1. Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a serious public health problem that affects >10% of the general population worldwide, amounting to >800 million individuals [

1]. After cardiovascular complications, infections are considered the most common cause of hospitalization and mortality in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD), especially patients on hemodialysis (HD) [

2]. Mortality of patients with CKD from lung infections is 10 times higher than in the general population [

3]. Thus, such patients are at high risk of severe influenza infection and its complications [

4].

The increased sensitivity of patients with ESRD to infections could be caused by multiple factors: immune dysfunction, old age, concomitant diseases and conditions, such as diabetes, mineral and bone disorders, iron metabolism disorders and anemia, invasive dialysis procedures, violation of skin and mucous barriers, as well as constant exposure to nosocomial flora [

5].

Immune dysfunction in patients with ESRD is characterized by combined manifestations of immune response activation (systemic inflammation) and immunodeficiency [

6] Systemic inflammation is the main factor in the development of atherosclerosis, while immunodeficiency leads to a weakening of the immune response to infections and, as a result, determines a more severe complicated course and increased mortality in infectious diseases. Immunodeficiency is also the cause of a decrease in the post-vaccination immune response in patients with ESRD [

7]. The severity of immunodeficiency rises in parallel with the increase in uremia [

8,

9,

10], while innate and adaptive immune response are both affected.

The terminal stage of renal failure is accompanied by both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells populations aging. Lymphopenia observed in many studies is mainly associated with a decrease in the number of naive T-lymphocytes caused by inhibition of T-cell production in the thymus, and by increased apoptosis [

6,

9]. In the terminal stage of CKD, the depletion of the B-cell population also occurs, which leads to a decrease in the effectiveness of the humoral immune response [

11].

Uremia is not the only cause of immunodeficiency in patients with CKD. Hemodialysis is an independent factor that can negatively affect the number of dendritic cells, the number and phagocytic activity of granulocytes, as well as the number and suppressor activity of regulatory T cells [

12,

13]. In addition, an independent factor determining a weak immune response to infections is the age of patients with CKD: compared with the general population, the ESRD is much more common in people over 60 years of age [

14].

Despite the fact that data on the safety and protective effects of influenza vaccines in patients with CKD are limited and of relatively poor quality, annual influenza vaccination is mandatory for all patients with CKD [

15,

16]. Given the high danger represented by the influenza to the health of this category of patients, even a moderate level of preventive effectiveness can be considered sufficient [

15]. Thus, a number of studies have shown that vaccination against influenza in patients with CKD on hemodialysis can reduce the risk of developing pneumonia/influenza and other diseases, the risk and duration of hospitalization (including PIT), the risk of death, especially in the elderly [

17]. There is evidence that influenza vaccination in elderly patients with CKD reduces the risk of hospitalizations associated with heart failure [

18], the risk of acute coronary syndrome [

19] and peripheral arterial occlusive disease [

20], as well as the risk of dementia [

21].

According to international recommendations (KDIGO 2012), seasonal influenza prevention should be carried out annually with the use of IIV in all patients with CKD, regardless of the stage and whether these patients are being treated by dialysis or have undergone kidney transplantation. For patients over 65 years of age, the use of IIV at a higher dose (Fluzone High-Dose (Sanofi Pasteur), FluBlok (Sanofi Pasteur)) may be recommended [

22].

In the present study, we evaluated the post-vaccination humoral and cellular immune response to IIVs available in Russia during the 2019-2020 epidemic season in 22 HD patients. The observation was carried out within 6 months post vaccination. The results of immunological efficacy of IIVs were compared with the data for healthy volunteers without CKD of two age groups: 18-60 years old (n=34) and over 60 years old (n=42).

During the 2023-2024 season, the impact of prior vaccination was assessed by measuring antigen-specific antibody responses and induced IFNγ production in whole blood samples. The cohort of 71 hemodialysis patients was divided into groups based on their vaccination history: those who had not received the inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV) in the previous two epidemic seasons (n=28); those who had received IIV in the immediate prior season (2022-2023; n=34); and those who had been vaccinated in both of the last two seasons (2021-2022 and 2022-2023; n=9).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Populations.

From October 2019 to April 2020, 22 subjects who underwent hemodialysis at the St. Petersburg State Budgetary Healthcare Institution “City Hospital No. 15”, Russia, were included in the observational descriptive study in volunteers elder 18 years with known vaccination history conducted by Smorodintsev Research Institute of Influenza, Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. Inclusion criteria were (i) having not received influenza vaccine in the previous season, (ii) having received trivalent (TIV) or quadrivalent influenza vaccine (QIV) in 2019/2020 flu season (iii) willingness to provide blood samples to monitor the humoral and cellular immune response within the specified time pints during 6 months observation period. Blood samples for serum and PBMCs isolation were collected pre-vaccination (day 0), 7 and 21 days, 3 and 6 months after vaccination. Healthy volunteers of two age groups: 18-60 years old (n=34) and over 60 years old (n=42) were enrolled in the clinical department of the Smorodintsev Research Institute of Influenza, Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, with the same inclusion criteria, with that difference that only serum samples on days 0 and 21 were collected.

In 2023, we additionally recruited a new cohort of 71 hemodialysis volunteers who were followed at the “Kupchino outpatient dialysis center” LLC. The cohort was categorized as follows: 28 (39,44%) patients had not received inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV) in the previous two flu epidemic seasons, 34 (47,89%) patients had received IIV in the previous season (2022/2023), and 9 (12,67%) patients had been vaccinated in each of the last two seasons (2120/2022; 2022/2023). The latter were excluded from the comparative analysis because the sample size was insufficient.

2.2. Immunization.

In 2019/2020 flu season in Russian Federation for immunization were available two subunit adjuvanted TIVs - “Grippol plus”(GP, NPO Petrovax, Moscow, Russia) contains 5 μg of influenza viruses HA A/H1N1, A/H3N2 and B/Victoria and the adjuvant Polyoxidonium 500 μg per dose and “Sovigripp”(SG, NPO Microgen, Moscow, Russia) contains 5 μg of influenza viruses HA A/H1N1, A/H3N2 and 11 μg HA B/Victoria and the adjuvant Sovidon 500 μg per dose. Also, during this season “Ultrix Quadri” (UQ, FORT LLC, Moscow, Russia) – quadrivalent split not adjuvanted vaccine, containing 15 μg of influenza viruses HA A/H1N1, A/H3N2 and B/Victoria and B/Yamagata per dose, was used for immunization [

23,

24]. Strain composition of the vaccines corresponded to WHO recommendations and was the following: A/Brisbane/02/2018 (A(H1N1)pdm09), A/Kansas/14/2017 (A(H3N2)), B/Colorado/06/2017 (B/Victoria), B/Phuket/3073/13 (B/Yamagata – quadrivalent vaccine only).

In 2023 all 71 hemodialysis patients have got QIV Flu-M Tetra. Strain composition of the vaccines corresponded to WHO recommendations: A/Victoria/4879/2022 (A(H1N1)pdm09), A/Thailand/8/2022 (H3N2), B/Austria/1359417/2021 (B/Victoria), and B/Phuket/3073/13 (B/Yamagata) and differed from the 2022-2023 season vaccine composition in the influenza A virus components (A/Victoria/2570/2019 (A(H1N1)pdm09), A/Darvin/09/2021(A(H3N2)).

Vaccines were administered after signing of informed consent by trained medical personnel. Prior to vaccine administration, study participants underwent thermometry, blood pressure measurement, interview, and examination by the physician in charge of the vaccination. After immunization, the vaccinated subjects were monitored for 30 minutes by the physician, and for the next 5 days or more (depending on the timing of postvaccination reaction registration) by outpatient observation by medical personnel.

2.3. Antibody Response Assessment.

Systemic antibody response to vaccination was evaluated in blood sera by hemagglutination inhibition assay (HI) and microneutralization assay (MNA). The HI carried out as described in the Guidelines of MU 3.1.3490-17 [

25]. MNA was performed as described in the recommendations of the World Health Organization (WHO) [

26]. Diagnostic strains A/Brisbane/02/2018 (A(H1N1)pdm09), A/Kanzas/14/2017 (A(H3N2)), B/Colorado/06/2017 (B/Victoria), B/Phuket/3073/13 (B/Yamagata) were used as antigens in 2019/2020 and A/Victoria/4879/2022 (A(H1N1)pdm09), A/Thailand/8/2022 A(H3N2), B/Austria/1359417/2021 (B/Victoria), B/Phuket/3073/13 (B/Yamagata) in 2023/2024 season. The HI/MNA titer of antibodies was expressed as the reciprocal of the highest serum dilution, at which agglutination inhibition/CPE development was observed. If hemagglutination/CPE inhibition was not detected at the 1 : 10 dilution, the titer was taken equal to 5. The multiplicity of the antibody increase was calculated as the ratio of the antibody titer on Day X to the antibody titer on Day 1. Increasing of the antibody titer more than 4 times was considered seroconversion, and the corresponding volunteer was considered as the responder. When calculating the proportion of responders in each experimental group, the presence of seroconversion was taken into account on any of the days.

2.4. Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell (PBMCs) Isolation and Cryopreservation.

For PBMCs isolation venous blood samples were obtained using sodium heparin sulfate tubes. Within 4 hours of sampling PBMCs isolation was performed by sedimentation in a ficoll density gradient [

27]. After that, the cells were frozen and stored in liquid nitrogen until the use.

2.5. Intracellular Cytokine Staining (ICS).

To asses influenza-specific T-cell response restored PBMCs were stimulated with influenza split vaccine A/H1N1pdm09, A/H3N2, B/Victoria and B/Yamagata monocomponents (5 µg/well) kindly provided by SPBNIIVS. The relative number of antigen-specific cytokine-producing Tem lymphocytes was evaluated by ICS protocol using BD Fixation/Permeabilization kit (BD, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. We used the panels of fluorescently labeled antibodies to surface antigens CD3, CD4, CD8, CD45RA, CCR7 (Biolegend, USA) and intracellular cytokines IFN-γ/IL-2/TNF-α (Biolegend, USA). Gaiting strategy is shown in Supplementary (Figure S_). Data were collected using Cytoflex (BC, USA).The processing of flow cytometry data was carried out with software (H., Cytexpert, Beckman Coulter, Inc., USA) and Kaluza 2.0 (Beckman Coulter, Inc., USA).

2.6. T-follicular Helper Cells (Tfh) Evaluation.

Phenotyping of peripheral Tfh subpopulations was performed in cryopreserved PBMCs using the following markers: CD3, CD4, CXCR5, ICOS, CCR6, CXCR3, CD27, CD45RA, CCR7, CD62L, and PD1 (

Figure S1).

2.7. B-Cell Evaluation.

In the present study, the B-cell response was evaluated by flow cytometry in cryopreserved PBMCs using the following markers: CD3, CD20, CD27, CD38, IgD, and IgA, which revealed the following populations of B lymphocytes (CD3-CD19+): naive B cells (CD20+CD27-IgD+), non-switched memory B cells (CD20+CD27+IgD+), switched memory B cells (CD20+CD27+IgD-), effector memory B cells (CD20+CD27-IgD-), plasmablasts (CD20-CD38hiCD27hi). Activation of the B-cell immune response was assessed by measuring the relative content of CD38+ B cells belonging to populations of naive, effector B lymphocytes, switched, and non-switched memory B cells. (

Figure S2).

To evaluate the antigen-specific B-cell response, an ELISPOT assay was performed using commercial kits (Mabtech, Sweeden) according to a protocol adapted from Haralambieva et al. [

29]. Briefly, cryopreserved PBMCs were thawed and cultured for 72 hours in the presence of recombinant human IL-2 (10 ng/mL) and the TLR7/8 agonist R848 (1 µg/mL). Then cells were transferred to membrane plates (Millipore, USA) that had been pre-coated with either viral antigens or a capture antibody.

The coating antigens included monocomponents of the influenza split vaccine (A/H1N1pdm09, A/H3N2, B/Victoria, and B/Yamagata) at a concentration of 5 µg/well. An anti-human IgG capture antibody (clone MT91/45, 15 µg/mL) served as the positive control for total IgG-secreting cells, while wells with DPBS alone were used as a negative control. Cells were plated at densities of 2 × 10⁵ cells/well for the antigen-specific response and 1 × 10⁴ cells/well for the total IgG assessment. After a 20-hour incubation at 37 °C with 5% CO₂, the cells were removed, and the plates were processed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Antibody-secreting cells (ASCs) were visualized as spots, which were counted and analyzed using an ImmunoSpot S6 Ultimate UV Image Analyzer (CTL, USA). The results are expressed as the number of spot-forming units (SFU) per 2.0×10⁵ PBMCs.

2.8. Antigen-Specific IFNγ Release in Whole-Blood Cultures.

Heparinized blood was aliquoted 50 µL/well, into pre-prepared 96-well culture plates containing complete culture medium supplemented with antigens of influenza viruses A/H1N1pdm09, A/H3N2, B/Victoria and B/Yamagata (5 µg/well) 150 µL/well. For each sample, wells corresponding to positive (non-specific stimulation with PMA + Ionomycin) and negative (unstimulated - complete culture medium) controls were also included. The samples were stimulated at 37 °C, 5% CO2 for 24 hours. After incubation the supernatants were collected and frozen and at -70 °C. The level of IFN-γ induction in the stimulated samples was determined using a commercial ELISA kit “Gamma-Interferon-ELISA-BEST” (Vector-BEST, Russia) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The Optical Density (OD) was measured using a Multiscan Sky High spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA) at a primary wavelength of 450 nm and a reference wavelength of 650 nm.

2.9. Statistics Analysis

For data visualization and statistical analysis GraphPad Prism 10.1.0, and RStudio Desktop 3.3.0 were used. Continuous data are presented as the arithmetic mean ± standard deviation (SD), standard error of the mean (SEM), or geometric mean (GM). For linked samples, we used the paired Wilcoxon test. Correlations were assessed using Pearson’s test, and compared multiple groups with the Kruskal-Wallis test, one-way ANOVA or two-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

A total of 22 hemodialysis patients were included in the study.

Table 1 shows detailed characteristics of the group. The average age of hemodialysis patients was 64 years, with 73% of the included patients being over 60 years old. All patients received dialysis therapy 3 times a week for 4 – 4.5 hours. The hemodialysis efficiency is calculated by the formula for the spKt/V single-pulse urea distribution model, used to evaluate the effective urea clearance per dialysis session, expressed as a fraction of the volume of urea distribution in each patient [

28], was satisfactory in all patients (>1.4).

3.2. Immunological Efficacy of the IIVs in Hemodialysis Patients

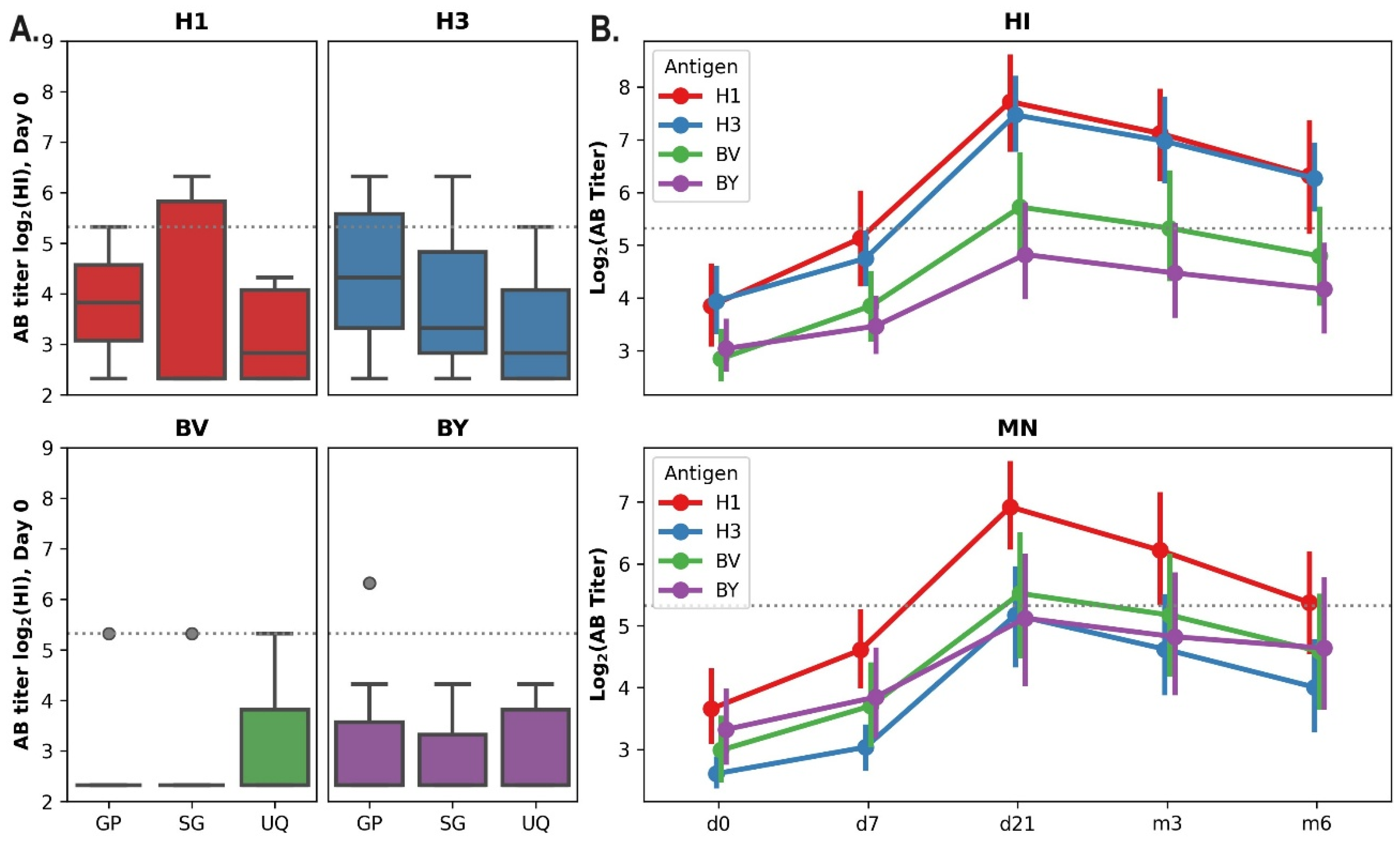

Due to the previous influenza illness or vaccination history, the preexisting levels of antibodies (Abs) to various strains and subtypes of the influenza virus can markedly vary between individuals. Among the vaccinated hemodialysis patients, both seronegative (antibody titer ≤1:20) and seropositive individuals (who initially had a protective titer ≥ 1:40 (HI)) were identified. Before the start of vaccination in autumn 2019, the percentage of seronegative individuals among this study group to influenza A/H1N1pdm09 virus was 77%, to influenza A/H3N2 virus - 68%, to the B/Victoria virus - 86.4% and to the B/Yamagata virus -95.5%. There were no statistically significant differences in the distribution of volunteers immunized with different vaccines in the initial titers of ABs for all vaccines’ components (A/H1N1pdm09, A/H3N2, B/Victoria, B/Yamagata) (p<0.05, Kruskal-Wallis test,

Figure 1).

The immunological efficacy of all applied vaccines in hemodialysis patients completely met all criteria formulated by the European Committee on Patented Medicines (CPMP/BWP/214/1996) for IIVs (criteria for persons over 60 years of age were used). However, it should be noted that the increase in the AB response following “Sovigripp” vaccination was lower than after “Ultrix Quadri” and “Grippol plus”, especially A/H1N1pdm09 and A/H3N2 for components (

Table 2).

Table 3 shows the data reflecting the level of neutralizing AB in response to vaccination with the studied IIVs. It is noteworthy that the titers of neutralizing ABs correspond to the titers of HA-binding AB only for the A/H1N1pdm09 component, while the titers of neutralizing ABs to A/H3N2 and both influenza B virus components are significantly lower than the titers of HA-binding Abs (

Table 3). However, this pattern is typical not only for the group of hemodialysis patients, but also for other groups of volunteers (cross-sectional study) vaccinated in the epidemic season 2019-2020 [

29].

When comparing the parameters of immunological efficacy in hemodialysis patients with those in healthy volunteers without CKD of two age groups, it was revealed that hemodialysis patients responded better to component B/Victoria (

Table 4).

3.3. Post-Vaccination Immune Response Dynamics in Hemodialysis Patients

The dynamics of the antibody response in the hemodialysis cohort was evaluated during a 6-month period following vaccination (

Figure 1B). Maximum titers of hemagglutination-inhibiting (HI) and neutralizing antibodies (NAbs) were observed at 21 days post-vaccination, followed by a subsequent decline. However, for H1N1pdm09 and H3N2 viruses, the hemagglutination-inhibiting (HI) antibody titers remained above 40 (the minimum protective antibody level) six months after vaccination.

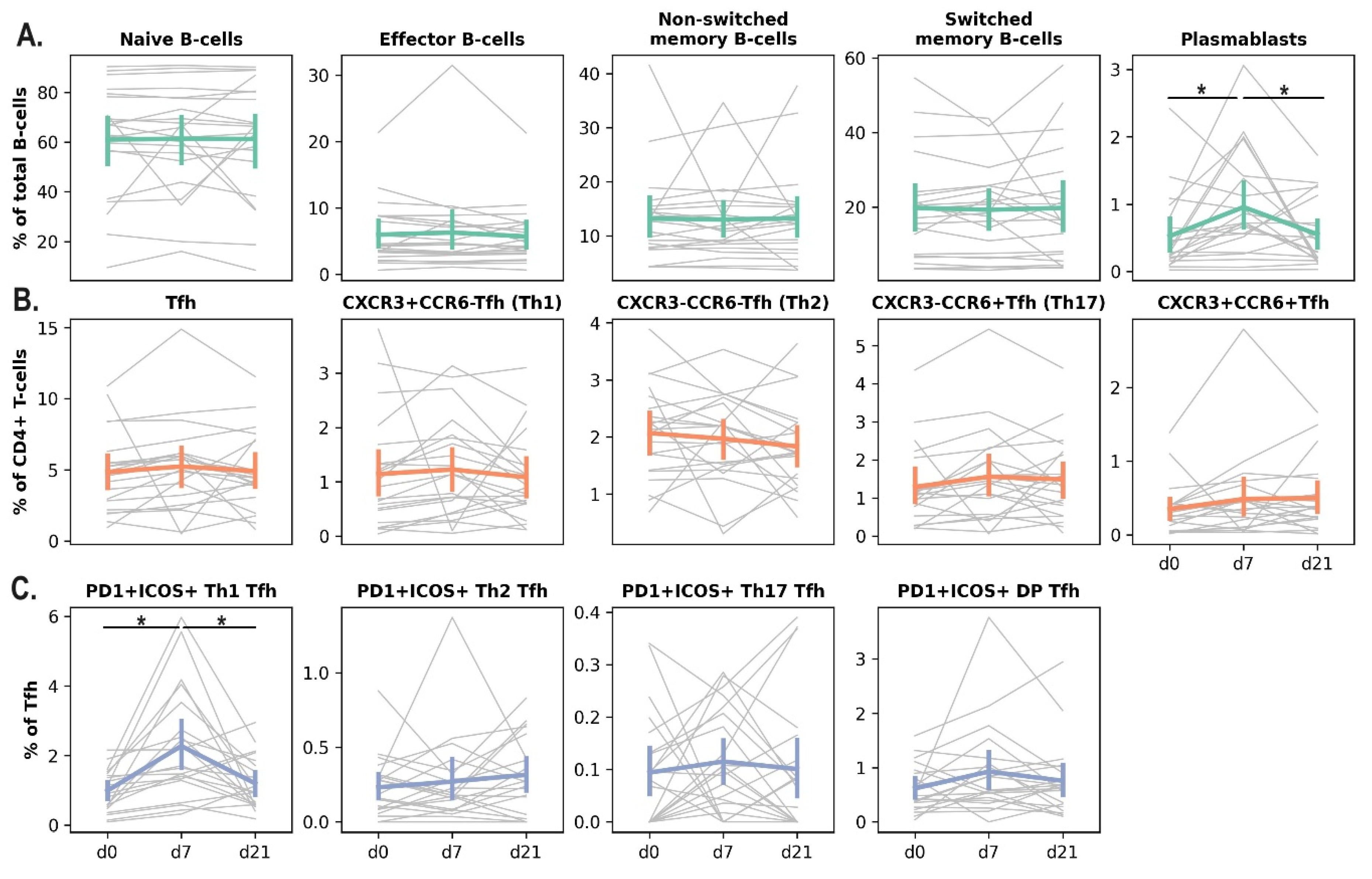

In addition to assessing the humoral response to IIV in the HD cohort, we performed a comprehensive analysis of the cellular immune response. We evaluated the frequencies of plasmablasts (PB), T-follicular helper cells (Tfh), antigen-specific memory B cells, and effector memory CD4⁺ and CD8⁺ T cells (Tem).

Vaccination led to a significant increase in the percentage of activated (PD1+ICOS+) Tfh1 cells and plasmablasts in the blood of dialysis patients on day 7 after the vaccine administration. On day 21, the percentage of these populations returned to the baseline level (

Figure 2).

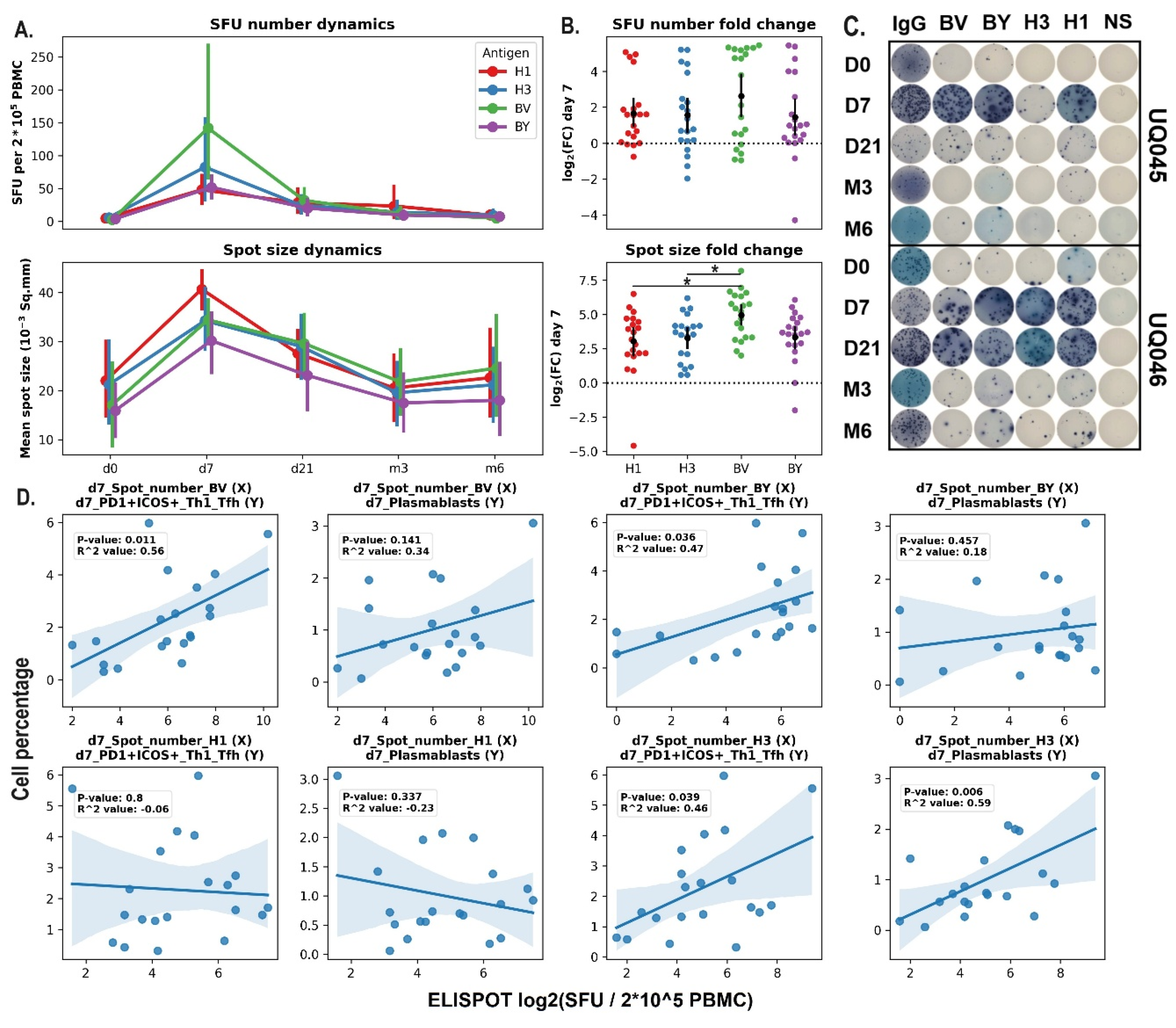

The dynamics of antigen-specific B-cells in the blood of hemodialysis patients after vaccination was measured using the ELISPOT assay. Both the number of spots and the average spot size increased significantly on day 7 after the vaccine administration and returned to the baseline levels afterwards (d21 – m6). The most prominent increase in terms of total SFU number compared to the corresponding values on day 0 was induced by B/Victoria vaccine component compared to the H1 and H3 components (

Figure 3 A,B).

Pearson’s correlation analysis was performed to assess the relationships between the cell population dynamics in the blood and the antigen-specific immune response analyzed with the ELISPOT (

Figure 3E). The statistically-significant correlation was shown for the variables that demonstrated the increase on day 7 after the vaccine administration. The percentages of activated (PD1+ICOS+) Tfh1 and plasmablasts were positively associated with the average numbers of SFU for H3 and B/Victoria vaccine components. However, no correlation was shown for H1 and B/Yamagata antigens.

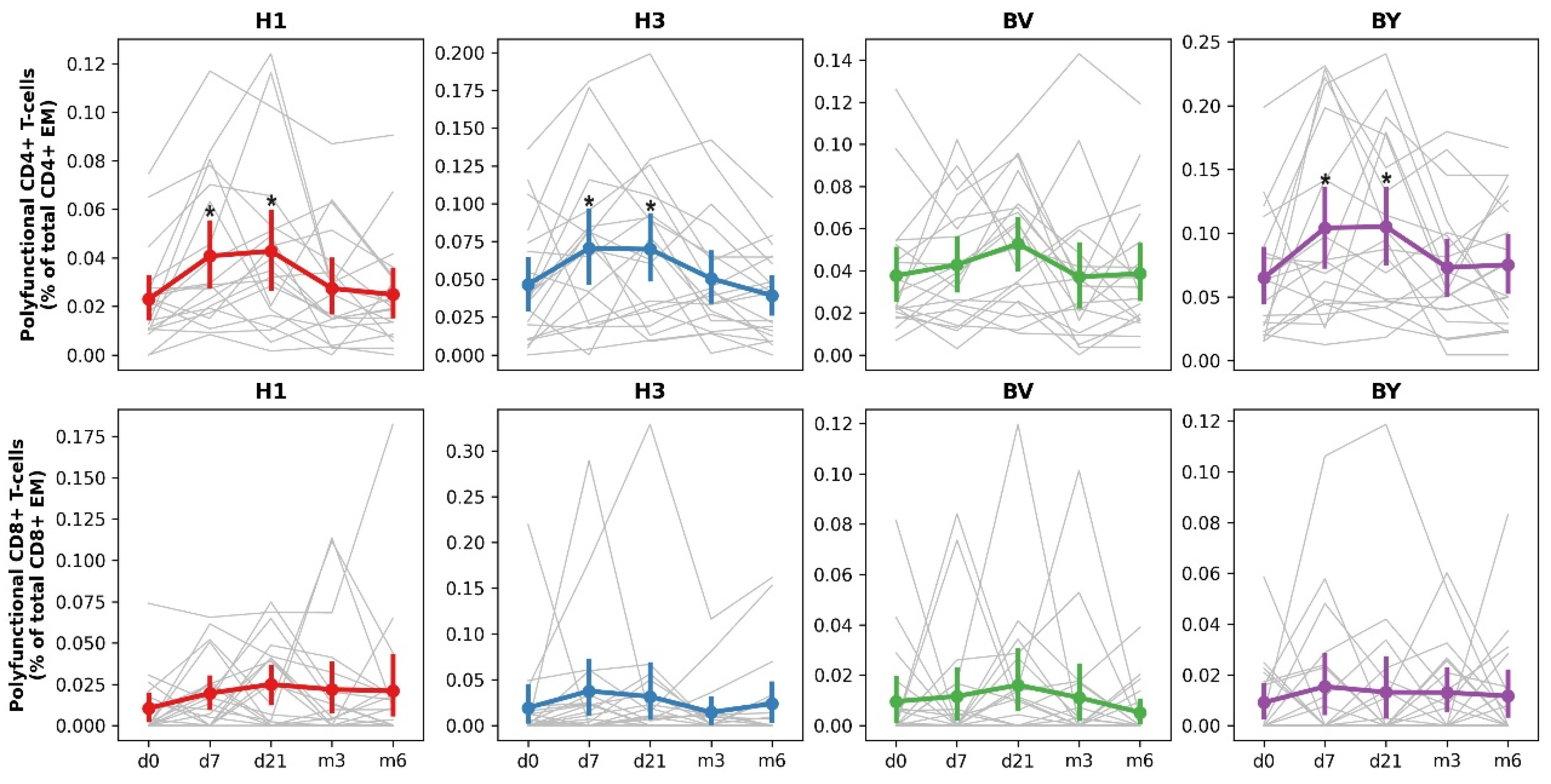

Analysis of the level, functional characteristics and duration of post-vaccination antigen-specific (A/H1N1pdm09, A/H3N2, B/Victoria and B/Yamagata) T-cell response to the IIVs “Grippol plus”, “Sovigripp” and “Ultrix Quadri” in hemodialysis patients was performed by flow cytometry in samples of cryopreserved peripheral blood mononuclear cells received before (Day 0), 7, 21 days and 6 months after vaccination, regardless of the type of vaccine used (in total).

According to the data obtained, vaccination induced an increase in the total number of antigen-specific polyfunctional CD4+ Tem cells 7 and 21 days after vaccine administration (

Figure 4). The most pronounced immune response was observed when cells were stimulated by influenza A/H1N1pdm09, A/H3N2 and B/Yamagata antigens. The CD8 Tem response was more modest.

Thus, vaccination of hemodialysis patients led to the formation of a T-cell immune response in vaccinated individuals, predominantly accompanied by the formation of multifunctional CD4+ effector T-lymphocytes.

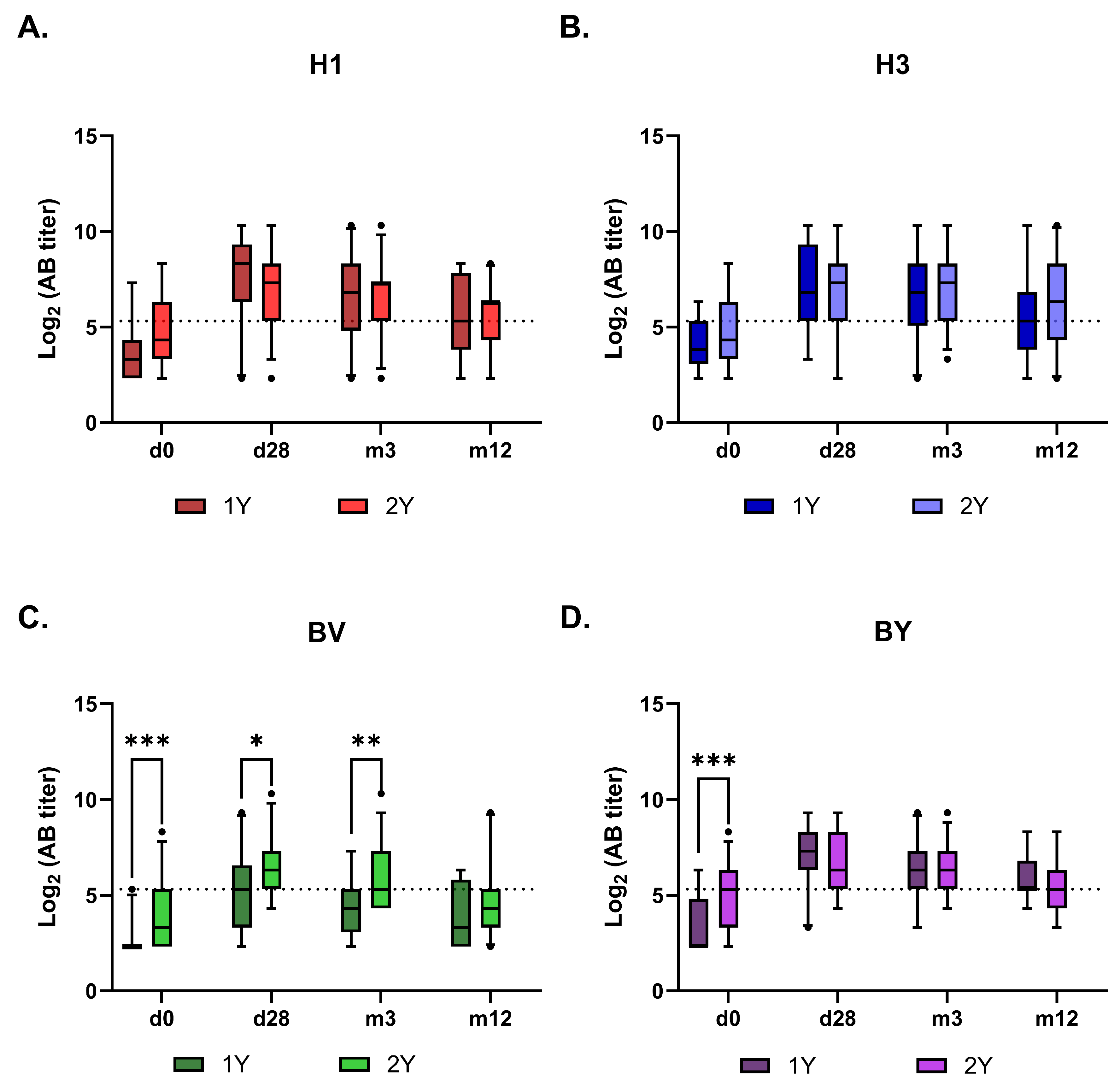

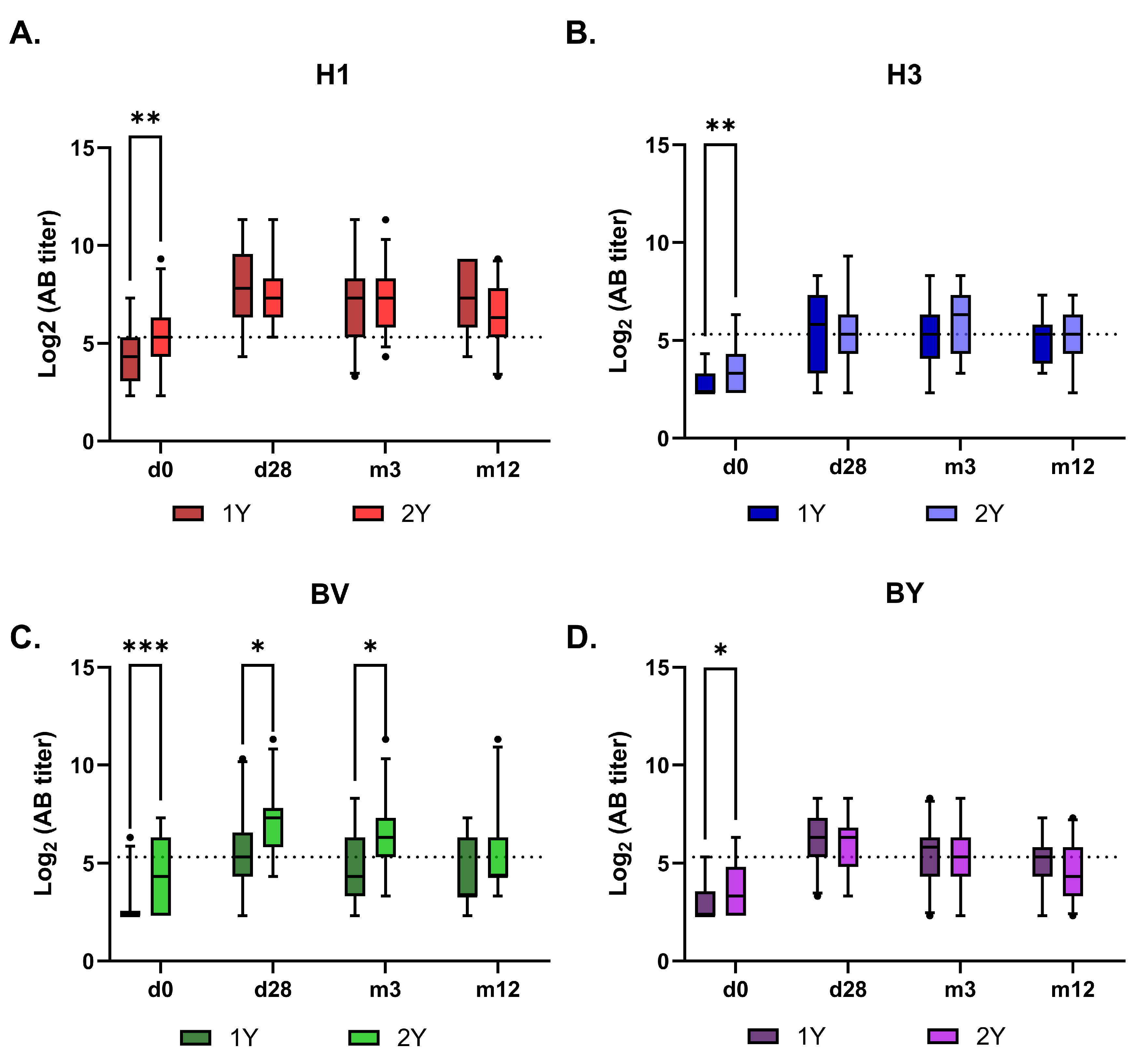

3.4. Effect of Repeated IIV on the Post-Vaccination Immune Response

Originally, it was planned to follow the cohort of hemodialysis patients through several consecutive influenza epidemic seasons. However, the study was interrupted during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, when the dialysis center involved in the study was converted into an infectious disease hospital, resulting in the distribution of the patient cohort to other centers. In 2023, we recruited a new cohort of 71 hemodialysis volunteers, categorized as follows: 1Y - 28 (39,44%) patients had not received inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV) in the previous two flu epidemic seasons, 2Y - 34 (47,89%) patients had received IIV in the previous season (2022/2023), and 3Y - 9 (12,67%) patients had been vaccinated in each of the last two seasons (2120/2022; 2022/2023). The latter were excluded from the comparative analysis because the sample size was insufficient. Strain composition of the vaccines corresponded to WHO recommendations in 2022 was the following: A/Victoria/2570/2019 (A(H1N1)pdm09), A/Darvin/09/2021(A(H3N2)), B/Austria/1359417/2021 (B/Victoria), B/Phuket/3073/13 (B/Yamagata). In 2023 A(H1N1)pdm09 component was replaced by A/Victoria/4879/2022, and H3N2 component – by A/Thailand/8/2022 both B virus strains remained the same. All 71 hemodialysis patients have got tetravalent IIV Flu-M Tetra. The detailed characteristics of the group are shown in

Table 5.

The immunogenic effectiveness of vaccination, as assessed by HAI and MN assays, met the CPMP criteria for all vaccine components, irrespective of prior-season vaccination status (

Table 6 and

Table 7). According to the HAI assay using 2023 antigens, the baseline seroprotection rate was significantly higher in the repeat-vaccinee group (2Y) than in the 1Y group for only the B/Victoria component. In contrast, the microneutralization (MN) assay showed higher baseline neutralizing antibody titers against all vaccine components in the repeat-vaccinee group.

The subsequent antibody kinetics were similar between the 1Y and 2Y groups for all vaccine antigens, except for the B/Victoria component (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). The response to this component was higher in the 2Y group for at least three months post-vaccination, only converging with the 1Y group’s level after one year. Interestingly, no such booster effect of repeated vaccination was observed for the B/Yamagata component.

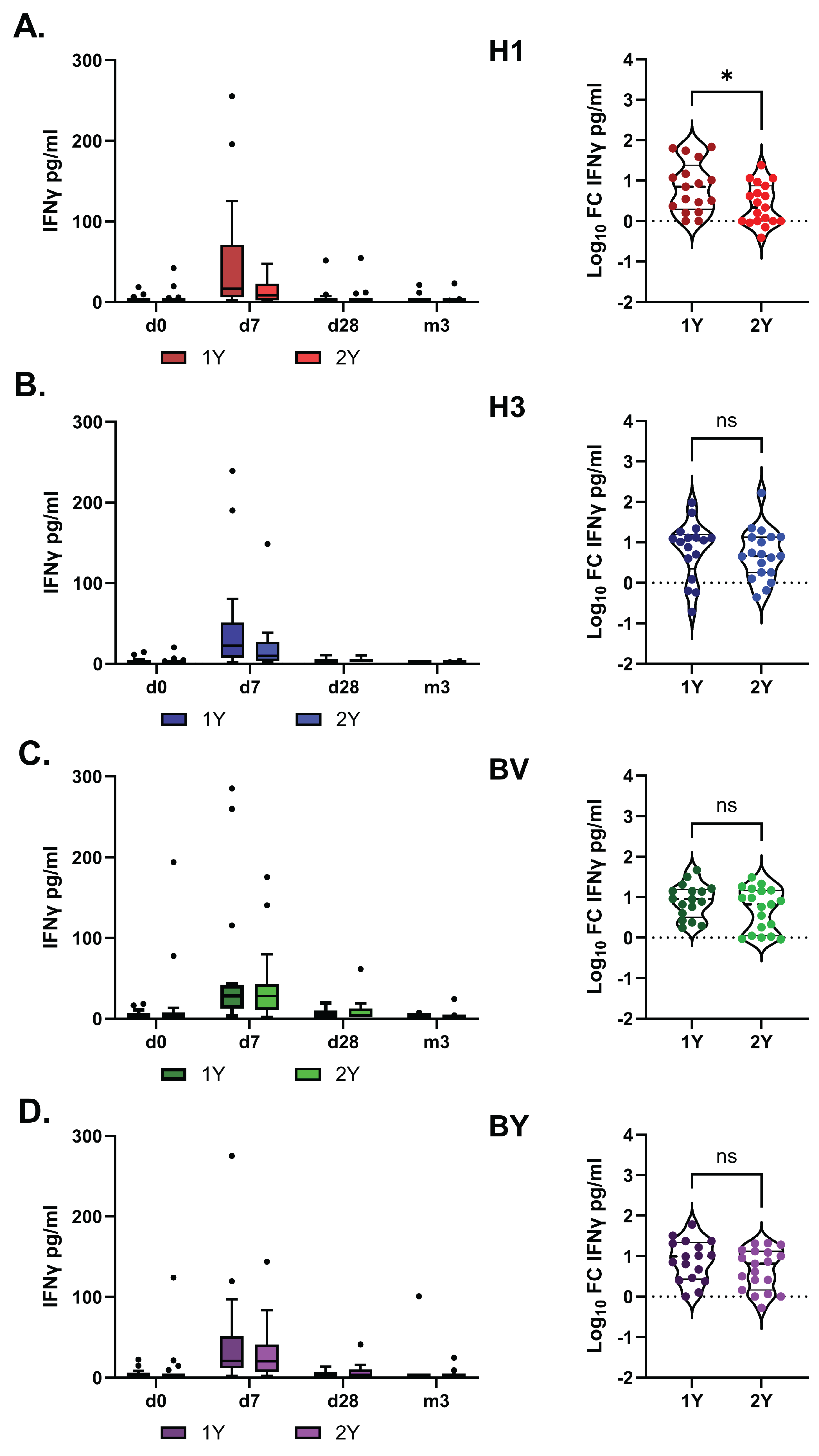

The impact of vaccination on the T-cell immune response was assessed by measuring IFN-γ in antigen-stimulated whole blood samples. This method has previously been described as a simple and informative approach for evaluating the T-cell response to influenza vaccination [

30].

IFN-γ production peaked on day 7 after vaccination and did not differ significantly between the study groups overall. However, in the 1Y group, the fold increase in IFN-γ levels following stimulation with the H1 antigen was higher than in the 2Y group (

Figure 7).

4. Discussion

Seasonal influenza contributes significantly to morbidity and mortality among immunocompromised individuals, including patients with CKD [

4].

Despite conflicting data on the effectiveness of influenza vaccination in patients with CKD, and particularly in hemodialysis patients, its necessity appears unequivocal [

15,

31]. In patients with eGFR ≥ 30 mL/min/1.73 m2, influenza vaccination is associated with a reduction in hospitalization rates and the risk of developing pneumonia [

32]. Furthermore, several small cohort studies have indicated that annual influenza vaccination is associated with reduced risks of heart failure-related hospitalizations [

18], acute coronary syndrome [

19], and dementia [

21] in elderly CKD patients.

Practical Guide to vaccination in all stages of CKD, including patients treated by dialysis or kidney transplantation state: seasonal influenza vaccination with IIV should be administered annually to all adult patients with CKD, regardless of whether these patients are undergoing dialysis or have received a kidney transplant [

22].

Several strategies have been proposed to improve IIV effectiveness in hemodialysis patients including the use of high-dose vaccines, booster doses, or adjuvanted IIVs. High dose IIV improved immunogenicity without increasing serious adverse events [

33] and according to McGrath et. all was associated with a reduction in hospitalization rates compared to standard-dose vaccination, in hemodialysis patients especially in individuals over 65 years old [

34]. However, in the later study the high-dose influenza vaccine has not demonstrated significant advantages over the standard-dose vaccine in preventing mortality or hospitalizations in HD patients, raising questions about its cost-effectiveness due to higher cost and potential side effects [

35].

Booster IIV vaccination has long been recommended to improve the level of protection of patients with chronic renal disease; however, the efficacy of this approach remained controversial, and was not proved based on the results of a subsequent meta-analysis [

36].

A large body of knowledge on the effectiveness of vaccination in hemodialysis patients has been accumulated in recent years during the COVID-19 pandemic. Similar to influenza, hemodialysis patients who contract COVID-19 are at an increased risk of severe disease and mortality, as they are often immunocompromised [

37]. Data on vaccine effectiveness are conflicting and suggest possibly lower effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in HD patients compared to the general population [

38,

39,

40,

41]. Factors associated with the weak response to the COVID-19 vaccine in hemodialysis patients include older age, low serum albumin, low lymphocyte counts, high intravenous iron dosage, and high body mass index (BMI) [

42]. This rather suggests that the effectiveness of vaccination in hemodialysis patients could be influenced by a combination of various factors, including the technical characteristics of the dialysis therapy itself. For instance, a study by Tadashi Tomo et al.l [

43] showed that the response to influenza virus vaccination was lower in hemodialysis patients compared to healthy volunteers. Changing the dialysis membrane from polysulfone (PS) to polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) affected the vaccination response in hemodialysis patients.

In our study, we showed that when using standard doses of IIV, hemodialysis patients’ level of immune response to all studied vaccines, containing a standard dose of antigens, met the criteria of the European Committee for Proprietary Medicinal Products (CPMP/BWP/214/1996) for the appropriate age category. Along with the humoral immune response, vaccination successfully triggered a coordinated cellular immune response characterized by a pronounced increase in activated Tfh1 cells, a corresponding surge in plasmablasts, and a rise in antigen-specific B-cells at day 7 post-vaccination. A T-cell response followed, predominantly mediated by CD4+ effector memory T cells.

At the same time, the parameters of immunological efficacy and duration of the humoral immune response in the hemodialysis patients were not inferior to those in the general population of volunteers initially vaccinated in the 2019-2020 epidemic season [

29].

Our data are consistent with the results published by Johan Scharpé et al. [

44] and later by Christos Pleros et. al. [

45]. Both studies reported that influenza vaccination is as effective in HD patients as in healthy volunteers. Except for serum ferritin level, none of the investigated parameters of nutrition, inflammation, and dialysis adequacy or modality had a significant impact on the immune response [

44]. This may probably reflect the fact that modern effective dialysis therapy contributes to the compensation not only of renal insufficiency as such but also of concomitant CKD-related immunodeficiency.

Jaromír Eiselt and coauthors reported that the influenza vaccine-induced antibody production was lower in HD group than in controls, indicating that previous vaccination and age are more important predictors of immune response to influenza vaccine than inflammation and iron status in dialysis patients [

46].

The influence of pre-existing antiviral immunity on the post-vaccination response, along with the related challenge of multiple vaccinations, has been actively debated in recent years. Numerous studies indicate that the effectiveness of influenza vaccines can be reduced by repeated immunization over consecutive years [

47,

48]. One possible explanation for this phenomenon was proposed in the 1990s by the creators of the “antigenic distance” hypothesis [

49]. They demonstrated that when the viral components used in sequential vaccinations are antigenically similar, the re-administration primarily activates the memory B-cells generated from the primary exposure. This comes at the expense of mounting a de novo B-cell response specific to the newly introduced antigen (Ag), a phenomenon termed “negative interference.” Consequently, while the efficacy of repeated vaccinations is diminished, protection against disease caused by a virus antigenically similar to the vaccine strain is still conferred by the memory antibodies (Abs) produced during the initial immunization. Conversely, if the antigenic distance between strains in sequentially administered vaccines is sufficiently large, the immune system effectively recognizes the new Ag upon re-administration. This leads to a robust induction of specific protective Abs and memory B-cells targeted against it. To date, the number of studies validating this concept of reduced efficacy in repeated vaccinations remains limited [

50,

51].

In our study, we did not observe any negative impact of repeated immunization on the dynamics of the antibody response, rather than to antigen-specific IFNγ production, in hemodialysis patients. The neutralizing antibody activity against all vaccine antigens was significantly higher in the re-vaccinated group. This discrepancy likely reflects the minimal antigenic distance between the vaccine strains of the 2022/2023 and 2023/2024 seasons. The magnitude and dynamics of the antibody response to influenza A viruses and influenza B/Yamagata were comparable between individuals who had and had not been vaccinated in the previous season. The antibody response to the B/Victoria virus was significantly higher in the group vaccinated for two consecutive seasons, for at least three months post-vaccination. The T-cell response (IFN-γ production) was robust in both groups, with only a slightly higher fold-increase for H1 in the first-time vaccinees.

In summary, while immunocompromised individuals like hemodialysis patients face a significant burden from influenza, the body of evidence affirms that annual influenza vaccination remains a crucial and effective protective strategy. Our study, consistent with other recent research, demonstrates that hemodialysis patients can mount a robust and compliant humoral and T-cell immune response to standard-dose inactivated influenza vaccines (IIV) that is not inferior to the general population. This suggests that modern dialysis therapy may effectively mitigate the immunodeficiency associated with chronic kidney disease.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Figure S1: Tfh gating strategy.; Figure S2: B-cells gaiting strategy; Figure S3: Polyfunctional memory T- cells gaiting strategy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, APS and MSt; methodology APS, KVa, ERR, VK, MSh, software, KVa, MSh.; validation, ERR, VK, MSh; formal analysis, APS, MSe, KVa.; investigation, KVi, DS, AT.; DL, resources, JB.; data curation, APS, MSt, JB; writing—original draft preparation, APS; writing—review and editing APS, MSt; visualization, APS, KVa; supervision, DL.; project administration, MSt.; funding acquisition, MSt, DL. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research was carried out under protocols “PEV-2019/2020”, version 01 (26 Sep 2019), which was approved by the Local Ethics Committee of the Smorodintsev Research Institute of Influenza (Approval #145, 04 Oct 2019) and “PEV-2023/2024”, version 01 (14 Sep 2023), which was approved by the Local Ethics Committee of the Smorodintsev Research Institute of Influenza (Approval #190, 05 Oct 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting reported results are available under request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kovesdy, C.P. Epidemiology of Chronic Kidney Disease: An Update 2022. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2022, 12, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, S.; Chitturi, C.; Yee, J. Vaccination in Chronic Kidney Disease. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2019, 26, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarnak, M.J.; Jaber, B.L. Pulmonary Infectious Mortality among Patients with End-Stage Renal Disease. Chest 2001, 120, 1883–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, B.T.; Rosner, M.H. Influenza and the Patient with End-Stage Renal Disease. J. Nephrol. 2018, 31, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naqvi, S.B.; Collins, A.J. Infectious Complications in Chronic Kidney Disease. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2006, 13, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaziri, N.D.; Pahl, M. V; Crum, A.; Norris, K. Effect of Uremia on Structure and Function of Immune System. J. Ren. Nutr. Off. J. Counc. Ren. Nutr. Natl. Kidney Found. 2012, 22, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastalerz-Migas, A.; Gwiazda, E.; Brydak, L.B. Effectiveness of Influenza Vaccine in Patients on Hemodialysis--a Review. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2013, 19, 1013–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girndt, M.; Sester, M.; Sester, U.; Kaul, H.; Köhler, H. Molecular Aspects of T- and B-Cell Function in Uremia. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2001, 78, S206–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, G. Immune Dysfunction in Uremia 2020. Toxins (Basel). 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losappio, V.; Franzin, R.; Infante, B.; Godeas, G.; Gesualdo, L.; Fersini, A.; Castellano, G.; Stallone, G. Molecular Mechanisms of Premature Aging in Hemodialysis: The Complex Interplay Between Innate and Adaptive Immune Dysfunction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.W.; Chung, B.H.; Jeon, E.J.; Kim, B.-M.; Choi, B.S.; Park, C.W.; Kim, Y.-S.; Cho, S.-G.; Cho, M.-L.; Yang, C.W. B Cell-Associated Immune Profiles in Patients with End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD). Exp. Mol. Med. 2012, 44, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.U.; Kim, M.; Kim, S.; Nguyen, T.T.; Kim, E.; Lee, S.; Kim, S.; Kim, H. Dendritic Cell Dysfunction in Patients with End-Stage Renal Disease. Immune Netw. 2017, 17, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gao, L. Inflammation and Cardiovascular Disease Associated With Hemodialysis for End-Stage Renal Disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 800950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaszubowska, L. Telomere Shortening and Ageing of the Immune System. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. an Off. J. Polish Physiol. Soc. 2008, 59 Suppl 9, 169–186. [Google Scholar]

- Remschmidt, C.; Wichmann, O.; Harder, T. Influenza Vaccination in Patients with End-Stage Renal Disease: Systematic Review and Assessment of Quality of Evidence Related to Vaccine Efficacy, Effectiveness, and Safety. BMC Med. 2014, 12, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddiya, I. Current Knowledge of Vaccinations in Chronic Kidney Disease Patients. Int. J. Nephrol. Renovasc. Dis. 2020, 13, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, I.-K.; Lin, C.-L.; Lin, P.-C.; Liang, C.-C.; Liu, Y.-L.; Chang, C.-T.; Yen, T.-H.; Morisky, D.E.; Huang, C.-C.; Sung, F.-C. Effectiveness of Influenza Vaccination in Patients with End-Stage Renal Disease Receiving Hemodialysis: A Population-Based Study. PLoS One 2013, 8, e58317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.-A.; Chen, C.-I.; Liu, J.-C.; Sung, L.-C. Influenza Vaccination Reduces Hospitalization for Heart Failure in Elderly Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Acta Cardiol. Sin. 2016, 32, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-I.; Kao, P.-F.; Wu, M.-Y.; Fang, Y.-A.; Miser, J.S.; Liu, J.-C.; Sung, L.-C. Influenza Vaccination Is Associated with Lower Risk of Acute Coronary Syndrome in Elderly Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016, 95, e2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.-J.; Chen, C.-H.; Wong, C.-S.; Chen, T.-T.; Wu, M.-Y.; Sung, L.-C. Influenza Vaccination Reduces Incidence of Peripheral Arterial Occlusive Disease in Elderly Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.-C.; Hsu, Y.-P.; Kao, P.-F.; Hao, W.-R.; Liu, S.-H.; Lin, C.-F.; Sung, L.-C.; Wu, S.-Y. Influenza Vaccination Reduces Dementia Risk in Chronic Kidney Disease Patients: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016, 95, e2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, K.M.; Ison, M.G.; Ghossein, C. Practical Guide to Vaccination in All Stages of CKD, Including Patients Treated by Dialysis or Kidney Transplantation. Am. J. kidney Dis. Off. J. Natl. Kidney Found. 2020, 75, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasov, M.; Shanko, A.; Kordyukova, L.; Katlinski, A. Characterization of Inactivated Influenza Vaccines Used in the Russian National Immunization Program. Vaccines 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanko, A.; Shuklina, M.; Kovaleva, A.; Zabrodskaya, Y.; Vidyaeva, I.; Shaldzhyan, A.; Fadeev, A.; Korotkov, A.; Zaitceva, M.; Stepanova, L.; et al. Comparative Immunological Study in Mice of Inactivated Influenza Vaccines Used in the Russian Immunization Program. Vaccines 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MU 3.1.3490-17 “ Study of Population Immunity to Influenza in the Population of the Russian Federation” (Approved by the Chief State Sanitary Doctor of the Russian Federation on October 27, 2017).

- WHO/CDS/CSR/NCS/2002.5 Rev. 1. WHO Manual on Animal Influenza Diagnosis and Surveillance.

- Cui, C.; Schoenfelt, K.Q.; Becker, K.M.; Becker, L. Isolation of Polymorphonuclear Neutrophils and Monocytes from a Single Sample of Human Peripheral Blood. STAR Protoc. 2021, 2, 100845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemchenkov, A.Y. Adequacy of Hemodialysis. Classical Approach. / A.Y. Zemchenkov // Nephrology and Dialysis. – 2001. – Vol. 3, No. 1. – Pp.4-20.

- Sergeeva, M. V; Romanovskaya-Romanko, E.A.; Krivitskaya, V.Z.; Kudar, P.A.; Petkova, N.N.; Kudria, K.S.; Lioznov, D.A.; Stukova, M.A.; Desheva, Y.A. Longitudinal Analysis of Neuraminidase and Hemagglutinin Antibodies to Influenza A Viruses after Immunization with Seasonal Inactivated Influenza Vaccines. Vaccines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, T.; Kumagai, T.; Kashiwagi, Y.; Yoshii, H.; Honjo, K.; Kubota-Koketsu, R.; Okuno, Y.; Suga, S. Cytokine Production in Whole-Blood Cultures Following Immunization with an Influenza Vaccine. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2018, 14, 2990–2998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puspitasari, M.; Sattwika, P.D.; Rahari, D.S.; Wijaya, W.; Hidayat, A.R.P.; Kertia, N.; Purwanto, B.; Thobari, J.A. Outcomes of Vaccinations against Respiratory Diseases in Patients with End-Stage Renal Disease Undergoing Hemodialysis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0281160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishigami, J.; Sang, Y.; Grams, M.E.; Coresh, J.; Chang, A.; Matsushita, K. Effectiveness of Influenza Vaccination Among Older Adults Across Kidney Function: Pooled Analysis of 2005-2006 Through 2014-2015 Influenza Seasons. Am. J. kidney Dis. Off. J. Natl. Kidney Found. 2020, 75, 887–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.-J.; Meng, Y.; Janosczyk, H.; Landolfi, V.; Talbot, H.K. Safety and Immunogenicity of High-Dose Quadrivalent Influenza Vaccine in Adults ≥65 years of Age: A Phase 3 Randomized Clinical Trial. Vaccine 2019, 37, 5825–5834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, L.J.; Layton, J.B.; Krueger, W.S.; Kshirsagar, A. V; Butler, A.M. High-Dose Influenza Vaccine Use among Patients Receiving Hemodialysis in the United States, 2010-2013. Vaccine 2018, 36, 6087–6094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, A.M.; Layton, J.B.; Dharnidharka, V.R.; Sahrmann, J.M.; Seamans, M.J.; Weber, D.J.; McGrath, L.J. Comparative Effectiveness of High-Dose Versus Standard-Dose Influenza Vaccine Among Patients Receiving Maintenance Hemodialysis. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2020, 75, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Xu, X.; Liang, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Chen, R.; Ni, J. Effect of a Booster Dose of Influenza Vaccine in Patients with Hemodialysis, Peritoneal Dialysis and Renal Transplant Recipients: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2016, 12, 2909–2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, K.; Nangaku, M.; Ryuzaki, M.; Yamakawa, T.; Yoshihiro, O.; Hanafusa, N.; Sakai, K.; Kanno, Y.; Ando, R.; Shinoda, T.; et al. Survival and Predictive Factors in Dialysis Patients with COVID-19 in Japan: A Nationwide Cohort Study. Ren. Replace. Ther. 2021, 7, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Yin, J.; He, T.; Zhu, Y.; Li, Y.; Gao, J.; Ye, X.; Hu, L.; Li, Y. Impact of COVID-19 Vaccination on Mortality and Clinical Outcomes in Hemodialysis Patients. Vaccines 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidovic, T.; Schimpf, J.; Abbassi-Nik, A.; Stockinger, R.; Sprenger-Mähr, H.; Lhotta, K.; Zitt, E. Humoral and Cellular Immune Response After a 3-Dose Heterologous SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination Using the MRNA-BNT162b2 and Viral Vector Ad26COVS1 Vaccine in Hemodialysis Patients. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 907615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Karoui, K.; De Vriese, A.S. COVID-19 in Dialysis: Clinical Impact, Immune Response, Prevention, and Treatment. Kidney Int. 2022, 101, 883–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angel-Korman, A.; Peres, E.; Bryk, G.; Lustig, Y.; Indenbaum, V.; Amit, S.; Rappoport, V.; Katzir, Z.; Yagil, Y.; Iaina, N.L.; et al. Diminished and Waning Immunity to COVID-19 Vaccination among Hemodialysis Patients in Israel: The Case for a Third Vaccine Dose. Clin. Kidney J. 2022, 15, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yen, J.-S.; Wang, I.-K.; Yen, T.-H. COVID-19 Vaccination and Dialysis Patients: Why the Variable Response. QJM 2021, 114, 440–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomo, T.; Takei, M.; Matsuyama, M.; Matsuyama, I.; Matsuyama, K. Examination of the Effect of Switching Dialysis Membranes on the Immune Response to Influenza Virus Vaccination in Hemodialysis Patients. Blood Purif. 2023, 52 Suppl 1, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharpé, J.; Peetermans, W.E.; Vanwalleghem, J.; Maes, B.; Bammens, B.; Claes, K.; Osterhaus, A.D.; Vanrenterghem, Y.; Evenepoel, P. Immunogenicity of a Standard Trivalent Influenza Vaccine in Patients on Long-Term Hemodialysis: An Open-Label Trial. Am. J. kidney Dis. Off. J. Natl. Kidney Found. 2009, 54, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleros, C.; Adamidis, K.; Kantartzi, K.; Griveas, I.; Baltsavia, I.; Moustakas, A.; Kalliaropoulos, A.; Fraggedaki, E.; Petra, C.; Damianakis, N.; et al. Dialysis Patients Respond Adequately to Influenza Vaccination Irrespective of Dialysis Modality and Chronic Inflammation. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiselt, J.; Kielberger, L.; Rajdl, D.; Racek, J.; Pazdiora, P.; Malánová, L. Previous Vaccination and Age Are More Important Predictors of Immune Response to Influenza Vaccine than Inflammation and Iron Status in Dialysis Patients. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 2016, 41, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsay, L.C.; Buchan, S.A.; Stirling, R.G.; Cowling, B.J.; Feng, S.; Kwong, J.C.; Warshawsky, B.F. The Impact of Repeated Vaccination on Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Med. 2019, 17, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khurana, S.; Hahn, M.; Coyle, E.M.; King, L.R.; Lin, T.-L.; Treanor, J.; Sant, A.; Golding, H. Repeat Vaccination Reduces Antibody Affinity Maturation across Different Influenza Vaccine Platforms in Humans. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.J.; Forrest, S.; Ackley, D.H.; Perelson, A.S. Variable Efficacy of Repeated Annual Influenza Vaccination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999, 96, 14001–14006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skowronski, D.M.; Chambers, C.; Sabaiduc, S.; De Serres, G.; Winter, A.-L.; Dickinson, J.A.; Krajden, M.; Gubbay, J.B.; Drews, S.J.; Martineau, C.; et al. A Perfect Storm: Impact of Genomic Variation and Serial Vaccination on Low Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness During the 2014-2015 Season. Clin. Infect. Dis. an Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2016, 63, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skowronski, D.M.; Chambers, C.; De Serres, G.; Sabaiduc, S.; Winter, A.-L.; Dickinson, J.A.; Gubbay, J.B.; Fonseca, K.; Drews, S.J.; Charest, H.; et al. Serial Vaccination and the Antigenic Distance Hypothesis: Effects on Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness During A(H3N2) Epidemics in Canada, 2010–2011 to 2014–2015. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 215, 1059–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

A. Distribution of volunteers depending on individual antibody titers according to HI data on Day 0 (before vaccination). The data are presented in the box-plot format: median, quartiles, minimum and maximum titer values are marked. The horizontal dotted line corresponds to 40 - the minimum protective level of ABs. B. Dynamics of virus-specific antibodies titers in the sera of vaccinated hemodialysis patients within 6 months after vaccination. The graphs show Mean ±SD of Log2 AB titres measured by HI and MNA. GP- Grippol plus, SG – Sovigripp, UQ- Ultrix Quadri.

Figure 1.

A. Distribution of volunteers depending on individual antibody titers according to HI data on Day 0 (before vaccination). The data are presented in the box-plot format: median, quartiles, minimum and maximum titer values are marked. The horizontal dotted line corresponds to 40 - the minimum protective level of ABs. B. Dynamics of virus-specific antibodies titers in the sera of vaccinated hemodialysis patients within 6 months after vaccination. The graphs show Mean ±SD of Log2 AB titres measured by HI and MNA. GP- Grippol plus, SG – Sovigripp, UQ- Ultrix Quadri.

Figure 2.

Changes in the subpopulation composition of peripheral blood B and Tfh cells at the early time points after IIV administration in hemodialysis patients. B-cell subpopulation dynamics (A), Tfh subpopulation dynamics (B), Activated Tfh subpopulation dynamics (C). Grey lines indicate individual population dynamics for each patient; colored lines show mean ± SE. Statistical analysis was performed using paired Wilcoxon’s test (*: p < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Changes in the subpopulation composition of peripheral blood B and Tfh cells at the early time points after IIV administration in hemodialysis patients. B-cell subpopulation dynamics (A), Tfh subpopulation dynamics (B), Activated Tfh subpopulation dynamics (C). Grey lines indicate individual population dynamics for each patient; colored lines show mean ± SE. Statistical analysis was performed using paired Wilcoxon’s test (*: p < 0.05).

Figure 3.

A. Antigen-specific B cell response in HD patients (ELISPOT). Dynamics of quantity of antigen-specific antibody-secreting B cells (Mean ±SEM), Mean spot size dynamics (Mean ±SEM). B. Lg fold change (FC) in quantity of antigen-specific antibody-secreting B-cells on day 7 relative to the pre-vaccination amounts (day 0). Data were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05, as determined by one way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. C. Representative ELISPOT pictures of two volunteers. D. Pearson’s correlation analysis for the percentage of circulating Tfh1 and plasmablasts and the number of antigen-specific B-cells measured with the ELISPOT.

Figure 3.

A. Antigen-specific B cell response in HD patients (ELISPOT). Dynamics of quantity of antigen-specific antibody-secreting B cells (Mean ±SEM), Mean spot size dynamics (Mean ±SEM). B. Lg fold change (FC) in quantity of antigen-specific antibody-secreting B-cells on day 7 relative to the pre-vaccination amounts (day 0). Data were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05, as determined by one way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. C. Representative ELISPOT pictures of two volunteers. D. Pearson’s correlation analysis for the percentage of circulating Tfh1 and plasmablasts and the number of antigen-specific B-cells measured with the ELISPOT.

Figure 4.

Dynamics of post-vaccination CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell response in HD patients. The cumulative values of antigen-specific polyfunctional (IFNγ+IL2+TNFα-, IFNγ+IL2-TNFα+, IFNγ-IL2+TNFα+, IFNγ+IL2+TNFα+) cytokine-producing CD4+ and CD8+ Tem expressed as % of the total number of Tem (CD45RA-CCR7-) cells. The symbol * indicates significant differences from the values obtained on day 0, the paired Wilcoxon test (*:p < 0.05). Grey lines indicate individual population dynamics for each patient; colored lines show mean ± SE.

Figure 4.

Dynamics of post-vaccination CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell response in HD patients. The cumulative values of antigen-specific polyfunctional (IFNγ+IL2+TNFα-, IFNγ+IL2-TNFα+, IFNγ-IL2+TNFα+, IFNγ+IL2+TNFα+) cytokine-producing CD4+ and CD8+ Tem expressed as % of the total number of Tem (CD45RA-CCR7-) cells. The symbol * indicates significant differences from the values obtained on day 0, the paired Wilcoxon test (*:p < 0.05). Grey lines indicate individual population dynamics for each patient; colored lines show mean ± SE.

Figure 5.

Dynamics of virus-specific antibodies titers in the sera of vaccinated hemodialysis patients within 12 months after vaccination. The graphs show the AB measured by HI as box and whiskers plots with 5-95% percentile. A. H1 - A/Victoria/4879/2022 (A(H1N1)pdm09), B. H3 -A/Thailand/8/2022 (H3N2), C. BV- B/Austria/1359417/2021 (B/Victoria), D. BY-B/Phuket/3073/13 (B/Yamagata). B 1Y – Group of HD patients vaccinated in 2023/2024; 2Y– Group of HD patients vaccinated subsequently in 2022/2023 and 2023/2024 seasons. Data were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05, as determined by one-or two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test (*: р < 0.05, **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001).

Figure 5.

Dynamics of virus-specific antibodies titers in the sera of vaccinated hemodialysis patients within 12 months after vaccination. The graphs show the AB measured by HI as box and whiskers plots with 5-95% percentile. A. H1 - A/Victoria/4879/2022 (A(H1N1)pdm09), B. H3 -A/Thailand/8/2022 (H3N2), C. BV- B/Austria/1359417/2021 (B/Victoria), D. BY-B/Phuket/3073/13 (B/Yamagata). B 1Y – Group of HD patients vaccinated in 2023/2024; 2Y– Group of HD patients vaccinated subsequently in 2022/2023 and 2023/2024 seasons. Data were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05, as determined by one-or two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test (*: р < 0.05, **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001).

Figure 6.

Dynamics of virus-specific antibodies titers in the sera of vaccinated hemodialysis patients with-in 12 months after vaccination. The graphs show the AB titers measured by MNA as box and whiskers plots with 5-95% percentile. A. H1 - A/Victoria/4879/2022 (A(H1N1)pdm09), B. H3 -A/Thailand/8/2022 (H3N2), C. BV- B/Austria/1359417/2021 (B/Victoria), D. BY-B/Phuket/3073/13 (B/Yamagata). B 1Y – Group of HD patients vaccinated in 2023/2024; 2Y– Group of HD patients vaccinated subsequently in 2022/2023 and 2023/2024 seasons. Data were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05, as determined by one-or two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test (*: р < 0.05, **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001).

Figure 6.

Dynamics of virus-specific antibodies titers in the sera of vaccinated hemodialysis patients with-in 12 months after vaccination. The graphs show the AB titers measured by MNA as box and whiskers plots with 5-95% percentile. A. H1 - A/Victoria/4879/2022 (A(H1N1)pdm09), B. H3 -A/Thailand/8/2022 (H3N2), C. BV- B/Austria/1359417/2021 (B/Victoria), D. BY-B/Phuket/3073/13 (B/Yamagata). B 1Y – Group of HD patients vaccinated in 2023/2024; 2Y– Group of HD patients vaccinated subsequently in 2022/2023 and 2023/2024 seasons. Data were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05, as determined by one-or two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test (*: р < 0.05, **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001).

Figure 7.

IFNγ production in whole-blood cell cultures stimulated with the split vaccine antigens. A. H1 - A/Victoria/4879/2022 (A(H1N1)pdm09), B. H3 -A/Thailand/8/2022 (H3N2), C. BV- B/Austria/1359417/2021 (B/Victoria), D. BY-B/Phuket/3073/13 (B/Yamagata). B 1Y – Group of HD patients vaccinated in 2023/2024; 2Y– Group of HD patients vaccinated subsequently in 2022/2023 and 2023/2024 seasons. The left column shows the antigen-specific IFNγ concentrations (pg/ml) after subtracting the baseline. The right column shows the post-vaccination Log₁₀ fold change (FC) of IFNγ concentrations on day 7 relative to day 0. Data were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05, as determined by unpaired t-test(*: р < 0.05).

Figure 7.

IFNγ production in whole-blood cell cultures stimulated with the split vaccine antigens. A. H1 - A/Victoria/4879/2022 (A(H1N1)pdm09), B. H3 -A/Thailand/8/2022 (H3N2), C. BV- B/Austria/1359417/2021 (B/Victoria), D. BY-B/Phuket/3073/13 (B/Yamagata). B 1Y – Group of HD patients vaccinated in 2023/2024; 2Y– Group of HD patients vaccinated subsequently in 2022/2023 and 2023/2024 seasons. The left column shows the antigen-specific IFNγ concentrations (pg/ml) after subtracting the baseline. The right column shows the post-vaccination Log₁₀ fold change (FC) of IFNγ concentrations on day 7 relative to day 0. Data were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05, as determined by unpaired t-test(*: р < 0.05).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of subjects (HD patients).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of subjects (HD patients).

| Characteristic |

Total, n=22 |

| Age, mean (min-max) |

64 (27-83) |

| Female, n (%) |

5 (22,73) |

| Male, n (%) |

17 (77,27) |

| Primary kidney diseases: |

|

| Polycystic kidney disease, n (%) |

8 (36,36) |

| Abnormality of kidney development, n (%) |

4 (18,18) |

| Chronic glomerulonephritis, n (%) |

4 (18,18) |

| Chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis, n (%) |

3 (13,64) |

| Type 1 diabetes, n (%) |

1 (4,55) |

| Gouty nephritis, n (%) |

1 (4,55) |

| Nephrectomy, n (%) |

1 (4,55) |

| Time on dialysis, years, mean (min-max) |

6,1 (0,2-18,2) |

| spKt/V, mean (95%CI) |

1,47 (1,37-1,58) |

| Laboratory parameters |

|

| Hgb, g/L, mean (95%CI) |

113,9 (107,1-120,6) |

| Albumine, g/L, mean (95%CI) |

37,8 (36,82-38,78) |

| Р, mmol/L, mean (95%CI) |

2,67 (2,49-2-85) |

| Са, mmol/L (95%CI) |

2,16 (2,05-2,27) |

| Vaccination |

|

| Sovigripp, n (%) |

7 (31,82) |

| Grippol plus, n (%) |

9 (40,90) |

| Ultrix Quadri, n (%) |

6 (27,27) |

Table 2.

Immunological efficacy of the IIVs in hemodialysis patients (HI).

Table 2.

Immunological efficacy of the IIVs in hemodialysis patients (HI).

| Vaccine |

UQ (n=6) |

GP (n=9) |

SG (n=7) |

CPMP Threshold value* |

| Percentage of volunteers with AB titer ≥ 1:40, % (CI) Before vaccination (Day 0) |

H1 |

0 (0, 0) |

22 (0, 49) |

43 (6, 80) |

|

| H3 |

17 (0, 46) |

44 (12, 77) |

29 (0, 62) |

| BV |

17 (0, 46) |

11 (0, 32) |

14 (0, 40) |

| BY |

0 (0, 0) |

11 (0, 32) |

0 (0, 0) |

| Percentage of volunteers with AB titer ≥ 1:40 Post vaccination (Day 28) (Seroprotection rate), % (CI) |

H1 |

100 (100, 100) |

100 (100, 100) |

71 (38, 105) |

> 60% |

| H3 |

100 (100, 100) |

100 (100, 100) |

100 (100, 100) |

| BV |

67 (29, 104) |

78 (51, 105) |

71 (38, 105) |

| BY |

67 (29, 104) |

44 (12, 77) |

43 (6, 80) |

| Fold increase of AB titer (Day 28) (CI) |

H1 |

32 (9, 113) |

16 (7.1, 36.2) |

5.4 (1.7, 16.9) |

> 2 |

| H3 |

25.4 (14, 45) |

10.1 (5.3, 19.1) |

6.6 (1.9, 22.9) |

| BV |

5 (1.2, 21.1) |

12.7 (4.1, 39.4) |

6.6 (2.7, 15.7) |

| BY |

9 (2.9, 27.9) |

22.2 (1.1, 4.3) |

2.4 (1, 6.1) |

| Percentage of volunteers with Seroconversion rate, % (CI) |

H1 |

83 (54, 113) |

89 (68, 100) |

57 (20, 94) |

> 30% |

| H3 |

100 (100, 100) |

89 (68, 100) |

71 (38, 100) |

| BV |

67 (29, 100) |

78 (51, 100) |

71 (38, 100) |

| BY |

83 (54, 100) |

33 (3, 64) |

43 (6, 80) |

Table 3.

Characteristics of the neutralizing antibody response to IIV vaccination in hemodialysis patients (MNA).

Table 3.

Characteristics of the neutralizing antibody response to IIV vaccination in hemodialysis patients (MNA).

| Vaccine |

UQ (n=6) |

GP (n=9) |

SG (n=7) |

CPMP Threshold value* |

| Percentage of volunteers with AB titer ≥ 1:40, % (CI) Before vaccination (Day 0) |

H1 |

0 (0, 0) |

11 (0, 32) |

14 (0, 40) |

|

| H3 |

0 (0, 0) |

0 (0, 0) |

0 (0, 0) |

| BV |

17 (0, 46) |

11 (0, 32) |

14 (0, 40) |

| BY |

17 (0, 46) |

22 (0, 49) |

0 (0, 0) |

| Percentage of volunteers with AB titer ≥ 1:40 Post vaccination (Day 28) (Seroprotection rate), % (CI) |

H1 |

100 (100, 100) |

89 (68, 100) |

57 (20, 94) |

> 60% |

| H3 |

83 (54, 100) |

56 (23, 88) |

14 (0, 40) |

| BV |

50 (10, 90) |

56(23, 88) |

57(20, 94) |

| BY |

83 (54, 100) |

44(12, 77) |

43(6, 80) |

| Fold increase of AB titer (Day 28) (CI) |

H1 |

22.6 (8, 63.9) |

10.1 (4.9, 20.6) |

3.6(1.9, 6.8) |

> 2 |

| H3 |

7.1 (3.2, 16.1) |

07.4 (4.2, 13.2) |

3 (1.4, 6.5) |

| BV |

4.5 (1, 19.4) |

5.4 (1.9, 15.8) |

5.9 (1.8, 19.4) |

| BY |

10.1 (4.4, 23.2) |

1.7 (0.9, 3.2) |

3 (1.2, 7.5) |

| Percentage of volunteers with Seroconversion rate, % (CI) |

H1 |

100 (100, 100) |

89 (68, 109) |

57 (20, 94) |

> 30% |

| H3 |

83 (54, 100) |

89 (68, 109) |

57 (20, 94) |

| BV |

50 (10, 90) |

67 (36, 97) |

71 (38, 100) |

| BY |

83 (54, 100) |

22 (0, 49) |

43 (6, 80) |

Table 4.

Immunological efficacy of the IIVs in HD patients in comparison to groups of healthy volunteers (HAI).

Table 4.

Immunological efficacy of the IIVs in HD patients in comparison to groups of healthy volunteers (HAI).

| Vaccine |

HD (n=22) |

Healthy

>60 (n=42) |

Healthy

18-60 (n=34) |

| Procentage of volunteers with AB titer ≥ 1:40, % (CI) Before vaccination (Day 0) |

H1 |

23 (5, 40)1, 2

|

38 (23, 53)1

|

47 (30, 64)2

|

| H3 |

32 (12, 51) |

24 (11, 37) |

29 (14, 45) |

| BV |

14 (0#, 28) |

10 (1, 18) |

21 (7, 34) |

| BY |

5 (0, 13) |

5 (0, 11) |

24 (9, 38) |

| Procentage of volunteers with AB titer ≥ 1:40 Post vaccination (Day 28) (Seroprotection rate), % (CI) |

H1 |

91 (79, 103) |

86 (75, 96) |

94 (86, 102) |

| H3 |

100 (100, 100) |

83 (72, 95) |

91 (82, 101) |

| BV |

73 (54, 91) |

38 (23, 53) |

68 (52, 83) |

| BY |

50 (29, 71) |

31 (17, 45) |

56 (39, 73) |

| Fold increase of AB titer (Day 28) (CI) |

H1 |

13.7 (7.2, 26) |

6.9 (4.2, 11.4) |

11.5 (5.7, 23.2) |

| H3 |

11.3 (6.7, 19.2) |

5.6 (3.6, 8.9) |

10.2 (5.4, 19.3) |

| BV |

8 (4.1, 15.4) |

2.3 (1.8, 3) |

3.3 (2.1, 5.1) |

| BY |

3.3 (1.9, 5.8) |

2.4 (1.7, 3.2) |

2.2 (1.4, 3.3) |

| Procentage of volunteers with Seroconversion rate, % (CI) |

H1 |

77 (60, 95) |

67 (52, 81) |

74 (59, 88) |

| H3 |

86(72, 101) |

60 (45, 74) |

76 (62, 91) |

| BV |

73 (54, 91) |

36 (21, 50) |

50 (33, 67) |

| BY |

50 (29, 71) |

36 (21, 50) |

32( 17, 48) |

Table 5.

Baseline characteristics of subjects (HD patients 2023-2024).

Table 5.

Baseline characteristics of subjects (HD patients 2023-2024).

| Characteristic |

Total, n71. |

| Age, mean (min-max) |

57,6 (25-85) |

| Female, n (%) |

35 (49,3) |

| Male, n (%) |

36 (50,7) |

|

Primary kidney diseases: |

|

| Chronic glomerulonephritis, n (%) |

26 (36,62) |

| Polycystic kidney disease, n (%) |

13 (18,31) |

| Chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis, n (%) |

11 (15,49) |

| Hypertension, n (%) |

4 (5,63) |

| Type 1 diabetes, n (%) |

3 (4,23) |

| Type 2 diabetes, n (%) |

3 (4,23) |

| Gouty nephritis, n (%) |

3 (4,23) |

| Alport syndrome, n (%) |

3 (4,23) |

| Connective tissue disease, n (%) |

3 (4,23) |

| Abnormality of kidney development, n (%) |

1 (1,41) |

| Kidney Cr, Nephrectomy, n (%) |

1 (1,41) |

| spKt/V, mean (95%CI) |

1,55 (1,49-1,60) |

| Laboratory parameters |

|

| Hgb, g/L, mean (95%CI) |

112,20 (109,50-114,90) |

| Albumine, g/L, mean (95%CI) |

40,62 (39,89-41,35) |

| Р, mmol/L, mean (95%CI) |

1,81 (1,67-1,96) |

| Са, mmol/L (95%CI) |

2,24 (2,19-2,29) |

| Vaccination |

|

| First year vaccination, n (%) |

28 (39,44) |

| Second year vaccination, n (%) |

34 (47,89) |

| Third year vaccination, n (%) |

9 (12,67) |

| Flu-M Tetra, n (%) |

71 (100) |

Table 6.

- Immunogenic efficacy of vaccination in dialysis patients depending on the previous vaccination status (season 2023-2024, HI data).

Table 6.

- Immunogenic efficacy of vaccination in dialysis patients depending on the previous vaccination status (season 2023-2024, HI data).

| Vaccine |

All (n=58) |

1Y (n=22) |

2Y (n=29) |

CPMP Threshold value* |

| Percentage of volunteers with AB titer ≥ 1:40, % (CI) Before vaccination (Day 0) |

H1 |

33 (21, 45) |

18 (2, 34) |

38 (20, 56) |

|

| H3 |

40 (27, 52) |

32 (12, 51) |

41 (23, 59) |

| BV |

26 (15, 37) |

5 (0, 13) |

41 (23, 59) |

| BY |

40 (27, 52) |

23 (5, 40) |

55 (37, 73) |

| Percentage of volunteers with AB titer ≥ 1:40 Post vaccination (Day 28) (Seroprotection rate), % (CI) |

H1 |

91 (84, 99) |

91 (79, 100) |

93 (84, 100) |

> 60% |

| H3 |

83 (73, 92) |

86 (72, 100) |

79 (65, 94) |

| BV |

71 (59, 82) |

55 (34, 75) |

86 (74, 99) |

| BY |

86 (77, 95) |

91 (79, 100) |

90 (79, 100) |

| Fold increase of AB titer (Day 28) (CI) |

H1 |

7.2 (5.1, 10) |

13.2 (7.9, 22) |

5.7 (3.5, 9.2) |

> 2 |

| H3 |

5 (3.7, 6.8) |

8.8 (5.3, 15) |

3.9 (2.6, 5.9) |

| BV |

4.8 (3.5, 6.6) |

5.8 (3.2, 11) |

4.5 (2.9, 6.9) |

| BY |

5.1 (3.6, 7.3) |

11.7 (6.3, 22) |

3.4 (2.3, 5) |

| Percentage of volunteers with Seroconversion rate, % (CI) |

H1 |

72 (61, 84) |

86 (72, 100) |

72 (56, 89) |

> 30% |

| H3 |

67 (55, 79) |

86 (72, 100) |

62 (44, 80) |

| BV |

62 (50, 75) |

68 (49, 88) |

62 (44, 80) |

| BY |

59 (46, 71) |

86 (72, 100) |

41 (23, 59) |

Table 7.

Immunogenic efficacy of vaccination in dialysis patients depending on the previous vaccination status (season 2023-2024, MNA data).

Table 7.

Immunogenic efficacy of vaccination in dialysis patients depending on the previous vaccination status (season 2023-2024, MNA data).

| Vaccine |

All (n=58) |

1Y (n=22) |

2Y (n=29) |

CPMP Threshold value* |

| Percentage of volunteers with AB titer ≥ 1:40, % (CI) Before vaccination (Day 0) |

H1 |

53 (41, 66) |

27 (9, 46) |

69 (52, 86) |

|

| H3 |

9 (1, 16) |

0 (0, 0) |

17 (3, 31) |

| BV |

24 (13, 35) |

5 (0, 13) |

41 (23, 59) |

| BY |

19 (9, 29) |

14 (0, 28) |

24 (9, 40) |

| Percentage of volunteers with AB titer ≥ 1:40 Post vaccination (Day 28) (Seroprotection rate), % (CI) |

H1 |

97 (92, 100) |

91 (79, 100) |

100 (100, 100) |

> 60% |

| H3 |

57 (44, 70) |

59 (39, 80) |

66 (48, 83) |

| BV |

81 (71, 91) |

68 (49, 88) |

90 (79, 100) |

| BY |

76 (65, 87) |

82 (66, 98) |

76 (60, 91) |

| Fold increase of AB titer (Day 28) (CI) |

H1 |

6.9 (4.9, 9.8) |

15.5 (8.5, 28) |

4.6 (3.1, 6.9) |

> 2 |

| H3 |

4.6 (3.5, 6.1) |

6.2 (3.5, 11) |

4 (2.8, 5.7) |

| BV |

6.3 (4.4, 9) |

7.5 (3.9, 14) |

6 (3.7, 9.8) |

| BY |

5.1 (3.9, 6.8) |

8.8 (5.8, 13) |

4.3 (2.9, 6.3) |

| Percentage of volunteers with Seroconversion rate, % (CI) |

H1 |

74 (63, 85) |

91 (79, 100) |

66 (48, 83) |

> 30% |

| H3 |

64 (51, 76) |

64 (44, 84) |

66 (48, 83) |

| BV |

69 (57, 81) |

73 (54, 91) |

69 (52, 86) |

| BY |

66 (53, 78) |

86 (72, 100) |

59 (41, 77) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).