Submitted:

11 December 2025

Posted:

14 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

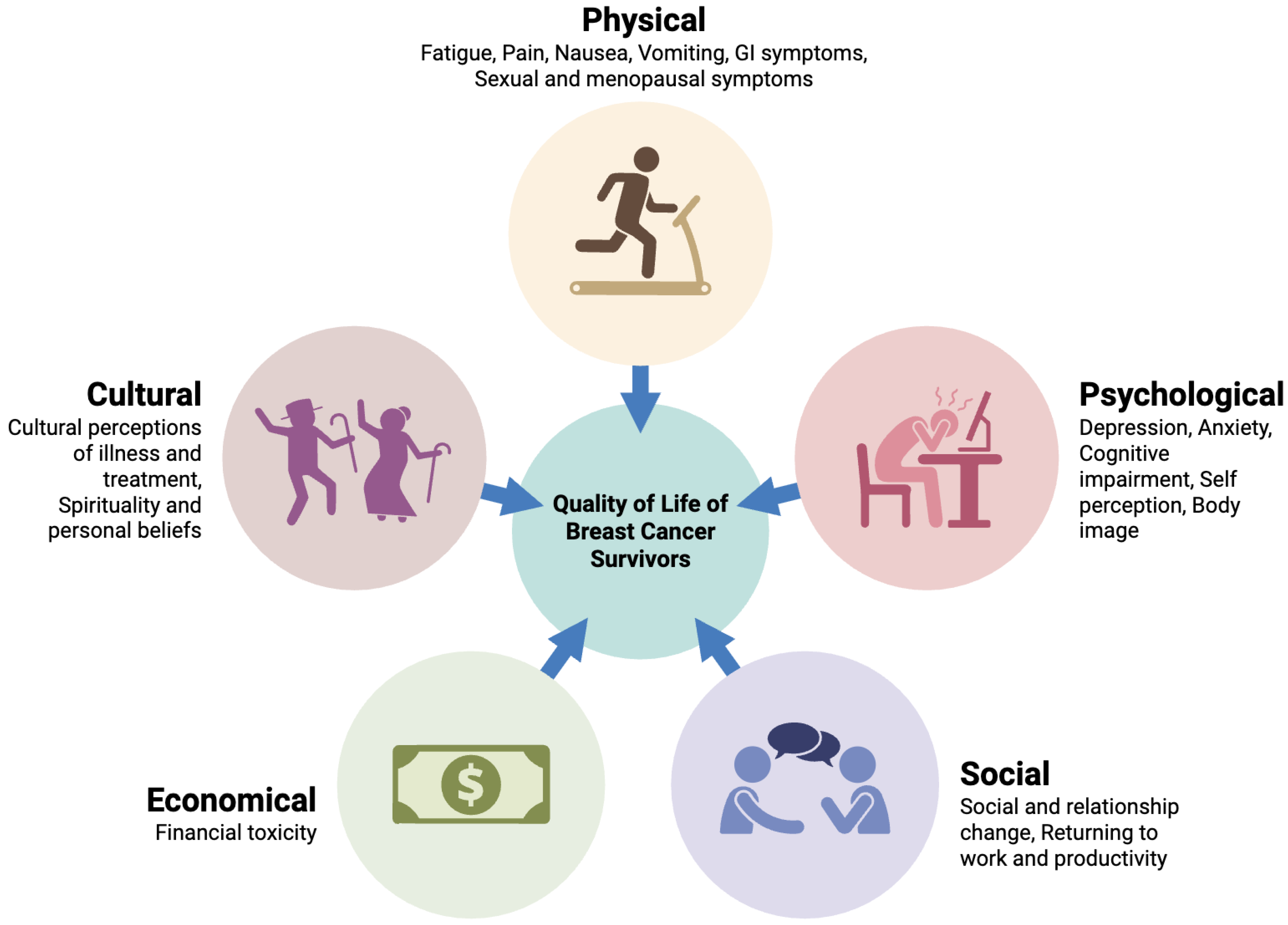

1. Introduction

2. Impact of Chemotherapy on Physical Domain of QoL

2.1. Fatigue and Physical Functioning

2.2. Neuropathy and Pain

2.3. Nausea, Vomiting, and Gastrointestinal Distress

2.4. Sexual Health and Menopausal Symptoms

3. Psychological and Emotional Effects

3.1. Depression and Anxiety

3.2. Cognitive Impairment

3.3. Body Image and Self-Perception

4. Socioeconomical Well-Being

4.1. Social Role and Relationship Changes

4.2. Return to Work and Productivity

4.3. Financial Toxicity

5. Measuring QoL in Breast Cancer Patients

5.1. QoL Assessment Tools

5.2. Methodological Considerations

6. Variability Across Patient Subgroups

6.1. Age and Menopausal Status

6.2. Socioeconomic and Racial Disparities

6.3. Metastatic vs. Early-Stage Disease

7. Interventions and Supportive Care to Mitigate QoL Decline

7.1. Physical Rehabilitation and Exercise

7.2. Psychosocial Interventions

7.3. Pharmacological Management

7.4. Nutritional and Complementary Therapies

8. Research Gaps and Future Directions

9. Conclusion

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arnold, M; Morgan, E; Rumgay, H; Mafra, A; Singh, D; Laversanne, M; et al. Current and future burden of breast cancer: Global statistics for 2020 and 2040. The Breast 2022, 66, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qari, AS; Mowais, AH; Alharbi, SM; Almuayrifi, MJ; Al Asiri, AA; Alwatid, SA; et al. Adjuvant and Neoadjuvant Therapy for Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review. Ejbh 2024, 156–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, S. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancers. Womens Health (Lond) 2016, 12, 480–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, M; Johnson, N. Pre-surgical chemotherapy for breast cancer may be associated with improved outcomes. The American Journal of Surgery 2018, 215, 931–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, HK. Adjuvant therapy for breast cancer. West J Med 2001, 174, 284–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buziashvili, JI; Stilidi, IS; Asymbekova, EU; Mackeplishvili, ST; Tugeeva, EF; Ahmedyarova, NK; et al. Comprehensive assessment of quality of life in patients during neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Medicinskij Alfavit 2022, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langeh, U; Kumar, V; Ahuja, P; Singh, C; Singh, A. An update on breast cancer chemotherapy-associated toxicity and their management approaches. Health Sciences Review 2023, 9, 100119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dent, R; Cortés, J; Pusztai, L; McArthur, H; Kümmel, S; Bergh, J; et al. Neoadjuvant pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy/adjuvant pembrolizumab for early-stage triple-negative breast cancer: quality-of-life results from the randomized KEYNOTE-522 study. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2024, 116, 1654–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Maqbali, M; Al Sinani, M; Al Naamani, Z; Al Badi, K; Tanash, MI. Prevalence of Fatigue in Patients With Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 2021, 61, 167–189.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajj, A; Chamoun, R; Salameh, P; Khoury, R; Hachem, R; Sacre, H; et al. Fatigue in breast cancer patients on chemotherapy: a cross-sectional study exploring clinical, biological, and genetic factors. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthanna, FMS; Iqbal, MS; Karuppannan, M; Abdulrahman, E; Adulyarat, N; Al-Ghorafi, MAA; et al. Prevalence and associated factors of fatigue among breast cancer patients in Malaysia—A prospective study. J App Pharm Sci 2022, 12, 131–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Bustos, A; de Pedro, CG; Romero-Elías, M; Ramos, J; Osorio, P; Cantos, B; et al. Prevalence and correlates of cancer-related fatigue in breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 2021, 29, 6523–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thong, MSY; van Noorden, CJF; Steindorf, K; Arndt, V. Cancer-Related Fatigue: Causes and Current Treatment Options. Curr Treat Options Oncol 2020, 21, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthanna, FMS; Karuppannan, M; Hassan, BAR; Mohammed, AH. Impact of fatigue on quality of life among breast cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. PHRP 2021, 12, 115–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilliam, LAA; St. Clair, DK. Chemotherapy-Induced Weakness and Fatigue in Skeletal Muscle: The Role of Oxidative Stress. Antioxid Redox Signal 2011, 15, 2543–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, CM; Hsieh, CC; Sprod, LK; Carter, SD; Hayward, R. Cancer treatment-induced alterations in muscular fitness and quality of life: the role of exercise training. Annals of Oncology 2007, 18, 1957–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uslu, A; Canbolat, O. Relationship Between Frailty and Fatigue in Older Cancer Patients. Seminars in Oncology Nursing 2021, 37, 151179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S; Xiong, T; Guo, S; Zhu, C; He, J; Wang, S. An up-to-date view of paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy. Journal of Cancer Research and Therapeutics 2023, 19, 1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, N; Sukumar, J; Lustberg, MB. Chronic chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: living with neuropathy during and after cancer treatments. Annals of Palliative Medicine 2025, 14, 19616–19216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maihöfner, C; Diel, I; Tesch, H; Quandel, T; Baron, R. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN): current therapies and topical treatment option with high-concentration capsaicin. Support Care Cancer 2021, 29, 4223–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jheng, Y-W; Chan, Y-N; Wu, C-J; Lin, M-W; Tseng, L-M; Wang, Y-J. Neuropathic Pain Affects Quality of Life in Breast Cancer Survivors with Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy. Pain Management Nursing 2024, 25, 308–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, L; Visovsky, C. Psychological distress and quality of life in breast cancer survivors with taxane-induced peripheral neuropathy: A scoping review. Front Oncol 2023, 12, 1005083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, BS; Gbadamosi, B; Jaiyesimi, IA. The relationship between chemotherapy-induced neuropathy and quality of life in breast cancer survivors. JCO 2018, 36, e22111–e22111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy and rehabilitation: A review. Seminars in Oncology 2021, 48, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahfouz, FM; Li, T; Joda, M; Harrison, M; Horvath, LG; Grimison, P; et al. Sleep dysfunction associated with worse chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurotoxicity functional outcomes. Support Care Cancer 2024, 32, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozzo, T de O; de Souza, SG; Moysés, AMB; Panobianco, MS; de Almeida, AM. Incidence and management of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in women with breast cancer. Rev Gaúcha Enferm 2014, 35, 117–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, KP; Kober, KM; Ernst, B; Sachdev, J; Brewer, M; Zhu, Q; et al. Multiple Gastrointestinal Symptoms Are Associated With Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea In Patients With Breast Cancer. Cancer Nurs 2022, 45, 181–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam, R; Haileselassie, W; Solomon, N; Desalegn, Y; Tigeneh, W; Suga, Y; et al. Nutritional status and quality of life among breast Cancer patients undergoing treatment in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Womens Health 2023, 23, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, GM; Delrieu, L; Bouleuc, C; Pierga, J-Y; Cottu, P; Berger, F; et al. Prevalence and survival implications of malnutrition and sarcopenia in metastatic breast cancer: A longitudinal analysis. Clinical Nutrition 2024, 43, 1710–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, DJ. Nausea and Vomiting in Cancer Patients. In Nausea and Vomiting; CRC Press, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, M. Individual differences in chemotherapy-induced anticipatory nausea. Front Psychol 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haris, I; Hutajulu, SH; Astari, YK; Wiranata, JA; Widodo, I; Kurnianda, J; et al. Sexual Dysfunction Following Breast Cancer Chemotherapy: A Cross-Sectional Study in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Cureus n.d., 15, e41744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H; Yoon, HG. Menopausal symptoms, sexual function, depression, and quality of life in Korean patients with breast cancer receiving chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer 2013, 21, 2499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fallbjörk, U; Rasmussen, BH; Karlsson, S; Salander, P. Aspects of body image after mastectomy due to breast cancer – A two-year follow-up study. European Journal of Oncology Nursing 2013, 17, 340–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lester, J; Pahouja, G; Andersen, B; Lustberg, M. Atrophic Vaginitis in Breast Cancer Survivors: A Difficult Survivorship Issue. J Pers Med 2015, 5, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biglia, N; Bounous, VE; D’Alonzo, M; Ottino, L; Tuninetti, V; Robba, E; et al. Vaginal Atrophy in Breast Cancer Survivors: Attitude and Approaches Among Oncologists. Clinical Breast Cancer 2017, 17, 611–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, MS; Peate, M; Jarvis, S; Hickey, M; Friedlander, M. A clinical guide to the management of genitourinary symptoms in breast cancer survivors on endocrine therapy. Ther Adv Med Oncol 2017, 9, 269–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulvat, MC; Jeruss, JS. Maintaining Fertility in Young Women with Breast Cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol 2009, 10, 308–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathelin, C; Brettes, J-P; Diemunsch, P. Premature ovarian failure after chemotherapy for breast cancer. Bull Cancer 2008, 95, 403–12. [Google Scholar]

- Pourali, L; Taghizadeh Kermani, A; Ghavamnasiri, MR; Khoshroo, F; Hosseini, S; Asadi, M; et al. Incidence of Chemotherapy-Induced Amenorrhea After Adjuvant Chemotherapy With Taxane and Anthracyclines in Young Patients With Breast Cancer. Iran J Cancer Prev 2013, 6, 147–50. [Google Scholar]

- Cosimo, SD; Alimonti, A; Ferretti, G; Sperduti, I; Carlini, P; Papaldo, P; et al. Incidence of chemotherapy-induced amenorrhea depending on the timing of treatment by menstrual cycle phase in women with early breast cancer. Annals of Oncology 2004, 15, 1065–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, WKW; Law, BMH; Ng, MSN; He, X; Chan, DNS; Chan, CWH; et al. Symptom clusters experienced by breast cancer patients at various treatment stages: A systematic review. Cancer Medicine 2021, 10, 2531–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopwood, P; Sumo, G; Mills, J; Haviland, J; Bliss, JM. The course of anxiety and depression over 5 years of follow-up and risk factors in women with early breast cancer: Results from the UK Standardisation of Radiotherapy Trials (START). The Breast 2010, 19, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgess, C; Cornelius, V; Love, S; Graham, J; Richards, M; Ramirez, A. Depression and anxiety in women with early breast cancer: five year observational cohort study. BMJ 2005, 330, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadheech, A; Kumawat, S; Sharma, D; Gothwal, RS; Dana, R; Meena, C; et al. The Prevalence of Anxiety and Depression in Breast Cancer Patients and their Correlation with Socio-Demographic Factors. Asian Pac J Cancer Care 2023, 8, 675–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaras, K; Papathanasiou, IV; Mitsi, D; Veneti, A; Kelesi, M; Zyga, S; et al. Assessment of Depression and Anxiety in Breast Cancer Patients: Prevalence and Associated Factors. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeish, BL; Richardson, JK; Whitney, DG. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy onset is associated with early risk of depression and anxiety in breast cancer survivors. European J Cancer Care 2022, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reece, JC; Chan, Y-F; Herbert, J; Gralow, J; Fann, JR. Course of depression, mental health service utilization and treatment preferences in women receiving chemotherapy for breast cancer. General Hospital Psychiatry 2013, 35, 376–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- REN, X; BORIERO, D; CHAISWING, L; BONDADA, S; CLAIR DKST; BUTTERFIELD, DA. Plausible Biochemical Mechanisms of Chemotherapy-induced Cognitive Impairment (“Chemobrain”), a Condition That Significantly Impairs the Quality of Life of Many Cancer Survivors. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2019, 1865, 1088–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, G; Giustiniani, A; Danesin, L; Burgio, F; Arcara, G; Conte, P. Cognitive impairment following breast cancer treatments: an umbrella review. The Oncologist 2024, 29, e848–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andryszak, P; Wiłkość, M; Żurawski, B; Izdebski, P. Verbal fluency in breast cancer patients treated with chemotherapy. Breast Cancer 2017, 24, 376–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amani, O; Mazaheri, MA; Moghani, MM; Zarani, F; Choolabi, RH. Chemotherapy-induced cognitive impairment in breast cancer survivors: A systematic review of studies from 2000 to 2021. Cancer Reports 2024, 7, e1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y; Hendrix, CC. Cancer-Related Cognitive Impairment in Breast Cancer Patients: Influences of Psychological Variables. Asia-Pacific Journal of Oncology Nursing 2018, 5, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordhjem, BJT; Hjalgrim, LL. Cancer-related cognitive impairment and hippocampal functioning: The role of dynamin-1. Neurotherapeutics 2024, 22, e00508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X; Chen, H; Lv, Y; Chao, HH; Gong, L; Li, C-SR; et al. Diminished gray matter density mediates chemotherapy dosage-related cognitive impairment in breast cancer patients. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 13801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, DHS; Sleurs, C; Gavrila Laic, RA; Amidi, A; Chen, BT; Deprez, S; et al. Neuroimaging studies of cognitive dysfunction following cancer and treatment. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology n.d., 0, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A; Ranadive, N; Kinra, M; Nampoothiri, M; Arora, D; Mudgal, J. An Overview on Chemotherapy-induced Cognitive Impairment and Potential Role of Antidepressants. Curr Neuropharmacol 2020, 18, 838–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, T; Yagata, H; Saito, M; Okada, H; Takayama, T; Imai, H; et al. Abstract P5-15-09: National survey of chemotherapy-induced appearance issues in breast cancer patients. Cancer Research 2015, 75, P5-15-09-P5-15–09. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, EEC; Pereira, SCDC; Pereira, EDAT; Constante, ES; Bindi, MCV. Body image perceptions of women with breast cancer undergoing antineoplastic chemotherapy. JHS 2022, 2, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, A. My body my self: Body image and sexuality in women with cancer. CONJ 2009, 19, E1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partridge, A. Abstract SP114: Body Image and Sexual Health. Cancer Research 2021, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sghaier, A; Kaabia, O; Bouchahda, R. (265) Self-Image after Breast Cancer. The Journal of Sexual Medicine 2024, 21, qdae002.228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleasant, VA; Purkiss, AS; Merjaver, SD. Redefining the “crown”: Approaching chemotherapy-induced alopecia among Black patients with breast cancer. Cancer 2023, 129, 1629–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadaei, S; Janighorban, M; Mehrabi, T. P656 Study of the effect of cognitive behavioral counseling on body image alterations in women who have undergone mastectomy. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 2009, 107, S601–S601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W; Chong, YY; Chien, WT. Effectiveness of cognitive-based interventions for improving body image of patients having breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs 2023, 10, 100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, T; Ping, Y; Jing, CM; Xu, ZX; Ping, Z. The efficacy of internet-based cognitive behavior therapy for psychological health and quality of life among breast cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y; Feng, W. Cancer-related psychosocial challenges. Gen Psychiatr 2022, 35, e100871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalambous, A; Kaite, CP; Charalambous, M; Tistsi, T; Kouta, C. The effects on anxiety and quality of life of breast cancer patients following completion of the first cycle of chemotherapy. SAGE Open Med 2017, 5, 2050312117717507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. K, L. S, P. B, S. G, R. L-P. Psychosocial experiences of breast cancer survivors: a meta-review. J Cancer Surviv 2024, 18, 84–123. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues-Machado, N; Bonfill-Cosp, X; Quintana, MJ; Santero, M; Bártolo, A; Olid, AS. Sexual dysfunction in women with breast cancer: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer 2025, 33, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C; Qiu, X; Yang, X; Mao, J; Li, Q. Factors Influencing Social Isolation among Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review. Healthcare (Basel) 2024, 12, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y; Huang, Q; Wu, F; Yang, Y; Wang, L; Zong, X; et al. Impact of social support on cognitive function in patients with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy: The chain-mediating role of fatigue and depression. Asia-Pacific Journal of Oncology Nursing 2025, 12, 100743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, R; Xie, T; Zhang, L; Gong, N; Zhang, J. Stigma and its influencing factors among breast cancer survivors in China: A cross-sectional study. European Journal of Oncology Nursing 2021, 52, 101972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J; Shubair, M. Returning to Work After Breast Cancer: A Critical Review. International Journal of Disability Management 2013, 8, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merdawati, L; Lin, H-C; Pan, C-H; Huang, H-C. Factors Associated With Not Returning to Work Among Breast Cancer Survivors. Workplace Health Saf 2025, 73, 216–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, CJ; Yip, SYC; Chan, RJ; Chew, L; Chan, A. Investigating how cancer-related symptoms influence work outcomes among cancer survivors: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv 2022, 16, 1065–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joly, F; Lange, M; Dos Santos, M; Vaz-Luis, I; Di Meglio, A. Long-Term Fatigue and Cognitive Disorders in Breast Cancer Survivors. Cancers (Basel) 2019, 11, 1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peipins, LA; Dasari, S; Rodriguez, JL; White, MC; Hodgson, ME; Sandler, DP. Employment After Breast Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment Among Women in the Sister and the Two Sister Studies. J Occup Rehabil 2021, 31, 543–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, A; Vaz Luis, I; Bovagnet, T; El Mouhebb, M; Di Meglio, A; Pinto, S; et al. Impact of Breast Cancer Treatment on Employment: Results of a Multicenter Prospective Cohort Study (CANTO). JCO 2020, 38, 734–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blinder, V; Eberle, C; Patil, S; Gany, FM; Bradley, CJ. Women With Breast Cancer Who Work For Accommodating Employers More Likely To Retain Jobs After Treatment. Health Affairs 2017, 36, 274–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, JK; Adetunji, F; Kibria, GMA; Swanberg, JE. Cancer-work management: Hourly and salaried wage women’s experiences managing the cancer-work interface following new breast cancer diagnosis. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0241795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stergiou-Kita, M; Qie, X; Yau, HK; Lindsay, S. Stigma and work discrimination among cancer survivors: A scoping review and recommendations: Stigmatisation et discrimination au travail des survivants du cancer : Examen de la portée et recommandations. Can J Occup Ther 2017, 84, 178–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Muijen, P; Weevers, N l. e. c.; Snels, I a. k.; Duijts, S f. a.; Bruinvels, D j.; Schellart, A j. m.; et al. Predictors of return to work and employment in cancer survivors: a systematic review. European Journal of Cancer Care 2013, 22, 144–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehsan, AN; Wu, CA; Minasian, A; Singh, T; Bass, M; Pace, L; et al. Financial Toxicity Among Patients With Breast Cancer Worldwide. JAMA Netw Open 2023, 6, e2255388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, KL; Eniu, A; Booth, CM; MacDonald, M; Chino, F. Financial Toxicity and Breast Cancer: Why Does It Matter, Who Is at Risk, and How Do We Intervene? Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2025, 45, e473450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngan, TT; Van Minh, H; Donnelly, M; O’Neill, C. Financial toxicity due to breast cancer treatment in low- and middle-income countries: evidence from Vietnam. Support Care Cancer 2021, 29, 6325–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabroff, KR; Gansler, T; Wender, RC; Cullen, KJ; Brawley, OW. Minimizing the burden of cancer in the United States: Goals for a high-performing health care system. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2019, 69, 166–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J; Zheng, Z; Han, X; Davidoff, AJ; Banegas, MP; Rai, A; et al. Cancer History, Health Insurance Coverage, and Cost-Related Medication Nonadherence and Medication Cost-Coping Strategies in the United States. Value in Health 2019, 22, 762–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y; Ah, DV. Cancer-related cognitive impairment: updates to treatment, the need for more evidence, and impact on quality of life—a narrative review. Annals of Palliative Medicine 2024, 13, 1265280–1261280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, LM; Hoerger, M; Seibert, K; Gerhart, JI; O’Mahony, S; Duberstein, PR. Financial Strain and Physical and Emotional Quality of Life in Breast Cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 2019, 58, 454–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasanah, U; Ahmad, M; Prihantono, P; Usman, AN; Arsyad, A; Agustin, DI. The quality of life assessment of breast cancer patients. Breast Dis n.d., 43, 173–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montazeri, A. Health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients: A bibliographic review of the literature from 1974 to 2007. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2008, 27, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, ML; Idris, DB; Teo, LW; Loh, SY; Seow, GC; Chia, YY; et al. Validation of EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-BR23 questionnaires in the measurement of quality of life of breast cancer patients in Singapore. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs 2014, 1, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karsten, MM; Roehle, R; Albers, S; Pross, T; Hage, AM; Weiler, K; et al. Real-world reference scores for EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ-BR23 in early breast cancer patients. European Journal of Cancer 2022, 163, 128–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M; Al-Wassia, R; Alkhayyat, SS; Baig, M; Al-Saati, BA. Assessment of quality of life (QoL) in breast cancer patients by using EORTC QLQ-C30 and BR-23 questionnaires: A tertiary care center survey in the western region of Saudi Arabia. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0219093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, MJ; Cella, DF; Mo, F; Bonomi, AE; Tulsky, DS; Lloyd, SR; et al. Reliability and validity of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast quality-of-life instrument. J Clin Oncol 1997, 15, 974–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarsheda, SB; Bhise, AR. Association of Fatigue, Quality of Life and Functional Capacity in Breast Cancer Patients Receiving Adjuvant Chemotherapy. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Care 2021, 6, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, JE; Sherbourne, CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992, 30, 473–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, SH; Min, Y-S; Park, HY; Jung, T-D. Health-Related Quality of Life in Breast Cancer Patients with Lymphedema Who Survived More than One Year after Surgery. J Breast Cancer 2012, 15, 449–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janabi, S; Gharaibeh, L; Aldeeb, I; Abuhaliema, A. Quality of Life Assessment of Breast Cancer Patients Undergoing Chemotherapy in Jordan: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Breast Cancer 2025, 2025, 9936131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanghera, S; Coast, J; Walther, A; Peters, TJ. The Influence of Recall and Timing of Assessment on the Estimation of Quality-Adjusted Life-Years When Health Fluctuates Recurrently. Value in Health 2025, 28, 275–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byar, KL; Berger, AM; Bakken, SL; Cetak, MA. Impact of adjuvant breast cancer chemotherapy on fatigue, other symptoms, and quality of life. Oncol Nurs Forum 2006, 33, E18-26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minasian, LM; O’Mara, A; Mitchell, SA. Clinician and Patient Reporting of Symptomatic Adverse Events in Cancer Clinical Trials: Using CTCAE and PRO-CTCAE® to Provide Two Distinct and Complementary Perspectives. Patient Relat Outcome Meas 2022, 13, 249–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh-Dagher, S; Duong, T-A; Tournigand, C; Kempf, E; Lamé, G. Concordance between patient-reported outcomes and CTCAE clinician-reported toxicities during outpatient chemotherapy courses: a retrospective cohort study in routine care. ESMO Real World Data and Digital Oncology 2025, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partridge, AH. Chemotherapy in Premenopausal Breast Cancer Patients. Breast Care (Basel) 2015, 10, 307–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeo, W; Pang, E; Liem, GS; Suen, JJS; Ng, RYW; Yip, CCH; et al. Menopausal symptoms in relationship to breast cancer-specific quality of life after adjuvant cytotoxic treatment in young breast cancer survivors. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anders, CK; Johnson, R; Litton, J; Phillips, M; Bleyer, A. Breast Cancer Before Age 40 Years. Semin Oncol 2009, 36, 237–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pancakarsa, EP; Soemitro, MP; Budianto, A; Abdurahman, M; Rizki, KA; Azhar, Y; et al. Analysis of Risk Factors for Psychological Stress in Breast Cancer Patients: Observational Study in West Java, Indonesia. 2024, 8, 4648–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorman, JR; Usita, P; Madlensky, L; Pierce, JP. Young Breast Cancer Survivors: Their Perspectives on Treatment Decisions and Fertility Concerns. Cancer Nurs 2011, 34, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard-Anderson, J; Ganz, PA; Bower, JE; Stanton, AL. Quality of Life, Fertility Concerns, and Behavioral Health Outcomes in Younger Breast Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review; Journal of the National Cancer Institute: JNCI, 2012; Volume 104, pp. 386–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, RF; Oliveira, AI; Cruz, AS; Ribeiro, O; Afreixo, V; Pimentel, F. Polypharmacy and drug interactions in older patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy: associated factors. BMC Geriatr 2024, 24, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutanto, H. Tackling polypharmacy in geriatric patients: Is increasing physicians’ awareness adequate? Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics Plus 2025, 2, 100185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggiore, RJ; Feng, T; Dale, W; Gross, CP; Tew, WP; Mohile, SG; et al. Measures of polypharmacy and chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with cancer. JCO 2013, 31, 9545–9545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, JN; Dumas, J; Newhouse, P. Cognitive Effects of Chemotherapy and Cancer-Related Treatments in Older Adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2017, 25, 1415–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, F; Matsuoka, A; Obama, K; Mehnert-Theuerkauf, A; Uchitomi, Y; Fujimori, M. Quality of life in older patients with cancer and related unmet needs: a scoping review. AO 2025, 64, 516–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, SM; Partridge, AH. Premature menopause in young breast cancer: effects on quality of life and treatment interventions. J Thorac Dis 2013, 5, S55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, NK; Gabrick, KS; Chouairi, F; Mets, EJ; Avraham, T; Alperovich, M. Impact of socioeconomic status on psychological functioning in survivorship following breast cancer and reconstruction. The Breast Journal 2020, 26, 1695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, ECS; Hoskin, PJ. Health inequalities in cancer care: a literature review of pathways to diagnosis in the United Kingdom. eClinicalMedicine 2024, 76, 102864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puckett, Y; Sule, AA. Disparity in Early Detection of Breast Cancer. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ping, C; Andrade, DC; Housten, A; Doering, M; Goldstein, E; Politi, MC. A Scoping Review of Interventions to Address Financial Toxicity in Pediatric and Adult Patients and Survivors of Cancer. Cancer Med 2025, 14, e70879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragavan, MV; Mora, RV; Winder, K; Incudine, A; Cunningham, R; Stivers, T; et al. Impact of a Comprehensive Financial Resource on Financial Toxicity in a National, Multiethnic Sample of Adult, Adolescent/Young Adult, and Pediatric Patients With Cancer. JCO Oncology Practice 2023, 19, e286–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, AW. Religion and Mental Health in Racial and Ethnic Minority Populations: A Review of the Literature. Innovation in Aging 2020, 4, igaa035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coughlin, SS; Vernon, M; Hatzigeorgiou, C; George, V. Health Literacy, Social Determinants of Health, and Disease Prevention and Control. J Environ Health Sci 2020, 6, 3061. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke-Jeffers, P; Keyte, R; Connabeer, K. “Hair is your crown and glory” – Black women’s experiences of living with alopecia and the role of social support. Health Psychol Rep 2024, 12, 154–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleasant, VA; Purkiss, AS; Merjaver, SD. Redefining the “crown”: Approaching chemotherapy-induced alopecia among Black patients with breast cancer. Cancer 2023, 129, 1629–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karliner, LS; Hwang, ES; Nickleach, D; Kaplan, CP. Language barriers and patient-centered breast cancer care. Patient Educ Couns 2011, 84, 223–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidary, Z; Ghaemi, M; Hossein Rashidi, B; Kohandel Gargari, O; Montazeri, A. Quality of Life in Breast Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review of the Qualitative Studies. Cancer Control 2023, 30, 10732748231168318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, AS; Hürny, C; Peterson, HF; Bernhard, J; Castiglione-Gertsch, M; Gelber, RD; et al. Quality of life scores predict outcome in metastatic but not in early breast cancer. The Breast 2001, 10, 164–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İzci, F; İlgün, AS; Fındıklı, E; Özmen, V. Psychiatric Symptoms and Psychosocial Problems in Patients with Breast Cancer. J Breast Health 2016, 12, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M; Yu, S-Y; Jeon, H-L; Song, I. Factors Affecting Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients With Metastatic Breast Cancer. Journal of Breast Cancer 2023, 26, 436–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, Y; Feder, SL; Lustberg, M; Batten, J; Knobf, MT. Health-Related Quality of Life in Women With Metastatic Breast Cancer: An Integrative Review. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2025, 81, 3485–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocamaz, D; Düger, T. Breast Cancer and Exercise. In Breast Cancer Biology; Afroze, D, Rah, B, Ali, S, Shehjar, F, Ishaq Dar, M, S. Chauhan, S, et al., Eds.; IntechOpen, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, AM; Velthuis, M; Travier, N; Steins Bisschop, CN; Van Der Wall, E; Peeters, P. Physical activity during cancer treatment (PACT) study: Short- and long-term effects on fatigue of an 18-week exercise intervention during adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with breast or colon cancer. JCO 2014, 32, 9535–9535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, J; Cho, Y; Jeon, J. Effects of a 4-Week Multimodal Rehabilitation Program on Quality of Life, Cardiopulmonary Function, and Fatigue in Breast Cancer Patients. J Breast Cancer 2015, 18, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, M; Jamnik, R. Physical Activity during Breast Cancer Treatment. The Health & Fitness Journal of Canada 2009, 5–8 Pages. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, HJ; Covington, KR; Pergolotti, M; Sharp, J; Maynard, B; Eagan, J; et al. Translating Research to Practice Using a Team-Based Approach to Cancer Rehabilitation: A Physical Therapy and Exercise-Based Cancer Rehabilitation Program Reduces Fatigue and Improves Aerobic Capacity. Rehabilitation Oncology 2018, 36, 206–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattick, LJ; Lin, P-J; Mustian, KM; Peppone, LJ; Gada, U; Samuel, SR; et al. Walking dose required to achieve a clinically meaningful reduction in cancer-related fatigue among patients with breast cancer receiving chemotherapy: A URCC NCORP nationwide prospective cohort study. JCO 2024, 42, 12008–12008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahçaci, U; Uysal, SA; Namal, E. Relaxation training via tele-rehabilitation program in patients with breast cancer receiving chemotherapy during COVID-19. DIGITAL HEALTH 2024, 10, 20552076241261909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fereidouni, Z; Dehghan Abnavi, S; Ghanbari, Z; Gashmard, R; Zarepour, F; Khalili Samani, N; et al. The Impact of Cancer on Mental Health and the Importance of Supportive Services. Galen Med J 2024, 13, e3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galway, K; Black, A; Cantwell, MM; Cardwell, CR; Mills, M; Donnelly, M. Psychosocial interventions to improve quality of life and emotional wellbeing for recently diagnosed cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012, 2012, CD007064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinapoli, L; Colloca, G; Di Capua, B; Valentini, V. Psychological Aspects to Consider in Breast Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment. Curr Oncol Rep 2021, 23, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Egidio, V; Sestili, C; Mancino, M; Sciarra, I; Cocchiara, R; Backhaus, I; et al. Counseling interventions delivered in women with breast cancer to improve health-related quality of life: a systematic review. Qual Life Res 2017, 26, 2573–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelvehzadeh, F; Dogaheh, ER; Bernstein, C; Shakiba, S; Ranjbar, H. The effect of a group cognitive behavioral therapy on the quality of life and emotional disturbance of women with breast cancer. Support Care Cancer 2022, 30, 305–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M; Huang, L; Feng, Z; Shao, L; Chen, L. Effects of cognitive behavioral therapy on quality of life and stress for breast cancer survivors: a meta-analysis. Minerva Med 2017, 108, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y; Qin, M; Liao, B; Wang, L; Chang, G; Wei, F; et al. Effectiveness of Peer Support on Quality of Life and Anxiety in Breast Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Breast Care (Basel) 2023, 18, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehrani, AM; Farajzadegan, Z; Rajabi, FM; Zamani, AR. Belonging to a peer support group enhance the quality of life and adherence rate in patients affected by breast cancer: A non-randomized controlled clinical trial*. J Res Med Sci 2011, 16, 658–65. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Romeo, M; Ciria-Suarez, L; Medina, JC; Serra-Blasco, M; Souto-Sampera, A; Flix-Valle, A; et al. Empowerment among breast cancer survivors using an online peer support community. Support Care Cancer 2025, 33, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristokleous, I; Karakatsanis, A; Masannat, YA; Kastora, SL. The Role of Social Media in Breast Cancer Care and Survivorship: A Narrative Review. Breast Care (Basel) 2023, 18, 193–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, T; Basal, C; Seluzicki, C; Li, SQ; Seidman, AD; Mao, JJ. Long-term chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy among breast cancer survivors: prevalence, risk factors, and fall risk. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2016, 159, 327–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, R; Novosel, M; So, OW; Bellampalli, S; Xiang, J; Boldt, G; et al. Duloxetine for prevention and treatment of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN): systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2023, 13, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnowska, M; Iżycka, N; Kapoła-Czyż, J; Romała, A; Lorek, J; Spaczyński, M; et al. Effectiveness of gabapentin pharmacotherapy in chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Ginekol Pol 2018, 89, 200–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezzanotte, JN; Grimm, M; Shinde, NV; Nolan, T; Worthen-Chaudhari, L; Williams, NO; et al. Updates in the treatment of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Curr Treat Options Oncol 2022, 23, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binkhorst, L; Mathijssen, RHJ; van Herk-Sukel, MPP; Bannink, M; Jager, A; Wiemer, EAC; et al. Unjustified prescribing of CYP2D6 inhibiting SSRIs in women treated with tamoxifen. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2013, 139, 923–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busby, J; Mills, K; Zhang, S-D; Liberante, FG; Cardwell, CR. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use and breast cancer survival: a population-based cohort study. Breast Cancer Research 2018, 20, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biglia, N; Torta, R; Roagna, R; Maggiorotto, F; Cacciari, F; Ponzone, R; et al. Evaluation of low-dose venlafaxine hydrochloride for the therapy of hot flushes in breast cancer survivors. Maturitas 2005, 52, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santen, RJ; Stuenkel, CA; Davis, SR; Pinkerton, JV; Gompel, A; Lumsden, MA. Managing Menopausal Symptoms and Associated Clinical Issues in Breast Cancer Survivors. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2017, 102, 3647–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey, M; Saunders, C; Partridge, A; Santoro, N; Joffe, H; Stearns, V. Practical clinical guidelines for assessing and managing menopausal symptoms after breast cancer. Annals of Oncology 2008, 19, 1669–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanos-Nanclares, A; Willett, WC; Rosner, BA; Collins, LC; Hu, FB; Toledo, E; et al. Healthful and unhealthful plant-based diets and risk of breast cancer in U.S. women: results from the Nurses’ Health Studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2021, 30, 1921–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farvid, MS; Spence, ND; Rosner, BA; Barnett, JB; Holmes, MD. Associations of low-carbohydrate diets with breast cancer survival. Cancer 2023, 129, 2694–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabel, K; Cares, K; Varady, K; Gadi, V; Tussing-Humphreys, L. Current Evidence and Directions for Intermittent Fasting During Cancer Chemotherapy. Advances in Nutrition 2022, 13, 667–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S; Unger, JM; Crew, KD; Till, C; Greenlee, H; Gralow, J; et al. Omega-3 fatty acid use for obese breast cancer patients with aromatase inhibitor-related arthralgia (SWOG S0927). Breast Cancer Res Treat 2018, 172, 603–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y; Sun, Y; Li, D; Liu, X; Fang, C; Yang, C; et al. Acupuncture for Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Patient-Reported Outcomes. Front Oncol 2021, 11, 646315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, Y; Cheon, C; Motoo, Y; Jang, S; Park, S; Ko, S-G; et al. Complementary and Alternative Medicine for Breast Cancer Patients: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. YAKUGAKU ZASSHI 2019, 139, 1027–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, H; Lauche, R; Klose, P; Lange, S; Langhorst, J; Dobos, GJ. Yoga for improving health-related quality of life, mental health and cancer-related symptoms in women diagnosed with breast cancer. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greaney, SK; Amin, N; Prudner, BC; Compernolle, M; Sandell, LJ; Tebb, SC; et al. Yoga Therapy During Chemotherapy for Early-Stage and Locally Advanced Breast Cancer. Integr Cancer Ther 2022, 21, 15347354221137285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T; Klein, P; Xing, T; Shao, T. Abstract P2-12-03: A yoga program for breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy: Effects on quality of life and chemotherapy-associated symptoms. Cancer Research 2020, 80, P2-12-03-P2-12–03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S, A; K, A; Shetty, A; S Shetty, V. Exploring the Role of Yoga in Alleviating Chemotherapy - Induced Fatigue and Nausea-Vomiting in Women with Breast Cancer - A Narrative Review. J Ayurveda Integr Med Sci 2025, 10, 155–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rofaiel, S; Muo, EN; Mousa, SA. Pharmacogenetics in breast cancer: steps toward personalized medicine in breast cancer management. Pharmgenomics Pers Med 2010, 3, 129–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, GH; SK, D; Pk, K; Arun, V; Yadav, D; Gopi, A; et al. 422P Digital Patient-Reported Outcomes in Cancer Care: Analysis of Quality of Life and Symptom Trajectories Using a Mobile Health Platform. ESMO Open 2025, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aanes, SG; Wiig, S; Nieder, C; Haukland, EC. Implementing digital patient-reported outcomes in routine cancer care: barriers and facilitators. ESMO Real World Data and Digital Oncology 2024, 6, 100088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giesinger, J; Kemmler, G; Meraner, V; Gamper, E-M; Oberguggenberger, A; Sperner-Unterweger, B; et al. Towards the Implementation of Quality of Life Monitoring in Daily Clinical Routine: Methodological Issues and Clinical Implication. Breast Care (Basel) 2009, 4, 148–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Søndergaard, SR; Bechmann, T; Maae, E; Nielsen, AWM; Nielsen, MH; Møller, M; et al. Shared decision making with breast cancer patients - does it work? Results of the cluster-randomized, multicenter DBCG RT SDM trial. Radiother Oncol 2024, 193, 110115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature | EORTC QLQ-C30 + QLQ-BR23 | FACT-B (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Breast) | SF-36 (Short Form-36 Health Survey) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Developer | European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) | FACIT Group (originally by David Cella and colleagues) | RAND Corporation / Boston Health Research Institute |

| Purpose | Cancer-specific QoL assessment with breast cancer module | Breast cancer-specific QoL assessment with general + disease items | Generic health status measure across diseases |

| Target Population | Cancer patients; QLQ-BR23 for breast cancer specifically | Breast cancer patients | General adult population |

| Structure | QLQ-C30: 30 items (global + 5 functional + 3 symptom + 6 single items) QLQ-BR23: 23 items (breast-specific) |

37 items total (FACT-G core + 10 breast-specific items) | 36 items across 8 health domains |

| Domains Measured | - Physical, role, cognitive, emotional, social functioning - Fatigue, nausea, pain, appetite, sleep, financial - BR23: body image, arm symptoms, sexual functioning |

- Physical well-being - Social/family well-being - Emotional well-being - Functional well-being - Breast-specific concerns |

- Physical functioning - Role limitations - Bodily pain - General health - Vitality - Social functioning - Emotional well-being |

| Scoring System | 0–100 linear transformation; higher score = better functioning / worse symptoms | 0–4 Likert scale (total score 0–148); higher = better QoL | 0–100 for each domain; higher = better health |

| Time Frame Referenced | Past week | Past 7 days | Past 4 weeks |

| Psychometric Validity | Widely validated in cancer populations; BR23 specific to breast cancer | Strong reliability and validity in breast cancer populations | Broadly validated across general populations and diseases |

| Sensitivity to Change | High sensitivity to treatment effects (e.g., chemo, surgery, radiation) | High sensitivity in detecting QoL changes due to breast cancer | Less sensitive to cancer-specific QoL changes |

| Strengths | - Disease-specific detail - Modules available for different cancers - Good responsiveness in clinical trials |

- Brief and easy to use - Breast-specific - Suitable for trials and clinics |

- Comprehensive overview of general health - Normative data available |

| Limitations | - Slightly longer to administer (53 items total) - May require license for use |

- Less detailed symptom tracking compared to EORTC - License required |

- Not cancer-specific - Misses disease-relevant issues (e.g., body image) |

| Languages & Global Use | Available in >100 languages; widely used in Europe & trials | Available in >60 languages; used globally | Available in many languages; widespread in public health |

| Best Use Case | Clinical trials and studies requiring detailed breast-specific QoL data | Routine clinical practice and patient monitoring | General population studies or comparison across conditions |

| Dimension | Patient-Reported Outcomes (PROs) | Clinician-Reported Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Direct reports from patients about their health status, symptoms, and functional impact—without interpretation by clinicians. | Observations, diagnoses, or measurements made by clinicians using clinical exams, lab tests, or standard toxicity scales. |

| Common Tools/Instruments | - EORTC QLQ-C30 / QLQ-BR23 - FACT-B - SF-36 - PROMIS - PRO-CTCAE |

- CTCAE (Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events) - ECOG/Karnofsky Performance Status - Lab/imaging results |

| Primary Focus | Subjective experience of symptoms (fatigue, pain, anxiety, daily functioning, body image, etc.) | Objective signs of toxicity, disease progression, or functional decline |

| Sensitivity to Change | High sensitivity to subtle changes in physical, emotional, or cognitive symptoms. | Often insensitive to mild or subjective symptoms; detects only clinically observable or measurable changes. |

| Examples of What Is Measured | - Pain, fatigue, insomnia - Emotional distress - Sexual health - Physical functioning - Cognitive symptoms |

- Neutropenia, anemia - Organ function tests - Tumor size changes - Performance status |

| Strengths | - Captures real patient experience - Enables early detection of QoL decline - Enhances shared decision-making |

- Standardized, objective measurements - Critical for treatment safety, dosing, and trial comparability |

| Limitations | - Subject to reporting bias - Requires patient literacy and engagement - May lack standardization across populations |

- May underestimate symptom burden - Ignores subjective domains (e.g., mood, sexuality) - Less patient-centered |

| Use in Clinical Trials | Increasingly used to assess treatment tolerability and QoL endpoints (e.g., PRO-CTCAE mandated in some trials) | Longstanding use in toxicity grading and clinical safety monitoring |

| Regulatory Relevance | Recognized by FDA/EMA for supporting drug labeling when validated; critical for value-based, patient-centered care | Required for drug approval, trial protocols, and adverse event reporting |

| Intervention Type | Target Symptoms/QoL Domains | Mechanism of Action | Examples / Modalities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Exercise & Rehabilitation | Fatigue, physical function, pain, lymphedema, sleep, mood | Improves mitochondrial function, reduces inflammation, enhances muscle mass and endurance | Aerobic training (e.g., walking), resistance exercise, supervised rehab programs |

| Psychosocial Interventions | Anxiety, depression, emotional distress, body image, coping | Cognitive restructuring, emotional support, behavioral activation | CBT (Cognitive Behavioral Therapy), mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), peer support groups |

| Pharmacologic Management | Neuropathy, depression, menopausal symptoms, nausea, anemia | Neurotransmitter modulation, hormonal replacement, symptom suppression | - Duloxetine for CIPN - SSRIs/SNRIs for depression - Gabapentin for hot flashes - 5-HT3 antagonists for nausea |

| Complementary Therapies | Sleep disturbance, stress, anxiety, fatigue, pain | Modulation of autonomic nervous system, endorphin release, stress hormone reduction | Acupuncture, yoga, massage, aromatherapy, Tai Chi, meditation |

| Nutritional Support | GI distress, fatigue, malnutrition, immune function, weight management | Supports gut microbiota, mitigates mucositis, provides metabolic substrates | Dietitian-led plans, high-protein meals, hydration strategies, enteral support if needed |

| Sexual Health Counseling | Libido loss, vaginal dryness, body image, relationship intimacy | Psychoeducation, behavioral therapy, local hormonal treatment | Vaginal moisturizers/lubricants, pelvic floor therapy, couples therapy |

| Hormone Replacement / Management | Menopausal symptoms (e.g., hot flashes, vaginal atrophy), osteoporosis | Symptom relief via estrogen modulation (non-hormonal preferred in hormone-receptor+ cases) | Gabapentin, clonidine, SSRIs/SNRIs; vaginal estrogens in select cases |

| Financial Counseling | Financial toxicity, employment loss, insurance stress | Resource navigation, cost-sharing strategies, patient advocacy | Oncology social worker support, patient navigation services, financial aid programs |

| Patient Navigation & Education | Empowerment, treatment adherence, communication, decision-making | Enhances health literacy, reduces anxiety, supports shared decision-making | Nurse navigators, survivorship care plans, educational workshops |

| Digital & Remote Monitoring | Symptom tracking, timely intervention, continuity of care | Early detection of worsening symptoms, reduced clinic burden | PRO platforms, telemedicine, mobile health apps (e.g., for fatigue, mood) |

| Spiritual / Existential Support | Meaning-making, emotional resilience, end-of-life planning | Addresses spiritual well-being, helps coping with fear of recurrence or mortality | Chaplaincy, existential therapy, life review interventions |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).