1. Introduction

Anatomic pathology provides definitive histopathological assessments essential for disease classification, prognostic stratification, and treatment planning across oncology, infectious diseases, and inflammatory conditions [

1,

2]. Cancer accounts for approximately 10 million deaths annually worldwide, with anatomopathological diagnosis serving as the reference standard for tumor classification according to WHO criteria [

3]. Contemporary pathology workflows generate substantial volumes of narrative reports documenting macroscopic descriptions, microscopic findings, and diagnostic impressions that are integrated into Electronic Medical Records [

4,

5]. These textual data support clinical decision-making, quality assurance, epidemiological surveillance, and retrospective research initiatives across healthcare institutions [

6,

7]. However, the predominance of unstructured free-text formats creates substantial barriers to automated information extraction, semantic interoperability, and large-scale computational analysis [

8,

9].

The transformation of unstructured clinical narratives into structured, standardized data representations requires sophisticated natural language processing approaches capable of medical domain adaptation [

10,

11]. Named Entity Recognition has emerged as a foundational technique for identifying clinical concepts within free text, with transformer-based architectures demonstrating substantial performance gains over traditional rule-based and statistical methods [

12,

13]. BioBERT introduced domain-specific pre-training on PubMed abstracts and PMC full-text articles, achieving state-of-the-art results across multiple biomedical named-entity recognition benchmarks, including disease mentions, chemical compounds, and gene identifiers [

14]. Subsequent models, including ClinicalBERT and BioClinicalBERT, incorporated clinical notes from the MIMIC-III database, further improving performance on clinical entity extraction tasks [

15,

16]. These transformer architectures use self-attention mechanisms to capture long-range contextual dependencies and semantic relationships, which are essential for disambiguating medical terminology [

17].

Beyond entity extraction, normalization to standard medical terminologies represents an equally critical challenge for achieving semantic interoperability across healthcare systems [

18,

19]. The Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine Clinical Terms provides comprehensive coverage with over 350,000 active concepts spanning clinical findings, procedures, body structures, and organisms [

20]. The Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes standardizes laboratory test nomenclature with approximately 95,000 terms, facilitating data exchange across laboratory information systems [

21]. The International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision offers a modernized coding framework supporting epidemiological reporting, clinical documentation, and healthcare resource allocation [

22]. However, mapping free-text clinical entities to these standardized terminologies requires sophisticated approaches capable of handling synonymy, abbreviations, contextual variations, and hierarchical concept relationships [

23,

24]. Recent research has explored metric learning, retrieval-based methods, and graph neural networks for entity linking tasks, with varied results depending on the complexity of the terminology and the availability of training data [

25,

26]. Retrieval-Augmented Generation has emerged as a promising paradigm that grounds language model predictions in external knowledge bases through dense vector retrieval, demonstrating improvements in factual accuracy and domain-specific question answering [

27,

28].

Despite these advances, several research gaps persist in automated pathology report processing. First, most existing studies focus on English-language clinical texts, with limited validation on non-English pathology reports from diverse geographic regions [

29]. Second, multi-ontology mapping approaches typically evaluate performance on individual terminologies rather than simultaneous mapping to SNOMED CT, LOINC, and ICD-11 within unified frameworks [

30]. Third, the integration of retrieval-augmented approaches with supervised classification for medical entity normalization remains underexplored compared to standalone architectures [

31]. Finally, rigorous statistical validation, including effect size reporting, confidence interval estimation, and inter-model comparison testing, is often absent from published studies [

32].

Based on the identified research gaps, our study aimed to (i) develop and validate a BioBERT-based Named Entity Recognition model for extracting sample type, test performed, and finding entities from anatomopathological reports; (ii) implement a hybrid standardization framework combining BioClinicalBERT multi-label classification with dense retrieval-augmented generation for simultaneous mapping to SNOMED CT, LOINC, and ICD-11 terminologies; and (iii) conduct a comprehensive performance evaluation with rigorous statistical testing, including bootstrap confidence intervals, agreement measures, and inter-model comparisons on real-world clinical data.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

This retrospective study received approval from the Ethics Committee of the Military Hospital of Tunis (decision number 116/2025/CLPP/Hôpital Militaire de Tunis) on July 7, 2025, before data collection and analysis. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patient information was rigorously anonymized to ensure confidentiality and privacy protection. Data handling and analysis were undertaken solely by anatomical pathologists involved in the study, ensuring strict adherence to ethical standards and institutional guidelines.

2.2. Data Collection and Corpus Development

We collected 560 anatomopathological reports retrospectively from the information system of the Main Military Teaching Hospital of Tunis between January 2020 and December 2023. Each report corresponded to a unique patient case and was manually annotated by board-certified anatomopathologists. Standard preprocessing included removing uninformative headers and footers, de-identifying sensitive personal data, and correcting only typographical errors to achieve complete anonymization. The annotation process identified three primary entity types: sample type (tissue specimens submitted for examination), test performed (histological techniques and staining methods), and finding (diagnostic observations and pathological descriptions). Manual assignment of reference codes from SNOMED CT, LOINC, and ICD-11 terminologies was performed using official terminology resources obtained from

https://www.snomed.org, https://loinc.org, and

https://icd.who.int.

2.3. External Knowledge Base Construction

For the Retrieval-Augmented Generation component, we constructed an external knowledge base by downloading official terminology files in Excel and CSV formats from SNOMED CT, LOINC, and ICD-11 websites. These resources contained clinical concepts with corresponding standardized codes, descriptive labels, and hierarchical relationships. The terminology databases were integrated and indexed using dense vector embeddings to support semantic similarity retrieval during inference.

2.4. Named Entity Recognition Model

We implemented BioBERT v1.1 from dmis-lab/biobert-v1.1 for token-level entity classification [

14]. Reports were preprocessed and converted to JSON format with sentence-level segmentation. The BioBERT tokenizer applied WordPiece subword tokenization, with token labels aligned to subwords using word_ids() mapping. Filler tokens and unaligned tokens were masked using -100 label identifiers. The architecture consisted of bidirectional transformer layers generating contextualized feature vectors for each token position. Self-attention mechanisms captured contextual dependencies across sequences according to the formulation [

13]:

where

represent query, key, and value matrices, and

denotes key vector dimensionality. A fully connected classification layer mapped contextualized embeddings to entity type predictions through softmax activation:

where

represents the logit score for class

. Model training optimized cross-entropy loss:

where

denotes accurate labels and

represents predicted probabilities.

2.5. Training Configuration for Named Entity Recognition

BioBERT v1.1 was fine-tuned for three epochs using the AdamW optimizer with a learning rate of 2×10⁻⁵, weight decay of 0.01, and a batch size of 8 for both training and evaluation phases [

33]. Cross-entropy loss with ignored labels set to -100 guided optimization. Data were split into 80% for training and 20% for testing. Training was conducted using the HuggingFace Trainer API on NVIDIA GPU infrastructure. Evaluation metrics included token-level precision, recall, and F1-score calculated separately for each entity class.

2.6. Entity Standardization Architecture

The standardization pipeline integrated supervised classification and semantic retrieval components. BioClinicalBERT from emilyalsentzer/Bio_ClinicalBERT encoded extracted entity mentions into dense representations, projecting them into the model’s latent space [

16]. A multi-label classification head produced probability distributions over target code spaces for SNOMED CT, LOINC, and ICD-11 terminologies. The top-k candidates with the highest probabilities were extracted from classification outputs.

2.7. Retrieval-Augmented Generation Module

For retrieval augmentation, we encoded all terminology concepts from SNOMED CT, LOINC, and ICD-11 databases using BioClinicalBERT to generate dense vector representations. During inference, query entity embeddings were compared with the indexed terminology vectors using cosine similarity. The nearest-neighbor concepts were retrieved as candidate codes from the external knowledge base via dense passage retrieval [

27].

2.8. Fusion and Reranking Strategy

The final standardization decision combined outputs from BioClinicalBERT classification and retrieval modules through a learned fusion mechanism. A weighted decision rule was optimized via 5-fold cross-validation, determining whether to select the classifier’s prediction or the retrieved concept. When classification and retrieval outputs disagreed, the system applied learned weights to prioritize the more reliable component. As a fallback mechanism, retrieval-based predictions overrode classifier errors when classification confidence was below threshold values. This approach balanced discriminative accuracy from supervised learning with semantic robustness from knowledge base retrieval.

2.9. Training Configuration for Standardization

BioClinicalBERT was trained using the AdamW optimizer with cross-entropy loss on the annotated dataset for 10 epochs, with early stopping based on validation loss. The Retrieval-Augmented Generation component operated only during inference, retrieving the closest terminology codes based on cosine similarity scores. The fusion module combined predictions from trained BioClinicalBERT and reference RAG using weighted scoring, with optimal weights determined through cross-validation on the training set. Final predictions for SNOMED CT, LOINC, and ICD-11 codes were generated through the integrated fusion architecture.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

Performance evaluation employed precision (positive predictive value), recall (sensitivity), and F1-score (harmonic mean of precision and recall), calculated separately for each entity type and terminology. Bootstrap resampling with 10,000 iterations estimated 95% confidence intervals for performance metrics [

34]. One-sample t-tests assessed whether model performance significantly exceeded a baseline threshold of 0.5. Cohen’s Kappa and Matthews Correlation Coefficient quantified agreement between predictions and ground-truth annotations, accounting for chance agreement [

35]. McNemar’s test evaluated prediction discordance between model pairs [

36]. Permutation tests with 10,000 iterations assessed whether observed differences in accuracy between models could be due to chance. All statistical analyses were conducted using Python scientific computing libraries (NumPy, SciPy, scikit-learn) on the held-out test set.

3. Results

3.1. Named Entity Recognition Performance by Entity Type

The BioBERT model achieved strong performance across all clinical entity types on the test set.

Table 1 presents the performance metrics organized by entity type, with an overall mean precision of 0.969, recall of 0.958, and F1-score of 0.963. Sample type entities achieved a precision of 0.97, a recall of 0.98, and an F1-score of 0.97. Test performed entities demonstrated precision of 0.97, recall of 0.99, and F1-score of 0.98. Finding entities achieved a precision of 0.97, a recall of 0.90, and an F1-score of 0.93, with slightly lower recall indicating challenges in detecting certain instances in this more variable category.

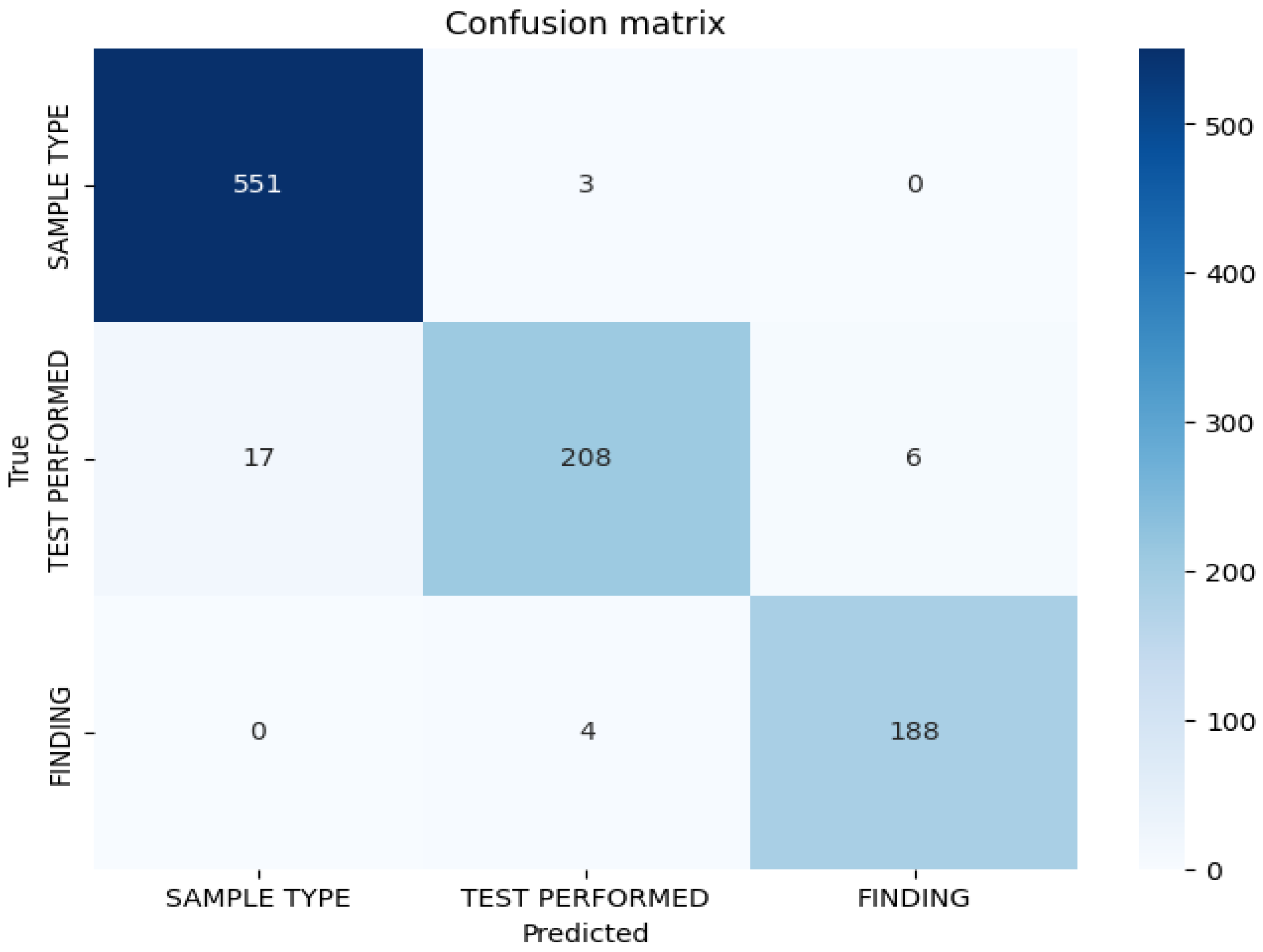

3.2. Confusion Matrix Analysis

Figure 1 represents the confusion matrix displaying token-level classification results for the BioBERT model on the test set. The matrix demonstrates strong discrimination between entity classes, with minimal misclassification. The diagonal elements indicate correct classifications for each entity type, while the off-diagonal elements indicate misclassifications. Misclassification patterns reveal that errors are primarily concentrated in the test-performed entity category, suggesting lexical or contextual ambiguities in procedural nomenclature descriptions in anatomopathological reports. The confusion matrix confirms low cross-category confusion, indicating that the model effectively learns semantic distinctions between sample types, performed tests, and diagnostic findings.

3.3. Error Analysis by Entity Type

Table 2 represents the absolute and relative errors per entity for the BioBERT model. Absolute error counts revealed 45 misclassified tokens for test performed entities, corresponding to a relative error rate of 6.9%. Finding entities demonstrated very low absolute errors of 6 tokens with a relative error rate of 1%, indicating that diagnostic finding expressions are relatively homogeneous and easily identifiable within the corpus. Sample type entities exhibited intermediate error patterns. The variety of expressions and abbreviations used to describe anatomical specimens and histological procedures contributes to classification challenges, particularly for test-performed entities, where standardized terminology coexists with institutional variations and procedural synonyms.

3.4. Confidence Intervals for Performance Metrics

Bootstrap estimation with 10,000 samples generated 95% confidence intervals confirming robust performance stability, as presented in

Table 3. Precision demonstrated narrow confidence intervals (95% CI: 0.967-0.970), indicating high stability for this metric across bootstrap resampling iterations. Recall exhibited slightly wider confidence intervals (95% CI: 0.900-0.995), reflecting variability in detecting certain entity instances, particularly for finding entities. F1-score confidence intervals (95% CI: 0.933-0.982) showed intermediate width, balancing the stability of precision with the variability of recall measurements. The narrow intervals overall confirm that observed performance represents stable model behavior rather than stochastic variation or overfitting to the particular test set composition.

3.5. Statistical Significance Testing Against Baseline

One-sample t-tests comparing model metrics against a baseline of 0.5 yielded extremely high t-statistics as shown in

Table 4, with all p-values below 0.001. The t-statistics for precision, recall, and F1-score were 19.17, 18.30, and 39.00, respectively, confirming that the observed performance significantly exceeded baseline thresholds with very high confidence. The exceptionally high t-statistic for the F1-score was driven by both high mean performance and low variance across the three entity types. The very low p-values confirm that all model metrics significantly exceed the 0.5 baseline, indicating that observed performance is not due to chance. The t-statistic for precision, while very high, reflects the small entity sample size (n=3), which amplifies test statistics when variance is low. Recall and F1-score t-values remained elevated, with magnitudes more intuitive, reflecting slightly greater variability in these metrics across entities.

3.6. Descriptive Statistics Across Entity Labels

Table 5 represents metric statistics by label, revealing consistent high performance across all entity types. A mean precision of 0.969 and a standard deviation of 0.001 demonstrate minimal variability in positive predictive value across entity classes. A mean recall of 0.958 with a standard deviation of 0.050 indicates slightly higher variability, suggesting that certain entities, such as finding present, pose greater detection challenges due to lexical diversity and contextual variation in diagnostic descriptions. Mean F1-score of 0.963 with a standard deviation of 0.027 confirms balanced performance between precision and recall. The low standard deviations indicate that the model consistently achieves high performance across all labels, with stable precision and F1-scores throughout the entity taxonomy.

3.7. Multi-Ontology Standardization Descriptive Performance

Table 6 presents the descriptive performance metrics for the BioClinicalBERT, RAG, and Fusion/Reranker models across SNOMED CT, LOINC, and ICD-11 classification tasks, evaluated on 53 test samples. For SNOMED CT code mapping, BioClinicalBERT achieved an accuracy of 0.7547, a precision of 0.5881, a recall of 0.6667, and an F1-macro of 0.6124. RAG demonstrated intermediate performance with an accuracy of 0.6981 and an F1-macro of 0.5856. Fusion/Reranker achieved the highest performance with an accuracy of 0.7925, a precision of 0.6136, and an F1-macro of 0.6159. For LOINC classification, performance was substantially higher across all models, with Fusion/Reranker achieving an accuracy of 0.9811, precision of 0.9216, recall of 0.9412, and F1-macro of 0.9294. BioClinicalBERT showed an accuracy of 0.9434 and an F1-macro of 0.8445. ICD-11 mapping exhibited intermediate performance, with Fusion/Reranker achieving accuracy of 0.8491, precision of 0.7115, recall of 0.7500, and F1-macro of 0.7201, compared to BioClinicalBERT’s accuracy of 0.7925 and F1-macro of 0.6772. These results demonstrate consistent descriptive superiority of the Fusion/Reranker architecture across all three terminologies.

3.8. Agreement Measures for Model Predictions

Table 7 represents Cohen’s Kappa and Matthews Correlation Coefficient values quantifying agreement between model predictions and ground-truth annotations for all model-task combinations. For SNOMED CT mapping, Fusion/Reranker demonstrated Cohen’s Kappa of 0.7829 and MCC of 0.7885, indicating strong agreement according to standard interpretation guidelines [

35]. BioClinicalBERT showed a Kappa of 0.7423 and an MCC of 0.7511, while RAG exhibited lower agreement with a Kappa of 0.6871. For LOINC classification, Fusion/Reranker achieved near-perfect agreement, with Cohen’s Kappa of 0.9773 and MCC of 0.9777, the highest concordance across all tasks. BioClinicalBERT demonstrated a Kappa of 0.9318 and an MCC of 0.9338. For ICD-11 mapping, Fusion/Reranker showed moderate to substantial agreement (Kappa = 0.8435, MCC = 0.8457), while BioClinicalBERT achieved a Kappa of 0.7840. These agreement measures confirm that Fusion/Reranker consistently shows stronger concordance with expert annotations than standalone classification or retrieval approaches.

3.9. Statistical Comparison Between Model Architectures

Table 8 represents statistical comparison results between BioClinicalBERT and Fusion/Reranker models using McNemar’s test and permutation testing across all terminology mapping tasks. For SNOMED CT, McNemar’s test yielded a p-value of 0.500 with an accuracy difference of 0.0378 and a permutation p-value of 0.4911. LOINC comparison showed a McNemar p-value of 0.625, an accuracy difference of 0.0377, and a permutation p-value of 0.6171. ICD-11 mapping demonstrated a McNemar p-value of 0.375, an accuracy difference of 0.0566, and a permutation p-value of 0.3721. All McNemar p-values exceeded 0.370, indicating insufficient discordant predictions to conclude statistical superiority of either model [

36]. Permutation test p-values ranging from 0.372 to 0.617 suggest that observed accuracy differences are consistent with random variation, given the test set size of 53 samples. Therefore, although Fusion/Reranker demonstrates higher performance across all tasks, with consistent improvements in accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-scores, these improvements cannot be considered statistically significant given the current sample size.

4. Discussion

This study developed and validated a hybrid pipeline integrating BioBERT for Named Entity Recognition with BioClinicalBERT and Retrieval-Augmented Generation to standardize anatomopathological reports across multiple ontologies. The system achieved F1-scores exceeding 0.93 for entity extraction and demonstrated substantial to near-perfect agreement for terminology mapping across SNOMED CT, LOINC, and ICD-11. These results confirm the technical feasibility of automated clinical entity extraction and standardization. However, statistical testing revealed that augmentation benefits did not achieve significance at conventional thresholds given the current sample size.

4.1. BioBERT Performance for Named Entity Recognition

Our BioBERT model achieved a mean F1-score of 0.963 across sample type (F1 = 0.97), test performed (F1 = 0.98), and finding (F1 = 0.93) entities, substantially exceeding baseline performance thresholds. These results surpass the performance reported by Nath et al., who achieved F1-scores between 0.808 and 0.894 using BiLSTM-CRF architectures on i2b2 clinical datasets [

37]. The substantial performance advantage demonstrates that transformer-based self-attention mechanisms capture long-range contextual dependencies more effectively than sequential recurrent architectures. Similarly, our results exceed the BioBERT performance reported by Lee et al., who achieved a maximum F1 of 0.898 on biomedical entity recognition benchmarks [

14]. The higher performance in our study likely reflects task-specific fine-tuning on anatomopathological domain vocabulary, where consistent terminology usage and standardized report structures facilitate entity boundary detection. Our precision of 0.969 and recall of 0.958 exceed the ranges of 0.84 to 0.87 reported for SciBERT and BlueBERT variants [

38], indicating that BioBERT pre-training on PubMed abstracts provides particularly effective initialization for medical entity extraction tasks. The test performed entity achieved the highest F1-score of 0.98, suggesting that standardized histological technique nomenclature exhibits less lexical variability than finding entities. The extremely high t-statistic of 19.17 for precision, with p<0.001, confirms statistical significance, though the magnitude reflects the small sample size (n=3), amplifying the test statistic. This suggests that procedural terminology benefits from greater standardization across pathology practice than diagnostic descriptions, which exhibit greater contextual variation and require deeper semantic understanding for accurate extraction.

4.2. Error Patterns and Entity Complexity

Error analysis revealed distinct patterns across entity types, with the test performed exhibiting the highest relative error rate of 6.9% despite achieving the second-highest F1-score. This apparent contradiction reflects the large absolute token count for test-performed entities, where 45 misclassifications among 655 total tokens yield moderate error rates while maintaining high overall accuracy. The variety of expressions, abbreviations, and contextual descriptions for histological procedures creates disambiguation challenges that occasionally confuse the classification system. Common error sources included abbreviated technique names (e.g., “H&E” versus “hematoxylin and eosin”), procedural variations (e.g., “immunohistochemistry” versus “immunostaining”), and compound procedures described as single entities. In contrast, entity identification demonstrated the lowest relative error of 1% with only six misclassifications, indicating that diagnostic terminology follows more consistent patterns within anatomopathological reports. Sample type entities showed intermediate error characteristics, balancing the standardization of anatomical terminology with variations in specimen preparation. The confusion matrix analysis revealed that most errors involved adjacent entity boundaries rather than complete entity category confusion, suggesting that the model effectively learns semantic distinctions but occasionally struggles with precise boundary identification in complex multi-word expressions. For example, phrases like “lymph node biopsy specimen” occasionally resulted in boundary errors between the sample type and the test performed entities. These error patterns align with observations from clinical NER studies showing that procedural and diagnostic concepts exhibit different linguistic regularities [

37,

39]. The bootstrap confidence intervals confirm that these performance patterns represent stable model characteristics rather than artifacts of particular test set composition.

4.3. Dataset Characteristics and Generalizability Considerations

While our focused corpus of 560 reports enabled high within-domain performance, several factors warrant consideration regarding generalizability. First, the dataset derives from a single institution, potentially with homogeneous reporting practices, terminology preferences, and pathologist writing styles. Multi-institutional studies have demonstrated that NER performance can decrease by 5-15% when models are applied to external datasets without retraining [

40]. Our French-language corpus may limit direct applicability to other languages, though recent work on multilingual biomedical models suggests that cross-lingual transfer learning can partially mitigate this limitation [

41]. Second, anatomopathological reports exhibit a more standardized structure compared to other clinical note types, such as emergency department records or physician progress notes, potentially making our task somewhat easier than general clinical NER [

42]. The finding entity demonstrated lower recall (0.958) than other entity types, likely reflecting greater semantic diversity in diagnostic descriptions than in standardized specimen types and procedural nomenclature. This performance pattern aligns with findings from clinical entity recognition studies, which show that diagnostic concepts exhibit more variable expression than laboratory tests or anatomical structures [

39]. Third, our corpus emphasizes general anatomic pathology cases, potentially under-representing rare diagnoses, complex syndromic presentations, or specialized pathology domains such as neuropathology or forensic pathology. External validation across multi-institutional datasets with diverse pathology subspecialties would provide a more robust assessment of generalizability. The narrow confidence intervals for precision suggest that positive predictive value remains stable across bootstrap samples, while wider recall intervals indicate greater sensitivity to corpus composition.

4.4. Multi-Ontology Code Mapping Performance

Our Fusion/Reranker architecture achieved an F1-macro of 0.7201 for ICD-11 mapping, substantially exceeding previously reported performance. Bhutto et al. achieved a macro-F1 of only 0.655 using deep recurrent convolutional neural networks with scaled attention on MIMIC-III ICD-10 coding tasks [

43]. Chen et al. reported macro-F1 around 0.701 using BioBERT and XLNet embeddings with rule-based approaches for ICD-10-CM coding [

44]. Our superior performance, despite ICD-11’s larger label space (approximately 55,000 codes versus 14,000 in ICD-10-CM) and finer granularity, indicates that the combination of supervised classification with dense retrieval provides a more robust approach to handling rare codes and unseen concept variations than classification-only approaches. The retrieval component acts as a semantic buffer, allowing the system to map entities to terminology concepts even when training examples were sparse or absent. This addresses the fundamental challenge of medical code prediction: extreme class imbalance, where a small number of codes account for the majority of cases. In contrast, thousands of rare codes appear infrequently [

45]. LOINC mapping achieved an exceptionally high F1-macro of 0.9294 with Cohen’s Kappa of 0.9773, indicating near-perfect agreement. This strong performance likely reflects the more constrained vocabulary space of laboratory test nomenclature compared to the broader concept coverage of SNOMED CT and ICD-11 [

21]. Laboratory tests follow standardized naming conventions with limited synonymy, facilitating accurate code assignment through both classification and retrieval mechanisms. Additionally, our corpus likely contained fewer distinct LOINC codes than SNOMED CT or ICD-11, thereby reducing the complexity of the classification task. SNOMED CT mapping achieved a moderate F1-macro of 0.6159 with Cohen’s Kappa of 0.7829, suggesting challenges in handling the extensive concept hierarchy and semantic relationships within this comprehensive terminology [

20]. The discrepancy between Cohen’s Kappa and F1-macro likely reflects class imbalance effects, where frequent concepts achieve high accuracy while rare concepts contribute disproportionately to F1-macro calculations. The Matthews Correlation Coefficient of 0.7885 for SNOMED CT confirms substantial predictive quality when accounting for all confusion matrix elements, including true negatives, which are typically abundant in multi-class problems with many infrequent classes.

4.5. Statistical Significance and Sample Size Considerations

McNemar’s tests yielded p-values exceeding 0.370 across all standardization tasks. In contrast, permutation tests yielded p-values ranging from 0.375 to 0.625, indicating that the observed performance improvements for Fusion/Reranker did not achieve statistical significance at the conventional α = 0.05 threshold. This finding reflects the limited sample size of 53 test instances, which provides insufficient statistical power to detect moderate effect sizes. Post-hoc power analysis suggests that detecting a 5% accuracy difference with 80% power at α = 0.05 would require approximately 200-250 test samples, given the observed variance [

46]. The higher descriptive performance of Fusion/Reranker across all metrics suggests potential clinical utility, despite the lack of statistical significance. For SNOMED CT, the accuracy improvement of 0.0378 (3.78 percentage points) represents meaningful gains when extrapolated to large-scale coding operations processing thousands of reports monthly. A hospital processing 500 pathology reports daily would see approximately 9-10 additional correctly coded reports per day with the Fusion/Reranker architecture. Cohen’s Kappa values demonstrated substantial to near-perfect agreement for all models, with Fusion/Reranker consistently achieving higher agreement levels. The practical implications of these findings suggest that retrieval augmentation provides measurable performance gains that may translate to clinical value, though larger validation studies are required for definitive conclusions. The permutation test framework provides a more appropriate significance assessment than parametric tests, given the small sample size and potentially non-normal distribution of accuracy. The permutation approach makes minimal distributional assumptions and provides exact p-values under the null hypothesis of no difference between models.

4.6. Retrieval-Augmented Generation Integration

The integration of dense retrieval with supervised classification represents a hybrid approach that combines complementary strengths of both paradigms. Supervised classification effectively learns discriminative patterns from labeled training data, achieving high accuracy for frequent entity-code pairs with abundant training examples [

47]. The classifier learns to recognize linguistic patterns associated with specific codes, such as associating “adenocarcinoma” mentions with particular ICD-11 oncology codes. However, classification performance degrades for rare codes with few training instances (e.g., those that appear only once or twice) and fails for unseen concepts absent from the training data. This limitation is particularly problematic in medical coding, where Zipfian distributions mean that many codes are extremely rare [

45]. Retrieval-augmented generation addresses these limitations by grounding predictions in external knowledge bases that provide comprehensive coverage of terminology [

27,

28]. The semantic similarity search enables mapping to appropriate codes even when exact training examples are unavailable, thereby improving robustness to the long-tail distributions characteristic of medical terminologies. For instance, if the training set lacked examples of a specific rare tumor subtype, the retrieval component could still identify the correct code by matching the entity description to similar concepts in the terminology database. Recent studies in biomedical question answering and clinical reasoning tasks have demonstrated that retrieval-augmented approaches improve factual accuracy and reduce hallucination compared to generation-only systems [

48]. Our fusion mechanism learned to balance classification confidence with retrieval similarity through cross-validation, optimizing the trade-off between discriminative accuracy and semantic robustness. The learned weights effectively route decisions to the more reliable component depending on input characteristics, entity types, and terminology structures. For LOINC, the classification component demonstrated sufficient accuracy that retrieval provided minimal additional benefit, reflected in the small performance gap between BioClinicalBERT and Fusion/Reranker (F1-macro difference of 0.037). In contrast, for ICD-11 with its larger label space and greater semantic complexity, retrieval augmentation provided more substantial improvements (F1-macro difference of 0.037) by retrieving appropriate codes for rare diagnostic concepts where training examples were sparse.

4.7. Agreement Measures Interpretation

Cohen’s Kappa and Matthews Correlation Coefficient provide complementary perspectives on model-annotation agreement by accounting for chance concordance and imbalanced class distributions [

35]. For LOINC, the near-perfect Kappa of 0.9773 and MCC of 0.9777 indicate that the model achieves agreement levels approaching human-level performance on this structured laboratory test nomenclature. Inter-annotator agreement studies for LOINC coding typically report Kappa values between 0.85 and 0.98 [

49], suggesting our automated system performs comparably to human coders. The slight discrepancy between Kappa and MCC reflects different weighting schemes for confusion matrix elements, with MCC providing a balanced measure across all prediction categories, including true negatives. For SNOMED CT, the substantial Kappa of 0.7829 indicates strong agreement despite a moderate F1-macro of 0.6159, reflecting the impact of frequent concept classes achieving high accuracy. In contrast, rare concepts contribute disproportionately to F1-macro calculations. This pattern is common in imbalanced classification tasks where accuracy can be high (94.34% for Fusion/Reranker) while macro-averaged metrics remain moderate due to poor performance on infrequent classes. The ICD-11 Kappa of 0.8435 represents moderate to substantial agreement according to standard interpretation guidelines [

35], indicating clinically useful performance that nevertheless requires human verification for quality assurance. Inter-annotator agreement for ICD-11 coding typically ranges from 0.60 to 0.85, depending on code granularity and specialty domain [

50], suggesting our automated system performs within the range of human coder variability. The consistency of agreement patterns across BioClinicalBERT, RAG, and Fusion/Reranker confirms that different architectural approaches achieve similar levels of concordance, with hybrid fusion providing incremental improvements. These agreement measures provide more clinically interpretable performance assessment than raw accuracy, particularly for imbalanced medical coding tasks, where the majority-class prediction can achieve superficially high accuracy while failing to capture rare diagnostic concepts.

4.8. Clinical Implications and Deployment Considerations

Automated extraction and standardization of anatomopathological entities provide multiple clinical benefits, including improved data quality, enhanced interoperability, accelerated research capabilities, and reduced manual coding burden [

51]. Standardized terminologies enable semantic queries across institutional databases, supporting comparative effectiveness research, epidemiological surveillance, and clinical decision support systems [

52]. The high LOINC mapping accuracy facilitates the integration of laboratory tests with electronic health records, enabling automated result retrieval and longitudinal tracking of specific biomarkers or tumor markers across patient encounters. ICD-11 standardization supports epidemiological reporting to public health agencies and allows accurate quantification of disease burden for healthcare resource allocation decisions [

22]. SNOMED CT mapping provides a granular representation of clinical concepts, supporting interoperability between heterogeneous healthcare information systems [

20]. However, several considerations must be addressed before clinical deployment. First, model outputs require validation by qualified pathologists before incorporation into official medical records, as coding errors could impact clinical decisions, billing accuracy, reimbursement, and quality metrics used for hospital performance evaluation. A graduated deployment approach could begin with high-confidence predictions (e.g., model confidence > 0.95) receiving automatic approval, while uncertain cases are routed to manual review. Second, ongoing model monitoring is essential to detect performance degradation when encountering evolving terminology, novel pathology entities, or shifting documentation practices. Concept drift in medical language occurs as new diagnostic techniques emerge and terminology evolves [

53]. Third, transparency mechanisms such as confidence scores, retrieval evidence, and explanation interfaces should accompany predictions to support human verification workflows and build trust among pathologist users. Fourth, the system must integrate seamlessly with existing pathology information systems, requiring attention to HL7 messaging standards, LOINC interoperability specifications, and integration points with laboratory workflows.

4.9. Computational Efficiency and Scalability

The transformer-based architecture requires substantial computational resources during both training and inference phases, with BioBERT and BioClinicalBERT models containing approximately 110 million parameters each. GPU acceleration proved essential for achieving acceptable training times, with our three-epoch NER fine-tuning requiring approximately 6-8 hours on NVIDIA Tesla V100 GPUs. Training the standardization model (10 epochs) required approximately 4-5 hours on similar hardware. Inference latency for processing individual reports averaged 2-3 seconds per document, including entity extraction and multi-ontology standardization, representing acceptable performance for batch processing applications but potentially limiting real-time interactive use cases. For comparison, manual coding of pathology reports by humans typically takes 3-5 minutes per report [

54], suggesting that, even with computational overhead, automated approaches offer substantial time savings. The retrieval-augmented generation component adds computational overhead through dense vector similarity search across terminology databases containing hundreds of thousands of concepts. We employed approximate nearest neighbour search using FAISS (Facebook AI Similarity Search) indexing to maintain sub-second retrieval latency [

55]. FAISS enables efficient similarity search through product quantization and inverted-file indexing, reducing search time from linear O(n) to sublinear. For large-scale deployment processing thousands of daily reports, a distributed computing infrastructure would enable parallel processing across multiple GPU nodes. Model quantization techniques (e.g., INT8 quantization) and knowledge distillation could reduce computational requirements by 2-4x while maintaining acceptable accuracy decreases of typically 1-3% [

56]. These optimization techniques would enable deployment on more modest hardware configurations, potentially allowing inference on CPU-only systems for smaller institutions. The batch size of 8 during training represents a balance between GPU memory constraints (16GB for V100) and gradient estimation quality, with larger batches potentially improving convergence stability at the cost of increased memory consumption.

4.10. Limitations

Several methodological limitations warrant acknowledgment. First, the dataset derives from a single institution in Tunisia, potentially limiting generalizability to other geographic regions, healthcare systems, or pathology subspecialties with different reporting conventions. French-language medical terminology exhibits regional variations between France, Belgium, Switzerland, and North African countries, which could affect model performance on reports from other French-speaking regions [

57]. Multi-institutional validation across diverse clinical settings is necessary to assess external validity. Second, the test set size of 53 samples provided insufficient statistical power to detect moderate effect sizes between model architectures, as evidenced by non-significant McNemar and permutation test results despite descriptive performance differences. Sample size calculations suggest that 200-250 test samples would be required for adequately powered comparative evaluations [

46]. Third, the study focused exclusively on French-language anatomopathological reports, limiting applicability to other languages without additional training and validation. Cross-lingual transfer learning approaches could potentially extend the model to other Romance languages with moderate performance retention [

41]. Fourth, manual annotation by pathologists, while establishing gold-standard labels, may introduce inter-rater variability that affects ceiling performance estimates. We did not conduct a formal inter-annotator agreement assessment with multiple annotators, which would quantify annotation consistency and provide more robust ground truth labels. Fifth, the corpus emphasizes general anatomic pathology cases, potentially under-representing rare diagnoses, complex syndromic presentations, or specialized pathology domains such as neuropathology, forensic pathology, or molecular pathology. Sixth, computational resource requirements for transformer-based architectures may limit deployment feasibility in resource-constrained healthcare settings without adequate GPU infrastructure, though the aforementioned optimization techniques could mitigate this limitation. Seventh, the study evaluated performance on retrospective data without prospective validation in real-world clinical workflows, where integration challenges, user acceptance factors, and workflow disruption may impact practical utility. Finally, we did not evaluate the cost-effectiveness or time savings compared to manual coding, which would be essential for healthcare administrators considering implementation.

5. Conclusion

This study demonstrates that BioBERT-based Named Entity Recognition, combined with BioClinicalBERT and Retrieval-Augmented Generation, achieves strong performance in automated extraction and multi-ontology standardization of anatomopathological report entities. The hybrid architecture achieved F1-scores exceeding 0.963 for entity extraction, with a mean precision of 0.969 and a recall of 0.958, as confirmed by bootstrap confidence intervals and statistical significance testing, demonstrating performance substantially exceeding baseline thresholds. Multi-ontology standardization demonstrated substantial to near-perfect agreement across SNOMED CT (Cohen’s Kappa 0.7829), LOINC (Cohen’s Kappa 0.9773), and ICD-11 (Cohen’s Kappa 0.8735) terminologies, with particularly high performance for LOINC laboratory test mapping, achieving F1-macro of 0.9294. While retrieval augmentation provided descriptive performance improvements across all tasks, with consistent gains in accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-scores, statistical testing revealed non-significant differences given the current sample size of 53 test instances, indicating that larger validation studies are necessary to establish augmentation benefits with adequate statistical power definitively. The system demonstrates practical feasibility for reducing manual coding burden, improving data quality, and enhancing semantic interoperability across healthcare institutions. However, several critical steps remain before clinical deployment can be recommended. Multi-institutional validation studies across diverse geographic regions, languages, and pathology subspecialties are essential to assess generalizability and identify potential performance degradation scenarios when encountering different documentation styles, terminology preferences, and case mix patterns. A prospective evaluation comparing automated coding with expert pathologist annotations in real-world workflow conditions would quantify accuracy, identify failure modes, and establish quality assurance protocols for clinical integration. Integration with existing laboratory information systems and electronic health record platforms requires attention to computational efficiency, latency constraints, inference scalability, and failure mode handling to ensure reliable operation in production environments without disrupting clinical workflows. Human-in-the-loop workflows with confidence-based routing to manual review can maintain quality standards while maximizing automation benefits, optimizing the balance between efficiency gains and clinical safety through adaptive thresholding based on validation studies. Future research directions include expansion to multilingual pathology corpora enabling cross-linguistic model transfer through multilingual BERT variants, incorporation of multimodal data such as structured report sections and histopathological images for comprehensive diagnostic coding, hierarchical code prediction exploiting terminology structure and semantic relationships to improve rare code detection, active learning approaches to continuously improve performance with minimal annotation burden through intelligent sample selection, and federated learning frameworks enabling collaborative model development across institutions while preserving data privacy and regulatory compliance. The demonstrated technical feasibility, combined with straightforward clinical utility for improved data standardization, enhanced research capabilities, reduced coding costs, and better interoperability, motivates continued development toward robust, validated systems supporting pathology informatics infrastructure in modern healthcare systems, ultimately advancing the transformation of unstructured clinical narratives into actionable structured knowledge supporting evidence-based medicine, precision health initiatives, and data-driven clinical decision support.

Ethics Statement

This retrospective study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Ethics Committee of the Military Hospital of Tunis (decision number: 116/2025/CLPP/Hopital Militaire de Tunis) on July 7, 2025, before the commencement of data collection and analysis. All patient information was rigorously anonymized to ensure confidentiality and protect patient privacy. The handling and analysis of these data were conducted solely by the anatomical pathologists involved in the study, ensuring strict adherence to ethical standards and institutional guidelines.

Consent for Publication

All participants provided consent for the use of their data for research purposes and publications. All authors approved the final version to be published and agree to be accountable for any part of the work.

Availability of Data and Materials

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available upon request from the corresponding author.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Ai Usage Statement

In preparing this paper, the authors used ChatGPT model 5 on November 24, 2025, to revise some passages of the manuscript and to double-check for grammar mistakes or improve academic English only [

58,

59]. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as necessary and took full responsibility for the publication’s content.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

References

- Madabhushi; Lee, G. Image analysis and machine learning in digital pathology: Challenges and opportunities. Medical Image Analysis 2016, vol. 33, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vespa, E. , Histological Scores in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: The State of the Art. JCM 2022, vol. 11(no. 4), 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H. , Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA A Cancer J Clinicians 2021, vol. 71(no. 3), 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uslu, A.; Stausberg, J. Value of the Electronic Medical Record for Hospital Care: Update From the Literature. J Med Internet Res 2021, vol. 23(no. 12), e26323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y. H. , Histopathological correlations of CT-based radiomics imaging biomarkers in native kidney biopsy. BMC Med Imaging 2024, vol. 24(no. 1), 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler-Milstein, J.; Jha, A. K. HITECH Act Drove Large Gains In Hospital Electronic Health Record Adoption. Health Affairs 2017, vol. 36(no. 8), 1416–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brands, M. R.; Gouw, S. C.; Beestrum, M.; Cronin, R. M.; Fijnvandraat, K.; Badawy, S. M. Patient-Centered Digital Health Records and Their Effects on Health Outcomes: Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res 2022, vol. 24(no. 12), e43086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. , Clinical information extraction applications: A literature review. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 2018, vol. 77, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miake-Lye, M. , Transitioning from One Electronic Health Record to Another: A Systematic Review. J GEN INTERN MED 2023, vol. 38(no. S4), 956–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Névéol, A.; Dalianis, H.; Velupillai, S.; Savova, G.; Zweigenbaum, P. Clinical Natural Language Processing in languages other than English: opportunities and challenges. J Biomed Semant 2018, vol. 9(no. 1), 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, A.; Xiu, X.; Zhong, M.; Wu, S. Evaluating Medical Entity Recognition in Health Care: Entity Model Quantitative Study. JMIR Med Inform 2024, vol. 12, e59782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, M.-W.; Chang; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. arXiv:1810.04805. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A. Attention Is All You Need. arXiv:1706.03762. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1706.03762. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lee. , BioBERT: a pre-trained biomedical language representation model for biomedical text mining. Bioinformatics 2020, vol. 36(no. 4), 1234–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E. W. , MIMIC-CXR, a de-identified publicly available database of chest radiographs with free-text reports. Sci Data 2019, vol. 6(no. 1), 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsentzer, E. Publicly Available Clinical BERT Embeddings. arXiv:1904.03323. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Yan, S.; Lu, Z. Transfer Learning in Biomedical Natural Language Processing: An Evaluation of BERT and ELMo on Ten Benchmarking Datasets. In Proceedings of the 18th BioNLP Workshop and Shared Task; Florence, Italy, Association for Computational Linguistics, 2019; pp. 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, T.; Grieve, G. Principles of Health Interoperability: SNOMED CT, HL7 and FHIR. In Health Information Technology Standards; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, E.; McInnes, B. T. An overview of biomedical entity linking throughout the years. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 2023, vol. 137, 104252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly. SNOMED-CT: The advanced terminology and coding system for eHealth. Stud Health Technol Inform 2006, vol. 121, 279–290. [Google Scholar]

- Vreeman, D. J.; McDonald, C. J. Automated mapping of local radiology terms to LOINC. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2005, vol. 2005, 769–773. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, J. E.; Weber, S.; Jakob, R.; Chute, C. G. ICD-11: an international classification of diseases for the twenty-first century. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2021, vol. 21(no. S6), 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, K. W. , Promoting interoperability between SNOMED CT and ICD-11: lessons learned from the pilot project mapping between SNOMED CT and the ICD-11 Foundation. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2024, vol. 31(no. 8), 1631–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rector, A. L.; Brandt, S.; Schneider, T. Getting the foot out of the pelvis: modeling problems affecting use of SNOMED CT hierarchies in practical applications. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2011, vol. 18(no. 4), 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H. Jeon; Lee, J.; Kang, J. Biomedical Entity Representations with Synonym Marginalization. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 2020; Association for Computational Linguistics: Online; pp. 3641–3650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Liu, Y.; Tan, C.; Huang, S.; Huang, F. Improving Biomedical Pretrained Language Models with Knowledge. In Proceedings of the 20th Workshop on Biomedical Language Processing; Association for Computational Linguistics: Online, 2021; pp. 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, P. “Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Knowledge-Intensive NLP Tasks,” Apr. 12, 2021. arXiv:2005.11401. [CrossRef]

- Guu, K.; Lee, K.; Tung, Z.; Pasupat, P.; Chang, M.-W. REALM: Retrieval-Augmented Language Model Pre-Training. arXiv:2002.08909. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreimeyer, K. , Natural language processing systems for capturing and standardizing unstructured clinical information: A systematic review. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 2017, vol. 73, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhai, Y.; Gao, J.; Wang, L.; Hou, L.; Zhao, J. Stacking-BERT model for Chinese medical procedure entity normalization. MBE 2022, vol. 20(no. 1), 1018–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li; Kilicoglu, H.; Xu, H.; Zhang, R. BiomedRAG: A retrieval augmented large language model for biomedicine. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 2025, vol. 162, 104769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. In Reprint, 2. ed.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Loshchilov; Hutter, F. Decoupled Weight Decay Regularization. arXiv:1711.05101. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efron; Tibshirani, R. J. An introduction to the bootstrap. In Monographs on statistics and applied probability; Chapman & Hall: New York, 1993; Volume no. 57. [Google Scholar]

- Landis, R.; Koch, G. G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977, vol. 33(no. 1), 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNemar, Q. Note on the Sampling Error of the Difference Between Correlated Proportions or Percentages. Psychometrika 1947, vol. 12(no. 2), 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, S.-H.; Lee; Lee, I. NEAR: Named entity and attribute recognition of clinical concepts. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 2022, vol. 130, 104092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltagy, K. Lo; Cohan, A. SciBERT: A Pretrained Language Model for Scientific Text. arXiv:1903.10676. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzuner, Ö.; South, B. R.; Shen, S.; DuVall, S. L. 2010 i2b2/VA challenge on concepts, assertions, and relations in clinical text. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2011, vol. 18(no. 5), 552–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. , A clinical text classification paradigm using weak supervision and deep representation. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2019, vol. 19(no. 1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, T.; Schlinger, E.; Garrette, D. How multilingual is Multilingual BERT? arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.01502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, W. W.; Nadkarni, P. M.; Hirschman, L.; D’Avolio, L. W.; Savova, G. K.; Uzuner, O. Overcoming barriers to NLP for clinical text: the role of shared tasks and the need for additional creative solutions. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2011, vol. 18(no. 5), 540–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutto, S. R. , Automatic ICD-10-CM coding via Lambda-Scaled attention based deep learning model. Methods 2024, vol. 222, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.-F. , Automatic International Classification of Diseases Coding System: Deep Contextualized Language Model With Rule-Based Approaches. JMIR Med Inform 2022, vol. 10(no. 6), e37557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullenbach, J.; Wiegreffe, S.; Duke, J.; Sun, J.; Eisenstein, J. Explainable Prediction of Medical Codes from Clinical Text. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies; Association for Computational Linguistics: New Orleans, Louisiana, 2018; Volume 1, pp. 1101–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoenig, M.; Heisey, D. M. The Abuse of Power: The Pervasive Fallacy of Power Calculations for Data Analysis. The American Statistician 2001, vol. 55(no. 1), 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wallace, B. A Sensitivity Analysis of (and Practitioners’ Guide to) Convolutional Neural Networks for Sentence Classification. arXiv:1510.03820. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, M.; Hegselmann, S.; Lang, H.; Kim, Y.; Sontag, D. Large Language Models are Few-Shot Clinical Information Extractors. arXiv:2205.12689. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, M.-C.; Vreeman, D. J.; Huff, S. M. Investigating the semantic interoperability of laboratory data exchanged using LOINC codes in three large institutions. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2011, vol. 2011, 805–814. [Google Scholar]

- Malley, J. O’; Cook, K. F.; Price, M. D.; Wildes, K. R.; Hurdle, J. F.; Ashton, C. M. Measuring Diagnoses: ICD Code Accuracy. Health Services Research 2005, vol. 40(no. 5p2), 1620–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cahill; Cleary, B. J.; Cullinan, S. The influence of electronic health record design on usability and medication safety: systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 2025, vol. 25(no. 1), 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman; Elhadad, N. Natural Language Processing in Health Care and Biomedicine. In Biomedical Informatics; Shortliffe, E. H., Cimino, J. J., Eds.; Springer London: London, 2014; pp. 255–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, G. I.; Hyde, R.; Cao, H.; Nguyen, H. L.; Petitjean, F. Characterizing Concept Drift. Data Min Knowl Disc 2016, vol. 30(no. 4), 964–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanfill, H.; Williams, M.; Fenton, S. H.; Jenders, R. A.; Hersh, W. R. A systematic literature review of automated clinical coding and classification systems. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2010, vol. 17(no. 6), 646–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M. Douze; Jégou, H. Billion-scale similarity search with GPUs. arXiv:1702.08734. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafrir, A.; Boudoukh, G.; Izsak, P.; Wasserblat, M. Q8BERT: Quantized 8Bit BERT. In 2019 Fifth Workshop on Energy Efficient Machine Learning and Cognitive Computing - NeurIPS Edition (EMC2-NIPS); Dec 2019; pp. 36–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grouin; Grabar, N.; Hamon, T.; Rosset, S.; Tannier, X.; Zweigenbaum, P. Eventual situations for timeline extraction from clinical reports. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2013, vol. 20(no. 5), 820–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dergaa. Moving Beyond the Stigma: Understanding and Overcoming the Resistance to the Acceptance and Adoption of Artificial Intelligence Chatbots. NAJM 2023, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dergaa. , A thorough examination of ChatGPT-3.5 potential applications in medical writing: A preliminary study. Medicine 2024, vol. 103(no. 40), e39757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).