Submitted:

11 December 2025

Posted:

12 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

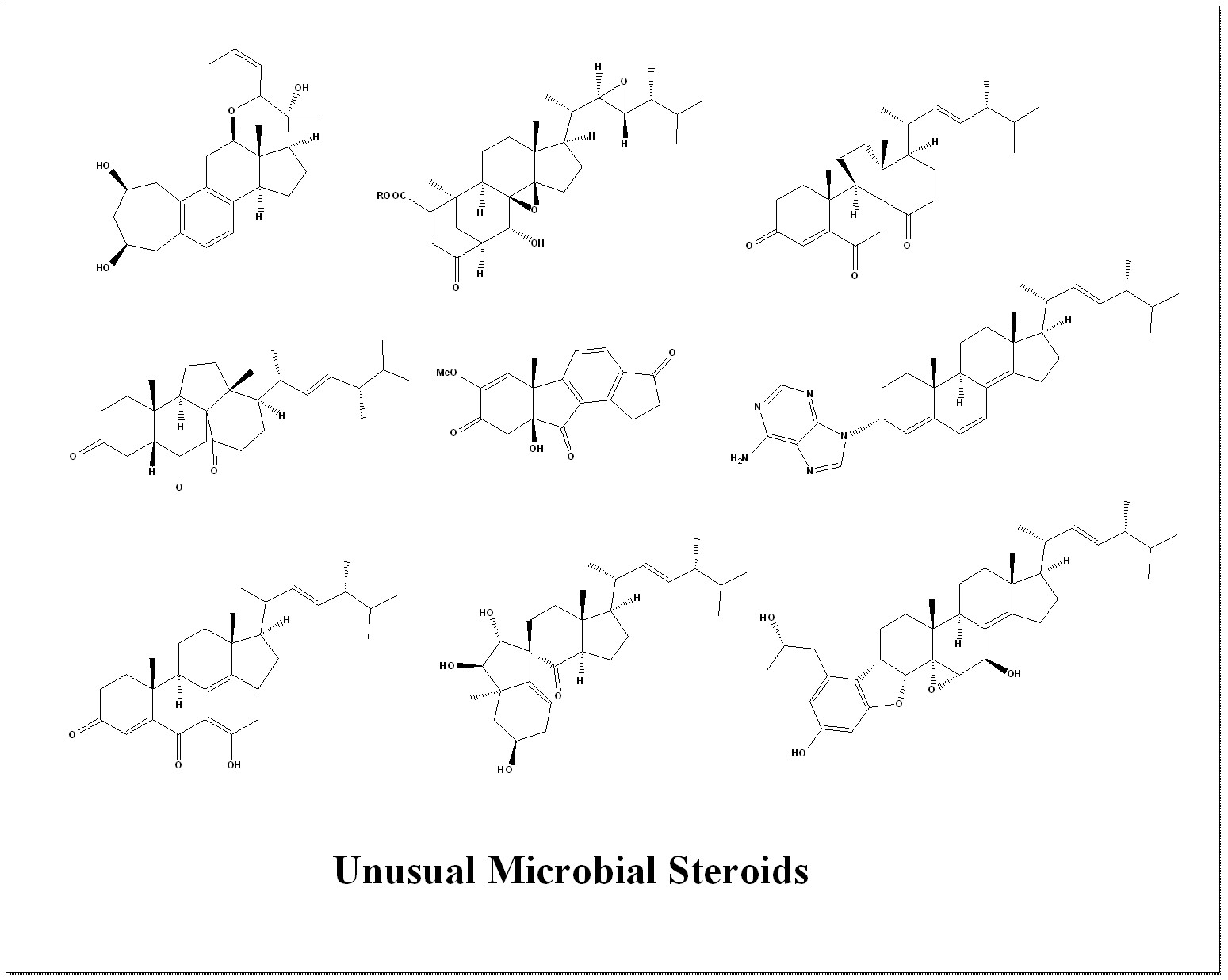

1. Introduction

2. The Genus Aspergillus

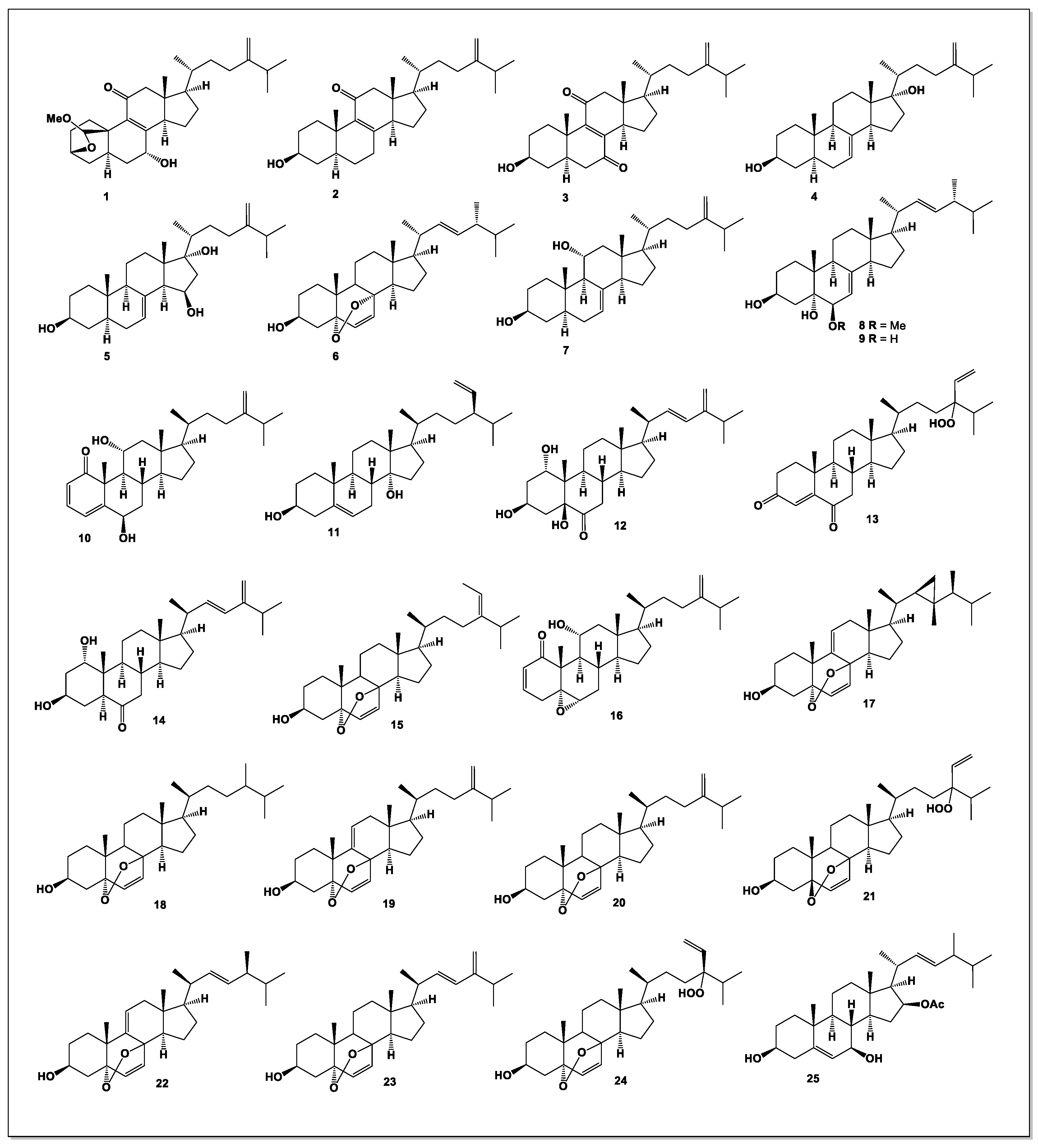

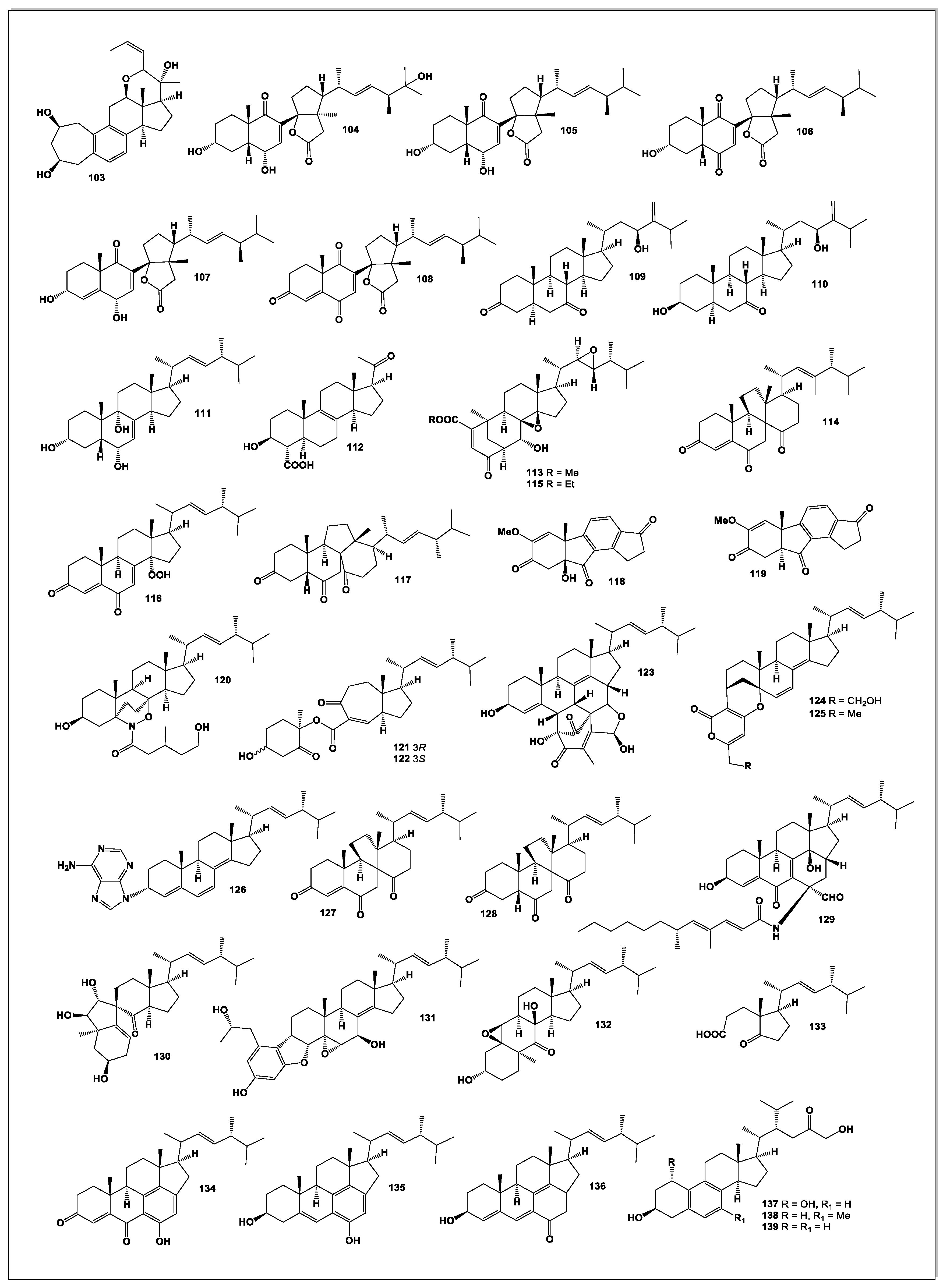

1.1. Steroid Production in Aspergillus aculeatus

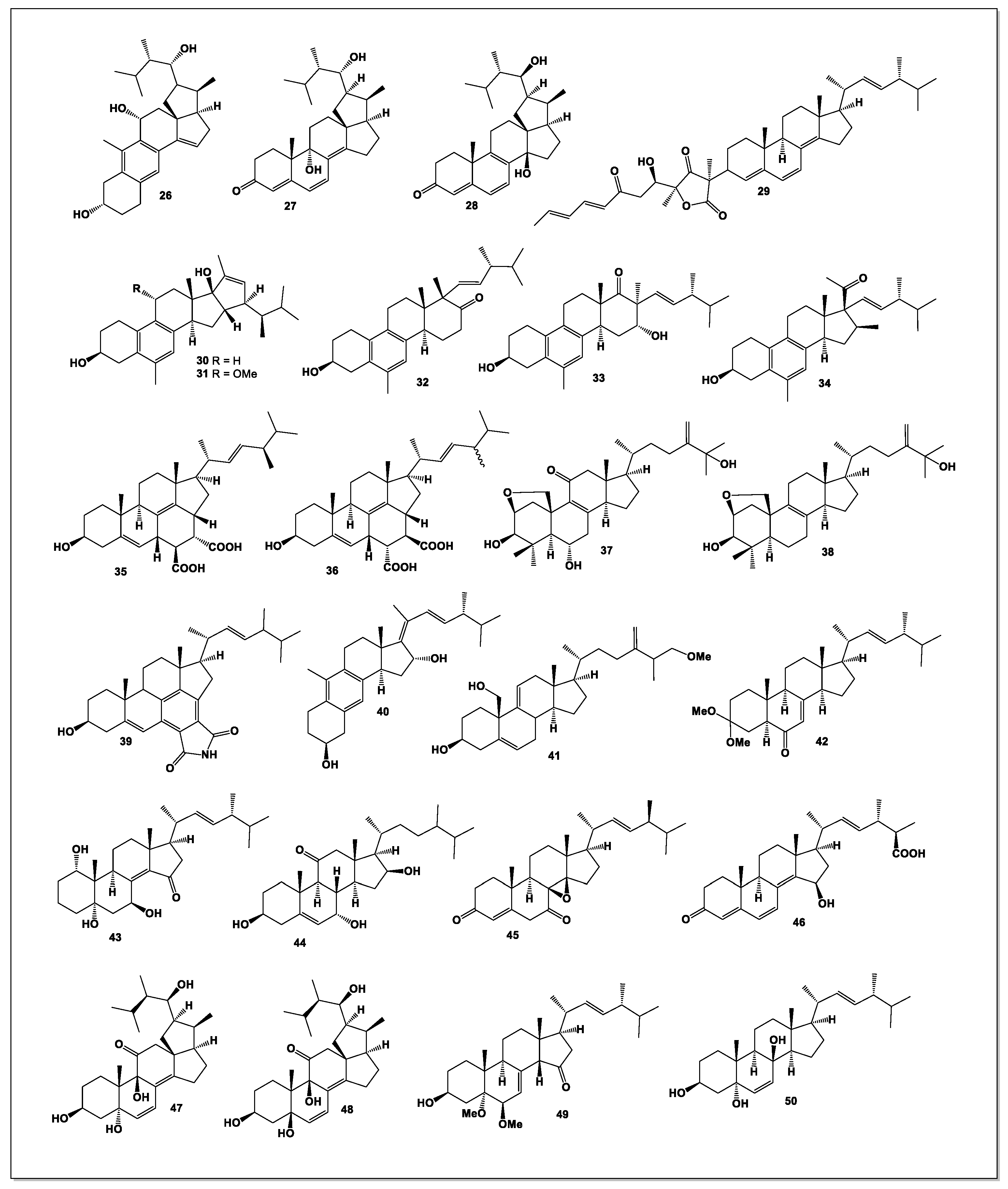

1.2. Steroids from other Aspergillus Species

3. The Genus Penicillium

3.1. Steroidal Metabolites from Penicillium

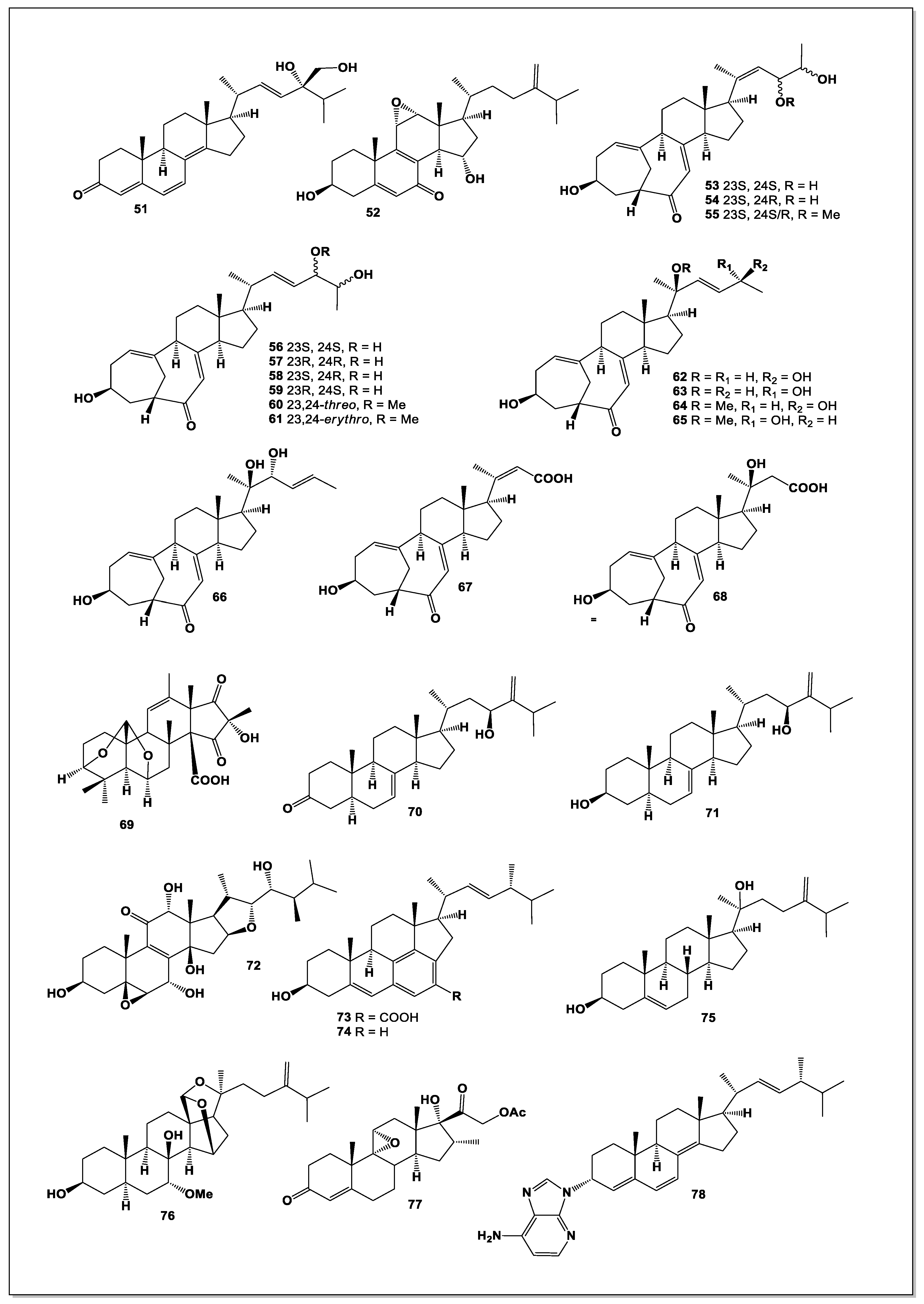

4. Steroids Produced by Miscellaneous Microorganisms

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gao, Y.; Xu, Y.; Dong, Z.; Guo, Y.; Luo, J.; Wang, F.; Zou, X. Endophytic fungal diversity and its interaction mechanism with medicinal plants. Molecules 2025, 30, 1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieber, T.N. Endophytic fungi in forest trees: are they mutualists? Fungal Biology Reviews 2007, 21, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, S.; Dufossé, L.; Deshmukh, S.K.; Chhipa, H.; Gupta, M.K. Endophytic fungi: a treasure trove of antifungal metabolites. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembitsky, V.M.; Terent’ev, A.O. Azo dyes and the microbial world: synthesis, breakdown, and bioactivity. Microbiology Research 2025, 16, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeleke, B.S.; Ayilara, M.S.; Akinola, S.A.; Babalola, O.O. Biocontrol mechanisms of endophytic fungi. Egyptian J. Biological Pest Control 2022, 32, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Reis, J.B.A.; Lorenzi, A.S.; do Vale, H.M.M. Methods Used for the Study of Endophytic Fungi: A Review on Methodologies and Challenges, and Associated Tips. Arch. Microbiol. 2022, 204, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omomowo, I.O.; Amao, J.A.; Abubakar, A.; Ogundola, A.F.; Ezediuno, L.O.; Bamigboye, C.O. A Review on the Trends of Endophytic Fungi Bioactivities. Sci. Afr. 2023, 20, e01594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, N.C.; Rigobelo, E.C. Endophytic Fungi: A Tool for Plant Growth Promotion and Sustainable Agriculture. Mycology 2022, 13, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogas, A.C.; Cruz, F.P.N.; Lacava, P.T.; Sousa, C.P. Endophytic Fungi: An Overview on Biotechnological and Agronomic Potential. Braz. J. Biol. 2024, 84, e258557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Fu, Y.; Song, F. Marine Aspergillus: A Treasure Trove of Antimicrobial Compounds. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, F.; Woo, S.Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Park, S.B.; Zheng, Y.; Chun, H.S. Antifungal Activity of Essential Oils and Plant-Derived Natural Compounds against Aspergillus flavus. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangid, H.; Garg, S.; Kashyap, P.; Karnwal, A.; Shidiki, A.; Kumar, G. Bioprospecting of Aspergillus sp. as a Promising Repository for Anti-Cancer Agents: A Comprehensive Bibliometric Investigation. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1379602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Carvalho, A.C.; Ogawa, C.Y.; Rodrigues, L.C.; de Medeiros, L.S.; Veiga, T.A.M. Penicillium Genus as a Source for Anti-Leukemia Compounds: An Overview from 1984 to 2020. Leuk. Lymphoma 2021, 62, 2079–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Fu, Y.; Song, F.; Xu, X. Recent Updates on the Antimicrobial Compounds from Marine-Derived Penicillium Fungi. Chem. Biodiversity 2023, 20, e202301278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, I.; Wang, Y.; Li, P.; Hussain, S.; Song, J.; Yan, J. Comprehensive Analysis of Penicillium sclerotiorum: Biology, Secondary Metabolites, and Bioactive Compound Potential. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 9555–9566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donova, M.V.; Egorova, O.V. Microbial Steroid Transformations: Current State and Prospects. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 94, 1423–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Averina, O.V.; Zorkina, Y.A.; Yunes, R.A.; Kovtun, A.S.; Ushakova, V.M.; Morozova, A.Y.; et al. Bacterial Metabolites of Human Gut Microbiota Correlating with Depression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, W.R.; Hoyles, L.; Flint, H.J.; Dumas, M.E. Colonic Bacterial Metabolites and Human Health. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2013, 16, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carvalho, C.C.; Fernandes, P. Production of Metabolites as Bacterial Responses to the Marine Environment. Mar. Drugs 2010, 8, 705–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audrain, B.; Farag, M.A.; Ryu, C.M.; Ghigo, J.M. Role of Bacterial Volatile Compounds in Bacterial Biology. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2015, 39, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembitsky, V.M. Hydrobiological Aspects of Fatty Acids: Unique, Rare, and Unusual Fatty Acids Incorporated into Linear and Cyclic Lipopeptides and Their Biological Activity. Hydrobiology 2022, 1, 331–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembitsky, V.M.; Terent’ev, A.O.; Baranin, S.V. Boronosteroids as Potential Antitumor Drugs: A Review. Tumor Discov. 2025, 3, 025290069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, S.E.B.J.W. An Overview of the Genus Aspergillus. In The Aspergilli; 2007; pp. 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Krijgsheld, P.; Bleichrodt, R.V.; Van Veluw, G.J.; Wang, F.; Müller, W.H.; Dijksterhuis, J.; Wösten, H.A.B. Development in Aspergillus. Stud. Mycol. 2013, 74, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, E.; Dunn-Coleman, N.; Frisvad, J.C.; Van Dijck, P.W. On the Safety of Aspergillus niger: A Review. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2002, 59, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, M.; Qu, Z.; Moretti, A.; Logrieco, A.F.; Chu, H.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Aspergillus Mycotoxins: The Major Food Contaminants. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, 2412757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, L. An Overview of Aspergillus Species Associated with Plant Diseases. Pathogens 2024, 13, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Wu, Y.; Long, S.; Feng, S.; Jia, X.; Hu, Y.; Zeng, B. Aspergillus oryzae as a Cell Factory: Research and Applications in Industrial Production. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, F.; Yang, Y.H.; Liu, L.; Shen, Y.; Li, Q.M.; Li, M.; Pei, Y.H. Steroids Isolated from Endophytic Fungus Aspergillus aculeatus. SSRN Preprint 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.J.; Shakerian, F.; Zhao, J.; Li, S.P. Chemistry, pharmacology and analysis of Pseudostellaria heterophylla: a mini-review. Chinese Medicine 2019, 14, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.; Luan, F.; Zou, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhai, B.; Xin, B.; Shi, Y. Traditional uses, phytochemical constituents, pharmacological properties, and quality control of Pseudostellaria heterophylla (Miq.) Pax. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2025, 337, 118871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.F.; Zhang, R.H.; Liu, L.Y.; Yang, Y.H.; Shen, Y.; Li, Q.M.; Pei, Y.H. Steroids, peniciversiols and aspergilosidols from endophytic fungus Aspergillus sp. TZS-Y4. Fitoterapia 2025, 106650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, J.; Chen, S.; Lin, Z.; Sun, H. Sterols from the fungus Lactarium volemus. Phytochemistry 2001, 56, 801–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Hong, K.; Zhang, X.; Liu, H.; Wang, N.; Zhuang, L.; Yao, X. New steryl esters of fatty acids from the mangrove fungus Aspergillus awamori. Helv. Chim. Acta 2007, 90, 1165–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Li, H.; Gao, J. Antimicrobial and allelopathic metabolites produced by Penicillium brasilianum. Nat Prod. Res. 2015, 29, 345–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Razek, A.S.; Hamed, A.; Frese, M.; Sewald, N.; Shaaban, M. Penicisteroid C: New polyoxygenated steroid produced by co-culturing of Streptomyces piomogenus with Aspergillus niger. Steroids 2018, 138, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Duan, F.F.; Gao, Y.; Peng, X.G.; Chang, J.L.; Chen, J.; Ruan, H.L. Aspersteroids A–C, three rearranged ergostane-type steroids from Aspergillus ustus NRRL 275. Organic Letters 2021, 23, 9620–9624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.-L.; Wang, H.-S.; Gao, L.-W.; Zhang, P. Tennessenoid A, an Unprecedented Steroid−Sorbicillinoid Adduct From the Marine-Derived Endophyte of Aspergillus sp. Strain 1022LEF. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 923128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Huang, L.; Li, Q.; Qiao, X.; Zhao, Z.; Yin, J.; Zhang, Y. Spectasterols, Aromatic Ergosterols with 6/6/6/5/5, 6/6/6/6, and 6/6/6/5 Ring Systems from Aspergillus spectabilis. J. Nat. Prod. 2023, 86, 1385–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Dong, Z.; Qiu, P.; Wang, Q.; Yan, J.; Lu, Y.; She, Z. Two new bioactive steroids from a mangrove-derived fungus Aspergillus sp. Steroids 2018, 140, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Fu, A.; Wei, M.; Kang, X.; Chen, C.; Zhang, Y. 30-norlanostane triterpenoids and steroid derivatives from the endophytic fungus Aspergillus nidulans. Phytochemistry 2022, 201, 113257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Zhu, Y.X.; Peng, C.; Li, J. Two new sterol derivatives isolated from the endophytic fungus Aspergillus tubingensis YP-2. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 35, 3277–3284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, V.A.; Kwon, J.H.; Kang, J.S.; Lee, H.S.; Heo, C.S.; Shin, H.J. Aspersterols A–D, ergostane-type sterols with an unusual unsaturated side chain from the deep-sea-derived fungus Aspergillus unguis. J. Nat. Prod. 2022, 85, 2177–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khmel, O.O.; Yurchenko, A.N.; Trinh, P.T.H.; Ngoc, N.T.D.; Trang, V.T.D.; Khanh, H.H.N.; Yurchenko, E.A. Secondary Metabolites of the Marine Sponge-Derived Fungus Aspergillus subramanianii 1901NT-1.40. 2 and Their Antimicrobial and Anticancer Activities. Marine Drugs 2025, 23, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z.; Xiao, X.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, P.; Jiang, W.; Hu, L. New metabolites from Aspergillus ochraceus with antioxidative activity and neuroprotective potential on H2O2 insult SH-SY5Y cells. Molecules 2021, 27, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.F.; Wang, M.M.; Tian, J.; Hu, B.H.; Lu, Y.N.; Yang, C.M.; Feng, R.Z. Chemical constituents from the endophytic fungus Aspergillus sp. S3 of Hibiscus tiliaceus. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2025, 27, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Razek, A.S.; El-Ghonemy, D.H.; Shaaban, M. Production and purification of bioactive compounds with potent antimicrobial activity from a novel terrestrial fungus Aspergillus sp. DHE 4. Biocatal. Agricul. Biotechnol. 2020, 28, 101726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsbaey, M.; Ibrahim, M.A.; Hegazy, M.E.F. Versisterol, a new endophytic steroid with 3CL protease inhibitory activity from Avicennia marina (Forssk.) Vierh. RSC advances 2022, 12, 12583–12589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhan, S.; Yang, S.; Liu, J.; Shan, W.; Wang, R. Ganodermanic acid, a new steroidal compound derived from the marine fungus Aspergillus sp. ZJUT223. Nat. Prod. Res. 2025, 21, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, J.; Li, S.; Ma, R.; Shi, Q.; Meng, X.; Zhou, G.; Li, H. New secondary metabolites from the soil-derived Aspergillus versicolor QC812. Steroids 2025, 109629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, H.M.; Zhang, Y.W.; Feng, F.J.; Huang, G.B.; Lv, Y.H.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Ding, L.J. Antibacterial oxygenated ergostane-type steroids produced by the marine sponge-derived fungus Aspergillus sp. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2024, 26, 548–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, S.W. Aspergillus and Penicillium identification using DNA sequences: barcode or MLST? Applied Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 95, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrone, G.; Susca, A. Penicillium species and their associated mycotoxins. Mycotoxigenic Fungi: Methods and Protocols 2016, 11, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visagie, C.M.; Yilmaz, N.; Kocsubé, S.; Frisvad, J.C.; Hubka, V.; Samson, R.A.; Houbraken, J. A review of recently introduced Aspergillus, Penicillium, Talaromyces and other Eurotiales species. Studies in Mycology 2024, 107, 1–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visagie, C.M.; Houbraken, J.; Frisvad, J.C.; Hong, S.B.; Klaassen, C.H.W.; Perrone, G.; Samson, R.A. Identification and nomenclature of the genus Penicillium. Studies in Mycology 2014, 78, 343–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashtekar, N.; Anand, G.; Thulasiram, H.V.; Rajeshkumar, K.C. Genus Penicillium: advances and application in the modern era. New and Future Developments in Microbial Biotechnology and Bioengineering 2021, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlovskii, A.G.; Zhelifonova, V.P.; Antipova, T.V. Fungi of the genus Penicillium as producers of physiologically active compounds. Applied Biochem. Microbiol. 2013, 49, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez, R.; Bull, P.; Eyzaguirre, J. The xylanolytic enzyme system from the genus Penicillium. J. Biotechnol. 2006, 123, 413–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meskini, M.; Rami, M.R.; Tavakoli, R.; Salami, M. Molecular Markers in Diagnostics of Fungi and Fungal Mycotoxins: A Narrative Review. J. Infection Public Health 2025, 103073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mady, M.; Haggag, E. Review on fungi of genus Penicillium as a producers of biologically active polyketides. J. Advanced Pharmacy Res. 2020, 4, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemmam, D.A.; Bourzama, G.; Chemmam, M. The genus Penicillium: Ecology, secondary metabolites and biotechnological applications. Biol. Aujourd’hui 2025, 219, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, F.Z.; Marcelão, C.V.P.; Silva, J.J.D.; Taniwaki, M.H. Fungi and mycotoxins in Brazilian artisanal cheese. Brazilian J. Food Technol. 2025, 28, e2024131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, S.S.; Alamre, J.H.; Alsubait, A.; Alanzi, A.R.; Aldawish, B.S.; Althobiti, F.; Mohammed, A.E. Bioactive Compounds From Saudi Arabian Fungi: A Systematic Review of Anticancer Potential. Clinical Pharmacology: Advances and Applications 2025, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.T.; Yang, L.; Wang, Z.P.; Guo, J.C.; Ma, Q.Y.; Xie, Q.Y.; Zhao, Y.X. Persteroid, a new steroid from the marine-derived fungus Penicillium sp. ZYX-Z-143. Nat. Prod. Res. 2024, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.Z.; Li, X.M.; Meng, L.H.; Wang, B.G. A new steroid with potent antimicrobial activities and two new polyketides from Penicillium variabile EN-394, a fungus obtained from the marine red alga Rhodomela confervoides. J. Antibiot. 2024, 77, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, M.W.; Cui, C.B.; Li, C.W.; Wu, C.J. Three new and eleven known unusual C25 steroids: Activated production of silent metabolites in a marine-derived fungus by chemical mutagenesis strategy using diethyl sulphate. Marine Drugs 2014, 12, 1545–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Chen, C.; Cai, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, B.; Tao, H. Two C23-Steroids and a New Isocoumarin Metabolite from Mangrove Sediment-Derived Fungus Penicillium sp. SCSIO 41429. Marine Drugs 2024, 22, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.B.; Wang, M.N.; Hu, J.Y.; Han, R.; Yang, X.; Shi, W.; Xiao, J. An Unusual Meroterpenoid and Two New Steroids From Fungus Penicillium fellutanum and Their Bioactivities. Chem. Biodiver 2025, 22, e202403443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, F.; Song, W.; Li, H.; Cao, L. Peniciloxatone A, a New Polyoxygenated Ergostane Steroid Isolated from the Marine Alga-Sourced Fungus Penicillium oxalicum 2021CDF-3. Rec. Nat. Prod. 2024, 18, 699–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, Z.; Li, X.M.; Wang, B.G.; Li, H.L.; Meng, L.H. Rubensteroid A, a new steroid with antibacterial activity from Penicillium rubens AS-130. J. Antibiot. 2023, 76, 563–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, C.A.; Tan, C.Y.; Krishnan, D.; Uchenik, D.; Eugenio, G.D.A.; Salinas, E.D.; Rakotondraibe, H.L. Steroids and Epicoccarines from Penicillium aurantiancobrunneum. Phytochemistry Letters 2024, 63, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salendra, L.; Lin, X.; Chen, W.; Pang, X.; Luo, X.; Long, J.; Yang, B. Cytotoxicity of polyketides and steroids isolated from the sponge-associated fungus Penicillium citrinum SCSIO 41017. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 35, 900–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.M.; Yu, S.Q.; Tao, M.; Xia, C.B.; Xia, Y.L.; Wu, X.F.; Dong, C.Z. New Purinyl-Steroid and Other Constituents from the Marine Fungus Penicillium brefeldianum ABC190807: Larvicidal Activities against Aedes aegypti. J. Chem. 2021, 2021, 6640552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, C.A.; Kinghorn, A.D.; Rakotondraibe, H.L. Bioactive and unusual steroids from Penicillium fungi. Phytochemistry 2023, 209, 113638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Wu, P.; Xu, L.; Wei, X. Penicillitone, a potent in vitro anti-inflammatory and cytotoxic rearranged sterol with an unusual tetracycle core produced by Penicillium purpurogenum. Organic Letters 2014, 16, 1518–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igarashi, Y.; Sekine, A.; Fukazawa, H.; Uehara, Y.; Yamaguchi, K.; Endo, Y.; Oki, T. Anicequol, a novel inhibitor for anchorage-independent growth of tumor cells from Penicillium aurantiogriseum Dierckx TP-F0213. J. Antibiot. 2002, 55, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, S.S.; Li, X.M.; Li, C.S.; Proksch, P.; Wang, B.G. Penicisteroids A and B, antifungal and cytotoxic polyoxygenated steroids from the marine alga-derived endophytic fungus Penicillium chrysogenum QEN-24S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Letters 2011, 21, 2894–2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Tian, L.; Huang, J.; Li, W.; Pei, Y.H. Cytotoxic sterols from marine-derived fungus Pennicillium sp. Nat. Prod. Res. 2006, 20, 381–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhang, M.; Qiao, Y.; Huang, S.; Zhou, X. Penicimides A and B, two novel diels–alder [4+2] cycloaddition ergosteroids from Penicillium herquei. Bioorg. Chem. 2024, 143, 107025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Kang, J.; Zhou, Q.; Chen, M.; Zhang, J.; Shi, Z.; Zhang, Y. Discovery of 23, 24-diols containing ergosterols with anti-neuroinflammatory activity from Penicillium citrinum TJ507. Bioorg. Chem. 2024, 150, 107575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Yang, W.C.; Li, T.B.; Yin, Y.H.; Liu, Y.F.; Wang, B.; She, Z.G. Hemiacetalmeroterpenoids A–C and astellolide Q with antimicrobial activity from the marine-derived fungus Penicillium sp. N-5. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Qin, D. Diversity and Biological Activity of Secondary Metabolites Produced by the Endophytic Fungus Penicillium ochrochlorae. Fermentation 2025, 11, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; He, Z.; Wen, Z.; Sun, G.; Tang, X.; Yin, T.; Cai, L. Expansinine, a novel indole alkaloid–ergosteroid conjugate from the endophytic fungus Penicillium expansum of Aconitum carmichaelii. RSC Advances 2025, 15, 14283–14288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Qin, C.L.; Zhou, T.; Li, W.P.; Hu, J.Y.; Zhou, Y.H.; Ruan, H.L. Scabrosteroids A–D, Four Pyrrolidinone–Ergosterol Heterodimers from Penicillium scabrosum FXI744. Org. Lett. 2025, 27(24), 6434–6438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jie-Yi, L.O.N.G.; Jun-Feng, W.A.N.G.; Sheng-Rong, L.I.A.O.; Xiu-Ping, L.I.N. Four new steroids from the marine soft coral-derived fungus Penicillium sp. SCSIO41201. Chinese J. Nat. Med. 2020, 18, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.W.; Kong, L.M.; Zu, W.Y.; Hu, K.; Li, X.N.; Yan, B.C.; Puno, P.T. Isopenicins A–C: two types of antitumor meroterpenoids from the plant endophytic fungus Penicillium sp. sh18. Organic Letters 2019, 21, 771–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Kim, E.; Li, J.L.; Hong, J.; Yoon, W.D.; Kim, H.S.; Liu, Y.; Jung, J.H. An unusual 1 (10→ 19) abeo steroid from a jellyfish-derived fungus. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 2803–2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, C.; Fang, T.; Wu, L.; Liu, W.; Tang, J.; Long, Y. New steroid and isocoumarin from the mangrove endophytic fungus Talaromyces sp. SCNU-F0041. Molecules 2022, 27, 5766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, P.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Si, S.; Liu, X.; Che, Y. Altersteroids A–D, 9, 11-Secosteroid-Derived γ-Lactones from an Alternaria sp. J. Nat. Prod. 2023, 86, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, T.; Liu, J.; Lin, L.B.; Hu, J.Y.; Wu, G.W.; Fan, P.H.; Wang, X.L. Acrocalysterols A and B, two new steroids from endophytic fungus Acrocalymma sp. Phytochemistry Letters 2022, 48, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhari, A.; Naini, A.A.; Harneti, D.; Wulandari, A.P.; Mulyani, Y.; Purbaya, S.; Supratman, U. New steroid produced by Periconia pseudobyssoides K5 isolated from Toona sureni (Meliaceae) and its heme polymerization inhibition activity. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2023, 25, 1117–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsebai, M.F.; Kehraus, S.; König, G.M. Caught between triterpene-and steroid-metabolism: 4α-Carboxylic pregnane-derivative from the marine alga-derived fungus Phaeosphaeria spartinae. Steroids 2013, 78, 880–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Xie, S.; Sun, W.; Guo, Y.; Li, X.N.; Zhang, Y. Phomopsterones A and B, two functionalized ergostane-type steroids from the endophytic fungus Phomopsis sp. TJ507A. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 258–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.Z.; Han, K.Y.; Li, Z.H.; Feng, T.; Chen, H.P.; Liu, J.K. Cytotoxic ergosteroids from the fungus Stereum hirsutum. Phytochemistry Lett. 2019, 30, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Ross, L.; Tamayo, G.; Clardy, J. Asterogynins: secondary metabolites from a Costa Rican endophytic fungus. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 4661–4663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, S.; Yang, J.; Zhao, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, Z. Trichosterol A, a unique 6/6/6/5/6-fused steroid-alkaloid hybrid with bioherbicidal activity from Trichoderma koningiopsis. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2025, 23, 10280–10284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.Q.; Yao, F.H.; Luo, L.X.; Wu, Y.H.; Qi, S.H. Microascusteroids A and B, two 5, 6-seco-9, 10-seco steroids with a C-ring rearranged ergostane skeleton from the marine-derived fungus Microascus sp. SCSIO 41821. Fitoterapia 2025, 183, 106537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.F.; Du, H.F.; Zhang, Y.H.; Liu, Z.Q.; Qi, X.Q.; Luo, D.Q.; Cao, F. Chaeglobol A, an unusual octocyclic sterol with antifungal activity from the marine-derived fungus Chaetomium globosum HBU-45. Chinese Chem. Lett. 2025, 36, 109858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Cai, J.; Yang, C.; Tao, H.; Tang, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, X. Striasteroids A–C, Three Hybrid Steroids with Neuraminidase Inhibitory Activities from a Marine-Derived Striaticonidium cinctum. Org. Lett. 2025, 27, 3737–3741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amagata, T.; Tanaka, M.; Yamada, T.; Doi, M.; Minoura, K.; Ohishi, H.; Numata, A. Variation in cytostatic constituents of a sponge-derived Gymnascella dankaliensis by manipulating the carbon source. J. Nat. Prod. 2007, 70, 1731–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, Q.; Mao, L.; Zhu, H. Bipolarsterol A, a steroid with an unprecedented 6/5/6/5 carbon skeleton from the phytopathogenic fungus Bipolaris oryzae. Org. Chem. Frontiers 2025, 12, 1474–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.Z.; Chen, H.P.; Wu, B.; Zhang, L.; Li, Z.H.; Feng, T.; Liu, J.K. Matsutakone and matsutoic acid, two (nor) steroids with unusual skeletons from the edible mushroom Tricholoma matsutake. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 7974–7979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.A.; Li, H.F.; Huang, S.S.; Jin, T.; Xie, W.Z.; He, J.; Feng, T. Cordycepsterols A–C, Anti-Inflammatory C30 Ergosterols with a 6/6/6/5/6-Fused Ring System from Cordyceps militaris. J. Nat. Prod. 2025, 88, 1499–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Zhu, J.; Mu, R.; Wang, C.; Sun, Y.; Qian, B.; Chen, Y. Metabolites with Anti-Inflammatory Activities Isolated from the Mangrove Endophytic Fungus Dothiorella sp. ZJQQYZ-1. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).