1. Introduction

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) is a heterogeneous group of disorders that includes ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD). It is characterized by damage to the intestinal mucosa, chronic inflammatory infiltrate, and increased production of proinflammatory cytokines. Despite therapeutic advances over the last two decades with the use of so-called biological agents, a significant proportion of patients remain resistant to treatment [

1].

It is known that the epithelial cells of the intestinal mucosa, in addition to their contribution to the function of absorption and digestion of nutrients, also function as a protective barrier against the (harmful) content of the intestinal lumen and the intestinal flora. In contrast, through the mucosal immune cells located in the lamina propria, it maintains intestinal homeostasis. These intestinal cells form a layer of specialized epithelial cells (IECs) interconnected by tight junctions (the intestinal epithelial barrier). The integrity of this epithelial barrier is of primary importance for the homeostasis of the organism. The pronounced death of IECs increases intestinal permeability, leading to bacterial translocation into the mucosal lamina propria and triggering an inflammatory response that is perpetuated. On the other hand, changes in the programmed cell death (PCD) model of the intestinal epithelium may trigger an inflammatory process [

2].

The pathogenesis of IBD is primarily characterized by extensive damage or death of intestinal epithelial cells, along with abnormal activation or dysregulation of immune cell death and the release of various inflammatory cytokines. Intestinal homeostasis depends on two factors related to enterocytes: survival and functionality. The processes of PCD, which include apoptosis, pyroptosis, autophagy, ferroptosis, necroptosis, and neutrophil extracellular traps, are essential to the pathogenesis of IBD, as they contribute to the death of intestinal epithelial and immune cells. While apoptosis is considered an immunologically silent cell death, pyroptosis and necroptosis are highly inflammatory forms.

In this review, we describe data that highlight PANoptosis as a key process in IBD and a promising therapeutic target in the near future.

2. Programmed Cell Death (PCD)

PCD is a highly regulated cellular process in which specific genes are activated in response to internal or external environmental stimuli, orchestrating the orderly death of the cell. It corresponds to a precise and physiological self-destructive process within the cell that is essential for maintaining homeostasis and regulating disease development. An imbalance in PCD can trigger inflammation and an immune response. So far, several PCD modes have been described, including apoptosis, necroptosis, pyroptosis, ferroptosis, entotic cell death, NETosis, parthanatos, lysosome-dependent cell death, autophagy-dependent cell death, alkaliptosis, oxeiptosis, cuproptosis, disulfidocytosis, and PANoptosis [

3,

4,

5]. Overall, the number of recognized models is constantly expanding as scientific research uncovers new molecular mechanisms. The predominant forms of PCD include apoptosis, necrosis, and pyroptosis. It is argued that the various PCD pathways exhibit significant cross-regulatory interactions that collectively influence cellular outcomes. The major PANoptosis pathways are shown in

Table 1 and are discussed below.

Table 1.

Main Pathways of PANoptosis in IBD.

Table 1.

Main Pathways of PANoptosis in IBD.

| Pathway |

Main Molecules |

Role in IBD |

| |

|

| Apoptosis |

Caspase-8, Fas, TNF |

Regulation of epithelial homeostasis, impaired in severe inflammation |

| Pyroptosis |

NLRP3, Caspase-1, GSDMD |

IL 1β/IL 18 secretion, worsening inflammation |

| Necroptosis |

RIPK1, RIPK3, MLKL |

Mucosal destruction, epithelial barrier disruption |

| PANoptosis |

ZBP1, PANoptosome |

Combined activation and enhancement of inflammation |

2.1. Apoptosis

Apoptosis is a normal and preventive “suicide” behavior. Under certain conditions, apoptosis is initiated by either the extrinsic or the intrinsic (mitochondrial) pathway. The initial processes include cell shrinkage, nuclear fragmentation, and chromatin condensation, which lead to the formation of so-called apoptotic bodies. The apoptotic bodies are then ingested by parenchymal cells and macrophages without an inflammatory reaction. The extrinsic apoptotic pathway begins with the binding of extracellular TNF or Fas ligand to the corresponding death receptors (DRs) at the plasma membrane. Subsequently, FADD or TRADD, adaptor proteins that bind the precursor of caspase-8, are recruited, forming a death signaling complex (DISC). Activation of caspase-8 and subsequent activation of caspase-3/7 ultimately result in apoptosis [

6]. Internal apoptotic stimuli, such as oxidative stress, hypoxia, or toxic substances, induce the intrinsic (mitochondrial) apoptotic pathway. These stimuli activate the B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) family of proteins, altering mitochondrial membrane permeability and releasing cytochrome c into the cytoplasm. Cytochrome c then binds to apoptotic protease-activating factor-1 (Apaf-1), facilitating the assembly of the apoptosome, which triggers procaspase-9 [

7]. Activated caspase-9 then further activates the effector proteins caspase-3/7, resulting in apoptosis.

2.2. Necroptosis

The word necroptosis is a compound of the ancient Greek words “nekros” (dead) and “ptosis” (fall), meaning “fall (in) death”. Necroptosis is a lytic and inflammatory form of PCD that occurs when pathogens or chemical mediators inhibit apoptosis [

8]. Cells that have undergone necroptosis exhibit enlarged mitochondria, multiple fissions, and rupture of the cytoplasmic membrane, leading to cell disruption and leakage of its contents into surrounding tissues. Caspase-8 determines whether a cell undergoes apoptosis or necroptosis. When caspase-8 is inactivated or inhibited, the activated necrosome is formed. The external stimulus binds to death receptors and pattern recognition receptors. Kinase 1 is then activated, followed by the RIPK1 receptor and kinase-3 activation and the formation of the RIPK1-RIPK3 complex (necrosome). The necrosome then phosphorylates kinase 3, which interacts with the MLKL receptor. Finally, phosphorylated MLKL induces cell lysis, releasing DAMPs and thereby triggering the inflammatory response [

9,

10]. Tao S et al. found increased expression and phosphorylation of MLKL and RIPK3 in biopsies from patients with UC, suggesting activation of the necroptosis pathway [

11].

2.3. Pyroptosis

“Pyroptosis” is a term composed of the union of two separate ancient Greek words, namely “πυρ” (-pyr=fire) and “πτώσις” (-ptosis=fall), which together mean “fire fall”. It is a lytic mechanism of programmed cell death that involves cleavage of proteins in the gasdermin D family. Its effects are mediated through nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3)/caspase-1 classical and caspase-4/5/11. Pyroptosis cells exhibit a characteristic morphology characterized by cellular edema, nuclear DNA alterations, cytoplasmic membrane rupture, and cell lysis, resulting in the release of inflammatory factors [

12]. The inflammatory process mediated by this mechanism appears to play a central role in the development and pathogenesis of IBD by disrupting the intestinal epithelial barrier, leading to excessive inflammation and worsening clinical outcomes. Inflammation is mainly activated through the canonical pathway, which involves the assembly of the inflammasome, a multi-protein complex of the innate immune system.

2.3.1. Activation of the NLRP3 Inflammasome

In IBD, the most studied inflammasome is NLRP3 (NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3). Activation of NLRP3 is a two-step process:

Priming: Exposure to pathogens (PAMPs, e.g., LPS) or inflammatory signals (e.g., TNF-α), which activate nuclear factor NF-κB and lead to increased expression of NLRP3 and Caspase-1 proteins.

Activation: Exposure to IBD-associated danger signals (DAMPs), such as extracellular ATP, mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS), or intestinal barrier disruption, induces oligomerization of NLRP3, recruitment of ASC protein, and activation of Caspase-1.

2.3.2. Caspase-1 and GSDMD

Activated Caspase-1 is the main executioner protease of pyroptosis, which performs two critical functions:

Cytokine Maturation: It cleaves the inactive forms of the proinflammatory cytokines Pro-IL-1β and Pro-IL-18, converting them to the biologically active forms IL-1β and IL-18. Both cytokines are elevated in the intestinal mucosa of patients with IBD and exacerbate inflammation.

Pyroptosis Death: It cleaves the protein Gasdermin D (GSDMD). The N-terminal domain of GSDMD released from the cell travels to the cell membrane, where it forms large pores 10–20 nm in diameter. Water influx due to osmotic pressure leads to cell swelling, cell rupture, and, ultimately, the release of intracellular contents, including IL-1β and IL-18, into the extracellular space, triggering an inflammatory cascade.

2.4. PANoptosis

IBD is characterized by extensive inflammatory infiltration of the intestinal mucosa, an imbalance between pro- and anti-inflammatory cells, and alterations in intestinal barrier function. In recent years, studies in human tissue and animal models have shown that disruption of cell death pathways is a fundamental factor in the pathogenesis of the disease.

PANoptosis—a relatively recent term in the literature derived from the ancient Greek words “pan” (pan=total) and “ptosis” (ptosis, fall)—describes a comprehensive form of PCD, which incorporates the characteristics and molecular pathways of three distinct but overlapping mechanisms: apoptosis, pyroptosis, and necroptosis [

13]. The coupling of these pathways leads to a form of cell death characterized by high inflammatory activity and active participation in the pathophysiology of IBD. This mechanism is fundamental in the intestinal mucosa, where uncontrolled PANoptosis leads to increased barrier disruption, systemic release of inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-18), and chronic self-perpetuating inflammation. It is mediated by multiprotein complexes called PANoptosomes (ZBP1-, AIM2-, RIPK1-, and NLRP12-PANoptosomes), which are generated in response to specific stimuli associated with various pathogens or damage. This process contributes to tissue homeostasis by removing damaged cells, while also enhancing the immune/defense system through the release of inflammatory cytokines and damage-related molecular patterns. In particular, in UC and CD, PANoptosis leads to epithelial cell death, disrupts the mucosal barrier, and promotes the inflammatory process. During the course of IBD, apoptosis, necrosis, and pyroptosis occur; therefore, PANoptosis may constitute a novel therapeutic target in the treatment of IBD [

13].

2.4.1. PANoptosis and Pathophysiology of IBD

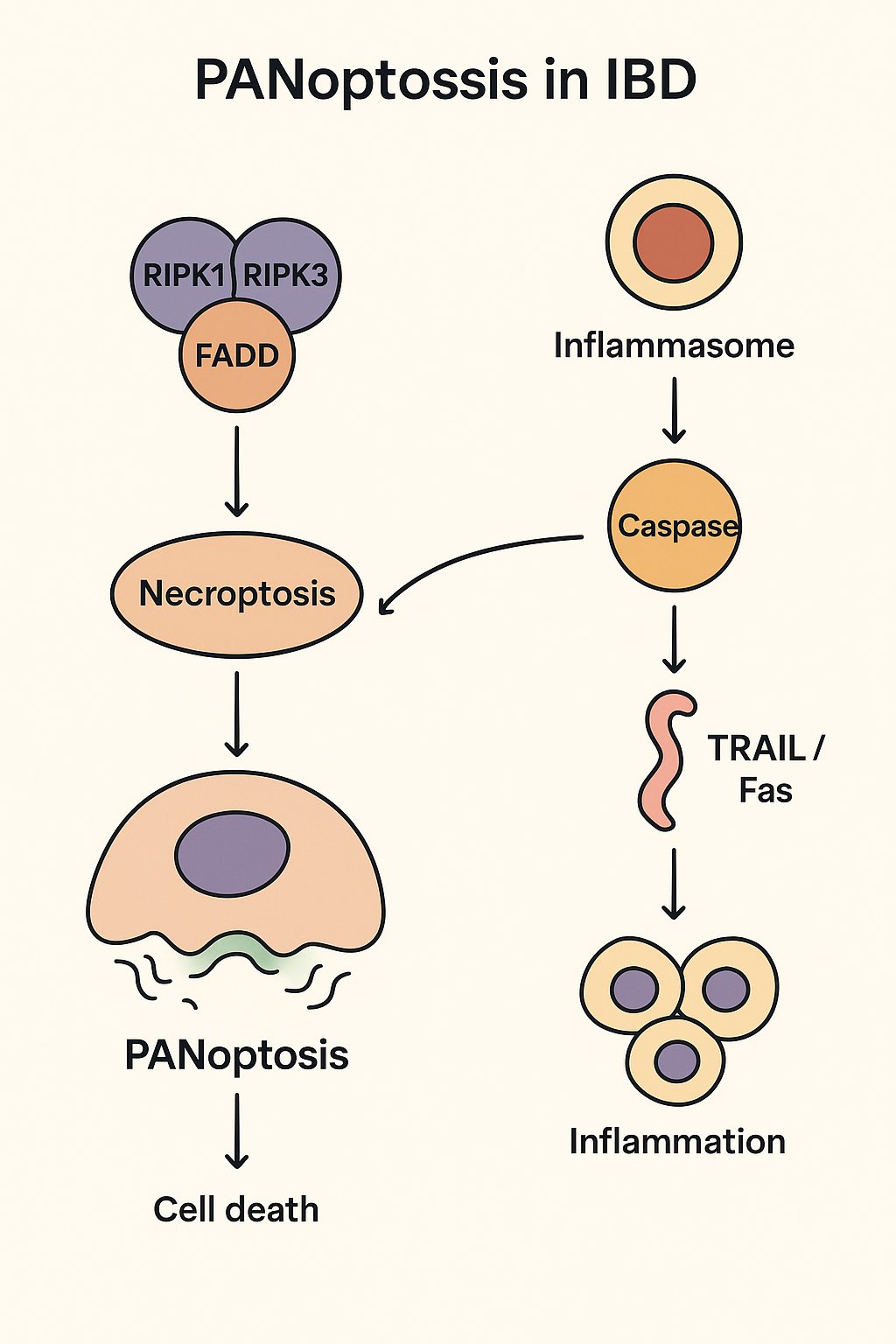

Regarding the molecular mechanisms underlying PANoptosis, it is argued that PANoptosis is mediated by the Panoptosome, also known as the Panoptisome. This complex includes the following key regulators of cell death: ZBP1 (a sensor of cellular stress and infections), RIPK1/RIPK3 (the central kinases of the necroptosis pathway), and Caspase-1/Caspase-8 (which regulate pyroptosis and apoptosis). Activation of the Panoptosome in IBD leads to the simultaneous release of inflammatory cytokines (via pyroptosis) and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) (via necrosis), creating a vicious cycle of inflammation [

14].

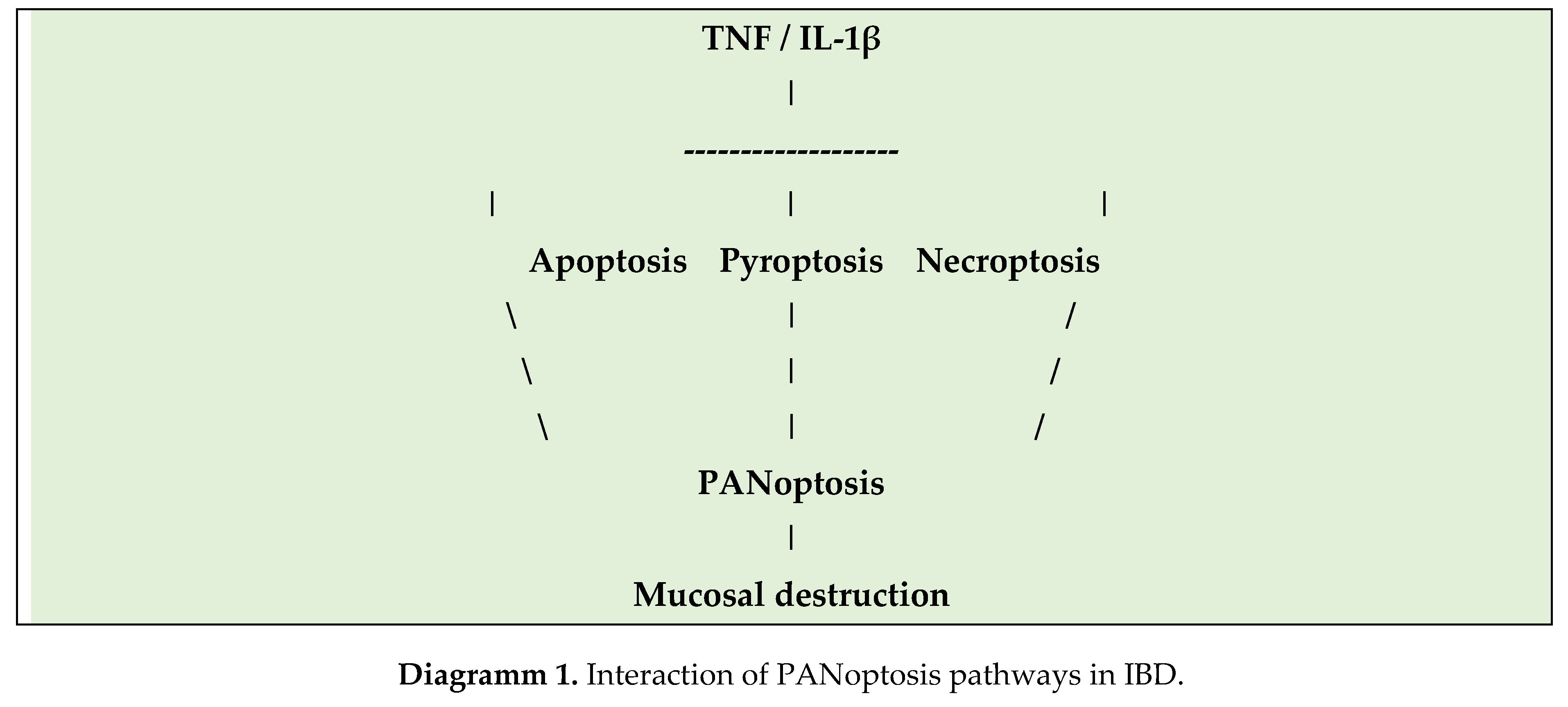

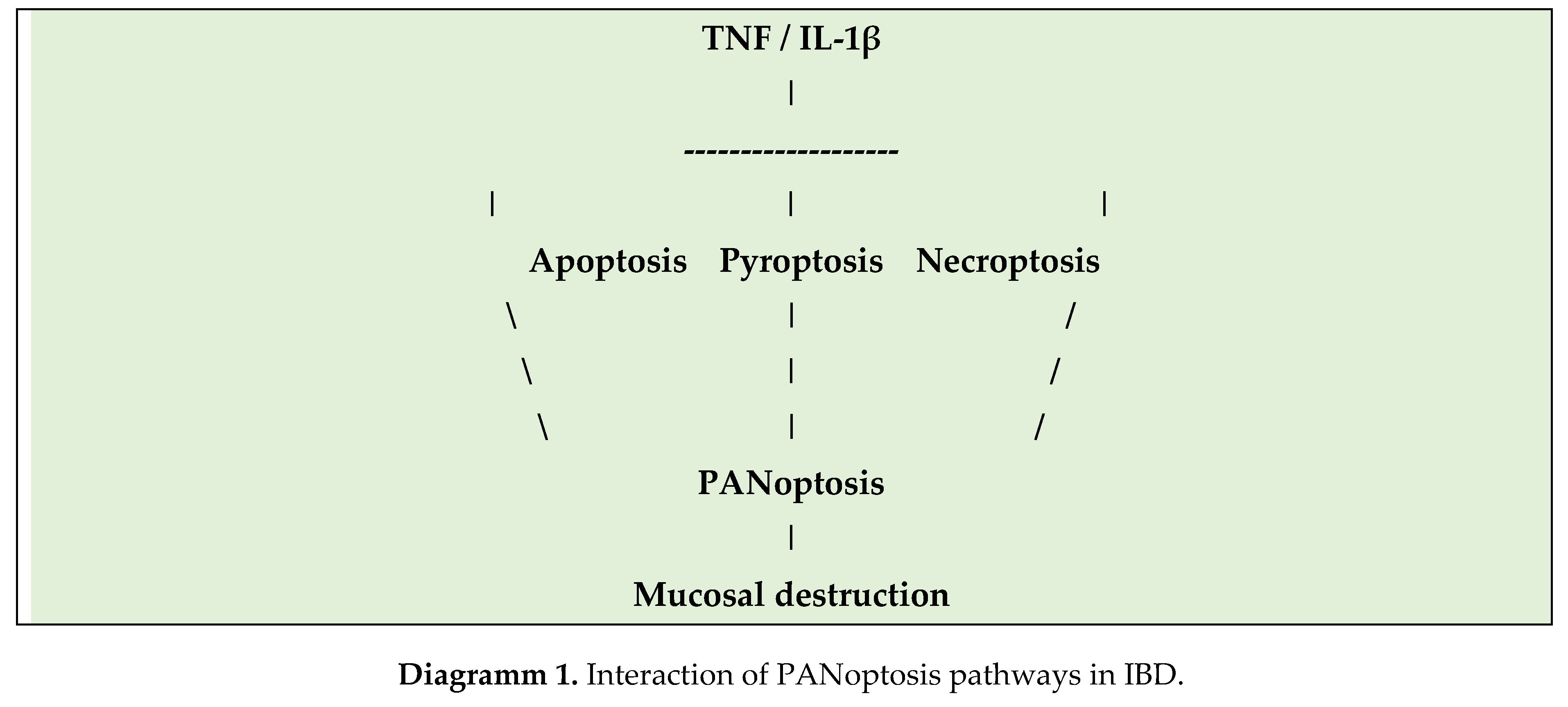

The molecular mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of IBD are associated with increased NLRP3 inflammasome activation in patients with IBD. Overexpression of RIPK3 and MLKL in inflamed mucosa and impaired function of protective apoptosis mechanisms in the intestinal epithelium lead to barrier leakage. Moreover, activation of PANoptosis pathways leads to increased production of IL-1β and HMGB1, exacerbating intestinal inflammation. The processes of PANoptosis in IBD are shown in the following Graphical Abstract.

Regarding the differences between UC and CD, the two diseases present differences in the mechanisms of cell death. Thus, in UC, intense induction of necrosis and inflammatory destruction of the mucosa is observed. In contrast, in CD, necroptosis activation is mainly observed in myeloid and epithelial cells, with greater involvement of RIPK3/MLKL. These differences also underpin the development of targeted drugs that regulate specific PANoptosis pathways for each disease. In more detail, in CD, it has been shown that PANoptosis of intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) promotes the inflammatory process. Zhao J et al., in a recent study including in vitro and in vivo experiments, demonstrated that Intelectin-1 is overexpressed to a statistically significant degree in the epithelial intestinal cells of inflamed intestinal mucosa in CD patients, and it is significantly correlated with inflammatory markers that increase in CD. In this way, they promote the inflammatory process and PANoptosis and weaken the tight junctions of intestinal epithelial cells through binding to the protein calpain-2. The E3 ubiquitin ligase directly interacts with calpain-2, mediating its ubiquitination and degradation. At the same time, they showed that PANoptosis induced by the Z-DNA binding protein 1 antagonizes the PANoptosis-promoting protein calpain-2, demonstrating that Intelectin-1 improves colonic inflammation and intestinal barrier function in interleukin-10 knockout mice. Therefore, pharmacological inhibition of Intelectin-1 ameliorates epithelial cell damage and colitis both in vivo and in vitro, suggesting that therapies targeting Intelectin-1 and PANoptosis are promising strategies for the treatment of patients with CD [

15].

Diagramm 1 shows the interplay of PANoptosis pathways in IBD.

Twelve genes are involved in the PANoptosis processes of IBD, namely OGT, TLR2, GZMB, TLR4, PPIF, YBX3, CASP5, BCL2L1, CASP6, MEFV, GSDMB, and BAX. In their study, Zhang M et al showed that these genes are associated with TNF-α signaling, NF-κB, pyroptosis, and necroptosis, and that the nomogram model and calibration curves have substantial predictive value. They also found that immune cell infiltration was increased in patients with IBD, and the model genes were closely associated with infiltration by various immune cells. The transcription factors associated with DE-PRGs were RELA, NFKB1, HIF1A, TP53, and SP1. The findings of the study indicate that the DE-PRG model genes have satisfactory prognostic value in IBD, and that PANoptosis processes participate in the pathogenesis of the disease through TNF signaling, NF-κB, pyroptosis, necroptosis, and immune mechanisms [

16]. Li Y et al. analyzed transcriptomic data from patients with UC, CAC, and control groups to identify genes associated with PANoptosis. Four PANoptosis hub genes (CASP1, LCN2, STAT3, ZBP1) were identified as factors that favor the development of UC. Strong binding affinity between epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors and target proteins was also found, suggesting therapeutic potential. The authors conclude that the PAR-Score based on PANoptosis genes predicts the progression of UC and the therapeutic response to anti-TNF-α therapy. EGFR inhibitors may serve as potential therapeutic agents for UC and the prevention of ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer [

17]. Yang Y et al showed that PANoptosis plays a vital role in CD by altering the immune system and interacting with CD-related genes. More specifically, in their study, they identified 10 PANoptosis-related genes with satisfactory diagnostic performance: CD44, CIDEC, NDRG1, NUMA1, PEA15, RAG1, S100A8, S100A9, TIMP1, and XBP1. These genes showed significant associations with certain immune cell types and CD-related genes [

18].

Regarding the role of Interferon-γ, it is known that it affects intestinal epithelial cells in many ways, being overexpressed in the lamina propria of the intestinal wall. Lee C et al, in a recent study using intestinal organoids (enteroids) derived from non-IBD controls and CD patients found that, IFN-γ induced PCD of enterocytes in both control and CD patient enteroids in a dose-dependent manner. All three processes, namely pyroptosis, apoptosis, and necroptosis, were activated in enteroids, suggesting that PANoptosis was the primary process of PCD induced by IFN-γ and that it was cell-type dependent on the epithelial enterocyte. They also found that upadacitinib, a selective JAK1 inhibitor used in the treatment of IBD, effectively blocked IFN-γ-induced cytotoxicity and PANoptosis [

19].

3. Pharmacological Targeting Strategies of PANoptosis

The therapeutic potential of the PANoptosis target lies in its role as a unified PCD pathway that can be manipulated for IBD and other malignant and non-malignant disorders. Targeting PANoptosis involves developing drugs that can either induce it or eliminate inflammatory cells. Key targets include proteins within the PANoptosome complex, such as sensors like NLRP3 and ZBP1, and executioners like caspase-8, PIPK1/3, and gasdesmins (GSDM. This targeted regulation of PANoptosis constitutes a promising therapeutic approach, as it allows intervention across multiple molecular pathways involved in IBD pathogenesis. The main categories of pharmacological agents include necroptosis inhibitors, inflammasome inhibitors, anti-apoptotic regulators, immunobiological agents, and combination strategies [

20].

Table 2 shows the pharmacological agents that target PANoptosis pathways.

Table 2.

Drugs targeting PANoptosis pathways.

Table 2.

Drugs targeting PANoptosis pathways.

| Category |

Example |

Development stage |

Basic mechanism |

| RIPK1 |

GSK2982772 |

Clinical |

Inhibition of necroptosis. |

| inhibitors |

|

|

|

| Inflammasome blockers |

MCC950 |

Preclinical |

NLRP3 |

| |

|

|

inhibition |

| SMAC mimetics |

Birinapant |

Preclinical |

Inhibition of IAP-depended pathway. |

| Anti-TNF |

Infliximab |

Clinical |

Induction of apptosis of T-cells. |

In more detail, targeting PANoptosis requires inhibiting the central nodes that regulate the three types of death, as shown below [

14].

3.1. RIPK1/2/3 and MLKL Inhibitors

RIPK1 and RIPK3 proteins are central regulators of necroptosis and participate in the formation of the necrosome. Pharmacological inhibition of RIPKs has emerged as a potential therapeutic route in IBD. Recent data highlight PP6 as a regulator of RIPK1-dependent PANoptosis, making it a possible new molecular intervention target [

21]. Phosphoprotein analyses of patients with UC reveal MLKL/RIPK3 activation, suggesting a necroptosis pathway [

11]. Liu C et al. recently described a mechanism in which P2Y14R modulates MLKL-dependent necroptosis and protects against colitis in experimental animal models [

22]. Similar results were described by Lu et al. In their experimental colitis study, they showed that RIPK1 inhibition protects tight junctions and reduces damage in DSS colitis [

23]. Examples of such agents are:

GSK2982772: selective RIPK1 inhibitor with positive data in reducing symptoms and biomarkers of inflammation.

Necrostatin-1 (Nec-1): one of the first RIPK1 inhibitors, with impressive activity in animal models (reduction of mucosal damage and cytokines).

SZ-15, RIPA-56, and other newer small-molecule inhibitors.

Regarding the mechanism of action, RIPK1/3 inhibitors prevent the transcriptional activation of MLKL and, consequently, cell lysis through necroptosis, reducing the release of DAMPs and inflammatory factors. In more detail, Necrostatin-1 (Nec-1) is the most widely studied inhibitor of Receptor-interacting protein kinase 1 (RIPK1). RIPK1 is a central protein that functions as a “switch” between the survival/inflammation pathways (via NF-κB), apoptosis (via Caspase-8), and necrosis (via RIPK3/MLKL). The mechanism of action of Nec-1 is related to the fact that it acts as a stereoselective inhibitor of the RIPK1 kinase, preventing the formation of the necrosome (necrosome: RIPK1-RIPK3-MLKL). In this way, it i) inhibits necrosis by achieving a reduction in inflammatory disruption of the cell membrane and ii) reduces inflammation since RIPK1 participates in the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and therefore its inhibition indirectly reduces inflammation. The administration of Nec-1 or newer, more selective inhibitors of RIPK1 (Nec-1s or GSK’s inhibitors) in experimental colitis models in rats (DSS or TNBS colitis), the drug resulted in i) a reduction in the Tissue Damage Index with a significant improvement in the clinical score (reduction in weight loss, bleeding), ii) protection of the intestinal mucosa with an impressive reduction in IEC necrosis and improvement in the histological picture, iii) a reduction in the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β) in the intestinal tissue, and iv) restoration of the mucosal barrier, contributing decisively to maintaining its integrity. It should be emphasized that, while Nec-1 primarily targets necrosis, RIPK1’s central role in regulating PANoptosis makes it a powerful tool for holistic intervention in cell death in IBD [

13]. In a randomized, placebo-controlled phase I/II study, Weisel K et al. showed that GSK2982772 is safe but lacks significant clinical superiority as monotherapy in active UC, suggesting that large randomized trials are needed in the near future to accurately determine the efficacy or otherwise of this agent [

24].

3.2. Inflammasome / NLRP3 Inhibitors

Inflammasome activation is a key process in PANoptosis, especially in UC. Targeting NLRP3 is considered one of the most promising therapeutic axes. Such pharmacological agents include MCC950 (NLRP3 inhibitor), which decreases IL-1β and IL-18 production, and CY-09 and β-caryophyllene, which have been shown to reduce IL-1β and IL-18 production in experimental colitis in mice [

25,

26].

3.3. Caspase Regulation

Pharmacological regulation of caspases can lead to either protection of the intestinal epithelium or inflammatory suppression of immune cells. Examples include Caspase-8 inhibitors, which, in experimental colitis models, reduce inflammation and IL-1β levels, and Pan-caspase inhibitors, which appear to limit epithelial damage.

3.5. IAPs / SMAC Mimetics

IAPs (Inhibitors of Apoptosis Proteins) negatively regulate apoptosis. SMAC mimetics are a newer class of drugs that reverse this action. Examples include the agents Birinapant and LCL161. Data in patients with IBD are mainly preclinical, but show the potential to reduce damage through the regulation of cell death and inflammation.

3.6. Anti-TNF and Other Biological Agents

Although anti-TNF agents were not designed to target PANoptosis, they do affect the pathway by modulating T-cell and macrophage apoptosis. Examples include Infliximab and Adalimumab, which induce lymphocyte apoptosis and reduce cytokine production. In addition, other biologic agents, such as ustekinumab and vedolizumab, modulate immune cell responses and may have a secondary effect on cell death.

Table 3 presents the therapeutic targets and preclinical results of PANoptosis inhibitors in IBD.

Table 3.

Therapeutic Targets and Preclinical Data of PANoptosis Inhibitors in IBD.

Table 3.

Therapeutic Targets and Preclinical Data of PANoptosis Inhibitors in IBD.

| Target |

Involved pathway |

Example of Inhibitor / Molecule |

Mechanism of |

Preclinical Effect |

| action |

on IBD |

| RIPK1 |

Necrosis |

Necrostatin-1 (Nec-1) |

Inhibition of RIPK1 kinase, prevention of Necrosoma formation. |

Reduction of damage, improvement of histology, reduction of TNF-α, inhibition of necrosis. |

| NLRP3 |

Pyroptosis |

MCC950 |

Inhibition of NLRP3 |

Reduction of IL-1β/IL-18, improvement of colitis symptoms. |

| inflammasome |

| assembly. |

| GSDMD |

Pyroptosis |

Disulfiram |

Inhibition of the GSDMD channel, preventing cytokine release. |

Reduction of cell death and inflammation. |

| Pan-Caspases |

Apoptosis/ |

Z-VAD-FMK |

Non-selective |

Suppression of apoptosis/pyroptosis. Risk of diversion to RIPK1-dependent necrosis. |

| pyroptosis |

caspase inhibition. |

4. Other Therapeutic Agents

Other therapeutic agents include dietary factors that affect the intestinal microbiota, agents that act on mitochondrial function, and plant products such as diasmin [

14]. It has long been proven that IBD is pathogenetically associated with the presence of dysbiosis of the intestinal microflora. Dysbiosis involves the excessive growth of harmful microflora, accompanied by a parallel decrease in beneficial microflora, contributing, in synergy with other factors, to the onset of IBD. Various plant compounds have been shown to have beneficial effects on the course of IBD by improving or eliminating dysbiosis, reducing intestinal mucosal inflammation, and restoring increased intestinal barrier permeability. This is achieved through the regulation of signaling pathways such as TGF-β/Smad, TLR-4/NF-ΚB/MAPK, TLR2-NF-κB, autophagy, pyroptosis, glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, and amino acid metabolism; Nrf-2/HO-1; microbiota-macrophage-arginine metabolism; and bile acid metabolism, as well as through increased synthesis of short-chain fatty acids and other metabolites. However, the adverse effects of their excessive use, such as worsening of immune responses, should also be taken into account. Plant-based dietary compounds can contribute decisively to the treatment of IBD by modulating PANoptosis mechanisms [

27].

Mitochondrial dysfunction results in the production of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (mtROS), which negatively affect intestinal barrier function, increasing intestinal mucosal permeability and promoting the inflammatory process through immune cell invasion. Therefore, targeting mtROS may be a therapeutic target. Gong W et al generated regulatory T cell (Treg)-derived exosomes loaded with selenium and the synthetic mitochondria-targeting SS-31 tetrapeptide, which binds mitochondria via a peptide linker that is cleaved by metalloproteinases. This actively targetable exosome-derived delivery system prevents mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production, thereby preventing PANoptosis. This exosome-delivery platform may be a promising therapeutic strategy for treating IBD [

28]. Other natural products derived from plants, fruits, and vegetables have also been shown to regulate PCD and may therefore have both preventive and therapeutic effects in IBD [

29]. The study by Ye Z et al investigated the role of mitochondria in the development of UC using cellular and animal models, as well as clinical samples. Their results showed that IEC damage in experimental DSS colitis involves mitochondrial fission mediated by dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1) and PANoptosis dependent on Z-DNA binding protein 1 (ZBP1). ZBP1-PANoptosis and Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission were observed in patients with UC, depending on disease severity. Hyperactivated mitochondrial fission led to the production of mitochondrial oxygen radicals and the appearance of PANoptosis, independent of ZBP1’s Zα domain, through sulfenylation of Cys327. Saquinavir has also been shown to inhibit mitochondrial fission, thereby enhancing therapeutic efficacy in experimental colitis [

30].

Diosmin is a naturally occurring flavonoid with anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. Tan C et al investigated these properties of Diosmine in the DSS-induced colitis model and in an LPS-induced model in human colonic epithelial cells. They specifically focused on the effects of Diosmine on PANoptosis of intestinal epithelial cells, intestinal microflora, and fecal metabolites. They found that Diosmine significantly improved colitis symptoms, and histopathological analysis confirmed reduced inflammation and tissue damage in mice treated with Diosmine. Diosmine also suppressed the expression of genes and proteins associated with PANoptosis (ZBP1 and Caspase-1), preserving the integrity of the epithelial barrier in vitro. Furthermore, it altered the composition of the intestinal microbiota, promoting beneficial taxa such as Ruminococcus and reducing pathogenic Proteobacteria. These data suggest that Diosmine may be an essential therapeutic agent in patients with IBD, inhibiting PANoptosis of IECs, preserving intestinal barrier function, and modifying the intestinal microbiota [

31].

5. Therapeutic Synergy—Combination Therapies

The main challenge in existing IBD treatments, particularly with biologic agents (mainly anti-TNF-α agents), is primary or secondary non-response or loss of response. This failure is often associated with:

Non-Caspase-dependent Death: TNF-α inhibitors function in part by promoting apoptosis (Caspase-dependent). If cell damage leads to Necrosis (RIPK1/MLKL), then anti-TNF therapy becomes ineffective.

Uncontrolled Pyrolysis: Inflammation can be maintained by pyrolysis, which is not entirely blocked by targeting TNF-α and requires inhibition of the inflammasome (e.g., NLRP3/Caspase-1).

Panoptosis constitutes a multiple therapeutic target, and therefore, combination therapies are a field of increasing research. The strategy of combining a Panoptotic Inhibitor (e.g., Nec-1 or MCC950) with a Biological Agent (e.g., anti-TNF) provides a dual mechanistic advantage, as shown in

Table 4.

Table 4.

Suggested combinations of biological agent with PANoptosis inhibitors.

Table 4.

Suggested combinations of biological agent with PANoptosis inhibitors.

| Agent |

Main function |

Influence on IBD |

Combined |

| Advantage |

| |

|

|

|

| Anti-TNF (Infliximab) |

Cytokine inhibition (TNF-α) |

Reduction of systemic |

It acts on inflammation. |

| |

|

and local inflammation. |

|

| Necrostatin-1 (Nec-1) |

Inhibition RIPK1/Necrosis |

|

It addresses the cause (cell death) and prevents resistance. |

| Protection of the intestinal epithelium, interruption of the source of DAMPs. |

| MCC950 |

Inhibition NLRP3/Pyroptosis |

Reduction of IL-1β/IL-18, mucosal protection. |

It inhibits the inflammatory response caused by cell death. |

The combination appears promising i) in patients with refractory IBD, in whom the predominant pathology is cell necrosis, and ii) in cases with high inflammatory burden, where simultaneous targeting of inflammation and systemic inflammation (TNF-α) may lead to faster and deeper remission.

The proposed combinations involve anti-TNF + RIPK1 inhibitor, SMAC mimetic + inflammasome blockers, and small-molecule modulators specifically designed for gut-restricted targeting. (

Table 5).

Table 5.

Possible therapeutic synergies.

Table 5.

Possible therapeutic synergies.

| Combination |

Target |

Theoretic benefit |

| Anti-TNF + |

Apoptosis + |

Improving |

| RIPK1 inhibitor |

Necroptosis |

response |

| JAK inhibitor + |

Cytokines + |

Reducing resistance |

| inflammasome inhibitor |

Pyroptosis |

to treatment |

| IL-23 blocker + |

Innate + |

Reduction of mucosal |

| PANoptosis drug |

acquired immunity |

inflammation |

6. Discussion

Our basic knowledge of PANoptosis and its components, apoptosis, necroptosis, and pyroptosis, has increased and consolidated over the past ten years. A significant amount of data has helped clarify the roles of these cell death processes and their interactions in the pathogenesis of IBD. However, it is tough to fully understand the pathogenesis, since both UC and CD exhibit a heterogeneous population in the intestinal mucosa, which includes a multitude of specialized cells, from absorptive IECs and ileal cells to Tuft cells.

The importance of cell death in the intestine has recently been investigated in vivo using transgenic mouse models of experimental colitis, although the available literature is relatively limited. The study of PANoptosis in IBD will help develop innovative treatment strategies. Analysis of RIPK1 and Necrostatin-1 confirms that inhibition of the central regulatory proteins of RCD may offer a treatment that is not only anti-inflammatory, but also protective for the mucosa.

The most crucial development is the strategy of combination therapies [

32]. IBD is a multifactorial disease. Monotherapy, whether with biological agents that modulate cytokines, or with small molecules targeting a single cell death pathway, is likely to lead to the emergence of escape mechanisms. The combination of a PANoptosis inhibitor (which blocks the source of inflammation) with a cytokine inhibitor (which controls systemic inflammation) represents a synergistic approach that may lead to deeper remission, higher rates of mucosal healing, and overcoming resistance to existing biologics.

In the near future, clinical trials should focus on optimal dosing but primarily on potential toxicity. Systemic inhibition of RIPK1 may have unpredictable immunological effects, underscoring the need to develop gut-selective inhibitors as a top priority. The possible role of natural products in the prevention and treatment of IBD should not be overlooked, bearing in mind their minimal side effects.

7. Conclusions

PANoptosis is a highly promising new target for the treatment of IBD. Targeting central regulators, such as RIPK1 (with agents such as Necrostatin-1), has demonstrated the ability to protect the intestinal barrier in preclinical models. Furthermore, a combination strategy involving PANoptosis inhibitors (to address the cause of cell death) and established biologic agents (e.g., anti-TNF) (to control the cytokine storm) represents the most advanced therapeutic perspective. This approach is likely to lead to a new generation of therapies that will dramatically improve response rates and quality of life for patients with IBD.

References

- Triantafillidis JK, Stanciu C. Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Pathogenesis, Clinical manifestations, Diagnosis, Treatment. 1st Edition, TECHNOGRAMMAmed, 2012, Athens, Greece.

- Triantafillidis JK, Merikas E, Georgopoulos F. Current and emerging drugs for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2011;5:185-210. PMID: 21552489; PMCID: PMC3084301. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Li X, Yang M, Liu SB. Research progress on morphology and mechanism of programmed cell death. Cell Death Dis. 2024;15(5):327. PMID: 38729953; PMCID: PMC11087523. [CrossRef]

- Yuan J, Ofengeim D. A guide to cell death pathways. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2024;25(5):379-395. PMID: 38110635. [CrossRef]

- Qian S, Long Y, Tan G, Li X, Xiang B, Tao Y, Xie Z, Zhang X. Programmed cell death: molecular mechanisms, biological functions, diseases, and therapeutic targets. MedComm 2024;5(12):e70024. PMID: 39619229; PMCID: PMC11604731. [CrossRef]

- Newton K, Strasser A, Kayagaki N, Dixit VM. Cell death. Cell. (2024) 187:235–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2023.11.044.

- Li P ND, Budihardjo I, Srinivasula SM, Ahmad M, Alnemri ES, Wang X. Cytochrome C and datp-dependent formation of apaf-1caspase-9 complex initiates an apoptotic protease cascade. Cell 1997; 91:479–89. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80434-1.

- Akanyibah FA, Zhu Y, Jin T, Ocansey DKW, Mao F, Qiu W. The Function of Necroptosis and Its Treatment Target in IBD. Mediators Inflamm. 2024 Jul 31;2024:7275309. PMID: 39118979; PMCID: PMC11306684. [CrossRef]

- Samson AL, Zhang Y, Geoghegan ND, Gavin XJ, Davies KA, Mlodzianoski MJ, Whitehead LW, Frank D, Garnish SE, Fitzgibbon C, Hempel A, Young SN, Jacobsen AV, Cawthorne W, Petrie EJ, Faux MC, Shield-Artin K, Lalaoui N, Hildebrand JM, Silke J, Rogers KL, Lessene G, Hawkins ED, Murphy JM. MLKL trafficking and accumulation at the plasma membrane control the kinetics and threshold for necroptosis. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):3151. PMID: 32561730; PMCID: PMC7305196. [CrossRef]

- Patankar JV, Bubeck M, Acera MG, Becker C. Breaking bad: necroptosis in the pathogenesis of gastrointestinal diseases. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1203903. PMID: 37409125; PMCID: PMC10318896. [CrossRef]

- Tao S, Long X, Gong P, Yu X, Tian L. Phosphoproteomics Reveals Novel Insights into the Pathogenesis and Identifies New Therapeutic Kinase Targets of Ulcerative Colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2024;30(8):1367-1378. PMID: 38085663. [CrossRef]

- Newton K, Strasser A, Kayagaki N, Dixit VM. Cell death. Cell. (2024) 187:235–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2023.11.044.

- Zhang M, Zhao X, Cai T, Wang F. PANoptosis: potential new targets and therapeutic prospects in digestive diseases. Apoptosis. 2025 Sep 30. PMID: 41028409. [CrossRef]

- Zhao C, Lin S. PANoptosis in intestinal epithelium: its significance in inflammatory bowel disease and a potential novel therapeutic target for natural products. Front Immunol. 2025;15:1507065. PMID: 39840043; PMCID: PMC11747037. [CrossRef]

- Zhao J, Li Y, Ying P, Zhou Y, Xu Z, Wang D, Wang H, Tang L. ITLN1 exacerbates Crohn’s colitis by driving ZBP1-dependent PANoptosis in intestinal epithelial cells through antagonizing TRIM8-mediated CAPN2 ubiquitination. Int J Biol Sci. 2025;21(8):3705-3725. PMID: 40520022; PMCID: PMC12160931. [CrossRef]

- Zhang M, Liu T, Luo L, Xie Y, Wang F. Biological characteristics, immune infiltration and drug prediction of PANoptosis related genes and possible regulatory mechanisms in inflammatory bowel disease. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):2033. PMID: 39814753; PMCID: PMC11736032. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Yin X, Zheng S, Zhao Y, Zhong X. The PAR-score based on PANoptosis genes predicts the progression of ulcerative colitis and the response to anti-TNF-α treatment. Genes Genomics. 2025;47(10):1079-1097. PMID: 40932643. [CrossRef]

- Yang Y, Hounye AH, Chen Y, Liu Z, Shi G, Xiao Y. Characterization of PANoptosis-related genes in Crohn’s disease by integrated bioinformatics, machine learning and experiments. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):11731. PMID: 38778086; PMCID: PMC11111690. [CrossRef]

- Lee C, Kim JE, Cha YE, Moon JH, Kim ER, Chang DK, Kim YH, Hong SN. IFN-γ-Induced intestinal epithelial cell-type-specific programmed cell death: PANoptosis and its modulation in Crohn’s disease. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1523984. PMID: 40230837; PMCID: PMC11994596. [CrossRef]

- Pandeya A, Kanneganti TD. Therapeutic potential of PANoptosis: innate sensors, inflammasomes, and RIPKs in PANoptosomes. Trends Mol Med. 2024;30(1):74-88. PMID: 37977994; PMCID: PMC10842719. [CrossRef]

- Bynigeri RR, Malireddi RKS, Mall R, Connelly JP, Pruett-Miller SM, Kanneganti TD. The protein phosphatase PP6 promotes RIPK1-dependent PANoptosis. BMC Biol. 2024;22(1):122. PMID: 38807188; PMCID: PMC11134900. [CrossRef]

- Liu C, Wang H, Han L, Zhu Y, Ni S, Zhi J, Yang X, Zhi J, Sheng T, Li H, Hu Q. Targeting P2Y14R protects against necroptosis of intestinal epithelial cells through PKA/CREB/RIPK1 axis in ulcerative colitis. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):2083. PMID: 38453952; PMCID: PMC10920779. [CrossRef]

- Lu H, Li H, Fan C, Qi Q, Yan Y, Wu Y, Feng C, Wu B, Gao Y, Zuo J, Tang W. RIPK1 inhibitor ameliorates colitis by directly maintaining intestinal barrier homeostasis and regulating following IECs-immuno crosstalk. Biochem Pharmacol. 2020;172:113751. PMID: 31837309. [CrossRef]

- Weisel K, Scott N, Berger S, Wang S, Brown K, Powell M, Broer M, Watts C, Tompson DJ, Burriss SW, Hawkins S, Abbott-Banner K, Tak PP. A randomised, placebo-controlled study of RIPK1 inhibitor GSK2982772 in patients with active ulcerative colitis. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2021;8(1):e000680. PMID: 34389633; PMCID: PMC8365785. [CrossRef]

- Chen L, Zheng X, Li J, Zhou B, Tao M, Yang Y, Wang Y, Zhan H, Zhang G, Shi J, Zhang X, Ruan B. Discovery of (E)-1,3-Diphenyl-2-Propen-1-One Derivatives as Potent and Orally Active NLRP3 Inflammasome Inhibitors for Colitis. Molecules. 2025;30(16):3340. PMID: 40871494; PMCID: PMC12388496. [CrossRef]

- Masoud A, Akbari M, Jamal Ashini L, Adelnia R, Khodabandeh Shahraki P, Ramezani Ahmadi A, Panahi A. The effects of MCC950 on NLRP3 inflammasome and inflammatory biomarkers: a systematic review and meta-analysis on animal studies. Immunopathol Persa. 2025;11(2):e43847. [CrossRef]

- Akanyibah FA, He C, Wang X, Wang B, Mao F. The role of plant-based dietary compounds in gut microbiota modulation in inflammatory bowel disease. Front Nutr. 2025;12:1606289. PMID: 40521353; PMCID: PMC12163340. [CrossRef]

- Gong W, Liu Z, Wang Y, Huang W, Yang K, Gao Z, Guo K, Xiao Z, Zhao W. Reprogramming of Treg cell-derived small extracellular vesicles effectively prevents intestinal inflammation from PANoptosis by blocking mitochondrial oxidative stress. Trends Biotechnol. 2025;43(4):893-917. PMID: 39689981. [CrossRef]

- Wang M, Wang Z, Li Z, Qu Y, Zhao J, Wang L, Zhou X, Xu Z, Zhang D, Jiang P, Fan B, Liu Y. Targeting programmed cell death in inflammatory bowel disease through natural products: New insights from molecular mechanisms to targeted therapies. Phytother Res. 2025;39(4):1776-1807. PMID: 38706097. [CrossRef]

- Ye Z, Deng M, Yang Y, Song Y, Weng L, Qi W, Ding P, Huang Y, Yu C, Wang Y, Wu Y, Zhang Y, Yuan S, Nie W, Zhang L, Zeng C. Epithelial mitochondrial fission-mediated PANoptosis is crucial for ulcerative colitis and its inhibition by saquinavir through Drp1. Pharmacol Res. 2024;210:107538. PMID: 39643069. [CrossRef]

- Tan C, Xiang Z, Wang S, He H, Li X, Xu M, Guo X, Pu Y, Zhen J, Dong W. Diosmin alleviates colitis by inhibiting PANoptosis of intestinal epithelial cells and regulating gut microbiota and metabolites. Phytomedicine. 2025;141:156671. PMID: 40138774. [CrossRef]

- Triantafillidis JK, Zografos CG, Konstadoulakis MM, Papalois AE. Combination treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: Present status and future perspectives. World J Gastroenterol. 2024;30(15):2068-2080. PMID: 38681984; PMCID: PMC11045479. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).