1. Introduction

In 2023, the World Health Organization (WHO) once again classified tuberculosis as the leading cause of death from a single infectious agent. It was estimated that 10.8 million people were infected with tuberculosis leading to 1.25 million deaths. Among the infected individuals, 6.1% were co-infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). In the same year, approximately 400,000 individuals with tuberculosis (TB) were estimated to have developed multidrug resistance or rifampicin resistance, and 44% of these cases received treatment. Among individuals with drug-susceptible tuberculosis, treatment demonstrated an efficacy rate of 88% [

1]. Tuberculosis treatment consists of a combination of four drugs and requires a minimum duration of six months, which represents a challenge, as failure to adhere to the regimen may lead to the development of bacterial drug resistance. Currently, there are already multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains, defined as those resistant to the two most effective first-line drugs, isoniazid and rifampicin (RIF). In addition, extensively drug-resistant (XDR) strains exist, characterized by resistance to at least two second-line drugs [

2,

3].

Tuberculosis is typically diagnosed weeks or even months after the onset of infection, due to delayed or limited access to healthcare services and/or the presence of nonspecific symptoms, which increases the risk of transmission. Early diagnosis is crucial to enable effective treatment and, consequently, reduce new infections, as well as disease-related morbidity and mortality [

3,

4,

5]. Early TB diagnosis is aligned with Sustainable Development Goal 3, established by the United Nations, which aims to ensure healthy lives by promoting access to healthcare and combating epidemics caused by various diseases, including tuberculosis, by 2030 [

6].

The WHO, aiming to reduce tuberculosis cases and ultimately eradicate the disease, endorses and recommends the use of specific diagnostic methods for tuberculosis in its guidelines [

2,

7]. For a long time, the primary diagnostic methods for TB were smear microscopy and bacterial culture. Currently, molecular techniques, due to their higher sensitivity and specificity, have gained prominence in laboratories and received WHO support [

7]. Moreover, they also exhibit a shorter turnaround time (TAT), defined as the total time between the test request and the delivery of the result, which is crucial for laboratory diagnosis, as it directly affects the promptness of clinical decision-making and the initiation of treatment [

8].

Techniques such as automated nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT), loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP), lateral flow urine lipoarabinomannan assay (LF-LAM), line probe assay (LPA), next-generation sequencing (NGS), and interferon-gamma release assays (IGRA) have been recommended by the WHO and represent promising alternatives [

7].

In this context, this article aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the main laboratory and diagnostic methods for tuberculosis, emphasizing their applicability according to healthcare complexity, clinical presentation, and epidemiological context, as well as their role in integrated diagnostic workflows.

2. Search Strategy

This work is a narrative literature review with a descriptive and qualitative approach. The search for references was conducted in major scientific databases, primarily PubMed, complemented by access to journals available through institutional subscriptions. The search strategy used the following English-language descriptors: tuberculosis, diagnosis, diagnostic tests, sensitivity, and specificity. Scientific articles—both original studies and review papers—were included when they addressed diagnostic methods for tuberculosis and provided data on sensitivity, specificity, turnaround time, feasibility, or clinical applicability. Publications such as editorials, letters, case reports, and studies not focused on diagnostic performance were excluded. To ensure completeness, official guidelines, technical documents, and publicly available materials from recognized public health organizations were also consulted. Because this study is based exclusively on publicly accessible literature and does not involve human participants, ethical approval was not required.

3. Classic Methods

3.1. Bacterial Culture

Culture is considered the gold standard method for the diagnosis of tuberculosis and the detection of drug resistance, demonstrating high sensitivity and specificity [

9,

10]. This method allows the identification of different

Mycobacterium tuberculosis species, even when bacterial cell counts are low [

11]. Through culture, it is possible to multiply and isolate the mycobacteria from the inoculation of a clinical sample on specific media [

12].

Classical culture methods use solid media, incubation in bacteriological incubators at temperatures between 35 °C and 37 °C, and visual colony reading. However, automated systems have also been developed, which utilize liquid culture media monitored by computerized systems capable of detecting cellular growth [

12]. The BACTEC™ Mycobacterial Growth Indicator Tube 960 (MGIT) system is currently one of the most widely used. These systems exhibit higher sensitivity than solid media cultures and can be applied to most clinical samples [

12,

13,

14]. In a retrospective study by Boldi et al. (2023), mycobacterial culture demonstrated a sensitivity of 98.8% and specificity of 100% for diagnosing pulmonary tuberculosis. When comparing test sensitivity across different sample types, tracheal aspirates (97%) outperformed bronchoscopy samples (63.6%) [

15].

Despite its many advantages, it is important to consider some challenges associated with the bacterial culture method. Strict biosafety practices are required, necessitating specialized equipment, trained personnel, and a biosafety level 3 laboratory due to the high infectious risk [

15]. The bacterial growth time also poses a limitation for the early diagnosis of TB, as obtaining results can take between 14 days and 8 weeks [

12].

Drug susceptibility testing (DST) is also performed using culture-based methods to determine whether

M. tuberculosis isolates are susceptible or resistant to first-line and second-line antituberculosis drugs. DST may be carried out manually on solid media or through automated liquid systems. Among these, the BACTEC™ MGIT™ 960 system is widely employed because it enables both the detection of

M. tuberculosis and the performance of DST. The system uses tubes containing predefined drug concentrations and a fluorescence-based oxygen sensor; as bacterial growth consumes oxygen, fluorescence increases and is continuously monitored and compared to a growth control, allowing the instrument to classify isolates as susceptible or resistant [

12,

16].

3.2. Smear Microscopy

Smear microscopy is still a widely used technique for tuberculosis diagnosis; however, it does not allow for the identification of the mycobacterial species. High-complexity laboratories are not required to perform smear microscopy. It is a simple technique; however, it has low sensitivity, requiring a minimum concentration of 1,000 CFU/mL in the clinical sample to be considered positive. Samples with low bacterial counts may yield negative results due to the difficulty of detecting bacilli [

17]. Thus, collecting more than one sample per patient can improve the test’s sensitivity [

18]. The method also shows low reproducibility, considering that sputum collection quality, slide preparation, staining, and microscopy procedures are critical factors that can directly affect the results [

9].

This technique employs a special bacteriological staining method to identify acid-fast organisms, primarily mycobacteria. One of the most commonly used staining methods is Ziehl–Neelsen, in which bacteria present in the sample are stained with fuchsin [

2,

19]. Fuchsin is a dye that binds to the lipids in the bacterial cell wall, forming complexes that confer resistance to decolorization by acid-alcohol solutions. This characteristic gives mycobacteria their designation as acid-fast bacilli [

12]. In the study by Singhal and Myneedu (2015), the Ziehl–Neelsen stain demonstrated a sensitivity of 22–43% [

19]. Deng et al. (2021) reported similar sensitivity values, ranging from 20 to 30% [

20].

When reading smear microscopy slides, at least one hundred fields must be examined, in which pulmonary cellular elements are observed (leukocytes, mucous fibers, and ciliated cells) [

12]. Fluorescence microscopy using auramine stain shows approximately 10% higher sensitivity compared to conventional light microscopy. However, more accessible options exist, such as light-emitting diode fluorescence microscopy. This method uses long-lasting lamps, requires less energy, and has lower operational costs, offering greater sensitivity in resource-limited settings [

21].

4. Latent Tuberculosis Diagnosis

Latent tuberculosis infection occurs when an individual is exposed to

M. tuberculosis, resulting in a sustained immune response. In this condition, the individual remains asymptomatic, and no bacterial replication takes place [

22,

23]. When the immune system fails or the host becomes immunocompromised, the bacteria may reactivate and cause disease [

24]. Approximately 5–15% of infected individuals progress to active tuberculosis, at which point the disease becomes contagious [

22].

For the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis, the tuberculin skin test (TST), or Mantoux test, can be used. The test is based on a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction that occurs after the intradermal injection, on the anterior surface of the forearm, of a purified protein derivative (PPD) from the mycobacteria. The PPD induces a local inflammatory response, and the maximum diameter of the resulting induration is measured 48 to 72 hours after injection. However, this test has low specificity because the antigens present in PPD can also be found in other mycobacteria and in the Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccine [

11,

25,

26,

27].

TST is less sensitive in immunocompromised patients, such as those using immunosuppressive agents and individuals infected with HIV. Due to these multiple factors that influence the test reaction, the cutoff value generally varies [

28]. In 2022, three additional types of tuberculin were approved by the WHO, containing two

M. tuberculosis specific proteins (ESAT-6 and CFP10). The Diaskin test, the C-TB skin test, and the C-TST offer higher specificity; however, none of them have been approved by regulatory authorities to date [

4,

25,

29].

Other methods used for the diagnosis of latent infection include IGRA assays. These tests incubate blood samples with

M. tuberculosis specific antigens (ESAT-6 and CFP-10) and measures Interferon-Gamma (IFN-γ) production by lymphocytes sensitized to these antigens [

11,

30]. IFN-γ is quantified either by an enzyme immunoassay (ELISA) or by quantifying IFN-γ–secreting antigen-specific cells using an enzyme-linked immunospot assay (ELISpot) [

31]. Compared with the tuberculin skin test, IGRA demonstrates greater accuracy and is not affected by the BCG vaccine [

3,

31,

32]. Several IGRAs are currently commercially available, with the QuantiFERON-TB Gold Plus (Qiagen) and the T-SPOT.TB (Oxford Immunotec) assays being the most widely used [

11].

The tuberculin skin test has the advantage of being less expensive, not requiring a laboratory environment, and being easier to use in screening settings [

32]. On the other hand, IGRAs do not require a second visit for result reading and show fewer false-negative results in immunosuppressed individuals. In addition, they are specific for

M. tuberculosis infection and therefore do not yield false-positive results in BCG-vaccinated individuals or those infected with nontuberculous mycobacteria (with the exception of

Mycobacterium kansasii,

Mycobacterium szulgai,

Mycobacterium marinum, and

Mycobacterium riyadhense, which contain the ESAT-6 antigen) [

32,

33].

There are 13 in vitro tests for the diagnosis of TB infection currently under development or being marketed, but not yet approved by the WHO. Of these, 12 are whole-blood IGRAs, and one of them—the GBTsol Latent TB Test Kit—uses a newly patented technology. In addition, five new skin tests and simplified versions of IGRAs based on lateral flow technology are in development. These tests are expected to offer higher specificity and to be suitable for use in peripheral healthcare units, thereby expediting TB diagnosis in these populations [

28].

5. Lateral Flow Assays

In 2019, the Alere Determine TB-LAM Ag lateral flow assay, performed on urine samples, was recommended by the WHO to assist in the diagnosis of active tuberculosis in individuals infected with HIV [

34]. Therefore, the Alere Determine TB-LAM Ag assay is performed manually by applying 60 µL of urine to the test strip and incubating it at room temperature for 25 minutes. The result is visualized through the presence of bands on the strip—one test band and one control band—whose intensity is compared with the band intensities on a reference scale provided by the manufacturer [

7].

Lipoarabinomannan (LAM) is a glycolipid present in the cell wall of

M. tuberculosis and can be used as a biomarker for TB diagnosis [

35]. During blood filtration in the kidneys, glomerular endothelial cells form a network with pore sizes sufficient to allow the passage of membrane-derived molecules from

M. tuberculosis or extracellular vesicles carrying LAM, which are subsequently excreted in the urine [

36]. This type of test demonstrates higher sensitivity and specificity in HIV-positive individuals, particularly those with CD4 cell counts below 100 cells/µL, and is therefore not recommended for other groups [

23].

Recently, another test was developed with the aim of improving the sensitivity while maintaining the specificity of the Alere Determine TB-LAM Ag assay. The Fujifilm SILVAMP TB LAM test (FujiLAM) employs a pair of high-affinity monoclonal antibodies directed against the 5-methylthio-D-xylopyranose epitope, which is specific to

M. tuberculosis, and incorporates a silver amplification step that enhances the visibility of the test and control lines on the lateral flow assay. This approach enables the detection of LAM concentrations approximately 30 times lower than those detectable with the Alere Determine TB-LAM Ag test in urine samples. FujiLAM has demonstrated approximately 30% higher sensitivity in HIV-positive patients compared with the Alere Determine TB-LAM Ag assay, while maintaining a specificity of 95.7% [

37,

38,

39].

6. Molecular Methods

Molecular methods provide several advantages in the laboratory diagnosis of tuberculosis, particularly regarding the rapid turnaround time, test standardization, and reduced biosafety requirements compared with culture-based methods using liquid or solid media.

The WHO has supported the expanded use of rapid molecular tests to detect both tuberculosis and antimicrobial resistance as part of a strategy to improve diagnostic accessibility and ensure more comprehensive and equitable care for individuals with TB. This is because early and accurate detection of the disease enables prompt initiation of appropriate treatment, contributing to more effective tuberculosis control [

12].

6.1. Automated Nucleic Acid Amplification Tests (NAAT)

These methods detect TB and mutations associated with resistance to first-line antimicrobials, such as rifampicin and isoniazid, as well as to second-line agents, including fluoroquinolones, ethionamide, and amikacin, yielding results within a few hours. The efficiency of these approaches is particularly valuable in settings where large numbers of tests are performed daily and offers a suitable alternative for laboratories with limited resources [

13,

40,

41].

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) is currently the most widely used technique and can be performed using automated platforms such as Xpert

® MTB/RIF, Xpert

® MTB/RIF Ultra (Cepheid), and Truenat MTB (Molbio) [

42]. PCR enables the amplification of specific DNA segments millions of times through the use of primers. This high amplification capacity confers excellent sensitivity, allowing the detection of very small amounts of genetic material [

43,

44].

The Xpert

® MTB/RIF assay, developed by Cepheid Innovations (USA), represented a major advance in the diagnosis of tuberculosis and in the detection of rifampicin resistance, as it is a simple and rapid test capable of delivering results in up to two hours [

9,

45]. This assay is an automated, real-time, semi-quantitative PCR used for the simultaneous detection of the M. tuberculosis complex and its resistance profile to RIF. It amplifies the rifampicin resistance–determining region of the rpoB gene in clinical specimens [

13,

46]. Once the sample is loaded into the cartridge, all testing steps—from amplification to PCR-based detection—are performed automatically within the enclosed cartridge system, thereby minimizing the risk of contamination [

47].

An improved version, the Xpert

® MTB/RIF Ultra, is also available and offers greater sensitivity and improved performance for TB detection in patients with HIV infection [

48,

49]. It is used both to detect

M. tuberculosis DNA and to assess patient infectiousness based on its semi-quantitative output [

15,

50]. As with previous generations, the Ultra detects RIF resistance by employing four probes targeting the rpoB gene. Compared with earlier versions, Ultra test cartridges contain a larger DNA amplification chamber and incorporate two multi-copy amplification targets for TB (IS6110 and IS1081) [

46], resulting in a lower limit of detection of 16 CFU/mL. These modifications increased the overall sensitivity of the Ultra from 85% to 88% [

7,

42,

51], and this assay is particularly recommended for paucibacillary forms of TB, such as TB of the central nervous system [

23,

52].

The Xpert MTB/XDR assay was designed to simultaneously detect mutations associated with resistance to multiple first and second-line anti-tuberculosis drugs, particularly in cases of extensive drug resistance [

42,

53]. This test was redesigned to improve mutation coverage for isoniazid, differentiate between low and high-level resistance to isoniazid and fluoroquinolones, identify resistance to ethionamide, and distinguish cross-resistance from individual resistance to second-line injectable agents. The analysis time was reduced to 90 minutes, and the assay’s sensitivity was also enhanced [

54].

Other real-time PCR assays include Truenat MTB, MTB Plus, and MTB-RIF Dx, developed by Molbio (India). MTB and MTB Plus are used as initial diagnostic tests for TB detection, whereas MTB-RIF Dx is employed for the detection of rifampicin resistance. The analysis is performed on automated, battery-powered devices that extract, amplify, and identify specific gene targets, enabling the rapid diagnosis of TB infections. These devices are simple to operate and can be used in peripheral laboratories with minimal infrastructure, providing results in under one hour [

7].

6.2. Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP)

It is based on DNA amplification at a single, constant temperature (isothermal), eliminating the need for a thermocycler. In this assay, multiple DNA strands can be accurately amplified repeatedly within approximately one hour [

20,

55]. In the LAMP technique, primers bind to the target region of the DNA sequence and drive the amplification process. Another essential component of this method is the DNA polymerase enzyme, which unwinds the DNA strand under isothermal conditions, enabling amplification [

43,

56]. The current application of LAMP for tuberculosis relies on the amplification of the gyrB and IS6110 target genes of the

Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex [

57].

The results can be visualized by different methods, such as a visible color change to the naked eye, fluorescence under ultraviolet light, or turbidity formation, depending on the dye or system used [

20]. Because it is a simple and cost-effective method that does not require sophisticated equipment, it can be widely applied, especially in smaller laboratories with limited resources [

20,

42,

58]. Conversely, the major disadvantage of LAMP is that the use of multiple primers can lead to nonspecific amplifications, resulting in false-positive results [

59]. In the study by Deng et al. (2021), the sensitivity and specificity of LAMP for detecting

M. tuberculosis in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid were 73% and 99%, respectively [

20].

A commercial assay based on the LAMP technique is the Loopamp™ (TB-LAMP) kit, developed by Eiken Chemical Company. This assay is manual and takes less than one hour to perform, and its results can be read with the naked eye under UV light. It is a rapid diagnostic test that does not require sophisticated infrastructure and may eventually be considered an alternative to smear microscopy [

7].

6.3. Line Probe Hybridization (LPA)

The LPA is based on reverse-hybridization DNA strip technology and detects DNA from the

M. tuberculosis complex, allowing the determination of the bacterial strain within the complex and the antimicrobial resistance profile [

9]. This occurs through the binding of amplified DNA products from these bacteria to probes that target specific regions of the

M. tuberculosis genome, common mutations associated with drug resistance, or the corresponding wild-type DNA sequence [

60]. These assays are more complex compared with the Xpert test, for example, yet they are capable of detecting resistance to several first and second-line antimicrobials by identifying genetic mutations in common variants [

9,

42]. Results can be obtained within 5 hours [

7].

This technique involves three steps: DNA extraction from clinical samples or cultured isolates, multiplex PCR amplification, and reverse hybridization. Finally, it is possible to observe the binding of the amplicon to mutation probes and wild-type probes, or the absence of such binding [

60]. Some steps can be automated, making the assay faster and reducing the risk of contamination [

7].

First-line LPAs are designed to detect tuberculosis and resistance to rifampicin and isoniazid in respiratory samples. One assay that is widely used today is the GenoType

® MTBDRplus, which has two versions [

61,

62]. These assays include rpoB probes to detect rifampicin resistance, katG probes to detect mutations associated with high-level isoniazid resistance, and inhA promoter probes to detect mutations generally associated with low-level isoniazid resistance [

7].

The GenoType MTBDRsl is an assay designed to detect mutations associated with fluoroquinolones and second-line injectable drugs. The first version detects mutations in the quinolone resistance–determining region of gyrA and rrs. The second version additionally detects mutations in the gyrB region and in the eis promoter. Both the first and second-line assays rely on the same principle: the bands observed correspond to either a wild-type or a resistance probe and can be used to determine the drug susceptibility profile of the analyzed sample [

7].

The study by Kanade et al. (2023) compared the performance of the Xpert

® MTB/RIF assay and the LPA in detecting

M. tuberculosis and antimicrobial resistance. Both tests were evaluated against the mycobacterial growth indicator tube (MGIT) 960 liquid culture system and drug susceptibility testing. The Xpert

® MTB/RIF assay demonstrated a sensitivity of 92.1%, while the LPA showed a sensitivity of 90% [

9].

6.4. Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS)

This method detects resistance to a larger number of antimicrobials compared with other tests, including those used in more modern treatment regimens. By amplifying selected genes, it can identify specific resistance-associated mutations with greater accuracy [

41,

48].

Metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) directly extracts fragments of DNA or RNA from clinical samples without isolating specific pathogens and performs sequencing independently. These sequences are then compared with databases encompassing known pathogenic microorganisms, thereby enabling the detection of

M. tuberculosis. In this way, mNGS also demonstrates potential for identifying coinfections and/or determining antimicrobial resistance [

48,

63,

64].

With technological advancements, the turnaround time has been drastically reduced, allowing results to be obtained within 24 hours [

65]. In extrapulmonary tuberculosis, the pathogen may invade other organs such as the brain, bones, and joints; therefore, corresponding samples can be used for diagnosis. Studies employing mNGS for the diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis have demonstrated excellent performance, with a detection rate of 95.65% using cerebrospinal fluid samples [

48,

66].

Although mNGS demonstrates high sensitivity and specificity, it does not offer cost–benefit advantages when compared with the average cost of Xpert. Sequencing results depend on the concentration of target sequences in the sample; therefore, both the cost and the analysis time increase with sequencing depth [

48,

67,

68]. The use of this assay has been limited in resource-constrained settings due to the high investment costs and the need for specialized technical expertise and bioinformatics support for its implementation [

41,

69,

70].

Targeted next-generation sequencing (tNGS) amplifies and sequences a selected set of genes or genomic regions that are associated with a specific pathogen or phenotype, such as drug resistance, making it useful in cases with low pathogen load [

48,

71]. Sequencing results can be obtained within a few hours, while the overall turnaround time from primary sample to final report ranges from 1 to 10 days. In addition to sputum, other sample types—such as stool and cerebrospinal fluid—can also be used [

41].

The customization of tNGS assays allows them to be applied in diverse contexts. Assays can be selected based on available sequencing capabilities, adapted to the required throughput, and target genes can be updated according to new evidence or context-specific differences, with minimal changes needed to existing infrastructure and testing procedures [

41]. The tNGS method requires custom primers for specific pathogens, which facilitates the creation of tailored genetic panels [

72]. tNGS can serve as a rapid and complementary diagnostic tool in the context of drug-resistant tuberculosis treatment regimens. Portable NGS devices with reduced costs are currently being developed, which may increase the accessibility of this technology [

41,

73].

Some tests that detect and identify mycobacterial species and antibiotic resistance based on targeted NGS include the Deeplex

® Myc-TB assay, developed by Genoscreen (France); the AmPORE-TB

® assay, developed by Oxford Nanopore Diagnostics (United Kingdom); and the TBseq

® assay, developed by Hangzhou ShengTing Medical Technology Co. (China) [

7].

7. Practical Implications for the Clinical Laboratory

Given the current epidemiological landscape of tuberculosis, characterized by high morbidity and mortality rates, the implementation of appropriate, rapid, and sensitive diagnostic methods is essential for disease control. The selection of the most suitable diagnostic tests should be based on multiple factors, including the complexity of the healthcare service, laboratory infrastructure, workload, available financial resources, the epidemiological profile of the population served, and the clinical or epidemiological purpose of the diagnosis, which directly affects the required turnaround time to meet the needs of the target population.

In high-complexity hospitals with infectious disease units, emergency departments, intensive care units, and inpatient care for patients with severe forms of TB, the adoption of automated molecular methods, such as Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra or Xpert MTB/XDR, is recommended. These assays enable rapid detection of TB and resistance to essential antimicrobials with a high degree of sensitivity. They have a reduced turnaround time, with results available in less than two hours, making them ideal for immediate clinical decision-making, such as in emergency care settings. Additionally, these facilities can also perform LPA assays, primarily as confirmatory tools following initial molecular detection of resistance. Although these tests require greater technical expertise, they provide detailed genotypic information that is valuable for guiding therapeutic decisions.

In medium-complexity hospitals or regional laboratories with moderate infrastructure, moderately complex NAATs, such as Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra or Xpert MTB/XDR, can also be utilized. These assays provide higher analytical throughput and are suitable for laboratories managing a moderate volume of samples. Additionally, they can be combined with bacterial culture and susceptibility testing to monitor resistance to second-line antimicrobials and to complement the diagnosis in more complex cases.

In low-complexity hospitals, particularly those located in remote areas or facing shortages of human and financial resources, methods such as smear microscopy can still be employed as a screening tool, although their low sensitivity limits their effectiveness. These settings would also benefit from the implementation of LAMP, due to its simplicity and superior performance, providing results within one hour with minimal equipment. Other alternatives include simplified versions of molecular assays currently under development, designed to overcome barriers related to cost and infrastructure.

In emergency departments, urgent care units, or infectious disease wards that admit patients previously diagnosed with HIV, lateral flow assays such as Alere Determine TB-LAM Ag and FujiLAM can be useful alternatives for rapid TB diagnosis. Additionally, individuals who have been in contact with infected people or who are at high risk of infection, such as immunocompromised patients, may undergo latent tuberculosis testing using assays for example, the QuantiFERON-TB Gold-Plus IGRA.

For laboratories processing a high volume of samples or specimens originating from remote areas, standardization of workflows and automation of laboratory processes are essential strategies. In these contexts, automated NAATs with batch processing capability, combined with liquid culture systems (BACTEC MGIT 960), ensure traceability, quality control, and high sensitivity. Additionally, tNGS-based assays can be employed for resistance monitoring and molecular surveillance, particularly in reference centers, due to their high accuracy and ability to detect multiple genetic markers in a single assay.

For epidemiological studies and laboratory surveillance, such as those conducted in research institutes or national reference centers, it is essential to implement methods that enable not only diagnosis, but also molecular typing and identification of mutations associated with drug resistance. In this context, techniques such as LPA and NGS stand out for providing robust data to guide public health policies and strategies for controlling drug-resistant TB. However, due to their high costs and infrastructure requirements, these tests should be centralized in national reference laboratories with efficient sample workflows and adequate bioinformatics support.

It is also essential for each facility to establish an integrated diagnostic workflow, encompassing proper sample collection and transportation through to the delivery of results. This workflow should consider the use of rapid screening tests, followed by confirmation with culture and susceptibility testing, and, in selected cases, the application of advanced molecular tools. This hybrid model allows for resource optimization, increased diagnostic coverage, and reduced turnaround time, the interval between clinical suspicion and treatment initiation.

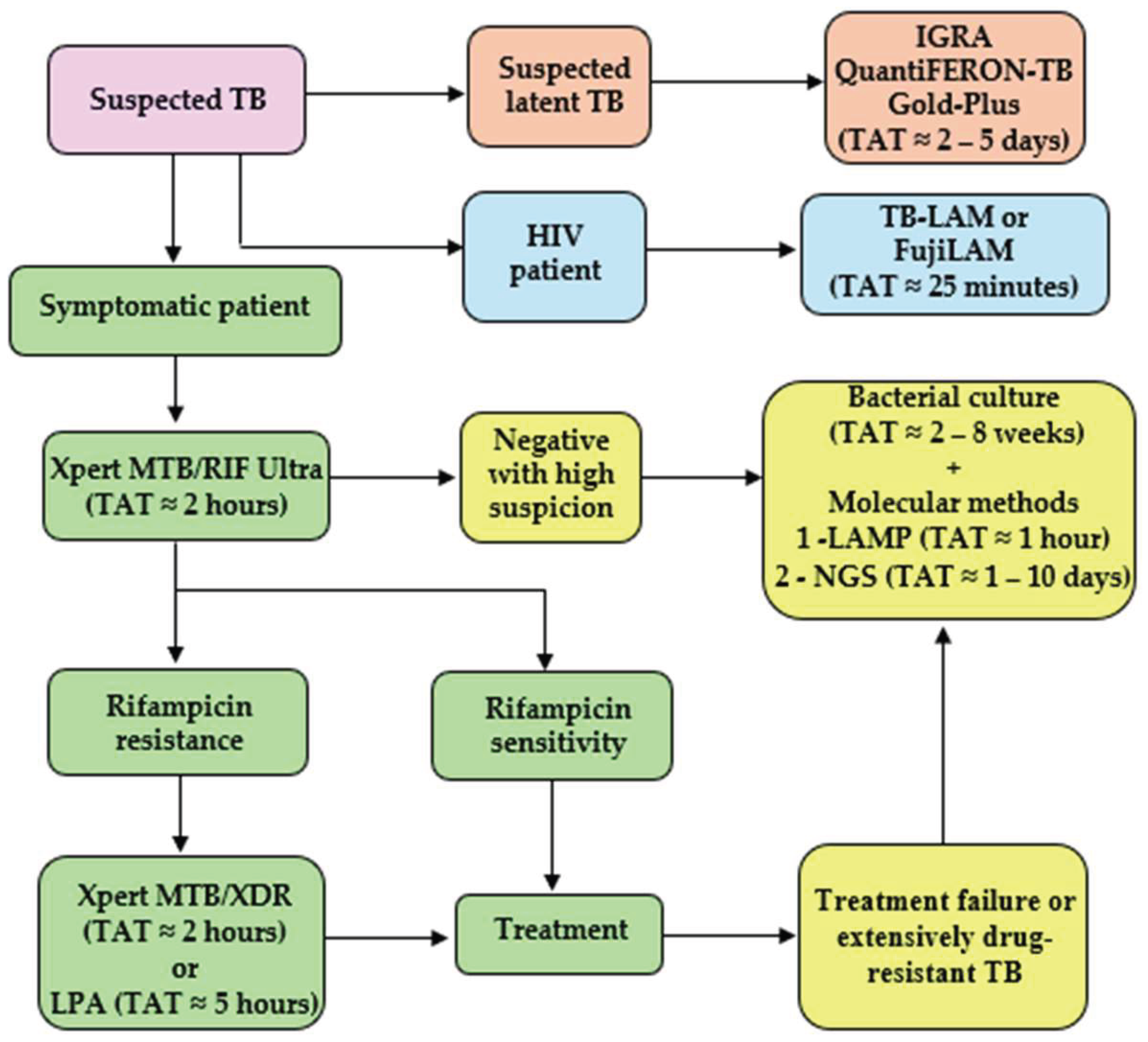

Figure 1 illustrates a potential TB testing workflow to be followed based on patient screening and clinical presentation. Methods such as smear microscopy can still be employed as an initial screening tool in settings where molecular testing is not immediately available, although they are not included in the ideal diagnostic workflow shown in

Figure 1 due to their limited sensitivity.

Finally, it is essential that healthcare managers and professionals are trained to understand the different available methods, their advantages, and limitations, in order to implement appropriate strategies. Therefore, there is no single test that is ideal for all settings. The selection of the most suitable diagnostic method should be carried out strategically and contextually, ensuring accessibility, accuracy, rapidity, and a positive impact on clinical management and TB control. The establishment of integrated laboratory networks, with well-defined workflows and continuous technical support, is crucial for the effectiveness of tuberculosis control programs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.P.R. and F.P.; methodology, E.P.R.; formal analysis, E.P.R.; investigation, E.P.R.; data curation, E.P.R.; writing—original draft preparation, E.P.R.; writing—review and editing, F.P.; supervision, F.P.; funding acquisition, F.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BCG |

Bacillus Calmette -Guérin |

| DST |

Drug susceptibility testing |

| ELISA |

Enzyme-linked immunoassay |

| HIV |

Human immunodeficiency virus |

| IGRA |

Interferon-gamma release assay |

| IFN- γ |

Interferon-gamma |

| LAM |

Lipoarabinomannan |

| LAMP |

Loop-mediated isothermal amplification |

| LF-LAM |

Lateral flow immunoassay |

| LPA |

Line probe assay |

| MDR |

Multidrug resistance |

| MGIT |

Mycobacteria Growth Indicator Tube |

| mNGS |

Metagenomic next-generation sequencing |

| M. tuberculosis |

Mycobacterium tuberculosis |

| NAAT |

Automated nucleic acid amplification tests |

| NGS |

Next-generation sequencing |

| PCR |

Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| PPD |

Purified protein derivative |

| RIF |

Rifampicin |

| TB |

Tuberculosis |

| tNGS |

Targeted next-generation sequencing |

| UV |

Ultraviolet |

| XDR |

Extensively drug-resistant |

| WHO |

World health organization |

References

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2024. 1st ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024. Accessed on: 21 September 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-programme-on-tuberculosis-and-lung-health/tb-reports/global-tuberculosis-report-2024.

- Tortora GJ. et al. Microbiologia. 14th ed. Porto Alegre: Artmed; 2025.

- Ortiz-Brizuela E., Menzies D., Behr M.A. Testing and Treating Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection. Med Clin North Am 2022;106:929–47. [CrossRef]

- Houben R.M.G.J., Dodd P.J. The Global Burden of Latent Tuberculosis Infection: A Re-estimation Using Mathematical Modelling. PLOS Med 2016;13:e1002152. [CrossRef]

- Emery J.C., Richards A.S., Dale K.D., et al. Self-clearance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection: implications for lifetime risk and population at-risk of tuberculosis disease. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 2021;288:20201635. [CrossRef]

- Nações Unidas Brasil. Objetivo de Desenvolvimento Sustentável 3: Saúde e Bem-Estar [Internet]. Brasília: ONU Brasil; Accessed on: 18 September 2025. Available online: https://brasil.un.org/pt-br/sdgs/3.

- World Health Organization. WHO consolidated guidelines on tuberculosis: rapid diagnostics for tuberculosis detection; Module 3: Diagnosis. Third edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024. Accessed on: 21 September 2025. Available onlne: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240089488.

- Pati H.P., Singh G. Turnaround Time (TAT): Difference in Concept for Laboratory and Clinician. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus 2014;30:81–4. [CrossRef]

- Kanade S., Mohammed Z., Kulkarni A., et al. Comparison of Xpert MTB/RIF Assay, Line Probe Assay, and Culture in Diagnosis of Pulmonary Tuberculosis on Bronchoscopic Specimen. Int J Mycobacteriology 2023;12:151. [CrossRef]

- Santos F.D.J., Tenorio J.E.D.O.S., Portugal L.G. A importância da realização de cultura de escarro para o diagnóstico de tuberculose pulmonar em pacientes paucibacilares. Rev Bras Análises Clínicas 2024;56:90–5. [CrossRef]

- Baquero-Artigao F., del Rosal T., Falcón-Neyra L., et al. Update on the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis. An Pediatría Engl Ed 2023;98:460–9. [CrossRef]

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de Doenças de Condições Crônicas e Infecções Sexualmente Transmissíveis. Manual de Recomendações para o Diagnóstico Laboratorial de Tuberculose e Micobactérias não Tuberculosas de Interesse em Saúde Pública no Brasil. – Brasília: Ministério da Saúde, 2022. Accessed on: 21 September 2025. Available online: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/centrais-de-conteudo/publicacoes/svsa/tuberculose/manual-de-recomendacoes-e-para-diagnostico-laboratorial-de-tuberculose-e-micobacterias-nao-tuberculosas-de-interesse-em-saude-publica-no-brasil.pdf/view.

- Raj A., Baliga S., Shenoy M.S., et al. Validity of a CB-NAAT assay in diagnosing tuberculosis in comparison to culture: A study from an urban area of South India. J Clin Tuberc Mycobact Dis 2020;21:100198. [CrossRef]

- McNerney R., Clark T.G., Campino S., et al. Removing the bottleneck in whole genome sequencing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis for rapid drug resistance analysis: a call to action. Int J Infect Dis 2017;56:130–5. [CrossRef]

- Boldi M-O., Denis-Lessard J., Neziri R., et al. Performance of microbiological tests for tuberculosis diagnostic according to the type of respiratory specimen: A 10-year retrospective study. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2023;13:1131241. [CrossRef]

- Siddiqi S.H., Ruesch-Gerdes S. MGIT procedure manual for BACTEC™ MGIT 960™ TB System (Also applicable for Manual MGIT): Mycobacteria Growth Indicator Tube (MGIT) Culture and Drug Susceptibility Demonstration Projects, 2006. Accessed on: 21 September 2025. Available online: https://www.finddx.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/20061101_rep_mgit_manual_FV_EN.pdf.

- Arora D., Dhanashree B. Utility of smear microscopy and GeneXpert for the detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in clinical samples. Germs 2020;10:81–7. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Laboratory services in tuberculosis control. Part I: Organization and management. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1998. Accessed on: 21 September 2025. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/65942/WHO_TB_98.258_(part1).pdf.

- Singhal R., Myneedu V.P. Microscopy as a diagnostic tool in pulmonary tuberculosis. Int J Mycobacteriology 2015;4:1–6. [CrossRef]

- Deng Y., Duan Y., Gao S., et al. Comparison of LAMP, GeneXpert, Mycobacterial Culture, Smear Microscopy, TSPOT.TB, TBAg/PHA Ratio for Diagnosis of Pulmonary Tuberculosis. Curr Med Sci 2021;41:1023–8. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Fluorescent light-emitting diode (LED) microscopy for diagnosis of tuberculosis: policy statement. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2011. Accessed on: 21 September 2025. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/44602.

- Palanivel J., Sounderrajan V., Thangam T., et al. Latent Tuberculosis: Challenges in Diagnosis and Treatment, Perspectives, and the Crucial Role of Biomarkers. Curr Microbiol 2023;80:1–13. [CrossRef]

- Janssen S., Murphy M., Upton C., et al. Tuberculosis: An Update for the Clinician. Respirol Carlton Vic 2025;30:196–205. [CrossRef]

- Verma A., Kaur M., Singh L.V., et al. Reactivation of latent tuberculosis through modulation of resuscitation promoting factors by diabetes. Sci Rep 2021;11:19700. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Rapid communication: TB antigen-based skin tests for the diagnosis of TB infection. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2022. Accessed on: 21 September 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-UCN-TB-2022.1.

- Krutikov M., Faust L., Nikolayevskyy V., et al. The diagnostic performance of novel skin-based in-vivo tests for tuberculosis infection compared with purified protein derivative tuberculin skin tests and blood-based in vitro interferon-γ release assays: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2022;22:250–64. [CrossRef]

- Yang H., Kruh-Garcia N.A., Dobos K.M. Purified Protein Derivatives of Tuberculin - Past, Present, and Future. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 2012;66:273–80. [CrossRef]

- Hamada Y., Cirillo D.M., Matteelli A., et al. Tests for tuberculosis infection: landscape analysis. Eur Respir J 2021;58. [CrossRef]

- Starshinova A., Dovgalyk I., Malkova A., et al. Recombinant Tuberculosis Allergen (Diaskintest®) in Tuberculosis Diagnostic in Russia (Meta-Analysis). Int J Mycobacteriology 2020;9:335. [CrossRef]

- Meier N.R., Volken T., Geiger M., et al. Risk Factors for Indeterminate Interferon-Gamma Release Assay for the Diagnosis of Tuberculosis in Children—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Pediatr 2019;7:208. [CrossRef]

- Pai M., Zwerling A., Menzies D. Systematic Review: T-Cell–based Assays for the Diagnosis of Latent Tuberculosis Infection: An Update. Ann Intern Med 2008;149:177–84. [CrossRef]

- Goletti D., Delogu G., Matteelli A., et al. The role of IGRA in the diagnosis of tuberculosis infection, differentiating from active tuberculosis, and decision making for initiating treatment or preventive therapy of tuberculosis infection. Int J Infect Dis IJID Off Publ Int Soc Infect Dis 2022;124 Suppl 1:S12–9. [CrossRef]

- van Ingen J, de Zwaan R, Dekhuijzen R, et al. Region of Difference 1 in Nontuberculous Mycobacterium Species Adds a Phylogenetic and Taxonomical Character. J Bacteriol 2009;191:5865–7. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Lateral flow urine lipoarabinomannan assay (LF-LAM) for the diagnosis of active tuberculosis in people living with HIV: policy update 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. Accessed on: 21 September 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550604.

- Brennan P.J. Structure, function, and biogenesis of the cell wall of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 2003;83(1-3):91-7. [CrossRef]

- Flores J., Cancino J.C., Chavez-Galan L. Lipoarabinomannan as a Point-of-Care Assay for Diagnosis of Tuberculosis: How Far Are We to Use It? Front Microbiol 2021;12:638047. [CrossRef]

- Broger T., Nicol M.P., Sigal G.B., et al. Diagnostic accuracy of 3 urine lipoarabinomannan tuberculosis assays in HIV-negative outpatients. J Clin Invest 2020;130:5756–64. [CrossRef]

- Bulterys M.A., Wagner B., Redard-Jacot M., et al. Point-Of-Care Urine LAM Tests for Tuberculosis Diagnosis: A Status Update. J Clin Med 2019;9:111. [CrossRef]

- Broger T., Sossen B., du Toit E., et al. Novel lipoarabinomannan point-of-care tuberculosis test for people with HIV: a diagnostic accuracy study. Lancet Infect Dis 2019;19:852–61. [CrossRef]

- Das S., Mangold K.A., Shah N.S., et al. Performance and Utilization of a Laboratory-Developed Nucleic Acid Amplification Test (NAAT) for the Diagnosis of Pulmonary and Extrapulmonary Tuberculosis in a Low-Prevalence Area. Am J Clin Pathol 2020;154:115–23. [CrossRef]

- Schwab T.C., Perrig L., Göller P.C., et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing to diagnose drug-resistant tuberculosis: systematic review and test accuracy meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2024;24:1162–76. [CrossRef]

- MacLean E., Kohli M., Weber S.F., et al. Advances in Molecular Diagnosis of Tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol 2020;58:e01582-19. [CrossRef]

- Alsharksi N.A., Sirekbasan S., Gürkök-Tan T., et al. From Tradition to Innovation: Diverse Molecular Techniques in the Fight Against Infectious Diseases. Diagnostics 2024;14:2876. [CrossRef]

- Espy M.J., Uhl J.R., Sloan L.M., et al. Real-Time PCR in Clinical Microbiology: Applications for Routine Laboratory Testing. Clin Microbiol Rev 2006;19:165–256. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Automated real-time nucleic acid amplification technology for rapid and simultaneous detection of tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance: Xpert MTB/RIF system: policy statement. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. Accessed on: 21 september 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241501545.

- Osei Sekyere J., Maphalala N., Malinga L.A., et al. A Comparative Evaluation of the New Genexpert MTB/RIF Ultra and other Rapid Diagnostic Assays for Detecting Tuberculosis in Pulmonary and Extra Pulmonary Specimens. Sci Rep 2019;9:16587. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Rapid implementation of the Xpert MTB/RIF diagnostic test: technical and operational “How-to”; practical considerations. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. Accessed on: 21 September 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241501569.

- Li Y., Jiao M., Liu Y., et al. Application of Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing in Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection. Front Med 2022;9:802719. [CrossRef]

- Opota O., Mazza-Stalder J., Greub G., et al. The rapid molecular test Xpert MTB/RIF ultra: towards improved tuberculosis diagnosis and rifampicin resistance detection. Clin Microbiol Infect 2019;25:1370–6. [CrossRef]

- van Zyl-Smit R.N., Binder A., Meldau R., et al. Comparison of Quantitative Techniques including Xpert MTB/RIF to Evaluate Mycobacterial Burden. PLoS ONE 2011;6:e28815. [CrossRef]

- Horne D.J., Kohli M., Zifodya J.S., et al. Xpert MTB/RIF and Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra for pulmonary tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019;2019:CD009593. [CrossRef]

- Chakravorty S., Simmons A.M., Rowneki M., et al. The New Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra: Improving Detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Resistance to Rifampin in an Assay Suitable for Point-of-Care Testing. mBio 2017;8:e00812-17. [CrossRef]

- Xie Y.L., Chakravorty S., Armstrong D.T., et al. Evaluation of a Rapid Molecular Drug-Susceptibility Test for Tuberculosis. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1043–54. [CrossRef]

- Cao Y. Xpert MTB/XDR: a 10-Color Reflex Assay Suitable for Point-of-Care Settings To Detect Isoniazid, Fluoroquinolone, and Second-Line-Injectable-Drug Resistance Directly from Mycobacterium tuberculosis-Positive Sputum. J Clin Microbiol 2021;59(3): e02314-2. [CrossRef]

- Rudeeaneksin J., Bunchoo S., Srisungngam S., et al. Rapid Identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in BACTEC MGIT960 Cultures by In-House Loop-Medicated Isothermal Amplification. Jpn J Infect Dis 2012;65:306–11. [CrossRef]

- Park J-W. Principles and Applications of Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification to Point-of-Care Tests. Biosensors 2022;12:857. [CrossRef]

- Ou X., Li Q., Xia H., et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of the PURE-LAMP Test for Pulmonary Tuberculosis at the County-Level Laboratory in China. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e94544. [CrossRef]

- Neonakis I.K., Spandidos D.A., Petinaki E. Use of loop-mediated isothermal amplification of DNA for the rapid detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in clinical specimens. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2011;30:937–42. [CrossRef]

- Kim S-H., Lee S-Y., Kim U., et al. Diverse methods of reducing and confirming false-positive results of loop-mediated isothermal amplification assays: A review. Anal Chim Acta 2023;1280:341693. [CrossRef]

- Nathavitharana R.R., Hillemann D., Schumacher S.G., et al. Multicenter Noninferiority Evaluation of Hain GenoType MTBDRplus Version 2 and Nipro NTM+MDRTB Line Probe Assays for Detection of Rifampin and Isoniazid Resistance. J Clin Microbiol 2016;54:1624–30. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Line probe assays for detection of drug-resistant tuberculosis: interpretation and reporting manual for laboratory staff and clinicians. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022. Accessed on: 21 September 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240046665.

- Schünemann H.J., Mustafa R.A., Brozek J., et al. GRADE guidelines: 21 part 1. Study design, risk of bias, and indirectness in rating the certainty across a body of evidence for test accuracy. J Clin Epidemiol 2020;122:129–41. [CrossRef]

- Gu W., Miller S., Chiu C.Y. Clinical Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing for Pathogen Detection. Annu Rev Pathol 2019;14:319–38. [CrossRef]

- Jin W., Pan J., Miao Q., et al. Diagnostic accuracy of metagenomic next-generation sequencing for active tuberculosis in clinical practice at a tertiary general hospital. Ann Transl Med 2020;8:1065. [CrossRef]

- Gu W., Deng X., Lee M., et al. Rapid Pathogen Detection by Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing of Infected Body Fluids. Nat Med 2021;27:115–24. [CrossRef]

- Wang S., Chen Y., Wang D., et al. The Feasibility of Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing to Identify Pathogens Causing Tuberculous Meningitis in Cerebrospinal Fluid. Front Microbiol 2019;10. [CrossRef]

- Figueredo L.J.A., Miranda S.S., Santos L.B., et al. Cost analysis of smear microscopy and the Xpert assay for tuberculosis diagnosis: average turnaround time. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2020;53:e20200314. [CrossRef]

- Zhang C., Hu T., Xiu L., et al. Use of Ultra-Deep Sequencing in a Patient with Tuberculous Coxitis Shows Its Limitations in Extrapulmonary Tuberculosis Diagnostics: A Case Report. Infect Drug Resist 2019;12:3739–43. [CrossRef]

- Cabibbe A.M., Walker T.M., Niemann S., et al. Whole genome sequencing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Eur Respir J 2018;52. [CrossRef]

- de Araujo L., Cabibbe A.M., Mhuulu L., et al. Implementation of targeted next-generation sequencing for the diagnosis of drug-resistant tuberculosis in low-resource settings: a programmatic model, challenges, and initial outcomes. Front Public Health 2023;11:1204064. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The use of next-generation sequencing technologies for the detection of mutations associated with drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex: technical guide. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. Accessed on: 21 September 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-CDS-TB-2018.19.

- Wylie T.N., Wylie K.M., Herter B.N., et al. Enhanced virome sequencing using targeted sequence capture. Genome Res 2015;25:1910–20. [CrossRef]

- Satam H., Joshi K., Mangrolia U., et al. Next-Generation Sequencing Technology: Current Trends and Advancements. Biology 2023;12:997. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).