1. Introduction

The cultural and creative industries have become a dynamic driver of the global economy, contributing around 3% to global GDP and a significant share of exports and employment. In Indonesia, the creative economy has emerged as a strategic growth sector, generating more than IDR 1,500 trillion in value added to GDP and employing approximately 26 million people in the period up to late 2024 (ANTARA News, 2025b). At the same time, micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) constitute the backbone of Indonesia’s economic structure: they account for roughly 99% of all business units, contribute about 60–62% of GDP, and absorb around 97% of the workforce (ANTARA News, 2025a). A large proportion of creative businesses operate as MSMEs, positioning creative MSMEs at the intersection of digital innovation, inclusive growth, and the broader sustainable development agenda.

Rapid digitalisation and the proliferation of online platforms are reshaping how creative MSMEs produce, distribute, and monetise creative content. Digital marketplaces, streaming services, and social media enable creators to reach global audiences but also introduce new vulnerabilities (Darmawan, 2023). Fragmented value chains, complex licensing arrangements, and opaque revenue-sharing mechanisms often make it difficult for creators to verify sales, track royalties, and protect their intellectual property (Susilatun et al., 2023). In this context, stakeholders increasingly demand transparent, reliable, and tamper-resistant information about financial flows and rights ownership, not only for internal decision-making but also for external accountability, governance, and alignment with environmental, social, and governance (ESG) expectations (Muafi & Liestyana, 2025; Paliwal et al., 2020). For creative MSMEs, this translates into pressure to modernise their accounting systems and governance practices so that they can demonstrate fair value distribution, responsible business conduct, and contribution to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

These dynamics are unfolding amid heightened global uncertainty, characterised by fragile post-pandemic recoveries, geopolitical tensions, inflationary shocks, and increasingly volatile digital markets. For creative MSMEs in emerging economies, this creates a “double exposure”: they must cope with unstable demand and regulatory environments while simultaneously adapting to fast-moving digital disruption. In such conditions, mechanisms that can strengthen transparency, trust, and resilience in accounting and financial practices become particularly salient.

Blockchain technology has been widely promoted as a potential solution to these challenges. As a distributed, append-only ledger, blockchain records transactions in an immutable and time-stamped manner, enabling shared visibility and verification across network participants. Recent studies argue that blockchain can reduce information asymmetries, lower transaction costs, and enhance trust in inter-organisational relationships, particularly for small businesses and MSMEs (Ajike et al., 2025; Kaur et al., 2024). Evidence from various sectors suggests that blockchain-enabled applications—such as smart contracts, tokenisation, and non-fungible tokens—can support real-time tracking of value transfers, automated execution of contractual terms, and stronger proof of ownership over digital assets, including creative works and brands. These characteristics are highly relevant for accounting and finance, where transparent records, auditable trails, and verifiable rights underpin credible reporting and effective governance (Hou & Xu, 2024; Mutamimah et al., 2023).

However, the adoption of blockchain by MSMEs remains limited and uneven. Empirical research consistently highlights substantial barriers related to high implementation and maintenance costs, technical complexity, cybersecurity concerns, and difficulties integrating blockchain with existing information systems and business processes (Kshetri, 2025; R. Kumar et al., 2023). For small firms, these challenges are compounded by limited financial resources, shortages of skilled personnel, and uncertainty about legal and regulatory frameworks governing blockchain-based transactions and digital assets. Studies on cloud accounting and digital platforms for MSMEs similarly show that organisational readiness, digital literacy, perceived security, and government support are critical in shaping technology adoption decisions (Alshenaifi & El Sayad, 2024; Musyaffi et al., 2025). While some case studies report that blockchain can deliver tangible benefits in supply chain transparency, trade finance, and sustainability reporting, others question its scalability and environmental footprint, suggesting that the technology’s transformative potential is highly context-dependent (Zunairoh & Wijaya, 2024).

Within this broader literature, blockchain in the context of MSMEs has been studied primarily in relation to supply chain management, logistics, and financing, often with a focus on cost reduction, traceability of physical goods, or access to credit. (Sahoo & Thakur, 2023; Xiao et al., 2025) Much less is known about how creative MSMEs—whose core assets are intangible, digitally reproduced, and easily misappropriated—engage with blockchain for accounting and governance purposes (Ali & Maheshwari, 2025; Musyaffi et al., 2025). The specific ways in which creative MSMEs might use blockchain to record and verify digital sales, allocate revenue among collaborators, recognise and amortise intellectual property, or generate evidence for tax and regulatory compliance have received limited attention. Furthermore, existing studies rarely examine how such practices relate to broader ESG-oriented accounting and SDG agendas in emerging economies, where informality, weak enforcement, and constrained institutional capacity are common (Idrus & Rastina, 2026; Leo et al., 2025).

The Indonesian context provides a particularly salient setting for examining these issues. On the one hand, the government has explicitly prioritised digital transformation and the strengthening of creative industries as part of its development strategy, and recent regulations have begun to recognise blockchain and related technologies as components of national digital infrastructure (Herdiyeni et al., 2025; Zulfikar et al., 2022). Government Regulation No. 28 of 2025, for example, frames blockchain as part of the broader digital ecosystem and outlines general principles for its use in economic activities, including requirements related to security, accountability, and consumer protection. On the other hand, official and independent assessments show that many MSMEs still struggle with basic digitalisation, including the adoption of standardised accounting systems, digital payment tools, and data-driven decision-making (Iriyadi et al., 2023; Perdana et al., 2024). For creative MSMEs, these generic digital gaps interact with sector-specific constraints such as informal business practices and pervasive risks of piracy and unfair revenue distribution. As a result, there is a paradox: blockchain is promoted as a tool for more transparent, fair, and sustainable creative economies, yet the firms that could benefit most are often least equipped to adopt and integrate it into their accounting and governance routines.

From a public sector accounting and governance perspective, more transparent and verifiable records in creative MSMEs are not only beneficial for internal decision-making but also for monitoring the effectiveness of public programmes that support the creative economy (Hou & Xu, 2024; Mutamimah et al., 2023). Governments increasingly deploy grants, tax incentives, and SDG-oriented initiatives to promote creative industries, and these interventions require reliable financial and non-financial information from beneficiary firms. Blockchain-enabled accounting practices in creative MSMEs could therefore strengthen the accountability of public spending, improve the quality of data used in policy evaluation, and enhance trust between state institutions and creative entrepreneurs.

From a theoretical perspective, understanding blockchain adoption in this setting requires attention both to individual decision-makers’ perceptions and to the characteristics of blockchain as an innovation within a specific socio-economic and institutional context (Vafaei-Zadeh et al., 2025). The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) provides a widely used framework for explaining technology adoption at the individual level, positing that perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use shape attitudes, behavioural intentions, and actual use (Davis, 1989). In the case of creative MSMEs, perceived usefulness may relate to expectations that blockchain will increase transparency, protect intellectual property, or simplify revenue sharing, while perceived ease of use concerns the effort required to understand, implement, and operate blockchain-based systems.

Complementing TAM, Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovation (DOI) theory emphasises how attributes of an innovation and features of the social system influence its diffusion (Rogers, 2003). Key attributes include relative advantage, compatibility, complexity, trialability, and observability. For blockchain in creative MSMEs, relative advantage refers to the perceived benefits over existing accounting and contracting practices; compatibility concerns the fit with current business models, informal routines, and existing digital tools; complexity captures the perceived difficulty of understanding and implementing blockchain; trialability reflects opportunities to experiment on a limited scale; and observability relates to the visibility of successful blockchain use cases within the creative ecosystem. Integrating TAM and DOI thus offers a more holistic lens: TAM foregrounds the cognitive evaluations of owners and managers, while DOI situates those evaluations within the broader innovation attributes, organisational conditions, and ecosystem dynamics.

This research investigates how blockchain can be used to support transparent and sustainable accounting practices in Indonesia’s creative MSMEs. Specifically, it addresses three interrelated questions: (1) how creative MSME owners and managers perceive the usefulness and ease of use of blockchain for transaction recording, royalty tracking, and intellectual property–related accounting; (2) what technological, organisational, and regulatory barriers they face in adopting blockchain; and (3) under what conditions blockchain is viewed as a viable tool for strengthening governance, accountability, and alignment with ESG and SDG-related expectations. Drawing on a qualitative exploratory design with in-depth interviews of practitioners from diverse creative subsectors, the study shows that blockchain is widely recognised as a promising mechanism for enhancing transparency, reliability, and auditability of financial information in the creative economy, but that adoption remains nascent due to technical complexity, cost, digital skills gaps, and regulatory ambiguity. In doing so, the study extends TAM- and DOI-based understandings of technology adoption into the domain of blockchain-enabled accounting for creative MSMEs and provides policy-relevant insights for designing supportive ecosystems and interventions in times of rapid digital disruption.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

This study employed a qualitative, exploratory case study design to investigate how blockchain can be harnessed for transparent and sustainable accounting in Indonesia’s creative MSMEs. A qualitative approach is appropriate for examining emerging, complex phenomena that require deep insight into participants’ perceptions, experiences, and contexts rather than statistical generalisation (Yin, 2018). The case study strategy provided flexibility to explore how creative practitioners interpret blockchain technology, how they relate it to their accounting and governance practices, and how they respond to the broader digitalisation and regulatory environment in which they operate.

The focus on Indonesia’s creative MSMEs reflects both their strategic role in the national creative economy and the relative novelty of blockchain adoption in this sector. Given the limited prior empirical work on blockchain-enabled accounting in creative industries in emerging markets, an exploratory design was deemed most suitable to generate rich, contextualised insights that can inform theory development and policy design.

2.2. Sampling and Participants

The study involved 18 participants, coded IF-01 to IF-18, all of whom are practitioners in Indonesia’s creative economy. Participants were selected using purposive sampling, a technique widely employed in qualitative research to ensure that information-rich cases with relevant experience and knowledge are included (Creswell & Creswell, 2017). Three inclusion criteria were applied:

- 1.

Active engagement in the creative economy – participants had to be owners, managers, or key decision-makers in creative MSMEs operating in subsectors such as graphic and fashion design, photography, film and video production, animation, music production, culinary arts, performing arts, handicrafts, architecture, visual arts, game development, and digital marketing.

- 2.

Minimum professional experience – participants needed at least five years of operational experience in their respective creative fields to ensure familiarity with both business processes and accounting practices.

- 3.

Exposure to digital transformation and/or blockchain – participants were required to have some awareness of digitalisation issues, including discussions or initiatives related to blockchain or similar technologies, so that they could meaningfully reflect on the opportunities and challenges of adoption.

This purposive strategy ensured that participants could provide informed views on both the practical and strategic implications of blockchain for their creative businesses. The sample was intentionally diverse in terms of gender, creative subsector, and length of experience to capture a broad spectrum of perspectives within Indonesia’s creative industries.

Table 1 summarises the demographic characteristics of the participants, including creative subsector, gender, years of experience, and interview duration.

2.3. Data Collection

Data were collected through semi-structured, in-depth interviews, complemented by document analysis and observational field notes. Semi-structured interviews were chosen to balance a consistent focus on the research questions with sufficient flexibility to follow emergent issues raised by participants.

An interview guide was developed based on the key constructs of the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM)—perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use—and Diffusion of Innovation (DOI) theory, particularly relative advantage, compatibility, and complexity. The guide included open-ended questions designed to elicit participants’ perceptions of:

the usefulness and ease of use of blockchain for transaction recording, royalty tracking, and intellectual property–related accounting;

barriers to blockchain adoption in the creative sector, including technical, financial, organisational, and regulatory constraints;

perceived benefits of blockchain for transparency, security, and trust;

their interpretations of government regulation (e.g., GR 28/2025) and its implications for blockchain adoption in creative MSMEs.

To enhance the content validity and clarity of the instrument, the interview guide was reviewed by two academic experts in blockchain and digitalisation of MSMEs, as well as one specialist in qualitative research methods. Minor refinements were made to wording, sequencing, and probing questions to ensure that the guide was comprehensible to creative practitioners and aligned with the theoretical constructs.

Interviews were conducted in a mix of face-to-face and online formats (via Zoom and Google Meet), depending on participant availability and geographical location. Each interview lasted approximately 50–75 minutes, allowing sufficient time for participants to elaborate on their experiences and reflections. Interviews were audio-recorded with participants’ permission and supported by contemporaneous note-taking to capture non-verbal cues and contextual details.

In addition to interviews, relevant documents—such as government regulations, industry and policy reports, and public-facing information about blockchain-related initiatives in the creative economy—were collected and analysed to provide contextual background and to triangulate participants’ accounts. Observational field notes were also compiled during interactions with participants and visits (physical or virtual) to creative workspaces and digital platforms, further enriching the empirical base of the study.

2.4. Data Analysis

All interviews were transcribed verbatim in the original language, and transcripts were checked against the recordings for accuracy. Data were then analysed using thematic analysis, following the six-step framework: (1) familiarisation with the data; (2) generating initial codes; (3) searching for themes; (4) reviewing themes; (5) defining and naming themes; and (6) producing the report.

The coding process was conducted manually. This facilitated close engagement with the data and enabled iterative refinement of codes and themes as new insights emerged. Both deductive (theory-driven) and inductive (data-driven) approaches were employed to ensure a comprehensive interpretation of findings.

Deductive coding drew on TAM and DOI constructs (perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, relative advantage, compatibility, complexity, and observability), as well as concepts related to transparency, governance, and sustainable accounting.

Inductive coding allowed unanticipated issues—such as ecosystem-level constraints, informal accounting routines, and perceptions of fairness in digital platforms—to emerge from participants’ narratives.

Codes were iteratively grouped into higher-order categories and themes that captured patterns related to blockchain adoption barriers, perceived benefits, implications for accounting and governance, and the role of regulatory frameworks. Emerging themes were repeatedly compared across cases and subsectors to identify convergences and divergences in experiences and perceptions.

2.5. Trustworthiness and Rigour

Several strategies were implemented to enhance the credibility, transferability, and dependability of the findings.

Triangulation was employed by cross-checking information from multiple data sources—interviews, documents, and field notes—to corroborate key patterns and reduce the risk of relying on single-source accounts.

Member checking was conducted with selected participants, who were invited to review and comment on interview summaries and preliminary interpretations. Their feedback was used to refine the analysis and to confirm that the findings accurately reflected their views and experiences.

Data saturation was monitored during data collection; interviews were continued until no substantively new themes emerged, suggesting that the dataset adequately captured the range of relevant perspectives.

Audit trail – a detailed record of sampling decisions, interview procedures, coding steps, theme development, and analytic memos was maintained to provide transparency about the research process and to allow external assessment of methodological consistency.

Together, these strategies enhanced the trustworthiness of the study, supporting the claim that the interpretations presented in the findings are well grounded in the empirical material and reflective of the contextual realities of blockchain adoption in the creative sector.

2.6. Ethical Considerations

Ethical principles were observed throughout the research process. Participants were informed about the research objectives, the voluntary nature of their participation, and their right to withdraw at any time without adverse consequences. Informed consent was obtained in both written and verbal form prior to each interview.

To preserve anonymity, all participants were assigned alphanumeric codes (IF-01 to IF-18), and identifying details were removed or disguised in transcripts, notes, and the final report. Audio files, transcripts, and associated documents were stored securely and accessed only by the research team. These procedures ensured that participants’ confidentiality and privacy were protected and that ethical standards for qualitative research involving human participants were upheld.

3. Results

The analysis draws on 18 creative MSMEs operating in a range of subsectors, including fashion design, handicrafts, photography, film and video production, animation and visual effects, digital illustration, music production, performing arts, game development, culinary arts, visual arts, architecture, and digital marketing. Owners or key decision-makers participated as informants (IF-01 to IF-18), with professional experience ranging from five to over fifteen years. Most businesses combined offline activities with digital platforms to reach clients and audiences, and many were already using basic digital tools such as social media, e-commerce platforms, and online payment systems.

Across all cases, participants had at least a basic awareness of blockchain, usually through cryptocurrency, NFTs, or general media narratives. However, only a few had experimented with blockchain-based tools in their business operations. This created a clear gap between what participants perceived as the potential of blockchain and its limited actual use in their day-to-day accounting and governance practices. Four major themes emerged: (1) perceived barriers to blockchain adoption; (2) perceived benefits for transparent and sustainable accounting; (3) perceptions of the regulatory environment; and (4) perceived support needs and conditions for feasible adoption.

3.1. Perceived Barriers to Blockchain Adoption

3.1.1. Technical Complexity and Infrastructure Constraints

Participants consistently described blockchain as technically complex and difficult to understand. Many associated it with advanced financial technology rather than something that could be integrated into the routines of small creative firms. Several informants explicitly framed blockchain as “too sophisticated” for MSMEs in their sector. As IF-02, a fashion designer, stated:

“Blockchain sounds promising, but it’s too complicated for me to understand. It feels like something for big companies, not for us.”

(IF-02, Fashion Design)

A similar concern was raised by IF-04, who runs a culinary business and struggled to imagine how blockchain could be embedded in everyday operations:

“I don’t know how blockchain can be implemented in a restaurant. We are still learning basic digital tools, and now there is blockchain, but there is no clear guidance on how to use it.”

(IF-04, Culinary Arts)

Beyond conceptual complexity, several participants highlighted practical issues related to infrastructure and technical capacity. For example, IF-09, a digital illustrator, emphasised the mismatch between the demands of blockchain and the limited technical resources of small creative businesses:

“We don’t have the right tools or expertise to implement blockchain. Our team is small, and we are already busy with production. We don’t feel ready to handle something this technical.”

(IF-09, Digital Illustration)

These narratives illustrate that, for many creative MSMEs, blockchain is perceived as a distant, highly specialised technology that exceeds their current digital and infrastructural capabilities (Pedreño et al., 2021; Said & Muhammadun, 2024).

3.1.2. Financial Constraints and Perceived Cost Burden

In addition to technical complexity, financial constraints emerged as a major barrier. Participants generally believed that blockchain-based systems would be expensive to develop, integrate, and maintain. The prospect of investing in a technology that they did not fully understand was seen as risky and incompatible with the tight budgets of small firms. As IF-06, who works in animation and visual effects, explained:

“Blockchain technology is too costly for small businesses like ours. We need to be careful with our spending, and it’s hard to justify investing in something we don’t fully understand.”

(IF-06, Animation & Visual Effects)

Some participants compared blockchain with more familiar tools—such as spreadsheets, simple accounting apps, or basic invoicing platforms—which, while less sophisticated, were felt to be adequate for their current needs (Hamundu et al., 2020; Sheela et al., 2023). For these firms, the added value of blockchain did not clearly outweigh the perceived financial risks and opportunity costs.

3.1.3. Limited Digital and Accounting Capabilities

Several informants acknowledged that their businesses were still in the early stages of digitalisation and formalisation. Basic bookkeeping, consistent financial reporting, and the use of accounting software were not yet standard practice. In this context, blockchain appeared to be an advanced step that presupposed a level of digital and accounting maturity that many firms had not yet achieved (Georgiou et al., 2024; Kusuma et al., 2023).

One participant described their situation as “still learning how to tidy up our books” and commented that moving directly to blockchain would mean “skipping too many levels” in their development as a business. This sentiment was echoed across different subsectors: participants expressed interest in innovative tools but stressed that they first needed to strengthen foundational practices in accounting, contract management, and digital literacy.

3.1.4. Perceived Risk, Trust, and Misconceptions

Perceptions of risk further discouraged adoption. Because many participants first encountered blockchain through volatile cryptocurrency markets and news about scams or platform failures, they tended to conflate blockchain with speculative trading and financial instability.

Some informants expressed fear of losing money or being exposed to fraud if they adopted blockchain-based systems. Others worried about making irreversible mistakes, given the perception that “once something is on the blockchain, it cannot be changed.” These concerns were often linked to partial or inaccurate understandings of how blockchain works and what types of applications would be relevant for their businesses (Kshetri, 2022).

As a result, although participants recognised that blockchain is frequently marketed as a technology that increases trust and security, their own experiences and media exposure meant that it was simultaneously perceived as risky, opaque, and difficult to control.

3.2. Perceived Benefits for Transparent and Sustainable Accounting

3.2.1. Transaction Transparency and Verifiable Records

Many informants were attracted to the idea of blockchain as a shared, tamper-resistant ledger that could provide verifiable records of transactions. They believed that such records would help reduce disputes over payments, improve clarity in project finances, and provide stronger evidence for audits or legal processes. IF-07, who runs a handicraft business, described transparency as a key appeal of blockchain:

“I think the main benefit of blockchain for us would be transparency. We want to be sure that every transaction is recorded and that the payment is going to the right person.”

(IF-07, Handicrafts)

Participants also suggested that transparent, time-stamped records could be valuable for internal accountability, particularly in projects involving multiple collaborators or third-party platforms (R. Kumar et al., 2024; Wu & Yu, 2023). They saw potential for blockchain-based records to support more structured and professional accounting practices in the long term.

3.2.2. Intellectual Property Protection and Authenticity

Participants from music, performing arts, visual arts, and design subsectors emphasised the potential of blockchain to protect intellectual property and demonstrate authenticity. They frequently mentioned problems with plagiarism, unauthorised copying, and the difficulty of proving ownership in digital environments. IF-05, a music producer, framed blockchain as a way to protect creative outputs:

“For the creative sector, especially in music, blockchain is interesting because it can help prove who owns a song or a piece of work. If it’s registered properly, it’s easier to show that it belongs to us, not someone else, without worrying about fraud or copying.”

(IF-05, Music Production)

Similarly, IF-12, a performing artist, highlighted the importance of authenticating original products:

“As an artist, I struggle with fraud and unauthorized copies of my work. If blockchain can show clearly that a product is original and who created it, it would help us and also help customers trust that the product is original.”

(IF-12, Performing Arts)

For these participants, the potential to link digital assets to verifiable ownership records and to create new models of royalty tracking and resale rights was viewed as a significant long-term advantage, even if they had not yet experimented with such systems (Alharby, 2023).

3.2.3. Secure and Efficient Payments

Participants also perceived blockchain as a way to improve the security and efficiency of payments. Delayed payments, lack of transparency in platform disbursements, and difficulties in tracking cross-border transactions were recurring concerns. IF-16, who works in digital marketing and advertising, noted:

“Blockchain can provide secure, instant payments, which eliminates a lot of the worries we have now when we are waiting for clients or platforms to pay. It could reduce our dependence on other systems.”

(IF-16, Digital Marketing & Advertising)

Some informants suggested that smart contracts could automate payments based on predefined milestones or usage metrics, thereby reducing disputes and administrative workload. While these ideas were often aspirational rather than grounded in current practice, they indicate that creative MSMEs see clear links between blockchain and more reliable, efficient financial flows (Mishra et al., 2025; Satvik et al., 2025).

3.3. Perceptions of Regulation and Institutional Support

Participants were generally aware that the Indonesian government had begun to regulate and formally recognise blockchain, but their understanding of specific policies—such as Government Regulation No. 28 of 2025—varied widely. Those who were familiar with GR 28/2025 tended to view it as a positive signal that blockchain is being taken seriously at the policy level. IF-06, from animation and visual effects, remarked:

“The regulation is a good start. It gives us a sense that blockchain is recognized and not something illegal or suspicious. But it’s still very general, and we don’t know how to start implementing blockchain.”

(IF-06, Animation & Visual Effects)

Other participants emphasised that, while the existence of a regulation is encouraging, it does not necessarily translate into clear guidance or practical support for creative MSMEs. IF-10, who works in game development, commented:

“Yes, there is a regulation now, but it doesn’t tell us much about what we should do. We still need more concrete guidelines, especially for small businesses, and maybe programs to help us integrate this technology.”

(IF-10, Game Development)

Some participants were more optimistic about the symbolic value of regulation but nonetheless stressed the need for complementary measures. As IF-15, a visual artist, noted:

“It’s a step in the right direction, especially for people like us who work with digital content. It makes blockchain feel more legitimate. But regulation alone is not enough; we need the resources to implement it.”

(IF-15, Visual Arts)

A recurring concern was the absence of dedicated financial and technical support to accompany regulatory developments. IF-03, a photographer, articulated this concern:

“Regulations are helpful, but without financial support or special programs, it’s still hard for us to adopt blockchain. It feels like the government recognizes it, but there is no concrete help for making this accessible for small businesses.”

(IF-03, Photography)

Overall, participants perceived regulation as an important enabler at the level of legitimacy and legal certainty but insufficient, on its own, to overcome the practical barriers facing creative MSMEs (A. Kumar et al., 2025).

3.4. Perceived Support Needs and Conditions for Feasible Adoption

Beyond identifying barriers and benefits, participants also offered suggestions regarding the conditions that would make blockchain adoption more feasible for creative MSMEs. First, many emphasised the need for financial support in the form of subsidies, grants, or tax incentives to offset initial investment costs. IF-07, from the handicraft sector, argued:

“We need subsidies or grants to help us invest in blockchain. Without financial support, it will be very difficult for small businesses like mine to afford it.”

(IF-07, Handicrafts)

Second, participants repeatedly highlighted digital literacy and training as critical prerequisites. IF-02 stressed the importance of accessible capacity-building initiatives:

“The government should provide more affordable workshops and training on blockchain, not only theory but also how it can be applied in our businesses.”

(IF-02, Fashion Design)

Third, clearer regulatory guidance and communication were seen as essential for building confidence. IF-15 underlined this point:

“There’s a lack of clarity about how blockchain fits into our legal and tax obligations, especially when we talk about using it for intellectual property protection.”

(IF-15, Visual Arts)

Similarly, IF-05, from music production, linked regulatory clarity with the willingness to experiment:

“Blockchain will only work if we know that the regulations are clear and that we are safe to use it without worrying about legal issues.”

(IF-05, Music Production)

Finally, several participants noted that ecosystem-wide incentives and leadership would be important. IF-10 suggested that broader adoption would be more likely if key actors take the lead:

“If the government offers incentives like tax reductions or special programs for those who adopt blockchain, it would motivate more MSMEs. It also helps if big companies or platforms start using it, so we can follow their example.”

(IF-10, Game Development)

Taken together, these accounts indicate that creative MSMEs do not reject blockchain outright. Instead, they view it as a promising but currently inaccessible innovation that could contribute to more transparent and sustainable accounting practices, provided that technical complexity, cost barriers, capability gaps, and regulatory ambiguity are addressed through targeted support and ecosystem collaboration (Pujari & Saha, 2024).

These constraints are not unique to Indonesia. Similar combinations of informality, limited digital infrastructure, and resource-constrained MSMEs are reported across many emerging economies. In this sense, the Indonesian creative economy can be seen as a critical case that illustrates how blockchain’s technical promise collides with the everyday realities of Global South business environments, where basic bookkeeping, connectivity, and access to trusted intermediaries cannot be taken for granted.

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpreting Adoption Barriers Through TAM and DOI

The results show that creative MSMEs perceive blockchain as highly complex, costly, and risky, while simultaneously recognising its potential benefits. This pattern is consistent with the core constructs of both the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and Diffusion of Innovation (DOI) theory. TAM posits that perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use are key determinants of technology acceptance (Davis, 1989). In this study, owners and managers clearly saw the usefulness of blockchain for transparency, intellectual property protection, and secure payments, yet judged it as difficult to understand and implement, reflecting low perceived ease of use.

From a DOI perspective, participants’ descriptions map strongly onto complexity, relative advantage, and compatibility. Rogers (2003) defines complexity as the degree to which an innovation is perceived as difficult to understand and use, and highlights relative advantage and compatibility as positive drivers of adoption. The informants frequently portrayed blockchain as “too complicated” and “too advanced” for small creative firms, indicating high perceived complexity. At the same time, they did not yet see a relative advantage that clearly outweighed the costs and risks when compared to simpler tools such as spreadsheets or off-the-shelf accounting applications.

The findings also suggest that compatibility is not merely a technical issue but deeply intertwined with the informal and sometimes fragmented nature of accounting practices in creative MSMEs. Many firms are still in the process of establishing basic bookkeeping routines and adopting cloud accounting or digital bookkeeping tools. Similar studies on digital and cloud accounting adoption among MSMEs in Indonesia find that low digital financial literacy, limited use of formal digital accounting systems, and reliance on informal practices significantly impede adoption (Herdiyeni et al., 2025; Iriyadi et al., 2023; Rohaeni et al., 2025; Zulfikar et al., 2022). In this context, blockchain is perceived as “several steps ahead” of current capabilities, which lowers both perceived ease of use (TAM) and perceived compatibility (DOI).

Importantly, the barriers identified here extend beyond the individual–cognitive level emphasised by classical TAM. Shortages of human resources with blockchain expertise, concerns about cybersecurity, and uncertainties about integration with existing systems mirror findings from broader studies on blockchain adoption in SMEs, which classify barriers into technological, financial, organisational, and regulatory dimensions (Khuc et al., 2024; Nisar et al., 2024; Treiblmaier et al., 2021). This indicates that any model of blockchain adoption in creative MSMEs needs to incorporate structural and institutional constraints alongside individual perceptions. In this sense, the integrated TAM–DOI lens helps reveal how perceived usefulness is undermined by high perceived complexity and low compatibility, and how these perceptions are shaped by resource limitations and regulatory ambiguity.

4.2. Benefits, Sustainable Accounting, and the ESG/SDG Agenda

Despite substantial obstacles, participants articulated a clear vision of how blockchain could support transparent and sustainable accounting. They emphasised tamper-resistant, time-stamped transaction records, secure and efficient payments, and verifiable ownership of creative works as key potential benefits. These perceptions align closely with prior research that highlights traceability, transparency, information sharing, and decentralisation as core advantages of blockchain in supply chains and financial contexts (Hou & Xu, 2024; Nagariya et al., 2024; Radmanesh et al., 2023).

In the creative industries, blockchain-based NFTs and smart contracts have been identified as promising tools to protect intellectual property, track usage, and automate royalty payments (Susilatun et al., 2023). The participants in this study echoed these opportunities, particularly in sectors such as music, visual arts, and design where plagiarism and unauthorised reuse are pervasive. Their emphasis on authenticated ownership, verifiable originality, and automated revenue sharing underscores the potential for blockchain to contribute to governance (G) and social (S) dimensions of ESG: more transparent value flows, fairer income distribution, and stronger protection of creators’ rights (Divya & Arunkumar, 2024; Gautam, 2022).

From an accounting perspective, the idea of a shared, immutable ledger for project finances and royalty flows resonates with calls for sustainable accounting systems that provide reliable, auditable information to a wide range of stakeholders. Recent work on blockchain in supply chain management and risk management shows that enhanced transparency and traceability can support sustainability reporting and ESG-oriented decision-making (Herdiyeni et al., 2025; Vafaei-Zadeh et al., 2025). In creative MSMEs, similar mechanisms could facilitate more credible reporting of revenues from digital platforms, more accurate recognition of intangible assets and IP-related cash flows, and more robust evidence for tax and regulatory compliance.

Thus, the findings support the working expectation that creative MSMEs will perceive blockchain as useful when they understand its relevance for transparency, IP protection, and trusted transactions (R. Kumar et al., 2024; Wu & Yu, 2023). At the same time, they extend existing literature by showing that these perceived benefits are not purely technical; they are deeply linked to normative concerns about fairness, recognition, and long-term career sustainability in the creative fields. In this way, blockchain is not only a digital innovation but also a potential governance tool for more equitable creative ecosystems, contributing to broader SDG objectives related to decent work, innovation, and inclusive economic growth.

4.3. Regulatory Context, Legitimacy, and Ecosystem Readiness

The results reveal a nuanced view of the regulatory environment. Participants welcomed Government Regulation No. 28 of 2025 and related policies as signals that blockchain is gaining legal recognition and legitimacy in Indonesia. However, they also described these regulations as high-level and distant, offering little concrete guidance for implementation in creative MSMEs.

This resonates with broader research showing that institutional support and regulatory clarity are crucial enablers of blockchain adoption, but that early-stage regulations often focus on high-level risk management and sectoral licensing rather than practical guidance for SMEs (Hou & Xu, 2024; Mutamimah et al., 2023).In many cases, SMEs perceive regulations as either irrelevant to their specific use cases or as adding compliance burdens without providing compensating support.

The participants’ repeated calls for targeted training programmes, subsidies, and sandbox-like experimentation spaces highlight a gap between formal recognition and effective implementation. This gap is particularly salient in creative MSMEs, where informal business practices and limited engagement with formal financing channels are common. Studies on digital accounting and bookkeeping adoption among Indonesian MSMEs similarly report that government initiatives and digital tools have limited impact when not accompanied by sustained capacity-building and tailored incentives.

For public sector accounting, the implications are twofold. First, if creative MSMEs participating in publicly funded programmes use blockchain-based systems to record transactions, subsidies, and royalty flows, this could create richer, tamper-resistant audit trails for supreme audit institutions and line ministries. Second, more granular, real-time data on creative economy transactions could feed into public financial management and SDG reporting frameworks, allowing governments to assess whether their investments in digital and cultural industries are generating inclusive and sustainable outcomes.

Consequently, blockchain adoption in creative MSMEs should be understood not as an isolated firm-level decision but as an outcome of ecosystem readiness. Regulatory agencies, industry associations, platforms, and educational institutions all shape perceptions of risk, provide—or fail to provide—access to knowledge and expertise, and influence the diffusion of success stories that make blockchain more observable and trialable (in DOI terms). The findings suggest that, in the absence of visible role models and accessible support infrastructures, creative MSMEs remain cautious, even when they recognise the technology’s potential

The tension between high-level recognition and low-level implementation is also characteristic of many Global South jurisdictions, where regulatory innovation often outpaces institutional capacity and SME-oriented support schemes. Reading the Indonesian case in this wider perspective suggests that questions of blockchain adoption are inseparable from broader state–business relations and from the uneven geographies of digital governance in the Global South.

4.4. Theoretical Contributions: Extending TAM and DOI in a Creative MSME Context

Integrating TAM and DOI in this study sheds light on how individual perceptions and innovation attributes interact with structural constraints in the context of blockchain-enabled accounting for creative MSMEs. Consistent with TAM, perceived usefulness emerged as a strong motivator, particularly related to transparency, IP protection, and secure payments, whereas perceived ease of use was undermined by technical and organisational complexity.

From a DOI perspective, the findings reaffirm the centrality of relative advantage, compatibility, and complexity as determinants of adoption. However, they also extend these constructs in several ways:

Complexity is not only technical but also regulatory and institutional: uncertainty about taxation, legal status of smart contracts and NFTs, and dispute resolution processes contributes to perceived complexity beyond interface or system design.

Compatibility is shaped by the degree of informality in accounting practices and the creative sector’s reliance on relational contracts and platform-mediated interactions; blockchain has to fit not only existing IT systems but also entrenched business norms and power relations.

Observability and trialability depend on ecosystem actors (platforms, associations, large clients) who can demonstrate working models and provide low-risk entry points.

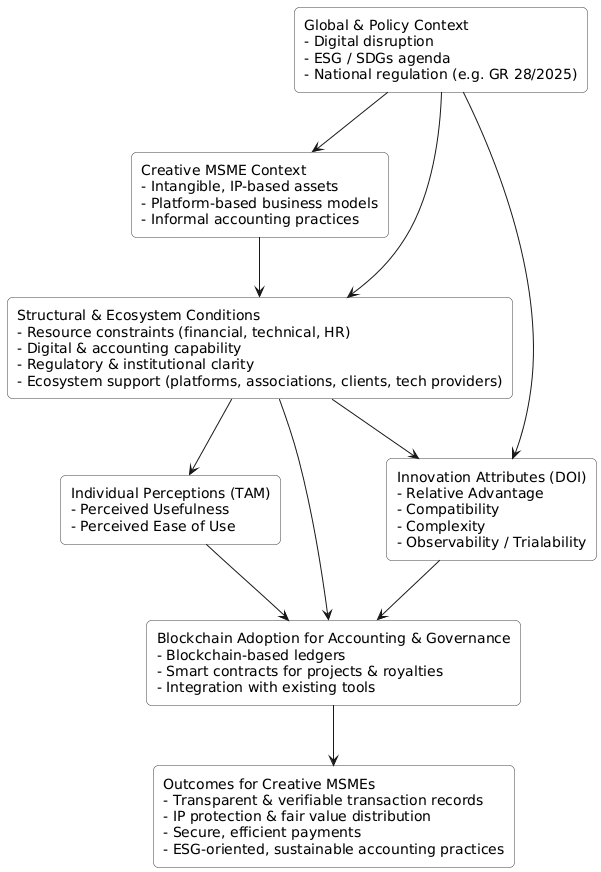

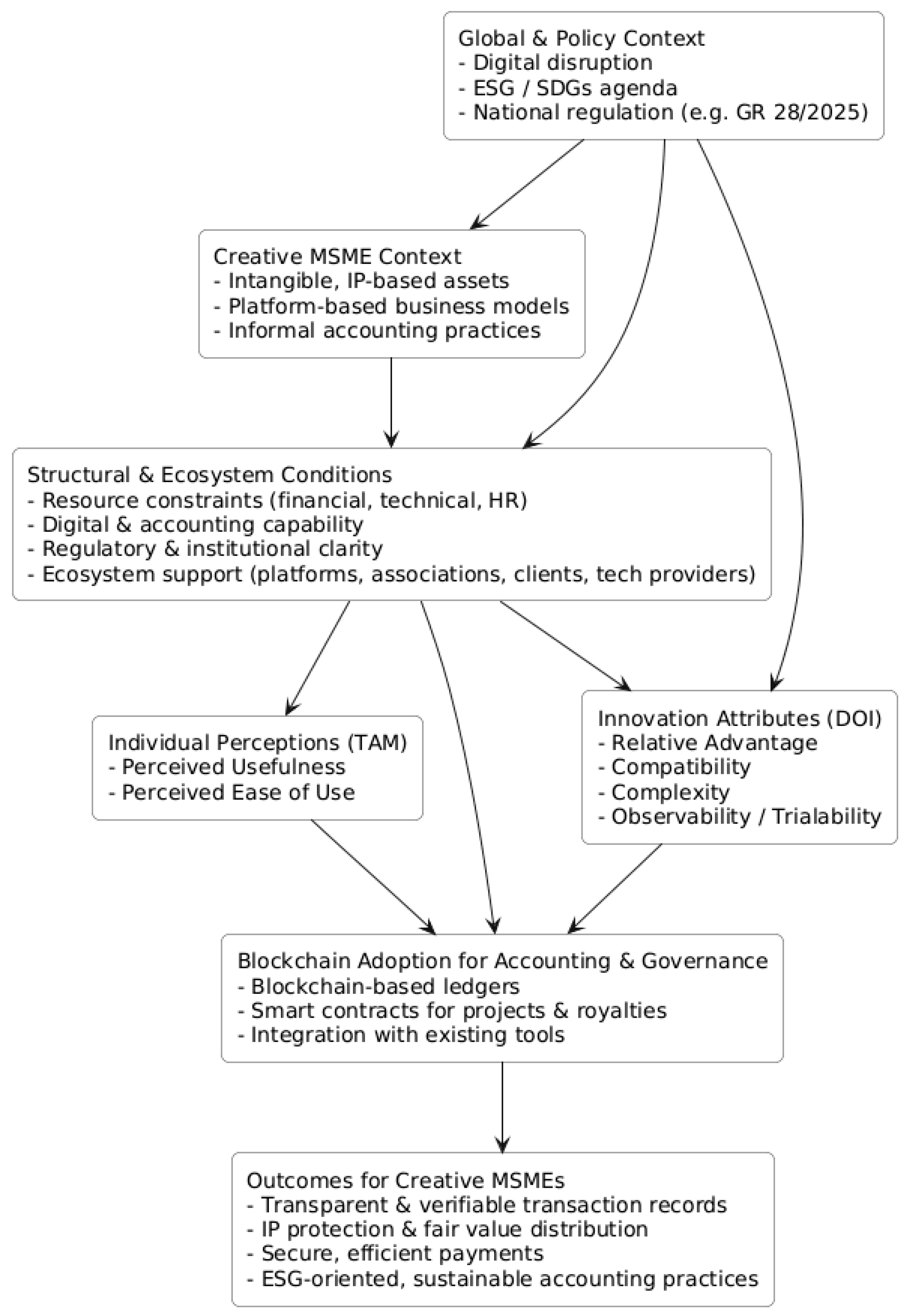

Figure 1 summarises the integrated framework emerging from this study, showing how global and policy context, creative MSME characteristics, structural and ecosystem conditions, individual perceptions (TAM) and innovation attributes (DOI) interact to shape blockchain adoption and its accounting outcomes.

These nuances suggest that traditional TAM/DOI applications, which often focus on relatively formalised sectors and clearer institutional environments, may understate the role of informality, IP-related vulnerabilities, and fragmented governance structures in shaping blockchain adoption. The study therefore contributes to theory by showing how adoption constructs play out in a creative MSME setting where intangible assets and platform-based business models are central, and by highlighting the need to incorporate ESG and sustainability considerations into models of digital innovation adoption (Lulaj & Brajković, 2025).

4.5. Practical and Policy Implications

The findings carry several implications for practitioners and policymakers seeking to promote blockchain-enabled, ESG-oriented accounting in the creative economy.

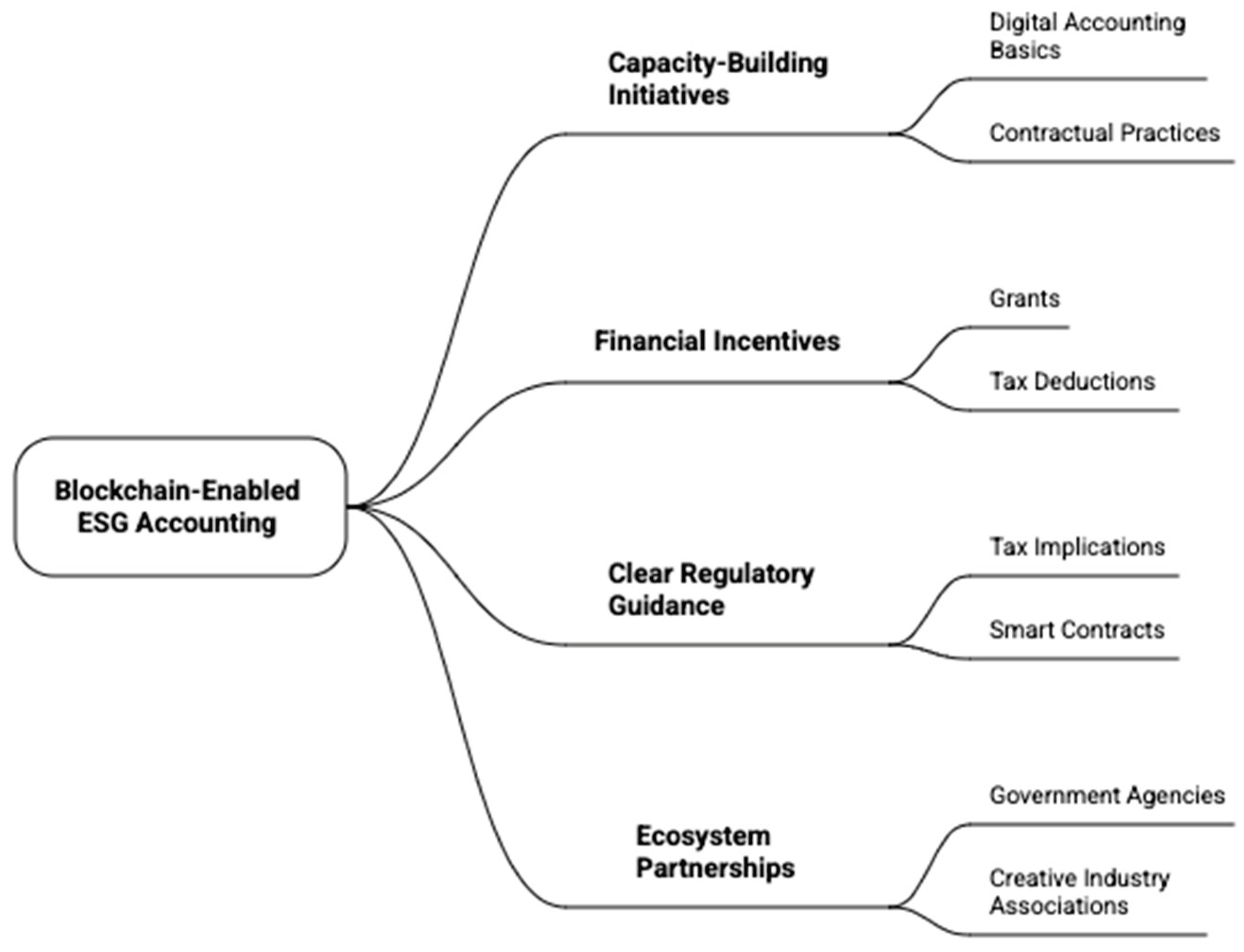

Figure 2 summarises the key policy levers identified in this study—capacity-building initiatives, financial incentives, clear regulatory guidance, and ecosystem partnerships—to support blockchain-enabled ESG accounting in the creative economy (Hamundu et al., 2020; Mishra et al., 2025; Pedreño et al., 2021; Sheela et al., 2023; Susilatun et al., 2023).

First, capacity-building initiatives should be sequenced and contextualised. Rather than introducing blockchain in isolation, training programmes could start by strengthening basic digital accounting and contractual practices, then demonstrate how blockchain can build on these foundations to enhance transparency and IP protection. Evidence from digital accounting initiatives among MSMEs shows that stepwise progression from basic digital tools to more advanced systems is more effective than “technology leaps”. Second, financial incentives such as grants, subsidies, or tax deductions could lower perceived cost barriers and signal the seriousness of policy ambitions. This is consistent with broader SME digitalisation policies, where targeted financial support has been shown to accelerate adoption of cloud accounting and other digital tools and regulators should provide clear, sector-specific guidance on how existing rules apply to blockchain use in creative industries. This includes clarifying tax implications, legal recognition of smart contracts and tokenised assets, and mechanisms for dispute resolution. Such clarity would reduce perceived regulatory risk and make it easier for MSMEs to assess the feasibility of adoption.

Fourth, ecosystem partnerships matter. Collaboration between government agencies, creative industry associations, platforms, and technology providers could create shared infrastructures—such as platform-integrated blockchain services or sectoral registries for IP—that lower individual firms’ entry costs. Lessons from blockchain implementations in supply chains suggest that network-level solutions are often more impactful than standalone firm-level projects. In creative industries, similar consortia could facilitate standardised practices for registering works, distributing royalties, and verifying transactions.

Taken together, the findings show that blockchain-enabled ESG accounting cannot be understood only as a technical choice at the firm level. Instead, it reflects how digital innovations are filtered through the structural conditions of the creative economy in the Global South: informal accounting routines, platform-dependent revenues, thin financial buffers, and evolving but often ambiguous regulatory frameworks. The Indonesian case therefore offers an analytically generalisable lens for other creative economies in Asia, Africa and Latin America that face similar tensions between ambitious digital-transformation agendas and the everyday constraints of MSME life.

4.6. Future Research Directions

The study’s qualitative and contextual nature opens several avenues for future research. First, there is scope for quantitative studies that build on the themes identified here to develop and test extended TAM/DOI models of blockchain adoption in creative MSMEs, incorporating constructs such as perceived regulatory clarity, ecosystem support, and IP-related risk. Second, comparative research across countries or sectors could examine how different institutional environments, platform structures, and cultural norms shape blockchain adoption for sustainable accounting.

Third, further case studies of early adopters in the creative industries—such as platforms or collectives that have implemented blockchain-based IP registries or smart contract systems—could provide detailed insights into implementation strategies, governance arrangements, and impacts on creators’ incomes and bargaining power. Fourth, future work could explore the environmental dimension of blockchain use in creative MSMEs, assessing trade-offs between energy consumption and governance benefits, especially as newer, more energy-efficient consensus mechanisms are deployed.

Overall, the findings underscore that harnessing blockchain for transparent and sustainable accounting in creative MSMEs is not primarily a question of technical feasibility, but of aligning technology design, institutional frameworks, and ecosystem support with the realities of small creative firms in emerging economies.

5. Conclusions

This study set out to explore how blockchain can be harnessed for transparent and sustainable accounting in creative MSMEs amid rapid digital disruption. Focusing on Indonesia’s creative economy, it examined how owners and managers perceive blockchain’s usefulness and ease of use, what barriers they face in adopting it, and under what conditions the technology is viewed as a viable tool for strengthening governance and accountability. Drawing on in-depth interviews with 18 practitioners across diverse creative subsectors, the findings reveal a persistent gap between blockchain’s perceived potential and its limited actual use in everyday accounting and financial practices.

The results show that creative MSMEs recognise blockchain’s potential benefits—especially for transaction transparency, verifiable records, intellectual property protection, and secure, efficient payments. Participants see value in tamper-resistant ledgers, authenticated ownership of creative works, and smart contract–based revenue sharing, and they link these features to fairer and more professional financial arrangements within creative value chains. These perceptions align with the idea that blockchain can support more transparent, ESG-oriented accounting and contribute to broader sustainable development goals in the creative economy. Taken together, these insights speak directly to debates on finance and accounting in times of global uncertainty. By showing how blockchain-enabled, ESG-oriented accounting can enhance the transparency and resilience of creative MSMEs, the study highlights concrete pathways for sustaining credible and inclusive reporting in volatile and digitally mediated markets.

At the same time, adoption is constrained by a combination of technical complexity, financial constraints, limited digital and accounting capabilities, and perceived risk. Blockchain is widely viewed as “too advanced” and costly for small creative firms that are still struggling with basic bookkeeping and digitalisation, while misconceptions shaped by volatile cryptocurrency markets reinforce perceptions of risk and distrust. Emerging regulations, such as Government Regulation No. 28 of 2025, are welcomed as signals of legitimacy but are experienced as high-level and abstract. Without concrete guidance, targeted support, and accessible experimentation opportunities, such policies do little to alleviate day-to-day adoption barriers. Beyond firm-level implications, the study also points to opportunities for aligning blockchain-enabled accounting in creative MSMEs with public sector accountability agendas, particularly in the design and evaluation of government programmes that finance or incentivise the creative economy.

Theoretically, the study extends the integrated application of TAM and DOI by showing how perceived usefulness can coexist with low perceived ease of use and high perceived complexity in a context marked by informality, intangible assets, and platform dependence. It demonstrates that constructs such as complexity and compatibility must be understood not only in technical terms but also in relation to regulatory uncertainty, informal accounting routines, and ecosystem readiness. In doing so, the research adds nuance to existing models of digital innovation adoption in MSMEs and highlights the need to incorporate ESG and sustainability considerations into analyses of blockchain-enabled accounting, particularly in emerging economies and the wider Global South.

Practically, the findings suggest that realising blockchain’s potential in creative MSMEs requires a sequenced and ecosystem-based approach. Strengthening basic digital accounting, contract management, and financial literacy is a necessary foundation. Building on this, tailored training, financial incentives, sector-specific regulatory guidance, and collaborative infrastructures—co-created by government, industry associations, platforms, and technology providers—can lower entry barriers and create credible pathways for adoption. These policy levers are relevant not only for Indonesia but also for other Global South countries where creative MSMEs operate under similar conditions of informality, resource constraints, and evolving digital infrastructures. Blockchain should thus be seen not as a stand-alone solution but as one element in a broader strategy to formalise, professionalise, and democratise the creative economy’s financial and governance systems.

Finally, the study’s qualitative design and focus on a single national context mean that its findings are not statistically generalisable. Future research could develop and test extended TAM/DOI models quantitatively, compare adoption dynamics across countries and sectors, and conduct longitudinal case studies of early adopters implementing blockchain-based accounting and IP solutions. Despite these limitations, the study provides empirically grounded insight into how creative MSMEs in an emerging economy understand and negotiate blockchain and offers an analytically generalisable framework for designing more inclusive, sustainable, and context-sensitive approaches to blockchain-enabled accounting in creative industries across the Global South.