with the maximum difference being only 4.6% at full load [

15]. Due to the lower heating value of the blend, engine power is also slightly reduced when using the blend compared to conventional diesel fuel, with a maximum difference of 4.3% at full load.

2. Methodology

The combustion process of biodiesel–diesel fuel blends was investigated using an experimental single-cylinder, air-cooled, direct-injection diesel engine, model DMB 3DA450, the specifications of which are given in

Table 1. The engine was equipped with a mechanical fuel injection system and had a fixed injection timing. For the purpose of studying the combustion of biodiesel–diesel fuel blends, an injection timing of 21 deg before top dead center (BTDC) was selected.

The experimental engine was tested using blends of biodiesel produced from waste grape seed oil and conventional diesel fuel (B7 and B14), as well as with neat conventional diesel fuel (D100). The biodiesel fuel was obtained through the transesterification process of waste grape seed oil. Methanol was used as the alcohol in the transesterification process, while KOH served as the catalyst. The properties of the biodiesel fuel are presented in

Table 2. The conventional diesel fuel used for preparing the blends and for combustion as neat diesel complies with the SRPS EN 590:2022 standard.

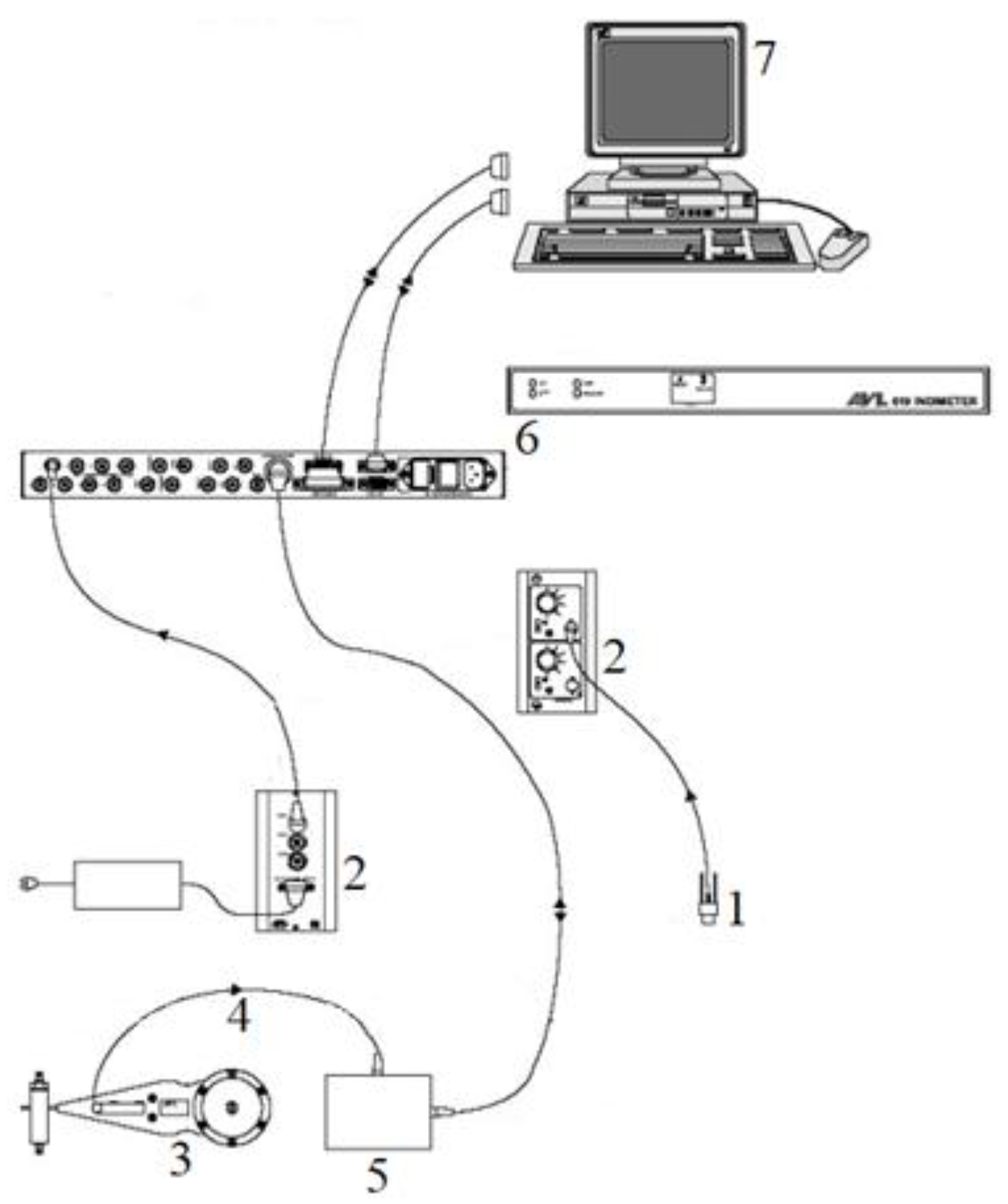

To determine the parameters of the combustion process, it is necessary to know variation of in-cylinder pressure throughout the engine cycle. The cylinder pressure is measured using a pressure indication measurement system, shown in

Figure 1. The measurement system consists of both analog and digital components. The analog part includes a piezoelectric pressure sensor and a signal-conditioning amplifier. The digital part consists of a crankshaft angle optical marker and TDC position sensor, an optical transmitter, and a signal multiplier.

In order to conduct experimental testing of the engine, the standard 13-step European Stationary Cycle (ESC) [

16] was applied as the test procedure. The European Stationary Cycle is used for measuring exhaust gas emissions during the certification of heavy-duty vehicles. Since the methodology for calculating exhaust emission parameters can also be applied to the indicator efficiency of the engine, the ESC test can be used to determine the engine’s energetic performance indicators.

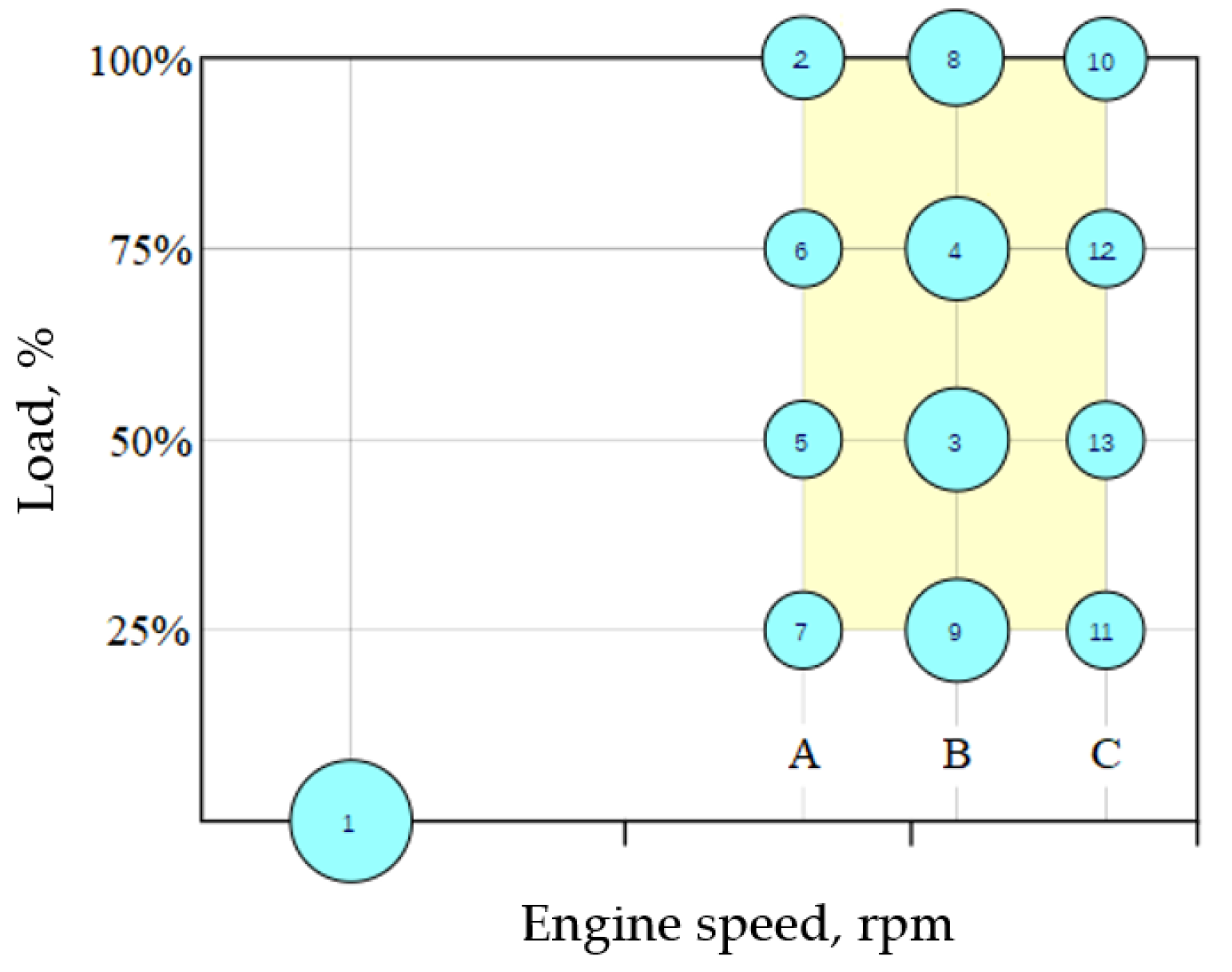

According to the test procedure, the engine is examined under 13 operating modes, arranged as shown in

Figure 2. The first mode corresponds to idle, while the remaining modes are organized to test the engine at three different speeds (A, B, C) and four different loads (25%, 50%, 75%, and 100%). The engine operates for 4 minutes in the first mode and 2 minutes in each of the remaining 12 modes.

The engine speeds A, B, and C are determined based on the external speed characteristic of the engine, with the following values:

A = 1635 rpm

B = 1937 rpm

C = 2239 rpm

The idle speed is n₁ = 1000 rpm.

3. Results and Discussion

The parameters of the combustion process, such as the combustion rates in individual phases of the combustion process and the amount of released heat, are most easily analyzed using diagrams of the heat release rate and cumulative heat release. The heat release rate is determined from Equation (1), [

17].

where:

, kJ·m-3·deg-1 heat release rate (HRR),

α - deg – crankshaft angle (CA),

К – coefficient with a value of 100 when the volume is expressed in dm³ and the pressure in bar units

n – polytropic expansion exponent

pi, bar – instantaneous value of pressure

Vi+1-Vi-1, dm3 – change in volume

Vi, dm3 – instantaneous value of volume

pi+1-pi-1, bar – change in pressure

The exponent of the polytropic expansion is determined from Equation (2):

Based on equation (2) and variation of in-cylinder pressure obtained from experimental research, the values of the polytropic expansion exponent were calculated for conventional diesel fuel and the blends:

Considering that the DMB 3DA450 engines are mostly used under real operating conditions to power small agricultural machines, the following will present the combustion process parameters for the most commonly encountered operating modes, namely medium-high load (75%) and high/maximum load (100%).

3.1. Results for Load of 75%

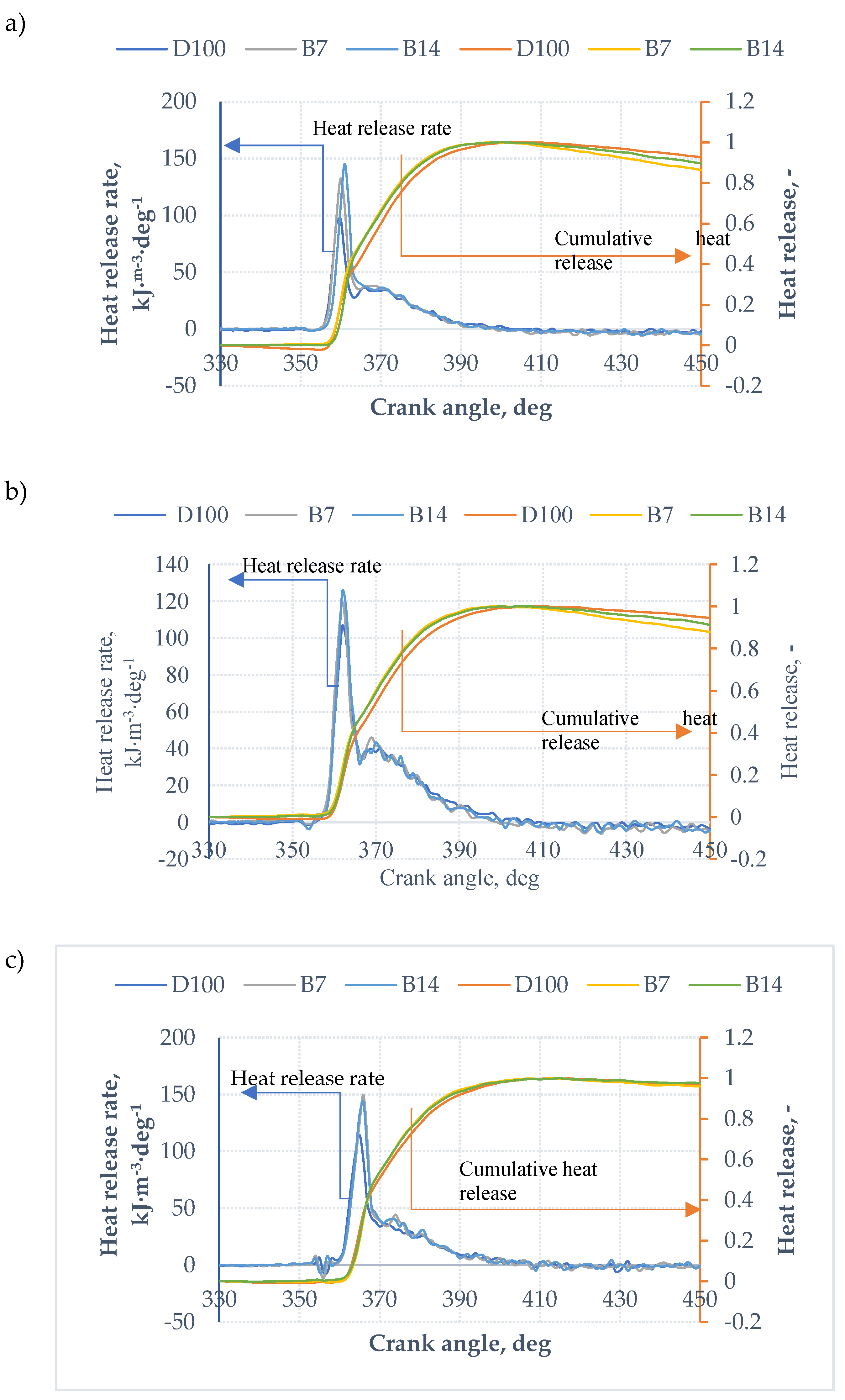

At 75% load, according to the ESC test, the corresponding operating modes are 6, 4, and 12.

Table 3 summarizes the parameters of the heat release rate and cumulative heat release, including: the maximum combustion rates for fuel mixtures and conventional diesel, the crank angle positions of the maximum combustion rates relative to TDC, and the combustion progress at 5%, 10%, 50%, and 90% of the total fuel injected per cycle. The heat release rate and cumulative heat release for these operating modes are graphically illustrated in

Figure 3.

The heat release characteristics during the combustion process influence not only the engine’s energy efficiency but also the mechanical loading of its components and the noise level. Rapid heat release and high peak heat release rates lead to steep pressure rises and elevated peak pressures within the engine cylinder, resulting in increased mechanical stresses on engine parts and a progressive increase in noise levels. The timing of the maximum heat release rate is also a critical parameter affecting both mechanical loading and engine noise.

Figure 3 shows that both biodiesel blends, despite slightly less favorable physicochemical properties, ignite earlier than conventional diesel. At modes 6 and 12, blend B7 ignites first, while at mode 4, blend B14 ignites earliest. This earlier ignition is partly due to the oxygen content in biodiesel, which enhances mixture formation, particularly immediately after injection, despite the fuel’s higher density and viscosity.

It can also be observed that the blends exhibit higher peak heat release rates compared to D100. At modes 6 and 4, blend B14 shows the highest peak heat release rate, while at mode 12, blend B7 reaches the maximum. The higher peak heat release rates of the blends compared to the conventional diesel are a consequence of the longer ignition delay period, caused by the higher density and viscosity of the blends, as well as their lower cetane numbers. The difference in peak heat release rates between the blends decreases with increasing engine speed, reaching only 4.2% at the maximum engine speed.

Taking into consideration the timing of peak heat release rate, it can be observed that the blends have generally reached their maximum heat release rates later than D100 (mode 6 for B14 and mode 12) or, in some cases, simultaneously (mode 6 for B7 and mode 4). For all tested fuels, the timing of the peak heat release rate has shifted further from TDC as engine speed increased, meaning that the maximum combustion rate has occurred later.

The cumulative heat release is a combustion process parameter used to assess the impact of combustion on engine cycle efficiency and exhaust emissions. From an efficiency perspective, the crank angle at which 50% of the cycle’s heat is released is considered particularly important.

At 75% load, the highest heat release rates during the combustion of the first 5% and 10% of the cycle fuel have occurred with blend B7 at modes 6 and 4, and with D100 at mode 12. For the first 50% of the cycle fuel, combustion has been slowest for D100 and fastest for B7 across all three modes. The same trend has been observed for the combustion of 90% of the cycle fuel. Thus, combustion lasted the longest for D100 and the shortest for B7.

3.2. Results for Load of 100%

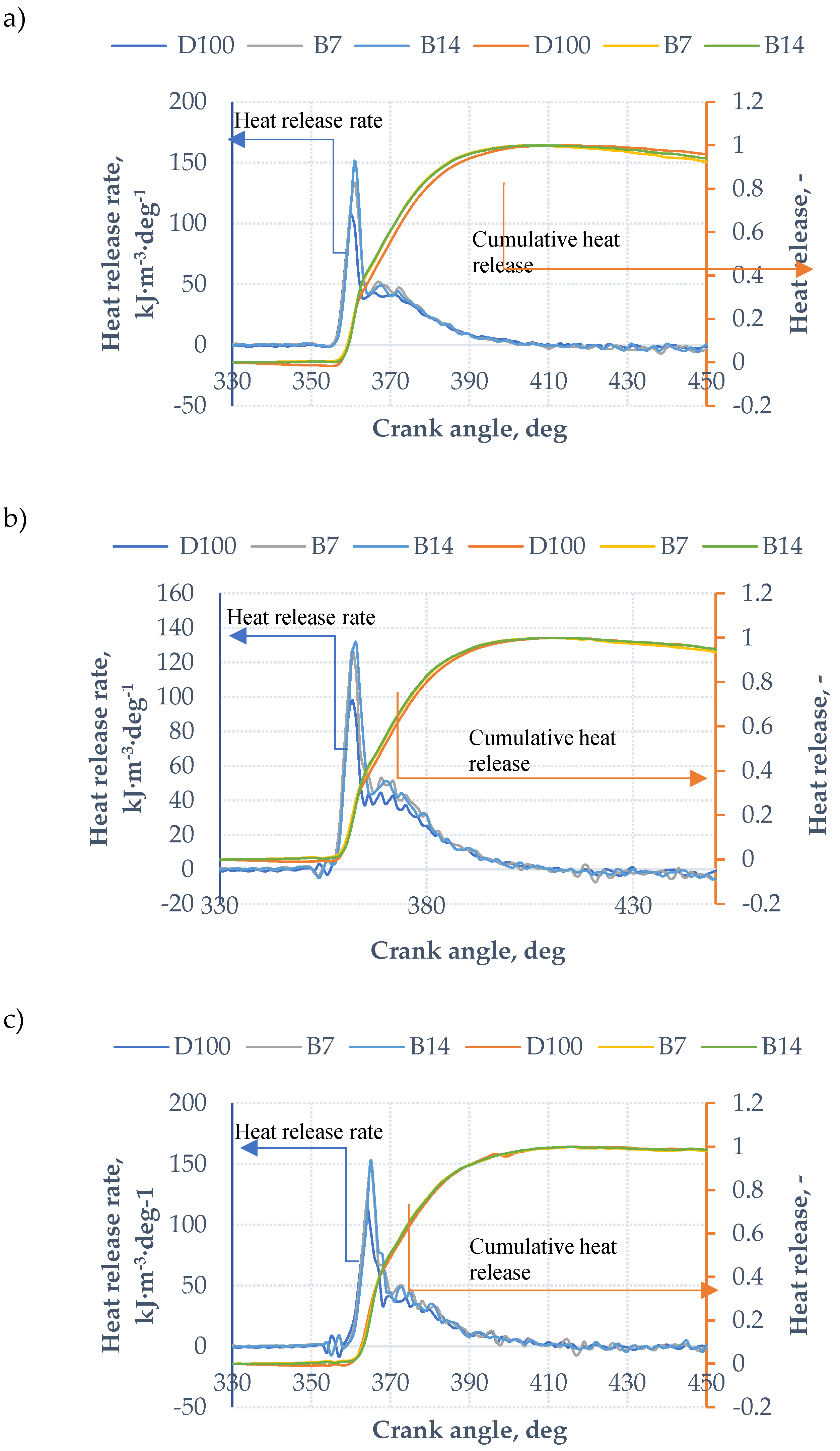

The combustion process parameters, i.e., the parameters obtained from heat release rate and cumulative heat release, for modes 2, 8, and 10, which have been implemented at 100% load, are given in

Table 4, while the graphical representation of the heat release rate and cumulative heat release are shown on

Figure 4.

Based on the heat release rate and cumulative heat release, it can be observed that in modes 2 and 8, the combustion of the B7 blend has started the earliest (

Figure 4), while in mode 10, the combustion of conventional diesel fuel has begun first.

For all three modes, in the case of using fuel blends, higher maximum heat release rates have been achieved compared to D100, which is logical. The highest maximum heat release rate has been obtained at the highest engine speed mode, for the blend with the higher biodiesel content (B14) and amounted to 152.99 kJ·m⁻³·deg⁻¹.

Furthermore, for each mode, the blends reached the maximum heat release rate later than D100, except for the B7 blend in mode 8, where B7 and D100 simultaneously reached their maximum value, at 2 deg.

When observing the cumulative heat release, i.e., combustion by phases, it is noticeable that the first 5% and 10% of the cycle fuel quantity have burned the fastest in the case of the B7 blend, except in mode 10, where D100 has burned the fastest. For all three modes, 50% of the cycle fuel quantity has burned faster when using the blends than when using D100. A higher biodiesel content in the blend corresponds to a faster combustion of 50% of the cycle fuel quantity, or in some cases, this combustion phase has lasted the same for both blends (mode 10).

The combustion of 90% of the cycle fuel quantity, for all three modes, has lasted the longest for D100. It can also be observed that the differences in the combustion duration of 90% of the cycle fuel quantity between B7 and B14 are small and depend on the engine speed mode.

4. Conclusions

Biodiesel fuel is a promising biofuel that is increasingly being considered for use in road transport. It is particularly interesting when produced from waste generated as a by-product in various stages of food and beverage production. Biodiesel fuel obtained from waste grape seed oil can be successfully combusted in a diesel engine, without any modifications, in the form of biodiesel and conventional diesel fuel blends B7 and B14. Both blends have proven to be high-quality motor fuels.

Based on the combustion of 50% of the cyclic fuel quantity, it can be concluded that in the case of using B7 and B14 blends, the engine’s working cycle is economical, and that these two blends are comparable to diesel fuel in terms of efficiency. Such energy performance can be attributed to the oxygen content present in biodiesel fuel and its blends. It should also be noted that before the experiment began, the injection timing was set to 21 deg, which also contributed to favorable combustion conditions.

At a load of 75%, the B7 blend has achieved the most favorable combustion of 50% of the cyclic fuel quantity, while at full load (100%), the B14 blend has performed best. From the standpoint of maximum heat release rates, the blends are somewhat less favorable fuels than D100, especially the B14 blend. However, in modern engines, this issue is overcome through multiple fuel injections, which optimize the combustion process.

Therefore, it can be concluded that both blends are acceptable as engine fuels, with B14 having an advantage since its use replaces a larger portion of conventional fuel with biofuel, without significantly affecting, or at least without substantially deteriorating, the engine performance.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, Z. Dj.; methodology, I.G.; writing—review and editing J. G. and N. S.; supervision, D. G. and A. M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FAME |

Fatty Acid Methyl Ester |

| FAEE |

Fatty Acid Ethyl Ester |

| BTE |

Brake thermal efficiency |

| BSFC |

Brake-specific fuel consumption |

| FB25 |

|

| CB25 |

|

| B5 |

|

| BTDC |

Before top dead center |

| B7 |

|

| B14 |

|

| D100 |

|

| TDC |

Top dead center |

| ESC |

European Stationary Cycle |

| HRR |

Heat release rate |

| CA |

Crankshaft angle |

References

- Bousbaa, H.; Kaid, N.; Alqahtani, S.; Maatki, C.; Naima, K.; Menni, Y.; Kolsi, L. Prediction and Simulation of Biodiesel Combustion in Diesel Engines: Evaluating Physicochemical Properties, Performance, and Emissions. Fire 2024, 7, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, V. Combustion, performance and emission evaluation of a diesel engine fueled with soybean biodiesel and its water blends. Energy 2020, 201, 117633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asokan, M.A.; Senthur Prabu, S.; Prathiba, S.; Sai Akhil, V.; Daniel Abishai, L.; Surejlal, M.E. Emission and performance behaviour of flax seed oil biodiesel/diesel blends in DI diesel engine. Mater Today: Proc 2021, 46, 8148–8152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayhana, V.; Çangalb, Ç.; Cesura, İ.; Çobana, A.; Ergena, G.; Çaya, Y.; Kolipa, A.; Özsert, İ. Optimization of the factors affecting performance and emissions in a diesel engine using biodiesel and EGR with Taguchi method. Fuel 2020, 261, 116371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, A.K.; Rasul, M.G.; Khan, M.M.K.; Sharma, S.C.; Hazart, M.A. Prospect of biofuels as an alternative transport fuel in Australia. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 2015, 43, 331–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, M.; Solomon, J.M.; Nadanakumar, V.; Anaimuthu, S.; Sathyamurthy, R. Experimental investigation on performance, combustion and emission characteristics of DI diesel engine using algae as a biodiesel. Energy Rep 2020, 6, 1382–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, R.; Kumar, S. Performance and combustion analysis of diesel and tallow biodiesel in CI engine. Energy Rep 2020, 6, 2785–2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behçet, R.; Yumrutas, R.; Oktay, H. Effects of fuels produced from fish and cooking oils on performance and emissions of a diesel engine. Energy 2014, 71, 645–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emma, A.F.; Alangar, S.; Yadav, A.K. Extraction and characterization of coffee husk biodiesel and investigation of its effect on performance, combustion, and emission characteristics in a diesel engine. Energy Convers Manag: X 2020, 14, 100214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organisation of Vine and Wine. Available online: https://www.oiv.int/sites/default/files/2024-11/OIV_2024_World_Wine_Production_Outlook.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Tița, O.; Lengyel, E.; Stegăruș, D.I.; Săvescu, P.; Ciubara, A.B.; Constantinescu, M.A.; Tița, M.A.; Rață, D.; Ciubara, A. Identification and Quantification of Valuable Compounds in Red Grape Seeds. Appl Sci 2021, 11, 5124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolonio, D.; García-Martínez, M.J.; Ortega, M.F.; Lapuerta, M.; Rodríguez-Fernández, J.; Canoira, L. Fatty acid ethyl esters (FAEEs) obtained from grapeseed oil: a fully renewable biofuel. Renew Energy 2019, 132, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaťák, J.; Velebil, J.; Malaťáková, J.; Passian, L.; Bradna, J.; Tamelová, B.; Gendek, A.; Aniszewska, M. Reducing Emissions from Combustion of Grape Residues in Mixtures with Herbaceous Biomass. Materials 2022, 15, 7288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chelladorai, P.; Varuvel, E.G.; Martin, L.J.; Bedhannan, N. Synergistic effect of hydrogen induction with biofuel obtained from winery waste (grapeseed oil) for CI engine application. Int J Hydrog Energy 2018, 43, 12473–12490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, A.K.; Rasul, M.G. Performance and combustion analysis of diesel engine fueled with grape seed and waste cooking biodiesel. Energy Procedia 2019, 160, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUR-Lex.europa.eu. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:31999L0096 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Operating instructions, AVL Indimеter 619, Hardware, No: AT1139E Rev. 01.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).